Antisemitism in Ontario’s K-12 Schools

© Robert Brym, FRSC (2025)

S.D. Clark Professor of Sociology, Emeritus

University of Toronto

robert.brym@utoronto.ca

On this page

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- Executive Summary

- 1. The social distribution of antisemitic incidents

- 2. What made the incidents antisemitic?

- 3. What happened during the incidents?

- 4. Reactions of victims and schools

- 5. Conclusion

- About the Author

List of Tables

- Table 1 – Incidents by metropolitan census area, in percent

- Table 2 – Question: “At the time of the incident, what type of school did your child attend?” in percent

- Table 3 – Question: “In which school board was your child’s school at the time of the incident?” in percent

- Table 4 – Question: “In your opinion, what was it about the incident that made it antisemitic? Please select as many of the following options as apply” in percent

- Table 5 – Question: “What happened during the incident? Please select as many of the following options as apply” in percent

- Table 6 – Question: “How did your child react to the incident? Please select all options that apply” in percent

- Table 7 – Question: “What did your child’s school do about the incident? Please select all options that apply” in percent

- Table 8 – Question: “How long did it take for the school to begin taking action in response to the incident?” in percent

- Table 9 – Question: “After the incident, did you or will you move your child to a(n) _____________ school?” in percent

List of Figures

- Figure 1 – Incidents by month, October 2023 to January 2025, in percent

- Figure 2 – Incidents by grade, K-12

Alternate format

Antisemitism in Ontario’s K-12 Schools [PDF version - 2.20 MB]

Executive Summary

Since October 7th, 2023 – and even before – there have been growing concerns that Jewish students in K-12 schools are experiencing antisemitism. Much of this was based on anecdotal reports or complaints that remained unresolved or undocumented. To obtain a clearer picture of the situation, the Office of the Special Envoy on Preserving Holocaust Remembrance and Combatting Antisemitism commissioned Professor Robert Brym to conduct a survey on the subject in Ontario, where most Jewish children in Canada reside. The survey examines the prevalence, nature, and impact of antisemitic incidents in elementary and secondary schools across the province.

This report on the survey demonstrates the existence of a disjuncture between (1) the desire of Ontario schools to ensure that all students feel respected, included, and valued and (2) the treatment of their Jewish students. Its main source of information is a survey of 599 Jewish parents and their reports of 781 antisemitic incidents in Ontario K-12 schools. Antisemitic incidents are defined as those that parents and their children consider antisemitic. It is estimated that the 781 incidents reported here were directly experienced by at least 10% of Ontario’s approximately 30,000 Jewish school-age children.Footnote 1 The survey, available online in French and English, was in the field from late January to early April 2025, and it covers incidents that took place in the 16 months from October 2023 to January 2025. The survey sample is roughly representative of the two-thirds of Ontario Jews most closely tied to the Jewish community by organizational membership, belief, and identity.

Key findings of the survey include the following:

- More than 40% of antisemitic incidents involved Nazi salutes, assertions that Hitler should have finished the job, and the like. Fewer than 60% of antisemitic incidents refer to Israel or the Israel-Hamas war.

- Nearly one in six antisemitic incidents were initiated or approved by a teacher or involve a school-sanctioned activity.

- Just over two-thirds of antisemitic incidents occurred in English public schools and nearly one-fifth were directed at Jewish private schools. Fourteen percent of incidents occurred in French, Catholic, and non-Jewish private schools.

- Nearly three-quarters of antisemitic incidents took place in the Toronto District School Board, the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board, and the York Region District School Board.

- The most common emotional reactions to antisemitic incidents on the part of their victims involved anger (31%), fear of returning to school or of being bullied (nearly 27%) and worrying about losing non-Jewish friends and being socially isolated (more than 27%).

- Some children insisted that their parents not report an antisemitic incident, fearing it would become public and they would consequently become the target of increased harassment or bullying. Some removed clothing and jewelry with Jewish symbols and Hebrew lettering so they would not be identified as Jewish.

- Forty-nine percent of antisemitic incidents reported to school authorities were not investigated. In another nearly 9% of cases, school authorities denied the incident was antisemitic or recommended that the victim be removed from the school permanently or attend school virtually.

- In under one-third of cases reported to school authorities, schools responded by providing counselling for the targeted child or the perpetrator, taking punitive action against the perpetrator, creating or modifying a program to promote ethnic, racial, and religious tolerance of Jews, or reporting the incident to the police.

- Because of antisemitic incidents experienced by their children, 16% of parents moved their children to another school or are considering doing so. Some moved house to enroll their children in different schools.

- At 39% of the total, Jewish private schools are the most frequent choice of parents who have moved or are moving their children to new schools.

1. The social distribution of antisemitic incidents

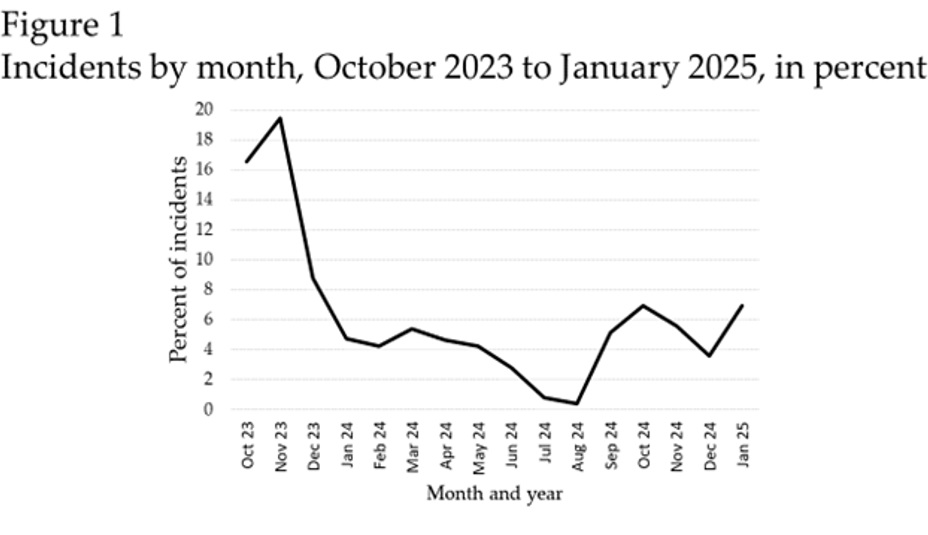

The 7 October 2023 Hamas attack on Israel and the ensuing Israeli retaliation in Gaza provoked a three-month outburst of hostility against Jewish K-12 students such as never before seen in Ontario schools. The survey on which this report is based covers the 16-months between October 2023 and January 2025. Nearly 45% of incidents recorded by the survey occurred in the 78 days between 7 October 2023 and the start of the December 2023 school holiday (Figure 1). Excluding the July-August 2024 summer break, hostilities levelled off at about one-fifth the level witnessed in October-December 2023. However, a resurgence of hostilities to about one-third the October-December 2023 level took place around the time of the one-year anniversary of the 7 October 2023 Hamas attack and the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas war.

Figure 1 – Incidents by month, October 2023 to January 2025, in percent - text version

| Date | Percent of Incidents |

|---|---|

| Oct 23 | 16.53 |

| Nov 23 | 19.42 |

| Dec 23 | 8.78 |

| Jan 24 | 4.75 |

| Feb 24 | 4.24 |

| Mar 24 | 5.37 |

| Apr 24 | 4.65 |

| May 24 | 4.24 |

| Jun 24 | 2.79 |

| Jul 24 | 0.83 |

| Aug 24 | 0.41 |

| Sep 24 | 5.17 |

| Oct 24 | 6.92 |

| Nov 24 | 5.58 |

| Dec 24 | 3.62 |

| Jan 25 | 6.92 |

End of SectionEnd of sectionNearly 82% of reported incidents took place in metropolitan Toronto (61%) and metropolitan Ottawa (21%), Ontario’s major Jewish population centres (Table 1). Nearly 86% of reported incidents occurred in English public schools and Jewish private schools (67% and 19%, respectively; Table 2). Fewer than 8% of incident reports took place in French public schools, and fewer than 5% in private non-Jewish schools. English Catholic and French Catholic schools account for 1.5% and 0.1% of cases, respectively.

| Census metropolitan area | Percent |

|---|---|

| Toronto | 60.8 |

| OttawaTable 1 note * | 20.9 |

| London | 2.6 |

| Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo | 1.5 |

| Hamilton | 1.5 |

| Kingston | 1.2 |

| Barrie | 0.9 |

| Guelph | 0.9 |

| Oshawa | 0.6 |

| Windsor | 0.5 |

| Greater Sudbury | 0.4 |

| Other | 8.2 |

| Total | 100.0 |

Table 1 notes

- Table 1 note *

-

The Ontario part of the Ottawa-Gatineau census metropolitan area.

| School Boards | Percent |

|---|---|

| English public | 66.8 |

| Private Jewish | 19.0 |

| French public | 7.9 |

| Private non-Jewish | 4.6 |

| English Catholic | 1.5 |

| French Catholic | 0.1 |

| Total | 100.0 |

| Local School Boards | Percent |

|---|---|

| Toronto District School Board | 39.0 |

| Ottawa-Carleton District School Board | 19.8 |

| York Region District School Board | 15.7 |

| Conseil des écoles publiques de l’Est de l’Ontario | 4.4 |

| Thames Valley District School Board | 3.0 |

| Durham District Schol Board | 2.0 |

| Hamilton -Wentworth District School Board | 1.8 |

| Waterloo Region District School Board | 1.8 |

| Peel District School Board | 1.7 |

| Conseil scholaire Viamonde | 1.5 |

| Ottawa Catholic School Board | 1.5 |

| Limestone District School Board | 1.3 |

| Simcoe County District School Board | 1.3 |

| Upper Grand District School Board | 1.3 |

| Greater Essex County District School Board | 0.7 |

| Toronto Catholic District School Board | 0.5 |

| Catholic District School Board of Eastern Ontario | 0.3 |

| Halton District School Board | 0.3 |

| Rainbow District School Board | 0.3 |

| Avon Maitland District School Board | 0.2 |

| Bluewater District School Board | 0.2 |

| Conseil scolaire catholique MonAvenir | 0.2 |

| District School Board of Niagara | 0.2 |

| Hamilton-Wentworth Catholic District School Board | 0.2 |

| Thunder Bay Catholic District School Board | 0.2 |

| Trillium Lakelands District School Board | 0.2 |

| Upper Canada District School Board | 0.2 |

| York Catholic District School Board | 0.2 |

| Total | 100.0 |

Respondents were asked to select the name of the school board in which their child was registered at the time of the reported antisemitic incident. Nearly 75% of 597 incidents for which respondents provided school board information took place in the Toronto District School Board (39%), the Ottawa-Carleton District School Board (20%), and the York Region District School Board, just north of the City of Toronto (16%). The remaining 25% of incidents were distributed among 25 of Ontario’s 88 school boards (Table 3). No reports were received from the remaining school boards, which cover areas where few Jews reside. This does not mean that no antisemitic incidents occurred there.

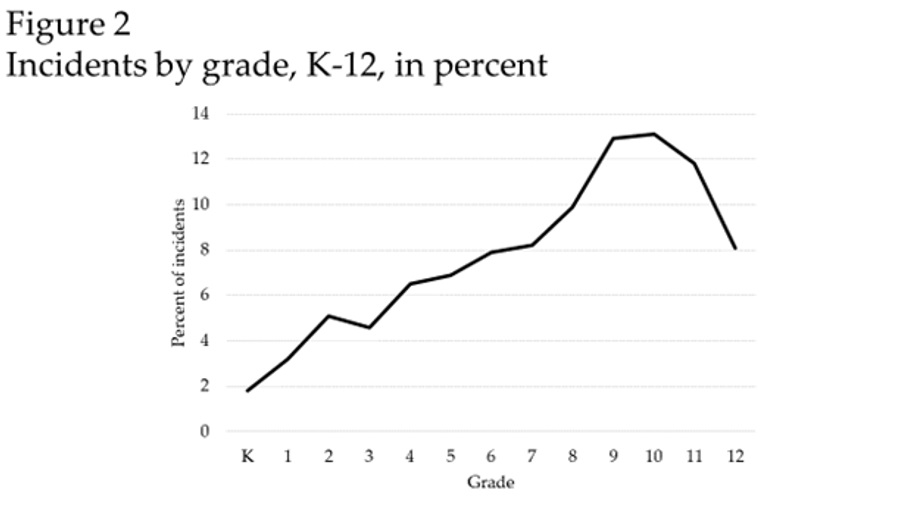

The percentage of reported incidents increased steadily from senior kindergarten to grade 10, eased in grade 11, then dropped markedly in grade 12 (Figure 2). The decline may be a result of the familiar student practices of (1) trying to stay out of trouble and focus on studying in an attempt to boost grades before applying to college or university, and/or (2) an increased resistance on the part of many older teens to communicate peer issues with their parents because of their underlying need for autonomy and desire for privacy.

Figure 2 Incidents by grade, K-12 – text version

| Grade | Percent of Incidents |

|---|---|

| K (Kindergarten) | 1.8 |

| 1 | 3.2 |

| 2 | 5.1 |

| 3 | 4.6 |

| 4 | 6.5 |

| 5 | 6.9 |

| 6 | 7.9 |

| 7 | 8.2 |

| 8 | 9.9 |

| 9 | 12.9 |

| 10 | 13.1 |

| 11 | 11.8 |

| 12 | 8.1 |

| Total | 100 |

2. What made the incidents antisemitic?

The survey asked parents: “In your opinion, what was it about the incident that made it antisemitic? Please select as many of the following options as apply.” Table 4 shows how the 942 closed-ended responses to this question were distributed among the six options provided by the questionnaire. (There are more responses than incidents because respondents could select multiple responses.) The question divides the six options into two groups: (1) expressions of negative attitudes toward Jews and (2) expressions of negative attitudes toward Israel.

| Question option | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Expressions of negative attitudes toward Jews | |

| The incident involved Holocaust denial, minimalization of the significance of the Holocaust, or saying that Jews use the Holocaust to legitimize their deplorable actions. | 9.2% |

| The incident involved assertions or excessive Jewish wealth, political power, or media control. | 7.4% |

| The incident involved blanket condemnation of Jews, statements like “Hitler should have finished the job,” “F*** you Jews,” “Jews are vermin,” and “Jews are cheap.” | 23.8% |

| Subtotal | 40.4% |

| Expressions of negative attitudes toward Israel | |

| The incident involved extreme negative statements about Israel – for example, that it has no right to exist as a Jewish state, that it is fundamentally a racist state, that it is committing genocide in Gaza, and that Zionism is equal to Nazism. | 29.6% |

| The incident involved a child being called a “baby killer,” told to “pick a side” in the Israel-Hamas war, or otherwise treated as if they are personally responsible for what is happening in the Gaza war. | 14.2% |

| The incident involved a teacher or a school-sanctioned activity expressing a point of view that made your child feel unwelcome or excluded because your child is Jewish. | 15.7% |

| Subtotal | 59.6% |

| Total | 100.0% |

One is immediately struck by the high percentage of responses that have nothing to do with Israel or the Israel-Hamas war. More than 40% of responses involve Holocaust denial, assertions of excessive Jewish wealth or power, or blanket condemnation of Jews—the kind of accusations and denunciations that began to be expunged from the Canadian vocabulary and mindset in the 1960s and were, one would have thought, nearly totally forgotten by the second decade of the 21st century.

Several times a day on multiple days in September 2024 a 13-year-old Jewish girl in Waterloo was surrounded by five boys repeatedly shouting “Sieg Heil!” and raising their hands in the Nazi salute. On each occasion she begged them to stop but they persisted. In October 2024, a six-year-old in Ottawa was informed by her teacher that she is only half human because one of her parents is Jewish.

Respondents considered nearly 60% of incidents antisemitic because of the extreme anti-Israel sentiments they expressed. Among the anti-Israel responses, more than 14% held Jewish school children personally responsible for aspects of the Israel-Hamas war, like the grade 9 boy in the York region north of the City of Toronto who, in September 2024, was accused by a classmate of being a “terrorist, rapist, and baby killer.”

Nearly 16% of reported incidents involved anti-Israel actions or activities supported or organized by teachers or school administrators. Some teachers wore shirts with a map of Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza that lacked boundaries between regions and was overlaid by the colours of the Palestinian flag or emblazoned with the slogan, “From the river to the sea,” thus graphically and aspirationally denying Israel’s existence. In 2024, one Ottawa teacher noticed a six-year-old Jewish girl wearing a necklace with a pendant in the shape of a map of Israel. She informed the child it is a map of Palestine. When a fellow Jewish student responded, “It’s Israel,” and explained it was a gift from their Hebrew school, the teacher said: “Your Hebrew school teachers are lying.” Still other teachers invited speakers to talk about the Israel-Palestine conflict from a radical Palestinian point of view while failing to invite counterparts to offer a more nuanced interpretation of the complex history of the conflict. Several school trustees sported keffiyehs at school board meetings where parents were expected to raise issues about the mistreatment of their Jewish children. The mother of a grade 12 student in Ottawa reported a November 2023 school assembly in which a speaker minimized the atrocities committed by Hamas on 7 October 2023.

“Only” about 30% of responses refer to extreme negative statements about Israel initiated by students. Some 315 “other” responses to this question were written in the words of the respondents themselves. Many “other” responses elaborated or repeated information already provided. However, nearly 26% of the “other” responses described glorifications of Hitler, Nazis, gas chambers, swastikas, and the Holocaust, while almost 14% involved bomb threats directed at Jewish private schools.

Zionism is the belief that the Jewish people have the right to self-determination in their ancestral homeland. In a 2024 poll of 588 Canadian Jewish adults and a January 2025 follow-up, 94% of respondents said they believe in the right of Israel to exist as a Jewish state. Only 1% said they were anti-Zionist. In Canada and elsewhere, the existence of Israel is central to Jewish identity. Zionism does not preclude the existence of a sovereign Palestinian state in the occupied territories. In fact, 61% of Canadian Jews with an opinion on the subject support a two-state solution to the Israel-Palestine conflict.Footnote 2 Yet most students who engage in hateful behaviour against their Jewish classmates seem to believe that Zionism is a force that must be destroyed. Moreover, many students evidently see all Jews as Zionists, all Zionists as Jews. Consequently, many Jewish students repeatedly hear they lack the right to live as individuals, as an ethno-religious group, and as a nation.

3. What happened during the incidents?

The survey asked parents: “What happened during the incident? Please select as many of the following options as apply.” Table 5 displays the distribution of the 959 occurrences that parents identified in closed-ended responses.Footnote 3 (Again, the number of responses is greater than the number of incidents because respondents could select multiple responses.)

The most frequent occurrence, at nearly 35% of the total, involved harassment in the form of threats, intimidation, expressions of hatred, incitement to violence, insults, pejorative “jokes,” and the like, delivered face to face, by phone or online. This category includes one gun threat that led to the aggressor being placed in jail for several days, suspended from school for ten days, and restricted from certain activities and relationships as his case worked its way to trial. In second place, at more than 17%, were teacher or school-sanctioned activities expressing a point of view that made Jewish children feel unwelcome because they are Jewish. And at just over 6%, assaults (hitting, pushing, spitting, throwing objects, touching aggressively, preventing movement) were the least frequent occurrences during an antisemitic incident. Acts of vandalism (nearly 15% of occurrences), aggressive hand gestures (more than 10%), abusive messages communicated on paper (almost 9%) and digitally (nearly 8%) round out the picture.

In short, the picture illustrates the way some Ontario school children treat their Jewish classmates and the manner and degree to which some teachers and school administrators in Ontario disrespect, exclude, and devalue Jewish children, not just by doing little to prevent, stop, and punish antisemitic actions, but also by initiating actions that make Jewish students feel unsafe and unwanted.

| Scenario | Percent |

|---|---|

| An assault took place (hitting, pushing, spitting, throwing objects, touching aggressively, preventing movement). | 6.2 |

| Vandalism occurred (malicious property damage, defacement, graffiti). | 14.9 |

| Spoken harassment was delivered face-to-face or by phone, Zoom, Teams, etc. (threat, intimidation, expression of hatred, incitement to violence, insults, pejorative “joking”) | 34.7 |

| Aggressive hand gestures were made (the Nazi salute, the middle finger, the inverted triangle, shooting, slitting the throat). | 10.3 |

| A teacher or a school-sanctioned activity expressed a point of view that made your child feel unwelcome or excluded because your child is Jewish. | 17.4 |

| Written abuse was distributed by letter, handbill, poster, sticker, etc. | 8.8 |

| Digital abuse authored by fellow students was delivered by email or social media posts. | 7.7 |

| Total | 100.0 |

4. Reactions of victims and schools

4.1 Victims’ reactions

The expression of anti-Jewish hate in schools is bound to affect Jewish children in myriad ways. To help discover these reactions, the survey asked respondents: “How did your child react to the incident? Please select all options that apply.” Table 6 categorizes 1,379 discrete responses to the closed-ended part of the question.

A relatively small percentage of children laughed off the incident (just over 3% of reactions), didn’t mention it to their parents (just over 5%), or decided to combat antisemitism in schools as a consequence of the incident (less than 7%). The most common emotional reactions to antisemitic incidents on the part of the victims involved anger (31%), fear of returning to school or of being bullied (nearly 27%), and worrying about losing non-Jewish friends and being socially isolated as a consequence (more than 27%).

Some 221 parents elected to add details in their own words in the open-ended part of the question. Based on their responses, it quickly became clear that, while many children reacted by feeling increased pride in their Jewishness, confronting their tormenters, and reporting the incident to school authorities, the great majority also experienced considerable emotional pain. The parents’ verbatim answers provide a long list of adjectives attesting to this outcome. They wrote that their children were sad, upset, anxious, depressed, fearful, confused, distraught, and terrified.Footnote 4 Some children lost trust in school authorities or hid their Jewish identity in school (or, in one case, literally hid during lunch hour). Others found it difficult to focus on their schoolwork or developed psychosomatic symptoms such as stomach pains and headaches. Still others insisted on staying home or switching schools.Footnote 5 Some cried.

The responses to this question tell us nothing about how long these emotional reactions will last. However, they do make one sociological consequence of antisemitic incidents evident. Many Jewish students banded together for comfort and safety, joined or increased their participation in Jewish organizations, and otherwise added substance to Jean-Paul Sartre’s observation that the antisemite helps to create the Jew.Footnote 6

| Child’s Reaction to the Incident | Percent |

|---|---|

| My child laughed off the incident. | 3.4 |

| My child didn’t mention the incident. | 5.4 |

| My child was angry about the incident. | 30.7 |

| Because of the incident, my child was afraid of being bullied/returning to school. | 26.5 |

| Because of the incident, my child was worried about losing/being socially isolated from non-Jewish friends. | 27.1 |

| Because of the incident, my child decided to combat antisemitism in school. | 6.8 |

| Total | 100.0 |

4.2 School reactions

More than 65% of respondents reported an antisemitic incident in their child’s school to school authorities. Nearly 35% did not. Non-reporting seems to have been mainly the result of two circumstances. Some children insisted that their parents not report the incident, fearing it would become public, and they would consequently become the target of increased harassment or bullying. As the parent of a Grade 11 Toronto student said: “My child doesn't trust school authorities because last time s/he reported an antisemitic ‘Heil Hitler,’ the school didn’t keep it discreet and s/he was bullied afterwards.” Alternatively, some parents believed that reporting the incident would fail to elicit meaningful action from the school, having heard or witnessed as much in the past.

Table 7 corroborates the last point. It categorizes 781 responses to the question: “What did your child’s school do about the incident? Please select all options that apply.” Again, multiple responses were permitted. In 49% of cases, school authorities did not investigate the reported incident. In an additional 8% of cases, their review of the incident led them to conclude—contrary to the assessment of parents and their children—that the incident was not antisemitic. In a small number of cases, school authorities recommended what amounts to the punishment of victims: in just over 1% of cases, school authorities suggested that the victim be removed from the school permanently or attend school virtually.

| School Response | Percent |

|---|---|

| School authorities did not investigate the incident. | 49.0 |

| School authorities said the incident was not a case of antisemitism. | 8.2 |

| School authorities recommended that my child be removed from the school permanently. | 0.2 |

| School authorities recommended that my child attend school virtually if he/she/they did not feel safe. | 1.0 |

| Subtotal | 58.5 |

| School authorities provided counselling for my child. | 4.2 |

| School authorities provided counselling for the perpetrator(s). | 3.8 |

| School authorities took punitive actions against the perpetrator(s) short of suspension. | 6.1 |

| School authorities suspended the perpetrator(s). | 4.7 |

| School authorities created or modified a program to promote ethnic, racial, and religious tolerance of Jews. | 2.8 |

| Incident was reported to police. | 5.3 |

| Subtotal | 26.9 |

| Miscellaneous otherTable 7 note * | 14.6 |

| Total | 100.0 |

Table 7 notes

- Table 7 note *

-

Note: The great majority of these cases repeated or elaborated information already provided.

In a minority of cases, schools responded by providing counselling for the targeted child (more than 4%) or the perpetrator(s) (nearly 4%), taking punitive action against the perpetrator(s) short of suspension (just over 6%), suspending the perpetrator(s) (nearly 5%), creating or modifying a program to promote ethnic, racial, and religious tolerance of Jews (fewer than 3%), or reporting the incident to police (more than 5%). Altogether, and even including additional positive responses in the “miscellaneous other” category, such responses amounted to well under one-third of the total. On the slightly brighter side, when school authorities responded, more than 60% did so within a week of the report (Table 8).

| School Response Time | Percent |

|---|---|

| The school began its response within one day. | 41.3 |

| The school began its response within one week. | 19.2 |

| The school began its response within one month. | 5.3 |

| The school began its response more than one month after the incident occurred. | 2.3 |

| The school has not taken action in response to the incident. | 32.0 |

| Total | 100.0 |

After their children endured antisemitic incidents, about one in eight parents who responded to this survey made the difficult decision to move their children to a different school. In some cases, this involved moving house.

Table 9 traces the mobility paths of the children who have switched or will soon be switching schools. More than 88% of them have left or are leaving English public schools, more than 8% have left or are leaving French public schools, and more than 3% have left or are leaving non-Jewish private schools. There are no recorded cases of children leaving Catholic or Jewish schools.

Jewish private schools are the number one choice for a new school. Nearly 39% of those leaving follow this route. The percentage would undoubtedly be higher if Jewish days schools existed in smaller communities, but in Ontario, only Toronto has a Jewish high school, and outside Toronto, Ottawa, Hamilton, and London, there are no Jewish primary day schools. This means that 9% of Ontario’s Jews lack access to a full-time Jewish school at any level and 19% lack access to a Jewish high school.

Another impediment to enrolment in a Jewish school is that the Ontario government does not fund Jewish schools, unlike the governments of Quebec, Manitoba, Alberta, and British Columbia (the only other provinces with substantial Jewish populations). The latter provinces offer partial tuition subsidies. Some of Ontario’s Jewish schools are subsidized by community philanthropists, but that still leaves many Jews who cannot afford to send their children to Jewish schools or live too far from Jewish schools to make enrolment practicable. Nevertheless, Jewish schools throughout Canada have experienced an enrolment boom since 7 October 2023.Footnote 7

| Previous Type of School | New School | Number of Students | Percent |

|---|---|---|---|

| English public school | English public school | 24 | 25.3 |

| French public school | 5 | 5.3 | |

| English Catholic school | 9 | 9.5 | |

| French Catholic school | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Non-Jewish private school | 8 | 8.4 | |

| Jewish private school | 37 | 38.9 | |

| Subtotal | 84 | 88.4 | |

| French public school | English public school | 3 | 3.2 |

| French public school | 1 | 1.1 | |

| French Catholic school | 4 | 4.2 | |

| Subtotal | 8 | 8.4 | |

| Private non-Jewish school | English public school | 2 | 2.1 |

| French public school | 1 | 1.1 | |

| Subtotal | 3 | 3.2 | |

| Total | 95 | 100.0 | |

5. Conclusion

School boards in Ontario significantly underestimate the number of Jewish students in their care and the frequency of antisemitic incidents in K-12 schools. The Toronto District School Board (TDSB) – which serves nearly one-third of Ontario’s Jewish school-age population – typifies these issues. In the 2023-24 school year, the TDSB’s Racism, Bias, and Hate Portal logged 2,155 incidents, of which 312 (14.5%) were categorized as antisemitic. Even this high number likely falls well short of the true total for three main reasons:

- A narrow definition of Jewish identity:

The TDSB defines antisemitism primarily as a form of religious hatred. However, Jews are not solely a religious group. According to the Canadian census and standard research practice, individuals who identify as Jewish by ethnicity, culture, or ancestry – even if they report no religious affiliation – are also considered Jewish. In the 2021 census, for example, 11% of Jews in the Toronto area identified as Jewish by ethnicity, culture, or ancestry and also identified with no religion. The TDSB does not count incidents involving such students, even if they are clearly motivated by antisemitism. As a result, many affected students are excluded from official tallies.Footnote 8

- Inconsistent application of the IHRA definition:

In 2018, the TDSB adopted the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism, which includes rhetoric and actions that deny Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state. Yet in practice, the Board frequently fails to categorize such incidents as antisemitic, even though this type of hostility is widespread in its schools.

- Underreporting due to fear:

Many Jewish students choose not to report incidents out of fear of being ostracized, re-victimized, or physically harmed. This climate of fear has led some students to hide their identities by removing visible symbols of their Jewishness – necklaces, pins, bracelets, or Hebrew writing on clothing. Self-censorship suppresses the visibility of the problem and contributes to the undercounting of incidents.

The consequences of widespread antisemitism for Jewish students and their parents are dire. In the public system, Jewish students are frequently ostracized, isolated, and assaulted verbally and physically. Jewish schools are targets of graffiti, vandalism, bomb threats, and shootings at school buildings. In more than 4 of 10 cases, antisemitic incidents are Nazi-inspired, expressing the hope that all Jews will soon be gassed and cremated, for example. In fewer than 6 of 10 cases, they deny Israel’s right to exist as a Jewish state, a key element of Jewish identity for most Jews.

Not all school boards are similarly affected by the spread of antisemitism. Antisemitic incidents are concentrated in the English public system, particularly in Ontario’s larger cities. But irrespective of variation in the frequency of antisemitic incidents, little is being done to resolve the crisis. In about 6 of 10 reported cases, schools do not investigate, deny that the incident involves antisemitism, or effectively punish victims by recommending that they take remote classes or switch schools.

School boards say that “schools should be safe and welcoming places where all students and staff feel respected, included, and valued in their learning and working environments.”Footnote 9 As the results of this survey demonstrate, the time has arrived to apply this principle to all students.

Appendix: Methodology

To recruit parents for the survey, a list of 257 Jewish organizations in Ontario and the email addresses of their heads was created. The list includes synagogues, summer camps, day schools, part-time schools, early childhood education programs, youth groups, and so on. In late January 2025, an email was sent to the heads of these organizations in which they were told that the survey would go live at the beginning of February. They were also asked to distribute a second email (provided by the researcher) a few days later to all members of their organizations. The second email contained information about the survey and explained how parents with children in the province’s K-12 schools could answer the survey questionnaire online. Follow-up emails and phone calls encouraged responses from various Jewish institutions and communities. Ads about the survey were placed in the Canadian Jewish News, the main source of news about Canada’s Jewish community.

The survey, available online in English and French until early April 2025, elicited 599 reports on 781 antisemitic incidents.Footnote 10 These 781 incidents took place between October 2023 and January 2025 inclusive and are estimated to have been directly experienced by at least 10% of Ontario’s roughly 30,000 Jewish school-age children. The incident reports form the quantitative basis for this study. In addition, 14 respondents participated in approximately 35-minute semi-structured interviews.

It became evident in the course of the research that, despite assurances to the contrary, some parents worry that information they supply might be traceable back to them, with unknown consequences for their privacy and safety—and the privacy and safety of their children. It also emerged that many children are reluctant to tell their parents about antisemitic incidents they experience. They believe their parents will go to school authorities, some of whom will take action against the aggressor. The incident is then likely to become common knowledge in the student population and lead to ostracism, harassment, or physical assault. In short, the high level of anxiety in Ontario’s Jewish communityFootnote 11 depressed the total number of incident reports available for this survey.

The survey is based on a non-probability sample of Jewish adults in Ontario that roughly reflects the characteristics of the approximately two-thirds of Ontario’s Jewish adults who are relatively well connected to the province’s Jewish community insofar as they are members of a synagogue or other Jewish organization.

To illustrate how the sample compares to Ontario’s Jewish population as a whole, two important features of the sample and the population may be highlighted: area of residence and connection to organized Jewish life. In one instance, Toronto data are used as a proxy for all of Ontario, which is less problematic than it may seem since 81.4% of Ontario’s Jews live in the Toronto census metropolitan area according to the 2021 Census of Canada.

Table A1 shows where Ontario’s Jews and survey respondents reside. It divides both groups into the province’s 11 census metropolitan areas with more than 1,000 Jews each and an “other” category for the rest of the province.

The biggest difference between the sample and the population concerns the percentage of respondents from Toronto and Ottawa, by far the two largest Jewish centres in Ontario. The Toronto sample is about 18 percentage points smaller than the corresponding figure for the population, while the Ottawa sample is about 15 percentage points larger. These results may be attributed to the survey’s relatively more effective advertising campaign in Ottawa and possibly the greater frequency of antisemitic incidents in Ottawa relative to the size of its Jewish population. This difference notwithstanding, the social composition of Jews in Toronto and Ottawa does not appear to be very different. For example, the Jewish communities in the two cities had the identical median age in 2021, 42.4 years.Footnote 12 And the denominational breakdown of Jews is not greatly dissimilar in the two cities, the main difference being the higher percentage of Reform Jews in Toronto and of non-denominational Jews in Ottawa (Table A2). The latter differences may balance out insofar as Reform and nondenominational Jews are the least traditional Jews in Canada.

| Census metropolitan area | Jewish Population | Percent of Jewish population | Percent of sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Toronto | 186,905 | 81.4 | 60.8 |

| OttawaTable A1 note * | 14,045 | 6.1 | 20.9 |

| Hamilton | 5,310 | 2.3 | 1.5 |

| London | 2,765 | 1.2 | 2.6 |

| Barrie | 2,275 | 1.0 | 0.9 |

| Kitchener-Cambridge-Waterloo | 2,245 | 1.0 | 1.5 |

| St. Catharines-Niagara | 1,710 | 0.7 | 0 |

| Oshawa | 1,645 | 0.7 | 0.6 |

| Kingston | 1,410 | 0.6 | 1.2 |

| Windsor | 1,270 | 0.6 | 0.5 |

| Guelph | 1,210 | 0.5 | 0.9 |

| OtherTable A1 note ** | 5,950 | 3.9 | 8.6 |

| Total | 229,485 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

Table A1 notes

- Table A1 note *

-

The Ontario part of the Ottawa-Gatineau census metropolitan area.

- Table A1 note **

-

Includes areas outside census metropolitan areas.

Second, as might be expected given this study’s methodology, the sample consists of individuals who are more connected to organized Jewish life than are Jews in Ontario’s population. Thus, according to the 2018 Survey of Jews in Canada, 70% of Toronto’s Jewish households have at least one member who belongs to a synagogue or a Jewish organization other than a synagogueFootnote 13. The comparable percentage is undoubtedly lower in other Ontario citiesFootnote 14. For this study’s sample, the corresponding figure is 99%. Similarly, according to the 2021 census, nearly 86% of Ontario’s Jews said they identify with the Jewish religionFootnote 15. The corresponding figure for this study’s sample is more than 97%.

In sum, while the sample cannot be considered representative of Ontario’s Jewish population, available data suggest that it is not hugely different from the roughly two-thirds of Ontario’s Jews who are relatively well connected to the community by membership in synagogues and other Jewish organizations.

| Denomination | Toronto 2018 | Ontario Sample | Toronto Sample | Ottawa Sample |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OrthodoxTable A2 note * | 17 | 10 | 10 | 15 |

| Conservative | 27 | 38 | 38 | 34 |

| Reform | 17 | 18 | 20 | 10 |

| Other denominationTable A2 note ** | 13 | 4 | 5 | 3 |

| No denomination | 26 | 29 | 28 | 38 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

Source for Column 1: Robert Brym, Keith Neuman, and Rhonda Lenton, 2018 Survey….

Table A2 notes

- Table A2 note *

-

Includes Orthodox, Modern Orthodox, Hasidic, Yeshivish, and Chabad.

- Table A2 note **

-

Includes Reconstructionist, Humanist, Humanitarian, Renewal, and other.

About the Author

Robert Brym is S.D. Clark Professor of Sociology Emeritus, University of Toronto, and a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada. He has published more than 200 scholarly works and received multiple awards for his publications and teaching, including the Northrop Frye Award (University of Toronto), the British Journal of Sociology Prize (London School of Economics), the Outstanding Contribution Award of the Canadian Sociological Association, and the Louis Rosenberg Canadian Jewish Studies Distinguished Service Award. His main research projects have focused on the politics of intellectuals, Jewish emigration from the Soviet Union and its successor states, the second intifada, and Jews in Canada. For downloads of his published work, visit University of Toronto - Academia - Recently Published by Robert Brym.