Director of Defence Counsel Services Annual Report 2016-2017

Alternate Formats

National Defence

Defence Counsel Services

Asticou Centre, Block 300

241 Cité des Jeunes Blvd

Gatineau (Québec) Canada J8Y 6L2

Fax: (819) 997-6322

NDHQ Ottawa ON, K1A 0K2

12 May 2017

Major-General Cathcart, OMM, CD, Q.C.

Judge Advocate General

National Defence Headquarters

101 Colonel By Drive

Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0K2

Major-General Cathcart,

Pursuant to article 101.11(4) of the Queen`s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Forces, enclosed please find the annual report of the Director of Defence Counsel Services. The report covers the period from 1 April 2016 through 31 March 2017.

Yours sincerely,

D.K. Fullerton

Colonel

Director of Defence Counsel Services

Canada

Overview

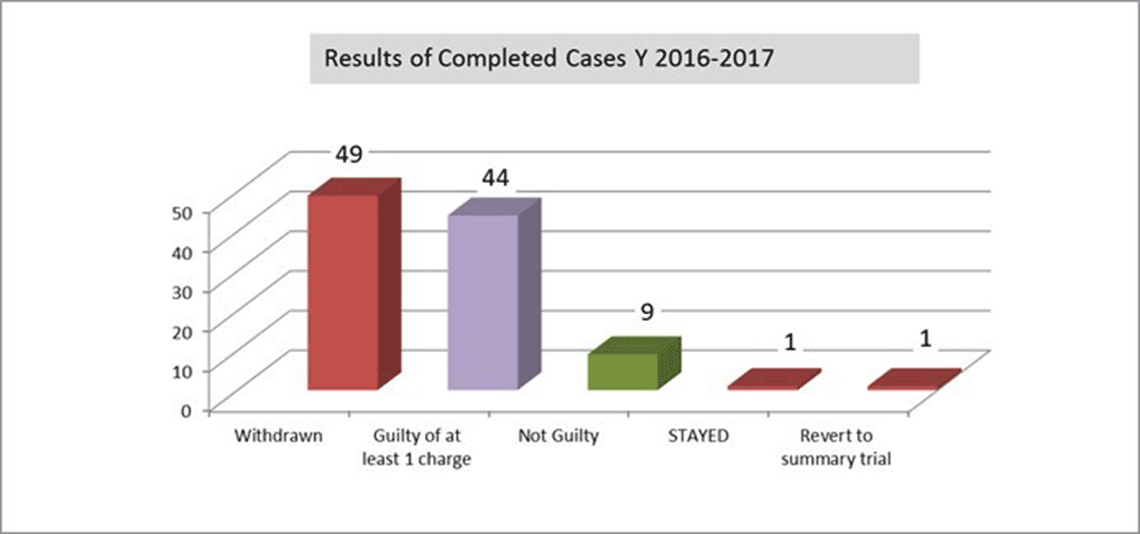

1. This report covers the period from 1 April 2016 to 31 March 2017. It is prepared in accordance with article 101.11(4) of the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Armed Forces, which sets out the legal services prescribed to be performed by the Director of Defence Counsel Services and requires that he report annually to the Judge Advocate General on the provision of legal services and the performance of other duties undertaken in furtherance of the Defence Counsel Services mandate. The director during this period was Colonel Fullerton.

Role of Defence Counsel Services

2. Under section 249.17 of the National Defence Act (NDA) individuals, whether civilian or military, who are “liable to be charged, dealt with and tried under the Code of Service Discipline” have the “right to be represented in the circumstances and in the manner prescribed in regulations.” Defence Counsel Services is the organization that is responsible for assisting individuals exercise these rights.

3. The Director of Defence Counsel Services is, under section 249.18 of the National Defence Act, appointed by the Minister of National Defence. Section 249.2 provides that the director acts under the “general supervision of the Judge Advocate General

” but makes provision for the JAG to exercise this role through “general instructions or guidelines in writing in respect of Defence Counsel Services.

” Subsection 249.2(3) places on the director the responsibility to ensure that general instructions or guidelines issued under this section are made available to the public. During this reporting period no general instructions were issued under this section.

4. The director “provides, and supervises and directs

” the provision of the legal services set out in Queen’s Regulations and Orders. These services may be divided into the categories of “legal advice

” where advice of a more summary nature is provided, often delivered as a result of calls to the duty counsel line, and “legal counsel

” which typically involves a more sustained solicitor-client relationship with assigned counsel and representation of an accused before a judge or military judge or the Court Martial Appeal Court or Supreme Court of Canada. Historically and occasionally, counsel have also appeared before a provincial Mental Health Review Board or the Federal Court.

5. Legal advice is provided in situations where:

- Members are the subject of investigations under the Code of Service Discipline, summary investigations, or boards of inquiry, often at the time when they are being asked to make a statement or otherwise conscripted against themselves;

- Members are arrested or detained, especially in the 48 hour period within which the custody review officer must make a decision as to the individual’s release from custody;

- Members are considering an election between a summary trial or a court martial;

- Members are seeking advice of a general nature in preparation for a hearing by summary trial; and

- Members are preparing a Request for Review of the finding and/or punishment(s) awarded to them at summary trial or are considering submitting such a request.

6. Legal representation is provided in situations where:

- Custody review officers decline to release arrested individuals, such that a pre-trial custody hearing before a military judge is required;

- There are reasonable grounds to believe that an accused is unfit to stand trial;

- Applications to refer charges to a court martial have been made against individuals;

- Individuals are appealing to the Court Martial Appeal Court or to the Supreme Court of Canada or have made an application for leave to appeal and the Appeal Committee, established in Queen’s Regulations and Orders, has approved representation at public expense; and

- In appeals by the Minister of National Defence to the Court Martial Appeal Court or the Supreme Court of Canada, in cases where members wish to be represented by Defence Counsel Services.

7. The statutory duties and functions of Defence Counsel Services must be exercised in a manner consistent with our constitutional and professional responsibilities to give precedence to the interests of clients. Where demands for legal services fall outside the Defence Counsel Services mandate the members are advised to seek civilian counsel at their own expense.

8. Defence Counsel Services does not have the mandate to represent accused at summary trial. The military justice system relies upon the unit legal advisor, generally a Deputy Judge Advocate, to provide advice to the chain of command on the propriety of charges and the conduct and legality of the summary trial process, all with a view to ensuring that the accused is treated in accordance with the rule of law.

The Organization, Administration And Personnel Of Defence Counsel Services

9. Throughout the reporting period, the organization has been situated in the Asticou Centre in Gatineau, Québec. The office has consisted of the Director, the Assistant Director, an appellate counsel at the rank of lieutenant-commander, and four regular force or reserve class B trial counsel at the rank of major/lieutenant-commander or captain. In March 2017, one regular force legal officer left the office upon retirement. We anticipate that his position will be filled in the coming posting season. Throughout this period there were four reserve force legal officers in practice at various locations in Canada, who assisted on matters part-time.

Administrative Support

10. Administrative support was provided by two clerical personnel occupying positions classified at the level of CR-3 and CR-5, as well as a paralegal providing legal research services and administrative support for courts martial and appeals. The CR-5 position has, during this period, been upgraded to AS-1 in order to make it consistent with the equivalent positions in the Directorate of Military Prosecutions and other divisions of the Office of the JAG and to better reflect the work performed. This reclassification was critical to eliminating what has served as a bar to retaining support staff in this position and to facilitating continuity of staffing at Defence Counsel Services.

Regular Force Resources

11. Defence Counsel Services are part of, and resourced through, the Office of the Judge Advocate General. This is also true of the prosecutions service. Throughout much of the past seven years, there has been a resource imbalance between the Canadian Military Prosecution Service and the Defence Counsel Services organizations. This has sometimes seen between five and eight regular force defence counsel litigating with up to sixteen regular force prosecutors. Neither reservists nor contracted civilian counsel represent a cost-effective way to address this imbalance of resources. A more careful alignment of resources between prosecution and defence functions would stabilize finances and create greater efficiency.

Reserve Counsel

12. At the commencement of the year there were a total of four reserve force defence counsel within the organization. During the year we lost two very experienced reservists to retirement and component transfer. We have recruited three others, who have various levels of experience within the military justice system, and we are in the process of recruiting another.

13. Our reserve force counsel are located throughout Canada; with two in Quebec, two in Ontario, and one in British Columbia. They are an important resource which has made, and continues to make, a significant contribution to the Defence Counsel Services mandate.

Funding

14. During this fiscal year the following funds were spent.

| Fund | Expenditure | |

|---|---|---|

| C125 | Contracting (Counsel, Experts, and Services) | $130,773.48 |

| L101 | Operating Expenditures | $149,579.85 |

| L111 | Civilian Pay and Allowances | $160,558.55 |

| L127 | Primary Res Pay, Allowance, Ops, Maintenance | $300,929.18 |

| Total | $741,841.06 | |

15. This amount is less than our budget allocation and reflects the fact that we did fewer courts martial than anticipated. With the recent nomination of an additional military judge, the recent decision of the Supreme Court of Canada in Jordan, the general increase in case-flow that we have recently observed and the increased disciplinary activity surrounding OP Honour, we anticipate that there will be more cases in the upcoming fiscal year and a greater requirement for funding.

16. Within Defence Counsel Services there are three methods of service delivery; regular force counsel, reserve force counsel and, pursuant to subsections 249.21(2) and (3), of the National Defence Act, contracted counsel. Regular force counsel are the most cost effective means of service delivery and do not require the expenditure of budgeted funds. The use of reserve force counsel and contracted lawyers come at a cost. Until this year we were largely able to restrict use of contracted counsel to situations of conflict of interest.

Training, Services, and Activities

Professional Development

17. The Federation of Law Societies’ National Criminal Law Program remains the primary source of training in criminal law for counsel with Defence Counsel Services. In July 2016, seven regular force counsel and four reserve force counsel attended this program, which was held in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. Additionally, in February 2017, most regular and reserve force counsel attended an annual one-day in-house training program in Ottawa which dealt with a variety of issues relevant to our mandate. Certain other courses sponsored by the Office of the JAG, the Canadian Bar Association, the Criminal Lawyers’ Association and the University of Sherbrooke were attended by individual counsel in order to meet their specific professional needs.

Duty Counsel Services

18. Legal advice is available twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, to members who are under investigation or in custody. Legal advice is typically provided through our duty counsel line, a toll-free number which is distributed throughout the Canadian Armed Forces and is available on our website or through the military police and other authorities likely to be involved in investigations and detentions under the Code of Service Discipline.

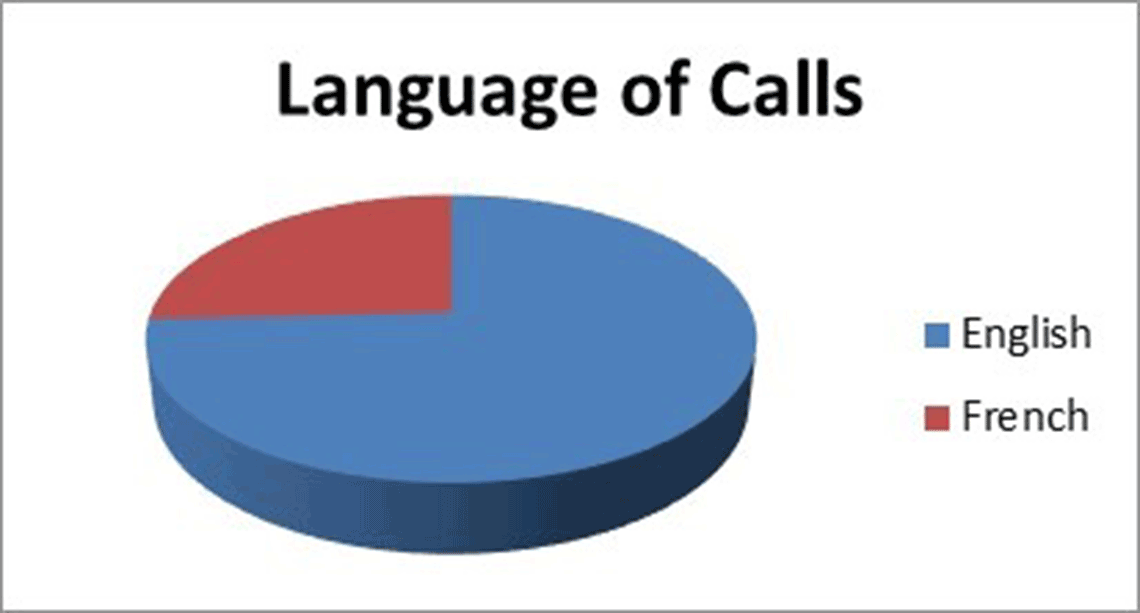

19. During the reporting period, Defence Counsel Services recorded 1,724 calls on the duty counsel line. Services are provided in both official languages. Service was provided in English on 1,266 calls and in French on 435 calls as depicted in the chart below.

Language of Calls: Pie chart illustrating 1,266 English calls in blue and 435 French calls in red.

20. The calls ranged in duration but, on average, lasted for approximately 15 minutes. Calls originated from every Canadian province and territory, as well as various locations outside of Canada from members serving abroad. The number of calls by location is illustrated in the graph below.

See below for description of graph.

| Location | Number of Calls |

|---|---|

| Alberta | 201 |

| British Columbia | 140 |

| Manitoba | 76 |

| New Brunswick | 136 |

| Newfoundland | 23 |

| Northwest Territories | 1 |

| Nova Scotia | 152 |

| Nunavut | 3 |

| Ontario | 560 |

| Prince Edward Island | 3 |

| Québec | 350 |

| Saskatchewan | 16 |

| Yukon Territories | 4 |

| Outside of Canada | 51 |

| N/A | 8 |

Court Martial Services

21. When facing court martial, accused persons have the right to be represented by lawyers from Defence Counsel Services at public expense, they may retain legal counsel at their own expense, or they may choose not to be represented by counsel.

22. During this reporting period Defence Counsel Services provided legal representation to accused persons in 200 files referred for penal prosecution. This number includes 79 cases which were still awaiting disposition at the commencement of the year and were carried over from the previous reporting year. It also includes 121 new cases which defence counsel were assigned during this reporting period. It does not include the nineteen clients being represented by defence counsel on appeal.

See below for description of graph.

| Number of Cases | |

|---|---|

| Carried forward | 79 |

| Assigned | 121 |

| Completed | 104 |

| Active Cases | 96 |

| Appeals | 19 |

| Total Cases | 200 |

23. Of these 200 client files open this year, 104 were completed during the reporting period. Of these, 49 had their charges withdrawn without trial but after assignment of counsel and some level of intervention by defence counsel ranging from simple requests for disclosure, to informal discussions with prosecution directed towards the issues of reasonable prospect of conviction or public interest in proceeding, to more formal motions or withdrawal before a military judge on the day of trial. One case was returned to the unit for summary trial.

24. Of the remaining 54 cases that proceeded to hearing, our records indicate that 19 cases went to trial for determination of the guilt of the accused. In 9 of these cases the accused was found not guilty of all charges and in 1 case a judicial stay was entered. In 44 cases the accused was either found guilty or plead guilty to at least one charge. Of the cases completed during this reporting period, approximately 55% of those who requested representation by Defence Counsel Services were able to move forward without any penal consequences.

See below for description of graph.

| Number of Cases | |

|---|---|

| Withdrawn | 49 |

| Guilty of at least 1 charge | 44 |

| Not Guilty | 9 |

| Stayed | 1 |

| Revert to summary trial | 1 |

25. Under the National Defence Act, the Director of Defence Counsel Services may hire civilian counsel to assist accused persons at public expense in cases where, having received a request for representation by Defence Counsel Services, no uniformed counsel are in a position to represent the particular individual. This occurs primarily as a result of a real or potential conflict of interest, often involving Defence Counsel Services’ representation of a co-accused. It may occur for other reasons as well. During this reporting period civilian counsel were hired by the director to represent accused persons in seven cases. Three of these cases proceeded to court martial for disposition and four cases were withdrawn by the prosecution prior to trial.

26. Additionally, two counsel retired during this reporting year upon reaching the age of 60. Each agreed to complete their representation of certain existing clients in their civilian capacity and at rates approximating those paid to reserve force defence counsel. A total of 8 files were addressed in this way. Some of these were subsequently withdrawn by the prosecution.

27. Lawyers from Defence Counsel Services focus on the interests of the individual represented. Nonetheless, some cases raised issues that are of interest to the system generally. This year one of these cases dealt with the issues flowing from the Supreme Court of Canada decision in Jordan, which considered the issue of trial within a reasonable time and established benchmarks of 18 months and 30 months for cases, depending on forum and whether they involved a preliminary enquiry.

28. The question of how Jordan would be applied within the military justice system was raised in the cases of LS Thiele and Pte Cubias-Gonzales. The military prosecution took the position that the constitutional benchmark within our system should be cognizant of the multi-stage process and numerous governmental actors through which a charge must pass and suggested that our referral process presented some similarities to a preliminary enquiry. They argued for a benchmark of 24 months. Counsel for the defence took the position that one of the traditional purposes of the military justice system has been to provide a forum in which charges can be dealt with more speedily than the civilian system. They argued for a benchmark of 12 months. The Military Judges in both cases affirmed 18 months as the appropriate presumptive ceiling within our system.

Appellate Services

29. Nineteen appeals were touched on at various points during this reporting period. This included 15 cases addressed before the Court Martial Appeal Court. It also included three appeals and one leave to appeal addressed before the Supreme Court of Canada. All appeals to the Supreme Court were filed by the prosecution. Of the appeals to the Court Martial Appeal Court, two were filed by the prosecution and thirteen appeals, previously approved by the Appeal Committee, were on behalf of the accused.

30. During this reporting period, only one member made, as allowed in regulations, a request to the Appeal Committee for representation at public expense on his appeal to the Court Martial Appeal Court of Canada. This request was approved.

R. v. Cawthorne

31. The Gagnon, Thibault and Cawthorne appeals to the Supreme Court of Canada were collectively dealt with in R. v. Cawthorne, [2016] 1 SCR 983. In each of these cases the member had been successful in the courts below and the Minister was appealing. The three accused brought motions to the Supreme Court of Canada challenging the constitutionality of sections 230.1 and 245(2) of the NDA which give the Minister of National Defence the right to appeal the decisions of a court martial or of the Court Martial Appeal Court.

32. The basis of this challenge was the submission that it is a principal of fundamental justice under section 7 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms that an accused has a right to a prosecutor who is objectively independent and that the Minister of National Defence did not meet this criteria as he was inherently a political actor and was not cloaked in the constitutional independence of the Attorney General.

33. The Supreme Court found that these provisions engaged section 7 of the Charter as the power of appeal might effect a deprivation of liberty. The Supreme Court also found that the principle that prosecutors must not act for improper purposes, such as purely partisan motives, is a principle of fundamental justice. However, the Supreme Court ruled that section 7 of the Charter does not provide any objective structural guarantees to protect prosecutorial independence and that resort to the doctrine of abuse of process was sufficient to address this issue where it arose.

34. The Supreme Court of Canada concluded that the Minister of National Defence is entitled to a strong presumption that he exercises prosecutorial discretion independently of partisan concerns. They found that the Minister's membership in Cabinet does not displace that presumption. They concluded that Parliament's conferral of authority on the Minister over appeals within the military justice system does not, therefore, violate section 7 of the Charter.

Charter challenge under s. 11(f)

35. On 3 June 2016, the Court Martial Appeal Court rendered its decision in R. v. Royes 2016 CMAC 1 and concluded that subsection 130(1)(a) of the National Defence Act, which allows all federal offences committed in Canada by those subject to the Code of Service Discipline to be tried by court martial, did not violate the right to be tried by jury guaranteed under subsection 11(f) of the Charter. Leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada was denied.

36. However, at the same time as R. v. Royes was unfolding, twelve cases (Wellwood et al. CMAC-571, CMAC-566, 567, 568, 574, 577, 578, 579, 580, 581, 583 and 584), were under reserve by a different panel of the Court Martial Appeal Court on this same constitutional issue. This second hearing was heard on 26 April 2016. This panel, consisting of Chief Justice Bell, Justice Cournoyer and Madame Justice Gleeson has not yet rendered its decision. This important decision has now been pending for over a year.

37. Further, on 23 February 2017, a third panel of the Court Martial Appeal Court was again seized of this same constitutional issue. This was in the case of Cpl Beaudry (CMAC-588). The appellant had argued that Royes should not be followed because it was manifestly wrong. The Court Martial Appeal Court in Royes had not identified, within its analysis, the purpose of subsection 11(f) of the Charter. This third panel, while expressly stating that they would continue to be seized of the case, decided to adjourn the matter until the decision in R. v. Wellwood et al. was rendered.

Other appellate cases

38. During this reporting period, two other appeals raised substantial questions respecting the administration of military law. These were the cases of Maj Wellwood (CMAC 571) and Cpl Golzari (CMAC 587).

39. In Wellwood, the issue is whether a superior officer obstructed a member of the military police in violation of section 129 of the Criminal Code of Canada. The superior officer was engaged in a military exercise when she was informed that one of her subordinates was or had been experiencing suicidal thoughts. She immediately took action to have that member located and assisted.

40. At the same time, the military police received a 911 call indicating that there was a member involved in the exercise who had called home while or after experiencing suicidal thoughts. The military police attended at the unit lines and were told that the chain of command was aware of the issue and were addressing it.

41. The attending military police member decided to take over management of the issue. A conflict of authority emerged between the major who wanted to remain in charge of the welfare of her subordinate and the military police corporal who viewed the welfare of the member as a police matter over which he had primary responsibility. The corporal perceived the officer as obstructing him in the performance of his duties and laid a criminal charge to that effect. The officer was convicted at trial. The matter was heard at the Court Martial Appeal Court on 26 April 2016. The decision of that court has now been pending for over a year.

42. In Golzari, the main issue was whether an off-duty soldier, who was denied access to the main gate of Canadian Force Base Kingston because he refused to say where he was going, had committed an act to the prejudice of good order and discipline contrary to s. 129 of the National Defence Act.

43. At trial, the accused was acquitted because the prosecution had failed to prove the member had a positive duty to provide destination details to the gate sentry. On appeal, the prosecution argued that proof of such duty was not required under section 129 of the National Defence Act.

44. The prosecution argued not only that proof of duty was not required under section 129 but further that, in most cases, proof of prejudice to good order and discipline is a matter of judicial notice, to be inferred by the military judge, based on his own knowledge of service life and that, as such, it requires no evidence. The matter was heard at the Court Martial Appeal Court on 23 February 2017 and a decision is now pending.

Legal Issues

Summary Trial of Persons with Mental Disorders

45. In previous annual reports we have discussed events and trends that are reflected during the reporting period and which should be brought to your attention in your capacity as superintendent of the military justice system. In the last annual report we raised the issue of the summary trial of persons whom the Presiding Officer had “reasonable grounds to believe

” were unfit to stand trial or were suffering from a mental disorder at the time of the commission of the alleged offence in contravention of subsections 163(1)(e) and 164(1)(e) of the National Defence Act. Over the past year there have been some significant positive developments in this respect, with local legal advisors appearing to provide advice consistent with these sections, and with one of the environmental commanders upholding, in a reasoned decision, a request for review on the basis that these provisions had not been adequately respected.

Court Martial Comprehensive Review

46. Over the past 7 years there has been some effort to promote the military justice system as both the “best system in the world

” and “equal to the civilian system

”. There are some practical and legal issues that can emerge within an expanded system that, outside of its judicial functions, is almost entirely contained within a single unit of the Canadian Armed Forces and is subject to centralized superintendence and command. During this period, uniformed lawyers within Defence Counsel Services, some with graduate degrees in studies directly focused on our military justice system, have incidentally performed a challenge function, raising systemic issues for resolution and litigation. I believe that in doing so they have made a significant contribution to the development of military justice and the rule of law in Canada.

47. During this reporting period the Court Martial Comprehensive Review has been unfolding within the Office of the Judge Advocate General. As Director of Defence Counsel Services I have been supportive of, and contributed to, that process. The public “conversations

” or “consultations

” that have taken place under the rubric of the Court Martial Comprehensive Review have opened the way to a somewhat more public dialogue about the military justice system. There are positive aspects to that.

48. I have twice written to the team responsible for this review. On 3 November 2016, I wrote in response to some of the materials posted on-line and some of the comments in the media. This letter was intended to provide a deeper understanding of the effectiveness, efficiency and fiscal responsibility of the Defence Counsel Services organization. On 13 February 2017, I wrote in response to an evolving set of questions posed by the review team about the role, responsibilities, challenges, method of service delivery, costs and trends in Defence Counsel Services. In this letter I highlighted some of the challenges that we experience in terms of costing and delay within the system.

49. Nonetheless, it has been difficult to understand the specific areas that were realistically being studied for change and how those changes might touch on the operation of Defence Counsel Services and impact on the defence of our clients. I do not know the methodology applied and what conclusions may have been arrived at in relation to our organization, or how the review team has understood or applied the information that we provided. More recently I have been assured that the report will be public and that we will have an opportunity to see and comment on the conclusions prior to recommendations being made.

50. If the report of the Court Martial Comprehensive Review is to be a reliable foundation for understanding Defence Counsel Services and assessing a need for changes, then there must be an interactive dialogue such that the Director Defence Counsel Services can read the observations, conclusions and any changes proposed and be given a reasonable opportunity for comments prior to any recommendations to the Minister.

Potential Audit by the Auditor General

51. In January of this year I met with a team from the Office of the Auditor General of Canada. They were exploring aspects of the Military Justice System with a view to a potentially more thorough audit, including of Defence Counsel Services. I provided an overview of Defence Counsel Services, our roles and responsibilities, how we interact with other parts of the Office of the JAG and other components of the military justice system, as well as the various processes with which we are involved. At this point I am unaware of whether that audit will take place and, if it does, what its scope might be.

52. If it proceeds, this audit might be a means of objectively considering some of the tensions, ambiguities and conflicts inherent within our governance structure and our system. This could include the very different characterizations of the JAG/Defence Counsel Services relationship which are found in the National Defence Act as opposed to the regulations, the tension points identified within the original Defence Counsel Services study, an analysis of resource distribution, a consideration of the role of the system against the capabilities of our whole of government partners and some consideration of roles and conflicts of interests.

Conclusion

53. Again it has been a challenging year for those within Defence Counsel Services. As in past years, the priority has remained the provision of legal advice and legal counsel to qualifying members of the military community who request our assistance. It is a privilege to assist these members. They are often facing a very difficult period within their lives and careers. Many continue with their careers and their contribution as dedicated and reliable members of the military community. For others, their charges are part of their transition from service to civilian life.

D.K. Fullerton

Colonel

Director of Defence Counsel Services

11 May 2017