25 years ago: Combat and Cold Lake

News Article / February 25, 2016

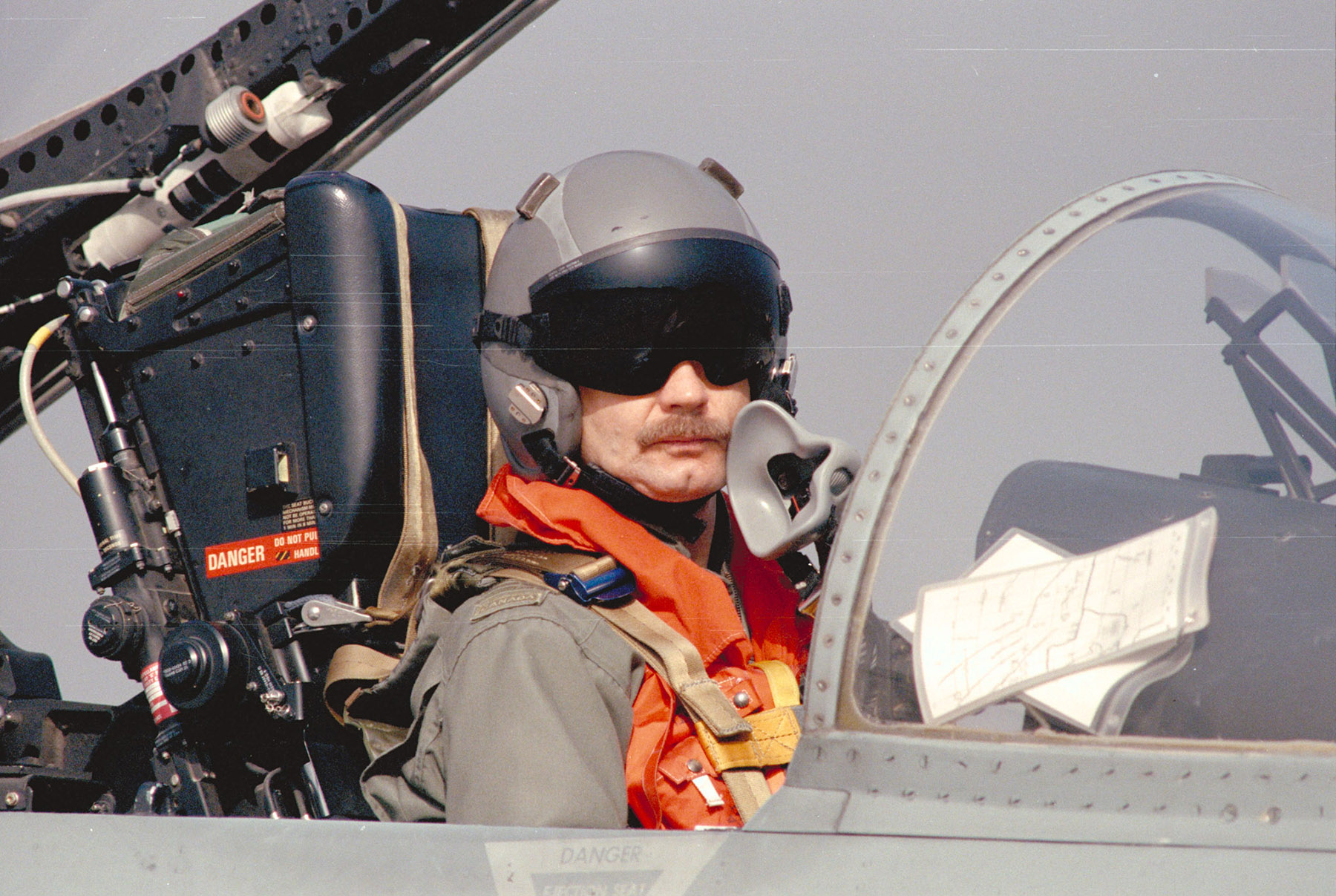

A few weeks after Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait on August 2, 1990, the Prime Minister announced that CF-188 Hornet fighters would be dispatched Doha, Qatar, to fly combat air patrols (CAP) over coalition naval vessels in the Gulf. The first rotation was carried out by an enlarged version 409 Tactical Fighter Squadron (augmented by elements of 421 and 439 Squadrons). Late in the year, 409 Squadron was replaced by a squadron formed from elements of 439 Tactical Fighter “Tiger” Squadron and 416 Tactical Fighter “Lynx” Squadron. “The name of Desert Cats came to us,” said then-Lieutenant-Colonel Don Matthews, the commander of the Desert Cats, “and was to stick as the level of activity increased daily.” *

At that time, 439 Squadron was based in Canadian Forces Base Baden-Soellingen in Germany and 416 Squadron was located at Canadian Forces Base/4 Wing Cold Lake, Alberta. 409 Squadron, the first squadron to enter the Kuwait theatre of operations, was disbanded in 1991 and re-established two years later as 409 Combat Support Squadron. This incarnation of the squadron was again stood down in 1994, but re-born at Cold Lake in 2006 as 409 Tactical Fighter Squadron from the amalgamation of 416 and 441 Squadrons. 439 Squadron was disbanded in 1993 and reactivated shortly afterward at 3 Wing Bagotville, Quebec, as 439 Combat Support Squadron, flying CH-146 Griffons.

Here’s an account of the Gulf War from the point of view of 416 Squadron and its home base, Cold Lake.

By Jeff Gaye

Brigadier-General (retired) Ed McGillivray took command of Canadian Forces Base/4 Wing Cold Lake, Alberta, in July 1990. He remembers that summer as a hot one, but not because of the weather.

After Canadian troops had been sent to Oka, Quebec, site of a Mohawk First Nation protest over municipal annexation of traditional lands, Brigadier-General McGillivray was concerned the deteriorating relations between indigenous organizations and the federal government would affect the relationship between the base and Cold Lake First Nations (CLFN). When someone set fire to the trestle bridge over the Beaver River, effectively cutting the rail line the base relied on for fuel deliveries, many wondered if it was the beginning of a confrontation between CLFN and Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Cold Lake.

Meanwhile, reductions in the defence budget were starting affect the way the base functioned.

“It was all one thing on top of another,” Brigadier-General McGillivray, who held the rank of colonel at that time, says, “and I remember thinking, ‘what did I do to deserve this type of scenario?’ ”

Then, on August 2, 1990, Iraqi forces invaded Kuwait.

The aggression drew immediate reaction from the international community. If Iraq held Kuwait, then Iraq’s leader, Saddam Hussein, would control a huge portion of the region’s oil economy, with strategic implications for the rest of the world. The United States, under President George H.W. Bush, demanded that Iraq withdraw. Canada joined the chorus of nations condemning the invasion of Kuwait, and played a leadership role in getting the United Nations to support action to liberate Kuwait from Iraqi occupation.

War appeared certain. “As we went through all the UN motions and whatnot, I knew that eventually Canada would be participating,” Brigadier-General McGillivray says.

Around the same time that Brigadier-General McGillivray took over as base commander, then-Lieutenant-Colonel Ron Guidinger assumed command of 416 Tactical Fighter “Lynx” Squadron, located at Cold Lake, from Lieutenant-Colonel Laurie Hawn.

Lieutenant-Colonel Guidinger was impressed by the squadron’s state of readiness. After the invasion of Kuwait, he knew that 416 Squadron would be the likely choice if Canada elected to send its CF-188 fighters to the Persian Gulf. He ramped up deployment training to prepare in case the call came.

“We deployed a lot during that three-month period to get somewhere, set up, do operations and deal with the tactics we would expect to use,” he says. “And also to work with the Americans, because they were leading this thing, and to fine-tune those command and control procedures at the tactical level.”

Meanwhile “the maintenance side of the squadron was really focused on making sure the jets were in top shape,” he says. “That was easy to do because the base was very supportive, all the squadrons were helping in that regard.

“The team – the people team – had to come from much more than just 416 Squadron,” he says. They drew on 441 and 410 Squadrons, the Aerospace Engineering Test Establishment, and the Base Air Maintenance and Engineering Organization, now 1 Air Maintenance Squadron.

In August, Canada had sent three ships with embarked CH-124 Sea King helicopters to patrol the Persian Gulf under Operation Friction. In September, the prime minister announced that a Canadian fighter squadron would be sent to fly combat air patrols (CAP) to protect Allied naval forces in the region; the air mission was dubbed Operation Scimitar and would operate out of Doha, Qatar. By early November, Scimitar ended and all Canadian air operations were drawn under the umbrella of Operation Friction.

In December, 409 Squadron was replaced by a squadron made up of 416 “Lynx” Squadron, from Cold Lake, and 439 “Tiger” Squadron, based at Baden-Soellingen, Germany. The combined squadron, commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel Don Matthews of 439 Squadron, quickly became known as the “Desert Cats”.

Before the handover of responsibilities, nine jets, aircrew, groundcrew and equipment from 416 Squadron flew to Baden-Soellingen where they spent three weeks upgrading their electronic warfare equipment and training with the Canadians there.

“Thank goodness we still had a presence in Germany at the time,” Brigadier-General McGillivray recalls. “If we didn’t have that, it would have been far more difficult. We staged everything through Baden-Soellingen, and the staff over there did exceptional work organizing it all.”

It was Canada’s first foray into war since 1953, and Canadian Forces Base Cold Lake’s first ever. Both Lieutenant-Colonel Guidinger and Brigadier-General McGillivray understood the importance of supporting the home front back at Cold Lake.

“That’s where we spent a lot of time,” Lieutenant-Colonel Guidinger says. “What are we going to do to make sure everyone at home is well taken care of as we move into another Cold Lake winter, with Mother or Father deployed?”

“And then dealing with, hey, we’re going to war. Somebody shooting at you, people might get hurt – dealing with that fear. That took all the helping professionals: the medical, the padres, social work, and forming a rear party. Identifying who would go and who wouldn’t go on the deployment,” he says. Everybody was charged up and ready go, and it was often harder for Lieutenant-Colonel Guidinger to tell someone they would be staying home.

“I appointed my best officer from the squadron to lead the rear party, Major Dave Burt.”

Brigadier-General McGillivray says the base’s ongoing NORAD role and the Operation Friction rear party were its two biggest missions. “I thought we excelled in that regard,” he says. “There was continuous contact to update dependants, roving teams to support families with everything from transport to grocery shopping and everything else, to help families cope. It was a very fearful time. Nobody knew what was going to happen with all the groundcrew and aircrew over there in Qatar. Obviously, it was wartime, obviously people get hurt. So obviously everyone was very fearful.

“And then one of the things I remember that stands out about the rear party was the great Christmas parties we had for the dependants that year,” he continues. “It was just great, and it took our minds off of a lot of the troubles and the fear over what was happening in Kuwait.”

Warrant Officer (retired) Bob McKinnon was in charge of a 40-person servicing team at 416 Squadron. He remembers arriving in Doha at 2:00 a.m. on December 12, and starting work seven hours later. They were already launching and recovering aircraft, though the fighting hadn’t started.

Much of their time was spent filling sandbags. “We started filling sandbags that first day,” Warrant Officer McKinnon says. “We did a lot of sandbags, I remember that. Every day after we got off shift, we’d go eat and then spend a couple hours doing sandbags and building up our shelter for air attacks, stuff like that. We did that right through to when the war started.”

The shelter was a concrete culvert structure, built up with the sandbags. “We weren’t too enthused when we saw what we had for shelters,” he says.

Pre-war camp life settled into a routine of sorts. Personnel had their own Christmas party with a small exchange of gifts. Warrant Officer McKinnon remembers a football game on the Doha base’s soccer field on New Year’s Day. “The Qatari soldiers looking at us thought we were all strange,” he says. “They were a little upset because some of our girls had short-sleeved shirts on and there were complaints about it, so we had to start watching that kind of stuff.”

The mood at that time was similar to any other deployment, he says. “It was a little bit of a lark. I don’t think even then any of us thought we were really going to go to war. There weren’t going to be bullets flying or anything like that. We prepared, like any military people. We were seriously preparing, but I don’t think deep down any of us really thought it was going to happen.”

But on January 16, when the deadline for Iraq’s withdrawal from Kuwait passed, Coalition forces, including the Canadians, began a massive offensive air operation as part of the U.S.-led Operation Desert Storm. The mood around the Canadian camp changed noticeably. Warrant Officer McKinnon remembers making his way to the mess tent when he heard an announcement summoning all battle staff to the command bunker. “I remember thinking: ‘oh dear, this is not good’.”

Right up to that point he felt sure it wasn’t going to happen. But after supper he gathered his crew, reminded them to work in pairs and look after each other because he had a sense that this was the start of the war. “Suddenly, we got an air attack warning. It was sort of controlled, I guess, but everybody just scrambled.”

Over the course of the war, the camp faced 26 missile attacks. The personnel worked well together and kept each other safe.

Meanwhile, the war was being brought home every day on television. CNN’s Gulf War coverage is credited with making that network an important player in television news, but very few Cold Lake homes had satellite TV. The A&W restaurant was one of a few places where people gathered during the day to watch the remarkable footage of the war in progress.

Lieutenant-Colonel Guidinger notes that having the war televised added to the stress for some families, which in turn played a small part in Doha. For the most part, though, he says the troops held together very well.

“Let’s do it the best we can”

“I had to send maybe half a dozen people home,” he says. “Some very normal situations on the family front, where the member has to be there. Some disciplinary things, and some people who had the hell scared out of them having to put on an NBCW [nuclear, biological and chemical warfare] suit and run into a shelter during a Scud missile alert.”

The stress varied from time to time, he says, and it was occasionally an issue.

Brigadier-General McGillivray says dealing with the media who came to Cold Lake became a time-consuming task. “It seemed like every television and radio station plus newspaper reporters within five or six hundred miles descended on Cold Lake looking for the perfect sound bite and as much information as they could get.”

It reached the point where he held regular press conferences in the Officers’ Mess parking lot, “which, as you can imagine, took time away from more mundane issues like fighting a war.”

Warrant Officer McKinnon says there are a couple matters of Canadian military doctrine that benefited from having the Gulf War as their proving ground. One is the principle of Universality of Service, which dictates that all Canadian Armed Forces members, regardless of occupation, are part of the fighting force.

“We found when we went to go, we had people who were single parents, we had people that had problems with children or family, and even some health problems, and so by the time we were gearing up to go we realized we didn’t have as many people in the squadron who were capable of going as we thought,” he says. “I think that’s when they finally said ‘oh yeah, this Universality of Service never really affected the air force before’. Suddenly it did. We had to bring in people from 410, 441 [Squadrons] 1 [Air Movements Squadron] just to bring ourselves back up to our strength.”

This was also Canada’s first war since integrating women into all occupations, including combat roles. Warrant Officer McKinnon recalls two women who were in his servicing crew. “They worked hard through the whole war without a complaint,” McKinnon says. “They were in combat just like anybody else. And they held their own – in fact, better than their own, as far as I’m concerned.”

Hussein’s invading force was routed by the huge coalition effort that culminated in a one hundred-hour ground campaign. By February 28, Iraq had withdrawn to its pre-August borders and a ceasefire was declared. Lieutenant-Colonel Guidinger believes that, despite almost 40 years as a peacetime air force, it was the Canadian pilots’ level of training and experience that made their success possible. This, he says, gave the Air Force more choice to draw from, and enabled regular rotations without unduly compromising training at the home bases. “Speaking of home bases, we also had Baden-Soellingen, which provided not just many of the fighter pilots and maintenance crews but much-needed, close-to-theatre logistics and maintenance support.”

“I guess at the end of the day, the Gulf War was successful,” Brigadier-General McGillivray says. “Iraq was kicked out of Kuwait, I like to think we had a small part to play in that. But the big thing that was really gratifying to me was that we didn’t lose any Canadian lives in the war, not even in a car accident or anything.

“And I will always remember the huge welcoming home party with hundreds of people who attended from Cold Lake, and senior military and government officials, including the Minister of National Defence. I spent a lot of time with [the Minister] and he spent a lot of time talking to people who just got back from the war, because it was a very, very emotional experience. And when they all came back, believe me, there was nobody happier in the world than myself.”

“I brought all the belly buttons home”

Lieutenant-Colonel Guidinger feels the same way. “The highlight of my 28-year career was when I looked over my shoulder after I led my nine-ship through the arrival in Cold Lake. I looked over my shoulder and taxied out the runway on arriving and I saw the last of the nine jets land. So that marked a moment when I knew that I brought all the belly buttons home that I took over there. And we’d gone and done what we needed to do. And we’d done it well.”

Warrant Officer McKinnon, too, was happy to be home and pleased that no lives were lost. But for him, the end of the war was the beginning of a new phase, advocating on behalf of Gulf War veterans who returned with psychological injuries including Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). He has participated in inquiries and commissions to help the veterans have their injuries recognized.

He takes some satisfaction in knowing that the work done on behalf of Gulf War veterans has led the way for the Canadian Armed Forces to understand PTSD and to learn more about it. His worry, as the Gulf War is overshadowed by later campaigns including Afghanistan, is that the vets of 1991 will be forgotten.

All in all, though, he considers the Gulf War to have been an important experience for Canada’s military, with lessons learned that are being applied to this day. “I’m glad I went,” he says. “And I wouldn’t want to do it again.”

* From Desert Cats: The Canadian Fighter Squadron in the Gulf War by Captain David N. Deere, 1991.

* This article first appeared in the January 19, 2016, edition of 4 Wing Cold Lake, Alberta, newspaper The Courier, and is reprinted here with permission.