Track and field for Masters Athletes 5: Planning your training phases

News Article / July 17, 2020

Click on the photo under “Image Gallery” to see more photos.

This is the fifth in a series of articles covering all aspects of Masters Athletes’ training and nutrition for track and field events. Here, we take a closer look at the phases of training, and how they are laid out over a specific period.

By Major Serge Faucher

In my last article, we discussed how proper planning will greatly impact overall success in masters track and field athletes. Every athlete is different, has unique attributes, and may differ in age. This means that she or he cannot expect a ready-made program to meet her or his needs. We looked at the basic elements for planning, from proper periodization to training cycles, maintaining a training log, and balancing training with recovery periods.

In this article, we take a closer look at the phases of training, and how they are laid out over a specific period.

Normally, an athlete would build a sound base of aerobic training for a minimum of two to three months. This prepares your body for the hard work that awaits you in Phase II and III of your overall schedule. A solid aerobic base also enables you to race two or three times on the same day during major competitions such as the World Masters Athletics Championships. This base training, or Phase I, will normally begin after the summer track season is over, assuming you will peak only once that year. It is also the phase where you would introduce hill training for building strength (more on this type of training and its benefits in a future article).

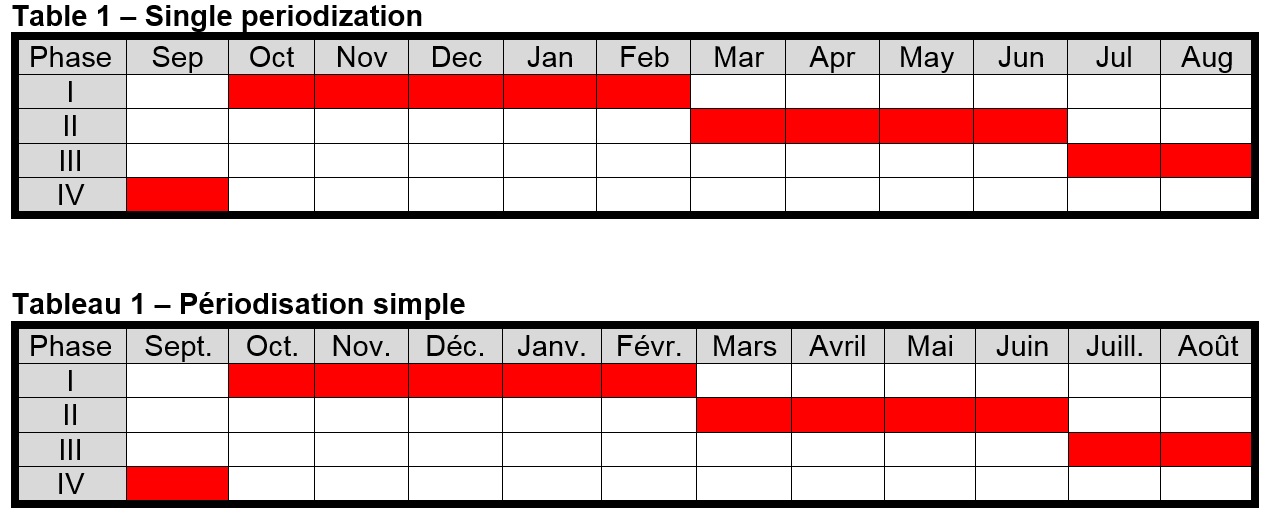

In this example of a single periodization plan (see table 1), you would start your “base training” in October and build up until the end of February. Base training is for general development of strength, mobility, endurance and basic technique. This is a very important phase in anyone’s training program. The bigger the base, the higher the peak you will achieve down the road! The emphasis is more on volume than intensity at this stage. Since the intensity is still quite low, your general level of stress will be low as well, and easily managed. This is the time to have fun, experiment, and freely make use of cross-training exercises in your weekly schedule to help with overall volume and conditioning. I usually take only one day off each week, often working out twice a day during that time.

In March, you would transition into Phase II, where you would introduce more race-specific training sessions with plenty of speed. You would concentrate on the development of specific fitness and advanced technical skills at this point. That means spending more time running at the track instead of using the elliptical or the bike. This is the time I get serious about training, incorporating various drills and speed work while still maintaining a fairly high training volume overall.

This may be the toughest phase yet, as I often do seven to nine workouts each week (twice a day on Tuesdays and Thursdays), taking only two days off. These workouts include running, cross training, weight training, the occasional hill training, and plyometric exercises. You will certainly feel tired and sore most of the time, but that’s okay because you are not racing at this point. Just keep a close eye on your level of fatigue or any possible injuries that could creep up. Never hesitate to take an additional day off if you feel things are not quite right.

In July, you would transition into the racing phase and hope to peak for a specific race in August. By now, you are quite fit, but you still lack those quality workouts and additional rest that will bring you to peak form. During Phase III, the emphasis is on quality rather than quantity, so try to take three days off each week, because rest is crucial at this point. The workouts are shorter but very intense, and often done at race pace or faster. Rest between repeats is at its highest, sometimes up to 20 minutes when running two times 500m repeats at 90 to 95 percent intensity, for example.

The taper may also be included in this phase (or become a phase on its own), and will vary depending on the event: seven days for a sprinter (100m to 400m), and 10 to 14 days for a middle distance (800m to 3000m) athlete. Marathoners are known to taper for three weeks. I will discuss the taper in more detail in the near future.

It is important to take downtime before commencing a new season. As most outdoor track and field seasons end in August, part of August and September will be used to rest the body, recharge the mind, and plan the next season. One of the greatest swimmers in the world, Ian Thorpe, would take an entire year off from serious training after the Olympics.

Getting older also means that you don’t get as many days each year, compared to younger athletes, where you can push yourself in the “red zone”. Each one of those hard training sessions requires significant mental and physical rest afterwards. While your body may feel alright after a few hard sessions, your central nervous system (CNS) may take as much as five times longer than your body to recover. Feel free to take a whole month off and enjoy life during that time!

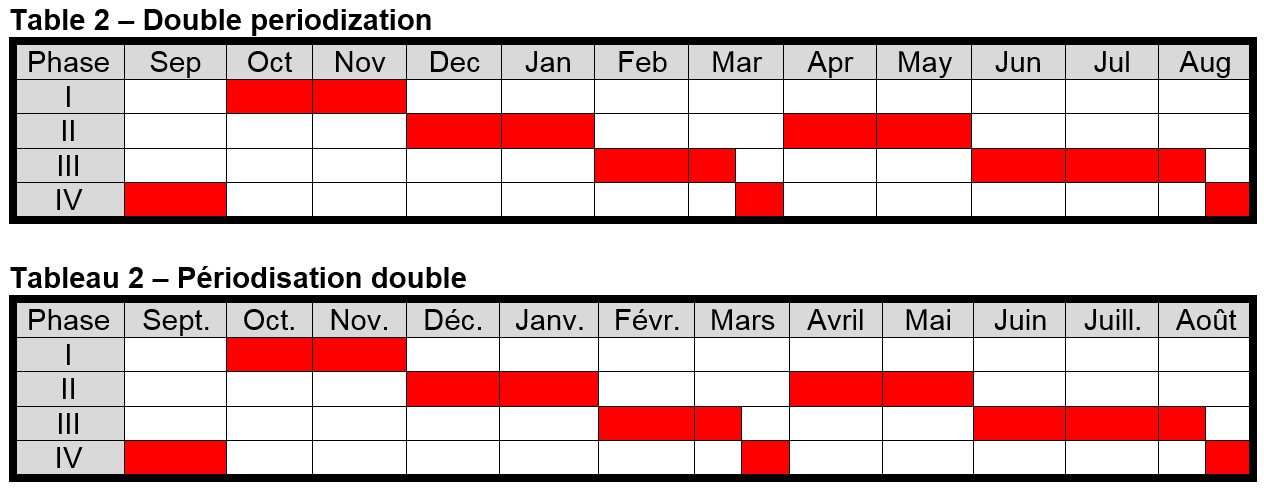

Table 2 illustrates an alternate schedule for 2020 and an example of double periodization based on one’s need to peak in mid-March and again in early August. The rest of August and most likely the entire month of September 2020 would be your downtime for mental and physical recovery.

You may notice that following Phase III in March, you do not revert back to Phase I (base training). Instead, you take 7 to 14 days off before proceeding back to Phase II and carry on with the speed work you’ve already gained in the months before. Going back to Phase I at this point would be detrimental on the speed you worked so hard to acquire as speed is lost very quickly and should not be neglected. If you stop doing what I refer as “pure speed” for even one week you immediately start to lose it, unlike the aerobic energy system which declines at a much slower rate over several weeks or months. Since the outdoor racing season begins in June, it would not be wise for any athlete to lose those hard-earned gains!

In the next article, I had planned to go straight into how to build the desired micro-cycles (your actual weekly schedule), which will incorporate the appropriate training and recovery sessions. I must first explain how energy systems function as a stepping stone first. This is where the rather complex training principles I’ve covered in the last two articles will start to become clear.