Legislative approach to improving accessibility and removing barriers

Official title: Federal Accessibility Legislation - Technical analysis report

On this page

Participants in the in-person events indirectly addressed this issue at various points throughout their session, while respondents to the online engagement were asked for input on specific issues, including whether the new legislation should be based on a prescriptive approach, an outcome-based approach or a combination of the two.Footnote 4

A majority of comments indicated a preference for a prescriptive approach or a combination of the two approaches. A prescriptive approach was significantly more likely to be favoured among the online engagement respondents who identified as having a disability.

Online engagement

The third section of the online engagement questionnaire asked Canadians about the approach that the legislation should take to improve accessibility and remove barriers.

The preamble noted that accessibility legislation in other jurisdictions has taken one of two broad approaches: “1) a prescriptive approach that sets out specific accessibility requirements in law or 2) an outcome-based approach that identifies desired outcomes and establishes a planning and reporting process that organizations are to follow to achieve those outcomes.” The preamble went on to specify that the two approaches are not mutually exclusive, and so elements of both could be combined. It also included brief descriptions of what legislation based on each approach could look like in practice.

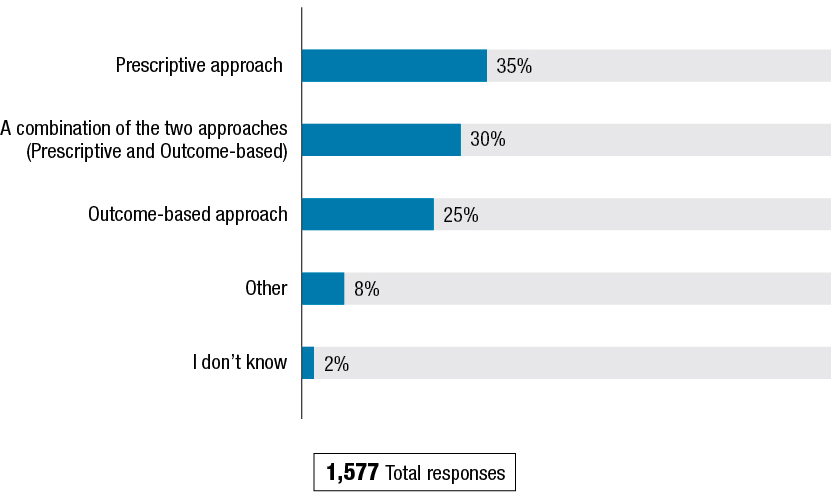

Question: Overall, which approach or approaches do you think would be best for accessibility legislation? Are there other approaches that you would suggest?

This question received a total of 1,577 responses.

As shown in Figure E, a plurality of comments suggested the adoption of a prescriptive approach. About a quarter of comments support an outcome-based approach, while approximately one in three responses indicate a preference for a blended approach.

Text description of Figure E:

| Responses | % |

|---|---|

| Prescriptive approach | 35% |

| A combination of the two approaches (Prescriptive and Outcome-based) | 30% |

| Outcome-based approach | 25% |

| Other | 8% |

| I don't know | 2% |

Sub-group analysis revealed that support for a prescriptive approach was more prevalent in the comments of those who identify as having a disability:

| Approach | Identifies as persons with disabilities | Does not identify as persons with disabilities |

|---|---|---|

| Prescriptive approach | 39% | 31% |

| Outcomes-based approach | 21% | 32% |

| Combination of the two approaches | 29% | 31% |

| Don’t know | 2% | 2% |

| Other | 9% | 4% |

a) Why a prescriptive approach?

Collectively, respondents saw a prescriptive approach to accessibility legislation as having the following advantages relative to an outcome-based model. Such an approach would:

- be more difficult for organizations to ignore or circumvent;

- more clearly and precisely convey what organizations need to do in order to comply;

- make monitoring and enforcement easier by removing some of the subjectivity inherent in measuring the achievement of outcomes;

- make it easier for Persons with Disabilities to understand what to expect from organizations; and

- lend itself to the implementation of consistent national standards.

I'd vote for a prescriptive-type approach. This way, regulations are clear, compliance is easy to determine, and it feels more like a "law" and imperative to organizations under the jurisdiction. In Ontario, where it has been more of an outcome-based approach over many years, it is taking much, much too long. It's unbelievable how incredibly many barriers still exist, and how many employees and company owners are still not even fully aware of their obligations and/or the rights of people with disabilities. My family includes a member with a disability, we live in Ontario, and we continue to encounter barriers every day.

– Anonymous

A prescriptive approach could be best to at least set a minimum standard for provinces and territories. For example, the federal accessibility legislation could state that the legislation applies to businesses of a certain size, demographic makeup or revenue, but provincial/territorial legislation could be used to specify exactly what those numbers/proportions might be.

– Christina Johnson

b) Why an outcome-based approach?

Respondents who recommended the adoption of an outcome-based approach to accessibility legislation felt that it would more likely engender goodwill and enthusiasm from organizations, in contrast to a prescriptive approach, which they viewed as relatively ridged and coercive. It was thought that goodwill would allow organizations to more easily appreciate the business case for accessibility and encourage them to achieve a higher degree of accessibility. Similarly, some people felt that an outcome-based approach was more conducive to spurring innovation, as well as the sharing of best practices and success stories.

The prescriptive approach will encourage businesses to do the minimum and miss the intended purpose. It will not/cannot change culture or mindsets. Outcome-based is a better approach - Executive commitments in accessibility plans (complete with goals, commitments, strategies and results achieved, year over year) should be published publicly (on corporate websites). However, the "stick" approach will not get the desired results. Much better to find ways to get "buy-in" from companies by helping them truly understand why it is good for their business (positive impact on business results) and let them do it their way at their speed.

– Joan Turner, Canadian Business SenseAbility

Overall, an outcome-based approach would be more valuable, as this fosters innovation. A prescriptive approach will require ability for a robust audit process and constant review of standard to ensure it is up to date and reflective of current state.

– Joyce Barlow

Outcome-based would certainly appeal to a positive look at accessibility, with encouragement to participate and reviews as a collaborative, iterative process. It would also open the door for more wide-reaching initiatives to companies and businesses who care, rather than focusing on a baseline legal limit. That being said, the financial burden of that level of staffing and committee oversight would likely form a barrier in implementing this more positive approach.

– Stephen Belyea

c) Why a combination of the two approaches?

Respondents who suggested that the legislation be based on a combined approach believe it would lead to a higher level of accessibility and barrier removal. More specifically, many felt that a prescriptive approach might be better suited for large organizations, especially those that deal with the public. Conversely, the more subjective and flexible nature of an outcome-based approach was viewed as more responsive to the realities of smaller organizations, such as small businesses and non-profit organizations:

Both approaches should be used. We need to consider that ignorance and a lack of motivation could stop the progress of the work in an approach that is exclusively focused on results. Accessibility plans could be superficial. However, even with a prescriptive approach, organizations who want to adopt an original approach that is adapted to their needs should have some flexibility.

– Valérie Martin, PhD student in psychoeducation

d) Other suggested approaches

A total of 147 comments contained one or more suggestions of other approaches. Analysis revealed that these suggestions could be organized into four categories of roughly equal size:

- implement sustained public education and awareness campaigns about the legislation;

- implement effective approaches to monitoring and enforcement (example: including significant fines for non-compliance);

- improve coordination and cooperation between levels of government to ensure greater legislative and regulatory consistency, coherence and clarity across Canada; and

- develop programs to provide funding assistance to help smaller organizations remove barriers and increase accessibility.

Question: If a prescriptive-type approach were to be taken, do you have any input on how standards could be developed?

This question received a total of 1,216 responses.

This question is about process. That is, how to develop standards, as opposed to discussing what the standards should be, or how they could be communicated, monitored and enforced. As shown in Figure F, some people provided comments on the latter issues. The vast majority, however, did provide advice on process.

Text description of Figure F:

| Responses | % |

|---|---|

| The government should consult with the disability community | 43% |

| The government should learn from legislation and practices in other jurisdictions | 20% |

| Provided input on what the standards should include | 18% |

| The government should consult broadly in society | 9% |

| The government has a lot of internal expertise to inform it (e.g., legislators, Office of Disability Issues) | 7% |

| Input on how to ensure compliance | 6% |

| No - do not support a prescriptive approach | 5% |

| No - no input on how standards could be developed | 5% |

| Other | 4% |

| I don't know | 2% |

The most common suggestion was that the Government should keep consulting with Persons with Disabilities and the organizations that represent and advocate for Persons with Disabilities. Many specified that the consultations should be very broad, so as to include an array of disabilities. Others noted that ongoing consultations should also include the family members of Persons with Disabilities and well as other stakeholders (example: social workers, therapists, experts/academics):

Individuals with disabilities and organizations who promote accessibility for those with disabilities should be consulted. This should include perspectives from varying cultures, ethnicities and age groups, as well as a consideration for both physical and mental disabilities.

– Cora Brancato

The second most frequent suggestion was that the development of standards would benefit from lessons learned and best practices drawn from jurisdictions across Canada, as well as around the world. In particular, many of these comments pointed to the ADA as worthy of emulation:

I wouldn't reinvent the wheel and I'm not an expert on the ADA in the United States but as a person with a disability, I have heard that the ADA is a great piece of legislation that should be replicated and improve on where possible. It's one of the few instances I can think of where Canadian legislation can be improved by following the standard set through American legislation.

– Jon Bateman

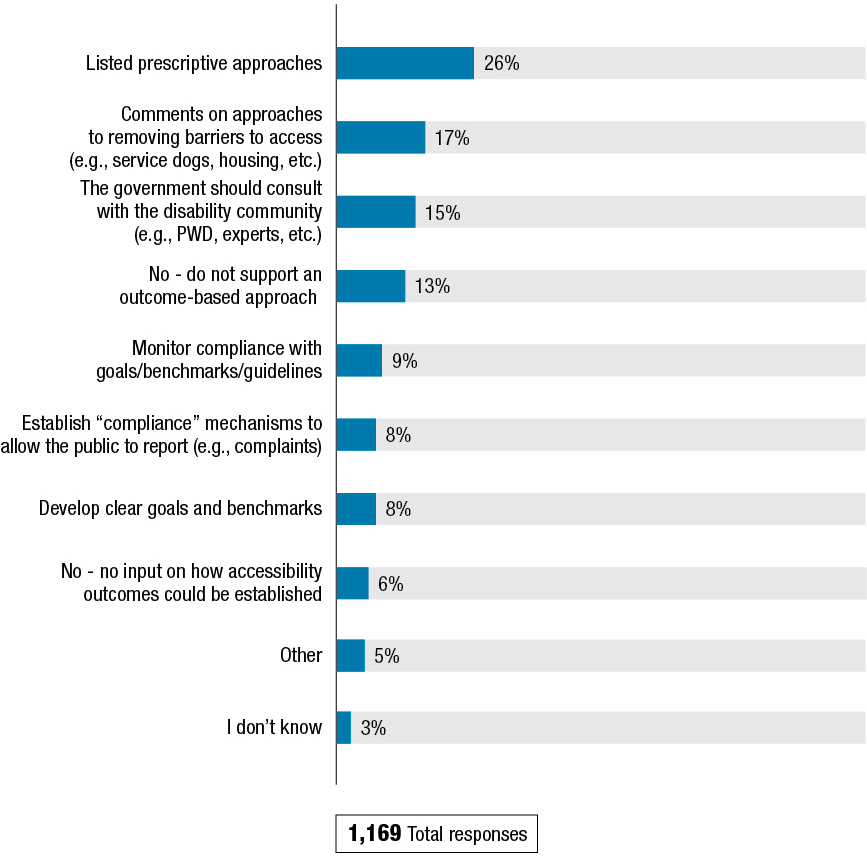

Question: If an outcome-based approach were to be taken, do you have any input on how accessibility outcomes could be established?

This question received a total of 1,169 responses.

Analysis suggests that it was a little more challenging for people to provide input on the establishment of accessibility outcomes than it was to provide advice on the development of standards for a prescriptive approach. As indicated in Figure H, quite a few comments pertained to prescriptive approaches, aspects of monitoring and compliance or the removal of barriers.

The most frequently mentioned suggestion, however, was that accessibility outcomes be determined based on the involvement of Persons with Disabilities, experts in the field and other stakeholders, such as advocacy groups.

Text description of Figure G:

| Responses | % |

|---|---|

| Listed prescriptive approaches | 26% |

| Comments on approaches to removing barriers to access (e.g., service dogs, housing, etc.) | 17% |

| The government should consult with the disability community (e.g., PWD, experts, etc.) | 15% |

| No - do not support an outcome-based approach | 13% |

| Monitor compliance with goals/benchmarks/guidelines | 9% |

| Establish “compliance” mechanisms to allow the public to report (e.g., complaints) | 8% |

| Develop clear goals and benchmarks | 8% |

| No - no input on how accessibility outcomes could be established | 6% |

| Other | 5% |

| I don’t know | 3% |

Public sessions

The most frequently mentioned suggestions for reducing barriers was to ensure that the terminology used in legislation was clearly defined, as well as inclusive of people with “invisible” disabilities. This view was particularly emphasized in Whitehorse, Edmonton and Toronto, with attendees in Toronto suggesting that: “A broad definition of disability is needed to include visible and invisible disabilities. These may be related to aging or episodic illness. Current government definition as ‘severe or prolonged disability’ excludes persons with mental health or episodic disabilities. The experience of pain and physical discomfort that people with episodic disabilities often experience should be brought into the picture when looking at accessibility legislation.”

Another frequently suggested approach for improving accessibility and removing barriers was for government to increase funding for research (example: to identify accessibility needs) and programs (example: to make libraries fully accessible, to provide more and better assistive services such as interpreters). In Halifax, for example, participants lamented the “lack of interpreters for persons who use sign language, especially in the workplace (even federal government workplaces).” Attendees in Toronto echoed these concerns, noting the “… limited availability of timely interpretation services, for example in federal public service, [in turn] limits [the] ability of deaf persons to obtain employment.”

Participants in Regina, Edmonton, Halifax, St. John’s and Toronto suggested that the development of legislation be informed by lessons learned and best practices in other jurisdictions, including internationally.

Other specific suggested approaches were that:

- the Government recognize ASL/LSQ as official languages for deaf individuals;

- the Government ensures that information is provided in accessible formats in all public and transitory spaces (example: accessible airport signage and announcements) in particular;

- the Government adopt for accessibility the type of social/green procurement practices that are in use; and

- social assistance programs be amended to allow Persons with Disabilities to save for the future.

National Youth Forum

The suggestions of National Youth Forum attendees were consistent with those put forward by roundtable participants. Notably, youth called on the Government to recognition ASL/LSQ as official languages. They also suggested that new legislation be informed by best practices within Canada and abroad.

In addition, Youth Forum participants called on governments to improve accommodation in the education system, including debt forgiveness, and for more programs that provide on-the-job training for Persons with Disabilities. Some underlined the importance of programs that would help them make the transition from school thus avoiding or escaping the poverty trap of social assistance (which under current rules does not allow Persons with Disabilities to “put money aside” for future use).

Thematic roundtables

The following two approaches for improving accessibility and removing barriers were discussed frequently in the thematic roundtables:

- Tying public funds to accessibility standards/requirements. Participants in the Calgary roundtable often spoke passionately about this idea, declaring that “any funding coming from federal government needs to have accessibility standards attached to it.”

- Developing legislation that is clear, encompassing of the range of disabilities and which will promote and facilitate the standardization and harmonization of current laws and regulations.

On the latter point, participants in the roundtable discussions in Calgary, Montréal, Saskatoon, St. John’s and Winnipeg added the caveat that the development of common standards should not discourage innovation and creativity: “standards are not the solution for everything. Designing is a creative process - not a checklist; we need to explain what is the goal of each element of CSA so people understand the expectations.” Similarly, participants in Saskatoon and Vancouver advocated for a flexible approach to the introduction of regulations – a “standards-based legislative framework that allows step-wise implementation and evolution over time.”

It was also stressed by attendees in Saskatoon, St. John’s and Winnipeg that though the legislation itself will take time to craft, policies could and should be developed now so that thy will be ready to implement as soon as legislation is enacted.

Stakeholder submissions

Advocacy stakeholders, such as the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada (MS), called for approaches and standards to be developed based on the input from Persons with Disabilities, a view echoed by labour organizations, including the United Steel Workers: “A policy of inclusion must start now. Canadians with disabilities know best what barriers they face to full participation in Canadian life. If the Government is going to implement effective legislation, it is vital that the voices of those Canadians living with disabilities, whether physical, sensory or intellectual be heard.”

Collectively, advocacy organizations also suggested that legislation aim to:

- improve access to employment;

- improve access to income support programs;

- ensure that all government services are fully accessible;

- ensure that no public funds go to organizations that ignore accessibility; and

- improve access to training and education for Persons with Disabilities.

There was also some agreement among advocacy groups, particularly those affiliated with the Canadian Association of the Deaf (CAD), that ASL/LSQ be recognized as official languages. “Have Canada consider these issues as a human rights [issues] to [those who use] ASL and LSQ at home, school and in their social environment as a foundation for life.” Additionally, those same organizations strongly encouraged the investigation of alternate emergency response methods to accommodate those with invisible disabilities. As CAD pointed out, “buildings such as houses, hotels, businesses, apartments, etc. need to be fully accessible by having smoke detectors and fire alarms with strobe lights where Deaf people live and work.”

Industry stakeholders suggested that for new accessibility legislation to be realistic and workable, it should be developed based on the input of industry representatives and other experts, as well as take into account international laws and protocols. As Air Canada indicated: “Others regulations are standards set through the International Air Transportation Association, IATA, and an industry body that facilitates the transfer of passengers and baggage, including the communication of accessible service requirements, from one airline to the next. These are therefore another set of requirements that affect the commercial and operational requirements that airlines are subject to. They too would need to be considered when elaborating new accessible service standards.”

Microsoft provided an example of how international standards could actually contribute to Canada’s approach to improving accessibility and remove barriers: “The legislation should reference international accessibility technical standards. To promote innovation and interoperability, accessibility standards should be consistent from country to country. This harmonization reduces costs to consumers and helps local economies by allowing technology companies to build once and sell worldwide. Several countries, including the US and EU Member States, have harmonized their requirements through the adoption of ETSI EN 301 5491 or the US Section 508 standard2 (which was recently updated to be harmonized with EN 301 549). Canada should harmonize its approach with this emerging international consensus.”

Some labour groups, such as the Canadian Union of Public Employees (CUPE), also called for the reinvigoration of employment equity policies: “reinstate employment equity regulation to its previous standard, and fix gaps in the employment equity system.”