Economic and Social Inclusion infographic – 2021

Alternate formats

Figure 1 – Text version

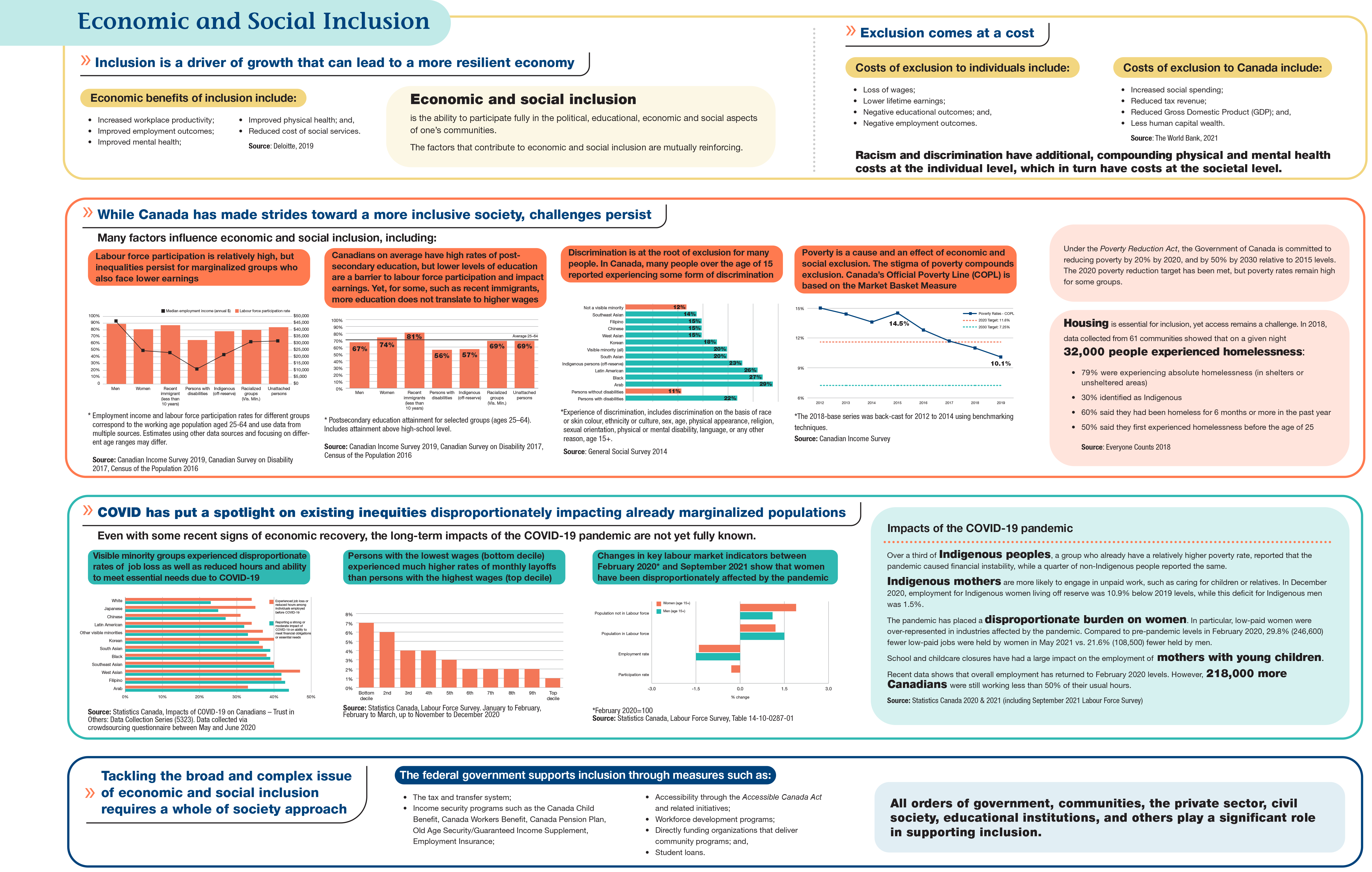

Economic and Social Inclusion

Inclusion is a driver of growth that can lead to a more resilient economy

Economic benefits of inclusion include:

- increased workplace productivity

- improved employment outcomes

- improved mental health

- improved physical health, and

- reduced cost of social services

Source: Deloitte, 2019.

Economic and social inclusion is the ability to participate fully in the political, educational, economic and social aspects of one’s communities. The factors that contribute to economic and social inclusion are mutually reinforcing.

Exclusion comes at a cost

Costs of exclusion to individuals include:

- loss of wages

- lower lifetime earnings

- negative educational outcomes, and

- negative employment outcomes

Costs of exclusion to Canada include:

- increased social spending

- reduced tax revenue

- reduced Gross Domestic Product (GDP), and

- less human capital wealth

Source: The World Bank, 2021.

Racism and discrimination have additional, compounding physical and mental health costs at the individual level, which in turn have costs at the societal level.

While Canada has made strides toward a more inclusive society, challenges persist

Many factors influence economic and social inclusion, including:

Labour force participation is relatively high, but inequalities persist for marginalized groups who also face lower earnings

Diagram 1 text: Labour force participation and individual employment earnings for selected groups (ages 25 to 64)| Groups (Ages 25 to 64) | Labour force participation rate | Median employment income (annual $) | Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 89% | $47,500 | 2019 |

| Women | 81% | $29,900 | 2019 |

| Recent immigrants (less than 10 years) | 87% | $28,600 | 2019 |

| Persons with disabilities | 65% | $18,800 | 2017 |

| Indigenous (off-reserve) | 78% | $27,400 | 2019 |

| Racialized groups (Visible Minorities) | 80% | $35,100 | 2016 |

| Unattached persons | 84% | $35,600 | 2019 |

*Employment income and labour force participation rates for different groups correspond to the working age population aged 25 to 64 and use data from multiple sources. Estimates using other data sources and focusing on different age ranges may differ.

Source: Canadian Income Survey 2019, Canadian Survey on Disability 2017, Census of the Population 2016.

Canadians on average have high levels of post-secondary education, but lower levels of education are a barrier to labour force participation and impact earnings. Yet, for some, such as recent immigrants, more education does not translate to higher wages

Diagram 2 text: Postsecondary education attainment for selected groups (ages 25 to 64)| Group (ages 25 to 64) | Postsecondary education attainment (%) |

|---|---|

| Men | 67% |

| Women | 74% |

| Recent immigrants (less than 10 years) | 81% |

| Persons with disabilities | 56% |

| Indigenous (off-reserve) | 57% |

| Racialized groups (Visible Minorities) | 69% |

| Unattached persons | 69% |

* Postsecondary education attainment for selected groups (ages 25 to 64). Includes attainment above high-school level.

Source: Canadian Income Survey 2019, Canadian Survey on Disability 2017, Census of the Population 2016.

Discrimination is at the root of exclusion for many people. In Canada, many people over the age of 15 reported experiencing some form of discrimination

Diagram 3 text: Percentage of the population (age 15 and above) that reported experiencing discrimination| Group (age 15 and above) | Percentage that reported experiencing discrimination |

|---|---|

| Not a visible minority | 12% |

| Southeast Asian | 14% |

| Filipino | 15% |

| Chinese | 15% |

| West Asian | 15% |

| Korean | 18% |

| Visible minority (all) | 20% |

| South Asian | 20% |

| Indigenous persons (off-reserve) | 23% |

| Latin American | 26% |

| Black | 27% |

| Arab | 29% |

| Persons without disabilities | 11% |

| Persons with disabilities | 22% |

*Experience of discrimination, includes discrimination on the basis of race or skin colour, ethnicity or culture, sex, age, physical appearance, religion, sexual orientation, physical or mental disability, language, or any other reason, age 15+.

Source: General Social Survey, 2014

Poverty is a cause and an effect of economic and social exclusion. The stigma of poverty compounds exclusion. Canada’s Official Poverty Line (COPL) is based on the Market Basket Measure

Diagram 4 text: Poverty reduction targets based on Canada's Poverty Reduction Strategy, 2020 and 2030 (Canada's Official Poverty Line, Market Basket Measure, 2018-base)| Year | Poverty Rates based on Canada’s Official Poverty Line | 2020 Target | 2030 Target |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 15.0% | 11.60% | 7.25% |

| 2013 | 14.4% | 11.60% | 7.25% |

| 2014 | 13.6% | 11.60% | 7.25% |

| 2015 | 14.5% | 11.60% | 7.25% |

| 2016 | 12.8% | 11.60% | 7.25% |

| 2017 | 11.7% | 11.60% | 7.25% |

| 2018 | 11.0% | 11.60% | 7.25% |

| 2019 | 10.1% | 11.60% | 7.25% |

*The 2018-base series was back-cast for 2012 to 2014 using benchmarking techniques.

Source: Canadian Income Survey

Under the Poverty Reduction Act, the Government of Canada is committed to reducing poverty by 20% by 2020, and by 50% by 2030 relative to 2015 levels. The 2020 poverty reduction target has been met, but poverty rates remain high for some groups.

Housing is essential for inclusion, yet access remains a challenge. In 2018, data collected from 61 communities showed that on a given night 32,000 people experienced homelessness:

- 79% were experiencing absolute homelessness (in shelters or unsheltered areas)

- 30% identified as Indigenous

- 60% said they had been homeless for 6 months or more in the past year

- 50% said they first experienced homelessness before the age of 25

Source: Everyone Counts 2018

COVID has put a spotlight on existing inequities disproportionately impacting already marginalized populations

Even with some recent signs of economic recovery, the long-term impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are not yet fully known

Visible minority groups experienced disproportionate rates of job loss as well as reduced hours and ability to meet essential needs due to COVID-19

Diagram 5 text: Self-reported financial and employment impact of COVID-19 by visible minority groups, May and June 2020| Groups | Experienced job loss or reduced hours among individuals employed before COVID-19 | Reporting strong or moderate impact of COVID-19 on ability to meet financial obligations or essential needs |

|---|---|---|

| White | 34% | 23% |

| Japanese | 35% | 25% |

| Chinese | 31% | 27% |

| Latin American | 34% | 32% |

| Other visible minorities | 37% | 33% |

| Korean | 40% | 36% |

| South Asian | 37% | 39% |

| Black | 38% | 39% |

| Southeast Asian | 40% | 40% |

| West Asian | 47% | 42% |

| Filipino | 42% | 43% |

| Arab | 33% | 44% |

Source: Statistics Canada, Impacts of COVID-19 on Canadians – Trust in Others: Data Collection Series (5323). Data collected via crowdsourcing questionnaire between May and June 2020

Persons with the lowest wages (bottom decile) experienced much higher rates of monthly layoffs than persons with the highest wages (top decile)

Diagram 6 text: Average monthly layoff rates of employees by wage decile, 2020| Wage decile | Average monthly layoff rates |

|---|---|

| Bottom decile | 7% |

| 2nd decile | 6% |

| 3rd decile | 4% |

| 4th decile | 4% |

| 5th decile | 3% |

| 6th decile | 2% |

| 7th decile | 2% |

| 8th decile | 2% |

| 9th decile | 2% |

| Top decile | 1% |

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey. January to February, February to March, up to November to December 2020

Changes in key labour market indicators between February 2020* and September 2021 show that women have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic

Diagram 7 text: Changes in key labour market indicators between February 2020* and September 2021 for men and women age 25 to 64 (% change)| Gender | Labour force | Full-time employment | Part-time employment | Participation rate | Employment rate | Not in labour force |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (age 15 and above) | 1.5% | -1.2% | 7.5% | 0.0% | -1.5% | 1.1% |

| Women (age 15 and above) | 1.2% | 1.7% | -4.5% | -0.3% | -1.4% | 1.9% |

*February 2020=100

Source: Statistics Canada, Labour Force Survey, Table 14-10-0287-01

Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic

Over a third of Indigenous peoples, a group who already have a relatively higher poverty rate, reported that the pandemic caused financial instability, while a quarter of non-Indigenous people reported the same.

Indigenous mothers are more likely to engage in unpaid work, such as caring for children or relatives. In December 2020, employment for Indigenous women living off reserve was 10.9% below 2019 levels, while this deficit for Indigenous men was 1.5%.The pandemic has placed a disproportionate burden on women. In particular, low-paid women were over-represented in industries affected by the pandemic. Compared to pre-pandemic levels in February 2020, 29.8% (246,600) fewer low-paid jobs were held by women in May 2021 vs. 21.6% (108,500) fewer held by men.

School and childcare closures have had a large impact on the employment of mothers with young children.

Recent data shows that overall employment has returned to February 2020 levels. However, 218,000 more Canadians were still working less than 50% of their usual hours.

Source: Statistics Canada 2020 and 2021 (including September 2021 Labour Force Survey)

Tackling the broad and complex issue of economic and social inclusion requires a whole of society approach

The federal government supports inclusion through measures such as:

- the tax and transfer system

- income security programs such as:

- the Canada Child Benefit

- Canada Workers Benefit

- Canada Pension Plan

- Old Age Security

- Guaranteed Income Supplement

- Employment Insurance

- accessibility through the Accessible Canada Act and related initiatives

- workforce development programs

- directly funding organizations that deliver community programs, and

- student loans

All orders of government, communities, the private sector, civil society, educational institutions, and others play a significant role in supporting inclusion.