Canada-United States Air Quality Agreement Progress Report 2012: chapter 4

Section 4: Fourth Five-year Review and 20-year Retrospective of the United States-Canada Air Quality Agreement

Introduction

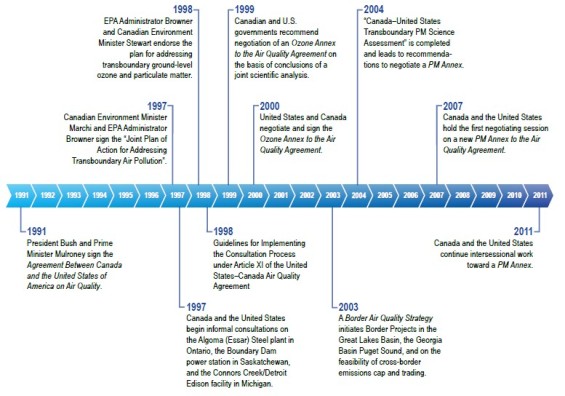

Article X, Review and Assessment of the Agreement Between the Government of Canada and the Government of the United States of America on Air Quality, requires Canada and the United States to “conduct a comprehensive review and assessment of [the] Agreement, and its implementation, during the fifth year after entry into force and every five years thereafter, unless otherwise agreed.” Article X is intended to ensure that the Parties periodically review and assess the Agreement to determine whether it remains a practical and effective instrument to address shared concerns regarding transboundary air pollution. There have been three Five-Year Reviews so far: in 1996, 2002, and 2006.

This Five-Year Review coincides with the 20thanniversary of the Agreement and therefore presents a 20 year retrospective that celebrates key accomplishments, outlines important challenges, and discusses the prospects for the Air Quality Agreement going forward.

20 Year Retrospective: Accomplishments and Challenges

The U.S.-Canada Air Quality Agreement has been a model of successful bilateral cooperation that has achieved tangible improvements in the environment over its 20 year history.

Addressing Acid Rain:

Signed in 1991 to address “acid rain” or acidification that was damaging aquatic and terrestrial ecosystems in the eastern parts of the United States and Canada, the Air Quality Agreement committed the U.S. and Canada to reduce emissions of SO2and NOX, the pollutants that cause acid rain.

As a result of commitments under Annex 1, achievements include:

- In the U.S., as of 2011, the national Acid Rain Program has reduced emissions of SO2 by 71 percent from 1990 levels. Power plant emissions of NOX have decreased by over 69 percent from 1990 to 2011 under the U.S. Acid Rain Program and other regional programs.

- In Canada, as of 2010, total emissions of SO2 have declined by 57 percent from 1990 levels, mainly due to the 74 percent reduction in emissions from the non-ferrous smelting and refining industry and the 52 percent decrease from fossil fuel-fired electricity generating utilities during the same time period. Total emissions of nitrogen oxides, mainly from transportation sources and power plants have decreased by 18 percent between 1990 and 2010.

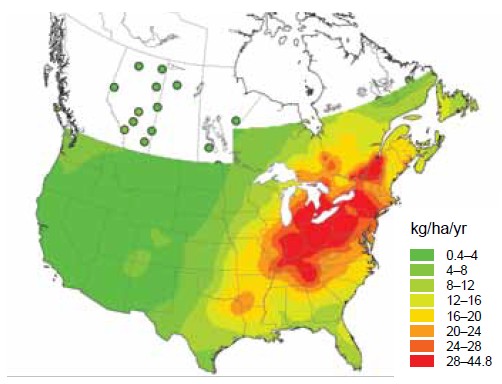

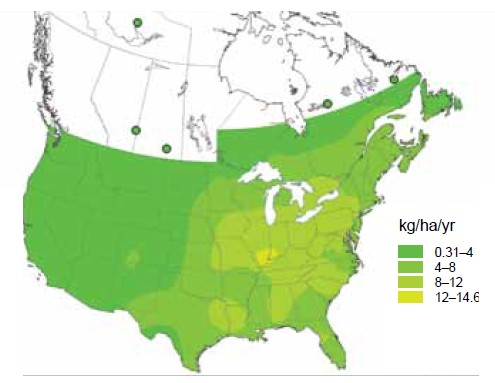

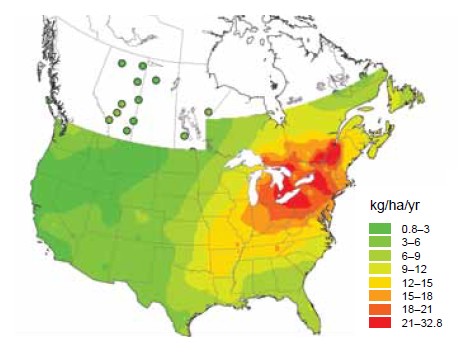

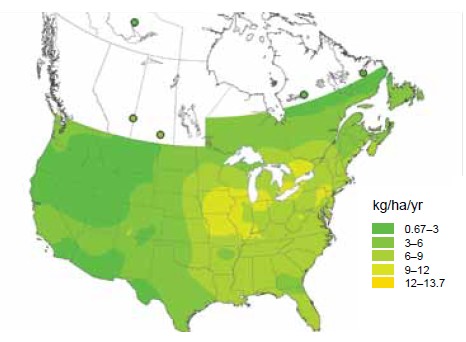

- The extent of the ecosystems damaged by acidification has decreased in response to the emission reductions since 1991 and many of the acidified lakes and streams are recovering. The maps presented in the “Acid Deposition Monitoring, Modeling, Maps, and Trends” section of this report illustrate the large reduction in the amount of acidifying substances received by ecosystems in the 20 years since the Air Quality Agreement was signed.

Figure 36 depicts the vast change in deposition since the Agreement started in 1991.

Figure 36: Changes in Annual Wet Sulfate and Wet Nitrate Deposition, 1990-2010

1990 Annual Wet Sulfate Deposition

2010 Annual Wet Sulfate Deposition

1990 Annual Wet Nitrate Deposition

2010 Annual Wet Nitrate Deposition

Source: NAtChem Database (www.ec.gc.ca/natchem/) and the NADP (nadp.isws.illinois.edu/), 2012

Addressing Ground-Level Ozone:

In the late 1990s, ground-level ozone, or summertime smog, was recognized as contributing to thousands of premature deaths across Canada and the U.S. each year, as well as increased hospital visits, doctor visits, and hundreds of thousands of lost days at work and school. The Ozone Annex was added to the Agreement in 2000 to address this problem and reduce transboundary ozone pollution. It calls for reductions in the emissions of NOX and VOCs, the pollutants that cause summertime smog and affect the health of Canadians and U.S. citizens and their environments.

The Ozone Annex identifies the regions in Canada and the U.S. where decreases in emissions of NOX and VOCs would reduce transboundary ozone pollution in the other country and it sets out emission reduction requirements within those regions. These transboundary ozone regions or PEMAs (see Figure 37) include parts of southern Quebec and southern and central Ontario in Canada and, in the U.S., 18 midwestern and eastern states, and the District of Columbia.

Figure 37. Ozone Annex Pollutant Emission Management Area (PEMA)

Source: United-States Canada Air Quality Agreement, Ozone Annex

As a result of commitments under the Ozone Annex, achievements since 2000 include:

- Reduced emissions of NOX and VOCs by 40 percent and 30 percent, respectively, in the Canadian PEMA.

- Decreased emissions of NOX and VOCs by 42 percent and 37 percent, respectively, since 2000 in the U.S. PEMA.

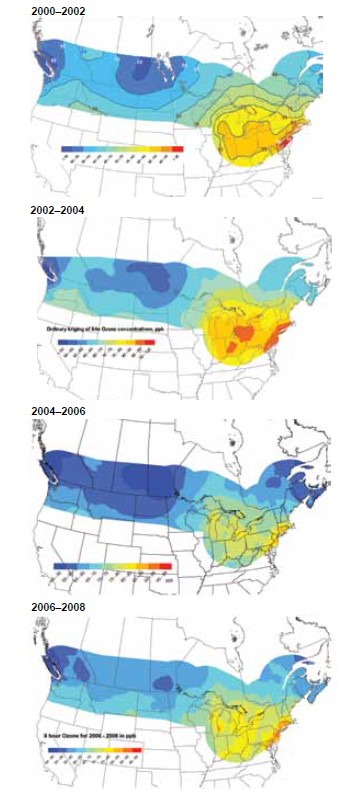

- Where ozone levels were being increased by transboundary pollution before 2000, summertime ozone levels in the air within the eastern parts of Canada and the United States have shown measurable decreases over the 1997 to 2006 period coinciding with the large reductions in emissions of NOX and VOC in the PEMAs defined in the Ozone Annex.

Tracking and Reporting Progress:

The tracking and reporting of results is an important commitment in the Air Quality Agreement. Parties meet annually under the auspices of the Air Quality Committee, the body, along with its subcommittees, responsible for overseeing, administrating and ensuring implementation of the Agreement. It is within this committee that Canada and the U.S. report to each other on progress and activities under the Agreement. Detailed reports have been consolidated by the U.S. and Canadian governments in the 11 biennial progress reports made publicly available in the twenty years since the Agreement was signed.

The purpose of tracking, under the Agreement, is to provide an early warning system so that if for example, ozone levels begin to increase outside of the eastern area that has been the Agreement’s focus, it is documented and addressed. For this reason, ozone levels within 500 km of the entire length of the U.S.-Canada border are tracked and reported. Ozone levels change as the location of economic activity changes providing the basis for serious discussion and action under the Agreement.

Reporting can be detailed and useful for both Parties. In addition to reporting on emission reduction commitments, for example, the U.S. and Canada report on critical loads for acidification, allowing a comparison between existing deposition levels and the level of deposition that would damage an ecosystem; and on air quality standards for ozone set by the U.S. and Canadian governments so as to facilitate comparisons between the levels of ozone being reported from air quality monitors in both countries. Furthermore, the U.S. and Canada also share information on associated domestic activities as well as regional bilateral efforts such as: those of the Eastern Canadian Premiers/Northeastern Governors, and border air quality projects in the Great Lakes Basin and in the Georgia Basin-Puget Sound airsheds. Much of this information is summarized for the public in the biennial progress report.

It is important to note that, according to the International Joint Commission’s syntheses of public comments received in relation to the 2008 and 2010 Progress Reports (the reports produced by the Air Quality Committee since the last 5-Year Review), the public has been satisfied with the progress made by each country to reduce emissions of SO2, NOX, and VOCs. Further, the public comments have expressed overall support for the Agreement and its success in fostering cooperation on transboundary air pollution control, monitoring, research, and information exchange.

Figure 38 shows maps from the four Progress Reports since 2004 illustrate how ozone levels are changing across the southern U.S.-Canada border area - with ozone levels decreasing significantly in the central eastern area and increasing slightly in the western area. This trend continues as evidenced in the most recently updated Ozone Concentrations map (2008 to 2010) in the body of this 2012 Progress Report (see section 1).

Note: Data contoured are the 2000-2002, 2002-2004, 2004-2006, and 2006-2008 averages of annual fourth highest daily values, where the daily value is the highest running 8-hour average for the day. Sites used had at least 75 percent of possible daily values for these periods.

Source: Environment Canada National Air Pollution Surveillance (NAPS) Network Canada-wide Database www.ec.gc.ca/rnspa-naps/Default.asp?lang=En&n=5C0D33CF-1)index_e.htmland EPA Aerometric Information Retrieval System (AIRS) Database

Reporting outcomes also effectively shows where actions by governments have not gone far enough. For instance, it is clear from deposition monitoring that the extent of the acidified ecosystems has decreased in eastern United States and eastern Canada in response to the large SO2 and NOXemission reductions. The Progress Reports clarify, however, that acidification continues to be a problem in certain ecosystems in eastern states and provinces and more will need to be done if these ecosystems are to be restored to their former health. In terms of the Ozone Annex, the Parties agreed that the objective of the Annex was to help “both countries attain their respective air quality goals over time to protect human health and the environment.” This agreement means that the Parties can continue to discuss actions to control transboundary ozone where ozone air quality levels that are above the standards are being affected by transboundary flows of ozone and precursors. It also illustrates areas where more work has to be done, for example, in reporting human health and environmental effects in response to the decreases in emissions that the Ozone Annex requires.

There have been reporting challenges that, through cooperation, have been overcome. In the 1990s, different approaches and methodologies used in each country required information and data to be provided in a parallel fashion within the Progress Reports. For instance, emissions were not counted in the same way in both countries and were therefore not easily comparable and could not be used in air quality modeling in both countries. The protocols for air quality monitoring and deposition monitoring were different in each country and it was not possible to demonstrate to Canadians and Americans what was happening across the transboundary region with one map.

Over the past twenty years under the Agreement, however, the dissonance that hampered bilateral performance reporting and air quality research has been smoothed by cooperation among scientists. A review of the Progress Reports since 2000 shows that, despite continuing to use different metrics, harmonized protocols and methodologies for monitoring, measurement, and modeling now create “borderless” maps, tables, and graphics.

Grounded in science, the Air Quality Agreement provides the basis for scientific cooperation and exchange.

The Air Quality Agreement was created to address acid rain at a time when scientists in the United States and Canada had divergent views of acidification. This meant that there was no common evidence on acidification to advise the U.S. and Canadian governments. Seen in the light of these scientific differences, the negotiation and signature of the Air Quality Agreement in 1991 was a significant achievement. An equally important accomplishment was the commitment that the Agreement makes to scientific and technical cooperation and information exchange, enshrined as an annex (Annex 2) to the Agreement.

This cooperative stance had borne fruit by the time of the U.S.-Canada discussions leading to the negotiation of the Ozone Annex. The implementation of the Air Quality Agreement meant that an institutional forum for scientific cooperation on transboundary air pollution had been created and scientists were able to work together to establish common statements of the facts. Under the Agreement, scientific evidence was gathered to demonstrate that ozone was flowing across the border and that it was causing damage to human health. For the first time, both Canadian and U.S. governments recognized that the scientific information they were provided through the bilateral forum was credible and could be the basis for policy recommendations.

Since then, Canada and the United States have advanced their abilities to develop scientific consensus on transboundary air pollution by establishing both common and comparable analytical techniques and atmospheric models to define air quality issues and analyze forecasts that can be the basis for advice to policy makers and government leaders.

In 2004, when the Canada-United States Transboundary Particulate Matter (PM) Science Assessment was completed, it represented the culmination of work undertaken to meet the charge of the Air Quality Committee to its Subcommittee on Scientific Cooperation to “summarize and understand the current knowledge of the transboundary transport of PM and PM precursors between Canada and the United States in a scientific assessment.” The Air Quality Committee had recognized the fact that large regions of eastern Canada and northeastern United States continued to receive acidifying emissions of SO2 and NOX and that these emissions also contribute to PM pollution. The Transboundary PM Science Assessment was completed by U.S. and Canadian scientists who brought their knowledge and expertise together to create a fully binational assessment. This achievement was important because it became the basis for a recommendation by the Air Quality Committee to the U.S. and Canadian governments to negotiate a PM Annex to the Air Quality Agreement to address transboundary PM and acidification. It was also important, however, because it demonstrated that what was envisaged for binational cooperation when the Agreement was signed had become a reality.

Binational science carried out at the request of the Air Quality Committee had become, in fact, the basis for the two nations cooperating toward solutions for a common transboundary air quality concern. It is expected that technical and regulatory work to support the consideration of the addition of a PM Annex to the Air Quality Agreement will continue in the coming years. This work will include the updated review and assessment of the science associated with transboundary flows of PM and its precursors which is currently underway.

The Air Quality Agreement provides a basis for cooperation on issues of common interest or concerns.

The Air Quality Agreement was created as an instrument to provide for bilateral cooperation in addition to committing to actions to reduce emissions and carry out scientific and technical exchanges. The Agreement and its administrative arm, the Air Quality Committee, have provided the basis for a number of important bilateral cooperative ventures.

The Agreement’s Article V “Assessment, Notification and Mitigation” and Article XI “Consultations” were drafted to deal with one country’s concern about pollution coming from a specific industrial source into the other. Under Article V, Parties are required to notify each other when a new or modified emission source is expected to have an impact on the other’s air quality through transboundary movement. This up-front open disclosure facilitates cooperation on mitigation before any irritants exist.

A shared objective, a commitment to the Agreement, and a willingness to cooperate is all that is usually needed. For example, in 1998, the concern of residents of Windsor, Ontario about potential pollution from an old coal-fired power plant in Detroit, Michigan, came to the attention of Canadian members of the Air Quality Committee. The Air Quality Committee’s coordination of concerned provincial and state governments and U.S. federal regulators was all that was required to address the problem.

In fact, to ensure that any future concerns about specific industrial sources could be handled without confrontation and in a spirit of cooperation, as had been the case with the Detroit power plant, Guidelines for Implementing the Consultation Process under Article XI of the United States-Canada Air Quality Agreement were proposed and approved by the Air Quality Committee at its 1998 Annual Meeting. The Guidelines lay out practical steps on how the two countries could consult informally when one country has concerns about a source of pollution in the other. These guidelines became the basis for discussions that occurred to address pollution crossing the border into North Dakota from the SaskPower Boundary Dam Power Plant in Estevan, Saskatchewan, and also in relation to the Essar Steel Algoma, Inc. facility in Sault Ste. Marie, Ontario. Both of these informal consultations included discussions of abatement programs at the source of the pollution and transboundary air quality monitoring networks with monitors supplied by U.S. and Canadian governments and, in the case of SaskPower, by the power plant. Reporting back to the concerned citizens on the results from the air quality monitors was a key feature of the informal consultations.

The informal consultation related to the SaskPower facility was successfully terminated when SaskPower installed emission abatement technology and the monitoring in Saskatchewan and North Dakota showed that no air quality standards were being exceeded. The discussions around the Essar Steel Algoma, Inc. facility continue but are likely to be concluded in the next year.

Three Border Air Quality Strategy projects offer additional examples of how the Agreement has provided the basis for cooperation that has advanced the transboundary air quality dialogue in flexible and innovative ways. Between 2003 and 2006, two airshed projects -- the Georgia Basin-Puget Sound International Airshed Strategy and the Great Lakes Basin Airshed Management Framework -- became important sources of practical on-the-ground cooperation. They each focused on assessing air quality issues and programs in those border regions. Another substantial aspect of these two Border Air Quality projects was the research programs carried out between 2003 and 2007 to characterize air pollution exposure and human health issues under the Canadian portion of the Border Air Quality Strategy coordinated with research in the U.S. The results of this research has added significantly to the scientific understanding of the health effects of ozone exposure and assisted in defining how to communicate to people the risks they face from air pollution.

A third study under the Strategy analyzed the feasibility of a cross-border SO2 and NOX emission cap and trading program. The Air Quality Agreement had identified in 1991 that market-based mechanisms should be a topic for information exchange. In 2003 to 2005, the Canada-United States Emissions Cap and Trading Feasibility Study was undertaken. The study analyzed the complex issue of emission caps and trading to achieve acid rain and air quality goals using teams of experts in air quality, economic and atmospheric modeling, governance, and law.

The Agreement in the Next 20 Years

Should the Air Quality Agreement Progress Reports be streamlined?

Public comments to the International Joint Commission since 1992 in relation to the biennial Progress Reports strongly support the overall scope and nature of the Progress Reports and the valuable information that the Progress Reports are uniquely positioned to provide. Streamlining reporting to take full advantage of the way information can be communicated in the 21st century may, however, be worth considering especially if new methods of reporting can take advantage of communication opportunities offered by digital media.

Should the Air Quality Agreement expand its scope to address new issues and new regions within the U.S.-Canada border area?

The Agreement currently addresses U.S.-Canada acidification and ground-level ozone and is discussing how to address transboundary PM. In 1996, the Air Quality Committee decided that the Agreement should not be used to address persistent toxic pollution (e.g., mercury, PCBs, dioxin) on the basis that, firstly, these pollutants travel long distances in the atmosphere and cross all borders, with the vast majority of emissions globally coming from outside of North America. Secondly, other more suitable international instruments, such as the Stockholm Convention that addresses persistent organic pollutants globally and negotiations under United Nations Environmental Program (UNEP) to address mercury globally preclude the need for a bilateral instrument.

In terms of possible future expansion of the Agreement, the Perimeter Security and Economic Competitiveness Regulatory Cooperation Council (RCC), in its 2011 Joint Action Plan for the Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council stated that “there are significant health and environmental benefits to expanding the [Air Quality] Agreement, with a focus on reducing particulate matter.“ The RCC called for Environment Canada, the U.S. State Department, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to consider an expansion of the U.S.-Canada Air Quality Agreement to address PM based on comparable regulatory regimes in the two countries. An expansion of this kind is grounded in the science being updated under the Agreement on transboundary PM. It also complements the work both Canada and the U.S. are doing within the UNECE Long-range Transboundary Air Pollution (LRTAP) Convention where efforts are underway to address long-range transboundary PM and the related issue of black carbon, recognizing the synergies with health, climate change, and biodiversity in North America and the Northern Hemisphere.

The Air Quality Agreement could also focus, in the future, on transboundary air quality issues in the western border area if scientific evidence demonstrates that there are transboundary air issues of concern and clarifies that cooperation would benefit the health and welfare of Canadians and U.S. citizens and their environments. For instance, although it is clear that emission reductions completed on acid rain and ozone under the Air Quality Agreement have already resulted in PM emission reductions of 34 percent, the 2004 Transboundary PM Science Assessment demonstrates that in some western provinces and states, PM levels are increasing and the related issue of visibility is degrading as economic activity grows in the energy sector.

The lower mainland of British Columbia has viewed visibility as an instrument for air quality management in part due to the fact that the Canadian air quality standards for PM and ozone have been insufficiently stringent to drive air quality management in that area. The issue of visibility may provide an opportunity under a possible future PM Annex to address transboundary air quality in the western border region of Canada and the U.S., especially if more visibility monitoring is in place to assess changes or if background levels of ambient air are monitored to assess improvements in the region. To date, however, unlike in the U.S., visibility, while arguably an interesting indicator, may not have relevance at a national level. Canada continues to study the issue and its possibilities.

In the north along the U.S.-Canada border (Alaska, Yukon, and Northwest Territories), the Air Quality Agreement could provide the basis for bilateral scientific and technical exchanges and an opportunity to cooperate if development on either side of the border generates concerns. For instance, the Notification provision under the Agreement could be strengthened in a renegotiated Agreement to provide the basis for practical exchanges of information among governments in the North when governments are processing permits for new development that could become potential sources of transboundary pollution. The plans for opening the Arctic region to greater shipping, significant energy extraction, and mining activities are cause for discussion on potentially increased bilateral notification and cooperation.

The Air Quality Agreement will be most effective in the coming years if it continues to concentrate on what it does best, i.e., addressing transboundary air pollution issues of concern through a “made in Canada-United States” vision that is built on the unique nature of the bilateral relationship and takes account of the inherent complexities of national economies and styles of governance that differ in so many ways. At the same time, work under the Agreement should continue to develop and enhance relationships between experts in the U.S. and Canadian governments to ensure that the differences in air quality goals and objectives, governance, program administration, and implementation are the basis for enhancing each others’ points of view rather than hindering cooperation.

Conclusion

In the past 20 years, the Agreement between the Government of Canada and the Government of the United States of America on Air Quality has proven that it is possible to design and implement a bilateral accord in which commitments or obligations recognize and allow for different approaches taken by the Parties in the effort to reduce air pollution. The Agreement required significant changes from major industries with associated costs. It took great political will on the part of both countries at the highest levels; produced dramatic results with huge benefits for human health and the environment; and created a structure that allowed for subsequent agreement (e.g., Ozone Annex) and more dramatic results.

The success of the Agreement over the last 20 years rests on two things: supportive, cooperative, and committed working relationships; and an environment of mutual trust. For the next 20 years to be as successful as the first, these two winning conditions must continue to underpin the implementation of the Air Quality Agreement.