Recipient survey – Emergency Support Fund for Cultural, Heritage and Sport Organizations

Between Summer 2020 and Spring 2021, Canadian Heritage collaborated with the Canada Council for the Arts, Telefilm Canada, the Canada Media Fund, Canadian Association of Community Television Users and Stations, Canadian Association of Broadcasters and the Community Radio Fund of Canada, Musicaction and FACTOR (Canada Music Fund), and all provinces and territories to develop and deliver a survey that would determine whether the COVID-19 Emergency Support Fund for Cultural, Heritage and Sport Organizations (ESF) achieved its main objectives in helping organizations maintain jobs, and supporting business continuity.

The survey was sent to approximately 10,000 ESF recipients between September 2020 and April 2021. The ESF Recipient Survey used mixed methods to gather quantitative and qualitative information. Respondents provided more than 1,000 pages of qualitative information about their experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic.

On this page

- With a 60% response rate, the survey had 5,714 responses from recipients across multiple sectors

- Impacts of the pandemic on ESF recipient organizations

- Impacts of the ESF on business continuity, jobs and organizations

- How organizations adapted, and complementary supports

- Recipient satisfaction with the ESF delivery process

- Impacts of the ESF on the sector overall

- Impacts of the ESF on diverse communities/groups/peoples

- Organizations have strategies in place to support diversity and inclusion and Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples

- Conclusion

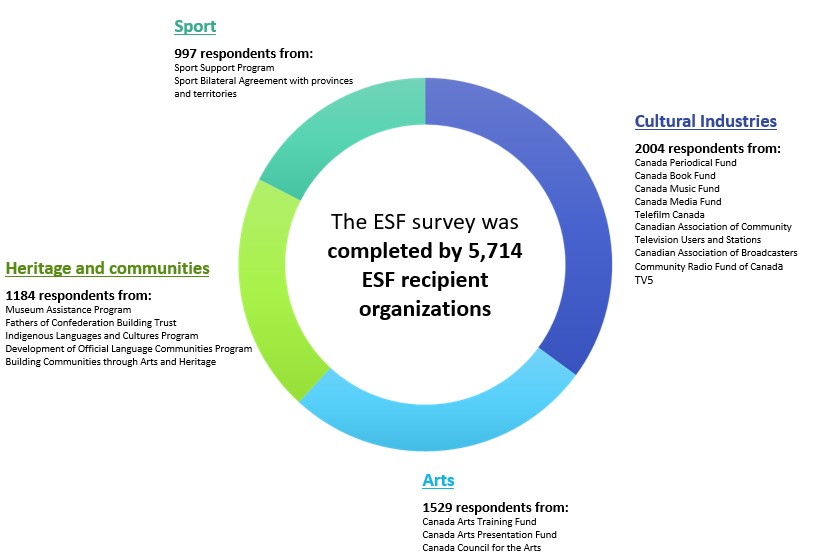

With a 60% response rate, the survey had 5,714 responses from recipients across multiple sectors

Description of the infographic: ESF Survey Responses

A pie chart containing the sentence “The ESF survey was completed by 5,714 ESF recipient organizations” surrounded by four snapshots of the four sectors the funding supported, with a breakdown of involved programs in each sector and the total number of responses from that sector;

| Sector and respondents | Programs included |

|---|---|

| Heritage and Communities - 1184 respondents |

|

| Sport – 997 respondents |

|

| Arts – 1529 respondents |

|

| Cultural Industries – 2004 respondents |

|

Impacts of the pandemic on ESF recipient organizations

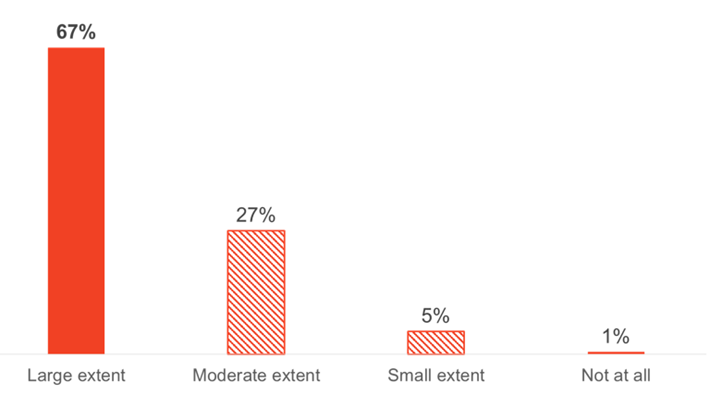

A majority of respondents reported that prior to receiving the ESF, the COVID-19 crisis affected their organization financially

Description of the infographic: Extent of Financial Effect of COVID-19 on Respondent Organizations

Bar graph showing the following results:

| Large extent | 67% |

|---|---|

| Moderate extent | 27% |

| Small extent | 5% |

| Not at all | 1% |

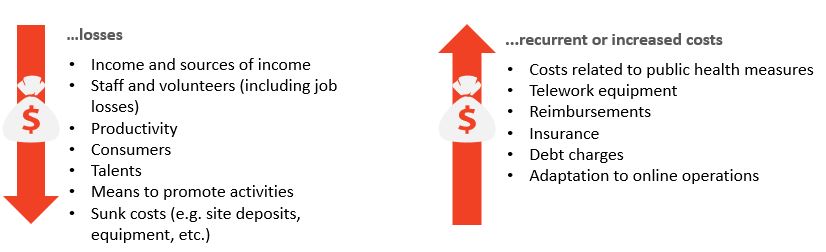

Qualitative data shows the pandemic’s financial, operational, sectoral and human impacts

Respondents felt their financial positions struck by both revenue losses and increased expenses.

Description of the infographic: Revenue losses and increased costs

Two columns, the left column titled “Revenue losses” and the right column titled “Recurrent or increased costs”.

Revenue Losses

- Income and sources of income

- Staff and volunteers (including job losses)

- Productivity

- Consumers

- Talents

- Means to promote activities

- Sunk costs (e.g. site deposits, equipment, etc.)

Recurrent or Increased Costs

- Costs related to public health measures

- Telework equipment

- Reimbursements

- Insurance

- Debt charges

- Adaptation to online operations

However, organizations also experienced impacts far beyond the financial.

The most common theme across responses to this question related to cancellation, delay, postponement or suspension of outputs, including general activities, educational activities, dissemination, revenue generation, recruitment and production. The mandated closure of venues was also an important theme, particularly noted by museums, cinemas and live music venues.

The most noted organizational capacity impact was that felt by staff. Such impacts included layoffs (either temporary or permanent), increased workload, increased stress or worry, decreased productivity, as well as the associated impact(s) of working remotely – particularly if employees had childcare and/or home-schooling responsibility in addition to their workload.

Some respondent organizations described the impacts of health measures on their organization’s activities or outputs; these included having to close their venue due to health ordinances, having to restrict attendance or visitor numbers, having to increase sanitization practices and having to increase the number of staff to ensure safe protocol administration.

Many respondents described how the halt of tourism affected their business. Likewise, impacts on distribution chains impacted newspapers. Further, many businesses withdrew sponsorship due to their own financial concerns.

Impacts of the ESF on business continuity, jobs and organizations

Responses show that the ESF met its intended objectives of supporting business continuity and maintaining jobs

- The overwhelming majority of respondents (84%) indicated they were operating and plan to continue operations, while 15% indicated that they have temporarily closed and plan to resume operations within the next six months. 1% of organizations indicated they had permanently ceased their operations.

- 77% of respondents reported that the ESF helped them stay in operation to a large or moderate extent.

- Paying for operating costs other than labour costs was the primary reason respondents sought ESF funding.

Description of the infographic: Purpose for Seeking ESF Funding

Table showing the following results:

| To pay for operating costs other than labour costs (e.g. rent, utilities, insurance, property taxes, etc.) | 65% |

|---|---|

| To pay the wages of employees in the organization | 39% |

| To adapt business model (e.g. adoption of innovative solutions and tools, digital transformation) | 38% |

| To pay self-employed workers/freelancers | 36% |

| To honour existing contracts for cancelled, postponed or modified projects (e.g. technical teams, artist fees, stage, security, facility rental) | 28% |

| To implement new required public health safety measures | 33% |

| Other | 11% |

Qualitative data provides examples of the ESF’s impacts on organizations

ESF support had significant positive impacts on organizations, and was described as having provided organizational stability and ‘breathing room’ to plan and move forward. Among other things, qualitative data showed the ESF helped organizations:

- Remain open;

- Pay staff wages and ongoing expenses;

- Mitigate the impact of lost revenues;

- Undertake strategic planning;

- Maintain or continue new and existing programming, develop new work and continue to engage end users;

- Develop or install digital infrastructure;

- Adapt to new modes of delivery (e.g. online); and

- Continue to hire or pay talent and to create new content while continuing to ensure quality.

Many respondents shared that while the ESF helped sustain operations, their pandemic-induced financial needs and revenue losses were significant. More broadly, respondents believed that the ESF represented and demonstrated a recognition, at the Federal level, in the value of Canadian arts, culture and heritage.

How organizations adapted, and complementary supports

Qualitative data provides examples of strategic measures organizations undertook to adapt and ensure sustainability

Development and innovation of new activities and outputs were the most common strategic measures undertaken by organizations to ensure sustainability. This broad theme was expressed in multiple ways across the data. For some, this theme included the development of new or innovative activities and outputs, including: programming, programs, projects, new content, events, performances, partnerships and collaborations and new modes of distribution. For others, innovation included the need to support communities, talent and the industry more generally.

Recipients also reflected a recognized need for revenue diversification and new sources of revenue, such as new sales opportunities, new advertising streams or identifying new audiences. The theme of revenue diversification also included developing new or innovative marketing, promotional campaigns and fundraising opportunities, including new sources of donations.

Examples also included re-focusing organizational scope more locally rather than nationally or internationally (for example, drawing from local talent rather than recruiting from further away or by promoting local businesses at no cost, in order to develop strong local partnerships that would ‘pay off’ in the longer term).

A second major theme to emerge from responses to this question focused on the shift to digital or online programming and activities.

Respondents perceived a virtual shift as supporting their organizational sustainability in a variety of ways. First, organizations described the importance of purchasing and installing new digital infrastructure to support the shift. In so doing, organizations intended to increase their online presence; develop new, or adapt existing, content or outputs; increase audience engagement; increase sales; enhance or promote audience engagement via websites and social media; and increase marketing, promotion, outreach, fundraising and sponsorship opportunities.

Although most organizations recognized the need to shift to digital/online activities and outputs, the importance of developing safe and sustainable in-person practices (e.g. smaller audiences, increased cleaning) was equally important; this was reflected in discussions of shifting towards hybrid activities (e.g. a show with a small in person audience that is also live streamed).

Respondents described the various ways they were endeavouring to meet health guidelines, such as increased use of personal protective equipment (e.g. masks), increased use of hand sanitizer, enacting recommended sanitation practices (including increased cleaning), ensuring that spaces can accommodate proper social distancing and restricting travel. In addition to operational changes, organizations reported offering modified end user engagement activities, such as offering in-person opportunities to smaller groups, offering hybrid opportunities (e.g. both online and in person), as well as developing innovative methods for dissemination (such as offering opportunities to ‘family bubbles’).

For many respondent organizations, a partial or full shift to virtual/digital programming was considered to be neither possible nor appropriate for their organizational type (e.g. museums, archives, performing arts, print newspapers). For these organizations, a key element of operational sustainability was being able to offer in-person activities in alignment with mandated health measures. Not only was this alignment a legal requirement, but many respondents understood that the public would be less willing to visit or engage in spaces that were seen to be ‘unsafe’. To this end, respondents reported a range of modifications undertaken in order to continue to allow ‘in person’ activities.

Reviewed or revised strategic measures, such as ensuring staff resources are used most efficiently, tight budget management, along with operational, contingency and/or emergency planning, were also key to ensuring sustainability.

At an operational level, respondents described a range of ways that their organization was adapting to the current context. Shifting from office-based to remote working was one typical method that organizations had ensured they could continue operations while restrictions were in place. For many, this included having to purchase or upgrade IT infrastructure, resulting in increased costs and, often, decreased productivity, particularly while staff were learning new systems.

Another key strategy that respondents described implementing to adapt to the current context was to review and/or modify their organization’s existing business model or operational plan. This included changing, reviewing or downsizing operations; reviewing the staffing model; ongoing or heightened budget management; and focusing on the development of partnerships, collaborations or networks to strengthen capacity and to help offset costs.

In terms of longer-term planning, many respondents stated that they were considering or developing plans that would support their organization longer-term, such as strategic planning, re-structuring, developing emergency management plans, contingency-planning, establishing a savings fund and/or general capacity-building. Although there were many respondents who were hopeful about the future, there were some that described how they could not yet discuss strategic measures to ensure sustainability as they were waiting to see what the longer-term impacts of the pandemic would be. These respondents typically expressed worry, concern and/or uncertainty about the future.

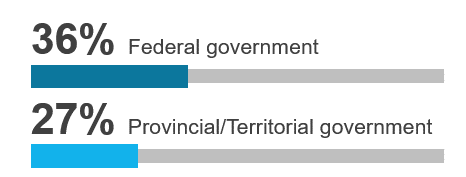

Respondents used complementary support measures to weather the effects of the pandemic

36% of respondents indicated that they received funding from other Government of Canada measures and 27% received funding from their provincial/territorial government.

Description of the infographic: Use of Other Emergency Support Measures

Bar graph showing the following results:

| Federal government | 36% |

|---|---|

| Provincial/Territorial government | 27% |

Recipient satisfaction with the ESF delivery process

Overall, respondents were satisfied with each step of the ESF’s delivery process.

The majority of respondents were satisfied with the delivery of the ESF, with 95% indicating that they were very or somewhat satisfied with the timeliness at which funds were received following the submission of the attestation/application. This is particularly important given the ESF’s mandate to support immediate business continuity needs.

Most respondents (85%) were also very or somewhat satisfied with the information they received throughout the process, and 86% were very or somewhat satisfied with the interactions they had with their program officer.

Description of the infographic: Respondent Satisfaction with the ESF

Table showing the following results:

| …timeliness at which funds were received following the submission of the attestation/application | 95% |

|---|---|

| …information received throughout the process | 85% |

| …the interaction with the program officer assigned to the organization | 86% |

Qualitative data shows that organizations had a positive experience accessing the ESF.

Almost all responses noted that the process was fast, efficient, easy and smooth; this was particularly valued at a time when everything else was entirely unsettled by the pandemic. Program officers were generally considered to have been useful, helpful and available.

When respondents expressed concerns or areas for future improvement, feedback was primarily related to the availability of information to help complete applications and meet reporting expectations. These concerns have been noted and incorporated into the Department’s Budget 2021 initiatives.

Impacts of the ESF on the sector overall

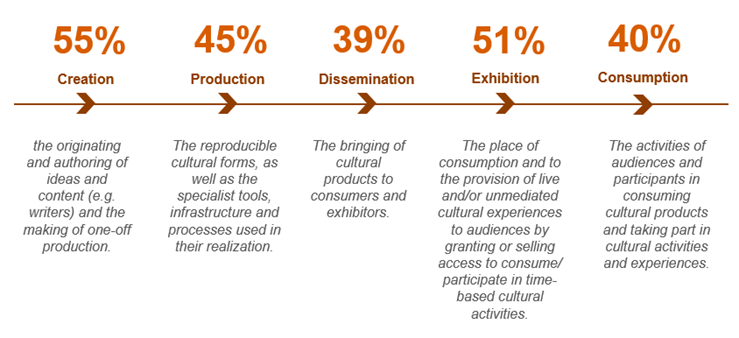

The ESF supported every part of the culture value chain

In general, responses show that the ESF provided good coverage to the entire range of the culture value chain.

Description of the infographic: The ESF supported every part of the culture value chain.

A line representing the culture value chain with percentage of responses and definitions associated with each part of the chain.

| Culture value chain section | Definition of section | Percentage of respondents |

|---|---|---|

| Creation | The originating and authoring of ideas and content (e.g. writers) and the making of one-off production. | 55% |

| Production | The reproducible cultural forms, as well as the specialist tools, infrastructure and processes used in their realization. | 45% |

| Dissemination | The bringing of cultural products to consumers and exhibitors. | 39% |

| Exhibition | The place of consumption and to the provision of live and/or unmediated cultural experiences to audiences by granting or selling access to consume/ participate in time-based cultural activities. | 51% |

| Consumption | The activities of audiences and participants in consuming cultural products and taking part in cultural activities and experiences. | 40% |

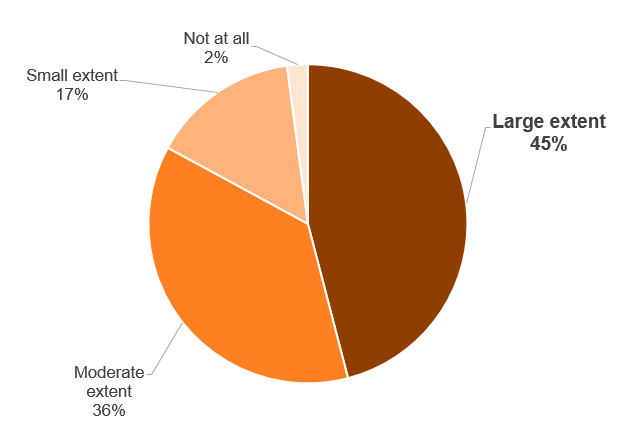

Respondents perceived that the ESF contributed to stabilizing their sector

While the cultural, heritage and sport sectors continue to suffer adversely due to the economic effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, 45% of respondents perceived that the ESF helped stabilize their sector to a large extent.

Description of the infographic: Extent to which respondents think the ESF helped stabilize their sector overall

Pie chart showing the following results:

| Large extent | 45% |

|---|---|

| Moderate extent | 36% |

| Small extent | 17% |

| Not at all | 2% |

Impacts of the ESF on diverse communities/groups/peoples

Qualitative data covers key ways organizations used the ESF to benefit diverse communities, groups and people

Develop, create or support outputs (e.g. programming, content): Respondent organizations described how funding was used to develop, create or support outputs, such as programming, content or activities for specific target communities. For some, the funding was used to develop specific new programming, while for others the funding supported the organization’s more general goal or mandate to produce content that targeted communities.

Engage and/or support as talent: Organizations used funding to hire, pay, commission or otherwise continue to engage artists. Examples of talent engagement included, but were not limited to: inviting, engaging or commissioning talent to produce new outputs; featuring or highlighting talent in programming; paying artists’ fees or honouring existing contracts; supporting new and emerging talent; and providing funding, training, residencies and/or retreats to support talent development

Engage and/or support as staff: A key theme to emerge from responses was that of parity, equality and priority, particularly amongst an organization’s staff. Women in senior or leadership roles, such as on the Board or as the owner of the company, were particularly emphasized. In addition, the theme of hiring students as staff or interns, particularly during summer break, was a notable theme that applied to youth. Respondents stated that they were able to hire or retain their staff, many of whom were described as coming from the named target communities. In addition, many respondents identified that their organization was, in itself, representative of a named community (for example, and Indigenous-owned organization). The ESF was seen to support staff from target communities through ongoing employment as well as ongoing payment of wages.

Engage and/or support as end users: Supports to end users included, but were not limited to:

- offering relevant and targeted outputs and programming;

- providing services that targeted particular demographics;

- translating resources into different languages;

- facilitating engagement for diverse audience members;

- offering space for use by different community groups;

- conducting targeted outreach activities; and

- Improve accessibility.

Organizations have strategies in place to support diversity and inclusion and Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples

Respondents reported undertaking various strategies to support diversity and inclusion and Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.

Description of infographic: Strategies to support diversity and inclusion and Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples.

Diversity and Inclusion: 78% of respondents undertake strategies to support diversity and inclusion

Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples: 45% of respondents undertake strategies to support Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples

Conclusion

At Canadian Heritage, data has been central in informing decision-making throughout the pandemic. The Covid-19 Emergency Support Fund for Cultural, Heritage and Sport Organizations recipient survey was one of the data sources that helped the department design next steps to support these sectors, which are at the heart of Canadian life, our economy, and individual and collective well-being.

Through the quick design and delivery of this recipient survey, the Department was able to collect results, best practices and lessons learned in a dynamic and continuous way throughout the pandemic. Departmental teams used this emerging data, along with other analysis, to inform the design and delivery of two Budget 2021 commitments; the Recovery Fund for Arts, Culture, Heritage, and Sport Sectors; and the Reopening Fund.