Archived - Harbourfront Centre Funding Program Evaluation Report

Approved by the Deputy Minister of Finance on the recommendation of the Audit and Evaluation Committee on December 8, 2014

Established in 2006 and renewed in 2011, the Harbourfront Centre Funding Program (HCFP) is a contribution program administered by the Department of Finance. The Harbourfront Centre (HC) is a not-for-profit cultural organization that creates events and activities to enliven, educate and entertain the public on Toronto’s waterfront. The HCFP provides $5 million annually to support HC’s operating expenses until March 31, 2016.

The primary objective of this evaluation was to assess the HCFP`s relevance and performance. Key questions that the evaluation focussed on were the extent to which there is a continued need for the federal government to fund HC’s operating expenses, and if so, at what level of funding, and in what form. To answer these questions, the evaluation examined the soundness and implementation of the HC’s sustainability strategy, a requirement of the current contribution agreement which stemmed from a recommendation of the 2010 HCFP Evaluation, and whether HC is on track to becoming self-reliant.

The evaluation relied on document reviews, key informant interviews, case studies and benchmarking analysis to draw the following conclusions on HCFP relevance and performance.

This evaluation found that the HCFP is a relevant program that is addressing a continued and justifiable need, and is in alignment with federal government priorities, roles and responsibilities.

The evaluation found that HCFP is achieving its stated outcomes and is being effectively implemented as planned. The program is appropriately managed from an administrative perspective at both the Department of Finance and HC, and HC’s operations were found to be run with due regard to economy and efficiency. Therefore, the evaluation confirmed that the current $5 million annual contribution to support HC operating expenses continues to deliver sound value for money.

The sustainability strategy submitted to the Department of Finance has been implemented as planned by HC, to increase the organization’s potential revenues, where possible. However, HC progress towards self-reliance has been limited. The evaluation noted that the Department of Finance did not establish clear expectations for HC’s financial sustainability, for example, with specific targets and timelines for reducing HC reliance on federal operational funding. This contributed to the Department and HC having different expectations for the outcomes of HC’s sustainability strategy.

HC continues to rely on the current level of HCFP funding to meet its operational expenditures and programming needs, particularly in the short term. The evaluation found that, if required, HC could likely adapt to gradual, moderate reductions to the HCFP in the medium term. The analysis conducted as part of this evaluation suggests there could potentially be annual reductions of $250,000, starting in 2018-19.

The current arrangement of multi-year contribution funding and keeping the program with the Minister Responsible for the GTA (currently the Minister of Finance) were found to be appropriate for administering the program going forward.

- Harbourfront Centre (HC) at this time relies to a significant extent on federal funding for operational expenses. We recommend that the Department of Finance seek a decision from the responsible Minister on a continuation of federal funding to the HC after March 31, 2016 through a multi-year contribution agreement that provides assistance in covering operational costs.

- In the context of any renewed funding, we recommend that the Department of Finance formally establish and communicate to HC a clear long-term funding strategy, including objectives and targets with regard to HC’s reliance on HCFP as a source of operational funding. These elements should be incorporated into any subsequent contribution agreement and program renewal documents. Clearly communicating the planned level of continued funding to HC that takes into account the Government’s long-term funding objectives and HC’s capacity and challenges for financial sustainability is a good management practice. Should the Government decide to reduce the level of funding to HC, it will allow HC to effectively plan for specific reductions going forward.

Appendix B - Evaluation Questions

Appendix C - Detailed Methodology

Appendix D - List of Documents

Appendix E - List of Interviewees

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of the Harbourfront Centre Funding Program (HCFP). The evaluation was completed for Internal Audit and Evaluation within the Department of Finance.

The objectives of the evaluation were to assess the relevance and performance of the HCFP. These dimensions were assessed using evaluation questions consistent with the core evaluation issues defined in the Government of Canada Policy on Evaluation. The evaluation also assessed the extent to which the Harbourfront Center (HC) implemented its sustainability strategy (SS) towards becoming self-reliant.

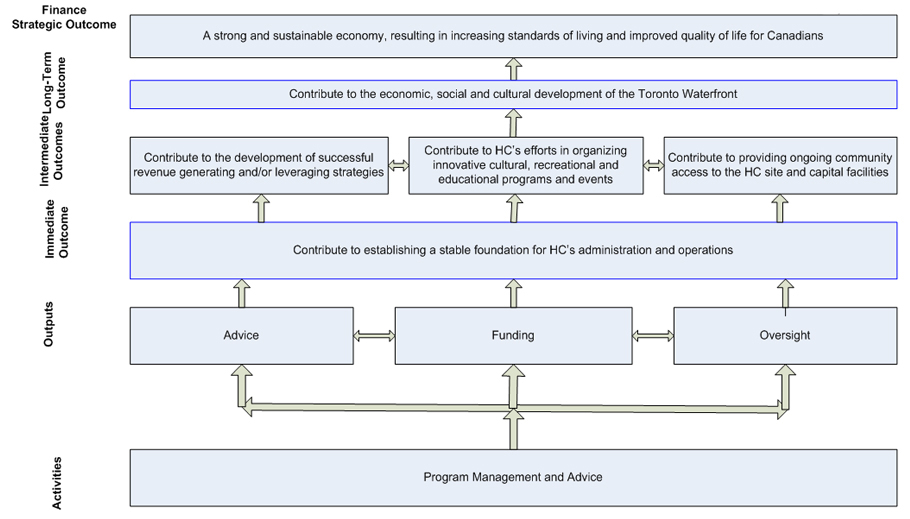

Established in 2006 and renewed in 2011, the HCFP is a contribution program administered by the federal Toronto Waterfront Revitalization Initiative (TWRI) Secretariat. Within the Department of Finance Program Alignment Architecture, the HCFP is a sub-activity under the Transfer and Taxation Payment Programs Activity that provides HC with assistance in covering operational costs. The program is currently administered by the Department of Finance Canada, and is linked to the strategic outcome of “a strong economy and sound public finances for Canadians.” The logic model for the HCFP evaluation is found in Appendix A.

HC is a not-for-profit cultural organization that creates events and activities to enliven, educate and entertain the public on Toronto’s waterfront. Its mission is to “nurture the growth of new cultural expression, stimulate Canadian and international interchange, and provide a dynamic, accessible environment for the public to experience the marvels of the creative imagination.”

The primary objective of the HCFP is to provide operational funding support to HC until March 31, 2016. Such support aims to assist HC in covering its general operating costs and the costs of maintaining and improving its on-site assets and infrastructure. The renewal of the HCFP in 2011 allowed HC to continue to provide cultural and recreational programming on the Toronto waterfront1.

The expected outcomes of the HCFP, as per the program’s logic model, are to contribute to:

- establishing a stable foundation for HC’s administration and operations;

- the development of successful revenue generating and/or leveraging strategies for HC;

- HC’s efforts to organize innovative cultural, recreational and educational programs and events;

- providing ongoing community access to the HC site and its capital facilities; and

- the economic, social, and cultural development of the Toronto Waterfront.

An evaluation of the program was conducted prior to the original funding sun-setting in 2011. That evaluation recommended the following:

- The Government of Canada (GoC) should make a decision on the appropriate level and mechanism of federal funding to support HC’s operational costs over the short term; and

- The GoC should request a plan from HC outlining its sustainability strategy over the following two to three years in the context of any renewed funding program, including a business plan for increasing revenues, sponsorship and private sector donations.

Subsequent to the evaluation and its recommendations, the HCFP was renewed at existing funding levels until March 31, 2016, with the requirement for HC to submit a sustainability strategy that included the business plan described above.

The primary objective of this evaluation was to assess the HCFP`s relevance, or the extent to which there is a continued need for the federal government to fund this program, and if so, at what level of funding, and in what form. Under the same issue, the evaluation assessed the program’s consistency with government priorities and roles and responsibilities.

The evaluation also assessed the performance of the HCFP and HC to determine the extent to which the expected results have been achieved. Given that an evaluation of the HCFP was completed in 2010 which provided a comprehensive assessment of achievement of HCFP expected outcomes, this evaluation built on these findings and focussed on more recent performance and developments since the last evaluation. In particular, the evaluation examined the soundness and implementation of the HC’s sustainability strategy, and whether HC is on track to becoming self-reliant.

Appendix B details the evaluation questions considered.

This report presents the evaluation findings and provides conclusions on the HCFP’s relevance, performance, and the implementation of HC’s sustainability strategy.

- The Detailed Results section provides a narrative of our findings and our related conclusions for both Relevance and Performance.

- The Recommendations section summarizes our Recommendations.

- The Appendices provide additional detail to support the report.

This evaluation used several standard evaluation techniques: a documentation review; interviews with key stakeholders; benchmarking; case studies; and data analysis. Appendix C outlines the methodology in more detail.

The Documentation Review included analyzing relevant HC documents, the websites and annual reports of other waterfront authorities in other Canadian cities, searching for other federal programs that aim to provide core funding for the operations of a not-for-profit organization in Canada, and a limited search for documentation related to cities outside Canada with initiatives underway to attract the public to make better use of the waterfronts and harbours of larger cities.

27 interviews with key stakeholders were completed with representatives from HC, the HC Board of Directors, the Harbourfront Foundation, the Department of Finance, Waterfront Toronto, the arts community, and federal, provincial and municipal government officials. Interviewees were selected for their expert knowledge of HC and HCFP.

The HCFP was benchmarked against similar cultural not-for-profit organizations or waterfront sites in Canada and/or abroad. The organizations used in the benchmarking analysis were not exact comparators to HC, due to differing ownership and funding structures. Nevertheless they provided useful evidence in assessing the alignment of the HCFP with government priorities, roles and responsibilities, as well as assessing the operational performance of HC, in terms of efficiency and economy.

Case studies of three (3) specific revenue-generation activities at the HC (camps, marina and parking) were undertaken. These activities were reviewed in detail and compared to external organizations/sites to pinpoint key success factors, best practices, lessons learned and potential improvements.

Data analysis was completed to identify and prioritize the observations resulting from all sources against the evaluation criteria.

The following summarizes the methodological limitations of this evaluation:

- Analysis of future funding scenarios: Assumptions used in the analysis of possible future HCFP funding scenarios are considered reasonable, but are subject to uncertainty. Alternative assumptions would affect the various scenarios that are presented.

- Attribution of results to HCFP: HCFP represents $5 million of HC’s annual budget of over $30 million, representing approximately 16% of HC’s total annual revenues and approximately 32% of its operational expenses. As such, results achieved by HC cannot be wholly attributed to HCFP funding.

- Quantification of construction impact on HC: During the on-site visits, the evaluators observed that construction beside HC limited access to its site. This construction likely has reduced ancillary revenues during the construction period (as was noted during HC interviews and in HC documentation). The construction is expected to be completed in 2015 and can be expected to impact HC revenues until that time; however, it is difficult to quantify the extent of this impact from a current and future revenue perspective. As such, we did not explicitly account for any potential increase in ancillary revenue following the completion of the construction in our scenarios and this has likely resulted in a conservative estimate (i.e., potential underestimation) of future revenues.

This section details the evaluation findings on the relevance and performance of the HCFP, according to the evaluation issues and questions outlined in Appendix B.

The core issues assessed under relevance are the continued need for the program, and its alignment with federal government’s priorities and roles and responsibilities.

The core performance issues assessed by the evaluation are the effectiveness of the program in achieving expected outcomes (as presented in the program logic model) and its design and implementation; the economy and efficiency of HC operations and a comparative assessment of the current funding model against potential alternative funding models; and the soundness and the implementation of the HC’s sustainability strategy, including the appropriateness of the organization’s risk management strategy, and the extent to which the organization is on track to becoming financially self-reliant.

The federal government has provided funding to HC since 1972, when the predecessor to HC, the Harbourfront Corporation, was created as a Crown Corporation. In 1991, the Harbourfront Corporation was restructured and resulted in the creation of a not-for-profit, HC, which has relied on federal loans, grants and contributions to continue its operations and programming activities ever since2. The HCFP itself was established in 2006 to provide $25 million in funding for support to HC over five years, ending in 2011. The intent of the funding was to fulfill a public commitment made by the Prime Minister to maintain current funding levels for HC over the next five years. The HCFP was then renewed for an additional five years, from 2011 until 2016, to continue to support the organization’s general operating costs and the costs of maintaining and improving its onsite assets and infrastructure3. In addition, the HCFP was intended to facilitate HC’s ability to leverage funding from other government sources and pursue other revenue generating strategies that would allow it to continue to provide the public with access to cultural, recreational and educational programs and activities on the Toronto waterfront.4

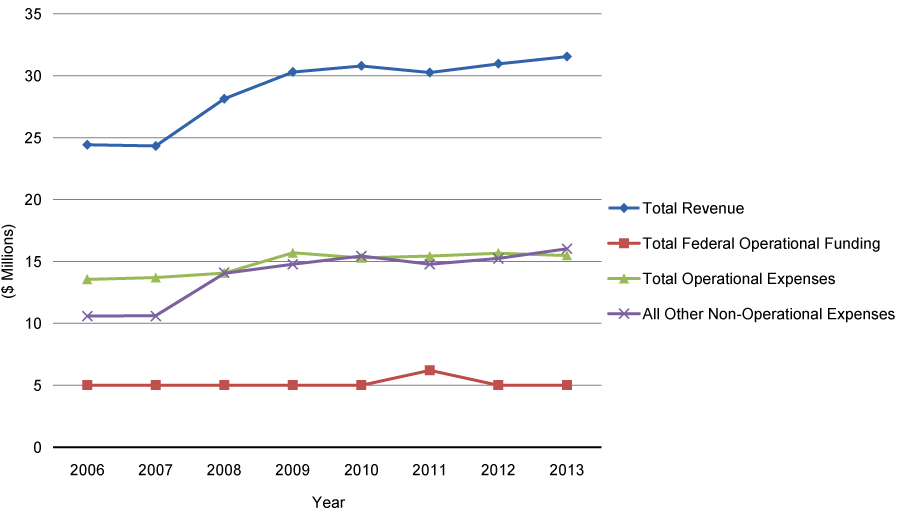

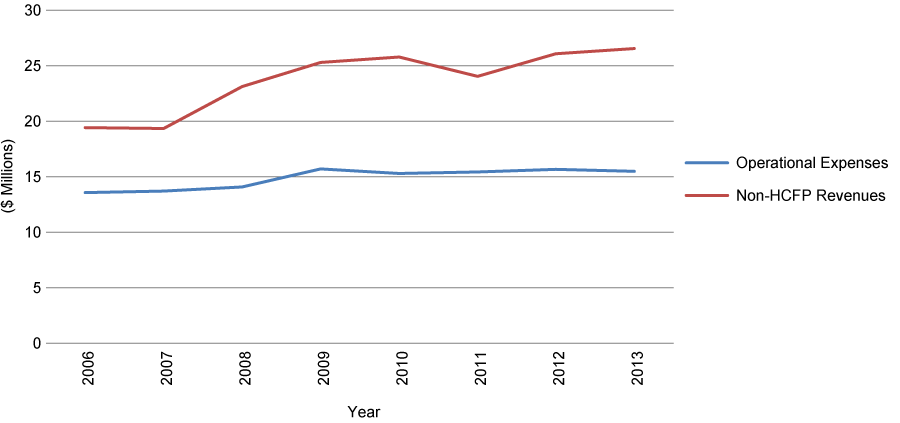

This evaluation confirmed that the $5 million annual HCFP contribution addresses a continued need in providing operational funding support to HC. In 2013, the HCFP represented approximately 16% of HC’s total annual revenues and approximately 32% of operational expenses, establishing a foundation for HC’s administrative and operational expenses.

HC Total Revenue, Total Operational Funding, Total Operational Expenses and All Other Non-Operational Expenses

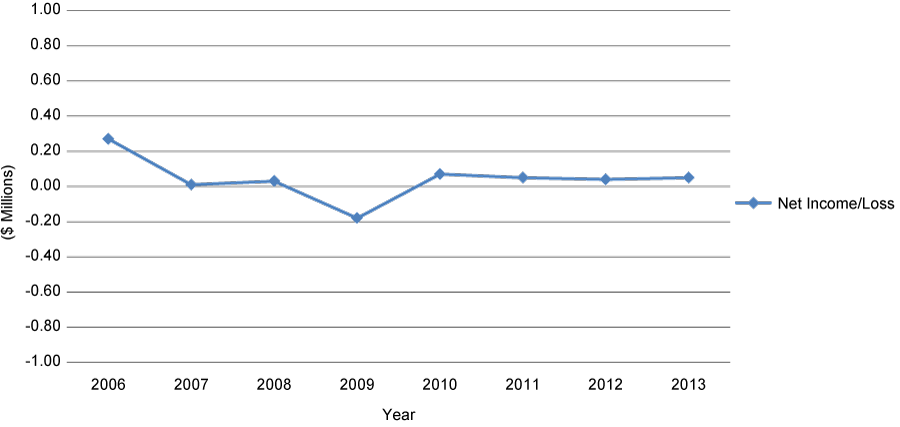

Since 2006, HC has repeatedly closed its financial year within approximately $300,000 of breaking even – either positively or negatively, i.e., revenues have consistently been approximately equal to expenses. Without the HCFP in the short-term, HC would be challenged to break-even without making significant adjustments to its operations.

Net Income/Loss

The evaluation findings, based on interviews with key informants, confirmed that the federal government’s ongoing support through the HCFP provides other funders and sponsors with a positive impression of HC’s stability. These stakeholders feel that the demonstrated commitment of the federal government enhances HC’s ability to seek funding from other levels of government and sponsors. In particular, stakeholders identified that it is difficult for organizations like HC to obtain external sponsorship for operational expenses, which the HCFP provides, compared to project and program-specific and capital funding. This viewpoint is supported by the Report of the Independent Blue Ribbon Panel on Grant and Contribution Programs, which was commissioned in 2006 by the President of the Treasury Board and sought “to recommend measures to make the delivery of grant and contribution programs more efficient while ensuring greater accountability”5. The report stated that “the community non-profit sector draws its income primarily from contributions and grants” and that “while some organizations in this sector earn revenue from services they provide, most are focussed simply on programming. They are, therefore, heavily dependent on transfers from government and are strongly affected by shifts in government policy”.6 This level of dependence on government funding appears to be the case for some organizations which have similar business lines to HC but have different ownership and funding structures. For example, the Confederation Centre of the Arts in Charlottetown (also a not for profit), and Crown Corporations, such as the National Arts Centre and the Old Port of Montreal, receive a significant proportion (more than 50%) of their revenues (as a percentage of total revenues) from either grants and contributions or appropriations.7

By addressing an ongoing operational need for HC, the HCFP is responding to the needs of the public. The 2010 Evaluation found that the HCFP was a relevant program and that HC itself is an organization that is responsive to the needs of Canadians and the artistic community, providing innovative and varied programming that speaks to a wide variety of Canadians and visitors to Canada, and satisfying the needs of those who are seeking relevant cultural expression, interesting artistic experiences and novel recreational opportunities. All lines of evidence from the current evaluation confirm that HC continues to fulfil that role, leveraging the HCFP to provide its programs and services.

Canadian Heritage recently commissioned a public opinion research study (2012, 920 Kb) into Canadians’ attitudes towards an array of arts and heritage issues, including government support and involvement in arts and culture. It concluded that “Canadians also tend to hold positive perceptions of arts and culture, with most attributing importance to it in terms of improving their quality of life and the quality of life in their communities. Focusing on their communities, most people offered mixed assessments of the quality and number of facilities in their community. In this area, there continues to be room for improvement and a natural role for government, regardless of level, to play in improving access to, and the quality of, public facilities. Canadians support government involvement in arts and culture, either directly or through partnerships and incentive strategies.”

The operational funding from the HCFP is used by HC to support the provision of community-based programming and activation. HC attracts 17.68 million visits annually (up 47.3% from 12 million in 20068) and has succeeded in becoming a cultural, educational, and recreational organization with an international reputation for excellence9. The centre is open year-round, meeting a cultural need that is important for the public and the city of Toronto, and contributing to Toronto’s economy and the activation of the waterfront.

Our findings from this evaluation are consistent with the evaluation conducted in 2010, which indicated that the HCFP aligned well to federal priorities, roles and responsibilities. Specifically, the 2010 Evaluation stated that the objectives of the HCFP supported a number of federal government priorities, including contributing to economic development through revitalization of the Toronto waterfront, and support for arts and culture. Our study confirmed this finding, as HC continues to provide an abundance of cultural programming year-round and attracts over 17 million visitors annually to the city’s waterfront, leading to a positive economic impact for the area.

Although the HCFP aligns with a number of federal government priorities, some federal government priorities have changed since the last evaluation. An overarching priority in recent years has been to manage the return to balanced budgets over the medium term10. The President of the Treasury Board reaffirmed the Government's commitment to adopting a balanced approach to ensuring responsible and strategic investments in keeping with the priorities of Canadians while continuing to eliminate the deficit11. As a result, the federal government is reviewing program funding more closely to ensure that spending meets defined needs. The majority of federal government departments and agencies have made reductions in their programs and operating budgets and have been reviewing their operating expenses and grants and contributions expenditures with the goal of finding ongoing savings of at least $4 billion by 2014–1512. As these reductions are occurring, the HCFP has remained constant at $5 million, and it is scheduled to continue at that level through to the end of the contribution agreement in 2016. When the HCFP is considered for renewal at the end of the current agreement, it can be expected to be subject to the same level of review and scrutiny to ensure it continues to be a priority for the federal government, meets an ongoing funding need, and is provided at an appropriate level. This latter issue is explored further in the Sustainability section of this report.

HC is a unique enterprise, thus there are no exact comparators. Our benchmarking exercise during this evaluation focused on waterfront development sites with a strong cultural focus and similar offerings to HC, keeping in mind that ownership and funding structures varied. The findings of the benchmarking exercise confirmed that the federal government provides support in various forms to waterfront development and cultural projects across the country, albeit the majority of the sites researched were government-owned (the level of government depended on the site). Three out of the four sites benchmarked had federal government ownership. Examples included: the Old Port of Montreal, which is a federal Crown Corporation that receives Parliamentary appropriations ($30.3 million in FY 2011-12); The Forks in Winnipeg, which is owned by the North Portage Development Corporation (NPDC) whose ownership is divided equally between the Government of Canada, the Province of Manitoba, and the City of Winnipeg; and Granville Island in Vancouver, which is managed by the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), a Federal Government Agency.

Federal government operational funding to organizations similar to HC is rare, although some examples do exist. These include federal support, through the Minister of Canadian Heritage and Official Languages, for operational expenditures of cultural organizations such as the National Arts Centre in Ottawa and the Confederation Centre for the Arts in Charlottetown. Of note, these contributions actually provide the organizations with a higher proportion of revenues (as a percentage of total revenues) than the HCFP provides to HC. In addition, a Department of Heritage contribution program for the Promotion of Linguistic Duality supports operational expenditures in some circumstances for special cultural not-for-profits. As such, this evaluation found that the HCFP is consistent with demonstrated support by the federal government for waterfront activation in major Canadian cities and public arts and culture programming.

Through its history, several different departments have operated the HCFP, to enable alignment with either the federal Minister responsible for Ontario or the Minister responsible for the Greater Toronto Area (GTA). This is appropriate given that HC is well-known by GTA-based residents and community groups, and its goals and performance are likely best understood by a locally-based Minister. The current Minister of Finance is the Minister responsible for the GTA.

The HCFP does not easily align to a single federal department, as no department has a mandate that covers all of HC’s activities and operations. HC is not only an arts and culture organization, but also offers sporting facilities (the marina and accompanying services such as kayaking and sailing), facilitates tourism (provides free public access to the waterfront, parking services, and provides 70% of its programming free of charge), and operates a large facility and outdoor area. Thus, there is no single obvious choice as to which department is the most suitable to manage the program.

From an administrative perspective, the risk of overpayment of the HCFP is very low, given that qualifying expenditures by HC far exceed the federal government contribution (as noted earlier, HCFP represents approximately 32% of eligible operating expenses). Given this low risk of overpayment, the program requires only a commensurate level of oversight and monitoring, and it is unlikely that the federal government could expect to achieve significant administrative or cost efficiencies by moving HCFP to another department that manages a higher volume of contribution agreements. Similarly, from a policy perspective, given the relatively unique characteristics of the HCFP, it is unlikely it could be managed, and the renewal negotiated, within an existing program elsewhere. In other words, it will continue to be a single-agreement program. As such, keeping the program with the Minister Responsible for the GTA (currently the Minister of Finance) remains appropriate and the best option.

Achievement of Expected Outcomes

The HCFP evaluation logic model, prepared during the planning phase of this evaluation and included in Appendix A, outlines the HCFP’s expected outcomes. The following describes the extent to which the HCFP has achieved the expected outcomes noted in the logic model.

Immediate Outcome: Contribute to establishing a stable foundation for HC’s administration and operations.

The HCFP provides HC with operating funding and with a stable foundation for its operations. Since 2006, the HCFP has provided HC with funding of between 32% and 40% of operational expenses.

As stated in the section on Relevance – Continued Need, HC has consistently closed its financial year near break-even since 2006, with small surpluses in the past few years as HC’s non-HCFP revenues have increased at a marginally greater rate than have their operational expenses. HC plans with its community partners on a multi-year basis and the multi-year HCFP agreement provides added support and stability for HC to plan its programs and events effectively. Thus, the HCFP is a stable foundation from which HC establishes its operations and builds its programming.

Intermediate Outcome: Contribute to the development of successful, revenue generating and/or leveraging strategies.

The 2010 Evaluation found that the HCFP has succeeded to a large extent in achieving all of its expected outcomes, with one notable exception - leveraging operational funding from other sources, which would be required for HC to achieve financial sustainability. It also found that the HC still relied on federal funding to a significant extent to “keep the lights on.” This continues to be the situation; however, HC has made marginal progress towards greater financial self-sufficiency since the 2010 Evaluation by implementing its SS as planned (i.e., increasing revenues where possible) and as presented to the Minister of Finance (results of HC’s SS are discussed further in the section on Sustainability, later in this report).

The federal support also helps HC obtain other sources of funding – albeit not typically operational funding. In addition, since the HCFP provides HC with a stable amount to cover operational expenses, HC can focus its attention on its programming and developing other revenue generating activities in support of its becoming more financially self-sustainable.

Intermediate Outcomes: Contribute to HC’s efforts in organizing innovative cultural, recreational and educational programs and events; and Contribute to providing ongoing community access to the HC site and capital facilities.

HC has a well-managed 10-acre site that is open to the public, activates the waterfront year-round, and provides extensive programming. Over 17 million people visit HC annually (up from 12 million in 2006), 564 cultural/community organizations worked with HC in 2012 and 2013, and HC delivered 6,155 innovative cultural, recreational and educational programs and events in 2012-13. HC offers a variety of cultural, recreational, and educational programs and events, including theatre, dance, family shows, waterfront access, visual art exhibitions, festivals, and more. Since the 2010 Evaluation, ticket theatre performance revenue has been tracking on par with expectations despite the increased competition in the Toronto small theatre market. In addition, HC operates the largest summer day camp in Toronto and one of the largest camp programs in the country, attracting more than 5,500 children annually to more than 70 different summer and March break camps. Since the 2010 Evaluation, camp and school visit revenues have met expectations and continue to grow by a small percentage each year. HC also has marina space to accommodate 400 boats in the summer and is using its marinas to capacity, and offers parking that is used by thousands of people (however, parking revenues have been limited in recent years due to the nearby construction). By providing HC with a stable base for operational funding, the HCFP allows HC to use its other revenues to maintain and increase its programming and supports HC in continuing to provide the community with access to the HC site and facilities. These Intermediate Outcomes support the HCFP in the achievement of its Long-term Outcome.

Long-term Outcome: Contribute to the economic, social and cultural development of the Toronto Waterfront and Finance Strategic Outcome: A strong and sustainable economy, resulting in increasing standards of living and improved quality of life for Canadians

As mentioned above, in 2012-13, HC delivered 6,155 cultural, recreational and educational programs and events to the Toronto community and, at the same time, activated the Toronto waterfront.

Visitors to the site likely do not only spend their tourism dollars at HC, but will also support other enterprises in the Toronto waterfront area. Thus, by supporting the draw that is HC, the HCFP is helping to support the economic, social and cultural development of the Toronto waterfront, contributing to its vibrancy and activation, and improving the quality of life for Canadians.

Program Design and Implementation

The HCFP is intended to provide funding for operating expenses as per established expenditure/budget categories. Evidence considered during this evaluation and interviews with stakeholders from within the federal TWRI Secretariat confirmed that the program has been effectively implemented as per the contribution agreement and applicable legislation and policy.

Since 2006, HC’s annual operating expenses have ranged from $13.5 million to $15.7 million. Over that period, the HCFP provided HC with funding that covered between 32% and 40% of operational expenses annually. The evidence studied during this evaluation showed that there have been no identified instances where the funding has been used to pay for expenses other than eligible basic operating expenses of HC as per established expenditure/budget categories. In addition, there is still a large amount of operational expenses that could also be used as eligible basic operating expenses as per established expenditure/budget categories if any of the claimed expenses were to be deemed inadmissible. As such, the risk of overpayment is low.

HC prepares and submits quarterly Performance Measurement Scorecards, progress reports, cash flow forecasts, and records of expenditures to the federal TWRI Secretariat. The intention of the Performance Measurement Scorecard is to provide relevant annual performance data for the HCFP, to coincide with the federal fiscal year. HC prepares the quarterly progress reports for federal TWRI Secretariat officials for monitoring purposes, including tracking against the anticipated results of the sustainability strategy. The evidence gathered during this evaluation confirmed that HC has met all reporting requirements to the federal TWRI Secretariat. In addition, HC also has audited financial statements, and its annual returns to Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) are published to the CRA website with other registered charities.

The HCFP oversight activities performed by the Department of Finance federal TWRI Secretariat are comprehensive and documented. These include annual desk audits of the management practices of HC, and financial analysis that is completed quarterly and as claims are received by the Secretariat. The federal TWRI Secretariat Director recommends approval of payments to management despite having delegated signing authority, providing additional segregation of duties.

This evaluation confirmed that the current program has been effectively implemented as per the contribution agreement and applicable legislation and policy.

Efficiency and Economy of HC Operations

The evaluation found that HC’s operations are run with due regard to economy and efficiency. This is consistent with the 2010 Evaluation, which also found that HC used HCFP funds both efficiently and economically.

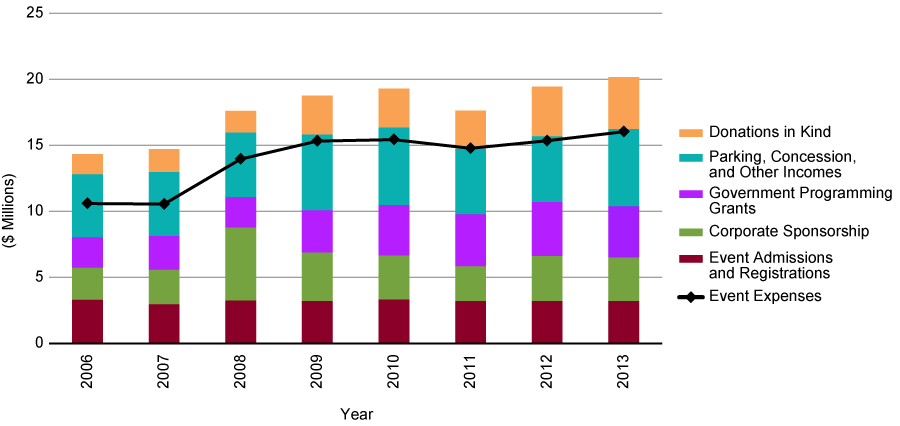

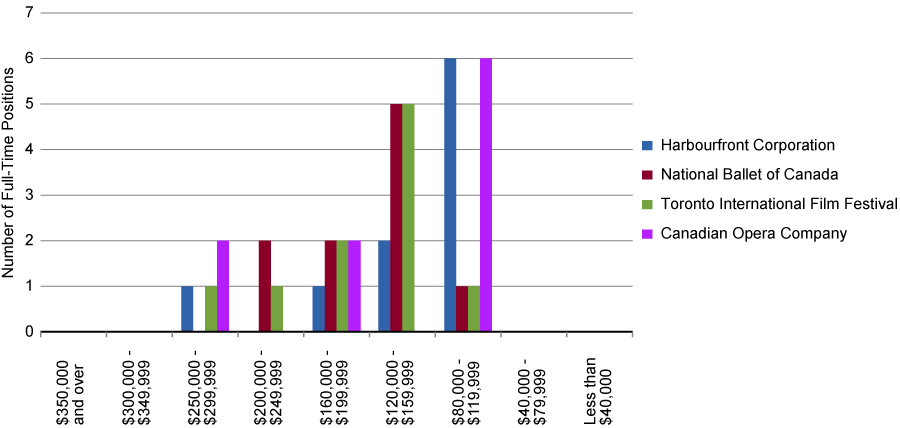

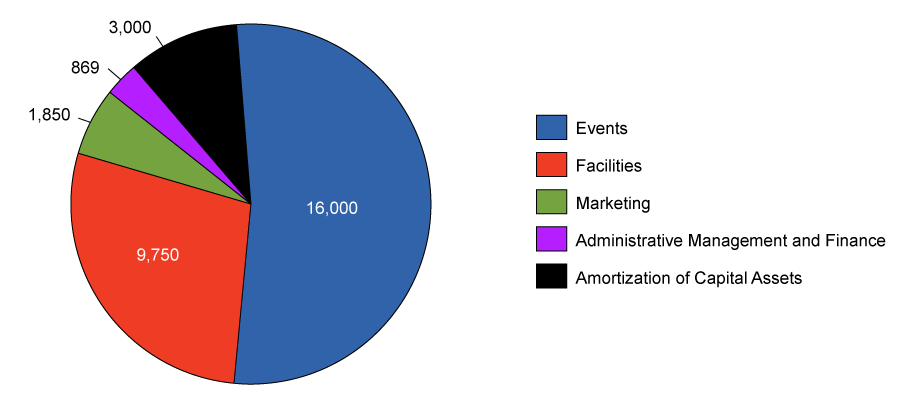

HC is managed as a lean organization. As HC expands its programming and event offerings, it is working to decrease its internal operating expenses. Between 2012 and 2013, Event expenses increased by 4.5% to approximately $16 million in 2013, while Facility expenses decreased by 0.8%, Marketing expenses decreased by 1.6%, and Administrative Management and Finance expenses decreased by 0.9%. HC employs a limited number of full-time staff (approximately 134 people) year round and engages temporary employees on an as-needed basis to supplement operations during the period of May to November.

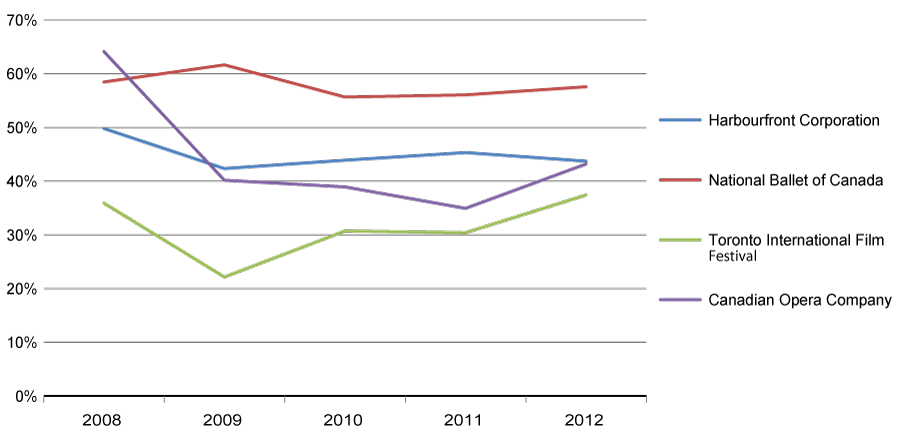

As discussed earlier, there are no exact comparators to HC. For the purposes of assessing compensation, we selected other cultural organizations based in Toronto. In terms of compensation, in the past year HC delayed an annual merit increase of 2% for full-time positions by 6 months to reduce budgeted expenses by approximately $125,000 in the year. A review of CRA returns indicated that HC salary expenditures for all full- and part-time employees are comparable with other charities devoted to arts and culture. The following graph presents total compensation as a percentage of revenue for HC and the comparative charities from 2008 to 2012. HC experienced a drop in compensation as a percentage of revenue from 2008 to 2009 (50% to 42%) and this has remained consistent since, with only a marginal differential year to year. The National Ballet of Canada is similar to HC in that the organization experienced a drop in percentage between 2009 and 2010 and has remained relatively consistent since, while the other two comparative organizations experienced significant increases from 2011 to 2012.

Total Full- and Part-Time Compensation as a Percentage of Revenue

The evaluation confirmed that HC is striving to make maximum use of the capacity of the 10-acre site. The site receives 17.68 million visitors annually at a cost of $1.85 per visitor. This is comparable to both Granville Island in Vancouver and The Forks in Winnipeg, which have similar operational components.

Case studies also confirmed that HC is managing efficient and economical operations. For example, HC delivers more camps than other GTA providers do, and HC camps remain competitively priced while offering expanded services such as extended care, bus services to and from the site, and meal plan options. HC marinas are currently operating at capacity, are providing competitive and accessible rates for docking services, and there is a five-year waiting list for a rental spot. Further, HC marinas offer additional recreational and social marina services not found at most other comparative marinas. HC parking operations are also efficient, well run, and competitive as its parking rates are consistent with or lower than comparative organizations. HC did express some difficulties maximizing parking capacity because of the construction on Queens Quay Boulevard; however, HC expects parking revenues will rebound after completion of this construction in 2015.

HC has had over 500 partnerships with various community, artistic and presenting organizations to deliver programs and events. Many of these partners also raise funds independently from HC to help produce their respective event or festival. This external financial support has helped HC to maintain relatively consistent event expenses since 2008. The following graph compares event expenses to HC revenue sources since 2006.

Event Expenses Compared to Revenue Sources

HC has gone beyond the limitations of their site to add capacity and earn ancillary revenue that supports its free programming and broader mandate. For example, HC leases off-site parkland to deliver camps and offers sailing vacations and tours to the Caribbean. HC also works with exhibitors, attendees, and contacts hosting or attending events within walking distance from the site to arrange unique parking deals and attractive group rates.

HC’s complete programming envelope is reviewed and approved annually by the Board of Directors Public Programmes Committee.13

Alternative Funding Models

The current funding model for the HCFP includes the provision of operational funding as part of a multi-year contribution agreement between the Department of Finance and HC. The evaluation found that this funding model continues to be relevant. HC plans with community partners on a multi-year basis and having a multi-year plan provides the necessary stability for HC to plan programs and events effectively.

As discussed in the section on Relevance, the HCFP funding model of providing ongoing operational funding to a cultural not-for-profit through contribution funding is uncommon; however, some examples do exist. Alternative funding models were considered during this Evaluation and are outlined in the table below:

Alternative Funding Model

| Alternative Funding Model | Advantages | Disadvantages | Impact on Effectiveness or Efficiency Compared to the Status Quo |

|---|---|---|---|

| Project-Specific Funding |

|

|

Less effective and efficient |

| Re-establishing HC as a federal Crown Corporation receiving annual parliamentary appropriations |

|

|

Less effective and efficient |

| Establishing an endowment that would deliver annual funding to HC |

|

|

Could remove need for future federal involvement |

| Continuing funding HC though annual grants |

|

|

More efficient |

The evaluation found none of the above alternatives to be superior to the current HCFP from the perspective of the funder. Although endowment funding, for example, could potentially be an option in the longer term, as it could remove the need for future federal involvement, it is beyond the scope of this evaluation to consider all potential implications. As such, at a high level, all alternative funding models considered would be expected to be less effective for planning purposes and in terms of cost effectiveness to achieve similar results in the short-term.

Thus, the evaluation found no other funding model that could be expected to deliver similar or better results than the HCFP.

Design and Implementation of Sustainability Strategy

The 2010 Evaluation of the HCFP recommended that the federal government request a plan from HC outlining its sustainability strategy (SS) over the next 2-3 years in the context of any renewed funding program. The SS was to include a business plan for increasing revenues, sponsorships, and private sector donations. The HCFP Contribution Agreement created subsequent to the evaluation, dated June 30, 2011, reflected the evaluation recommendation and stated, “HC is also required to submit a sustainability strategy by December 31, 2011, that outlines its plan to achieve greater financial self-sufficiency over the next 2-3 years in the context of the renewed funding that is the subject of this Contribution Agreement.”14 HC submitted its SS and the Minister of Finance acknowledged its receipt, thus meeting the requirements set out in the HCFP contribution agreement.

A requirement of the evaluation was to assess the soundness of HC’s SS, the extent to which that plan has been implemented and whether HC is on track to becoming self-reliant.

Through the conduct of the evaluation it became apparent that the Department and HC had different expectations surrounding the outcomes of the SS. Document review, supplemented by interviews with Department of Finance officials indicate that the purpose of requesting the SS from HC was for HC to develop and implement a plan to reduce its need for federal operational funding, thereby enabling a reduction in HCFP over time.

The HC SS and its associated Risk Management Strategy indicate HC’s approach to risk management and HC’s strategy to use its capacity, secure additional funding, and grow its revenue over time to implement its charitable mandate. The SS and Risk Management Strategy do not, however, provide for a reduction in federal operational funding, nor do they present a strategy to achieve complete financial self-reliance. HC has to date indicated that it requires ongoing support through the HCFP to remain financially viable.

The evaluation noted that the Department of Finance did not explicitly establish or communicate to HC specific expectations or target reductions with respect to HC’s reliance on HCFP, nor a clear timeline outlining when (or if) HC was expected to achieve full “financial self-sufficiency”. Interviews with Department of Finance officials confirmed that the Department does not have an explicit or implicit objective to eliminate HCFP funding, nor to achieve any given reduction in a specified timeframe.

An authoritative study, “The Report of the Independent Blue Ribbon Panel on Grants and Contribution Programs”, identifies these challenges, stating “there is often confusion between the expectations made of the recipients and the higher-order policy objectives that reside at the program level”.15 The intended results of a program should be considered at the outset of program design and the objectives and expectations clearly articulated for the recipient in the contribution agreement in a manner that is realistic and determinable.

This points to a need for the Department of Finance to establish a more clear long-term funding strategy, including objectives and targets for HC’s reliance on HCFP, and communicate these clearly to HC and other stakeholders, as appropriate going forward. This would help clarify any misunderstandings between HC and the Department of Finance in terms of intent around long-term funding strategy going forward and promote more effective achievement of program objectives.

Key questions of this evaluation focussed on the extent to which there is a continued need for the federal government to fund HC’s operating expenses, and if so, at what level of funding. The evaluation confirmed that HC is implementing its SS as planned (i.e., increasing revenues where possible) and as presented to the Minister of Finance. As highlighted in Figure 5, revenues from non-HCFP related activities (e.g., corporate sponsorship, event admissions and registrations, and parking, concession and other incomes, among others) grew on average 1.37% annually from 2010-13, while growth in operational expenses remained relatively constant at approximately 0.85% annually over the same time period. While there has been some variability in the results of individual non-HCFP related revenue sources, HC has been successful in growing total revenues at a marginally higher rate than expenditures over the past few years. Consequently, HC progress towards self-reliance has been limited and the existing SS and business plan are only modestly helping HC to become self-reliant.

Non-HCFP Revenues Compared to Operational Expenses

Our analysis of HC’s financial situation and budget16 indicates that HC continues to be substantially dependent on the HCFP to maintain its current operations and level of programming. This is also noted in the audited consolidated financial statements of the Harbourfront Corporation17. The HCFP currently represents approximately 32% of HC’s operational expenses. HC has consistently closed its financial year near break-even since 2006 (within approximately $300,000 – either positively or negatively), with small surpluses in the past few years, as HC’s non-HCFP revenues have increased at a marginally greater rate than have their operational expenses.

Potential for reduced dependence on HCFP funding

For HC to become financially sustainable and maintain its current level of programming under a scenario where HCFP was no longer available, HC would have to raise revenues by more than $5 million per year (discussed below). Alternatively HC would have to reduce its expenditures by $5 million per year, or apply some combination of raising revenues and reducing expenses, and likely reduce its current level of programming.

The following table categorizes HC’s revenue sources by HCFP funding, commercial and ancillary revenues, sponsorships and donations in kind, and other government funding (including government programming grants). These revenue sources are analyzed next to draw conclusions as to the extent to which the current level of federal funding continues to be required by HC.

Revenue Source

| Total ($ millions) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | |

| HCFP | 6.20 | 5.00 | 5.00 |

| Commercial and Ancillary Revenue | 13.51 | 13.88 | 14.46 |

| Corporate Sponsorships and Donations in Kind | 5.55 | 7.14 | 7.21 |

| Other Government Funding | 4.98 | 5.05 | 4.84 |

Commercial and ancillary revenues generated approximately $14.5 million in 2013 for HC. HC management has undertaken a number of specific and innovative actions to optimize its revenue streams, as suggested by our case studies. As part of the evaluation, three areas were selected for our case studies as a means to assess HC performance: camps, parking facilities, and marinas. These three areas were selected as they are key operational areas for HC and fundamental to non-HCFP revenue generation. The case studies included a financial analysis and a review of product and service offerings. The case studies also included a comparative analysis of HC’s camps, parking facilities, and marinas with other such offerings across Toronto and with other similar waterfront organizations across Canada with a strong cultural focus and similar offerings to HC, taking into account that ownership and funding structures varied. (i.e., Granville Island, The Forks, and Old Port of Montreal). Through the case studies, we were able to identify that HC is very actively pursuing its entrepreneurial activities to support its operations. Selected examples include: HC has established agreements to use off-site park space for additional camp programming beyond the 10-acre site; offered sailing tours to the Caribbean as expanded marina services; and arranged unique parking deals with exhibitors and attendees hosting or attending events within walking distance from the waterfront to fill parking facilities.

We believe that HC has the capability to further increase revenues from existing and potentially new commercial sources to address a possible reduction in the HCFP over time. As suggested by the SS, HC expects additional revenues from concessions in upcoming years because of its decision to manage the Lakeside Eats restaurant and Lakeside Patio as opposed to a third party. New, innovative initiatives centered on camps, parking and marinas are additional potential sources of increased revenues. Over time, HC may be able to use parking garage walls for revenue-generating advertisements, increase daily maximums for parking at HC’s parking areas, offer weekly parking passes, introduce more off-site leases to expand camp programming, increase prices for some marina services, and increase the number and length of sailing tours. While acknowledging these possibilities, we also note they are subject to uncertainty and competitive market conditions, would require time for the revenue streams to become well established, and may require some additional investments by HC.

Corporate sponsorships and donations generated approximately $7 million in 2013 for HC, representing only a 1% increase from the previous year. There is however, the possibility that HC may be able to increase sponsorships and donations going forward. For example, HC is hoping to leverage the newly constructed Ontario and Canada Square spaces to generate additional fundraising revenues through additional naming rights opportunities. HC is also focusing on the continued implementation of its Corporate Donations Strategy to appeal to corporate donations/charitable budgets as opposed to sponsorship and marketing budgets. It is important to note, and as identified in the SS, the ability to obtain sponsorship of HC’s annual programming, particularly corporately, is dependent on the density of activity taking place on the 10-acre site and the number of visitors attracted to HC’s programs and events. In the event the HCFP eliminated or significantly reduced, the number of events delivered annually and total attendance levels may be reduced thereby making it more difficult for HC to deliver measureable returns to sponsors for their investments. Ultimately, this may affect renewal rates with existing sponsors and donors as well as make it difficult to attract new, multi-year agreements.

Currently the City of Toronto provides an annual operating grant of $750,000 and a capital fund of $3 million to be disbursed over a 10-year period. This is in addition to government programming grants, which amounted to approximately $4 million in 2013. The SS projects very little growth in this area due to ongoing economic instability and stated objectives of all levels of government to reduce spending. Several key informants suggested that other levels of government have contributed to HC in response to the HCFP and without this federal involvement, ongoing municipal and provincial support could be threatened. In actual practice, it cannot be conclusively predicted how other levels of government will respond to a reduction in or the elimination of the HCFP. There is the potential other levels of government may increase, decrease, or maintain current levels of funding in response.

Collectively, non-HCFP related revenues (i.e., commercial and ancillary revenues, sponsorships and donations in kind, and other government funding) generated approximately $27 million for the HC in 2013. The SS and Risk Management Strategy state that net contribution averages 50% of gross revenue. HC would therefore, need to generate an incremental $2 million from these revenue sources to mitigate each reduction of $1 million in HCFP. In the event the HCFP is not renewed after 2016, HC would require an additional $10 million to be generated from commercial revenues in the short term. This translates to a 37% increase in non-HCFP related revenues from $27 million to $37 million to mitigate the possible elimination of the HCFP. Our financial analysis suggests this would be difficult for HC to achieve given the average growth rate for non-HCFP related revenues has been approximately 1.37% annually. To the extent alternative revenue does not increase to mitigate the reduction in HCFP, HC would have to achieve equivalent cost savings and this would be most challenging. HC’s SS states that such an event would likely lead to the wind down of HC. This viewpoint was repeated during interviews conducted for this evaluation. However, HC does have some methods to adapt to a reduction in funding over time, should it be required, by leveraging techniques used in the past to manage funding shortfalls. These techniques include, for example, receiving bank loans to self-finance or pulling more financial resources from the Harbourfront Foundation for a specified amount of time.

HC targets providing approximately 70% of its programming and events free of charge, indicating it has done so since its inception. This is an HC operating policy. The factors highlighted by HC for using this approach include: a need to maintain its charitable status, direction from the HC Board, the lease with the City of Toronto, and the constraints of operating an open site with only a limited number of closed spaces where a ticket can be required for admission to an event. A discussion with the CRA’s Charities Directorate confirmed that charities do not need to provide free services to maintain their charitable status. HC is attracting over 17 million visitors annually to its site who experience HC’s current mix of free and paid programming. HC is earning approximately $3.2 million in revenue from the programming and events for which admission is charged. If HC management and the Board were to decide to shift the ratio of free programming to paid programming over time to 60/40 as opposed to the current 70/30, all things being equal, it could possibly represent an additional $1 million in annual revenue (or equivalent cost reduction) which could be applied to mitigate a reduction in the HCFP. It is an empirical question however, whether an increase in ticket prices or charging for events that are now free would actually increase ancillary revenues for HC. If an increase in prices or new entrance fees results in a reduction in the number of visits, this could potentially reduce other ancillary revenue, for example, sponsorships, donations, parking, or restaurant revenue. This potential change in operating policy, and whether it would be achievable, would be subject to decisions by HC management and approval of the Board.

The evaluation reviewed HC salary costs in comparison to other charitable organizations. A review of CRA returns indicated that HC salary expenditures for all full- and part-time employees are comparable with other charities devoted to arts and culture. Further, HC does not compensate full-time employees in the top two salary ranges (i.e., $350K and over and $300K to $349K) and HC has a lower or equivalent number of full-time employees for each salary range when compared to the other charities we examined. This is presented in the chart below. HC competes for skills in a competitive labour market. HC has been under pressure for years, and in particular, during the current construction beside its site, to keep its costs low, including labour costs. As a result, it would likely be quite challenging for HC to achieve significant decreases in salary expenses to help compensate for a potential reduction in HCFP funding.

Ten Highest Compensated Full-Time Positions in 2012

HC has effectively implemented the strategies presented in its SS to increase revenues, where possible. For example, the Canada and Ontario Squares were constructed and are now available for use to increase sponsorship revenues, the transfer of restaurant concessions from a third party to HC management has been successful, the purchase of Queens Quay Yachting (now referred to as HC Sailing and Powerboating) resulted in a steady increase in revenues, and camps and parking have provided increased revenues as a result of alternative business deals (e.g., agreements to use off-site space for camps). The SS also continues to project growth in non-HCFP ancillary revenues to 2016, particularly once the construction on Queens Quay Boulevard is complete.

The SS notes that the transfer of the federal YQ4 garage to HC could provide an additional $1.1 million in incremental annual ancillary revenue. HC is currently in negotiations with Public Works and Government Services Canada regarding this federal garage and if successful, this would provide additional revenue that could enable HC to adapt to a reduction of federal operational funding.

Our analysis indicates that the current level of federal funding is still required by HC in the short term (the next 1-2 years)18 to maintain current operations and programming levels. In the event of non-renewal of the HCFP, HC management and the Board would have to change their current policies and approach, including a likely significant reduction in the number and/or quality of events or charging a fee for an increased portion of programming. In the event of a gradual reduction in the HCFP, HC management and the Board would have time to adjust practices and reduce expenditures accordingly over time.

Taken together, the growth in revenues as well as the effective implementation of the strategies outlined in the SS provides an indication that HC has the potential to improve its performance and move towards self-sufficiency over time. Provided non-HCFP revenue streams can continue to increase as suggested by the SS, HC has the potential to adapt to gradual reductions in HCFP in the future by applying any additional commercial and ancillary and sponsorship/donation revenues to operational expenses. This would mitigate the annual reduction in federal funding and bring HC closer to a break-even point.

Risk Management Strategy

As a follow-on to the Sustainability Strategy 2011-2016, HC developed a Risk Management Strategy in 2012. The Risk Management Strategy outlined the key risks to HC’s financial sustainability and the organization’s strategies to mitigate these risks.

There was evidence in the Risk Management Strategy of common definitions of probability and impact based on a low to high scale, as well as narrative describing how these definitions feed into the risk score, strategy and rationale. The Risk Management Strategy outlined the key risks to HC’s financial sustainability as per the common definitions. The Risk Management Strategy also outlined existing mitigation factors and strategies and action items to mitigate the risk going forward. A notable weakness of the Risk Management Strategy was the lack of an explicit definition of risk tolerance, endorsed by the Board, from which HC arrived at risk conclusions. For example, we would have expected to see an explicit definition of what level of financial loss represents a high impact to HC.

The risks considered in the Risk Management Strategy included the loss of one or more major sponsors, the loss of all federal government operational funding after 2016, a reduction in federal government operational funding after 2016, and the loss of funding available from other levels of government.

The Risk Management Strategy identifies the likelihood of a complete elimination of federal government operational (HCFP) funding after 2016 to be low (with a high impact) and the likelihood of a reduction in HCFP funding after 2016 to be moderate. The strategy for both these risks identifies that HC considers the HCFP core to its ability to continue operating at current levels in the short-term, and to its ability to obtain funding from other levels of government. As part of its defined approach to reduce the likelihood that HCFP funding will be lost or reduced in 2016 and beyond, HC makes clear its willingness and desire to comply with all reporting and information requests from the federal government, as well as periodic audits and ongoing scrutiny. HC also identified their willingness to maintain a transparent relationship with the federal government.

To mitigate the possible reduction in the HCFP, the Risk Management Strategy identifies that HC will continuously develop their commercial revenues and sponsorship growth strategies, as well as review their cost structure and refine operating efficiencies. As identified earlier, HC has made progress in these areas. In addition to the mitigation strategies outlined in the Strategy, the Harbourfront Foundation has provided temporary increased funding to meet HC’s revenue fluctuations; and, HC has a line of credit with a chartered bank.

For HCFP risks assessed in this manner, good risk management practice suggests the development of contingency plans. HC did not identify specific contingency plans to address the possible elimination of the HCFP in its Risk Management Strategy. For example, we would have expected HC to begin to build a contingency fund. HC did suggest they see the benefit in establishing a financial reserve equal to about 3 months of operational requirements (approximately $7 million); however, to date the organization has not established a reserve. It would be prudent for HC to establish a short-term financial reserve of at least 3 months’ expenditures.

A review of literature supports the advantages for a non-profit to establish a contingency fund as part of a robust financial sustainability strategy. A Rand Corporation research report entitled Financial Sustainability for Nonprofit Organizations, identifies and discusses key themes, findings, and challenges to inform operations and decision-making related to improving sustainability in non-profits. As suggested in this report, “It’s not enough (for non-profits) to have a high impact program if there’s no effective strategy for sustaining the organization financially”.19 To pursue the organizational mission and quality programming over the need to maintain financial sustainability has proven to hinder long-term growth. This report also suggested that non-profit leaders perceive government support as essential for their organization’s viability but there is no guarantee contribution agreements will be renewed in perpetuity, particularly in today’s environment where the federal government is reducing spending to achieve financial stability. Non-profits should view the process to establishing financial sustainability as a dynamic and continual process, dependent on specific key practices that ensure an organization does not become overly dependent on one source of funding. These key practices include (but are not limited to): incorporating innovative fundraising techniques, using program evaluation to demonstrate value, establishing and engaging board of directors’ leadership, and using partnerships to build capacity and acquire critical resources. Evaluation evidence suggests that HC is actively employing these practices.

Renewal of HCFP in 2016

The 2010 Evaluation noted that HC has the potential to move towards self-sufficiency over time if non-HCFP revenue sources can continue to increase. The findings of this evaluation confirm that HC has been successful in growing total non-HCFP revenues at a marginally higher rate than operational expenses over the past few years. As shown in Figure 7 below, HC’s largest expense category is events and comprises a range of items including direct event costs and full- and part-time salary costs. HC’s second largest expense category is facilities and includes costs such as utilities, building maintenance and supplies. Facility expenses are primarily fixed costs or required expenses to maintain the site at an acceptable standard. The remaining categories are currently quite lean, making up only 18% of total expenses. HC would likely have to reduce spending from within the events category in the event the HCFP is eliminated or reduced. As previously stated, reducing event costs to alleviate a reduction in the HCFP (i.e., reducing the number and/or quality of events or charging admission for more events) could reduce attendance levels and place downward pressure on non-HCFP related revenues.

Harbourfront Centre Expense Categories (thousands of dollars)

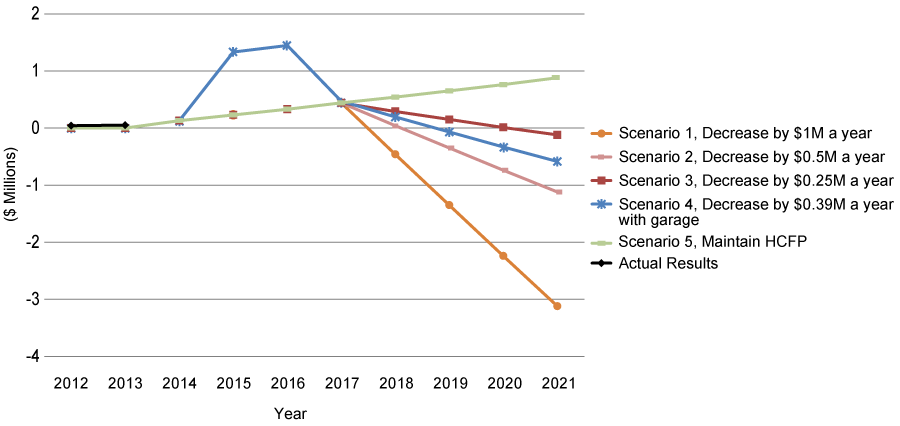

Our financial analysis of five future funding scenarios (presented below) also confirmed HC could not currently operate without the HCFP in the short-term. The analysis also indicates HC would have difficulties operating with significant reductions to the HCFP without an associated reduction at the program/event level, or changes with regard to HC’s operating policies. This is highlighted in the scenario analysis and Figure 8 below.

At the same time, our analysis also suggests that the HC could adapt to reduced funding levels over time and operate successfully with time to implement appropriate changes to mitigate a gradual drop in funding level.

Each scenario was dependent on the assumptions listed below: These assumptions were used for each scenario to ensure they were straightforward and substantiated by proven metrics. We did not include an assumption that the HC could reduce its ratio of free to paid programming because it remains unclear if this is feasible and appropriate.

- Revenues will increase by 1.37% annually (including the additional revenues earned by the YQ4 garage in scenario 4). This percentage is the average annual growth rate in HC revenues between 2010 and 2013.

- Expenses will increase by 0.85% annually. This percentage is the average annual growth rate in HC expenses between 2010 and 2013.

- City of Toronto funding will be renewed and maintained at the existing levels.

- HC will continue to provide approximately 70% of events free of charge.

- HC will continue to increase its revenues at a greater rate than its operating expenses.

The detailed results and impacts of each scenario on HC revenues and budget are presented next:

Results and Impacts of Scenarios

| Scenario Name | Description | Forecast Results |

|---|---|---|

| Scenario 1, Decrease by $1M a year | Decrease the HCFP contribution from $5 million to $1 million over 5 years, beginning in 2017. The first year of the renegotiated agreement (2017) would remain at $5 million, decreasing annually by $1 million. | HC would make a small excess of revenue over expenses until 2018, when the HCFP contribution drops to $4 million. The cumulative 5-year deficit is forecasted to be approximately $6 million. |

| Scenario 2, Decrease by $0.5M a year | Decrease the HCFP contribution from $5 million to $3 million over 5 years, beginning in 2017. The first year of the renegotiated agreement (2017) would remain at $5 million, decreasing annually by $500,000. | HC would make a small excess of revenue over expenses until 2019, when the HCFP contribution drops to $4 million. The cumulative 5-year deficit is forecasted to be approximately $1.0 million. |

| Scenario 3 – Decrease by $0.25M a year | Decrease by $0.25M a year - Decrease the HCFP contribution by $250,000 a year to $4 million. The first year of the renegotiated agreement (2017) would remain at $5 million, decreasing annually by $250,000. | HC would make a small excess of revenue over expenses until 2021, when the HCFP contribution drops to $4 million. In 2021, they would experience a small loss. The cumulative 5-year surplus is forecasted to be approximately $1.5 million. |

| Scenario 4, Decrease by $0.39M a year (with YQ4 garage) | Provide HC the revenues from the YQ4 garage and increase these by 1.37% each year. Decrease the HCFP contribution to $3.9 million in 2017 (to offset the additional $1.1 million of ancillary revenues earned by the YQ4 garage) and decrease the contribution to $1.95 million over 5 years by a reduction of $390,000 each year. This scenario was analysed because HC included transferal of the YQ4 garage in the SS. | HC would make a small excess of revenue over expenses until 2019, when the HCFP contribution drops to $3.12 million. The cumulative 5-year surplus is forecasted to be approximately $2.6 million. |

| Scenario 5, Maintain HCFP | Maintain the $5 million HCFP contribution for the full term of the renewed agreement. | With the continuation of the $5 million HCFP, HC would make an excess of revenue over expenses in each year for the full period of this scenario. The cumulative 5-year surplus is forecasted to be approximately $4 million. |

The following figure visually depicts the annual loss or surplus in revenues associated with each scenario.

Forecasted HC Revenues in Excess of Expenses

As previously noted, we believe that HC has the capability to increase its revenues over time by leveraging existing and potentially new commercial and ancillary sources and/or shifting the ratio of free to paid programming. This potential increase in revenues could effectively be applied to address any gradual reduction in the HCFP over time. The results of our scenario analysis suggest that HC could successfully adapt to annual reductions of $250,000 in HCFP funding starting in 2018, with limited impact on its level and quality of programing and performance.

HC’s operating model to date has been to leverage the increased difference between commercial and ancillary revenues and expenditures to expand programming and events and to maintain the site and associated capital assets. This is reflected in HC’s net assets, which have steadily increased over the past few years. From 2009 year-end to 2013, net assets have increased from $751,354 to $1,038,700, representing a cumulative increase of approximately $287,000. However, contribution programs are subject to renewal by the federal government and not guaranteed to continue in perpetuity. Going forward, HC and its Board could consider re-evaluating their operating model and apply any additional commercial and ancillary revenues to operational expenses to mitigate any reduction in the HCFP over time as opposed to expanding its charitable endeavours.

This evaluation found that the HCFP continues to be relevant as it is addressing a continued and justifiable need, is responding to the needs of the public, and continues to be in alignment with federal government priorities, roles and responsibilities.

With regard to performance, the HCFP is achieving its stated outcomes and is being effectively implemented as planned. The program is appropriately managed from an administrative perspective at both the Department of Finance and HC, and HC’s operations were found to be run with due regard to economy and efficiency. Therefore, the evaluation confirmed that the current $5 million annual contribution to support HC operating expenses continues to deliver sound value for money.

At the same time, the evaluation found that although the SS submitted to the Department of Finance has been implemented as planned by HC, the organization’s progress towards self-reliance has been limited. The evaluation noted that the Department of Finance did not establish clear expectations for HC’s financial sustainability, for example, with specific targets and timelines for reducing HC reliance on federal operational funding. This contributed to the Department and HC having different expectations for the outcomes of HC’s SS.

HC management was found to be pursuing numerous opportunities through which to increase its potential revenues; however, it has made limited progress in reducing the need for operational funding support through the HCFP. HC has established a risk management process that includes actions to be taken to mitigate potential fluctuations in revenue, but it is lacking a contingency reserve to better enable it to endure reductions in revenue or the loss of the HCFP.

HC continues to be dependent on the current level of HCFP annual funding in the short term (within the next 1-2 years) to maintain its current operations and level of programming. Non-renewal or a significant reduction in HCFP funding levels after March 31, 2016 would likely have significant repercussions on the quality of events, attendance levels and ancillary revenues earned. There is a risk that HC may not be able to continue its operations if the HCFP were not renewed in the short-term.

The evaluation found that HC could adapt to a gradual reduction in funding levels and operate successfully with sufficient time to adjust strategies and practices, reduce expenditures and increase existing and new ancillary revenue sources. The scenario analysis conducted as part of this evaluation suggests this could potentially be annual reductions of $250,000. The first year of the renegotiated agreement would remain at $5 million, decreasing annually by the said amount.

In terms of program funding mechanism and administration, the current contribution funding arrangement was found to be appropriate. No alternative funding models were identified that could be expected to deliver similar or better results. In addition, it was found that keeping the program with the Minister Responsible for the GTA (currently the Minister of Finance) remains appropriate and the best option.

- Harbourfront Centre (HC) at this time relies to a significant extent on federal funding for operational expenses. We recommend that the Department of Finance seek a decision from the responsible Minister on a continuation of federal funding to the HC after March 31, 2016 through a multi-year contribution agreement that provides assistance in covering operational costs.

- In the context of any renewed funding, we recommend that the Department of Finance formally establish and communicate to HC a clear long-term funding strategy, including objectives and targets with regard to HC’s reliance on HCFP as a source of operational funding. These elements should be incorporated into any subsequent contribution agreement and program renewal documents. Clearly communicating the planned level of continued funding to HC that takes into account the Government’s long-term funding objectives and HC’s capacity and challenges for financial sustainability is a good management practice. Should the Government decide to reduce the level of funding to HC, it will allow HC to effectively plan for specific reductions going forward.

Final - July 15, 2013

Relevance refers to the extent to which the HCFP addresses a demonstrated need to Canadians. It also includes an assessment of the extent to which the program aligns with the roles and responsibilities and the priorities of the federal government and/or the Department of Finance.

For the purpose of this evaluation, relevance includes a consideration of the appropriateness of the current funding model and alignment with government priorities. Specific evaluation questions include:

- To what extent is the HCFP addressing a continued and justifiable need? Is the HCFP responding to the needs of the public?

- Is the HCFP well aligned to federal government priorities, roles and responsibilities? If yes, is the Department of Finance the most suitable department to manage this program? If not, which federal department is best positioned to manage the HCFP?

Performance refers to the HCFP’s achievement of its expected outcomes, including an assessment of the efficiency, economy and effectiveness of the management practices both at HC and the Secretariat. Performance also includes an assessment of the robustness and appropriateness of HC’s sustainability strategy. Evaluation questions include:

Achievement of expected outcomes

- To what extent has the HCFP achieved its expected outcomes (refer to various outcomes in the proposed logic model)?

Program design and implementation

- Has the HCFP been implemented according to its original design (e.g., has the funding been used for the intended purposes?)

- Has the HCFP been appropriately managed (both at the Department of Finance and HC levels) to achieve its intended objectives?

Efficiency and economy

- Has HC been conducting its operations efficiently and economically? What can be done to improve the efficiency and economy of HC’s operations?

Alternative funding models

- Is the current funding model still relevant?

- Would relevance (or performance be improved through the use of alternative funding models such as project-specific funding or renewed operational funding with specific provisions?

- Is the current arrangement (providing operational funding) the most efficient and economical use of government resources?

- Are there any potential alternative funding models (as assessed under relevance above) that could be expected to deliver similar or better results?

Design and implementation of the sustainability strategy

- Is the sustainability strategy that was prepared following the last evaluation still relevant? Is the current level of federal funding still required?

- To what extent has HC been able to implement the sustainability strategy?

Progress towards sustainability

- To what extent has the main objective of the sustainability strategy (i.e. Helping HC become self-reliant) been achieved (the extent to which HC has made progress towards financial self-reliance)?

- Is the existing sustainability strategy and business plan working (i.e., helping HC become self-reliant)? If yes, how long will it take for HC to fully achieve its objectives? If not, why not? And, what can be done to improve it (i.e., to advance the achievement of this objective)?

- Is there an appropriate risk management process in place to mitigate potential fluctuations in revenue?

Implications for program renewal

- What would be the short-term and long-term implications of non-renewal of the HFCP?

It is important to ensure that the HCFP is relevant, that it is delivered as intended, and is achieving results as stated. The methodology outlined below was designed to demonstrate the extent to which the above conditions have been satisfied.

The evaluation team reviewed relevant documents, including contribution agreements, TB submissions, Board minutes, annual reports, media reports on events at HC, the sustainability strategy, and business planning and plans, risk management assessments and plans, and previous accountability, audit and evaluation related documents. An expanded literature review looked at special studies and related evaluation reports.