COSEWIC Assessment and Status Report on the Little Quarry Lake Benthic Threespine Stickleback Gasterosteus Aculeatus and the Little Quarry Lake Limnetic Threespine Stickleback Gasterosteus Aculeatus in Canada - 2015

- Document Information

- COSEWIC Assessment Summary

- COSEWIC Executive Summary

- Technical Summary - Little Quarry Lake Benthic Threespine Stickleback

- Technical Summary - Little Quarry Lake Limnetic Threespine Stickleback

- COSEWIC History

- COSEWIC Mandate

- COSEWIC Membership

- Definitions (2015)

- Wildlife Species Description and Significance

- Distribution

- Habitat

- Biology

- Population Sizes and Trends

- Threats and Limiting Factors

- Protection, Status and Ranks

- Acknowledgements and Authorities Contacted

- Information Sources

- Biographical Summary of Report Writer(s)

- Collections Examined

- Figure 1. (A) Little Quarry Lake Benthic Threespine Stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) illustrating 25 landmarks (red dots) used in morphometric analyses. (B) Little Quarry Lake Limnetic Threespine Stickleback with the same landmarks.

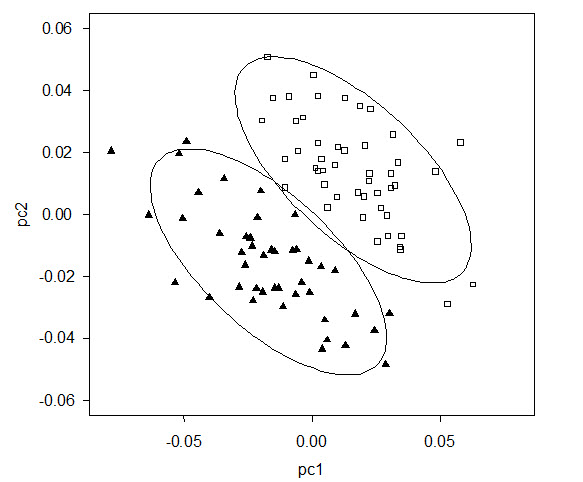

- Figure 2. The two clusters identified by MCLUST analyses of shape carried out on Threespine Stickleback samples from Little Quarry Lake. Each symbol indicates the position of an individual fish along the first two principal components of variation among landmark coordinates. Closed triangles indicate fish classified as Limnetic and open squares are fish classified as Benthic. Ellipses encircle about 90% of the measurements present in each cluster, assuming a Gaussian frequency distribution of measurements.

- Figure 3. Shape change between Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks within the three extant species pairs. The base of each arrow indicates the mean position of the corresponding landmark in the Limnetic. Arrows indicate the direction and magnitude of change in landmark position from this Limnetic shape to the mean shape of the Benthic. The length of each arrow was multiplied by two to increase visibility. Little Quarry Lake N = 93 collected 2007; Priest Lake N = 65 and Paxton Lake N = 70 collected 2005.

- Figure 4. The average proportion of ancestry of individual adult Threespine Stickleback in the Benthic population (qb(i)) estimated by STRUCTURE (K = 2) for all samples analysed from Little Quarry Lake (N = 93) species pair in 2007. The distribution of individual genetic admixture values (ranging from 0 to 1 between Limnetics and Benthics) is strongly bi-modal, indicating that hybridization between Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks is rare in Little Quarry Lake.

- Figure 5. Distribution of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback is restricted to Little Quarry Lake in Canada. Current and historical distributions are identical, as are global and Canadian ranges.

- Table 1. Estimates of mature Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback. These are based on a single mark-recapture estimate of mature Benthic and Limnetic males in Paxton Lake in June 2005. All estimates, including 95% confidence intervals, are calculated by multiplying the Paxton Lake estimates by a factor that corrects for lake perimeter, and then multiplying by two to account for both sexes. (Source: modified from COSEWIC 2010a and Recovery Team for Non-Game Freshwater Fish Species in British Columbia (2013)).

- Table 2. Authorities contacted during the preparation of this report.

COSEWIC

Committee on the Status

of Endangered Wildlife

in Canada

COSEPAC

Comité sur la situation

des espèces en péril

au Canada

COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows:

COSEWIC. 2015. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Little Quarry Lake Benthic Threespine Stickleback and the Little Quarry Lake Limnetic Threespine Stickleback Gasterosteus aculeatus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xiii + 37 pp.

COSEWIC acknowledges Jennifer Gow for writing the status report on the Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus,in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This status report was overseen and edited by Dr. Eric Taylor, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Specialist Subcommittee.

COSEWIC Secretariat

c/o Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment and Climate Change Canada

Ottawa, ON

K1A 0H3

Tel.: 819-938-4125

Fax: 819-938-3984

E-mail: COSEWIC E-mail

Website: COSEWIC

Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur L'épinoche à trois épines benthique du lac Little Quarry et l'Épinoche à trois épines limnétique du lac Little Quarry (Gasterosteus aculeatus) au Canada.

Little Quarry Lake Benthic Threespine Stickleback and Little Quarry Lake Limnetic Threespine Stickleback - Cover photo of Little Quarry Lake Benthic (upper) and Limnetic (lower) Threespine Sticklebacks from Little Quarry Lake. The scale bar is 1 cm (used with permission from E. Taylor).

Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks are one of three extant species pairs of Threespine Stickleback that live in sympatry. In each pair, Benthics eat mainly benthic invertebrates in the littoral zone while Limnetics primarily feed on plankton in open water. Each has traits adapted to their feeding lifestyle; for example, Benthics have a greater overall body depth, shorter dorsal and anal fins, a smaller eye, and a shorter jaw that is more downward-oriented. Most Little Quarry Lake Benthics also lack a pelvic girdle. Molecular genetic evidence strongly supports the independent evolution of each pair in different lakes, despite their similar appearances. Thus, a stickleback species pair from one watershed is genetically and evolutionarily distinct from pairs in other watersheds. Little Quarry Lake Benthics and Limnetics are genetically distinct from one another, and hybridization between them occurs naturally in the wild at a low level. They have high scientific value and are only found in Canada. The Threespine Stickleback Benthic and Limnetic species pairs are among the most extensively studied examples of ecological speciation in nature, giving insight into the processes that give rise to Canada's biodiversity.

The geographic distribution of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks is highly restricted; they are found in one lake, Little Quarry Lake, on Nelson Island, southwestern British Columbia.

In general, Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks habitat needs include vegetated littoral habitat and pelagic areas of lakes with gently sloping sediment (e.g., silt, sand, gravel) beaches for spawning. The species pairs do not appear to have a specific suite of abiotic factors or habitat structure that sets them apart from solitary Threespine Sticklebacks inhabiting other lakes. The habitat requirements for the Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pair include features of the environment that prevent hybridization, such as littoral zone vegetation and adequate light penetration for nest building and mate selection, respectively. That is, Benthic and Limnetic species pairs require habitat features needed to maintain mate recognition and reproductive barriers between the two species, in addition to those needed to maintain a viable population of either species.

There has been almost no direct study of the biology of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks. They are assumed to be ecologically and behaviourally similar to the other Benthic-Limnetic species pairs that have been studied extensively. Their reproductive biology is assumed to be similar to that of other freshwater Threespine Stickleback, with some spatial and temporal segregation between Benthics and Limnetics: Benthics build their nests under cover of macrophytes or other structures while Limnetics tend to spawn in more open habitat; Benthics begin reproducing earlier in the year than Limnetics, although there is considerable overlap in spawning times. There is also strong assortative mating between them. Combined, these factors result in low levels of hybridization.

A simple fish community appears to be a major ecological determinant of where Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs are found; relatively low to absent interspecific competition and predation is likely key to their diversification into species pairs and their persistence.

There have been no direct population estimates of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback. A coarse estimate of abundance of adult Benthics and Limnetics can be extrapolated from a mark-recapture study conducted on another Benthic-Limnetic species pair. This gives rudimentary estimates of between 5,319 to 12,581 for Benthics and 61,212-199,203 mature individuals for Limnetics, respectively.

The relatively small littoral zone and small amounts of macrophyte coverage in Little Quarry Lake are likely limiting factors to Benthics and Limnetics. Productivity may also be a limiting factor in this lake. The primary threat to Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks comes from the introduction of non-native species that could prey on them and/or disrupt the habitat requirements of the species pair. The imminence of this threat is uncertain, but the consequences would probably be disastrous. Little Quarry Lake's relatively remote location likely offers some protection, although remoteness did not prevent the introduction of the exotic Brown Bullhead (and subsequent extinction of a Benthic-Limnetic species pair) in a lake of comparable accessibility, Hadley Lake. Habitat threats from water extraction by local oceanside residents for domestic use, and land-based development e.g., forest harvesting, appear to have been limited to date. Excessive scientific collecting activities also constitute a potential threat.

The Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine have not been assigned a Global Heritage Status rank, nor has their general status been assessed at the national or provincial level. The Canadian federal Fisheries Act (Section 35)does not provide habitat protection provisions for Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks. Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks are not currently managed under the BC Sport Fishing regulations. Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks are afforded some protection in British Columbia under the provincial Wildlife Act, whichenables provincial and territorial authorities to license anglers and angling guides, and to regulate scientific fish collection permits. Collecting guidelines that limit lethal and non-lethal sampling of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks and restrict all sampling to half of the lake have been developed. Almost all lands adjacent to Little Quarry Lake are Crown Land. Little Quarry Lake fish are, therefore, afforded some protection from the BC Forest and Range Practices Act as well as the provincial Riparian Areas Regulation.

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Generation time (inferred from research on other Benthic Limnetic Threespine Stickleback pairs; no specific data exists for Little Quarry Lake) | 1-3 yrs |

| Is there a continuing decline in number of mature individuals? | Unknown |

| Estimated percent of continuing decline in total number of mature individuals within 5 years. | Not applicable |

| Percent change in total number of mature individuals over the last 10 years. | Unknown |

| Percent change in total number of mature individuals over the next 10 years. Likely to be 100% if an invasive species is introduced. Benthic and limnetic sticklebacks became extinct after introduction of invasive species in two other lakes within 10 years. | Unknown |

| Percent change in total number of mature individuals over any 10 years period, over a time period including both the past and the future. | Unknown |

| Are the causes of the decline clearly reversible and understood and ceased? | Not applicable |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals? Very few direct observations of population ecology. |

Unknown |

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Estimated extent of occurrence | 8 km2 |

| Index of area of occupancy (IAO) (Always report 2x2 grid value). |

8 km2 |

| Is the population severely fragmented? | No |

| Number of locations (Endemic to a single lake) |

1 |

| Is there a continuing decline in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Is there a continuing decline in index of area of occupancy? | No |

| Is there a continuing decline in number of populations? | No |

| Is there a continuing decline in number of locations? (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.) |

No |

| Is there a continuing decline in area, extent and/or quality of habitat? Baseline information has only recently been collected. |

Unknown |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of populations? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of location? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in index of area of occupancy? | No |

| Population | N Mature Individuals |

|---|---|

| Estimate for range of abundance for mature Benthic Threespine Stickleback extrapolated from a single mark-recapture estimate of mature Benthic males from Paxton Lake in June 2005. Extrapolation assumes a 1:1 sex ratio and corrects for lake perimeter, but not other biotic or abiotic differences between lakes. | 5,319 - 12,581 (95% CI, mean = 7,900) |

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Probability of extinction in the wild is at least 20% within 20 years or 5 generations, or 10% within 100 years. | Unknown |

- Introduction of predatory non-native species. The imminence of this threat is uncertain, but the consequences can be disastrous; empirical observations indicate that the probability of extinction of species pairs in the presence of non-natives is 1.0 (2 of 2 cases).

- Habitat loss and degradation from water extraction for domestic water and land-based development e.g., forestry.

- Collection for scientific research (i.e., those that exceed guidelines (Recovery Team for Non-Game Freshwater Fish Species in BC 2013)).

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status of outside population(s)? This is an endemic wildlife species |

Not applicable |

| Is immigration known or possible? | No |

| Would immigrants be adapted to survive in Canada? | Not applicable |

| Is there sufficient habitat for immigrants in Canada? | Not applicable |

| Is rescue from outside populations likely? Endemic species pair |

Not applicable |

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Is this a data sensitive species? Their biology and occurrence in a single small lake makes them especially vulnerable to introduction of non-native species. |

No. |

COSEWIC: designated Threatened in November 2015.

| Generation time (inferred from research on other Benthic Limnetic Threespine Stickleback pairs; no specific data exists for Little Quarry Lake) | 1-3 yrs |

| Is there a continuing decline in number of mature individuals? | Unknown |

| Estimated percent of continuing decline in total number of mature individuals within 5 years. | Not applicable |

| Percent change in total number of mature individuals over the last 10 years. | Unknown |

| Percent change in total number of mature individuals over the next 10 years. Likely to be 100% if an invasive species is introduced. Benthic and limnetic sticklebacks became extinct after introduction of invasive species in two other lakes within 10 years. | Unknown |

| Percent change in total number of mature individuals over any 10 years period, over a time period including both the past and the future. | Unknown |

| Are the causes of the decline clearly reversible and understood and ceased? | Not applicable |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals? Very few direct observations of population ecology. |

Unknown |

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Estimated extent of occurrence | 8 km2 |

| Index of area of occupancy (IAO) (Always report 2x2 grid value). |

8 km2 |

| Is the population severely fragmented? | No |

| Number of locations (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.) (Endemic to a single lake) |

1 |

| Is there a continuing decline in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Is there a continuing decline in index of area of occupancy? | No |

| Is there a continuing decline in number of populations? | No |

| Is there a continuing decline in number of locations? | No |

| Is there a continuing decline in area, extent and/or quality of habitat? Baseline information has only recently been collected. |

Unknown |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of populations? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of location? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in index of area of occupancy? | No |

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Population | N Mature Individuals |

| Estimate of range of abundance for mature Limnetic Threespine Stickleback extrapolated from a single mark-recapture estimate of mature Limnetic males from Paxton Lake in June 2005. Extrapolation assumes a 1:1 sex ratio and corrects for lake perimeter, but not other biotic or abiotic differences between lakes. | 61,212-199,203 (95% CI, mean = 108,763) |

- Introduction of predatory, non-native species. The imminence of this threat is uncertain, but the consequences could be disastrous; empirical observations indicate that the probability of extinction of species pairs in the presence of non-natives is 1.0 (2 of 2 cases).

- Habitat loss and degradation from water extraction for domestic water and land-based development e.g., forestry.

- Collection for scientific research (i.e., those that exceed guidelines (Recovery Team for Non-Game Freshwater Fish Species in BC 2013)).

| Status of outside population(s)? This is an endemic wildlife species | Not applicable |

| Is immigration known or possible? | No |

| Would immigrants be adapted to survive in Canada? | Not applicable |

| Is there sufficient habitat for immigrants in Canada? | Not applicable |

| Is rescue from outside populations likely? Endemic to a single lake |

Not applicable |

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Is this a data sensitive species? Their biology and occurrence in a single small lake make them especially vulnerable to introduction of non-native species. |

No |

COSEWIC: designated Threatened in November 2015.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) was created in 1977 as a result of a recommendation at the Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference held in 1976. It arose from the need for a single, official, scientifically sound, national listing of wildlife species at risk. In 1978, COSEWIC designated its first species and produced its first list of Canadian species at risk. Species designated at meetings of the full committee are added to the list. On June 5, 2003, the Species at Risk Act (SARA) was proclaimed. SARA establishes COSEWIC as an advisory body ensuring that species will continue to be assessed under a rigorous and independent scientific process.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assesses the national status of wild species, subspecies, varieties, or other designatable units that are considered to be at risk in Canada. Designations are made on native species for the following taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, arthropods, molluscs, vascular plants, mosses, and lichens.

COSEWIC comprises members from each provincial and territorial government wildlife agency, four federal entities (Canadian Wildlife Service, Parks Canada Agency, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the Federal Biodiversity Information Partnership, chaired by the Canadian Museum of Nature), three non-government science members and the co-chairs of the species specialist subcommittees and the Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge subcommittee. The Committee meets to consider status reports on candidate species.

The Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, provides full administrative and financial support to the COSEWIC Secretariat.

Phylum: Chordata

Class: Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes)

Order: Gasterosteiformes

Benthic Species: Gasterosteus aculeatus

Limnetic Species: Gasterosteus aculeatus

English common name:

Little Quarry Lake Benthic Threespine Stickleback

Little Quarry Lake Limnetic Threespine Stickleback

French common name:

Épinoche à trois épines benthique du lac Little Quarry

Épinoche à trois épines limnétique du lac Little Quarry

The Threespine Stickleback is a small-bodied fish, rarely exceeding 80 mm in total length and typically being between 40 and 60 mm total length. They are easily recognized by the presence of three (sometimes two) isolated dorsal spines followed by a soft-rayed dorsal fin with 9-12 rays. The caudal fin is truncate and the pectoral fins are fan-shaped and located about half-way up the side of the body. The pelvic fins are modified into a single spine on either side of the body. Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks are morphologically distinct from one another (Figure 1), and fall into two distinct clusters (Figure 2). They are, however, remarkably similar in shape to other Benthic or Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks (Figure 3). Indeed, the magnitude of the morphological shifts between Benthics and Limnetics within lakes is closely correlated between all three extant Threespine Stickleback species pairs (mean r = 0.72 +/- 0.1; Gow et al. 2008). The most notable shifts from the limnetic shape to the benthic shape include:

- a greater overall body depth

- shorter dorsal and anal fins

- a smaller eye

- and a shorter jaw that is more downward-oriented

These differences are considered adaptations to their divergent feeding lifestyle: Benthics eat mainly benthic invertebrates in the littoral zone while Limnetics primarily exploit plankton in open water (Schluter and McPhail 1992, 1993).

Little Quarry Lake Benthics exhibit a high frequency of individuals lacking a pelvic girdle (90%). This is an unusual characteristic among Threespine Sticklebacks. Partial or complete loss of pelvic structures has only been documented in two dozen or so freshwater stickleback populations globally (Bell 1987), and Paxton Lake Benthics are the only other Benthic-Limnetic Threespine Stickleback (extant and extinct) with this atypical feature (McPhail 1992). Little Quarry Lake Limnetics do have a pelvic girdle (Figure 1). Selection forces thought to contribute to the evolution of pelvic-reduction in stickleback populations include the absence of gape-limited predatory fish, limited calcium availability, and predation by grasping insects (Reimchen 1980; Giles 1983; Bell et al. 1993; Marchinko 2009).

As with most freshwater Threespine Stickleback populations (Bell and Foster 1994), Little Quarry Lake Benthics and Limnetics develop bright red throats during the breeding season (Gow pers. obs. 2007)

Long description for Figure 1

Images of two Little Quarry Lake Threespine Sticklebacks, with the Benthic form above and the Limnetic form below. Each image is overlain with points illustrating 25 landmarks used in morphometric analyses.

Long description for Figure 2

Chart (scatter plot) illustrating the results of cluster (MCLUST) analysis of shape carried out on Threespine Sticklebacks from Little Quarry Lake. Each symbol indicates the position of an individual fish along the first two principal components of variation among landmark coordinates. Two types of symbol are used to distinguish fish classified as Limnetic from those classified as Benthic. Ellipses surround about 90 percent of the measurements present in each cluster, assuming a Gaussian frequency distribution of measurements.

Long description for Figure 3

Three fish-shaped diagrams representing Threespine Stickleback from each of Little Quarry Lake, Paxton Lake, and Priest Lake. The diagrams outline the main morphological features. Superimposed on these diagrams are arrows, the bases of which indicate the mean position of the corresponding landmark in the Limnetic form. The arrows show the direction of change in the landmark position from the Limnetic shape to the mean Benthic shape, with the length of the arrows indicating the magnitude of the change.

Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs have evolved recently from their marine ancestors following the end of the last glaciation, just 13,000 years ago (McPhail 1993, 1994). Genetic evidence strongly supports the independent evolution of each pair (Taylor and McPhail 1999, 2000; Jones et al. 2012), although details of each pairs' origin are still not well understood.

Earlier geological evidence suggested that two, temporally spaced post-glacial marine submergences inundated coastal British Columbia lakes in the vicinity of the species pairs (Mathews et al. 1970). This contributed to the idea that the same marine Threespine Stickleback species had colonized each lake twice at intervals (the "double invasion hypothesis"; Schluter and McPhail 1992; McPhail 1993; Taylor and McPhail 1999, 2000). More exhaustive geological analysis, however, does not support a second postglacial sea level rise in this region of sufficient magnitude to enable a second invasion (Hutchinson et al. 2004) and, therefore, the scenario for the origin of the pairs based on it.

The genetic evidence that supports the double invasion hypothesis cannot be disentangled from other possibilities, such as differences in effective population sizes between Benthics and Limnetics (Taylor and McPhail 1999, 2000; Jones et al. 2012). The most recent and extensive genetic study to date does, however, suggest that allopatric adaptive divergence (such as could be generated by separate invasions of coastal lake habitats by marine sticklebacks) and reuse of standing genetic variation has played a role in the repeated evolution of the Benthic and Limnetic species pairs (Jones et al. 2012).

The distinct Benthic and Limnetic morphological clusters identified within Little Quarry Lake are associated with strong genetic distinction between Benthics and Limnetics (microsatellite markers, Gow et al. 2008; SNPs, Jones et al. 2012). Genetic analyses also indicate little interbreeding between them (Figure 4); few individuals carry a signature of hybridization (a direct mating between Benthics and Limnetics) or admixture (genetic blending resulting from generations of mixed mating between the two forms and their hybrids). This is convincing evidence that premating, postmating, or both kinds of reproductive isolation between Little Quarry Lake Benthics and Limnetics are strong, i.e., Benthics and Limnetics do not tend to mate with one another, or if they do, selection against hybrids is strong (Gow et al. 2007).

The low level of genetic admixture shown in the Little Quarry Lake species pair (0.04) is remarkably similar to that observed in the other extant Benthic-Limnetic species pairs; mean hybridity values do not vary significantly among them (Gow et al. 2008). (Hybridity is an estimate of genetic mixing that ranges from 0 for pure Benthics or Limnetics to 0.5 for first generation hybrids between them).

Long description for Figure 4

Bar chart plotting the average proportion of ancestry of individual adult Threespine Sticklebacks in the Benthic population for all samples analysed from the Little Quarry Lake species pair in 2007. The distribution of individual admixture values is strongly bimodal, indicating that hybridization between Benthic and Limnetic forms is rare in that lake.

The Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks from Little Quarry Lake each warrant status as a separate designatable unit (DU) within Gasterosteus aculeatus because they satisfy the "discrete" and "significance" criteria of COSEWIC (COSEWIC 2011). The basis for designatable unit status for Benthics and Limnetics rests, crucially, on their sympatric occurrence with one another so it is appropriate and important that the status of both members of the pair be assessed in the same report.

They are discrete:

- Data from neutral genetic markers and inherited traits (microsatellites and morphometrics (Gow et al. 2008), SNPs (Jones et al. 2012)) provide strong support that they are genetically distinct from one another and from other Threespine Sticklebacks.

They are evolutionarily significant:

- They are one of three existing cases (occurring in three different watersheds on two different islands) of sympatric species pairs in Gasterosteus aculeatus despite the sampling of hundreds of coastal lakes in this region and globally (Bell and Foster 1994; McPhail 1994; Gow et al. 2008).

- All three sets of species pairs evolved independently from one another (Taylor and McPhail 2000; Jones et al. 2012). The Little Quarry Lake sympatric pair was, therefore, the result of a unique evolutionary divergence. There is evidence that an unusual combination of evolutionary history and ecological setting has driven these unique divergences (Taylor and McPhail 2000; Ormond et al. 2011; Jones et al. 2012).

In summary, the Benthic and Limnetic sticklebacks in Little Quarry Lake act as distinct biological species (they are genetically, ecologically, and morphologically distinct in sympatry), even if they have not yet been formally described taxonomically. Consequently, they merit recognition as two DUs independent from G. aculeatus as a whole.

The significance of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks lies primarily with their scientific value and unique contribution to Canada's biodiversity as endemics. Since the first description of Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks (McPhail 1984), these sympatric species pairs have become an important example of recent parallel evolution in nature. Indeed, these young species pairs are widely held as scientific treasure; repeatable patterns of population divergence along similar environmental gradients offer some of the strongest evidence that population divergence has, indeed, been driven by natural selection. These species pairs are now among the most extensively studied systems of ecological speciation in nature, giving insight into the processes that give rise to the biodiversity we see around us (reviewed in Rundle and Nosil 2005; Nosil and Schluter 2011; Taylor et al. 2013; Seehausen et al. 2014).

Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks now represent one third of these known extant species pairs. Even though they were described just six years ago (Gow et al. 2008), they are already the subject of research in this area (Ormond et al. 2011; Jones et al. 2012).

There is no direct commercial value to Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks.

Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks are highly restricted in their geographic distribution; they are found only in an unnamed lake alias "Little Quarry Lake" (herein referred to as Little Quarry Lake), on Nelson Island, in the central Strait of Georgia region in southwestern British Columbia (BC, Figure 5).

Other, independently evolved extant Benthic-Limnetic species pairs are found in two watersheds on Texada Island, BC; one in the Vananda Creek watershed, the other in Paxton Lake (McPhail 1992, 1993). Another pair found in Enos Lake on southeastern Vancouver Island, BC has collapsed into a hybrid swarm with few or no Limnetics or Benthics remaining (Kraak et al. 2001; Gow et al. 2006; Taylor et al. 2006; Behm et al. 2010). A fifth pair, in Hadley Lake on Lasqueti Island, BC is extinct (Hatfield 2001).

Long description for Figure 5

Map of the global distribution of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks, which are found only in an unnamed lake referred to as "Little Quarry Lake" on Nelson Island, in the central Strait of Georgia region in southwestern British Columbia.

Because Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks are endemic to Canada, their Canadian and global ranges are identical (Figure 5).

The extent of occurrence (EOO) and index of area of occupancy (IAO) were estimated for Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks according to the COSEWIC guidelines (i.e., using the minimum convex polygon method for EOO, and using an overlaid grid of 2 km² cells for IAO). Because the minimum convex polygon calculation of EOO was less than the IAO value, both the EOO and IAO of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks are 8 km2 based on a 2x2 km grid calculation.

Threespine Sticklebacks are common in coastal marine and freshwaters throughout the Northern Hemisphere. Physically isolated populations exist in numerous low-elevation lakes. Many hundreds of these lakes have been surveyed for Threespine Stickleback along the British Columbia, Washington and Alaska coasts, and many more throughout their global range (e.g., Bell and Foster 1994). Within Canada alone, extensive surveys have been conducted particularly along coastal British Columbia over more than four decades (e.g., Berner et al. 2009, McPhail 1994, Moodie and Reimchen 1976; Reimchen et al. 1985; Reimchen 1994; Spoljaric and Reimchen 2007). Globally, sympatric Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs have been discovered in just five lakes, all within a highly confined geographic area in southwestern British Columbia (McPhail 1994; Gow et al. 2008). The Little Quarry Lake species pair was recently discovered within this area during a survey of lakes on Nelson Island, BC (Gow et al. 2008).

Little Quarry Lake is similar to other Threespine Stickleback species pair lakes in many attributes: its elevation (53 m), perimeter (2600 m), surface area (22 ha) and maximum depth (21 m) all lie within the range of other species pair lakes (Ormond et al. 2011). They are all connected to the sea by a high gradient stream. At 285 m from the sea, however, Little Quarry Lake has the shortest distance connecting it to marine waters of any species pair lake (Ormond et al. 2011). This steep stream is now dammed. Prior to this, it is unlikely that it was routinely accessible to anadromous marine Threespine Stickleback (Schluter pers. comm.). Little Quarry Lake has a single inlet stream (Figure 5).

Despite these similarities among lakes harbouring Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs, they do not appear to have a specific suite of abiotic factors that sets them apart from other freshwater lakes. For example, lake size, relative littoral area and water chemistry do not differ significantly between their lakes and comparable lakes harbouring solitary Threespine Stickleback populations (those composed of just a single form; Ormond et al. 2011). Similarly, there is no significant difference in the habitat structure; emergent and submerged macrophyte abundance does not vary substantially between species pair and comparable non-species pair lakes (Ormond et al. 2011).

Nevertheless, Benthic and Limnetic species pairs are much more sensitive to habitat and environmental changes than their solitary freshwater counterparts. As evolutionary young species, they can still produce viable hybrids. That is, they are not intrinsically reproductively isolated from one another (e.g., by genomic incompatibilities). Instead, premating reproductive isolating barriers prevent the two forms from frequently interbreeding, and there is post-zygotic selection against hybrids in nature (Gow et al. 2007). The potential for environmental changes that disrupt these barriers and increase hybridization has long been appreciated in fishes (Hubbs 1955) and could cause the breakdown of a species pair into a hybrid swarm. Indeed, this has occurred in Enos Lake following the introduction of the American Signal Crayfish (Pascifasticus leniusculus; Gow et al. 2006; Taylor et al. 2006; Behm et al. 2010). Consequently, the habitat requirements for Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs include features of the environment that prevent hybridization and maintain selection against them, as well as features that may limit the size or viability of any Threespine Stickleback population (e.g., juvenile rearing area, nesting habitat area). That is, Benthic and Limnetic species pairs require habitat features needed to maintain mate recognition and reproductive barriers between the two species, and selection against hybrids in addition to those needed to maintain a viable population (National Recovery Team for Stickleback Species Pairs 2007; Hatfield 2009).

Their habitat needs probably include sustained littoral and pelagic productivity, absence of invasive species, maintenance of gently sloping sediment (e.g., silt, sand, gravel) beaches and natural littoral macrophytes, and natural light transmissivity (National Recovery Team for Stickleback Species Pairs 2007; Hatfield 2009). The latter two are considered particularly important for maintaining mate recognition and reproductive barriers (Hatfield 2009).

Compared to other Benthic and Limnetic species pair lakes, Little Quarry Lake has low values for several abiotic parameters:

- The lowest levels of water conductivity (25 µS/cm), alkalinity (3.7 mg/L), dissolved inorganic carbon (<0.5 mg/L) and total dissolved solids (24 mg/L) in Little Quarry Lake of any Benthic Limnetic species pair lake (Ormond et al. 2011, Jesson pers. comm., Lunn pers. comm.). This suggests that high productivity per se is not a prerequisite to the persistence of this species pair.

- The relative littoral area (< 3m depth) is notably smaller (2.2 %) than other species pair lakes (18-59 %; Ormond et al. 2011). Indeed, the lake bottom tends to drops off steeply from shore leaving little littoral area (Gow pers. obs., Jesson pers. comm., Lunn pers. comm.). This area encapsulates the majority of macrophytes (Ormond et al. 2011) and stickleback breeding habitat (McPhail 1994; Hatfield and Schluter 1996); it is the most important habitat for Benthic sticklebacks and is required for the reproduction of both forms.

On the other hand, Little Quarry Lake has the highest dissolved oxygen saturation in the hypolimnion (63.2%) of any Benthic and Limnetic (others range from 14.0% to 38.1%; Ormond et al. 2011).

The high gradient outlet stream from Little Quarry Lake has been blocked by an earthen dam, likely for over 50 years (Bristol pers. comm.). This dam is believed to have raised the water level in the lake by about 1.5 m (Bristol pers. comm.). Other trends in habitat quantity and quality in Little Quarry Lake cannot be assessed as there has been no long-term monitoring from this lake. The baseline data that has been collected recently from Little Quarry Lake (Ormond et al. 2011) will enable future monitoring of habitat trends. The land surrounding the lake is forested, with no roads, residences or other development. The shoreline is composed of mixed Douglas fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii) and Arbutus and has numerous bedrock outcrops (Gow pers. obs; Jesson pers. comm., Lunn pers. comm. 2014).

There has been almost no direct study of the biology of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback. They may be ecologically and behaviourally similar to the other species pairs in Paxton Lake and Enos Lake (prior to its collapse), whose wild and laboratory-reared populations have been studied extensively. The detailed descriptions of these are presented in their respective COSEWIC Status Reports (COSEWIC 2010a; COSEWIC 2012), and are briefly summarized here. Any information pertaining directly to Little Quarry Lake is identified.

Nevertheless, it is important to note that the biology of Little Quarry Lake Benthics and Limnetics may vary from other species pairs in some regards. Differences in physical and chemical attributes between Little Quarry Lake and the other Benthic-Limnetic species pair lakes (see Habitat Requirements section) may give rise to differences in e.g., habitat use.

The reproductive biology of Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback is largely similar to other freshwater Threespine Stickleback (McPhail 1994, 2007): Males construct nests, which they guard and defend, until fry are about a week old. Eggs take up to a week to hatch, depending on temperature, and another three to five days before larvae are free-swimming.

There is some spatial and temporal segregation between Benthics and Limnetics: Benthics build their nests under cover of macrophytes or other structures while Limnetics tend to spawn in more open habitat (Ridgway and McPhail 1984; McPhail 1994; Hatfield and Schluter 1996); Benthics begin reproducing earlier in the year than Limnetics although there is considerable overlap in spawning times (National Recovery Team for Stickleback Species Pairs 2007). There is also strong assortative mating between them (Ridgway and McPhail 1984; Nagel and Schluter 1998; Boughman 2001). Combined with selection against hybrids (Gow et al. 2007), these factors likely result in the low proportions of adult hybrids observed between Little Quarry Lake Benthics and Limnetics (Gow et al. 2008).

Benthic and Limnetic sticklebacks have similar life histories (McPhail 1993,1994). Limnetics are thought to mature on average as one-year-olds, and rarely live beyond a single breeding season: females produce multiple clutches in quick succession, and males mate with multiple females, and may nest more than once within a single breeding season. Benthics delay sexual maturation relative to Limnetics; many do not mate until they are two-year-olds and go on to mate across several breeding seasons. Benthic females are thought to produce fewer clutches within a breeding season than Limnetics, although males may still mate with multiple females, and may nest more than once within a single breeding season.

Immediately after leaving the nest, both Benthic and Limnetic fry use inshore areas, where there is abundant food and cover from predators. Eventually Limnetics move offshore to feed in pelagic areas (Bentzen et al. 1984; Schluter 1995). The timing of this movement is likely dictated by a combination of relative growth rates and predation risk in littoral and pelagic habitats (Schluter 2003). Benthics remain in littoral areas throughout their life.

Adult Limnetics (with the exception of nesting males) feed in the pelagic zone of the lake, whereas adult Benthics feed in the littoral zone (Schluter 1995). By late summer, individuals begin moving to deeper water habitats where they overwinter (Bentzen et al. 1984). The sex ratio of both Benthics and Limnetics is approximately 1:1 (Bentzen et al. 1984).

Physiological requirements and tolerances have not been described for Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic sticklebacks. As a group, Threespine Sticklebacks occur in a wide array of environments, and they are known to have broad tolerances of many water quality characteristics (e.g., turbidity, water velocity, temperature, depth, pH, alkalinity, calcium and total hardness, salinity, conductivity). Nevertheless, they are generally sensitive to stress from environmental contaminants and are proving to be a useful model in ecotoxicological research e.g., in the development of molecular biomarkers that test the effects of endocrine disrupting chemicals (Scholz and Mayer 2008).

Threespine Stickleback in general can adapt readily to change, including anthropogenic disturbance (Candolin 2009; Hatfield 2009). Non-intuitively, this adaptability may be an underlying vulnerability for sympatric Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs. They have evolved in response to specific selective forces (most likely including interspecific competition between Benthics and Limnetics; see Interspecific Interactions section). Changes in the Little Quarry Lake selective regime could lead not only to adaptive alterations in phenotype that would result in loss of morphological distinctness between Benthics and Limnetics, but also to a breakdown of premating reproductive isolating barriers (National Recovery Team for Stickleback Species Pairs 2007; Ormond et al. 2011). The Enos Lake species pair bears testament to the potential consequences; it has collapsed into a hybrid swarm following altered lake conditions (including the destruction of littoral vegetation and increased turbidity) that accompanied the introduction of the American Signal Crayfish (Kraak et al. 2001; Taylor et al. 2006; Behm et al. 2010).

Threespine Sticklebacks are easily artificially reared, and Benthics and Limnetics would likely survive transplantation (either as artificially reared or wild fish) to lakes that had similar physical and chemical characteristics. Indeed, wild groups of either Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback from other species pairs translocated to experimental ponds remain viable across generations (Schluter pers. comm.). Shifts in body shape from the source population, however, have been observed within a population of Limnetics transplanted from Enos Lake to a pond in Murdo-Frazer Park, North Vancouver, BC (Schluter pers. comm.). A common garden experiment currently underway will likely confirm a genetic component to the differences observed (Schluter pers. comm.).

The species pair does not maintain reproductive isolation when paired together in the experimental ponds. Indeed, the maintenance of their distinct phenotypes and their genetic integrity in a lake environment would most likely depend on similar selective pressures, including interspecific competition and predator-prey interactions, as well as the physical and chemical attributes of the lakes.

Even if Little Quarry Lake fish were transplanted to superficially similar lakes, the success of transplanting can in no way be assured. Our understanding of the specific lake habitat features that are essential to the persistence of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks is incomplete (see Habitat Requirements section). Indeed, we do not fully understand the historical forces that brought about, nor the present day factors that maintain, Benthic-Limnetic species pairs in some lakes rather than others (Ormond et al. 2011).

Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic sticklebacks most likely do not migrate beyond the limits of Little Quarry Lake. Individuals dispersing over the dam into the high gradient outlet would be lost to the population. The number of fish making such movements is, however, likely to be low as the stream is now dammed (Gow pers. obs.); such loss is likely to be of little consequence to general population dynamics. Within the lake there are likely short-distance, seasonal movements associated with spawning, rearing and overwintering, as seen in other Benthic-Limnetic species pair lakes (Bentzen et al. 1984).

A depauperate fish community appears to be a major ecological determinant of where Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs are found; relatively low to absent interspecific competition and predation is likely key to their diversification into species pairs and their persistence (Vamosi 2003; Ormond et al. 2011).

Little Quarry Lake does not seem to harbour any other fish species. Although extensive surveying has not been carried out, extensive minnow trapping (Gow pers. obs.) and three overnight gillnets set over two separate occasions (September 2014, May 2015; Jesson pers. comm., Lunn pers. comm., Wilson pers. comm.) have caught no other fish. There is also no evidence of recreational fishing at Little Quarry Lake (Jesson pers. comm., Lunn pers. comm., Wilson pers. comm.). The only other fish that all other Benthic-Limnetic species pair lakes harbour is Coastal Cutthroat Trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii clarkii; Vamosi 2003; Ormond et al. 2011). The possibility remains that the construction of an outlet dam at Little Quarry Lake over 50 years ago may have blocked a now extinct population of Coastal Cutthroat Trout from accessing spawning habitat. Single ecological types of Threespine Stickleback are found alongside Coastal Cutthroat Trout, as well as Prickly Sculpin (Cottus asper), in at least two other lakes on Nelson Island (Quarry and West lakes; Gow pers. obs.).

The greatest interspecific competitors for Limnetics are likely Benthics, and vice versa: studies have demonstrated competition and character displacement between them (Schluter and McPhail 1992, 1993; Schluter 1994, 1995).

As with other Benthic-Limnetic species pair lakes, Little Quarry Lake is likely inhabited by numerous invertebrates that feed on young sticklebacks, and regularly visited by piscivorous birds (e.g., Heron (Ardea herodias), Kingfisher (Megaceryle alcyon) and Common Loon (Gavia immer)) (COSEWIC 2010a, 2010b). Adult Threespine Stickleback may also prey on stickleback eggs and young (Foster 1994). This predation is not considered a threat to persistence of the species pair.

Submergent macrophytes are considered crucial to maintaining mate recognition and reproductive barriers between Benthics and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks (Hatfield 2009). Their coverage in Little Quarry Lake (0.5 % of lake surface area; Ormond et al. 2011) is nearly half that of another extant Benthic-Limnetic species pair lake (0.9 % for Priest Lake) and an order of magnitude less than that found in another extant Benthic-Limnetic species pair lake (7.6 % for Paxton Lake) (Ormond et al. 2011). The submergent macrophytes in Enos Lake were decimated following the introduction of the American Signal Crayfish (Behm et al. 2010) and now cover only 0.1% of the lake (Ormond et al. 2011). This habitat destruction is thought to have contributed to the breakdown of reproductive barriers between Benthics and Limnetics, and the collapse of the species pair into a hybrid swarm (Taylor et al. 2006; Rosenfeld et al. 2008; Behm et al. 2010; see also Velema et al. 2012).

Although there is no significant difference in the abundance of trophic resources between species pair and comparable non-species pair lakes, the biomass of zooplankton and benthic invertebrates in Little Quarry Lake is significantly lower than that in the other extant Benthic-Limnetic species pair lakes (Ormond et al. 2011).

Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks were described fifteen years after the last discovery of a Benthic-Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pair (McPhail 1993). Three researchers (John Dafoe, Michael Jackson and Jennifer Gow) identified that this previously unsampled lake could potentially harbour a species pair using the physical and ecological conditions hypothesized to be important to their evolution and persistence (Gow et al. 2008). They went on to survey this lake for Threespine Stickleback in June 2007 (Gow et al. 2008). During this search, fish were sampled using dip-netting and minnow traps distributed approximately evenly along the whole shoreline to obtain lake-wide samples. Effort was made to balance the proportions of benthic- and limnetic-looking fish in these collections, but indeterminate forms were not selectively excluded, i.e., fish that appeared to have ambiguous morphology were not discarded.

There have been no direct population estimates of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback. An estimate of abundance can be extrapolated from measurements made from another Benthic-Limnetic species pair. A mark-recapture study estimated abundance in Paxton Lake, indicating approximately 3,300 mature Benthic males and 25,800 mature Limnetic males (Nomura 2005). Confidence in the estimate of Limnetics was, however, considerably lower than that for Benthics (see Table 1 ). Extrapolating from this, between 5,319 and 12,581 Benthics and between 61,212-199,203 Limnetics are estimated to be in Little Quarry Lake (ranges represent 95% confidence intervals; See Table 1 for details). Caution must be observed, however, when considering the accuracy of these estimates. Important differences between Little Quarry Lake and Paxton Lake may result in these being overestimates. Notably, lower abiotic indicators of productivity, and zooplankton and benthic invertebrates biomass, as well as a smaller littoral zone and amount of macrophytes in Little Quarry Lake (Ormond et al. 2011) may contribute to lower levels of abundance of both Benthic and Limnetic Threespine stickleback in Little Quarry Lake.

| Lake | Perimeter (metres) | Mature benthic | Mature limnetic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paxton | 2277 | 6,663 (4,486-10,610) | 91,706 (51,612-167,962) |

| Little Quarry | 2700 | 7,900 (5,319-12,581) | 108,763 (61,212-199,203) |

There has been no quantitative monitoring of Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback abundance in Little Quarry Lake, so population fluctuations and trends are unknown. The lake was last visited in the summer of 2015 where samples of both species were successfully obtained (E. Taylor, pers. comm.).

The global range of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks is entirely within a single lake in Canada, so the concept of rescue effect does not apply to them.

Threespine Stickleback in general can adapt readily to change and are resilient to environmental perturbations (Candolin 2009; Hatfield 2009). Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs, however, are considerably more sensitive to habitat and environmental changes than their solitary freshwater counterparts. Since they have the capacity to interbreed when their premating reproductive isolating barriers are removed, they are vulnerable to changes that disrupt these barriers. As a result, the environmental specificity of the Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs includes features of the environment that prevent hybridization, as well as those features needed to maintain a viable population (National Recovery Team for Stickleback Species Pairs 2007; Hatfield 2009). In summary, their habitat needs probably include:

- Sustained littoral and pelagic productivity to support both species

- Natural light transmissivity to enable mate recognition

- Maintenance of gently sloping sediment (e.g., silt, sand, gravel) beaches and natural littoral macrophytes to provide segregated nesting and juvenile rearing habitats

- Maintenance of a simple ecological community for their persistence in an environment where there is little to no interspecific competition and predation

While the specific limits to Benthic Limnetic species pairs remain poorly understood, it would be prudent to maintain species pair lakes within ranges of current abiotic and biotic variables that are found across their lakes (baseline documented in Ormond et al. 2011), including those that contribute to reproductive isolation.

Little Quarry Lake has a small littoral zone (2.2 %) and little macrophyte coverage (2% of lake surface) compared to other species pair lakes, as well as comparable lakes harbouring solitary Threespine Stickleback populations (Ormond et al. 2011). This suggests that this habitat structure, which is vital to the persistence of species pairs, is likely a limiting factor. In addition, Little Quarry Lake also has the lowest values of any Benthic Limnetic species pair lake for several abiotic parameters (water conductivity, alkalinity, dissolved inorganic carbon and total dissolved solids; Ormond et al. 2011), indicating that productivity may also be a limiting factor for Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback in this lake.

Threats to Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback are similar to those that have been described for the other extant Benthic Limnetic species pairs (COSEWIC 2010a, 2010b). These have been described in the National Recovery Strategy (National Recovery Team for Stickleback Species Pairs 2007) based largely on professional opinion. Due to an absence of information on the effects of different threats on population vital rates (e.g. hybridization rates, growth, survival, reproductive success), quantitative risk assessment has not yet been possible. The threats analysis is, nevertheless, considered robust. The IUCN Threats Calculator returned a threat value of Very High (Appendix, IUCN 2015).

The primary threat to Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetics Threespine Stickleback comes from the introduction of non-native species that could prey upon sticklebacks or disrupt the habitat requirements of the species pair. "Non-native" refers to all species that do not naturally occur within the Little Quarry Lake watershed. The imminence of this threat is uncertain, but the consequences could be disastrous.

The devastating impact of non-native species on Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs has been borne out in the extinction of two pairs in recent decades. Following the introduction of Brown Bullhead (Ameiurus nebulosus), the Hadley Lake species pair swiftly became extinct (Hatfield 2001). The Enos Lake species pair collapsed into a hybrid swarm (Kraak et al. 2001; Taylor et al. 2006). The concurrent appearance of the American Signal Crayfish has been implicated as the main factor driving this collapse (Taylor et al. 2006; Rosenfeld et al. 2008; Behm et al. 2010; Velema et al. 2012). While the Brown Bullhead brought about the demise of the Threespine Stickleback through predation (Hatfield 2001), the American Signal Crayfish is thought to have driven the collapse of the Enos Lake pair through altered environmental conditions; increasing turbidity has disrupted mate recognition cues, and loss of macrophyte beds has diminished segregated nesting and juvenile rearing habitats (Rosenfeld et al. 2008; Behm et al. 2010). Direct predation and changes to male stickleback mating behaviour may also have contributed to the collapse (Velema et al. 2012). This highlights the sensitivity of Benthic Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs to degradation or loss of habitat, the leading threat to freshwater fishes in Canada (Dextrase and Mandrak 2006; Taylor 2004).

Currently, there is no evidence of recreational fishing at Little Quarry Lake (Jesson pers. comm., Lunn pers. comm., Wilson pers. comm.). Recreational fishing for introduced (in 1985) and now self-sustaining populations of Coastal Cutthroat Trout, however, does occur in Quarry Lake which is located only 400 m to the northwest of Little Quarry Lake (S. Northrup, pers. comm. 2015; S. Rudman pers. comm. 2015). Further, the threat of introductions of other non-native fish species for angling purposes is likely high, considering the number of invasive species that are in nearby lakes on the mainland, Vancouver Island, and other islands in the Strait of Georgia, and continuing to spread throughout the region. For example, Largemouth and Smallmouth basses (Micropterus salmoides and M. dolomieu), Pumpkinseed Sunfish (Lepomis gibbosus), and Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens) have been spread by anglers and other members of the public (Hatfield and Pollard 2006). Bradford et al. (2008a,b) conducted qualitative risk assessments and concluded that for most regions of BC, the probability of invasive fish species becoming established after release is high or very high, and the likely magnitude of ecological impact in small water bodies is very high. The introduction of predatory fish would likely pose the greatest threat to Little Quarry Lake Benthics, given its lack of a pelvic girdle; a feature considered important to post-capture defence against fish predators (Lescak and von Hippel 2011).

Other threats from invasive species include the spread of amphibians like the Bullfrog (Rana catesbeiana) and invasive aquatic vegetation such as Eurasian Milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum) and Purple Loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria).

Little Quarry Lake is relatively remote and inaccessible compared to other lakes with species pairs, which offers some protection from the threat of non-native species introductions. Remoteness, however, did not prevent the introduction of the exotic Brown Bullhead in Hadley Lake (Hatfield 2001).

As with the other Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pair lakes (National Recovery Team for Stickleback Species Pairs 2007), Little Quarry Lake outlet is blocked by a dam. In this case, an earthen dam was likely built over 50 years ago for log flume purpose. It is believed to have raised the water level in the lake by about 1.5 m (Bristol pers. comm.). Unpredictable failure of this earthen dam could cause flooding downstream, as well as a drop in the lake water level (Bristol pers. comm.).

Little Quarry Lake serves as a domestic water supply to a strata development of recreational lots (Strata VRSP 1481) around the oceanside of Quarry Bay (Bristol pers. comm.). There are no residences around Little Quarry Lake itself. A pipe intake situated close to the dam has distributed water to this strata since the 1980s (water licence C59404; Bristol pers. comm.). The dam is not included in the water licence but the residential water outtake may depend on the raised lake level that the dam provides (Bristol pers. comm.). The historical use of water and its impact on Threespine Stickleback habitat is not known, although large fluctuations in water levels should be avoided.

There appears to have been limited land-based development activity within the Little Quarry Lake watershed. Forest harvesting has occurred historically, but A&A Trading Ltd. have not harvested here within the last five years (Marquis pers. comm.). Any prior logging within the watershed has been extremely limited, and well removed from the lake or its inlet (Anonymous reviewer pers. comm.). There are future plans to harvest within this watershed but not within the next five years (Marquis pers. comm.). This will occur within a very limited area within the watershed, distant from the lake or inlet (Anonymous reviewer pers. comm.). There is a very small section of A & A Trading Ltd. timbered land that borders the lake but this consists of non-harvestable trees and it is extremely unlikely that this would ever be harvested. No other private lands or tenures exist within the lake borders. The main concern from future forestry-related activities is likely the introduction of suspended sediments (i.e., increased turbidity), which could disrupt mate recognition, and potentially lead to a breakdown in premating reproductive isolation barriers (Behm et al. 2010). Based on coastal hydrology and seasonal precipitation patterns, however, the possibility of introducing suspended sediments into the lake by any means during the Threespine Stickleback spawning season (March to May) appears negligible (Anonymous reviewer pers. comm.). Thus, there appears to be little threat from land-based activities.

Because of their scientific importance, a demand may arise for Benthic and Limnetic species pair wild stock for laboratory-based studies, and for permits to conduct in situ scientific studies (Recovery Team for Non-Game Freshwater Fish Species in BC 2013). Indeed, collecting activities have likely been a leading source of mortality of adult fish in other Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pairs (Recovery Team for Non-Game Freshwater Fish Species in BC 2013). Collecting guidelines now recommend limits for lethal and non-lethal sampling of the Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pair, and restrict all sampling (lethal or capture-and-release) to half of the lake (Recovery Team for Non-Game Freshwater Fish Species in BC 2013). Please refer to Protection, Status and Ranks section for details.

The probable extent of any of these threats is the entire lake given its small size. Consequently, there is a single location for the Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback.

The Canadian federal Fisheries Act (Section 35)does not provide habitat protection provisions for Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks. Under changes that came into force in 2013, Section 35 of the Act only applies to fishes that are the focus of commercial, recreational, or Aboriginal fisheries. This does not include Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks.

The Fisheries Act delegates authority to the provinces and territories to establish and enforce fishing regulations. In accordance with this Act, the BC Sport Fishing Regulations stipulate that it is illegal to fish for, or catch and retain the other extant Benthic and Limnetic species pairs but Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks are not currently managed under the BC Sport Fishing regulations (Department of Justice Canada 1996).

Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks are also afforded some protection in British Columbia under the provincial Wildlife Act, whichenables authorities to license anglers and angling guides, and to regulate scientific fish collection permits.

Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks have not been assigned a Global Heritage Status rank, nor has the general status of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks been assessed at the national or provincial level (NatureServe 2014, Wild Species 2014; British Columbia Conservation Data Centre 2014).

The other extant Benthic and Limnetics Threespine Sticklebacks species pairs are listed as Critically Imperiled (G1, NatureServe 2014), meaning that they are considered to be at very high risk of extinction across their entire range. They are also listed as Critically Imperiled nationally in Canada (N1) and subnationally in British Columbia (S1; NatureServe 2014). They are "red-listed" by the Conservation Data Centre and BC Ministry of Environment (BCCDC 2014).

The former Recovery Team for Non-Game Freshwater Fish Species in BC developed collecting guidelines that restrict all sampling (lethal or capture and release) of the Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pair to half of the lake (Recovery Team for Non-Game Freshwater Fish Species in BC 2013). They also recommend limiting lethal and non-lethal sampling, such that scientific collections should constitute less than 10% of the mature fish population (20% for juvenile fish), as measured in spring and summer seasons. It was also recommended that a 5% mortality rate for "non-lethal" sampling should be factored into overall permitting levels.

Other recommendations cover sampling methods and in situ scientific studies and include: prevention of the spread of invasive species and disease organisms, by sterilizing sampling equipment (traps, seines, boats, boots, etc.); prohibition on the use of non-wild, native hybrids in experimental in situ studies; and prohibitions on translocation of Threespine Stickleback, or any plant or animal that does not occur naturally in the lake, to Little Quarry Lake (Recovery Team for Non-Game Freshwater Fish Species in BC 2013).

There are no habitat protection provisions specifically for the aquatic habitat of Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks. Almost all lands surrounding Little Quarry Lake are Crown Land (LT&SABC) so they are afforded some protection from the BC Forest and Range Practices Act, which has provisions to protect fish habitat from forestry activities. The provincial Riparian Areas Regulation also provides some protection for the riparian area around the lake.

The report writer would like to extend her gratitude to all of the following people for generously sharing information and advice (see also Table 2): Eric Taylor and Dolph Schluter (University of British Columbia); Sean Rogers (University of Calgary); David Marquis (A & A Trading Ltd.); Jordan Rosenfeld and Gregory Wilson (BC Ministry of Environment); Mike Bristol, Duane Jesson and Iain Lunn (BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations); Christie Whelan, Sean MacConnachie (Department of Fisheries and Oceans); Patrick Nantel (Parks Canada); Katrina Stipec (British Columbia Conservation Data Centre); and Robert Anderson, Claude Renaud and Sylvie Laframboise (Canadian Museum of Nature). The report writer would also like to thank Jenny Wu (COSEWIC Secretariat) for her collegiality in creating the distribution map and calculating extent of occurrence and area of occupancy. Neil Jones (COSEWIC) informed the author that the status of ATK information for Little Quarry Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Sticklebacks is not available at the time of submission of this report. Thanks are also extended to the COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Specialists Subcommittee, particularly the co-chair Eric Taylor, and reviewers for valuable input during the review process.

| Name | Title | Affiliation | City, Province/ State (Country) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sonia Schnobb | Administrative Assistant | COSEWIC Secretariat | Ottawa, ON |

| Jenny Wu | Scientific Project Officer | COSEWIC Secretariat | Gatineau QC |

| Neil Jones | Scientific Project Officer & ATK Coordinator | COSEWIC Secretariat | Gatineau QC |

| Rhonda L. Millikin | A/Head Population Assessment | Canadian Wildlife Service (Pacific & Yukon Region) |

Delta, BC |

| Shelagh Bucknell | Administrative Services Assistant | Canadian Wildlife Service (Pacific & Yukon Region) |

Delta, BC |

| Robert Anderson | Research Scientist, Life Sciences (Entomology) | Canadian Museum of Nature | Ottawa, ON |

| Jennifer Doubt | Chief Collection Manager - Botany | Canadian Museum of Nature | Ottawa, ON |

| Claude Renaud | Research Scientist, Life Sciences (Ichthyology) | Canadian Museum of Nature | Ottawa, ON |

| Sylvie Laframboise | Assistant Collections Manager, Vertebrate Section | Canadian Museum of Nature | Ottawa, ON |

| Christie-Whelan | Science Advisor | Department of Fisheries and Oceans | Ottawa, ON |

| Simon-Nadeau | Senior Advisor | Department of Fisheries and Oceans | Ottawa, ON |

| Sean MacConnachie | Species at Risk Biologist | Department of Fisheries and Oceans | Nanaimo, BC |

| Patrick-Nantel | Conservation Biologist | Parks Canada | Gatineau, QC |

| Tamaini Snaith | Special Advisor | Parks Canada | Gatineau, QC |

| Gregory Wilson | Aquatic Species at Risk Specialist | BC Ministry of Environment | Victoria, BC |

| Duane Jesson | Senior Fish Biologist | BC Ministry of Forest, Lands and Natural Resource Operations | Vancouver, BC |

| Iann Lunn | Fish Biologist | BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations | South Coast Region, BC |

| Mike Bristol | Regional Dam Safety Officer | BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations | South Coast Region, BC |

| Katrina Stipec | - | British Columbia Conservation Data Centre | Victoria, BC |

| Jordan Rosenfeld | Research Scientist | BC Ministry of Environment | Vancouver, BC |

| Eric Taylor | Professor/ Co-chair Freshwater Fishes Specialists Subcommittee | University of British Columbia/ COSEWIC | Vancouver, BC |

| Dolph Schluter | Professor | University of British Columbia | Vancouver, BC |

| Sean Rogers | Assistant Professor | University of Calgary | Calgary, AB |

| David Marquis | Registered Professional Forester | A & A Trading Ltd. | Vancouver, BC |

Anonymous reviewer. 2015. COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Manuscript Review correspondence to J. Gow. June 2015.

Behm, J., A.R. Ives, and J.W. Boughman. 2010. Breakdown in postmating isolation and the collapse of a species pair through hybridization. The American Naturalist 175:11-26.

Bell, M.A. 1987. Interacting evolutionary constraints in pelvic reduction of threespine sticklebacks, Gasterosteus aculeatus (Pisces, Gasterosteidae). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 31:347-382.

Bell, M.A., G. Ortí, J.A. Walker, and J.P. Koenings. 1993. Evolution of pelvic reduction in threespine stickleback fish: a test of competing hypotheses. Evolution 47:906-914.

Bell, M.A., and S.A. Foster (eds.). 1994. The Evolutionary Biology of the Threespine Stickleback. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Bentzen, P., M.S. Ridgway, and J.D. McPhail. 1984. Ecology and evolution of sympatric sticklebacks (Gasterosteus): spatial segregation and seasonal habitat shifts in the Enos lake species pair. Canadian Journal of Zoology 62:2435-2439.

Berner, D., A-C. Grandchamp, and A.P. Hendry. 2009. Variable progress toward ecological speciation in parapatry: stickleback across eight lake-stream transitions. Evolution 63:1740-1753.

Boughman, J.W. 2001. Divergent sexual selection enhances reproductive isolation in sticklebacks. Nature 411:944-947.

Bradford, M.J., C.P. Tovey, and L.M. Herborg. 2008a. Biological risk assessment for Yellow perch (Perca flavescens) in British Columbia - PDF. Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2008/073. [accessed 26 July 2014].

Bradford, M.J., C.P. Tovey, and L.M. Herborg. 2008b. Biological risk assessment for Northern pike (Esox lucius), Pumpkinseed (Lepomis gibbosus), and Walleye (Sander vitreus) in British Columbia - PDF. Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS) Research Document 2008/074. [accessed 26 July 2014].

Bristol, M., pers. comm. 2015. Email correspondence to J. Gow. March 2015. Regional Dam Safety Officer, BC Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, South Coast Region, British Columbia.

British Columbia Conservation Data Centre. 2014. British Columbia Species and Ecosystems Explorer [accessed 26 July 2014].

Candolin, U. 2009. Population responses to anthropogenic disturbance: lessons from three-spined sticklebacks Gasterosteus aculeatus in eutrophic habitats. Journal of Fish Biology 75:2108-2121.

COSEWIC. 2010a. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Paxton Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pair (Gasterosteus aculeatus) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa.

COSEWIC. 2010b. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Vananda Creek Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pair (Gasterosteus aculeatus) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa.

COSEWIC. 2011. Status Reports: Guidelines for Recognizing Designatable Units, Government of Canada. [accessed 26 July 2014].

COSEWIC. 2012. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Enos Lake Benthic and Limnetic Threespine Stickleback species pair (Gasterosteus aculeatus) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa.

Department of Justice Canada. 1996. British Columbia Sport Fishing Regulations, 1996 (SOR/96-137). Web site: http://laws.justice.gc.ca/en/SOR-96-137/FullText.html [accessed 10 August 2014].

Dextrase, A. and N.E. Mandrak. 2006. Impacts of alien invasive species on freshwater fauna at risk in Canada. Biological Invasions 8: 13-24.

Foster, S.A. 1994. Evolution of the reproductive behaviour of threespine stickleback. Pp. 381-398. in M.A. Bell and S.A. Foster (eds). The Evolutionary Biology of the Threespine Stickleback. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Giles, N. 1983. The possible role of environmental calcium levels during the evolution of phenotypic diversity in Outer Hebridean populations of the three-spined stickleback, Gasterosteus aculeatus. Joumal of Zoology 199:535-544.

Gow, J.L., C.L. Peichel, and E.B. Taylor. 2006. Contrasting hybridization rates between sympatric three-spined sticklebacks highlight the fragility of reproductive barriers between evolutionarily young species. Molecular Ecology 15:739-752.

Gow, J. L., C.L. Peichel, and E.B Taylor 2007. Ecological selection against hybrids in natural populations of sympatric threespine sticklebacks. Journal of Evolutionary Biology 20: 2173-2180.

Gow, J.L., S.M. Rogers, M. Jackson, and D. Schluter. 2008. Ecological predictions lead to the discovery of a benthic-limnetic sympatric species pair of threespine stickleback in Little Quarry Lake, British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Zoology 86:564-571.

Hatfield, T. 2001. Status of the stickleback species pair, Gasterosteus spp., in Hadley Lake, Lasqueti Island, British Columbia. Canadian Field-Naturalist 115:579-583.

Hatfield, T. 2009. Identification of critical habitat for sympatric Stickleback species pairs and the Misty Lake parapatric stickleback species pair. DFO Can. Sci. Advis. Sec. Res. Doc. 2009/056.

Hatfield, T., and S. Pollard. 2006. Non-native freshwater fish species in British Columbia. Biology, biotic effects, and potential management actions. Report prepared for Freshwater Fisheries Society of British Columbia, Victoria BC. [accessed 10 August 2014].

Hatfield, T. and D. Schluter. 1996. A test for sexual selection on hybrids of two sympatric sticklebacks. Evolution 50:2429-2434.

Hubbs, C. L. 1955. Hybridization between fish species in nature. Systematic Zoology, 4: 1-20.

Hutchinson, I., T. James, J. Clague, J.V. Barrie, and K. Conway. 2004. Reconstruction of late Quaternary sea-level change in southwestern British Columbia from sediments in isolation basins. Boreas 33:183-194.

IUCN 2015. Threats classification scheme (version 3.2). International Union for the Conservation of Nature.

Jesson, D., pers. comm. 2015. COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Manuscript Review correspondence to J. Gow. January and June 2015. Senior Fish Biologist, BC Ministry of Forest, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, Vancouver, British Columbia.