Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada

Foreword by the Minister of Finance

Chapter 3: Assessment of Money Laundering Threats

Chapter 4: Assessment of Terrorist Financing Threats

Chapter 5: Assessment of Inherent Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Vulnerabilities

Chapter 6: Results of the Assessment of Inherent Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing Risks

Annex: Key Consequences of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing

Our Government is deeply committed to keeping Canadians safe and our country secure and prosperous.

That is why we are committed to helping ensure the safety and security of all Canadians by giving law enforcement and security agencies the tools they need to protect Canadians from the ever-evolving threat of terrorism and organized crime.

To this end, in Economic Action Plan 2015, our Government provided additional investigative resources to our law enforcement and national security agencies to allow them to keep pace with the evolving threat of organized crime and terrorism, including addressing the issues of terrorist financing and money laundering.

Canada's existing anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing regime is strong and comprehensive, comprising 11 federal departments and agencies, eight of which are receiving dedicated funding of approximately $70 million annually.

It's a regime that is constantly adapting in both scope and ability, as it must in an uncertain world, subjected to the highest standards of scrutiny and review both domestically and by international peers. It balances the need for public safety with preserving the core principles of the civil liberties that make Canada a beacon of liberal democracy.

It supports the work of law enforcement and intelligence agencies, and is a key part of Canada's efforts to counter terrorism and transnational organized crime.

And it extends to the approximately 31,000 reporting entities—from money services businesses and casinos right up to life insurance companies and banks.

However, we know that we are now on the front lines of a real, urgent and dangerous conflict.

That is why we continue to work through the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)—a body Canada helped create nearly 30 years ago that sets standards and promotes effective implementation of legal, regulatory and operational measures for combating money laundering and terrorist financing, to develop common international standards that help us stay ahead of criminals on a global scale while making our own regime even stronger.

In the fight to counter terrorist financing and money laundering, we can only secure our nation's security and the integrity of our financial system by taking the fight beyond our borders, and we are only as strong as our weakest link. Our leadership on the international stage reflects our commitment to strengthen that global chain.

And we continue to strengthen our own link within it.

That is why the Department of Finance, consistent with international standards outlined by the FATF, has led a whole-of-government initiative to develop the Assessment of Inherent Risks of Money Laundering and Terrorist Financing in Canada report to better identify, assess and understand inherent money laundering and terrorist financing risks in Canada on an ongoing basis.

This work is an important initial assessment of our existing risk framework that helps us to better understand and identify money laundering and terrorist financing activities in Canada.

This work will be a valuable tool for our regime partners, for reporting entities, and for all Canadians who want to equip themselves with a greater awareness of trends and challenges.

It will inform ongoing and future action at a policy level, and provide critical risk information to industry so that we can effectively tackle the challenges we face together in protecting Canadians and our country.

We know that working with regime partners, reporting entities and the private sector more broadly is essential to maintaining the strength of the regime.

And we know that our partners need the benefit of our insights to undertake their own risk analysis, and introduce the operational changes required to make a strong system even stronger.

Canadians expect our Government to take these terrorist threats very seriously. We will not allow terrorism to undermine our way of life or that of others around the world. Canadians reject the use of terrorist violence, no matter where it takes place.

And that is why we will continue to remain vigilant in our battle against money laundering and terrorist financing to protect our communities, and the lives of Canadians.

The Honourable Joe Oliver, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Finance

Ottawa, July 2015

Canada has a robust and comprehensive anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing (AML/ATF) regime, which promotes the integrity of the financial system and the safety and security of Canadians. It supports combating transnational organized crime and is a key element of Canada's counter-terrorism strategy.

The Government of Canada has conducted an assessment to identify inherent money laundering and terrorist financing (ML/TF) risks in Canada. This report does not assess how effectively Canada responds to the challenges posed by money laundering and terrorist financing. Rather, it is meant to increase the situational awareness of Canada's financial institutions and of all Canadians who, as participants in the global economy, may face challenges to the normal conduct of business. This report also includes a process to update this assessment over time. The report provides an overview of the risks of money laundering and terrorist financing before the application of any mitigation measures. Those measures include a range of legislative, regulatory and operational actions that prevent, detect and disrupt money laundering and terrorist financing.

Canada has a comprehensive AML/ATF regime that provides a coordinated approach to mitigating the inherent risks identified in this assessment and combating money laundering and terrorist financing more broadly. The AML/ATF regime is operated by 11 federal regime partners, eight of which receive dedicated funding totalling approximately $70 million annually.[1] The inherent risks identified are being addressed through a strong regime that focuses on policy coordination, both domestically and internationally; the prevention and detection of money laundering and terrorist financing in Canada; disruption activities, including investigation, prosecution and the seizure of illicit assets; and the implementation of measures to ensure the ongoing improvement of the AML/ATF regime.

This report is meant to provide critical risk information to the public and, in particular, to the approximately 31,000 entities that have reporting obligations under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA), whose understanding of inherent, foundational risks is vital in applying the preventive measures and controls required to effectively mitigate these risks. The Government of Canada encourages these entities to use the findings in this report to inform their efforts in assessing and mitigating risks. Understanding Canada's risk context and the main characteristics that expose sectors and products to inherent ML/TF risks in Canada is important in being able to apply measures to effectively mitigate them.

This report also responds to the revised Financial Action Task Force's (FATF) global AML/ATF standards calling on all members to undergo an assessment of ML/TF risks. This report will be considered as part of the upcoming FATF Mutual Evaluation of Canada, which will assess Canada against these global standards.

The inherent risk assessment consists of an assessment of the ML/TF threats and inherent ML/TF vulnerabilities of Canada as a whole (e.g., economy, geography, demographics) and its key economic sectors and financial products, while taking into account the consequences of money laundering and terrorist financing. The overall inherent ML/TF risks were assessed by matching the threats with the inherently vulnerable sectors and products through the ML/TF methods and techniques that are used by money launderers, terrorist financiers and their facilitators to exploit these sectors and products. By establishing a relationship between the threats and vulnerabilities, a series of inherent risk scenarios were constructed, allowing one to identify the sectors and products that are exposed to the highest ML/TF risks.

The ML threat assessment examined 21 criminal activities in Canada that are most associated with generating proceeds of crime that may be laundered. It also examined the ML threat emanating from third-party money laundering, which includes money mules, nominees and professional money launderers. The ML threat was rated very high for corruption and bribery, counterfeiting and piracy, certain types of fraud, illicit drug trafficking, illicit tobacco smuggling and trafficking, and third-party money laundering. Transnational organized crime groups (OCGs) and professional money launderers are the key ML threat actors in the Canadian context. Many of these threats are similar to those faced by several other developed and developing countries.

The TF threat was assessed for the groups and actors that are of greatest concern to Canada. The assessment indicates that there are networks operating in Canada that are suspected of raising, collecting and transmitting funds abroad to various terrorist groups. Despite these activities, the TF threat in Canada is not as pronounced as in other regions of the world, where weaker ATF regimes can be found and where terrorist groups have established a foothold, both in terms of operations and financing their activities.

The inherent ML/TF vulnerabilities are presented for 27 economic sectors and financial products. The assessment indicates that there are many sectors and products that are highly vulnerable to money laundering and terrorist financing. Of the assessed areas, domestic banks, corporations (especially private for-profit corporations), certain types of money services businesses and express trusts were rated the most vulnerable, or very high. The vulnerability was rated high for 16 sectors and products, medium for five sectors and products and low for one sector. Many of the sectors and products are highly accessible to individuals in Canada and internationally and are associated with a high volume, velocity and frequency of transactions. Many conduct a significant amount of transactional business with high-risk clients and are exposed to high-risk jurisdictions that have weak AML/ATF regimes and significant ML/TF threats. There are also opportunities in many sectors to undertake transactions with varying degrees of anonymity and to structure transactions in a complex manner.

By connecting the threats with the inherently vulnerable sectors or products, the assessment revealed that a variety of them are exposed to very high inherent ML risks involving threat actors (e.g., OCGs and third-party money launderers) laundering illicit proceeds generated from 10 main types of profit-oriented crimes. The assessment also identified five very high inherent TF risk scenarios that involve five different sectors that have been assessed to be very highly vulnerable to terrorist financing, combined with one high TF threat group of actors.

This risk assessment is an analysis of Canada's current situation and represents a key step forward in providing the basis for the AML/ATF regime to promote a greater shared understanding of inherent ML/TF risks in Canada on an ongoing basis. The assessment will help to continue to enhance Canada's AML/ATF regime, further strengthening the comprehensive approach it already takes to risk mitigation and control domestically, including with the private sector and with international partners.

Money laundering and terrorist financing (ML/TF) compromise the integrity of the financial system and are a threat to global safety and security. Money laundering is the process used by criminals to conceal or disguise the origin of criminal proceeds to make them appear as if they originated from legitimate sources. Money laundering frequently benefits the most successful and profitable domestic and international criminals and OCGs. Terrorist financing, in contrast, is the collection and provision of funds from legitimate or illegitimate sources for terrorist activity. It supports and sustains the activities of domestic and international terrorists that can result in terrorist attacks in Canada or abroad causing loss of life and destruction.

The Government of Canada is committed to combating money laundering and terrorist financing, while respecting the Constitutional division of powers, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the privacy rights of Canadians. The Government of Canada has put in place a robust and comprehensive anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing (AML/ATF) regime. The regime is operated by 11 federal departments and agencies, each responsible for certain elements of it, as well as other departments and agencies that support the regime's efforts, coordinated by the Department of Finance Canada.[2] Provincial and municipal law enforcement bodies and provincial financial sector and other regulators are also involved in combating these illicit activities. Within the private sector, there are almost 31,000 Canadian financial institutions and designated non-financial businesses and professions (DNFBPs)[3] with reporting obligations under the Proceeds of Crime (Money Laundering) and Terrorist Financing Act (PCMLTFA), known as reporting entities, that play a critical frontline role in efforts to prevent and detect money laundering and terrorist financing.

The regime's understanding of ML/TF risks plays a key role in its ability to effectively combat these illicit activities. That understanding helps to support the policy-making process to more effectively address vulnerabilities and other potential gaps in the regime. It helps to inform operational decisions about priority setting and resource allocation to combat threats and to focus on those that have the greatest economic, social and political consequences. It also plays a central role in how the private sector applies its risk-based approaches and mitigates its risks. Overall, the regime's understanding of risks helps to ensure that it is focused on adequately mitigating the risks of greatest concern to Canada.

Given the central role that the understanding of risk plays in the regime, the Government of Canada has built on existing practices to develop a more comprehensive assessment to identify and assess ML/TF risks in Canada.[4] This assessment consists of a foundational risk assessment and a process to periodically update the results. This report presents the results of the assessment of inherent ML/TF risks in Canada. These are the fundamental risks in Canada, which the AML/ATF regime seeks to control and mitigate. The report specifically examines these risks in relation to key economic sectors and financial products in Canada and it assesses the extent to which key features make Canada vulnerable to being exploited by threat actors to launder funds and to finance terrorism. It is meant to raise awareness about Canada's risk context and the main characteristics that expose these sectors and products to ML/TF risks in Canada. Properly understanding these inherent risks is critical in being able to identify and apply measures to effectively mitigate them. In this regard, the Government expects that this report will be used by financial institutions and other reporting entities to better understand how and where they may be most vulnerable and exposed to inherent ML/TF risks and to ensure that these risks are being effectively mitigated. It will also be used by policy makers and operational agencies to set priorities and assess the effectiveness of measures to address ML/TF risks.

The first chapter describes Canada's AML/ATF regime and the comprehensive approach taken to mitigate the inherent ML/TF risks that are the subject of this assessment. The second chapter provides a general description of the methodology used to assess the inherent ML/TF risks in Canada, while the subsequent three chapters present the results of the assessment of the ML/TF threats and inherent ML/TF vulnerabilities. These components of risk are then combined in the final chapter to provide an assessment of the inherent ML/TF risks in Canada, including setting out a number of inherent risk scenarios.

The content of the report reflects what was available and deemed pertinent up to December 31, 2014, and it excludes some information, intelligence and analysis for reasons of national security.

Canada has a comprehensive AML/ATF regime that provides a coordinated approach to mitigating the inherent ML/TF risks identified in this assessment and combating money laundering and terrorist financing more broadly. This chapter briefly reviews the framework that exists in Canada to prevent, detect and disrupt money laundering and terrorist financing. The regime also complements the work of law enforcement and intelligence agencies engaged in fighting domestic and transnational organized crime as well as terrorism, notably as part of Canada's Counter-Terrorism Strategy.

The AML/ATF regime is operated by 11 federal regime partners, eight of which receive dedicated funding totalling approximately $70 million annually. The eight funded partners are the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA), the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA), the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), the Department of Finance Canada, the Department of Justice Canada, the Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada (FINTRAC), the Public Prosecution Service of Canada (PPSC) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Although not receiving dedicated funding, Foreign Affairs, Trade and Development Canada (DFATD), the Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions (OSFI) and Public Safety Canada make important contributions to the regime.

The regime is also supported by other federal departments, such as Industry Canada and Public Works and Government Services Canada (PWGSC), as well as provincial financial sector and other regulators and provincial and municipal law enforcement agencies. Within the private sector, there are almost 31,000 Canadian financial institutions and DNFBPs with reporting obligations under the PCMLTFA playing a critical frontline role in efforts to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.

The AML/ATF regime operates on the basis of three interdependent pillars: (i) policy and coordination; (ii) prevention and detection; and (iii) investigation and disruption.

The first pillar consists of the regime's policy and legislative framework as well as its domestic and international coordination, which is led by the Department of Finance Canada. The PCMLTFA is the legislation that establishes Canada's AML/ATF framework, supported by other key statutes, including the Criminal Code.

The PCMLTFA requires prescribed financial institutions and DNFBPs, known as reporting entities, to identify their clients, keep records and establish and administer an internal AML/ATF compliance program. The PCMLTFA creates a mandatory reporting system for suspicious financial transactions, large cross-border currency transfers and other prescribed transactions. It also creates obligations for the reporting entities to identify ML/TF risks and to put in place measures to mitigate those risks, including through ongoing monitoring of transactions and enhanced customer due diligence measures.

The PCMLTFA also establishes an information sharing regime where, under prescribed conditions respecting individuals' privacy, information submitted by the reporting entities is analyzed by FINTRAC and the results disseminated to regime partners and the general public. The information disseminated under the PCMLTFA can be intelligence used to support domestic and international partners in the investigation and prosecution of ML/TF related offences. The information can also be in the form of trend and typology reports used to educate the public, including the reporting entities, on ML/TF issues.

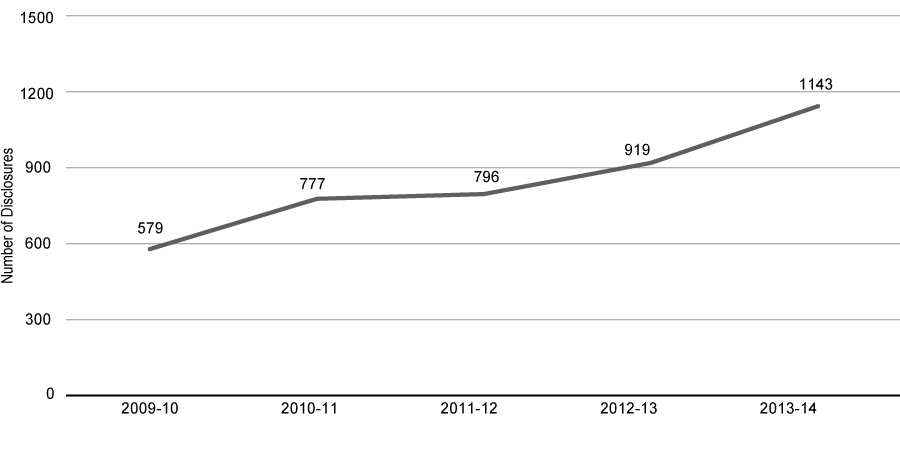

Chart 1 below provides the annual number of cases disclosed by FINTRAC to regime partners from 2009–10 to 2013–14. For example, in 2013–14, FINTRAC made 1,143 disclosures to regime partners. Of these, 845 were associated with money laundering, while 234 dealt with cases of terrorist activity financing and other threats to the security of Canada. Sixty-four disclosures dealt with all three areas.

Chart 1

FINTRAC Case Disclosures from 2009–10 to 2013–14[5]

Given the number of regime participants and the complexity of the issues, the effective regime-wide coordination of strategic, policy and operational matters is important. In addition, given that many serious forms of money laundering and terrorist financing often have international dimensions, Canada's cooperation internationally is also a key component. International cooperation is a core practice of the regime, and for many partners it is conducted on a routine basis, in particular in supporting investigations and prosecutions of money laundering and terrorist financing, including through formal mutual legal assistance led by the Department of Justice Canada.

Canada recognizes that protecting the integrity of the international financial system from money laundering and terrorist financing requires playing a strong international role to broadly increase legal, institutional and operational capacity globally. Canada's international AML/ATF initiatives are advanced through the leadership role that it plays in the Financial Action Task Force (FATF), the G-7, the G-20, the Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units and, most recently, the counter-financing work stream of the Anti-Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) Coalition.[6]

Canada is a founding member of the FATF and an active participant. The FATF develops international AML/ATF standards, and monitors their effective implementation among the 36 FATF members and the more than 180 countries in the global FATF network through peer reviews and public reporting. The FATF also leads international efforts related to policy development and risk analysis, and identifies and reports on emerging ML/TF trends and methods. This work helps to ensure that countries have the appropriate tools in place to address ML/TF risks. Canada also provides expertise and funding to increase AML/ATF capacity in countries with weaker regimes, including through the Counter-Terrorism Capacity Building Program and the Anti-Crime Capacity Building Program, which are led by DFATD.

The second pillar provides strong measures to prevent individuals from placing illicit proceeds or terrorist-related funds into the financial system, while having correspondingly strong measures to detect the placement and movement of such funds. At the centre of this prevention and detection approach are the reporting entities, specifically the financial institutions and DNFBPs, that are the gatekeepers of the financial system in implementing the various measures under the PCMLTFA, and the regulators, principally FINTRAC and OSFI, which supervise them.

The transparency of corporations and trusts contributes to preventing and detecting money laundering and terrorist financing, including the requirements for financial institutions to identify the beneficial owners of the corporations and trusts with whom they do business. Provincial and federal corporate laws and registries and securities regulation also contribute to preventing and detecting money laundering and terrorist financing in Canada.

The final pillar deals with the investigation and disruption of money laundering and terrorist financing. Regime partners, such as CSIS, the CBSA and the RCMP, supported by FINTRAC's intelligence gathering and analysis activities, undertake financial investigations in relation to money laundering, terrorist financing and other profit-oriented crimes. The CRA also plays an important role in investigating tax evasion and its associated money laundering, and in detecting charities that are at risk and ensuring that they are not being abused to finance terrorism. The PPSC ensures that crimes are prosecuted to the fullest extent of the law.

The restraint and confiscation of proceeds of crime is also an important law enforcement component of the regime. PWGSC manages all seized and restrained property for criminal cases prosecuted by the Government of Canada. The CBSA enforces the Cross-Border Currency Reporting Program, and transmits information from reports and seizures to FINTRAC.

The regime also has a robust terrorist listing process to freeze terrorist assets, pursuant to the Criminal Code and the Regulations Implementing the United Nations Resolutions on the Suppression of Terrorism, which is led by Public Safety Canada and DFATD, respectively. Canada currently has 90 terrorist-related listings under this process.[7]

Canada's AML/ATF regime is reviewed on a regular basis by a variety of bodies to ensure that it operates effectively and is in keeping with its legislative mandate, while respecting the Constitutional division of powers, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and the privacy rights of Canadians.

The Parliament of Canada undertakes a comprehensive review of the PCMLTFA every five years and the Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada is required to conduct a privacy audit of FINTRAC every two years. Among other periodic reports,[8] reviews and audits, the regime's performance is statutorily mandated to be reviewed every five years. Internationally, Canada's regime is assessed by the FATF against its global AML/ATF standards and is subject to the FATF's follow-up process.

The Government announced a series of measures to enhance the AML/ATF regime in its 2014 Economic Action Plan (the budget), which received Royal Assent in June 2014. These legislative and regulatory changes will strengthen customer due diligence requirements, improve compliance, monitoring and enforcement, strengthen information sharing and disclosure, and authorize the Minister of Finance to issue countermeasures against jurisdictions and foreign entities that have weak ML/TF controls. To strengthen Canada's targeted financial sanctions regime, enhancements will also be made to reduce the burden imposed on the private sector to implement financial sanctions.

Canada is committed and engaged, both domestically and internationally, in the fight against money laundering and terrorist financing. The risks are present and evolving. Canada has a strong regime and it is committed to take appropriate action to mitigate the ML/TF risks identified in this assessment and to continue to assess risks on an ongoing basis.

The Government of Canada expects that this report will be used by financial institutions and other reporting entities to contribute to their understanding of how and where they may be most vulnerable and exposed to inherent ML/TF risks. FINTRAC and OSFI will include relevant information related to inherent risks in their respective guidance documentation to assist financial institutions and other reporting entities in integrating such information in their own risk assessment methodology and processes so that they can effectively implement controls to mitigate ML/TF risks. Members of the oversight of the regime will also use the results of the risk assessment to inform policy and operations as part of the ongoing efforts to combat money laundering and terrorist financing.

The Government of Canada has developed an assessment to identify and understand inherent ML/TF risks in Canada, and their relative importance, through a rigorous and systematic analysis of qualitative and quantitative data and expert opinion about money laundering and terrorist financing. The assessment provides the basis to think critically and systematically about ML/TF risks on an ongoing basis, and to promote a common understanding of these risks. This chapter provides an overview of the risk assessment methodology.

The methodology assesses the inherent ML/TF risks, which are the fundamental risks in Canada that are the subject of the broad suite of government and private sector controls and activities to effectively mitigate those risks. Understanding Canada's risk context and the main characteristics that expose sectors and products to inherent ML/TF risks in Canada is important in being able to identify and apply measures to effectively mitigate them.

The basis of the risk assessment is that risk is a function of three components: threats, inherent vulnerabilities and consequences. Furthermore, risk is viewed as a function of the likelihood of threat actors exploiting inherent vulnerabilities to launder illicit proceeds or fund terrorism and the consequences should this occur.

Key Definitions

ML/TF threat: a person or group who has the intention, or may be used as a witting or unwitting facilitator, to launder proceeds of crime or to fund terrorism.

Inherent ML/TF vulnerabilities: the properties in a sector, product, service, distribution channel, customer base, institution, system, structure or jurisdiction that threat actors can exploit to launder proceeds of crime or to fund terrorism.

Consequences of ML/TF: the negative impact that money laundering and terrorist financing has on a society, economy and government.

Likelihood of ML/TF: the likelihood of ML/TF threat actors exploiting inherent vulnerabilities.

The ML threat was assessed separately from the TF threat. Although there is some overlap, the nature of these criminal activities is different, warranting separate assessments. In contrast, the assessment of the ML/TF vulnerabilities did not require such separation since ML/TF threats seek to exploit the same set of vulnerable features and characteristics of products and services offered by sectors to launder proceeds of crime or to fund terrorism.

As a first step, the core components of the ML/TF threats and inherent vulnerabilities were identified and categorized. For these categories, criteria were developed to rate the extent of the ML/TF threats and the inherent ML/TF vulnerabilities. These ratings were then used to assess the likelihood of money laundering and terrorist financing, which involved matching the threats with the inherent vulnerabilities, while considering the consequences of money laundering and terrorist financing, which then resulted in the assessment of inherent ML/TF risks. The important types of economic, social and political consequences of money laundering and terrorist financing are identified in the annex.

During a series of workshops, experts from Canada's AML/ATF regime used their expertise and knowledge to assess the ML/TF threats and inherent vulnerabilities of sectors and products using the rating criteria set out in the methodology. In addition, the experts harnessed the regime's store of information, data and analysis to rate each threat and vulnerability. Experts provided ratings of low, medium, high or very high using the defined rating criteria to assess the range of threats and inherent vulnerabilities. The individual ratings were then aggregated to arrive at an overall rating.

The ML threat in Canada was assessed for 21 criminal activities that are most associated with generating proceeds of crime in Canada as well as the threat from third-party money laundering. The ML threat was rated for each criminal activity against four rating criteria: the extent of the threat actors' knowledge, skills and expertise to conduct money laundering; the extent of the threat actors' network, resources and overall capability to conduct money laundering; the scope and complexity of the ML activity; and the magnitude of the proceeds of crime being generated annually from the criminal activity. The ML threat rating results are presented in Chapter 3.

The TF threat in Canada was assessed for 10 terrorist groups as well as for foreign fighters, defined as those who travel abroad to support and fight alongside terrorist groups. The TF threat of these groups was assessed against six rating criteria: the extent of the threat actors' knowledge, skills and expertise to conduct terrorist financing; the extent of the threat actors' network, resources and overall capability to perform TF operations; the scope and global reach of their TF operations; the estimated value of their fundraising activities annually in Canada; the extent of the diversification of their methods to collect, aggregate, transfer and use funds; and the extent to which the funds may be used against Canadian domestic and international interests. The TF threat rating results are presented in Chapter 4.

The assessment considered the inherent features of Canada that may be exploited by threat actors for illicit purposes (e.g., geography, economy, demographics). Against this, the inherent ML/TF vulnerabilities were assessed for 27 economic sectors and products. The areas were assessed against five rating criteria: the inherent characteristics of the assessed areas (size, complexity, accessibility and integration); the nature and extent of the vulnerable products and services; the business relationship with its clients; geographic reach (extent of activity with high-risk jurisdictions and locations of concern); and the degree of anonymity and complexity afforded by the delivery channels. Canada's inherent features and sector and product vulnerability assessment results are presented in Chapter 5.

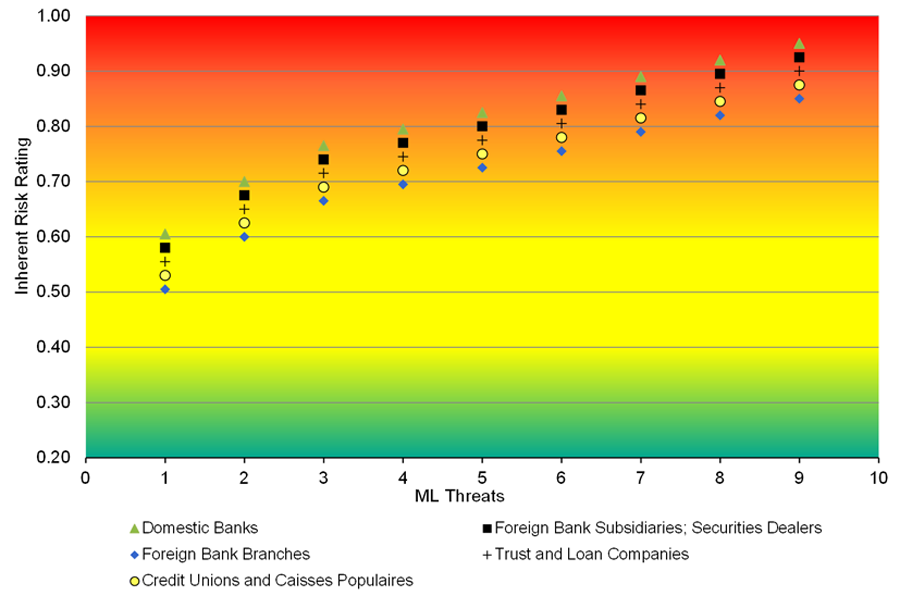

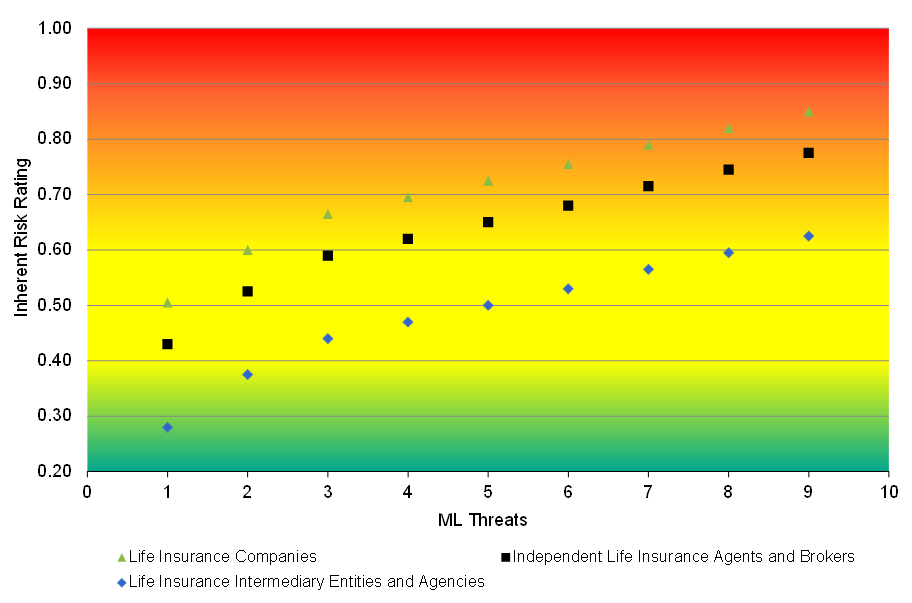

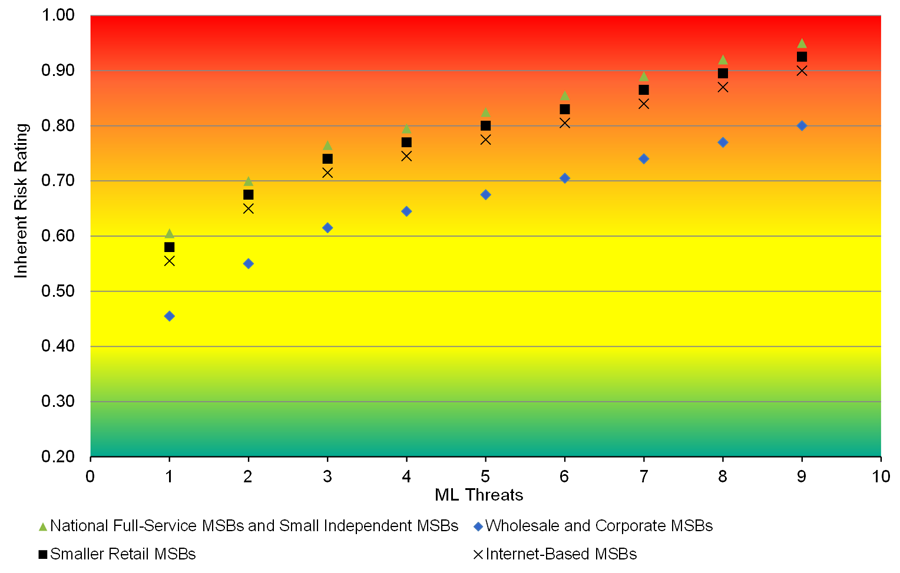

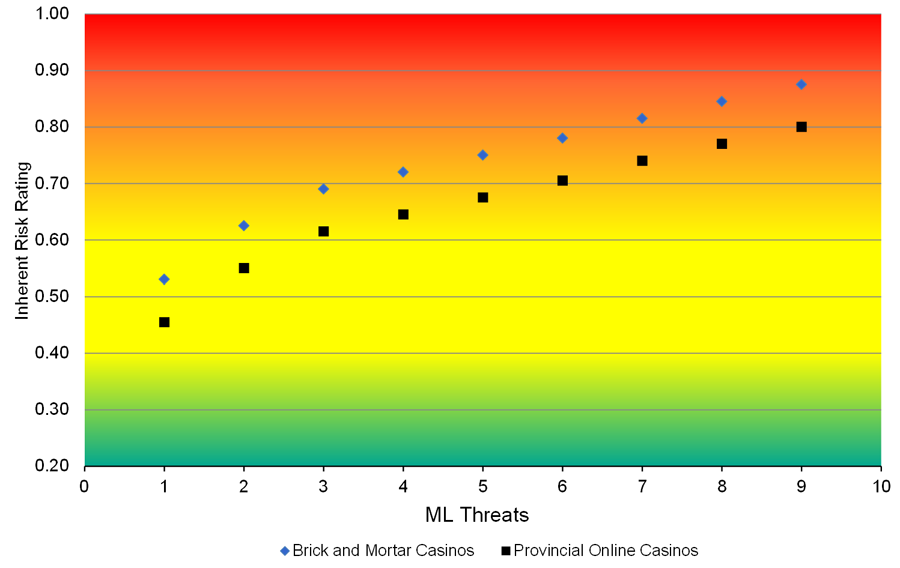

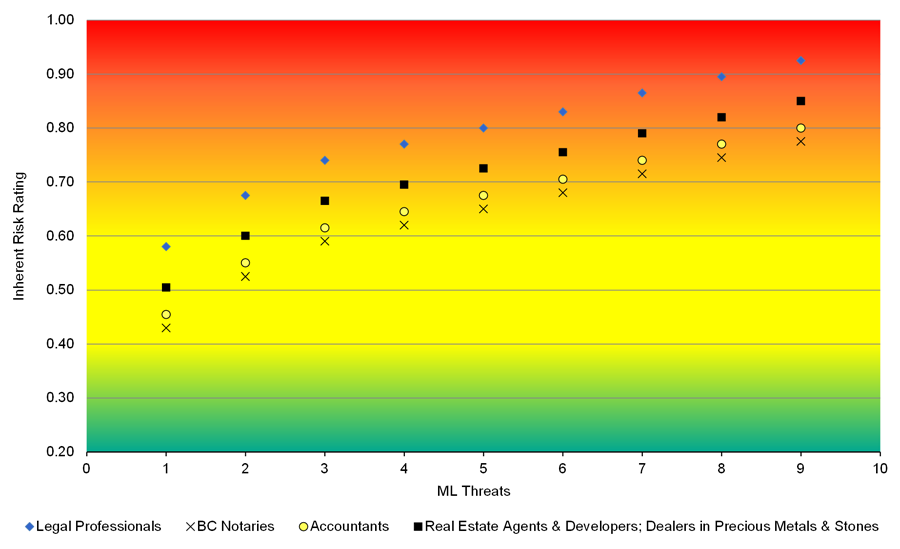

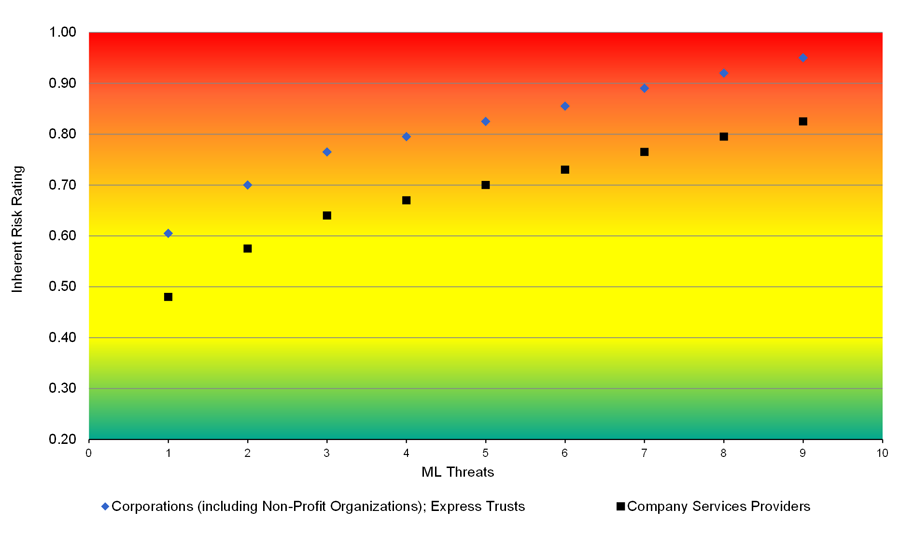

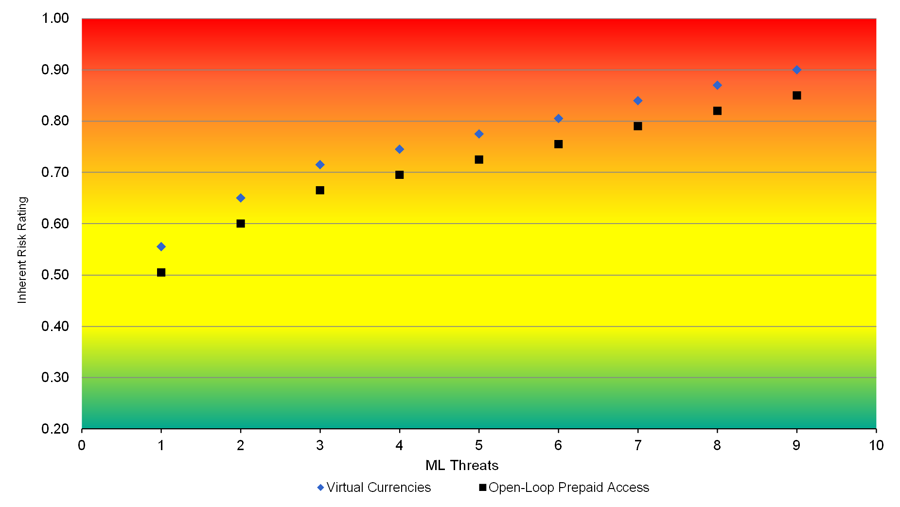

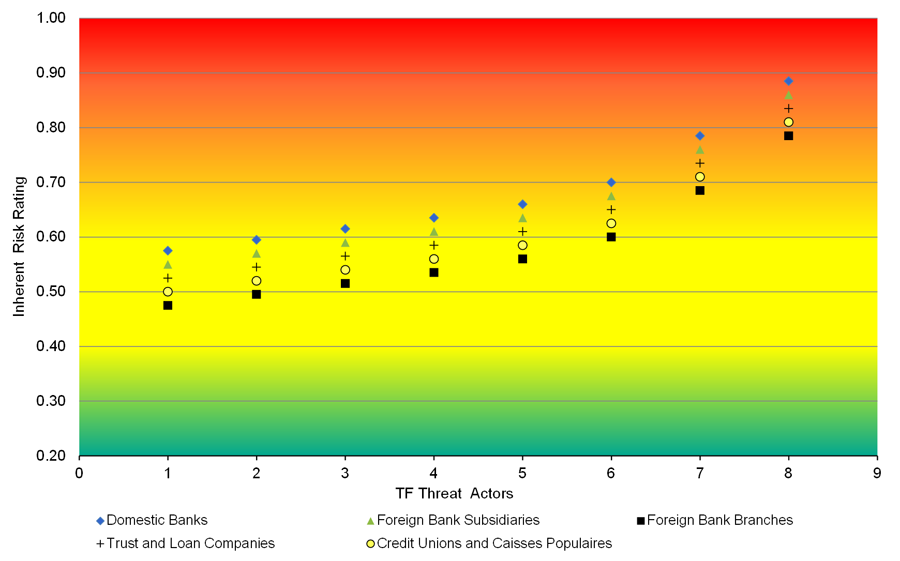

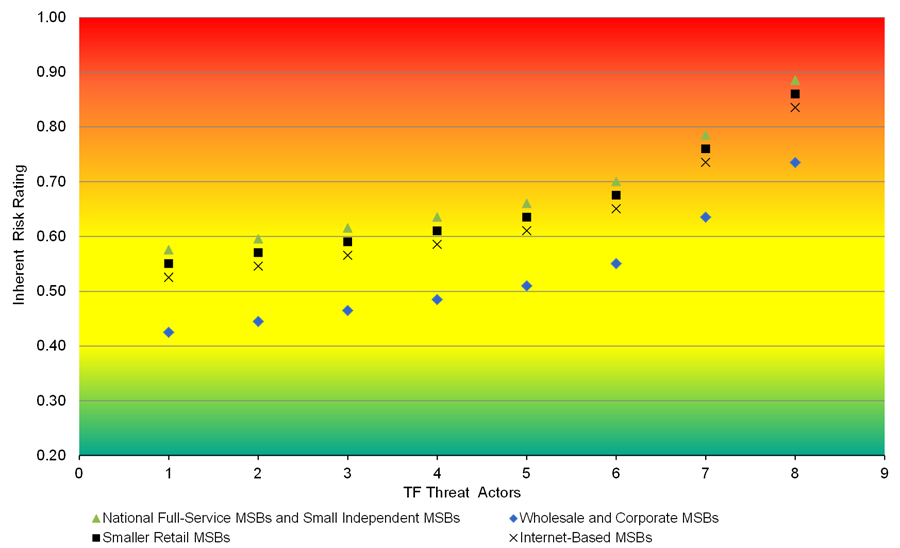

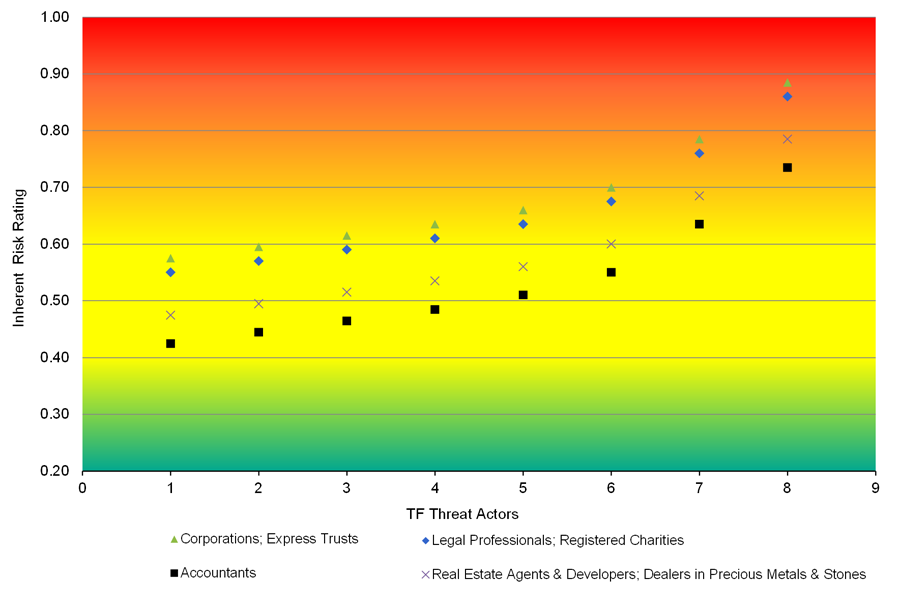

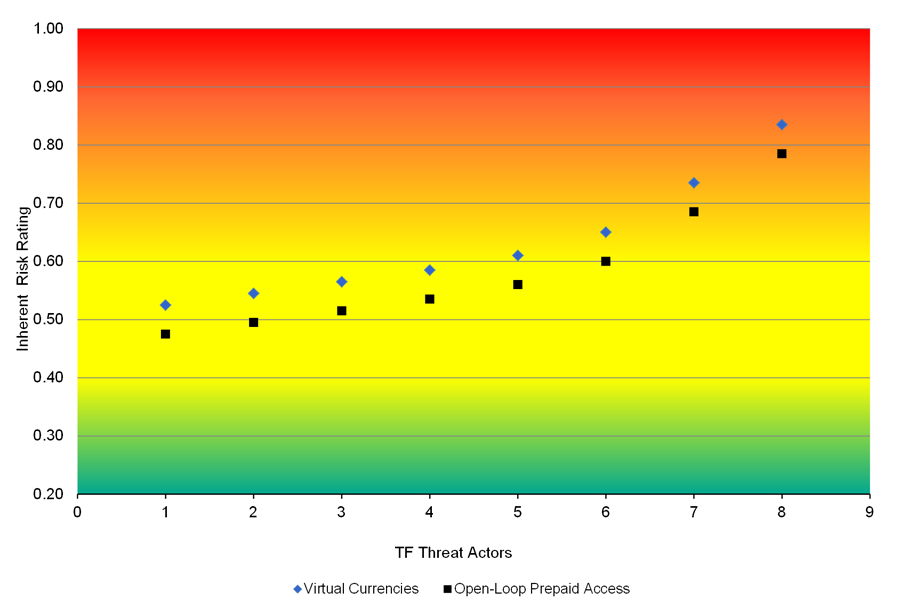

The inherent ML/TF risks were assessed based on the likelihood of money laundering or terrorist financing occurring while considering the consequences of such events. The likelihood of the money laundering or terrorist financing was assessed by matching the ML/TF threats with the inherently vulnerable sectors and products through the ML/TF methods and techniques that are used by threat actors to exploit these sectors and products. Inherent ML/TF risk scenarios were created from these judgements and used to plot the inherent risk results by sector, product or service in a number of illustrative charts. This presentation allows one to compare the different levels of exposure of various sectors and products to inherent ML/TF risks in Canada.[9] The results are presented in Chapter 6.

The inherent risk assessment and its methodology should be viewed as one core element of a larger framework to support an ongoing process to identify, assess and mitigate ML/TF risks in Canada. This framework is summarized below in Chart 2.

Chart 2

Canada's ML/TF Risk Assessment Framework

The ML threat assessment indicates that there is a broad range of profit-oriented crime conducted by a variety of threat actors in Canada. This criminal activity generates billions of dollars in proceeds of crime annually that might be laundered.

Threat actors who perpetrate profit-oriented crime in Canada range from unsophisticated, criminally inclined individuals, including petty criminals and street gang members, to criminalized professionals[10] and organized crime groups (OCGs).[11] According to the Criminal Intelligence Service Canada, there are over 650 OCGs operating in Canada. Of these threat actors, transnational OCGs are the most threatening both in terms of generating the most proceeds of crime and in the intensity of efforts to launder the proceeds. The most powerful transnational OCGs in Canada, consisting of factions with ties to Italy and Asia, and certain Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs, are involved in multiple lines of profit-oriented crime and have the infrastructure and network to launder large amounts of proceeds of crime on an ongoing basis through multiple sectors using a diverse set of methods to avoid detection and disruption. These OCGs have strong networks and strategic relationships with other criminal organizations domestically and internationally (e.g., Mexican and Columbian drug cartels).

Transnational OCGs appear to frequently rely on professional money launderers to establish and administer schemes to launder the proceeds emanating from their criminal activities. Large-scale, sophisticated ML operations rarely take place in Canada without the employ of professional money launderers. The nexus between transnational OCGs and professional money launderers is a key ML threat in Canada. In addition to professional money launderers, unwitting and witting facilitators appear to play a key role in supporting the perpetration of profit-oriented crime and the laundering of criminal proceeds. The corruption of individuals and the infiltration of private and public institutions is also a notable concern as it establishes the conditions to foster money laundering and other criminal activity.

The conduct of larger-scale profit-oriented crime often has a significant international dimension and tends to be supported by transnational distribution networks. These networks exhibit a high level of sophistication and capability in moving illicit goods into (destination), out of (source) or through (transit) Canada, including stolen goods, counterfeit products, illicit drugs, illicit firearms, wildlife and people. Mapped against this sophisticated illicit global supply chain appears to be a correspondingly sophisticated flow of illicit funds and a network to launder these funds. Some threat actors appear to have the sophistication and capability to exploit the global trade and financial systems to clandestinely deal in the transnational trafficking of illicit goods and launder the illicit proceeds. This capability includes having criminal associates in legitimate positions of employment in ports of entry, or controlling employees using methods like bribery, blackmail or extortion, in order to have insiders to facilitate the movement of illicit goods and proceeds into and out of Canada. These threat actors also appear to have the ability to exploit the AML/ATF weaknesses of foreign countries or situations of unrest or conflicts occurring in foreign countries to facilitate money laundering and other criminal activities.

Experts assessed the ML threat for 21 profit-oriented crimes and third-party money laundering using the following criteria:

- Sophistication: the extent to which the threat actors have the knowledge, skills and expertise to launder criminal proceeds and avoid detection by authorities.

- Capability: the extent to which the threat actors have the resources and network to launder criminal proceeds (e.g., access to facilitators, links to organized crime).

- Scope: the extent to which threat actors are using financial institutions, DNFBPs and other sectors to launder criminal proceeds.

- Proceeds of Crime: the magnitude of the estimated dollar value of the proceeds of crime being generated annually from the profit-oriented crime.

As presented in Table 1, eight profit-oriented crimes and third-party money laundering were rated as a very high ML threat, eight were rated high, four were rated medium and one was rated low.

Table 1

Overall Money Laundering Threat Rating Results

Very High Threat Rating

Capital Markets Fraud

Mass Marketing Fraud

Commercial (Trade) Fraud

Mortgage Fraud

Corruption and Bribery

Third-Party Money Laundering

Counterfeiting and Piracy

Tobacco Smuggling and Trafficking

Illicit Drug Trafficking

High Threat Rating

Currency Counterfeiting

Illegal Gambling

Human Smuggling

Payment Card Fraud

Human Trafficking

Pollution Crime

Identity Theft and Fraud

Robbery and Theft

Medium Threat Rating

Firearms Smuggling and Trafficking

Loan Sharking

Extortion

Tax Evasion/Tax Fraud

Low Threat Rating

Wildlife Crime

ML Threat from Capital Markets Fraud: Securities fraud, including investment misrepresentation and other forms of capital markets fraud-related misconduct, such as illegal insider trading and market manipulation, occurs in Canada. Over one-quarter of Canadians believe that they have been approached with a possible fraudulent investment opportunity.[12] Although it is challenging to be definitive on the actual amount of reported losses, capital markets fraud is a rich source of proceeds of crime. For instance, in 2009, two Canadians were arrested and charged with fraud, theft and money laundering for orchestrating a Ponzi-style investment fraud that resulted in defrauding about 2,000 investors of between $100 million and $200 million. Most of the large-scale securities frauds in Canada have been perpetrated by criminalized professionals, who have (or purport to have) professional credentials and financial expertise. Perpetrating capital markets fraud, especially the larger, more elaborate national and international schemes (such as Ponzi schemes), requires significant knowledge and expertise and, often, access to a network of witting or unwitting facilitators to help orchestrate and perpetrate the fraud. Alongside the sophisticated fraudulent schemes, there are sophisticated ML schemes designed to integrate and legitimize the fraud-related proceeds into the financial system. ML schemes in this context would involve a range of sectors and methods, including shell or front companies, electronic funds transfers (EFTs), structuring and/or smurfing deposits[13] and nominees[14].

ML Threat from Commercial (Trade) Fraud: The transnational OCGs and the terrorist actors and networks that generate the most illicit proceeds from commercial fraud are very sophisticated and capable, with the knowledge, expertise and international relationships to manipulate multiple trade chains and trade financing vehicles, often operating under the cover of front and/or legitimate companies. The sophistication and capability in terms of conducting the commercial fraud also extends to laundering its proceeds. The threat actors in this space appear to use multiple sectors in Canada and internationally to launder the proceeds. Actors are also suspected to use domestic and foreign front and shell companies, to commingle illicit funds within legitimate businesses (both cash and non-cash intensive businesses), and to use third-party money launderers, including professional money launderers. In one Canadian case, border agents detected a scheme that appeared to involve trade fraud and trade-based money laundering. Under this scheme, a criminal organization allegedly manipulated shipping documents and engaged in fraudulent transactions to overbill (invoice) a colluding foreign importer for a commodity. Once imported, the foreign importer would pay the exporter the inflated amount, consisting of the legitimate proceeds from the sale of the commodity and illicit proceeds.

ML Threat from Corruption and Bribery: Corruption and bribery in Canada comes in many different forms, ranging from small-scale bribe-paying activity to obtain an advantage or benefit to large-scale schemes aimed at illegally obtaining lucrative public contracts. The ML threat from corruption and bribery is rated very high principally due to the size of the public procurement sector and the opportunities that this presents to illegally obtain high-value contracts. In addition to corrupt activities carried out domestically, some Canadian companies have also been implicated in the paying of bribes to foreign officials to advance their company's business interests. OCGs that have the ability to infiltrate the public procurement process have the sophistication and capability to launder large amounts of illicit funds, using a variety of ML sectors and methods, including banks, money services businesses (MSBs), high-end goods, investments and front companies. Lawyers, accountants, professional money launderers and public officials may also be used to facilitate the laundering of corruption-related proceeds.

ML Threat from Counterfeiting and Piracy: The prevalence of counterfeit and pirated products in Canada has grown significantly over the past decade, in terms of both the amount and the selection of products available for sale. China is the primary source of counterfeit products imported into Canada. Toronto, Montreal and Vancouver are the key entry points for these products. OCGs appear to have established links and have tapped into global illicit distribution channels, allowing them to bring increasingly more counterfeit products into Canada. Given the sophistication and capability needed for counterfeiting operations, actors involved in these operations appear to be highly sophisticated and capable in terms of laundering the proceeds from counterfeit goods. Having the sophistication and capability to transfer funds in a clandestine way domestically and internationally would appear to be fundamental to the sustainability of the operations given the large numbers of individuals that expect payment throughout the supply chain. All indications suggest that the counterfeit and pirated goods market is substantial and continues to grow rapidly in Canada.

ML Threat from Illicit Drug Trafficking: The illicit drug market is the largest criminal market in Canada, with cannabis, cocaine, amphetamine-type stimulants and heroin comprising a significant share of this market. Although numerous threat actors engage in drug trafficking, transnational OCGs are the most threatening and are the most powerful actor in this market. Transnational OCGs exhibit a very high level of sophistication, capability and scope in their ML activities. They are often connected to other OCGs, and multiple organized networks at both the domestic and international levels, to launder drug-related proceeds. OCGs also have access to professional money launderers and facilitators (such as money mules[15] and nominees), and often have control over a number of companies (front and/or legitimate) as part of their ML operations. OCGs use a large number of ML methods, including the use of multiple sectors, commingling of illicit funds within legitimate businesses, domestic and foreign front and shell companies, bulk cash smuggling, trade-based money laundering, virtual currencies and prepaid cards.

ML Threat from Mass Marketing Fraud (MMF): MMF is very prevalent in Canada and the scams associated with MMF have been growing in frequency and sophistication over time. Toronto, Montreal, Vancouver, Calgary and Edmonton are considered to be main bases of operation for MMF schemes. Common types of scams in Canada include service scams, prize scams and extortion scams. In March 2014, law enforcement arrested 23 individuals in Montreal in connection with allegedly orchestrating a telemarketing scheme. The scheme defrauded thousands of victims, mostly senior citizens, of at least $16 million.The majority of MMF connected to Canada is carried out by OCGs, which use a range of ML methods and sectors, including smurfing, structuring, the use of nominees and money mules, shell companies, MSBs, the informal banking system and front companies. Although reported losses averaged about $60 million annually from 2009 to 2013 and totalled $73 million in 2014,[16] the actual losses are viewed as being much higher, in the hundreds of millions of dollars annually, given that MMF is generally under-reported by victims.

ML Threat from Mortgage Fraud: Mortgage fraud occurs across Canada, but it is most prevalent in large urban areas in Quebec, Ontario, Alberta and British Columbia. Mortgage fraud schemes are often undertaken to facilitate another criminal activity (e.g., illicit drug production and distribution, money laundering) or directly for profit. OCGs conduct the vast majority of mortgage fraud in Canada. To carry out this crime, OCGs are believed to rely on the assistance of witting or unwitting professionals in the real estate sector, including agents, brokers, appraisers and lawyers. OCGs frequently use straw buyers to orchestrate the mortgage fraud. OCGs conducting mortgage fraud schemes are, for the most part, suspected to be highly sophisticated and capable in terms of the associated ML activity. Professional money launderers have been used to launder mortgage fraud-related proceeds. It is suspected that criminally inclined real estate professionals, notably real estate lawyers, are used to facilitate money laundering. OCGs involved in mortgage fraud appear to launder funds through banks, MSBs, legitimate businesses and trust accounts. Victims of mortgage fraud, which can include Canadian homeowners and lending institutions, can incur significant financial losses.

ML Threat from Third-Party Money Laundering: Large-scale and sophisticated ML operations in Canada, notably those connected to transnational OCGs, frequently involve third-party money launderers, namely professional money launderers, nominees or money mules. Of the three, professional money launderers pose the greatest threat both in terms of laundering domestically generated proceeds of crime as well as laundering foreign-generated proceeds through Canada (and through its financial institutions). Professional money launderers specialize in laundering proceeds of crime and generally offer their services to criminals for a fee. These individuals are in the business of laundering large sums of money and by their very nature have the sophistication and capability to support complex, sustainable and long-term ML operations. As a group, they use many different methods and techniques, sometimes within the same scheme, to launder money that is challenging to detect. The professional money launderers are of principal concern since they are often the masterminds behind large-scale ML schemes and are frequently used by the most powerful transnational OCGs in Canada. Nominees and money mules are less of a threat, but nonetheless important because they may be critical in carrying out or facilitating ML schemes, both large and small.

ML Threat from Tobacco Smuggling and Trafficking: The largest quantity of illicit tobacco found in Canada originates from the manufacturing operations based on Aboriginal reserves that straddle Quebec, Ontario and New York State. Given the profitable nature of the illicit tobacco trade, there is significant organized crime involvement in the smuggling and trafficking of illicit tobacco across the Canada-U.S. border. The OCGs involved in the illicit tobacco trade are some of the most sophisticated and threatening in Canada. These OCGs have the sophistication and capability to use a variety of sectors and methods (e.g., commingling, structuring, smurfing and refining) to launder the large amount of cash proceeds that are generated from the illicit tobacco smuggling and trafficking. In addition to the proceeds of crime generated from the reserve-manufactured illicit tobacco trade, proceeds of crime are generated from counterfeit cigarettes imported from overseas (primarily from China); cigarettes produced legally in Canada, the United States or abroad, and sold tax-free; and "fine cut" tobacco imported illegally, mostly by Canadian-based manufacturers.

ML Threat from Currency Counterfeiting: The large-scale production of Canadian counterfeit currency is primarily undertaken by OCGs. OCGs generally conduct currency counterfeiting alongside other profit-oriented criminal activities. OCGs that produce and distribute high-quality counterfeit currency are suspected to exhibit a high level of sophistication and capability in terms of the methods used to launder the proceeds arising from currency counterfeiting. They appear to have the network and infrastructure in place to successfully launder, through a number of sectors, predominantly cash proceeds arising not only from currency counterfeiting but also from their other criminal activities.

ML Threat from Human Smuggling: Canada is a target for increasingly sophisticated global human smuggling networks. Human smuggling is believed to be carried out primarily by a small number of OCGs that are well-established, having developed the sophistication and capability to smuggle humans for profit across multiple borders, which requires a high-degree of organization, planning and international connections. OCGs in this space are suspected to be very sophisticated and capable in terms of laundering the proceeds of crime arising from human smuggling. A review of suspected ML cases largely related to human smuggling indicates that OCGs may use a variety of sectors and methods to launder the proceeds, including front companies, legitimate businesses, banks, MSBs and casinos.

ML Threat from Human Trafficking: Canada is primarily a destination country for human trafficking, and domestic human trafficking for sexual exploitation is the most common form of human trafficking in Canada.[17] Sex trafficking is largely perpetrated by criminally inclined individuals, who recruit and traffic domestically and, to a lesser extent, OCGs, some of which only recruit and traffic domestically, while others recruit and traffic domestically and internationally. Criminally inclined individuals are not believed to exhibit any real levels of sophistication or capability in terms of laundering their sex trafficking-related proceeds. It is suspected that most of their activity would centre on laundering mostly cash proceeds for immediate personal use, leveraging a very limited or non-existent network, and using a limited number of sectors and methods. The OCGs that conduct sex trafficking and generate significant proceeds are suspected to use established ML infrastructure to launder the proceeds. Some OCGs, although less sophisticated in terms of money laundering, are nonetheless more capable because they may have access to venues to facilitate money laundering (e.g., strip clubs and massage parlors) as well as victims that can be used as nominees for deposits and wire transfers.

ML Threat from Identity Theft and Fraud ("Identity Crime"): Identity crime is prevalent in Canada and it is a concern given that stolen identities are often used to support the conduct of other criminal activities. The OCGs conducting identity crime are well-established and resilient, and have well-developed domestic and international networks. They are also associated with drug trafficking, human smuggling and counterfeiting currency. It is suspected that these OCGs use multiple methods and sectors to launder the funds. Identity crime itself can support money laundering by providing individuals with fake credentials to subvert customer due diligence safeguards. In 2014, Canadians reported over $10 million in losses to identity crime.[18] It is important to note that identity crime also facilitates the conduct of other criminal activities that generate significant proceeds of crime.

ML Threat from Illegal Gambling: Illegal gambling in Canada consists of private betting or gaming houses, unregulated video gaming and lottery machines, and unregulated online gambling. Organized crime is the major provider of illegal gambling opportunities in Canada, although there are some smaller operators. The illegal gambling market appears to be small in terms of the numbers of threat actors involved, but it is suspected to be highly profitable for those involved in it. OCGs conduct these activities in a sophisticated manner. For traditional bookmaking betting activities, OCGs use pyramid-style schemes to protect more senior members of the pyramid. Bookmakers will only accept cash to benefit from its anonymity. For online gambling, OCGs have based the network servers to run illegal gambling sites in jurisdictions where online gambling is legal. It is assumed that the OCGs operating in this space have the capability to use a variety of sectors and methods to launder the proceeds of crime. The main forms of illegal gambling proceeds are cash and possibly high value goods (in instances where gamblers may have run out of cash).

ML Threat from Payment Card Fraud: In Canada, credit card fraud has increased significantly over the last five years while debit card fraud has decreased significantly over that period. "Card not present" fraud comprises the largest value of all categories of credit card fraud in Canada followed by credit card counterfeiting.[19] As with other frauds, OCGs are heavily involved in payment card fraud. Organized crime involvement in payment card fraud can involve card thefts, fraudulent card applications, fake deposits, skimming or card-not-present fraud. Most OCGs in this space are sophisticated and have specialized technological knowledge. OCGs that operate payment card theft networks are suspected to, in large part, exhibit very high levels of sophistication and capability in terms of laundering the payment card fraud-related proceeds. Multiple sectors are suspected to be used to launder payment card-related proceeds, including financial institutions, MSBs and casinos, as well as multiple methods, including structuring bank deposits, smurfing, front companies and the use of nominees and money mules. In 2013, Canadians reported close to $500 million in payment card fraud-related losses.[20]

ML Threat from Pollution Crime: Pollution crime in Canada comes in a variety of forms and is principally undertaken by OCGs, companies and individuals. Of the forms taken, there is particular concern that OCGs have infiltrated the waste management sector, as owning waste management companies can be an effective vehicle to generate illicit profits, by dumping waste illegally, and to launder proceeds from other criminal activities. OCGs may also be involved in the trafficking of electronic waste and in the importation of counterfeit products that do not meet Canada's environmental standards (e.g., counterfeit engines). Finally, some private and public companies may be using deceptive practices to undermine emissions schemes and may be dumping or using third parties to dump waste illegally. Given the sophisticated nature of activities and operations, it is assumed that there is a great degree of sophistication, capability and scope in terms of being able to launder the proceeds arising from pollution-related crime. In the case of waste management, the OCGs appear to demonstrate a very high degree of sophistication and capability to operate waste management businesses in a manner that generates illegal profit and is used for money laundering.

ML Threat from Robbery and Theft: Smaller-scale thefts and robberies are most frequently carried out by opportunistic individuals and petty thieves, while larger-scale thefts and robberies are more frequently associated with OCGs, which are heavily involved in motor vehicle, heavy equipment and cargo theft. The most sophisticated and capable tend to be the OCGs that have well-established auto theft networks in Canada, which are used to supply foreign markets with stolen Canadian vehicles. The OCGs that have established auto theft networks in Canada are also suspected to be highly sophisticated and capable from a ML perspective. It is believed that these OCGs use a range of trade-based fraud and related ML techniques to disguise the illicit origin of the automobiles as well as a range of methods to move the proceeds back into Canada, including bulk cash smuggling and EFTs. Front companies, shell companies and nominees may be used to obscure the flow of funds back to Canada arising from the illicit sales in other countries. Professional money launderers may be utilized to mastermind ML schemes given the large amounts of proceeds generated by these networks and the challenges of laundering proceeds that are generated across multiple jurisdictions.

ML Threat from Firearms Smuggling and Trafficking: The illicit firearms market in Canada appears to be dominated by unsophisticated, criminally inclined individuals and OCGs (primarily street gangs operating in metropolitan areas) as well as a small number of sophisticated OCGs. Very few OCGs are involved in the trafficking or smuggling of firearms for the purpose of achieving large profits. Instead, OCGs mainly use firearms to strengthen their position within other criminal markets, such as the illicit drugs market. While the majority of guns recovered in crime in Canada are believed to be domestically sourced, a majority of successfully traced handguns are smuggled into Canada from abroad, mostly from the United States. OCGs may sell illicit firearms to other OCGs and criminally inclined individuals, although it is unclear how important these OCGs are in terms of acting as a general supply hub for illicit firearms in Canada. These OCGs may use their established ML infrastructure to launder the proceeds arising from their firearms trafficking activities, which generally focus on exploiting a number of different sectors using a variety of methods.

ML Threat from Extortion: Over 2,000 incidents of extortion in Canada were reported to police in 2013.[21] Extortion is often conducted in conjunction with or in furtherance of other crimes, such as drug trafficking, illegal gambling and humantrafficking. Some OCGs systematically use extortion as a tool to obtain money and property in exchange for the protection of certain businesses; to control the distribution of illicit drugs; to force the payment of illegal gambling debts; or to gain access to ports of entry. Some terrorist groups have been known to use extortion to gain power over individuals to further their objectives, including by extorting funds from diaspora communities in Canada. The OCGs and terrorist groups in this space vary in their levels of sophistication, capability and scope for laundering extortion-related proceeds or raising funds to support terrorism. Structuring and smurfing, the commingling of illicit funds and casino refining activities may be used to launder proceeds of extortion.

ML Threat from Loan Sharking: Loan sharks in Canada appear to target low-income individuals, problem gamblers, illicit drug seekers and cash-strapped entrepreneurs. Conducting loan sharking activities requires working capital, financial aptitude and a capacity to enforce debt collection. As this is a unique skill set, loan sharking activity appears to be undertaken by a small number of the more sophisticated OCGs in Canada as well as by a small number of independent operators. OCGs and independent operators conducting this criminal activity are suspected to exhibit a relatively high level of sophistication and capability in terms of being able to launder the proceeds emanating from illicit loans. Some cases indicate that loan sharks use a variety of ML methods to launder their proceeds, including through casinos and financial institutions as well as through the real estate and construction sectors.

ML Threat from Tax Evasion/Tax Fraud (hereafter referred to as tax evasion): Tax evasion is carried out in many different forms in Canada, with the ultimate objective of underpaying or evading the payment of taxes owing or to unlawfully claim refunds or credits. Tax evasion is frequently carried out by opportunistic individuals, commonly using relatively unsophisticated techniques to evade taxes, such as falsifying or fabricating documentation to misrepresent their tax situation. To facilitate tax evasion, unscrupulous tax preparers have been known to provide counsel on how to evade taxes or obtain fraudulent refunds using a variety of different techniques. Tax evasion is also conducted by professional criminals, including OCGs, who may orchestrate tax evasion schemes (e.g., duty or tax refund fraud). Since tax evasion generally involves ordinary individuals using tax evasion techniques of low sophistication, the ensuing money laundering is also believed to be unsophisticated. In cases of large (or multiple) refunds that have been generated by sophisticated tax evasion schemes, more sophisticated ML techniques may be observed.

ML Threat from Wildlife Crime: There is an established illicit market for certain types of Canadian species, including narwhal tusks, polar bear hides, peregrine falcon eggs and wild ginseng. Black market prices for certain Canadian species are high and have risen significantly over the last five years. Wildlife crime in Canada appears to be largely conducted by opportunistic, criminally inclined individuals. Individuals conducting wildlife crime are suspected to exhibit low levels of sophistication, capability and scope in terms of laundering wildlife crime-related proceeds. The proceeds tend to be fairly modest (with some exceptions) and the laundering activity appears to be focused on immediately placing or integrating the proceeds for personal use, and limited to one sector.

Terrorism is the leading threat to Canada's national security.[22] Countering terrorism, including its financing, at home and abroad is a key priority for the Government of Canada.

Canada has listed 54 terrorist entities under its Criminal Code and 36 terrorist entities under the Regulations Implementing the United Nations Resolutions on the Suppression of Terrorism. [23] The majority of these entities are based in foreign countries, mainly in Africa, Asia and the Middle East.[24] Members or supporters/sympathizers of some of these listed entities have been present in Canada at one point or another. Their activities have often focused on providing financial or material support to terrorist entities based in foreign countries. Although their focus has been more on terrorist financing and less on conducting terrorist attacks in Canada, Canada is not immune to such attacks and, over the years, a few attacks have been carried out while others have been thwarted. Canadian interests[25] have also been affected by terrorism-related incidents that have occurred abroad.

Not all 90 listed terrorist entities pose a TF threat to Canada since not all of these entities have financing or support networks in Canada. Consequently, an entity posing a terrorist threat to Canada does not necessarily pose a TF threat to Canada, or if so, the level of threat may not be the same. On the one hand, some terrorist groups and associated individuals pose a significant terrorist attack threat to Canada at home and abroad, while the TF threat in Canada is lower. On the other hand, some entities pose a very high or high TF threat but a lower terrorist attack threat to Canada.[26]

A number of TF methods have been used in Canada and have involved both financial and material support for terrorism, including the payment of travel expenses and the procurement of goods.[27] The transfer of suspected terrorist funds to international locations has been conducted through a number of methods including the use of MSBs, banks and non-profit organizations (NPOs) as well as smuggling bulk cash across borders. Based on open source and other available reporting on the potential for Canadians to send money or goods abroad to fund terrorism, the following countries were assessed to be the most likely locations where such funds or goods would be received: Afghanistan, Egypt, India, Lebanon, Pakistan, Palestinian Territories, Somalia, Sri Lanka, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates and Yemen.

After a thorough review of publicly available and classified information related to terrorist groups with a Canadian nexus, the TF threat posed by actors associated with 10 terrorist groups and foreign fighters was assessed (see Table 2 below).

Table 2

Terrorist Financing Threat Groups of Actors

Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula

Al Qaeda Core

Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb

Al Shabaab

Hamas

Foreign Fighters/Extremist Travellers

Hizballah

Islamic State of Iraq and Syria

Jabhat Al-Nusra

Khalistani Extremist Groups

Remnants of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam

Experts used the following six rating criteria to assess the TF threat posed by the actors associated with these groups and operating in Canada:

- Sophistication:the extent of the threat actors' knowledge, skills and expertise to conduct sustainable, long-term and large-scale TF operations in Canada without being detected by authorities.

- Capability:the extent of the threat actors' network, resources and overall capability to conduct TF operations in Canada.

- Scope of Terrorist Financing: the extent to which the threat actors have a network of supporters and sympathizers within Canada and globally.

- Estimated Fundraising: the estimated value of their TF activities in Canada.

- Diversification of Methods: the diversity and complexity of TF methods related to the collection, aggregation, transfer and use of funds in Canada.

- Suspected Use of Funds: the extent to which funds raised in Canada or overseas by terrorist actors are suspected to be used against Canadian interests in Canada or overseas.

Using these rating criteria and currently available intelligence, the terrorist groups listed in Table 2 were assessed as posing a low, medium or high TF threat in Canada. Further information on some of these groups and their financing networks in Canada is provided below.

Most of the global fundraising networks of Al Qaeda Core and affiliated groups such as Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP), Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) (formerly Al Qaeda in Iraq) and Jabhat Al-Nusra (an AQIM splinter group) mainly operate in the Middle East. For example, ISIS[28] has been reported to use a range of methods to finance its activities that have been conducted in the territory it occupies in the Middle East. Consequently, fundraising activity by Al Qaeda and affiliated groups in Canada is usually conducted by a handful of individuals using legitimate and illegitimate means, and the TF methods are usually simple and limited.

Al Shabaab is a Sunni militant Islamist group aiming to create an Islamist state in Somalia, expel all foreign forces, overthrow the federal government of Somalia and purge the country of any practices it considers un-Islamic. The group also subscribes to the ideology of transnational jihad espoused by Al Qaeda. Al Shabaab has a diversified global fundraising network, although most of its funds come from the area it controls. For example, in East Africa and particularly in Somalia, it exhibits a certain level of sophistication and capability to raise funds, and a significant amount of funding comes from leveraging the area that is under its control and influence. In addition, Al Shabaab has some financing networks in Canada, and fundraising techniques observed in the United States and some Scandinavian countries have also been used in Canada.

More attention has been given in recent years by Canada and other countries to individuals referred to as "foreign fighters" or "extremist travellers" who have travelled to other countries to participate in terrorism-related activities. As of early 2014, the Government of Canada was aware of more than 130 individuals with Canadian connections who were abroad and who were suspected of terrorism-related activities, which included involvement in training, fundraising, promoting radical views and planning terrorist violence. These foreign fighters are frequently self-funded or have raised funds from friends and family, and have participated or currently participate in conflicts such as those in Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia and Syria. Foreign fighters may deplete and close bank accounts and max out credit cards prior to travelling abroad. A number of those individuals remain abroad, some have returned to Canada and others are presumed dead.[29] Foreign fighters returning to Canada[30] may encourage and recruit aspiring violent extremists in Canada, may engage in fundraising activities, or may even plan and carry out terrorist attacks in Canada.

Hamas, which is an abbreviation of Harakat al-Muqawama al-Islamiyya (Islamic Resistance Movement), is a militant Sunni Islamist organization that emerged from the Palestinian branch of the Muslim Brotherhood in late 1987. Hamas operates predominantly in the Gaza and the West Bank and manages a broad, mostly Gaza-based network of "Dawa" or ministry activities that includes charities, schools, clinics, youth camps, fundraising and political activities.

Globally, Hamas is a complex and highly organized group that is well-funded, utilizing a number of financing strategies. Hamas's global network of support is largely based outside of Canada, but there are small groups of Hamas supporters across Canada.

Hizballah, a populist Lebanon-based terrorist organization seeking to represent the Shi'a people and Shi'a Islamism, is highly disciplined and sophisticated, with extensive paramilitary, terrorist and criminal fundraising capabilities. It has a global network of support that spans the Americas, Europe, the Middle East and Africa. Hizballah has an established fundraising network in Canada.

Khalistani extremist groups, such as Babbar Khalsa International and the International Sikh Youth Federation, are suspected of raising funds for the Khalistan cause in a number of countries, particularly in countries that have large Sikh diaspora populations. There appears to be a global network but it is unclear how strong it is and the motivations surrounding the support. These groups used to have an extensive fundraising network in Canada, but it now appears to be fractured and diffuse.

Geopolitical, socio-economic, governance and legal framework features of a country are important components of a nation's identity and position in the world. Internationally, Canada is recognized as a multicultural and multiethnic country with a stable economy and strong democratic institutions. Although these features of Canada are positive, some can be subject to criminal exploitation. Criminals, including money launderers and terrorist financiers, can be attracted to Canada as a result of inherent vulnerabilities associated with Canada's geography, demographics, stable open economy, accessible financial system, proximity to the United States and well-developed international trading system. It is important to underscore that this assessment examines the inherent vulnerabilities of various economic sectors and financial products and does not account for the significant mitigation measures that are in place to address these risks.

While being mindful of the contextual vulnerabilities of Canada, experts assessed the inherent ML/TF vulnerabilities of 27 economic sectors and financial products, using the following five rating criteria:

- Inherent Characteristics: the extent of the sector's economic significance, complexity of operating structure, integration with other sectors and scope and accessibility of operations.

- Nature of Products and Services: the nature and extent of the vulnerable products and services and the volume, velocity and frequency of client transactions associated with these products and services.

- Nature of the Business Relationships: the extent of transactional versus ongoing business, direct versus indirect business relationships and exposure to high-risk clients and businesses.

- Geographic Reach: the exposure to high-risk jurisdictions and locations of concern.

- Nature of the Delivery Channels: the extent to which the delivery of products and services can be conducted with anonymity (face-to-face, non-face-to-face, use of third parties) and complexity (e.g., multiple intermediaries with few immediate controls).

The assessment indicates that there are a significant number of economic sectors and financial products that are inherently vulnerable to money laundering and terrorist financing. Of the 27 rated areas, the overall ML/TF vulnerability was rated "very high" for five sectors and products, "high" for 16 sectors and products, "medium" for five sectors and products and "low" for one sector (see Table 3). Inherent vulnerabilities and risks are, however, the subject of mitigation and control measures provided by the AML/ATF regime, including through preventive measures and effective supervision.

Although the vulnerabilities assessment examined sectors and products individually, it is important to note that the six designated domestic systemically important banks (D-SIBs) are financial conglomerates that dominate Canada's financial sector, and are deeply involved in multiple business lines, including banking, insurance, securities and trust services. The inherent vulnerability of the D-SIBs was explicitly assessed as part of the category of domestic banks and rated very high, while their presence in other sectors was included in the assessment of those sectors. Given their size, scope and reach, and if assessed on a consolidated basis, the inherent vulnerability of the D-SIBS would naturally be very high.

Corporations (and company services providers), express trusts, lawyers[31] and NPOs, although not subject to reporting obligations under the PCMLTFA, were formally included as part of this assessment since it was determined to be necessary to assess their ML/TF vulnerabilities given their importance and widespread use within Canada. Other sectors and products that are not currently covered under the PCMLTFA will continue to be assessed for ML/TF risks. These include, but are not limited to, cheque cashing businesses, closed-loop pre-paid access,[32] factoring companies,[33] financing and leasing companies, ship-based casinos, unregulated mortgage lenders and white-label automated teller machine providers.

Table 3

Overall Inherent Money Laundering/Terrorist Financing Vulnerability Rating Results

Very High Vulnerability Rating

Corporations1

Domestic Banks

Express Trusts1

National Full-Service MSBs2

Small Independent MSBs

High Vulnerability Rating

Brick and Mortar Casinos

Company Services Providers

Credit Unions and Caisses Populaires

Dealers in Precious Metals and Stones

Foreign Bank Branches

Foreign Bank Subsidiaries

Internet-Based MSBs

Legal Professionals

Life Insurance Companies

Registered Charities

Open-Loop Prepaid Access

Real Estate Agents and Developers

Securities Dealers

Smaller Retail MSBs

Trust and Loan Companies

Virtual Currencies

Medium Vulnerability Rating

Accountants

British Columbia Notaries

Independent Life Insurance Agents and Brokers

Provincial Online Casinos

Wholesale and Corporate MSBs

Low Vulnerability Rating

Life Insurance Intermediary Entities and Agencies3

1 The vulnerability relates to the ability of these entities to be used to conceal beneficial ownership, therefore facilitating the disguise and conversion of illicit proceeds.