Background of the Report of the CF Expert Panel on Suicide Prevention

Suicide is a rare but tragic event, taking the lives of close to 4,000 Canadians each year [1]. It is aleading cause of death among the demographic group that forms the bulk of military personnel [1], and it contributes importantly to years of potential life lost in that population [2].

The finality of the suicidal act makes prevention an especially important control measure. 1 In theory,all suicides should be preventable, but in practice, only some are. Analogously, all motor vehicle accident deaths should be preventable: If people were to drive prudently and avoid running into other vehicles, pedestrians, or stationary objects, no one would die in a car crash. 2 In practice, people are inattentive, drive when road conditions are poor, speed, disobey traffic laws, drink and drive, and soon… with predictable consequences. 3

Even for patients who are in mental health care, clinical quality control audits have shown that only 20 to 25% of suicides are judged to have been preventable [3;4]. Still, much as a broad range of interventions and technological advances have decreased the road traffic accident fatality rate [5], a number of interventions have been shown to decrease the risk of suicidal behaviour [6]. There are also many measures that plausibly have suicide preventive effects but for which firm evidence is lacking.

Suicide prevention in military organizations has a special significance, particularly at present:

- Mental health problems are leading contributors to suicidal behaviour [6], and certain military activities (notably armed combat) can trigger mental health problems [7]. While suicide rates in active-duty military populations are usually somewhat lower than those of the general population [8-11], veterans of some [12;13] (but not all [14;15]) conflicts appear to be at higher risk of suicide. Thus, the military has a due diligence responsibility to mitigate what could be an occupational health problem.

- The conflicts in SW Asia are exposing larger numbers of Western military personnel to greater degrees of risk and adversity than in any time in recent memory.

- Suicide rates in the US Army and Marine Corps have increased dramatically over the past few years. In contrast, the CF suicide rate has remained stable over that same period, despite the extraordinary demands of the mission in Afghanistan. Rates have also been stable in the UK [16;17], which also has heavy operational commitments in SW Asia. However, the number of suicides in the CF is low enough that the ability to detect a small to modest increase in the suicide rate from year-to-year is limited (see ANNEX C).

- Most importantly, military organizations have control over a broader range of potential targets for suicide prevention than does the typical employer. This is because the military is, in addition to being an employer, also a health care delivery system, an occupational medicine service, a public health entity, an insurance plan, etc.

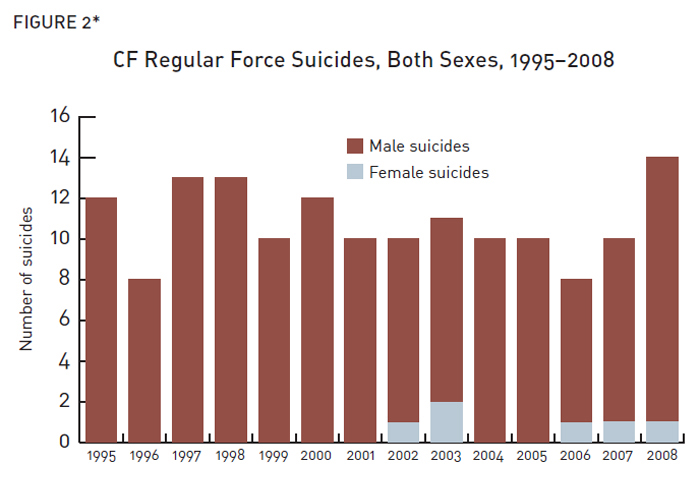

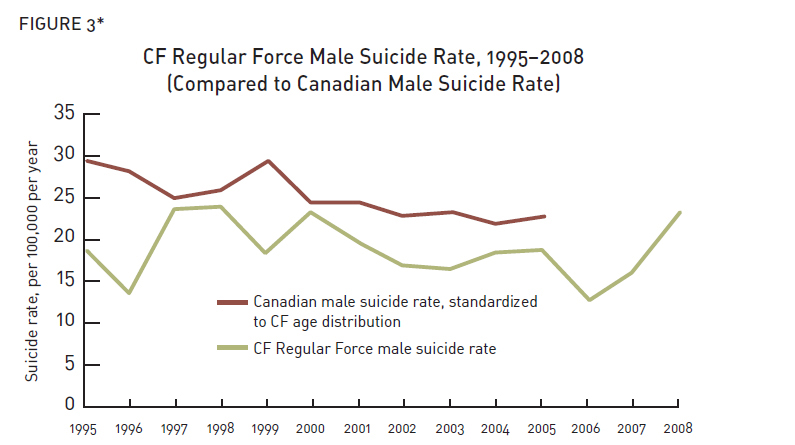

As described in detail in ANNEX C and shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3, the number of suicides in the CF is low in absolute terms (approximately 10 per year), and the rate in males 4 is about 20% below that of the Canadian general population of the same age distribution (specifically about 17 to 20 suicides per 100,000 men per year). Despite the deployment of close to 30,000 members in support of the mission in Afghanistan, male suicide rates have not increased over the past five years.

*Data from the CF suicide surveillance system.

Figure 2: CF Regular Force Suicides, Both Sexes, 1995-2008

Figure 2: CF Regular Force Suicides, Both Sexes, 1995-2008 (Text equivalent)*

| Year | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 0 | 12 |

| 1996 | 0 | 8 |

| 1997 | 0 | 13 |

| 1998 | 0 | 13 |

| 1999 | 0 | 10 |

| 2000 | 0 | 12 |

| 2001 | 0 | 10 |

| 2002 | 1 | 9 |

| 2003 | 2 | 9 |

| 2004 | 0 | 10 |

| 2005 | 0 | 10 |

| 2006 | 1 | 7 |

| 2007 | 1 | 9 |

| 2008 | 1 | 13 |

* Data from the CF suicide surveillance system.

*2005 was the most recent year for which general population suicide rates were available at the time of this analysis. CF data is from CF suicide surveillance system (for numbers of suicides), the CF's Human Resources Management System (for the numbers of male Regular Force personnel per year), and Statistics Canada (for Canadian general population suicide rates).

Figure 3: CF Regular Force Male Suicide Rate, 1995-2008 (Compared to Canadian Male Suicide Rate)

Figure 3: CF Regular Force Male Suicide Rate, 1995-2008 (Compared to Canadian Male Suicide Rate) (Text equivalent)

| Year | CF Regular Force male suicide rate | Canadian male suicide rate, standardized to CF age distribution |

|---|---|---|

| 1995 | 19.17025 | 29.61394 |

| 1996 | 13.88696 | 28.1057 |

| 1997 | 23.61876 | 25.08217 |

| 1998 | 23.85978 | 25.95079 |

| 1999 | 18.82034 | 28.92871 |

| 2000 | 23.13744 | 24.6731 |

| 2001 | 19.60477 | 24.63639 |

| 2002 | 17.19986 | 22.89179 |

| 2003 | 16.74356 | 23.23118 |

| 2004 | 18.56286 | 21.80753 |

| 2005 | 18.63968 | 22.45744 |

| 2006 | 12.88945 | |

| 2007 | 16.32179 | |

| 2008 | 23.33555 |

* 2005 was the most recent year for which general population suicide rates were available at the time of this analysis. CF data is from CF suicide surveillance system (for numbers of suicides), the CF's Human Resources Management System (for the numbers of male Regular Force personnel per year), and Statistics Canada (for Canadian general population suicide rates).

Notwithstanding these facts, CF suicides regularly attract public attention, particularly when there is the perception that the suicide was related to a deployment or where it is believed that the CF should have prevented the suicide. Available data (see ANNEX C) shows that suicides are in fact no more likely in those with a history of deployment.

The CF is involved in many activities that have (or may have) suicide preventive effects, but its existing policy on suicide prevention (CFAO 19-44, ANNEX D) dates from 1996. Since that time there have been major changes in the CF’s operations, in the way it delivers mental health services, and in the body of knowledge on suicide prevention. The main focus of the current policy is education of members and leaders to increase their suicide awareness.

In the summer of 2009, the CF Surgeon General (Commodore Hans Jung) ordered the standing up of an Expert Panel on Suicide Prevention consisting of key CF health services personnel and representatives from some of our closest allies (ANNEX E). The stated objectives of the panel were to:

- Review the available scientific evidence, epidemiology and current best practices in the area of suicide prevention and surveillance; and

- Develop a series of recommendations for the management of suicide prevention and intervention in Canadian Forces that is balanced, feasible and logical given the available evidence (ANNEX F).

Suicide prevention recommendations from the Panel were not to be limited to educational approaches.

The Panel met in Halifax on 22 and 23 September 2009; the agenda is included as ANNEX G. CF experts made presentations on what the CF was doing with respect to suicide prevention in a given area (e.g., mass education). Potential opportunities for improvement were discussed, and formal recommendations were made. The CF’s international colleagues presented information on their nations’ suicide prevention programs. The strength of the CF’s approach was judged against best practices from the literature and the approaches used by its closest allies. Comparison of the CF’s approach against the suicide prevention strategy for Canada as a whole was not possible—Canada is one of the only industrialized nations that lacks a national suicide prevention strategy.

This report summarizes the Panel’s findings and recommendations.

1 In comparison, most conditions offer an opportunity for cure even when prevention fails (e.g., syphilis, lung cancer, etc.).

2 In fact, public health experts object to the use of the term “accident” in this context, preferring “car crashes,” which sends stronger message about their potential preventability.

3 Prevention of motor vehicle accidents has some similarities to suicide prevention: Both are complex problems requiring a complex series of interventions. Environmental interventions are important in each. Educational campaigns can play a facilitative role in road traffic accident prevention, but their independent contribution is uncertain and probably small (as it is for suicide prevention). An important difference between accident prevention and suicide prevention is that no one wants to have a car accident—this is an unplanned and undesired outcome. In contrast, truly suicidal individuals want to die and are capable to achieving their goal. This makes prevention a greater challenge.

4 There are so few suicides in women in the CF that is not appropriate to calculate and report their suicide rates.