Evaluation of the Multiculturalism Program 2011-12 to 2016-17

Period from April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2017

Evaluation Services Directorate

March 29, 2018

Cette publication est aussi disponible en français.

©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2018

Catalogue No. CH7-59/2018E-PDF

ISBN 978-0-660-26668-8

Table of contents

- List of tables

- List of figures

- List of acronyms

- Executive summary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Program profile

- 3. Approach and methodology

- 4. Findings

- 5. Conclusions

- 6. Recommendations, management response and action plan

- Annex A: evaluation framework

- Annex B: bibliography

List of tables

- Table 1: program objectives and expected outcomes

- Table 2: multiculturalism Program budgeted and actual expenditures (2011-12 to 2016-17)

- Table 3: evaluation questions by core issue

- Table 4: scale for the presentation of results

- Table 5: approved events by CIC/IRCC Region 2011-12 to 2014-15

- Table 6: approved events by PCH Region 2015-16 -2016-17

List of figures

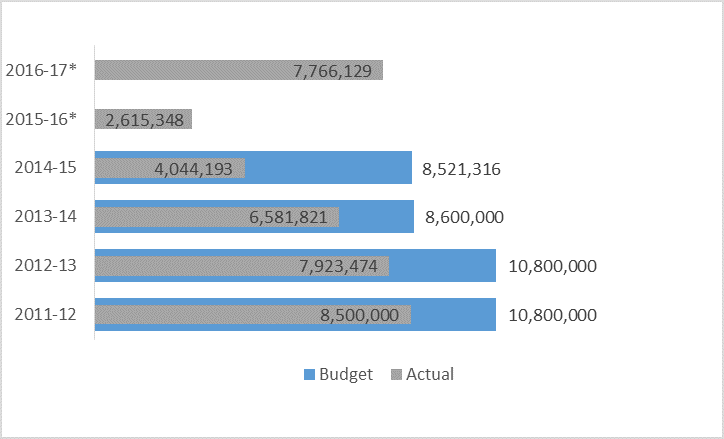

- Figure 1: Inter-Action: lapsed vote 5 (total $)

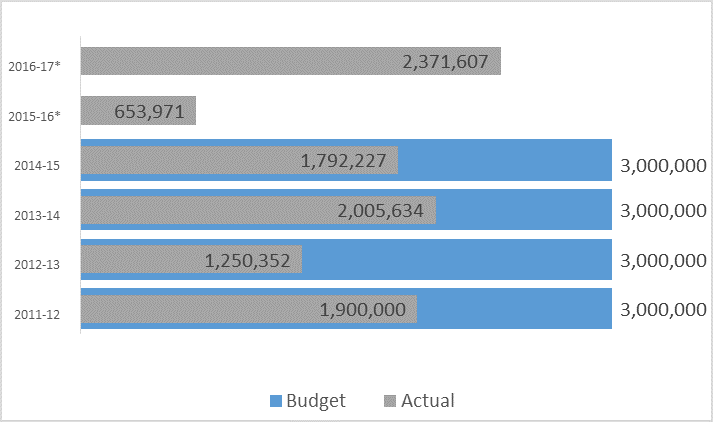

- Figure 2: Inter-Action: lapsed grants ($)

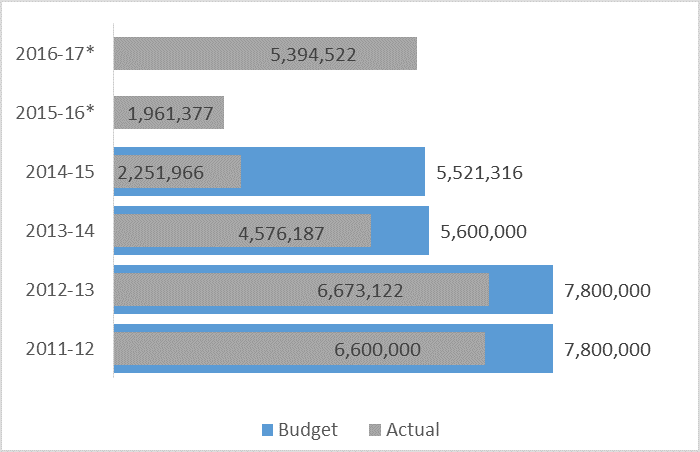

- Figure 3: Inter-Action: lapsed contributions ($)

List of acronyms

- CAPAR

- Canada's Action Plan Against Racism

- CERD

- Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

- CIC

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada

- DPR

- Departmental Performance Report

- ESD

- Evaluation Services Directorate

- FAA

- Financial Administration Act

- FTE

- Full-Time Equivalent

- FPTORMI

- Federal-Provincial-Territorial Officials Responsible for Multiculturalism Issues

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GCIMS

- Grants and Contributions Information Management System

- GCP

- Global Centre for Pluralism

- GDPR

- General Data Protection Regulation

- GC

- Government of Canada

- Gs&Cs

- Grants and Contributions

- GSS

- General Social Survey

- ICERD

- International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination

- IHRA

- International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- LGBTQ+

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans Queer/Questioning, and others

- MCN

- Multiculturalism Champions Network

- NHS

- National Household Survey

- OARH

- Organizing Against Racism and Hate

- OECD

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

- O&M

- Operations and Maintenance

- PAA

- Program Alignment Architecture

- PCH

- Department of Canadian Heritage

- Portable Document Format

- PRG

- Policy Research Group

- P/T

- Provincial/Territorial

- RIPEC

- Results, Integrated Planning and Evaluation Committee

- RPP

- Report on Plans and Priorities

- SPPR

- Strategic Policy Planning and Research

- Ts&Cs

- Terms and Conditions

- UN

- United Nations

- UNCERD

- United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

Executive summary

Overview of the Multiculturalism Program

The Multiculturalism Program is one means by which the Government of Canada implements the Canadian Multiculturalism Act and advances the Government of Canada's priorities in the area of multiculturalism. Between 2008 and November 2015, the Program was delivered by Citizenship and Immigration Canada (CIC)/Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC). In November 2015, the Program was transferred to the Department of Canadian Heritage (PCH).

At PCH, the Program delivery is shared by three Branches – Strategic Policy, Planning and Research, Citizen Participation and Communications – and the five Regions. In 2016-17, the Program's expenditures were $10.1 million.

The Multiculturalism Program delivers its mandate through 4 key areas of activity:

- Grants and Contributions (Gs&Cs) (Inter-Action). The Multiculturalism Program has an annual budget of $8.5 million in Gs&Cs for projects and events that foster an integrated, socially cohesive society. Inter-Action is administered by both National Headquarters (projects) and the five PCH Regions (events).

- Public outreach and promotion. The Multiculturalism Program undertakes public outreach and promotional activities, including: Asian Heritage Month, Black History Month and the Paul Yuzyk Award for Multiculturalism.

- Support to federal and public institutions. The Program supports federal institutions to implement their responsibilities under the Canadian Multiculturalism Act and to develop their submissions to the Annual Report on the Operation of the Multiculturalism Act. The Program coordinates the submissions and prepares the Annual Report. It also coordinates the Multiculturalism Champions Network (MCN), a Government of Canada community of practice of multiculturalism champions. The Program collaborates with provinces and territories on mutual priorities through the Federal-Provincial-Territorial Officials Responsible for Multiculturalism (FPTORMI) network.

- International engagement. The Program participates in international agreements and institutions to advance multiculturalism, diversity and anti-racism in Canada and internationally.

The Multiculturalism Program's three objectives came into effect in April 2010:

- build an integrated, socially cohesive society;

- improve the responsiveness of institutions to the needs of a diverse population; and

- actively engage in discussions on multiculturalism and diversity at the international level.

Evaluation approach and methodology

The evaluation covered the period 2011-12 to 2016-17 and was conducted in accordance with the requirements of the Treasury Board Policy on Results (2016) and the Financial Administration Act (FAA). The evaluation assessed the Program's relevance, effectiveness and efficiency, including design and delivery.

The evaluation approach involved a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection methods and primary and secondary data sources to address the evaluation issues and questions.

Findings

Relevance

The Multiculturalism Program remains relevant. While Canadians are generally positive toward immigration, visible minorities and multiculturalism, there continues to be a need to address the challenges associated with an increasingly diverse Canada, including the rise of populism; controversies associated with increased levels of immigration; intolerance toward religious and ethnocultural groups; the persistence of hate crimes; and the underlying factors that contribute to the socio-economic disadvantages experienced by certain groups.

Although Program activities address some of these issues, there were gaps identified by key informants, including a national strategy for racism and discrimination; supporting institutional change to address systemic issues and the availability of project funding to address unique local or regional needs. The Program's ability to address these gaps is constrained by a lack of capacity to achieve the broad policy objectives of the Act; the lack of evidence, including performance data, to inform policy and program development; and the Program's funding and delivery model.

The Program is aligned with the Government's diversity and inclusion priority which has been emphasized in the 2015 Speech from the Throne, in successive Budgets and in the Ministers' mandate letters. However, there is a perception that multiculturalism has been less visible as a result of the emphasis on diversity and inclusion. Multiculturalism is one facet of diversity, and there is a need to clarify the Program's role in advancing the broader scope of the Government's diversity and inclusion priority.

There is a role for the federal government in advancing multiculturalism. Key informants expressed the view that the federal government should take a leadership role, particularly in championing multiculturalism; conveying strong messages against racism and discrimination; and by conducting research, providing data and sharing information.

According to key informants, the Program's objectives are too broad and while this allows for flexibility, they do not align closely to Program activities or priorities, nor do they articulate the intended impact in a changing context or respond directly to key challenges.

Effectiveness

There is limited performance data to conclude that the Program's activities contributed to the achievement of its expected outcomes or that they are the most effective levers to achieve the outcomes.

- Public outreach and promotion activities such as Black History Month and Asian Heritage Month were widely promoted and engaged Canadians. The Paul Yuzyk Award was on hold during the last two years covered by the evaluation. Internal key informants raised issues about the Multiculturalism Policy Unit's capacity and role in delivering public outreach and promotion.

- After the Program's transfer to PCH, activities related to coordination and support to federal and other public institutions were limited in scope due, in part, to a period of inactivity of the MCN and the FPTORMI network following the transfer and the limited capacity of the Multiculturalism Policy Unit . Responses to the MCN members' survey indicated that the network was only moderately effective in contributing to expected outcomes. However, members of both networks consider their network to be relevant but would like to see an expanded mandate that moves beyond information-sharing.

- The Program effectively coordinated input to the Annual Report on the Operation of the Multiculturalism Act. The majority of institutions provided input annually. The number dropped in 2016-17. The Program revised its template to strengthen reporting to be more outcomes focused, which may have contributed to a lower response rate.

- Inter-Action projects did not report against specific outcome indicators in their final project activity reports but provided narrative descriptions of their results. The file review and case studies found that these narratives demonstrated that projects' activities aligned with the objectives and expected outcomes of the Program. The strategic initiatives projects were able to demonstrate that their activities aligned with Government priorities.

- The Program's international engagement activities contributed to the immediate outcome of increasing policy awareness about international approaches to diversity. However, it is not evident that this translated into the implementation of international best practices in the Canadian context and to the achievement of the intermediate outcomes of the Program.

Key informants identified several gaps in terms of the current program activities, among them addressing racism; engaging with communities and the privates sector; forging strategic partnerships to address issues; and conducting or funding research. Some of these gaps align with the policy levers suggested by the Canadian Multiculturalism Act as potential measures to implement the multiculturalism policy.

Efficiency

Between 2011-12 and 2016-17, there were two calls for applications. The 2015 intake received 52 applications of which 13 received funding. The number of applications for the 2017 intake increased five-fold to 256, of which 55 received funding.

The efficiency of the Multiculturalism Program has been affected by the lengthy time frames for the approval process for the Gs&Cs for the 2015 and 2017 calls for applications. As a result, the service standard for the notification of funding decisions for projects was not met for the 2015 and 2017 calls, which led to delays in notifying recipients of funding decisions and late start dates for projects.

While at CIC/IRCC, the Program lapsed Gs&Cs funding which affected the efficiency of the Program and the achievement of its outcomes as Gs&Cs were not being used to fund projects and events. Between 2011-12 and 2013-14, the Program lapsed between 21 and 26 per cent of its Gs&Cs budget. This increased to 52.5 per cent in 2014-15. This lapse was attributed to demand being lower than expected. Further analysis showed that the lapse was more pronounced for grants than for contributions.

Design and delivery

The majority of internal key informants identified challenges with communications, coordination and decision-making as a result of the Program's current structure and design and delivery model. The split between policy, operations and communications was created at CIC/IRCC, to align with CIC/IRCC's functional model, and was maintained at PCH. At PCH, this model is unique to the Multiculturalism Program. As a result, several issues have emerged. This includes a lack of clear roles and responsibilities, especially with respect to responsibility for program policy development.

Issues also emerged with respect to the Multiculturalism Policy Unit's capacity to undertake public outreach and promotion. At CIC/IRCC, this activity was the responsibility of the Communications Branch while at PCH, Communications provides advice and the Program is responsible for the activities.

The majority of key informants identified the current funding model and eligibility criteria as having created a gap in terms of project funding to address unique regional and local needs.

Performance measurement

Limited performance information is captured by the Multiculturalism Program, particularly to measure the achievement of outcomes. As a result there is limited evidence to demonstrate if, and to what extent, the Multiculturalism Program is achieving its objectives and expected outcomes, or to identify what works, to support future funding decisions.

Recommendations

Based on the findings of this evaluation, the following six recommendations are being made:

Recommendation 1

The Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic Policy, Planning and Corporate Affairs, in collaboration with the Assistant Deputy Minister, Citizenship, Heritage and Regions, should lead a policy development exercise which, within the context of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act, will articulate the Multiculturalism Program's vision, goals/objectives, priority actions, roles and responsibilities and the expected results for the Program going forward. This policy visioning exercise should be inclusive of consultations with internal and external stakeholders, national and local community organizations, its existing networks (MCN and FPTORMI) and others, as appropriate.

Recommendation 2

To address the lack of evidence on the effectiveness of interventions (what works) in support of policy development and program decision-making, the Assistant Deputy Minister Strategic Policy, Planning and Corporate Affairs, in collaboration with the Assistant Deputy Minister Citizenship, Heritage and Regions, should examine and implement (for example, through research and experimentation) ways to measure the impact of program interventions, projects and activities.

Recommendation 3

The Assistant Deputy Minister Strategic Policy, Planning and Corporate Affairs, in collaboration with the Assistant Deputy Minister Citizenship, Heritage and Regions, should:

- update the Program Information Profile to include indicators measuring immediate, intermediate and long-term program outcomes; and

- review and revise the data collection instruments and existing mechanisms to ensure outcome data is collected and analyzed for all elements of the program.

Recommendation 4

To address the identified governance challenges, improve communication, collaboration and decision-making the Assistant Deputy Minister, Strategic Policy, Planning and Corporate Affairs, the Assistant Deputy Minister, Citizenship, Heritage and Regions, and the Director General, Communications should review the Program's structure (which has a wide scope of policy, outreach and operational activities delivered through two sectors, all regions, and one direct report) as well as the roles and responsibilities.

Recommendation 5

The Assistant Deputy Minister, Citizenship, Heritage and Regions, should revisit the eligibility criteria for projects to allow for support to address systemic regional and local issues.

Recommendation 6

In order to provide recipients with timely funding decisions the Assistant Deputy Minister, Citizenship, Heritage and Regions, should implement measures to ensure the Program service standards are met.

1. Introduction

This report presents the findings, conclusions and recommendations of the evaluation of the Multiculturalism Program. The evaluation covers the period from April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2017. The evaluation was conducted in accordance with the 2016 Treasury Board Policy on Results.Footnote 1 The evaluation provides comprehensive and reliable evidence regarding the relevance and performance of the Multiculturalism Program. The evaluation also examines issues of design and delivery and performance measurement. The results of the evaluation will support accountability and inform decision-making.

The Program was last evaluated in 2012. The Treasury Board Secretariat granted a one-year extension to March 31, 2018 to complete this evaluation in consideration of the transfer of the Program to PCH from CIC/IRCC in November 2015.

In addition to this introduction, the evaluation report has the following main sections:

- Section 2 presents the program profile.

- Section 3 presents the evaluation methodology and methodological limitations.

- Section 4 presents the findings relating to relevance, performance, design and delivery and performance measurement.

- Section 5 presents the conclusions.

- Section 6 presents the recommendations and the management response and action plan.

2. Program profile

The federal government first recognized multiculturalism as a fundamental characteristic of Canadian society through the formal adoption of the multiculturalism policy in 1971, by recognizing the contributions made by many ethnocultural groups, beside French and British. The policy encouraged a vision of Canada based on the values of equality, and mutual respect with regards to race, national or ethnic origin, color and religion.Footnote 2 The 1971 multiculturalism policy also confirmed the rights of Indigenous Peoples and the status of Canada's two official languages.

The 1980's saw a growing institutionalization of the multiculturalism policy which coincided with a period of difficulty for race relations in Canada. The government first concentrated on promoting institutional change to help Canadian institutions adapt to an increasingly diverse population. During this time, the focus was on the introduction of anti-discrimination programs aimed at removing social and cultural barriers.Footnote 3 In 1982, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms recognized the multicultural heritage of Canada. Section 27 states "This Charter shall be interpreted in a manner consistent with the preservation and enhancement of the multicultural heritage of Canadians."Footnote 4 The Charter effectively placed multiculturalism within the wider framework of Canadian society. It also addressed the elimination of expressions of discrimination by guaranteeing both equality and fairness to all under the law, regardless of race or ethnicity.Footnote 5

In 1988, Parliament passed the Canadian Multiculturalism Act which articulates Canada's multiculturalism policy and gives the Minister the mandate to develop and deliver programs and practices to support its implementation. The Act is designed to further integration by emphasizing the right of Canada's ethnic, racial and religious minorities to preserve and enhance their unique cultural heritage while working to achieve the equality of all Canadians in the economic, social, cultural and political life of Canadians.Footnote 6 The Act provides the Government of Canada a wide range of policy and program options for addressing issues related to cultural heritage and identity.

2.1. Program history

The Multiculturalism Program is one means by which the Government of Canada implements the Canadian Multiculturalism Act. Since 1988, multiculturalism has received continued funding for programming aimed at fostering social cohesion and building an inclusive society that is open to, and respectful of, all Canadians.

Multiculturalism is not just about managing ethnic relations but it is also about producing desirable outcomes like inclusion, equality and equity.Footnote 7 Accordingly, multiculturalism must constantly be "re/interpreted according to the times and spaces where the political, economic, social and cultural circumstances change."Footnote 8

Therefore, the focus of multiculturalism policy and programming has evolved over time to reflect the changing Canadian context. Nonetheless, it has consistently promoted the strengths and benefits of diversity while, at the same time, addressed key challenges. In practice, Canadian multiculturalism has five consistent themes. They are: (1) a desire to assist minority communities in their efforts to contribute to Canada; (2) removing barriers to participation; (3) promoting intercultural interaction; (4) encouraging the use of both official languages; and (5) working partnerships (government or federal institutions) to achieve the goals of the policy.Footnote 9

Changes to program objectives over time reflect the policy and program response to a changing context. In 1991, under the Department of Multiculturalism and Citizenship, the department had three priorities:

- race relations and cross-cultural understanding – to promote appreciation, acceptance and implementation of the principles of racial equality and multiculturalism;

- heritage cultures and languages to assist Canadians – to preserve, enhance and share their cultures, languages and ethno-cultural group identities; and

- community support and participation – to support the full and equitable participation of individuals and communities from racial and ethno-cultural minorities in Canadian life.

In 1993, with the creation of the Department of Canadian Heritage, multiculturalism program activities were transferred to the new department and the Program was renewed with new objectives and a focus on the following:

- social justice – building a fair and equitable society;

- civic participation – ensuring that Canadians of all origins participate in the shaping of our communities and country; and

- identity – fostering a society that recognizes and respects and reflects a diversity of cultures so that people of all backgrounds feel a sense of belonging to Canada.

In 1997, the Program's objectives were revised again. They reflected a focus on addressing racism and supporting federal departments and agencies to implement the Canadian Multiculturalism Act. Specifically, there were four objectives:

- ethno-cultural/racial minorities participate in public decision-making (civic participation);

- communities and the broad public engage in informed dialogue and sustained action to combat racism (anti-racism/anti-hate/cross-cultural understanding);

- public institutions eliminate systemic barriers (institutional change); and

- federal policies, programs and services respond to diversity (federal institutional change).

The Multiculturalism portfolio was transferred to CIC/IRCC on October 30, 2008, and remained at CIC/IRCC until November 4, 2015 Footnote 10 at which point it was transferred back to PCH.Footnote 11

The Program's current objectives were developed while the Program was at CIC/IRCC and were approved by Cabinet in July 2009. These objectives focus on social cohesion, with attention directed to perceived faith and culture clashes and a solution based on shared values, anchored in history as the means to improve social cohesion and integration.Footnote 12,Footnote 13

2.2. Program objectives

The current Program objectives were formally implemented on April 1, 2010. These objectives, guided the Program during the period covered by this evaluation:

- build an integrated, socially cohesive society:

- building bridges to promote intercultural understanding;

- fostering citizenship, civic memory, civic pride, and respect for core democratic values grounded in our history; and

- promoting equal opportunity for individuals of all origins.

- improve the responsiveness of institutions to the needs of a diverse population:

- assist federal and public institutions to become more responsive to diversity by integrating multiculturalism into their policy and program development and service delivery.

- Actively engage in discussions on multiculturalism and diversity at the international level:

- promote Canadian approaches to diversity as a successful model while contributing to an international policy dialogue on issues related to multiculturalism.

2.3. Program activities

To advance the objectives and to contribute to the achievement of the program outcomes, the Multiculturalism Program has focused on four programming areas: Gs&Cs (Inter-Action), public outreach and promotion, support to federal and public institutions and international engagement.

2.3.1. Grants and contributions to support projects and events (Inter-Action)

The Citizen Participation Branch manages an annual budget of $8.5 million in Gs&Cs to provide funding to not-for-profit organizations, Crown Corporations, the private sector and non-federal public institutions and First Nations and Inuit governments, band councils and organizations to undertake projects and events that foster an integrated, socially cohesive society. Inter-Action is administered by both National Office (projects) and the five PCH regions (events).

- An annual budget of $5.5 million in funding is available for projects that encourage positive interaction between cultural, religious and ethnic communities. Contributions of up to $2 million are available to organizations for multi-year, long-term community engagement. Inter-Action launches a process by which it issues a call for applications, inviting organizations to submit proposals for project funding. To be eligible for funding, projects must be national in scope.Footnote 14 Contribution agreements are administered by National Headquarters.

- An annual budget of $3 million is available for community-based events that foster intercultural and interfaith understanding, and raise awareness of the contributions of minority groups to Canadian society. Grants of up to $25,000 are available to community organizations. Grants are available on a continuous basis and are administered by the Regions.

While the Program resided at CIC/IRCC, projects were also funded as strategic initiatives. Strategic initiatives were intended to respond to community and regional needs by addressing current and emerging priority issues. Applications fell outside the call for applications process and could be submitted at any time.

2.3.2. Public outreach and promotion

At PCH, the Multiculturalism Policy Unit within the Strategic Policy, Planning and Research Branch undertakes direct public outreach and promotional activities. In accordance with the PCH Communications Branch delivery model, the Communications Branch provides advice and support.

Direct public outreach and promotional activities by the Program are available to the public and are primarily focused on young people. Currently, the unit is responsible for the following outreach and promotion activities: Asian Heritage Month, Black History Month and the Paul Yuzyk Award for Multiculturalism.Footnote 15

2.3.3. Support to federal and public institutions

Support to federal and public institutions is the responsibility of the Multiculturalism Policy Unit. This unit also coordinates two networks: the MCN and the FPTORMI network.

A key activity undertaken by the unit is the coordination and development of the Annual Report on the Operation of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act. This includes providing support to federal departments and agencies for the development of their submissions to the report. The unit also assists federal partners to meet their obligations under the Canadian Multiculturalism Act by offering workshops, tools and guidance for implementing and reporting on multiculturalism-related activities.

2.3.4. International engagement

The Multiculturalism Policy Unit is also the locus for Canada's participation in international agreements and institutions with respect to multiculturalism, diversity, and anti-racism, for example, through contributions to the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination (ICERD) and the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA). The unit ensures that international reporting requirements are fulfilled.

2.4. Program expected outcomes

The immediate and intermediate outcomes associated with each program objective are presented in Table 1 below.Footnote 16

| Objectives | Immediate outcomes | Intermediate outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Build an integrated, socially cohesive society | Program participants and targeted public gain knowledge, develop strategies and take action toward increasing awareness of:

|

Increased civic memory and pride Increased respect for core democratic values Increased intercultural understanding Increased equal opportunity to full participation in society and economy |

| Improve the responsiveness of institutions to the needs of a diverse population | Targeted institutions have external and internal policies and practices that are responsive to the needs of a diverse society | Targeted public institutions demonstrate an increased responsiveness to the needs of a diverse population Increased intercultural understanding Increased equal opportunity to full participation in society and economy |

| Actively engage in discussions on multiculturalism and diversity at the international level | Increased policy awareness in Canada about international approaches to diversity Increased implementation of international best practices in Canadian multiculturalism policy, programming or initiatives |

Increased civic memory and pride Increased respect for core democratic values Increased intercultural understanding Increased equal opportunity to full participation in society and economy |

2.5. Program management and governance

At CIC/IRCC, responsibility for the Multiculturalism Program was dispersed across three CIC/IRCC Branches, including the Citizenship and Multiculturalism Branch, the Integration Program Management Branch, and the Communications Branch.

Similar to the decentralized structure that existed at CIC/IRCC, the delivery model which currently exists at PCH for the Multiculturalism Program involves a number of Branches, including the Strategic Policy, Planning and Research Branch, the Citizen Participation Branch, and the Communications Branch, as well as the Regions. Therefore, responsibility for the Multiculturalism Program is shared by the Director General of Strategic Policy, Planning and Research Branch, who reports to the Assistant Deputy Minister Strategic Policy Planning and Corporate Affairs; the Director General of the Citizen Participation Branch and Regional Directors General who report to the Assistant Deputy Minister Citizenship, Heritage and Regions and the Director General Communications who reports directly to the Deputy Minister.

Overall, policy development, advice, direction, performance measurement and reporting responsibilities and some activities associated with international engagement are carried out by the Multiculturalism Policy Unit within the Strategic Policy, Planning and Research Branch. The Multiculturalism Program's public outreach and promotion activities are also the responsibility of the Multiculturalism Policy Unit. In accordance with the Communications Branch service delivery model, Communications provide advice to the Multiculturalism Policy Unit in delivering its public outreach and promotion activities.

Inter-Action provides organizations with funding to undertake projects and events that support the three Multiculturalism Program objectives. The Director General of the Citizen Participation Branch is responsible for the administration of eligible Inter-Action projects that are national in scope. The Regional Directors General are responsible for the administration of eligible Inter-Action events, which are community-based initiatives.

Given that the Program responsibilities are shared at PCH, effective program governance is important with respect to communication, coordination and decision-making.

2.6. Program resources

Table 2 presents the Program's budget and actual expenditures and full-time equivalents (FTE) between 2011-12 and 2016-17. The Program had a total actual expenditures of approximately $70.7 million of which over half (53%) consisted of Gs&Cs.

Due to the transfer of the Program from PCH to CIC/IRCC in 2008, and the transfer back to PCH (from CIC/IRCC) in 2015, the evaluation relied on financial and human resources data from the CIC/IRCC Reports on Plans and Priorities (RPP) and Departmental Performance Reports (DPR) for 2011-12 to 2015-16; and PCH DPR and RPP for 2015-16 and DPR 2016-17 respectively, as well as the Public Accounts of Canada.

The DPRs and the RPPs do not provide salaries and operations & maintenance (O&M) at the Sub-Program level. Financial information for Sub-Programs in the Program Alignment Architecture (PAA) is available for Vote 5 (Gs&Cs) but not for Vote 1 (salaries and O&M). Therefore, the non-Gs&Cs component below was determined by total expenditures less sub-total Gs&Cs.

The information for 2015-16 is aggregated/combined data for both CIC/IRCC and PCH. This means that the financial and human resources for 2015-16 is grouped under one caption although part of the information is from the CIC/IRCC 2015-16 RPP and other part from the PCH 2015-16 and 2016-17 DPRs. The actual expenditures were $4.16 million and $3.68 million respectively for CIC/IRCC and PCH.

| 2011-12 budget |

2011-12 actual |

2012-13 budget |

2012-13 Actual |

2013-14 Budget |

2013-14 Actual |

2014-15 Budget |

2014-15 Actual |

2015-16 Budget |

2015-16 Actual |

2016-17 Budget |

2016-17 Actual |

Total Actual 2011-12 to 2016-17 |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grants | 3,000,000 | 1,900,000 | 3,000,000 | 1,250,352 | 3,000,000 | 2,005,634 | 3,000,000 | 1,792,227 | N/A | 653,971 | N/A | 2,371,607 | 9,973,791 |

| Contributions | 7,800,000 | 6,600,000 | 7,800,000 | 6,673,122 | 5,600,000 | 4,576,187 | 5,521,316 | 2,251,966 | N/A | 1,961,377 | N/A | 5,394,522 | 27,457,174 |

| Sub-total Grants and Contributions | 10,800,000 | 8,500,000 | 10,800,000 | 7,923,474 | 8,600,000 | 6,581,821 | 8,521,316 | 4,044,193 | N/A | 2,615,348 | N/A | 7,766,129 | 37,430,965 |

| Non-Grants and Contributions components | 15,900,000 | 12,551,465 | 14,200,000 | 7,196,760 | 5,656,922 | 3,211,794 | 4,686,716 | 2,727,411 | N/A | 5,232,929 | N/A | 2,300,424 | 33,220,783 |

| Total expenditures | 26,700,000 | 21,051,465 | 25,000,000 | 15,120,234 | 14,256,922 | 9,793,615 | 13,208,032 | 6,771,604 | 13,049,066 | 7,848,277 | N/A | 10,066,553 | 70,651,748 |

| FTEs | 100 | 53 | 52 | 34 | 52 | 29 | 42 | 28 | 52 | 33* | N/A | 22.1 | N/A |

Source: DPRs and RPPs (CIC/IRCC and PCH)

3. Approach and methodology

The evaluation of the Multiculturalism Program was undertaken in accordance with the 2016–17 to 2020–21 PCH Evaluation Plan and was led by the Evaluation Services Directorate (ESD).

Staff from Office of the Chief Audit Executive supported the evaluation by conducting a review of the Multiculturalism Program's contributions processes and practices. The Policy Research Group (PRG) provided a review of the relevant literature, including a data scan, and implemented a survey of members of the MCN. External consultants provided support for the media analysis, case studies and the expert panel.

The last evaluation was completed in 2012 by CIC/IRCC and had five recommendations:

- Given that the Multiculturalism Program has broadened CIC's mandate (to include longer term integration) and its clientele (to include all Canadians), CIC should ensure that multiculturalism is fully integrated into CIC policies and programming.

- With the relatively small amount of funding available for CIC's Multiculturalism Program, the objectives and expected outcomes of the Program need to be better aligned with available resources and strategically focused on core priorities and needs. The department needs to assess how best it can do this.

- Further efforts are required to improve the transparency and timeliness of the approval process for projects and events.

- The governance for the Multiculturalism Program needs to be improved to support better communication and coordinated decision-making among the responsible branches and units for the Program.

- Given the issues identified with respect to performance measurement, the Program needs to implement a robust performance measurement strategy.

3.1. Scope and timeline

As required by the FAA, and in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results (2016) this evaluation examined the relevance and performance (effectiveness and efficiency) of the Multiculturalism Program, as distinct from the multiculturalism policy and the Canadian Multiculturalism Act. The evaluation was intended to support accountability and inform decision-making. It covered the period from April 1, 2011 to March 31, 2017.

ESD sought input from senior departmental officials on the scope of the evaluation and to identify their information needs. Following consultations with Program Directors General and their Directors and Managers, among others, three key areas were endorsed as areas of emphasis for the evaluation:

- the current environment and context under which the Multiculturalism Program is operating, the major issues that have emerged in the past five years, the effectiveness of the Program response and the interventions and levers used to address the issues

- the alignment of the Program with Government of Canada and PCH direction and priorities

- an assessment of the effectiveness and efficiency of the Program design and delivery

Although the evaluation covered the period 2011-12 to 2016-17, to ensure that the evaluation findings would support PCH management decisions, the evaluation focused on the relevance and performance of the Program's activities for the period following the transfer of the Program to PCH.

The Inter-Action call for applications occurred in 2016-17, within the timeframe of this evaluation, but decisions were made in fiscal year 2017-18. While the decision process for the 2017 call was included in this evaluation, an analysis of outcomes for projects occurring in 2017-18 was out of scope.

3.2. Calibration

To mitigate the challenges associated with timely delivery of a high risk and complex evaluation, coverage of program activities was calibrated as follows:

- The evaluation covered all program activities, but with limited coverage of the events component of Inter-Action (grants of low dollar value (less than $25,000) and low risk).

- The file review was limited to the assessment of 11 project files which were transferred from CIC/IRCC and 13 files that were recommended by CIC/IRCC, but approved by PCH.

- As noted above, the evaluation focused on PCH program delivery to ensure that the evaluation would be useful to guide PCH multiculturalism programming going forward.

3.3. Evaluation issues and questions

The evaluation was designed to address the three broad areas of focus, while responding to the issues of relevance and performance. Table 3 presents the evaluation questions that were addressed by this evaluation. These questions were endorsed by the Program's senior management during consultations in May 2017, and by the Results, Integrated Planning and Evaluation Committee (RIPEC) in June 2017.

Details related to the indicators, data sources and data collection methods are provided in the evaluation matrix presented in Annex A.

Table 3: evaluation questions by core issue

| Core Issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Ongoing need for the Program |

|

| Alignment with Government priorities and federal roles and responsibilities |

|

| Alignment with CIC/IRCC and PCH mandate and priorities |

|

| Core Issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Achievement of expected outcomes |

|

| Core Issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Demonstration of efficiency |

|

| Core Issue | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|

| Design and delivery |

|

| Performance measurement |

|

3.4. Data collection methods

The methodology included a combination of qualitative and quantitative data collection methods and primary and secondary sources of information to address the evaluation questions and to provide representation and feedback from a range of stakeholders involved in the Multiculturalism Program. The methods are described in the following sections.

3.4.1. Document and administrative data review

The document review collected and analyzed documentation relevant to the Multiculturalism Program. The document types consulted included:

- speeches from the throne, budget announcements

- departmental (CIC/IRCC and PCH) and strategic documents

- legislation (e.g., Canadian Multiculturalism Act. Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms)

- PCH and CIC/IRCC RPPs and DPRs, including financial information

- program-specific documents (e.g., Inter-Action Terms and Conditions (Ts&Cs), funding guidelines and application and reporting forms)

- project files (applications, contribution agreements, interim and final activity reports)

- presentations

- minutes of meetings of the MCN and the FPTORMI network

- Annual Reports on the Operation of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act

- public outreach and promotion materials and web statistics

- funding agreements and, memoranda of understanding

- information from the CIC/IRCC and PCH Grants and Contributions Information Management System (GCIMS) and administrative data on Gs&Cs, maintained by the Program

3.4.2. File review

A review of 24 files was conducted, in collaboration with the Office of the Chief Audit Executive. The file review was limited to the assessment of 11 project files which were transferred from CIC/IRCC and 13 files from the 2015 CIC/IRCC call for applications that were recommended by CIC/IRCC and then approved by PCH following the transfer of the Program. Grants in support of events were not reviewed as they were of low materiality and risk.

The Office of the Chief Audit Executive examined the compliance of payments with approved contribution agreements and the Program's Ts&Cs; compliance with Treasury Board policy instruments' requirements to include monitoring and reporting requirements in contribution agreements; and the completeness of files transferred by CIC/IRCC to support PCH's administration of payments.

Qualitative performance information for projects funded through Inter-Action was available, but was not analyzed and rolled up. Therefore, ESD examined the contribution agreements and the final activity reports to assess if the funded projects had contributed to the achievement of the objectives and outcomes of the Program and to identify the impact on funding recipients of the transfer of the Program to PCH from CIC/IRCC.

3.4.3. Data scan

PRG conducted a scan of available data to provide an analysis of Canadian' perceptions of immigration, multiculturalism, racism and related topics. This analysis was based on a review of public opinion research over time as well as data published by reputable sources, including Statistics Canada and public opinion research firms.

3.4.4. Literature review

The literature review examined the evaluation questions related to relevance, in particular emerging issues, views on multiculturalism and immigration and evidence of the continued need for the Program. The literature review also provided some evidence of the effectiveness of the policy levers and instruments used by the Program to achieve its objectives.

The review consisted of the collection and analysis of various information such as studies, research reports, scientific journal articles, websites and other sources of recent information (national and international) to answer the evaluation questions related to the relevance and performance of the Multiculturalism Program.

3.4.5. Interviews with stakeholders

The 32 semi-structured interviews conducted with key stakeholders collected opinions and perceptions on relevance and performance and on the design, implementation and efficiency of aspects of the Multiculturalism Program. The interviews also served to identify additional areas for a more in-depth review through other data sources. Key informants included 22 PCH national and regional management and program staff and 10 external stakeholders, including: members of the MCN (n=2); provincial multiculturalism representatives participating on the FPTORMI network (n=4) and funding recipients (n=4).

3.4.6. Survey of members of the Multiculturalism Champions Network

A survey of members of the MCN was conducted to gather input on the effectiveness and levels of satisfaction with the mandate and the role of the Network and to seek input on how the Multiculturalism Program can better support the multicultural champions in implementing the Canadian Multiculturalism Act in their departments and agencies. The on-line survey was disseminated to 147 past and current members of MCN. Thirty-three multiculturalism champions participated in the survey for a response rate of 22.5%. While the response rate was low, findings were validated through other lines of evidence, including MCN meeting minutes and key informant interviews.

3.4.7. Case studies

Five case studies were conducted with organizations (1 small, 2 medium-sized and 2 large) that received project funding either through Inter-Action or the strategic initiatives stream during the period covered by the evaluation. The case studies provided information on funding recipients' perceptions of the relevance of the Multiculturalism Program and provided more in-depth insights on the contribution of projects to the achievement of the objectives and outcomes of the Program and the challenges and successes of the projects. The methodology used for each of the case studies included reviews of project documentation and program administrative data maintained by CIC/IRCC and PCH and semi-structured telephone interviews with project proponents, project partners, and PCH program officers familiar with the project.

3.4.8. Media analysis

A search of one national and four regional print media was conducted to support the assessment of relevance. The media analysis sought to identify emerging issues and Canadians' views on multiculturalism and related topics, and to identify regional/provincial differences. Coverage of Canadian multiculturalism and related topics were identified through a keyword search Footnote 17 of MediaScope, a product of the PCH Communications Branch, which provides daily clippings packages comprised of print, web, TV, radio and social media coverage that is relevant to PCH, its ministers and its agencies.Footnote 18 The search included The Globe and Mail, The Halifax Chronicle Herald, La Presse, the Winnipeg Free Press and The Vancouver Sun. The analysis covered the last two years of the evaluation period – 2015-16 through 2016-17.

The search returned a total of 143 English-language articles, of which 102 were deemed to be relevant. A systematic random sampling technique was applied for each newspaper in which every fourth article was selected, resulting in 36 English-language articles selected for analysis. The search of La Presse returned 36 articles of which 17 were deemed relevant. Fourteen articles were retained for analysis. In total, 50 articles were reviewed. The quantitative analysis focused on the frequency of the following: type of story (news article, commentary or opinion piece, feature article or letter to the editor), positive, negative or neutral sentiment; the focus of the story; calls for government action; and key themes and emerging issues. A qualitative analysis was conducted which led to the identification of key themes.

3.4.9. Expert panel

An expert panel was held with representatives from outside the Multiculturalism Program's partner and beneficiary circles. Experts included four representatives from academia and one practitioner. The expert panel was held near the end of the data collection phase of the evaluation. The participants in the expert panel served as a sounding board to test the evaluation's preliminary findings. The expert panel was held via WebEx, and a summary of the discussion was prepared.

3.5. Scale for presenting results

Table 4 presents the scale used to present findings.

| All | Findings reflect the views and opinions of 100% of the interviewees. |

|---|---|

| Majority/Most | Findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 75% but less than 100% of interviewees. |

| Many | Findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 50% but less than 75% of interviewees. |

| Some | Findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 25% but less than 50% of interviewees. |

| A few | Findings reflect the views and opinions of at least two respondents but less than 25% of interviewees. |

3.6. Constraints, limits and mitigation strategies

The following are some of the constraints associated with the evaluation:

- Historical information and data for the period 2011-12 to November 2015 while the Program was at CIC/IRCC was limited. The mitigation strategy was to interview Multiculturalism Program staff who had migrated with the Program from CIC/IRCC to PCH and to use multiple lines of evidence to gather information on all aspects of the Program.

- Completeness and reliability of the data in the CIC/IRCC Gs&Cs database could not be confirmed. Results obtained through the analysis of data in the CIC/IRCC database were compared with CIC/IRCC's publically reported data (DPR, RPP, Public Accounts etc.).

- Two separate databases for Gs&Cs information. Not all of the information from the CIC/IRCC database was migrated, limiting the depth of analysis.

- The recommendation relating to performance measurement from the 2012 evaluation was not fully addressed. As a result the current evaluation experienced many of the same issues: predominately output data and limited outcome data to assess the Program's performance. Indicators changed across the years covered by the evaluation making trend analysis difficult.

- Challenges associated with measuring the impact of the Program on Canadians and attributing changes to the Program. Gs&Cs funding, and as a result its reach, is limited.

- Observations obtained through interviews, the low response rate for the multiculturalism champions survey and the limited number of case studies and interviews with funding recipients limits the generalizability of results. The latter is mitigated, to a certain extent, through the use of multiple lines of evidence.

4. Findings

4.1. Relevance

This section presents the findings of the evaluation related to the following issues of relevance:

- ongoing need for the Program;

- alignment with Government of Canada priorities; and

- alignment with PCH mandate and priorities.

4.1.1. Relevance: ongoing need for the program

Evaluation questions:

What is the current Program context and what are the emerging issues? How have Canadians' views of multiculturalism evolved over time? What are the drivers for these changes?

How has the Program adapted/responded to the changing context? What have been the levers/instruments used to respond?

What are the implications of the context for PCH multiculturalism programming going forward?

Key findings:

The Multiculturalism Program remains relevant. It is one means by which the Government of Canada implements the Canadian Multiculturalism Act and the multiculturalism policy.

While Canadians are generally positive about immigration, visible minorities and multiculturalism, there continues to be a need to respond to the challenges associated with an increasingly diverse Canada, including: addressing the controversies associated with increased levels of immigration; the continued incidence of religious intolerance, racism and discrimination and hate crimes; the rise of populism; and the underlying factors that contribute to the socio-economic disadvantages experienced by certain groups.

The increased number of organizations that sought funding from PCH for multiculturalism programming for the 2017 call for applications, and anecdotal evidence that there is limited funding available through the provincial and municipal levels, further support the continued need for the Multiculturalism Program.

Within the context of limited resources, the Program's activities have addressed some of the issues. However, during the period of the evaluation, the Program did not focus on issues of racism and discrimination, provide support for institutional change to address systemic issues, or provide project funding to address unique regional or local needs.

Evaluation evidence indicates that the ability of the Program to address these gaps is constrained by a number of factors, including the following:

- The capacity to achieve the broad policy objectives of the Act;

- A lack of evidence to inform policy and program development;

- A lack of performance data to provide evidence on whether the Program's activities are effective, or to make programming adjustments; and

- The Program's funding and delivery model.

The extent to which there is a continued need for the Multiculturalism Program was assessed by looking at the Canadians' attitudes toward diversity and multiculturalism, the challenges associated with Canada's increasing diversity, and the extent to which the Multiculturalism Program has responded to these challenges.

The Multiculturalism Program is one means by which the Government of Canada implements the Canadian Multiculturalism Act. The Act regards race, national or ethnic origin, color and religion as a fundamental characteristic of Canadian society and is committed to a policy of multiculturalism designed to preserve and enhance the multicultural heritage of Canadians while working to achieve the equality of all Canadians in the economic, social, cultural and political life of Canada."Footnote 19 Implementation of the Canadian Multiculturalism Act is supported by a range of other legislation and programs, that together aim to address challenges related to diversity and to ensure full and equitable participation of all Canadians in the larger society.

The continued need for multiculturalism programming is supported by data which indicates that Canadian society is becoming increasingly diverse and issues are becoming more complex (e.g., radicalization, religious intolerance against Muslims, anti-Semitism, and rising populism). Furthermore, hate crimes continue to be directed at certain groups and longstanding issues of inequitable treatment of certain visible minority groups persist. As Canada's population becomes increasingly diverse, the need to address the challenges that accompany diversity and the barriers experienced by certain groups becomes ever more important.

Diversity within Canada

Diversity within Canada continues to grow and become more complex with over 250 ethnicities, a larger visible minority population, and increased religious diversity. Canada has always been a country founded on immigration, with a history of ethnocultural, linguistic and religious diversity. However, as the Census 2016 data below shows, Canada is becoming more diverse:Footnote 20

- Over one-fifth (21.9%) of Canada's population was foreign born in 2016, up from 19.8% in the 2006 Census and 20.6% in the 2011 National Household Survey (NHS). Statistics Canada projects this could reach between 24.5% and 30.0% by 2036.

- As well as high levels of foreign born Canadians, the source countries have also changed in recent years. In 2016, Canada was home to 250 ethnic origins. European countries accounted for 75% of all Canadian immigrants in 1966, 16% in 2010 and 11.6% in 2016. In 2016, Asian countries accounted for 7 of the top 10 countries of birth of recent immigrants in 2016. 13.4% of recent immigrants were born in Africa.

- While Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal are still the place of residence of over half of all immigrants and recent immigrants to Canada, more immigrants are settling in the Prairies and in the Atlantic provinces.

- In 2016, 22.3% of the population identified as belonging to a visible minority, a five-fold increase between 1981 and 2016. Statistics Canada projects that the population identifying as visible minority could reach 34.4% by 2036. The visible minority population is made up of a number of groups, which themselves are diversified in many respects. South Asians, Chinese and Blacks were the three largest visible minority groups, each with a population exceeding one million.

The religious composition of the country is also changing, with the largest increases seen in Muslim, Sikh and Buddhist denominations. In 2011, 7.2% of Canada's population reported affiliation with one of these religions. This was up from 4.9% a decade earlier, as recorded in the 2001 Census. In 2011, people who identified themselves as Muslim made up 3.2% of the population, Hindu 1.5%, Sikh 1.4%, Buddhist 1.1% and Jewish 1.0%.Footnote 21

Tolerance and attitudes

Canada ranked at the top of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries as the most tolerant country in terms of community acceptance of minority groups and migrants - 84% compared to 61% OECD average.Footnote 22

Attitudes toward immigration and immigrants

Views on immigration can often provide insights to how Canadians will respond to cultural diversity and visible minorities. Canadians' attitudes toward immigration and immigrants are generally positive. A 2016 Focus Canada public opinion survey found the following attitudes with respect to immigration:Footnote 23

- When asked whether they are of the view that there is too much immigration in Canada overall, a majority (58%) of Canadians disagree with the statement, a trend consistent over the past decade.

- Eight-in-ten Canadians (80%) believe that immigration has a positive impact on the economy of Canada overall, a finding consistent with those dating back more than 15 years. Furthermore, that view is shared by at least three-quarters (75%) of respondents in every demographic group across the country. The proportion of Canadians who do not agree that the economic impact of immigration has been positive stands at 16%.

- The number of Canadians expressing the view that too many immigrants do not adopt Canadian values is declining. Just over half (54%) of Canadians agree that there are too many immigrants coming into this country who are not adopting Canadian values, down 11 points from 2015 and continuing a downward trend starting in 2012. Furthermore, agreement with this point of view is at its lowest point since 1972, when it stood at 72%. Agreement with this point of view is highest in Quebec (57%) and the Prairies (57%).

Canadians are satisfied with how well immigrants are integrating. Two thirds of Canadians (67%) say they are "satisfied" with how well new immigrants are integrating into their communities.Footnote 24

However, a Leger Marketing survey conducted for The Association for Canadian Studies (2017) found that opinions of immigrants decreased from 75% in 2013 to 72% in 2017. Footnote 25

Attitudes toward Muslims and Jews

The Leger Marketing survey (2017) examined Canadians attitudes toward selected groups. The survey found that Canadians expressed more positive attitudes toward certain groups in 2017 when compared to 2013.Footnote 26 Attitudes toward Muslims were more positive in 2017 (55%, up from 50% in 2013) as were views toward Jews (74%, up from 70% in 2013).

Attitudes toward multiculturalism

Multiculturalism is viewed as a core component of our national identity. Public opinion research by Leger Marketing found that overall, Canadians are positive toward multiculturalism (75% overall). Support was strong across all age groups, with the strongest support coming from youth under the age of 24 years (81%) and lowest in the 65+ age group (71%). French speaking Canadians were less supportive (65%) than English speaking Canadians (76%).Footnote 27

When asked what makes them proud to be Canadian, 35% of Canadians selected multiculturalism placing it 9th out of 78 items. Open-mindedness toward people who are different placed third with 49% of respondents selecting this item.Footnote 28

The media analysis supported the finding that Canadians generally have positive views toward multiculturalism. The majority of stories examined (92%) were positive or neutral towards multiculturalism, portraying it as contributing to social cohesion. Stories on relationships between racialized Canadians tended to focus on tensions between groups but also advocated for anti-racist and anti-discrimination perspectives and practices.

A majority of articles (70%) proposed aspects of Canadian multiculturalism as solutions to current issues. These included seeing the integration of immigrants as a means to bolster the economy, strengthen society (through the contributions of successful immigrants), and as a response to an aging population; advancing Canadian multiculturalism, interculturalism, tolerance and respect for others as bound up with Canadian identity and pride, as a means to strengthening Canadian society; and advocating the role of diverse cultural expressions in building greater intercultural and interfaith understanding.

Sense of pride and belonging to Canada

Immigrants

Overall, evidence indicates that immigrants identify with Canadian values. As noted by one observer, there is no reason to fear that the gravitational pull of liberal democracy is weakening in Canada. Recent waves of immigrants are no different from earlier waves in their pattern of convergence toward a shared liberal democratic consensus.Footnote 29

The 2013 Statistic Canada General Social Survey (GSS) on Canadian Identity found: Footnote 30

- 79% of first generation Canadians (immigrants to Canada) reported being proud or very proud to be Canadian. Second generation Canadians expressed high levels of pride in Canada (86%) compared with 87% of all Canadians age 15 years and older.

- 66% of second generation immigrants (i.e., children of immigrants) were very proud to be Canadian. This was significantly higher than pride among other non-immigrant Canadians (third generation or more) (59%), and slightly higher than the proportion of first generation immigrants (63%).

A 2017 case study of Muslim youth in Montreal, conducted by Hicham Tiflati, a Research Associate at McGill University, explored the latter's sense of belonging to Quebec and to Canada, found that the youth were proud of their Muslim identity and did not view it as incompatible with their identity as Canadians despite some challenges in reconciling certain religious practices with social norms.Footnote 31

Visible minorities

The GSS on Canadian Identity found that those who identify as a visible minority reported the highest levels of sense of belonging to Canada (94%) compared to 93% for Canadians generally.Footnote 32

Evidence from the GSS also found that visible minorities are proud to be Canadian. Pride among visible minorities mirrored patterns observed for immigrants. While visible minorities were equally as likely as other Canadians to be very proud to be Canadian (62% and 61%), overall feelings of pride in being Canadian were higher (91% versus 86%).Footnote 33

Challenges associated with diversity and multiculturalism

Although Canadians have generally positive views toward immigration, visible minorities and multiculturalism, challenges associated with diversity and multiculturalism exist in Canada. Not all Canadians hold positive views toward immigration and visible minorities. Economic differences persist and discrimination and hate crimes remain issues.

Multiculturalism has come under considerable challenge, especially in Europe.Footnote 34,Footnote 35 Events like the September 11 attacks and the 2005 London bombings have led to a range of responses at both government and community levels in many countries to address social schisms, particularly those related to religion. These include a reappraisal of previously-held understandings about integration and settlement, and recognition of the need to identify and act on early warning signs of unrest and tension. Some initiatives have been security-focused, while others aim to build cohesion at the community level.Footnote 36

Many key informants noted that Canada needs to be mindful of these developments internationally, and remain vigilant as we are not immune to right wing extremist forces. These views are supported by the literature which provides evidence that extreme right-wing forces exist in Canada and that these forces have tended to center on preserving the Canadian national identity, with an emphasis on race, but that more recently this has changed to include religion, language and values. "The current crop of far-right activists use the term cultural nationalism as a way of muting the impact and minimizing the issue of race."Footnote 37 Furthermore, a national study of right-wing extremism in Canada in 2015 identified more than 100 active right-wing extremist groups.Footnote 38

In spite of generally positive views toward immigration and multiculturalism in Canada, multiculturalism is not without its critics. Some of these critics argue that multiculturalism has "undermined Canadian identity and values, created divided loyalties, fostered ethnic separation and prevented the integration of newcomers."Footnote 39 Further, some critics suggest that Canadian "multiculturalism encourages immigrants to engage in issues of the motherland, develop dual political loyalties, and import 'old world' conflicts, thus compromising opportunities to develop a strong Canadian identity and a sense of allegiance to Canada."Footnote 40

Canada also encounters challenges associated with increased diversity including: intolerance, prejudice and discrimination which constitute barriers to equality of all Canadians in the economic, social, cultural and political life of Canada and threaten social cohesion.Footnote 41

Almost all provincial and PCH regional key informants provided evidence from their respective jurisdictions of tensions, either between ethnocultural communities such as between newcomers and refugees, between minority groups and indigenous peoples and/or between visible minorities and non-minorities. Key informants also provided evidence of religious intolerance in their jurisdictions. Provincial or regional differences emerged in terms of the targets of discrimination and intolerance.

Not all Canadians view immigration levels positively, nor do all Canadians believe in immigrants retaining their own customs and languages. Public opinion survey data conducted by Angus ReidFootnote 42 in 2016 found:

- A significant number (37%) agree that immigration levels are too high. Note that a poll conducted by Leger Marketing arrived at a similar result (38%).

- More than two-thirds of Canadians say minorities should do more to fit into mainstream society (68%) rather than keep their own custom and languages.

Although down 11 points from 2015 and continuing a downward trend starting in 2012, over half (54%) of Canadians agree that there are too many immigrants coming into this country who are not adopting Canadian values.Footnote 43

The majority of Canadians generally agree that multiculturalism contributes to social cohesion, has a positive impact on ethnic and religious minorities, and makes it easier for newcomers to adapt to, and adopt shared Canadian values and promotes reasonable accommodation of cultural practices, including practices about which the respondents might feel uncomfortable. However, the survey also found that in the public's mind, there are limits to reasonable accommodation. When asked, a majority of respondents indicated that multiculturalism appears to open the door to people pursuing certain cultural practices that are not compatible with Canadian laws and norms. Of those who believe this, 46 per cent say the government should discourage such practices, while 28 per cent said the government should not. When asked to provide examples of such practices, 28 per cent identified the wearing of religious garb – hijabs, burkas and turbans – in public or security settings, as well as the wearing of turbans and hijabs by members of the police and RCMP. A further 10 per cent listed religious practices in general, and 8 per cent cited observance of religious holidays as incompatible. In comparison, Sharia law and honor killing scored low, at 5 per cent and 4 per cent, respectively.Footnote 44

These responses to other questions concerning multiculturalism reveal a troubling schism between theoretical acceptance and practical application, indicating a pressing need for an ongoing, national dialogue (i.e. limits to reasonable accommodation).Footnote 45

The media analysis also supported the evidence that not all Canadians support multiculturalism. Half of all the articles that had a positive or neutral overall tone reported on negative attitudes of Canadians towards multiculturalism and related issues. In fact, fully half of the entire media sample reported on the negative attitudes of Canadians. These were primarily concerned with Canadians' frustration with the lack of assimilation of new Canadians.

Religious minorities, including Muslims, Indigenous religions and Eastern religions that practice meditation were discussed in terms of challenges with multiculturalism again posited as a solution, particularly in English Canada (British Columbia and Ontario), where two stories reported on negative attitudes towards the teaching of world religions in public schools, and one story opposed Islamophobia and religious intolerance more generally. In Quebec, articles examined reflect a wider public debate that is taking place in the media as to the best way to integrate religious minorities, particularly Muslims, into the larger social fabric.

Vulnerable populations

Certain groups continue to be particularly vulnerable to systemic issues which continue to exist throughout the policies, practices and programs of all sectors, including housing, health care, education and employment and the criminal justice system, as evident by data related to unemployment, underemployment, income and social segregation.

Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous Peoples continue to encounter inequities relative to the general population. Statistics Canada data shows that:

- Indigenous Peoples have an unemployment rate (14%) 2.1 times the national rate; have a median income 60% of the national average.

- In 2015/2016, Indigenous adults were overrepresented in admissions to provincial and territorial correctional services, as they accounted for 26% of admissions while representing about 3% of the Canadian adult population. The overrepresentation of Indigenous adults was more pronounced for females than males. Footnote 46

- Indigenous females accounted for 38% of female admissions to provincial and territorial sentenced custody, while the comparable figure for Indigenous males was 26%. In the federal correctional services, Indigenous females accounted for 31% of female admissions to sentenced custody, while the figure for Indigenous males was 23%.Footnote 47

Minority groups

The data has consistently demonstrated that certain Canadian minority groups are most vulnerable to being victims of hate crimes – particularly those identifying as Black or Jewish. Blacks were the target of 214 incidents of police-reported hate crimes motivated by race/ethnicity in 2016. In terms of hate crimes motivated by religion, there were 221 incidents of police-reported hate crimes against the Jewish religion. Muslims were also a target, but to a lesser extent, with 139 incidents of police-reported hate crimes in 2016.

Recent literature has continued to draw attention to discrimination against Black Canadians and differences in various outcomes between Blacks and other populations. The literature highlights the challenges that Black Canadians face in accessing mainstream institutions:

Negative portrayals in the media, employment discrimination, racial profiling, negative valuations in social attitude surveys, and disproportionate education outcomes and sentencing rates for violent crime play a role, whether as joint causes or effects, in how black Canadians face steep barriers in accessing mainstream institutions […]. They reflect socio-economic and symbolic disadvantages and capture how being labeled "black" is synonymous with disvalue.Footnote 48

As noted by one researcher, "Hate crimes are direct threats to the principles of Canadian multiculturalism, and have the potential to present obstacles to the ability or willingness of affected communities to engage in civic life."Footnote 49

Anti-Semitic incidents have been on the rise over the past 10 years. Data gathered by B'nai Brith Canada, a Jewish advocacy organization, based on phone calls to their anti-hate hotline and police data, show that in 2016 there were 1,728 anti-Semitic incidents reported, a 26 per cent increase from 2015 and a 6 per cent increase from the previous high in 2014.Footnote 50 2016 also saw a dramatic rise in incidents involving Holocaust denial. In 2015, Holocaust denial made up just five per cent of the total number of anti-Semitic incidents in Canada. In 2016, that number increased to 20 per cent.Footnote 51

Statistics Canada publishes annual data on police-reported hate crimes in Canada, providing an important source of information on trends and differences between populations. Key findings from 2016 Statistics Canada dataFootnote 52 show the following:

- In 2016, police reported 1,409 criminal incidents in Canada that were motivated by hate, marking an increase of 3% or 47 more incidents than were reported the previous year.Footnote 53

- Nearly half (48%) of hate crimes targeted a race or ethnic group and one-third targeted religious minorities (33%).

- The increase was a result of more incidents targeting South Asians (+24 for a total of 72) and Arabs or West Asians (+20 for a total of 112), the Jewish population (+43 for a total of 221) and people based on their sexual orientation (+35 for a total of 176).

- Hate crimes targeting Blacks declined by 4% from 2015 to 2016 but remained the most common type of hate crime related to race or ethnicity (214 of 666 crimes or 32%).

- Increases in hate crimes against the Jewish population were seen in Ontario (+31), Quebec (+11) and Manitoba (+7).

- Hate crimes against Muslims - which had increased in 2015 - declined in 2016. There were 139 targeting Muslims (20 fewer than in 2015). Most of that decline was in Quebec, with 16 fewer reported anti-Muslim hate crimes in the province that year. This decrease follows "a notable increase in hate crimes against the Muslim population" in 2015. That year, there was a 61 per cent increase in hate crimes targeting Muslims, with 159 reported incidents.

Data from an Environics Institute survey in 2016 found that 35% of Muslim Canadians reported experiencing discrimination or unfair treatment in the past five years due to their religion ethnicity, language or race,Footnote 54 compared to 21% for the Canadian population overall.

Data from the 2014 GSS found that persons who self-identify as belonging to a visible minority were less likely than those who do not self-identify in this way to say that they felt very safe walking alone in their neighborhood after dark (44% versus 54%).Footnote 55

- Among visible minority groups, Arabs (15%) and West Asians (16%) were most likely to say they felt unsafe walking alone in their neighborhood after dark.

- Among West Asian or Arab women, 25% reported feeling unsafe walking alone in their neighborhood after dark. This marks a change when compared with perceptions of personal safety 10 years earlier, when the sense of safety felt by Arabs and West Asians was comparable to that of other visible minorities.

Immigrants

In 2011, the non-immigrant population of Canada earned $1,670 more (on average) than immigrants in Canada. Immigrants also had higher rates of low income (6.8%), lower rates of labor force participation (3.6%) and employment (4.0%), but were more likely to work full-time (1.6%) than the Canadian born population.

Continued need for federal government funding for multiculturalism programming

Another way to look at the need for the Program is to look at the demand for funding, relative to the funding available to organizations for multiculturalism programming. The increased demand for funding resulting from the 2017 Inter-Action call for applications and anecdotal evidence of limited funding available from other sources further support the continued need for the Program.