Leiberg’s fleabane (Erigeron leibergii): COSEWIC assessment and status report 2016

Data deficient

2016

Table of contents

- Table of contents

- Assessment summary

- Executive summary

- Technical summary

- Preface

- Wildlife species description and significance

- Distribution

- Habitat

- Biology

- Population sizes and trends

- Threats and limiting factors

- Protection, status and ranks

- Acknowledgements and authorities contacted

- Information sources

- Biographical summary of report writers

- Collections examined

List of figures

- Figure 1. Erigeron leibergii. Photo by Matt Fairbarns, with permission. Photographed near Hart’s Pass, Washington State.

- Figure 2. Illustration of Leiberg's Fleabane. Rumely, ex Hitchcock et al. 1955 with permission.

- Figure 3. Basal and stem leaves. Photo by Matt Fairbarns, with permission. Photographed near Hart’s Pass, Washington State.

- Figure 4. Flower head. Photo by Matt Fairbarns, with permission. Photographed near Hart’s Pass, Washington State.

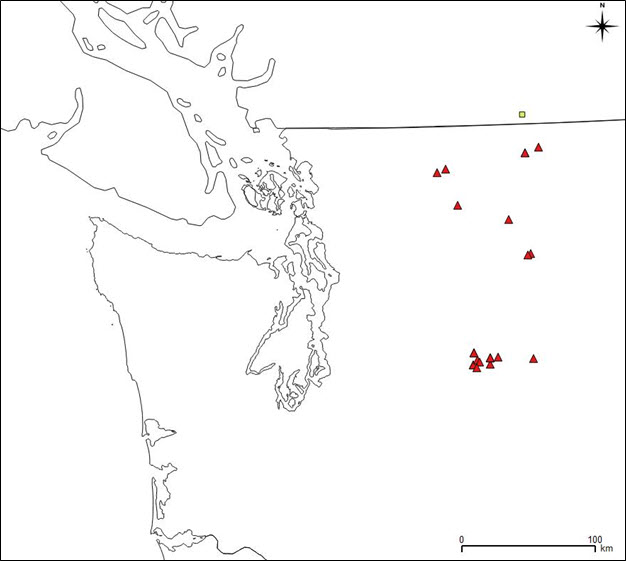

- Figure 5. Distribution. Red triangles mark sites of US collections (Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria 2014). Green square is location of Canadian 1980 collection by Douglas and Douglas.

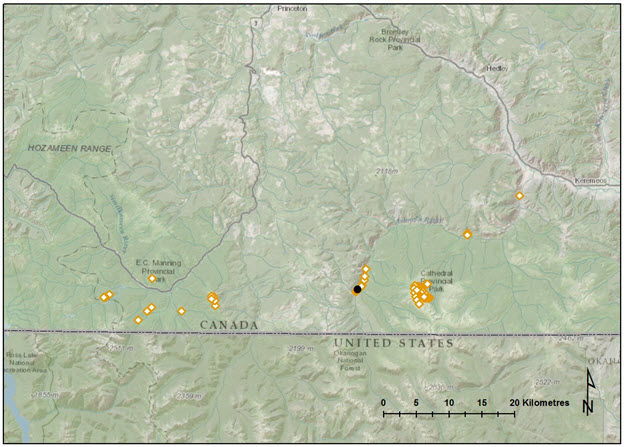

- Figure 6. Negative search effort. Yellow diamonds mark places searched. Black dot is location of Canadian 1980 collection by Douglas and Douglas.

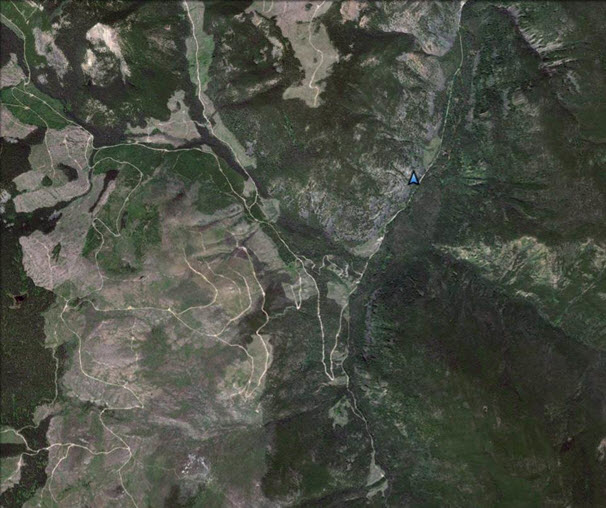

- Figure 7. Cutblocks along the Ashnola River. The blue arrow shows the approximate locality of the 1980 collection by Douglas and Douglas. Note that slopes to the east of the River, which lie within Cathedral Lakes Provincial Park, are unlogged. Photo from Google Earth. Image copyright DigitalGlobe 2015.

Document information

COSEWIC

Committee on the Status

of Endangered Wildlife

in Canada

COSEPAC

Comité sur la situation

des espèces en péril

au Canada

COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows:

COSEWIC. 2016. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Leiberg’s Fleabane Erigeron leibergii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 22 pp. (Species at Risk Public Registry website).

Production note:

COSEWIC acknowledges Matt Fairbarns for writing the status report on Leiberg’s Fleabane, Erigeron leibergii, in Canada, prepared with the financial support of Environment & Climate Change Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Del Meidinger, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Vascular Plants Specialist Subcommittee.

For additional copies contact:

COSEWIC Secretariat

c/o Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment and Climate Change Canada

Ottawa, ON

K1A 0H3

Tel.: 819-938-4125

Fax: 819-938-3984

E-mail: COSEWIC E-mail

Website: COSEWIC

Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Nom de l’espèce (Erigeron leibergii) au Canada.

Cover illustration/photo:

Leiberg’s Fleabane - Photo credit: Matt Fairbarns.

COSEWIC assessment summary

Assessment summary – November 2016

- Common name

- Leiberg’s Fleabane

- Scientific name

- Erigeron leibergii

- Status

- Data Deficient

- Reason for designation

- This perennial herb has only been collected from one site in south central British Columbia; field surveys suggest that it may have been lost from that site. Nearby searches failed to find any other subpopulations. There is uncertainty in whether a viable population was, or is, established because much of the potential habitat is difficult to access. Uncertainty in whether the species still occurs in Canada and if, and when, the one known population was lost, prevents a status determination at this time.

- Occurrence

- British Columbia

- Status history

- Species considered in November 2016 and placed in the Data Deficient category.

COSEWIC executive summary

Leiberg’s Fleabane

Erigeron leibergii

Wildlife species description and significance

Leiberg’s Fleabane is a perennial herbaceous plant, 7-25 cm tall, branching at its stout base, arising from a taproot. The plant has well-developed basal and stem leaves, which bear dense, small hairs. The basal leaves are somewhat larger than the stem leaves. The flowering stems produce 1-5 blue to purplish flower heads. Leiberg’s Fleabane is of interest because it is endemic to a small transboundary area.

Distribution

Leiberg’s Fleabane is endemic to the Cascade and Wenatchee Mountains of Okanogan, Chelan and Kittitas counties in central Washington State and extreme south-central British Columbia. Its global extent of occurrence is approximately 10,380 km2. In Canada, Leiberg’s Fleabane has only been confirmed from one subpopulation, in the valley of the Ashnola River, approximately 25 km southwest of Keremeos, British Columbia. This subpopulation, detected in 1980, has not been seen since. The range in Canada constitutes less than 1% of the species’ global range. If the Ashnola subpopulation has been extirpated this would constitute a 100% decline in the known Canadian range over the past 35 years. However, other subpopulations may occur.

Habitat

In Canada, Leiberg’s Fleabane, has been found in a single area where it occurred on dry and rocky terrain on an open southeast-facing montane slope at 1,280 m. In northern Washington State it usually occurs at elevations varying from 900-2,600 m, on open to lightly shaded rock bluffs, ledges or rocky talus slopes.

Biology

Very little is known about the biology of Leiberg’s Fleabane. Flowering usually occurs between early June and late August and the flowers are probably pollinated by a wide variety of insects. Based on its growth form, its generation time is probably several years long. Very few seed-like fruits are likely to disperse over distances of more than a few metres because they lack structures that facilitate long-distance transport by wind or animals.

Population size and trends

Surveys within its historical range in Canada and in other areas near its range in the United States failed to detect Leiberg’s Fleabane. This suggests that the only reported Canadian subpopulation was lost since it was originally discovered in 1980, although there has been too little botanical surveying to determine when it disappeared or whether there may be undiscovered Canadian subpopulations.

Threats and limiting factors

Potential habitat for Leiberg’s Fleabane within its historical range in Canada has declined in quality due to extensive logging. There has been an unprecedented extent and frequency of forest fires within its range in the U.S., which may be attributed to climate change and the effects of past logging and historical wildfire suppression. These factors presumably occur within its historical range in Canada as well in other areas of Canada near known US subpopulations. Numerous alien invasive species have arrived in its range and their abundance is likely to increase in response to logging and fire.

Protection, status, and ranks

The lone Canadian subpopulation of Leiberg’s Fleabane is not protected under federal Species at Risk Act or provincial species at risk legislation. Leiberg’s Fleabane is ranked by NatureServe (2014) as G3? (globally vulnerable). In Canada it has a general status rank of 2: may be at risk. In Washington it is not ranked (SNR) but is no longer considered vulnerable. In British Columbia, Leiberg’s Fleabane is ranked S1 (critically imperilled). It is a priority 2 species under the B.C. Conservation Framework and is included on the British Columbia Red List. Although the precise location of the 1980 collection by Douglas and Douglas is uncertain, all plausible places where this collection was made are provincial crown lands managed for forestry.

Technical summary

- Scientific name:

- Erigeron leibergii

- English name:

- Leiberg’s Fleabane

- French name:

- Vergerette de Leiberg

- Range of occurrence in Canada (province/territory/ocean):

- British Columbia

Demographic information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

Generation time (usually average age of parents in the population; indicate if another method of estimating generation time indicated in the IUCN guidelines (2011) is being used) There is no basis for estimating generation apart from the fact that Leiberg’s Fleabane is a perennial that is likely long-lived. |

Unknown, but likely several years. |

Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] continuing decline in number of mature individuals? The failure to detect Leiberg’s Fleabane, even in the vicinity of the only previous collection, indicates that the only Canadian subpopulation may have disappeared since it was observed in 1980. If the species has disappeared from the original collection location over the ensuing 35 years then it is still unclear when this happened, and whether the subpopulation was lost over the past three generations (due to uncertainty regarding generation time). |

Yes |

Estimated percent of continuing decline in total number of mature individuals within [5 years or 2 generations]. The species may have been extirpated in Canada but even if the species has been extirpated it is not clear whether this has happened within 5 years/ 2 generations. |

Unknown |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the last [10 years, or 3 generations]. | Unknown |

[Projected or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the next [10 years, or 3 generations]. The species may have been extirpated in Canada; if so there is no possibility of further decline. |

Unknown |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over any [10 years, or 3 generations] period, over a time period including both the past and the future. | Unknown |

| Are the causes of the decline a.clearly reversible and b.understood and c. ceased? | a. could be reversible as there is plenty of apparently suitable habitat b. reasons for decline unknown c. without knowing the reasons for decline it is impossible to know if they have ceased |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals? | Unknown |

Extent and occupancy information

| Summary items | information |

|---|---|

| Estimated extent of occurrence (EO) (estimated historical extent of occurrence) | 4 km2 based on single known subpopulation |

| Index of area of occupancy (IAO) (Always report 2x2 grid value). |

4 km2 based on single known subpopulation |

| Is the population “severely fragmented”; i.e. is >50% of its total area of occupancy in habitat patches that are (a) smaller than would be required to support a viable population, and (b) separated from other habitat patches by a distance larger than the species can be expected to disperse? | Unknown a. Probably, if still extant. Single subpopulation is entire known population in Canada, and is likely small in numbers of individuals. b. Unknown. Single subpopulation is separated by 20 km from US subpopulations. Unknown if other Canadian subpopulations exist. |

| Number of locations (Note: See Definitions and abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.) |

0-1; at this time there is no basis for speculating beyond one, although other locations may be found. |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in extent of occurrence? The species has not been detected in recent years and may have disappeared within the past three generations. |

Possibly |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in index of area of occupancy? The species has not been detected in recent years and may have disappeared within the past three generations. |

Possibly |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of subpopulations? The species has not been detected in recent years and may have disappeared within the past three generations. |

Possibly |

Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of “locations”? The species has not been detected in recent years and may have disappeared within the past three generations. |

Possibly |

Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in [area, extent and/or quality] of habitat? Forestry operations have severely altered much of the potential habitat within the historical extent of occurrence. |

Yes |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of subpopulations? | Unknown; species has only been observed at one subpopulation. |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of “locations”? (Note: See Definitions and abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.) |

No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in index of area of occupancy? | No |

Number of mature individuals (in each subpopulation)

| Subpopulations (give plausible ranges) | N Mature Individuals |

|---|---|

| Ashnola River valley | Unknown; possibly 0. |

| Total | Unknown; possibly 0; likely fewer than 1000 even if other subpopulations discovered. |

Quantitative analysis

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Probability of extinction in the wild is at least [20% within 20 years or 5 generations, or 10% within 100 years]. | Not assessed. |

Threats (actual or imminent, to populations or habitats, from highest impact to least)

- i. Logging, and associated roads and slash piles.

- ii. Fire

- iii. Invasive non-native/alien species

Was a threats calculator completed for this species and if so, by whom? No

Rescue effect (immigration from outside Canada)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status of outside population(s) most likely to provide immigrants to Canada. | Secure |

| Is immigration known or possible? | Yes, it is possible |

| Would immigrants be adapted to survive in Canada? | Yes |

| Is there sufficient habitat for immigrants in Canada? | Yes |

| Are conditions deteriorating in Canada? See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Yes |

| Are conditions for the source population deteriorating? See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Yes |

| Is the Canadian population considered to be a sink? See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Unknown |

| Is rescue from outside populations likely? | Unknown |

Data-sensitive species

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Is this a data sensitive species? | No |

Status history

Species considered in November 2016 and placed in the Data Deficient category.

Status and reasons for designation:

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status: | Data Deficient |

| Alpha-numeric code: | Not applicable |

| Reasons for designation: | This perennial herb has only been collected from one site in south central British Columbia; field surveys suggest that it may have been lost from that site. Nearby searches failed to find any other subpopulations. There is uncertainty in whether a viable population was, or is, established because much of the potential habitat is difficult to access. Uncertainty in whether the species still occurs in Canada and if, and when, the one known population was lost, prevents a status determination at this time. |

Applicability of criteria:

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Criterion A (Decline in total number of mature individuals): |

Possibly meets Endangered A2a if only known population no longer exists; unable to locate species at known site and because unknown when loss may have occurred, it could have been more than 10 years / 3 generations ago. |

| Criterion B (Small distribution range and decline or fluctuation): |

Possibly meets Endangered B1ab(iv,v)+2ab(iv,v) as EOO and IAO are each 4 km2; there are likely fewer than 5 locations; and there is an observed decline in subpopulations (1 to 0) and mature individuals, IF one known population no longer exists. |

| Criterion C (Small and declining number of mature individuals): |

Possibly meets C2a(i,ii) as total number of individuals, although not known, is likely fewer than 2500, and there is an observed decline in the number of mature individuals, assuming that the one known population no longer exists. |

| Criterion D (Very small or restricted population): |

Possibly meets Endangered D1, but number of mature individuals is unknown – may be zero. |

| Criterion E (Quantitative analysis): |

Not applicable. |

Preface

COSEWIC history

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) was created in 1977 as a result of a recommendation at the Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference held in 1976. It arose from the need for a single, official, scientifically sound, national listing of wildlife species at risk. In 1978, COSEWIC designated its first species and produced its first list of Canadian species at risk. Species designated at meetings of the full committee are added to the list. On June 5, 2003, the Species at Risk Act (SARA) was proclaimed. SARA establishes COSEWIC as an advisory body ensuring that species will continue to be assessed under a rigorous and independent scientific process.

COSEWIC mandate

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assesses the national status of wild species, subspecies, varieties, or other designatable units that are considered to be at risk in Canada. Designations are made on native species for the following taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, arthropods, molluscs, vascular plants, mosses, and lichens.

COSEWIC membership

COSEWIC comprises members from each provincial and territorial government wildlife agency, four federal entities (Canadian Wildlife Service, Parks Canada Agency, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the Federal Biodiversity Information Partnership, chaired by the Canadian Museum of Nature), three non-government science members and the co-chairs of the species specialist subcommittees and the Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge subcommittee. The Committee meets to consider status reports on candidate species.

Definitions (2016)

- Wildlife species

- A species, subspecies, variety, or geographically or genetically distinct population of animal, plant or other organism, other than a bacterium or virus, that is wild by nature and is either native to Canada or has extended its range into Canada without human intervention and has been present in Canada for at least 50 years.

- Extinct (X)

- A wildlife species that no longer exists.

- Extirpated (XT)

- A wildlife species no longer existing in the wild in Canada, but occurring elsewhere.

- Endangered (E)

- A wildlife species facing imminent extirpation or extinction.

- Threatened (T)

- A wildlife species likely to become endangered if limiting factors are not reversed.

-

Special concern (SC)

(Note: Formerly described as “Vulnerable” from 1990 to 1999, or “Rare” prior to 1990.) - A wildlife species that may become a threatened or an endangered species because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

-

Not at risk (NAR)

(Note: Formerly described as “Not In Any Category”, or “No Designation Required.”) - A wildlife species that has been evaluated and found to be not at risk of extinction given the current circumstances.

-

Data deficient (DD)

(Note: Formerly described as “Indeterminate” from 1994 to 1999 or “ISIBD” [insufficient scientific information on which to base a designation] prior to 1994. Definition of the [DD] category revised in 2006.) - A category that applies when the available information is insufficient (a) to resolve a species’ eligibility for assessment or (b) to permit an assessment of the species’ risk of extinction.

The Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, provides full administrative and financial support to the COSEWIC Secretariat.

Wildlife species description and significance

Name and classification

Scientific Name: Erigeron leibergii Piper

Synonyms: Erigeron chelanensis St. John

Common English Names: Leiberg’s Fleabane, Leiberg’s Daisy

Common French Name: vergerette de Leiberg

Family Name: Asteraceae (Aster Family)

Leiberg’s Fleabane is a distinct species with no described subspecies or varieties and no taxonomic complications.

Morphological description

Leiberg’s Fleabane is a 7- to 25-cm tall, perennial herbaceous plant, branching at its stout base, arising from a taproot (Figures 1 and 2). The stems are erect and covered with sparsely to moderately dense small, somewhat stiff hairs tipped with small glands. The plants bear leaves both at their base and on their stems. The basal leaves (Figure 3) are usually 20-90 mm long and 5-25 mm wide and the stem leaves are smaller and narrower. The uppermost stem leaves are smallest but even they are relatively well developed, unlike the much reduced stem leaves of many other species in the genus. The basal leaves, and lower stem leaves, may sometimes have three prominent nerves running from the leaf base to its tip. The leaves are moderately hairy, the hairs similar to those found on the stems. The stems bear 1-5 heads (Figure 4) that are 5-8 mm long and 7-14 mm wide. Each head consists of 2-3 ranks of outer bracts which are similarly hairy as the stems and leaves. Inward from the bracts, there are 20-45 ray florets arranged in several ranks. The ray florets are usually blue to purplish but may be pink or white, and 5-12 mm long. The innermost portion of the head consists of 3- to 4.3-mm long disc florets. The fruits are cypselae (dry, one-seeded fruits), 1.8-2 mm long. The cypselae are 2-nerved and sparsely hairy. The top of each fruit bears a ring of 12-16 bristles, sometimes with an additional outer ring of a few small scales (Hitchcock et al. 1955; Nesom 2006).

Long description for Figure 1

Photo of a Leiberg’s Fleabane plant that has been uprooted and displayed on a rock. Stems of the Leiberg’s Fleabane arise from a taproot; they are erect and covered with sparsely to moderately dense small, somewhat stiff hairs. Leaves are borne at the base of the plant and on the stems, with stem leaves smaller and narrower.

Long description for Figure 2

Illustration of the Leiberg’s Fleabane, a perennial herbaceous plant that is 7 to 25 centimetres tall and branches at its stout base. The stems are erect and covered with sparsely to moderately dense small, somewhat stiff hairs. The plant bears leaves both at the base and on the stems. The flower heads consist of two to three ranks of outer bracts; inward from these are 20 to 45 ray florets arranged in several ranks.

Long description for Figure 3

Photo of the basal and stem leaves of the Leiberg’s Fleabane. Basal leaves are usually 20 to 90 millimetres long and 5 to 25 millimetres wide. The stem leaves are smaller and narrower. The leaves are moderately hairy.

Long description for Figure 4

Photo of the flower head of the Leiberg’s Fleabane. The head consists of two to three ranks of outer bracts. Inward from these are 20 to 45 ray florets arranged in several ranks. The ray florets are usually blue to purplish and 5 to 12 millimetres long.

There are several other congeneric species within the Canadian range of Leiberg’s Fleabane. Using keys and descriptions provided by Cronquist (1955) and Nesom (2006) similar species may be distinguished from Leiberg’s Fleabane as follows [Note: This section is more comprehensive than is normally the case but other members of the genus are often misidentified. The discovery of a specimen of Bitter Daisy (Erigeron acris) misidentified as Leiberg’s Fleabane in the RBCM herbarium is an exceptional case in point, although Bitter Daisy is easily distinguished by the presence of far more numerous and erect pistillate (ray) florets]:

- Rough-stemmed Fleabane (E. strigosus) and Diffuse Fleabane (E. divergens) are annual or biennial species and therefore lack a stout, branching stem base (the ray flowers of Diffuse Fleabane tend to be white but are sometimes blue).

- Cushion Daisy (E. poliospermus) has narrower, more hairy leaves and the stem leaves are absent or reduced upwards.

- Subalpine Daisy (E. peregrinus), Philadelphia Fleabane (E. philadelphicus), Showy Daisy (E. speciosus) and Triple-nerved Fleabane (E. subtrinervis) are readily distinguished because they tend to have much more ample stem leaves and are generally taller and more Aster-like.

- Smooth Daisy (Erigeron glabellus) has a weakly developed caudex, fibrous-rooted bases, and far more numerous rays (125–175); and lacks gland-tipped hairs.

- Long-leaved Fleabane (E. corymbosus) has long, narrow basal and stem leaves and an obvious double pappus consisting of an inner ring of 20-30 firm bristles surrounded by an outer ring of scales or much shorter bristles. While Leiberg’s Fleabane may have a double pappus, the inner ring will only have 12-16 bristles.

- Shaggy Fleabane (E. pumilus) has many more ray florets (50-100 or more) and the ray florets are usually narrower (< 1.5 mm wide). It has an obvious double pappus of 15-27 inner bristles and a well-developed outer ring of scales. The leaves of Shaggy Fleabane are rarely more than 8 mm wide while Leiberg’s Fleabane has leaves that are almost always wider. Shaggy Fleabane generally has more than five heads but reduced specimens may have fewer heads and thus be mistaken for a narrow-leaved form of Leiberg’s Fleabane unless the form and number of the ray florets and the presence of an obvious double pappus are noted. Leiberg’s Fleabane tends to occur at higher elevations than Shaggy Fleabane but there is some overlap in habitat conditions, at least in north-central Washington State.

Population spatial structure and variability

There is only one reported Canadian subpopulation (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2014) so there is no scope for genetic variation among Canadian subpopulations. There are no known studies of genetic variation between the Canadian population and subpopulations in the United States. There appear to be no geographical or ecological barriers to movement that might create genetic structure or strong demographic isolation between the populations in Canada and those in the U.S.

Designatable units

There is no information to suggest that there is more than one DU in Canada.

Special significance

Leiberg’s Fleabane is endemic to a small area of central Washington State and south-central British Columbia. It is not a particularly showy species and has not attracted interest from the horticultural industry.

Distribution

Global range

Leiberg’s Fleabane is endemic to the Cascade and Wenatchee mountains of Okanogan, Chelan and Kittitas counties in central Washington State and south-central British Columbia (Figure 5) (Nesom 2006). The species’ global range is approximately 10,380 km2.

Long description for Figure 5

Map of the global distribution of the Leiberg’s Fleabane, which occurs in the Cascade and Wenatchee mountains of Okanogan, Chelan and Kittitas counties in central Washington State and south-central British Columbia.

Canadian range

In Canada, Leiberg’s Fleabane occurs in the southernmost part of COSEWIC’s Southern Mountain National Ecological Area. The species has been confirmed from only one subpopulation, in the valley of the Ashnola River, approximately 25 km southwest of Keremeos, British Columbia (Figure 6; B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2014). This subpopulation, detected in 1980 (see below) has not been seen since. The range in Canada constitutes less than 1% of the species’ global range. If the Ashnola subpopulation has been extirpated this would constitute a 100% decline in the Canadian range over the past 35 years.

Long description for Figure 6

Map showing where the Leiberg’s Fleabane was found in the valley of the Ashnola River in 1980. Localities searched for the species in preparation for this report are also shown.

Extent of occurrence and area of occupancy

Although Leiberg’s Fleabane has been reported from two places in Canada, one of these reports, a 1985 collection (#963) by Van Dieren and Van Dieren was based on a misidentified specimen of Bitter Daisy (Erigeron acris) (Fairbarns pers. obs.).

Douglas and Douglas (collection #12015) collected Leiberg’s Fleabane from the valley of the Ashnola River on August 16, 1980Footnote1. A careful examination of G.W. Douglas’ field notes, in conjunction with topographic maps and a field visit to examine habitat conditions, suggests that the collection was made on dry, rocky, southeast-facing slopes at an elevation of approximately 1280 m, between km 43 and km 47 of the Ashnola River Road and almost directly above the Wall Creek trail footbridge.

The Canadian historical extent of occurrence was likely less than 1 ha as there is only a single record of the species and nothing in the herbarium label of collection notes to indicate that it was widespread where it was collected. If one assumes that Leiberg’s Fleabane has been extirpated from the locale where it was collected then there has been a 100% decline in the Canadian extent of occurrence over the past 35 years. The EOO is set at 4 km2, to be no smaller than the index of area of occupancy.

The Canadian historical index of area of occupancy (IAO), based on a single collection in the valley of the Ashnola River and represented by a single cell within a 2km x 2km grid, was 4 km2. If the population in the valley of the Ashnola River is presumed extirpated then there has been a 100% decline in the Canadian index of area of occupancy over the past 35 years.

Search effort

Fairbarns (pers. obs.) examined subpopulations in northern Washington State to gain insight into the habitat preferences of Leiberg’s Fleabane within the core of its distribution. The Canadian survey areas were selected as follows: air photography was examined to identify areas with extensive apparently suitable habitat:

- southeast-facing slopes,

- between 1,000 and 2,000 m elevation,

- no further east or west of known subpopulations in the United States, and

- no more than 20 km north of the U.S. border.

Road and trail maps were examined and areas that were estimated to be more than a 5 hour hike from the nearest accessible road were excluded from ground surveys because of the limited time available. Fairbarns spent 4 days searching suitable habitat from km 43 to km 47 of the Ashnola River Road. Because large and healthy subpopulations of Leiberg’s Fleabane occur on the Pacific Crest Trail approximately 35 km south of the Canadian border, he also spent 4 days searching suitable habitat in and near the northern terminus of the Pacific Crest Trail in Manning Provincial Park just north of the border. Fairbarns spent an additional 12 days searching other areas with potential habitat in the valley of the Ashnola River, in Manning Provincial Park, and in Cathedral Provincial Park. Dr. Robb Bennett, who helped Fairbarns search for and examine subpopulations of Leiberg’s Fleabane in Washington State, also assisted in searching portions of the valley of the Ashnola River and Cathedral Lakes Park, contributing approximately 4 more person-days to the search effort. In 2014, Ryan Batten spent one day searching at Spring Creek (R. Batten pers. comm. 2016). Despite these efforts, the subpopulation sampled by Douglas and Douglas in 1980 was not rediscovered and no new subpopulations were found. No searches were conducted in the drainage of the Pasayten River, which lies between the Ashnola River and Manning Park survey areas, because of the lack of ready access to potential habitat for Leiberg’s Fleabane.

The search area described in the previous paragraph has been a magnet for botanical exploration for at least the past 50 years. Numerous other botanists have examined the area and although it is not possible to quantify their search effort, over 2300 vascular plant collections from the area have been deposited at the Royal B.C. Museum (V) and University of British Columbia (UBC) herbaria.

Habitat

Habitat requirements

There is only one Canadian site reported for Leiberg’s Fleabane, in the valley of the Ashnola River. That subpopulation was found on an open southeast-facing montane slope at 1,280 m, according to collection notes. Douglas and Ratcliffe (1981) mention that the collection site was dry and rocky.

Collections from nearby sites in northern Washington State indicate that the species may occur at elevations varying from 188-2,600 m although the two lowest elevation collections (at 188 m and 369 m) were from atypical sites. The other 28 collections were made from sites at least 900 m above sea level. Most collections from northern Washington State were taken from open (occasionally lightly shaded) rock bluffs and ledges or rocky talus slopes (Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria 2014).

Habitat trends

There is abundant potential habitat within the Canadian range of Leiberg’s Fleabane. Potential habitat tends to occur in small patches within a matrix of productive forests. Recent forest cutblocks occupy approximately 60% of the southeast-facing slopes at elevations of 1,000-2,000 m within a 10 km radius of the apparent locale where Leiberg’s Fleabane was collected in Canada. As forests continue to be logged (see Threats), some of the rock bluffs and ledges that constitute potential habitat for Leiberg’s Fleabane are disturbed by activities related to logging, such as road building and slash piling (Fairbarns pers. obs.). There has also been extensive logging in potential habitat within the US range of Leiberg’s Fleabane (Fairbarns pers. obs.).

Habitat trends relating to logging, increasingly severe fire regimes, and invasive species are further discussed below (see Threats).

Biology

Leiberg’s Fleabane, apart from inclusion in taxonomic treatments of the genus, has not been the subject of botanical research. As a result, very little is known about its biology. Two closely related, narrowly endemic species, Cascade Fleabane (Erigeron cascadensis) and Oregon Fleabane (Erigeron oreganus), have also attracted little biological study. The large genus Erigeron encompasses species with very different life cycles, habitat preferences and ecologies, so it is unwise to infer detailed biological characteristics of Leiberg’s Fleabane from studies of more distantly related members of the genus, although broadly shared characteristics within the genus may be of some value.

Life cycle, demographic parameters and reproduction

Many species of Fleabane are capable of both sexual and asexual reproduction. Leiberg’s Fleabane is characterized by conspicuous (pistillate) ray florets and numerous small (perfect or pistillate) disc florets, attributes that suggest an outcrossing mating system (Noyes 2000). Semple (pers. comm. 2011) reported that Fleabane species are mostly outcrossers but some self-fertilization is possible.

Based on herbarium specimens and label data (Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria 2014) flowering may begin as early as June 2 and continue as late as August 23 while mature fruits may be evident as early as July 16 and still be present into September. In Canada, Leiberg’s Fleabane has been collected once (August 16, 1980). The specimens were collected in flower, which suggests that the Canadian population, as might be expected, flowers relatively late in the year compared to the US subpopulations.

There is no direct information on the persistence of seeds of Leiberg’s Fleabane in the soil nor is there any information regarding the period it takes plants to reach maturity, the average age of mature individuals, or the maximum age plants may attain. For these reasons, it is not possible to calculate the species’ generation time (the average age of parents of the current cohort). Generation time can be estimated at several years because these perennial plants tend to have a heavily branched caudex that likely takes several years to develop.

Physiology and adaptability

The physiology of Leiberg’s Fleabane has not been studied. As an herbaceous perennial species, Leiberg’s Fleabane survives winter cold by dying back to the ground.

There is no record of the species being grown to maturity in horticultural environments nor of attempts to plant out propagated Leiberg’s Fleabane into natural environments.

Dispersal and migration

The fruits of Leiberg’s Fleabane have a reduced pappus (Cronquist 1955) which is not sufficiently well developed to facilitate long-distance dispersal on breezes, unlike some members of the Asteraceae that produce long, capillary pappus bristles. The fruits of Willamette Fleabane (Erigeron decumbens), which are quite similar in size and form, are primarily wind-dispersed; Jackson (1996) estimated their mean dispersal distance at about 94 cm, and considered long-distance dispersal rare. The scarcity of Leiberg’s Fleabane within its Canadian range, despite the abundance of apparently suitable habitat, suggests that even over the long term the average dispersal distance is probably only a few hundred metres.

The Canadian population of Leiberg’s Fleabane may be severely fragmented according to standards established by IUCN Standards and Petitions Committee (2014). It is plausible to assume that Canadian subpopulation (if it still persists) contains too few individuals and occupies habitat patches too small to support a viable population. Accordingly, the small and isolated Canadian subpopulation of Leiberg’s Fleabane faces a high probability of extirpation, with a reduced probability of recolonization. For these reasons, the Canadian population of Leiberg’s Fleabane is possibly severely fragmented. However, with only the one known subpopulation and the possibility of others, it is not possible to be confident in this assessment.

Interspecific interactions

There is no information on interspecific interactions involving Leiberg’s Fleabane. The somewhat related Willamette Fleabane is a generalist with respect to pollinators (Clark et al. 1993) and the same is likely true of Leiberg’s Fleabane.

Population sizes and trends

Sampling effort and methods

Surveys were conducted within the areas described above (see DISTRIBUTION – Search Effort). The surveys were conducted in August, when the plants were most likely to be in flower. Surveys were conducted using the meander search approach typically followed for reconnaissance surveys in complex terrain. This involved walking through apparently suitable habitat, scanning for Leiberg’s Fleabane using binoculars to increase the effective survey area.

Abundance

No Canadian plants were found.

Fluctuations and trends

The only reliable report of Leiberg’s Fleabane in Canada is the Douglas and Douglas collection from 1980. There are no records of its abundance at the time of collection, either on the herbarium label or in Douglas’ field notes, nor was its abundance discussed in Douglas and Ratcliffe (1981).

Surveys in the vicinity of the original collection site did not result in the relocation of the subpopulation collected by Douglas and Douglas. Because it is impossible to search every suitable rock crevice in the vicinity of the original collection, Leiberg’s Fleabane could still persist in Canada. There is insufficient evidence to determine that the species has been extirpated from Canada since the 1980 collection was made.

Rescue effect

Leiberg’s Fleabane was formerly tracked as sensitive in Washington but recent investigations have shown that it is more secure than was formerly believed and it is no longer a conservation priority (Arnett pers. comm. 2015).

The nearest documented U.S. subpopulation is in the vicinity of Billy Goat Pass, approximately 20 km south of the Canadian border. The intervening area consists of high elevation ridges that provide nearly continuous rocky habitat likely suited to Leiberg’s Fleabane. There is, therefore, a plausible prospect of rescue.

Threats and limiting factors

Logging & wood harvesting (5.3)

Apart from protected areas such as Cathedral Provincial Park, most accessible forest land in the area where Douglas and Douglas collected Leiberg’s Fleabane has been logged (Figure 7). Areas of particularly steep terrain with loose soils remain unlogged. However, many rock ledges suited to Leiberg’s Fleabane occur as small habitat patches within forest cutblocks and are threatened both by logging and by associated activities such as road construction and slash piling. It is possible that forest harvesting could open up habitat for the species, as it occurs on open rock bluffs and ledges in Washington.

Long description for Figure 7

Aerial image of cutblocks along the Ashnola River, showing the approximate locality of the 1980 collection of the Leiberg’s Fleabane.

Fire and fire suppression (7.1)

In recent years, fires have swept through large areas of forest and woodland within the range of Leiberg’s Fleabane both in Canada and the U.S. In 2014, the Carlton Complex of fires (103,643 ha), was the largest wildfire in Washington State’s recorded history, surpassing the 1902 Yacolt Burn (O’Sullivan 2014; U.S. Forest Service 2014). In 2015, there were other large fires nearby, i.e., the Okanogan Complex and Chelan Complex (together 103,829 ha) (Toppo 2015; U.S. Forest Service 2015a,b). Both of these fires occurred within the relatively small range of Leiberg’s Fleabane in north-central Washington. Within Canada, the valley of the Ashnola River did not experience major fires in 2014 and 2015. There was a comparatively small 147 ha fire in habitat suited to Leiberg’s Fleabane on south-facing slopes above the Ashnola River Road, less than 15 km from the locale of the 1980 collection.

Forest fires have been a natural part of forest succession in the region but as climate changes summers are becoming warmer and drier. More severe fires are expected, exacerbated by the landscape homogenization resulting from widespread logging and fire suppression (Gedalof n.d.). There is no information on the response of Leiberg’s Fleabane to large scale forest fires but the recent occurrence of exceptionally extensive and intense fires within its range marks a change from the conditions under which it has persisted over the past century and the human-caused fire regime presents a plausible threat.

Invasive non-native/alien species (8.1)

Several invasive species occur in habitats where Leiberg’s Fleabane tends to occur, including Bull Thistle (Cirsium vulgare), Great Mullein (Verbascum thapsus), Common St. John’s-wort (Hypericum perforatum), Dalmatian Toadflax (Linaria genistifolia), and Cheatgrass (Bromus tectorum) (Fairbarns pers. obs.). Disturbances associated with timber extraction in the Ashnola River area tend to lead to an increase the distribution and abundance of invasive plants (Fairbarns pers. obs.) and climate change is anticipated to further exacerbate problems with invasive species (Dukes and Mooney 1999; Simberloff 2000; Kerns and Guo 2012).

Number of locations

There has only been one documented subpopulation of Leiberg’s Fleabane in Canada and the species could no longer be found in this location.

Protection, status and ranks

Legal protection and status

The Canadian population of Leiberg’s Fleabane is not protected under the federal Species at Risk Act or provincial species at risk legislation (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

Non-legal status and ranks

Leiberg’s Fleabane is ranked by NatureServe (2014) as G3? (globally vulnerable). In Canada it is ranked as N1 (critically imperilled) according to NatureServe (2014) and has a general status rank (Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council 2011) of 2: may be at risk. In Washington it is not ranked (SNR) but is no longer considered vulnerable (Arnett pers. comm. 2015).

In British Columbia Leiberg’s Fleabane is ranked S1 (critically imperilled). It is a priority two species under the B.C. Conservation Framework (Goal 3: maintain the diversity of native species and ecosystems) and is included on the British Columbia Red List, which consists of species that have been assessed as endangered, threatened or extirpated based on available information (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2014).

The 1997 IUCN Red List categorized Leiberg’s Fleabane as rare, based on reports that it was endangered in Canada and indeterminate (endangered, vulnerable or rare) in Washington State (Walter and Gillett 1998). It has subsequently been placed on the Watch List of the Washington State Natural Heritage program (2014).

Habitat protection and ownership

Although the precise location of the 1980 collection by Douglas and Douglas is uncertain, all plausible localities from which it might have been collected are provincial crown lands managed for forestry, although some plausible sites are inoperable areas within forest harvest lands.

Acknowledgements and authorities contacted

Robb Bennett, Shane Johnson and Shane Ford assisted with the fieldwork. Jenifer Penny and Marta Donovan (B.C. Conservation Data Centre) provided useful background information.

Authorities contacted

Lynda D. Corkum. COSEWIC Non-government Science Member. Department of Biological Sciences, University of Windsor.

Tim Birt. COSEWIC Non-government Science Member. Department of Biology, Queen's University.

Rick Page. COSEWIC Non-government Science Member, Page and Associates Environmental Solutions

Rhonda L. Millikin. A/Head Population Assessment, Pacific Wildlife Research Centre. Canadian Wildlife Service. Delta, British Columbia.

Robert Anderson, Canadian Museum of Nature.

Ruben Boles. Biologist, Species Assessment. Species Population and Standards Management, Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada.

Jennifer Doubt. Chief Collection Manager – Botany. Canadian Museum of Nature. Ottawa, Ontario.

Syd Cannings. Species at Risk Biologist. Northern Conservation Division, Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada.

Patrick Nantel. Conservation Biologist, Species at Risk Program. Ecological Integrity Branch, Parks Canada. Gatineau, Quebec.

David F. Fraser. Endangered Species Specialist, Ecosystem Branch, Conservation Planning Section. Ministry of Environment, Government of British Columbia. Victoria, British Columbia.

Jenifer Penny. Botanist. British Columbia Conservation Data Centre. Victoria, British Columbia.

Information sources

Arnett, J. pers. comm. 2015. Telephone conversation with M. Fairbarns. August 2015. Rare Plant Botanist, Washington Natural Heritage Program.

Batten, R. pers. comm. 2016. Email to Del Meidinger. August 2016.

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2014. BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer. B.C. Minist. of Environ. Victoria, B.C. Available: [accessed Jul 20, 2014].

Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council. 2011. Wild Species 2010: The General Status of Species in Canada. Website: http://www.wildspecies.ca/home.cfm?lang=e [accessed July 16, 2014].

Clark, D.L., K.K. Finley, and C.A. Ingersoll. 1993. Status report for Erigeron decumbens var. decumbens. Prepared for the Conservation Biology Program, Oregon Department of Agriculture. Salem, Oregon.

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria. 2014. Specimen data for Erigeron leibergii. University of Washington Herbarium, The Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture. Seattle, Washington. Website: [accessed: July 16, 2014].

Cronquist, A. 1955. Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest 5: Compositae. University of Washington Press. 343 pp.

Douglas, G. W., and M. J. Ratcliffe. 1981. Some rare plant collections, including three new records for Canada, from Cathedral Provincial Park, southern British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Botany 59: 1537-1538.

Dukes, J.S., and H.A. Mooney. 1999. Does global change increase the success of biological invaders? Trends in Ecology & Evolution 4:135-139.

Gedalof, Z., n.d. Fire and biodiversity in British Columbia. Web site: [accessed November 1, 2015].

IUCN Standards and Petitions Committee. 2014. Guidelines for using the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria : Version 11. Prepared by the Standards and Petitions Committee. Web site: http://jr.iucnredlist.org/documents/RedListGuidelines.pdf. [accessed July 16, 2014].

Jackson, S.A. 1996. Reproductive aspects of Lomatium bradshawii and Erigeron decumbens of the Willamette Valley, Oregon. M.Sc. Thesis, University of Oregon.

Kerns, B., and Q. Guo, 2012. Climate Change and Invasive Plants in Forests and Rangelands. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Climate Change Resource Center. Web site: [accessed November 1, 2015].

NatureServe. 2014. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Web site: [accessed July 20, 2014].

Nesom, G.L. 2006. Erigeron. In: Flora of North America Editorial Committee, eds. 1993+. Flora of North America North of Mexico. 16+ vols. New York and Oxford. Vol. 20.

O’Sullivan, J. 2014. Firefighting crews hunker down for long haul. Seattle Times July 21, 2014.

Noyes, R. D. 2000. Biogeographical and evolutionary insights on Erigeron and allies (Asteraceae) from ITS sequence data. Plant Systematics and Evolution 220: 93-114.

Semple, J.C. 2011. Personal conversation with Pamela Bailey. Director of Waterloo Herbarium, University of Waterloo, Ontario, CA. IN Bailey, P. 2013. Pollination Biology of the Endemic Erigeron lemmonii A. Gray, and its Insect Visitor Networks Compared to two Widespread Congeners Erigeron arisolius G.L. Nesom and Erigeron neomexicanus A. Gray (Asteraceae). Ph.D. thesis, University of Guelph.

Simberloff, D. 2000. Global climate change and introduced species in United States forests. The Science of the Total Environment 262: 253-261.

Toppo, G. 2015. Okanogan Complex fire the largest in Washington state history. USA Today, August 25, 2015.

U.S. Forest Service 2014. InciWeb: Carlton Complex. Web site: [accessed November 1, 2015].

U.S. Forest Service 2015a. InciWeb: Chelan Complex. Web site: [accessed November 1, 2015].

U.S. Forest Service 2015b. InciWeb: Okanogan Complex. Web site: [accessed November 1, 2015].

Walter, K.S. and Gillett, H.J. [eds] (1998). 1997 IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants. Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring Centre. IUCN - The World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. xiv + 862pp.

Washington Natural Heritage Program. 2014. Watch List of Vascular Plants. Web site: http://www1.dnr.wa.gov/nhp/refdesk/lists/watch.html [accessed July 16, 2014].

Biographical summary of report writers

Matt Fairbarns has a B.Sc. in Botany from the University of Guelph (1980). He has worked on rare species and ecosystem mapping, inventory and conservation in western Canada for approximately 30 years.

Collections examined

Collections at the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University, University of Victoria, Pacific Forestry Centre, University of Washington, Washington State University and University of Idaho were consulted through the online database of the Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria (2007-2011).

Two specimens at the Royal British Columbia Museum (V140678 and V156882) were examined and the latter specimen was re-identified as Bitter Daisy.