2017 Report on Suicide Mortality in the Canadian Armed Forces (1995 to 2016) (Abridged Version)

Alternate Formats

Surgeon General Report

Surgeon General Health Research Program

Surgeon General Document Number (SGR-2017-002)

October 2017

Author:

- Elizabeth Rolland-Harris, MSc, PhD, Directorate of Force Health Protection, Directorate of Mental Health

Reviewed by:

- Colonel S.F. Malcolm, Director, Directorate of Force Health Protection

- Colonel C.A. Forestier, Director, Directorate of Mental Health

Approved by:

- Brigadier-General A.M.T. Downes, Surgeon General

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2017

Table of Contents

- Abstract

- Executive Summary

- List of Figures

- List of Tables

- Table 1: Mental Health Factors

- Table 2: Prevalence of Documented Work and Life Stressors Prior to Suicide

- Table 3: CAF Regular Force Male Multiyear Suicide Rates (1995-2016)

- Table 4: Comparison of CAF Regular Force Male Suicide Rates to Canadian Male Rates Using Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMRs) (1995-2013)

- Table 5: Standardized Mortality Ratios for Suicide in the CAF Regular Force Male Population by History of Deployment (1995-2016)

- Table 6: Comparison of CAF Regular Force Male 5-Year Suicide Rates by Deployment History Using Direct Standardization (1995-2016)

- Table 7: Standardized Mortality Ratios for Suicide in CAF Regular Force Males by Environmental Command (2002-2013)

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Data Sources and Methods

- 3. Results

- 4. Data Limitations

- 5. Conclusions

- References

Introduction

Suicide is a tragedy and an important public health concern. Suicide prevention is a top priority for the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF). In order to better understand suicide in the CAF and refine ongoing suicide prevention efforts, the Directorate of Force Health Protection (DFHP) and the Directorate of Mental Health (DMH) regularly conduct analyses to examine suicide rates and the relationship between suicide, deployment and other potential suicide risk factors. This report is an update covering the period from 1995 to 2016.

Methods

This report describes crude suicide rates from 1995 to 2016, comparisons between the Canadian population and the CAF using Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMRs), and suicide rates by deployment history using SMRs and direct standardization. It also examines variation in suicide rate by environmental command, and using data from Medical Professional Technical Suicide Reviews (MPTSR), looks at the prevalence of other suicide risk factors that occurred in 2016.

Results

Between 1995 and 2016, there were no statistically significant increases in the overall suicide rates. The number of Regular Force males that died by suicide was not statistically higher than that expected based on Canadian male suicide rates. While the suicide rate among males with a history of deployment was not significantly higher than in comparable civilians, rate ratios indicated that there was a trend for those with a history of deployment to be at an increased risk of suicide compared to those who have never been deployed. However, this difference was not statistically significant. These rate ratios also highlighted that, since 2006 and up to and including 2016, being part of the Army command significantly increases the risk of suicide, relative to those who are part of the other environmental commands.

The most recent findings suggest that the suicide rate in those with a history of deployment may now be lower than those with no history of deployment (suicide rate ratio: 0.59). This is in discordance with the 10-year (2005 – 2014) pattern that found that those with a history of deployment were possibly at higher risk than those with no history of deployment. However, this most recent finding fell just short of statistical significance, but does suggest that the pattern seen during and following the Afghanistan conflict may be shifting. Regular Force males under Army command were at significantly increased risk of suicide relative to Regular Force males under non-Army commands (age-adjusted suicide rate ratio = 2.39, CI: 1.76, 3.25). The gap between the rates in Army and non-Army command Regular Force males over the past five years also appears to be narrowing, particularly when observing the 3-year moving average. Regular Force males under Army command in the combat arms trades had statistically significant higher suicide rates (32.77/100,000, CI: 25.73, 41.62) than non-combat arms Regular Force males (16.54/100,000, CI: 13.51, 20.21).

Results from the 2016 MPTSRs is in support of a multifactorial causal pathway (this includes biological, psychological, interpersonal, and socio-economic factors) for suicide rather than a direct link between single risk factors (e.g. Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) or deployment) and suicide. This is consistent with MPTSR findings from previous years.

Conclusions

Suicide rates in the CAF did not significantly increase over time, and after age standardization, they were not statistically higher than those in the Canadian population. However, small numbers have limited the ability to detect statistical significance. The evidence supporting history of deployment as a related risk factor appears to be waning, although the numbers supporting this observation were non-significant.

The increased risk in Regular Force males under Army command compared to Regular Force males under non-Army command is a finding that continues to be under observation by the CAF.

Keywords: Age-adjusted rate; Canadian Forces; Canadian population; deployment; rate ratio; rates; standardized mortality ratio; suicide.

Executive Summary

The tragic loss of life of Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members through suicide requires our continual focus to better understand it and guide our suicide prevention efforts. This report describes the suicide experience in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF). It describes the epidemiology of Regular Force males that died by suicide between 1995 and 2016, with an additional focus on the risk factors associated with the Regular Force males that died by suicide in 2016.

This report is produced by the Epidemiology section of the Directorate of Force Health Protection.

Methods

Data described in Section 3.1 [Results from the Medical Professional Technical Suicide Review (MPTSR) Reports, Regular Force Males, 2016 Results Only] are collected during the MPTSR process, following a suicide. An MPTSR is a quality assurance tool for Canadian Forces Health Services (CFHS) that is ordered by the Deputy Surgeon General immediately following the confirmation of all Regular Force and primary Reserve Force suicides. Each MPTSR is typically conducted by a team consisting of a mental health professional and a General Duty Medical Officer.

Epidemiological data described in Section 3.2 (Epidemiology of Suicide in Regular Force Males, 1995 – 2016, inclusive) and 3.3 (Epidemiology of Suicide in Regular Force Males, by environmental command, 2002 – 2016, inclusive) was obtained from the Directorate of Casualty Support Management up to 2012. As of September 2012, the number of suicides was tracked and provided by DMH. Finally, denominator data (Canadian suicide counts by age and sex) were obtained from Statistics Canada.

Frequencies, standardized mortality ratios (ratio of observed number of CAF suicides to expected number of CAF suicides, if the CAF were to have the same age and sex makeup as the Canadian general population) and directly standardized rates were calculated.

Results

Mental Health Diagnosis of Those Who Died by Suicide in 2016

Identified mental health disorders at time of death included depressive disorders (35.7%), post-traumatic stress disorder (7.1%), or an anxiety disorder (21.4%). No evidence of other types of trauma and stress-related disorders were reported. A documented substance use disorder was reported in 42.9% of 2016 Regular Force male suicide deaths. It was common (64.3%) to have at least two mental health diagnoses at the time of death.

Work/Life Stressors of Those Who Died by Suicide in 2016

At the time of death, 85.7% of the Regular Force males that died by suicide in 2016 reportedly had at least one work and/or life stressor (including: failing relationships, friend/family suicide, family/friend death, family and/or personal illness, debt, professional problems, legal problems); over half of them had at least three concomitant stressors prior to their death.

Crude Suicide Rates, 1995 – 2016

In 2015 – 2016, the crude suicide rate of Regular Force males was 24.8 (16.5, 36.0) per 100,000. This was the highest crude rate to date. However, the confidence intervals overlapped between all time periods, suggesting that there was no significant difference in crude rates over time. Additionally, the findings for the last time period includes only two years (2015 and 2016) and should therefore be further monitored to ascertain whether this pattern persists.

Comparison of CAF Regular Force Male Suicide Rates to Canadian Rates Using Standardized Mortality Ratios, 1995 – 2016

As with the crude rates, the confidence intervals for the Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMRs) overlapped between the 5-year periods (4 years for 2010 to 2013), suggesting that there was no significant change in SMRs over time.

Impact of Deployment on CAF Regular Force Male Suicide Rates

SMRs comparing those with a history of deployment to those without (1995 – 2013) did not identify a statistically significant difference in suicide rate between these deployment status groups. Using direct standardization for the 10-year time period 2005 – 2014 resulted in a suicide rate ratio comparing those with a history and those without a history of deployment that approached statistical significance [1.48 (95% Confidence interval (CI): 0.98, 2.22)]. This suggests that those Regular Force males with a history of deployment may be at increased risk of taking their own lives, compared to those with no history of deployment. However, deployment may be confounded by other unexplained variables. Furthermore, it is unclear whether this trend will continue to be significant over time, seeing as the (non-significant) rate ratio for 2015 – 2016 was below one for the first time since this analysis has been conducted.

Impact of Environmental Command on CAF Regular Force Male Suicide Rates

The age-adjusted suicide rate ratio comparing Army to non-Army command for the period 2002 – 2016 was statistically different [2.39 (1.76, 3.25)]. This finding was supported by a significantly higher Army command SMR in 2007 – 2011 [173% (123, 236)] and 2012 – 2013 [187% (109, 299)]. The suicide rate in the Regular Force male population who were in an Army combat arms occupation appeared higher than the overall suicide rate of all non-combat arms Regular Force males [32.77 (95% CI: 25.73, 41.62) versus 16.54 (95% CI: 13.51, 20.21)].

1. Introduction

Suicide is a tragedy and an important public health concern. Suicide prevention is a top priority for the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF). Monitoring and analysing suicide events of CAF members provides valuable information to guide and refine ongoing suicide prevention efforts. The evidence collected in the annual reports is used to:

- Ensure that clinical and prevention programmes optimally target high risk individuals; and

- Ascertain why some individuals are not availing themselves of available prevention and clinical resources prior to taking their own lives.

There has been concern expressed since the early 1990s about the apparent rate of suicide in the CAF and its possible relationship to deployment. In response to these concerns, the CAF began an active suicide mortality surveillance program to determine the rate of suicide among CAF personnel overall in comparison to the Canadian General Population (CGP), as well as the rate of suicide in those personnel with a history of deployment compared to those without such a history.

Historically, reports on suicide produced by the Epidemiology section of the Directorate of Force Health Protection have focused on the surveillance and epidemiology of suicide within the CAF. Since 2015, the report has expanded its scope to describe the larger body of evidence related to suicide in the CAF, and to describe its evolution over the last 21 years. This report provides a more in-depth analysis of the variation of suicide rates by environmental command, as well as information on the mechanisms and underlying risk factors that may have contributed to the Regular Force male suicides that took place in 2016 based on an assessment of the Medical Professional Technical Suicide Reviews (MPTSRs).

This report, as with previous ones, only analyzes Regular Force males who have died by suicide. The reasons are as follows:

- Female suicide numbers are small (range between 0 and 2 events per year), which precludes the ability to conduct trend analyses. Reporting separately on their characteristics would contravene the privacy of the involved individuals (“identity” and “attribute” disclosure 1). Aggregating female data with male data would circumvent these disclosure concerns. However, the differences in suicide risk factors, behaviours and mechanisms between sexes warrant gender-specific evaluation of suiciderelated evidence. [1], [2]

- For Reserve Force data, there are also issues around data completeness, in addition to those regarding identity and attribute disclosure. Reserve Force records may be incomplete for both suicide events and information on the size and characteristics of the Reserve Force, both of which are needed to calculate reliable suicide rates. There is a high turnover for Class A Reservists and suicides among this group may not be brought to the attention of the Department of National Defence (DND). The true number at risk is also uncertain.

- Since data on suicide attempts are often incomplete, in keeping with other occupational health studies, this report only includes suicides, not attempts. Furthermore, the data used for this analysis include only those who have died of suicide while active in the Regular Forces, and do not include those who have died of suicide after leaving the military.

Because of these limitations, the evidence presented in this report applies only to Regular Force males.

2.1.1 Medical Professional Technical Suicide Review

Data on the methods of suicide and risk factors (mental health and psycho-social factors) are collated from the Medical Professional Technical Suicide Reviews (MPTSR). MPTSRs are ordered by the Deputy Surgeon General when a death is deemed a likely suicide, and are conducted by a team consisting of a mental health professional and a General Duty Medical Officer (GDMO). This team reviews all pertinent health records and conducts interviews with medical personnel, unit members, family members and other individuals who may be knowledgeable about the circumstances of the suicide in question. MPTSRs began in 2010 as a Quality Assurance tool within the Canadian Forces Health Services (CFHS) to provide the Surgeon General with observations and recommendations for improvements with suicide prevention efforts within CFHS. All of this information is collected and managed by the Directorate of Mental Health (DMH).

2.1.2 Epidemiological Surveillance

Information on the number of suicides and demographic information was obtained from the Directorate of Casualty Support Management (DCSM) up to 2012. As of September 2012, suicides were tracked and provided by DMH. DMH also cross-references their results with those collected by the Administrative Investigation Support Centre (AISC), which is part of the Directorate Special Examinations and Injuries (DSEI).

Information on deployment history and CAF population data (by age, sex and deployment history) originated from the Directorate of Human Resources Information Management (DHRIM). History of deployment was based on department IDs and deployment units from DHRIM. It should be noted that the number of personnel with a history of deployment occasionally changes from previous reports due to updating of DHRIM records.

Canadian suicide counts by age and sex were obtained from Statistics Canada. Data were available up to 2013 at the time of preparation of this report. Canadian suicide rates are derived from death certificate data collected by the provinces and territories and collated by Statistics Canada. Codes utilized for this report were ICD-9 E950-E959 (suicide and self-inflicted injury) in the Shelf Tables produced by Statistics Canada from 1995 to 1999. For 2000 to 2008 the number of suicide deaths was based on ICD-10 codes X60-84 and Y87.0 utilizing Canadian Socio-Economic Information Management System (CANSIM) Table 102-0540 from Statistics Canada, for 2009 to 2013 suicide deaths CANSIM Table 102-0551 was the source. Open verdict cases (ICD-9: E980-E989; ICD-10: Y30-Y34) are excluded by Statistics Canada, although they are routinely included in suicide statistics reported elsewhere (e.g. UK – both in civilian and military contexts). To ensure valid comparisons, the Statistics Canada exclusions were followed for these analyses. All CGP denominators were taken from Statistics Canada CANSIM Table 051-0001. Denominators, up to and including 2010, were final inter-censal estimates, while 2011, 2012 and 2013 were based on final post-censal estimates.

2.2 Methods

Crude CAF Regular Force male suicide rates were calculated from 1995 to 2016. Suicide rates prior to 1995 have not been calculated as the historical method of ascertainment of suicides within the CAF is not well defined.

To compare CAF Regular Force male rates with general Canadian male population rates, standardization by age using the indirect method was used to provide Standardized Mortality Ratios (SMRs) for suicide up to 2013. This method controls for the difference in age distribution between the CAF Regular Force male and general Canadian male populations. An SMR is the observed number of cases divided by the number of cases that would be expected in the population at risk based on the age and sex-specific rates of a standard population (the CGP in this case) expressed as a percentage. Therefore, an SMR less than 100% indicates that the population in question has a lower rate than the CGP, while an SMR greater than 100% indicates a higher rate.

SMRs were calculated separately for those Regular Force males with and without a history of deployment.

The calculation of Confidence Intervals (CIs) for population-based data is provided here for those who may want to generalize the results to other years. Confidence intervals were calculated for CAF Regular Force male suicide rates and SMRs directly with Poisson distribution 95% confidence limits using the exact method described by Breslow and Day [5].

To compare suicide risk among those Regular Force males with a history of deployment directly to those without, direct standardization was done using the total Regular Force male population of the CAF as the standard. Age-adjusted suicide rates for those Regular Force males with and without a history of deployment were compared using rate ratios.

Because the annual suicide numbers for the Canadian Armed Forces are small, they are highly influenced by random annual variability. Moving averages, which take an average of the year of interest as well as the previous and following year, 2 have been used by others in a similar military suicide context. [3] This method attempts to control the aforementioned variability caused by small numbers and provide a snapshot of potential temporal trends in the data.

3.1 Results from the Medical Professional Technical Suicide Review Reports, Regular Force Males, 2016 Results Only

3.1.1 Mental Health Factors

Approximately one third of the individuals (35.7%) had a documented depressive disorder, and three individuals (21.4%) had an anxiety disorder (Table 1). One individual (7.1%) was reported as having a diagnosis of PTSD prior to death; no other trauma or stress-related disorders were captured. Nearly two thirds of all individuals (64.3%) had a documented substance use disorder. In addition to mental health factors, three (21.4%) of the individuals had been diagnosed with a traumatic brain injury (N.B.: The etiology of the traumatic brain injuries was not identified in the MPTSR; these may or may not be combat-related) with all three of these occurring at least one year preceding their deaths. Overall, nine (64.3%) individuals had at least two mental health factors at the time of death. Whether or not these mental health factors were related to operational stress 3 was not captured by the MPTSR.

* Total does not equal 100% as 64.3% of individuals had more than 1 mental health factors.

Documented evidence of prior suicidal ideation and/or prior suicide attempts was noted for 5 (35.7%) individuals.

3.1.2 Work and Life Stressors

For the twelve (85.7%) Regular Force male suicide deaths in 2016 for whom stressors were reported, all had at least two of the stressors listed in Table 2. Eight individuals (57.1%) reportedly had at least three concomitant stressors prior to their death.

* Total does not equal 100% as 78.6% of individuals had more than 1 stressor

Four individuals (28.9%) had a documented history of being physically, sexually, and/or emotionally abused during their lifetime, and 4 (28.9%) individuals had been the perpetrators of physical abuse and/or emotional abuse.

Within two years prior to their death, 6 of the individuals (42.9%) had experienced some sort of legal or disciplinary proceedings (e.g. police investigation, legal proceeding, Absent Without Leave (AWOL), incarceration). At the time of death, 2 (14.3%) were in the process of being released from the CAF (disciplinary, administrative or medical) and both had also experienced legal or disciplinary proceedings in the preceding 12 months.

3.2 Epidemiology of Suicide in Regular Force Males, 1995 – 2016, Inclusive

The annual number of male Regular Force suicides between 1995 and 2016, inclusive, are captured in Table 3, as are the corresponding 5-year crude rates. The crude CAF Regular Force male suicide rates have not appreciably changed between 1995 and 2009. While they appear to have increased somewhat in the last five years, the confidence intervals for all time periods, including 2010 to 2016, overlap, indicating that this increase is not statistically significant.

| Year | Number of CAF Regular Force Male Person-Years 4 | Number of CAF Regular Force Male Suicides | CAF Regular Force Male Suicide Rate per 105 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 62,255 | 12 | |

| 1996 | 57,323 | 8 | |

| 1997 | 54,982 | 13 | |

| 1998 | 54,284 | 13 | |

| 1999 | 52,689 | 10 | |

| 1995-1999 | 281,533 | 56 | 19.9 (15.1, 26.0) |

| 2000 | 51,537 | 12 | |

| 2001 | 51,029 | 10 | |

| 2002 | 52,747 | 9 | |

| 2003 | 54,137 | 9 | |

| 2004 | 53,873 | 10 | |

| 2000-2004 | 263,323 | 50 | 19.0 (14.1, 25.1) |

| 2005 | 53,648 | 10 | |

| 2006 | 54,301 | 7 | |

| 2007 | 55,140 | 9 | |

| 2008 | 55,704 | 13 | |

| 2009 | 56,813 | 12 | |

| 2005-2009 | 275,606 | 51 | 18.5 (13.8, 24.4) |

| 2010 | 58,723 | 12 | |

| 2011 | 58,622 | 21 | |

| 2012 | 57,940 | 10 | |

| 2013 | 57,687 | 9 | |

| 2014 | 56,699 | 16 | |

| 2010-2014 | 289,866 | 68 | 23.5 (18.4, 29.9) |

| 2015 | 56,284 | 14 | |

| 2016 | 56,561 | 14 | |

| 2015-2016 | 112,845 | 28 | 24.8 (16.5, 36.0) |

* The number of confirmed suicides for CAF Regular Force males for 2009 increased by one since the “Suicide in the Canadian Forces 1995 to 2012” report.

Regular Force female rates were not calculated because female suicides were uncommon. There were no suicides in females from 1995 to 2002, two in 2003, no suicides in females in 2004 and 2005, one per year from 2006 to 2008, two in 2009, none in 2010, one in 2011, three in 2012, one in 2013, one in 2014, one in 2015, and one in 2016.

A comparison of suicide rates among Regular Force males to their civilian counterparts is presented in Table 4. The 2005 to 2009 data indicate that the CAF Regular Force male population had a 14% lower suicide rate than the CGP after adjusting for the age differences between the populations. This SMR is not statistically significant as the confidence intervals include 100%. While the SMR for 2010 – 2013 is above 100%, the confidence intervals include 100%, making these results statistically non-significant. Finally, all SMR period confidence intervals overlap, suggesting that there is no statistically significant difference between the different 5-year SMRs.

* Some estimates may have changed slightly compared to previous reports due to updates in CAF Regular Force male population numbers.

** Based on four years of observations only.

† Statistically significant.

A further analysis comparing SMRs in those with a history of deployment to those without a history of deployment is presented in Table 5. Over time, the higher SMR switched between those with a history of deployment and those without; however, none of the SMRs presented here (for any time period) were statistically significant.

* Some estimates may have changed slightly compared to previous reports due to updates in CAF Regular Force male population numbers.

** Based on four years of observations only.

The 10-year rate representing 1995 – 2004 illustrated a slightly lower SMR for those with a history of deployment (SMR: 75% [95% CI: 54% – 100%]) than for those without a history of deployment (SMR: 77% [95% CI: 60% – 100%]); both of these estimates approached, but did not reach, statistical significance.

An analysis comparing the same groups but using a statistically different method (direct standardization) also failed to identify a statistically significant relationship between those with a history of deployment versus those without a history of deployment. 10-year rates (1995 – 2004 and 2005 – 2014) were also non-significant.

* Some estimates may have changed slightly compared to previous reports due to updates in CAF Regular Force male population numbers.

3.3 Epidemiology of Suicide in Regular Force Males, by Environmental Command, 2002 – 2016, Inclusive

Over the past 15 years, there were 103 deaths by suicide among the Regular Force males within the Army command and 72 within all other environmental commands combined (Navy, Air Force and Other). The crude Army suicide rate was 33.32 (95% CI: 27.23, 40.72) compared to 13.34 (95% CI: 10.50, 16.88) for the non-Army rate. The confidence intervals for the rate in each environmental command did not overlap indicating that there was a statistically significant difference between the two groups. The age-adjusted rates were very similar to the crude rates (Army: 33.30; Non-Army: 13.94). Furthermore, the age-adjusted suicide rate ratio was significant [2.39 (95% CI : 1.76, 3.25)], meaning that the age-adjusted suicide rate among Regular force males in the Army was nearly two and a half times higher than in the non-Army commands.

SMRs for each environmental command as well as for each time period (2002 – 2006, 2007 – 2011, 2012 – 2013) were conducted (Table 7). The SMRs for the Army command for the 2007 – 2011 and 2012 – 2013 periods were significantly above 100%, while the SMR for Navy/Other for 2012 – 2013 was significantly below 100%. All other SMRs were not statistically significant. Furthermore, the SMR for all environmental commands combined was systematically non-significant across all three time periods.

† Statistically significant.

The suicide rate in Army combat arms occupations in the Regular Force male population was also calculated. Between 2002 and 2016, there were a total of 70 suicides among Regular Force males who had a combat arms MOSID. There were no suicides during this time frame in females with a combat arms MOSID.

The suicide rate in the Regular Force male population who were in an Army combat arms occupation appeared higher than the overall suicide rate of all non-combat arms Regular Force males [32.77 (95% CI: 25.73, 41.62) versus 16.54 (95% CI: 13.51, 20.21)]. As the confidence intervals between the two rates did not overlap, the difference was statistically significant, indicating an increased risk of suicide in Regular Force male combat arms relative to those in non-combat arms.

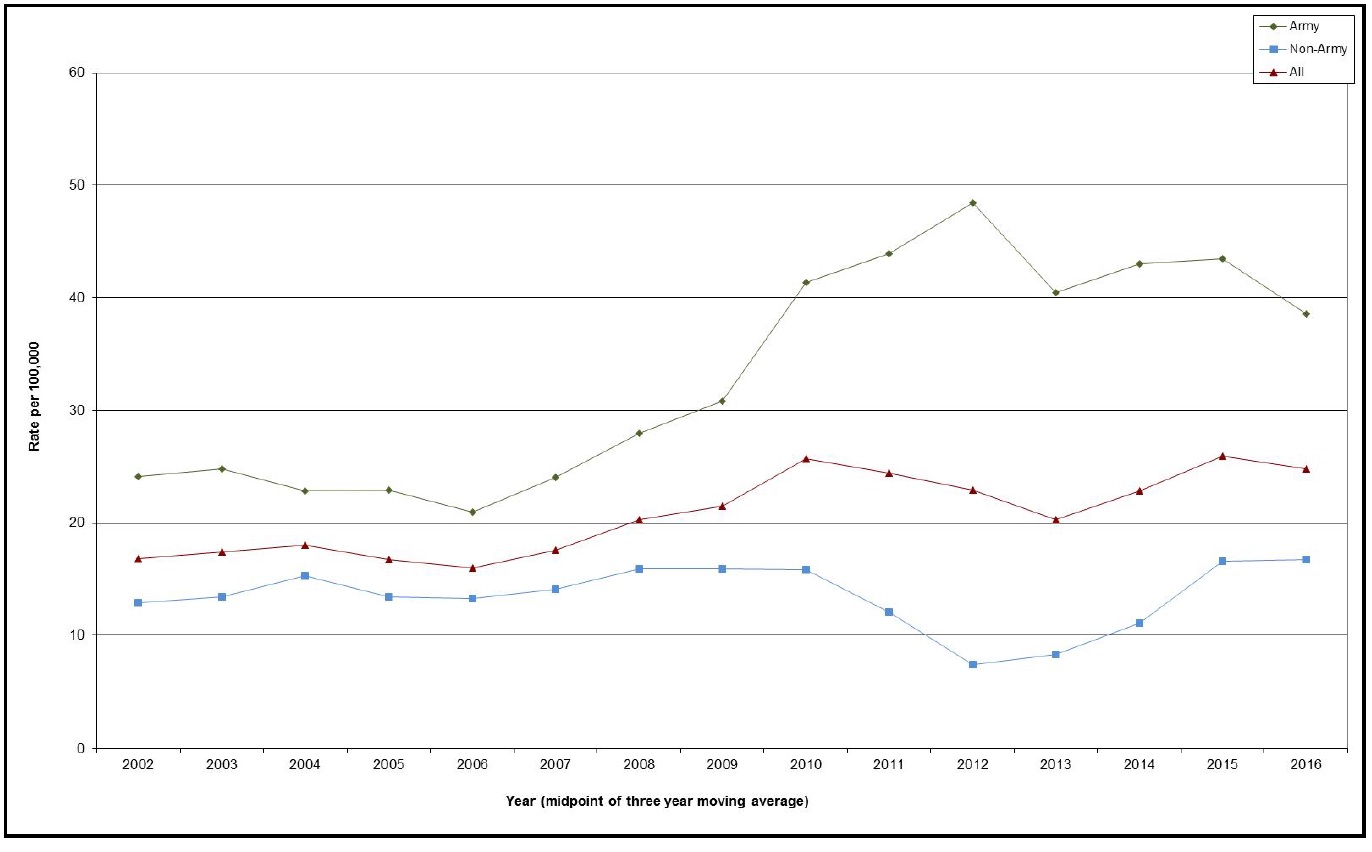

Figure 1 shows the moving average trends for all environmental commands combined (represented by the triangular markers), Army command only (represented by the diamond markers) and for the Non-Army commands (represented by the square markers). What this figure illustrates is that while the Army command rate was always slightly higher or equal to other groupings up until 2008. From 2009 onwards, it showed a larger rate increase in Army than in non-Army or All commands. This rise in the Army mean appeared to have stopped post-2012, but the average remained well above pre-2010 levels. Between 2009 and 2013, the non-Army moving average rate appeared to be decreasing, but subsequently returned to pre-2011 levels.

Figure 1 Text

| Year (midpoint of three year moving average) | All | Army | Non-Army |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2002 | 16.8 | 24.1 | 12.9 |

| 2003 | 17.4 | 24.8 | 13.4 |

| 2004 | 18.0 | 22.8 | 15.3 |

| 2005 | 16.7 | 22.9 | 13.4 |

| 2006 | 16.0 | 21.0 | 13.3 |

| 2007 | 17.6 | 24.1 | 14.1 |

| 2008 | 20.3 | 27.9 | 15.9 |

| 2009 | 21.5 | 30.8 | 15.9 |

| 2010 | 25.7 | 41.3 | 15.8 |

| 2011 | 24.4 | 43.9 | 12.1 |

| 2012 | 22.9 | 48.4 | 7.4 |

| 2013 | 20.3 | 40.4 | 8.3 |

| 2014 | 22.9 | 43.0 | 11.1 |

| 2015 | 26.0 | 43.5 | 16.6 |

| 2016 | 24.8 | 38.6 | 16.7 |

4. Data Limitations

- The numbers on which these analyses are based are very small and unstable; consequently, these findings must be interpreted with caution.

- Female suicide numbers are small (range between 0 and 2 events per year), which precludes the ability to conduct trend analyses.

- Since the individual’s last known unit/base was used to categorize environmental command, this did not take into account that the individual may have just recently been posted to that environmental command and therefore not really have functioned under that environmental command for an appreciable amount of time (e.g. when one goes on training).

- The denominators for this study (number of CAF Regular Force males in each environmental command) may also be inaccurate since the DHRIM system is not systematically updated. Consequently, denominator data may differ, depending on when the report was run by DHRIM.

- The lack of DHRIM data prior to 2002 makes it impossible to ascertain whether the pre-Afghanistan suicide experience for Army command relative to non-Army command was any different to what is described here.

- Finally, the wide confidence intervals for many of the rates reported here indicate that the analyses may not have the power to detect statistically significant differences.

5. Conclusions

The following conclusions are reached with the understanding that statistical analysis may not identify a true difference due to the small total number of suicides (i.e. the power of the study is low):

- From 1995 to 2016, there has been no statistically significant change in the overall suicide rate of CAF Regular Force males.

- The rate of suicide when standardized for age and sex is not significantly different from that of the CGP.

- High prevalence of substance use disorder, mood disorders, spousal/intimate partner breakdown and/or of career-related proceedings may be indicators of heightened suicide risk in CAF Regular Force males.

- Analyses suggest that there is a significantly higher crude rate of suicide in Regular Force males in the Army command relative to other CAF environmental commands. This may be driven in part by the significant difference in the crude Regular Force male suicide rate for the combat arms trades relative to the non-combat arms suicide rate.

References

[1] Moscicki, E.K., Gender differences in completed and attempted suicides, Ann Epidemiol. 1994;4(2):152-8.

[2] Canetto, S.S. and Sakinofsky, I., The Gender Paradox in Suicide, Suicide Life Threat Behav. 1998;28(1);1-23.

[3] Defence Analytical Services and Advice, Suicide and Open Verdict Deaths in the UK Regular Armed Forces 1984-2012, DASA (MoD): Bristol, UK, Retrieved 27-Feb-2014: http://www.dada.mod.uk/publications/health/deaths/suicide-and-open-verdict/2012/2012.pdf

[4] A Dictionary of Epidemiology, M. Porta, S. Greenland, J.M. Last, eds., Fifth Edition, New York (USA): Oxford UP, 2008.

[5] Breslow, N.E. and Day, N.E. (1987). Statistical Methods in Cancer Research. Vol. II, The Design and Analysis of Cohort Studies (IARC Scientific Publication No. 82). Lyon, France: International Agency for Research on Cancer.

1 Statistics Canada defines identity disclosure as: “identifying an individual from a table, typically from small cell showing 1 or 2 persons with a characteristic. If no other information is released it is not necessarily a confidentiality breach but the perception of a breach is there. This translates into a “small cell” problem, where, for the purpose of vital statistics, “small” is defined as frequencies representing fewer than 5 births, deaths or stillbirths.“

Attribute disclosure is defined as: “disclosing attributes of individuals, even if they are not specifically identified. For example, a table row where all units share the same attribute because they are found in a single column. This translates into “zero cell” and “full cell” problems. Not all zero cells are problematic. Full cells, which occur when only one cell in a row or column is nonzero, are more likely to be.”

Taken from: Statistics Canada. Disclosure control strategy for Canadian Vital Statistics Birth and Death Databases. Ministry of Industry: Ottawa, 2016.

2 For example, the moving average value for 2006 would be an average of 2005, 2006 and 2007. For 2002 and 2016 where there are no prior and/or subsequent years, the moving average was based on two years’ worth of data (e.g. 2016 = average of 2015 and 2016).

3 As defined in the Surgeon General’s Mental Health Strategy, “… the term “Operational Stress Injury” (OSI) is not a diagnosis; rather it is a grouping of diagnoses that are related to injuries that occur as a result of operations. The most common OSIs are PTSD, major depression and generalized anxiety. This term has helped break down several barriers to care and reduce the stigma surrounding mental illness.”

4 Person time is defined as “a measurement combining person and time as the denominator in incidence and mortality rates when, for varying periods, individual subjects are at risk of developing disease or dying. It is the sum of the periods of time at risk for each of the subjects. The most widely used measure is person-years,” (emphasis added) [4].