Black-footed albatross (Phoebastria nigripes) COSEWIC assessment and status report: chapter 4

Distribution

Global range

Breeding range

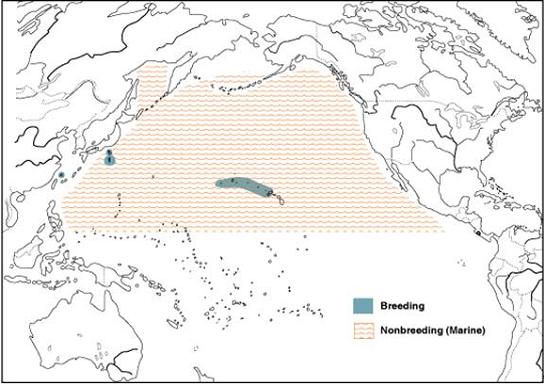

Black-footed Albatross do not nest in Canada. The Black-footed Albatross currently nests at 12 established sites worldwide and has recently begun to colonize or re-colonize at least four other localities (see below, this section) (Figure 2; Alexander et al. 1997; Pitman and Ballance 2002; USFWS 2005a). The species’ breeding distribution is almost entirely restricted to the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands (NWHI), where more than 95% of the global population breeds. The majority of the Hawaiian population nests at Midway Atoll and Laysan Island but lesser colonies occur from Lehua (near Niihau) in the main Hawaiian group to Kure Atoll at the western extreme of the Leeward Chain. Smaller colonies are also situated on islands off the coast of Japan, with colonies on the Muko Jima group in the northern Bonin Islands, Toroshima in the Izu Island group, and the Senkaku Islands in the southern Ryukyu archipelago (Rice and Kenyon 1962b; McDermond and Morgan 1993; Whittow 1993; Alexander et al. 1997; USFWS 2005a). The species has recently been recorded breeding at Guadalupe Island, Mexico and colonizing San Benedicto and Clarión Islands in the Revillagigedo group, 370 km south of Baja California (Pitman and Ballance 2002; Henry pers. comm. 2006; Tershy pers. comm. 2006), and within the last couple of years it has also expanded its breeding range to the Haha Jima group of the southern Bonin Islands (Hasegawa pers. comm. 2006). Historically, Black-footed Albatross nested at Johnston Atoll, Marcus Island, Marshall Islands, the Northern Marianas and Iwo Jima (Volcano Islands in the Bonin archipelago); these colonies were wiped out by feather hunters in the 19th century and by military occupation during World War II. The species has recently recolonized Wake Atoll in the central Pacific (Rice and Kenyon 1962b; Whittow 1993; USFWS 2005a).

Figure 2. Global range of the Black-footed Albatross (from Whittow 1993).

Marine range

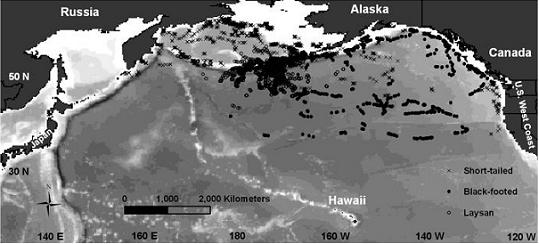

This widespread, trans-Pacific species ranges throughout the central North Pacific from the tropics to the Bering Sea, and from the west coast of North America to the coasts of China, Japan and the Sea of Okhotsk (15°N to 53°N and 112°W to 118°E; Gould and Piatt 1993; Whittow 1993; Shuntov 2000; Smith and Hyrenbach 2003). This is the most common albatross in the eastern sector of the North Pacific (Sanger 1974; McDermond and Morgan 1993; Springer et al. 1999) but it is “relatively scarce” in the western zone (McDermond and Morgan 1993), where the sympatric Laysan Albatross is more common (Gould and Piatt 1993; Springer et al. 1999; Figure 3). Cherel et al. (2002) have shown similar large-scale spatial segregation of foraging areas for southern hemisphere albatross species. The southern limits of the Black-footed Albatross’ marine range coincides with the southerly sweep of the California Current near Baja California, and the North Equatorial Counter Current in the central North Pacific, with birds occasionally found as far south as 10°N (McDermond and Morgan 1993) or, rarely, in the Southern Hemisphere (BirdLife International 2004a).

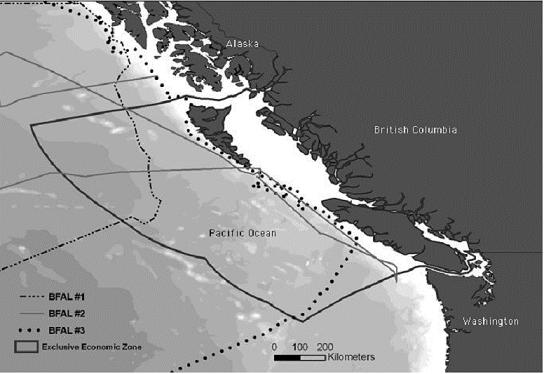

Figure 3. North Pacific Ocean, showing multiple fixes for three species of albatrosses (BFAL, n=10) tracked with satellite transmitters in summer 2005. Note that these birds were all captured near the Aleutian Islands rather than on their breeding colonies, which would bias the distribution of tracks shown. Map courtesy of R. Suryan and K. Fischer (unpubl. data), Oregon State University.

The marine range of the Black-footed Albatross is influenced by age and breeding status and enlarges and contracts with the breeding cycle. Adult birds are concentrated around the colonies during the egg-laying, incubation and chick brooding periods (November – February), while during chick rearing (March – July), breeding adults range at least 4,500 km from the colony to forage in more productive waters (McDermond and Morgan 1993; Cousins and Cooper 2000; Fernández et al. 2001; Hyrenbach et al. 2002). Post-breeding adults fly north or north-east across the Pacific Ocean, towards the west coast of North America, into the cool, productive waters of the transitional and sub-arctic zones (Robbins and Rice 1974; McDermond and Morgan 1993; Gould et al. 1998; Hyrenbach et al. 2002). All birds leave the colonies by the end of July, with breeders gradually returning to the vicinity of the Hawaiian Islands chain in October and November (McDermond and Morgan 1993). Most fledglings disperse west from the Hawaiian breeding colonies towards Japan and immature birds primarily spend summers and winters in the eastern North Pacific, likely using the same areas as adult birds. Non-breeders occur throughout sub-arctic waters in the North Pacific Ocean, from Japan to the west coast of North America (Brazil 1991; Whittow 1993; McDermond and Morgan 1993).

At smaller spatial scales, fishing vessel presence can influence albatross distribution. Wahl & Heineman (1979) suggested that commercial fishing operations in coastal Washington affected the distribution of the Black-footed Albatross on the continental shelf over an area of 100s of km², with birds significantly more abundant in their survey area on days when fishing vessels were present than when they were absent.

Canadian range

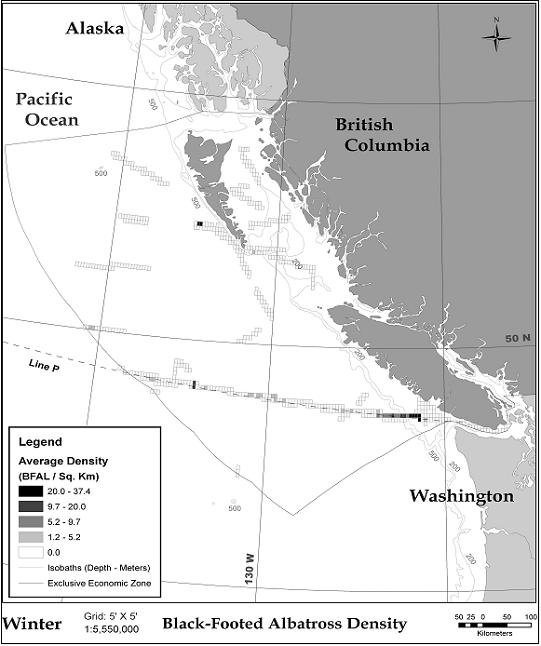

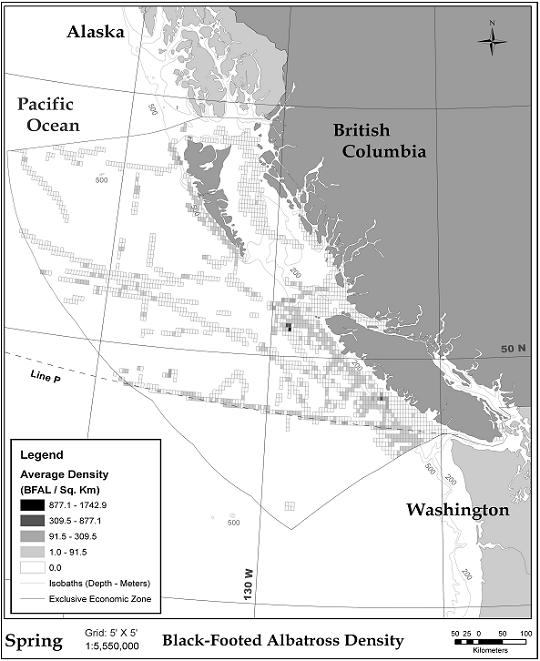

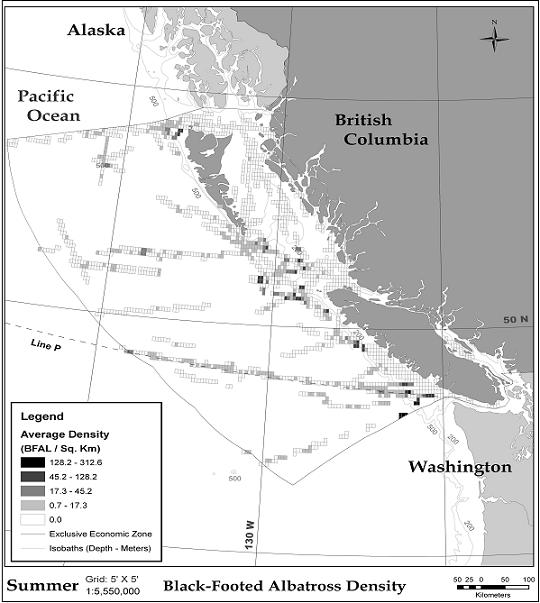

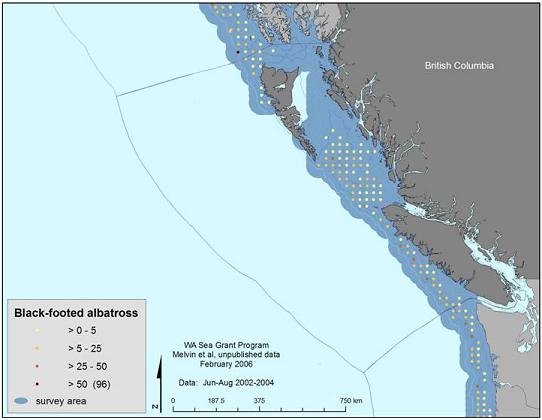

The Black-footed Albatross is the only albatross species seen regularly off Canada’s Pacific coast (Campbell et al. 1990; Morgan 1997). At-sea observations are recorded for every month of the year from waters off south-western Vancouver Island to Dixon Entrance off the north coast of the Queen Charlotte Islands/Haida Gwaii; it is commonest from April through October (Figures 4 – 8; Campbell et al. 1999; Morgan et al. 1991; Morgan 1997). The Black-footed Albatross is considered an offshore species but it is “common” (Wahl et al. 1993) over waters within a few nautical miles of the British Columbia coast; during summer an estimated 2,500 birds occur within Canadian waters (Hunt et al. 2000).

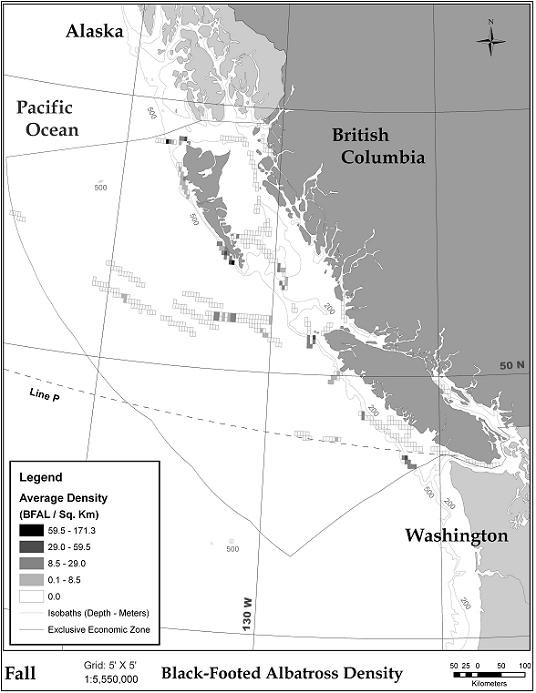

In August 2005, 10 Black-footed Albatrosses were fitted with satellite tags at Seguam Pass, Alaska and three of these birds passed through Canadian waters between 19 August and 22 September (Figures 3, 9; Suryan pers. comm. 2005). In British Columbia, Black-footed Albatross numbers peak during the post-breeding dispersal in August and early September, particularly along the continental shelf break. In late September to October, numbers decline along the British Columbia coast when birds return to their breeding colonies in Hawaii or Japan (Morgan et al. 1991; McDermond and Morgan 1993; Morgan 1997; Gould et al. 1998). Black-footed Albatrosses encountered within the Canadian exclusive economic zone (EEZ) after this time (i.e., October to June) historically have been assumed to be non-breeders or failed breeders (McDermond and Morgan 1993), but more recent data (e.g., Hyrenbach et al. 2002) indicate that during the chick-rearing stage, i.e., from February to July, breeding birds forage in the California Current as far north as British Columbia.

Although Black-footed Albatrosses are commonly found within British Columbia’s offshore waters in most months, sightings from shore are considered “unusual” from the Queen Charlotte Islands/Haida Gwaii (Johnston pers. comm. 2006) as well as the west coast of Vancouver Island (Hatler et al. 1978). Historically the species was also “rare” in the inshore, north coast waters (Kermode 1904; see also Special Significance of the Species, below). Canadian extralimital records include Nanaimo, BC (June 1900) and Satellite Channel near Victoria, BC (August 1957; Campbell et al. 1990).

Figure 4. Black-footed Albatross density in Canadian waters, winter survey tracks (16 Dec – 15 Mar). Source: Environment Canada, Pacific and Yukon Region.

Figure 5. Black-footed Albatross density in Canadian waters, spring survey tracks (16 Mar – 15 Jun). Source: Environment Canada, Pacific and Yukon Region.

Figure 6. Black-footed Albatross density in Canadian waters, summer survey tracks (16 Jun – 15 Sep). Source: Environment Canada, Pacific and Yukon Region.

Figure 7. Black-footed Albatross density in Canadian waters, fall survey tracks (16 Sep – 15 Dec). Source: Environment Canada, Pacific and Yukon Region.

Figure 8. Black-footed Albatross density in Canadian waters within International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC) survey areas (surveys from June – August, 2002 – 2004). Source: Washington Sea Grant.

Figure 9. Presence within Canadian EEZ of three Black-footed Albatrosses tracked with satellite transmitters from August to early October 2005. Map courtesy of R. Suryanand K. Fischer, Oregon State University.

Where the shelf break (200 m contour interval) approaches the continent, birds can be seen relatively close to land. Black-footed Albatross occur in Dixon Entrance West and are “regularly encountered” (Morgan 1997) in Queen Charlotte Sound and Hecate Strait, primarily south of Juan Perez Sound in the vicinity of the shelf break (Harfenist et al. 2002). Nonetheless, this species is more common off the West Coast than in any nearshore or inshore waters (Morgan 1997; Harfenist et al. 2002).