Operation Market Garden: 437 Squadron’s baptism of fire

News Article / August 30, 2019

Click on the photo under “Image Gallery” to see more photos.

By Major (retired) William March

2019 marks the 75th anniversary of Operation Market Garden, the audacious and ultimately unsuccessful push

to secure bridges over several rivers in Holland and thus open a corridor through which the Allied ground forces

could sweep, with the goal of ending the war by Christmas 1944.

In May 1942, as part of updating the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan (BCATP) agreement, Canada and England had agreed, under Article XV, that the Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF) could form 35 squadrons overseas.

By May 1944, there were still three squadrons yet to be established and the British Air Ministry urged Canada to commit these squadrons to No. 6 (RCAF) Group within Bomber Command. Senior Canadian air officers, conscious of the high level of casualties within bomber units felt that Canada’s current commitment of 15 heavy-bomber squadrons was enough. They recommended the formation of a light-bomber squadron and two transport squadrons instead. Ottawa agreed and two transport squadrons (435 and 436 Squadrons) were established in India. As the British had sufficient light-bomber squadrons to meet their requirements in the European Theatre, it was mutually agreed upon to form a third transport squadron: 437.

437 Squadron, stood up on September 14, 1944, at RAF Station Blakehill Farm, Wiltshire, was part of No. 46 Group, Royal Air Force (RAF) Transport Command. Wing Commander John Alexander “Jack” Sproule, a Canadian who had joined the RAF in 1937, was selected at its first commanding officer. He came to the squadron with a wealth of experience, having completed a tour with Bomber Command, served as a BCATP navigation instructor and returned to Europe flying Dakotas with, and eventually commanding, an RAF transport squadron. He would need every bit of his hard-gained experience as 437 Squadron was to begin flying operations in three days.

Fortunately for Wing Commander Sproule he got some unexpected help. Due to a reorganization resulting in the downsizing of RAF transport squadrons, 13 RCAF crews already serving in Transport Command were available and all were transferred to 437. The first nine crews arrived at Blakehill Farm just in time to take part in Operation Market Garden, the combined Allied airborne and armoured thrust into occupied Holland.

On September 17, Wing Commander Sproule, his nine Canadian crews and two other crews seconded to him, took to the air towing Horsa gliders containing personnel and equipment belonging to the 1st British Airborne Division. The drop zone was near Arnhem and they encountered little opposition, except for some light flak. All of the 437 Squadron Dakotas returned safely. Over the next several days, the Canadians crews continued to delivered reinforcements and supplies to the increasing hard-pressed airborne forces on the ground. As German resistance stiffened on the ground, so too did the gauntlet of flak that the transport aircraft confronted during each and every mission. Nevertheless, except for a few additional holes in their aircraft, the Huskies made it safely back to their home field.

The squadron’s luck ran out on September 21. Ten 437 Squadron crews joined the re-supply armada that day and the Luftwaffe finally managed to break through the Allied fighters. They had a field day amongst the slow, unarmed transport aircraft. And then there was the flak—made even more deadly as the Germans had overrun much of the anticipated re-supply area. One soldier on the ground wrote that . . .

The cold-blooded pluck and heroism of the pilots was incredible. They came in in their lumbering . . . machines at fifteen hundred feet searching for our position . . . The German gunners were firing at point-blank range, and the supply planes were more or less sitting targets . . . How those pilots could have gone into it with their eyes open is beyond my imagination . . . They came along in the unarmed, slow twin-engined Dakotas as regular as clockwork. The greatest tragedy of all, I think, is that hardly any of the supplies reached us.

Within minutes of arriving at the drop zone, four 437 Squadron Dakotas were shot down—the thick black smoke rising from the burning wreckage adding to the grotesque forest of similar pillars marking the loss of other Allied aircraft.

Heroism abounded that day as exemplified by Flying Officer Gerald P. Hagerman (Mallorytown, Ontario). At the controls of Dakota KG376, he made not one but two passes over the drop zone, trying with every ounce of his being to put the supply panniers (heavy wicker baskets containing an average load of 350 pounds or 159 kilograms) in the right place. His mission, accomplished he headed for England and was attacked by six enemy fighters. His skillful maneuvering could not prevent mortal damage to the Dakota, but it did buy time for his crew to bail out. Once he was sure that they had left the aircraft, Flying Officer Hagerman took to his parachute and landed within Allied lines. For his actions that day he was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC).

All told, five 437 Squadron aircraft were either shot down or crashed due to battle damage. Eight members of the squadron were killed: Flight Lieutenant Robert Wilfred Alexander (pilot, 24, Norwich, Ontario); Flying Officers William Stewart McLintock (navigator, 21, Regina, Saskatchewan); Charles Herbert Cressman (pilot, 27, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan); John Spencer Blair (pilot, 27, Lucan, Ontario); Paul N. Steffin (navigator, 28, Eastgate, Alberta); Pilot Officers Thomas John Brennan (wireless operator, 30, Coleman, Alberta); Michael Stanley Reece Mahon (pilot, 28, Barbados, British West Indies); and Flight Sergeant John Charles Hackett (RAF).

Many more were wounded or wound up as “guests” of the Germans.

There was little time to mourn.

The following day was spent absorbing additional crews and dealing with the visit of a Very Important Person (VIP), but on September 23, the final day of the battle, 437 Squadron aircraft were in the air again. They faced no enemy fighters this time, but the flak was just as deadly and Dakota KB315 failed to return. Killed were: Flying Officers William Richard Paget (pilot, 21, Shelburne, Ontario); Donald Lawrence Jack (pilot, 21, Westmount, Quebec); Warrant Officer Roy Irving Pinner (wireless operator, 25, Fort William, Ontario); Flight Sergeant Denis Joseph O’Sullivan (navigator, 28, Montreal, Quebec) and three Royal Air Service Corps dispatchers—Corporal Thomas Henry Baxter and Drivers Frederick Walter Beardsley and Paul Williams. The dispatchers were responsible for securing the supplies and then pushing them out of the aircraft over the target.

In less than a week of existence, the Huskys had lost 12 squadron members.

The vital work of transport squadrons is rarely acknowledged in the annuals of military history as the vast majority of their time is spent on “routine” supply work. But when called upon, their crews are willing to make the ultimate sacrifice supporting the soldiers on the ground, doing their utmost to deliver their loads.

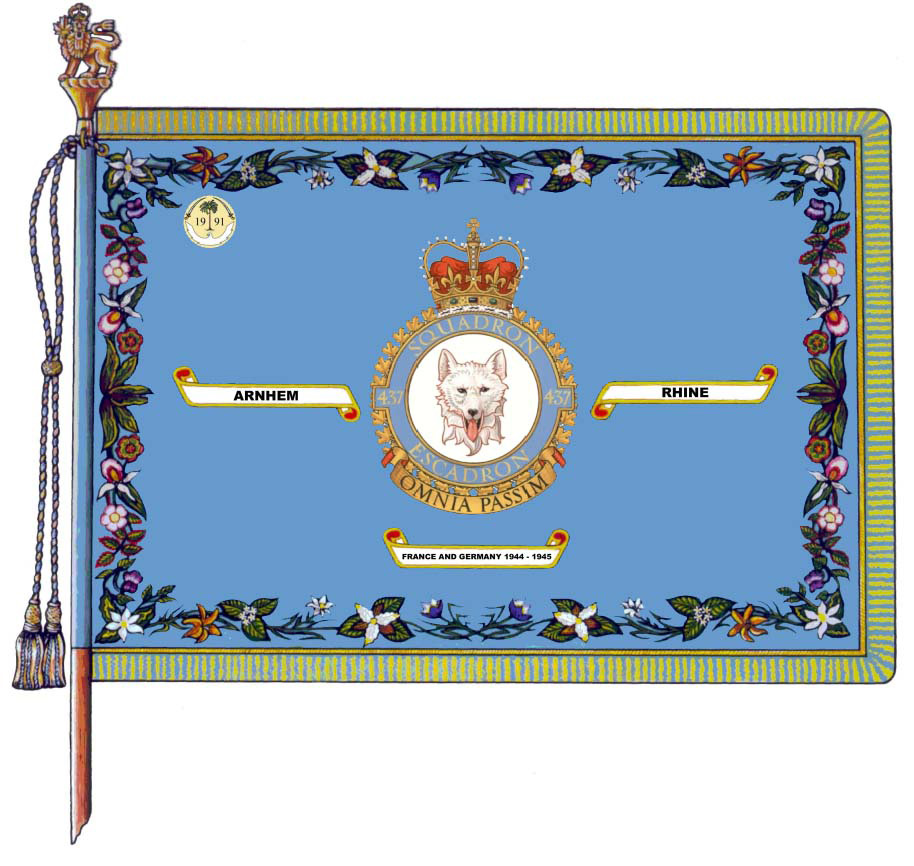

For 437 Squadron, the “Arnhem” Battle Honour on the squadron standard is reflective of its motto "Omnia passim"—Anything, Anywhere—regardless of the obstacles in its way.