A case study on ageism during the COVID-19 pandemic

From: Federal/Provincial/Territorial Ministers Responsible for Seniors Forum

On this page

- List of abbreviations

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Participating governments

- Acknowledgements

- Executive summary and policy recommendations

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Research questions

- 3. Methodology

- 4. Results

- 5. Summary of findings

- 6. Policy recommendations

- 7. Limitations

- Annex 1: Selection of documents

- Annex 2: Keywords used for the search

- Annex 3: List of documents

Alternate formats

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

CHSLD

Centres d’hébergement et de soins de longue durée

COVID-19

Coronavirus disease of 2019

ECLS

Extracorporeal life support

FADOQ

Fédération de l'âge d'or du Québec

FPT

Federal, provincial and territorial

LGBTQ

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (or questioning)

LTC

Long term care

OA

Older adults

PCHs

Personal care homes

PPE

Personal protective equipment

List of figures

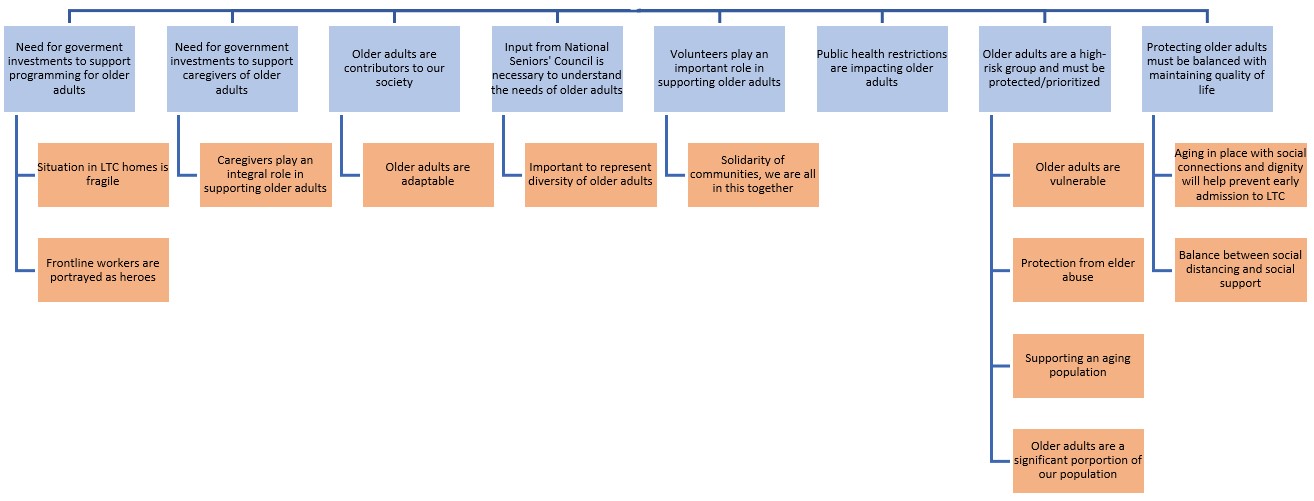

Figure 1: Themes and subthemes from the media discourse

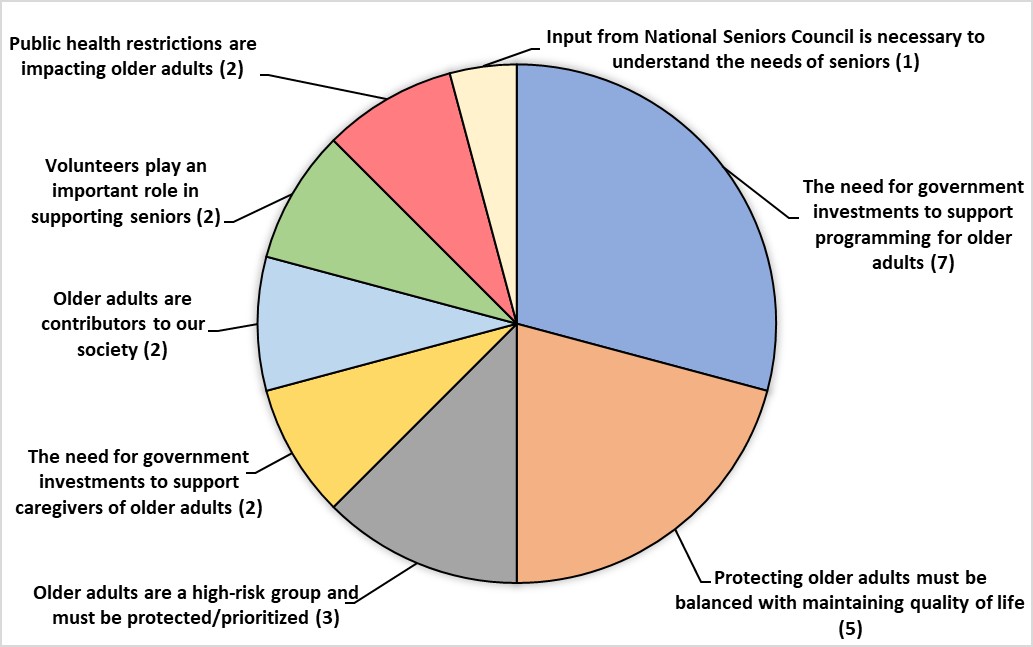

Figure 2: Media discourse themes

Figure 3: Media discourse subthemes

Figure 4: Themes and subthemes from academic discourse

Figure 5: Academic discourse themes

Figure 6: Academic discourse subthemes

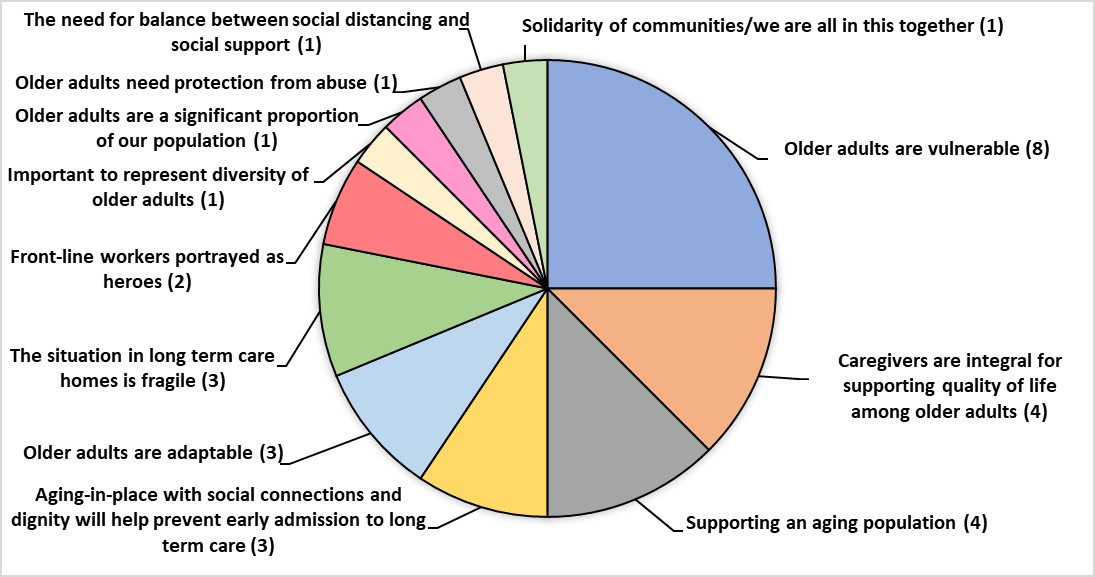

Figure 7: Themes and subthemes from the older adult discourse

Figure 8: Older adult discourse themes

Figure 9: Older adult discourse subthemes

Figure 10: Themes and subthemes from the press briefings

Figure 11: Press briefing discourse themes

Figure 12: Press briefing discourse subthemes

Figure 13: Themes and subthemes from the ministry or the department of communications

Figure 14: Ministry or department communications discourse themes

Figure 15: Ministry or department communication discourse subthemes

List of tables

Table 1: Age reference by number of media articles

Table 2: Description of aging by number of academic articles

Table 3: Age reference by number of press briefings

Table 4: Age reference by number of ministry or department communications

Participating governments

- Government of Ontario

- Government of Quebec*

- Government of Nova Scotia

- Government of New Brunswick

- Government of Manitoba

- Government of British Columbia

- Government of Prince Edward Island

- Government of Saskatchewan

- Government of Alberta

- Government of Newfoundland and Labrador

- Government of Northwest Territories

- Government of Yukon

- Government of Nunavut

- Government of Canada

*Québec contributes to the Federal/Provincial/Territorial Seniors Forum by sharing expertise, information and best practices. However, it does not subscribe to, or take part in, integrated federal, provincial, and territorial approaches to older adults. The Government of Québec intends to fully assume its responsibilities for older adults in Québec.

Acknowledgements

Prepared by Dr. Martine Lagacé, Dr. Tracey O’Sullivan, Pascale Dangoisse, Amélie Doucet, Amanda Mac, and Samantha Oostlander of the University of Ottawa, for the Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) Forum of Ministers Responsible for Seniors. The views expressed in this report may not reflect the official position of a particular jurisdiction.

Executive summary and policy recommendations

- Canadian older adultsFootnote 1 were particularly impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, with over 80% of the COVID-19 related deaths during the first wave occurring in long-term care homes. The situation generated substantial media coverage, as well as government communications and academic research

- Understanding how older adults and the aging process were framed during this health crisis is important because the public discourse can have a significant influence on an individual’s personal experience of aging and relationships with older adults. Previous studies have shown that ageist stereotypes and attitudes are often conveyed through public discourse

- The current study aims to understand how older adults and the process of aging were depicted by the Canadian media, academics, older adults (associations of older adults), as well as government representatives themselves through the first and second waves of the COVID-19 pandemic

- There are 2 main questions that guided this work:

- how did ageism emerge as an issue during the COVID-19 pandemic in the media, research, among older adults, associations of older adults and Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) governments’ communications?

- how did the media, researchers, older adults, associations of older adults, and FPT governments contribute to, or address ageist attitudes, behaviours or discourse?

- To answer these questions, researchers conducted a content analysis of Canadian public documents related to COVID-19 and older adults, published from April to December 2020. These public documents included opinion-editorials (authored by journalists or older adults or associations of older adults), academic articles, and government communications (press briefings and communications generated by Federal, Provincial and Territorial ministries and departments)

- In total, 110 documents were analyzed across the 4 different types of public discourse: 20 media articles, 10 academic papers, 20 papers authored by older adults or associations of older adults, and 60 FPT government communications. Documents were selected over 3 time periods during 2020: (1) April; (2) mid-September to mid-October; and (3) early DecemberFootnote 2

- Content analysis was conducted to align with the research questions as well as findings from previous studies

- The results of this analysis show that ageism was raised as an issue throughout the 4 types of discourses, in 1 of 2 ways, either contributing to ageism or criticizing ageism (as illustrated in Table 5)

- Discourse messaging framed older adults as “victims” in 50% to 88% of all the communications reviewed. Further, the aging process was described as a process of “loss” in the majority of communications produced by the media, the academics, older adults (and associations of older adults) and governments. Communications produced by older adults themselves were the least likely to associate aging (their own aging however) with loss

- Academics criticized ageism and recognized the negative impact of ageism on mental health, social isolation, and access to care, as well as its impact on other forms of discrimination (such as, sexism and racism)

- Older adults and associations of older adults also criticized ageism and recognize its negative impact, however they mostly focused on healthy older adults who lived independently within their own homes/communities, not older adults residing in long term care

- Diverse strengths of older adults – and their contributions to society – were rarely acknowledged, with the exception of older adults communications. In this case however, the diversity of strengths was attributed to healthy older adults

- In general, similar themes and arguments were made throughout the data sources regarding the neglect in long-term care and the importance of caring and protecting older adults during the pandemic

- Similarly to other types of discourse, the media emphasized the vulnerability of older adults living in long term care facilities and the values of protecting them. However, few media articles gave a voice to these older adults (through interviews, for example)

- The importance of conducting more research with Indigenous Elders was underlined by academics

- Press briefings and ministry or government communications from the territories made some references to the important roles and contributions of Indigenous Elders

- While the 4 domains of employment, health and healthcare, social inclusion, and safety and security were identified in all data sources (except government press briefings), the most prominent domain was health and healthcare

- The following policy recommendations are based on the findings from this case study of 110 documents (media articles, academic articles, articles written by older adults or their associations, and government communications)

- Editing of all press briefings and media should be screened to ensure the language used is inclusive and non-ageist. For instance, aging should not be portrayed uniquely as a process of loss; older adults should not be viewed as victims or vulnerable people only in need of protection and care. This important editing includes confirmation that the communication is balanced and recognizes the capacities and contributions of older adults that support pandemic response and resilience

- Building a society that recognizes the importance of listening to the voices of older adults is key. The pandemic has brought older adults into the conversation in a way not typically seen. Older adults are now visible and they have something new to bring to the table: criticizing ageism and providing a heterogenous view of older adults

- The absence of references to Indigenous Elders in different types of communications raises some concerns. Communications should be inclusive, and investments should be made to understand how Indigenous Elders are framed in widespread communication and to what extent and how they experience ageism, through an intersectional lens

- The positive references to Indigenous Elders can serve as inspiration for learning how to address ageism across all communities

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic continues to have a tremendous impact on older adults in Canada, from every facet, be it physical, psychological or social. People living in long-term care homes have been particularly impacted, with more than 80% of the COVID-19 related deaths during the first wave of the pandemic, occurring in these facilities (Royal Society of Canada, 2020). The pandemic generated significant media coverage, government communications, and research from academics. Public discourse (such as, media coverage, government communication) has the power to shape social representations, create norms and expectations that influence personal experience. It is important to examine how the resulting public discourse stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic impacted older adults. Research completed prior to the pandemic demonstrated that public discourse towards older adults contributes directly and inadvertently to ageist stereotypes and attitudes.

Ageism refers to how we think (stereotypes), feel (prejudice) and act (discrimination) towards others or ourselves based on age. It can target younger and older individuals. The focus of the current project is on ageism towards older adults, expressed in different ways, as explained in the following:

Ageism can be hostile when, for example, an aging population is depicted as a real threat to the economy and a burden to the health care system. An example of hostile ageism is the infamous hashtag “#BoomerRemover” that was conveyed on social media at the beginning of the pandemic.

Ageism can be compassionate. In this type of communication, older adults are portrayed as frail and vulnerable and in need of help; not being able to make decisions and having no self-agency. This type of ageism is often seen in the context of caregiving. Although its purpose is to provide help and support, it conveys the idea that all older adults are vulnerable and does not recognize diversity within an age group, which paves the way for patronizing attitudes.

Ageism can also be expressed through intergenerational and intragenerational comparisons. Intergenerational ageism relates to competition or scarcity of resources (that is., the health care system is over-burdened due to an aging population). Intragenerational ageism relates to competition or comparisons between older adults themselves (for example, older adults that are healthy and fit may want to dissociate, or not be identified, with older adults that are facing health challenges).

It is worth noting that compassionate as well as intergenerational or intragenerational ageism are often expressed unconsciously in an implicit or covert manner. On the other hand, hostile ageism is usually expressed explicitly or overtly, that is, consciously.

Studying ageism during the pandemic is important, to gather concrete data to measure its existence. The pandemic, its deadly impact, and the policies and actions put in place to manage it, all appeared to have exacerbated discrimination against older adults. To confirm this fact, examples of ageism need to be identified, examined and measured, to develop policies and legislation to address ageism.

2. Research questions

This report examines how older adults, as well as aging as a process, were depicted by the Canadian media, academics, government representatives and older adults themselves through the first and second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic.

There are 2 main questions that guided this work:

- how did ageism emerge as an issue during the COVID-19 pandemic in the media, research, among older adults, associations of older adults and Federal, Provincial and Territorial (FPT) governments’ communications?

- how did the media, researchers, older adults, associations of older adults, and FPT governments contribute to, or address ageist attitudes, behaviours or discourse?

The following data sources were used to examine the 2 research questions:

- media articles (20 published articles)

- academic research (10 published papers)

- older adults or associations of older adults who have written on this issue (20 published articles)

- FPT government communications (60 press briefings or ministries and department documents)

3. Methodology

In this section

3.1 Selection of documents

To answer the research questions mentioned above, content analysis of Canadian public documents related to COVID-19 and older adults that were published from April to December 2020, was conducted. These public documents included media op-eds (authored by journalists or older adults or associations of older adults), academic articles, and government communications (press briefings and communications generated by Federal, Provincial and Territorial ministries and departments).

Geography and time were used as sampling criteria for the 110 documents included in the study as outlined below. More specifically, media articles, academic articles and articles written by older adults were limited to Canadian authors and sources. Government communications included all 13 provinces and territories and the Government of Canada. More so, documents published in April, mid-September to mid-October and early December were randomly selected. These time intervals align with turning points for the COVID-19 health crisis in CanadaFootnote 3.

Annexes 1 and 2 to this report summarize the sampling approach, as well as key words used to select the document for analysis.

3.2 Analysis of documents

After selection of the documents, a coding grid was developed with the following categories:

- what are the main themes and subthemes? Main themes relate to the central concept of the document, the primary question or issue being addressed. Subthemes focus on notable specific elements of the themes?

- what are the main arguments?

- is ageism being discussed or criticized as an issue (in an implicit or explicit way)?

- do documents contribute to ageism, that is, reflect ageist attitudes (implicitly or explicitly)?

- Implicit attitudes were defined as negative thoughts, feelings or beliefs about older people without the authors seeming to directly promote or endorse age discrimination. Implicit ageism is usually indirect and covert. An example of implicit ageism would be associating the aging of a population with a burden on the economy

- Explicit attitudes were defined as direct statements that represent thoughts, feelings or beliefs about older people that are conscious and made overtly. Hostile ageism reflects explicit ageist attitudes. The hashtag #BoomerRemover that appeared on social media in the early days of the pandemic is an example of explicit ageism

- are there references to specific chronological age (or age range)?

- it is important to note how older age was referred to throughout the documents, to pinpoint whether discriminatory content was focused on a specific age group, and which age groups were impacted the most by this discourse

- how is aging, as a process, described or referred to (loss, gain, both, neither)?

- are there references to older adults’ contribution(s) to society?

- are challenges or potential costs posed by aging or older adults mentioned?

- how are older adults portrayed in regards to other groups?

- what is the role of older adults during the pandemic (victims; fighters; neither; both)?

- domain categorization (employment; health and health care; social inclusion; safety and security)?

- are Indigenous Elders mentioned?

The next section presents the main findings of the content analysis, according to the 4 types of discourse: media, academic, older adult, and government.

4. Results

In this section

4.1 The media discourse (n=20)

The findings relating to the media discourse are based on an analysis of 20 articles from 3 sourcesFootnote 4 : The Globe and Mail (n=7); The National Post (n=7); and La Presse (n=6). The sample of communications included both French (n=6) and English (n=14) articles. The main themes and subthemes within the media, as well as the answers to the main study questions for this data type are presented below.

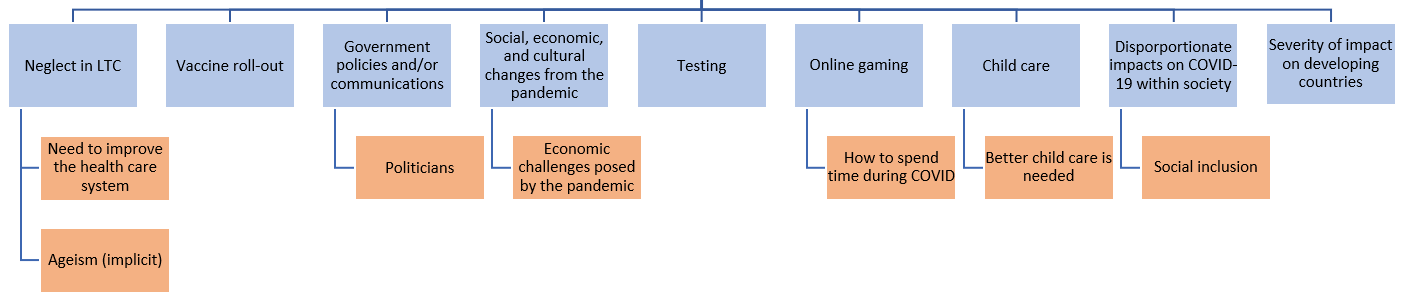

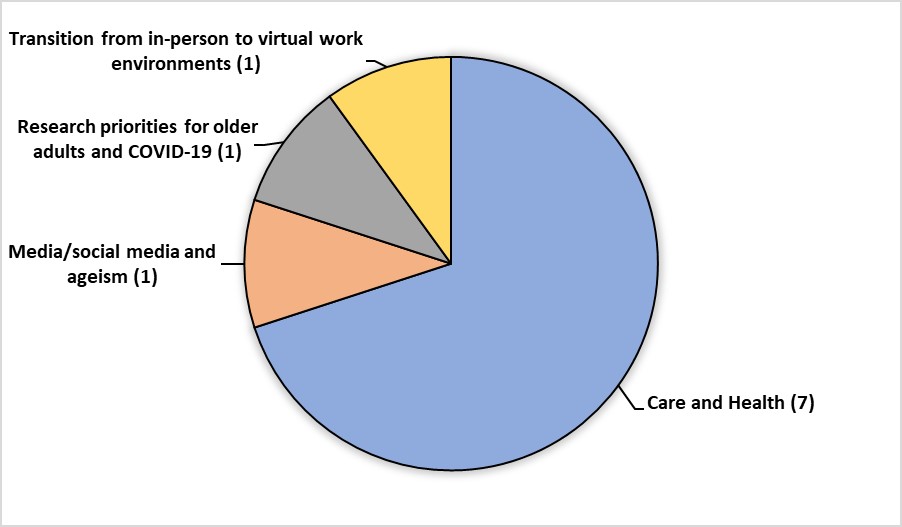

Figure 1 depicts the main themes and subthemes for the media discourse. The main themes are shown in blue, with subthemes shown underneath in orange.

Figure 1 – Text version

The following themes and subthemes emerged from the media discourse:

- neglect in LTC:

- need to improve the health care system

- ageism (implicit)

- vaccine roll-out

- government policies and communications:

- politicians

- social, economic, and cultural changes from the pandemic:

- economic challenges posed by the pandemic

- testing

- online gaming:

- how to spend time during COVID

- child care:

- better child care is needed

- disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 within society:

- social inclusion

- severity of impact on developing countries

Main themes: Media

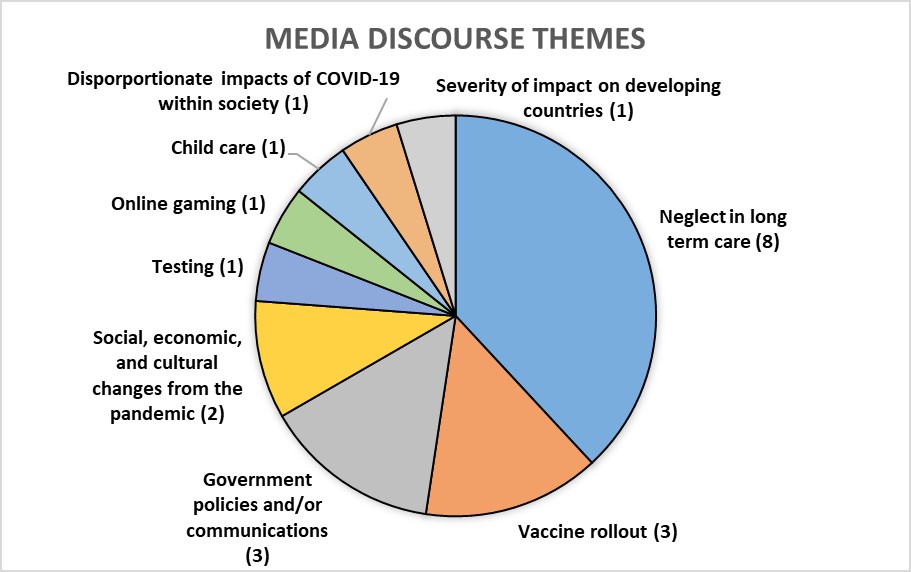

Nine main themes were identified in the media articles. The most salient theme in the media was Neglect in long term care; this theme occurs in 8 (out of 20) articles. The other themes occurred in 1 to 3 articles (out of 20) and are presented in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2 – Text version

| Media discourse themes | Number of articles | Proportion of articles |

| Neglect in long term care | 8 | 38% |

| Vaccine rollout | 3 | 14% |

| Government policies and communications | 3 | 14% |

| Social, economic, and cultural changes from the pandemic | 2 | 10% |

| Testing | 1 | 5% |

| Online gaming | 1 | 5% |

| Child care | 1 | 5% |

| Disproportionate impacts of COVID-19 within society | 1 | 5% |

| Severity of impact on developing countries | 1 | 5% |

Subthemes: Media

Seven subthemes were identified in the media analysis. The need to improve the health care system was a subtheme within 9 (of the 20) media articles. Other subthemes are presented in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3 – Text version

| Media discourse subthemes | Number of articles | Proportion of articles |

| Need to improve the health care system | 9 | 60% |

| How to spend time during COVID-19 | 1 | 7% |

| Ageism (implicit) | 1 | 7% |

| Social inclusion | 1 | 7% |

| Economic challenges posed by the pandemic | 1 | 7% |

| Better child care is needed | 1 | 7% |

| Politicians | 1 | 7% |

Main arguments: Media

The media analyses also identified main arguments presented in the 20 articles. One of the arguments focused on the need to take better care of older adults. One of the lessons from the pandemic is that society is not treating older adults ethically, and more investment (that is, resources, money, time, etc.) is needed to address this problem. Most articles focused on older adults living in long-term care homes, with little or no mention of older adults living within their own homes. The following 3 quotations provide examples of this argument:

“It is the elderly who are especially vulnerable. Mortality rates for old people are the highest. That was painfully seen in our long-term care facilities. It is not an "old person's disease," but the old are most susceptible to its full force. The elderly were also more exposed in another sense. During the lockdown, those who caught the virus were kept in isolation. Even their closest family members were kept away from them in their dying days. Those who did not contract the illness were also kept in isolation, for fear of catching it from a family member. Some circumstances were akin to an updated tale from Charles Dickens' pathos-filled pen. I know of one 96 year old who was unable to be visited by his 93-year-old wife. The very worst and most emotional time to be alone was the very time they were forced to be alone.”

(Rex Murphy, National Post, October 14th, 2020.)

“Ce manque de préparation, ce manque d'expertise, fait partie de l'équation quand on voit à quel point les CHSLD – et les résidences pour personnes âgées – ont été des foyers d'éclosion qui s'apparentent à des incendies de forêt.”

(Patrick Lagacé. (2020, April 10). CHSLD, les brasiers. La Presse+, ACTUALITÉS_4.)

Translation: [This unpreparedness and lack of expertise are part of the equation when we see how many CHSLDsFootnote 7 and retirement residences accounted for outbreaks that spread like forest fires.]

“How is it possible, in 2020, in Canada, that elders entrusted to a licensed care home can be treated worse than dogs at the city pound? How is it conceivable that vulnerable seniors – some with dementia and severe mobility issues – could be left to fend for themselves?”

(André Picard, Globe and Mail, April 1st, 2020: Opinion.)

Is ageism being discussed or criticized as an issue (in an implicit or explicit way): Media

The media analysis revealed 1 explicit example of ageism being discussed, and 4 implicit examples. Interestingly, the word ‘ageism’ is not used, nor is its impact generally discussed. However, its negative impact in terms of poor health and neglect of older adults is acknowledged; in other words, the ‘cause à effet’ is not clearly stated. Some examples are presented below.

Explicit

“Il serait donc apprécié de cesser de nous considérer comme des « pestiférés » potentiels alors que nous sommes en pleine forme et en pleine santé!”

(Serge Loriaux. (2020, December 31). Changer de « cible ». La Presse+, débats_1, DÉBATS_5.)

Translation: [We would therefore appreciate no longer being treated as pariahs when we are fit and healthy.]

(NP View: The COVID-19 crisis has exposed Canada’s shameful treatment of its elderly. (2020, April 17). National Post (Online).)Implicit

“It may be an exaggeration to say Canada's approach to long-term care consists of warehousing the old and: infirm, but we have certainly let standards decline to a point we should be ashamed to acknowledge.”

Does the document contribute to ageism, that is, reflects ageist attitudes (implicitly or explicitly): Media

The media analysis yielded mixed results to the question of whether the media contributes to ageism by reflecting ageist attitudes. Of the 20 media articles, 11 did not contribute to ageism, 8 could be regarded as perpetuating ageist attitudes, and 1 was not classified either way. The following quotation is an example of an article that did contribute to ageism, emphasizing on the deficits (physical, psychological and social) of all older adults in care homes and on their vulnerability.

“By their very nature, people in care homes aren't able to create the sort of noise required to attract the attention of governments. They are old people, confined to their beds, or dependent on walkers or wheelchairs to get around. They aren't great at social networking, crowdsourcing or virtual campaigning. They are largely dependent on others, either relatives, medical professionals or care staff, for basic needs. Many of them, given the chance, would selflessly insist they don't want to be a bother or a burden.”

(NP View: The COVID-19 crisis has exposed Canada’s shameful treatment of its elderly. (2020, April 17). National Post (Online).)

Are there references to specific chronological age (or age range): Media

Eleven out of 20 media articles did not refer to a specific age range or chronological age, when referring to older adults. There is variety among the other articles where age was mentioned, as can be seen in the following table; the first column shows the age groups represented in the media, and the second column indicates the frequency of articles that used that age grouping.

| Reference to age | Number of articles |

| 72 | 1 |

| 73 | 1 |

| 93 year old | 1 |

| 96 year old | 1 |

| 60 and older | 1 |

| 65 and older | 1 |

| 80 and older | 3 |

How is aging, as a process, described or referred to (loss; gain; both; neither): Media

Thirteen out of 20 articles described aging in terms of loss, with references to older adults as the most vulnerable population who are dependent on care. There was 1 exception of an article where the aging process was framed as a gain, referring to active, capable older adults. Two articles referred to aging in a more balanced way (gain and loss), describing older active people going to concerts, but also older people who are ‘warehoused for profit’. Finally, 4 of the articles framed the aging process as neither a gain or loss.

Are there references to older adults’ contribution(s) to society: Media

Of the 20 media articles analyzed, 3 described in vague terms the contributions of older adults to society, in terms of their knowledge or resilience. However, 1 article was particularly positive in its reference to older adults as providing a contribution to society.

(NP View: The COVID-19 crisis has exposed Canada’s shameful treatment of its elderly. (2020, April 17). National Post (Online).)“There is no question that Canadians as individuals love and respect those who brought them into the world, raised them and fashioned a society founded in peace, prosperity and mutual respect.”

Are challenges or potential costs posed by aging or older adults mentioned: Media

Of the 20 media articles analyzed, 5 mentioned the increased economic cost or burden of an ageing society on the health care system. The following is an excerpt from an article discussing child care in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. While the article stresses the importance of turning to a “caring economy” to better care for the young and the old, it emphasizes the costs of an aging population:

“Even without a pandemic, Canada was looking at decades of slow growth, the impact of population aging.”… “As we head into an era of slowth (slow or no growth) owing to population aging, the smallest working-age cohort in 50 years will need all the help it can get”.

(Pandemic realities offer hope of new approach to child care: Opinion. (Globe and Mail, 2020, September 26).)

How are older adults being positioned in relation to other groups: Media

The media analysis explored how older adults are positioned in relation to other age groups. Of the 20 media articles analyzed, 9 did not position older adults in relation to other groups, and the question was not applicable in 7 of the articles. However, 4 positioned older adults against younger generations, or made comparisons between them. The following quotations are examples from the articles that positioned older adults in relation to younger age groups.

“On est tous d'accord que les effets indirects de la pandémie sur les jeunes sont sérieux. Mais ce n'est pas en exacerbant ses effets directs sur les aînés qu'on les réglera.”

(Philippe Mercure. (2020, October 17). Les gens vulnérables ne vivent pas dans les nuages. La Presse+, DÉBATS_1, DÉBATS_3.)

Translation: [There is a general consensus that the pandemic’s indirect effects on youth are serious. But amplifying its direct effects on older adults will not mitigate these indirect effects.]

“Des grands-parents qui jouent avec leurs petits-enfants, mais aussi des aînés qui jouent en club. Et ce sont loin d'être les personnes les plus polies en ligne! Ils se sentent comme au bistro!”

(Pierre-Marc Durivage. (2020, April 30). Boom des plateformes de jeu virtuel. La Presse (site web).)

Translation: [There are grandparents playing with their grandchildren, but also seniors playing as a club. And they are not the most polite people online! They’re behaving as if they were in a pub!]

“However, “we're all in this together” doesn't ring quite true when you take cognizance of this division, this two-tiered impact of COVID. There needs to be something a little beyond words to give that rally cry force.”

(Murphy, R. (2020, October 14). The full impact of Covid is not borne by all, National Post.)

What is the role of older adults during the pandemic (victims; fighters; neither; both): Media

Message framing can influence ageist attitudes. Therefore, one part of this media analysis was an exploration of how older adults were presented in various roles. More specifically, this media analysis investigated whether older adults were:

- framed in terms of being victims

- framed as fighting back or resisting any challenges imposed by the pandemic

- neither of these perspectives

- both as victims and fighters

While 4 articles did not present older adults in any of these roles, 1 media article (out of 20) presented older adults as fighters, stating

“how many older adults are very aware of health measures and are very capable of following them.”

(Serge Loriaux. (2020, December 31). Changer de « cible ». La Presse+, débats_1, DÉBATS_5.)

Domain categorization (employment; health and health care; social inclusion; safety and security): Media

Not surprisingly, the domain represented most in the media articles throughout the time periods covered was health and health care (n=15). Social inclusion was represented in (n=3) articles, employment (n=1), and safety and security (n=1).

Are Indigenous Elders mentioned: Media

Just 1 media article of the 20 reviewed mentioned Indigenous peoples. When mentioned, it was in combination with the key words “older adults” and “Covid-19”. The following quotations are from that article.

“But thorny questions will arise, such as: Who is an essential worker? Public Safety Canada actually has a list, but it's as long as your arm. Grocery store workers? Teachers? Police officers? Truckers? Family caregivers? How do you choose among them? What about people living with homelessness? Indigenous peoples? COVID-19 has hit racialized and low-income populations hardest. How do we ensure that the inequities exposed by the pandemic are not perpetuated in the vaccine rollout?”

(Picard, A. (2020, December 8). Why we can ignore anti-vaxxers right now: Opinion. The Globe and Mail, A11.)

4.2 The academic discourse (n=10)

The findings related to the academic data are based on an analysis of 10 papers published in peer reviewed journals and written by Canadian scholars over the time periods targeted for this report. Eight papers are published in English, and 2 in French. The following section presents the main themes and subthemes within the academic discourse, as well as the answers to the main study questions for this data source.

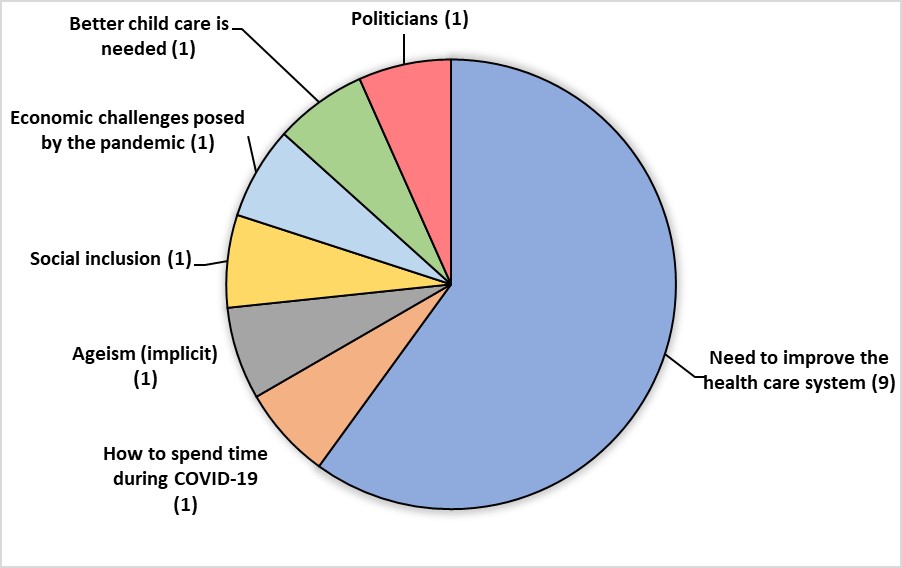

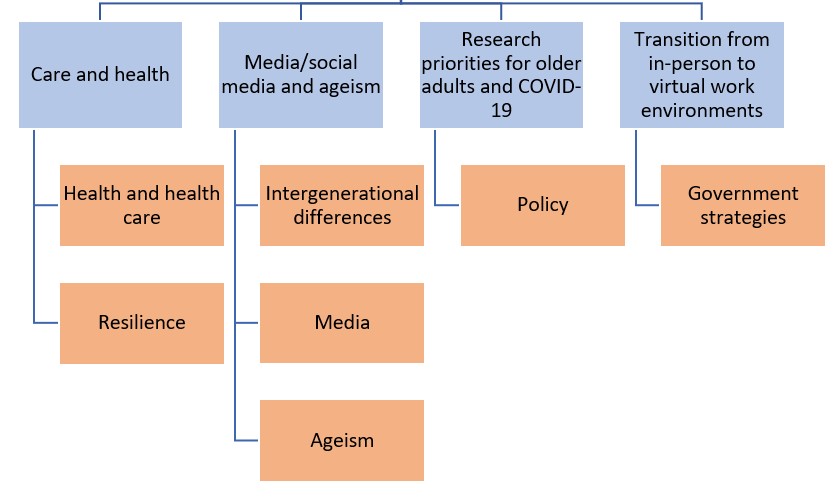

Figure 4 depicts the main themes and subthemes for the academic discourse. The main themes are shown in blue, with subthemes shown underneath in orange.

Figure 4 – Text version

The following themes and subthemes emerged from the academic discourse:

- care and health:

- health and health care

- resilience

- media or social media and ageism:

- intergenerational differences

- media

- ageism

- research priorities for older adults and COVID-19:

- policy

- transition from in-person to virtual work environments:

- government strategies

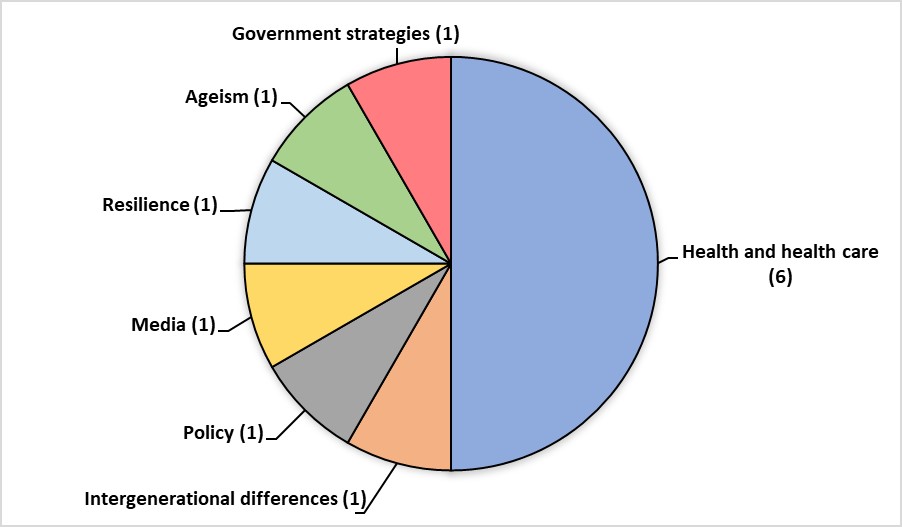

Main themes: Academic

Similar to the media discourse, scholars focused on the theme of Care and Health. This theme was present in 7 of the 10 papers analyzed. The other main themes are presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5 – Text version

| Academic themes | Number of articles | Proportion of articles |

| Care and health | 7 | 70% |

| Media or social media and ageism | 1 | 10% |

| Research priorities for older adults and COVID-19 | 1 | 10% |

| Transition from in-person to virtual work environments | 1 | 10% |

Subthemes: Academic

Seven subthemes were identified in the analysis of academic articles. Health (physical and mental) and health care was the most prevalent subtheme. Other subthemes are presented in Figure 6 below.Footnote 8

Figure 6 – Text version

| Academic subthemes | Number of articles | Proportion of articles |

| Health and health care | 6 | 50% |

| Intergeneration differences | 1 | 8% |

| Policy | 1 | 8% |

| Media | 1 | 8% |

| Resilience | 1 | 8% |

| Ageism | 1 | 8% |

| Government strategies | 1 | 8% |

Main arguments: Academic

The analysis of academic articles included identification of main arguments presented in the 10 papers. Similar to the media discourse, one of the main arguments focused on the need to do better and do more for older adults, in terms of funding and policies. However, contrary to the media communications, the academic discourse focused less on long term care and tackled issues such as mental health of all older adults (including those not living in long term care facilities), their capacity to be resilient, and finally, the importance of addressing the problem of ageism.

Is ageism being discussed or criticized as an issue (in an implicit or explicit way): Academic

Four papers (out of 10) explicitly addressed the issue of ageism and the need to tackle it. In these papers scholars argue that, amongst other issues that have been magnified, the pandemic has revealed the prevalence of ageism in our society. They further argue that ageism is a correlated factor of the lack of preparation and prevention in terms of pre-pandemic care for older adults, as illustrated in the following quotes.

"La situation actuelle a fait ressortir la nécessité de repenser le statut et le rôle des personnes âgées dans notre société et celle d’examiner spécifiquement l'impact et l'influence de l'âgisme dans la prise de décision et la prestation des soins."

(Rylett, R. J., Alary, F., Goldberg, J., Rogers, S., & Versteegh, P. (December 1st, 2020). La COVID-19 et les priorités de recherche sur le vieillissement. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 39(4), 506–512.)

Translation: [The current situation has highlighted the need to rethink the status and role of older adults in our society and to specifically address the impact and influence of ageism in decision-making and the delivery of care.]

“Unfortunately, the wake of COVID-19 has brought a resurgence of hostile messages on social media, even classifying as hate speech, that exhibit ageism against older adults.”

(Meisner, B. June 24th, 2020. Journal of Leisure Science.)

Does the document contribute to ageism, that is, reflects ageist attitudes (implicitly or explicitly): Academic

The majority of academic papers did not contribute to ageist attitudes (n=9). One document that could be regarded as potentially perpetuating ageist attitudes relates to the usage of age as a criteria (following health condition and frailty) when deciding to give critical care in a pandemic context. International scholars have criticized using age as a primary decision making criteria for critical care provision and consider this practice an expression of ageism.

Explicit

“The number of patients that can be placed on ECLS is small and should be decided on a case-by-case basis. Definite exclusion criteria include age older than 60 years old.”…

(Development of a framework for critical care resource allocation for the COVID-19 pandemic in Saskatchewan (Valiani, S., Terrett, L., Gebhardt, C., Prokopchuk Gauk, O. & Isinger, M. September 1st, 2020, Canadian Medical Association.).)

Are there references to specific chronological age (or age range): Academic

The majority of academic papers made reference to specific chronological age or age range with the exception of one. Reference to age of older adults varied depending on the scholar, ranging from 50 years old to 90 years old. Of note, such variance was not observed in the media documents.

How is aging, as a process, described or referred to (loss; gain; both; neither): Academic

The academic papers offered a more balanced description of the aging process than media articles, as can be seen in the following table:

| Description of aging as a process | Number of articles |

| Both (loss and gain) | 7 |

| Gain | 1 |

| Loss | 1 |

| Neither | 1 |

In cases where the depiction of the aging process refers to both gains and losses, the former seemed to apply solely to active and healthy older adults while losses referred to those living in long term care homes, as illustrated in the examples below.

Both

“ Nous avons tendance à considérer les personnes âgées comme des personnes vulnérables. Cependant, cette perspective est remise en question lorsque nous tenons compte de leurs points de vue, de leur créativité et de leur résilience, et lorsque nous adoptons une optique plus globale, en fonction de laquelle la santé n’est pas le seul élément à prendre en compte, même en temps de pandémie.”

(Meisner et al., (December 12th, 2020). La nécessité des approches interdisciplinaires et collaboratives pour évaluer l'impact de la COVID-19 sur les personnes âgées et le vieillissement, Joint statement from Canadian Association of Gerontology and The Canadian Journal of Aging.)

Translation: [Our tendency [...] to see older people as vulnerable is challenged when we take notice of their points of view, creativity, and resilience, and when we take a more holistic view that recognizes that there is more than health to think about even during a pandemic.]

Gain

“Canadian older adults are highly diverse, and generally healthy, engaged and active…”

(Wister, A., & Speechley, M. (September 9th, 2020). COVID-19: Pandemic Risk, Resilience and Possibilities for Aging Research. Canadian Journal on Aging.)

Are there references to older adults’ contribution(s) to society?: Academic

Of the 10 academic papers analyzed, only 3 spoke to the contributions of older populations, but in a vague manner:

“What can we learn – both positive and negative – from societies with large proportions of older persons, such as Italy and Japan?”

(Wister, A., & Speechley, M. (September 9th, 2020). COVID-19: Pandemic Risk, Resilience and Possibilities for Aging Research. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement.)

Of particular interest is 1 paper that indicated that older workersFootnote 9 had an easier time transitioning to a virtual context compared to younger ones because of their experience:

“Maybe - older practicians actually had an easier time than younger ones transitioning to online therapy sessions”

(Békés, V., Doorn, K.A., Prout, T.A, & Hoffman, L. (June 26th, 2020). Stretching the Analytic Frame: Analytic Therapists’ Experiences With Remote Therapy During COVID-19.)

Corporate memory or experience among a workforce is an asset that can support continuity of operations in a disaster. Adapting or transitioning easily is an example of a strength that contributes to organizational resilience. The above quotation about ease in transitioning to online settings is interesting as it counteracts one of the most prevalent stereotypes: that older workers cannot adapt to new technologies.

Are challenges or potential costs posed by aging or older adults mentioned: Academic

Six of the 10 academic papers did not refer to challenges or potential costs posed by aging or older adults. The 4 remaining papers did focus on the burden on health care (physical and mental) generated by an aging population, as illustrated below:

“Yet, most of the funding for health care, including for long-term care public facilities, come from the provinces, which are increasingly struggling to finance health care costs in a context of accelerated population aging…”

(Béland, D., & Marier, P. (July 1st, 2020). Covid-19 and Long Term Care Policy for Older People in Canada. Journal of Aging & Social Policy.)

How are older adults being positioned in regards to other groups: Academic

In 7 out of 10 papers, scholars discussed and criticized the tendency, in popular discourse (especially on social media), to associate and compare older generations to younger generations. They argued that making COVID-19 mainly a “seniors problem” paved the way and legitimized discriminatory attitudes from younger to older generations. In the following quotation, authors critize expressions of hostile and intrageneratioal ageism in the context of the pandemic:

“Although COVID-19 knows no borders, physical or social, it has clearly become an aging-related disease. On the one hand, gerontologists have already become important contributors to COVID-19 knowledge, practice and research. On the other hand, there is a backlash of younger and working populations, fed by media and political hype, who believe that they are less susceptible, and if they do become infected, the symptoms will be less serious than for older populations. […] Some of these views have been articulated as part of the "ok boomer" movement, which has pitted younger and older generations against each other. Other individuals and groups have expressed the view that the COVID-19 pandemic is largely a “seniors problem” and as such should not shut down the economy and society to the level that has occurred. Some politicians have even gone so far as to suggest that older people ought to consider sacrificing themselves for the health of others, including that of the economy.”

(Wister, A., & Speechley, M. (September 1st, 2020). COVID-19: Pandemic Risk, Resilience and Possibilities for Aging Research. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement.)

What is the role of older adults during the pandemic (victims; fighters; neither; both): Academic

Similar to the media discourse reviewed, but to a lesser extent, 5 out of 10 academic papers presented older adults as victims during the pandemic, here again reinforcing the perception of older adults as being “the most vulnerable”. Of the other 5 academic papers, 3 offered a more balanced view and 2 presented older adults in neither of these roles (not victims or fighters).

Victims

“Nursing homes have become “ground zero” for the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic in North America.1 In both the United States and Canada, the first recorded COVID-19 deaths and outbreaks occurred in nursing homes, with case fatality rates in these settings reported to be as high as 33.7%.2 Since that time, more than 25,000 nursing home residents have died of COVID-19 in the United States, whereas more than 80% of all COVID-19 deaths in Canada are among nursing home residents.”

(Stall, N. M., Farquharson, C., Fan‐Lun, C., Wiesenfeld, L., Loftus, C. A., Kain, D., Johnstone, J., McCreight, L., Goldman, R. D., & Mahtani, R. (July 1st , 2020). A hospital partnership with a nursing home experiencing a COVID‐19 outbreak: Description of a multiphase emergency response in Toronto, Canada. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society.)

“The differential mortality risks suggest that this is largely a “gero-pandemic,” which has brought the field of aging into center-stage, in both pathogenic and salutogenic contexts.”

(Wister, A., & Speechley, M. (September 1st, 2020). COVID-19: Pandemic Risk, Resilience and Possibilities for Aging Research. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement.)

Both

" La COVID-19 n’est pas une maladie équitable. Bien entendu, les personnes âgées, handicapées et celles souffrant de problèmes de santé sous-jacents sont plus à risque de souffrir de formes plus graves de COVID-19." […] "Nous avons tendance à considérer les personnes âgées comme des personnes vulnérables. Cependant, cette perspective est remise en question lorsque nous tenons compte de leurs points de vue, de leur créativité et de leur résilience, et lorsque nous adoptons une optique plus globale, en fonction de laquelle la santé n’est pas le seul élément à prendre en compte, même en temps de pandémie."

(Meisner et al., (December 12th, 2020). La nécessité des approches interdisciplinaires et collaboratives pour évaluer l'impact de la COVID-19 sur les personnes âgées et le vieillissement, Joint statement from Canadian Association of Gerontology and The Canadian Journal of Aging.)

Translation: [“COVID-19 is not an equitable disease. Of course, older people, people with disabilities, and people with underlying health conditions are at higher risk of contracting more serious forms of COVID-19.” “Our tendency [...] to see older people as vulnerable is challenged when we take notice of their points of view, creativity, and resilience, and when we take a more holistic view that recognizes that there is more than health to think about even during a pandemic.”]

Domain categorization (employment; health and health care; social inclusion; safety and security): Academic

In the 10 academic papers examined, the domains most represented in the articles throughout the time periods covered were health care (n=4) and social inclusion (n=4), followed by employment (n=1), and safety and security (n=1).

Are Indigenous Elders mentioned: Academic

Only 1 paper out of 10 called for more research with Indigenous older adults, especially in reference to their needs, and assessment of these needs. The following quotation is from that paper:

“En cette période de crise associée à la COVID-19, il est essentiel que les chercheurs mènent des travaux sur le vieillissement qui tiennent comptent des populations autochtones et des autres populations sous-représentées, des facteurs socio-économiques et culturels, de l’accès équitable aux ressources du système de santé et de l’engagement des patients spécialement lorsque ceci concerne les personnes âgées.”

(Rylett, R. J., Alary, F., Goldberg, J., Rogers, S., & Versteegh, P. (December 12th, 2020). La COVID-19 et les priorités de recherche sur le vieillissement. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement.)

Translation: [“It is crucial during this COVID-19 crisis for investigators carrying out research on aging to consider Indigenous and other under-represented populations, socio-economic and cultural factors, equitable access to health system resources, and patient engagement, particularly as these factors relate to older adults.”]

4.3 The older adult (associations of older adults) discourse (n=20)

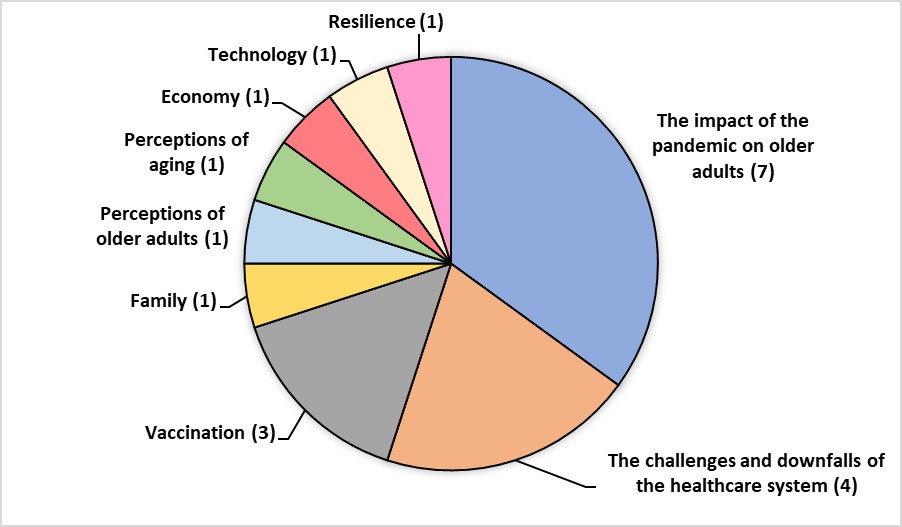

Main themes: Older adults

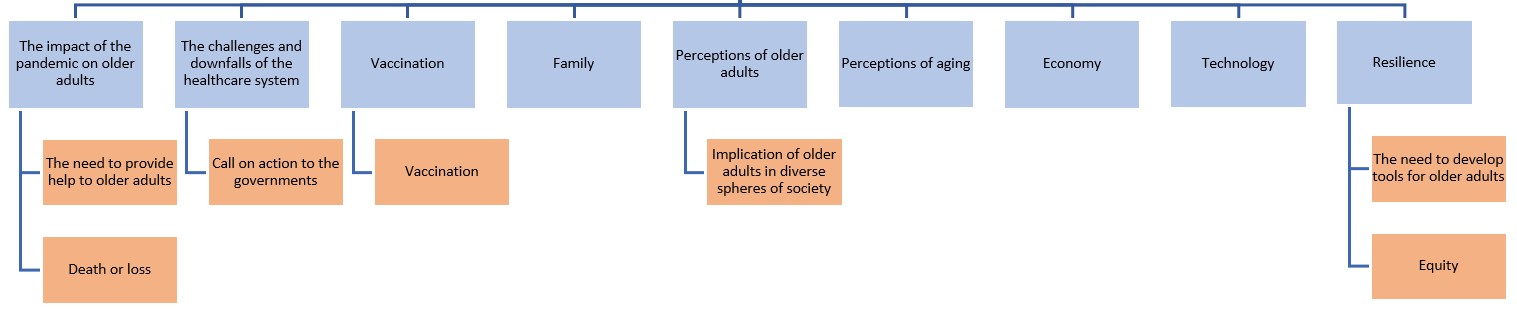

The analysis of 20 documents authored by older adults revealed 2 main themes focused on the negative impact of the pandemic on older adults (n=7) and the downfalls of the health care system – especially as it relates to long term care (n=4). It is important to note that the impact of the pandemic is discussed in regards to different groups of older adults (such as, childless older adults, LGBTQ seniors) and, as such, offers a more diverse and heterogeneous analysis of the impact, one that was not reflected in the media or in the academic documents. Other themes were spread equally, as illustrated in Figure 8.

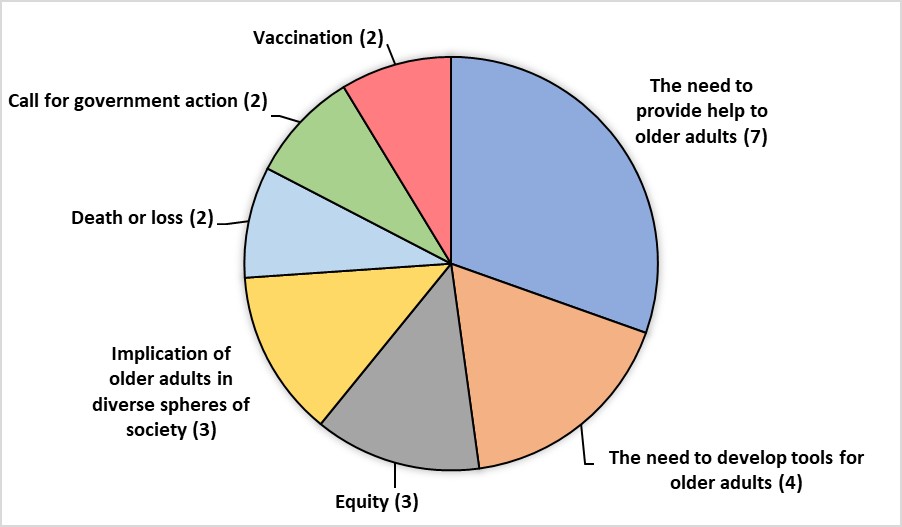

Figure 7 depicts the main themes and subthemes for the older adult discourse. The main themes are shown in blue, with subthemes shown underneath in orange.

Figure 7 – Text version

The following themes and subthemes emerged from the older adults discourse:

- the impact of the pandemic on older adults:

- the need to provide help to older adults

- death or loss

- the challenges and downfalls of the healthcare system:

- call on action to the governments

- vaccination:

- vaccination

- family

- perceptions of older adults:

- implications of older adults in diverse spheres of society

- perceptions of aging

- economy

- technology

- resilience:

- the need to develop tools for older adults

- equity

Figure 8 – Text version

| Older adults themes | Number of articles | Proportion of articles |

| The impact of the pandemic on older adults | 7 | 35% |

| The challenges and downfalls of the healthcare system | 4 | 20% |

| Vaccination | 3 | 15% |

| Family | 1 | 5% |

| Perceptions of older adults | 1 | 5% |

| Perceptions of aging | 1 | 5% |

| Economy | 1 | 5% |

| Technology | 1 | 5% |

| Resilience | 1 | 5% |

Subthemes: Older adults

Seven subthemes were identified in the older adults analysis. The need to provide help and develop tools to support older adults during the pandemic were the most prevalent subthemesFootnote 10 . Other subthemes are illustrated in Figure 9 below.

Figure 9 - Text version

| Older adult subthemes | Number of articles | Proportion of articles |

| The need to provide help to older adults | 7 | 30% |

| The need to develop tools for older adults | 4 | 17% |

| Equity | 3 | 13% |

| Implication of older adults in diverse spheres of society | 3 | 13% |

| Death or loss | 2 | 9% |

| Call for government action | 2 | 9% |

| Vaccination | 2 | 9% |

Main arguments: Older adults

Similar to the media discourse, the main arguments sustained in the older adults’ documents related to the vulnerability of older adults and the call to action from governments and civil society (9 articles out of 20). However, older adults offered a more nuanced argument in that they also focused on the resilience of older adults and provided a more positive view of the process of aging. Moreover, this positive framing of aging targeted independent older adults.

Is ageism being discussed or criticized as an issue (in an implicit or explicit way): Older adults

Eight articles out of 20 written by older adults or their associations criticized ageism as an issue. Ageism was often discussed along with other forms of discrimination, such as racism. When ageism was criticized, it primarily focused on healthy older adults living independently within their own communities, not older adults who are residents of long term care homes or similar communal care facilities.

“Le Réseau FADOQ souhaite sincèrement que 2020 changera à jamais la façon dont on considère les aînés dans la société. J'en appelle à la compassion et au sens du respect des Québécois. Chérissons les aînés. Soyons bienveillants. Mais forçons aussi la main des gouvernements qui négligent d'accorder à de trop nombreux aînés des revenus minimalement décents.”.

(Gisèle Tassé-Goodman, Réseau FADOQ , December 8, 2020, La Presse.)

Translation: [The Réseau FADOQFootnote 11 sincerely hopes that 2020 will forever change how older adults are viewed in society. I call on the compassion and respect of all Quebecers. Let's cherish our seniors. Let's remember to be kind. But let's also force the hand of governments that often fail to provide too many seniors with minimally decent incomes.]

"Tout ça pour des vieux blancs malades. Ce monsieur semble ignorer qu'aux États-Unis, une très forte proportion des personnes touchées sont des Noirs, surtout des vieux sans doute, ayant de fortes préconditions découlant essentiellement de la ségrégation raciale, c'est-à-dire du racisme. Et bien sûr, l'âgisme et le mercantilisme sont les pierres d'assise du raisonnement de M. Le Boucher."

(Simone Landry, retired professor, May 23rd, 2020, Le Devoir.)

Translation: [All this for sick old white people. This gentleman seems to be unaware that in the United States, a very high proportion of people with COVID-19 are blacks, presumably most of them seniors, with serious preconditions stemming essentially from racial segregation, that is racism. And of course, ageism and commercialism are the cornerstones of Mr. Le Boucher's reasoning.]

“La pensée a besoin de petites cases pour classifier les gens. Une fois classés, tout devient plus simple. On est un boomer, un millénial ou autre chose et nous sont associées certaines valeurs, certains défauts typiques de cette catégorie (ou qu'on leur prête sans analyse trop approfondie).”

(Pierre Cliche, May 30th, 2020, Opinion, La Presse.)

Translation: [Thought needs to categorize people into little boxes. Once people are categorized, everything becomes easier. We're a boomer or a millennial or anything else, and some typical values and flaws are associated with each category (or the way each category is perceived, without in-depth analysis.]

Does the document contribute to ageism, that is, reflects ageist attitudes (implicitly or explicitly): Older adults

There were 6 articles out of 20 that used language or ideas that could be interpreted as contributing to ageism. The analysis revealed the presence of self-ageism, indicating that older adults have integrated existing negative stereotypes based on age (for example, the presumed non-productivity of older adults).

“Dear editor, When the vaccine for COVID-19 rolls out, it should not start with us old folk.” […] “We old folk are not productive members of society and can shelter at home if concerned.”

(Ian Kimm, December 3rd, 2020, BC Local News.)

Are there references to specific chronological age (or age range): Older adults

There was great variety in references to age ranging from 50 and above to 85 and above. The most frequent age categories were either 65 and above (n=3) or 70 or above (n=2):

“High-dose flu vaccines are covered for all older adults over 65 years of age, but only through a physician or via public health.”

(Canadian Association for Retired Persons, CARP, April 2nd, 2020.)

Interestingly, a survey conducted by Age-Well (a Canadian technology and aging network), referred to adults in their 80s as fully capable of using technologies.

“Olive Bryanton, 83 ans, de Hampshire à l’Île-du-Prince-Édouard, n’imagine pas la vie pendant la pandémie de COVID-19 sans technologie.”

(Age-Well, September 29th, 2020; survey was also reported by the Canadian Association for Retired Persons, CARP on April 2nd, 2020.)

Translation: [Olive Bryanton, 83, of Hampshire, Prince Edward Island, can't imagine life during the COVID-19 pandemic without technology.]

How is aging, as a process, described or referred to (loss; gain; both; neither): Older adults

Eleven out of 20 articles written by older adults or their associations described aging in terms of loss, with references to older adults as the most vulnerable population to COVID-19. Some of these articles reflected self-ageism whereby older adults seemed to identify with and accept negative age-based stereotypes. On the other hand, a total of 6 articles offered a more balanced view of the aging process, describing it either in terms of gains (n=3) or both in terms of losses and gains (n=3). The following are examples of framing aging as a loss, followed by an example of a gain.

Loss

“I will probably have died or become too feeble to take. While I wait for a successful COVID-19 vaccine to be found, I find myself becoming an angry, bitter old lady.”

(Mary Moir, 82 years old; October 23rd, 2020, Branpton News.)

Gain

“Learn to use facetime or skype on your phone or computer so you can watch a show or a movie on one while video chatting on the other, simultaneously.”

(Canadian Associations for Retired Persons, CARP, April 2nd, 2020.)

Are there references to older adults’ contribution (s) to society: Older adults

Of the 20 papers analyzed, 4 clearly illustrated older adults calling for governments to acknowledge what they contribute or bring to society. The following quotation is an example of such framing:

“ Je veux bien que l'on fasse de nous des sages ou des bâtisseurs, mais je préférerais qu'on nous considère comme des citoyens actifs, participant encore de plein droit au développement de la société et capables d'assumer leur part du fardeau collectif. ”

(Pierre Cliche, May 30th, 2020, La Presse.)

Translation: [I don't mind us being turned into elders or builders, but I would prefer us to be perceived as active citizens who are still full participants in the development of society and able to bear their share of the collective burden.]

Are challenges or potential costs posed by aging or older adults mentioned: Older adults

The analysis revealed that out of 20 articles, 4 focused on the costs and challenges posed by an aging population, precisely on the increased economic costs or burden of an aging society on the health care system. The remaining 16 articles did not discuss the potential challenges or costs posed by aging.

How are older adults being positioned in regards to other groups: Older adults

In these documents, older adults were positioned in relation to other age groups, by older adults themselves. Of the 20 articles analyzed, 8 positively positioned older adults in relation to other groups, 2 did so in a negative manner, while the question was not applicable in 10 of the articles. The following quotations are examples where older adults were positively compared to younger age groups:

“En ce qui concerne les médias sociaux, si populaires auprès des jeunes, ils sont également très utilisés par les personnes âgées. ”

(Le Réseau de Centres d’excellence, AGE-WELL, Prince Edward Island, September 29th, 2020.)

Translation: [Social media, which is so popular with young people, is also widely used by older adults.]

“Some older adults can manage the stress related to Covid-19 better than younger adults. Their life experience enhances the ability to put difficult times into perspective.”

(Alberta Council on Aging, Newsletter Summer 2020 Edition.)

What is the role of older adults during the pandemic (victims; fighters; neither; both): Older adults

Similar to the media discourse, it was common for older adults to focus on their role as victims (11 out of 20). Five articles offered a more balanced view; 2 articles did not present older adults as victims nor fighters. Two articles presented older adults as fighters.

Domain categorization (employment; health and health care; social inclusion; safety and security): Older adults

Health and health care (n=8) were the domains most frequently discussed among the 20 articles, followed by safety and security (n=7), equity and inclusion (n=4) and employment (n=1).

Are Indigenous Elders mentioned: Older adults

None of the 20 articles discussed aging in relations to Indigenous Elders or Indigenous communities.

4.4 Government communication discourse (n=60)

This section of the analysis is divided into 2 main sections: press briefings and ministry or department communications. The findings for the press briefings are presented first, in full, followed by the findings for the ministry or department communications. The analyses are based on 60 government communications, including 32 press briefings and 28 ministry or department communications. All Canadian provinces and territories, and the federal government, are represented in this part of the dataset.

4.4.1 Press briefings (n=32)

Main themes: Press briefings

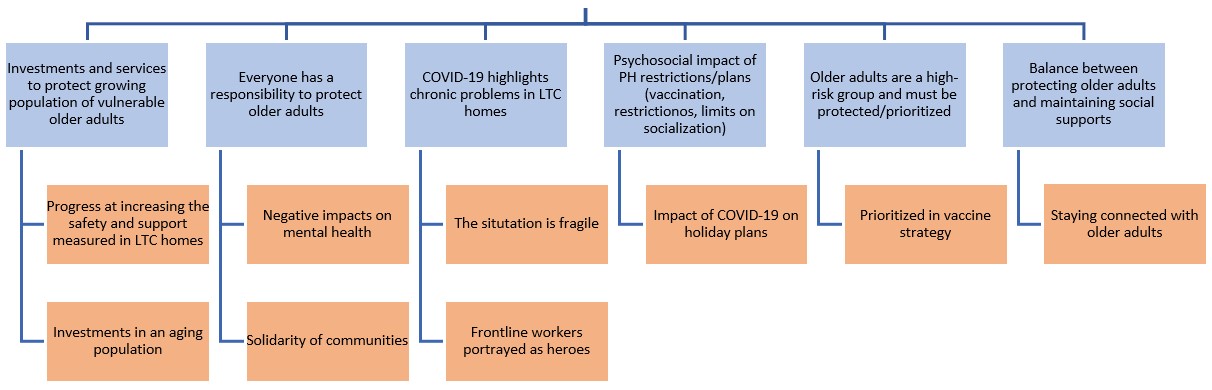

The analysis of 32 press briefings revealed 6 main themes and 9 subthemes. Figure 10 depicts the main themes and subthemes for the press briefings. The main themes are shown in blue, with subthemes shown underneath in orange.

Figure 10 – Text version

The following themes and subthemes emerged from the press briefings:

- investment and services to protect growing population of vulnerable older adults:

- progress at increasing the safety and support measured in LTC homes

- investments in an aging population

- everyone has a responsibility to protect older adults:

- negative impacts on mental health

- solidarity of communities

- COVID-19 highlights chronic problems in LTC homes:

- the situation is fragile

- frontline workers portrayed as heroes

- psychosocial impact of PH restrictions or plans (vaccination, restrictions, limits on socialization):

- impact of COVID-19 on holiday plans

- older adults are a high-risk group and must be protected or prioritized:

- prioritized in vaccine strategy

- balance between protecting older adults and maintaing social supports:

- staying connected with older adults

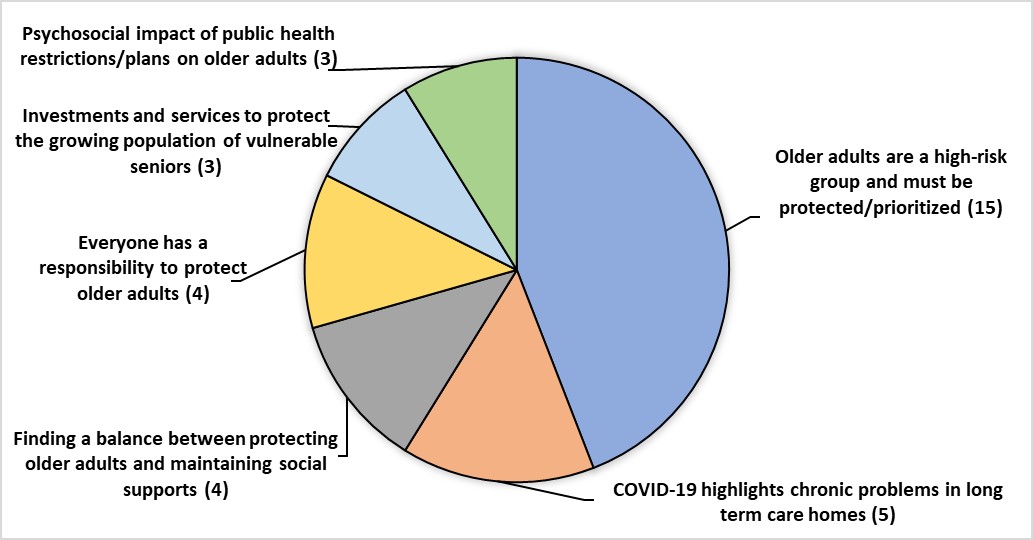

Main themes are shown in Figure 11 below. The most salient theme, which appeared in 15 press briefings, was the presentation of older adults as a high-risk group which must be protected and prioritized. Other main themes are presented in Figure 11.

Figure 11 – Text version

| Government communications: Press briefing themes | Number of articles | Proportion of articles |

| Older adults are a high-risk group and must be protected or prioritized | 15 | 44% |

| COVID-19 highlights chronic problems in long term care homes | 5 | 15% |

| Finding a balance between protecting older adults and maintain social supports | 4 | 12% |

| Everyone has a responsibility to protect older adults | 4 | 12% |

| Investments and services to protect the growing population of vulnerable seniors | 3 | 9% |

| Psychosocial impact of public health restrictions or plans on older adults | 3 | 9% |

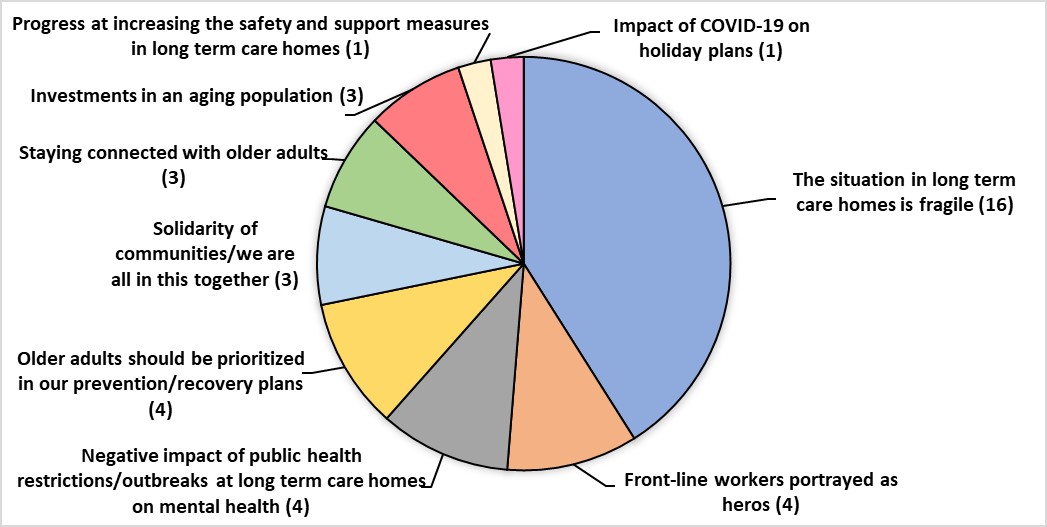

Subthemes: Press briefings

Nine subthemes were identified in the analysis of the press briefings. The predominant subtheme, which appeared in 16 (of the 32) press briefings, was the focus on the fragility of the situation in long term care homes. The other subthemes are illustrated in Figure 12.

Figure 12 – Text version

| Government communications: Press briefing subthemes | Number of articles | Proportion of articles |

| The situation in long term care homes is fragile | 16 | 41% |

| Front-line workers portrayed as heros | 4 | 10% |

| Negative impact of public health restrictions or outbreaks at long-term care homes on mental health | 4 | 10% |

| Older adults should be prioritized in our prevention or recovery plans | 4 | 10% |

| Solidarity of communities and we are all in this together | 3 | 8% |

| Staying connected with older adults | 3 | 8% |

| Investments in an aging population | 3 | 8% |

| Progress at increasing the safety and support measures in long term care homes | 1 | 3% |

| Impact of COVID-19 on holiday plans | 1 | 3% |

Main arguments: Press briefings

The bulleted list below shows the main arguments identified through the analysis of the 32 press briefings. Two arguments stood out from the others, as they were evident in the majority of the press briefings. The first is the need to protect and prioritize older adults who are vulnerable. The second is the need for a careful and cautious approach to ensure safety and quality of life in long term care. Other main arguments in the press briefings are detailed in the list below.

- Need to protect and prioritize older adults who are vulnerable: 15

- Careful and cautious approach to ensure safety and quality of life (visitation, social support, testing) in long-term care homes: 9

- We all need to follow public health guidelines (that is, reducing social contact with older adults) and adjust to changes: 3

- We are all responsible for protecting older adults who are vulnerable: 2

- We need to make investments in the long-term care sector and programs to meet the needs of older adults: 2

- Older adults should be celebrated for the ways that they contribute to our society: 1

Is ageism being discussed or criticized as an issue (in an implicit or explicit way): Press briefings

The analysis revealed ageism was criticized as an issue implicitly in 6 of the 32 press briefings. The first 2 quotations below are examples of this implicit discussion indicating long term care is failing to meet basic standards. The third and fourth quotations set out below are related to calls for change.

Implicit

“Are you going to bring back the idea of having a national standard in [LTC] facilities?”… “No Canadian wants to see their loved ones not well-cared for. I don't think […] some of the regions should offer better or worse protection to elders than others and now is the time to have conversations between the federal government and the provinces on establishing norms for long term care across the country so that all Canadians can be reassured we will take care of elders who deserve the very best from all of us.”

“We have 2 new healthcare outbreaks as well at the [LTC home] and [LTC home] and 2 which are not over, including at the [LTC home]. We know how challenging that outbreak has been and we want to do everything we can to make sure that never happens again.”

“25 million dollars to community groups that deliver mental health and addiction recovery services, many of these groups specialize in helping people with unique needs in our society including seniors, homeless families and Indigenous people and others who may be suffering due to the pandemic and the economic crisis.”

“We've seen over the past many months far too many terrible tragedies in seniors' residences. We need to do better.”

Does the document contribute to ageism, that is, reflects ageist attitudes (implicitly or explicitly): Press briefings

In the press briefings, there were 3 implicit examples of discourse that contributes to ageism (or reflects ageist attitudes). In the first example, the discourse suggests that if society does not protect older adults, they will become a burden and take away the capacity of the system to care for others later. The implication is that protecting older adults now will prevent further burden on our healthcare system.

“Our only protection from COVID-19 is each other and we all share the responsibility of protecting our communities and our fellow [citizens]. The second reason that this approach is not right for [this province] is that death from COVID-19 is not the only severe outcome in [this province] over the past 6 months. One in every 67 people between the ages of 20 and 39 diagnosed with COVID has needed hospital care. That rises to 1 in 18 for those aged 40 to 69 and 1 in 4 for those aged 70 and over. If we let the virus spread freely our health system could be overloaded and caring for other patients which would challenge our ability to provide all the other health services that we need. Babies are still being born, car crashes are still occurring and our health system still must support [citizens] in countless other ways.”

The discourse in the second example emphasizes protecting older adults, which implies that this age group is homogenous and needs protecting; it does not acknowledge that older adults have assets that support resilience.

“The elderly, particularly those with underlying health conditions, are at grave risk from the COVID-19 virus,” [they] said. “We will maintain our vigilance on their behalf.”

In the third example, the speaker differentiates between ‘being healthy’ (and therefore not at risk) and ‘others’ who live with functional limitations due to health conditions. This is an example of both ‘othering’ and ‘ableism’, and reflects a deficit-oriented attitudeFootnote 12 toward others who are in the same age category, based on their functional ability.

“When you look at the 216 deaths that we've had up until now, 90% of the people were 70 years of age and over and 9% were between 60 and 69 years of age. That means that 99% of those deaths are people of 60 years of age and over, so that does mean on the one hand that it's reassuring for the younger people, but obviously it also shows us where we have to put our attention, that is we have to put our attention on the older people. I include myself in that because I'm 62 and, however that is good news, that's what I'm being told. Those people who die between 60 and 69 years of age, almost all of those people had chronic illnesses so that means that if you are in good health as I am, between 60 and 69 years of age there's no reason to worry.”

Are there references to specific chronological age (or age range): Press briefings

Of the 32 press briefings we reviewed, 11 made references to specific age groups. The following table shows the age groups used.

| Reference to age | Number of press briefings |

| 60 and over | 5 |

| 65 and over | 1 |

| In the 70s | 1 |

| 70 and over | 3 |

| 80 and over | 1 |

How is aging, as a process, described or referred to (loss; gain; both; neither): Press briefings

Within the press briefings analyzed, the aging process was described in different ways. The majority of the press briefings (25 out of 32) framed aging in terms of loss only, with references to older adults as having many health risks and needing protection. Six press briefings used neither the loss nor gain frames to describe the aging process, 1 referred to both losses and gains, and none of the press briefings referred to the aging process solely in terms of gains. Two examples below show how aging is framed primarily in terms of loss.

“We're facing an ageing population - a population that has more needs and more requirements and we're really just at the very very beginning of an ageing population which will go on for a number of decades so we are looking at how we can reform long term care”

“We'll take into consideration also the age of the population, as I said before 99% of the deaths we had already are all people over 60 years old, so of course it's different when you talk about being close to somebody older and somebody younger. So it's all the kind of discussion we hope soon to be able to present a plan of reopening with different sectors”

Are there references to older adults’ contribution (s) to society: Press briefings

In the analysis of the 32 press briefings, older adults were mostly viewed through a deficit-lens, with few (n=4) acknowledgements of their contributions to society. In the press briefings where there was an acknowledgement of the contributions of older adults, these acknowledgements often referred to past contributions made when people were younger, as exemplified in the first quotation below. The second and third quotations provided are examples of acknowledgement of general or current contributions of older adults (not time-stamped to the past). Instances where the positive contributions of Indigenous Elders were acknowledged were most often in press briefings from the Territories.

“Every Canadian deserves to be safe and that includes the seniors who helped build this country.”

“Elders in our communities are such an essential part of our rural and urban communities as well, but also in the bigger facilities that we do have in [this city]. Making sure they are protected and feel safe which is an extremely important part of eldercare.”

“Older [citizens] are leaders in the province. They are business owners and entrepreneurs, volunteers, mentors, caregivers and have a wealth of knowledge and expertise to share with other generations.” […] “Older [citizens] are the backbone of our communities and make valuable contributions through their work, interests and volunteerism.”

Are challenges or potential costs posed by aging or older adults mentioned: Press briefings

Of the 32 press briefings reviewed, 16 referenced the challenges or potential costs of an aging population. The quotations below show examples of how the press briefings referenced monetary costs for housing and personal protective equipment or resources, a shared responsibility for protecting older adults, and necessary expenses.

“COVID-19 is obviously unbelievably harmful, potentially harmful to people living in long-term care, so we have to continue in a methodical and safe way to take the actions required. It's why we invested $165.4 million in our single site proposal to keep people safe, it's why we integrated long-term care home in our PPE supply chains before anyone else did in Canada, why we have dramatically increased infection control and invested $160 million now in attracting more staff to long-term care, all of this will help us over the next year and potentially longer as we deal with these situations.”

“We've seen over the past many months far too many terrible tragedies in seniors' residences. We need to do better. Through the safe restart agreement, the federal government has already provided $740 million to help provinces and territories address the immediate needs of vulnerable populations like those in long-term care and this week. Deputy PM Freeland presented the fall economic statement in which we are committing up to $1 billion for a safe, long-term care fund. This fund will help provinces and territories and carry out infection prevention, improve ventilation and hire staff or top-up existing employees' wages. We are ready to keep doing our part of seniors and for all Canadians.”

“Even if we could perfect protections in place for those who live in congregate settings like long-term care while letting the virus spread freely elsewhere, we cannot simply dictate where and how the virus will spread. The more community transmission that we see the greater the risk of it spreading to older and at-risk [citizens]. In [this province], about 30% of those over 80 who have been diagnosed with COVID-19 and who live in long-term care have died. For those over 80 living in the community it is a bit lower but still very high. The lives of people with chronic conditions and our elders are very important.”

“Donc pour aller voir exactement si la situation est sous contrôle il faut revenir sur la situation dans les CHSLD et les résidences pour aînés de façon générale. D'abord c'est important de se rappeler qu'avant même la crise, depuis des années, on avait des pénuries de personnel dans les résidences pour aînés. On avait, je pense, peut-être le problème le plus important sur un problème de salaires donc on n'arrive pas même si on a affiché beaucoup de postes à combler les postes c'est encore plus difficile dans certaines résidences privées qui payent moins cher mais même dans un secteur public très difficile d'aller attirer tout le personnel.”

Translation: [So, to see whether the situation is really under control, we need to review the situation in CHSLDs and seniors' residences as a whole. First of all, it is important to remember that, even before the crisis, seniors' residences had been short-staffed for many years. Perhaps the biggest problem was related to wages. Therefore, we were unable to hire, although we advertised many vacant positions. The situation is even worse in some private residences that pay less, but attracting staff is a challenge even for the public sector.]

How are older adults positioned in regards to other groups: Press briefings

The analysis examined how older adults are positioned in relation to other age groups. Of the 32 press briefings analyzed, 22 positioned older adults against younger generations, or made comparisons between them. The comparisons included positioning older adults as ‘at-risk or vulnerable’, younger populations as having responsibility for or towards older adults, and in some cases grouping older adults with children. The following quotations are examples from the articles that positioned older adults in relation to younger age groups.

“We know that people who are over the age of 80 are more likely to have severe illness or to die from COVID.”

“This is just a reflection of high transmission rates in the community. No one intentionally wants to take COVID into these facilities but staff [and] visitors can unintentionally bring it in because you may not be symptomatic for up to 2 days before but you’re still infectious and with all the layers of protection most use and other layers, you may still inadvertently introduce COVID. So we really need to protect our most vulnerable, especially in long-term care facilities, personal care homes but also people living independently who are our parents and grandparents. Be extra cautious if you do need to visit to assist them with something.”

“If there is a child that is living 1 or 2 in a home and they need help for example or an elderly family member that needs help, what we're asking you to do is to keep that help coming from 1 household.”

“Because as soon as you contact someone with COVID-19 and you have it, you want to go home and hurt your children? I don't know anyone who wants to hurt their children or parents or grandparents.”

What is the role of older adults during the pandemic (victims; fighters; neither; both): Press briefings