Portage Island National Wildlife Area Management Plan: chapter 3

3 Management challenges and threats

3.1 Tourism

Coastal boating and sea kayaking are rapidly growing recreational activities. Increasingly unique and previously inaccessible areas are being promoted for day adventure opportunities, either for guided tours or in tourism promotional material. The waters around Portage Island are frequented by boaters during the summer months. The series of coastal islands with their easily accessible sand beaches are enticing to tourists. Evidence of temporary picnicking and camping on the island suggests some use over the summer months. However, most visits are restricted to the coastal beaches, and few people wander into the interior, primarily due to the abundance of mosquitoes on the island.

3.2 Dogs and plovers

Short visits to Portage Island by picnickers have little lasting impact on the habitat. However, humans and accompanying family pets, primarily dogs, cause significant disturbance to ground-nesting birds and are especially harmful to Piping Plover. Dogs and cats are therefore prohibited on Portage Island National Wildlife Area (NWA).

3.3 Shellfish and aquaculture

The potential further development of shellfish aquaculture sites in Gammon Bay adjacent to Portage Island NWA is a concern, due to disturbance and potential for conflicts that may arise if birds were to feed or roost at the aquaculture site (Figure 7). Severe storms can damage infrastructure, resulting in deposition of nets and related hardware on the island. Such materials can be difficult and costly to remove, damaging to habitat, and hazardous to beach-dwelling shorebirds, especially Piping Plovers. Shellfish from this area are in high demand, and one product is marketed as "Portage Island Oysters."

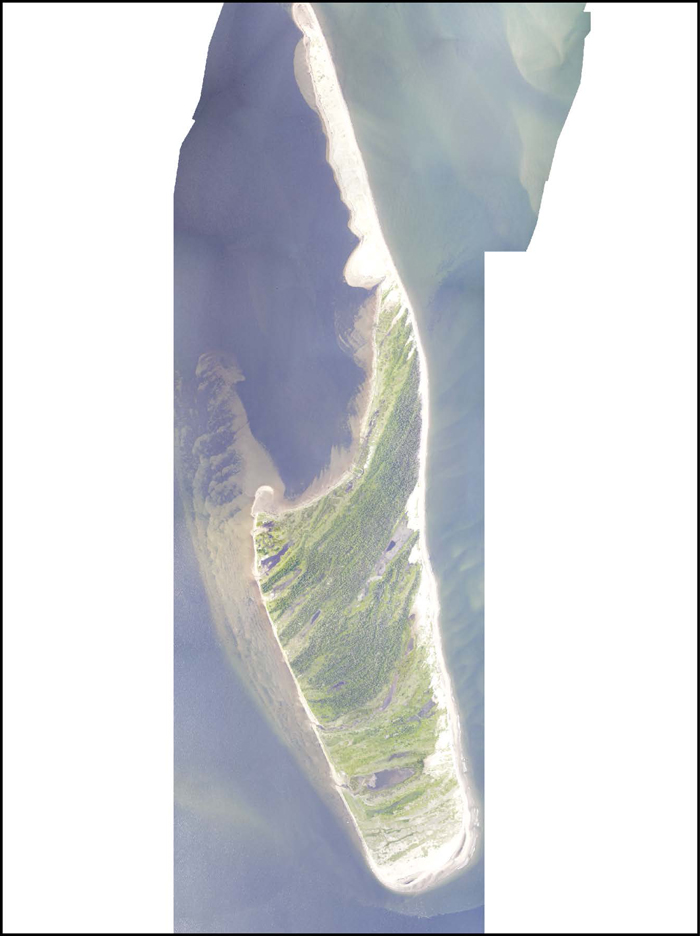

Photo: A. Kennedy © Environment Canada, 2005

3.4 Habitat change

Coastal dune plant succession and dune erosion are the main habitat changes taking place at Portage Island NWA. As the dunes age, they will become increasingly vegetated with ericaceous and eventually forested habitat. This succession will be heavily influenced by erosion and flooding events that either create new dune and beach habitat or kill upland plants from flooding by salt water. Extreme weather events in recent years and significant loss of forested habitat along the island’s east side suggest that the balance between island growth and loss may be compromised. At present, the rapid loss of forested habitat cannot be easily or quickly compensated by Portage Island’s expansion to the south.

The appearance of Portage Island is expected to change in the future, with more open sand dunes, more dunes vegetated with Marram Grass, and a reduction in the area of Jack Pine forest.

3.5 Predicted climate change context

The climate at the mouth of the Miramichi River, generally cool with a mean annual temperature of 4.7ºC, is moderated by the marine environment of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Summers are generally warm inland but slightly cooler along the coast. Midsummer temperatures range from average lows of 9-13ºC with daytime highs of 22-25ºC. The islands, including Portage Island, flanking the mouth of the Miramichi River are considered as at "moderate" risk from sea-level rise.

Portage Island NWA is very susceptible to impacts from severe storms, and such events will likely be compounded by sea-level rise ( Daigle 2012 ). Fishing shacks once present in the mid-20th century on Gammon Point, the spit at the northwest end of the island, have been levelled by storm surges and subsequently buried by sand. Suitable nesting areas for the endangered Piping Plover are being dramatically altered or are disappearing at the northern bar due to continual erosion. However, deposition of sand at the southern end is increasing the size of that area of the island and providing more open dune habitat. This change in the physical nature of the island has impacted plants that occur there. Some sites of climax species, such as Hudsonia (Hudsonia ericoides), which may be hundreds of years old, have been destroyed by recent flooding brought on by storms. Much of the forest along the eastern side of the island has been killed by salt spray and shifting dunes (Figure 8).

Coastal erosion and subsequent habitat loss, often in concert with habitat gain through sand deposition, is part of the unique character of Portage Island (Table 5). The eastern shore of Portage Island has suffered severe coastal erosion over the past 40 years, although it is uncertain whether this erosion is part of typical cyclic occurrences or more severe weather influenced by climate change. Most noticeable is the almost complete loss of the largest linear pond on the island. Through erosion and inundation by sand, its length has been reduced by 250 m from 1971 to 2011. The southern end of the island is being enlarged by sand deposition, but this has not kept pace with the overall erosion rate. When gazetted in 1979, Portage Island was 451 hectares in size, compared with 348 hectares today. A sea-level rise of 90 cm (+/- 38 cm) has been predicted for the mouth of the Miramichi by 2100 ( Daigle 2012 ). Island loss due to severe storm surges is of concern as well. Should Portage Island experience a 0.5 m increase in water level over a "large tide," more than 50% of the island would be covered (Figure 9) ( Miramichi River Environmental Association 2007 ). Canadian Wildlife Service Atlantic Region has established a Piping Plover habitat monitoring program for the eastern coast of New Brunswick to quantify changes in habitat related to storm surge and sea-level rise (Figure 10).

| Year | Size in hectares (acres) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 451 (1114) | Map of Portage Island dated 17 March 1870 |

| 1979 | 451 (1114) | As gazetted in 1979 |

| 2000 | 348 ha (860) | Service New BrunswickFootnote1of table 5 |

Photo: C. MacKinnon © Environment Canada, 2000

Map: © Environment Canada, 2014

Long description for Figure 9

Figure 9. A map of Portage Island on which is indicated the ordinary shoreline and the shoreline under potential future storm surge conditions. The map scale is in hundreds of metres. Further details can be found in the preceding/next paragraph(s).

Photo: © Environment Canada, 2011

3.6 Contaminated sites

The operational lighthouse station that was once supported on Portage Island raises concerns with respect to residual contaminants. As part of scheduled maintenance, lighthouse stations were scraped and painted on a yearly basis, frequently using lead-based paints. Mercury floats were often used to support the light within the tower. Phase I and II environmental site assessments have been conducted on Portage Island targeting these concerns, with minimal traces of lead and mercury found near the old lighthouse sites ( SNC-Lavalin 2002 ).