Terrestrial species at risk: COSEWIC summaries for eligible species, January 2017, part 1

Part 1: Bailkal Sedge to Mountain Crab-eye

1. Baikal Sedge

Photo: © Ryan Batten

- Scientific name

- Carex sabulosa

- Taxon

- Vascular Plants

- COSEWIC Status

- Special Concern

- Canadian range

- Yukon

Reason for designation

In Canada, this species is restricted to 16 sites in 10 dune fields in the southwest Yukon. Since the last assessment, 11 new subpopulations have been found and two serious threats have been negated, which reduces the known risk to the Canadian population. However, natural succession is leading to habitat loss; this is exacerbated by fire suppression. Other threats driving recent declines include off-road recreational vehicle use and habitat loss through housing development. Exotic, invasive plants are a serious potential threat resulting in dune stabilization and competitive exclusion.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

The Baikal Sedge, Carex sabulosa, is a tufted perennial plant with long rhizomes. As the flowers mature, the slim stems arch and droop, and the heavy fruiting heads sometimes touch the ground.

Baikal Sedge occurs in a dune ecosystem that was once widespread but is no longer common in Canada; the potential sites for the plant are restricted. In addition, the subpopulations are of probable genetic interest because they are disjunct from, and at the eastern periphery of, a fragmented range that extends from central Asia to southwestern Yukon. Baikal Sedge is an important species in the stabilization of dunes.

Distribution

Baikal Sedge is found in the sands of central Asia, from Kazakhstan through southern Siberia and western China to Mongolia. Over 3000 km away in North America, it occurs in one dune field in west-central Alaska and in 10 dune fields (16 subpopulations) in a small region of the southwestern Yukon. Two additional occurrences have not been relocated, despite searches, and are considered extirpated.

Source: COSEWIC 2016. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Baikal Sedge Carex sabulosa in Canada.

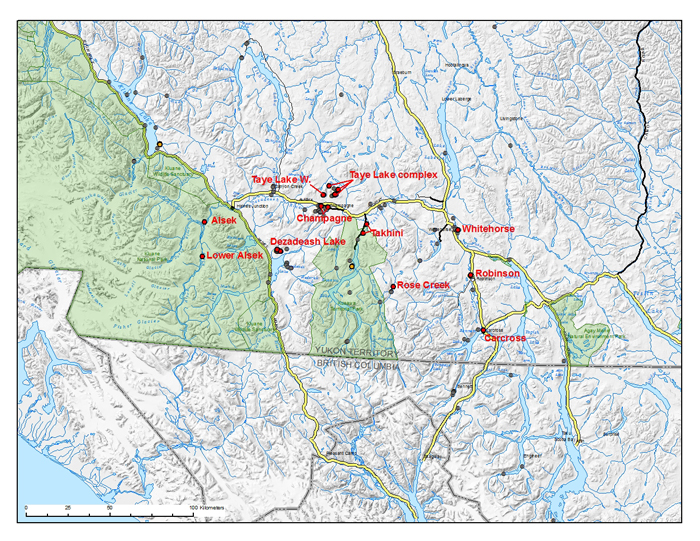

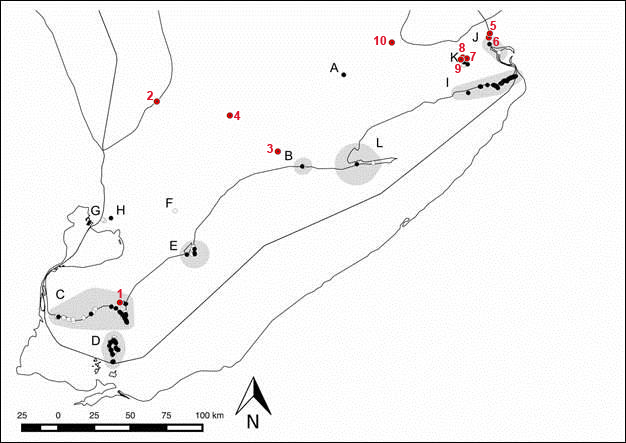

Long description for map showing the distribution of Baikal Sedge

Map showing the distribution of Baikal Sedge (Carex sabulosa) in southwestern Yukon, Canada. Known locations are indicated with red dots, historical occurrences are presumed extirpated and indicated with orange dots and sites that were searched in 2009 but presence was not detected are indicated with grey dots. In Canada, the Baikal Sedge is restricted to sixteen sites in ten active dune fields in the southwestern Yukon, from Kluane National Park Reserve west to Whitehorse, and south to Dezadeash Lake and Carcross.

Habitat

Baikal Sedge occurs on the accumulating surfaces of active and semi-stabilized dunes, where it is often the only prominent vascular plant species. In the Yukon, these dunes are remnants of much larger dune fields that were present at the end of the Pleistocene. Most of the ancient dunes are now stabilized and covered in forest or grassland. Many of the extant Baikal Sedge sites are limited to small blowouts in dunes without large supplies of open sand.

Biology

The biology of Baikal Sedge has not been studied. It is evident, however, that this species can withstand cold, desiccating winds and accumulating sand. Reproduction is primarily vegetative through rhizomes; seed production is often limited. In the Yukon, a smut fungus, Planetella lironis, attacks developing fruits (seed-like achenes); the smut's effect on reproductive success remains unknown.

Baikal Sedge fruiting head Photo: © Ryan Batten

Population Sizes and Trends

The largest subpopulation is found near the confluence of the Kaskawulsh and Dezadeash rivers in Kluane National Park and Reserve. There are an estimated 2.5 to 3 million ramets (tufts) at this site. The remaining 15 subpopulations have an estimated total of 1,053,000 ramets, giving an estimated Canadian population of roughly 3.5 to 4 million ramets.

Population trends at all but the Carcross dune systems have probably remained roughly stable in recent years, although there has probably been a small decline because of natural succession and dune stabilization. Baikal Sedge has probably declined more substantially at the Carcross dunes; a decline based both on an apparent reduction in active dunes and on an apparent decrease in sedge extent on active dunes.

Threats and Limiting Factors

Natural vegetation succession is a limiting factor to Baikal Sedge persistence, through dune stabilization. This process is of concern at the largest (Alsek) subpopulation at the confluence of the Kaskawulsh and Dezadeash rivers. Fire suppression allows for more rapid vegetation succession and this threatens several of the subpopulations. There is an apparent loss of dune habitat as a result of stabilization at Carcross as well. Invasive plants that accelerate dune stabilization pose a significant future threat.

The threat of disturbance from off-road recreational vehicles is of most concern at the Carcross dunes, but also to a lesser extent at the Takhini River (south) dune system. Excessive off-road vehicle use not only damages the plants at the surface, but also compacts the sand and eliminates the clones.

Development of dunes for residential lots or tourism operations is of concern behind the Bennett Lake beach at Carcross.

Protection, Status and Ranks

Baikal Sedge is listed as Threatened under the federal Species at Risk Act in Canada. Critical Habitat has only been identified within Kluane National Park and Reserve, where it also receives some measure of protection under the Canada National Parks Act. The Takhini River dune system is protected from development in the as-yet-undesignated Kusawa Territorial Park; a draft management plan has recently been developed for this park. The subpopulations northeast of the Klondike Highway at Carcross occur within a territorial park reserve; however, off-road vehicles use this site regularly, and this activity continues to reduce the area of occupancy of the sedge. Recovery at this site is not possible given the current level of use. Elsewhere, Baikal Sedge occurs on Crown (Commissioner's) land where only a special federal order can protect the species under the Species at Risk Act. In the NatureServe ranking system, it is ranked G5 (Secure) globally, N2 (Imperilled) nationally and S2 in Yukon.

2. Bear's-foot Sanicle

Photo: © Matthew Fairbarns

- Scientific name

- Sanicula arctopoides

- Taxon

- Vascular Plants

- COSEWIC Status

- Threatened

- Canadian range

- British Columbia

Reason for designation

This perennial wildflower occurs in Canada only along a 30 km stretch of coastline in extreme southeast Vancouver Island. While this wildflower can live more than 10 years, it flowers and fruits once and then dies. It occupies small areas of remaining meadow habitat, which is being modified by invasion of exotic plants. Several new sites, discovered since the species was last assessed, have reduced the risk to this plant. Most of the Canadian population occurs at one site, which is also threatened by grazing by an expanding non-migratory, newly resident Canada Goose population. Severe trampling by humans also affects a few sites. Many of the known subpopulations have relatively few individuals and may not persist.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Bear's-foot Sanicle is a tap-rooted, low-growing, herbaceous perennial wildflower. Its basal leaves, which are deeply lobed and sharply toothed, form a compact rosette. The inflorescences are compact with many bright yellow small flowers that produce fruit with hooked bristles. Bear's-foot Sanicle is one of over 50 nationally rare species that are restricted (in Canada) to Garry Oak and associated ecosystems in southern Vancouver Island and the adjacent Gulf Islands.

Distribution

In Canada, Bear's-foot Sanicle occurs only in a 30 km length of shoreline in the vicinity of Victoria, British Columbia. Bear's-foot Sanicle is known from nine extant subpopulations in Canada. In the United States it ranges from the San Juan Islands of Washington State, south along the coast of Washington and Oregon, to California. Subpopulations in Washington State are very small and are imperilled. The nearest US subpopulations (San Juan Islands) are approximately 25 km from the nearest Canadian subpopulation and separated by several kilometres of open ocean, making dispersal between these sites unlikely.

Source: COSEWIC 2015. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Bear's-foot Sanicle Sanicula arctopoides in Canada.

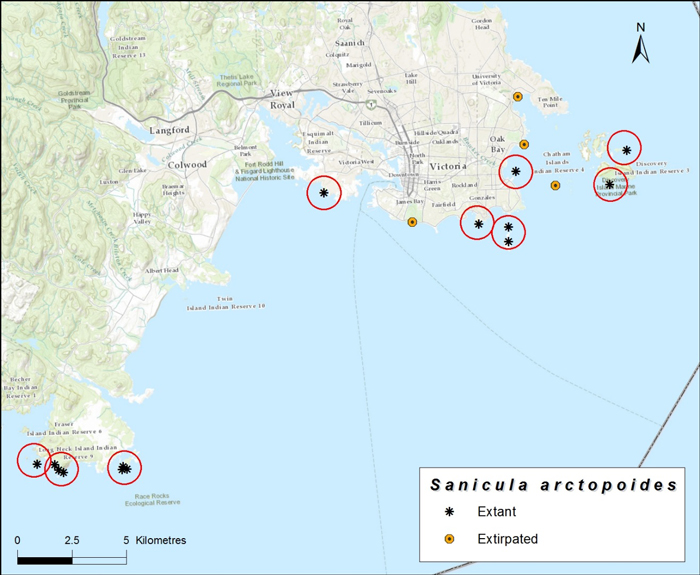

Long description for map showing the distribution of Bear's-foot Sanicle

Map showing the distribution of Bear's-foot Sanicle (Sanicula arctopoides) in Canada, each circle represents one location. Less than 1% of the species range lies within Canada, the Canadian distribution is known from a 30 km long area along the shores of Vancouver Island, centered on Victoria.

Habitat

In Canada, Bear's-foot Sanicle is restricted to drought-prone maritime meadows at low elevations along shorelines. The plants experience wide seasonal fluctuations in water availability, with abundant rains typically beginning in mid-autumn, and continuing through autumn and winter, ceasing with the onset of the summer drought, when Bear's-foot Sanicle becomes dormant. The dry summer conditions discourage the growth of native trees and shrubs although the exotic invasive Scotch Broom is often present. Bear's-foot Sanicle usually occurs in vegetation dominated by low (< 20 cm tall) forbs and grasses. A few native species may be relatively common in the vegetation but exotic, invasive forbs and grasses tend to dominate.

Biology

Bear's-foot Sanicle is a perennial species with a monocarpic life cycle, meaning that after it flowers and fruits the whole plant dies. Germination occurs as early as December and may continue into March. Plants tend to reach maximum annual size by April or May and the small non-reproductive plants either die or become dormant in late May or early June as the summer drought deepens. Larger, older plants flower in March or April and produce ripe fruits by mid- to late June. The small dry fruits are covered with hooked bristles, which aid in dispersal, by catching on the fur and feathers of passing animals as well as on clothing. Dormant plants resprout in October or November and grow slowly through the winter months. Most seeds germinate in the first fall after dispersal, or else perish in the soil. Most seedlings live only a few months and the survivors grow slowly. Generation time is estimated at 14 years.

Population Sizes and Trends

The total Canadian population is currently estimated at approximately 2,900 mature individuals. There are nine extant subpopulations in Canada. Five of the nine subpopulations had fewer than 50 mature individuals. Approximately 85% of the Canadian population occurs in one subpopulation, on Trial Islands. The only other Canadian subpopulation that consistently produces > 100 mature individuals is at Harling Point, a headland on Vancouver Island close to Trial Islands. Habitat information suggests there has probably been a decline in the number and size of the total Canadian population over the past 3 generations (42 years). Bear's-foot Sanicle is critically imperilled in Washington--there is little likelihood of dispersal from US populations to establish new populations in Canada.

Threats and Limiting Factors

The major limiting factor across the Canadian range of Bear`s-foot Sanicle is its restriction to a rare habitat type within a tiny area in Canada. The primary threat to the species is a continuing decline in habitat quality because of the increasing abundance of invasive species. Other major threats include herbivory by the increasing size of the non-migratory and newly resident population of Canada Geese at several Canadian locations of Bear's-foot Sanicle, construction and operation activities, trampling in sites that experience high levels of human visitation and a projected decline in the suitability of occupied habitat as a result of climate change.

Protection, Status and Ranks

Bear's-foot Sanicle is listed as Endangered on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) and afforded measures of protection under that legislation. It is not protected under BC provincial species at risk legislation. Bear's-foot Sanicle is ranked globally secure but critically imperilled in Canada. Bear's-foot Sanicle is also critically imperilled in Washington State and has not been ranked in Oregon or California, where it also occurs.

3. Blue-grey Taildropper

Photo: © Kristiina Ovaska

- Scientific name

- Prophysaon coeruleum

- Taxon

- Molluscs

- COSEWIC Status

- Threatened

- Canadian range

- British Columbia

Reason for designation

This small, slender blue-coloured slug is only found in western North America where it lives in the moist layer of fallen leaves and mosses in mixed-wood forest. In Canada, it is confined to the southeastern tip of Vancouver Island within the Coastal Douglas-fir biogeoclimatic zone and where it transitions into the Coastal Western Hemlock biogeoclimatic zone. These habitats are declining in extent and what remains is becoming increasingly fragmented. Fifteen subpopulations are currently known, an increase that has resulted in a change of status. A continuing decline in habitat quality is expected due to natural ecosystem modification and competition with invasive species as well as droughts and severe weather events from climate change.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Blue-grey Taildropper (Prophysaon coeruleum) is a small slender slug (Arionidae: Anadeninae) with adults measuring between 20 - 40 mm in length. Distinguishing features include solid blue-grey colour without stripes and distinct, parallel grooves and ridges on the back and sides of the tail. As in other taildroppers (genus Prophysaon), a thin, oblique constriction or impressed line is usually visible on the tail at the site where autotomy (self-amputation) takes place, if the slug is attacked by a predator.

Blue-grey Taildropper may act as a dispersal agent for spores of fungi that form symbiotic associations with tree roots, thereby performing an important ecological function.

Distribution

Blue-grey Taildropper is endemic to western North America, where it occurs from southwestern British Columbia south through the Puget Lowlands and Cascade Range of Washington State into Oregon and northern California; a disjunct population exists in northern Idaho. In Canada, Blue-grey Taildropper is documented only from southern Vancouver Island, where 15 subpopulations are known. All but two records are from within the Capital Regional District. In 2013, the species was found in the North Cowichan District, approximately 28 km north of the nearest record, followed by a second observation in the general area in 2015.

The estimated range (extent of occurrence) of Blue-grey Taildropper in Canada has increased from 150 km2 to 658 km2 since the previous status report, reflecting increased search effort over the past decade. Undocumented localities probably exist, but it is highly unlikely that there would be large additions to their range given the extensive search effort on southern Vancouver Island; hundreds of localities have been searched for terrestrial gastropods on Vancouver Island and the adjacent coastal mainland of British Columbia.

Source: COSEWIC 2016. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Blue-grey Taildropper slug Prophysaon coeruleum in Canada.

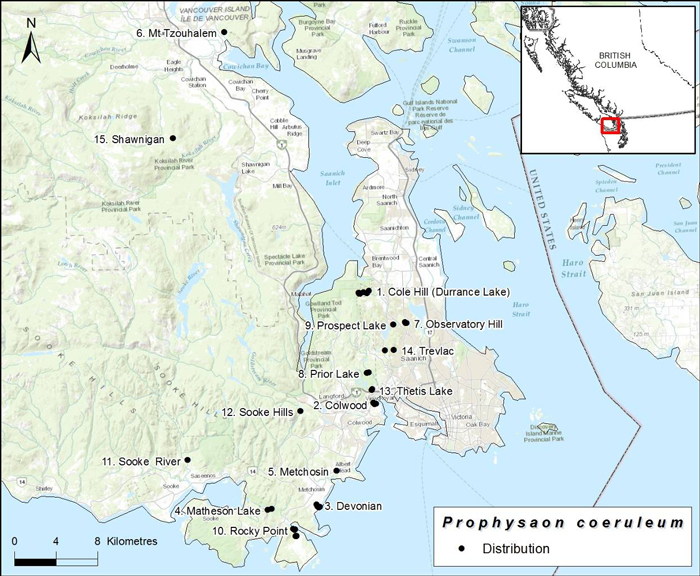

Long description for map showing the Canadian distribution of the Blue-grey Taildropper

Map showing the Canadian distribution of the Blue-grey Taildropper (Prophysaon coeruleum), known only from Southern Vancouver Island, names of subpopulations are shown and numbered and occur within 1km of each other.

Habitat

Blue-grey Taildropper inhabits low-elevation (< 250 m above sea level) mature or maturing second growth mixed-wood forest (>60 years old) on the drier southeastern tip of Vancouver Island within the Coastal Douglas-fir biogeoclimatic zone and where it transitions into the Coastal Western Hemlock biogeoclimatic zone. These habitats are declining rapidly in extent and becoming seriously fragmented due to urban and rural development. The Coastal Douglas-fir biogeoclimatic zone is one of the most disturbed ecosystems of British Columbia. This zone contains several rare and provincially listed Douglas-fir, Garry Oak and Arbutus ecosystems, where Blue-grey Taildropper has been found, although it is not restricted to these habitats. The slugs are patchily distributed within the landscape. Small forest gaps and woodland habitats may be favoured over deeper forest at the northern limits of the species' distribution, as they capture the sun and provide relatively warm forest floor conditions. Availability of suitable moist refuges, such as provided by abundant coarse woody debris and/or a deep moss layer, is thought to be important.

Biology

Blue-grey Taildropper appears to have an annual life cycle, maturing and reproducing within one year and overwintering as eggs. In British Columbia, juveniles have been observed in April - June, while almost all adults have been found in September - December; one adult was found in March, indicating successful overwintering by at least some adults.

Blue-grey Taildropper feeds extensively on fungi. A variety of vertebrate and invertebrate predators, native and introduced, prey on slugs and probably also on this species. Blue-grey Taildropper is capable of self-amputation of the tail, an adaptation that is an effective anti-predation mechanism against some predators. Blue-grey Taildroppers are thought to have very limited dispersal capabilities, in the order of tens to hundreds of metres per generation.

Population Sizes and Trends

There are no reliable population estimates but rough estimates at four sites in one year resulted in a minimum of 50 - 125 adults per ha. Extrapolation of these densities to known occupied areas results in a population size of 1,800 - 4,500 adults. The total Canadian population, including undiscovered sites, is probably <10,000 individuals. However, the species is patchily distributed in the habitat, making population size estimates difficult. Blue-grey Taildropper was first documented from British Columbia only in 2002, and nothing is known of its long-term population fluctuations or trends. During field verification surveys in autumn 2014, the species was found at six of 18 known sites revisited. While the habitat at most sites remained unchanged, it had deteriorated at six sites where the species was not found due to encroachment by invasive plants, recreational activities, and/or development. Blue-grey Taildropper occurs in two habitat patches that are smaller than 20 ha, the minimum thought to be required for long-term viability, and three others are in heavily fragmented rural landscapes. The remaining ten subpopulations are in habitats with at least some connectivity to larger areas of forest.

Threats and Limiting Factors

Blue-grey Taildropper exists at the northern extremity of its geographic range in southwestern British Columbia. Low dispersal ability and requirements for moist habitats limit the speed with which the slugs can colonize new habitats or habitat patches from which they have become extirpated.

Main threats to Blue-grey Taildropper are from natural ecosystem modification by non-native invasive plants, competition and predation by introduced invertebrates, and from droughts associated with climate change and severe weather. Introduced invasive plants are prevalent at many Blue-grey Taildropper sites on Vancouver Island and deteriorate habitat quality by displacing native plants and altering the microclimate and possibly food supply for slugs. Non-native gastropods and other invertebrates, such as ground beetles (Coleoptera: Carabidae) pose a threat through predation and through competition for food and shelter. Prolonged and more frequent droughts are expected to reduce survivorship and length of time available for foraging and growth. Such effects can be expected to be particularly severe in degraded habitat patches that may lack microhabitats suitable for refuges. Other widespread threats include recreational activities and expanding housing and urban developments that contribute to habitat loss and degradation.

Protection, Status and Ranks

Blue-grey Taildropper is listed as endangered on Schedule 1 under the Species at Risk Act. Globally, the species is ranked as "vulnerable - apparently secure", G3G4 (rounded global status G3). Blue-grey Taildropper is on the provincial Red List of species at risk, which includes species that are extirpated, endangered, or threatened in British Columbia, and is ranked as "critically imperilled" (S1).

Most subpopulations are either entirely or partially on federal lands (Department of National Defence, National Research Council), in Capital Regional District Parks and Trails System, or in municipal parks and are protected from land conversions at least over the short term. Three subpopulations and a portion of a fourth one are within rural private lands. Additional sites may exist on private lands.

4. Colicroot

Photo: © Jennifer Anderson

- Scientific name

- Aletris farinosa

- Taxon

- Vascular Plants

- COSEWIC Status

- Endangered

- Canadian range

- Ontario

Reason for designation

This perennial herb is restricted to remnant, disturbance-dependent prairie habitats in southwestern Ontario. It continues to decline in the face of multiple threats, including habitat modification, invasive species, and browsing by deer. Prairie habitat, for example, naturally transitions to less suitable habitat types in the absence of periodic disturbance (e.g., fire), and its quality and extent are also vulnerable to ongoing urban and industrial development. Recent construction of a new transportation corridor caused the removal of more than 50% of all mature plants in the Canadian population and loss of habitat. Although plants have been transplanted from the transportation corridor to nearby restoration sites, it is too early to know whether these relocated subpopulations will be self-sustaining so they cannot yet be considered to contribute to the population.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) is a herbaceous perennial in the Bog Asphodel Family (Nartheciaceae). It has a basal rosette of yellowy-green, lance-shaped leaves. In early summer, it produces an upright flowering stalk about 40 - 100 cm tall, with a spike of small, white flowers with a mealy texture. After flowering, the dried petals remain on the fruit capsules. Colicroot has been used to treat menstrual and uterine problems and contains active chemicals that may have hormonal properties.

Distribution

In Canada, Colicroot is restricted to four geographic regions in southwestern Ontario: the City of Windsor-Town of LaSalle; Walpole Island; near Eagle (Municipality of West Elgin); and is inferred to be extirpated near Turkey Point (Haldimand-Norfolk County).

Source: COSEWIC 2015. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on Colicroot Aletris farinosa in Canada.

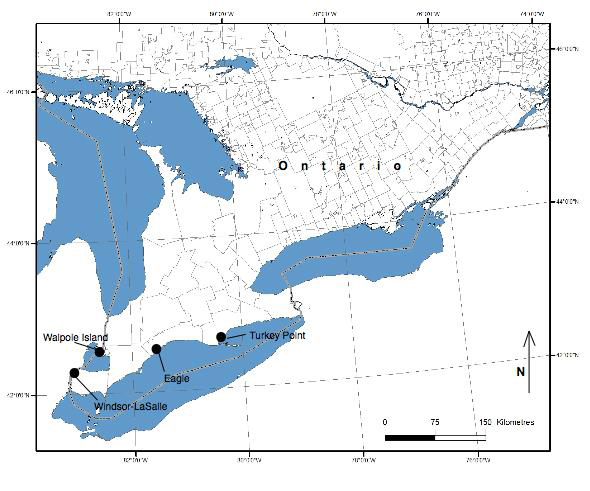

Long description for map showing the distribution of Colicroot

Map showing the distribution of Colicroot (Aletris farinosa) in Canada, indicating four regions with extant subpopulations. Colicroot has an extremely restricted geographic range in Canada and has never been observed outside of southwestern Ontario. Current confirmed occurrences are the City of Windsor and the adjacent Town of LaSalle; Walpole Island (in Lake St. Clair); and near Eagle, in the municipality of West Elgin, Ontario. Seven subpopulations with 35 patches are confirmed extant, and one patch in one subpopulation is presumed extirpated.

Habitat

Colicroot grows in open, moist, sandy ground associated with tallgrass prairie habitats and damp sandy meadows. It is currently found in prairie remnants, old fields, utility corridors, and woodland edges. It is intolerant of shading by surrounding vegetation. For habitat to remain suitable, some type of disturbance must occur to keep vegetation open, short, and sparse. Historically, fire probably maintained habitat but more recently, human activities, such as periodic mowing, cultivation, and the use of walking and bicycling trails, create disturbance in Colicroot habitat but keep habitat only marginally suitable. Loss of habitat due to succession is the number one cause of the decline of Colicroot and is an urgent threat. Habitat has also been lost to urban development, to construction of the Right Honourable Herb Gray Parkway (Parkway), and to conversion to agricultural use.

Habitat in Parkway restoration sites and at some sites on Walpole Island is currently maintained by controlled burning and manual removal of woody and invasive species. However, habitat has been lost in Natural Heritage Areas and a provincial nature reserve, showing that Colicroot is not protected if management is not adequate. It is unknown whether habitat can be restored from a completely wooded state.

Biology

Colicroot is perennial and some plants probably live for decades. The time required to reach maturity from seed is unknown but is likely more than one year and probably depends on site conditions. It is unknown how long seeds remain viable or if there is a seed bank in the soil. In addition to sexual reproduction, vegetative reproduction is possible but infrequent from buds on the rhizome. Thus, some plants in a patch may not be genetically distinct individuals. Flowers are insect-pollinated, mainly by bumblebees and solitary bees. It is unknown whether the flowers are self-fertile. It has been suggested that Colicroot may have mycorrhizal requirements because, until recently, most attempts to transplant the species were unsuccessful. However, greenhouse tests found no evidence that mycorrhizal fungi confer an advantage. Colicroot has no specialized structures to assist dispersal. Flowering stalks are frequently eaten by deer or other herbivores, and the leaves are sometimes eaten by insects. It is unknown whether herbivores can disperse seeds through the gut.

Population Sizes and Trends

Total abundance in 2014 was between 14,000 to 15,000 plants, with ~14,600 the best available estimate. Over half of the individuals in the Canadian population are the results of transplants and those propagated to allow for the construction of the Parkway. There are 35 patches of Colicroot in seven subpopulations confirmed extant and one patch in one subpopulation presumed extant with status unknown. Approximately 93% of all individuals occur within 12 km2 in Windsor-LaSalle, and 82% of individuals (~12,000) are in the Parkway restoration sites. Only about 18% (~2700 plants) are present elsewhere. All Colicroot planted in Parkway restoration sites were originally naturally occurring plants, so plants in restoration sites are considered natural individuals.

Discoveries of new sites and increases of mature individuals constitute ~14,000 plants, but the total 2014 abundance is around 14,600: most of the population known when it was first assessed in 1987 has been lost. Assuming newly discovered plants existed previously and including the plants remaining from the previously known population, there may have been a base population of at least 18,330 in 1986. If the transplanted 7,680 individuals are removed from the total, a population of 10,650 remains. Since then, there has been a measurable loss of more than 5000 plants or >47% of the population, with the actual decline well upwards of that.

Threats and Limiting Factors

Threats to Colicroot include 1) Lack of Disturbance, 2) Invasive Species, 3) Herbivory, and 4) Development. To maintain Colicroot, its habitat must be actively and frequently managed to arrest succession; most of the habitat isn't managed this way, even in protected areas. Recreational activities may cause trampling but sometimes also provide necessary disturbance. It is unknown whether the net result is beneficial or detrimental.

Protection, Status and Ranks

COSEWIC most recently assessed this species as Endangered in November 2015. Colicroot is currently listed as Threatened on Schedule 1 of the Canadian Species at Risk Act (SARA) and as Threatened under the Ontario Endangered Species Act 2007. As of November 2014, no habitat has been regulated under provincial law. Sixteen Colicroot patches are in publicly owned "protected" areas, yet Colicroot remains highly threatened with significant declines on these lands. Ten patches are in private ownership, four patches are on First Nation lands, five are in Parkway restoration sites, and one has corporate ownership.

5. Common Hoptree

Photo: © Gary Allen

- Scientific name

- Ptelea trifoliata

- Taxon

- Vascular Plants

- COSEWIC Status

- Special Concern

- Canadian range

- Ontario

Reason for designation

In Canada, this small, short-lived tree occurs in southwestern Ontario, colonizing sandy shoreline habitats. A long-term decline in habitat quality and extent is predicted due to the effects of shoreline hardening, and historical sand mining in Lake Erie. One subpopulation depends on continuing management efforts. Improved survey effort has significantly increased the number of mature individuals, which reduces the overall risk to this species.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Common Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata) is a small tree in the rue family (Rutaceae). It has alternate trifoliate leaves which are aromatic; flowers bloom in early summer; they are borne in terminal clusters, cream coloured with 4-5 petals. Fruit, which matures in late summer, is dry, disk-shaped, and bears 2-3 seeds.

Common Hoptree is often a component of the stabilizing vegetation along sections of the Lake Erie shoreline. It has had a long history of medicinal and economic usage, including use by First Nations. It is one of two native Canadian species on which the larvae of the Giant Swallowtail butterfly feeds and is the primary nectar source for early adults of Juniper Hairstreak. It is also the sole host for larvae of the Hop-tree Borer. Hoptree Leaf-roller Moth and the Hoptree Barkbeetle are also specialist herbivores of the Common Hoptree.

Distribution

The typical subspecies (P. trifoliata ssp. trifoliata) occurs naturally from the lower Great Lakes to Texas, eastward from eastern Pennsylvania and southern New England to northern Florida. Other subspecies occur further south and west into Mexico.

Source: COSEWIC 2015. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Common Hoptree Ptelea trifoliata in Canada.

Long description for Map showing the Canadian distribution of Common Hoptree

Map showing the Canadian distribution of Common Hoptree (Ptelea trifoliata), indicating with open circles the observations made prior to 2002, and with closed circles the observations made between 2002 and 2014. The species distribution is limited in Canada to southern Ontario, the Lake Erie shoreline and a few inland sites.

Habitat

In Ontario, Common Hoptree occurs almost entirely along or near the Lake Erie shoreline. It is often found in areas of natural disturbance where it forms part of the outer edge of shoreline woody vegetation.

Biology

Common Hoptree is dioecious (male and female flowers on separate trees) with insect-pollinated flowers. The fruit is primarily wind-dispersed and may occasionally raft on lake ice or debris. Seedlings readily establish in open or disturbed sites.

Common Hoptree fruit Photo: © Gary Allen

Population Sizes and Trends

The trend in the Canadian population is unknown; however, within sites where subpopulation data are available the number of mature individuals appears to have increased by approximately 200% since the last report in 2002. Numbers at nine sites are increasing; three small sites were extirpated due to development and 34 lack comparable data to ascertain a trend. Eleven previously undocumented sites were recorded and two of the three sites identified as extirpated in 2002 were rediscovered. In total, an estimated 12,000 mature individuals occur in Canada.

Threats and Limiting Factors

In Canada, Common Hoptree rarely colonizes open inland habitats, being mostly limited to shoreline sites. The main threats to the species are loss of habitat resulting from altered coastal process, habitat succession and shoreline development.

Protection, Status and Ranks

In Canada, Common Hoptree is listed as Threatened at both the federal (Schedule 1, Threatened) and provincial level and is protected by both the Species at Risk Act (SARA) and the Ontario Endangered Species Act (2007). A recovery strategy for the species was published in 2012 and several of the key objectives have been addressed. COSEWIC assessed this species as Special Concern in November 2015.

Common Hoptree has been given a global rank of demonstrably secure (G5) by NatureServe; however, it is listed as critically imperiled (S1) in New Jersey and New York, apparently secure (S4) in Virginia and vulnerable (S3) in Ontario. Common Hoptree has not been assessed for the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species.

6. Flooded Jellyskin

Photo: © Robert E. Lee

- Scientific name

- Leptogium rivulare

- Taxon

- Lichens

- COSEWIC Status

- Special Concern

- Canadian range

- Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec

Reason for designation

Since this lichen was last assessed in 2004, increased search effort and a better understanding of its habitat requirements have revealed new occurrences in Manitoba, Ontario, and Quebec and the minimum number of mature individuals is now estimated at 350,000. Canada is thus the stronghold for this species which has declined or disappeared from elsewhere in its global range. Emerald Ash Borer is a major threat killing ash trees that are an important host species for this lichen where it is most abundant in southern Ontario. Up to 50% of the population may be affected within the next few decades. Another threat is climate change which is expected to create drier conditions that will reduce seasonal flooding which this lichen requires to survive. It also needs calcareous enrichment, and as a result has an even more patchy distribution in the inaccessible boreal regions of Manitoba and Ontario where the number of individuals is lower but not accurately known. The predicted impact of these two threats on this lichen results in the recommended status of Special Concern.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

The Flooded Jellyskin (Leptogium rivulare) is a small, grey or bluish-grey (when dry) leafy lichen, the surface of which becomes jelly-like when wet. Thalli are up to 4 cm in diameter and on the upper surface there are numerous reddish-brown fruiting bodies (apothecia). The Flooded Jellyskin is a "cyanolichen," in which the photosynthetic partner is a cyanobacterium in the genus Nostoc. Cyanolichens have been shown to contribute significant amounts of nitrogen to the ecosystems in which they occur. The Flooded Jellyskin is also special in that it is one of only a few macrolichens that can tolerate seasonal flooding by fresh water.

Distribution

The Flooded Jellyskin is a globally rare boreal-temperate lichen found in glaciated portions of eastern North America and eastern, central and western Europe. It is found mainly between the 45°N and 60°N parallels. In the USA, the Flooded Jellyskin was found historically as far south as Illinois and Vermont (possibly in glacial refugia) but there is only one recent record from central Wisconsin.

In Canada, three subpopulations of Flooded Jellyskin have been identified. The Ontario Lowlands subpopulation is the largest, and mostly confined to forested vernal pools. The Southern Shield subpopulation is the next largest along the southern limits of the Precambrian Shield near the interface with the Paleozoic Lowlands of Ontario and Quebec, with outliers in Wawa and Temagami. The post-glacial Lake Agassiz basin subpopulation is widely scattered in the boreal forest ecoregion of northern Ontario and Manitoba. A cluster of occurrences exists near Flin Flon, Manitoba, representing the most northerly (55°N) site of the Flooded Jellyskin in Canada.

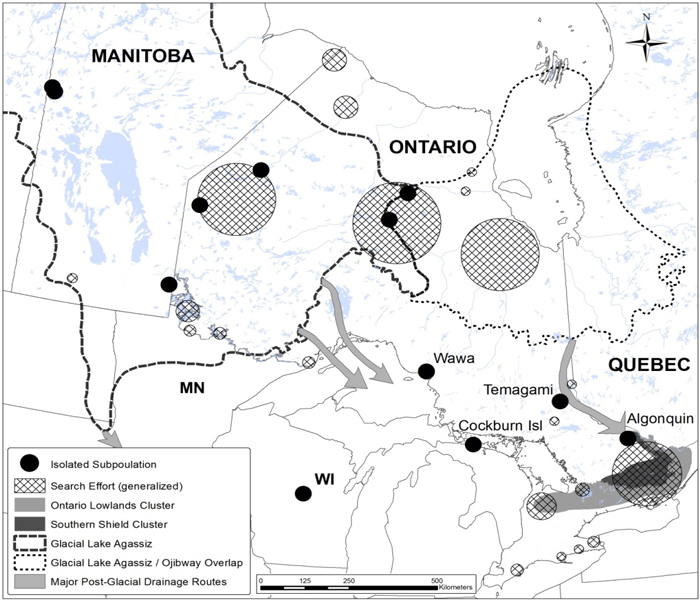

Source: COSEWIC 2015. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Flooded Jellyskin Leptogium rivulare in Canada.

Long description for map of Canadian distribution of Flooded Jellyskin

Map showing the Canadian distribution of Flooded Jellyskin (Leptogium rivulare), in three distinct subpopulations (Ontario Lowlands, Southern Sheild, and Post-glacial Lake Agassiz basin). In Canada, L. rivulare ranges from as far north and west as Flin Flon, Manitoba, eastwards 1,000 kilometres to the southwestern limits of the Hudson Bay Lowland on the Attawapiskat River, south 800 km to Grey County in southern Ontario, and east along the southern limit of the Canadian Shield of central Ontario, from the Kawartha Lakes region to the Gatineau region of Quebec.

Habitat

In Canada, the Flooded Jellyskin requires a humid habitat that is both calcareous and subject to seasonal flooding. The Ontario Lowlands subpopulation is mostly confined to forested vernal pools. The Southern Shield subpopulation is also found in seasonally flooded swamps and pools along the southern limits of the Precambrian Shield near the interface with the Paleozoic Lowlands. The post-glacial Lake Agassiz basin subpopulation is small and widely scattered in northern Ontario and Manitoba where it colonizes exposed bedrock, or large boulders along flooded lake shorelines in areas that overlie calcareous bedrock or on the margins of seasonally flooded rivers or lakes that have deposits of calcareous materials. For the Flooded Jellyskin to thrive, the water has to have a low sediment load, there needs to be a suitable substratum (tree, shrub or rock) and appropriate temperatures. The Flooded Jellyskin is most often recorded on Ash trees and less frequently on Maple, Elm and Willow. Partial shade provided by trees and tall shrubs appears to be important for maintaining high humidity and a moderate temperature during summer months. Full shade is not generally tolerated by this lichen. The limited dispersal ability of the Flooded Jellyskin likely restricts its occurrence and abundance.

Biology

Abundant apothecia are normally produced, and sexual reproduction is important in maintaining Flooded Jellyskin. Dispersal is achieved passively by the wind-borne spores, possibly aided by water currents. No specialized vegetative organs are produced, though presumably vegetative fragmentation may occur at smaller spatial scales. Dispersal in the species is likely limited by the required habitat conditions, which are not common on the landscape, and by the fact that the germinating spores require a substratum of suitable pH, temperature, light, and moisture as well as the presence of compatible cyanobacteria that enable the re-establishment of the fungal-algal symbiosis. Biotic vectors such as birds or mammals may be an infrequent or potential means of dispersal.

Population Sizes and Trends

Trends in the Canadian range or abundance of Flooded Jellyskin cannot be assessed, owing to the scarcity of historical data. Until 2004, the only known population in Canada consisted of just four occurrences. One of these historical occurrences, Wawa, Ontario, was not re-found and is likely extirpated as a result of air pollution and habitat destruction. Since 2004, increased survey efforts and an understanding of the Flooded Jellyskin's habitat requirements have resulted in an increase in the number of known occurrences, which is now 76 (roughly 352,000 individuals). It is likely that additional occurrences exist in northern Ontario, Manitoba, and possibly Saskatchewan and northern Quebec in areas formerly inundated by the post-glacial Agassiz and Ojibway lakes. However, only low numbers of thalli at widely scattered sites have been found in the post-glacial Lake Agassiz subpopulation, so further searches in these other areas are unlikely to increase the total population significantly.

Threats and Limiting Factors

The impact of the threats to the survival of the Flooded Jellyskin were assessed as "high" using the COSEWIC Threats Assessment Calculator. Since COSEWIC's last assessment of this lichen in 2004, the severity and scope of the threats have changed. Currently, the most important threat to this lichen is the Emerald Ash Borer beetle, which kills all native ash trees and is spreading rapidly both in Ontario and Quebec. Ash trees are important hosts for a significant portion of the Canadian range of the Flooded Jellyskin. Indeed, 99% of the known thalli are associated with plant communities where Ash is present. Twenty of the 76 known occurrences (roughly one quarter of the Canadian population) are in habitat dominated by ash, and another seven occurrences have ash recorded as a co-dominant host tree. Given the known rates of the spread of Emerald Ash Borer, the southern Flooded Jellyskin occurrences in Ontario and Quebec are likely to be affected within the next 10-20 years. Elm is another important substratum for the Flooded Jellyskin in central Ontario occurrences and Dutch Elm Disease is also continuing to kill trees in the province.

Another important threat is climate change, which may alter seasonal flooding in vernal pools and along water courses where flooding promotes the lichen and the establishment of its preferred host trees and shrubs. About 80% of Flooded Jellyskin occurrences are associated with seasonal vernal pool habitat, which is expected to become drier and less frequent. The limited dispersal abilities of the Flooded Jellyskin also increases its vulnerability to climate change, as many of its occurrences are small and isolated in remnant forest patches with vernal pools.

Dams pose another threat to this lichen as they alter flooding regimes along rivers. Changes to hydrology may alter or eliminate Flooded Jellyskin habitat. Other activities such as forestry, mining, quarries, and urban development that alter watercourses, water quality or the protective vegetation surrounding Flooded Jellyskin sites also have the potential to degrade habitat by exposing individuals to increased solar radiation and wind, thus reducing humidity and increasing erosion and water turbidity.

Protection, Status and Ranks

The Flooded Jellyskin was proposed for a global red list status in January 2015. it was assessed by COSEWIC as Threatened in 2004 and subsequently listed on Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act. A federal recovery strategy was completed in 2013. The Flooded Jellyskin is also listed as a Threatened species under the Ontario Endangered Species Act, 2007, receiving both species and habitat-level protection. It also receives protection by occurring in one Manitoba provincial park, and nine Ontario provincial parks or conservation reserves, which account for roughly 4 percent of the total Canadian population. There is no specific legal protection for Flooded Jellyskin in Quebec.

7. Hoptree Borer

Photo: © John and Jane Balaban

- Scientific name

- Prays atomocella

- Taxon

- Arthropods

- COSEWIC Status

- Endangered

- Canadian range

- Ontario

Reason for designation

This species is dependent on its sole larval host plant, Common Hoptree, which is confined to a narrow swath of southwestern Ontario and currently assessed as Special Concern. This moth has an even more limited range than that of its host - it is known only from the western shore of Point Pelee, and from Pelee Island. Very few individuals have been detected. The most imminent threats include loss of shoreline habitat through erosion, vegetation succession, and invasive plant species.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

The Hoptree Borer is a small moth (i.e., 17-20 mm wingspan), and the only species of the family Praydidae native to Canada. Despite its small size, the pattern and colour are distinctive, with a black-spotted, pure white forewing and a pinkish rust-brown hindwing and abdomen. Larvae are up to 20 mm long and pale green to yellowish with indistinct lateral lines.

The Hoptree Borer is one of three known insect herbivores that specialize on Common Hoptree, which is currently ranked as Special Concern at the provincial (Ontario) and federal level.

Distribution

Hoptree Borer occurs from the southern Great Lakes region through the Midwestern United States to south-central Texas. Its distribution is more restricted than that of its larval host plant, Common Hoptree. Hoptree Borer is apparently absent from a large portion of the range of Common Hoptree, which extends from the south Atlantic Coastal Plain to the Gulf coast in the southeastern US. In Canada, Hoptree Borer is known only from Point Pelee. It is also suspected to occur on Pelee Island based on the presence of distinctive larval feeding damage. This species ranges over an area of 148 km2.

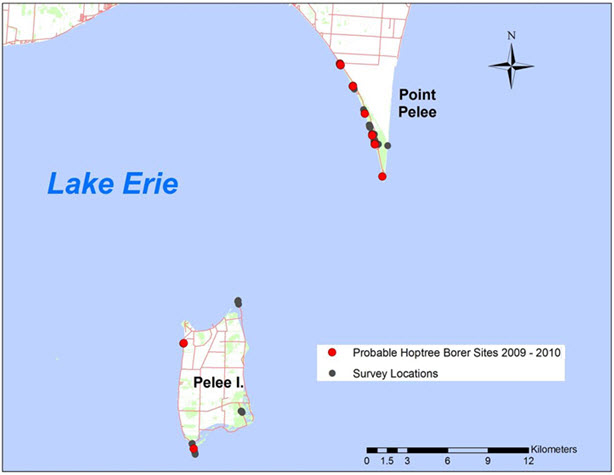

Source: COSEWIC 2015. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Hoptree Borer Prays atomocella in Canada.

Long description for map showing the suspected Canadian distribution of Hoptree Borer

Map showing the suspected Canadian distribution of Hoptree Borer (Prays atomocella). Confirmed occurrences of the species are restricted to Point Pelee National Park on the north shore of Lake Erie. In 2009 and 2010, probable evidence of the species (distinctive shoot damage on Common Hoptree) was also found on Pelee Island.

Habitat

Hoptree Borer is dependent on its sole larval host plant, Common Hoptree, which occurs on shoreline habitats of Lake Erie. Common Hoptree often forms the outermost shoreline vegetation with an active natural disturbance regime, primarily wind and wave erosion. Hoptree Borer has been documented only in the largest subpopulations of Common Hoptree, and has not been found in the smaller, more isolated Common Hoptree subpopulations along Lake Erie northeast of Point Pelee.

Biology

The life cycle of the Hoptree Borer is incompletely known. In Ontario there is one generation per year and adults are active from mid- to late June, during which time eggs are laid on the leaves or shoots of Common Hoptree. Only current-year shoots appear to be suitable for larval feeding. The duration of the egg, larval and adult stage are not precisely known, nor has the egg and egg-laying behaviour been described.

Larval development probably starts in the summer months after egg hatch. The larva bores into a young shoot and creates a diagnostic cavity in the woody stem below the shoot. The excavated material is incorporated into a silken cover for the cavity, forming a short tube that probably serves as a shelter to avoid predators and parasites. Larvae probably overwinter in bored-out stems, as in other species of Prays. Larval feeding continues the following spring after initiation of plant growth. Larvae leave the stem for pupation, which occurs in a distinctive mesh-like cocoon, often among the host plant flower clusters. Adult feeding has not been documented.

Population Sizes and Trends

Population size is unknown for Hoptree Borer. In 2010, feeding evidence consisted of 84 damaged Common Hoptree shoots, 62 at Point Pelee and 22 at Pelee Island. Previous collection records consist of single individuals collected or observed between 1927 and 2013.

Population trends for Hoptree Borer are not known. There may have been an increasing population trend mirroring the increase in the number of Common Hoptrees at Point Pelee and Pelee Island between 2002 and 2014, as a result of comprehensive surveys, in contrast to apparent declines of this plant between 1982 and 2002. The increase in Common Hoptrees, is suspected to be offset by ongoing and future habitat loss. Common Hoptree is abundant on Point Pelee with over 10,000 mature individuals, constituting 80-90% of the total number of mature individuals known in Canada. Pelee Island is the second largest subpopulation of Common Hoptree, estimated at 1,000 individuals.

Threats and Limiting Factors

Threats to Hoptree Borer include most of those identified for Common Hoptree. The potential threat impact is, however, higher for Hoptree Borer because it does not occur in all Common Hoptree subpopulations. The most imminent threats include shoreline erosion, vegetation succession, shoreline development, recreational activities and invasive plant species. Other potential threats include population outbreaks of the Hoptree Leaf-roller Moth, which can result in nearly complete defoliation of Common Hoptree and may adversely affect Hoptree Borer populations through direct competition and leaf and shoot dieback. Pesticide application for control of Gypsy Moth outbreaks is also known to adversely affect other moth species.

Protection, Status and Ranks

Hoptree Borer is not legally protected or ranked in any of the jurisdictions where it occurs. Hoptree Borer habitat within Point Pelee National Park is protected under the National Parks Act. On Pelee Island, one suspected Hoptree Borer occurrence was on a shoreline next to a road right-of-way, under the jurisdiction of the Municipality of Pelee Island. Other Pelee Island occurrences were in Fish Point Nature Reserve, where habitat is protected under the Provincial Parks and Conservation Reserves Act.

Common Hoptree is a species of Special Concern in Canada and Ontario and the species and its habitat are protected by the Species at Risk Act and Endangered Species Act respectively. Common Hoptree is given a global rank of Secure (G5) by NatureServe, with subnational ranks ranging from Critically Imperilled (S1) to Vulnerable (S3) for New Jersey, New York, and Maryland, but Hoptree Borer has not been documented in these states. It is likely of conservation concern in Wisconsin, where Common Hoptree is ranked Imperilled (S2), with at least one historical occurrence of Hoptree Borer.

8. Lake Erie Watersnake

Photo: © Gary Allen

- Scientific name

- Nerodia sipedon insularum

- Taxon

- Reptiles

- COSEWIC Status

- Special Concern

- Canadian range

- Ontario

Reason for designation

The Canadian distribution of this unique population of watersnakes is confined to four small islands in Lake Erie. In the United States, subpopulations have recovered because of an increased fish prey base, provided by introduced Round Goby. It is uncertain whether a similar recovery has occurred in Canadian subpopulations. There is concern that the largest subpopulation on Pelee Island continues to be threatened by road mortality, shoreline development, and persecution by humans.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Lake Erie Watersnake, Nerodia sipedon insularum, is one of two subspecies of the Common Watersnake, Nerodia sipedon (family Colubridae), found in Canada. Lake Erie Watersnakes range in appearance from being regularly patterned with dark dorsal and lateral blotches to a uniform grey (often a drab greenish or brownish) without pattern. The colour of the ventral scales is generally white or yellowish white, often with dark speckling. Lake Erie Watersnakes are heavy-bodied. The head is large and covered with broad, smooth scales and the body scales are "keeled". Long-term studies on Lake Erie Watersnakes have served as models for understanding evolutionary processes such as gene flow and selection, as well as provided researchers with an example of a rare species benefiting from the introduction of an invasive species.

Distribution

Lake Erie Watersnake has one of the smallest distributions of any snake in North America. In its Canadian range, Lake Erie Watersnake is known to occur only on four small islands in the western basin of Lake Erie (Pelee, Middle, East Sister, and Hen Islands). In the United States, Lake Erie Watersnake occurs in a small shoreline area of the Ohio mainland and on 11 Ohio islands in the western end of Lake Erie.

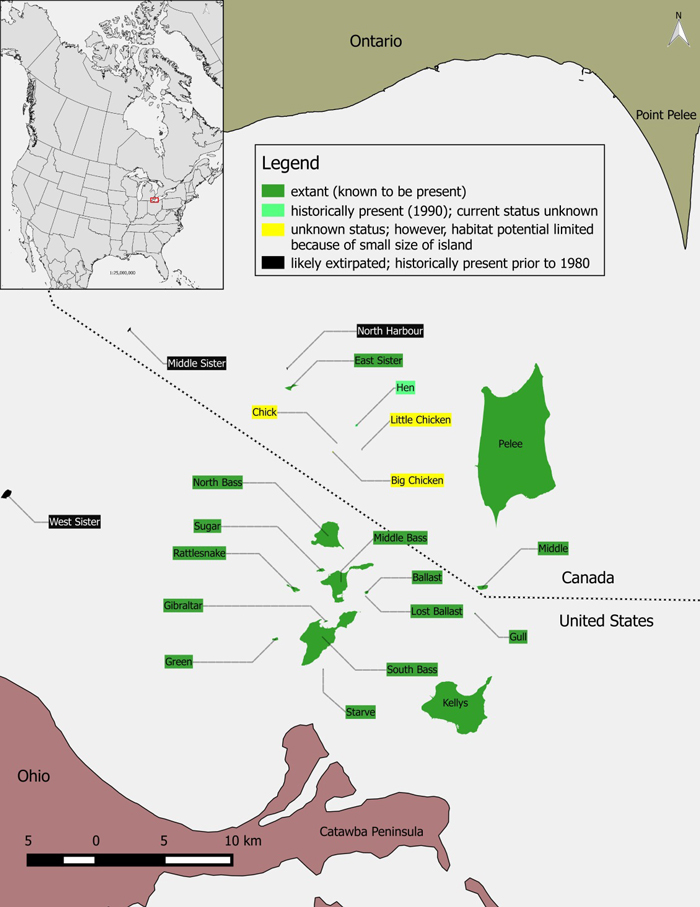

Source: COSEWIC 2015. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Lake Erie Watersnake Nerodia sipedon insularum in Canada.

Long description for map showing the distribution of Lake Erie Watersnake

Map showing the distribution of Lake Erie Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon insularum) in the western Lake Erie island region (Canada and USA), the global range is represented in the inset map. The Canadian range of the species is extant on Pelee, Middle, and East Sister Islands. The species were observed on Hen Island in 1990, however it is unknown whether they still occur on that island.

Habitat

During the active season, Lake Erie Watersnake occupies rocky or sandy shorelines, and limestone or dolomite shelves and ledges with cracks and varying levels of vegetation. Natural and human-made rock berms are also used. The snakes feed in the water but rarely go more than 200 m from shore while foraging. Watersnakes are rarely found more than 100 m inland during the active season, instead most of the time they are within 13 m of the water's edge. Distance travelled inland during the active season is dependent on the availability of shelter habitat and possibly conspecifics during the mating season. Hibernation habitat is farther inland and the sites used are usually cavities and crevices, and are typically composed of soil and rock substrates.

Biology

Lake Erie Watersnake can live up to 12 years in the wild. This species reaches sexual maturity at 3-4 years of age. Courtship involves scramble competition in which several males court one female simultaneously. Annual reproduction by females is common. Females give birth to live young and litter size averages 23 and is positively related to the female's size. Lake Erie Watersnake's historical diet has been largely replaced with Round Goby (Apollonia melanostomus), an invasive species that arrived in Lake Erie in the early 1990s.

Population Sizes and Trends

Lake Erie Watersnakes were reported in great numbers on several islands of western Lake Erie from the early 1800s and up to the early 1960s. Populations decreased in the latter half of the 20th century but are now increasing on U.S. islands, apparently associated with increased prey base from the introduction of Round Goby, which is an invasive fish. There is no information on trends on the Canadian islands, but the persistence of several threats suggests that populations may still be in decline.

Threats and Limiting Factors

Intentional and accidental human-induced mortality, particularly mortality on roads is likely the most significant threat to the species. Another important threat is the reduction of habitat quantity and quality. Additional threats include environmental contamination and elevated levels of predation. The small geographic range and small population size of Lake Erie Watersnake are limiting factors and increase the vulnerability of the snakes to perturbations.

Protection, Status and Ranks

Globally, NatureServe lists the Lake Erie Watersnake taxon as imperilled (global rank is G5T2). NatureServe lists Lake Erie Watersnake as imperilled (S2) in Ontario. In Canada, Lake Erie Watersnake was assessed as Endangered by COSEWIC in 1991 and 2006 and was added to Schedule 1 of the federal Species at Risk Act as Endangered in 2009. Ontario's Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA; Government of Ontario 2007) came into force in 2008 and protection is provided for Lake Erie Watersnake (designated Endangered on the Species at Risk in Ontario List). Under Ontario's Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, the taxon is considered a specially protected reptile. On Middle Island, the species is protected under the Canada National Parks Act. Lake Erie Watersnake was removed from the U.S. list of federally endangered and threatened species on August 16, 2011. Lake Erie Watersnake has a status of Endangered assigned by the state of Ohio.

9. Lake Huron Grasshopper

Photo: © Allan Harris

- Scientific name

- Trimerotropis huroniana

- Taxon

- Arthropods

- COSEWIC Status

- Threatened

- Canadian range

- Ontario

Reason for designation

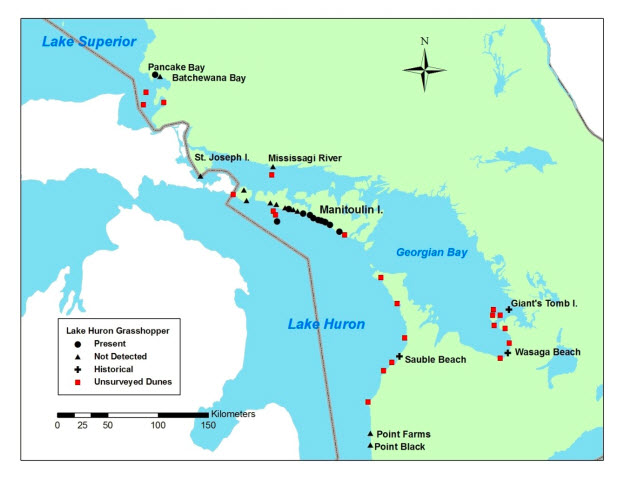

This globally rare grasshopper is endemic to the Great Lakes region of Ontario, Michigan, and Wisconsin where it is restricted to dunes along the shores of lakes Huron, Michigan, and Superior. In Canada, it is known from 11 dune sites: one location on the east shore of Lake Superior, and seven on Lake Huron at the south shore of Manitoulin Island and Great Duck Island. Formerly, it occurred at three additional sites on Lake Huron but these subpopulations appear to have become extirpated in the 1990s, likely as a result of residential and commercial development combined with intensive recreational use which damaged much of the dune habitat. While recreational use by pedestrians and off-road vehicles continue to threaten some dunes, other sites have undergone recent improvements under dune stewardship programs. Additional threats to dune environments include invasive plants and changes in lake levels related to climate change, natural cycles, or lake level management.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Lake Huron Grasshopper is silver-grey to brownish with variable speckles and colours to blend in with its sandy habitat. In flight, the hind wings are exposed to show clear or pale yellow areas at the base, a black band across the middle, and clear or smoky tips. The females (29 to 40 mm) are larger than the males (24 to 30 mm). It is one of a few species endemic to the Laurentian Great Lakes area.

Distribution

Lake Huron Grasshopper is endemic to the Great Lakes region of Ontario, Wisconsin and Michigan. The species is found exclusively on dunes along the shores of lakes Huron, Michigan and Superior. In Canada, it occurs at 11 dune sites: one location on the east shore of Lake Superior, and seven locations on Lake Huron at the south shore of Manitoulin Island and Great Duck Island. Historically it was also found at Giant's Tomb Island and Wasaga Beach in Georgian Bay, and at Sauble Beach (Southampton) on the east shore of Lake Huron. The species is now considered extirpated from these sites.

Source: COSEWIC 2015. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Lake Huron Grasshopper Trimerotropis huroniana in Canada.

Long description for Figure 1

Map showing the Canadian distribution of Lake Huron Grasshopper (Trimerotropis huroniana) including Pancake Bay on southern Lake Superior and dune complexes on the south shore of Manitoulin Island, and Great Duck Island in Lake Huron. Historically the range extended farther south in both Ontario and Michigan. Subpopulations at Giant's Tomb Island, Wasaga Beach, and Sauble Beach (Southampton) in Ontario and Saginaw Bay in Michigan are apparently extirpated. Surveys at these historical sites have failed to find this species since the 1990s.

Habitat

Great Lakes dunes cover a total area of less than 1800 ha in Canada including 492 ha on Lake Huron and 100 ha on Lake Superior. Dunes occur on shorelines where there is plentiful sand in glacial deposits and at river mouths. Exposure to wind and waves is essential to maintain erosion and deposition of sand, and to prevent forest succession. Preferred habitat of Lake Huron Grasshopper is the foredune, a low ridge closest to the lake with open bare sand and scattered grasses.

Biology

In late summer, male Lake Huron Grasshoppers attract females by stridulating (producing trills by rubbing the hind leg on the forewing) and conducting display flights while flashing their wings and producing a crackling sound. After mating, females lay clusters of eggs in the sand and the nymphs emerge the following spring. Nymphs pass through five instars before maturing into adults in late July or August. Marram Grass, Tall Wormwood, and Long-leaved Reed Grass are the preferred foods of nymphs and adults.

Female Lake Huron Grasshopper with two males. Photo: © Allan Harris

Population Sizes and Trends

Population sizes and trends are unknown. All known extant Canadian subpopulations were discovered since 2002 and no subpopulation estimates or monitoring data are available. Lake Huron Grasshoppers appear to have become extirpated from three historical sites in Canada (Giant's Tomb Island, Wasaga Beach, and Sauble Beach) between the early 1990s and the mid-1990s.

Threats and Limiting Factors

Residential and commercial development and intensive recreational use destroyed or damaged much of the dune habitat, likely causing the extirpation of Lake Huron Grasshopper at historical sites. Recreational use by pedestrians and off-road vehicles significantly reduces subpopulations and continues to threaten some dunes by damaging vegetation and causing dune blowouts (depressions caused by erosion of sand by wind). Invasive plants, especially Common Reed and Spotted Knapweed can replace preferred food plants and alter dune processes. Changes in lake levels related to climate change, natural cycles, or lake level management have the potential to reduce the amount of dune habitat. Some sites have undergone recent improvements under dune stewardship programs.

Protection, Status and Ranks

Lake Huron Grasshopper is not protected under any legislation or regulations in Canada. It listed as Threatened in Michigan and Endangered in Wisconsin but is not listed under the US Endangered Species Act. It is not listed under the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Pancake Bay on Lake Superior is a provincial park, but other habitat is under municipal and private ownership. Lake Huron Grasshopper occurs at 10 sites with Pitcher's Thistle (Threatened in Ontario and Special Concern nationally) where dunes receive some protection under Ontario's Endangered Species Act.

The Global Rank is G2G3 (Imperilled to Vulnerable). The Subnational Rank in Ontario was adjusted to S2 (Imperilled) from S1 following the discovery of new subpopulations in 2014. It is ranked as S1 (Critically Imperilled) in Wisconsin and S2S3 (Vulnerable) in Michigan.

10. Louisiana Waterthrush

Photo: © Dan Garber

- Scientific name

- Parkesia motacilla

- Taxon

- Birds

- COSEWIC Status

- Threatened

- Canadian range

- Ontario, Quebec

Reason for designation

During the breeding season in Canada, this songbird nests along clear, shaded, coldwater streams and forested wetlands in southern Ontario and southwestern Quebec. It occupies a similar habitat niche in Latin America during the winter. The Canadian population is small, probably consisting of fewer than 500 adults, but breeding pairs are difficult to detect. Population trends for the Canadian population are uncertain. Declines have been noted in some parts of the Canadian range, particularly in its stronghold in southwestern Ontario, while new pairs have been found in others. Immigration of individuals from the northeastern U.S. is thought to be important to maintaining the Canadian population. However, while the U.S. source population currently appears to be fairly stable, it may be subject to future population declines due to emerging threats to habitat.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

The Louisiana Waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) is a relatively large, drab wood-warbler that resembles a small thrush. Males and females are identical in appearance. The upper parts are dull brown. The lower parts are cream-coloured, with dark streaking on the breast and flanks. A bold, broad, white streak over the eye extends to the nape. The legs are bubble-gum pink, and the bill is rather long and heavy for a warbler.

Distribution

Most of the global breeding range (>99%) is within the eastern United States. In Canada, the Louisiana Waterthrush breeds in southern Ontario, where it is considered a rare, but regular local summer resident. It is also a rare, but sporadic breeder in southwestern Quebec. The bulk of the Canadian population is concentrated in two areas of Ontario: the Norfolk Sand Plain region bordering the north shore of Lake Erie, and the central Niagara Escarpment between Hamilton and Owen Sound.

Its wintering range extends from northern Mexico through Central America to extreme northwestern South America, and also throughout the West Indies.

Source: COSEWIC 2015. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Louisiana Waterthrush Parkesia motacilla in Canada.

Long description for map showing the global distribution of Louisiana Waterthrush

Map showing the global distribution of Louisiana Waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla), showing the breeding, migrating, and wintering range. The species primarily breeds within the eastern United States. In Canada, the Louisiana Waterthrush breeds regularly in southern Ontario, and is a rare and sporadic breeding bird in southwestern Quebec. The Louisiana Waterthrush winters from northern Mexico, south through Central America, and the West Indies.

Habitat

The Louisiana Waterthrush occupies specialized habitat, showing a strong preference for nesting and wintering along relatively pristine headwater streams and wetlands situated in large tracts of mature forest. Although it prefers running water (especially clear, coldwater streams), it also inhabits heavily wooded swamps with vernal or semi-permanent pools, where its territories can overlap with its sister species the Northern Waterthrush. It is often classified as both an area-sensitive forest species, and a riparian-obligate species. Louisiana Waterthrush nests are constructed within niches in steep stream banks, in the roots of uprooted trees, or in mossy logs and stumps, usually within a few metres of water.

Biology

The Louisiana Waterthrush is a long-distance migrant that typically arrives in southern Ontario much earlier in the spring than other neotropical songbirds. It displays annual fidelity to both breeding and wintering sites. Louisiana Waterthrush clutch size ranges from 4-6 eggs and incubation extends from 12-14 days. The species is generally single-brooded.

The Louisiana Waterthrush spends most of its time on or near the ground, along the margins of streams and pools. It has a specialized diet, feeding mostly on aquatic macro-invertebrates, especially insects, and sometimes eats small molluscs, fish, crustaceans, and amphibians.

Population Sizes and Trends

The Canadian population is estimated to be 235 to 575 adults. Population trends are poorly understood. The species has declined locally in parts of Canada in the past century and in the past few decades (related to habitat degradation and/or population fluctuations), but targeted surveys have found higher numbers in some parts of the Canadian range in recent years. Overall, populations in Canada and much of the U.S. currently appear to be relatively stable.

Threats and Limiting Factors

The Louisiana Waterthrush is a habitat specialist and its global population is limited by the supply of high-quality aquatic habitat on both its breeding and wintering grounds. There is no single imminent threat to the survival of the Canadian population; rather, it is the cumulative effects of many threats at different stages of its annual life cycle that are of particular concern. Habitat loss and changes in water quality/quantity due to agricultural intensification, and suburban residential development may have contributed to declines observed in parts of southern Ontario. Habitat conditions in Canada are expected to deteriorate due to the anticipated spread of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, an exotic forest pest, into eastern Canada. Habitat fragmentation and degradation on its U.S. breeding grounds due to the combination of exotic forest pests and resource development could reduce immigration into the Canadian population. Habitat loss and degradation, including degraded water quality and deforestation due to agricultural and development activities, are ongoing threats in the wintering range. During migration, this species also experiences relatively high rates of mortality due to collisions with tall buildings and communication towers.

Protection, Status and Ranks

The Migratory Birds Convention Act currently provides the most specific legislation protecting the Louisiana Waterthrush in Canada. A high proportion of known nesting sites are in protected areas. The specific habitats used by this species in Ontario are also provided some protection through various legislative policies. In addition, their physical characteristics generally preclude most kinds of agricultural and development activities.

11. McCown's Longspur

Photo: © Gordon Court

- Scientific name

- Rhynchophanes mccownii

- Taxon

- Birds

- COSEWIC Status

- Threatened

- Canadian range

- Alberta, Saskatchewan

Reason for designation

This grassland bird has experienced a severe population decline since at least the late 1960s, and there is evidence of a substantial, continuing decline. The species is primarily threatened by continuing loss and degradation of grassland habitats within both its breeding and wintering grounds.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

The McCown's Longspur (Rhynchophanes mccownii) is a grey or greyish brown sparrow-like songbird with an inverted black "T" pattern on its white tail. Males have a mostly white head with a black crown, moustache stripe, and bib patch. As an endemic species of the northern prairies, the species is a useful indicator of that habitat's condition.

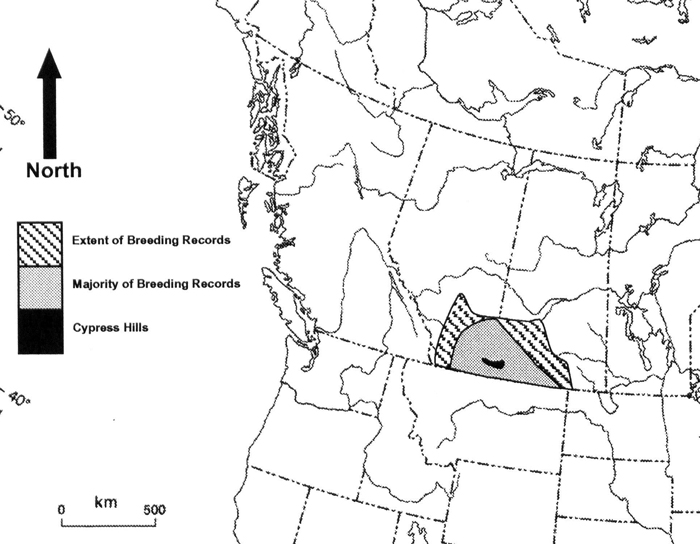

Distribution

The breeding range extends from southern Alberta and eastern Montana east to southern Saskatchewan and the western edge of the Dakotas. It has a slightly disjunct range in eastern Wyoming that extends slightly into neighbouring states. Historically, the range extended eastward to Minnesota and southward to Oklahoma. The wintering range is in the southwestern US (mainly Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona) and northern Mexico (mainly Chihuahua and Sonora).

Source: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the McCown's Longspur Calcarius mccownii in Canada.

Long description for map showing the Canadian distribution of McCown's Longspur

Map showing the Canadian distribution of McCown's Longspur (Rhynchophanes mccownii), representing 23% of the species global breeding range. In Canada, the species breeds only in southeastern Alberta and southwestern Saskatchewan, excluding the higher elevations of the Cypress Hills. Longspurs are uncommon on the edges of their breeding range, indicated with diagonal stripes.

Habitat

The species breeds in dry, sparse, short-cropped grassland with bare patches and few shrubs or forbs. Such habitat includes short-grass prairie, non-native pastures, closely grazed mixed-grass prairie, and some cultivated fields. Breeding habitat declined historically through the last century, and habitat loss and degradation continue, mainly because native grasslands are being converted for agriculture.

Biology

Birds probably breed in their first year. They are monogamous and territorial, and raise one, or, more rarely, two broods per year. Hatching success is high and starvation is rare, but predators take 30-75% of nests. Otherwise, demographic variables, particularly return and survival rates, are poorly known. Invertebrates, especially grasshoppers, are the main food provided to nestlings, but otherwise the species feeds mainly on seeds. Birds leave Canada for the wintering grounds starting in August, and return to Canada starting in April.

Population Sizes and Trends

The Canadian population is estimated from Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) results as 138,000 adults, which is about 23% of the global population. The best available information on trends, from the BBS, suggests the species declined by 98% in Canada between 1970 and 2012 and by at least 30% in the 10-year period between 2002 and 2012.

Threats and Limiting Factors

Threats include natural system modifications, agricultural effluents, oil and gas drilling, annual and perennial non-timber crops, renewable energy, and transportation and service corridors. Overall, threats were scored as having high to moderate impacts.

Protection, Status and Ranks

The species is protected under the Migratory Birds Convention Act of 1994 and listed as Special Concern under Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act. It is ranked as Apparently Secure globally, but as imperiled or vulnerable in most of the states in its US range. In Alberta and Saskatchewan it is ranked as vulnerable or apparently secure.

12. Mountain Crab-eye

Photo: © Paula Bartemucci

- Scientific name

- Acroscyphus sphaerophoroides

- Taxon

- Lichens

- COSEWIC Status

- Special Concern

- Canadian range

- British Columbia

Reason for designation

This charismatic lichen forms pale gray to yellow gray coral-like cushions. It is globally rare and there are only eight known occurrences in Canada. All are within British Columbia in a very restricted climatic zone, which lies between the hyper-maritime conditions found on the outer coast and the continental climate of the interior. There is a low IAO of 32 km2 and the total estimated population for this lichen is less than 250 colonies. However, this lichen occurs in remote, inaccessible sites within the rugged Coast Mountains, and additional new occurrences are likely to be discovered. In Canada, it is found primarily on dead Mountain Hemlock snags in patterned fen or bog complexes. Development pressures (roads, pipeline, hydroelectricity, mining and forestry) and climate change threaten hydrological regime and microclimatic conditions required by this species at many of the known sites.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Mountain Crab-eye is a medium-sized, yellowish to pale grey cushion-forming lichen. The lichen consists of dense tufts of cylindrical, stout, coral-like erect to semi-erect branches. The interior of the lichen is yellow to bright orange and solid. Fertile branches have immersed black fruiting bodies, giving the branches the appearance of stalked crab eyes. Non-fertile branches are smaller in diameter and height. The passively dispersed spores are dark brown, peanut-shell shaped, unornamented, and not well adapted for wind dispersal. The photosynthetic partner is believed to be the green alga, Trebouxia, though there is uncertainty. Mountain Crab-eye has a complex secondary chemistry and contains substances not found in other genera of pin lichens (Family Caliciaceae).

Mountain Crab-eye is the only species of the genus Acroscyphus. It is noteworthy that the Mountain Crab-eye in Canada occupies peatland habitats that are very different from the habitats of Mountain Crab-eye elsewhere in the world. There could be genetic or chemical differences between the Canadian subpopulations and other subpopulations.

Photo: © Paula Bartemucci

Photo: © Paula Bartemucci

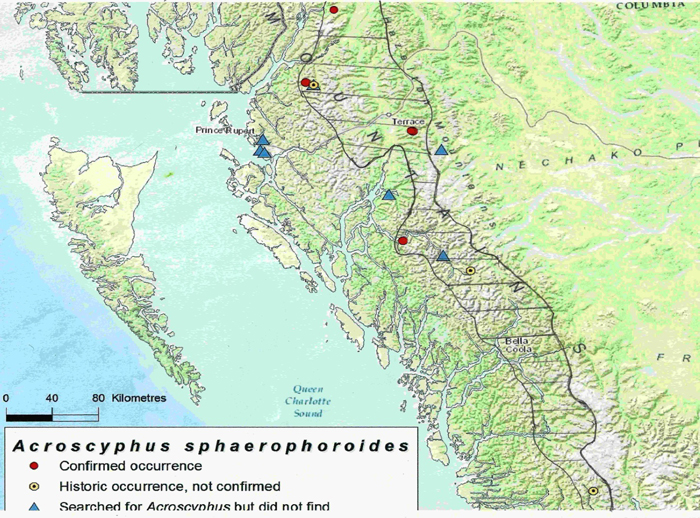

Distribution

Mountain Crab-eye has a widely disjunct global distribution. It is reported from high-altitude (> 3000 m), exposed alpine environments of China, Tibet, India, Bhutan, Japan, South Africa, Peru, Patagonia, and Mexico. The last is not confirmed. In Canada and USA, it is found at lower elevations: in Alaska (948 m), Washington (1300 m) and British Columbia (420 to 1000 m). There are currently eight known occurrences in Canada, all within the Coast Mountains of British Columbia, ranging from Kingcome River in the south, to Kitsault in the north. Despite a widespread distribution, there are few national and global occurrences.

Source: COSEWIC 2016. COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Mountain Crab-eye Acroscyphus sphaerophoroides in Canada.

Long description for map showing the distribution of Mountain Crab-eye

Map showing the distribution of Mountain Crab-eye (Acroscyphus sphaerophoroides). The species is currently known from eight occurrences in British Columbia, it is widely distributed from Satsalla River near Kingcome Inlet in the south, to Kitsault near the border of southeast Alaska in the North. The east-west range is narrow and restricted to the Coast Mountains. The hatched area is the restricted zone between the hypermaritime zone and the continental climatic zone of interior British Columbia where the habitat and climatic conditions appear to favour the occurrence of this lichen.

Habitat

In Canada, Mountain Crab-eye is almost exclusively found on trees within the coastal mountains, in a very restricted climatic zone which lies between the hypermaritime conditions found on the outer coast, such as Haida Gwaii and around Prince Rupert, and the continental climate of the interior of the province. This zone appears to be neither too wet or too dry and hence suitable for Mountain Crab-eye, which colonizes the stems and branches of standing snags or the dead, spiked tops of live trees. The trees may be Mountain Hemlock, Yellow-cedar or Sitka Spruce. This lichen is not found in the hypermaritime climates of the outer coast or in the continental climates of the interior of British Columbia.

Six of the eight occurrences in Canada are located in sparsely treed peatlands--fens or bog complexes. The seventh occurrence is located in a Mountain Hemlock subalpine forest and the last occurrence is in an open, wet subalpine parkland. Though alpine rocks are common substrata for Mountain Crab-eye in other regions of the world, only two colonies have been recorded on rock in Canada.

Biology