Director of Military Prosecutions Annual Report 2015-16

Alternate Formats

Table of Content

- Letter from the Director of Military Prosecutions to the Judge Advocate General

- Message from the Director of Military Prosecutions

- Main Report

- Annex A: Director of Military Prosecutions Organizational Chart

- Annex B: Legal Training Statistics

- Annex C: Custody Review Hearings

- Annex D: Pre-Referral Delay

- Annex E: Court Martial Statistics

- Annex F: Court Martial Appeal Court Statistics

- Annex G: Supreme Court of Canada Statistics

Letter from the Director of Military Prosecutions to the Judge Advocate General

National Defence

Director of Military Prosecutions

Constitution Building

305 Rideau Street

Ottawa, Ontario

K1A 0K2

13 May 2016

Major General Blaise Cathcart, OMM, CD, Q.C.

Judge Advocate General

National Defence Headquarters

101 Colonel By Drive

Ottawa ON K1A 0K2

Major-General Cathcart,

Pursuant to article 110.11 of the Queen's Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Forces, I am pleased to present you with the 2015-2016 Annual Report of the Director of Military Prosecutions. The report covers the period from 1 April 2015 through 31 March 2016.

Yours sincerely,

Colonel B.W. MacGregor, CD

Director of Military Prosecutions

Canada

Message from the Director of Military Prosecutions

I am pleased to present the Director of Military Prosecutions (DMP) Annual Report for 2015-2016, my second since being appointed as DMP on 20 October 2014.

As provided for in the National Defence Act (NDA), the DMP is responsible for the preferral of charges and prosecution of cases at courts martial under the Code of Service Discipline (CSD); he acts as counsel for the Minister of National Defence in respect of appeals to the Court Martial Appeal Court (CMAC) and Supreme Court of Canada (SCC); and he provides legal advice to the Canadian Forces National Investigation Service (CFNIS). Bolstered by his security of tenure as set out in legislation, the DMP fulfils his legal mandate in a fair, impartial and independent manner.

Canadians expect disciplined military forces that comply with Canadian and international law. The maintenance of discipline in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) is the responsibility of the chain of command and is crucial for operational effectiveness and mission success. A disciplined military promotes a respectful work environment, supportive of diversity, in which members feel valued and are motivated to contribute to mission success and to reach their full potential. The military justice system is designed to support the maintenance of discipline and respect for the rule of law.

The 2015 Deschamps Report and Operation Honour have underlined the importance of ensuring that standards of behaviour are clearly communicated to CAF members and that those who fall short are held accountable in a manner that is fair, transparent and responsive. The military justice system in general and courts martial in particular, provide a mechanism for accountability that is consistent with those values. Military prosecutors fulfil a vital role in the military justice system by (among other things) determining when charges should be preferred and then prosecuting cases according to the law.

On 19 November 2015, the SCC reaffirmed the importance of the military justice system in Canada’s legal landscape when it rendered its decision in the cases of Second Lieutenant Moriarity et al v R; Private Alexandra Vezina v R; and Sergeant Damien Arsenault v R. This unanimous decision recognized that military prosecutions of those subject to the CSD, including the prosecution of offences set out in the Criminal Code, are consistent with the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (Charter). Nevertheless, a significant number of constitutional challenges to the military justice system continue to be raised by accused at the court martial, CMAC and SCC levels. We will continue to respond to those challenges, most significantly before the SCC in the cases of R v Ordinary Seaman Cawthorne and R v Warrant Officer Gagnon and Corporal Thibault. It promises to be another busy year.

In closing, I wish to thank all my military and civilian personnel for their professionalism, hard work, dedication and perseverance. I look forward to advancing our mission together in the year to come.

ORDO PER JUSTITIA

Colonel B.W. MacGregor, CD

Director of Military Prosecutions

Introduction

This report, covering the period of 1 April 2015 to 31 March 2016, is prepared in accordance with article 110.11 of the Queen's Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Forces (QR&O), which requires the DMP1 to report annually to the Judge Advocate General (JAG) on the execution of his duties and functions2. This report is organized into sections that will discuss the following:

- Mission and Vision

- Duties and Functions of the DMP

- Organizational Structure

- Training, Policy Development and Outreach

- Information Management and Technology

- Resourcing and Performance Measurement

- Financial Information

- Advancing the DMP’s Relationships with the CAF Chain of Command

- Advancing the DMP’s Relationships with Investigative Agencies

- Military Justice Proceedings

Our Mission

To provide competent, fair, swift and deployable prosecution services to the Canadian Armed Forces in Canada and overseas.

Our Vision

“ORDO PER JUSTITIA” or “DISCIPLINE THROUGH JUSTICE”. The DMP is a key player in the Canadian military justice system helping to promote respect for the law, as well as discipline, good order, high morale, esprit de corps, group cohesion and operational efficiency and capability.

DMP Vision: Discipline through Justice

See below for description of diagram.

- Objectives for all Canadian - Outcomes:

- Public Confidence in the Canadian Military Justice System.

- Support the maintenance of public trust in the CAF as a disciplined, efficient and capable armed force.

- Public confidence in the DMP.

- CAF Objectives - Outputs:

- Comply with CFNIS Service Level Agreements.

- Meet all demands for courts, advice, operational deployments andtraining.

- Support & comply with all government-wide initiatives, legal, ethical & moral standards.

- Internal Objectives - Processes:

- Maintain a productive work environment supporting independence, discretion, initiative, decisiveness and trust.

- Maintain efficiency, transparency & inclusiveness in the prosecution service.

- Enhance fairness and timeliness of military justice.

- Operate effectively within the statutory & regulatory framework of CMs.

- Conduct all activities within assigned resources.

- Maintain a productive work environment supporting independence, discretion, initiative, decisiveness and trust.

- People Objectives - Enablers:

- A fully staffed, healthy & highly motivated team.

- Continuously improve core competencies of lawyers, paralegals and support staff.

- Task-tailored, professional development for all DMP military & civilian personnel.

People objectives will affect Internal objectives, followed by CAF objectives and Objectives for all Canadians.

Duties and Functions of the DMP

The DMP is appointed by the Minister of National Defence. Section 165.11 of the NDA provides that the DMP is responsible for the preferring of all charges to be tried by court martial and for the conduct of all prosecutions at courts martial in Canada and abroad. The DMP also acts as counsel for the Minister of National Defence in respect of appeals before the CMAC and the SCC. Over the past year, military prosecutors have also represented the CAF at a custody review hearing and provided legal advice and training to the CFNIS.

In accordance with section 165.15 of the NDA, the DMP is assisted by officers from the Regular Force and the Reserve Force who are barristers or advocates. DMP can also count on a small but highly effective group of civilian support staff. Appointed for a four-year term, the DMP fulfils his mandate in a manner that is fair and impartial. Although the DMP acts under the general supervision of the JAG, he exercises his prosecutorial mandate independent of the chain of command. Those duties and functions, set out in the NDA, the QR&O, ministerial orders and other instruments, include:

- Reviewing all CSD charges referred to him through the CAF chain of command and determining whether:

- The charges or other charges founded on the evidence should be tried by court martial;

- The charges should be dealt with by an officer who has jurisdiction to try the accused by summary trial; or

- The charges should not be proceeded with.

- Conducting – within Canada or overseas – the prosecution of all charges tried by court martial.

- Acting as appellate counsel for the Minister of National Defence on all appeals from courts martial, to the CMAC and to the SCC.

- Acting as the representative of the CAF at all custody review hearings conducted before a military judge.

- Providing legal advice to military police personnel assigned to the CFNIS.

Organizational Structure

DMP and his staff of military prosecutors and civilian personnel are known collectively as the Canadian Military Prosecution Service (CMPS). The CMPS is organized regionally, and currently consists of:

- DMP headquarters at National Defence Headquarters in Ottawa consisting of the DMP, the Assistant Director of Military Prosecutions (ADMP, who is also responsible for the Eastern Region), one Deputy Director of Military Prosecutions (DDMP) responsible for the Atlantic and Central regions, an appellate counsel, a military prosecutor responsible for policy, training and communications, a legal advisor working directly with the CFNIS, a civilian paralegal, and one legal assistant;

- Regional Military Prosecutors’ (RMP) offices, with the exception of the Pacific regional office, have an establishment of two Regular Force military prosecutors and one legal assistant, located at:

- Halifax, Nova Scotia (Atlantic Region);

- Valcartier, Quebec (Eastern Region);

- Ottawa, Ontario (Central Region);

- Edmonton, Alberta (Western Region);

- Esquimalt, British Columbia (Pacific Region);3 and

- Nine Reserve Force military prosecutors located individually across Canada.

The DMP organization chart is provided at Annex A.

CMPS Personnel

Regular Force

During this reporting period, CMPS experienced a high turnover of military personnel and position changes at DMP headquarters and in regional offices. In our headquarters, our appellate counsel was promoted and appointed as a Deputy Director of Military Prosecutions (Atlantic and Central regions). While the appellate counsel position has remained vacant for approximately half the reporting period it is expected that a serving military prosecutor will be appointed as appellate counsel in the coming fiscal year. Given the intense appeal workload this reporting period, this absence in the appellate counsel position has put additional responsibilities onto CMPS prosecutors normally assigned to advancing trial work. With the dedicated team effort from our Regular and Reserve Force prosecutors supported by our able civilian staff, the appeal work did not suffer, however.

Our Edmonton office finished the year with no military prosecutors. This was caused by parental leave in September for one RMP and an unexpected release from the CAF for the other RMP. Our efforts in staffing the office with a Reserve Force member or through the posting of a Regular Force member were unsuccessful. This absence of Regular Force military prosecutors in the Edmonton office has resulted in an increased workload for the personnel in our Esquimalt office. It is expected that the Edmonton office will return to its full complement of two Regular Force military prosecutors in the fall of 2016. While this is not ideal, it is demonstrative of the limited resource capacities of the CMPS and of the Office of the JAG from which our Regular Force prosecutors are chosen.

The coming fiscal year will see the departure from CMPS of three experienced Regular Force military prosecutors. These three will be replaced by three junior legal officers who will have a greater need for mentorship from their more experienced colleagues in CMPS. It will also increase the need for training resources so that all military prosecutors can fulfil their duties professionally and in accordance with the Charter.

Reserve Force

Reserve Force military prosecutors had another eventful year in which they conducted courts martial and appeared before the SCC. This reporting period saw the recruitment of two Reserve Force military prosecutors, and another is proceeding through the recruiting process. These individuals bring a great deal of prosecutorial insight and experience to CMPS. It is expected, however, that required military training may place considerable demands on their time and may reduce their ability to take carriage of files in the short term.

Civilian Staff

We continue to feel the effect of budgetary restraint measures across the Department of National Defence (DND) implemented over the last several years that have reduced the civilian work force at DMP headquarters by 50%. One clerk position and one of two paralegal positions were eliminated in FY 12-13. The remaining paralegal is thus responsible for providing dedicated legal research support for the entire organization. Two experienced members of our civilian team will leave CMPS in the coming fiscal year: one due to retirement and one due to transfer to another position within DND. Contingency plans are being developed to address these departures but the absence of those members will be felt for some time. The DMP recognizes the added stress an ever increasing workload has caused his civilian staff and is making every effort to ensure that the staff maintains a healthy work life balance. The health and welfare of his civilian and military staff is an extremely high priority for the DMP.

Training

Regular Force military prosecutors, not unlike other legal officers, are posted from within the Office of the JAG to their prosecution position for a limited period of time, usually three to five years. As such, the training that they receive must support both their current employment as military prosecutors as well as their professional development as officers and military lawyers. The relative brevity of an officer’s posting with the CMPS requires a significant and ongoing organizational commitment to provide him or her with the formal training and practical experience necessary to develop the skills, knowledge and judgment essential in an effective military prosecutor.

Given the small size of the CMPS, much of the required training is provided by organizations external to the CAF. During the reporting period, military prosecutors participated in conferences and continuing legal education programs organized by the Directeur des poursuites criminelles et pénales, Federation of Law Societies of Canada, Ontario Crown Attorneys’ Association, Osgoode Professional Development, Barreau du Québec, International Association of Prosecutors, Advocates’ Society, Continuing Legal Education Society of British Columbia, Canadian Institute for the Administration of Justice, Nova Scotia Public Prosecution Service, Defence Public Affairs Learning Centre, University of Ottawa, and Ontario Police College. These programs benefited the CAF not only through the knowledge imparted and skills developed but also through the professional bonds developed by individual military prosecutors with their colleagues from the provincial and federal prosecution services.

Group photo of Canadian Military Prosecutions members at the 2016 Continuing Legal Education workshop.

CMPS held its annual Continuing Legal Education (CLE) workshop in March 2016 for its Regular Force and Reserve Force military prosecutors. This very valuable one-day workshop was followed by the annual JAG CLE workshop.

Military prosecutors also took part in a variety of professional development activities, including the Legal Officer Qualification Course. Finally, in order to maintain their readiness to deploy into a theatre of operations in support of the DMP’s mandate, military prosecutors conducted individual military skills training such as weapons familiarization and first aid training.

CMPS also provides support to the training activities of other CAF entities. During the reporting period, this support included the mentoring and supervision by military prosecutors of a number of junior military lawyers from the Office of the JAG, who completed a portion of their "on the job training" program by assisting in prosecutions at courts martial. Military prosecutors also provided military justice briefings to JAG legal officers, criminal law/military justice training to members of the CFNIS, and served as supervisors for law graduates articling with the Office of the JAG. Finally, legal officers serving outside the CMPS may, with the approval of their supervisor and the DMP, participate in courts martial as "second chair" prosecutors. The objective of this program is to contribute to the professional development of unit legal advisors as well as to improve the quality of prosecutions through greater local situational awareness.4 The reporting period saw two unit legal advisers participate in courts martial as second chairs. Feedback from the unit legal advisers and military prosecutors indicates that the program objectives were achieved: the prosecution benefitted from local insight and the unit legal advisers came away with a better understanding of the military justice system at the court martial level. These legal officers enjoy the same independent stature and protections of full-time military prosecutors while performing their particular prosecution duties.

Annex B provides additional information regarding the legal training received by CMPS personnel.

Policy Development

Military prosecutors also play a role in the development of Canadian military justice and criminal justice policy. The DMP publishes all policy directives governing prosecutions or other proceedings (such as custody review hearings) conducted by the CMPS. The Policy, Training and Communications position within the CMPS is a key part of ongoing efforts to review existing policies and in ensuring that the DMP’s guidance in prosecution-related matters is translated into new policies or other written instruments. A comprehensive examination is underway to determine what changes need to be made to DMP’s policies that relate to the prosecution of sexual offences. DMP has ordered this examination in light of the Deschamps Report, Operation Honour and the Mandate Letter from the Prime Minister of Canada to the Minister of National Defence, all of which have highlighted the need to ensure that the DND and CAF are fostering a workplace that is open, transparent, accountable and free from harassment and discrimination.

Outreach

F/P/T Heads of Prosecutions Committee

The DMP is a member of the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Heads of Prosecutions Committee, which brings together the respective leaders of Canada’s prosecution services to promote assistance and cooperation on operational issues. The Committee held two general meetings during the reporting period both of which the DMP personally attended. These meetings provided an invaluable opportunity for participants to discuss matters of common concern in the domain of criminal prosecutions and find opportunities for collaboration.

International Association of Prosecutors

The International Association of Prosecutors (IAP) is a non-governmental and non-political organization. It promotes the effective, fair, impartial, and efficient prosecution of criminal offences through the application of high standards and principles, including procedures to prevent or address miscarriages of justice. The IAP also promotes good relations between prosecution agencies and facilitates the exchange and dissemination among them of information, expertise and experience. The DMP and ADMP plan to participate in the IAP’s Twenty-First Annual Conference and General Meeting to be held in September 2016 and intend to take a lead role in the creation of a special interest group specifically dealing with military prosecutions.

CAF Chain of Command

The military justice system is designed to promote the operational effectiveness of the CAF by contributing to the maintenance of discipline, efficiency, and morale. It also ensures that justice is administered fairly and with respect for the rule of law. Operational effectiveness requires a workplace that is fair, respectful, inclusive and supportive of diversity. To meet these objectives, the chain of command must be effectively engaged.

The DMP recognizes the importance of maintaining collaborative relationships with the chain of command of the CAF, which concurrently respect the prosecutorial independence necessary for the prosecution of courts martial and appeals. Collaborative relationships with the chain of command ensure that both entities work together to strengthen discipline and operational efficiency through a robust military justice system.

During the reporting period, the DMP travelled extensively throughout Canada, observing court martial proceedings and meeting with senior members of the chain of command. As part of his effort to promote a collaborative relationship with the chain of command, the DMP gave a presentation to the CAF Discipline Advisory Council (DAC) in March 2016. The CAF DAC includes all of the senior Chief Warrant Officers and Chief Petty Officers First Class – the senior disciplinarians of the CAF. The CMPS command team and individual military prosecutors continue to engage with the chain of command to seek input, to inform and to encourage attendance at courts martial. Anecdotal evidence suggests that greater numbers of military personnel are attending courts martial and this is a positive indicator of transparency. Also, a member representing the chain of command is now systematically called as a witness at sentencing hearings to better inform the military judges of the effects that a particular offence has had on the discipline, morale and efficiency of the CAF.

Investigative Agencies

The DMP also recognizes the importance of maintaining relationships with investigative agencies, while at the same time respecting the independence of each organization. Good relationships with investigative agencies ensure that both the DMP and the agencies exercise their respective roles independently, but co-operatively, and help to maximize CMPS’ effectiveness and efficiency as a prosecution service.

RMPs provide investigation-related legal advice to CFNIS detachments across Canada. In addition, RMPs provide training to CFNIS investigators on military justice and developments in criminal law. At the headquarters level, the DMP has assigned a military prosecutor as legal advisor to the CFNIS command team in Ottawa.5

Information Management and Technology

JAGNet continues to be used as the main information management tool for electronic records in CMPS offices. JAGNet allows users to manage sensitive legal information securely. The goal of the JAGNet project is to introduce a suite of information management and information technology capabilities to enable the organization to properly manage legal cases and recorded information and to efficiently search, find, share and use legal information and knowledge, subject to such access restrictions as are necessary. Efforts continued during the reporting period to encourage all members of CMPS to better harness JAGNet’s full capability as a knowledge management tool. To that end, more legal content was added to the JAGNet DMP Portal.

Resourcing and Performance Measurement

As part of the Government of Canada, the DMP is accountable for maximizing efficiencies within available resources and reporting on the CMPS’s performance. The information and analysis provided below seek to describe, in the context of courts martial only, that performance in light of available resources.

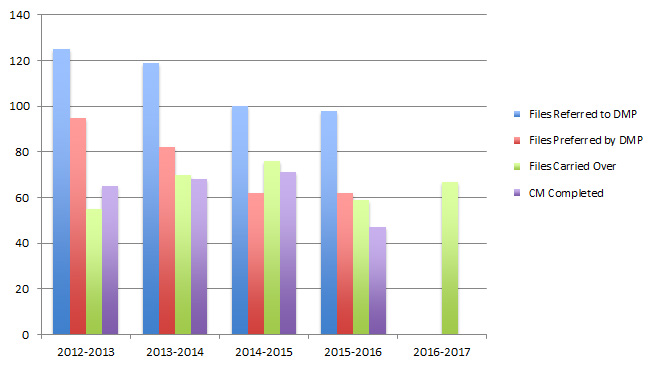

Graph 1 shows the relationship between the number of files received by the DMP during a given fiscal year, the total number of files that were preferred, the number of files carried over from the previous year and the number of courts martial that were completed during that year.

The number of completed courts martial in the reporting period decreased by 34% compared to the previous fiscal year (from 71 to 47), while the number of cases referred to the DMP was almost identical from the previous year (100 in 14/15 and 98 in 15/16) and the number of cases the DMP preferred to be tried by court martial increased by 6% (from 58 to 62). This decrease of completed courts martial appears to be related to the fact that there were only three sitting military judges out of an establishment of four for the entire reporting period. On 5 February 2015, Military Judge Colonel M.R. Gibson was appointed to the Ontario Superior Court of Justice and ceased to be a military judge. Another military judge has not been appointed to replace him as of the writing of this report some 15 months later. Also, as will be shown in subsequent graphs, the average length of contested courts martial more than doubled during the reporting year.6 Moreover, of the 67 files carried over to the next reporting year, six are contested courts martial that commenced but were not completed during the reporting period, totalling 59 sitting days during the reporting period.

Graph 1. See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | 2016-2017 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Files Referred to DMP | 125 | 119 | 100 | 98 | n/a |

| Files Preferred by DMP | 95 | 82 | 62 | 62 | n/a |

| Files Carried Over | 55 | 70 | 76 | 59 | 67 |

| CM Completed | 64 | 67 | 71 | 47 | n/a |

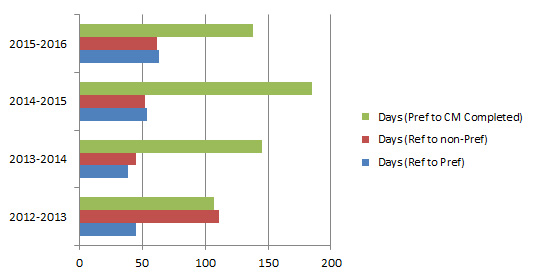

Graph 2 shows the number of working days taken by the CMPS to process a file.

The time to consider files at the DMP level has been consistent for the last several years. Approximately 60 working days are necessary for the DMP to process a file (determine whether to prefer charges or not) after it is referred.

The time between preferral and court martial has been increasing since 2012-2013. While it might appear that the time necessary to complete a court martial after charges were preferred decreased from 2014-2015 to 2015-2016, one must also consider the nature of the proceedings. In 2015-2016, only 23% of the 47 courts martial completed were contested (11 out of 47) as opposed to 48% of 71 courts martial (34 out of 71) for 2014-2015, and 36% of 67 courts martial (24 out of 67) for 2013-2014. The decreased number of military judges in the reporting period appears to have rendered more difficult the scheduling of contested (and therefore more time-consuming) trials.

Graph 2. See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days (Preferred to CM Completed | 107 | 145 | 185 | 138 |

| Days (Referred to non-Preferred) | 111 | 45 | 52 | 62 |

| Days (Referred to Preferred) | 45 | 39 | 54 | 63 |

Graph 3 shows the number of days that a court martial was sitting during a given reporting year in relation to the number of completed courts martial and, of these, the number that were contested courts martial.

The number of total sitting days for courts martial was less than the previous year (180 instead of 204, or 12% less). The number of sitting military judges may partly explain this decrease. It may also partly contribute to greater delays before courts martial can be scheduled, which leads to files being carried over into the next fiscal year. However, although there were 20% fewer military judges available to preside over courts martial during the reporting period,7 the total number of days they sat represents 88% of the total number of sitting days in the previous reporting period.8 As the next graphs will show, the complexity of contested cases has increased substantially during the reporting period, which would also account for the decrease of courts martial completed.

Graph 3. See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days in Court | 251 | 222 | 204 | 180 |

| CM Completed | 65 | 68 | 71 | 47 |

| Contested CM | 26 | 23 | 34 | 11 |

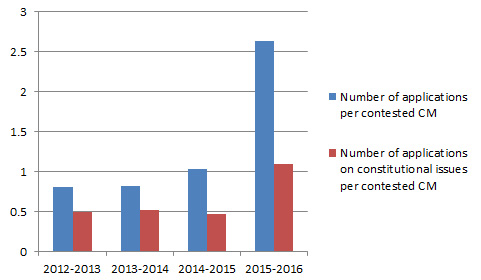

Graph 4 shows the average number of applications made by the accused in contested trials and the number of these applications that were of a constitutional nature.

There was a dramatic increase in the number of applications made by the accused in relation to contested trials. The number of applications increased from an average of one or less per trial for the past 3 years to an average of more than two per trial, one of which was on a constitutional issue. This increased the complexity and the workload of cases that could otherwise have been relatively simple.

Graph 4. See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of applications per contested CM | 0.8 | 0.8 | 1.02 | 2.6 |

| Number of applications on constitutional issues per contested CM | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.47 | 1.09 |

Graph 5 shows the average length of contested courts martial completed during a given reporting period.9

As a natural consequence of the increased number of applications, the average length of contested courts martial has doubled from the last reporting period. Also, on average, two or more military prosecutors were in court for the full duration of these courts martial because of the complexity of the applications, constitutional challenges and the experience level of the military prosecutors.

Graph 5. See table below for graph breakdown.

| 2012-2013 | 2013-2014 | 2014-2015 | 2015-2016 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average length (days) of Contested CM | 6.8 | 6.2 | 5.25 | 10.54 |

Conclusion on performance management and forecast

Between 2014-2015 and 2015-2016, approximately the same number of cases were referred to the DMP. The DMP preferred approximately the same number of cases to be tried by court martial. It also took approximately the same amount of time to prefer each case. However, the number of completed trials decreased by 34%. This seems to be in part explained by the increased number of days required to complete contested trials. The greater time required to complete contested trials appears to be related to the increase in the number of applications raised by the accused. It remains to be seen if the increase in the length of contested trials observed in the reporting period will continue in the next reporting period. If it does, and if the number of cases referred to the DMP remains constant, we can anticipate an increased backlog of cases, as well as increased delays between charges being laid and trials being completed. The significant increase in the proportion of cases completed consisting of guilty pleas instead of contested trials in the reporting period (as compared to previous years), leads to the reasonable assumption that a significant proportion of the cases carried over into the next reporting period will be contested, which will require even more time to complete. It might not be possible for military judges to further increase the number of days they can preside over cases in order to complete a greater number of cases. If the judicial vacancy is filled, we can anticipate that we will have to be ready to deal with an increased number of contested trials being heard in the next reporting period.

Operating Budget

The DMP’s budget is allocated primarily to operations: that is, to providing prosecution services to the CAF. As a result of the uncertainty inherent in predicting the number of prosecutions that will be conducted in a given year or where they may be held, it is difficult to accurately forecast expenditures.

FY 2015-2016 DMP Budget Summary

| Fund | Initial Allocation | Expenditures | Returned (Deficit) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L125: Crown Liabilities (Witness Expenses) | $130,000.00 | $65,810.68 | $64,189.32 |

| L101: Regular Force Operations & Maintenance | $247,800.00 | $167,781.33 | $80,018.67 |

| L111: Civilian Salary & Wages | $382,321.00 | $365,853.40 | $16,467.60 |

| L112: Reserve Force Pay | $167,200.00 | $86,519.55 | $80,680.45 |

| L115: Reserve Force Operations and Maintenance | $5,000.00 | $6,983.56 | ($1,983.56)10 |

| Totals | $932,321.00 | $692,948.52 | $239,372.48 |

The Military Justice System

The nature of the operational missions entrusted to the CAF requires the maintenance of a high degree of discipline among CAF members. Parliament and the SCC have long recognized the importance of a CSD supported by a separate military justice system to govern the conduct of individual soldiers, sailors and air force personnel, and to prescribe punishment for disciplinary breaches. In MacKay v the Queen11 and in R v Généreux,12 the SCC unequivocally upheld the need for military tribunals to exercise their jurisdiction in order to contribute to the maintenance of discipline, and associated military values, as a matter of vital importance to the integrity of the CAF as a national institution. These principles were unanimously reaffirmed by the SCC in 2015 in Second Lieutenant Moriarity et al v R; Private Alexandra Vezina v R; and Sergeant Damien Arsenault v R.13

In determining whether to prefer a matter for trial by court martial, military prosecutors must conduct a two-stage analysis. They must consider whether there is a reasonable prospect of conviction should the matter proceed to trial and whether the public interest requires that a prosecution be pursued.14 This policy is consistent with policies applied by Attorneys General throughout Canada and by prosecution agencies elsewhere in the Commonwealth. What sets the military justice system apart are some of the public interest factors that must be taken into account. These include:

- The likely effect on public confidence in military discipline or the administration of military justice;

- The prevalence of the alleged offence in the unit or military community at large and the need for general and specific deterrence; and

- The effect on the maintenance of good order and discipline in the Canadian Forces, including the likely impact, if any, on military operations.

Information relating to these and other public interest factors comes from the accused’s commanding officer (CO) when the CO sends the matter to his or her next superior officer in matters of discipline. That superior officer may also comment on public interest factors when referring the matter to the DMP.15

The consideration of uniquely military public interest factors allows the DMP to support the Minister of National Defence as he works with senior leaders of the CAF to “establish and maintain a workplace free from harassment and discrimination.

”16

Public interest factors in the military context may require prosecuting a person who was subject to the CSD at the time of the alleged offence but was released from the CAF thereafter. The jurisdiction of the military justice system extends to such persons.17 Prosecuting a former CAF member at court martial communicates to serving CAF members that they will be held accountable for their behaviour whether they are subsequently released from the CAF or not.

Courts martial, in contrast to civilian justice processes, are mobile. This allows courts martial to take place in or close to the military community that was most affected by the alleged offences. Courts martial are open to the public, resulting in increased transparency. Those most affected by an alleged offence can see for themselves that justice is being done.

Where the military justice system is called upon as a means of maintaining or reinforcing discipline, it does so with overlapping, but different objectives than the civilian criminal justice system seeks to achieve. It also has different requirements. First, those judging military personnel for alleged breaches of the CSD must not only have the requisite jurisdiction to deal with matters that threaten discipline and effectiveness, they must possess an understanding of the bases, need for, and the intricacies of military discipline. Second, as Colonel (Retired) Michael Gibson [now Justice Gibson of the Ontario Superior Court] noted in considering the goals and principles of sentencing under the CSD that have been enacted in a recent amendment to the NDA:

This represents a synthesis of the classic criminal law sentencing objectives of denunciation, general and specific deterrence, and rehabilitation and restitution, with those targeted at specifically military objectives, such as promoting a habit of obedience to lawful commands and orders, and the maintenance in a democratic state of public trust in the military as a disciplined armed force. This synthesis illustrates that military law has a more positive purpose than the general criminal law in seeking to mould and modify behaviour to the specific requirements of military service. Simply put, an effective military justice system, guided by the correct principles, is a prerequisite for the effective functioning of the armed forces of a modern democratic state governed by the rule of law. It is also key to ensuring compliance of states and their armed forces with the normative requirements of international human rights and international humanitarian law.18

As stated by Chief Justice Lamer in Généreux, the CSD “does not serve merely to regulate conduct that undermines such discipline and integrity. The Code serves a public function as well by punishing specific conduct which threatens public order and welfare

” and “recourse to the ordinary criminal courts would, as a general rule, be inadequate to serve the particular disciplinary needs of the military. There is thus a need for separate tribunals to enforce special disciplinary standards in the military.

”19

Criminal or fraudulent conduct, even when committed in circumstances that are not directly related to military duties, may have an impact on the standard of discipline, efficiency and morale in the CAF. For instance, the fact that a member of the military has committed an assault in a civil context may call into question that individual’s capacity to show discipline in a military environment and to respect military authorities. The fact that the offence has occurred outside a military context does not make it irrational to conclude that the prosecution of the offence is related to the discipline, efficiency and morale of the military.20

Canadian military doctrine identifies discipline as one of the essential components of the Canadian military ethos. Discipline is described as a key contributor to the instilling of shared values, the ability to cope with the demands of combat operations, self-assurance and resiliency in the face of adversity, and trust in leaders. It enables military individuals and units to succeed in missions where military skill alone could not.21 Some cases may seem minor until they are seen in their military context as violations of the four core Canadian military values which are: duty, loyalty, integrity, and courage. The value of integrity obliges CAF members to maintain the highest possible levels for honesty, uprightness of character, honour, and the adherence to ethical standards.22 The military justice system exists in part to address instances where it is alleged that CAF members did not discharge their obligations to the required level.

To these ends, the NDA creates a structure of military tribunals as the ultimate means of enforcing discipline. Among these tribunals are courts martial. Court martial decisions may be appealed to the CMAC, which is made up of civilian justices of provincial superior courts, the Federal Court and the Federal Court of Appeal.

Military Justice Proceedings

During the present reporting period, military prosecutors represented the Crown in several different types of judicial proceedings related to the military justice system. These proceedings included reviews of pre-trial custody, courts martial, and appeals from courts martial to the CMAC and SCC.23

Custody Reviews

Military judges are, in certain circumstances, required to review orders made to retain a CAF member in service custody. The DMP represents the CAF at such hearings. During the reporting period, military prosecutors appeared at one pre-trial custody review hearing,24 no 90-day review hearings25 and no Release Pending Appeal revocation hearings.26 Further information on custody reviews is provided at Annex C.

Courts Martial

During the reporting period, the DMP received 98 applications for disposal of charges from referral authorities. When an application for disposal is received, a military prosecutor is assigned to perform a review of the case. Following this review, charges are preferred to court martial, if warranted. During the reporting period, a decision not to prefer any charges to court martial was made in respect of 31 applications.27

Twenty-five applications for disposal of a charge had more than 90 days delay between the date the charge was laid and the date that the application was received by the DMP. Annex D provides additional information regarding the cases involving significant pre-referral delay.

During the reporting period, 47 individuals faced a total of 154 charges before courts martial, all of which were held in Canada.

Of the 47 courts martial held,28 40 trials were before a Standing Court Martial (SCM), composed of a military judge sitting alone. Seven trials were held before a General Court Martial (GCM), composed of five CAF members as triers of fact and a military judge responsible for making legal rulings and imposing sentence. In 41 of the trials, the accused was found guilty in respect of at least one charge. There was no finding of guilt in the remaining six cases. Annex E provides additional information regarding the charges tried and the results of each court martial.

While only one sentence may be passed on an offender at a court martial, a sentence may involve more than one punishment. The 41 sentences pronounced by courts martial during the reporting period involved a total of 69 punishments. A fine was the most common punishment, with 32 fines being imposed. Five punishments of imprisonment and four punishments of detention were also imposed by the courts. Of those 9 custodial punishments, two were suspended. This means, in the context of the CSD, that the offender does not have to serve out the sentence of imprisonment or detention as long as he or she remains of good behaviour during the period of the sentence.

CMPS counsel prosecute offences contrary to the NDA, including offences under section 130 of the NDA, which are based on federal statutes such as the Criminal Code and the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.29

A selection of courts martial in the following four broad areas is highlighted below:

- Drug Offences;

- Sexual Assault and Other Offences Against the Person;

- Fraud and Other Offences Against Property; and

- Offences Relating to Conduct.

The cases discussed below are a sampling of those dealt with by courts martial during the reporting period. These cases give a sense of the offenders and offences that were prosecuted, as well as the sentences that were pronounced.

Drug Offences

Like all Canadians, persons subject to the CSD are liable to prosecution for drug-related offences as provided in the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act. Unlike the civilian population, however, persons subject to the CSD are also liable to prosecution for drug use.30

R v Leading Seaman S.N. Trull31

In July 2014, Leading Seaman Trull was a reservist undergoing training and residing at Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Borden. During a search of her room by the military police, Leading Seaman Trull approached the military police and gave them a clear Ziploc bag, which contained a leafy marihuana-like substance, and stated, “I have pot here.

” Leading Seaman Trull had agreed to comply with the Canadian Forces Drug Control Program and Policy. Despite this knowledge, she used marihuana.

Leading Seaman Trull cooperated with the authorities investigating this matter. She pleaded guilty to one charge of conduct to the prejudice of good order and discipline, contrary to section 129 of the NDA for having used cannabis (marihuana) contrary to Article 20.04 of the QR&O. Following a joint submission, the SCM sentenced the offender to a fine in the amount of $500.

Sexual Assault and Other Offences against the Person

R v Officer Cadet J.C. Scott32

At the time of the offence, Officer Cadet Scott was a member of the Regular Force and a student at the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC) in Kingston. The complainant was also a member of the Regular Force and a student at RMC. On 14 March 2013, Officer Cadet Scott was at the Yeo Hall Officer Cadets’ mess, as was the complainant. Officer Cadet Scott attempted to wrap his arm around the complainant. He touched her hair as well as her back. On two occasions, he placed some paper money into her shirt. Both times, the complainant retrieved the bills and threw the money at Officer Cadet Scott, additionally giving him a strongly-worded rebuke. During one of these two exchanges Officer Cadet Scott grazed the complainant’s breast. The next day, Officer Cadet Scott arrived uninvited at the complainant’s room in the quarters at RMC. The complainant was alone in her room. Officer Cadet Scott lay down on the complainant’s bed and made sexually suggestive comments to her. He touched, without her consent, various parts of the complainant’s upper body including her hair and arms. The complainant was alarmed and went to her door to leave. Officer Cadet Scott also moved to the door and tried to convince the complainant to stay in the room. The complainant shoved Officer Cadet Scott away from her door and escaped to a fellow female officer cadet’s room.

Officer Cadet Scott pleaded guilty to one charge of assault under section 266 of the Criminal Code, an offence punishable under section 130 of the NDA; and two counts of conduct to the prejudice of good order and discipline under section 129 of the NDA. Following a joint submission on sentence, the SCM sentenced the offender to a severe reprimand and a fine in the amount of $2,000.

R v Sergeant R.D. Morgan33

At the time of the offences, Sergeant Morgan was a medical technician serving in the Regular Force. The events relating to the first charge occurred between 13 October and 21 December 2005, when the offender, then a Master Corporal, was deployed to Pakistan. He was the supervisor of a female Corporal who was a medical technician. During the deployment, he consistently flirted with the Corporal. He touched her several times, and on one occasion, he grabbed her buttocks over her combat clothing. The events relating to the second charge occurred between 2007 and 2008, when both Sergeant Morgan and a female Master Corporal (also a medical technician), were posted to 1 Canadian Field Hospital at CFB Petawawa. During that time, Sergeant Morgan repeatedly asked the Master Corporal out on dates even after she had clearly stated she was not interested in that type of relationship with him. On one occasion, Sergeant Morgan slapped the Master Corporal’s buttocks over her clothing. The events relating to the third charge occurred between 2010 and 2012, when Sergeant Morgan and another female medical technician (at the rank of Corporal), were posted to 1 Canadian Field Hospital. During this period, Sergeant Morgan repeatedly tried to establish a personal relationship with the Corporal, even after she had clearly stated she was not interested. On one occasion, in early 2012, Sergeant Morgan inserted his hand in the Corporal’s back pant pocket and squeezed her buttocks.

Sergeant Morgan pleaded guilty to three charges under section 129 of the NDA for conduct to the prejudice of good order and discipline, for having sexually harassed the two Corporals and the Master Corporal. After a joint submission, the SCM sentenced the offender to a severe reprimand and a fine of $2,000.

R v Master Corporal S.L. Wheaton34

The incident that gave rise to the offence occurred on the evening of 12 December 2013 in the Junior Ranks’ Mess at 14 Wing Greenwood where Master Corporal Wheaton was a supply technician. At one point during the evening, Master Corporal Wheaton was in a small storage room adjacent to the mess. A Corporal entered the room to gather her personal effects. Master Corporal Wheaton then made a number of flirtatious and sexualized comments to the Corporal. These comments made the Corporal very uncomfortable. She indicated that she was not interested by the invitation and left shortly thereafter.

Master Corporal Wheaton pleaded guilty to one charge under section 129 of the NDA for Conduct to the Prejudice of Good Order and Discipline for having harassed the Corporal contrary to Defence Administrative Orders and Directives (DAOD) 5012-0. Following a joint submission, the SCM sentenced the offender to a reprimand and a fine in the amount of $1,200.

R v Corporal J.A. Perry35

On the evening of 9 December 2013, both Corporal Perry and the victim (also a Corporal) were at CFB Petawawa and they had both consumed alcohol. During the evening, a fight between unidentified individuals occurred. Both Corporal Perry and the victim became involved in this incident, apparently attempting to break up the fight. Sometime after all parties involved in the altercation were separated, Corporal Perry approached the victim and punched him in the face. As a result, the victim was knocked to the floor and struck his head. As a direct consequence of the punch to his face, the victim sustained injuries including a cut and swelling to the upper lip, which required four stitches; and a cut to the back of the head, two centimetres long.

Corporal Perry pleaded guilty to one charge for fighting with a person subject to the CSD contrary to section 86 of NDA. Following a joint submission, the SCM sentenced the offender to detention for a period of 25 days.

Fraud and Other Offences against Property

R v Master Seaman R.J. Boire36

The events relating to the first charge occurred during Master Seaman Boire’s posting to CFB Petawawa, commencing in September 2009, where he had been posted on "Imposed Restriction" on the understanding that he had a dependant. Master Seaman Boire obtained separation expense benefits worth approximately $2,500 for every month of his posting to CFB Petawawa by submitting claims in which he certified and declared that he had a dependant, when he knew that this was not true. The events relating to the second charge occurred in the course of Master Seaman Boire’s later posting to CFB Borden, when he submitted two claims for separation expense benefits, in which he certified and declared that he had a dependant, knowing that this was not true. Personnel at CFB Borden conducted an administrative investigation into the eligibility of Master Seaman Boire to receive separation expense benefits, with the result that separation expense payments were ceased. He fraudulently received $48,512.01 in total. Master Seaman Boire was in the process of reimbursing the Crown from his pay at a rate of $250 per month. At the time of the court martial he still had approximately $40,836 remaining to pay back.

Master Seaman Boire pleaded guilty to two charges punishable under section 130 of the NDA for fraud, contrary to section 380(1) of the Criminal Code, for having claimed separation expense benefits without entitlement. The SCM sentenced the offender to imprisonment for a period of 60 days and a fine of $2,400. The SCM suspended the carrying into effect of the punishment of imprisonment.

R v Petty Officer 2nd Class R.K. Blackman37

At the time of the offences, Petty Officer 2nd Class Blackman was serving in the Reserve Force as a Resource Management Support (RMS) clerk, and residing in Ottawa. He completed training at CFB Petawawa from September 2009 until March 2010, in preparation for a deployment to Afghanistan. He was deployed in Afghanistan from April 2010 to August 2010. At that time of his pre-deployment training and his deployment in Afghanistan, he had custody of his teenaged daughter. Between October 2009 and April 2010, he submitted six Family Care Assistance (FCA) claims in which he claimed that he had paid for childcare for his daughter while he was away for training, knowing that this was not true. The value of those claims was over $l2,000. In addition, he forged and submitted a FCA Declaration.

Following a trial, a GCM found Petty Officer 2nd Class Blackman guilty of seven charges punishable under section 130 of the NDA: one charge of fraud contrary to subsection 380(1) of the Criminal Code; three charges of forgery contrary to section 367 of the Criminal Code and three charges of uttering a forged document contrary to subsection 368(1) of the Criminal Code. The offender was sentenced to imprisonment for a term of 45 days.

R v Master Corporal G.D. Jackson38

At the time of the offences, Master Corporal Jackson was a Mobile Support Equipment Operator, serving with the headquarters of the Canadian Special Operations Forces Command (CANSOFCOM) in Ottawa. On 19 July 2010, he was issued a DND credit card for the purchase of fuel in connection with his employment with CANSOFCOM. Master Corporal Jackson was informed that the DND credit card issued to him was for the sole use of fuel purchases as required in the course of his regular military duties. In January 2011, due to financial hardship, Master Corporal Jackson started using the DND credit card for personal fuel purchases. From then until September 2014, he used the DND credit card to purchase fuel for his personal vehicles. The total amount spent by Master Corporal Jackson for his personal benefit through the use of the DND credit card was approximately $20,000.

On 10 September 2014, Master Corporal Jackson voluntarily submitted a written statement to the military police regarding his misuse of the credit card and expressing remorse for his actions. He pleaded guilty to one charge under section 117(f) of the NDA for having committed an act of a fraudulent nature. Following a joint submission, the SCM sentenced the offender to detention for a period of 60 days.

R v Corporal D.R. Westcott39

At the time of the offences, Corporal Westcott was an aerospace telecommunication and information systems technician (ATIS Tech) at 14 Wing Greenwood, and a member of the Regular Force. As an ATIS Tech, Corporal Westcott’s responsibilities included the delivery, distribution, repair and installation of Hewlett Packard (HP) laptop computers. Between 1 October 2011 and 30 June 2012, Corporal Westcott stole 14 HP laptop computers from a secure storage space at 14 Wing. The military police initiated an investigation as a result of information received from HP to the effect that its customer services department had received calls for service to laptop computers that were identified as belonging to DND, but apparently owned by civilians who had nothing to do with DND. Through contact with one of those civilians, the military police learned that the HP laptops were obtained from a used computer retailer in Wolfville, Nova Scotia. The retailer reported that in 2011 and 2012, he purchased a number of HP laptops from Corporal Westcott. Corporal Westcott had no authority to sell or dispose of any of the HP laptops in question, all of which were public property. The total value of all the HP laptops improperly sold by Corporal Westcott was $13,790. Corporal Westcott received $2,800 from the improper sales.

Corporal Westcott pleaded guilty to one charge of stealing when entrusted, contrary to section 114 of the NDA; and one charge of improperly selling public property, contrary to section 116(a) of the NDA. Following a joint submission, the SCM sentenced the offender to imprisonment for a period of 60 days.

R v Leading Seaman K. N. Korolyk40

Leading Seaman Korolyk, a member of the Regular Force, was charged with one count under section 129 of the NDA for conduct to the prejudice of good order and discipline. Alternatively, she was also charged for an act of a fraudulent nature not particularly specified in sections 73 to 128 of the NDA contrary to section 117(f) of the NDA. The charges related to the accused’s alleged failure to report a domestic event relevant to her Post Living Differential allowance, though she had a duty to report that event in accordance with QR&O article 26.02. Leading Seaman Korolyk challenged the constitutionality of subsection 129(2) of the NDA, arguing that it created a non-rebuttable presumption that contravenes sections 7 and subsection 11(d) of the Charter. The Chief Military Judge found that subsection 129(2) of the NDA violated the presumption of innocence protected by subsection 11(d) of the Charter and that it could not be saved under section 1. He declared subsection 129(2) of the NDA to be void under section 52 of the Constitution Act, 1982. Leading Seaman Korolyk was found not guilty by the GCM of the remaining charge.

Offences Relating to Conduct

R v Master Warrant Officer D.R. Buckley41

At the time of the offence, Master Warrant Officer Buckley was serving as a RMS Clerk at 19 Wing/CFB Comox. On 11 September 2014, the 19 Wing Fitness Coordinator received an email from Master Warrant Officer Buckley recommending some amendments to the records relating to 19 Wing CAF members’ Fitness for Operational Requirements of CAF Employment (FORCE) test results. In that email, Master Warrant Officer Buckley asked that it be noted that she had passed the FORCE test on 8 September 2014. A check of the Human Resources Management System (HRMS) revealed that while there was an entry stating that Master Warrant Officer Buckley had passed the FORCE test on 8 September, this information had been entered in a way that was inconsistent with the usual practice. During a cautioned interview conducted by the CFNIS on 4 November 2014, she stated that she had made the HRMS entry that recorded her as having passed the FORCE test on 8 September 2014 using the HRMS password of a co-worker and knowing that the entry was false. The CFNIS investigation found that the most recent FORCE test form in Master Warrant Officer Buckley’s personnel file had numerous anomalies suggesting that the form had been altered. Master Warrant Officer Buckley admitted under caution to the CFNIS investigator that she had made the alterations.

Master Warrant Officer Buckley pleaded guilty to one charge of altering, with intent to deceive, a document made for a departmental purpose, contrary to section 125(c) of the NDA; and one charge of willfully making a false entry in a document made by her that was required for official purposes, contrary to section 125(a) of the NDA. The SCM sentenced the offender to a severe reprimand and a fine in the amount of $3,000.

R v Corporal M.L. Blenkhorn42

At the time of the offences, Corporal Blenkhorn was a member of the Regular Force, deployed on Operation CALUMET, as a member of Task Force El-Gorah in Sinai, Egypt. Task Force members were subject to Standing Order 2.00 which prohibited the consumption of alcohol during a member’s period of duty. On 26 March 2015, Corporal Blenkhorn was on a tour of the Holy Lands in Israel. Members who participated in this tour were required to attend a pre-tour briefing during which they were told that while on the tour they were on duty and that Standing Order 2.00 applied. During a scheduled stop in Nazareth, Israel, a tour guide saw Corporal Blenkhorn drinking beer. Corporal Blenkhorn acknowledged consuming alcohol on that day in contravention of Standing Order 2.00.

Corporal Blenkhorn pleaded guilty to one charge under section 129 of the NDA for having consumed alcohol, contrary to Standing Order 2.00. Following a joint submission, the SCM sentenced the offender to a fine in the amount of $750.

R v Second Lieutenant N. Soudri43

At the time of the offences, Second Lieutenant Soudri was a member of the Regular Force, serving in 439 Squadron, at CFB Bagotville. To justify his absences from his place of duty, he submitted to his unit nine attendance certificates purporting to show that he had accompanied his spouse to her appointments at a women’s health clinic, though he knew that those appointments never took place.

An SCM found Second Lieutenant Soudri guilty of one charge punishable under section 130 of the NDA for uttering forged documents contrary to section 368 of the Criminal Code. The SCM sentenced the offender to a severe reprimand and a fine in the amount of $2,000.

R v Ordinary Seaman T.A. Levi-Gould44

On 7 January 2014, following his period of Christmas leave, Ordinary Seaman Levi-Gould, a member of the Regular Force, failed to report for duty as required. A warrant for his arrest was issued by his commanding officer pursuant to subsection 157(1) of the NDA. On 1 April 2015, Ordinary Seaman Levi-Gould was arrested by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police for unrelated alleged criminal offences. He was released on conditions by a provincial court judge and was subsequently arrested by the military police at the courthouse. At court martial, Ordinary Seaman Levi-Gould argued that the provision of the NDA that allows a commanding officer to issue an arrest warrant was unconstitutional on the grounds that an arrest warrant must be authorized by a person capable of acting judicially and that commanding officers are incapable of acting judicially as they are neither impartial nor independent. He further argued that that his rights under sections 7 and 8 of the Charter were violated by the issuance of the arrest warrants against him and that his rights under section 9 were violated by his arrest and subsequent detention under the second of those warrants. He also asserted that his right to be tried within a reasonable time under section 11(b) of the Charter was breached.

The military judge determined that subsection 157(1) of the NDA does not provide any limit on when a commanding officer may exercise his or her power to authorize a warrant that may be executed in a dwelling house. In the military judge’s view, a commanding officer is so involved in the investigative functions performed by members of his unit that he or she cannot act in a judicial capacity when authorizing an arrest warrant under subsection 157(1). The military judge found that subsection 157(1) of the NDA violated sections 7 and 8 of the Charter and made a declaration of invalidity pursuant to subsection 52(1) of the Constitution Act, 1982. However, the SCM found reasonable reliance by government officials on subsection 157(1) of the NDA. The court found that officials had acted in good faith and without abusing their power under prevailing laws. The SCM held that laws must be given their full force and effect as long as they are not declared invalid. The court found no breach of Ordinary Seaman Levi-Gould’s constitutional rights and therefore found no reason to provide an individualized remedy to him in conjunction with the declaration of unconstitutionality. The accused was found guilty of desertion contrary to section 88 of the NDA, and disobedience of a lawful command contrary to section 83 of the NDA. He was sentenced to a severe reprimand.

Appeals to the Court Martial Appeal Court

During the reporting period, the CMAC rendered a decision on one appeal and one motion to quash. For appeals launched by the accused, DDCS provides legal representation, at no cost to CAF members, when authorized to do so by the Appeal Committee. Authorization is not required when the accused is the respondent.45 During the reporting period, two new applications to appeal were filed with the CMAC. Both appeals were initiated by DDCS counsel on behalf of CAF members convicted and sentenced by court martial. Twelve ongoing appeals were in the process of being dealt with at the end of the reporting period.

What follows is a summary of decisions from the CMAC during the reporting period.

R v Ordinary Seaman W.K. Cawthorne46

Child pornography was discovered on Ordinary Seaman Cawthorne’s cellular telephone by a CAF member who had found the phone and who had accessed its content in an attempt to find its owner. Ordinary Seaman Cawthorne admitted to possessing pornography, but denied that it was child pornography. The main issue before the GCM was whether Ordinary Seaman Cawthorne knowingly accessed and possessed child pornography. The GCM found him guilty of one count of possession of child pornography, an offence punishable under section 130 of the NDA, contrary to subsection 163.1(4) of the Criminal Code. He was also found guilty of one charge of accessing child pornography, an offence punishable under section 130 of the NDA, contrary to subsection 163.1(4.1) of the Criminal Code. The offender was sentenced to imprisonment for a period of 30 days. The military judge made an order under section 196.14 of the NDA for the taking of samples of bodily substances from the offender for the purpose of forensic DNA analysis; and an order under section 227.01 of the NDA for the offender to comply with the Sex Offender Information Registration Act for life.

Ordinary Seaman Cawthorne appealed to the CMAC on three issues. First, that the prosecution breached the rule in Browne v Dunn47, when, in closing argument and referring to the evidence that some pictures on the telephone had been deleted, submitted to the panel that “there is only one person who would be deleting them: Ordinary Seaman Cawthorne

” without having first cross-examined the appellant on these proposed inferences. The CMAC rejected this ground of appeal, concluding that the appellant was well aware of the prosecution’s approach through the testimony of the Crown’s expert witness and had the opportunity to make full answer and defence in relation to it. Consequently, there was no breach of the rule in Browne v Dunn; nor was there any trial unfairness to the accused. The second ground of appeal was that the images from Ordinary Seaman Cawthorne’s cellular telephone should have been excluded because they were obtained as a result of an unconstitutional search and seizure. Allowing the telephone search evidence, the CMAC determined that the military judge considered all of the relevant factors, made no unreasonable finding, and his decision deserved deference. The third ground of appeal was that the military judge erred by not granting a mistrial after Ordinary Seaman Cawthorne’s girlfriend responded to an improper question by the prosecutor before an objection to it was sustained. The majority of the CMAC held that a mistrial ought to have been granted on this basis. It allowed the appeal, set aside the findings of guilt, and directed that a new court martial be held on the two charges laid against Ordinary Seaman Cawthorne.

The DMP appealed the CMAC decision to the SCC and Ordinary Seaman Cawthorne has filed a motion to quash the appeal on the basis that subsection 245(2) of the NDA - the Minister of National Defence’s right to appeal to the SCC – is unconstitutional because the Minister is not an independent prosecutor. This appeal will be heard by the SCC on 25 April 2016.

R v Warrant Officer Gagnon and Corporal A.J.R. Thibault48

This case involves two military members who were charged with unrelated sexual assault offences. Warrant Officer Gagnon was found not guilty by a GCM of sexual assault under section 130 of the NDA, contrary to section 271 of the Criminal Code. The DMP appealed that decision to the CMAC on the basis that the military judge erred by leaving with the panel the defence of honest but mistaken belief in consent. Corporal Thibault was charged with sexual assault under section 130 of the NDA, contrary to section 271 of the Criminal Code. Both the accused and complainant were members of the CAF. The accused made a plea in bar of trial claiming that there was insufficient military nexus for the matter to be tried by a court martial. The Chief Military Judge granted that plea and terminated the proceedings. The DMP appealed that decision to the CMAC. At the CMAC, counsel for both Warrant Officer Gagnon and Corporal Thibault applied to have the appeals dismissed on constitutional grounds. They argued that the Minister’s power to appeal to the CMAC under section 230.1 of the NDA was unconstitutional because it exposed the accused persons to deprivations of their liberty in a manner that was not in accordance with the principle of fundamental justice that prosecutions (including appeals) can only be brought by an independent prosecutor.

The CMAC found that prosecutions can only be brought by an independent prosecutor, and that the Minister is not an independent prosecutor. The Court declared section 230.1 of the NDA to be unconstitutional, and of no force or effect. The court suspended this declaration of invalidity for a period of 6 months from the date of the decision, but declined to grant Warrant Officer Gagnon and Corporal Thibault’s applications to dismiss the appeals.

The DMP sought leave from the SCC to appeal the CMAC’s decision regarding section 230.1 of the NDA; a stay of execution of the CMAC’s declaration of invalidity; and permission to have this case heard by the SCC along with the appeal in R v Cawthorne. The SCC granted leave to appeal R v Gagnon and Thibault and gave permission for a joint hearing with R v Cawthorne.

Upcoming CMAC Appeals

R v Master Corporal D.D. Royes49

Master Corporal Royes was tried and convicted of sexual assault by a SCM.50 He was sentenced to a term of imprisonment of 36 months.51 His application for release pending appeal was allowed. He appealed the legality of the guilty verdict as well as the military judge’s decision to dismiss his motion for an order striking down paragraph 130(1)(a) of the NDA on the basis that it violates section 7 of the Charter. At the hearing of the appeal, the CMAC was informed that Master Corporal Royes had not served a Notice of Constitutional Question pursuant to rule 11.1 of the CMAC Rules.52 Since this was a prerequisite of the CMAC’s jurisdiction over the constitutional issue and given the importance of the question to the appellant who had been sentenced to 36 months of imprisonment, the appeal was adjourned on the constitutional issue. Following the adjournment, the Court granted the accused’s motion to have the constitutional issue determined without a hearing because it raised the same issues as the SCC case in Moriarity. On 30 October 2014, The CMAC unanimously dismissed all grounds of appeal raised by the appellant other than the question of the constitutionality of section 130(1)(a) of the NDA. Following the SCC decision in Moriarity, the appellant sought and received permission from the CMAC to raise a new ground of appeal: the alleged violation by subsection 130(1)(a) of the NDA, of subsection 11(f) of the Charter. The hearing of this issue before the CMAC took place on 22 January 2016. In the next reporting period, the CMAC is expected to render a decision on that constitutional issue.

Cases related to section 11(f) of the Charter

On 26-27 April 2016, another panel of the CMAC will hear arguments on the constitutionality of section 130(1)(a) of the NDA vis-à-vis section 11(f) of the Charter in the cases of Petty Officer Second Class R.K. Blackman, Warrant Officer Gagnon, Corporal Thibault, Private J.-C. Déry, Second Lieutenant N. Soudri, Lieutenant(Navy) G.M. Klein, Corporal C. Nadeau-Dion, Corporal F.P. Pfahl, Petty Officer Second Class J.K. Wilks and Major B.M. Wellwood. In the case of Major Wellwood, the CMAC will also be asked to consider alleged errors in the instruction to the panel by the presiding military judge.

Annex F provides additional information regarding appeals to the CMAC.53

Appeals to the Supreme Court of Canada

R v Moriarity

During the reporting period, the SCC rendered its landmark decision in Second Lieutenant Moriarity et al v R; Private Alexandra Vezina v R; and Sergeant Damien Arsenault v R.54 Second Lieutenant Moriarity, Private Hannah, Private Vezina, and Sergeant Arsenault were each convicted at courts martial of having committed offences contrary to one or more of the Criminal Code, the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act and the Food and Drugs Act, punishable under section 130(1)(a) of the NDA. Section 130(1)(a) of the NDA incorporates all offences under the Criminal Code or any other Act of Parliament into the military justice system as "service offences" triable within the military justice system.

All four members appealed to the CMAC on constitutional grounds, arguing that subsection 130(1)(a) of the NDA was overbroad to achieve its purpose of enforcing discipline, efficiency, and morale in that it potentially incorporates into the CSD civilian offences committed in circumstances unrelated to military service. The CMAC determined that subsection 130(1)(a) of the NDA was not overbroad but that a military nexus test was a necessary component of that section. The convictions were upheld and the accused appealed to the SCC.

The SCC unanimously dismissed all four appeals and held that there is no requirement for a military nexus in order for section 130(1)(a) of the NDA to be consistent with the Charter. The Court found that the purpose of the military justice system is “to provide processes that would assure the maintenance of discipline, efficiency and morale of the military,

” and that criminal conduct “even when committed in circumstances that are not directly related to military duties, may have an impact on the standard of discipline, efficiency and morale.

” The behaviour of members of the military relates to discipline, efficiency and morale even when they are not on duty, in uniform, or on a military base. In its ruling in this case, the SCC has been characterized as having “repelled a sweeping Charter attack on the military justice system in a landmark decision that rejects a constitutional challenge for overbreadth.

”55

Upcoming Appeals to the SCC

As indicated above, during the reporting period, the SCC granted leave to appeal in R v Warrant Officer Gagnon and Corporal A.J.R. Thibault.56 R v Ordinary Seaman W.K. Cawthorne is an appeal as of right.57 Both cases are scheduled to be heard by the SCC on 25 April 2016.

Annex G provides additional information regarding appeals to the SCC.58

Footnotes

1 Colonel B.W. MacGregor was appointed by the Minister of National Defence on 20 October 2014 to be the DMP for a four-year term.

2 Previous DMP Annual Reports, along with DMP Policy Directives and other information can be found at the DMP website.

3 The DDMP (Western and Pacific) is currently co-located with the RMP Pacific.

4 The DMP and the Deputy Judge Advocate General Regional Services have an agreement whereby unit legal advisors may participate as second chairs to RMPs in preparation for and conduct of courts martial. Please see DMP Policy Directive #: 009/00 for further information.

5 The provision of legal services by the military prosecutor assigned as CFNIS Legal Advisor is governed by a letter of agreement dated 30 September 2013, signed by the DMP and the Canadian Forces Provost Marshal.

6 For the purpose of this report, ‘contested courts martial’ are those where the accused entered a plea of non-guilty, and ‘non-contested’ ones are those where the accused entered a guilty plea. It should be noted, however, that in a number of ‘non-contested’ trials, the accused raised pre-trial motions prior to eventually pleading guilty, for instance, challenging the constitutionality of searches and seizures, or of the provisions under which they were charged. There were four such applications in three cases during the reporting period (in 8% of the 36 non-contested trials). In six non-contested cases (17%), there was no joint submission on sentence. Overall, 22% of non-contested trials featured contested issues requiring a military judge to hear arguments before making a decision.

7 Considering the number of months there was a vacancy on the military judges’ establishment, there was an average of 3.75 judges available in 2014-2015 instead of 3 in 2015-2016.

8 Even though the total number of sitting days decreased slightly, military judges spent on average more time in court in the reporting period than they did in the previous one. Given the average number of military judges available during a given reporting period, military judges sat on average 60 days in 2015-2016 instead of 54.4 days in 2014-2015, an increase of 10%.

9 These numbers include all days of courts martial completed in the reporting period, even if some of those days occurred in previous reporting periods.

10 This deficit was offset by funds from L101: Regular Force Operations & Maintenance.

11 MacKay v the Queen, [1980] 2 SCR 370 at paras 48 and 49.

12 R v Généreux, [1992] 1 SCR 259 at para 50.

13 R v Moriarity, 2015 SCC 55, [2015] 3 SCR 485.

14 For further information, please refer to DMP Policy Directive Directive #: 003/00 Post-Charge Review.

15 Supra note 9, at para 19.

16 Minister of National Defence Mandate Letter from the Rt. Hon. Justin Trudeau, P.C., M.P., Prime Minister of Canada.

17 NDA, ss 60 and 69.

18 Michael Gibson, "International Human Rights Law and the Administration of Justice through Military Tribunals: Preserving Utility while Precluding Impunity" (2008) 4: 1 Intl L and Relations 1, at 12.

19 R v Généreux, [1992] 1 SCR 259 at 281 and 293.

20 R v Moriarity, 2015 SCC 55 at para 52.

21 Canada, Department of National Defence, "Canadian Military Doctrine," by the Chief of the Defence Staff, Ottawa: 2011-09 [Canadian Military Doctrine]. See, in particular, Ch. 2 "Generation and Application of Military Power" and Ch. 4 "The Canadian Forces" at 4-5.

22 Ibid.