Flags and Colours

The flag, a piece of coloured cloth, is among the oldest of symbols, and at the same time one of the most up-to-date. Dipped in blood and ladshed to a pole overhead, it cowed the vanquished in remote times of human conflict. Planted in the lunar dust, it proclaimed the simple courage and faith of men and one more instance of the mastery of his environment. Spanking on a stiff breeze, like a sail before the wind, it is a thing of aesthetic beauty. Draped against a wall, it can mean hope and succour to the suffering, or dread to the fearful.

It is hard to visualize a world without flags because they serve man so effectively. They symbolize his feelings, achievements and aspirations. They identify. They send messages or, as the sailor says, they make signals. They are so practical — a red flag to warn the motorist of road repairs, or to keep clear because ammunition or fuel is being embarked; or the yellow flag of quarantine indicating the presence of infectious disease; or the "Blue Peter" at the fore truck saying: "This ship is about to sail."

Flags convey abstract yet strongly felt ideas, often with emotional impact perhaps the symbol of some political philosophy, or the sorrow of the meaning of the flag at half-mast, or the joy of seeing the queen's personal Canadian flag floating over Rideau Hall when Her Majesty is in residence there.

The most common use of a flag is to show nationality, to identify a people. It is said that the oldest national flag, unchanged in design, is the Dannebrog, the red flag with the white cross which has flown over Denmark since 1219.Footnote 1 In comparison, the Royal Union Flag as it is known in Canada today and which was approved by Parliament in 1964 "as a symbol of Canada's membership in the Commonwealth of Nations and of her allegiance to the Crown," dates in its earliest form from 1606.Footnote 2 The national flag of Canada, the Maple Leaf Flag, was adopted by Parliament and proclaimed by Her Majesty the Queen on 15 February 1965.

Because the national flag symbolizes sovereignty, loyalty to the Crown, the laws and institutions of the nation, the authority of Parliament and the proud heritage of the people, it demands respect, and that respect together with affection, is expressed in custom and tradition, for example colours and sunset.

At Canadian Forces bases and establishments colours in this context means the hoisting of the national flag normally at 0800 hours. It is lowered at sunset. Proper marks of respect are paid by all persons in the vicinity. In most cases the hoisting and lowering is carried out by a designated non-commissioned officer, sometimes by a commissionaire. Regrettably, an elaborate ceremony is much more likely to be observed with respect to Canada's national flag at a headquarters like Colorado Springs than at Canadian operational bases, even to the parading of a guard and band. Several reasons are given for this: shortage of personnel; the fact that most people live off the base; and, perhaps, the tendency in modern times to down-grade patriotism.

In training establishments, the story is quite different. For example, at the Royal Military College, Kingston, the national flag is hoisted and lowered with impressive ceremony daily by a detachment of five cadets called "the fire picquet." Off to the side, the proceedings are observed by the cadet duty officer and the duty staff officer a member of the senior staff. At sunset, a piper contributes to the solemnity of the occasion.Footnote 3 A similar daily routine is carried out at le Collège Militaire Royal de Saint-Jean, Quebec, and at Royal Roads, Esquimalt, British Columbia.

At Canadian Forces Base Chilliwack, British Columbia, a training base, colours and sunset are accompanied by the appropriate bugle calls and the playing of the national anthem, all controlled electronically from the guard house.Footnote 4

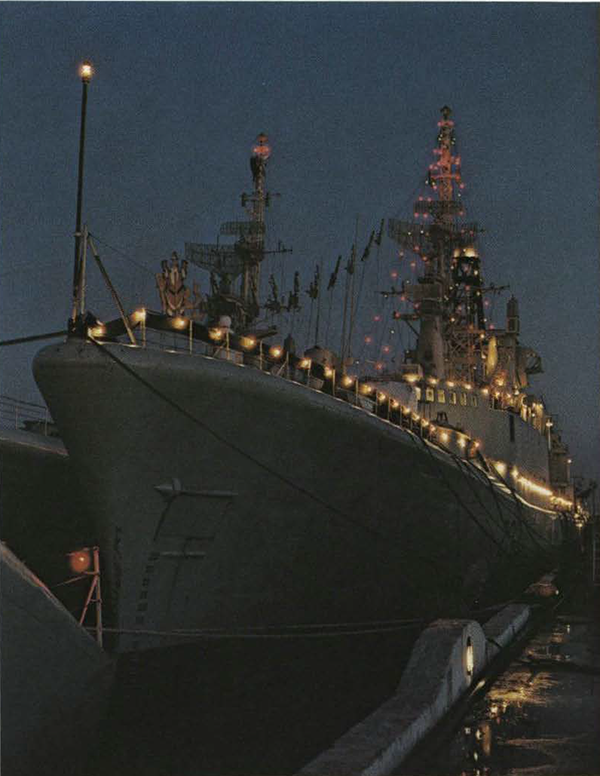

In HMC ships, the national flag is known as the ship's ensign. This conforms with naval practice in French and United States warships where the country's flag is worn as the naval ensign, whereas in ships of the United Kingdom and the Soviet Union, ship's of war wear a distinctive naval ensign quite different from the national flag.

When HMC ships are in Canadian ports, they generally conform to colours and sunset as performed on land bases, that is, 0800 and sunset. When the alert is sounded on the bo's'n's call, all hands on the upper deck face aft and salute. The ship's ensign in HMC ships in commission is worn at all times, day and night, when under way. The wearing of the Canadian Forces ensign in Canadian ships of war is forbidden.

It is an impressive sight when there are many ships of the fleet in their home port, either at colours or sunset. All ships act in unison, governed by the "preparative" flag hoisted on the port signal tower ashore or in the senior officer's ship afloat. The signalman reminds the officer of the day that it is "five minutes to sunset, sir." When the preparative is sharply hauled down, the officer of the day repeats the time-honoured words: "Make it so!" Should the ship's boat be in the vicinity the coxswain orders his engine cut, comes to attention in the stern sheets, faces the stern of his ship nearby, and salutes.

Because of the nature of life afloat, flags are used much more by sailors than by soldiers and airmen, and here the pennant plays an important part in the daily routine at sea. Like the ensign at the stern and the jack at the jack staff forward, the ship's pennant at the peak of the mast is part of a ship's "suit of colours."

The ship's pennant, sometimes called the commissioning pennant or masthead pennant, is the mark of a ship in commission and the symbol of the authority of the captain to command the ship. This symbolism is of great antiquity. Mr. Henry Teonge, a chaplain in the Royal Navy wrote in his journal at Malta on 22 February 1676:

This day we saw a great deal of solemnity at the launching of a new brigantine of twenty-three oars, built on the shore very near the water. They hoisted three flags in her .... Then they came out and hoisted a pendant, to signify she was a man-of-war. ... Footnote 5

When HMS America, a frigate of forty-four guns, was commissioned at Devonport in 1844 for service in the Pacific to watch over the infant settlement on Vancouver Island, a naval officer recorded: "The pennant hoisted, the first lieutenant and master remained to fit the ship for sea, ... and, with the aid of flaming posters, to attract a ship's company."Footnote 6

In HMC ships, the pennant is six feet long and only three inches wide at the hoist, tapering to a point at the fly. Though a new masthead pennant has been designed with three equal vertical panels, white-red-white, HMC ships continue to fly the ancient white streamer with the red St. George's Cross at the hoist. It is broken at the mainmast head at the time of commissioning and is flown continuously throughout the ship's commission.Footnote 7

Closely associated with the ship's commissioning pennant is the paying-off pennant. It is traditionally flown when leaving a fleet or squadron and when entering home port for the last time prior to paying-off (not "de-commissioning"). This pennant and the ritual associated with it have long been dear to the sailor's heart, for they meant going home and at long last receiving his pay.

While a destroyer today may spend her whole life of say twenty-five years in a single commission, in earlier times a ship of war was usually paid off after say three years to be refitted or laid-up "in ordinary" in the dockyard of her home port. HMS Victory of Trafalgar fame was launched in 1765 and is still in commission at Portsmouth today. In her life time, she has served many commissions.

Also in earlier times, members of the ship's company had most of their pay withheld until the end of the commission. So that in addition to the ship herself being paid-off, the seamen were literally paid-off. The passage home was therefore a generally happy one. One of the ways the sailors celebrated was in the making of the paying-off pennant and hoisting it at the mainmast head. Custom ordained that in a normal commission, the length of the pennant equalled the length of the ship. But if, as often occurred, a commission had been extended, the pennant was increased in length proportionately.Footnote 8 Many a ship has come home with her paying-off pennant streaming well astern of the taffrail, the tail-end kept afloat by a skin bladder!

One of the most aesthetically attractive bits of bunting still used at sea today is the church pennant. It is divided into a red St. George's Cross on a white field at the hoist, and three horizontal stripes, red, white and blue, in the fly. Hoisted at the mainmast peak or at a yardarm halyard, it means that the ship's company is attending divine service or is at prayers. (This used to be a bit confusing to the landsman for, depending on where in the rigging the church pennant was hoisted, it could mean the recall of all boats or "I am working my anchors").

There is an interesting legend attached to the church pennant. It dates from the seventeenth century Dutch Wars, the sea battles of which usually took place in the North Sea and the English Channel. Before the engagement commenced, it was customary for divine service to be conducted in the ships of both the Royal Navy and the Dutch fleet. So that such devotions would not be interrupted in that more chivalrous age, the ships of both fleets hoisted the church pennant, a combination of the British St. George's Cross and the Dutch tricolour. When the last pennant fluttered down all hands went to action stations!Footnote 9

Divine service at sea illustrates how customs change. The church pennant may be used as an alter cloth or to drape a podium. During the Second World War the white ensign was often used for this purpose, covering a ready-use ammunition locker or some other convenient upper deck facility. But just as often, flag "negative" was used, simply because it was white and had five black-crosses on it. One sailor of the Second World War describing life in a destroyer on Atlantic patrol wrote: "Church is held on the Seamen's Mess Deck, ... The black and white negative flag is draped over the stove .... the Ship's Bible is placed on the flag-draped stove."Footnote 10

However, by the 1950's, the old code of naval flag signals had been superseded for purposes of standardizing communications in combined fleets and the old familiar flag negative with the crosses had disappeared.

Before the advent of the Maple Leaf national flag in 1965, HMC ships flew as a jack the Canadian blue ensign. Today, the jack is a white flag with the Maple Leaf Flag forming the upper canton at the hoist, and a device in blue consisting of an anchor and eagle surmounted by a naval crown, in the fly. Normally the jack is flown only in harbour and always at the jackstaff in the bows of the ship. In 1975, authorization was given for parading the naval Jack of the Canadian Forces on shore by units of maritime command.Footnote 11

Jacks were first flown at the masthead but in a short time, judging by the numerous marine paintings of the period, it was shifted to the sprit topmast a short stump mast fixed to the bowsprit at the bow. The jack has remained at the bow ever since. As long as ships were square-rigged, this was a handy arrangement for this important means of identifying a king's ship. But when fore-and-aft rig came into vogue, with foresails and jibs, the jack often fouled the rigging. As a result, it became the custom for the jack to be flown only in harbour. This is still the case today.Footnote 12

The origin of the term jack is open to considerable conjecture. In British tradition, as in the Union Jack, the word is associated with the flag that gave visible evidence of the union of the crowns of England and Scotland. The sovereign at that time was King James VI of Scotland who became James I of England, and who, in signing state documents, sometimes used the French form Jacques. The story goes that this is the source of the term jack.

However, there is much evidence that jack in the sense of identification, long pre-dates the early seventeenth century. In feudal times the mounted knights and soldiers on foot in the field wore an over-garment extending from the neck to the thighs called a surcoat or jacque (whence our word jacket). On this tunic was sewn a cross or other device to identify the wearer's allegiance to a liege lord or king in the same way as nationality would be shown today. These surcoats or jacks came to be known as the jacks of the various nations and were worn also by the sailors in the ships used to transport the soldiers. It was only one short step in the progression to see a sailor's surcoat or jack lashed to a pole and suspended out over the bow as a means of a ship showing her colours.Footnote 13

From the time of the establishment of the Royal Canadian Navy in 1910 until the arrival of the Maple Leaf national flag in 1965, HMC ships wore the white ensign, and naval shore parties on the march carried the white ensign. 1t was a white flag with a red St. George's Cross overall, with the Union Flag in the upper canton at the hoist. It was identical to that worn by ships of the Royal Navy and other navies of the Commonwealth. This storied flag still exists in the Canadian Forces in the form of the queen's colour of the Royal Canadian Navy which is kept in a special display cabinet in the wardroom of Canadian Forces Base, Halifax. Another, identical in appearance, is held at Canadian Forces Base, Esquimalt.

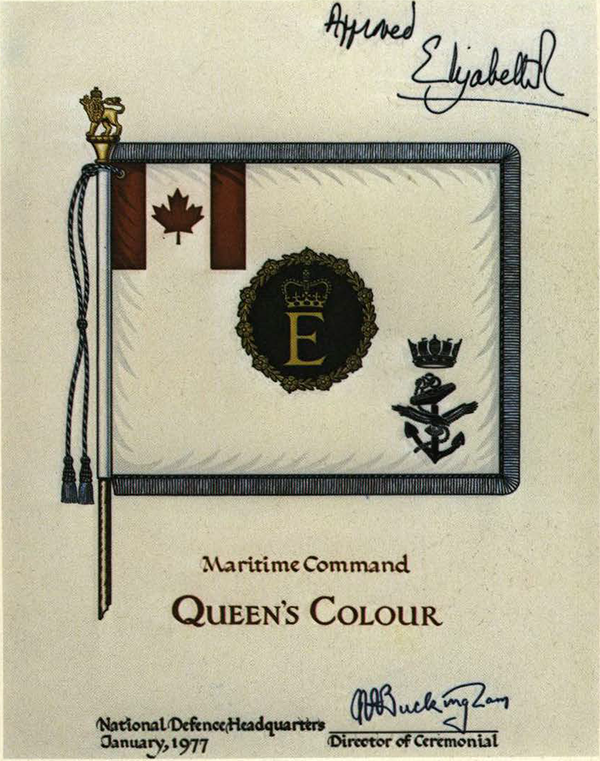

The queen's colour of the naval service has never officially been laid up or retired, yet it cannot be recognized as the queen's colour of maritime command for it does not contain the Maple Leaf national flag. However, at time of writing, a new queen's colour in the form of a white ensign, and containing the Maple Leaf Flag, is being designed for the naval forces.

The sovereign's or first colour, usually called the queen's colour, of the navy, is of recent origin compared to that of the army. First designated "the king's colour" in regulations dated 1747 in the reign of George II, Footnote 14 the sovereign's colour as approved for British regiments pre-dates those of the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force by nearly two centuries.

The king's colour of the Royal Navy was approved for the first time by George V in 1924,Footnote 15 and for the Royal Canadian Navy in 1925.Footnote 16

Some idea of the financial stringencies under which the armed forces of the twenties struggled to stay alive may be gleaned from this first king's colour of the RCN.

Approved by the king in 1925, Commodore Walter Hose, director of the naval service, as much as he wanted the new colour for the navy, could not scrape up the necessary sixty pounds from his budget until 1927. And then, too, there were only two destroyers in commission, HMC ships Patrician and Patriot, one on each coast. A ship's company was essential for the presentation ceremony, for there were not enough seaman ratings ashore, and a ship in harbour just never seemed to coincide with a visit by the Governor-General. So George V's colour never was presented to the Royal Canadian Navy. Today, the one in Halifax is laid up in St. Mark's Church, the one at Esquimalt in the Church of St. Andrew, HMCS Naden, now Canadian Forces Base Esquimalt.

The presentation of the king's colour to the RCN had to await the first visit of the reigning sovereign to Canada. In a memorable ceremony just before the outbreak of war in 1939, George VI presented his colour to the navy at Beacon Hill Park, Victoria. Today, this colour is laid up in St. Paul's Naval and Garrison Church, Esquimalt. Carried out on 24 May 1960, the site chosen for the laying-up seems most fitting, for St. Paul's has been closely associated with all the ships and sailors who have come and gone at Esquimalt for over a hundred years.

George VI's colour at Halifax, considered to have been presented at the same time as that of the Pacific Command was laid up on Trafalgar Day, 21 October 1959 in the Church of St. Nicholas, HMCS Stadacona, now Canadian Forces Base Halifax.Footnote 17

The present queen's colour of the Royal Canadian Navy was presented by Her Majesty the Queen at Halifax on 1 August 1959, and the one at Esquimalt was deemed to have been presented at the same time. During the course of her address to the sailors assembled, the queen said:

This is a solemn moment in the history of the Navy. You are bidding farewell to one Colour and are about to pay honour to another ....

I have no doubt that my Colour is in very good hands .... During the Second World War and particularly during the Battle of the Atlantic, you most admirably fulfilled your responsibilities to the Crown, to your country, and to the free world.

I now commend to your keeping this Colour. I know that you will guard it faithfully and the ideals for which it stands, not only in war but also during the peace, which we all hope so sincerely will ever continue. Remember always that, although it comes from me, it symbolizes not only loyalty to your Queen but also to your country and service. As long as these three loyalties are in your hearts, you will add lustre to the already great name of the Royal Canadian Navy.Footnote 18

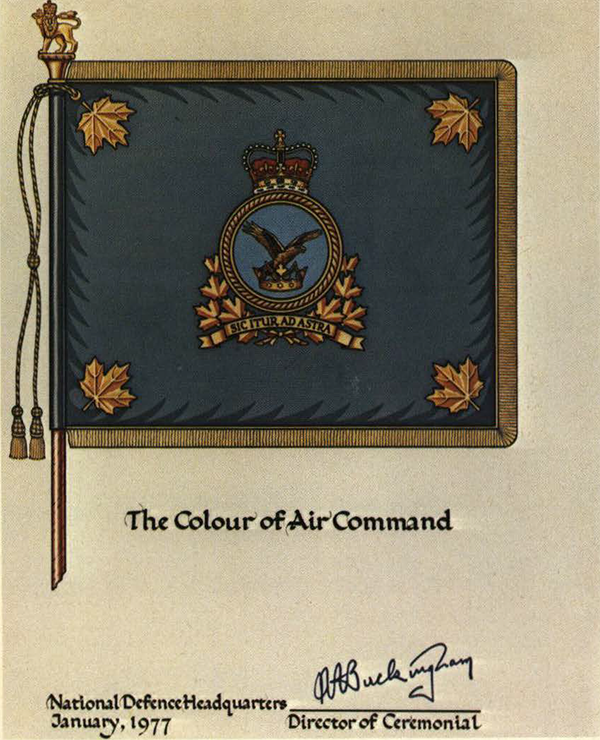

The Royal Canadian Air Force received its only sovereign's colour in 1950 together with the colour of the RCAF, the latter being comparable to a regimental colour. Both were consecrated and presented in the name of King George VI on Parliament Hill, Ottawa, on the king's birthday, 5 June 1950, by the Governor-General, Viscount Alexander of Tunis. The RCAF was the first of the Royal Air Forces to be granted, as a service, the privilege of carrying the king's colour. Those presented earlier were to particular components of the Royal Air Force.Footnote 19

Besides being the only sovereign's colour the air force has ever had, it having been designated "queen's colour" in 1952 in spite of its bearing the royal cypher of the recently deceased King George VI, it is of unusual design for an air force sovereign's colour.

The Royal Air Force ensign of light blue with the Union Flag at the hoist and the red-white-blue roundel in the fly was authorized in 1920. The Royal Canadian Air Force inherited the same privilege for its establishment in 1924. When the Royal Air Force began to receive its series of king's colours in 1948, the design was based on that of the ensign, that is, the Union Flag at the hoist, the royal cypher in the centre and the roundel in the fly, all on a field of light blue. But the Royal Canadian Air Force chose to have its king's colour designed in the army tradition, the Union Flag with the crown and royal cypher in the centre, thus adhering to the regulations first set down in 1747. The second colour of the RCAF is a light blue flag bearing the crown-and-eagle badge of the air force in the centre and a golden maple leaf in each corner.

These colours are still extant today after more than a quarter century. Each of the three stands of colours occupies an honoured place: one in the RCAF Officers' Mess, Gloucester Street, Ottawa; one in the Officers' Mess of Air Command, CFB Winnipeg; and the third in the Black Forest Officers' Mess Canadian Forces Europe, at Lahr, Germany.

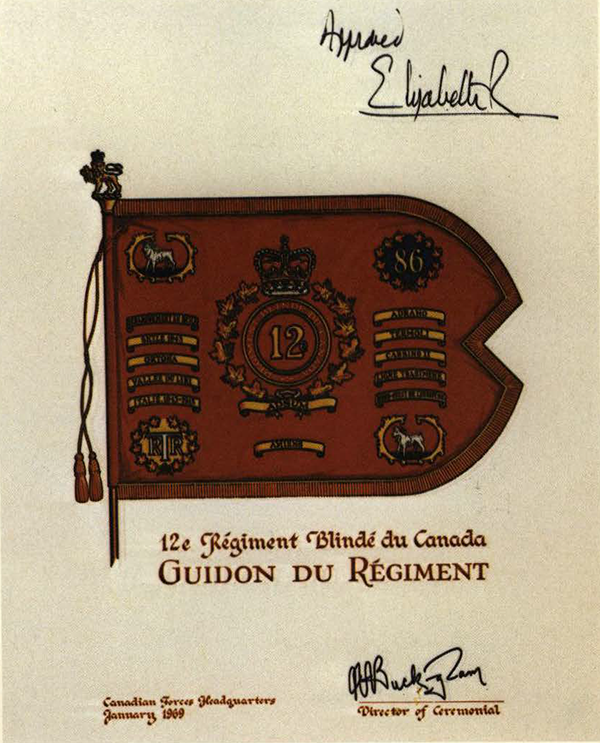

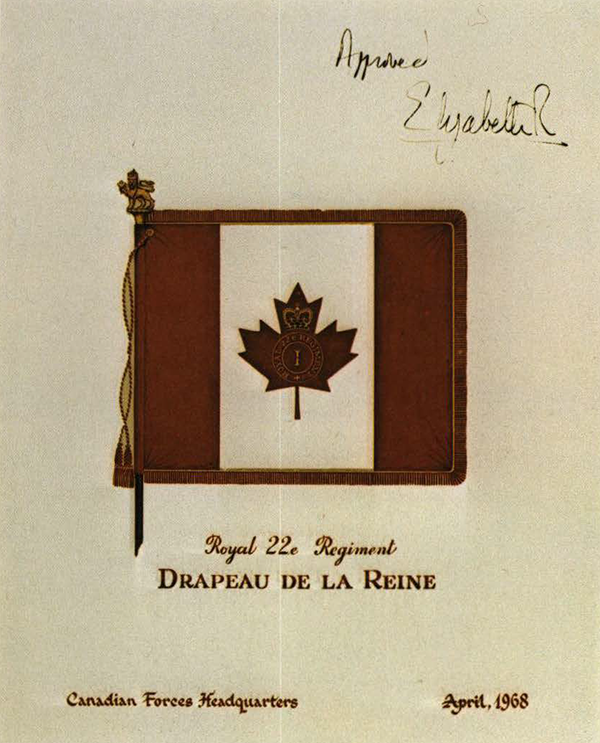

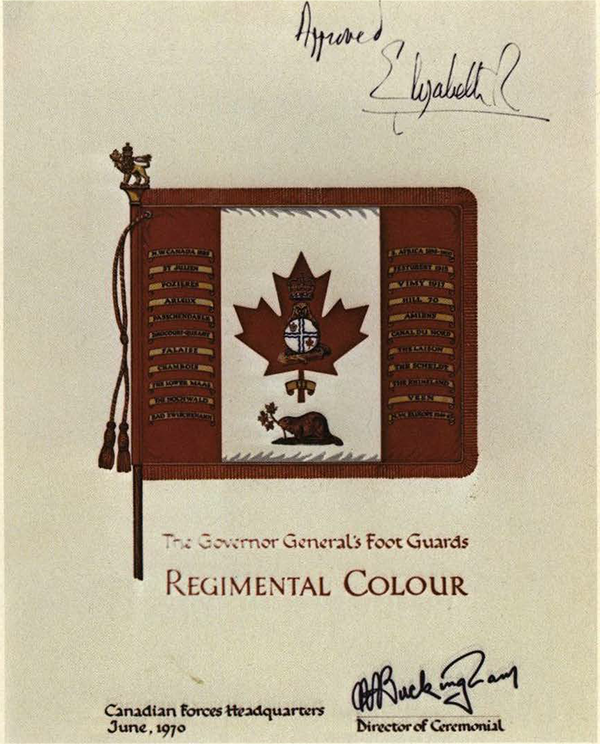

Unlike the air force and the navy, this situation did not arise in the army, organized as it was, and is, on a regimental basis, each unit having its own customs, traditions and colours. In 1968, Her Majesty approved the issue of new colours "to all Canadian infantry units and guards regiments which are entitled to carry them."Footnote 20 This process has been going on apace ever since, with the queen's colour being based on the design of the Maple Leaf Flag, replacing the Union Flag design traditionally employed for infantry units other than guards regiments. This reflects the custom established for infantry line regiments in the mid-eighteenth century whereby the sovereign's colour is based on the design of the national flag.Footnote 21

The queen's, or first, colour symbolizes the unit's loyalty to the crown. Authorization to possess a queen's colour can be granted only by the reigning sovereign and may be presented to a unit, command or Service only by the sovereign or her representative. The term itself first appeared in the British army in "Regulation for the Uniform Clothing of the Marching Regiments of Foot, their Colours, Drums, Bells of Arms, and Camp Colours, 1747," which stated: "The Kings or First Colour of every Regiment or Battalion is to be the Great Union."Footnote 22

The second, or unit, or regimental colour is probably the most cherished possession of a fighting force. This is because it embodies a whole spectrum of ideas, beliefs and emotions which together may be characterized as "the spirit of the regiment." The regimental colour symbolizes in a very visible way the pride a man feels in serving in a unit whose reason for being is one of worth, the proud heritage of those of the regiment who have gone before, and the record of achievement of the regiment, perhaps enshrined on the colour in the battle honours displayed within its folds. There is a mystique about the colours which constantly reminds every officer and man how dependant he is on his comrades-in-arms and makes it extremely difficult for him in battle to fail in his duty, and as often as not spurs him on to undreamed of exploits of valour.

Something of what the regimental colour means to the soldier may be gathered from an account given in the memoirs of James II, telling of the assault on Etampes in 1652 in the time of Louis XIV of France:

... Turenne's own regiment went on in the face of both armies ... ; and without any manner of diversion, or so much as one cannon-shot to favour them, they came up to the attack. Notwithstanding the continual fire that was made at them, both from the work and the wall of the town, they marched on without firing one single hot; the captains themselves taking the Colours in their hands, and marching with them at the head of their soldiers till they were advanced to the work ... ; and then at one instant poured in their shot and came up to push of pike with so much gallantry and resolution, that they beat out the enemy, and lodged themselves upon the work ....

It was universally confessed by all who were then present, that they never saw so daring an action. Marshal Turenne himself, and the most experienced officers of the army, were all of opinion, that it had been impossible for them to have done so much, if their Colours had not been always in their view.Footnote 23

In the journal of a seventeen-year-old ensign of the 34th Regiment of Foot a glimpse is seen of what the colours meant when Wellington met Napoleon's army in Portugal in 1811:

Our gallant and worthy general, riding along our front, said, 'Are you all ready?' 'Yes, sir.' 'Unease your colours and prime and load.' ... As I took the King's colour in charge being senior ensign, the major said, 'Now my lads, hold those standards fast, and let them fly out when you see the enemy.'Footnote 24

The forerunners of colours may be traced to the distant past when primitive men identified their leaders and forces in war with some form of totem on a staff or pole. The same purpose is to be seen in the elaborate eagle standards of the Roman legions. In the Middle Ages, the leaders in war were generally noblemen and, in their garb of mail or armour, identified themselves with banners and pennons bearing marks or devices from their coats of arms.

By the early seventeenth century the traditionally basic units, the companies, each with its own colour, were being gathered into regiments often called by the name of the colonels who raised them. Each regimental officer irrespective of rank also commanded his own company in the regiment and the company colours bore devices derived from the colonel's arms. Individual company colours still remain in guards regiments today. It was not until the regulations of 1747 that a colonel of the British army was forbidden to place "his Arms, Crest, Device or Livery on any part of the Appointments of the Regiment under his command."Footnote 25

The colours, when carried in battle, served two practical purposes — identification and place of concentration. A military writer nearly two centuries ago explained the reason for carrying the colours in the field:

Flags, banners, pencils, and other ensignes, are of great antiquity; their use was, in large armies, to distinguish the troops of different nations or provinces; and in smaller bodies, those of different leaders, and even particular persons, in order that the prince and commander in chief might be able to discriminate the behaviour of each corps or person; they also served to direct broken battalions or squadrons where to rally, and pointed out the station of the king, or those of the different great officers, each of whom had his particular guidon or banner, by which means they might be found at all times, and the commander in chief enabled from time to time to send such orders as he might find necessary to his different generals.Footnote 26

With the advent of more advanced weaponry, the long-established custom of carrying regimental colours in action, ceased. In the Zulu War in 1879, casualties in defence of the colours of the 24th Foot (the South Wales Borderers) brought public condemnation of the practice. Two years later, a similar situation arose for the 58th Foot (the Northamptonshire Regiment) in the engagement at Laing's Nek, South Africa. This was the last time in the force of the British Empire that regimental colours were carried in action, with one exception — Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry.Footnote 27

When the clouds of war rolled over Europe in the summer of 1914, Canada as a loyal member of the Empire responded to the threat. One response was the raising of a new regiment, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, named for the popular daughter of the Governor-General, the Duke of Connaught. Princess Patricia, appointed honorary colonel of the regiment, personally fashioned a colour of red and royal blue, fringed in gold, technically a camp colour, but one which soon took on the full character of a regimental colour. There is probably no more famous colour in the Canadian Forces.

In August, 1914, before the regiment proceeded overseas, Princess Patricia presented her colour to her regiment at Ottawa, and the commanding officer promised that it would be guarded "with their lives and that it would always remain with the regiment."Footnote 28 That promise was most faithfully kept.

The colour now affectionately known as the "Ric-A-Dam-Doo," was carried to France in December, 1914, and always flew over regimental head-quarters. Early in May, 1915, those headquarters were in front-line trenches and it was in that exposed position that the colour was torn by shrapnel and small arms fire. But the inspiration of the Princess's colour to the troops that day "enabled them to hold out against terrible odds with no support on either flank."Footnote 29

In January, 1919, at Mons, Belgium, this colour, which had survived five years of trench warfare, and on the march in France was always carried by an officer with an appropriate escort and with proper marks of respect paid by all troops met, was consecrated as the regimental colour. A month later, at Bramshott, England, Princess Patricia, now colonel-in-chief, presented a laurel wreath of silver gilt to be borne on the regimental colour. It bears this inscription:

To The P.P.C.L.I.

From the Colonel-in-Chief

PATRICIA

In Recognition Of Their Heroic

Services in the Great War 1914-1918

The laurel had been won at a frightful cost; only forty-four of the 1,098 originals were on parade that day.Footnote 30

The Ric-A-Dam-Doo, pray what is that?

'Twas made at home by Princess Pat.

It's Red and Gold and Royal Blue;

That's what we call the Ric-A-Dam-Doo.Footnote 31

It was the introduction of standing armies in the seventeenth century and their basic organization into regiments which led to the widespread use of regimental colours. In the British army it was the regulation of 1747 which set the pattern of both design and usage as they stand today.

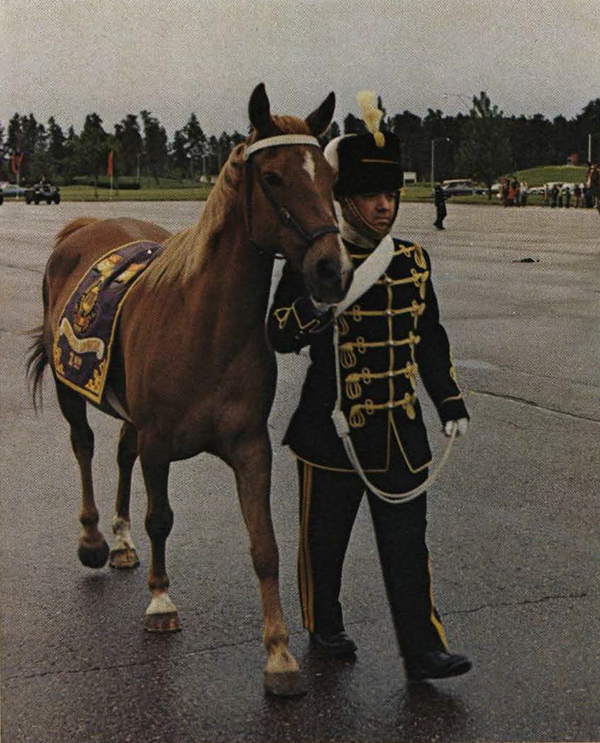

There were three distinct kinds of regimental banners — standards, guidons and colours. Standards are authorized for household cavalry and dragoon guards only. The Governor-General's Horse Guards, of Toronto, which enjoys the status of dragoon guards, is the only regiment in the Canadian Forces today that carries a standard. The standard was a very large flag flown by armies in medieval times. It was not intended to be carried in battle but rather to stand or be planted before the commander's tent, hence the name, standard.

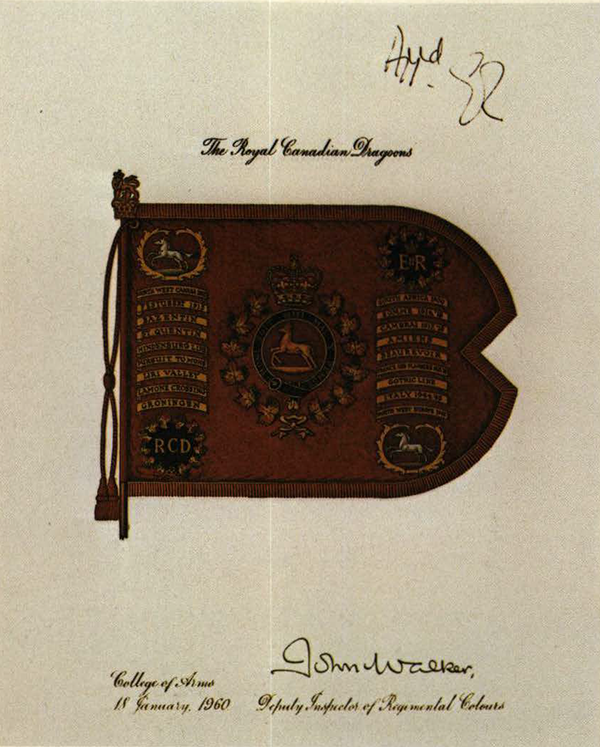

The guidon, derived from the old French word guydhomme, the flag borne by the leader of horse, was authorized for regiments of cavalry such as dragoons, and is swallow-tailed. A dictionary of 1780 defined the word as, "a French term for him that carries the standard in the guards, or 'Gens d'Armes', and signifies likewise the standard itself. It is now become common in England. He is the same in the horseguards, that the ensign is in the foot.'Footnote 32 Today guidons are used by armoured regiments, the successors of cavalry. Like the horse guards' standard the guidon is made of crimson silk damask.

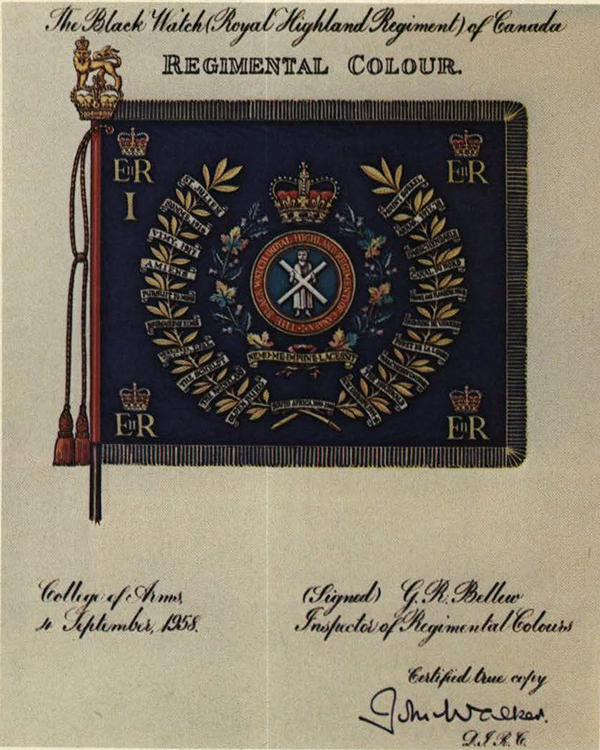

The regimental colour, the one specifically mentioned in the regulation of 1747, and which together with the sovereign's colour forms a stand of colours, was for foot guards and infantry line regiments. In the eighteenth century, it was known simply as the second colour. Although it soon took on the sobriquet regimental colour, this expression was not officially recognized until 1844.Footnote 33

A point of interest here is that for infantry line regiments, the old tradition of George II that the sovereign's colour should be based on the design of the national flag (in the regulation of 1747, this meant the Grand Union Flag, commonly called the Union Jack}, while the regimental colour should reflect the hues of uniform facings, has been maintained. But also in the tradition of the British army, it is the reverse for regiments of foot guards. In the latter case, the queen's colour is crimson, and regimental colour is similar to the Maple Leaf Flag, and the battle honours are displayed on both.Footnote 34

Flying squadrons of the Canadian Forces, after completion of twenty-five years service, or having earned the sovereign's appreciation for especially outstanding operations, are eligible to carry a squadron standard. An air force standard is a rectangular flag of light blue silk and bears the battle honours won by the squadron. Its institution came about in this way. During the Second World War, in 1943, the Royal Air Force marked its twenty-fifth anniversary. To commemorate the milestone, King George VI inaugurated the award of squadron standards, and thirty squadrons of the Royal Air Force were honoured in that wartime anniversary year.Footnote 35

In 1958, the award of flying squadron standards was extended to the Royal Canadian Air Force. The first unit to qualify was the 400 Squadron and the presentation took place at RCAF Station Downsview by the lieutenant-governor of Ontario, the Honourable J.K. MacKay on 10 June 1961.Footnote 36

In a general way this is the Story of the development of queen's and second colours in the Canadian Forces, following as they do in the wake of the much longer established customs of the British Services. However, as is to be expected, many diversions and exceptions to established practice have occurred, and some of these anomalies are of long standing.

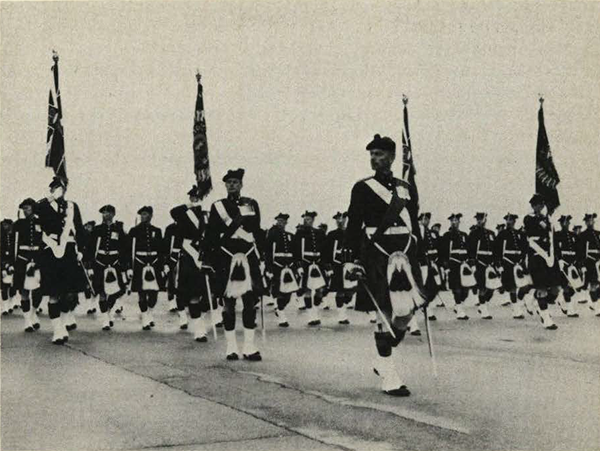

The colours of 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry, being marched on board a Boeing CC 137 transport aircraft at Winnipeg as the battalion proceeded on peacekeeping duty in Cyprus, 5 October 1972. Note the silver-gilt laurel wreath honouring the regiment for its gallantry in the Great War, 1914-1918, presented by Her Royal Highness the Princess Patricia, colonel-in-chief, in 1919. The ribbon is that of the United States presidential Distinguished Unit Citation, awarded for the Patricia's fight at Kapyong, Korea, in April, 1951.

The Royal Regiment of Canadian Artillery carries no colours, in the usual sense of the word. The guns are its colours. On ceremonial occasions the guns are accorded the same marks of respect as the standards, guidons and colours of other units. The reason behind this long-held tradition is related to the gunners' motto, ubique, meaning everywhere, that is, that the artillery has been present in just about every campaign.

The custom of the guns being the colours dates from the eighteenth century and the Royal Artillery's practice of that time of designating the largest gun of an artillery train as the flag gun, that is, the piece accorded the honour of bearing the equivalent of the sovereign's colour. This evolved into the guns themselves being regarded as the colours of the artillery.Footnote 37

Regiments of infantry with a rifle tradition, that is, the rifle regiments also have no queen's nor regimental colours, but for a different reason emanating from their historic role in the field. The rifles, who wore green uniform clothing with black buttons and black cross belts, did so to keep as low a profile as possible, the better to blend into the environment. As sharpshooters and skirmishers out ahead of the infantry of the line, it was their task to take advantage of every vestige of cover in rapid advance. Hence, no colours were carried in battle to advertise their presence. Today, the rifles still do not carry colours; battle honours won are displayed on the drums,Footnote 38 and, in some units, on the cap badges.

Occasionally, a unit finds itself contravening the established order of colours as in the case of the Algonquin Regiment of Northern Ontario. This unit, though an infantry regiment, is the proud possessor of a guidon presented about the same time in 1965 as the regiment was converted from the armoured role.Footnote 39

Although units take great pains to ensure the safety of their colours, accidents sometimes do occur. On 6 December 1917 when the ammunition ship Mont Blanc collided with another ship in Halifax harbour, there was great loss of life in the city. A side-light of the tragic explosion was the damage sustained by Wellington Barracks above HMC dockyard where the colours of the Royal Canadian Regiment were buried in the rubble. They were recovered.Footnote 40

In the church of St. Mary Magdalene, Picton, Ontario, a sovereign's colour is laid up together with the bare pike which once held a second colour. In 1960, the regimental colour of the Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment was stolen from its case in the officers' mess. It has not been recovered.Footnote 41

On 18 April 1975 at Fort York Armoury, Toronto, a stand of colours was handed over to the Queen's York Rangers by the lieutenant-governor of Ontario, the Honourable Pauline M. McGibbon. Both colours have a badge with a shield for the main device bearing the words "Queen's Rangers 1st Amerns." These are the oldest colours still extant in Canada, which belonged to a forbear of a regiment active in the Canadian Forces today, the Queen's York Rangers (1st American Regiment).

These are the colours that were carried by the Queen's Rangers (1st Americans) commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel John Graves Simcoe in the War of the American Revolution (1775-1783). Known as the Simcoe Colours, they may have been used by a later unit of the Queen's Rangers after the war when Simcoe became the first lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada. These ancient colours, now carefully restored, spent the better part of two centuries in the Simcoe family home, Wolford Lodge, in Devon, England, where they were acquired by interested Canadians some fifty years ago.Footnote 42

During the life of a colour, there are three basic ceremonies — consecration, presentation, and laying-up or depositing of the colours. Because of the meaning of the colours, these ceremonial occasions are always carried out with dignity and reverence, and with colourful military precision and pageantry, usually out of doors.

On Dominion Day, 1972, the Governor-General's Foot Guards were presented with new colours on Parliament Hill by the Governor-General, the Right Honourable Roland Michener, who was also honorary colonel of the regiment. The regiment was drawn up on the lawn beneath the Peace Tower. Detachments of the Canadian Grenadier Guards of Montreal and the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa, were also on parade. After the royal salute and His Excellency's inspection of his foot guards, the old colours were trooped and then marched off the parade ground to the tune of "Auld Lang Syne." This was followed by divine service in which the new colours were consecrated. The following order of service is typical of the ceremony of consecration of the colours in the Canadian Forces.Footnote 43

The Service of Consecration of Colours

Commanding Officer: Reverend Sir on behalf of the Governor-General's Foot Guards, we ask you to bid God's blessing on these Colours.

Chaplain: We are ready to do so.

Chaplain: Forasmuch as men at all times have made for themselves signs and emblems of their allegiance to their rulers, and of their duty to uphold those laws and institutions which God's providence has called them to obey, we, following this ancient and pious custom are met together before God to ask His blessing on these Colours, which are to represent to us our duty towards our Sovereign and our Country. Let us, therefore, pray Almighty God of His mercy to grant that they may never be unfurled, save in the cause of justice and righteousness, and that He may make them to be to those who follow them, a sign of His presence in all dangers and distresses, and so increase their faith and hope in Him, who is King of Kings and Lord of Lords.

Let us pray

Our help is in the Name of the Lord.

Response: Who hath made Heaven and Earth.

Chaplain: The Lord be with you.

Response: And with Thy spirit.

Chaplain: Almighty and everlasting God, we are taught by Thy Holy Word that the hearts of Kings are in Thy rule and governance, and that Thou dost dispose and turn them as it seemeth best to Thy Godly wisdom, we humbly beseech Thee so to dispose and govern the heart of Elizabeth, Thy Servant, Our Queen and Governor, that in all her thoughts, words and works, she may ever seek Thy honour and glory, and study to preserve Thy people committed to her charge in wealth, peace and Godliness. Grant this, O merciful Father, for Thy Son's sake, Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen

O Lord our God, who from Thy throne beholdest all the Kingdoms of the earth, have regard unto our land, that it may continue a place and a people who serve Thee to the end of time. Guide the governments of our great Commonwealth and Empire, and grant that all who live beneath our flag may be so mindful of that threefold cross, that they may work for the good of others according to the example of Him who died in the service of men, Thy Son, our Saviour, Jesus Christ. Amen

Remember O Lord what Thou has wrought in us, and not what we deserve, and as Thou has called us to Thy service, make us worthy of our calling through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen

Then shall the Commanding Officer lead the Regiment in an Act of Dedication.

Commanding Officer: To the Service of God and the hallowing of His Holy Name.

Response: We dedicate ourselves afresh.

Commanding Officer: To the maintenance of honour and the sanctity of man's plighted word.

Response: We dedicate ourselves afresh.

Commanding Officer: To the protection of all those who pass to and fro on their lawful occasions.

Response: We dedicate ourselves afresh.

Commanding Officer: To the preservation of order and good government.

Response: We dedicate ourselves afresh.

Commanding Officer: To the hallowed memory of our comrades, whose courage and endurance and undying lustre to our emblems.

Response: We dedicate our Colours.

Commanding Officer: In continual remembrance of our solemn oath and in token of our resolve faithfully and truly to keep it to the end.

Response: We dedicate our Colours.

The Act of Consecration.

Chaplain: (Laying his hands on the Colours): In the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, we do consecrate and set apart these Colours, that they may be a sign of our duty toward our Queen and our Country in the sight of God. Amen

Let us Pray

All: Our Father who art in Heaven, Hallowed be Thy Name, Thy Kingdom come, Thy will be done, on earth as it is in Heaven. Give us this day our daily bread. And forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive them that trespass against us. And lead us not into temptation. But deliver us from evil, for Thine is the Kingdom, the power and the glory, forever and ever. Amen.

Chaplain: O Lord, who rulest over all things, accept we beseech Thee our service this day. Bless what we have blessed in Thy Name. Let Thy gracious favour rest upon those who shall follow the Colours now about to be committed to their trust.

Give them courage and may their courage ever rest on their sure confidence in Thee. May they show self-control in the hour of success, patience in the time of adversity; and may their honour lie in seeking the honour and glory of Thy great Name.

Guide the counsels of those who shall lead them and sustain them by Thy help in time of need. Grant they may all so faithfully serve Thee in this life, that they fail not finally to obtain an entrance into Thy heavenly Kingdom through the merits of Thy Blessed Son, Jesus Christ, our Lord. Amen

The Blessing

May God who has called you to this service enable you to fulfil it; may the Father make you strong and tranquil in the knowledge of His love; may the Lord Christ bestow upon you the courage of His gentleness and the steadfastness of His brave endurance; may the Holy Spirit grant you that the self-control which comes from the gift of His wisdom, and may the Blessing of God, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, be upon you now and always. Amen

Following the actual presentation, the personage making the presentation (normally the sovereign or her representative), customarily addresses the assembled troops. The thoughts expressed usually take the form of a charge to the unit and it is here that the recruit begins to understand the true meaning of the colours.

On 21 October 1953 the Royal Newfoundland Regiment received new colours from the hands of their honorary colonel and lieutenant-governor of the province, Sir Leonard Outerbridge. These were the first colours to be presented to a Canadian regiment in the reign of Queen Elizabeth II. Sir Leonard's address ended with this admonishment: "Guard them well and carry them proudly as the symbols of the great traditions and honours which have been won by those who have gone before you."Footnote 44

A century earlier on 12 July 1849, a ceremony took place at Winchester Barracks, England, which shows the timelessness of the presentation of the colours. The regiment being honoured, the Royal Welch Fusiliers, had just returned from more than a decade of service in British North America, having been stationed at places as far apart as Halifax and Annapolis, Quebec and Montreal, and Kingston and London in Canada West. The presentation of new colours was made by Queen Victoria's consort, Prince Albert. The drill of that day sounds very much as it does today:

The regiment, being drawn up in line with the old colours in the centre, received His Royal Highness with the usual honours, the flank companies were then brought forward so as to form three sides of a square, to the centre of which the new colours were brought under escort and piled on an altar of drums.Footnote 45

After the consecration service conducted by the chaplain-general, Prince Albert proceeded to give his charge to the regiment in the language of his day:

Soldiers of the Royal Welch Fusiliers! — The ceremony which we are performing this day is a most important and to every soldier a most sacred one; it is the transmission to your care and keeping of the colours which are henceforth to be borne before you, which will be the symbol of your honour and your rallying points in all moments of danger.

Receive these colours — one emphatically called 'The Queens,' let it be a pledge of your loyalty to your Sovereign and of obedience to the laws of your country; the other — more especially the 'Regimental' one — let that be a pledge of your determination to maintain the honour of your regiment. In looking at the one you will think of your Sovereign; in looking at the other you will think of those who have fought, bled, and conquered before you!Footnote 46

It is a symbol of the continuity in the affairs of men that more than a century later, the prince consort's great-great-granddaughter, Queen Elizabeth II, would be presiding over a similar presentation. It was a happy coincidence, too, that the regiment she honoured on the Plains of Abraham 23 June 1959 is the Canadian regiment allied to the Royal Welch Fusiliers, the Royal 22e Regiment.

In a very moving ceremony Her Majesty, as colonel-in-chief, spoke to her French-speaking regiment in a way that is still remembered with affection by the "Van Doos" on parade that day. These were her words:

Commanding Officers, Officers, Non-Commissioned Officers and Privates:

I am pleased to be in Quebec City with my French Canadian regiment; I am proud of the regiment and take pleasure in presenting it with new colours.

I am aware of your history which dates back to the beginning of the First World War. French Canadians decided at that time to form a regiment recalling their origins. The regimental insignia bears the motto Je me souviens (I remember). It is a moving tribute to the country of your forebears.

On the colours that I have just presented to you are inscribed the names of French towns in whose liberation you participated. What emotion you must have felt in liberating people of your own blood, and what joy they must have felt in welcoming the descendants of the French men and women who three centuries before had set sail for Canada.

You have had a short but glorious history. During the two world wars and the operations in Korea the regiment forged a noble tradition of honour, courage and sacrifice.

I have been able to see today that in peacetime you maintain the same laudable tradition of discipline and dress, for which I warmly congratulate you.

I know that my father, King George VI had the highest regard for his French Canadian regiment. He clearly proved this be becoming its colonel-in-chief in 1938, and I took pleasure in succeeding him in this position.

I thank you with all my heart for the faithful dedication that you have shown me in the past and on which I know I can always rely.

The alliance that exists between you and the Royal Welsh Fusiliers, another brave regiment of which I am colonel-in-chief, gives me great joy.

I entrust these new colours to you with complete confidence. Your past makes me certain that your will defend them as your predecessors defended the old colours — fearlessly and faultlessly.Footnote 47

Colours are the embodiment, the visual symbol, of loyalty to the crown, to the nation, and to the unit in which one serves. But, in spite of the aura of veneration and mystique which surrounds the colours, they are at the same time material things and their use does come to an end. In earlier times, they were subject to capture by the enemy as in the case of the defending forces at Louisbourg, some of whose surrendered colours are to be seen in St. Paul's Cathedral in London to this day. Since colours are no longer carried in battle, and barring loss by fire or theft, they are eventually disposed of by laying-up or by depositing them in some safe place, perhaps a church. Whatever the case, colours go into retirement always with great respect and appropriate ceremony.

Closely related to the traditional laying-up and depositing of the colours is the regimental church. From coast to coast in Canada, there have grown up over the years very close bonds between individual units and particular congregations.

After the Great War of 1914-1918, the colours of the old 79th Cameron Highlanders of Canada were marched off to the tune, "The March of the Cameron Men," and laid up in First Presbyterian Church, Winnipeg. This is the spiritual home of Winnipeg's Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada where "the people" and the regiment share the beauty and the meaning of the Cameron Memorial Chapel and the Cameron stained glass memorial window.Footnote 48

The laying-up ceremony occurs when a colour becomes no longer serviceable and is to be replaced by a new colour. Once a colour has been laidup, it is not brought back into service again.

On the other hand, the ceremony of depositing a colour takes place when a unit is disbanded, or made dormant, or transferred to the supplementary order of battle. Such colours remain the property of the crown and may be recovered should the unit be reconstituted in its former status.Footnote 49 A good illustration of the two procedures is the case of the Regiment of Canadian Guards who had one stand of colours laid up, and another deposited, in the span of a few short years.

Formation of this regular force regiment was authorized in 1953. The colours of the 1st Battalion were presented in 1957 by the Governor-General, the Right Honourable Vincent Massey, those of the 2nd Battalion in 1960 by Mr. Massey's successor, General the Right Honourable Georges P. Vanier.

In the course of a few years the colours, fashioned of fine silk, needed replacement, largely owing to being paraded daily by the public duties detachment of the regiment while performing the celebrated ceremony, the changing of the guard, on Parliament Hill, Ottawa. The Regiment of Canadian Guards carried out this duty each summer for eleven years commencing in 1959. On 5 July 1967 on Parliament Hill, as part of the celebration of Canada's centenary of confederation, Her Majesty the Queen, colonel-in-chief of the regiment, presented new colours to both guards' battalions in a joint ceremony in which guidons and colours were also presented to four other units — the Ontario Regiment, the Sherbrooke Hussars, the 1st Hussars, and the Cameron Highlanders of Ottawa.

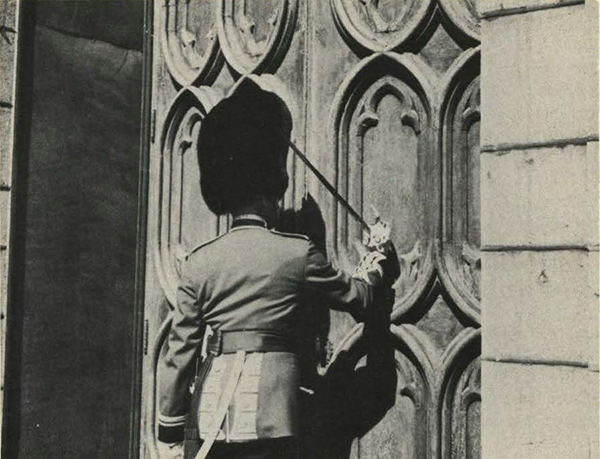

In due course, the old worn colours of the guards were laid-up in impressive ceremonies. In August, 1969 they were marched to their respective sanctuaries, the colours of the 1st Battalion on August 31 to Christ Church Cathedral and those of the 2nd Battalion, a week earlier, to Notre Dame Basilica, both in Ottawa. On both occasions the ancient ritual of gaining entry to a sacred sanctuary was exercised — the troops already inside the church, the colour party approached the door and the parade adjutant with drawn sword used the hilt to strike the door the traditional three times. The clergy on the inside answered the summons and bid the colour party enter, the armed escort leaving their bearskins on their head to leave their weapon hands free to defend the colours in the ancient manner.Footnote 50 From the chancel steps, the colours were received by the clergy and placed on the altar. The old colours of the Regiment of Canadian Guards were now laid-up.Footnote 51 But within the year, the new colours too, would be retired, this time by being deposited, rather than laid-up.

In an army reorganization of 1970, the Canadian Guards were removed from the regular force. On the anniversary of the invasion of Normandy 6 June 1970, to the tune of "Soldiers of the Queen," the guards marched to Parliament Hill to troop their colour for the last time. After bearing a message from their colonel-in-chief, the queen, they marched off to Rideau Hall on Sussex Drive in Ottawa where the wife of the Governor-General, Mrs. Roland Michener, had personally selected the place in Government House where the colours of the regiment were to repose, the foyer. The ceremony and divine service now over, the colours of the Regiment of Canadian Guards are said to be deposited, rather than laid-up, in the hope they will one day see service again.Footnote 52

An officer of the 2nd Battalion, the Regiment of Canadian Guards, performing the ancient ceremony of striking the door of the sanctuary with the hilt of his sword requesting admittance to lay up the old colours of the regiment, Notre Dame Basilica, Ottawa, August, 1969.

Another occasion when colours are deposited is when they are temporarily lodged for safekeeping during the time a unit is away on active service. One sunny day in March, 1940, large crowds, sensing an historic occasion in the life of their city, gathered outside Mewata Armouries, Calgary, to see the colours of the Calgary Highlanders emerge from the barracks to be escorted to a church sanctuary "for the duration." Once formed up, the battalion swung along Seventh Avenue with fixed bayonets guarding the colours. A capacity congregation saw the regiment deposit its colours in the Anglican Cathedral of the Redeemer. In handing over the colours to the church authorities, the words of the commanding officer, followed by the placing of the colours on the altar, the "present arms" and the playing of "God Save the King," as recorded by the regimental historian, somehow communicated the significance of that impressive ceremony to all ranks — "These consecrated Colours, formerly carried in service of King and Empire, I now deliver into your hands for safe custody within these walls for the duration of the war."Footnote 53

There is little doubt, however, that what is best known about the colours is that most stirring of ceremonies, trooping the colour. From very early times, the colours or standards, or their more primitive equivalents, led armies into battle and were the rallying points in time of danger. It was essential that the soldier know what the colour looked like so that he would know his duty almost instinctively. He soon learned to look upon and treat the colour with the highest respect. To do so, the soldier had to see his colour at close range, and that is what trooping the colour is all about. It is the ceremonial parading of the colour with armed escort slowly up and down before the regiment drawn up for the purpose. Every soldier of the regiment, or of the company before there were regiments, took a good look at the colour so that he would recognize it in the din and heat of battle and so know his place and rallying point.Footnote 54

Trooping the colour can be traced to the sixteenth century and a simple routine known as lodging the colour. Lodging in this sense is still used today. Just as the queen's and regimental colours are kept today (sometimes cased in a leather container, sometimes on display behind glass) in the officers' mess, so in earlier times the colours were lodged for safekeeping in the ensign's quarters or lodging at the end of the day's parade or, during a campaign, at the end of the day's fighting. With the colours under armed escort, this rather informal ceremony was carried out before the troops with dignity and respect. The same was true when the colours were "sent for" the next day. Simple as the ceremony of lodging the colour was, it evolved into a much more elaborate ritual until, in 1755, it became by British army regulation part of the regular guard mounting drillFootnote 55. The term trooping gradually replaced lodging and is derived from "the troop," a beat of the drum ordering the troops "to repair to the place of rendez-vous, or to their colours."Footnote 56

In the ceremony of trooping the colour, only one colour is carried, except at the presentation of new colours where it is customary to troop the old sovereign's and regimental colours together before they are marched off the parade ground. The queen's colour is trooped only when a guard is mounted for Her Majesty, members of the royal family, the Governor-General, or a lieutenant-governor, or in a ceremonial parade in honour of the queen's birthday.

The trooping of the second or regimental colour is carried out on a great variety of occasions in Canada today. For example, on 6 June 1970, at CFB Gagetown, two battalions of the Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, trooped their colours to mark their departure from the regular order of battle. On several occasions the 48th Highlanders of Canada have performed the ceremony at the Canadian National Exhibition Stadium and Maple Leaf Gardens in Toronto for capacity audiences, the proceeds being donated to worthy charitable organizations.Footnote 57 The guidon of the British Columbia Dragoons, presented in 1967 by Her Royal Highness, Princess Alexandra of Kent, is trooped annually in one of three cities of the Okanagan Valley, Vernon, Kelowna and Penticton.Footnote 58

Finally, to return to the meaning of the colours, this is brought home in a very special way to the officers and men of one militia regiment. Every year, in the spring, the Royal Montreal Regiment reconsecrates its colours in the regimental church, St. Matthias Westmount, "to the memory of all our war dead."Footnote 59

Page details

- Date modified: