Accessibility issues and barriers: What should the legislation address?

Official title: Federal Accessibility Legislation - Technical analysis report

On this page

Throughout the Consultations, participants shared stories about the barriers faced by people with disabilities. We heard that, while some progress has been made, barriers continue to exist in all areas of life, including attempts to get justice after having experienced discrimination.

The most important areas where accessibility could be improved, as identified by online engagement respondents, are employment, followed by the built environment and transportation. Perhaps more significantly, and discussed below, participants often stressed the need for everyone to understand the interrelatedness of barriers, particularly the interplay between barriers to transportation, education and employment.

Online engagement

The online engagement questionnaire contained a number of questions designed to gather public input on the accessibility issues and barriers that should be the focus of the legislation.

The question preamble explained that the legislation could a) specify the accessibility issues it will address, b) describe a process for identifying these issues or c) use some combination of the two. In terms of potential issues, it listed the following for consideration:

- the built environment

- program and service delivery

- the procurement of goods and services

- employment

- transportation, and

- information and communications

With respect to processes that could be included in legislation for identifying issues and barriers, the following two examples were provided:

- Advisory Council—the Government of Canada could create and support a permanent advisory committee comprised of Canadians with disabilities and other stakeholders.

- Consultations—the Government of Canada could consult periodically with Canadians with disabilities and other stakeholders.

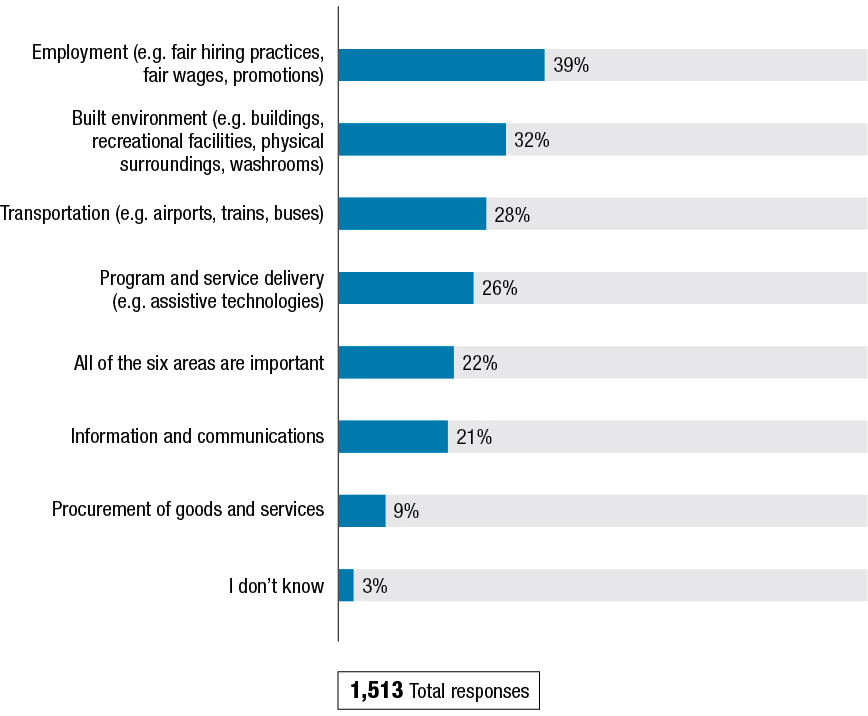

Question: We have listed six areas where accessibility could be improved. Of these, which are the most important to you? Are there other areas that should be included?

This question received a total of 1,513 responses.

As shown in Figure K, about one in five comments indicated that the six areas listed in the preamble are equally important, with quite a few people explaining that they were uncomfortable with the idea of “prioritizing” issues and barriers:

It is problematic to prioritize these areas because doing so pits certain groups of disabled people against others (example: built environment is a priority for those using wheelchairs, while information is a priority for those who are Hard of Hearing). This question essentially asks people which kinds of people with disabilities should be prioritized, which I do not believe should be a question we should be asking. I believe we are better off to prioritize aspects within each of these categories, as often access in one area won't work without access in many of the others (example: accessible program delivery requires accessible built environment, communication, and often transportation to function accessibly).

– Dr. Danielle Peers, University of Alberta

All of the other comments did identify one or two areas as being most important. Employment was the area most often selected, followed closely by the built environment and transportation. People saw employment as important because it would provide Persons with Disabilities with financial security which would remove barriers in other areas and increase their overall independence. Similarly, access to transportation and housing were generally seen as key to getting and keeping a job. Indeed, analysis revealed that people tend to see these three issues as tightly interconnected:

Employment is the key element that will help people with disabilities live. Transportation allows people to get to their jobs and public/private services.

– Anonymous

Built environment and transportation are most important as they influence the rest (if you cannot use the metro you cannot get to work).

– Anonymous

Text description of Figure K:

| Responses | % |

|---|---|

| Employment (e.g., fair hiring practices, faire wages, promotions) | 39% |

| Build environment (e.g., buildings, recreational facilities, physical surroundings, washrooms) | 32% |

| Transportation (e.g., airports, trains, buses) | 28% |

| Program and service delivery (e.g., assistive technologies) | 26% |

| All of the six areas are important | 22% |

| Information and communications | 21% |

| Procurement of goods and services | 9% |

| I don’t know | 3% |

Sub-group analysis showed that transportation was more likely to be identified as most important in the comments of Quebec respondents.

A total 389 comments included suggestions for other areas that could be included. In some cases, people reiterated the importance of one of the six issues identified in the preamble. In other instances, they highlighted a particular facet of an area (for example, the need for more affordable/geared to income housing, which is an aspect of “the built environment”). Other suggestions included:

- promotion of awareness and understanding, which includes “educating” the public, as well as employers, and organizations that serve the public

- health care, which includes better access to therapies and treatments (example: Autism)

- financial assistance and support programs for Persons with Disabilities, their families and care providers

- wellness and leisure, which includes programs and increased opportunities for recreation, physical activity and social activities

- legal assistance, with the objective of removing the barriers that prevent Persons with Disabilities from ensuring that their rights are respected (example: filing official complaints and following through on these)

- research and development, for example into new technologies that will improve the quality of life and level of participation of Persons with Disabilities; and

- education, which includes better access to education and skills training (example: post-secondary education) for Persons with Disabilities

All are important. Include education, there are too many barriers for people with special needs wishing to get a decent education.

– Anonymous

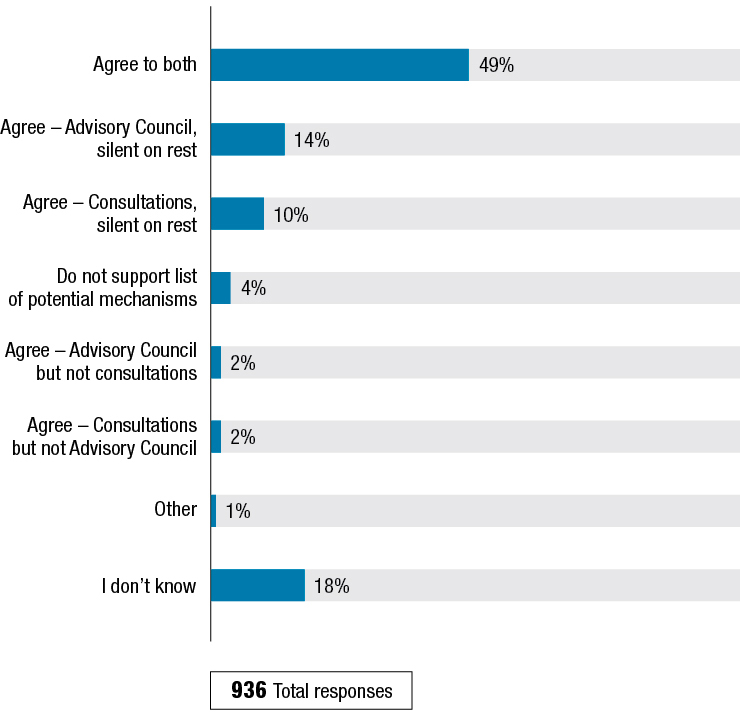

Question: We have listed some potential mechanisms that the legislation could describe for the ongoing identification and prioritization of accessibility issues. What do you think of these mechanisms? Are there other mechanisms you would suggest?

This question received a total of 936 responses.

As shown in Figure L, the most common view, by far, was that both mechanisms should be used for the ongoing identification and prioritization of accessibility issues. The benefits of a permanent advisory council were viewed as:

- higher profile within society and government

- drawing on expert knowledge and rich experience (example: Persons with Disabilities who are scholars, scientists, legal experts, advocates with strong ties to grassroots organizations), and

- permanence (in contrast to ad hoc approaches)

The virtue of consulting periodically with Canadians with disabilities and other stakeholders was that: in contrast to an advisory council, this mechanism would give voice to “ordinary grassroots” people; and it would provide for a greater diversity of input, as well as allow for much greater numbers of Persons with Disabilities to be engaged.

It is also worth noting that some people suggested the two mechanisms be formally linked (example: the periodic consultations feeding into the work of the advisory council). Similarly, a few suggested that provincial advisory bodies could be tied to a national council.

“I think those are both great things to be created and maintained and very important. I like the idea of a mechanism wherein individuals and disability groups alike can provide reports of issues and receive feedback on this.”

– Cherry Thompson

Text description of Figure L:

| Responses | % |

|---|---|

| Agree to both | 49% |

| Agree – Advisory Council, silent on rest | 14% |

| Agree – Consultations, silent on rest | 10% |

| Do not support list of potential mechanisms | 4% |

| Agree – Advisory Council but not consultations | 2% |

| Agree – Consultations but not Advisory Council | 2% |

| Other | 1% |

| I don’t know | 18% |

Quite a few people included the caveat that any new advisory body should have real influence and “power”; they want to avoid the creation of “another empty committee.” The relatively few comments that rejected both mechanisms centered on this type of concern:

The mechanisms mentioned are already in place in government and have been for some time. Once again, rather than work with what has been put in place a new mechanism is being suggested. Government employees with disabilities are Canadians with disabilities and are already meeting through the Persons with Disabilities Champions and Chairs Committee as well as departmental committees and networks to identify accessibility and barriers issues. Listening to them and hearing them and giving them the respect that they deserve is what should be done...rather than ignoring them again!

– Anonymous

There were only a relative handful of suggestions of other mechanisms for the ongoing identification and prioritization of accessibility issues. Most of these contained encouragement and advice about how to engage Persons with Disabilities, such as holding public forums, conducting surveys and involving family members and caregivers in the process. Some people also took the opportunity to suggest that accessibility and the removal of barriers should be elevated as a priority in Canada, though increased funding and public awareness/education, for example.

Many suggestions revolved around the idea that the advisory council should do more than advise the government—it would have a significant oversight role, with the resources, tools (example: compliance audits) and authority to monitor adherence to the legislation. Quite a few characterized this function as that of an “ombudsperson”:

Too much talking, not enough doing. Spend that money on tangible aid to people with disabilities / toolkits to fight discrimination / ombudspeople.

– Clinical Psychologist Dr. Tanya Spencer

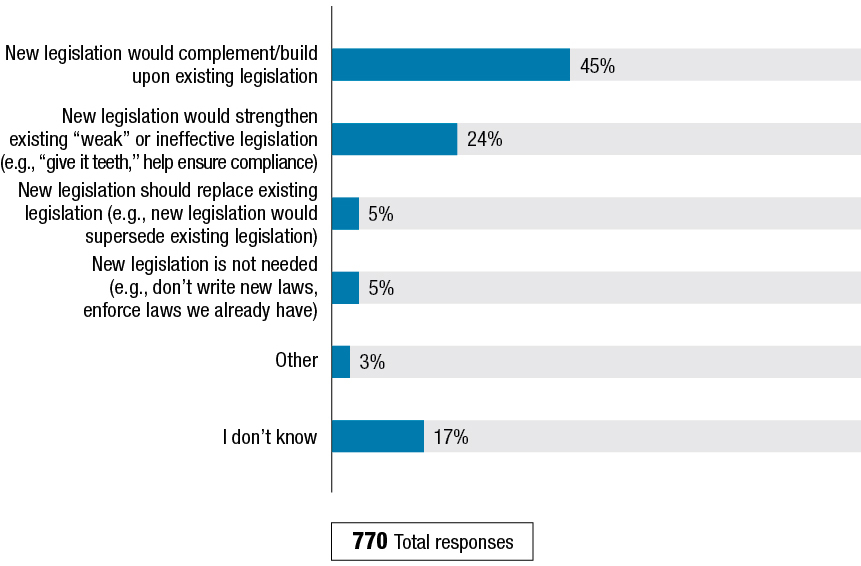

Question: Canada has a number of laws in place to address human rights issues and improve accessibility. Do you have any comments on how the new accessibility legislation could interact with these existing laws? Should the legislation describe a process by which these laws would be reviewed and potentially revised?

a) How Should New Legislation Interact with Existing Laws?

One of the loudest and most frequent refrains coming from those who participated in the online engagement was about their frustration with the current state of legislation in Canada. In their eyes, the lack of an overarching piece of legislation, akin to the U.S.’s ADA, has meant that both Persons with Disabilities, as well as organizations (example: employers, retailers, landlords), have struggled to understand the laws and regulations. Many respondents also lamented what they consider to be a lack of consistency across provinces, a sign to some that accessibility is not a priority in this country (example: because some jurisdictions are free to be less accessible than others). Just as significantly, many comments described the barriers that Persons with Disabilities and their families face in getting redress: the process is too often cumbersome, complex, time-consuming, resource-consuming, energy-draining, intimidating and legalistic.

Going forward, and as summarized in Figure M, respondents would like to see any new legislation address current deficiencies in the legal framework:

We may have laws but enforcement is weak, restitution and reconciliation is not implemented.

– Gael Hepworth

This question received a total of 770 responses.

Text description of Figure M:

| Responses | % |

|---|---|

| New legislation would complement/build upon existing legislation | 45% |

| New legislation would strengthen existing “weak” or ineffective legislation (e.g., “give it teeth,” help ensure compliance) | 24% |

| New legislation should replace existing legislation (e.g., new legislation would supersede existing legislation) | 5% |

| New legislation is not needed (e.g., don’t write new laws, enforce laws we already have) | 5% |

| Other | 3% |

| I don’t know | 17% |

About 4 in 10 comments suggested that new legislation should complement and build on existing legislation in order to avoid duplication, which otherwise would exacerbate the current situation. These respondents also hoped that new legislation would inject a significant measure of coherence and consistency in the legal framework.

I think people will need to understand which law supersedes and or interacts with the other to avoid confusion (example: provincial human rights legislation vs the new federal legislation).

– Anonymous

The new legislation should be written to have quasi-constitutional status such that it takes priority over other legislation (though perhaps not over the Human Rights Act, to ensure that all types of human rights are appropriately balanced where disability rights conflict with other rights).

– Anonymous

About one in five comments expressed a desire for new legislation to be effective at removing barriers and creating access. In their supporting rationale, many described current legislation as “weak,” “lacking teeth” and difficult to enforce, in part because too much of the onus is on the Persons with Disabilities:

The new accessibility legislation must "plug into" all other relevant acts including human rights legislation to ensure enforcement of accessibility as enshrined in those acts. The new accessibility act must have teeth and must ensure that the other acts have teeth as well. Yes there should be a process for revising the other acts and laws.

– Anonymous

b) Should the legislation describe a process by which these laws would be reviewed and potentially revised?

Almost all of the 477 comments (for example about 95%) that expressed a view on whether or not the legislation should describe a process by which accessibility-related laws would be reviewed and potentially revised felt that it should. Analysis suggested that people viewed the periodic review of legislation as common sense, in that laws should always continue to reflect society’s values, as well as technological evolution:

Yes, I agree that the legislation should describe a process which could lead to potential revisions. I believe that as our country and people change often so should our existing laws. The legislation is there to improve the laws and I think that it becomes a necessary step in an ever-changing country.

– Judith Sharp, NWT Disabilities Council

The few who indicated that the legislation should not describe a process by which accessibility-related laws would be reviewed and potentially revised argued that it would be a distraction; one that would draw attention and resources away from monitoring and enforcing compliance with the laws.

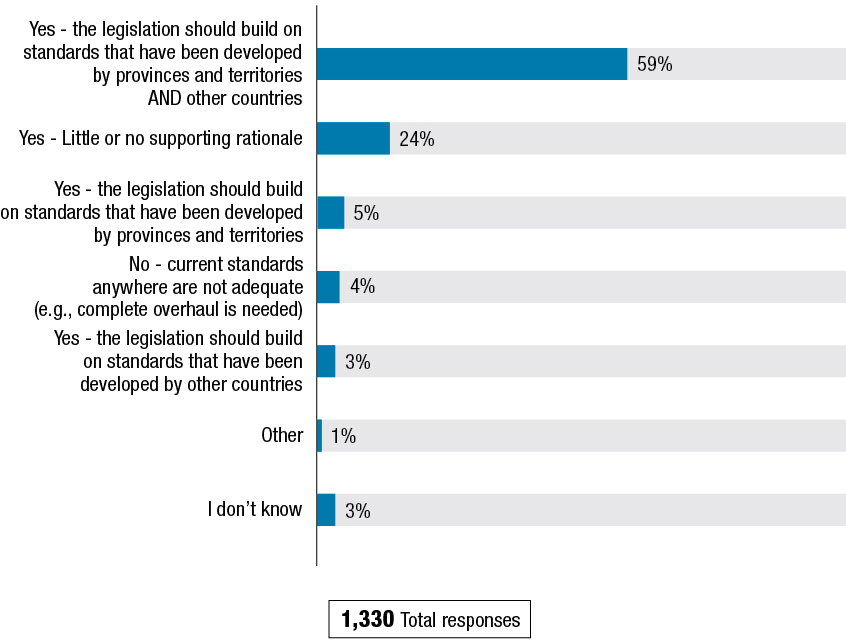

Questions: Should the legislation build on accessibility standards already developed by provincial/territorial governments and other countries?

This question received a total of 1,330 responses.

The results presented in Figure N show consensus that the legislation should build on accessibility standards already developed by provincial/territorial governments and other countries. Collectively, the reasoning behind this view includes that such an approach would:

- help reduce the chances of duplication;

- allow the legislation to be shaped by lessons learned and best practices in other jurisdictions, both within Canada and internationally; and

- increase the possibility that the legislation will be able to provide an overarching coherence and clarity to the other parts of the Canadian accessibility-related legislative framework.

Text description of Figure N:

| Responses | % |

|---|---|

| Yes - the legislation should build on standards that have been developed by provinces and territories AND other countries | 59% |

| Yes - Little or no supporting rationale | 24% |

| Yes - the legislation should build on standards that have been developed by provinces and territories | 5% |

| No - current standards anywhere are not adequate (e.g., complete overhaul is needed) | 4% |

| Yes - the legislation should build on standards that have been developed by other countries | 3% |

| Other | 1% |

| I don't know | 3% |

As part of their comments, a number of respondents suggested legislation and jurisdiction that they felt were worth studying, notably the ADA:

Yes. I've already stated that the programs developed in Japan and some in the U.S.A. provide models for replication. Our organization is the Ontario International Affiliate of Very Special Arts International. The program was originally developed by Jean Kennedy Smith (JFK's sister) to provide access to the arts in the educational/primary school system in the United States. The program is the flip side of the Special Olympics developed by the other sister, Eunice Kennedy Shriver. The ADA has a section which states that access to the arts is a "right" not a privilege. I would like Canada to include that in the legislation or act. Art is about culture and our identity is determined by our culture which is determined by our arts.

– Ellen Anderson, Creative Spirit Art Centre

Public sessions

Collectively, the participants in the public sessions identified the following issues as major barriers to accessibility in Canada:

Lack of accessible transit and transportation, including local and inter-provincial transportation: “Inadequate accessible transportation limits participation in every area of life.” A number of participants also noted accessible transportation is “cross-linked to employment.”

Poverty/income insecurity: Many felt that legislation and policies needed to address the fact that Persons with Disabilities are much more likely to live in poverty than other Canadians: “Because of limited income, education and employment opportunities, many people with disabilities live in poverty and isolation.” Potential remedies included better access to safe and affordable housing, better access to training and education, and better access to jobs: “Ensure that recruitment processes are inclusive and accessible for Persons with Disabilities. Employment accessibility should be in the Act. Companies should have diversity and inclusion plans.” Some participants also called for stronger income support.

Program and service delivery: Over half of public sessions included a request that the provision of accessible information services, including digital information and media content, be improved. Some people noted that certain government services that are offered digitally remain inaccessible. As a participant from Calgary noted: “For those whose first language is ASL, websites (example: federal government service websites) can be very frustrating to access.” This issue was seen as particularly important because of the potential for digital technology to remove many barriers: “The internet could be a great equalizer but national companies should be held to account and digital assets need to be accessible.

”Discussion of programs and services also included improved health coverage (example: for medical cannabis, mobility assistance), child care and legal service (example: the sometimes prohibitive cost of pursuing redress).

Inconsistent regulations (example: building codes) from region to region: This issue was discussed in a number of sessions. Participants indicated that the lack of standardization in areas like lodging/accommodations and transportation can greatly impede freedom of movement of Persons with Disabilities.

Challenges faced by Indigenous Persons with Disabilities and Persons with Disabilities living in remote communities: Many participants across a number of sessions, notably in Regina, Edmonton, Moncton, Ottawa and Toronto, suggested that legislation and the Government’s accessibility policies and programs should address the urgent needs of Indigenous Persons with Disabilities and of Persons with Disabilities living in remote/northern communities. According to a participant in the Whitehorse session: “… the situation is dire for people living with disabilities in the North, in many communities, particularly outside Whitehorse, accessibility is grossly inadequate.”

National Youth Forum

Like most others who participated in the Consultations, the National Youth Forum attendees were eager to see invisible disabilities recognized in the legislation.

Barriers to education and employment, and the interplay between the two, were also highlighted during the Forum. Barriers to education were not only linked to reduced access to employment (and independence), but also as hindering the ability of Persons with Disabilities to take community leadership roles.

Participants noted that their opportunities to become leaders were limited by attitudinal barriers. That is, the view held by some people that Persons with Disabilities are “not up to the task” because they lack the necessary skills, education or other attributes. Facing such attitudes on a regular basis was said to undermine a young person’s confidence.

In terms of potential approaches for removing barriers to assuming leadership positions and securing rewarding employment, it was suggested that governments make education more accessible by making it more affordable (example: scholarships, debt forgiveness). They also placed a great deal of value on opportunities to attend conferences, workshops, forums and other events that allowed young Persons with Disabilities to network, make contacts, learn from each other, hone their presentation skills and, ultimately, build confidence.

Thematic roundtables

Participants in the roundtables identified a number of specific barriers to accessibility in areas such as transportation (both local transit and inter-city transportation), education/skills development, employment, programs and services (example: access to interpreters, child care) and the built environment (example: access to washrooms).

In addition to listing barriers, attendees often highlighted the inter relationship between areas, such as education, employment and transportation, and how barriers in one aspect of a Person with Disabilities’ life can negatively impact one or more of the others. In other words, the chain of accessibility can only ever be as strong as its weakest link: “Current service levels are inadequate to meet demand. It is not possible to improve access to employment, education or sports and recreation if you can’t get people there.” This way of looking at the interplay of barriers illustrates the need for taking a “holistic” approach to improving accessibility.

In addition to identifying areas of focus for new legislation, participants reiterated the importance of making the legislation as encompassing as possible: “People with hidden disabilities are often left behind in discussions about accessibility and are among the most marginalized.” They also emphasized the need for clarity; as one participant in Calgary explained, “We have enough knowledge to arrive at good standards but need to be laid out in clear language. For example, the original Ontario Disability Act called for barrier-free, but not clear what that meant.”

Stakeholder submissions

There was a strong consensus among advocacy groups, such as the Multiple Sclerosis Society of Canada (MS) and the Deaf Literacy Initiative, that the legislation should include clear definitions of terms to protect all Canadians with disabilities, including those with invisible disabilities.

A large portion of organizations also recommended that communications, transit and the built environment be specifically addressed. As MS stated, “Although the nationally regulated systems such as air and train travel are usually manageable, daily travel on municipally run transit systems can be very challenging in and between many cities across the country.”

The notion of inconsistency in monitoring and enforcement was highlighted in CUPE’s call on the Government to “improve and enforce standards for closed captioning, access to technology and other programming and supports for Persons with Disabilities, evenly across all broadcasting and telecommunications platforms,” due to what it described as a lack of enforcement of existing regulations.

Industry stakeholders largely maintained that existing regulatory frameworks were adequate but lacked the necessary incentives or enforcement. Air Canada, for instance, felt that the Canadian Transportation Agency’s current framework works well for everyone: “In its analyses, the Agency balances the rights of passengers to travel without undue obstacle to their mobility, with the airlines’ commercial, operational and technical requirements. Significant effort and discussion has gone into the development of this body of case law, standard-setting guidelines and codes of conduct.”

The Canadian Bankers Association’s proposal that federal accessibility legislation take into account already existing standards and practices:

Federal accessibility legislation that proposes measures that differ significantly from existing procedures and practices used by institutions or required under the AODA or other provincial accessibility legislation would be problematic from an implementation perspective and create a patchwork of accessibility standards across the country. Further, federal accessibility standards should take into consideration existing, widely-accepted standards and practices (for example particularly in respect of technology standards such as the Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG)). Finally, accessibility laws in other jurisdictions should be considered to avoid conflicting and contrasting standards.

– Canadian Bankers Association Submission