Consultations on the social and economic impacts of ageism in Canada: “What we heard” report

On this page

- Alternate format

- List of abbreviations

- Participating governments

- Acknowledgments

- Executive summary

- Introduction and disclaimer

- Background information on ageism

- Consultation methods

- General experiences with ageism

- Ageism and employment

- Ageism and health and health care

- Ageism and social inclusion

- Ageism and safety and security

- Ageism and media and social media

- Strategies to address ageism

- References

- Annex 1. Summary of consultation participation

- Annex 2. Subpopulation responses

- Annex 3. Programs, initiatives and strategies to address ageism identified in the ageism questionnaire

- Annex 4. Programs, initiatives and strategies to address ageism identified in the roundtable and stakeholder-led consultations

Alternate formats

Consultations on the social and economic impacts of ageism in Canada: “What we heard” report [PDF- 874 KB]

Large print, braille, MP3(audio), e-text and DAISYformats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- CARP

- Canadian Association of Retired Persons

- CPP/QPP

- Canada Pension Plan/Québec Pension Plan

- FADOQ

- Fédération de l'Âge d'Or du Québec

- FPT

- Federal, Provincial, and Territorial

- GIS

- Guaranteed Income Supplement

- OAS

- Old Age Security

- 2SLGBTQ+

- 2-Spirit, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and other identities

Participating governments

- Government of Ontario

- Government of Nova Scotia

- Government of New Brunswick

- Government of Manitoba

- Government of British Columbia

- Government of Prince Edward Island

- Government of Saskatchewan

- Government of Alberta

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Government of Northwest Territories

- Government of Yukon

- Government of Nunavut

- Government of Canada

Québec contributes to the Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Seniors Forum by sharing expertise, information and best practices. However, it does not subscribe to, or take part in, integrated federal, provincial, and territorial approaches to older adults. The Government of Québec intends to fully assume its responsibilities for older adults in Québec.

1. Acknowledgements

Prepared by Laura Kadowaki, Barbara McMillan, and Kahir Lalji (United Way British Columbia) for the Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors. The views expressed in this report may not reflect the official position of a particular jurisdiction.

2. Executive summary

Introduction

The Forum of Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Ministers Responsible for Seniors (Seniors Forum) has been working to address the social and economic impacts of ageism on older adults in Canada. The World Health Organization defines ageism as “the stereotypes (how we think), prejudice (how we feel) and discrimination (how we act) towards others or oneself based on age.” As a part of the FPT Seniors Forum’s work, feedback was sought from Canadians to better understand the impacts of ageism at the individual level, and at the community level. Participants provided feedback in 2 different ways: 1) by participating in a FPT Seniors Forum led roundtable consultation or a stakeholder-led consultation, or 2) by completing an ageism questionnaire. While ageism can be experienced by people of any age, the focus of the consultations and questionnaire was on ageism directed towards older adults. An older adult was defined as a person aged 55 and up.

As ageism is a complex topic, 5 themes were selected to focus on:

- employment

- health and health care

- social inclusion

- safety and security

- media and social media

Between September and November 2022 a total of 8 FPT Seniors Forum led roundtable consultations and 17 stakeholder-led consultations were hosted across Canada, providing participants with an opportunity to discuss ageism as it related to the 5 theme areas. The ageism questionnaire was available to respondents from August 15 to October 31, 2022, and a total of 2,920 complete responses were received. The questionnaire consisted of a series of close-ended questions, as well as opportunities to share personal stories about the impacts of ageism.

This “What We Heard” report summarizes input received from the FPT Seniors Forum led roundtable consultations and stakeholder-led consultations and the ageism questionnaire. This input will inform a subsequent Policy Options Report, to be submitted to FPT Ministers for their consideration, that will propose approaches, initiatives, and strategies to address ageism in Canada.

General experiences with ageism

In the ageism questionnaire, respondents were asked whether they had ever experienced ageism themselves. Approximately half (48.4%) of respondents responded yes. The most common settings in which respondents reported having experienced or seen ageism were public settings, workplace settings, and health care settings. Furthermore, over two-thirds of questionnaire respondents (69.9%) believed that ageism has increased in Canada since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

Ageism and employment

When discussing ageism and employment in the roundtable and stakeholder-led consultations, participants suggested stereotypical beliefs about older workers were causing significant harm to older workers. Stereotypical beliefs about older workers can make workplaces unwelcoming, contribute to employers not wanting to hire older workers, and cause older workers to doubt their abilities. Furthermore, societal expectations that one should retire at age 65 can cause older workers to feel pressured to retire. Participants also expressed concerns about discriminatory policies and practices in the workplace (for example, lack of accommodations for older workers, being excluded from extended health benefits). Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, participants observed how during the shift to remote working, some older workers struggled significantly due to being less familiar with the digital environment and employers not offering adequate supports to adapt to these changes.

In the ageism questionnaire, respondents expressed the most concern about 1) Discrimination against older job seekers in hiring processes, and 2) Older workers being fired, laid off, or forced to retire. These concerns were reflected in the many personal stories shared by respondents about older workers:

- struggling to find employment

- feeling pressured to retire

- being subjected to ageism in the workplace

- being fired, laid off, or forced to retire

Ageism and health and health care

Participants in the roundtable and stakeholder-led discussions were most concerned about ageist attitudes and behaviours by health care providers, and the negative impacts they can have on older adults. Common concerns included older adults being ignored or treated paternalistically, health care providers assuming that symptoms are just due to age, and older adults being denied care or provided with different treatments based on their age. Participants also discussed several barriers to accessing health care services that they viewed as examples of systemic ageism within health care: 1) transportation barriers, 2) telehealth and the digital divide, and 3) language and communication barriers. Finally, participants also discussed how ageism has contributed to the longstanding systemic neglect of long-term care facilities and home care services across Canada.

In the ageism questionnaire, the issues that clearly emerged as the most important concerns for respondents were:

- older adults being viewed as a burden on the health care system

- the lack of action to address issues affecting long-term care facilities or other group living settings

- the lack of action to address issues with general health care services for older adults

Respondents also shared many personal stories that illustrated the negative health impacts of ageist attitudes and behaviours by health care providers. Examples were provided of older adults being misdiagnosed, neglected, or denied treatments. Many respondents who shared a story believed that they or a loved one had received different or poor care because of their age, and that older patients are viewed as disposable or unworthy of receiving care.

Ageism and social inclusion

Roundtable and stakeholder-led consultation participants discussed how ageist attitudes within society hinder the social inclusion of older adults. Participants stated that stereotypical beliefs, ignoring and excluding older adults, and discriminatory actions can make older adults feel disrespected or unwelcome within society. Participants also remarked on how ageism intersects with other forms of prejudice such as sexism, racism, ableism, and homophobia. Participants were concerned about 2 social inclusion issues that had significantly intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic: 1) social isolation and loneliness and 2) the digital divide. Generally, respondents perceived that more resources and supports need to be provided to strengthen social support networks and offer inclusive activities in order to prevent social isolation and loneliness. Participants also emphasized that the assumption by society, government, and organizations that everyone is able to participate digitally is ageist and excludes segments of the older adult population.

Key concerns that were identified in the ageism questionnaire included 1) Government programs, policies and service delivery that do not adequately consider the needs of older adults and 2) The lack of recognition of the contributions that older adults make to society. In the personal stories shared by respondents, the lack of accessible and inclusive community spaces and activities for older adults was the most common theme. Respondents also shared stories about the negative impacts that financial insecurity and the lack of aging in place supports have on the social inclusion of older adults.

Ageism and safety and security

The most commonly discussed safety and security topic at the consultations was senior abuse. Participants believed that ageism contributes to societal beliefs that senior abuse is less important than other types of abuse. Participants also observed there are very limited resources available for responding to these types of crimes and supporting victims. Another concern participants highlighted was that homes and communities are often poorly designed to meet the needs of older adults, with little consideration given to accessibility and safety.

The top safety and security concerns of questionnaire respondents were:

- lack of access to affordable, suitable, and adequate housing for older adults

- physical environments that are not well designed to meet the needs of older adults

- negative views about older adults that can contribute to abuse and neglect

In the personal stories, a major theme was the importance of access to quality affordable housing for older adults. Clear links were made by respondents between housing insecurity and financial insecurity. The stories also illustrated the need for communities to be age-friendly in design and have effective mechanisms in place for reporting senior abuse and ensuring accountability.

Ageism and media and social media

In the roundtable and stakeholder-led discussions, the most prominent topic of discussion was how media and social media perpetuate ageism within society. Older adults are often missing from media and social media, and when they are included, they are usually portrayed stereotypically or negatively. An additional concern raised by the participants is the unintended exclusion of older adults as information, news, and social interactions are shared online.

The top media and social media concerns identified by respondents in the questionnaire were: 1) The lack of representation of older adults and their views in the media, and 2) Discussions or descriptions in media/social media that frame older adults as a burden or drain on society. The stories shared by respondents focused on the stereotypical portrayals and underrepresentation of older adults in media and social media.

Strategies to address ageism

In the ageism questionnaire, the 2 most important theme areas that respondents identified to target for strategies, initiatives, or programs to address ageism were: 1) health and health care, and 2) social inclusion. In the open-ended feedback from the questionnaire and the feedback from the roundtable and stakeholder-led consultations, many of the recommended strategies to address ageism overlapped with the health and health care and social inclusion themes. The main strategies described by consultation participants and questionnaire respondents were:

- implementing campaigns to promote ageism awareness or celebrate aging and the contributions of older adults

- building intergenerational connections through intergenerational programs and housing models

- offering digital technology training to older adults

- increasing funding for non-profit and community-based organizations, which were recognized as providing many social, educational, intergenerational, and aging support programs that promote the social inclusion of older adults

- implementing strategies to prevent the isolation of older adults (for example, outreach, providing information in age-friendly formats, access to public transportation)

- designing age-friendly communities

- developing aging in place supports and innovative housing models as alternatives to long-term care facilities

- reforms to modernize health care systems to better meet the complex health care needs of older adults (for example, improve training on caring for older adults, implement more multidisciplinary care models, increase length of appointments)

- implementing strategies to encourage the hiring and retention of older workers

- promoting positive depictions of older adults in the media and social media

- implementing senior abuse prevention initiatives

Introduction and disclaimer

The Forum of Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Ministers Responsible for Seniors (Seniors Forum) has been working to address the social and economic impacts of ageism on older adults in Canada. Under the Ageism priority, the Forum has determined a set of deliverables to be issued during their work cycle 2018 to 2021, including this "What We Heard" report. As a part of this work, FPT Seniors Forum led roundtable consultations, stakeholder-led consultations, and a questionnaire were undertaken to better understand the impacts of ageism at the individual level, and at the community level. A Discussion Guide was prepared to provide background information for both consultation participants and questionnaire respondents on the topic of ageism. While ageism can be experienced by people of any age, the focus of the consultations and questionnaire was on ageism directed towards older adults. An older adult was defined as a person aged 55 and up. As ageism is a complex topic, 5 themes were selected to focus on:

- employment

- health and health care

- social inclusion

- safety and security

- media and social media

This “What We Heard” report summarizes input received from the FPT Seniors Forum led roundtable consultations, stakeholder-led consultations, and ageism questionnaire. This input, along with this report, will inform a subsequent Policy Options Report, to be submitted to FPT Ministers for their consideration, that will propose approaches, initiatives, and strategies to address ageism in Canada.

The content of this document does not necessarily represent the views of the Government of Canada, provincial and territorial governments, the Forum of FPT Ministers, participating departments and agencies or government employees.

Background information on ageism

The World Health Organization defines ageism as “the stereotypes (how we think), prejudice (how we feel) and discrimination (how we act) towards others or oneself based on age.”1 Stereotypes are beliefs that are generalized towards a whole group of people. If older adults accept stereotypes and negative views about themselves, self-ageism can occur. Age is just one aspect of a person’s identity, and experiences of ageism can be influenced by other characteristics, such as gender or ethnicity.

Ageism can take many forms. Some examples of ageism include:

- jokes about a person’s age and making fun of older adults in general

- negative or stereotypical portrayals of older adults in the media

- workplace or health care policies that discriminate against older adults

- older adults being patronized, ignored, or insulted, and

- assuming that an older adult is incapable of making their own decisions

Ageism is an important area of study, as research shows it is associated with a number of negative outcomes for older adults, such as reduced longevity, poverty and financial insecurity, poor health outcomes, and loss of self-esteem and confidence.1,2

Consultation methods

Roundtable and stakeholder-led consultations

Roundtable and stakeholder-led consultations: Methods and analysis

Between September and November 2022, FPT Seniors Forum led roundtable consultations and stakeholder-led consultations on ageism were hosted across Canada. Consultations were hosted either virtually or in-person. All consultations addressed ageism as it related to the 5 themes. The following questions guided the discussions for each theme:

- what are the most significant ageism issues related to each of the themes?

- what impacts has the COVID-19 pandemic had on ageism in each of the themes?

- what efforts are currently working to address ageism related to each of the themes?

- what more could be done (for example, new strategies, initiatives, or programs) to best address ageism related to each of the themes, and who should be involved?

The roundtable consultations were hosted by the FPT Seniors Forum and conducted by a contracted facilitator. Stakeholder organizations were also invited to host their own consultations. A Consultation Toolkit was developed and made available to help guide stakeholder organizations that wished to host their own consultations. Notetakers at the roundtable and stakeholder-led consultations recorded key points from the discussions, and the notes were submitted to the FPT Seniors Forum. Analysis of the notes from the roundtable and stakeholder-led consultations was conducted using the qualitative data analysis program NVivo. Key themes were identified from the notes for each topic.

Roundtable and stakeholder-led consultations: sample

A total of 8 FPT Seniors Forum led roundtable consultations were hosted:

- Newfoundland and Labrador

- Alberta

- British Columbia

- Saskatchewan

- Ontario

- Manitoba

- Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Prince Edward Island

- Yukon, Northwest Territories, and Nunavut (see Annex 1, Table 1A, for more details)

Seven of the roundtables were conducted virtually and 1 in-person. A total of 108 people participated in the roundtables and the number of participants at each consultation ranged from 8 to 20.

A total of 17 stakeholder-led consultations were also hosted across the country by organizations in:

- British Columbia (n=6)

- Alberta (n=4)

- Ontario (n=2)

- Québec (n=2)

- Manitoba (n=1)

- Nova Scotia (n=1)

- Prince Edward Island (n=1) (refer to Annex 1, Table 1B, for more details)

A total of 457 people participated in the stakeholder-led consultations and the number of participants at each consultation ranged from 6 to 90. Two of the stakeholder-led consultations targeted specific populations of older adults (Indigenous Elders and immigrant older adults). Targeted outreach was conducted by the FPT Seniors Forum to 8 Indigenous organizations to encourage their participation; the FPT Secretariat met virtually with 2 of these organizations to discuss the consultations and anecdotal evidence was received from 1 group, though formal engagement was not conducted.

Roundtable and stakeholder-led consultations: limitations

A few limitations of the consultation approach should be mentioned. The majority of FPT Seniors Forum led roundtables took place virtually, which may have limited the ability of the participants to engage with each other in the discussions. As the stakeholder-led consultations were dependant on the interest of stakeholder groups, some provinces and territories and population groups were underrepresented. In the feedback from stakeholder-led consultation organizers, it was also noted that there was inadequate time to discuss all of the themes and questions at some of the consultations.

Ageism questionnaire

Questionnaire: methods and analysis

The ageism questionnaire was available to respondents from August 15th to October 31st, 2022. The questionnaire was open to anyone with an interest in the topic of ageism and could be answered in English or French. The questionnaire was available online, or a paper survey could be downloaded for printing and filled out and mailed in. A total of 2,920 complete responses were received: 1,387 responses in English (47.5%) and 1,533 responses in French (52.5%). A further 73 stories and submissions were received about ageism via email and the online Share Your Story Platform (53 in English [72.6%], 20 in French [27.4%]).

Descriptive statistics (for example, counts, percentages) were calculated for close-ended questions using the statistical program SPSS. Cross-tabulations were also calculated to present the responses of specific sub-populations. All percentages were rounded to one decimal place. The responses for open-ended questions were analyzed using the qualitative data analysis program NVivo. Key themes were identified from these stories and comments. Due to the large number of stories received, while all were reviewed, it was only possible to include a small number of these in the report. To protect the privacy of respondents, any names of individuals, organizations, or locations were removed from the stories that are included in the report.

Questionnaire: sample characteristics

Questionnaire responses were received from all provinces and territories except for Nunavut. Most of the participants resided in Québec, Ontario, or British Columbia. Table 1 provides a breakdown of the respondents’ province or territory of residence (the total populations of the provinces and territories are also provided for comparison). Based on comments from the respondents, the strong response from Québec (n=1,625, 55.7%) was likely related to efforts by the advocacy organization FADOQ (previously known as Fédération de l'Âge d'Or du Québec) to promote the survey to their members. Three-quarters of the respondents lived in an urban community (n=2,187, 74.9%), one-quarter lived in a rural community (n=714, 24.5%), and a small number (n=19, 0.7%) preferred not to answer.

| Province or territory | Population (2021) | % of Canadian population (2021) | # of respondents | % of respondents |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Québec | 8,501,833 | 23.0 | 1,625 | 55.7 |

| Ontario | 14,223,942 | 38.5 | 615 | 21.1 |

| British Columbia | 5,000,879 | 13.5 | 295 | 10.1 |

| Alberta | 4,262,635 | 11.5 | 134 | 4.6 |

| Manitoba | 1,342,153 | 3.6 | 74 | 2.5 |

| Nova Scotia | 969,383 | 2.6 | 48 | 1.6 |

| Saskatchewan | 1,132,505 | 3.1 | 39 | 1.3 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 510,550 | 1.4 | 21 | 0.7 |

| New Brunswick | 775,610 | 2.1 | 16 | 0.5 |

| Prince Edward Island | 154,331 | 0.4 | 15 | 0.5 |

| Yukon | 40,232 | 0.1 | 7 | 0.2 |

| Northwest Territories | 41,070 | 0.1 | 4 | 0.1 |

| Nunavut | 36,858 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.0 |

- Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

The questionnaire was open to respondents of all ages. The majority of respondents were aged 55 and up (n=2,685, 92.0%), with the largest number of respondents in the 65 to 74 age group (refer to Figure 1). When asked if they identified with the term “senior” (aîné) or “older adult” (personne âgée), there was no clear preference among respondents (refer to Table 2). However, among English respondents, a larger number preferred the term “older adult” over “senior”, while among French respondents, a larger number preferred the term “senior” (aîné) over “older adult” (personne âgée). Most commonly, respondents identified they were participating in the questionnaire due to having been affected by ageism as an older adult (n=1,280, 43.8%), as someone who had witnessed ageism towards an older adult (n=1,125, 38.5%), or in their role as an unpaid family or friend caregiver or volunteer (n=769, 26.3%) (refer to Table 3).

Figure 1. Age of respondents

- Notes: Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding. 6 respondents (0.2%) preferred not to answer.

Figure 1 – Text version

Figure 1 shows a bar graph representing the ages of survey respondents.

- There were 11 respondents aged 18 to 24 representing 0.4% of total respondents

- There were 45 respondents aged 25 to 34 representing 1.5% of total respondents

- There were 60 respondents aged 35 to 44 representing 2.1% of total respondents

- There were 114 respondents aged 45 to 54 representing 3.9% of total respondents

- There were 620 respondents aged 55 to 64 representing 21.2% of total respondents

- There were 1,337 respondents aged 65 to 74 representing 47.2% of total respondents

- There were 616 respondents aged 75 to 84 representing 21.1% of total respondents

- There were 72 respondents aged 85 and older representing 2.5% of total respondents

Underneath the bar graph it is noted that percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding. It was also noted that 6 respondents (0.2%) preferred not to answer.

| Terminology | Total # of responses | % of total responses | # of English responses | % of English responses | # of French responses | % of French responses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older adult / personne âgée | 571 | 19.6 | 434 | 31.3 | 137 | 8.9 |

| Senior / aîné | 741 | 25.4 | 218 | 15.7 | 523 | 34.1 |

| Either senior or older adult | 812 | 27.8 | 457 | 32.9 | 355 | 23.2 |

| Other | 129 | 4.4 | 77 | 5.6 | 52 | 3.4 |

| Does not apply | 633 | 21.7 | 187 | 13.5 | 446 | 29.1 |

| Prefer not to answer | 34 | 1.2 | 14 | 1.0 | 20 | 1.3 |

- Notes: Total sample size was 2,920 (1,387 responses in English and 1,533 responses in French). The most preferred “Other” terms were “adult”, “elder”, or “person”. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

| Role | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Someone who has been affected by ageism as an older adult | 1,280 | 43.8 |

| Someone who has witnessed ageism against older adults | 1,125 | 38.5 |

| A caregiver or a volunteer (not paid for the service provided) | 769 | 26.3 |

| An employee or representative of an organization representing and supporting older adults (for example, advocacy organization, senior centre, community services) | 345 | 11.8 |

| A person paid to be involved in the provision of direct care to older adults in the home, a group living setting (for example, long-term care home, assisted living facility), or other health care settings | 133 | 4.6 |

| A stakeholder/partner from fields such as academia, health administration, finance, law, and/or any level of government (federal, provincial/ territorial, municipal, and Indigenous) | 135 | 4.6 |

| Other | 211 | 7.2 |

| Not applicable or Prefer not to answer | 435 | 14.9 |

- Notes: Percentages do not add up to 100% due to the option to select multiple responses. The most common “Other” response provided was as an “older adult who had not experienced ageism” (n=178).

More females (n=2,064, 70.7%) participated in the questionnaire than males (n=828, 28.4%). A small number of respondents identified as non-binary (n=11, 0.4%), two-spirit (n=2, 0.1%), preferred to self identify (n=2, 0.1%), or preferred not to answer (n=13, 0.4%). Information on the percentage of Indigenous and minority group respondents is summarized in Table 4.

| Respondent group | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Person with a disability | 294 | 10.1 |

| Ethno-cultural or a visible minority group | 181 | 6.2 |

| Official language minority community | 131 | 4.5 |

| 2SLGBTQ+ community | 117 | 4.0 |

| Indigenous peoples | 51 | 1.7 |

- Notes: Among Indigenous respondents, 30 identified as Métis citizen, 19 as First Nations, and 2 as Inuk/Inuit. A member of an official minority community is considered to be from a French-speaking community outside Québec or from an English-speaking community in Québec.

Generally, respondents tended to have high levels of education, with about 6 in 10 respondents (n=1,713, 58.7%) having an undergraduate or graduate degree (refer to Table 5).

| Highest level of education completed | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Less than high school graduation | 33 | 1.1 |

| High school diploma or equivalent | 275 | 9.4 |

| Apprenticeship or trades certificate or diploma | 104 | 3.6 |

| Some college, CEGEP or university | 389 | 13.3 |

| College, CEGEP, or university certificate | 385 | 13.2 |

| College or university undergraduate degree | 826 | 28.3 |

| Graduate level degree or higher | 887 | 30.4 |

| Prefer not to answer | 21 | 0.7 |

- Notes: Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Over two-thirds of respondents were retired (n=1,970 67.5%) (refer to Table 6).

| Employment status | Number | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Retired | 1,970 | 67.5 |

| Working full-time | 470 | 16.1 |

| Working part-time | 232 | 7.9 |

| Self-employed | 116 | 4.0 |

| Unemployed | 58 | 2.0 |

| Student | 10 | 0.3 |

| Other | 52 | 1.8 |

| Prefer not to answer | 12 | 0.4 |

- Notes: Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding. The most common “Other” responses provided were “On disability or medical leave” (n=26) or a “Family or friend caregiver, homemaker, or volunteer” (n=20).

Questionnaire: limitations

Some limitations of the ageism questionnaire should be noted. First, certain groups of older adults were underrepresented in the questionnaire sample:

- males

- individuals with lower education backgrounds

- the oldest old (considered to be older adults aged 85 and up)

- members of ethno-cultural or visible minority groups

- Indigenous peoples

- older adults from certain provinces and territories

In addition, residents of Québec were significantly overrepresented. Second, due to the questionnaire being primarily accessible online, older adults who do not have access to or prefer not to use the internet were likely underrepresented.

General experiences with ageism

Questionnaire feedback: general experiences with ageism

Questionnaire respondents were asked whether they had ever experienced ageism themselves. A total of 1,413 respondents (48.4%) answered yes (refer to Figure 2). Among older adult respondents there was an age gradient, with a higher proportion of the 55-64 age group (52.6%) reporting experiencing ageism compared to the 65 to 74 (48.4%), 75 to 84 (43.0%), and 85 and up (37.5%) age groups. A higher proportion of female respondents reported having experienced ageism than male respondents (51.9% vs. 39.1%). Compared to the overall sample, a larger proportion of Indigenous (64.7%), ethno-cultural or visible minority (60.8%), 2SLGBTQ+ (62.4%), and people living with a disability (68.0%) also reported having experienced ageism. There was a notable educational gradient, with more individuals with higher levels of education reporting having experienced ageism (refer to Annex 2 for full results for subpopulations). Respondents were also asked whether stereotypes or negative views about aging had ever negatively influenced their perception of themselves. A total of 1,169 respondents (40.0%) responded yes (refer to Figure 3). For the subpopulations, similar patterns were seen for this question as for the previous question (refer to Annex 2).

Figure 2. Have you ever experienced ageism yourself? (n=2,920)

- Notes: 7 respondents (0.2%) preferred not to answer. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 2 – Text version

Figure 2 shows a pie chart that represents responses to the question: “Have you ever experienced ageism yourself?” with n= 2,920 responses.

- A segment of the chart representing 1,413 answers, approximately 48.4% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “Yes”

- A segment of the chart representing 1,090 answers, approximately 37.3% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “No”

- A segment of the chart representing 410 answers, approximately 14.0% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “Not sure”

Underneath the pie chart it is noted that 7 respondents, representing approximately 0.2% of total respondents indicated they prefer not to answer. It is noted that percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding

Figure 3. Have stereotypes or negative views about aging ever negatively influenced your perception of yourself? (n=2,920)

- Notes: 72 respondents (2.5%) selected “not applicable” or preferred not to answer. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 3 – Text version

Figure 3 shows a pie chart that represents responses to the question: “Have stereotypes or negative views about aging ever influenced your perception of yourself?” with n= 2,920 responses.

- A segment of the chart representing 1,169 answers, approximately 40.0% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “Yes”

- A segment of the chart representing 1,373 answers, approximately 47.0% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “No”

- A segment of the chart representing 306 answers, approximately 10.5% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “Not sure”

Underneath the pie chart it is noted that 72 respondents, representing approximately 2.5% of total respondents indicated they prefer not to answer. It is noted that percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Among those respondents who were completing the questionnaire on behalf of an older person (n=760), 41.4% (n=315) reported that the older person had experienced ageism and 45.4% (n=345) reported that they thought stereotypes or negative views had impacted the perceptions of that older person (refer to Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 4. If you are completing this questionnaire on behalf of an older person (age 55+), has this person experienced ageism against older persons? (n=760)

- Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 4 – Text version

Figure 4 shows a pie chart that represents responses to the question: “If you are completing this questionnaire on behalf of an older person (aged 55+), has this person experienced ageism against older persons?” with n= 760 responses.

- A segment of the chart representing 315 answers, approximately 41.4% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “Yes”

- A segment of the chart representing 352 answers, approximately 46.3% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “No”

- A segment of the chart representing 93 answers, approximately 12.2% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “Not sure”

Underneath the pie chart it is noted that percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 5. If you are completing this questionnaire on behalf of an older person (age 55+), do you think stereotypes or negative views about aging ever negatively influenced the perception of themselves? (n=760)

- Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 5 – Text version

Figure 5 shows a pie chart that represents responses to the question: “If you are completing this questionnaire on behalf of an older person (aged 55+), do you think stereotypes or negative views about aging ever negatively influenced the perception of themselves?” with n= 760 responses.

- A segment of the chart representing 345 answers, approximately 45.4% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “Yes”

- A segment of the chart representing 293 answers, approximately 38.6% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “No”

- A segment of the chart representing 122 answers, approximately 16.1% of the total answers, indicated an answer of “Not sure”

Underneath the pie chart it is noted that percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

When respondents were asked if they had ever seen or been aware of ageism occurring against an older adult, 46.4% (n=1,355) reported they had seen ageism occur first-hand, 33.1% (n=966) reported they had not seen it but were aware of instances of it happening to people they knew, and 20.5% (n=599) reported they had not seen ageism occur and were not aware of it happening to anyone they knew. Respondents most frequently reported having seen or experienced ageism in public settings (39.9%), workplace settings (39.7%), and health care settings (35.0%) (refer to Figure 6).

Figure 6. Have you ever seen or experienced ageism in any of the following settings? (n=2,920)

- Note: Percentages do not add up to 100% due to the option to select multiple responses.

Figure 6 – Text version

Figure 6 shows a bar graph representing survey responses to the question “Have you seen or experienced ageism in any of the following settings ?” with n=2920 responses.

- 1,165 respondents, representing 39.9% of total respondents, indicated they had seen or experienced ageism in a public setting

- 1,160 respondents, representing 39.7% of total respondents, indicated they had seen or experienced ageism in a workplace setting

- 1,023 respondents, representing 35.0% of total respondents, indicated they had seen or experienced ageism in a health care setting

- 966 respondents, representing 33.1% of total respondents, indicated they had seen or experienced ageism in a home or social setting

- 846 respondents, representing 29.0% of total respondents, indicated they had seen or experienced ageism in a long-term care facility or group living setting

- 776 respondents, representing 26.6% of total respondents, indicated they had seen or experienced ageism in a media or social media setting

- 506 respondents, representing 17.3% of total respondents, indicated they had seen or experienced ageism in a government setting

- 49 respondents, representing 1.7% of total respondents, indicated they had seen or experienced ageism in another setting that was not listed

Underneath the bar graph it is noted that percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Questionnaire feedback: ageism and the COVID-19 pandemic

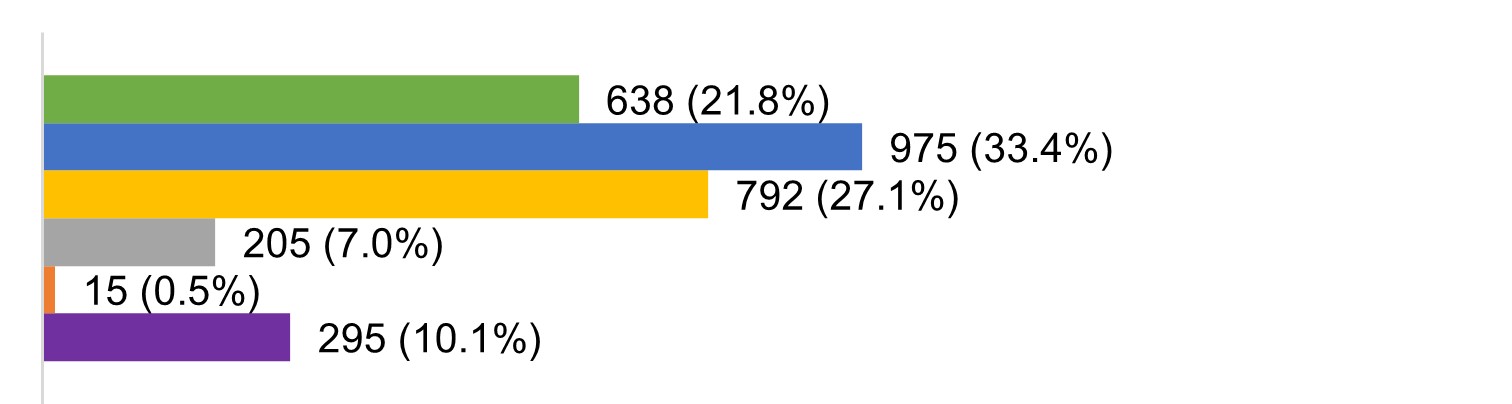

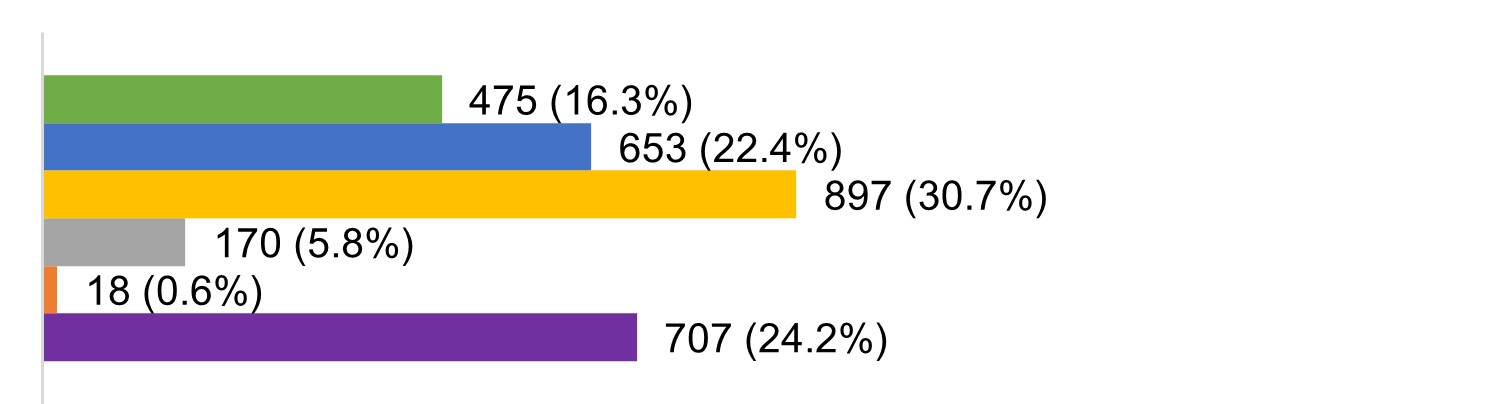

Figure 7 summarizes responses on the impact the COVID-19 pandemic has had on ageism in Canada. The majority of respondents (81.8%) agreed or strongly agreed the COVID-19 pandemic has brought increased attention to ageism. More than half of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that during the pandemic ageism has increased in health care settings (61.4%), long-term care or group living settings (61.2%), media and social media settings (70.2%), and public places (55.2%). Respondents were more ambivalent about the effects of the pandemic on ageism in the workplace, government, and home or social settings. Most respondents agreed or strongly agreed the pandemic has reduced the social inclusion of older adults (78.2%) and negatively impacted their safety and security (75.9%). Most respondents also agreed or strongly agreed the pandemic has increased intergenerational tensions (62.8%).

Figure 7. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on ageism in Canada

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought increased attention to ageism in Canada.

Ageism has increased in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ageism in the workplace has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ageism in health care settings has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ageism in long-term care facilities or group living settings has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ageism in the media and social media has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ageism in public places (for example, schools, grocery stores, services in general) has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ageism in government settings (for example, government service centre, government programs, municipal centre) has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ageism in the home or social settings has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The COVID-19 pandemic has decreased the social inclusion of older adults in society.

The COVID-19 pandemic has decreased the safety and security of older adults.

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in increased intergenerational tensions.

- Note: Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Figure 7 – Text version

Figure 7 is a series of bar graphs titled “Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on ageism in Canada”. These bar graphs show survey respondents’ answers regarding their level of agreement or disagreement with a series of statements.

- In response to the statement “The COVID-19 pandemic has brought increased attention to ageism in Canada” respondents answered as follows:

- 1,379 respondents, representing 47.2% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 1,009 respondents, representing 34.6% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 348 respondents, representing 11.9 % of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 109 respondents, representing 3.7% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 27 respondents, representing 0.9% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 48 respondents, representing 1.6% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “Ageism has increased in Canada during the COVID-19 pandemic” respondents answered as follows:

- 1,111 respondents, representing 38.0% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 932 respondents, representing 31.9% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 566 respondents, representing 19.4 % of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 135 respondents representing 4.6% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 11 respondents, representing 0.4% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 165 respondents, representing 5.7% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “Ageism in the workplace has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic” respondents answered as follows:

- 407 respondents, representing 13.9% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 527 respondents, representing 18.0% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 827 respondents, representing 28.3% of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 175 respondents, representing 6.0% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 20 respondents, representing 0.7% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 964 respondents, representing 33.0% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “Ageism in healthcare settings has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic” respondents answered as follows:

- 893 respondents, representing 30.6% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 898 respondents, representing 30.8% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 547 respondents, representing 18.7% of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 132 respondents, representing 4.5% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 13 respondents, representing 0.4% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 437 respondents, representing 15.0% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “Ageism in long-term care facilities or group living settings has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic” respondents answered as follows:

- 1,029 respondents, representing 35.2% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 759 respondents, representing 26.0% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 458 respondents, representing 15.7% of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 100 respondents, representing 3.4% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 15 respondents, representing 0.5% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 559 respondents, representing 19.1% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “Ageism in the media and social media has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic” respondents answered as follows:

- 986 respondents, representing 33.8% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 1,062 respondents, representing 36.4% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 512 respondents, representing 17.5% of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 111 respondents, representing 3.8% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 14 respondents, representing 0.5% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 235 respondents, representing 8.0% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “Ageism in public places (for example, schools, grocery stores, services in general) has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic” respondents answered as follows:

- 638 respondents, representing 21.8% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 975 respondents, representing 33.4% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 792 respondents, representing 27.1% of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 205 respondents, representing 7.0% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 15 respondents, representing 0.5% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 295 respondents, representing 10.1% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “Ageism in government settings (for example, government service centre, government programs, municipal centre) has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic” respondents answered as follows:

- 475 respondents, representing 16.3% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 653 respondents, representing 22.4% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 897 respondents, representing 30.7% of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 170 respondents, representing 5.8% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 18 respondents, representing 0.6% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 707 respondents, representing 24.2% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “Ageism in the home or social settings has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.” respondents answered as follows:

- 467 respondents, representing 16.0% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 892 respondents, representing 30.5% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 839 respondents, representing 28.7% of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 233 respondents, representing 8.0% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 21 respondents, representing 0.7% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 468 respondents, representing 16.0% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “The COVID-19 pandemic has decreased the social inclusion of older adults in society.” respondents answered as follows:

- 1,350 respondents, representing 46.2% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 934 respondents, representing 32.0% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 299 respondents, representing 10.2% of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 191 respondents, representing 6.5% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 37 respondents, representing 1.3% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 109 respondents, representing 3.7% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “The COVID-19 pandemic has decreased the safety and security of older adults.” respondents answered as follows:

- 1,349 respondents, representing 46.2% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 867 respondents, representing 29.7% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 328 respondents, representing 11.2% of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 216 respondents, representing 7.4% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 39 respondents, representing 1.3% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 121 respondents, representing 4.1% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

- In response to the statement “The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in increased intergenerational tensions.” respondents answered as follows:

- 897 respondents, representing 30.7% of total respondents, stated they strongly agreed

- 937 respondents, representing 32.1% of total respondents, stated they agreed

- 563 respondents, representing 19.3% of total respondents, stated they neither agreed nor disagreed

- 257 respondents, representing 8.8% of total respondents, stated they disagreed

- 35 respondents, representing 1.2% of total respondents, stated they strongly disagreed

- 231 respondents, representing 7.9% of total respondents, stated they were unsure or preferred not to answer

Underneath the bar graphs it is noted that percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

Ageism and employment

Introduction

An increasing number of older adults are now working in later life. Ageism may prevent older workers from finding a job or remaining in the workforce, and could lead to older workers being treated unfairly in the workplace. Research has shown that employers often believe stereotypes about older workers (for example, older workers are less productive, it is more difficult for older workers to learn new skills), which can lead to age-based discrimination.3 Including older adults in the workforce is good for individuals, businesses, and society. Researchers estimate that increasing the number of older workers in Canada could increase our economic performance by $56 billion.4

Roundtable and stakeholder-led consultation feedback

Societal beliefs about older workers

Common societal beliefs about older workers and retirement were recognized as deterring older adults from participating in the labour force. Within the workplace, participants reported that it is common for employers, managers, and co-workers to believe stereotypes about older workers (for example, older workers are less capable, less productive, unable to use technology, in poor health). These beliefs can make the workplace unwelcoming and contribute to employers not wanting to hire older workers. Self-ageism can occur when older workers begin to accept negative stereotypes about themselves, and this was also identified by participants as an important barrier to participation in the labour force. Participants discussed how stereotypes about older workers or experiencing a layoff or long period of unemployment can lead older adults to lose confidence in themselves and question their ability to contribute as an employee.

Employers not wanting to hire older workers was the most frequent point of discussion by participants, as employers may not want to hire older workers due to:

- stereotypical beliefs about their capabilities

- assumptions that older workers will not stay with the company for long

- concerns that older workers will be more costly

There are nuances to the situation though, with several participants noting that how welcoming employers are to older workers is affected by the physical demands of the job, labour availability, and organizational and occupational culture. Some participants believed that due to the current economic situation and labour shortages, job markets are improving for older workers. However, other participants disagreed, and it was noted that some of the jobs that are becoming available (for example, lower wage jobs, retail) may not be the types of jobs sought by most older workers.

Participants also discussed societal expectations around retirement (for example, retirement at age 65) and how these can deter the participation of older adults in the labour force. Despite increases in life expectancy and changing work environments, participants noted there is still a strong societal expectation that workers will retire by age 65. Older workers must constantly endure comments and questions about retirement from employers, managers, and co-workers, which may cause them to question their capabilities or pressure them to retire. Participants noted employers and co-workers also may exert pressure on older workers to retire by accusing them of taking away job opportunities from younger workers. Furthermore, the idea that older adults should be engaging in unpaid labour during retirement (for example, childcare, volunteering, caregiving) rather than participating in the labour force is a common notion that is promoted within society. Participants acknowledged that many older adults find engaging in these activities rewarding; however, such expectations can be harmful for the older adults who want to, or, out of economic necessity, need to work.

Policies and practices that discriminate against older workers

Participants identified a variety of employment policies and practices that appeared to discriminate against older workers. First, participants highlighted that employers often fail to consider the needs of older workers and as a result do not offer accommodations that will help keep older workers in the workforce. There is a lack of flexible work options available for older adults who, for health, disability, or caregiving reasons, may require accommodations. Some participants also pointed out that more can be done to adapt the workplace environment to meet the needs of older workers (for example, larger keyboards, adaptive devices, ergonomic chairs, louder computer or speaker volume for hearing impaired). Second, concerns were expressed by participants about pension and health insurance policies that discriminate against older workers. For example, it was noted that after age 70 contributions to the CPP are stopped and employers also usually no longer provide extended medical benefits. Third, it was noted that in some occupations, older workers are commonly forced to retire or are laid off by employers when they have reached a certain age. Fourth, employers may exclude older adults from training and advancement opportunities. Fifth, it was observed that for older job seekers, there are fewer skills training and job search programs than for other age groups.

Employment within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic

The most prominent point of discussion regarding the COVID-19 pandemic and employment was the transition to remote working that occurred in many workplaces. While participants emphasized that many older workers are proficient with technology and were able to effectively transition to remote working, it was acknowledged that some older workers struggled significantly with this transition due to being less familiar with computers and the digital environment. This digital divide was a challenge for older workers even before the pandemic; however, the pandemic significantly accelerated the reliance on digital technologies within the workplace. Participants highlighted the institutional ageism that occurred as a result, with little consideration provided to the needs of older workers and a lack of support and training opportunities from employers for older workers. Several participants commented that these workplace changes caused some older adults to accelerate their retirement plans. Furthermore, it was also stated by some participants that the remote working challenges encountered by older workers and stereotypical views about their abilities to use technology led to older workers being pressured to retire or chosen for layoffs.

A second point of discussion among participants was how ageism influenced perceptions of COVID-19 risk in the workplace and policies to mitigate these risks. While COVID-19 is a serious workplace health and safety concern, the blanket classification of all older workers as “high risk” by some employers was a concern. Participants noted that some employers adopted paternalistic approaches towards older workers, for example requesting them to work from home or laying them off to “protect” them. On the other hand, it was also noted that failures by employers to adequately create a safe working environment and mitigate COVID-19 related risks has prevented some older workers from returning to the workplace.

A final point of discussion was that the pandemic did have some positive impacts on employment opportunities for older workers. The option to work remotely has opened up new job opportunities for older workers who desire flexible working arrangements. Several participants also observed there has been an increased demand for labour in some sectors resulting in some employers becoming more willing to hire older workers.

Questionnaire feedback

Additional feedback on ageism and employment was collected through the ageism questionnaire. In the questionnaire, respondents were asked “What do you believe are the most serious ageism issues related to employment?” and were able to select up to 3 options from a list. The issues that were identified as the most significant concerns were:

- discrimination against older jobseekers in hiring processes; and

- older workers being fired, laid off, or forced to retire

Refer to Table 7 for full results.

| Ageism and employment concerns | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Discrimination against older jobseekers in hiring processes | 1,446 | 49.5 |

| Older workers being fired, laid off, or forced to retire | 1,116 | 38.2 |

| Ageist attitudes or beliefs about older workers held by employers or managers | 836 | 28.6 |

| Older workers being disrespected or excluded in the workplace | 804 | 27.5 |

| Societal beliefs that older workers take away jobs or promotion opportunities from younger workers | 724 | 24.8 |

| Societal beliefs that older workers should retire at age 65 | 664 | 22.7 |

| Ageist attitudes or beliefs about older workers held by co-workers | 594 | 20.3 |

| Company policies or practices that discriminate against older workers | 464 | 15.9 |

| Ageist attitudes or beliefs about older workers held by self | 145 | 5.0 |

| Other | 29 | 1.0 |

| I don’t believe there are any ageism issues related to employment | 154 | 5.3 |

| Prefer not to answer/Unsure | 188 | 6.4 |

- Notes: % shows the percentage of respondents out of 2,920 who selected the response. Respondents were able to select up to 3 responses, therefore the percentages do not add up to 100%.

A total of 769 comments and stories were also received about ageism and employment via the questionnaire (n=755) and the Share Your Story platform/email (n=14). The most prominent themes identified from the comments and stories were:

- employers not wanting to hire older workers (n=182)

- ageist behaviours and attitudes in the workplace (n=158)

- older workers being fired, laid off, or forced to retire (n=148)

- being pressured to retire (n=108)

These 4 themes also featured prominently in the roundtable and stakeholder-led discussions as described in section 5.2. A short summary of each theme and sample of comments and stories relating to the theme is provided below. An overarching observation across the themes was the intersections between ageism and sexism, with older women particularly likely to experience discrimination in the workplace. Additional themes that emerged from the comments and stories included: the lack of training and advancement opportunities for older workers (n=42); discriminatory policies and practices that deter older workers from participating in the labour force (for example, pension policies, employer health insurance policies) (n=40); the lack of accommodations and flexible work opportunities (n=35); and societal perceptions that older workers are taking jobs away from younger people (n=34).

Employers not wanting to hire older workers

The most common theme in stories and comments was employers not wanting to hire older workers. Many examples were provided of perceived age-based discrimination in hiring processes (for example, employers losing interest in an applicant after they met them in-person, applicant being told off-the-record the employer wanted to hire a younger person). Some respondents reported altering their resume (for example, removing dates, shortening work experience) or their appearance (for example, dying their hair) in an attempt to avoid age-based discrimination in hiring processes.

At some point, I stopped putting dates on my résumé, because I would simply not be called for an interview. Once I stopped putting dates, the interest in my application increased. So I just put 2 and 2 together and came up with ageism.

During the pandemic I was between jobs and I applied for dozens with no success. The response most times was I was overqualified or questioning why would I still want to work. Head hunters told me I was exactly what the client needed to turn the organization around but when I got to the first interview, I could see that I wasn't going to get a second.

Despite extensive experience and stellar credentials and so many vacancies, I had difficulty landing a full-time job and had to take one eventually that was at half the compensation of previous jobs. I was told it was due to my shorter shelf life (I am paraphrasing, but that was the intent of the message).

I was job hunting and emailed an application to a company. I had every qualification and got an invite to interview within hours with many positive remarks about my resume. I got to the interview and the person appeared surprised when she saw me. After a short interview I was told I was not what they were looking for. Everything was fine until she saw me, an older woman, sitting in front of her.

I have seen employer looking at resumes and calculating the approximate age of the applicant and putting resume in the not to interview file.

Older workers being fired, laid off, or forced to retire

Respondents provided many examples of older workers being fired, laid off, or forced into early retirement. In addition to examples of personal experiences and the experiences of friends, family, and co-workers, the specific case of CTV news ending Lisa LaFlamme’s contract was mentioned by multiple respondents.Footnote i Common reasons given for older adults being forced out of their employment included employers wanting to hire younger workers at lower salaries, employers having stereotypical views about the capabilities of older workers, and employers feeling that older workers no longer “fit” with the company culture or image. It was observed by multiple respondents that when layoffs occur at a company, the majority of employees laid off are older workers.

My co-worker and I were let go because we were 'too old' to represent the company. This was not said to us, but reported by another from a board meeting.

I was laid off in July 2021 after the store where I worked closed. Everyone was offered a job at a different store except for me. I was the store manager and the company had several ads for store managers and all other positions in the area. I asked my manager if I could stay on as Assistant Manager or just a team member instead of being laid off but she said no, I would have to re-apply. After getting one month's severance, I knew I didn't have a chance of ever working for that company again.

Our company created a false financial crisis, saying that our division was losing money, when in fact we were keeping some of the other divisions afloat financially. Five of us over the age of 55 were fired without cause in the course of a single morning. No younger people lost their jobs then or later.

My mother was let go from her job at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Younger, newer staff (less than 1 month experience) were kept on for their 'longevity in the organization', as stated after the fact to another employee.

Ageist behaviours and attitudes in the workplace

Respondents provided many examples of the ageist behaviours and attitudes of co-workers and managers that make older workers feel unwelcome in the workplace. Respondents reported older workers are commonly subjected to ageist attitudes and disrespect by co-workers and managers (for example, name calling, jokes about older workers, assumptions about abilities and competence). Respondents also reported feeling ignored or excluded by their colleagues, both in the workplace during projects and meetings, as well as socially outside of the workplace. Some respondents reported the knowledge and experience of older workers is overlooked or viewed as out-of-date.

As a 63-year-old, white-haired female person, I have found that managers often treat me as if I am incompetent when dealing with technology. They seem to have this preconceived notion that older people don't understand technology.

What I see often occur in workplaces I've been is a lack of respect for older employees (particularly those not in positions of power). These folks are often treated as disposable and given less air time in meetings, fewer responsibilities, and there is less effort on the part of co-workers to include them.

I have heard colleagues in their 30s comment about 'older' staff people being resistant to change or 'not understanding' how straightforward an issue is when the colleagues they are referring to are often more experienced and can see aspects of an issue or additional factors that might need to be considered before implementing change. They are not resisting change, only bringing experience to the discussion to help make the change successful.

I obtained new employment at age 60 and maintained that employment until 70. I had to work very hard to ensure that younger workers did not exclude me in group discussions/social interaction, and to acknowledge that I had assets (skills, experience) that positively contributed to the workplace. A general attitude that as an older person I could not keep up with current practices and would not be open to differing perspectives.

My colleagues make jokes about old women and then tell me how extraordinary I am because I am still able to work. I have one colleague who tells me that I should be sitting at home because that's what her grandmother does.

Being pressured to retire

Over one hundred comments and stories related specifically to the theme of being pressured to retire. Respondents reported co-workers, managers, or human resource professionals constantly asking them when they would retire or suggesting they should retire. In some examples, respondents reported being targeted with mean-spirited comments or it being implied they were taking away opportunities from their younger colleagues. Respondents also provided examples of having their hours reduced, being given unfavourable or difficult assignments, or being bullied or harassed in attempts to force them to retire. In some cases, respondents reported deciding to retire earlier than they would have preferred, due to the pressures being put on them to retire.

Being asked why I don’t retire (on a weekly basis). I’m 56 but have worked for 30 years. I’m eligible to retire but I’m not ready yet. I still feel I have a lot to offer.

The HR department coming to you as soon as you turn 60 and asking when you plan on retiring rather than asking if you enjoy your job and plan on continuing to work because they are glad you are working for them!

A few years ago, my employer made an offer of early retirement. Some employees could not avail themselves of it (financial, social or other reasons); a member of senior management chided them, in front of everyone, for not quitting.

Managers at [my company] would put additional pressures and workloads on older workers trying to force them to quit or become so ill they would miss work and then be pressured to quit. Often managers would get a bonus for having encouraged older workers to take an early retirement package to the point where such a person would buckle under the pressure and quit, often having to go to much lower paying jobs.

Supervisor who asks the question almost every week and sometimes even every day: "When do you plan to retire? You should think about it!" With a young person, the salary would be lower and the number of vacation days fewer. The experience acquired in the company and the quality of the work are not taken into account. It's the volume of work that counts even if you have to go back to do the work.

Ageism and health and health care

Introduction

There is strong evidence that ageism impacts the health of older adults. Ageism may contribute to declines in memory function, increased risk of developing dementia, and decreased life expectancy.5,6,7 Research suggests that ageism can directly affect the health of older adults through 3 main pathways: 1) psychological (for example, ageist attitudes and beliefs become a “self-fulfilling prophecy”); 2) behavioural (for example, negative stereotypes may lead older adults to believe there is no point in engaging in healthy behaviours); and 3) physiological (for example, exposure to negative stereotypes causes stress and triggers cardiovascular stress responses such as increased blood pressure and heartrate).8 Ageism within the health care system may also lead to poor quality health care. For example, health care providers may assume an older adult’s symptoms are a normal part of aging rather than a sign of a health condition.9 Researchers in the United States have estimated that ageism costs their health care system $63 billion annually.10

Roundtable and stakeholder-led consultation feedback

Ageist attitudes and practices within health care

The most frequently discussed concern about health care was how ageist attitudes can impact health care practices and how health care providers treat older adults. Older adult patients being ignored, not listened to, infantilized or spoken to as if they were a child (elderspeak), patronized, or treated paternalistically were common concerns. Multiple participants provided examples of older adults attending medical appointments and the health care provider speaking to their children and ignoring the older adult. Participants also expressed concern about the paternalistic way long-term care residents are treated. For example, the strict visitor restrictions that were put in place to protect long-term care residents during the COVID-19 pandemic were noted to have been implemented without input from residents.

Health care providers holding stereotypical beliefs about older adults (for example, all older adults are frail and dependant) was also a significant concern, with changes in physical and cognitive health commonly assumed to be a natural part of aging. Many participants commented that health care providers do not take the health concerns of older adults seriously and dismiss these concerns as being simply “due to age.” Several participants commented that the limited training given to health care providers on the needs of older patients contributes to these problems. For example, geriatrics training for physicians is often only 1 to 2 weeks long and occurs in a long-term care facility. Some participants also commented that family physicians may be unwilling to take on older adult patients due to assumptions they are in poor health and will take up too much time.

Participants also provided examples of older adults being denied care or provided with different treatments or recommendations based on their age. Older adults were commonly viewed as being lower priority cases for the health care system, particularly when trying to access hospital care. Examples were provided of older adults receiving surgeries or treatments only after convincing their doctors they were fit and/or productive members of society. During the COVID-19 pandemic, several participants commented that discrimination against older adults intensified with triage policies discriminating against people based on their age, and long-term care facilities treated as a lower priority health care setting for resources and personal protective equipment.

In their comments, participants also highlighted how ageist attitudes can intersect with racism, sexism, homophobia, ableism, and other forms of prejudice and discrimination to impact how older adults are treated by health care providers. Previous experiences of discrimination or trauma can also deter older adults from accessing needed medical care. In feedback from First Nations and Métis participants it was stated that health care settings may be traumatic for elders who are survivors of residential schools or the Sixties Scoop.

Systemic barriers to accessing health care

In the roundtable and stakeholder-led consultations, participants discussed a variety of systemic barriers that can prevent older adults from accessing health care services. The most commonly identified were: 1) transportation, 2) telehealth, and 3) language and communication barriers. Participants viewed these barriers as examples of systemic ageism, as health care systems have failed to take into account the needs of older adults and design their services to accommodate them.

Participants identified transportation as a major barrier to accessing health care. While the majority of older adults drive cars, health conditions and changes in physical and cognitive abilities can lead older adults to restrict their driving habits. Participants commented that older adults, and particularly those at more advanced ages, may be uncomfortable driving at night or to unfamiliar places. Some older adults may have decided or been required to stop driving. As a result, older adults may rely on public or accessible transportation, volunteer driver programs, or friends and family to travel to appointments. Transportation was particularly a concern for rural, remote, and Indigenous communities, where there often are limited or no public and accessible transportation options and older adults must travel long distances to access health care services.

Box 1: Travelling to access medical care: feedback from a stakeholder-led consultation

Elders noted that within towns and cities, specifically in (the north of the province), it has been difficult to obtain a long-standing family doctor. Even when a doctor is found, appointments are few and far between, while transportation to and from appointments is another barrier to accessing health care. Specifically, in the north or within smaller communities, Elders must travel a great distance to obtain regular and routine health care, with long waits, and any additional testing or treatment being even further, most often needing overnight accommodation. This is especially difficult to obtain for Elders who may not have access to transportation at any point in time, while a low-income creates an even larger gap, leaving Elders at the mercy of community programming or family members to care for them, taking days off work, investing monies into gas and accommodations rather than securing housing, food, and other necessities.

Participants observed that since the COVID-19 pandemic began, there has been a significant increase in the use of telephone and virtual appointments. While telephone or virtual appointments can address the inconveniences caused by travel, they also can be a barrier to access for older adults who are unfamiliar with/lack access to digital technologies or who live in communities that do not have internet infrastructure or good cellphone reception.

Finally, some participants believed expectations that older adults accessing health care services will have a high level of fluency in English or French, and the lack of translation and interpretation services available to address language and communication barriers, are examples of systemic ageism. Participants in the consultations noted 2 main ways that age amplifies language and communication barriers: 1) Due to cognitive changes that can occur later in life, it may be more difficult to learn a new language and fluency in secondary languages can decline or be lost with age; and 2) Older adults may have had fewer educational opportunities compared to younger generations, and as a result may not have had an opportunity or may find it more difficult to learn English or French. Participants identified immigrants, Indigenous elders, older adults who are deaf or hard of hearing, and members of French or English language minority communities as populations particularly likely to be impacted by language or communication barriers. Language barriers were particularly observed to be a problem for older adults residing in long-term care facilities who may be unable to communicate with the people who are providing them with daily care.

Systemic neglect of long-term care and home care