The RCAF in the Korean War

News Article / June 25, 2020

Click on the photo under “Image Gallery” to see more photos.

RCAF Public Affairs

The North Korean Army crossed into South Korea on June 25, 1950. The resulting drive forced South Korean and United States troops into a small corner of the Korean Peninsula that became known as the Pusan Perimeter. The United Nations responded to the attack and appointed the US as the organizing nation under General Douglas MacArthur.

Over the three-year combat period and the subsequent peacekeeping era until 1957 (for Canada), some 27,000 Canadian personnel—23,000 Canadian Army, 3,000 Royal Canadian Navy (RCN), and 1,000 Royal Canadian Air Force (RCAF)—and other Canadian aviators, contributed to the action.

About 800 RCAF personnel were from 426 (Transport) Squadron, at RCAF Station Lachine, Québec; the remainder were fighter pilots; flight nurses; supply, technical, and photo intelligence personnel; and a judge advocate general. Airmen from the RCN and the Canadian Army also participated, as did civilian flight crews from Canadian Pacific Airlines (CPA). Some Canadians joined the US Army or the US Air Force (USAF) directly.

Canada’s ongoing commitments to the North American Treaty Organization (NATO) included 16 day-fighter squadrons in Europe, flying the Canadian-built version of the F-86E Sabre jet. Other wings were established and equipped in Germany and France in the early 1950s. In addition, nine squadrons were re-equipped with the Canadian-designed and -built CF-100 Canuck all-weather fighter interceptor.

April 1953 saw the C-119 Flying Boxcar added to the RCAF transport fleet. In May, the de Havilland Comet jet airliner and the Canadian version of the T-33 Silver Star trainer, which first flew in late 1952, were added to the RCAF inventory.

It was a busy time for the RCAF, and squadron-level participation in the Korean War—other than airlift capabilities provided by 426 Squadron—was not feasible. Still, Canada contributed a significant number of airmen and airwomen to the Korean air war effort.

Canadian-built aircraft in the Korean War included the Canadair North Stars flown by 426 Squadron; hundreds of de Havilland Canada DHC-2 Beavers in service with the US Army (known there as the L-20) and the USAF; and 60 older-model Canadair F-86 Mk II Sabre aircraft flying with the USAF.

426 Squadron made 599 round-trip flights between McChord Air Force Base (AFB), near Tacoma, Washington, and Haneda airfield in Tokyo while working with the USAF’s Material Air Transport Service.

RCAF fighter pilot logbooks show that about 20 percent of all combat missions, including some MiG aircraft “kills” by Canadian Sabre pilots in Korea, were flown in Canadian-built Sabres.

The first Canadian airman to be involved in the Korean War was RCAF Wing Commander Harry Malcolm. He and Canadian Army Lieutenant-Colonel Frank White were sent to report first-hand on the status of the war as Canadian participants in the UN Commission on Korea.

In October 1950, the RCN sent Lieutenant-Commander Pat Ryan, a naval aviator. His duty was to investigate “anything naval air” that might require the participation of a squadron of RCN Sea Fury fighters. However, similar to the RCAF, the RCN was otherwise committed – in their case, to an anti-submarine warfare role with NATO in the North Atlantic.

In November, 1950, the first RCAF combatant, Flight Lieutenant Omer Levesque, on a one-year exchange duty with the USAF, flew to Korea with his squadron. Sitting beside him was Flying Officer Joan Fitzgerald, the first RCAF flight nurse to participate in the war. Flight Lieutenant Levesque completed his tour of duty in June 1951 while Flying Officer Fitzgerald returned to Canada in March 1951.

The Canadian Army entered the war in February 1951, and the first Canadian casualties soon followed.

In the early part of the war, 426 Squadron flew some wounded US personnel to Honolulu, Hawaii, and, later, some of the Canadian walking wounded home to Canada. RCAF nurses, who’d been taking training in the US, increased this commitment when the Korean War broke out.

Seven weeks of nursing classes and practical training, including familiarization flights and ditching drills, were held at Gunter AFB, in Alabama; immediately following was a three-month tour carrying out medical air evacuations from the Korean War in the Pacific. All flight nursing graduates (RCAF, USAF and USN) were stationed in Honolulu.

The RCAF flight nurses program in the Pacific ran from November 1950 to March 1955 and involved some 40 nurses who served in pairs. They did not serve in Korea, nor did they fly with the RCAF’s 426 Squadron during their Pacific tours with the USAF.

435 Squadron, stationed at RCAF Station Edmonton and later at Namao, Alberta, transported Canadian wounded from McChord AFB across Canada as required. 435 was equipped with DC-3 Dakotas powered by three supercharged, high-altitude engines. The aircraft carried 16 litter patients, with oxygen. On occasion, 412 Squadron from RCAF Station Rockcliffe, near Ottawa, Ontario, and 426 Squadron also evacuated Canadian wounded from McChord.

Flight nurses who had completed their tour of duty in the US or the Pacific were stationed at various Canadian airfields and at least one qualified flight nurse always accompanied RCAF medical evacuation flights in Canada.

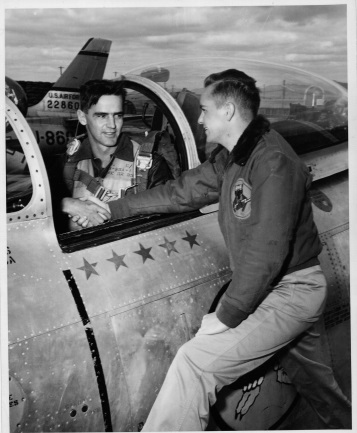

Twenty-one RCAF volunteer fighter pilots (not including Flight Lieutenant Levesque) were sent to Korea for F-86 combat duties and they served from March 1952 until November 1953 in small scheduled groups.

They flew exclusively with the USAF’s 4th Fighter Interceptor Wing at Kimpo, northwest of Seoul, or the 51st, at Suwon, south of Seoul. Both fighter interceptor wings had three fighter squadrons and Canadians served in all six of them. A few had extra duties at the wing level.

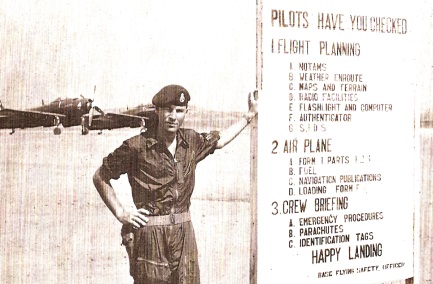

RCAF pilots served for six months or 50 combat missions, whichever came first. Fifty missions normally took three to four months. On arrival at their assigned squadron, pilots were usually given a short on-squadron introductory flying program called “Clobber College”. After that, they went into combat.

A combat mission normally consisted of flying about 322 kilometres over enemy territory to the infamous “MiG Alley”, near the Chinese border, patrolling, contacting and fighting with the communist’s MiG-15s, and returning home.

A round-trip mission usually took about 90 minutes: 30 minutes to MiG Alley on drop tanks (external, often jettisonable auxiliary fuel tanks) and 60 minutes on internal fuel. Double-mission days were frequent and there were some triple-mission days.

MiGs were sighted on only about 10 per cent of all missions to MiG Alley, and even fewer missions involved combat. MiGs had sanctuary across the Yalu River in China, but it was found that an estimated 75 per cent of MiG “kills” were across the Yalu.

There were no fatalities in this group, but many close calls. RCAF pilot Squadron Leader Andy Mackenzie had to eject, and was a PoW for two years. Flight Lieutenant Bob Carew experienced an engine failure over enemy territory and, while his squadron flew top cover, he glided to the coast, ejected over a friendly island and was rescued by the USAF.

Squadron Leader Eric Smith and Squadron Leader Doug Lindsay endured head-on shooting passes with MiGs. While on patrol near the Yalu River, Squadron Leader Smith encountered a MiG with its two 23-millimetre cannons and one 37-millimetre cannon firing. He fired back. Their second pass lasted just a few seconds, then the MiG withdrew.

Flight Lieutenant Bob Lowry and Flying Officer Gene Nixon were returning to base when they spotted an enemy train in a valley. The Sabres strafed the train but a trap had been set at the end of the valley, and several anti-aircraft batteries opened fire from the adjacent hills. The flak was intense but they both escaped.

The RCAF accounted for nearly 900 combat missions with nine MiG “kills”, two “probables”, and 10 “damaged”. RCAF pilots received eight U.S. Distinguished Flying Crosses and 10 U.S. Air Medals. Flight Lieutenant Ernest Glover was the last and only RCAF pilot to be awarded the Commonwealth Distinguished Service Cross since the Second World War.

Just two weeks after the North Koreans invaded South Korea, 426 Transport Squadron was alerted to move to McChord AFB to participate in Operation Hawk, the Canadian military portion of the Korean War airlift. The squadron had 12 “war-strength” North Star aircraft, and would integrate with the USAF’s Military Air Transport Service, cease all domestic flights except those that were essential, and operate into Japan but not into Korea.

The flights over the North Pacific route called for careful planning to deal with the severe and unpredictable weather, and the flights over the mid-Pacific route required precision to deal with the long legs over open water.

Radio navigation aids existed at each end of the Aleutian-Islands-to-Japan leg, but were only good for about 161 kilometres at each end. Land to the west was Russian territory; radio jamming was a way of life. The northern route required two refuelling stops, one at Elmendorf AFB (near Anchorage, Alaska) and one at Shemya Island in the Aleutians. The southern route went via Travis AFB in California, Honolulu, and at least two other Pacific islands, usually Midway and Guam. The southern route was the longer route by 10 hours.

Shemya Airfield, located 1,770 kilometres from the west coast of Alaska at the remote end of the Aleutian Islands, was a crucial stop-over point for all flights to and from Japan. Weather along the Aleutians is as bad as anywhere in the world.

To combat this, the USAF provided a ground controlled approach system with top-quality operators to ensure safe arrivals even when the weather was below limits. In spite of this, in December 1953, an RCAF North Star, after making a safe but difficult landing in a blinding snow storm and in a heavy cross-wind, was blown off the slippery runway. Although there were no injuries or cargo lost, the aircraft was completely destroyed.

The three most senior RCAF officers in Korea were Group Captain Ed Hale, who flew F-86 combat missions with the USAF at Suwon in 1952, and was the commander of the RCAF’s No. 1 (Fighter) Wing, North Luffenham; Group Captain Robert “Buck” McNair, the air attaché at the Canadian Embassy in Japan; and Group Captain Ken Patrick, commander of the Air Force Reserve in Montréal and founder and CEO of Canadian Aviation Electronics in Montréal.

Group Captain Patrick had served as a communications expert during the Second World War and, because of his in-depth knowledge, was invited by the Canadian and U.S. governments to carry out top-secret interrogation flights over North Korea. To achieve this, he spent five weeks (November to December 1951) flying with the USAF’s 343rd Bomber Squadron out of Yokota, Japan.

He flew on six B-29 bombing missions and acted as the radar officer to analyse enemy radar and the available counter-measures equipment. On each mission, one or two of the six B-29s in the bombing formations was either shot down or badly damaged.

During the Korea War, 516 Canadian military personnel and seven Canadian Pacific Airlines personnel died. Thirty-three Canadian prisoners of war were held, most of whom were Army personnel, but also included RCAF Squadron Leader Andy MacKenzie.

Thirty-three Canadians have no known graves, including 16 Army personnel who were reported missing in action. The last official Canadian casualty of the Korean War, Major Edward Gower, was on his return flight from Korea to Calgary in December 1956 when his TCA North Star hit Mount Slesse (near Hope, British Columbia). The wreckage was found in May 1957 and the remains of all 62 crew and passengers rest on the mountain to this day.

In all, Canadian airmen flew more than 2,200 combat missions and more than 1,500 round-trip airlift flights during the Korean War. RCAF nurses were involved in about 250 medical evacuation flights in the Pacific and many more throughout Canada.

Canadians received 57 Commonwealth and US awards, medals, and commendations. This number would have been higher except for a strange rule imposed by the Canadian military directing that only one US medal could be awarded to each Canadian serving member.

Canadian military personnel and civilians served with courage and distinction during the Korean War. Thankfully, today, the Korean War is no longer “the forgotten war”.

An Armistice was signed on July 27, 1953.