Building a Modern 21st Century Workforce – Discussion Paper

On this page

- Message from the Minister

- Introduction

- Section 1: Labour market trends and key drivers of change

- Section 2: Aligning workforce development strategies with changing economic priorities in emerging and growth areas

- Section 3: A snapshot of Canada’s skills development landscape

- Section 4: Moving forward—opportunities to foster a modern, diverse, inclusive and productive 21st century labour market

- Conclusion

- Tell us what you think

Alternate formats

Building a Modern 21st Century Workforce – Discussion Paper [PDF - 2.48 MB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

Message from the Minister

Canadians deserve to benefit from meaningful and rewarding jobs that provide for a good quality of life. Major shifts are restructuring our economy and driving changes for workers and employers. This creates an opportunity to develop new strategies and take actions for our country and its workforce to thrive.

This discussion paper will open a dialogue on how to build on our strengths, address challenges and seize opportunities. Our dialogue will help identify ways to foster greater inclusion and productivity. It will help better prepare Canadians for success today and tomorrow in areas of economic growth in a green, digital, and modern economy.

The valuable input received will inform concrete areas of action for skills development, training support, and lifelong learning. I encourage you to share your thoughts on how to continue building a strong and inclusive 21st century workforce. Together, we can create a bright future for Canada.

The Honourable Randy Boissonnault

Minister of Employment, Workforce Development and Official Languages

Introduction

Canada has a skilled and well-educated labour force, underpinned by robust education, training and employment supports. Emerging trends and societal changes demand that we reflect on what works and what can be improved to build a more productive and inclusive workforce. These forces require new strategies to drive economic growth and labour productivity to help position Canadians to benefit from good, sustainable jobs and a better quality of life. Public, private and not-for-profit organizations must be agile and responsive and work together to meet workers’ and employers’ evolving needs. This will help position Canada as a world leader in fostering a modern, 21st century labour market ready to advance economic priorities and build a digital and green economy.

This paper aims to gather diverse views from across the country and open dialogue on how to build on our strengths, address challenges and seize opportunities. It provides an overview of the current labour market context and major trends, a snapshot of Canada’s skills development landscape and ways to foster greater inclusion and productivity.

Section 1: Labour market trends and key drivers of change

The Canadian economic context and labour productivity

Canada has strong fundamentals, but the outlook for growth remains modest

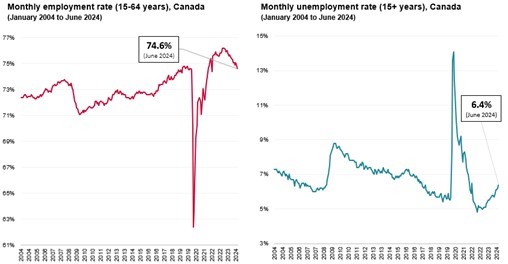

Text description for Figure 1

The line graph shows that the employment rate for Canadians aged 15 to 64 was 74.6% in June of 2024 while the unemployment rate for Canadians aged 15+ was 6.4% in June of 2024

Overall, Canada’s economy is healthy, based on most indicators. With one of the fastest employment recoveries in the G7 after the COVID-19 pandemic, total employment in Canada reached 20.5 million in June 2024, a rise of 1.3 million compared to February 2020. Canada avoided the recession expected by private sector forecasters, with real gross domestic product (GDP) rising by 1.1% in 2023, over 3 times higher than forecasted. Going forward, Canadian economic growth is expected to be lower than during the years before the pandemic (which averaged 2.1% from 2014 to 2019). The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) projects Canada’s GDP will grow by 1.0% in 2024 and 1.8% in 2025.

Canada is recognized as a good place to invest and grow, because of its talent, abundant natural resources and preferential access to markets around the globe. In the first 3 quarters of 2023, Canada had the highest level of foreign direct investment (FDI) on a per capita basis among G7 countries, and ranked third globally in total FDI, after the United States and Brazil. Canada is also viewed favourably in terms of market access, with 15 free trade agreements covering 51 countries and 1.5 billion consumers worldwide. However, geopolitical risks and the rise of trade protectionism on a global scale are cause for concern.

The cost of living remains a challenge. Canada’s inflation has decreased significantly from its peak (8.1%) in June 2022. The Bank of Canada projects that inflation will ease below 2.5% in the second half of the year and return to target in 2025. Average hourly wage growth has surpassed inflation for the past 15 months (+4.7% year over year in April 2024). This follows a period of low wage increases where Canadians’ purchasing power declined as real wage growth was negative due to high inflation. Moreover, workers are expected to see more modest wage increases in the years to come.

Lagging labour productivity is a worrisome trend in a global economy undergoing significant changes

Canada’s lagging productivity affects many sectors. One trend that continues to give cause for concern is that Canada is lagging in terms of labour productivity (measured as GDP per hour worked) compared to its peers. While there are several underlying reasons for low labour productivity, since 2000 it is not limited to one or 2 sectors. This trend is primarily due to inefficiencies within sectors rather than between sectors.Footnote 2 Of note, business investment and business investment per worker has been lagging behind the US for decades and the gap has continued to widen since the early 2010s.

Impacts of macroeconomic and labour market trends vary for different groups

Canadians with lower educational attainment and low skills are at greater risk of the impacts of economic shocks with less resiliency. The link between higher levels of education and higher earnings is well documented. The impact of the pandemic reinforced this point. Statistics Canada research found declines in the employment rate during the first months of the pandemic (from February to April 2020) were larger among those aged 25 to 64 with education below the bachelor level (11.7 percentage points), compared with those in the same age group who hold a bachelor’s degree or higher (6.9 percentage points). The employment rates of those with education below the bachelor level did not recover to pre-pandemic levels until fall 2021, compared with late 2020 for those who hold a bachelor’s degree or higher.

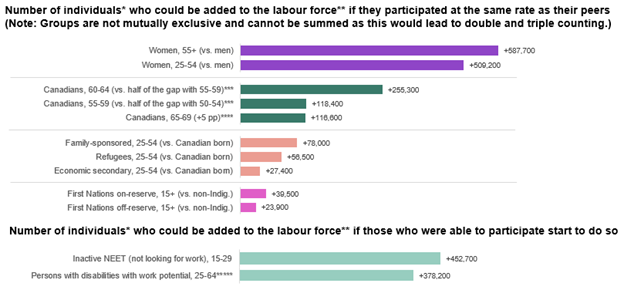

Employment and unemployment rates vary across demographic groups. For Canada’s general working-age population, these remain at historically strong levels, at 74.6% and 6.4% respectively. This differs substantively for some groups. For instance, youth (ages 15 to 24) have experienced rising unemployment rates, which reached 13.5% in June 2024, the highest since September 2016 (excluding the 2020 to 2022 pandemic). While women’s participation rates have risen, the makeup of positions has not. The Canadian Chamber of Commerce found that although women now represent 48% of all jobs in 2023 (a growth of 5% since 1987), they hold only 35% of management positions and 30% of senior management positions. According to Statistics Canada, in 2023, the unemployment rate for the Indigenous population, for all education levels, was 7.7% compared to non-Indigenous population aged 24 to 54 of 4.5%.Footnote 3 Only 62% of working-age adults (aged 25 to 64) with disabilities were employed, compared to 78% of persons without disabilities.Footnote 4 There are many opportunities to increase labour force participation. Given the disproportionate rate of participation of under-represented groups, more work needs to be done. For example, if women 55+ participated at the same rate as their men counterparts, this could potentially add over 500,000 people to the labour force.

Text description for Figure 2

The first 10 data points in the bar graph show the number of individuals* who could be added to the labour force** if participated at the same rate as their peers. Note: groups are not mutually exclusive and cannot be summed as this would lead to double and triple counting.

- Women aged 55+ (versus men) could add 587,700

- Women aged 25 to 54 (versus men) could add 509,200

- Canadians aged 60 to 64 (versus half of the gap with 55 to 59)*** could add 255,300

- Canadians aged 55 to 59 (versus half of the gap with 50 to 54)*** could add 118,400

- Canadians aged 65 to 69 (plus 5 percentage points)**** could add 116,600

- Family-sponsored immigrants aged 25 to 54 (versus Canadian born) could add 78,000

- Refugees aged 25 to 54 (versus Canadian born) could add 56,500

- Economic immigrants – secondary applicants aged 25 to 54 (versus non Indigenous) could add 27,400

- First Nations living on-reserve 15+ (versus non-Indigenous) could add 39,500

- First Nations living off-reserve 15+ (versus non-Indigenous) could add 23,900

The last 2 data points in the bar graph show the number of individuals* who could be added to the labour force** if those who were able to participate started to do so.

- Inactive individuals not in employment, education or training aged 15 to 29 could add 452,700

- Persons with disabilities with work potential aged 25 to 64***** could add 378,200

While racialized individuals are more likely to pursue a university education, their employment income is lower than non-racialized and non-Indigenous graduates. According to the 2016 Census, 44% of Canadians aged 25 to 54 belonging to a racialized group had a certificate, diploma or degree at the bachelor level or higher, compared with 27% for non-racialized and non-Indigenous Canadians. Employment income averaged $47,800 and $45,700 for non-racialized and non-Indigenous women and racialized women, respectively, compared with $54,100 and $51,600 for non-racialized and non-Indigenous men and racialized men, respectively.Footnote 7

The labour market is loosening, but specific sectors still have gaps

Canada’s labour market remains tight with persistent gaps in some sectors. Despite some recent easing, Canada’s labour market remains tight and some sectors are unlikely to ever go back to pre-pandemic states. While the number of job vacancies declined to approximately 678,500 in Q4 2023, it remained higher than the average of 542,560 in 2019). In a few sectors, vacancies are still significantly higher than pre-pandemic, such as health care and social assistance (examples include nurses and early childhood educators) and construction. Improving labour mobility between provinces and territories could help to alleviate pressure by enabling workers to move where needed.

Shortages are anticipated to persist in certain occupations. For the 2022–31 period, 56 occupational groups are expected to face shortages, concentrated in health, natural and applied sciences, and trade occupations. These shortages could have negative impacts on the well-being of Canadians. Health care workers will be critical with an aging population and trades workers will be needed to build the required housing supply. Another example is the agriculture sector, which is essential to continue feeding Canadians as the population continues to grow and costs continue to rise.

Recognizing distinct needs in rural and remote communities. In more than 1,800 rural and remote communities in Canada—the majority with populations of 10,000 or less—an average of 30% of the local labour force is dependent on natural resource sectors such as agriculture, forestry, fisheries, energy and mining.Footnote 8 As communities transition from declining sectors to growth areas, as well as advancing climate change adaptations, these communities face unique circumstances to be addressed. As Canada progresses toward a more digital economy, more work needs to be done to close the digital divide. For example, while progress is being made on mobile LTE networks, there is still further to go given differences in coverage on major transportation roads and highways (87.2%), in rural communities (97.1%) and across Canada (99.4%). Access to broadband (at 50/10 Mbps unlimited) poses an even greater challenge for rural communities (62%), which lag behind the rest of Canada (91.4%).Footnote 9

Canada is a global leader in educational outcomes, but skill levels vary

Despite high educational attainment, Canada lags in graduate degrees. When looking at post-secondary education, Canada ranks as the most highly educated country in the world.Footnote 10 In 2021, the percentage of Canadians between the ages of 25 and 64 with a college diploma, university degree or higher was 58% (compared to the OECD average of 41%).

While Canada has a skilled workforce, employers continue to identify gaps. In 2023, 26.1% of businesses surveyed, in the Survey of Employers on Workers’ Skills reported that 20% or more of their employees have skill gaps. Technical, practical or job-specific skills were the most cited as needing improvements, followed by skills related to problem-solving, critical thinking and customer service.

Demographic changes

An aging workforce poses risks while presenting opportunities

Almost one in 4 Canadians is a baby boomer. Many older workers, who are healthier than ever before, are choosing to remain in the labour market. According to Statistics Canada, the participation rate for people over 55 was 37% in 2023, compared to 25% in 1998. Many older workers are happily employed or find fulfillment in their work. Others may continue to work due to increased cost of living or the presence of children still at home. Some may face a challenge of finding appropriate and attractive employment opportunities. Regardless, the supply of labour will decrease as this group exits the labour market. For example, between 2022 and 2031, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC)’s Canadian Occupational Projection System (COPS) projects that there will be more than 1.2 million job openings among Skilled trades in Canada, including 600,000 from retirement. This trend will drive both loss of skills but also opportunities for restructuring labour demand with tighter labour supply.

Millennials are now the largest segment of the Canadian population. Millennials make up 23% of the total population. As approximately a quarter of the population, this has important economic and social considerations.

More can be done to support youth to fully realize their potential

Younger generations have much to offer. The rise in the millennial and Generation Z populations is largely due to the recent arrival of a record number of permanent and temporary immigrants. They are increasingly educated at the post-secondary level, more diverse and more exposed to changing digital technologies than their predecessors. They have much to offer to the benefit of Canadian employers to strengthen innovation, productivity and competitiveness.

Immigration has become the main driver of population and labour force growth

Newcomers are essential to Canada’s workforce. Today, almost one in 4 people is or has been a landed immigrant or permanent resident in Canada. Non-permanent residents represent about 6.5% of the population. However, newcomers are still more likely to be unemployed than Canadian-born adults, even after other factors such as skill levels are considered.Footnote 11 In 2023, the unemployment rate of Canadian-born individuals was 4% while that of newcomers was 8%.

Refugees have worse labour market outcomes. Of all newcomers, in 2021, refugees had the lowest labour force participation and employment rates, as well as the highest unemployment rate. They have the lowest level of employment income of all newcomers, which is lower than the Canadian average. Based on Census 2021 data, their participation, employment and unemployment rates improve significantly over time. Due to these improvements employment income increases, yet 10 years after becoming an immigrant it remains at a relatively low level.

While Canada has made progress in becoming more inclusive, more work remains to remove barriers to maximizing labour market participation

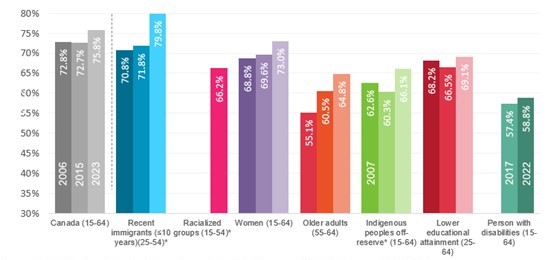

Under-represented groups continue to experience under employment and lower participation rates. For economic growth and social cohesion, maximizing participation of under-represented groups is critical. As an example of missed opportunity that impacts individuals, employers and communities, below is a comparison of employment rates for racialized versus non-racialized groups, and among different groups.

Text description for Figure 3

The bar graph shows the employment rates of specific demographic groups in 2006, 2015 and 2023 where available.

- Canada’s total population aged 15 to 64 had an employment rate of 72.8% in 2006, 72.7% in 2015 and 75.8% in 2023

- Recent immigrants who have been in Canada less than 10 years aged between 25-54 had an employment rate of 70.8% in 2006, 71.8% in 2015 and 79.8% in 2023

- Racialized groups aged 15 to 54 had an employment rate of 66.2% in 2023, data was not available prior to 2023

- Women aged 15 to 64 had an employment rate of 68.8% in 2006, 69.6% in 2015 and 73% in 2023

- Older adults aged 55 to 64 had an employment rate of 55.1% in 2006, 60.5% in 2015 and 64.8% in 2023

- Indigenous Peoples living off-reserve aged 15 to 64 had an employment rate of 62.6% in 2007, 60.3% in 2015 and 66.1% in 2023

- Canadians with lower educational attainment aged 25 to 64 had an employment rate of 68.2% in 2006, 66.5% in 2015 and 69.1% in 2023

- Persons with disabilities aged 15 to 64 had an employment rate of 57.4% in 2017 and 58.8% in 2022, data was not available prior to 2017

While the Indigenous population is growing, employment rates are still lower, and barriers persist. Between 2016 and 2021, the Indigenous population grew by 9.4% compared to the non-Indigenous population (5.3%). However, the employment rate among Indigenous adults was lower compared to the non-Indigenous population, estimated at 61.2% and 74.1% respectively. Educational attainment significantly narrows the gap in employment rate, as those with a bachelor’s degree or higher have similar employment outcomes. Continued efforts are necessary to address and remove employment barriers for Indigenous Peoples and to support their resilience and ongoing progress in the workforce.

There is a continued need for focused attention on removing barriers to employment outcomes for persons with disabilities. In 2022, 1 in 4 Canadians aged 15 years and older had one or more disabilities that limited them in their daily activities. This will increase with an aging society due to the interaction between age and disability. In 2021, 3.2 million persons with disabilities aged 15 to 64 were employed, 2.9 million were adults aged 25 to 64 years and 344,000 were youth (aged 15 to 24).Footnote 14 However, in 2022, over 1 million persons with disabilities aged 15 to 64, have potential for paid employment in an inclusive, accessible and accommodating labour market.

Women are making positive gains, but the pandemic showed labour market risks can disproportionately affect women. According to the Labour Market Information Council (LMIC), initial pandemic-related employment losses were steep for both sexes, totalling 1.52 million (-16.8%) for women and 1.46 million (-14.6%) for men in just 2 months between February and April 2020. Two years after the start of the pandemic, job recovery was fast, with women’s employment (2.9%) slightly outpacing men’s employment (1.9%).Footnote 15 Following the pandemic, nearly 140,000 women left jobs in high-contact sectors, with many seeking roles in low-contact industries (for example, in professional, scientific and technical services and finance, insurance and real estate). This marks a shift from traditionally lower-productive and lower-paying sectors into higher ones. This added $9 billion to household income for women and accounted for 15% of the total boost in their income during the pandemic recovery.

Women also continue to experience lower participation rates and a persistent gender wage gap. Between 2019 and 2023, the participation rate for core-aged women with youngest children under 6 years old increased by 3.8 percentage points to 79.7%, representing over 51,000 additional women joining the labour force. In 2023, if the employment rate of core-aged women (aged 25 to 54) with a child under the age of 6 had been the same in the rest of Canada as in Quebec, 86,500 more women would have been employed. In terms of gender gap in median hourly wage (full-time employees only), women (aged 25 to 54) earned $0.88 for every dollar earned by men of the same age group in 2023.

The 2SLGBTQI+ community also faces unique barriers to employment. Addressing the specific employment and skills development needs of 2SLGBTQI+ workers in Canada can also reduce disparities in a variety of labour market outcomes. Examples include wages, hours worked and occupational segregation, relative to cisgender, heterosexual workers. Discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity is the primary barrier to employment and skill development for 2SLGBTQI+ people in Canada. Trans* and gender-diverse people in particular report very high rates of employment discrimination, alongside structural barriers to employment (for example, having a “dead” [former] name on documentation of credentials or difficulty accessing references for work experience prior to their transition).Footnote 16

While demand for bilingual positions is favourable, employment outcomes for official language minority communities (OLMCs) are misaligned. Following the pandemic, OLMCs experienced a robust recovery. In Q4 2023, there were 14,674 bilingual online job postings in OLMCs, which was slightly above Q1 2020 levels. This suggests that job vacancies are back in line with pre-COVID levels. Moving forward, close to 63,000 businesses expect challenges in recruiting bilingual employees. Compared to the total online job postings across Canada, bilingual job postings in OLMCs usually require higher skill levels (that is, post-secondary education). While demand is positive, unemployment rates of OLMCs suggest more could be done to increase participation. The unemployment rates for Francophones outside Quebec (9.2%) were lower than their Anglophone (11.1%) counterparts. So too were employment (54% vs. 57.4%) and participation rates (59.9% vs. 64.5%) (Census 2021). In Quebec, English-speaking Quebecers have poorer labour market outcomes, with an unemployment rate of 11.0% compared to 6.8% for Francophones.

Technology and the future of work

The experience of change at a scope and pace never seen before is a global phenomenon, with the impacts of new technologies and Industry 5.0 expected to be far-reaching and profound

Canada is not immune to change—rapid technological changes are impacting our economy, labour supply and demand. New technologies have traditionally been enhancing labour productivity and creating new jobs. However, the current pace of change is accelerating, impacting tasks and skills that were previously thought to be immune to automation.

Some occupations are more susceptible to the impact of changes. Overall, the OECD estimates that 45.6% of jobs as a share of total employment are vulnerable to automation in Canada, as some of their tasks could be automated. Of these jobs, 15% are at high risk, as their roles mainly involve tasks that could be easily done by machines. In 2020, Statistics Canada estimated that part-time and low-income workers are more likely to be in occupations at high risk of automation. These impacts are also expected to be gendered as women are more likely to be working part-time and have lower employment income.

Technology can also support an increased focus on worker well-being. With growing technology adoption, there is an emerging interest in putting people at the centre of production and uses of new technologies to improve prosperity beyond jobs and growth. This new approach will require investment and solutions to meet the evolving needs of workers and increase competitiveness in all sectors of the economy.

Investment in new technologies is needed to augment labour productivity

Technology adoption can support job creation and new opportunities. It can enable business to focus on new products and new markets. It can also create opportunities for more meaningful engagement of workers, shifting their days from routine, predictable repetitive tasks to work that enables them to innovate, be creative, solve challenging problems and make more human connections.

With greater adoption by Canadian firms, artificial intelligence (AI) is a transformative technology that can help to improve productivity. Generative AI has the potential to add almost 2% to Canada’s GDP. Despite Canada being a global leader in the development of AI, adoption in the broader Canadian economy is relatively low (estimates range from 4% to 28% of firms)Footnote 17 and, according to Leger (2024), Canadians report that they use AI more in their personal lives than at work. This low adoption means that the full impact of AI on productivity, employment and skills is yet to come.

Employers across most sectors are looking for workers with digital skills more and more. The OECD found that, as more job activities become automated, professional skills that cannot yet be replicated by machines will become more important. An OECD analysis of job postings in Canada also highlighted that the skills most in demand for occupations exposed to AI included management, communication and digital skills. In addition, over the last 10 years, a range of social skills, such as teamwork, collaboration, managing stakeholders, negotiations and team building saw their fastest increase in demand.Footnote 18

Changing business and worker models are propelling the need for a mindset shift and new approaches

The type of work Canadians are doing is changing. New technologies are reshaping the way people work and earn a living, which could increase the offer and the demand for gig work. Statistics Canada reported that, in Q4 of 2022, 871,000 Canadians (aged 15 to 69) had a main job featuring characteristics of gig work. In 2023, close to half a million people worked through a digital platform or application that also paid them for their work. Gig workers can be defined as workers who enter more casual work arrangements, such as short-term contracts, to complete tasks often facilitated by new technologies.

Increased technological adoption may amplify the shift in worker models. With increased AI adoption and automation, the amount of time spent on work could be reduced by 30% by 2030.Footnote 19 If accurate, this may encourage some companies to reduce full-time workers in favour of a combination of specialized gig workers and AI. It could also increase access to e-learning, microlearning and personalized training based on previous experience and skills.

Canada must continue to be an “employer of choice”—domestic and international competition for talent is creating more opportunities for greater worker voice in shaping healthy, productive workplaces

Following the pandemic, mental health is increasingly a priority for workers and employers. In 2023, Statistics Canada found that just over 4.1 million people indicated that they experienced high or very high levels of work-related stress, representing 21.2% of all employed people. The most common causes of work-related stress included a heavy workload, which affected 23.7% of employed people, as well as balancing work and personal life (15.7%). Workplace wellness benefits both employers and workers and can improve productivity, employee satisfaction and retention.

Flexible work arrangements present opportunities for participation, but concerns have been raised about the right to disconnect. In addition, in a December 2023 survey, most job seekers said it is more important to them to have a meaningful job than a high-level job title (85%) and define success through work-life balance as opposed to climbing the corporate ladder (84%). Nearly two-thirds of Canadian job seekers (63%) say they are not interested in “climbing the corporate ladder.”

Employers who are responsible stewards is a value proposition in recruiting talent. In 2023, a survey was conducted in British Columbia to learn more about what young millennials and Generation Z are looking for in the workforce. It revealed that 87% of them prefer to work for socially and environmentally responsible companies, 61% would only work for responsible companies, and 65% would work even harder for companies that are socially and environmentally responsible. The values of young workers may increasingly determine their work choices.

Section 2: Aligning workforce development strategies with changing economic priorities in emerging and growth areas

Preparing Canadians for the jobs and the economy of the future

New global realities necessitate thinking and doing things differently. As Canada advances in becoming a modern, digitally enabled, net-zero economy, aligning skills development and training programs with strategic growth areas is key. Adopting a growth mindset to knowledge and skills acquisition will prepare Canada’s current and future workforce to effectively use new tools and technologies and become more productive while fostering greater inclusivity and efficiency.

Canada is setting economic priorities to guide complementary investments. The Government of Canada’s economic policy aims to build a green, digital and resilient Canadian economy through whole-of-government efforts:

- green transition: enabling the transition to a net-zero economy by investing in Canada’s cleantech sector and helping sectors decarbonize

- digital leadership: advancing Canada’s globally recognized leadership in AI and quantum and supporting sectors to adopt cutting-edge technologies

- economic resilience: building Canada’s capacity in critical areas, such as semiconductors, biotechnologies, critical minerals, sustainable agriculture and strengthening supply chains and linkages with allies

Prioritizing action in these areas is pivotal for strengthening competitiveness. Mutually reinforcing investments in economic development and workforce development will equip Canadian workers to develop the skills needed to innovate and foster resilience.

Canada’s transition to a net-zero economy is creating opportunities for good jobs with promising careers, and supporting workers through transitions is vital

The transition to a sustainable economy is driving demand for new skills. As being observed across all sectors, shifting demand ranges from workers developing the skills needed to meet new business requirements to the creation of new occupations. Over the next 10 to 20 years, up to 400,000 jobs could be added where an enhanced skill set will be critical. New opportunities are already being created in the clean energy and renewable battery industries, and some 46% of new jobs will be in natural resources and agriculture. Also, 40% of those in trades, transport and equipment could require enhanced skills due to the transition to a net-zero economy.Footnote 20 However, new jobs may not be created in communities where carbon-intensive jobs are lost, and northern and remote communities may face distinct hardships given their unique circumstances.

Canada stands to gain by being proactive to seize strategic opportunities. For example, Canada has world-class reserves of critical minerals, ranking first in mining potential in 2022, as determined by global companies in the sector. Businesses in industries critical for the net-zero transition are already making significant investments. Other priority areas in the net-zero economy include electric vehicles, the battery supply chain, renewable energy and carbon capture technologies. Furthermore, in the years to come, there will be declining but continuing use of hydrocarbons in combustion applications, and countries that focus on producing hydrocarbons with ultra-low production emissions will have an edge. It is in this context that aggressively lowering emissions from the production of fossil fuels, in line with Canada’s climate commitments, is both a competitive advantage and a source of sustainable jobs.Footnote 21

A sustainable economy is green and inclusive by design. It will be important to ensure access to a workforce with the skills and knowledge needed to support the green transition. Improving diversity in decarbonizing sectors may play an important role in addressing the skills gap,Footnote 22 and an equity-focused approach is needed to ensure that green jobs are inclusive.Footnote 23

Section 3: A snapshot of Canada’s skills development landscape

Strategic workforce development approaches must address both current and anticipated future needs. Efforts must be focused on the following 4 groups of workers to drive growth and productivity:

-

Help job seekers be ready to work: Equipping new entrants to meet on-the-job demands

Concerted effort has been made to improve the quality and consistency of more granular labour market information. This informs training investments that facilitate skills development aligned with industry needs in emerging and growth areas. Canada has strong foundations with K-12, post-secondary education, and work-integrated learning initiatives geared toward better school-to-work transitions.

-

Maximize participation: Growing the workforce from within Canada

Inclusion of all Canadians who want to work is a priority. With a focus on outcomes, emphasis is being placed on improving programming for underrepresented groups and those further from employment. This includes providing support to employers to help them foster more inclusive workplaces and employee engagement, and offering wraparound supports tailored to individual needs to remove barriers.

-

Improve skills availability: Upskilling and reskilling the existing workforce

To enable workers and employers to keep up with shifting skills demands within shorter cycles of change, increased attention is being placed on supporting skills upgrading and retraining so that individuals can make the most of opportunities. This includes supporting mid-career workers who are in sectors in transition as well as those who are unemployed and actively looking for work so they can develop skills needed to pursue new opportunities.

-

Grow Canada’s talent pool: Attracting and retaining global talent

With global competition for attracting and retaining talent, improving newcomers’ success in getting good jobs and opportunities for career progression aligned with their knowledge, skills and interests is imperative. Investments are being made to strengthen supports available from pre-arrival, foreign credential recognition, integrated settlement, employment supports and career advancement.

Workforce development in Canada involves a broad network of actors that are providing a range of supports to meet diverse needs

A wide array of organizations are involved in skills development nationwide. This includes governments, unions, education and training providers, industry/business associations, employers, Indigenous governments and organizations, not-for-profit organizations, researchers, academics, and others. Collectively they provide individuals with a range of options to gain access to needed supports. To maximize collective return on investments, working together creates opportunities to improve coordination, fill gaps and identify efficiencies. This would help to expand reach and deliver better results for more people.

Canada supports innovation in skills training or other national priorities more broadly. Employers, unions and workers experience many common challenges that extend beyond a particular province or territory, spanning across a region or nationally. The Government of Canada fosters cross-sectoral collaboration to test innovative approaches, identify promising practices and help replicate proven practices based on reliable evidence across the country. The Government also administers national programs that address worker needs, such as Employment Insurance (EI), Job Bank and labour market information investments. EI in particular is a critical part of Canada’s social safety net, providing temporary income for approximately 2 million Canadian workers each year, funded through premium contributions from employers and employees in insurable employment. The Government also supports federally delivered programs to provide Canadians, particularly underrepresented groups such as Indigenous people, with consistent access to programming across the country that addresses their specific needs.

Education is the responsibility of provinces and territories (PTs). This includes early childhood education, primary education, post-secondary education, private institutions, apprenticeships, skilled trades certification and various professional accreditations. PTs are also responsible for labour market programs responsive to unique jurisdictional needs, including programming funded through EI and federal transfers under the labour market transfer agreements and their own provincially funded programs.

Indigenous governments and organizations play a key role in providing employment and training supports. This includes the delivery of labour market programming funded through mainstream and Indigenous-specific initiatives like the Indigenous Skills and Employment Training Program (ISET) and the Skills and Partnership Fund (SPF). The ISET program was co-developed with Indigenous partners and provides funding to Indigenous service delivery organizations that design and deliver job training services to First Nations, Inuit, Métis and urban/non affiliated Indigenous people in their communities, while SPF compliments the ISET program by fostering partnerships between Indigenous organizations, governments and industry to address specific labour market needs linked to economic opportunities at the local, regional, and national level. These programs empower Indigenous communities, enhancing their workforce capabilities and ensuring sustainable employment opportunities and economic growth.

Employers and unions contribute to workforce training through on-the-job training, apprenticeships and professional development programs

Employers play an active role in supporting training and skills development. They make formal (such as, occupational safety and health training) and informal (such as, coaching) investments to meet organizational needs and enhance labour productivity. According to the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), 3 quarters of all adult learning in Canada is employer‑supported in some way. Supporting employers in overcoming structural barriers to training investment is key to addressing labour and skills shortages.Footnote 24

Estimates for how much employers invest in training vary. Generally, Canadian business investments seem to lag those of international peers in rates and hours of instruction. The Future Skills Centre indicated that firms invested an average of $240 per employee annually,Footnote 25 while the Business Council of Canada found in 2021 that, among 95 employers, two-thirds reported spending more than $500 per employee. The latter brings together Canada’s largest companies, which offers a glimpse of the differences with smaller businesses. This is reinforced by the Survey of Employers on Workers’ Skills that, in 2022, found 79% of large businesses used training to address their skills gaps, while only 61% and 68% of small and medium businesses respectively did so.

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) face particular challenges. Limited financial resources and employee release time are common constraints in supporting training. As of December 2022, there were 1.22 million employer businesses in Canada. Micro-enterprises (1−4 employees) make up over half (55.3%) of Canadian businesses. By adding those businesses with 5−9 employees, this number increases to 74.1%. In other words, almost 3 out of 4 Canadian businesses have 1−9 employees. SMEs employ 10.3 million people in Canada, or 90% of private-sector employment, and 63.8% of the workforce. Given SMEs reach with Canadian workers, helping them to facilitate employer-supported training is a priority for any success in building momentum as a nation.

Business associations also support workforce training. Business and industry associations, for example sector councils, play an active role in developing standards and curricula and delivering training that supports workforce development, contributing to innovation, productivity and competitiveness.

Unions play a key intermediary role between employers and workers to support skills development that meets workplace needs. They provide technical training, skills upgrading and occupational health and safety courses, as well as training in foundational and transferable Skills for Success (such as, literacy, numeracy, communication, problem solving). They offer upskilling and mentorship opportunities for unionized apprentices and journeypersons. Unions source significant funding through joint labour-management contributions to training trust funds.

Canadians self-fund training, but there is variation in needs and availability of supports

Many Canadians recognize they need to upgrade their skills; however, affordability is a challenge for some. Many people take courses or find training options that help them to develop skills to improve their performance in their current jobs and to prepare for new opportunities. However, with affordability challenges becoming a growing concern, many Canadians face barriers, particularly those with a low income. In 2022, close to 1 in 10 (9.9%) Canadians were living in poverty, with 16.9% of Canadians experiencing food insecurity. Flexible training formats that allow workers to pursue upskilling while balancing work and family responsibilities are essential to meet the needs of Canadians. Student financial assistance offers support to access post-secondary education while the Canada Training Credit is a reimbursable tax credit that helps workers to offset the cost of training.

Under-represented and disadvantaged groups face barriers and unequal access to training

Some groups are at risk of being left further behind. Underrepresented groups and individuals with low income and poor educational attainment have lower labour market outcomes. This is exasperated with an increase in numbers due to changing demographics. The most commonly identified barriers related to accessing training include:

- accessible training and skills development for persons with disabilities

- cost of skills training for Canadians with low income

- limited digital access for certain groups

- opportunities for youth to develop foundational and transferable skills

- implications of intergenerational poverty on social capital which contributes to labour market outcomes

- culturally relevant material for Indigenous people

- underemployment of racialized Canadians and immigrants, which may result in systemic barriers to developing foundational, transferable, language and other skills

- access to supports in rural, remote, and official language minority communities

- long and complex processes to obtain accreditation and recognition of professional skills for new Canadians

Section 4: Moving forward—opportunities to foster a modern, diverse, inclusive and productive 21st century labour market

Creating an inclusive and efficient labour market that aligns with economic priorities requires coordinated, deliberate actions by all involved. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to workforce development. A strategic focus and collaboration across sectors can create a new way forward for Canada. This section proposes 3 overarching priorities in building the labour market for the 21st century.

Priority one: Ensuring better alignment between workforce strategies, training institutions, labour groups, employers and economic priorities

Businesses could invest in more training; training institutions, labour groups and employers would have the tools and information to drive workforce development strategies toward future priorities. As noted earlier, the OECD’s PIAAC found that adults receiving employer support were significantly more likely to participate in adult learning and training than those without. For SMEs, there is a need to provide supports that help them to facilitate workplace training such as organizational needs assessments, training aligned with business needs and sectoral approaches. Helping SMEs to overcome common challenges of time, money and capacity could enable them to reap the benefits of employee retention, reduced staff turnover and recruitment costs. There is also a need to expand access for training institutions, labour groups and employers to more timely, granular labour market information tailored to sectoral, occupational and geographic realities. This could help to underpin the decisions of all involved to better align training to ever-shifting labour market needs.

Canada could have strong ecosystems that drive consultation and coordination among partners on regional/national basis, aligned with priorities for growth. There are many factors that contribute to the right enabling conditions for labour productivity such as infrastructure, housing, health care, agriculture, etc. Developing approaches for more coordination and collaboration could help to foster greater cohesion and mitigate duplication of efforts across the federal government and with partners and stakeholders. Bilateral and multilateral engagement among labour market partners complements unique jurisdictional realities such as coordinating regional economic priorities and delivering different service models, among others. The Government could strengthen internal governance mechanisms while also creating mechanisms that facilitate cross-sectoral social dialogue and collective action.

Employers and sectors could be engaged in identifying their skills and training needs to ensure programs effectively train new entrants into the workforce (for example, youth) and upskill existing workers. With the rapid nature of change in Canadian workplaces, it is getting harder for education and training providers to be aware of and adapt to shifting business requirements. There is growing appreciation of the importance of industry and training partnerships to enable workforce development approaches to adapt in a timelier manner. For example, work-integrated learning could be leveraged as a recognized means domestically and internationally to effectively help job seekers and workers to round out classroom learning through real-world experiences. Place-based approaches are another area of growing interest that could help to identify ways to maximize regional and national economic development investments by better aligning workforce development strategies.

Priority two: Eliminating inefficiencies and barriers in Canadian labour markets

Efforts could be made to foster a labour market free of regulatory and other barriers to employment, training and career progression to drive employment outcomes and participation rates. Foreign credential recognition and inter-provincial/territorial labour mobility are 2 areas in which federal, provincial and territorial governments could work collaboratively to remove barriers that are constraining workers to fully contribute. Through cooperation and alignment of efforts, governments could identify ways to strengthen employment outcomes upon entry for newcomers and to improve interprovincial labour mobility. Governments could foster the enabling conditions that remove barriers for Canadians to be able to work across the country and to move for personal and professional reasons, which would benefit all.

Immigration pathways could be aligned to both labour strategies and long-term human capital needs across the economy. A range of immigration pathways exist to meet Canada’s labour demands. This includes calibrating approaches for permanent and temporary residents. With increasing geopolitical tensions globally, there is a need to consider how to better support asylum seekers. There is also a need to ensure that the Temporary Foreign Worker Program best serves Canadians’ interests. Labour policies must focus on a human capital approach to drive growth, and immigration will play a key supporting role as part of the solution.

Employment barriers could be removed for under-represented groups. Employers play a central role in facilitating inclusion and meaningful employment opportunities for all under-represented groups. As most employers in Canada are SMEs, many do not have human resources, learning and development expertise in-house. Better supports could be provided to them to make incremental changes to foster greater employee engagement such as reviewing organizational policy for potential barriers (for example, job descriptions, work arrangements, accommodations, inclusive language in hiring practices). Along with employers, governments, labour and other organizations could play a role too. For example, most accommodations for persons with disabilities cost less than $500, which presents an opportunity for public-private partnerships.Footnote 26 For older workers, this may include training to adapt to the use of new technologies and adjusting pension policies.

A culture of new workforce development initiatives could be encouraged that is agile and innovative, continually incorporating new best practices identified through experimentation and impact analysis. There is a wealth of knowledge across sectors on how to effectively address the differing needs of Canadians. These good practices could be replicated and scaled up nationwide. For example, for those further from employment, wraparound supports have been identified as effective in improving employment outcomes. These supports could help to remove barriers (such as, child care, transportation, housing), in particular for underrepresented groups. As another example, language training could be combined with other employment and training supports for newcomers, which is seen to be a promising practice.

Priority three: Maximizing labour productivity through strategic skills development and lifelong learning

Essential skill development across jurisdictions and institutions could focus on workforce development as a driver of growth in a clean, digital and resilient economy. The level of proficiency in different skills (for example, digital skills, writing) varies by occupational demands. For example, a carpenter and a foreperson both require communication skills applied in different ways to meet the demands of their respective jobs. As workers make several job changes over their careers, the development of foundational skills could be embedded in all labour market programming. For example, strategic investments could be made, including active employment measures delivered by PTs and Indigenous governments and organizations as well as other federal programs. Different tools could be consolidated, and federal, provincial, territorial and Indigenous governments could work together to improve coordination to improve availability of needed supports. Skills for Success could be complemented with other skills investments that cut across different sectors and occupations such as green, digital, cyber and AI skills.

Existing workers and adult learners could have access to upskilling throughout their careers, addressing a persistent gap in the policy landscape for proactive workforce development programming. As adults acquire skills and competencies through different life and work experiences, there is growing interest from workers and employers to make the most efficient use of limited time and resources. Working adults could benefit from personalized guidance and flexible training supports. One promising example is competency-based approaches that could assess worker skills and offer flexible, personalized training options to meet on-the-job expectations and better labour market integration. Career guidance and shorter duration training options (such as, microcredentials) are other needs being identified that could be addressed. These could help working adults make informed training decisions and could improve motivation and successful completion of training by targeting specific needs. There are also lessons that could be learned from investments other countries are making. Countries such as Australia, the United Kingdom, France and Singapore are building new training infrastructure to address structural changes in modern labour markets that could inform Canadian efforts.

Conclusion

Canada’s labour market is going through several structural shifts–demographic changes, shifting economic priorities, climate change, and rapidly changing nature of work. Layer on lower labour productivity, global talent competition, and changing business and worker models and it becomes evident that a complex, coordinated set of actions are needed to best position the country to thrive in the years ahead.

Our advantage is a highly networked range of organizations across sectors that are leaning in and are eager and motivated to play an active role in working together in the best interest of Canadians and the nation. All recognize that increased social dialogue among industry, employers, education and training providers, Indigenous and not-for-profit organizations, academics, Federal, Provincial, Territorial and Indigenous governments and other interested groups is essential. It allows us to establish a common understanding of some of the opportunities and challenges that we face as a country now and into the future–and together, identify priority areas for action and how each of us can play our respective parts.

Tell us what you think

As noted, this paper aims to discuss change drivers, provide a snapshot of Canada’s current skills development landscape and identify priority areas for action in moving forward. Your organization’s input is valued. Please let us know what you think by filling out the following questionnaire.