Older workers: Exploring and addressing the stereotypes

On this page

- Participating governments

- Acknowledgements

- Executive summary

- 1. Why it’s important to address stereotypes about older workers

- 2. What was done to explore stereotypes about older workers

- 3. Stereotypes about older workers

- 4. Potential action addressing stereotypes about older workers

- 5. Final thoughts on stereotypes about older workers

- 6. References

- Appendix A – Approach

- Appendix B – Selected negative stereotypes, available evidence, and potential actions

- Appendix C – Examples of promising initiatives

Alternate formats

Older workers: Exploring and addressing the stereotypes[PDF - 2.18MB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

Participating governments

- Government of Ontario

- Government of Quebec*

- Government of Nova Scotia

- Government of New Brunswick

- Government of Manitoba

- Government of British Columbia

- Government of Prince Edward Island

- Government of Saskatchewan

- Government of Alberta

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Government of Northwest Territories

- Government of Yukon

- Government of Nunavut

- Government of Canada

*Québec contributes to the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Seniors Forum by sharing expertise, information and best practices. However, it does not subscribe to, or take part in, integrated federal, provincial, and territorial approaches to seniors. The Government of Québec intends to fully assume its responsibilities for seniors in Québec.

Acknowledgements

Prepared by Pamela Fancey, Lucy Knight, Janice Keefe and Safura Syed of the Nova Scotia Centre on Aging, Mount Saint Vincent University, for the Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors. The views expressed in this report may not reflect the official position of a particular jurisdiction.

Executive summary

Background

Canada has more and more older workers in its labour force in recent years. All levels of government encourage the engagement of older workers who offer value to our economy and the broader society. Yet negative beliefs and attitudes about older workers, in the form of stereotypes, persist and may impact their labour force participation. Negative stereotypes can lead to discriminatory practice from hiring through to workforce exit and can contribute to older workers’ lower feelings of self-worth.

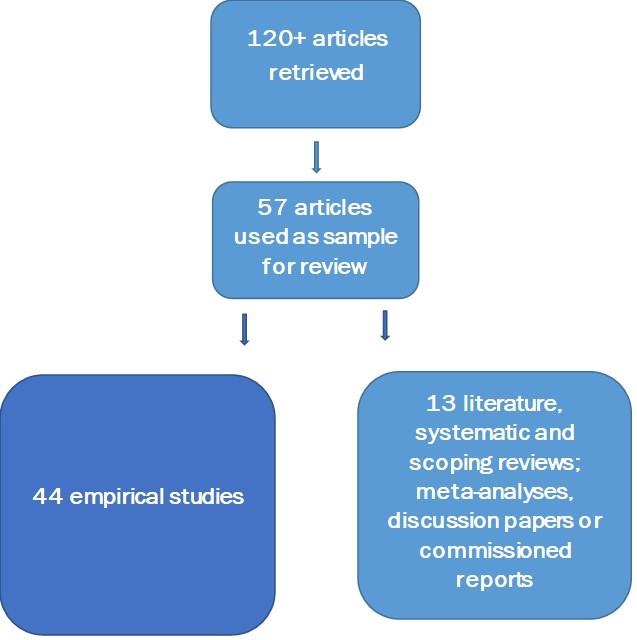

In 2019, the Forum of Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Ministers Responsible for Seniors commissioned a review of the literature to examine current knowledge on attitudes and beliefs about older workers and to uncover initiatives to address stereotypes. Close to 60 English- and French-language articles from academic and grey literature published between 2009 and 2019 were reviewed. The research reveals there are varying definitions of older workers, and also indicates a range of approaches for measuring the concepts contributing to stereotypes. Studies are international in scope and include a mix of industries and occupation groups.

The evidence compiled provides insight into common stereotypes about older workers, stereotype holders, and factors that perpetuate the stereotypes. The work builds upon, and complements, the Forum’s initiatives on the labour force participation of older workers and ageism Footnote 1,Footnote 2, and will help to inform policy discussions and program development. It should be noted that the information compiled for this report was obtained prior to COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. The potential impact of negative stereotypes on the labour force participation of older workers during this time has not been considered.

Exploring the stereotypes

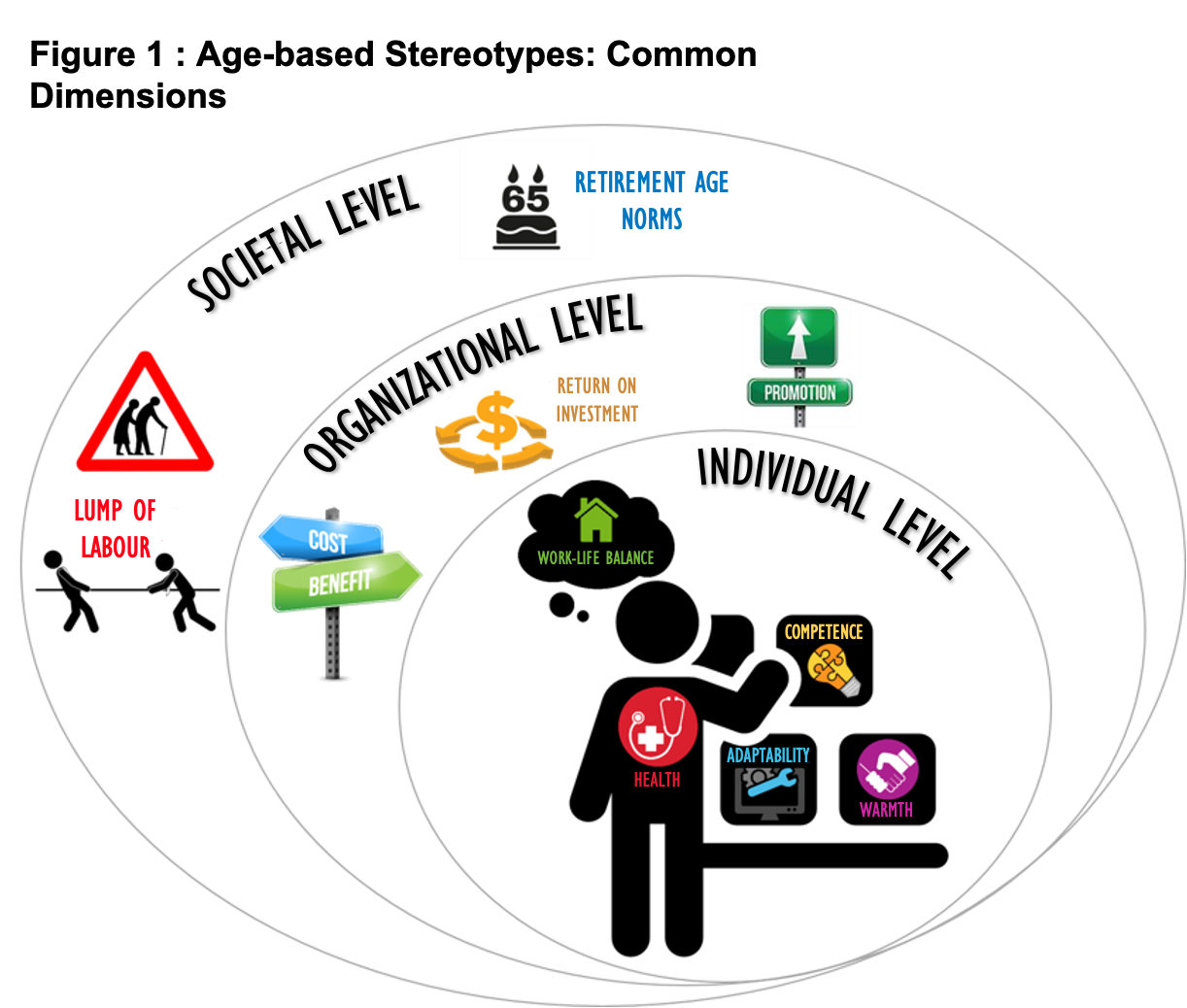

Age-based stereotyping in the workplace is complex. A framework helps to visualize and understand stereotypes at 3 different levels: individual, organizational and societal. Individual level stereotypes about older workers’ competence, adaptability (most often associated with technology and learning) and warmth (meaning sincere, kind, or trustworthy) are most common. Competence describes a variety of traits, including being capable, skillful and intelligent. The variety of definitions (including what is meant by ‘competence’), lack of definition, and overlap with other traits makes these stereotypes a challenge to disentangle.

Often, the image of an older worker combines both positive and negative stereotypes. For example, older workers have been described both as “warm” but resistant to change or lacking adaptability. Individual level stereotypes also include assumptions about older workers’ health and work-life balance. Perceptions at the organization level suggest that older workers are costly to employ and train, and are unfit for promotion. In society, broad assumptions exist that more older workers and delayed retirement will mean fewer opportunities for younger workers to enter the workforce. Retirement age norms may also contribute to perceptions that adults should exit the labour force at a certain age.

Most commonly examined in research on stereotyping are employers’,- managers’, and workers’ (not always older) perspectives. Managers across sectors and industries hold stereotypes about older workers that may contribute to discrimination; however, managers’ own ages may have a mediating effect. Given the array of generations participating in work, these dynamics are meaningful. For older workers, experiencing and perceiving stereotyping puts them at risk of internalizing these beliefs and holding negative attitudes towards work, with potentially negative consequences for their labour force participation and mental health. There is limited evidence exploring older worker stereotypes and gender. However, perception of being stereotyped differs between men and women, with women perceiving that they are being stereotyped more often than men. Evidence shows that certain industries, notably finance, insurance, retail and information technology, may hold more negative age-based stereotypes.

Most research on stereotypes is undertaken to determine whether or not older worker stereotypes are held. Much less attention is given to whether these stereotypes are rooted in fact. However, most negative stereotypes appear to attribute characteristics of the minority of older persons who have health and cognitive challenges to all older workers, and to ageist views in general. These do not reflect actual older Canadians in today’s labour force.

Addressing the stereotypes

There are initiatives aimed at increasing older adults’ labour force participation, but few if any focus specifically on addressing stereotypes about older workers. Existing research recommends highlighting positive characteristics of older adults, addressing discrimination in the workplace through targeting practices from hiring through to exit, and using awareness-raising initiatives to discredit stereotypes.

Resources such as tool kits and guides for employers are emerging that foster age-friendly workplaces as well as recruiting and retaining older workers. Efforts by employers should include creating positive intergenerational contact and a culture of inclusion. Awareness initiatives are needed that target older adults, employers and employees, and the general public. Key messages to include are: challenging notions of retirement age norms, recognizing the value and contribution of older adults to the economy and society, examining negative stereotype implications for health, and recognizing the diversity and experiences of older age cohorts today may be different than previous cohorts.

Final thoughts

Age-based stereotyping in the workplace is complex; positive stereotypes exist alongside negative ones. While some research points to factors like age, job status, and societal norms as contributing to stereotypes, there is a lack of empirical evidence from Canada to corroborate these claims.

The data on stereotyping are largely based on studies 10 to 20 years old, so caution should be exercised in relying on these sources, particularly with regard to stereotypes and evidence about older workers and technology. The perspectives of employers-managers and older workers are most commonly reported and there is some evidence to suggest that holding negative age-based stereotypes lessens as one becomes older.

The intersection of age-based stereotypes with other stereotypes, such as those found in race and gender, need more investigation. Information on how identity (including gender), diversity, and living environment mediate negative perceptions of older adults would assist initiatives targeting ageism. The changing labour market and what it may mean for understanding older worker stereotypes is also worthy of consideration.

1. Why it’s important to address stereotypes about older workers

1.1 Introduction

During the last 2 decades Canada has seen greater numbers of older workers in its labour force. All levels of government encourage this cohort’s inclusion and recognize its important economic and social contributions. Yet widespread ageist views may be responsible for persistent negative beliefs and attitudes about older workers and their role in the workforce. The Federal, Provincial and Territorial Seniors Forum has identified ageism as a barrier to older workers’ labour force participation (FPT Ministers Responsible for Seniors, 2018). Internationally, it has been recognized that ageist attitudes and behaviours stand in the way of older adults working longer (OECD, 2019). One way that ageism may be expressed is through stereotypes, which can result in discrimination against older workers. Examining the attitudes and stereotypes of older workers is a priority of the Forum.

Research published in the last decade examines beliefs, myths, norms, attitudes, and assumptions that can lead to stereotypical views about older workers and their personality traits, preferences, and abilities, or about how older workers’ workforce participation is affected by age-related challenges (such as health issues). Some assume that older workers cost more to employ, or that their employment reduces the number of jobs available to younger workers.

This section of the report, Section 3, looks at ageism and the labour force to examine older worker stereotypes held by employers, older workers, older adults and the general public. Section 4 summarizes the literature search strategy and analyzes relevant research on older worker stereotypes (see Appendix A for search description and parameters). Section 5 uses language and definitions from the research to identify, understand and interpret common stereotypes (see Appendix B for a selection of stereotypes, available evidence and potential actions), as well as insights and knowledge gaps. Section 6 considers how to address stereotypes through potential responses, strategies and initiatives targeted at specific public and private audiences (for example, older workers, organizations and employers, and the general public). Despite general awareness-raising activities, there appears to be few concrete actions that address ageist stereotypes. Examples and links to promising initiatives are included in Appendix C.

It should be noted that the information compiled for this report was obtained prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. This work does not consider the influence of negative stereotypes on the labour force participation of older workers during this time.

1.2 Society and the labour force

Ageism is the stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination against people on the basis of their age (WHO, 2018). Although all age groups may face negative age-based perceptions, ageism towards older adults has been described as “most tolerated form of social prejudice” (Revera Inc. & IFA, 2012, p. 2). Ageism is rooted in how we perceive age and aging. Evidence suggests that across cultures and continents, young adults (those most often identified as having ageist attitudes) hold remarkably similar perceptions of aging; that is, there is an increase in wisdom but a decline in “the ability to perform everyday tasks” (Löckenhoff et al., 2009, p. 12). Research on labour force ageism is growing as developed countries’ workforces age (Nelson, 2016). Ageism has been identified as 1 of 5 challengesFootnote 3, facing older Canadians in the labour force (FPT Ministers Responsible for Seniors, 2018).

Ageism may occur as an age-based stereotype: “a simplified, undifferentiated portrayal of an age group that is often erroneous, unrepresentative of reality, and resistant to modification" (Dordoni & Argentero, 2015 citing Schulz et al., 2006, p.43). Used as a mechanism to judge others quickly (Ng & Feldman, 2012), stereotypes arise from “societal culture” and our experiences with “members of stereotyped groups” (Marcus et al., 2016, p. 990). Entrenched stereotypes about older workers (van Dalen et al., 2010) are possibly due to “implicit attitudes…assumed to have developed over an individual’s lifetime” (Malinen & Johnston, 2013, p. 459). Paternalistic attitudes are often reflected in stereotypes about older adults being “warm, good-natured, sincere and happy”, but barely competent (Marcus & Fritzsche, 2016, p. 222). Since society holds negative perceptions of age and aging (Revera Inc. & IFA, 2012), negative attitudes towards older workers may be rooted in a broader context associating age with decline.

Older worker stereotypes may contribute to age discrimination at all employment stages, from recruitment to workforce exit (Solem, 2016). Age-related stereotypes may impact older workers when they attempt to (re)engage in the labour force (Gahan et al., 2017; Nova Scotia Centre on Aging, 2018). Discrimination can manifest in older workers being not considered for hiring, training or promotions or encouraged towards early retirement. Evidence shows that older workers who perceive or experience age-based discrimination or negative stereotyping may show less commitment in the workplace (James et al., 2013) and believe less in their own leadership potential (Tresh et al., 2019). These negative perceptions affect whether or not older workers remain in their jobs (von Hippel et al., 2013).

Of course, negative stereotypes about older workers are not necessarily true. Assumptions about older workers’ cognitive decline, for example, may be rooted in studies involving participants who do not reflect the older working population (Ng & Feldman, 2012). Similarly, stereotypes about older workers’ struggles to adapt to technology may not represent those aged 50 to 65, who are generally familiar with workplace technology (Poulston & Jenkins, 2013) after years working with and adapting to new technologies. Stereotypes rely on sweeping generalizations that ignore the diversity of the current labour force and the older population.

It should be noted that younger workers may also face negative age stereotypes. Many studies examined for this report compare younger and older workers’ characteristics or stereotypes. Interestingly, a large German study suggests that younger workers are actually more resistant to change (Kunze et al., 2013), despite this stereotype being associated with older workers.

2. What was done to explore stereotypes about older workers

2.1 Approach

Literature published in English and French between January 2009 and October 2019 was identified through database searches (for example, Academic Search Premier, Business Source Premier), targeted web searches (for example, Google Scholar, government, organizations), reference list reviews and other sources. Searches yielded over 120 relevant publications. Additional searching was carried out to enhance stereotype context and conceptualization, and to identify initiatives. The primary body of literature consists of articles determined by their abstracts to focus most closely on stereotypes, attitudes, perceptions or negative images of older workers; these were reviewed in full and annotated (n= 57).

The sample of 57 articles is international in scope and contains primarily empirical research studies published in peer-reviewed journals. Studies from Europe are most common, and while there are some North American studies, Canadian evidence is limited. The studies included reflect a variety of cultural backgrounds which may potentially influence their findings regarding attitudes towards aging. Employer and employee perspectives are most common. Studies draw from workers and employers in various industries, occasionally occupation groups (for example, taxi drivers) or traditional “collars” (for example, blue collar, white collar), or levels of authority (for example, persons with hiring or decision making authority). Several studies describe their samples as a mixture of industries and sectors, or do not include this information. Studies on recently retired older workers are nearly absent in the sample. Sample sizes of the studies range from close to 100 to over 1,000 participants.

A full description of the methodology is presented in Appendix A.

2.2 Who is an older worker

This research explores stereotypes about older workers. Drawing upon the existing body of research, an older worker is understood as someone who wants to remain engaged in the labour force, wants to join or rejoin the workforce, may have recently left the labour force (due to early retirement, restructuring, inability to find work, etc.) and is described in the literature as “older.”

The age of workers identified as older varies internationally. In Canada, an older worker is frequently defined as 55 years of age or more (FPT Ministers Responsible for Seniors, 2019). However, the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) defines an older worker as aged 50 and older (OECD, 2006), which is the common international literature definition.

Research shows older workers as being 40 or older, while other research indicates older workers as 50 or older. Definitions can be influenced by different factors, such as a national mandatory retirement age and anti-age discrimination legislation (Dordoni & Argentero, 2015). Other definitions consider the active workforce’s age range (16 to 65 years old, according to the International Labour Organization, 2005) to designate age 40 as the distinction point between younger and older workers, noting that this age traditionally marks a transition in working life (Ng & Feldman, 2008). As well, different academic disciplines have different conceptions of age (Ilmarinen, 2001; Ng & Feldman, 2008). For these reasons, identifying older workers by age risks excluding relevant findings from studies using a younger definition (or no definition) of an older worker.

In addition to differences in definitions, labelling older workers by chronological age can perpetuate organizational ageist attitudes and age discrimination (Sterns & Miklos, 1995). Age definitions may need to be rethought as more older workers are employed beyond traditional retirement ages, and as younger adults extend their studies and potentially delay career trajectories. Other researchers suggest that organizations need to move away from singling out older workers and adopt workplace practices that are more inclusive of all ages (Desmette & Gaillard, 2008; Fiore et al., 2012).

3. Stereotypes about older workers

3.1 Overview

Age-based stereotyping in the workplace is complex. It is frequently multi-dimensional–positive stereotypes exist alongside negative ones (Bal et al., 2011), and contrasts views about younger workers and older workers. For example, older workers are often seen as warmer (meaning sincere, kind and trustworthy) but less competent (meaning capable, skillful and intelligent) (Krings et al., 2011). However, researchers do not use definitions and measurement instruments that align with labour market research, hampering interpretation and comparability of available findings.

Some authors acknowledge and explore positive images of older workers. In a scoping review of 43 research articles on ageism published between 2006 and 2015, Harris and colleagues (2017) note that reliability and commitment or loyalty are the most common positive stereotypes of older workers. The authors also found that older workers are seen as warm, experienced and knowledgeable, with a strong work ethic, and more skilled socially and interpersonally compared to younger workers, according to employees of all ages, managers and human resource personnel.

Positive images of older workers are more prevalent amongst managers who are themselves older (van Dalen & Henkens, 2017). A 2017 study of 905 managers found an association between managers’ own desires to continue working past age 66 and their perceptions of older workers (Nilsson, 2018). Those not planning to retire were more committed to retaining older workers and held positive attitudes about older workers’ carefulness and valuable skills and experience in the workplace, particularly through mentorship. Managers who intended to retire at age 66 held more negative stereotypical views about older workers. In comparing older and younger workers, older European managers tended to rate older workers more highly than younger workers (van Dalen et al., 2009).

Discrimination against older workers exists in multiple countries (James et al., 2013; O’Loughlin et al., 2017). In Canada, survey respondents identified employers as a source of age discrimination (Revera Inc. & IFA, 2012) throughout selection, hiring, employment, or exit stages. Unfortunately, the reasons for this discrimination are not always examined. Focus groups with older workers in Nova Scotia found that job-seeking older adults perceive discriminatory practices during candidate selection, and in some cases, experience discriminatory behavior (such as being asked to state their age during an interview) (Nova Scotia Centre on Aging, 2018).

At least 2 empirical studies using hypothetical job candidates (Abrams et al., 2016; Krings et al., 2011) support the claim that job-seeking older adults are more negatively perceived than younger candidates. While these studies’ participants include college students as well as workers of all ages, their results indicate an inherent age-bias that may impact older adults attempting to join or rejoin the workforce. A similar conclusion is drawn from a survey of 102 human resource personnel in the United States, who were less likely to want to hire the older candidate when asked about the likelihood of hiring 1 of 3 differently-aged candidates (Fasbender & Wang, 2017).

Age-based discrimination in the labour force is both implicit and explicit. An Australian report shows how euphemisms may mask discrimination. Drawing on actual accounts provided to National Seniors Australia, the study emphasizes comments such as “We didn’t think you’d fit in”, and “We want someone with a high energy level” (Australia Health and Ageing, 2011, p. 13). A small qualitative UK study provides a clear example of age-based discrimination: an unemployed woman (age 51) who was turned down for a job asked for feedback and was told, “Well, you interviewed extremely well, but we wanted someone younger” (Moore, 2009, p. 660). Strikingly, data from a Polish study found that where an upper limit for candidate age preference existed amongst managers, age 45 was the average maximum age (Turek & Henkens, 2019). This shows that age-based discrimination persists even in countries such as Poland, where national employment law prohibits age-related discrimination (agediscrimination.info, n.d.).

Studies show that specific negative stereotypes and attitudes contribute to discriminatory behavior and ageism more broadly. Some researchers suggest workplaces counter negative stereotyping by highlighting positive stereotypes about older workers (von Hippel et al., 2013). In fact, one study found older workers to be more interested in learning and development when exposed to positive stereotypes about motivation and ability to work, learn and develop (Gaillard & Desmette, 2010). However, this finding is from a smaller study of white-collar employees in one country, and may not represent other employee groups.

3.2 Common stereotypes

A 3-part framework, consisting of individual, organizational and societal levels, helps to envision and understand stereotypes about older workers (see Figure 1). The individual level draws on research that identifies 3 common stereotype areas specific to older workers: competence, adaptability and warmth (Marcus et al., 2016). Based on additional literature, stereotypes about older workers’ health and work-life balance are also added to the individual level. Individual level stereotypes in these areas may contribute to stereotypes about older workers’ productivity and performance. For example, Dutch employers and employees in one study identified older workers’ productivity as lower than younger workers (van Dalen et al., 2010). However, the authors’ definition included 11 different traits and skills (including mental capacity and willingness to learn), many of which can be considered aspects of the individual level stereotype areas in Figure 1. The organizational level concerns stereotypes about older workers’ value, cost and worth to an organization. The societal level concerns stereotypes linked to labour force trends and considerations, as well as the norm that older adults should exit the workforce by age 65.

Figure 1 - Text version

Concentric circles representing 3 levels (individual, organizational and societal) with symbols.

- Individual level: health, adaptability, warmth, competence and work-life balance

- Organizational level: costs and benefits, return on investment and promotion

- Societal level: lump of labour and the retirement age norms

Many of these stereotypes are inter-related and speak to more than one level. For example, managers who believe that older workers are less competent in relation to innovation and cognitive ability (individual level) may fashion this into an attitude that older workers are not fit for promotion (organizational level) (Guillen & Kunze, 2019). In another instance, cognitive decline may apply both to competence and health individual stereotype areas. The framework is useful as an organizing tool to help address the challenges of defining and grouping stereotypes.

3.2.1 Individual level

3.2.1.1 Competence

Many studies identify competence as a common negative stereotype about older workers. Evidence suggests that stereotypes of older workers being less competent than younger workers are held by young adults (Krings et al., 2011), human resources professionals (Krings et al., 2011), and other workers (Shiu et al., 2015, workers with a mean age of 35), including younger workers (Kadefors & Hanse, 2012). Multiple definitions of “competence” are used in the literature, including capable, skillful and intelligent (Krings et al., 2011). It is often examined in conjunction with “warmth”, as these are the 2 core dimensions of social judgement and stereotype content theories used by some researchers (Krings et al., 2011; Marcus et al., 2016). Perceptions of productive skills or attributes may underlie some competence stereotypes. In the literature, authors have conceptualized skills requiring “physical and mental capacity” (Karapinska et al., 2013, p. 890) as markers of productivity. In one study, these productive skills are described as “stress resistance, creativity, flexibility, physical stamina, new tech skills and willingness to train” (van Dalen & Henkens, 2017, p. 9). Competence stereotypes are a challenge to untangle because studies’ use varied definitions and stereotypes frequently overlap.

Some studies examine the potential consequences of competence stereotypes. Being seen as less competent has implications for older job candidates competing with younger candidates, even when an older candidate may simultaneously be seen as warm (Krings et al., 2011; Shiu et al., 2015). An older worker’s ability to innovate (relating to idea implementation) is a factor in project managers’ perceptions of their competence (Guillen & Kunze, 2019). A large, multi-country study in Europe found that older workers are more satisfied with their jobs when they live in a country that views older workers as competent (Shiu et al., 2015).

Assumptions of older workers’ mental capacity and intelligence may contribute to perceptions of competence. Mental capacity is identified as an aspect of productivity in some research (Lamont et al., 2015; van Dalen et al., 2010). In an empirical study comparing productivity of workers aged 35 and younger with workers aged 55 and older, authors found that older workers’ mental capacity was rated comparatively lower (van Dalen et al., 2010). Research finds some potential truth to this stereotype. One literature review notes that older workers “may have more difficulties with complex tasks that require a high level of executive functioning” and that they have “poorer recognition and recall memory” than younger workers, which results in employers trusting older workers’ memories less (Ng & Feldman, 2008, p. 395). The perception that older adults’ abilities decline with age is discussed in one study as an important determinant of negative perceptions of older workers’ development capability (Fiore et al., 2012).

In a review of research published prior to 2009, authors concluded that older workers are perceived as less intelligent than younger workers (Ng & Feldman, 2008). However, discussion about competence stereotypes notes that age is not related to curiosity or willingness to learn (Appelbaum et al., 2016). A review of studies suggests that older workers’ wisdom and expertise may compensate for potential cognitive performance decline, so that work performance is unaffected (Ng & Feldman, 2008). However, other research suggests older adults may actually underperform because they are aware of negative stereotypes about their cognitive performance and fear confirming them (Lamont et al., 2015).

3.2.1.2 Adaptability or resistance to change

Older workers lacking adaptability in the workplace is a common stereotype, perhaps grounded in societal beliefs that older workers “are harder to train, less adaptable, less flexible, and more resistant to change” (Posthuma & Campion, 2009, p. 162). For example, 55% of participants (aged 18 and older, not necessarily employed) in a large Australian study felt that workers aged 55 and older “were more likely to have difficulty adapting to change” (O'Loughlin et al., 2017, p. 99). A second study from Australia, with nurse recruiters as the participants, found that adaptability was a characteristic attributed by recruiters to younger (under age 40) rather than older (aged 55 to 70) nurses (Gringart et al., 2012).

European and New Zealand studies confirm employers’ negative stereotypes about older workers’ ability and willingness to adapt to change, including technology and training (Poulston & Jenkins, 2013; van Dalen & Henkens, 2017; van Dalen et al., 2009). For example, hotel managers in New Zealand perceived employees aged 50 and older as being slow to learn, including about technology, and uninterested in training and technology (Poulston & Jenkins, 2013). The study notes a major employment barrier arising from the stereotype of older workers’ disinterest in technology, although current older workers are generally familiar with workplace technology. A study with employers and older workers in various industries (mostly commercial services and trading) in Hong Kong also confirms employers’ negative stereotypes about older workers’ technological adaptability. The authors concluded that employers most commonly held older worker stereotypes that this cohort had “difficulty taking up new jobs” and was “slow in learning” (Cheung et al., 2011, p. 127).

Approximately 40% (United Kingdom) to 60% (Greece) of employers in a comparative 2005 study using European data believed there would be “less enthusiasm for new technology” as their employees’ average age increased (van Dalen et al., 2009, p. 20). This study found that “new technology skills” was the lowest rated characteristic attributed to older workers by employers (van Dalen et al., 2009, p. 21). As both a skill and a characteristic of older workers, “willingness to train” received a low rating from managers in the Netherlands (van Dalen & Henkens, 2017, p. 12).

A Slovenian study on employee perceptions found that older workers (aged 50 to 65) agree they are stereotyped as less adaptable and more resistant to change, compared to younger workers aged 18 to 49 (Rožman et al., 2016). A study of pharmaceutical companies in the United States found that negative perceptions of older workers’ capacity for innovation and change (measured by creativity, flexibility, motivation, willingness to learn, and innovation) lessened with respondent age (McNamara et al., 2016).

Are older workers actually resistant to change? Results are mixed. A study of nearly 3,000 German workers in various sectors (largely the service industry; average participant age of 39), found that it was actually younger workers who were more resistant to change (Kunze et al., 2013).

Stereotypes about motivation are linked to perceptions of older adults’ adaptability. A review of 318 studies found that “the only stereotype consistent with empirical evidence is that older workers are less willing to participate in training and career development activities" (Ng & Feldman, 2012, p. 821). They note that this stereotype is based on assumptions that older adults are nearing retirement, are less focused on work achievements, have “less capacity to learn new material” and “are more difficult to teach” (Ng & Feldman, 2012, p. 830). The authors concluded that age has a weak, negative relationship to career development motivation and motivation to learn (Ng & Feldman, 2012). However, these findings must be interpreted carefully to avoid perpetuating the stereotype of older workers’ resistance to training and development, since this is not a homogeneous group (Finkelstein et al., 2015).

A study of German employees aged 50 to 64 working at different levels in automotive supply, electrical industry, insurance, IT service industry, trade, and waste management breaks the stereotype of unmotivated older workers (Rabl, 2010). Results from this study indicate that these participants showed motivation to achieve (measured by responses to questions about their hope for success and fear of failure). However, the author found some evidence of employees’ fear of failure when confronted with managers’ age discrimination. The authors discuss the potential implication that older workers facing discrimination may exhibit unmotivated behavior as the stereotype becomes self-fulfilling (Rabl, 2010).

3.2.1.3 Warmth

“Warmth” appears often alongside competence in research about older worker stereotypes (Krings et al., 2011; Marcus et al., 2016). Warmth is variously defined as being “sincere, kind and trustworthy” (Krings et al., 2011, p. 188), being “tolerant” (Iweins et al., 2013), and “warm-hearted, warmer personality, likeable… [and] friendly” (Tresh et al., 2019, p. 5). Other studies refer to reliability, loyalty and commitment to an organization, social skills and management skills (Karpinska et al., 2013; van Dalen & Henkens, 2017). The descriptors “stable” and “dependable” also appear interchangeably with “reliable” in the literature. This collection of varied terms is generally thought of as interpersonal skills, personal qualities or behavior characteristics.

Research examining stereotypes in this area is focused on employers’ and managers’ perceptions. Managers and employers often see older workers as being more reliable (Bal et al., 2011; Karpinska et al., 2013; van Dalen & Henkens, 2017), more dependable (Posthuma & Campion, 2009)Footnote 4, and more committed and loyal than younger workers (Karpinska et al., 2013; Posthuma & Campion, 2009; van Dalen et al., 2009; van Dalen et al., 2010; van Dalen & Henkens, 2017). A multi-country study on European employers’ perceptions found that reliability was the most highly rated characteristic of older workers (van Dalen et al., 2009). Managers have indicated that commitment, reliability and social skills are advantages offered by older workers (van Dalen & Henkens, 2017). Both commitment and loyalty have been used to measure productivity in several European studies (van Dalen et al., 2010). Findings revealed that managers perceive older workers as more loyal and committed, perceptions that may arise at the point of hiring.

3.2.1.4 Health

Stereotypes that older workers are in poor health are common, according to a review of research (Ng & Feldman, 2012). As noted in one study, the image of older workers in physical decline (perceived as not maintaining health and fitness) is common (Collien et al., 2016). In the literature on older worker stereotypes, health is regarded as both physical and mental, tied to research that considers cognition a part of competence. Some employers perceive that older workers (aged 50 and older) lack physical stamina, therefore affecting productivity and job performance (van Dalen & Henkens, 2017). Older workers often put on a more “energetic appearance” when job-seeking to counter the stereotypical images of “older inactive persons with deteriorated health” (Berger, 2009, p. 329). A study in the Netherlands found that job applicants “who appear more vital encounter higher chances for employment” (Karpinska et al., 2013, p. 901), suggesting that employers’ perceptions of older workers’ vitality is a factor.

The stereotype that older workers are less healthy than younger workers is not borne out in the research, therefore psychological and physical health problems are not more common amongst older workers (Ng & Feldman, 2012). However, the existence of negative stereotypes around aging in the workforce can cause feelings of stereotype threat Footnote 5, which then negatively affect mental health (von Hippel et al., 2013). Remarkably, a German study undertaken as that country began widespread promotion of older workers’ potential suggests that some managers interested in promoting early retirement may use mental and physical decline stereotypes to support early retirement (Collien et al., 2016).

3.2.1.5 Work-life balance

Older workers being “more vulnerable to work-family imbalance” is a common stereotype (Ng & Feldman, 2012, p. 821). This stereotype is based on assumptions that older workers focus more on family, community and leisure than do younger workers and consequently have less time and energy for work. While some evidence suggests that older people are invested more in family than in work compared with younger workers, a 2012 analysis concluded that older workers do not experience more imbalance than younger workers. However, a more recent study of Dutch supermarket workers found that those aged 50 to 67 were more likely to feel an imbalance between their work and private life than their co-workers under 30 years old. The authors suggest that this might be explained by older workers being more likely to prioritize goals outside of work (Peters et al., 2019).

It is interesting that the research noted above makes no mention of caregiving responsibilities contributing to imbalance. This may be because those with significant caregiving responsibilities may not be able to maintain labour force attachment. However, working and caregiving is common in Canada (60% of caregivers of all ages are employed), and most caregivers are between 45 and 64 years of age (Sinha, 2013). Research suggests that this cohort of workers could benefit from support through caregiver-friendly workplace policies.

3.2.2 Organizational level

3.2.2.1 Cost and return on investment

A common stereotype about older workers is that they cost organizations more because they use their benefits more frequently, have higher wages, and are near retirement (Posthuma & Campion, 2009). A review of literature showed managers are concerned with health care costs related to employing older workers (Appelbaum et al., 2016). Participants in older worker focus groups in Nova Scotia note this concern, perceiving employers view them as using costly medical and dental benefits (Nova Scotia Centre on Aging, 2018). A related assumption is supported by job seekers’ recognizing that employers are reluctant to train them due to perceived low return on investment (Berger, 2009). However, as adults increasingly delay retirement, investing in training workers in their 50s is likely to reap benefits for an organization (Poulston & Jenkins, 2013). As well, hiring early retirees with pertinent experience or skills over new workers that need training may result in significant cost savings (Karpinska et al., 2013). Furthermore, one review (Posthuma & Campion, 2009) suggests that payback from training investments tends to produce short-term benefits to organizations. There was no evidence found in the articles reviewed for this report that employers hold stereotypes about older workers’ needs for accommodation due to health concerns, the costs associated with addressing this potential need, or both.

3.2.2.2 Fitness for promotion

Some studies examined whether older workers are seen as fit for promotion. National survey data from Australia found that stereotypes of older workers’ adaptability and productivity contribute to perceptions that workers 55 and older “were more likely to be made redundant [and] less likely to be promoted” compared to younger workers (O'Loughlin et al., 2017, p. 99). This perception was found to be held by people of all ages, both males and females. A large study of US retail employees examined the perception that older workers are less likely to be promoted; employees who held this perception were less likely to be engaged at work (James et al., 2013).

3.2.3 Societal level

3.2.3.1 Lump of labour

At the societal level, the “lump of labour” stereotype suggests that younger workers are denied employment opportunities when more older adults engage in work and delay retirement. The FPT Seniors Forum identifies this as a fallacy; in fact, the number of jobs in an economy is variable, not fixed (FPT Ministers Responsible for Seniors, 2018). Researchers from the Stanford Institute for Economic Policy investigated the claim that delayed retirement will cause higher unemployment for younger workers in the US (Munnell & Wu, 2013). They used population survey data for individuals aged 20 to 64 collected between 1977 and 2011, and found no evidence for claims that the presence of older workers reduces opportunities or wages for younger workers, even considering gender and education levels.

3.2.3.2 Retirement age norms

A retirement age norm is the expectation that older workers should retire at a certain age (or age range) (Mulders et al., 2017). Although not a stereotype, a norm is similar in that it is a perception or belief that may impact behaviour. For example, many Canadians view 65 as the normative age of retirement, due to this being the age eligible to receive public pension benefits such as Old Age Security. Research shows that managers, older workers and the general public believe in retirement age norms. Data collected from the 2006 European Social Survey found that most Europeans over age 50 endorse early retirement age norms (Radl, 2012). The results are distinguished by sex: participants endorsed 61 years and 4 months as the mean ideal retirement age for men, but set women’s ideal retirement age as 2-and-a-half years younger. When asked to specify what age was “too old to work” (for men and women, average response was 64.5 years and 60 years, respectively. However, women were more in favour of later retirement than were men (Radl, 2012).

In terms of social class, Radl (2012) found that working class respondents more readily endorsed earlier retirement than did service class and self-employed respondents. One possible explanation for self-employed later retirement age norms may be a “greater degree of work autonomy” as well as “lack of access to public early-retirement schemes” (Radl, 2012, p. 767). Focus groups with older job-seekers in Nova Scotia provide some insight into Canada’s age norms, with many noting employers hold the norm of retirement at age 65. Yet, employers interviewed for this research claimed not to subscribe to the idea of a typical retirement age (Nova Scotia Centre on Aging, 2018).

Managers’ beliefs about retirement timing may affect employment for older workers. Research on recruitment and retention practices in 6 European countries found that organizations where managers hold higher retirement age norms are more likely to support retired workers’ rehiring and working beyond traditional retirement age (Mulders et al., 2017). Nilsson (2018) found that managers intending to retire at the official retirement age were more likely to believe that employees should retire at that age as well.

A stereotype potentially rooted in retirement age norms is that “older workers are quick to retire” (FPT Ministers for Seniors, 2012a, p. 2), yet recent data show that many older adults are working longer. The most recent Census shows that 1 in 5 Canadians aged 65 and older are working (Statistics Canada, 2017). Research on labour force participation and retirement trends suggests that Canadians working past the age of 65 will continue due both to need and a desire for continued employment (Bélanger et al., 2016). While public policy changes in Canada (for example, elimination of mandatory retirement, changes to pension eligibility) provide an opportunity to re-examine the retirement norm at age 65, these changes are relatively recent. There is limited research on their impact, trends of delayed retirement, and the stereotype that older workers are quick to retire.

3.3 Insights and uncertainties around stereotypes about older workers

3.3.1 Older workers’ perceptions

A large body of research explores older workers’ own perceptions of being stereotyped. It confirms older workers’ experiences of age-based stereotypes in the workplace (Rožman et al., 2016) and shows that factors such as intergenerational contact, individual differences including age (Finklestein et al., 2015), having a younger manager, being part of a young workgroup, and doing manual labour (Kulik et al., 2016) may influence an older worker’s perception of being stereotyped.

Older workers’ gender may also be a factor. A study of over 2,000 employees of a national Italian rail company found that women were more likely than men to perceive that others were negatively stereotyping them based on age (Manzi et al., 2018). Another contributing factor is job status, or the level of one’s position within an organization. Research from Australia and the US found that older workers with greater job seniority may be less likely to perceive themselves as targets of negative aged-based stereotypes (von Hippel et al., 2013). The Italian rail employees study also examined job status (participants self-reported if they were supervisors, clerks or manual workers) as a possible factor in perception of being stereotyped, but found no evidence of it, although there are some limitations noted with that study’s sample.

Perceiving that they are being negatively stereotyped based on age is linked to negative consequences for older workers. Dutch supermarket floor workers who perceived age stereotyping at work had negative perceptions of their own employability (Peters et al., 2019). Portuguese blue-collar workers in the manufacturing sector who perceived negative stereotyping from their younger co-workers “held more negative attitudes towards their work” (Oliveira & Cardoso, 2018, p. 199). There is also evidence linking perceptions to performance in older adults. One study from the United Kingdom found that older adults may underperform when they face being compared to a younger person on a task for which older adults are often negatively stereotyped. In the study, older adults showed decreased cognitive performance in completing a task (relating to mathematics and cognition) when they feared that they would be negatively compared to younger adults (Swift et al., 2013). This finding appears consistent with other research which concluded that performance is affected when older adults fear confirming negative age-based stereotypes (Lamont et al., 2015).

A study from the United Kingdom provides insight into how “taking on” a stereotype and its potential consequence may be affected by gender. Examining self-rated leadership potential in workers of different ages and gender, the authors found differences in the impacts of internalized ageist stereotypes: men (but not women) who believed the stereotype that older workers are “warmer” rated themselves as having less leadership potential, while women (but not men) who believed the stereotype that older workers are less competent rated themselves as having less leadership potential (Tresh et al., 2019). Exposure to positive age stereotypes may reduce the consequences of internalizing negative aged-based stereotypes. Being exposed to positive age stereotypes (motivation, ability to work, learn and develop) was found to influence white-collar employees’ retirement intentions in one study. These employees were “less willing to retire early” and had “more interest in learning and development” (Gaillard & Desmette, 2010, p. 86). The diversity of workers, workplace cultures, and roles may be significant in designing interventions to address older workers’ perceptions of stereotyping and its impacts.

3.3.2 Age and gender

“Gendered ageism” refers to intertwined ageism and sexism (Taylor et al., 2013), and may mean older female workers are more vulnerable to ageist stereotypes compared to older male workers. Investigating those who hold gendered stereotypes about older workers, Turek and Henkens (2019) found that employers with gender preferences for job candidates were more likely to have discriminatory age preferences. However, a Dutch study on managers’ employment decisions about early retirees found no evidence that gender affected decision-making when participants were presented with a hypothetical retired job applicant (Karpinska et al., 2013). More broadly, a study involving participants from the general Australian adult population determined that gender did not play a role in whether a person held negative stereotypes about older workers (O’Loughlin et al., 2017).

Evidence does exist that connects gendered age discrimination to a specific stereotype: older women working for European managers who agreed with the statement that “older workers are biding their time until retirement” were less likely to receive workplace training than their male counterparts (Lössbroek & Radl, 2019, p. 2177). This finding is significant given the study’s large sample size and variety of sectors or industries. However, as noted in 3.3.1, perception of being stereotyped has been shown to differ between men and women.

Evidence connecting older worker stereotypes to gender is limited, for the gender of the stereotype holder and for the worker. This does not mean that older adults’ negative stereotypes are the same regardless of gender or have the same impacts; rather, research in this area likely focuses on the broader level of ageism.

3.3.3 Knowledge gaps

Although the body of research on stereotyping includes studies published in the last 10 years, the samples upon which many are based can be 10 to 20 years old. Caution should be exercised in relying on such sources given the dynamic nature of the labour market and recent increases in older adults participating in work. This is especially important when considering stereotypes and evidence about older workers and technology. Today’s older workers have experienced considerable technological change in the workforce and studies using data from 15 years ago or more do not reflect current workers.

Most available studies are based in European countries. A noted knowledge gap is the absence of Canadian empirical studies meeting the review criteria. The lack of Canadian evidence and information about identity, diversity, and living environment make it difficult to draw conclusions about applicability to a Canadian context. Nor does evidence show how stereotyping may differ across Canada’s regions.

Knowledge gaps relating to identity (for example, gender, ability and race), diversity (for example, new immigrants, Indigenous communities and LGBTQ peoples), and living environment (rural, urban and on-reserve), and the intersections among these factors and age, are evident in the literature. More research is needed that examines how age-based stereotypes interact with stereotypes in other identity and diversity categories, such as age and race. It is known that belonging to a racialized group may increase an older adult’s vulnerability to workforce discrimination. For example, a study found that older Black British job applicants were invited to interviews less often than older White British applicants, but both groups were invited far less than younger job applicants (Drydakis et al., 2018). Information on how older adults from minority groups experience age-based stereotyping in the labour force, for instance, would be insightful for informing targeted initiatives.

Many larger empirical studies include participants across a variety of sectors, industries, or job classifications, making it difficult to draw conclusions about where specific stereotypes are held. Where studies did use samples from identified sectors and job classifications, authors did not discuss the relationship between job context and stereotypes. One study involving travel agents found that older job candidates were perceived by potential employers as lower in competence and higher in warmth, but it cannot be concluded that this finding is unique to this industry (Krings et al., 2011).

One article offers sector examples, claiming that “age stereotypes are particularly strong in certain industries, such as finance, insurance, retail, and information technology” (Posthuma & Campion, 2009, p. 165). That review, however, includes studies published in the 1970s and may not be relevant to today’s labour force. A study on ageism in Norwegian working life across all ages concluded that the public sector is more age-friendly than the private sector. A Polish study of employers examining skill requirements and likelihood of recruiting someone over age 50 found that “the chances of an older candidate being hired are especially hindered in jobs requiring computer, physical, social, creative and training skills” (Turek & Henkens, 2019, p.1). The same study found greater acceptance of older workers in health, culture, and public administration, and lower acceptance in trades and service. The research gives little attention to job factors such as part-time employment, and there is no research specific to stereotypes of older worker entrepreneurs or contract workers.

There may even be a more significant knowledge gap regarding ageism in the workplace. Although we know that ageist stereotypes exist, there is little empirical evidence exploring their roots and how such stereotypes lead to discriminatory practice. This in turn reduces our understanding of effective strategies. Unlike corresponding investigation into workplace gender and race, our understanding of ageist stereotypes lags behind (Gahan et al., 2017).

4. Potential action addressing stereotypes about older workers

4.1 Overview

Although there are repeated calls for evidence of promising directions and initiatives (Gahan et al., 2017; Ng & Feldman, 2012), minimal information exists about initiatives addressing any older worker stereotype.Footnote 6 Recommendations or suggestions are generally broad statements about addressing workplace discrimination and calls for initiatives to raise awareness aimed at hiring managers and older workers themselves. Certain jurisdictions (for example, Alberta, Nova Scotia) are implementing action plans to support older workers’ increased workforce participation, but do not appear to target any single stereotype in their approach. The World Health Organization calls for action at a systems level, such as abolishing mandatory retirement ages and implementing anti-discrimination laws.

One noteworthy initiative seeks to create “age-friendly workplaces” that foster older adults’ labour force participation, which may be hindered because of ageist beliefs (Appannah & Biggs, 2015). Similar to the Age-Friendly Communities initiative, workplaces wanting to be age-friendly challenge attitudes and beliefs about older workers and implement practices to create an inclusive culture where performance is not attached to age (Appannah & Biggs, 2015). While the World Health Organization has not established criteria as to what constitutes an age-friendly workplace, initiatives that promote this idea generally consider workplace recruitment and hiring practices and how employers can be supportive of older workers’ needs. For example, the Age-Friendly Workplaces: Promoting Older Worker Participation resource offers guidance on how to recruit and support older workers (FPT Ministers Responsible for Seniors, 2012a). The UK has developed guidelines and a tool kit outlining practical actions to help employers become age-friendly workplaces (Centre for Aging Better, 2018). The The Age Friendly Foundation's ("The Foundation")Program is an initiative based in the US to identify organizations that show a commitment to best practice standards for hiring and employing people age 50 and older (see Appendix C, Initiative #2). This certification tells older adults the employer is committed to a workplace free from age bias or discrimination. Close to 100 employers have earned this certification.

Some literature also suggests age-friendly workplaces are inclusive of everyone, regardless of age, and proposes strategies for valuing a diverse workforce and managing workplace age diversity in general. This focus on “inclusivity” despite age is noted in the literature as a strategy to eradicate age-segregation and intergenerational divide in the workplace.

The following offers a synthesis of available initiatives and other suggestions to mitigate stereotypes about older workers and any ensuing discriminatory behaviours.

4.2 Older workers

Older adults can themselves take on stereotypes, which can affect their well-being in terms of labour force attachment as well as health. Several articles cite the importance of initiatives aimed at older adults to boost their learning and work aspirations and sense of value and worth. As noted, awareness campaigns emphasizing positive information and images about older workers and championing successful older workers are important for older adults. Such examples can include individuals in leadership roles or taking on new challenges. Exposure to this type of positive messaging in workplace and public settings can discredit stereotypes.

Public awareness campaigns should be undertaken by non government organizations as well as government to highlight the harmful effects of taking on stereotypes so that older adults are supported to resist adopting ageist beliefs.

Professional development opportunities to keep older adults’ skill sets relevant is a common suggestion (Abrams et al., 2016; Berger, 2009; Fiore et al., 2012), particularly given workplace changes arising from knowledge-based economies and continually transforming technology. Such opportunities can be supported in the workplace for current employees or for individuals trying to join or rejoin the labour force through employment work centres or community organizations. Professional development opportunities for all workers about work settings that are multi-generational are also recommended to understand respective value systems and other factors that may contribute to work style.

Another suggestion to position older adults better as job candidates is to provide opportunities for learning about résumé framing, which minimizes potential for bias screening and better aligns skills with a position’s required competencies.

4.3 Organizations and employers

Initiatives for organizations and employers include awareness activities along with aids such as tools and guides to support recruitment and hiring practices and human resource policy reviews. For example, WorkBC developed a resource to equip employers with valuable insights into recruiting and retaining older workers (WorkBC, 2008). In addition to drawing attention to hiring and recruitment practices, this resource also contains information about common misconceptions (stereotypes) about older workers (see Appendix C, Initiative #3). There are also suggestions for fostering a work culture supportive of inclusivity; for instance, the resource Age-Friendly Workplaces: Promoting Older Worker Participation, which helps raise general awareness amongst employers (FPT Ministers Responsible for Seniors, 2012a), and the Age-Friendly Workplaces: A Self-Assessment Tool for Employers, can be useful (FPT Minsters Responsible for Seniors, 2012b).

4.3.1 Awareness initiatives

The literature emphasizes the importance of awareness-raising about older workers’ value. While such recommendations are not usually attached to specific stereotypes, this action is suggested to debunk employers’ prevailing negative beliefs about older workers, especially regarding competence and resistance to change as presented in 3.2.1. For example, the study that found younger workers are more resistant to change than older workers suggests that this evidence be used in executives’ awareness seminars (Kunze et al., 2013). To address the competence stereotype, it is suggested that counter-evidence be provided to hiring personnel, given how commonly this stereotype is applied at hiring (Krings et al., 2011). Examples of awareness-raising show several different communications approaches; however, there is limited evidence about their impact.

Several awareness approaches are found in an OECD-developed resource to promote longer working lives (OECD, n.d.). Austria has undertaken an awareness campaign featuring testimonials of successful persons over 50. Belgium launched a campaign, “There is no age for talent”, which includes events organized by unemployed people aged 55 and above to motivate peers and employers. The Danish ministry of employment established a special website recognizing the most innovative or best practices to promote older workers. Resources include tools to help with senior-specific development policy and senior employee appraisals.

Appendix B offers some evidence about existing stereotypes about older workers. To counter these negative stereotypes, messaging based on evidence can be effectively communicated to the general public. Moreover, such campaigns could be designed that more accurately represent current and incoming older workers, who are likely different from the workers upon whom current stereotype research is based. Awareness campaigns could counter stereotypes linked to competency and adaptability and resistance to change. For example, promoting the baby boomer population as one that has embraced technological change throughout their lives (Huyler & Ciocca, 2016) would lead to a more appropriate understanding of this group. Similarly, promoting emerging science around neuroplasticity and the aging brain in relation to older workers could help counter existing beliefs about adaptability and learning capacity. Furthermore, messages about increasing life expectancy and existing retirement norms failing to serve older adults’ social and economic needs will help address prevailing views about exit from the labour force. Within the workplace, inclusive images of workers of all ages should be strategically and widely displayed (for example, lunchroom, washroom, promotional materials). This strategy can reinforce the message these images convey and improve a sense of organizational acceptance and belonging.

4.3.2 Human resources practice

Suggestions targeted at organizations’ recruiting, hiring and promotion practices are key because the individuals following these practices are largely responsible for work atmosphere and employees’ entry and exit. Such policies and practices may intentionally or unintentionally discriminate against older employees.

Advertising of positions is an area that should receive attention. Employers should not use biased or exclusive words and phrases in job postings, and avoid language such as “energetic”, “mature”, and “highly experienced” or reference to number of years’ experience, etc. (Smeaton & Parry, 2018, p.78). To help mitigate “age” as a recruitment hiring factor, an analysis of jobs could be undertaken to understand job tasks and required competencies for success, then use the “competency” information in recruitment, interview, and appraisal processes (Posthuma & Campion, 2009). The use of online application processes with screening features can assist with unbiased assessment of applications.

In organizations where negative stereotypes are more common, such as finance, insurance, and information technology, greater effort can be made to reflect older workers in the recruitment process. For example, “Recruiting advertisements could feature older workers at computers, using the company gym and so forth” (Posthuma & Campion, 2009, p. 182).

Initiatives to counter the belief that older workers are disinterested in training and development should ensure training events employ teaching strategies that support adult learning principles such as active participation, modelling, practical case examples, and self-paced learning (Appannah & Biggs, 2015; Posthuma & Campion, 2009).

In an effort to motivate older adults to prolong their career, an initiative adopted in Norway involved “Milestone Dialogues” between managers and employees aged 55 and 60. These intentional conversations focus on motivation and competence and actions are identified. Managers are trained in the dialogue concept before engaging in these conversations (OECD, 2013).

An interactive online resource for UK managers incorporates many of these suggestions (Age Action Alliance, n.d.) This kit contains specific considerations and practical information for recruiting and retaining older adults, including a content section correcting many common misconceptions about older workers (see Appendix C, Initiative 4).

4.3.3 Fostering inclusive workplaces

Several initiatives can help foster a wholly inclusive workplace regardless of those factors that can divide and pit employees against one another (for example, age, gender, and race). For example, employers could focus on a strength-based workplace model whereby team assignments include individuals of all ages leveraging each other’s strengths. Other suggestions in support of inclusivity include:

- adopt interview and hiring decision processes that include diversity (for example, age, gender, race) (Iweins et al., 2012)

- include age as part of diversity strategies (Berger, 2009)

- regularly assess and monitor management’s attitudes and behaviours towards older workers or diversity more broadly (for example, sex, age, race)

- incorporate greater flexibility into human resource practices and strategies in order to address the needs and values of all employees regardless of their generation (Becton et al., 2014)

- create champions such as a specific manager or committee whose work it is to promote and celebrate diversity in the workplace (for example, age, gender, race) and encourage opportunities for engagement (Smeaton & Parry, 2018)

- prepare future managers to work with older employees and emphasize greater variation within age groups than between them and recognize that variables such as employee skills are more important than age in predicting job performance (Posthuma & Campion, 2009)

- create opportunities for positive intergenerational contact (for example, mentorship, intergenerational partnering), which has been shown to reduce prejudice, in-group identification and diminish vulnerability to the stereotype threat among older workers (Bayl-Smith & Griffin, 2014; Cadieux et al., 2019)

Moreover, drawing on recent work to reduce gender bias in the workplace, the “small wins” model is worthy of consideration to achieve sustainable organizational change. Its 5-step approach is designed to walk organizations through the process of identifying biases, developing solutions, intervening with concrete actions and evaluating wins (see Appendix C, Initiative 5). The model is premised on achieving small wins that can create supporters incrementally, thereby building blocks for larger organizational transformation (Correll, 2017).

4.4 General public

Public awareness initiatives about older workers’ value and importance are usually embedded within campaigns about the aging population and older adults in general, or initiatives through broader aging-specific strategies (for example, Alberta, Nova Scotia, British Columbia). A campaign launched by the National Initiative for the Care of the Elderly is specifically targeting ageism in the workplace with tips and tools (see Appendix C, Initiative #6). Their material describes positive attributes of older workers (to refute existing negative stereotypes) and examples of implicit ageist workplace behaviours (for example, having work contributions ignored, being talked down to by bosses). A public awareness campaign about older workers is noted as part of the City of Boston’s age-friendly initiative (City of Boston, 2017).

Public awareness initiatives should draw on the materials of the ReFraming Aging initiative (Frameworks Institute, 2017) and draw upon a range of media (for example, print, online, social media). Important messages to convey include: challenges to retirement age norms, contributions to economy and society from older workers’ labour force participation, evidence refuting stereotypes about age and disability and cost implications (or promoting a business case for employers), and the heterogeneity of the older population.

Further considerations

Older workers are increasingly participating in part-time and part year work. Non-standard employment (for example, contract work) is also becoming more common for all workers. Understanding stereotypes in a changing and dynamic labour market is important.

Today’s workplaces have the potential to employ individuals from up to 5 generations. To more fully understand stereotyping at play in multigenerational workplaces, a review of perceptions held by, and perceived by, all generations is required.

Older workers are a diverse population. There is no “one type” of older worker.

5. Final thoughts on stereotypes about older workers

The current literature on prevailing stereotypes about older workers provides some insights into who holds these views and the factors that perpetuate them. It finds negative stereotypes of older workers’ competence and adaptability are common. In turn, these negative stereotypes may contribute to perceptions that older workers are unproductive and perform poorly. Conversely, positive stereotypes of older workers’ personal qualities such as warmth are also found. There is some evidence to suggest that holding negative age-based stereotypes lessens as employers or managers and workers themselves become older. However, drawing conclusions is challenging given the variety of ways that stereotypes are defined and measured. While some research published in the last 10 years has examined age-related health stereotypes, there are fewer studies on stereotypes related to work-life balance and organizational and labour force costs of employing older workers. Much research is based on younger workers’ perceptions of older workers, which can perpetuate intergenerational conflict and prohibit inclusive workplaces.

While the research proves that stereotypes exist, there is little examination of causal factors, other than perhaps broader ageist views of aging and the aged in society. More research into the mediators of specific stereotypes could help to identify work sectors and industries where older workers most face negative consequences. Other gaps include the lack of Canadian literature and consideration of identity, diversity and living environment. Mechanisms such as flexible workplace policies and government efforts to remove structural barriers to working longer are important mechanisms to promote older workers’ labour force participation but they do not address stereotypes.

Negative stereotypes have generated discriminatory practices in screening, hiring and performance appraisal processes, contributing to older workers being marginalized or excluded from the labour force. Negative stereotypes have also been linked to older workers themselves reporting a lower self-worth and early exit from the workplace. In view of growing attention to the importance of older adults’ labour force participation, efforts are needed that create for them welcoming, inclusive, and supportive environments. Potential responses to addressing stereotypes include fostering age-friendly workplaces, general and targeted awareness-raising initiatives, and critical assessment of workplace practices to help address ageist attitudes and behaviours targeted towards older workers. These potential responses should be considered in the context of an evolving and dynamic labour market and recognizing the diversity of the older population.

This research focused on stereotypes as one manifestation of ageism, a known barrier to older workers’ labour force participation. However, other factors may come into play as potential barriers to older Canadians continued participation in the labour force. Given the changing and dynamic labour market, more research from the Canadian context is needed on how current and emerging trends and factors influence older adults’ labour force participation.

6. References

Abrams, D., Swift, H., & Drury, L. (2016). Old and unemployable? How age-based stereotypes affect willingness to hire job candidates. Journal of Social Issues, 72(1), 105 to 121. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12158

Age Action Alliance. (n.d.). Employer Toolkit: Guidance for managers of older workers. http://ageactionalliance.org/employer-toolkit/

Agediscrimination.info (n.d.). Poland. http://www.agediscrimination.info/international-age-discrimination/poland

Appannah, A., & Biggs, S. (2015). Age-friendly organizations: The role of organizational culture and the participation of older workers. Journal of Social Work Practice, 29(1), 37 to 51. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2014.993943

Appelbaum, S., Wenger, R., Buitrago, C., & Kaur, R. (2016). The effects of old-age stereotypes on organizational productivity (part one). Industrial and Commercial Training, 48(4), 181 to 188. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-02-2015-0015

Australia Health and Ageing. (2011). The elephant in the room: Age discrimination in employment. National Seniors Australia, Productive Ageing Centre. https://nationalseniors.com.au/research/discrimination/the-elephant-in-the-room-age-discrimination-in-employment

Bal, A., Reiss, A., Rudoph, C., & Baltes, B. (2011). Examining positive and negative perceptions of older workers: A meta-analysis. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 66(6), 687 to 698. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbr056

Bayl-Smith, P., & Griffin, B. (2014). Age discrimination in the workplace: Identifying as a late-career worker and its relationship with engagement and intended retirement age. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44, 588 to 599. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12251

Becton, J., & Jones-Farmer, L. (2014). Generational differences in workplace behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 44, 175 to 189. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12208

Bélanger, A., Carrière, Y., & Sabourin, P. (2016). Understanding employment participation of older workers: The Canadian perspective. Canadian Public Policy, 42(1), 1 to 16. https://doi.org/10.3138/cpp.2015-042

Berger, E. (2009). Managing age discrimination: an examination of the techniques used when seeking employment. The Gerontologist, 49(3), 317 to 332. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnp031

Cadieux, J., Chasteen, A., & Packer, D. (2019). Intergenerational contact predicts attitudes toward older adults through inclusion of the outgroup in the self. Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 74(4), 575 to 584. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbx176

Centre for Aging Better. (2018). Becoming an age-friendly employer. https://www.ageing-better.org.uk/publications/becoming-age-friendly-employer

Cheung, C., Kam, P., & Ngan, R. (2011). Age discrimination in the labour market from the perspectives of employers and older workers. International Social Work, 54(1), 118 to 136. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872810372368

City of Boston. (2017). Age-friendly Boston action plan 2017. https://www.boston.gov/sites/default/files/embed/f/full_report_0.pdf

Collien, I., Sieben, B., & Muller-Camen, M. (2016). Age work in organizations: Maintaining and disrupting institutionalized understandings of higher age. British Journal of Management, 27, 778 to 795. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12198

Correll, S. (2017). Reducing gender biases in modern workplaces: A small wins approach to organizational change. Gender & Society, 13(6), 725 to 750. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243217738518

Desmette, D., & Gaillard, M. (2008). When a “worker” becomes an “older worker”: The effects of age‐related social identity on attitudes towards retirement and work". Career Development International, 13(2), 168 to 185. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430810860567

Dordoni, P., & Argentero, P. (2015). When age stereotypes are employment barriers: A conceptual analysis and a literature review on older worker stereotypes. Ageing International, 40, 393 to 412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12126-015-9222-6

Drydakis, N., MacDonald, P., Chiotis, V., & Somers, L. (2018). Age discrimination in the UK labour marker: Does race moderate ageism? An experimental investigation. Applied Economics Letter, 25(1), 1 to 8. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2017.1290763