Bird Conservation Strategy for region 6 in Canada

- Abridged version -

October 2013

The abridged version of the strategy available here contains a summary of the results, but does not include an analysis of conservation needs by habitat, a discussion of widespread conservation issues, or the identification of research and monitoring needs.

Table of contents

Preface

Environment and Climate Change Canada led the development of all-bird conservation strategies in each of Canada's Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs) by drafting new strategies and integrating new and existing strategies into an all-bird framework. These integrated all-bird conservation strategies will serve as a basis for implementing bird conservation across Canada, and will also guide Canadian support for conservation work in other countries important to Canada's migrant birds. Input to the strategies from Environment and Climate Change Canada's conservation partners is as essential as their collaboration in implementing their recommendations.

Environment and Climate Change Canada has developed national standards for strategies to ensure consistency of approach across BCRs. Bird Conservation Strategies will provide the context from which specific implementation plans can be developed for each BCR, building on the programs currently in place through Joint Ventures or other partnerships. Landowners including Aboriginal peoples will be consulted prior to implementation.

Conservation objectives and recommended actions from the conservation strategies will be used as the biological basis to develop guidelines and beneficial management practices that support compliance with regulations under the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994.

Acknowledgements

C. Lisa Mahon and Thea Carpenter were the main authors of this document that follows templates developed by Alaine Camfield, Judith Kennedy and Elsie Krebs with the help of the BCR planners in each of the Canadian Wildlife Service regions throughout Canada. K. Calon, A. Camfield, W. Fleming, T.J. Habib, K.C. Hannah, J. Kennedy, E. Kuczynski, and K. St. Laurent did all of the initial work to refine species priority lists, assess objectives and threats, and research habitat associations as well as producing drafts of the plan and populating the database. S. J. Song and D. Duncan provided a comprehensive review. However, work of this scope cannot be accomplished without the contribution of other colleagues who provided or validated technical information, commented on earlier draft versions of the strategy and supported the planning process. We would like to thank the following people: Erin Bayne, Fred Bunnell, Eric Butterworth, Wendy Calvert, Suzanne Carriere, Gordon Court, Brenda Dale, Ken DeSmet, Elston Dzus, Keith Hobson, Vicky Johnston, Kevin Kardynal, Glenn Mack, Craig Machtans, Julienne Morissette, Cindy Paszkowski, George Phinney, Mark Phinney, Gigi Pitoello, Doug Tate, Jennie Rausch, Myra Robertson, Mike Russell, Pam Sinclair, Stuart Slattery and Steve VanWilgenburg.

Bird Conservation Strategy for Bird Conservation Region 6: Boreal Taiga Plains

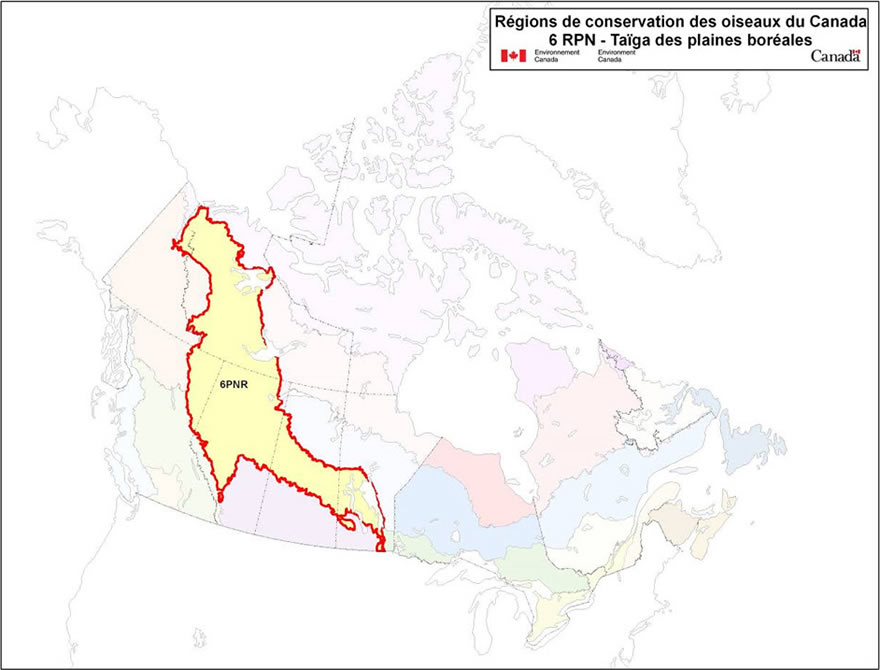

Long Description for map of BCR 6

Map of the Bird Conservation Regions (BCRs) of Canada with BCR 6, Prairie and Northern Region: Boreal Taiga Plains highlighted in light yellow with a red outline. Canada (with Alaska, Greenland and the northern portion of the United States of America also appearing, in grey) is shown very washed out, as it is only present to provide context for the location of the highlighted BCR 6. The washed out Canadian map is divided by BCR(12 Canadian BCRs in total), with various colours, and their exact locations and sizes are indistinguishable, aside from BCR 6.

The highlighted BCR 6 is approximately the shape of the letter “L” and extends from the Beaufort Sea in northern Northwest Territories and Yukon, south through the Northwest Territories, northeast British Columbia and most of Alberta, and then east through central Saskatchewan and southern Manitoba. The following legend appears in the top right corner of the map: “Bird Conservation Regions of Canada. 6 PNR - Boreal Taiga Plains” and includes the Environment and Climate Change Canada logo, and the Government of Canada logo.

Executive summary

Bird Conservation Region 6: Boreal Taiga Plains is comprised of two Canadian Ecozones: the Taiga Plains in the north and the Boreal Plains in the south. This large region extends from the Northwest Territories in the north to Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba in the south. The largest portion of the BCR is in the Northwest Territories (36%), with 1% in Yukon, 8% in northeast British Columbia, 33% in Alberta, 13% in central Saskatchewan and 9% in south-central Manitoba.

BCR 6 contains gently rolling or undulating landscapes due to the influence of glaciers during the most recent ice ages. Vegetation is dominated by the boreal forest, a diverse mixture of forest types including coniferous stands dominated by either white spruce (Picea glauca) or black spruce (Picea mariana), deciduous stands containing mixtures of trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides) and balsam poplar (Populus balsamifera), and mixed wood stands composed of trembling aspen, balsam poplar, white birch (Betula papyrifera), and white spruce. Forest stands are interspersed with wetlands in the form of: lakes and ponds; marshes; swamps; and herb, shrub or tree-dominated bogs and fens. Major river systems include the Mackenzie, Peace, Athabasca and North Saskatchewan.

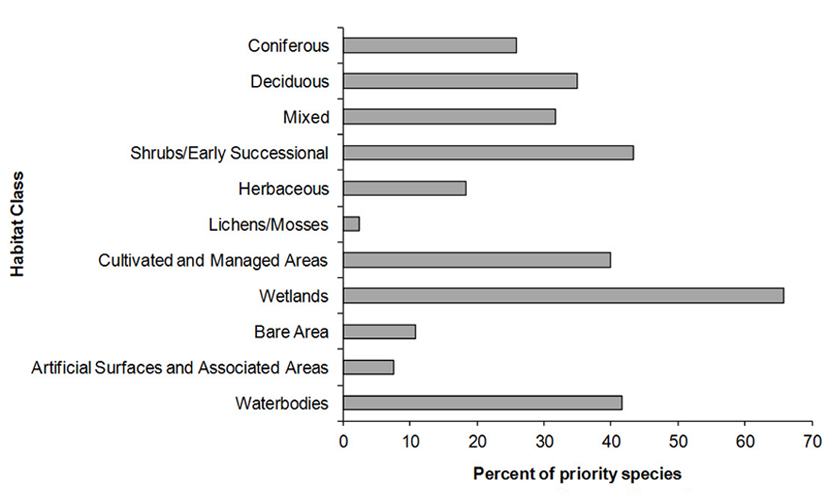

We evaluated 288 bird species that occur within BCR 6 and designated 120 species as priority bird species. All bird groups are represented, with 52% of the priority list consisting of landbirds, 12% shorebirds, 18% waterbirds and 18% waterfowl. Consistent with the representation of wetland habitats across the BCR, 66% of priority species are associated with wetland habitat classes. Following wetlands, there is prominent association with shrub/early successional (43%), waterbodies (42%), cultivated and managed areas (40%), deciduous (35%), and mixed forest (32%).

Population objectives are difficult to assess for many BCR 6 priority species due to limited or unavailable population trend data (e.g., evaluation of temporal patterns of change over multiple sample periods) for many boreal forest species. Existing monitoring programs (landbirds, waterfowl) are biased due to inadequate route coverage. Many landbird species (irruptive species, nomadic species, primary cavity nesters/woodpeckers, grouse, diurnal raptors, nocturnal raptors, species at risk), almost all waterbird and shorebird species, and cavity-nesting waterfowl species are not adequately monitored using existing monitoring programs.

Human disturbance is concentrated in the southern portions of the BCR (Boreal Plains Ecozone). The current dominant threats to priority species in BCR 6 include: agriculture, transportation and service corridors (linear features/disturbances in the form of roads, railways, power/utility lines, pipelines), biological resource use (forest harvesting), human intrusions and disturbance (motorized recreational activities), natural system modifications (fire suppression, dam construction and operation), invasive and other problematic species, and pollution (agricultural, forestry and energy sector effluents; oil spills). Additional low-intensity threats currently include residential and commercial development, and energy production and mining (conventional oil and natural gas deposits, non-conventional bitumen deposits).

The primary conservation issue in BCR 6 is ensuring the availability of suitable breeding habitat for priority species. Specific conservation actions are recommended across many categories; however, the most prominent categories are site/area management (managing protected areas and other resource lands for conservation), site/area protection (establishing or expanding public or private parks, reserves and protected areas) and research. Future recommended actions include both monitoring and research. Monitoring and research initiatives highlight the specific actions required to:

- develop and implement adequate long-term monitoring programs (e.g., programs that deliver reliable estimates of population trend) for each bird group (landbirds, shorebirds, waterbirds, waterfowl);

- predict the impact of current and alternative land and resource activities on populations;

- examine the causes of population declines; and

- develop the methods, data products, tools, and partnerships required to calculate habitat-based population objectives within BCR 6.

The key messages for priority bird species and all bird species that occur within BCR6 are:

- Categorical population objectives are difficult to assess due to limited or unavailable population trend data for boreal landbird, shorebird, waterbird, and cavity-nesting waterfowl species. The development and implementation of new monitoring programs for all bird groups in order to provide reliable estimates of population trend will be a high priority in BCR 6.

- Although BCR 6 is largely intact, the continued high rate of resource development in the southern portion of the BCR presents a potential risk to bird populations. Programs to anticipate and predict the impact of current and alternative land and resource development on bird populations will be needed to assess risk to populations. A combination of bird-habitat and landscape simulation models will be required to quantify expected future changes in population size in response to land use change.

- Conservation objectives and actions will need to focus on the conservation and management of suitable habitats. This will require the development of habitat suitability measures in the form of qualitative habitat ratings or quantitative habitat use measures (e.g., bird-habitat models) for each priority species.

- Approaches will be required to identify the amount of habitat required to meet categorical and associated numerical population objectives for priority species (e.g., translate BCR-scale population objectives into habitat-based population objectives).

Introduction: Bird Conservation Strategies

Context

This document is one of a suite of Bird Conservation Region strategies (BCR strategies) that have been drafted by Environment and Climate Change Canada for all regions of Canada. These strategies respond to Environment and Climate Change Canada's need for integrated and clearly articulated bird conservation needs to support the implementation of Canada's migratory birds program, both domestically and internationally. This suite of strategies builds on existing conservation plans for the four “bird groups” (landbirdsFootnote 1, shorebirdsFootnote 2, waterbirdsFootnote 3 and waterfowlFootnote 4) in most regions of Canada, as well as on national and continental plans, and includes birds under provincial/territorial jurisdiction. These new strategies also establish standard conservation planning methods across Canada and fill gaps, as previous regional plans do not cover all areas of Canada or all bird groups.

These strategies present a compendium of required actions based on the general philosophy of achieving scientifically based desired population levels as promoted by the four pillar initiatives of bird conservation. Desired population levels are not necessarily the same as minimum viable or sustainable populations but represent the state of the habitat/landscape at a time prior to recent dramatic population declines in many species from threats known and unknown. The threats identified in these strategies were compiled using currently available scientific information and expert opinion. The corresponding conservation objectives and actions will contribute to stabilizing populations at desired levels.

The BCR strategies are not highly prescriptive. In most cases, practitioners will need to consult additional information sources at local scales to provide sufficient detail to implement the recommendations of the strategies. Tools such as beneficial management practices will also be helpful in guiding implementation. Partners interested in participating in the implementation of these strategies, such as those involved in the habitat Joint Ventures established under the North American Waterfowl Management Plan (NAWMP), are familiar with the type of detailed implementation planning required to coordinate and undertake on-the-ground activities.

Strategy structure

Section 1 of this strategy, published here, presents general information about the BCR and the subregion, with an overview of the six elementsFootnote 9 that provide a summary of the state of bird conservation at the sub-regional level. Section 2, included in the full version of the strategy, provides more detail on the threats, objectives and actions for priority species grouped by each of the broad habitat types in the subregion. Section 3 also part of the full strategy, presents additional widespread conservation issues that are not specific to a particular habitat or were not captured by the threat assessment for individual species, as well as research and monitoring needs, and threats to migratory birds while they are outside of Canada. The approach and methodology are summarized in the appendices of the full strategy, but details are available in a separate documentFootnote 5. A national database houses all the underlying information summarized in this strategy and is available from Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Characteristics of Bird Conservation Region 6

BCR 6-Boreal Taiga Plains includes two Canadian Ecozones: the Taiga Plains in the north and the Boreal Plains in the south. In the north, BCR 6 extends from the Mackenzie Mountains and Mackenzie Delta in the northwest toward the treeline in the east. In the south, BCR 6 extends from the Rocky Mountains to Lake Winnipeg, bordered to the south by the Prairie Ecozone and to the north by the Canadian Shield. The Taiga Plains consist of broad lowlands and plateaus with a climate characterized by short, cool summers and long, cold winters. The Boreal Plains consist of low-lying valleys and plains with a climate characterized by short, warm summers and long, cold winters. Both ecozones contain gently rolling or undulating landscapes due to the influence of glaciers during the most recent ice ages. Major river systems include the Mackenzie, Peace, Athabasca and North Saskatchewan.

BCR 6 is dominated by the boreal forest, which is a forested landscape growing on a mosaic of glacial till, lacustrine deposits and peaty organic soils in poorly drained depressions interspersed with wetlands that include lakes, ponds, marshes, swamps, bogs and fens (Figure 1). The resulting forested landscape has a high diversity of site types over relatively short distancesFootnote 6(Figure 2 and Figure 3). The interaction of natural disturbance agents with landscape heterogeneity contributes to the ecological diversity of the boreal forest. Disturbance agents include fire events (varying in severity, size, frequency and pattern), as well as wind, disease and insect outbreaks (defoliators and woody tissue feeders). Forest composition within the boreal is determined by climate, slope, elevation, soil types, drainage, nutrient availability, disturbance history and successional pathways. Tree species richness in the boreal forest is relatively low, despite the large extent of this forest type.

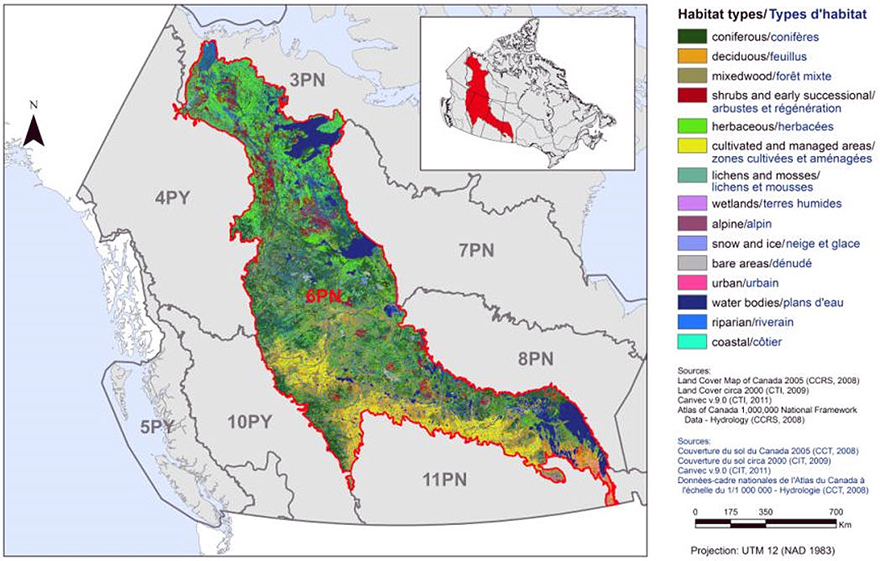

Figure 2. Land cover in BCR 6: Boreal Taiga Plains, without wetlands. Wetlands are difficult to separate without dominating the image, so they are displayed preferentially in Figure 3.

Long description for Figure 2

Map of the landcover in BCR 6 Prairie and Northern Region: Boreal Taiga Plains. The map's extent includes all of western Canada and most of the north. Also visible are a portion of Alaska and the extreme north of the United States. The borders of BCR 3 PN, 4PY, 5PY, 7PN, 8PN, 9PY, 10PY and 11PN are delineated. BCR 6 appears in colour (with a thick red line indicating its borders) while the others appear in grey. Inset in the upper right corner is a map of Canada with BCR 6 highlighted in red.

BCR 6 is approximately the shape of the letter “L” and extends from the Beaufort Sea in northern Northwest Territories and Yukon, south through the Northwest Territories, northeast British Columbia and most of Alberta, and then east through central Saskatchewan and southern Manitoba.

The various habitat types that exist in the BCR are shown on the map, and are explained in the following bilingual legend (appearing to the right of the map):

- Coniferous/conifères

- Deciduous/feuillus

- Mixedwood/forêt mixte

- Shrubs and early successional/arbustes et régénération

- Herbaceous/herbacées

- Cultivated and managed areas/zone cultivées et aménagées

- Lichens and mosses/lichens et mousses

- Wetlands/terres humides

- Alpine/alpin

- Snow and ice/neige et glace

- Bare areas/denude

- Urban/urbain

- Water bodies /plans d'eau

- Riparian/riverain

- Coastal/côtier

The remaining text in the legend provides the data sources for the map (i.e. Land Cover Map of Canada 2005 (CCRS, 2008), the projection of the map (i.e. UTM 9 (NAD 1983)) and there is a visual representation of the scale of the map.

The most common habitat types visible at this scale in BCR 6 are herbaceous and coniferous forests in the central and northern portions of the BCR, and cultivated lands in the south. There are several large waterbodies concentrated on the eastern border of the BCR. There are some patches of shrub habitat throughout and a small concentrated area of deciduous forest in the extreme southeast of the BCR. The other habitat types occur in smaller concentrations throughout the BCR, except for coastal, which is absent. Note that Wetlands are not displayed in this map, as they are displayed preferentially in the following figure.

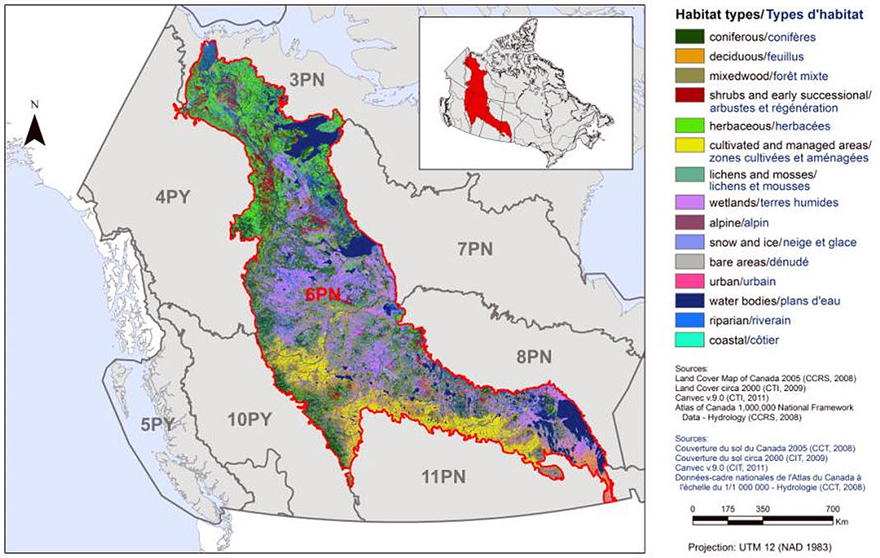

Figure 3. Land cover in BCR 6: Boreal Taiga Plains with wetlands displayed preferentially.

Long description for Figure 3

Map of the landcover in BCR 6 Prairie and Northern Region: Boreal Taiga Plains. The map's extent includes all of western Canada and most of the north. Also visible are a portion of Alaska and the extreme north of the United States. The borders of BCR 3 PN, 4PY, 5PY, 7PN, 8PN, 9PY, 10PY and 11PN are delineated. BCR 6 appears in colour (with a thick red line indicating its borders) while the others appear in grey. Inset in the upper right corner is a map of Canada with BCR 6 highlighted in red.

BCR 6 is approximately the shape of the letter “L” and extends from the Beaufort Sea in northern Northwest Territories and Yukon, south through the Northwest Territories, northeast British Columbia and most of Alberta, and then east through central Saskatchewan and southern Manitoba.

The various habitat types that exist in the BCR are shown on the map, and are explained in the following bilingual legend (appearing to the right of the map):

- Coniferous/conifères

- Deciduous/feuillus

- Mixedwood/forêt mixte

- Shrubs and early successional/arbustes et régénération

- Herbaceous/herbacées

- Cultivated and managed areas/zone cultivées et aménagées

- Lichens and mosses/lichens et mousses

- Wetlands/terres humides

- Alpine/alpin

- Snow and ice/neige et glace

- Bare areas/denude

- Urban/urbain

- Water bodies /plans d'eau

- Riparian/riverain

- Coastal/côtier

The remaining text in the legend provides the data sources for the map (i.e. Land Cover Map of Canada 2005 (CCRS, 2008), the projection of the map (i.e. UTM 9 (NAD 1983)) and there is a visual representation of the scale of the map.

Wetlands are displayed preferentially here, and they appear in moderate-high concentration over the southern 2/3 of the BCR. Still visible in high concentrations are cultivated lands in the south and herbaceous habitats in the north, as well as the large waterbodies.

In the Taiga Plains, approximately 75% of the land surface is boreal forest, with remaining areas composed of shrubland, tundra or barren land. In the north, forests are open stunted stands of white spruce, while in the south forests are primarily closed-canopy black spruce. Jack pine and Alaska paper birch grow on drier, south-facing slopes (Figure 4). In the southern area of the Slave Lowlands, white spruce and balsam poplar are found in species-rich mixed forests (Figure 5, Figure 6). The Taiga Plains is also dominated by the Mackenzie River, Canada's longest river, and the Mackenzie Delta, Canada's largest delta. The delta is composed of a complex of channels, streams and >25 000 wetlands. These small (<10 ha) and shallow (<4 m) floodplain wetlands cover up to 50% of the Delta's surface area and are highly productive.

The Boreal Plains of British Columbia are found on the flat Alberta Plateau and are composed of black spruce, tamarack and white spruce forests, peatlandsFootnote 10, and fens. The Boreal Plains of Alberta also contain the conifer-dominated forest type described above but are dominated by the Central and Dry Mixedwoods, which are composed of trembling aspen, balsam poplar, paper birch and white spruce. Jack pine dominates forests at drier sites, and balsam fir mixes with white spruce and deciduous species in moister sites. At higher elevations in the Alberta foothills, lodgepole pine is a dominant species. Moving east, the boreal forest steps down to the lower and flatter Saskatchewan Plains. In Saskatchewan and Manitoba, the Boreal Plains are composed of mid-boreal upland and lowland habitats, which are similar in composition and structure to the mixed woods of Alberta. The Manitoba Plain is dominated by lakes including Lake Winnipeg and Lake Winnipegosis. Along the southern border of the Boreal Plains, closed-canopy forests transition to open woodland and grassland habitats that have been modified by agriculture.

The northern regions of the Taiga Plains have relatively low levels of human modification with sparse human settlement and roads (only nine communities with census populations >600) and minimal industrial development. Historically, economic activity in the Taiga Plains included only fishing and wildlife hunting for both Aboriginal and commercial uses, oil and gas development in Norman Wells and Cameron Hills, and exploration in the Beaufort Sea and Mackenzie Delta, and the building of transportation infrastructure in the form of pipelines and the Dempster Highway. Proposed future development includes a 1200 kmpipeline that would deliver natural gas from reserves off the Beaufort Sea coast through the Mackenzie River Valley to markets in southern Canada and the United States.

The southern regions of the Boreal Plains in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba and in the Peace River area are characterized by agricultural deforestation (replacement of forest to non-forest land use), which began in the early 1900s and continues today. This area has been permanently modified by agricultural practices that include cultivated croplands (primarily grains), hay (tame hay) and pasture (improved and unimproved pasture). The central region and northern regions of the Boreal Plains have been modified by human settlement; forestry; oil and gas exploration and development (conventional forms that include natural gas wells and oil wells and non-conventional forms that include bitumen extraction in the form of mine sites and in-situ operations); agriculture; ranching; and water diversion and dams for water storage, hydroelectricity and industrial uses (cooling and tailings ponds). Industrial activities and associated infrastructure development-roads, railway lines, power lines, seismic lines, pipelines, oil and gas wells, harvest units, mine sites-that are used for accessing, developing and transporting people, resources and services have altered the boreal plains ecozone through habitat loss, habitat degradation and habitat subdivision (often called fragmentation). The extent and density of industrial activities and infrastructure in the boreal forest facilitates the introduction and expansion of alien (non-native) and native plant and animal species. Fire suppression has been altering natural wildfire regimes, which generate diverse ecosystem composition, structure, productivity, and habitat values and create the ecological diversity that is characteristic of the boreal forest.

Protected areas within BCR 6 include a variety of federal, provincia, and international sites. The total land area covered by protected areas in BCR 6 is 150,700 km2 or 11.0% of the BCR. Federal protected areas include Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada sites (0.08% of BCR), Environment and Climate Change Canada sites that include Migratory Bird Sanctuaries (0.01% of BCR) and National Wildlife Areas (0.0005% of BCR), and Parks Canada sites (5.4% of BCR). Provincial/territorial protected areas include Provincial and Territorial Parks (3.0% of BCR). Other designated protected areas include Ramsar sites (Wetlands of International Importance: 1.2% of BCR) and Important Bird Areas (3.8% of BCR). Important Bird Areas (IBAs) within BCR 6 range in size from approximately 1 km2 to >9 000 km2 and include Lower Mackenzie River Islands, Middle Mackenzie River Islands, Beaver Lake, Lesser Slave Lake Provincial Park, Cumberland Marshes, and Saskatchewan River Delta. RAMSAR Sites within BCR 6 range in size from 470 km2 to >9 000 km2 and include Whooping Crane Summer Range and Peace-Athabasca Delta. Parks Canada sites within BCR 6 range in size from <1 km2 to >35 000 km2 and include Nahanni National Park Reserve, Naats'ihch'oh National Park Reserve, Wood Buffalo National Park and Prince Albert National Park. Note that there is some overlap in protected areas within BCR 6 (most notably Ramsar and IBA sites that overlap Parks Canada sites). Our individual estimates above summarize the proportion of each type of protected area within BCR 6.

Figure 7. Map of protected areas and designated areas in BCR 6: Boreal Taiga Plains.

Long description for Figure 7

Map of protected and other designated areas in BCR 6 Prairie and Northern Region: Boreal Taiga Plains. The map's extent includes all of western Canada and most of the north. Also visible are a portion of Alaska and the extreme north of the United States. The borders of BCR 3 PN, 4PY, 5PY, 7PN, 8PN, 9PY, 10PY and 11PN are delineated. BCR 6 appears in colour (with a thick red line indicating its borders) while the others appear in grey. Inset in the upper right corner is a map of Canada with BCR 6 highlighted in red. BCR 6 is approximately the shape of the letter “L” and extends from the Beaufort Sea in northern Northwest Territories and Yukon, south through the Northwest Territories, northeast British Columbia and most of Alberta, and then east through central Saskatchewan and southern Manitoba.

The various types of protected areas that exist in the BCR are shown on the map, and are explained in the following bilingual legend (appearing to the right of the map):

Protected areas/Aires protégées

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada/Agriculture et Agroalimentaire Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada/Pêches et Océans Canada

- Environment and Climate Change Canada/Environnement et Changement climatique Canada

- Parks Canada/Parcs Canada

- Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada/Affaires autochtones et Développement du Nord Canada

- Provincial/Provincial

Other designated areas/autres aires désignées

- Important Bird Areas/Aires d'importance pour les oiseaux

- Ramsar/Ramsar

There is also a visual representation of scale for the map in the legend and the projection of the map (i.e. UTM 9 (NAD 1983)).

The most obvious type of protected area shown are National Parks, with 2 very large parks appearing in the centre of the BCR and several other smaller ones appearing throughout. There are also several small provincial/territorial parks throughout the BCR, and two noticeable Ramsar sites which both overlap Wood Buffalo National Park. There are perhaps a dozen small Important Bird Areas throughout as well.

Section 1: Summary of results - All Birds, All Habitats

Element 1: Priority species assessment

These Bird Conservation Strategies identify “priority species” from all regularly occurring bird species in each BCR subregion. Species that are vulnerable due to population size, distribution, population trend, abundance and threats are included because of their “conservation concern”. Some widely distributed and abundant “stewardship” species are also included. Stewardship species are included because they typify the national or regional avifauna and/or because they have a large proportion of their range and/or continental population in the subregion; many of these species have some conservation concern, while others may not require specific conservation effort at this time. Species of management concern are also included as priority species when they are at (or above) their desired population objectives but require ongoing management because of their socio-economic importance as game species or because of their impacts on other species or habitats.

The purpose of the prioritization exercise is to focus implementation efforts on the issues of greatest significance for Canadian avifauna. Table 1 provides a full list of all priority species and their reason for inclusion. Table 2 and Table 3summarize the number of priority species in BCR 6 by bird group and by the reason for priority status.

Table 1. Priority species in BCR 6, population objectives and the reason for priority status.

Accessible version of Table 1

| Bird Group | Total Species | Total Priority Species | Percent Listed as Priority | Percent of Priority List |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Landbird | 204 | 62 | 30% | 52% |

| Shorebird | 17 | 15 | 88% | 12% |

| Waterbird | 33 | 22 | 67% | 18% |

| Waterfowl | 34 | 21 | 62% | 18% |

| Total | 288 | 102 | 42% | 100% |

Note: For waterfowl, species totals include sub-species populations, as designated by NAWMP. For example, Tundra Swan (Eastern) and Lesser Snow Goose (Western Arctic) are included as species.

| Reason for Priority Listinga | Landbirds | Shorebirds | Waterbirds | Waterfowl |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| COSEWIC | 14 | 0 | 3 | 0 |

| Federal | 12 | 0 | 2 | 0 |

| Provincially listed | 10 | 0 | 3 | 2 |

| NAWMPb | - | - | - | 20 |

| National/Continental Concern | 22 | 11 | 18 | 13 |

| Regional Concern | 3 | 15 | 18 | 20 |

| National/Continental Stewardship | 16 | - | - | - |

| Regional Stewardship | 14 | - | - | - |

| Management Concernc | - | - | - | 1 |

| General Status Rank | 49 | 9 | 13 | 9 |

| Expert Opinion | 5 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

a A single species can be on the priority list for more than one reason. Note that not all reasons for inclusion apply to every bird group (indicated by “-”). Refer to Table 1 above for additional definitions regarding reasons for priority rankings.

b NAWMP indicates species ranked in the North American Waterfowl Management Plan as having Highest, High or Moderately High breeding or non-breeding conservation and/or monitoring need in the BCR.

c Management Concern indicates that a species is included as a priority because the population is above its numerical objective (waterfowl only).

Element 2: Habitats important to priority species

Identifying the broad habitat requirements for each priority species within the BCR allowed species to be grouped by shared habitat-based conservation issues and actions. If many priority species associated with the same habitat face similar conservation issues, then conservation action in that habitat may support populations of several priority species. BCR strategies use a modified version of the standard land cover classes developed by the United NationsFootnote 7 to categorize habitats, and species were often assigned to more than one habitat class.

Figure 8 provides a summary of habitat associations for priority species in BCR 6 (i.e., habitats used by priority species). Habitat associations should not be interpreted as ranked measures of habitat use, habitat ratings or habitat preference. Instead, this figure represents the total number of priority species associated with a particular habitat class. In BCR 6, for example, many priority species are associated with wetland habitats.

Figure 8. Percent of priority species associated with each habitat class in BCR 6.

Nota : La somme des valeurs est supérieure à 100 % du fait que chaque espèce peut être assignée à plus d'un habitat.

Long description for Figure 8

| Habitat Class | Percent |

|---|---|

| Coniferous | 25.83 |

| Deciduous | 35 |

| Mixed | 31.67 |

| Shrubs/Early Successional | 43.33 |

| Herbaceous | 18.33 |

| Lichens/Mosses | 2.5 |

| Cultivated and Managed Areas | 40 |

| Wetlands | 65.83 |

| Bare Area | 10.83 |

| Artificial Surfaces and Associated Areas | 7.5 |

| Waterbodies | 41.67 |

Element 3: Population objectives

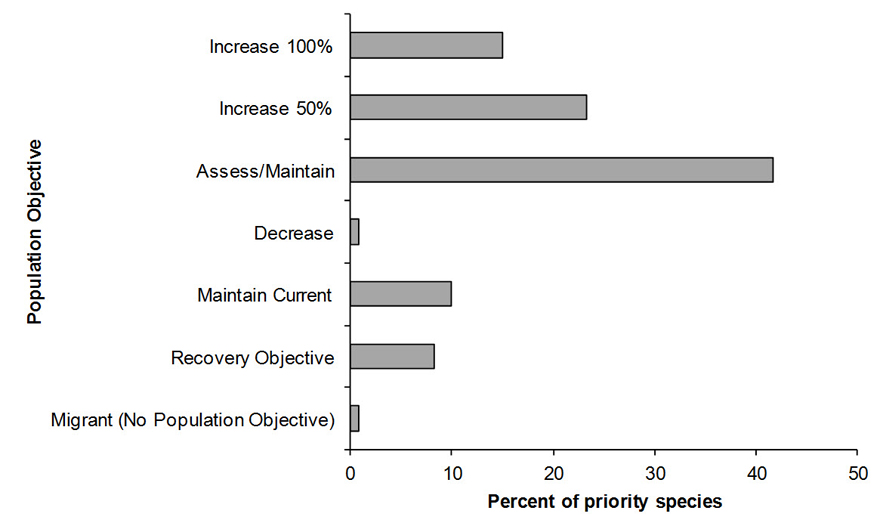

Population objectives allow us to measure and evaluate conservation success. The objectives in this strategy are assigned to categories and are based on a quantitative or qualitative assessment of species' population trends. If the population trend of a species is unknown, the objective is set as “assess and maintain”, and a monitoring objective is given. For any species listed under the Species at Risk Act (SARA) or under provincial/territorial endangered species legislation, Bird Conservation Strategies defer to population objectives in available Recovery Strategies and Management Plans. The ultimate measure of conservation success will be the extent to which population objectives have been reached over the next 40 years. Population objectives do not currently factor in feasibility of achievement, but are held as a standard against which to measure progress.

Figure 9 summarizes the proportion of BCR 6 priority species associated with each categorical population objective. The highest proportion of priority species in BCR 6 fall into the category Assess/Maintain, which can indicate a large population increase or an uncertain or unknown population trend.

Figure 9. Percent of priority species that are associated with each population objective category in BCR 6.

Long description for Figure 9

| Objective | % |

|---|---|

| Increase 100% | 15 |

| Increase 50% | 23.3 |

| Assess/Maintain | 41.67 |

| Decrease | 0.83 |

| Maintain Current | 10 |

| Recovery Objective | 8.3 |

| Migrant (No Population Objective) | 0.83 |

Element 4: Threat assessment for priority species

The threats assessment process identifies threats believed to have a population-level effect on individual priority species. These threats are assigned a relative magnitude (Low, Medium, High, Very High), based on their scope (the proportion of the species' range within the subregion that is impacted) and severity (the relative impact on the priority species' population). This allows us to target conservation actions towards threats with the greatest effects on suites of species or in broad habitat classes. Some well-known conservation issues (such as predation by domestic cats or climate change) may not be identified in the literature as significant threats to populations of an individual priority species and therefore may not be captured in the threat assessment. However, they merit attention in conservation strategies because of the large numbers of individual birds affected in many regions of Canada. We have incorporated them in a separate section on Widespread Issues in the full strategy, but, unlike other threats, they are not ranked.

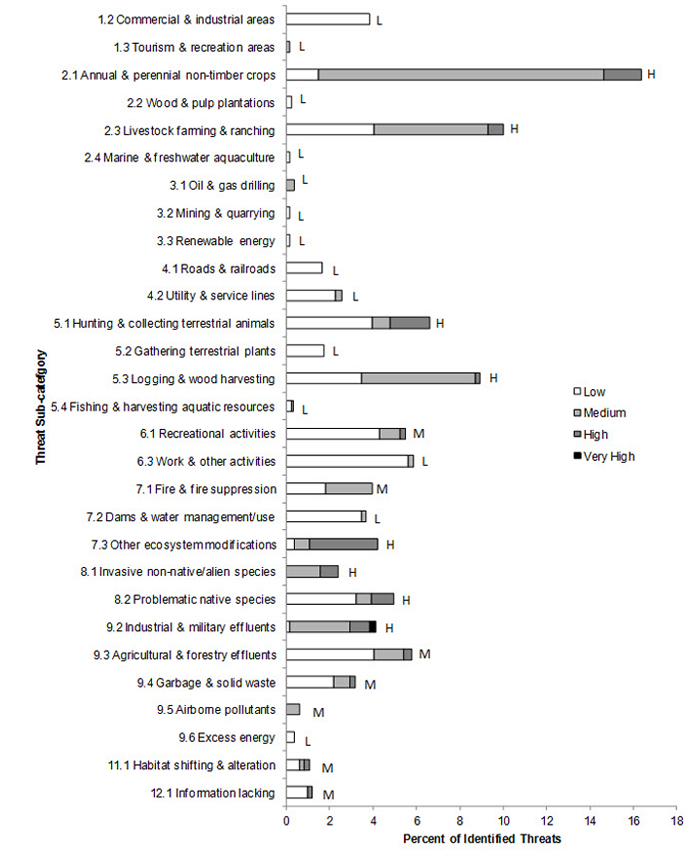

Below we briefly describe the dominant threats (medium magnitude or higher) influencing individual priority species and low-intensity threats influencing multiple species and habitats in BCR 6 (as summarized in Figure 10 below). For each threat category, we describe the primary threat and the specific activity associated with this threat in BCR 6. We also describe how the specific activity associated with the threat influences the priority species (through reduced survival or reduced reproductive success or output) or the habitat associated with the priority species (habitat loss, subdivision or degradation). In BCR 6, identified threats and their associated scope (proportion of the species range impacted by the threat), severity (the relative impact of the threat on the population within the area affected) and magnitude (combination of scope and severity) scores apply primarily to the Boreal Plains ecozone (southern portion of BCR 6). Within the Taiga Plains ecozone (northern portion of BCR 6), only 4-Transportation and Service Corridors and 8-Invasive and Other Problematic Species and Genes have been identified as threats. Although these threats have a medium and high overall magnitude in BCR 6, they are low-intensity threats in the Taiga Plains ecozone due to the low density of industrial development and human settlements within relatively small portions of the ecozone.

Dominant Threats in BCR 6 (magnitude medium or higher):

- 2 - Agriculture and Aquaculture: Primary threat is deforestation for agriculture along the southern boundary and the Peace River area of BCR 6 resulting from the permanent removal of forest stands for non-forest land use. Forest stands have been cleared for crop production, hay production and pastures. These activities result in direct habitat loss, subdivision and degradation due to the loss of specific structural attributes for bird species that depend on standing live, dead and diseased trees for nesting and foraging within the boreal transition area (transition between boreal forest and grassland biomes) and the boreal forest.

- 5 - Biological Resource Use: Primary threat is from large-scale forest harvesting, which occurs throughout the southern and central portions of BCR 6. Most forest harvesting is conducted under area-based or volume-based tenure systems. Harvested timber is sent to saw mills, pulp mills, oriented strand board operations, plywood/panel board operations, fiberboard operations and secondary manufacturing operations. Harvesting activities occur throughout the mixed wood, deciduous (hardwood) and coniferous forest types primarily during the winter months, although timber cruising, silviculture and other activities occur during the summer months. These activities result in habitat loss, subdivision and degradation because forest harvest operations cannot simulate natural disturbance regimes and natural forest dynamics. For example, forest harvesting procedures do not simulate the full range of natural disturbance agents that influence boreal forest ecosystems (e.g., fire, insects, disease, drought, floods) or the characteristic features of these natural disturbance agents (e.g., frequency, size, shape and severity). In addition, forest harvesting procedures do not simulate the stand-level structural features found in the forest canopy, forest understory and forest floor that are often associated with specific disturbance agents (e.g., standing dying or dead trees, coarse woody debris).

- 6 - Human Intrusions and Disturbance: Primary threat is recreational activities like off-road vehicles (trucks, all-terrain-vehicles in summer and snowmobiles in winter) in terrestrial habitats, and motorboats and jet-skis in aquatic habitats. These activities can disrupt territorial behaviour, pair-bonding, nesting, foraging and roosting due to interference (flushing of incubating females), noise, dust/water and potential damage to nest sites (trampling, swamping/flooding, destruction). These activities result in habitat degradation and reduced reproductive success or output. Increased access into remote areas can also result in increased mortality due to legal or illegal (poaching) hunting and collecting (5 - Biological Resource Use).

- 7 - Natural System Modifications: Primary threat is fire suppression. The combination of an active wildfire regime and a mosaic of terrain differences has generated the diversity of ecosystem composition, structure, productivity and habitat values that are characteristic of the boreal forest. The divergence between natural fire disturbance regimes and current forest management strategies has resulted in key differences between natural and managed landscapes including forest pattern (spatial and temporal distribution of seral stages across all forest types) and forest structure (presence of key structural attributes associated with ecosystem integrity). These stand- and landscape-level changes result in habitat loss, habitat degradation and reduced reproductive success or output by priority birds.

- 8 - Invasive and Other Problematic Species and Genes: Primary threat is invasive non-native/alien species in the form of vascular and non-vascular plants and invertebrates (earthworms) and vertebrates (fish) that can disrupt community dynamics. Problematic native species such as European Starlings and Brown-headed Cowbirds can result in increased competition, predation and, with the latter species, parasitism. The extent and intensity of disturbance in the southern and central portions of BCR 6 has resulted in the extensive movement of various forms of transportation (cars, trucks, all-terrain-vehicles, planes, boats) and the creation of human-disturbed habitats that may facilitate the introduction of invasive species and the transmission/dispersal of problematic native species. These activities result in habitat subdivision and degradation due to changes in plant and animal species composition and structure, predator-prey dynamics (e.g., soil arthropod prey and predators), and community/ecosystem structure and processes. These activities can also result in reduced reproductive success or output due to increased competition among species for nest sites and food, increased rates of nest predation, and increased nest parasitism on naive hosts.

- 9 - Pollution: Primary threat is the production of industrial effluents from: coal extraction methods, bitumen (oil sands) extraction methods (mining and in-situ techniques), oil and natural gas extraction sites (well sites), oil and gas transmission sites (pipelines), oil and gas production and refining sites, and mine/quarries (limestone, sand, gravel). In addition, agricultural and forestry effluents are produced as a result of agricultural pesticide and herbicide use and pulp mill discharges/emissions. These activities can result in both reduced survival of adults and juveniles and reduced reproductive success or output due to direct and indirect exposure.

- 11 - Climate Change and Severe Weather: Primary threats are changes in weather events outside the natural range of variation that alter natural disturbance agents (e.g., fire, insects, disease), tree species composition and vegetation communities. In addition, long-term changes include predicted shifts in ecosystem boundaries (gradual northward progression of tree line and replacement of southern forests with grasslands) and declines in water availability. These events are predicted to change the availability of key habitats and will affect bird distribution, occurrence and abundance within all areas of BCR 6.

- 12 - Other Direct Threats: Primary threat is lack of knowledge regarding causes of population decline. Some species such as the Lesser Scaup, Semipalmated Sandpiper and Least Sandpiper are in decline throughout the region, but reasons for decline remain unknown.

Low-Intensity Threats in BCR 6:

- 1 - Residential and Commercial Development: Primary threat is continued development of large, medium and small settlements that include housing and buildings (urban areas, suburbs, towns, villages, vacation homes, schools, hospitals, offices) and all associated commercial and industrial areas. These threats are most intense within the southern regions of BCR 6 (boreal transition area) where habitat loss, subdivision and degradation due to land clearing (forest and non-forest habitats), wetland drainage and road construction are occurring at a rapid rate.

- 3 - Energy Production and Mining: Primary threat is the continued high rate of exploration and development of both conventional oil and gas fields and non-conventional bitumen (oil sands) deposits (mining and in-situ methods) within the central regions of BCR 6. Bitumen deposits within the Boreal Plains include the Peace River, Athabasca and Cold Lake Oil Sands Deposits. Approximately 20% of all bitumen extraction occurs using open mines in the mineable oil sands area found within the Athabasca Oil Sands Area; the remaining 80% of all bitumen extraction occurs using in-situ techniques like steam-assisted gravity drainage (SAGD). Activities associated with non-conventional exploration and development at both mine and in-situ sites include the actual footprint associated with these developments and a large amount of associated infrastructure (seismic lines, pipelines, primary and secondary roads, access roads, power and utility lines and stations, railways, well sites, industrial plants, human settlements, camps). Activities associated with conventional oil and gas field exploration and development include extensive infrastructure (see above), which occurs throughout large areas of the Boreal Plains ecozone. The result is both intensive and extensive energy exploration and development that has resulted in both direct habitat loss (loss of habitat due to alienating or non-successional human disturbance activities), but also indirect habitat change. Habitat change can result in changes in habitat quality from habitat subdivision, perforation, degradation and edge effects.

- 4 - Transportation and Service Corridors: Primary threat is the creation of linear features/disturbances in the form of roads (highways, primary, secondary), railways, pipelines, seismic lines and power/utility lines. These activities occur in all habitat types during oil and gas exploration and development, winter and summer forest harvest operations, and human and industrial expansion to support the movement of people, resources and power across BCR 6. These activities result in habitat loss, subdivision and degradation due to clearing of vegetation, creation of noise and dust generated by machinery and vehicles, disruption of predator-prey dynamics, alteration of water regimes from disturbance to hydrological systems, and transmission/dispersal of invasive species.

Figure 10. Percent of identified threats to priority species within BCR 6 by threat sub-category.

Each bar represents the percent of the total number of threats identified in each threat sub-category in BCR 6 (for example, if 100 threats were identified in total for all priority species in BCR 6, and 10 of those threats were in the category 1.1 Housing and urban areas, the bar on the graph would represent this as 10%). Shading in the bars (VH = very high, H = high, M = medium and L = low) represents the rolled-up magnitude of all threats in each threat subcategory in the BCR

Note: Threat sub-categories were primarily taken from the IUCN-CMP classification of direct threats to biodiversityFootnote 8.

Long description for Figure 10

| Threat Sub-category | %Low | %Medium | %High | %Very High |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.2 Commercial and industrial areas | 3.83 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 1.3 Tourism and recreation areas | 0 | 0.15 | 0 | 0 |

| 2.1 Annual and perennial non-timber crops | 1.5 | 13.14 | 1.73 | 0 |

| 2.2 Wood and pulp plantations | 0.23 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2.3 Livestock farming and ranching | 4.05 | 5.26 | 0.68 | 0 |

| 2.4 Marine and freshwater aquaculture | 0.15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3.1 Oil and gas drilling | 0 | 0.38 | 0 | 0 |

| 3.2 Mining and quarrying | 0.15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3.3 Renewable energy | 0.15 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4.1 Roads and railroads | 1.65 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 4.2 Utility and service lines | 2.25 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 |

| 5.1 Hunting and collecting terrestrial animals | 3.98 | 0.83 | 1.8 | 0 |

| 5.2 Gathering terrestrial plants | 1.73 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5.3 Logging and wood harvesting | 3.45 | 5.26 | 0.23 | 0 |

| 5.4 Fishing and harvesting aquatic resources | 0.23 | 0.08 | 0 | 0 |

| 6.1 Recreational activities | 4.28 | 0.98 | 0.23 | 0 |

| 6.3 Work and other activities | 5.63 | 0.23 | 0 | 0 |

| 7.1 Fire and fire suppression | 1.8 | 2.18 | 0 | 0 |

| 7.2 Dams and water management/use | 3.45 | 0.23 | 0 | 0 |

| 7.3 Other ecosystem modifications | 0.38 | 0.68 | 3.15 | 0 |

| 8.1 Invasive non-native/alien species | 0 | 1.58 | 0.83 | 0 |

| 8.2 Problematic native species | 3.23 | 0.68 | 1.05 | 0 |

| 9.2 Industrial and military effluents | 0.15 | 2.78 | 0.9 | 0.3 |

| 9.3 Agricultural and forestry effluents | 4.05 | 1.35 | 0.38 | 0 |

| 9.4 Garbage and solid waste | 2.18 | 0.75 | 0.23 | 0 |

| 9.5 Airborne pollutants | 0 | 0.6 | 0 | 0 |

| 9.6 Excess energy | 0.38 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 11.1 Habitat shifting and alteration | 0.6 | 0.23 | 0.23 | 0 |

| 12.1 Information lacking | 0.98 | 0 | 0.23 | 0 |

Table 4. Relative magnitude of identified threats to priority species within BCR 6 by threat category and broad habitat class.

Accessible version of Table 4

Threats to priority species while they are outside Canada during the non-breeding season were also assessed and are presented in the Threats Outside Canada section of the full strategy.

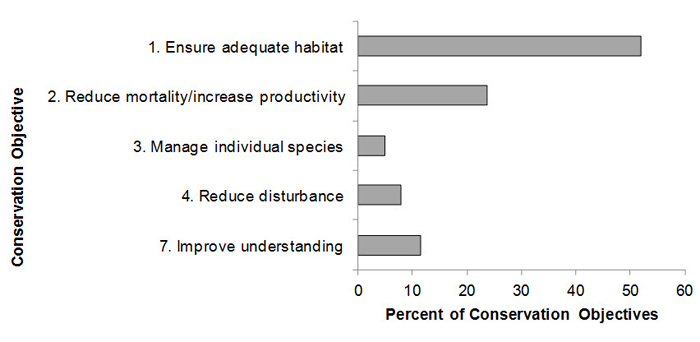

Element 5: Conservation objectives

Conservation objectives were designed to address threats and information gaps that were identified for priority species. They describe the environmental conditions and research and monitoring that are thought to be necessary for progress towards population objectives and to understand underlying conservation issues for priority bird species. As conservation objectives are reached, they will collectively contribute to achieving population objectives. Whenever possible, conservation objectives were developed to benefit multiple species and/or respond to more than one threat.

Conservation objectives were developed for threats identified for individual species and assessed at a magnitude of medium or greater. Conservation objectives fall into broad conservation categories and are identified in Figure 11. Within BCR 6, most conservation objectives fall into the conservation category Ensure Adequate Habitat, suggesting that objectives associated with maintaining the availability of suitable habitat for priority species are of primary importance.

Figure 11. Percent of all conservation objectives assigned to each conservation objective category in BCR 6.

Text descritption for Figure 11

| Conservation Objective | % |

|---|---|

| 1. Ensure adequate habitat | 51.86 |

| 2. Reduce mortality/increase productivity | 23.76 |

| 3. Manage individual species | 5.03 |

| 4. Reduce disturbance | 7.81 |

| 7. Improve understanding | 11.54 |

Element 6: Recommended actions

Recommended actions indicate on-the-ground activities that will help to achieve the conservation objectives (Figure 11). Actions are strategic rather than highly detailed and prescriptive. Whenever possible, recommended actions benefit multiple species and/or respond to more than one threat. Recommended actions defer to or support those provided in recovery documents for species at risk at the federal, provincial or territorial level, but will usually be more general than those developed for individual species.

Conservation actions were developed for identified conservation objectives. Conservation actions fall into specific conservation action categories and sub-categories and are identified in Figure 12. Within BCR 6, most conservation actions fall into the conservation sub-categories Site/Area Management (management of protected areas and other resource lands for conservation) and Site/Area Protection (establishing or expanding public or private parks, reserves and other protected areas).

Figure 12. Percent of recommended actions assigned to each sub-category in BCR 6.

“Research” and “monitoring” refers to specific species where additional information is required. For a discussion of broad-scale research and monitoring requirements, see the Research and Population Monitoring Needs section in the full strategy.

Long description for Figure 12

| Conservation Action | percent |

|---|---|

| 1.1 Site/area protection | 12.35772 |

| 1.2 Resource and habitat protection | 6.759582 |

| 2.1 Site/area management | 12.6597 |

| 2.2 Invasive/problematic species control | 1.55633 |

| 2.3 Habitat and natural process restoration | 2.9036 |

| 3.1 Species management | 1.347271 |

| 4.2 Training | 9.105691 |

| 4.3 Awareness and communications | 3.600465 |

| 5.1 Legislation | 4.018583 |

| 5.2 Policies and regulations | 11.31243 |

| 5.3 Private sector standards and codes | 10.80139 |

| 5.4 Compliance and enforcement | 0.766551 |

| 6.2 Substitution | 1.626016 |

| 6.3 Market forces | 2.113821 |

| 6.4 Conservation payments | 1.022067 |

| 7.3 Conservation finance | 0.418118 |

| 8.1 Research | 12.14866 |

| 8.2 Monitoring | 5.481998 |