Examination of the "follow-the-money" approach to copyright piracy reduction

Final report

Prepared by Circum Network Inc. for Canadian Heritage

April 14, 2016

This is an independent expert report produced by Circum Network as commissioned by the Department of Canadian Heritage. The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Circum, 2016

CH44-160/2016E-PDF

978-0-660-06008-8

Table of contents

List of acronyms and abbreviations

- BPI

- British Recorded Music Industry

- BRAM

- Business Risk Assessment and Mitigation initiative

- CSCI

- Commercial Scale Copyright Infringement

- DAAP

- Digital Assurance Advertising Providers

- DAAP

- Digital Assurance Advertising Providers

- DDL

- Direct Download Host

- DMCA

- Digital Millennium Copyright Act

- FACT

- Federation Against Copyright Theft

- IFPI

- International Federation of the Phonographic Industry

- IFPI

- the International Federation of Phonographic Industries

- IPA

- the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising

- ISP

- Internet Service Providers

- IWL

- Infringing Website List

- OHIM

- Office of Harmonization in the Internal Market

- P2P

- Peer to peer

- PA

- the Publisher's Association

- PIPCU

- City of London Police's Police Intellectual Property Crime Unit

- TAG

- Trustworthy Accountability Group

- TCRP

- Trusted Copyright Removal Program for Web Search

Executive summary

This report presents one type of counter-measure to commercial-scale copyright infringement (CSCI) activity. It focuses on the type of copyright infringement defined in the Copyright Act as "provid[ing] a service primarily for the purpose of enabling acts of copyright infringement" where "the economic viability of the provision of the service if it were not used to enable acts of copyright infringement" would be such that it would not be a viable economic enterprise. Furthermore, the report focuses on one type of counter-measure, known as "Follow the money".

Follow-the-money counter-measures aim to reduce or to interrupt the flow of revenue to CSCI sites. They involve three economic sectors:

- Advertising, because CSCI sites draw significant revenues from ads placed on their pages;

- Payment solutions that process online transactions required for membership or premium service payments on some CSCI sites; and

- Search engines that can facilitate access to unlawful content by including hosting sites in search results.

The online advertising sector is characterised by a disconnect between the ad buyer and the ad space provider: to a large and increasing degree, online ad placement is automated and based on algorithms that aim to match the target profile with the visitors of various websites. In addition to giving rise to a variety of fraudulent practices, this has increased the risks to household brands to be associated with online activity that they would prefer to stay away from. Therefore, the online advertising sector has a vested interest in combatting the placement of legitimate ads on CSCI sites and it has initiated a number of actions to do so. These actions have had some impact already but their effectiveness depends upon the adoption of some standards and techniques (which carry a cost) and they will not deter those brands that in fact have a business incentive to advertise on CSCI sites.

Payment solution providers have been less proactive at combatting the use of their services on CSCI sites. Major companies tend to refer to their terms of service when this issue is raised and to indicate that they diligently (if slowly) apply them upon receipt of complaints. Payment solutions are a distant second to advertisement in the sources of revenues of CSCI sites.

Search engines have been sensitized to the problem of referencing CSCI sites in search results. While they are willing to be part of a global solution, they minimize their importance in the CSCI ecosystem and they do not want to be tasked with policing the Web. Google has implemented its Transparency Report and processes requests for URL (not site) blocking based on the reports produced by rights holders.

Canadian rights holders adopt one of two positions. Larger firms and sectors where rights are more concentrated support the actions taken by their global partners and contribute as they can. Smaller rights holders and firms in sectors where rights are diffused identify CSCI sites as a problem and may support global partners' efforts in spirit, but do not spend their limited national resources targeting elusive pirates.

Follow-the-money counter-measures raise the issue of the identification of CSCI sites. At this point, this task has been left with rights holders to a very large degree, with few examples of government involvement.

Overall, it is concluded that Follow-the-money approaches (or the disruption of visibility, payment services and advertising revenue) can be effective but do not have the potential to eradicate CSCI websites on their own. They have a role to play in a wider global strategy. This conclusion is backed by the observation that copyright piracy is an international problem that requires cross-border cooperation and solutions, particularly with respect to defining CSCI activity and identifying perpetrators.

While it is relatively easy to identify infringing URLs, it is much more difficult to make a case for a whole website to be considered commercially infringing. This may be an area where government could get involved in support of rights holders. French authors have studied this question in some depth. Our own research suggests that Canada's legal framework should be reviewed in comparison with international standards for defining CSCI and facilitating Follow-the-money counter-measures. Canada should also consider how its law enforcement agencies can best support Follow-the-money counter-measures; the example of the United Kingdom may be a starting point in this regard.

Canadian payment providers could be encouraged to enforce their terms of service more aggressively, ideally working in closer partnership with rights holders as found in the United States.

At another level, government could increase efforts to educate the public regarding the well-documented personal and societal risks and costs of using CSCI websites. Such efforts appear to be having a positive impact elsewhere.

The role of website hosting services and Internet service providers and legislation governing them could also be investigated as these services can ultimately stymy efforts to follow money to its ultimate destination by protecting the identity of CSCI operators.

Introduction

This report deals with commercial-scale copyright infringement (CSCI) activity. It focuses on the type of copyright infringement defined in the Copyright Act as "provid[ing] a service primarily for the purpose of enabling acts of copyright infringement"Footnote 1 where "the economic viability of the provision of the service if it were not used to enable acts of copyright infringement" would be such that it would not be a viable economic enterprise.

Practically speaking, sources suggest that there are four types of CSCI sites (Digital Citizens Alliance, 2014, 5-6; also OHIM, 2016, 8-9); other sources may classify them differently:Footnote 2

- "BitTorrent and other P2P portals: BitTorrent is the most popular peer-to-peer (P2P) file distribution system worldwide […] These portals let users browse or search for files available on peer-to-peer distribution systems. Users following the links can access media files stored on multiple computers across the P2P network and download the content to their own computers for use at no charge."

- "Linking sites: These portals aggregate and index links to media content hosted on Direct Download (DDL) Hosts (described below) or other sites. Some allow search within the Linking Site itself to facilitate access to content. They do not host content themselves. Users browse or search for the content they want, all the while exposed to ads. The users then click a link and download the content from the site where it is hosted, at no charge." (also Imbert-Quaretta, 2013, 4)

- "Video streaming host sites: […] sites [that have] embedded players that allow users to stream videos hosted elsewhere. The remaining sites both stream and host content, offering subscriptions to users who want to store video content and then allow users to stream videos."

- "Direct download (DDL) host sites: [they] allow users to upload media files to cloud-based storage. Users can generate links to be used by themselves or others to download the content for free. […] DDL Hosts are fundamental to the content theft ecosystem, providing the content to which Linking Sites point."

In this report, we describe the ecosystem of CSCI first but without going into details related to the size of the CSCI market or to the various dangers associated with their use (e.g., Motion Picture Association – Canada, no date; Sivan, Smith, and Telang, 2014; INCOPRO, 2015; Ma, Montgomery, and Smith, 2016). Then, we identify the panoply of possible counter-measures to this type of copyright infringement. Finally, we focus on one type of counter-measure, known as "Follow the money", describing such measures and assessing their effectiveness.

Methodology

This report presents the results of a document review and of a series of interviews.

Documentation on Follow-the-money approaches has grown significantly over the past three years. Documents that were used in this report are listed at the end of the report. They were identified as follows:

- The Canadian Heritage project authority provided the study team with an initial list of references.

- The study team conducted an on-line search for additional documentation that was empirical, not advocacy-related.

- Additional documentation was identified in the analysis of the initial documents.

- Key informants offered additional documents or pointers to relevant additional documentation.

Key informant interviews were conducted with representatives of the following Canadian sectors: advertising, payment solutions, search engines, and rights holders. The list of informants was established as follows:

- The Canadian Heritage project authority provided the study team with an initial list of possible key informants.

- Some knowledgeable informants were referred by interviewees who know their sector well.

- The study team added names to the list on the basis of team members' knowledge of the various sectors.

Documentation was relatively easy to locate. However, the study team had some difficulty accessing representatives in every sector of interest: contact was initiated through e-mail, backed by a letter of introduction signed by the Director, Copyright and International Trade Policy at Canadian Heritage, and up to two follow-up calls were made. While fewer interviews than expected were completed, interviews were secured in each sector with at least one significant player. In total, 14 interviews were completed.

Ecosystem of commercial-scale copyright infringement

Some individuals consume artistic works (e.g., music, films, books) via the Internet without permission of the copyright owners. This report describes those websites that make a business out of providing artistic works without compensation to the rights owners.

To give a sense of volume, the International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) (2015, 38) reported that:

Based on data from comScore and Nielsen, IFPI estimates that 20 percent of fixed-line internet users worldwide regularly access services offering copyright infringing music. Digital piracy is constantly evolving and takes many forms including distribution of unauthorised music through platforms such as Tumblr and Twitter, unlicensed cyberlockers, BitTorrent file-sharing and stream ripping. IFPI estimates that in 2014 there were four billion music downloads via BitTorrent alone, the vast majority of which are infringing, and this does not take into account other channels such as cyberlockers, linking sites and social networks.

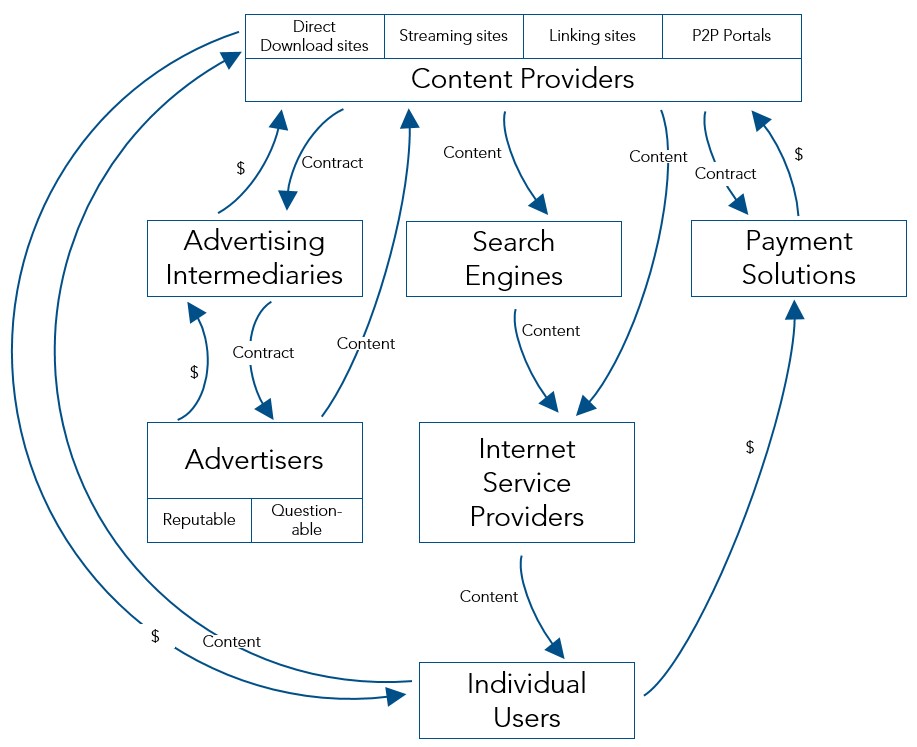

The downstream flow of works starts with content providers (here, CSCI sites) and ends with individual users; between these two ends are the necessary Internet Service Providers (ISPs) (BOP Consulting, 2015, 15) and, in some cases of access, search engines (Imbert-Quaretta, 2013, 23). To enable this relationship and to financially motivate content providers, two more actors are required: advertisers and payment solution providers (Digital Citizens Alliance, no date, i; Imbert-Quaretta, 2014, 5; Imbert-Quaretta, 2013, 4 and 22; Weatherley, 2014c, 1; BAE Systems Detica, 2012).

Deriving illegal revenue streams from infringing material is also likely to involve, or require the cooperation of one or more of the following actors:Footnote 3

- Search engines (principally Google): can facilitate access to unlawful content by including sites that host or facilitate access to content that infringes copyright in search results;

- Advertisers: some brands and advertisers pay money to advertise with online providers that enable access to content that infringes copyright. These advertisers are therefore – often inadvertently - helping some online providers to make money out of illegal content; and

- Financial intermediaries: companies such as PayPal and credit card companies process online transactions, some of which relate to various types of payment for content that infringes copyright.

Figure 1 – Key exchanges in the CSCI ecosystem

Figure 1, depicts the flows of copyrighted works between CSCI websites and individual users. It shows the process of how CSCI make business out of providing artistic works without compensation to copyright holders. There are four examples of CSCI: direct download websites, streaming websites, linking websites and peer-to-peer portals. The websites have two main types of relationships: receiving money and providing content. They receive money from advertising intermediaries and payment solutions, and they receive content from advertisers and individual users. Infringing websites in turn provide content to search engines, internet service providers and individual users. For their part, payment solutions receive money directly from individual users, while advertising intermediaries receive money from reputable and questionable advertisers.

Advertising

Internet advertising in general is a complex system. It is no different as applied to the CSCI sites:

Whilst advertisers recognise that the appearance of their branding on illegal sites can be damaging for their reputation, many brands do not know, or cannot determine, exactly where their advertising is being placed. There are often several intermediaries between the brand and the websites on which their advert appears. Those intermediaries may include all or some of the following: media agencies, trading desks, demand side platforms, ad auction systems, supply side platforms and ad networks. The majority of these intermediaries are designed to, and indeed are paid to, target audiences as efficiently and as cost-effectively as possible.

S'agissant du secteur de la publicité en ligne, celui-ci est complexe et fait intervenir une série d'acteurs intermédiaires. Il existe deux systèmes de placement de la publicité sur internet. Le premier ressemble à ce qui existe dans le monde physique et se caractérise par le choix fait par l'annonceur de diffuser sa publicité sur tel ou tel site. Un nouveau système, dit à la performance, prend une place grandissante sur internet. L'annonceur n'achète plus un espace précis mais la diffusion d'un message auprès d'un public ciblé. Ce système se caractérise par le fait que l'annonceur ne sait pas à l'avance où sa publicité sera diffusée, par la multiplicité des acteurs qui y participent et par la mise en œuvre de procédés automatisés, notamment en temps réel.

This second type of Internet ad placement represents the majority of expenditures already:

An estimated 53% of US online display ad placement was automated in 2013, according to Magna Global, which projects that volume to increase to 83% by 2017. As buying and selling ads programmatically continues to grow, the opportunity to manipulate technology for further advertising gain only increases.

Such advertising occurs within a highly-complex online advertising ecosystem involving many different actors and stakeholders, including advertisers, advertising agencies, ad networks, ad exchanges, ad trading platforms, and the web sites and other media properties on which the advertisements are placed. Ad networks and ad exchanges use advanced computer algorithms to place advertisements on different sites. The placement is often fully automated, pairing an advertisement with available inventory. This automated placement efficiently places an advertisement in front of the appropriate target audience.

This problem is exacerbated by the increased use of "Programmatic" transactions: targeted ad campaigns deployed according to software rules and enriched by data. Programmatic advertising is facilitated by advertising exchanges, where website advertising space is bought and sold via electronic transactions in real-time and otherwise. Programmatic transacting brings efficiency and increased automation to online advertising and is the future of digital media trading, with a strong annual growth rate of 27%.

Major intermediaries include Google AdSense, Yahoo! Publisher Network, DrivePM (Microsoft), TradeDoubler, Zanox, AdLink, Interactive Media, AOL, and SponsorBoost. There is also a market for real time trading of ads such as Rightmedia (Yahoo!), AdECN (Microsoft), Tomorrow Focus (Commission, 2008) or Advertising.com. (Manara, 2012, 18)

This trend has had the effect of diversifying the advertisers on CSCI sites:

Of course, these days, with the help of established ad networks such as Doubleclick and Adsense, pirate sites are not only displaying ads for gambling and dating companies, but also ads for multinationals, including McDonald's, Hyatt Hotels, Netflix and Ticketmaster.

Advertising is the predominant revenue source for the top 250 unauthorised sites and is the most important issue to tackle to have an impact on the revenue generated by the top 250 unauthorised sites in Europe

OHIM (2016, 10) estimates that "Mainstream advertising alone made up 46% of all ads collected in [its] study" of CSCI sites.Footnote 4

There are a number of approaches to the selection of ads on a website (Manara, 2012, 17): from contextual ads, which are adapted to the content of the website page, to affiliation banners, retargeting (ads for products and services of prior interest to the user), and domain name parking, which associates ads with the domain name. Price plays a role as well; prices for online ads are determined by auction, in a constant state of flux, changing within milliseconds.

CSCI sites benefit greatly and in at least two ways from this advertising ecosystem: they bring in revenues and they acquire credibility.

Many websites that sell or provide access to pirated content profit from advertisers paying for banner ads. They also may appear legitimate to consumers because the advertisements are from reputable businesses.

From some accounts, advertising brings hundreds of millions of dollars to the CSCI industry:

The web sites MediaLink examined accounted for an estimated $227 million in annual ad revenue, which is a huge figure, but nowhere close to the harm done to the creative economy and creative workers. The 30 largest sites studied that are supported only by ads average $4.4 million annually, with the largest BitTorrent portal sites topping $6 million. Even small sites can make more than $100,000 a year from advertising. Because their business model relies entirely on illicitly distributing millions of stolen copies of highly valuable works that cost others billions to create, their profit margins range from 80% to 94% […].

According to IFPI (2015, 40), "Major brands are continuing to advertise on pirate sites. In the month leading up to publication of this report, IFPI identified egregious pirate sites including Atrilli.net, Albumjams.com, 4Shared.com, Sharebeast. com and SUMOTorrent.sx featuring advertising for AirAsia, Barclays Bank, British Airways, eBay, Expedia, Lloyds Banking Group, Microsoft, PayPal, Royal Bank of Canada, Royal Caribbean, Samsung, Santander, Telefónica UK Limited, Unilever, Vodafone and Western Union Holding Inc. The adverts were viewed from various countries including Australia, Canada, Brazil, United Kingdom and the United States – in each case appearing next to copyright infringing music or download pages." The same message comes out of an OHIM study (2016, 10).

An important distinction must be made between legitimate or reputable brands and questionable brands. The former encompasses household names that would likely not want to be associated with illicit activities such as the ones conducted by CSCI sites – "In many cases major brands inadvertently advertise on suspected IP infringing websites, lending these websites credibility, possibly funding infringement and risking brand damage. Often this is due to a lack of understanding as to which websites pose an IP infringement risk." (OHIM, 2016, 5) The latter refers to gambling and pornography sites and the like, which may not care much which company they keep. Informants indicated that "sketchier advertisers are a much smaller pool and they use sketchier intermediaries."

One would expect there to be an inherent motivation for reputable brands to stay away from CSCI sites but possibly the opposite from questionable brands. In reality, both types of advertisements are currently found on CSCI sites.

Premium brand ads appeared on nearly 30% of large sites, highlighting the ineffectiveness of current approaches to protecting the brands' reputation and value. Premium brands are those easily recognizable companies familiar to most consumers, and which suffer reputational damage when their ads appear on content theft site (sic), often alongside ads for illicit sites and services. [...] In addition to those blue-chip companies, legitimate 'secondary' brands also can find their ads served into content theft sites through the complex and increasingly computer-driven ecosystem of ad networks and exchanges.

[...] other [secondary] brands may offer illicit websites, money scams or malware to end users, and these brands are some of the most prominent advertisers on pirate websites. This is because they are unlikely to suffer any real impact to their reputation by appearing on such sites. This strand of revenue is a particularly challenging one for the industry and government to address because it requires a change in mind-set from these types of advertisers and, perhaps, a certain level of enforcement power to influence behaviour.

The continued presence of advertisement on CSCI sites by reputable brands has been explained in two ways: either brands are incapable of controlling where their online advertisement is placed or they are attracted by the revenues brought about by this promotion. A later section in this report will discuss the measures available to counter advertising on CSCI sites as well as their apparent effectiveness.

Major online ad companies and brands continue to support access to illegally pirated content by buying, selling and delivering advertising to sites that direct users to torrents of illegal content. Visit the top torrent search engines, and you'll find ad calls from Yahoo, Google, Turn, Zedo, RocketFuel, AdRoll, CPX Interactive and others. [...] ad companies are attracted by the revenue torrent sites can generate for them. […] Ask an ad tech vendor whose code is clearly on a piracy site about it, and fingers start pointing in every direction except back at them. The ad tech system appears to have created enough complexity with its daisy chains of daisy chains that there's plausible deniability for all.

Referring to clients using its ad placement services, Google indicated that their terms of service are global (but essentially bound by United States law), and that most cases of infringing terms of service are caught at the pre-screening stage and, therefore, don't require legal action.

Payment solutions

The ecosystem of payment solutions is much simpler. Where a CSCI site offers paid subscriptions (typically for premium services) or payment to uploaders for providing popular files, they must use a payment intermediary such as a credit card (such as VISA or MasterCard) or a currency exchange site (such as Paypal).

The main distinction between these credit card companies and Paypal is that credit card transactions take place between two banks who have the purchaser and the seller as clients whereas a currency exchange takes place directly between the purchaser and the seller. (Imbert-Quaretta, 2014, 6)

MasterCard representatives explained that "Merchant status is solicited and enabled through MasterCard's acquiring bank partners under the full range of acquiring obligations per MasterCard's licensing agreement. Acquirers may enable merchants directly or may do so via third parties, in either case the full range of MasterCard obligations must be satisfied. MasterCard has an extensive acquirer onboarding process. All prospective acquirers need to meet certain qualifications such as data security standards and fraud management to be able to conduct acquiring activities for MasterCard."Footnote 5

Availability of payment solutions on CSCI sites is a common occurrence:

Every cyberlocker that offered paid premium accounts to users provided the ability to pay for those subscriptions by Visa or MasterCard, with only one exception. Only a single cyberlocker accepted PayPal. […] Cyberlockers are online services that are intentionally architected to support the massive distribution of files among strangers on a worldwide and unrestricted scale, while carefully limiting their own knowledge of which files are being distributed.

Websites that profit from infringing material typically rely on payment processors to process their sales. Use of well-known payment processors provides such websites with an appearance of legitimacy, and consumers may be misled into thinking the site is lawful.

This study also demonstrates that more could be done by leading payment providers, as they are still featuring as payment providers for sites in the top 250 unauthorised sites in each of the following key countries in Europe; France, Germany, Italy, Spain and the UK.

Nonetheless, MasterCard maintains that it "does not knowingly permit use of our acceptance marks for display on these sites and MasterCard acts immediately to have the marks removed once we become aware of such instances. MasterCard's Business Risk Assessment and Mitigation initiative (BRAM) is designed to protect MasterCard and its customers from illegal and brand damaging transactions, which may pose significant fraud, regulatory or legal risk, or may cause reputational damage. The purpose of the program is to identify merchants who introduce more than an acceptable level of risk into the payments system."Footnote 6

Although not used as frequently as credit cards and Paypal, there are other payment solutions that have grabbed a small portion of the payment market. They don't appear to be significant players yet.

Parallèlement à PayPal, on trouve des intermédiaires qui proposent des paiements par virement entre les comptes bancaires des personnes acceptant de recourir à ce moyen. C'est le cas du système allemand Giropay [...] Certains de ces prestataires (tel Neteller) émettent aussi de la monnaie électronique [...] Des systèmes de portefeuille virtuels se sont développés, pouvant consister en la conservation des coordonnées de cartes bancaires d'un client identifié permettant la génération d'un ordre de paiement par simple volonté en ce sens (appstore d'Apple, Amazon Checkout, Facebook Credits, par exemple), ou en une application de téléphone mobile permettant le paiement en lien avec une carte de crédit ou un compte alimenté par voie bancaire (Google Wallet, par exemple).

While major credit card companies as well as Paypal have pledged not to support illicit transactions, some claim that payment solutions are available on sites requiring them.

Both Visa and MasterCard have clearly stated in the past that sites that profit from infringement should not be able to use the company's financial processing systems. Yet the research conducted for this report found that despite these statements, both Visa and MasterCard are widely offered through the cyberlocker universe: Visa and MasterCard were offered as payment options on twenty-nine of thirty sites. [...] PayPal was offered as payment option on only one site (Mega).

CSCI sites have alternatives to using credit cards and Paypal. Third party processors, virtual wallets, and resellers are available.

Payment processors such as Liqpay handle the transaction on behalf of the site rather than the site operator having to implement the payment programmatically, and this method was available on 12 out of the 30 tested sites. A suspended merchant account was observed during this type of transaction, indicating that there are also steps that can be taken to prevent payment processing. Another type of transaction observed was that carried out via virtual wallets, including services such as Google Wallet, RoboKassa and PayPal (the top three most observed) also an option available on about a third of the sample of websites. These services allow users to add funds to a virtual wallet, which stores the value and can then make a payment to someone else's wallet. […] Resellers make a business out of selling access to the hosting sites that are key to infringement of copyright.

Search engines

Search engines, primarily Google, are part of the ecosystem in that they are used to locate infringing material on the web. In the case of Google, its Autocomplete feature is also identified by some rights holder associations as problematic.

There is some controversy as to the importance of search engines in the CSCI dynamic. On the one hand, Google claims that a relatively small portion of traffic to infringing sites is from search engines, but other sources suggest that search engines are a major contributor to traffic.

Search is not a major driver of traffic to pirate sites. Google Search is not how music, movie, and TV fans intent on pirating media find pirate sites. All traffic from major search engines (Yahoo, Bing, and Google combined) accounts for less than 16% of traffic to sites like The Pirate Bay. In fact, several notorious sites have said publicly that they don't need search engines, as their users find them through social networks, word of mouth, and other mechanisms. Research that Google co-sponsored with PRS for Music in the UK further confirmed that traffic from search engines is not what keeps these sites in business. These findings were confirmed in a recent research paper published by the Computer & Communications Industry Association.

According to surveys, a significant amount of Internet traffic to websites is driven by the first page of search results, and the top results provided by large search engines often include many sites offering unauthorized copyrighted content.

[…] whilst search engines do not cause piracy, they have some secondary role in its facilitation. Google asserts that it is not a major driver of traffic to pirate sites and traffic from the major search engines (Yahoo, Bing, Google) accounts for just 13% of traffic to unlicensed music sites. However, other research, such as that by the MPAA, has shown that 65% of 'pirates' regularly use search engines to identify unlicensed content.

IFPI (2015, 39) offers evidence to the effect that search engine results play a role in on-line piracy:

Search engines are a significant driver of traffic to unlicensed websites, and play a major role in influencing the decisions of internet users about where and how to obtain content. A study entitled "Do Search Engines Influence Media Piracy?" published in 2014 by Carnegie Mellon University in the US revealed that 94 per cent of internet users presented with search results that mostly linked to licensed services purchased a film, while only 57 per cent did so when presented with results that mostly linked to infringing services. The researchers concluded: ‘our results suggest that reducing the prominence of pirated links can be a viable policy option in the fight against intellectual property theft'.

Millward Brown Digital (no date) reported telling results from an original study:

Overall, search engines influenced 20% of the sessions in which consumers accessed infringing TV or film content online between 2010 and 2012. Search is an important resource for consumers when they seek new content online, especially for the first time. 74% of consumers surveyed cited using a search engine as either a discovery or navigational tool in their initial viewing sessions on domains with infringing content. Consumers who view infringing TV or film content for the first time online are more than twice as likely to use a search engine in their navigation path as repeat visitors.

Autocomplete is a feature of Google Search which provides suggestions for words the user could add to complete the query. It uses information from queries performed by other users. (Google, 2014, 20) This feature has been criticized as a facilitator of illicit downloading and of identification of CSCI sites because it can offer terms that direct users in these directions.

[...] Google now excludes certain queries related to copyright infringement from its Autocomplete function, which uses algorithms to suggest complete search terms as soon as a user starts typing. This policy has resulted in the exclusion of notorious infringing services like The Pirate Bay from Autocomplete results.

Autocomplete is an ongoing problem. As pictured below, consumers searching for the recent UK best-selling artists 'Nico & Vinz' do not have to go far before being offered their single 'Am I Wrong' in MP3 format. Clicking on this option leads to a page which features infringing versions as the top results. Google's autocomplete means that consumers are inadvertently being led to infringing content with very few key strokes and clicks.

Counter-measures

Measures to counter online copyright infringement are numerous but unequally effective and unevenly socially acceptable. This section introduces a brief typology of counter-measures as well as a key issue in implementing counter-measures: the identification of CSCI sites.

Typology of counter-measures

Counter-measures can be classified as addressing the demand side or the supply side of the infringing online consumption of copyright works. The demand side refers to the individual user, who can be threatened with legal action or informed of alternative ways of accessing the artistic works they are looking for. The supply side comprises the various CSCI sites that offer artistic works without compensation to the rights holders. The range of counter-measures is much larger in this case. (BOP Consulting, 2015)

Table 1 summarises possible counter-measures by classifying them as pertaining to the demand or the supply side and by distinguishing ‘carrot' and ‘stick' approaches.

| Types of counter-measures | Carrots | Sticks |

|---|---|---|

| Demand side |

|

|

| Supply side |

|

|

Sources: BOP Consulting, 2015; Imbert-Quaretta, 2013; Imbert-Quaretta, 2014; Lescure, 2013; Manara, 2012; United States Department of Commerce Internet Policy Task Force, 2013; United States Trade Representative, 2015; Weatherley, 2014a; Weatherley, 2014c; IAB, 2015

Identification of CSCI sites

To be effective, many counter-measures require the identification of CSCI sites. This task has not proven easy. "There are more than 60 trillion addresses on the web. Only an infinitesimal portion of those trillions infringe copyright, and those infringing pages cannot be identified by Google without the cooperation of rightsholders. [...] Google relies on copyright owners to notify us when they discover that a search result infringes their rights and should be removed." (Google, 2014, 13)

Some informants expressed the view that it is complicated to determine whether or not a site is CSCI, in whole or in part. Some argued that a single notification or allegation should not be enough because there is a need to protect non-infringing sites that could be targeted by an erroneous claim.

For one, Google rates the sources of information contributing to its Trusted Copyright Removal Program for Web Search: sources supplying information that has proven correct get a better chance of seeing their claims acted upon as they become trusted parties.

Ultimately, only content owners can tell which content is legitimate and which is not.

Some existing lists of infringing sites have been built using only private resources while others have involved public entities.

Private lists

The most documented of private lists of infringing links (and some have extrapolated that some sites were massively infringing from the numerous infringing links found on them) is the one maintained by Google. (Google, on-going) Google builds this list from submissions made by rightsholders.

In addition to the Content ID system, copyright owners and their representatives can submit copyright removal notices through the YouTube Copyright Center, which offers an easy-to-use web form, as well as extensive information aimed at educating YouTube users about copyright. The Copyright Center also offers YouTube users a web form for 'counter-noticing' copyright infringement notices that they believe are misguided or abusive.

YouTube offers a Content Verification Program for rightsholders who have a regular need to submit high volumes of copyright removal notices and have demonstrated high accuracy in their prior submissions. This program makes it easier for rightsholders to search YouTube for material that they believe to be infringing, quickly identify infringing videos, and provide YouTube with information sufficient to permit us to locate and remove that material, all in a streamlined manner that makes the process more efficient.

In addition to the public content removal web form for copyright owners who have a proven track record of submitting accurate notices and who have a consistent need to submit thousands of URLs each day, Google created the Trusted Copyright Removal Program for Web Search (TCRP). This program streamlines the submission process, allowing copyright owners or their enforcement agents to submit large volumes of URLs on a consistent basis. There are now more than 80 TCRP partners, who together submit the vast majority of notices every year.

While Google's procedures have allowed them to "process copyright removal requests for search results at the rate of millions per week with an average turnaround time of less than 6 hours" (Google, 2014, 4), it leaves the initial burden of identification in the hands of the rightsholders. According to the United States Department of Commerce Internet Policy Task Force (2013, 70), "Other efforts are underway to develop helpful tools to assist advertisers in avoiding transactions with websites dedicated to piracy, such as a methodology for ranking websites based on infringement-related risk factors." No further documentation was located on these efforts.

Google makes some information on its list available in its Transparency ReportFootnote 7 (Imbert-Quaretta, 2013, 26; Imbert-Quaretta, 2014, 12-13; Weatherley, 2014a, 11) but does not provide direct access to the details.

Another private list was announced by GroupM in 2011 but little further documentation was found.

In June 2011, the largest worldwide digital advertising spender, GroupM, announced the creation of a list of 2,000 websites hosting illegal or pirated content, which it will not use for advertising for its clients.

The Trustworthy Accountability Group has recently announced the creation of a new list that will identify legitimate publishers instead of CSCI sites.

The Trustworthy Accountability Group (TAG), an advertising industry initiative to fight criminal activity in the digital advertising supply chain, today announced an industry-wide anti-fraud program, Verified by TAG, to fight digital ad fraud and bring new transparency across the digital ad ecosystem. "Verified by TAG" has two core and interlocking elements: the TAG Registry of legitimate advertisers and publishers, which will be available for application today, and a Payment ID system coming soon that will connect all ad inventory to the entities receiving payments for the ads.

Such an effort falls within the idea of site certification that some support whereby sites would open themselves to verification and audit to show their compliance with copyright rules.

Certification for sites is a great idea but it needs to be standardised and be controlled by multiple stakeholders around the industry. Ideally it would be styled around a digi startup tech company making it agile enough to keep pace with technical requirements and provide efficient way (sic) to certificate and monitor sites. The certification though should go further than e-tailers and streaming sites. Currently it is very difficult to determine for example whether promo sites and promo service companies are legitimate or not. Ensuring these types of sites also have to certificate would be great for labels and would help stop promos leaking.

The TAG initiative also "launched its Brand Integrity Program Against Piracy to help advertisers and ad agencies avoid damage to their brands from ad placement on websites and other media properties that facilitate the distribution of pirated content and counterfeit products." (TAG, 2016)

This voluntary initiative helps marketers identify sites that present an unacceptable risk of misappropriating copyrighted content and selling counterfeit goods, and remove those sites from their advertising distribution chain. The program was supported at launch by leading organizations and companies in advertising, online publishing, adtech, media and consumer protection. Under the program, TAG works with authorized independent third-party validators, including the Alliance for Audited Media (AAM), Ernst & Young and Stroz Friedberg, to certify advertising technology companies as Digital Advertising Assurance Providers (DAAPs). To be validated as a DAAP, companies must show they can provide other advertising companies with tools to limit their exposure to undesirable websites or other properties by effectively meeting one or more criteria. Some companies may also elect to fill out a Self-Attestation Checklist to become a Self-Attested DAAP. The Self-Attested DAAP Program Overview and Implementation Guide for Self-Attested DAAPs contain more information.

In 2012, the International Anti-Counterfeiting Coalition (IACC, no date) and the payment industry created RogueBlock, a payment processor initiative offering a simplified procedure for members to report online sellers of counterfeit or pirated goods directly to credit card and financial services companies. Current partners to the initiative include many of the biggest credit card and financial services companies in the world such as: MasterCard, Visa International, Visa Europe, PayPal, MoneyGram, American Express, Discover, PULSE, Diners Club and Western Union.

In RogueBlock, participating rights holders have access to an online portal to report infringing activity. The IACC network mapping analysis identifies the highest value targets for takedown investigation. The IACC reviews and subsequently distributes reports to the appropriate credit card and/or financial services company. In this initiative as in others, the onus is on the rights holders to identify and report infringement.

Lists involving public entities

Lists of CSCI sites produced with the involvement of governments are also few and far between. The US Government maintains one and the London police have used one as well. Expert advice in this regard was produced by French researchers.

The United States Trade Representative (USTR) has "identified Notorious Markets in the Special 301 Report since 2006. In 2010, USTR announced that it would begin publishing the List separately from the annual Special 301 Report, pursuant to an Out-of-Cycle Review (‘OCR'). USTR first separately published the List in February 2011." (United States Trade Representative, 2015, 2) This list is a non-exhaustive compilation based on available information.

The Office of the United States Trade Representative (‘USTR') has developed the List under the auspices of the annual Special 301 process. USTR solicited comments regarding which markets to highlight in this year's List through a Request for Public Comments published in the Federal Register. The List is based on publicly-available information. USTR selected markets not only because they exemplify global concerns about counterfeiting and piracy, but also because the scale of infringing activity in such markets can cause economic harm to U.S. IPR holders. Some of the identified markets reportedly host a combination of legitimate and unauthorized activities. Others reportedly exist solely to engage in or facilitate unauthorized activity. The List does not purport to be an exhaustive list of all physical and online markets worldwide in which IPR infringement takes place.

Much has been written about the Infringing Website List (IWL) managed by the City of London (UK) Police. It is one element of Operation Creative, which aims to reduce the flow of money to CSCI sites. The IWL is built based on input from creative industry associations but with added verification performed by the City of London Police's Police Intellectual Property Crime Unit. This public involvement gives the list a layer of credibility that other lists may lack. (Weatherley, 2014a, 14; Weatherley, 2014c, 9; Dredge, 2014; BOP Consulting, 2015, 82-85)

Operation Creative seeks to stem the flow of revenue to infringing sites by creating an infringing Website list (IWL) which is compiled by rights holders or industry bodies and overseen and managed by the City of London Police. The initiative is run by PIPCU [City of London Police's Police Intellectual Property Crime Unit] and involves participation by the British Recorded Music Industry (BPI), the International Federation of Phonographic Industries (IFPI), Federation Against Copyright Theft (FACT), the Publisher's Association (PA), the Internet Advertising Bureau UK (IAB) and the Incorporated Society of British Advertisers and the Institute of Practitioners in Advertising (IPA) (together the 'Operation Creative Partners'). [...] In practical terms, the IWL is an online portal providing the digital advertising sector with an up-to-date list of copyright infringing sites, identified by the creative industries and evidenced and verified by PIPCU, so that advertisers, agencies and other intermediaries can cease placing adverts on the specified pirate websites. The IWL was set up at the beginning of March and is still in its early stages. It currently captures just under a hundred infringing sites but that list is growing. It is also worth noting that this initiative, in collaboration with the advertising industry, rights holders and enforcement bodies, is without precedent in the world.

whiteBULLET provides a tool which rates websites on the risk of IP infringement against a universal standard. whiteBULLET has helped to identify and assess infringing websites using its iPi index and subsequently monitor the advertising (including brands, ad intermediaries and sectors) supporting such websites in the UK and US. It is hoped that its IP infringement index (IPI index) can be used by the industry and regulators on an international scale to ensure one standard is consistently applied.

In some countries, court orders could form the basis for the development (or contribution to the development) of CSCI site lists. The Alliance for Intellectual Property indicated that "We agree that search engines should use court orders […] for ISPs to block copyright infringing websites as a basis for removing those sites from their own search algorithms. Search engines should take those court rulings, based as they are on stringent evidence gathering proving that a site is egregiously infringing, and act to remove them from listings in good faith." (Weatherley, 2014b)

While no public list of CSCI sites exists in France, some researchers have sketched what the parameters of such a list could be. To them, the involvement of the state would constitute an important seal of quality and a barrier to abuse.

En l'absence de retrait durable, pourrait être envisagée la possibilité pour l'autorité publique de constater un manquement répété au droit d'auteur ou aux droits voisins à l'égard du site. [...] Cette constatation ne serait jamais automatique et ses effets seraient nécessairement limités dans le temps. Elle interviendrait après une procédure contradictoire au terme de laquelle l'autorité publique apprécierait la gravité des manquements, entendrait les explications des plateformes, s'agissant tant des mesures mises en œuvre pour éviter de nouveaux manquements que des obstacles éventuellement rencontrés, d'ordre technique ou liés aux informations détenues par les ayants droit. Elle tiendrait également compte d'un éventuel échec dans la conclusion d'un accord entre ayants droit et plateformes.

Follow-the-money counter-measures

This chapter defines "Follow-the-money" counter-measures, identifies where in the ecology of CSCI sites these counter-measure can operate, and raises the issue of the effectiveness of these measures.

Definition

Rather than attempting to curtail the behaviour of millions of users through demand side counter-measures and rather than trying to silence CSCI sites directly through take-downs or similar measures, it was proposed that measures to ‘dry up' the revenue stream of CSCI sites would be more realistic and effective. Approaches sharing this philosophy have been labelled "Follow-the-money" approaches.

‘Follow the Money' is a way of indirectly curtailing pirate sites by squeezing the way they are funded. The rationale is that by cutting the source of revenue for pirate sites, the opportunity for website owners to profit from such sites is greatly reduced and as a consequence, without advertising revenue or payment processing services, such sites quickly become commercially unviable.

C'est pourquoi, a été préconisé, en complément des mesures qui peuvent déjà être prises à l'égard des sites en cause, lesquels sont souvent domiciliés à l'étranger et très mobiles, de tenter d'assécher leurs ressources financières en impliquant les acteurs de la publicité et du paiement en ligne (approche qui consiste à : « frapper les sites au portefeuille » dite, en anglais, « follow the money »).

Considering that the profit margin of CSCI sites has been estimated at 80% to 94% (Digital Citizens Alliance, 2014, 3), a substantial reduction in revenues, and thus profitability, would be required to affect the sustainability of the CSCI business.

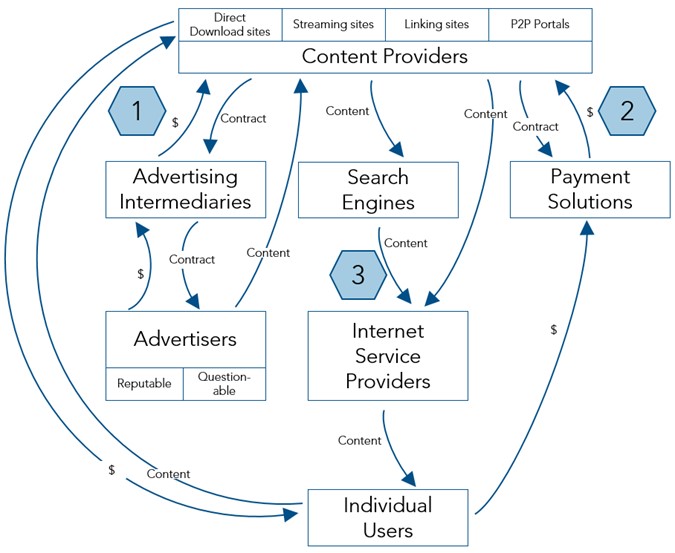

Levers

Figure 2 – Follow-the-Money Levers

Figure 2 locates the three levers that are available to follow-the-money measures in the CSCI ecology: reducing advertising is located between advertising intermediaries and CSCI sites; reducing the availability of payment solutions is located between payment solutions and CSCI sites; and reducing the visibility of CSCI sites on search engines is located between internet service providers and individual users.Reducing advertising

The reduction or the elimination of advertising on CSCI sites has been identified as one of the most promising avenues for strangling site revenues. (Weatherley, 2014a, 2) A variety of views exists as to how this could be implemented in practice. Voluntary standards and action from the advertising sector are considered both realistic and effective.

Participate in the Association of National Advertisers (ANA) and American Association of Advertising Agencies' (4A's) Statement of Best Practices to Address Online Piracy and Counterfeiting." (IAB, 2015, 7)Footnote 8

Advertisers and ad agencies, networks and exchanges can start by enhancing their voluntary best practice standards. The technology and services to identify and filter out content theft sites are available and should be adopted in the online advertising community. Just as brands do not advertise on porn or hate sites, they can take steps to assure they are not on content theft sites.

[In the Netherlands] More than 100 advertisers also committed to stop advertising on sites propagating the unlawful supply of films, series, music, books and games;

Our policies prohibit infringing sites from using our advertising services. Since 2012, we have ejected more than 73,000 sites from our AdSense program, the vast majority of those caught by our own proactive screens.

In April 2011, Google was among the first companies to certify compliance in the Interactive Advertising Bureau's (IAB's) Quality Assurance Certification program, through which participating advertising companies will take steps to enhance buyer control over the placement and context of advertising and build brand safety. This program will help ensure that advertisers and their agents are able to control where their ads appear across the web.

Italy has also begun to engage in its own 'Follow the Money' initiatives. The advertising industry (IAB Italy) and the content industry (FPM and FAPAv) have recently entered into a memorandum of understanding to support the fight against online piracy, by acting to prevent advertisement on illegal web platforms. The agreement lays the foundation for a self-regulatory mechanism that aims to block advertising on pirate sites in a similar way to Operation Creative in the UK. The rights holders will report to a joint committee, which will then communicate with agents and advertisers. Discussions are also underway in Germany and Finland.

As a largely self-regulated industry, the advertising industry has, independently, taken steps to address the concerns around advertising misplacement, in particular, through the Digital Trading Standards Group (DTSG). The DTSG is a body made up of all parts of the digital advertising ecosystem, including brands, media agencies, intermediary ad tech companies, ad networks and publishers. In December 2013, the DTSG published its Good Practice Principles (DTSG Principles) to minimise the risk of misplacement in online display advertising and to further improve standards for buyers.

While still based on voluntary action from the part of the advertisers, the involvement of the state in a mechanism can support a request to comply with a ban, as is the case in the UK:

If the site owner fails to engage with the police the website is added to an Infringing Website List (IWL) shared with major brands and advertising agencies with a request to cease advertising on that site (an attempt to drain revenue streams to the infringing site).

Technological tools and due diligence approaches can be combined, according to some, to develop a risk-based approach to ad placement.

Les acteurs de la publicité en ligne ont développé des techniques spécifiques leur permettant de vérifier que les publicités diffusées ne se trouvent pas associées à un contenu inapproprié ou illégal qui pourrait compromettre l'image de marque des annonceurs (protection de la marque ou « brand safety »). Les outils développés permettent, par exemple, de vérifier, par des techniques de filtrage a priori ou de contrôle a posteriori, qu'une publicité pour boissons alcoolisées n'apparait pas sur des sites à destination de mineurs. Ces outils peuvent être paramétrés pour éviter la diffusion de publicités sur des sites dédiés à la contrefaçon de droits d'auteur et de droits voisins. La protection des marques est un enjeu pour l'ensemble des acteurs responsables et peut se concrétiser au sein de chartes.

The main initiative of the advertising sector is the TAG (Trustworthy Accountability Group) programs. The basic logic of TAG is to "licence" components of the online advertising ecosystem to increase the trust of each stakeholder that the ad purchase that reportedly occurred did in fact take place and reached the expected target audience. As part of this initiative, the TAG partners also want to provide a mechanism to avoid (or manage) the purchasing of ads on infringing sites because this contravenes the expressed values of the industry and because it is potentially damaging to the brands advertised.

Limiting payment solutions

With regard to the limitation of payment solutions, the connection between the two ends of the economic exchange is more direct than in the case of advertising. It has been said that payment solutions should avoid supporting all illicit businesses.

Les intermédiaires de paiement (services de monnaie électronique, opérateurs de carte bancaire) devraient être encouragés à interdire, dans leurs conditions générales d'utilisation, l'utilisation de leur service à des fins de contrefaçon, et à prendre des mesures appropriées quand un manquement leur est signalé par l'autorité publique.

MasterCard has established a policy against offering payment solutions to CSCI sites. It places the burden on rightsholders to advise MasterCard of the situation. The MasterCard policy does not make reference to existing 'black lists' of CSCI sites.

When a law enforcement entity is involved in the investigation of the online sale of a product or service that allegedly infringes copyright or trademark rights of another party [...] If the Acquirer determines that the Merchant was engaging in the sale of an Illegitimate Product, the Acquirer must take the actions necessary to ensure that the Merchant has ceased accepting MasterCard cards as payment for the Illegitimate Product. […] When there is no law enforcement involvement, an intellectual property right holder may notify MasterCard of its belief that the online sale of a product(s) violates its intellectual property rights and request that MasterCard take action upon such belief. [...] If the Acquirer determines that the Merchant was engaging in the sale of an Illegitimate Product, the Acquirer must take the actions necessary to ensure that the Merchant has ceased accepting MasterCard cards as payment for the Illegitimate Product.

MasterCard sent the study team a "MasterCard Anti-Piracy Referral Form" which is a simple word document used to identify websites displaying the MasterCard logo and which "sells, offers for sale, or makes available goods and/or services that infringe the IP Owner's intellectual property rights and is not licensed or otherwise authorized to sell these goods or services." This form could not be located through Google or using the search engine at mastercard.ca.

More proactive agreements appear to have been struck since the MasterCard policy was written. In the United States, large credit card issuers, along with Paypal, have agreed to a mechanism that may reduce the flow of money towards a CSCI site. (United States Department of Commerce Internet Policy Task Force, 2013, 67) The description made of it is quite conditional, however:

C'est ainsi qu'avec l'accord sur les meilleures pratiques conclu sous l'initiative de l'administration Obama et signé par American express, Discover, MasterCard, PayPal et Visa, les intermédiaires financiers ont mis en place un dispositif de signalement par les ayants droit, suivi d'une démarche de vérification entreprise par l'intermédiaire financier ou la banque du site illicite « mandatée » par l'intermédiaire. A l'issue de l'échange engagé avec le site, l'intermédiaire financier, le cas échéant au travers de la banque du site, pourra exiger du site qu'il soit mis un terme à l'activité illicite. A défaut, les services de l'intermédiaire financier impliqué pourront cesser de lui être fournis. […] Une pratique similaire a été mise en place courant mars 2011 en Grande-Bretagne, avec la police de la ville de Londres, l'IFPI (International Federation of the Phonographic Industry) et les intermédiaires financiers Visa et MasterCard auxquels PayPal s'est joint. A la différence du système américain, les preuves sont vérifiées, après saisine des ayants droit, par la « Direction du crime économique ».

A l'heure actuelle, les services de paiement en ligne ont mis en place des procédures permettant le signalement de certaines atteintes en formalisant une procédure de saisine avec les justificatifs à fournir. Ils consacrent parfois des moyens importants au traitement des saisines qui leur sont adressées (constatations et vérifications).

Reducing visibility in search results

The contribution of search engines in a Follow-the-money strategy is to reduce traffic, which will reduce revenues – not to impact revenues directly as is the case with the advertising industry and payment solutions. (Imbert-Quaretta, 2013, 25)

As the search engine industry is primarily American, it is subject to the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), which imposes an obligation to retire content or to make access to the content impossible as soon as they are made aware of the illicit status of the activity. (Imbert-Quaretta, 2013, 26)

Search engines have been receptive to banning individual infringing links from their search results. However, because a site may not contain exclusively infringing material, search engines have been reluctant to ban entire domains:

Dans la mesure où aucun site ne contient 100% de liens illicites, les moteurs sont hostiles à l'idée de supprimer des sites entiers de leurs résultats de recherche et exigent, en principe, une injonction du juge pour procéder à un déréférencement total d'un site. La même opposition des moteurs ne se retrouve pas s'agissant de la suppression de simples liens dans leurs résultats.

Both rights holders, in submissions to me, and the culture, Media and sport committee (the 'committee') have expressed frustration by the lack of progress made by search engines in eliminating pirate material from search results. [...] It has also been shown that consumers expect search engines to promote and guide consumers towards legitimate content. [...] Removing a domain from search results will not solve piracy – although it would be a very important step in the right direction.

But many find that search engines' efforts are too tepid and that they should move to a more all-encompassing approach of site de-referencing:

We strongly endorse the proposal that search engines should promptly remove sites from their search listings that are subject to 97A site blocking actions in which affirmative court findings have been made, as described below. Additionally, we believe they should also remove sites that are identified as structurally infringing by another reliable/appropriate means. This is the bare minimum that search engines should do and would be a simple, low cost and transparent step that could have an immediate impact. However, while we consider such moves to be necessary and important, they are not sufficient on their own to effectively address this issue.

Google's main approach has been to demote references to sites that have been found to deliver artistic works in an illicit fashion in the past. The technique is not to ban these sites from search references but to demote them in the list.

Par exemple, la société Google a développé un nouvel algorithme (« demotion ») qui vise à faire baisser dans les résultats le classement des sites qui ne respectent pas le droit d'auteur. Parmi les critères pris en compte pour sous-référencer ces sites, figurent notamment le nombre de notifications auxquelles Google a donné suite pour un site. Dans ce cadre, Google publie un « Transparency Report », destiné à donner une visibilité au public sur les notifications reçues, qui comprend une section consacrée aux demandes de retrait faites sur le fondement d'une atteinte au droit d'auteur.

In addition to removing pages from search results when notified by copyright owners, Google also factors in the number of valid copyright removal notices we receive for any given site as one signal among the hundreds that we take into account when ranking search results. Consequently, sites with high numbers of removal notices may appear lower in search results.

Under attack for allegations that its Autocomplete system favoured the search for infringing sites and links, Google indicated that it had modified the algorithm to avoid offering the terms that would have such an effect.

[...] Google now excludes certain queries related to copyright infringement from its Autocomplete function, which uses algorithms to suggest complete search terms as soon as a user starts typing. This policy has resulted in the exclusion of notorious infringing services like The Pirate Bay from Autocomplete results.

Autocomplete offers real-time search term suggestions to consumers, which navigates consumers to infringing content by, on occasions, suggesting terms closely interrelated with pirate sites. Google took action on Autocomplete in December 2010, promising not to display terms most frequently used for searching for infringing content. [...] However, there continues to be concerns that Autocomplete is a driver of piracy.

Effectiveness

Follow-the-money strategies focus on the perpetrator: the CSCI site. This is made difficult by certain characteristics of these sites: anonymity, instability in location, and others.

But in terms of effectiveness, targeting suppliers of infringing content is more challenging than targeting subscribers, due (variously) to: (1) Anonymity [...]; (2) Extra territorial [...]; (3) Displacement to other countries outside jurisdiction [...]; (4) Fast speed of infringers vs the slow speed of the law and government [...].

All counter-measures face the issue of defining the target that CSCI sites represent: there is no agreed-upon operational definition of that target.

To date, there has been no conclusive industry-wide statement or guidance which explains what an infringing website actually is, how it operates or what the red flags are for such a site. There has therefore been no single credible and authoritative definition on which the industry can rely.

Recent developments may indicate that some new approaches to identifying sites and to bringing agreement among partners may be productive.

Until the appearance of the IWL, identifying infringing sites was not a straightforward or particularly robust process, but with the IWL and the DTSG Principles (and the requirement to refer to an appropriate and inappropriate schedule of websites) operating in tandem, the risk of ad misplacement should be reduced and, by extension, the instances of brands inadvertently advertising on pirate websites should also fall. It is intended that the IWL will be expressly written into the DTSG-compliant trading agreements.

Each type of counter-measure is presented with other, more specific challenges.

Reducing advertising

Advertising reduction works – to an extent. Experiences to date suggest that fewer reputable brands are found on CSCI sites and that this can be achieved through self-regulation and without binding mechanisms, at least in regard to household brands.

En revanche, les annonceurs « grands comptes » sont peu présents sur ces sites de référencement, ce qui peut laisser entendre que ces derniers et le secteur des régies et agences media en général prennent désormais des précautions supplémentaires pour ne pas diffuser des publicités sur les sites manifestement illicites. De fait, les initiatives d'autorégulation du secteur se généralisent.

Thanks to our ongoing efforts, we are succeeding in detecting and ejecting these sites from AdSense. While a rogue site might occasionally slip through the cracks, the data suggests that these sites are a vanishingly small part of the AdSense network. For example, we find that AdSense ads appear on far fewer than 1% of the pages that copyright owners identify in copyright removal notices for Search.

The introduction of the IWL follows a three month pilot that took place last year thanks to the support of Whitebullet and the Operation Creative Partners. The pilot was largely successful and had a clear and positive impact, with a 12% reduction in advertising from major brands on the identified illegal websites.

In this latter case, note that the 12% reduction over a three-month period could be a significant result but it is difficult to assess since that reduction was for "advertising from major brands" and it is unknown what proportion of ad revenues flow from major brands.

The BBC reported a substantial 73% drop in top ad spending companies advertising on IWL-listed sites after one year of Operation Creative activity. Again, this does not provide a sense of the importance of this reduction in ad revenues for CSCI sites.

Two years on, PIPCU says there has been a 73% drop in advertising from the UK's 'top ad spending companies' on the affected sites, which it suggests both reduces their income and removes their 'look of legitimacy'. The figure is based on research carried out by Whitebullet - a firm that provides online intellectual property services. It surveyed the ads placed on 17 sites that offer unauthorised access to TV shows, movies, music and games - both over a 12-week period between June and September 2013 and again between March and June 2015. [...] Mr Szyszko acknowledged, however, that some big-name ads were still getting through.

There is a clear limit to the effectiveness of strangling advertisement on CSCI sites: while the arguments against such advertising bear weight for the reputable brands, they don't to the questionable brands, which may in fact be attracted by the type of clientele encountered on CSCI sites.

[...] the largest gambling companies in the world are continuing to fund copyright infringement by persistently advertising on sites dedicated to distributing copyrighted material. [...] That almost an entire industry is able to subsidise the illegal distribution of copyrighted material is evidence of just how lax oversight currently is.

En pratique, l'étude IDATE 94 met en évidence que la plupart des annonceurs présents sur les sites de contenus et de référencement sont des sites de jeux en ligne, de jeux d'argent ou de rencontres érotiques. Des publicités pour les sites de contenus figurent en outre sur les sites de référencement. Ces derniers jouent alors le rôle d'apporteurs d'affaires aux sites de contenus et touchent à ce titre une commission.

Enfin, le marché de la publicité a vu se développer des outils destinés au contrôle et blocage de la diffusion des publicités de leurs clients lorsque cette diffusion ne correspond pas à la cible souhaitée ou lorsqu'elle apparaît sur des sites illicites (exemple : Adloox, Adverify). Cependant, ce mouvement d'autorégulation touche les seuls acteurs soucieux de la réputation de leur marque et non les régies et acteurs assimilés intégrés avec un site de contenus favorisant et organisant de façon systématique les actes de contrefaçon.

More generally, the advertising industry is less regulated than the banking industry and, as we saw earlier, individual brands do not control directly their ad placement; the complexity of the advertising industry is a challenge in the implementation of Follow-the-money approaches.

Toutefois, le secteur de la publicité est un secteur moins régulé et moins homogène que celui des intermédiaires de paiement. Dès lors l'approche fondée sur les pratiques d'autorégulation risque d'avoir des effets plus limités qu'à l'égard des intermédiaires de paiement.

Moreover, this is a never-ending battle since sites that were validated as licit at some point may change status later on. Furthermore, because laws and regulations are different from country to country, a site that is considered a CSCI site in one could possibly be legal in another.

[...] en pratique il peut être malaisé pour un intermédiaire ou un annonceur de s'assurer qu'il n'a affaire qu'à des fournisseurs d'espaces publicitaires fiables. En effet, le contenu de leur site peut évoluer après la validation de leur demande de rejoindre un réseau, ou l'intermédiaire n'est pas à même d'évaluer la légalité d'une activité ou d'un contenu (ils peuvent être conformes à la loi d'un pays A sans respecter celle d'un pays B).

The effectiveness of the TAG initiative at identifying legitimate sites and avoiding dealings with infringing sites is limited by the number of stakeholders who buy into the scheme. The current TAG entry fee is $10,000US annually (be that for a client ID or a payment ID) which could raise affordability issue for smaller players. Representatives from the industry indicated that they are trying to work through this issue. The current membership of TAG is made public on their website.Footnote 9

Limiting payment solutions

Setting aside the issue of the agreed-upon identification of CSCI sites, the withdrawal of payment solutions is simpler than the reduction of advertisement and the effect of this solution is proportional to the reliance of infringing sites on the sale of premium memberships.

Un tel mécanisme est peu ou prou celui consacré par le législateur américain pour la lutte contre les services de paris en ligne illicite. Son fonctionnement a aussi été constaté en décembre 2010 quand le site Wikileaks s'est vu privé de la plupart de ses ressources financières, les intermédiaires lui acheminant des dons (Visa, MasterCard ou PayPal) ayant décidé d'interrompre les paiements dont il bénéficiait.

Aux Etats-Unis, le Département de la Justice a cherché à empêcher la prise de paris en ligne par des Américains auprès de sites basés à l'étranger. [...] Le gouvernement a préféré se tourner vers les fournisseurs de moyens de paiement Visa et MasterCard qui, sans fondement juridique précis en ce sens, ont pris à partir de 2003 la décision de ne pas permettre l'utilisation de leurs cartes de crédit pour l'ouverture de comptes dans des casinos ou sites de paris en ligne . [...] Ce mouvement n'est pas resté confiné aux Etats-Unis : en 2004 en Grande-Bretagne, par exemple, CitiBank a contractuellement interdit aux utilisateurs de ses services de procéder à des paiements à des sites de paris. Quant à American Express, elle a décliné une politique identique à l'échelle mondiale.

A public/private initiative on this issue has led to meaningful results in the UK. The International Federation of the Phonographic Industry (IFPI) has partnered with MasterCard, Visa, PayPal, a leading prepaid card service, the UK phone payment service regulator, and the City of London Police in a program designed to curb online music piracy. As of December 2011, 24 music services had lost their payment processing and an additional 38 websites were under investigation.

In the United States, a voluntary payment processor initiative launched as an outgrowth of the U.S. Intellectual Property Enforcement Coordinator's 2010 Strategic Plan, aims to address websites that persist in intentionally selling infringing products. Under the program, participating payment processors have terminated the accounts of nearly 4,000 online merchants.

So far, the only alternatives to credit cards and Paypal for online payment solutions have been some aforementioned, relatively rare other currency exchange mechanisms.

Reducing visibility in search results

Relative to search engines, the effectiveness of counter-measures, while quantitatively substantial because millions of links are banned weekly, has been criticized. While some expressed hope that actions by search engines will reduce visits to CSCI sites, many offer observations that the results are not materializing.

Meanwhile, actions taken by Google, Microsoft and Yahoo on search could have an immediate significant impact on levels of online copyright infringement [...] companies that Government needs to persuade, and their actions would affect all pirate sites. The vital importance of search engines should therefore not be understated.

The general consensus from submissions received from rights holders is that the current initiatives employed by search engines to combat piracy are inadequate [...].

Whilst it is true that the promotion/demotion of search results does not remove consumer's (sic) access to illegal content altogether, it significantly narrows the channels available to access such content and sends a clear message that it is unacceptable to engage in piracy. […] Google agreed to change its algorithm in August 2012 to demote sites in search index with high volumes of infringing content. The recording industry claims it has seen 'no demonstrable demotion' of pirate sites since Google's algorithm change and the number of take down notices (which is determined by rights holders) in its Google Transparency Report remained flat in the three months following the change.

Google took action on Autocomplete in December 2010, promising not to display terms most frequently used for searching for infringing content. [...] However, there continues to be concerns that Autocomplete is a driver of piracy.

Rights holder representatives indicated that those involved in certain types of piracy are quite technically savvy and that they would not be deterred by technical countermeasures related to search engines.

Views from rights holders

Canadian representatives of rights holders consulted as part of this study tended not to give online piracy fighting a high priority. While they condemn unauthorized access to intellectual property and while some rights holders indicated actively reacting, they generally considered that their scarce resources are better invested in other battles and counted on global organizations to pursue the fight. Industry representatives who indicated being active in this area were associated with major companies and were part of a global effort.