Dusky dune moth (Copablepharon longipenne) COSEWIC assessment and status report: chapter 8

Biology

- Life Cycle and Reproduction

- Predation and Parasitism

- Physiology

- Dispersal and Migration

- Interspecific Interactions

- Adaptability

The biology of C. longipenne is poorly known. This nocturnal moth with a short summer flight season is difficult to observe in the field. Current knowledge of the biology of C. longipenne is based on limited field observations in August 2004 and July 2005, supplemented with published information in Lafontaine (2004), Fauske (1992), Seamans (1925), and Strickland (1920).

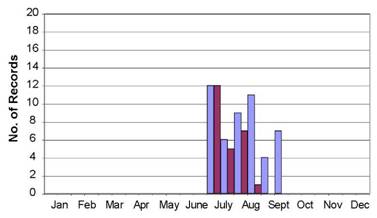

Copablepharon longipenne has one flight season per year during which it reproduces. In Canada, the flight season of C. longipenne is approximately ten weeks long and extends from the middle of June to late August (Figure 8). It peaks in July. The flight season in the US appears to be similar but may extend into September. These differences could be related to climatic differences along a north-south gradient, or could be influenced by incomplete sampling records. Reproduction coincides with the flight season and adult moths die shortly after reproducing.

Figure 8: Estimated Flight Season of C. longipenne Based on Sampling Records

The light bars indicate all North American records while the dark bars indicate Canadian records.

Adult C. longipenne have been observed nectaring during the evening on the flowers of dune plants, particularly lance-leaved psoralea. Mating was observed twice in 2005 and occurred on the lower stems of silverberry or on the sand surface near vegetation (Figure 9). Field observations indicate that eggs are deposited in groups of 15 to 35 approximately 10 mm below the sand surface. Based on observations of eggs collected in August 2004, larvae hatch after approximately three weeks.

Figure 9: Reproduction and predation: (a) mating occurring in July 2005 (Great Sand Hills, SK); (b) predation by birds was observed frequently in the margin of active dunes

Note, discarded wings shown with arrow.

Seamans’ (1925) observed that larvae fed on the below-ground parts of roses. Feeding likely occurs between hatching in August and the onset of cool weather in September–October. Larvae likely undergo a below-ground diapause between the fall and early spring, although the location and depth of burial are unknown. Based on observations of Copablepharon fuscum Troubr. & Crabo in coastal BC (COSEWIC, 2004), feeding may also occur in spring or early summer prior to pupation. The pupal stage is very poorly known, except that it likely occurs between early June and late July and lasts 17–19 days (Seamans, 1925). The adult lifespan is not known.

Observations of C. longipenne at the Seward Sand Hills in August 2004 suggests that oviposition occurs on the leeward side of active sand dunes. The placement of eggs in accretional sites may reduce exposure and desiccation from sand movement, and may also reduce predation of eggs.

Sex ratios of adult specimens in collections are generally evenly split (J. Troubridge, pers. comm.).

Seamans (1925) observed that none of the C. longipenne larvae he raised in captivity were parasitized; he believed that the subterranean feeding habits prevented parasitization. Predation of adults by birds was observed frequently in sampling sites in July 2005. The discarded wings of C. longipenne were found at dawn in association with bird tracks (Figure 9). Small birds, such as sparrows, appeared to actively search for moths hiding in the shrub and forb vegetation along the margins of active dunes. Common nighthawks (Chordeiles minor Forster) were also observed feeding on aerial insects above sand dunes in Saskatchewan. It is not known if small mammals (including bats or rodents), or other invertebrates such as beetles, prey on adult moths, larvae, or eggs.

Copablepharonlongipenneflies during the onset of warmer weather in early summer and maximizes its larval growth during July and August, the warmest months in the Canadian prairies. The larvae likely overwinter in the sand, although conditions of dormancy (e.g., depth of burial) or other overwintering strategies are unknown.

The influence of climate on C. longipenne distribution is unknown. Distribution is associated with the warmest and driest region in the Canadian prairies. Climate data from the Canadian range of C. longipenne are summarized as follows: in Swift Current, SK the mean monthly winter temperature (Dec–Feb) is -10.8°C, the mean monthly summer (June–Sept) temperature is 16.9°C, the mean monthly winter precipitation is 17.3 mm (most as snow), and the mean monthly summer precipitation is 55.5 mm. It is not known how seasonal temperature changes affect adult flight periods, mating, and larval survival.

The dispersal abilities of C. longipenne have not been measured. Field observations suggest it is a strong flier and it easily evaded capture with hand-nets during strong winds. Given that open dune habitats are often patchily distributed across a landscape (0.1–2.5 km apart), it is likely that dispersal at this scale is frequent. However, regional dispersal between sand dunes areas (e.g., landscape-level dispersal > 10 km) is considered unlikely or very infrequent. There is no information that suggests C.longipenne is migratory.

There is no information on inter-specific interactions that may reduce survival of C. longipenne. Observations indicate it uses open sand, rather than leaves or flowers, for ovipositing. Seamans (1925) noted that “this species was found feeding entirely on rose bushes”, however, several sites in which C. longipenne were captured in 2004–2005 did not support rose species. The larvae of C. longipenne could feed on grasses (Canada wildrye, wheat grasses, etc.), shrubs (roses, silverberry, etc.), and dune forbs such as lance-leaved psoralea and sand-dock.

There is no information on the adaptability of C. longipenne other than the lifecycle observations described previously. The moth is a disturbance-tolerant species associated with active sand dunes with frequent sand movement. However, based on its specific habitat requirements, it may not be adaptable to habitat change.

Copablepharon longipenne was raised successfully from young larvae to adults by Seamans (1925).