Louisiana waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla): COSEWIC assessment and status report 2015

Threatened

2015

Table of Contents

- Document Information

- Assessment Summary

- Executive Summary

- Technical Summary

- Preface

- Wildlife Species Description and Significance

- Distribution

- Habitat

- Biology

- Population Sizes and Trends

- Threats and Limiting Factors

- Protection, Status and Ranks

- Acknowledgements and Authorities Contacted

- Information Sources

- Biographical Summary of Report Writer(s)

- Collections Examined

List of Figures

- Figure 1. Adult Louisiana Waterthrush at nest with young (photo by Michael Patrikeev with permission)

- Figure 2. Global range of the Louisiana Waterthrush (map from Environment Canada 2012, based on Ridgely et al. 2007)

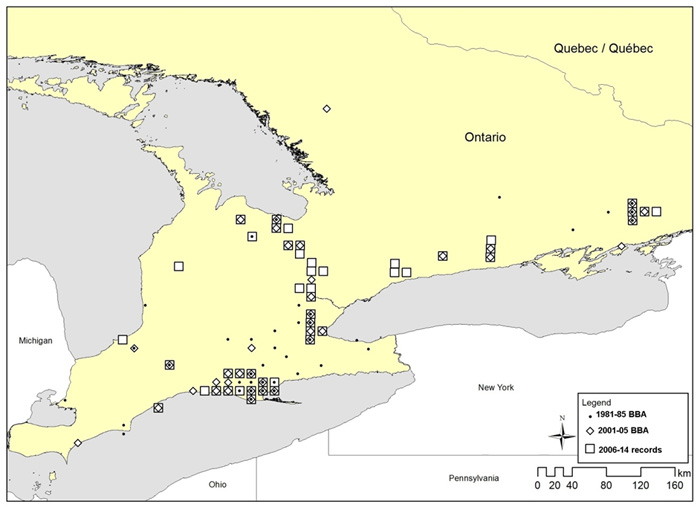

- Figure 3. Breeding distribution of the Louisiana Waterthrush in Ontario in three time periods: 1981-1985 (Cadman et al. 1987), 2001-2005 (Cadman et al. 2007) and 2006-2014 (compiled records)

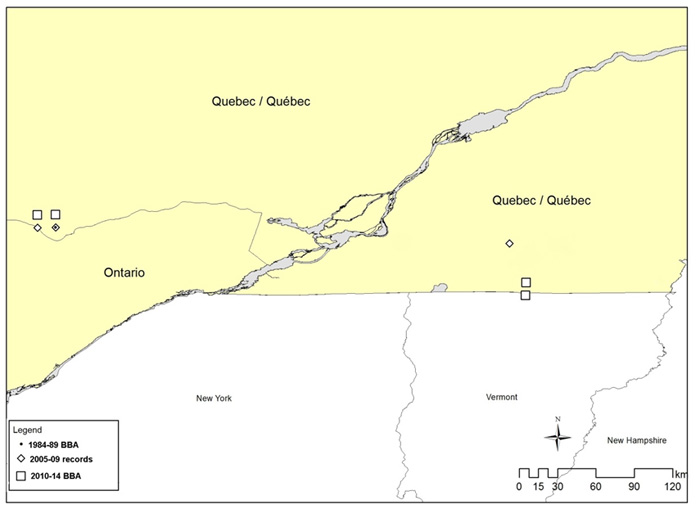

- Figure 4. Breeding distribution of the Louisiana Waterthrush in Quebec in three time periods: 1984-1989 (Gauthier and Aubry 1996), 2005-2009 (compiled records; see Table 1 for details) and 2010-2014 (Québec Breeding Bird Atlas 2014).

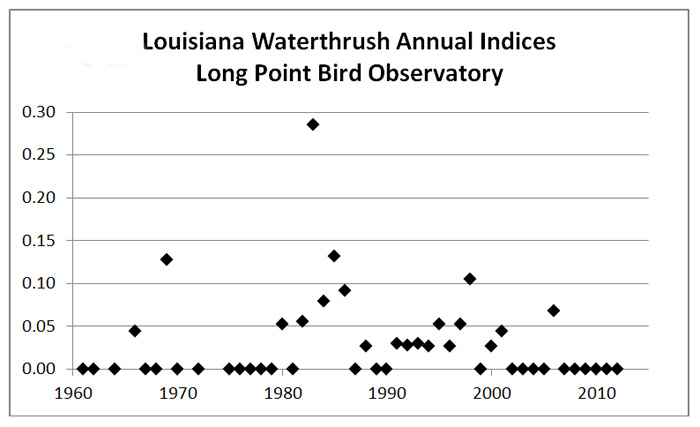

- Figure 5. Annual indices of spring migration counts of Louisiana Waterthrushes at Long Point Bird Observatory, 1961-2012 (courtesy Bird Studies Canada).

List of Tables

- Table 1. Survey effort, survey results and other sources of information on the recent distribution and abundance of the Louisiana Waterthrush in Canada, 2005-2014.

- Table 2. Estimated size of Louisiana Waterthrush breeding population in various regions of Ontario and Quebec

- Table 3. NatureServe ranks, official status designations, and population estimates for Louisiana Waterthrush in Canadian provinces and in U.S. states adjacent to the Canadian range

List of Appendices

Document Information

COSEWIC

Committee on the Status

of Endangered Wildlife

in Canada

COSEPAC

Comité sur la situation

des espèces en péril

au Cananda

COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows:

COSEWIC. 2015. COSEWIC assessment and status report on theLouisiana Waterthrush Parkesia motacilla in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. x + 41 pp. (Species at Risk Public Registry website).

Previous report(s):

COSEWIC. 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Louisiana Waterthrush Parkesia motacilla in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 26 pp.

Page, A.M. 1996. Update COSEWIC status report on the Louisiana Waterthrush Parkesia motacilla in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 1-24 pp.

McCracken, J.D. 1991. COSEWIC status report on the Louisiana Waterthrush Parkesia motacilla in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. 1-26 pp.

Production note:

COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Audrey Heagy (Bird Studies Canada) for writing the status report on Louisiana Waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Jon McCracken, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Birds Specialist Subcommittee.

For additional copies contact:

COSEWIC Secretariat

c/o Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment and Climate Change Canada

Ottawa, ON

K1A 0H3Tel.: 819-938-4125

Fax: 819-938-3984

COSEWIC E-mail

COSEWIC website

Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur L'hémileucin de Nuttall (Hemileuca nuttalli) au Canada.

Cover illustration/photo:

Louisiana Waterthrush -- Photo by © Michael Patrikeev.

COSEWIC Assessment Summary

Assessment Summary – November 2015

- Common name

- Louisiana Waterthrush

- Scientific name

- Parkesia motacilla

- Status

- Threatened

- Reason for designation

- During the breeding season in Canada, this songbird nests along clear, shaded, coldwater streams and forested wetlands in southern Ontario and southwestern Quebec. It occupies a similar habitat niche in Latin America during the winter. The Canadian population is small, probably consisting of fewer than 500 adults, but breeding pairs are difficult to detect. Population trends for the Canadian population are uncertain. Declines have been noted in some parts of the Canadian range, particularly in its stronghold in southwestern Ontario, while new pairs have been found in others. Immigration of individuals from the northeastern U.S. is thought to be important to maintaining the Canadian population. However, while the U.S. source population currently appears to be fairly stable, it may be subject to future population declines due to emerging threats to habitat.

- Occurrence

- Ontario, Quebec

- Status history

- Designated Special Concern in April 1991. Status re-examined and confirmed in April 1996 and April 2006. Status re-examined and designated Threatened in November 2015.

COSEWIC Executive Summary

Louisiana Waterthrush - Parkesia motacilla

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

The Louisiana Waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) is a relatively large, drab wood-warbler that resembles a small thrush. Males and females are identical in appearance. The upper parts are dull brown. The lower parts are cream-coloured, with dark streaking on the breast and flanks. A bold, broad, white streak over the eye extends to the nape. The legs are bubble-gum pink, and the bill is rather long and heavy for a warbler.

Distribution

Most of the global breeding range (>99%) is within the eastern United States. In Canada, the Louisiana Waterthrush breeds in southern Ontario, where it is considered a rare, but regular local summer resident. It is also a rare, but sporadic breeder in southwestern Quebec. The bulk of the Canadian population is concentrated in two areas of Ontario: the Norfolk Sand Plain region bordering the north shore of Lake Erie, and the central Niagara Escarpment between Hamilton and Owen Sound.

Its wintering range extends from northern Mexico through Central America to extreme northwestern South America, and also throughout the West Indies.

Habitat

The Louisiana Waterthrush occupies specialized habitat, showing a strong preference for nesting and wintering along relatively pristine headwater streams and wetlands situated in large tracts of mature forest. Although it prefers running water (especially clear, coldwater streams), it also inhabits heavily wooded swamps with vernal or semi-permanent pools, where its territories can overlap with its sister species the Northern Waterthrush. It is often classified as both an area-sensitive forest species, and a riparian-obligate species. Louisiana Waterthrush nests are constructed within niches in steep stream banks, in the roots of uprooted trees, or in mossy logs and stumps, usually within a few metres of water.

Biology

The Louisiana Waterthrush is a long-distance migrant that typically arrives in southern Ontario much earlier in the spring than other neotropical songbirds. It displays annual fidelity to both breeding and wintering sites. Louisiana Waterthrush clutch size ranges from 4-6 eggs and incubation extends from 12-14 days. The species is generally single-brooded.

The Louisiana Waterthrush spends most of its time on or near the ground, along the margins of streams and pools. It has a specialized diet, feeding mostly on aquatic macro-invertebrates, especially insects, and sometimes eats small molluscs, fish, crustaceans, and amphibians.

Population Size and Trends

The Canadian population is estimated to be 235 to 575 adults. Population trends are poorly understood. The species has declined locally in parts of Canada in the past century and in the past few decades (related to habitat degradation and/or population fluctuations), but targeted surveys have found higher numbers in some parts of the Canadian range in recent years. Overall, populations in Canada and much of the U.S. currently appear to be relatively stable.

Threats and Limiting Factors

The Louisiana Waterthrush is a habitat specialist and its global population is limited by the supply of high-quality aquatic habitat on both its breeding and wintering grounds. There is no single imminent threat to the survival of the Canadian population; rather, it is the cumulative effects of many threats at different stages of its annual life cycle that are of particular concern. Habitat loss and changes in water quality/quantity due to agricultural intensification, and suburban residential development may have contributed to declines observed in parts of southern Ontario. Habitat conditions in Canada are expected to deteriorate due to the anticipated spread of Hemlock Woolly Adelgid, an exotic forest pest, into eastern Canada. Habitat fragmentation and degradation on its U.S. breeding grounds due to the combination of exotic forest pests and resource development could reduce immigration into the Canadian population. Habitat loss and degradation, including degraded water quality and deforestation due to agricultural and development activities, are ongoing threats in the wintering range. During migration, this species also experiences relatively high rates of mortality due to collisions with tall buildings and communication towers.

Protection, Status, and Ranks

The Migratory Birds Convention Act currently provides the most specific legislation protecting the Louisiana Waterthrush in Canada. A high proportion of known nesting sites are in protected areas. The specific habitats used by this species in Ontario are also provided some protection through various legislative policies. In addition, their physical characteristics generally preclude most kinds of agricultural and development activities.

Technical Summary

- Scientific Name:

- Parkesia motacilla

- English Name:

- Louisiana Waterthrush

- French Name:

- Paruline hochequeue

- Range of occurrence in Canada (province/territory/ocean): :

- Ontario, Quebec

Demographic Information

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Generation time (usually average age of parents in the population; indicate if another method of estimating generation time indicated in the IUCN guidelines is being used) | 2 to 3 yrs |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] continuing decline in number of mature individuals? The outcome from the threats calculator suggests that a future decline could be projected. |

Unknown |

| Estimated percent of continuing decline in total number of mature individuals within [5 years or 2 generations] | N/A |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the last 10 years. | Unknown, but overall population estimates have generally been stable |

| [Projected or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the next 10 years. | Unknown |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over any 10 year period, over a time period including both the past and the future. | Unknown |

| Are the causes of the decline a. clearly reversible and b. understood and c. ceased? | N/A |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals? | No |

Extent and Occupancy Information

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Estimated extent of occurrence | 110,000 km2 |

| Index of area of occupancy (IAO) (Always report 2x2 grid value). | Estimated <500 km2(known 368 km2) |

| Is the population "severely fragmented" ie. is >50% of its total area of occupancy in habitat patches that are (a) smaller than would be required to support a viable population, and (b) separated from other habitat patches by a distance larger than the species can be expected to disperse? | No |

| Number of locations (use plausible range to reflect uncertainty if appropriate) (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.) |

Unknown, but more than the threshold of 10 locations |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in index of area of occupancy? | No |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of subpopulations? | N/A |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of "locations"? (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.) |

Unknown |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in [area, extent and/or quality] of habitat? | Yes, inferred and projected decline in habitat quality owing to loss of hemlock and effects of stream acidification. |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of subpopulations? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of "locations"? (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.) |

No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in index of area of occupancy? | No |

Number of Mature Individuals (in each subpopulation)

| Population | N Clones (index of Mature Individuals) |

|---|---|

| Subpopulations/Regions: Based on estimated number of territories extrapolated from numbers of males detected during targeted surveys and assuming 75% of males are paired | N Mature Individuals |

| Southwestern Ontario | Estimated 116 to 254 adults (66 to 145 males and 50 to 109 females) |

| South-central Ontario | Estimated 93 to 234 adults (53 to 134 males and 40 to 100 females) |

| Southeastern Ontario (including Southern Shield region) | Estimated 26 to 70 adults (15 to 40 males and 11 to 30 females) |

| Southwestern Quebec | Estimated 0 to 17 adults (0 to 10 males and 0 to 7 females) |

| Total | Estimated 235 to 575 adults (134 to 329 males and 101 to 246 females) |

Quantitative Analysis

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Probability of extinction in the wild is at least [20% within 20 years or 5 generations, or 10% within 100 years]. | No recent quantitative analysis is available. A very preliminary population modelling analysis in 2001 suggested that the Canadian population should persist for over 100 years (see Fluctuations and Trends section). |

Threats (actual or imminent, to populations or habitats, from highest impact to least)

Ongoing declines in water quality/quantity due to agricultural intensification, rural and suburban residential developments, and increased variability and severe weather due to climate change.

Habitat fragmentation and degradation on breeding grounds due to combination of new exotic forest pests (hemlock mortality due to Hemlock Woolly Adelgid ongoing or imminent on U.S. range, and emerging threat on Canadian range) and new resource developments (shale gas extraction, ridge-top wind turbine installations, mountaintop-removal coal mining ongoing or imminent in northern U.S. range). Habitat loss and degradation on the wintering grounds, including degraded water quality and deforestation.

Collisions with buildings and towers during migration.

Disturbance to nesting birds due to recreational activities (ATVs fording streams, trampling of streambanks by fishers and hikers, etc.)

- Was a threats calculator completed for this species and if so, by whom?

- Yes

- Dwayne Lepitzki, Jon McCracken, Audrey Heagy, Julie Perrault, Marcel Gahbauer, Lyle Friesen, Don Sutherland, François Shaffer, Ben Walters, Zoe Lebrun-Southcott, Brady Mattsson.

Rescue Effect (immigration from outside Canada)

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status of outside population(s) most likely to provide immigrants to Canada. See Population and Trends section. |

Populations in adjacent U.S. states have mostly been stable or increasing (Ohio, Pennsylvania, Vermont, New Hampshire), but recent declines in New York and Michigan. |

| Is immigration known or possible? | Yes |

| Would immigrants be adapted to survive in Canada? | Yes |

| Is there sufficient habitat for immigrants in Canada? | Yes |

| Are conditions deteriorating in Canada? See Table 3 (Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Uncertain, but probably |

| Are conditions for the source population deteriorating See Table 3 (Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Habitat conditions are currently deteriorating or are expected to deteriorate in large parts of the US range. |

| Is the Canadian population considered to be a sink? See Table 3 (Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

No |

| Is rescue from outside populations likely? | Yes (at least in the short term). |

Data-Sensitive Species

| Summary Items | Information |

|---|---|

| Is this a data sensitive species? | No |

Status History

COSEWIC: Designated Special Concern in April 1991. Status re-examined and confirmed in April 1996 and in April 2006. Status re-examined and designated Threatened in November 2015.

Status and Reasons for Designation:

- Status:

- Threatened

- Alpha-numeric code:

- Alpha-numeric codes: D1

- Reasons for designation:

- During the breeding season in Canada, this songbird nests along clear, shaded, coldwater streams and forested wetlands in southern Ontario and southwestern Quebec. It occupies a similar habitat niche in Latin America during the winter. The Canadian population is small, probably consisting of fewer than 500 adults, but breeding pairs are difficult to detect. Population trends for the Canadian population are uncertain. Declines have been noted in some parts of the Canadian range, particularly in its stronghold in southwestern Ontario, while new pairs have been found in others. Immigration of individuals from the northeastern U.S. is thought to be important to maintaining the Canadian population. However, while the U.S. source population currently appears to be fairly stable, it may be subject to future population declines due to emerging threats to habitat.

Applicability of Criteria

- Criterion A (Decline in Total Number of Mature Individuals):

- Not applicable. Rates of decline cannot be specified.

- Criterion B (Small Distribution Range and Decline or Fluctuation):

- Does not meet criteria. Potentially meets Endangered because IAO is < 500 km² and there is a continuing decline in habitat quality. However, the population is not severely fragmented, there are > 10 locations, and there are no extreme fluctuations.

- Criterion C (Small and Declining Number of Mature Individuals):

- Does not meet criteria. Could meet Threatened C2a(i) because there are < 1000 individuals, but there is insufficient evidence for a continuing population decline.

- Criterion D (Very Small or Restricted Population):

- Meets Threatened D1, because there are < 1000 mature individuals.

- Criterion E(Quantitative Analysis):

- Not applicable. Not done.

Preface

Since this species was last assessed by COSEWIC in 2006, new information on the distribution and abundance is available as a result of targeted surveys in southwestern Quebec and southern Ontario, as well as the completion of 5 years of fieldwork for the second Québec Breeding Bird Atlas. In addition, information on nesting productivity and parasitism rates in Canada is available as a result of nest monitoring efforts in southwestern Ontario. Some information on site fidelity, site turnover, and return rates in Ontario is also available as a result of a 4-year colour-banding project.

New and emerging threats on the breeding grounds are impacting breeding habitat in the northern United States range, which is considered an essential source of immigrants to sustain the small Canadian population. New forest pest species are also expected to affect forest habitat in the Canadian breeding range in the near future. Other threats to the population in southern Ontario are continuing.

COSEWIC History

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) was created in 1977 as a result of a recommendation at the Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference held in 1976. It arose from the need for a single, official, scientifically sound, national listing of wildlife species at risk. In 1978, COSEWIC designated its first species and produced its first list of Canadian species at risk. Species designated at meetings of the full committee are added to the list. On June 5, 2003, the Species at Risk Act (SARA) was proclaimed. SARA establishes COSEWIC as an advisory body ensuring that species will continue to be assessed under a rigorous and independent scientific process.

COSEWIC Mandate

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assesses the national status of wild species, subspecies, varieties, or other designatable units that are considered to be at risk in Canada. Designations are made on native species for the following taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, arthropods, molluscs, vascular plants, mosses, and lichens.

COSEWIC Membership

COSEWIC comprises members from each provincial and territorial government wildlife agency, four federal entities (Canadian Wildlife Service, Parks Canada Agency, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the Federal Biodiversity Information Partnership, chaired by the Canadian Museum of Nature), three non-government science members and the co-chairs of the species specialist subcommittees and the Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge subcommittee. The Committee meets to consider status reports on candidate species.

Definitions (2015)

- Wildlife Species

- A species, subspecies, variety, or geographically or genetically distinct population of animal, plant or other organism, other than a bacterium or virus, that is wild by nature and is either native to Canada or has extended its range into Canada without human intervention and has been present in Canada for at least 50 years.

- Extinct (X)

- A wildlife species that no longer exists.

- Extirpated (XT)

- A wildlife species no longer existing in the wild in Canada, but occurring elsewhere.

- Endangered (E)

- A wildlife species facing imminent extirpation or extinction.

- Threatened (T)

- A wildlife species likely to become endangered if limiting factors are not reversed.

-

Special Concern (SC)

(Note: Formerly described as "Vulnerable" from 1990 to 1999, or "Rare" prior to 1990.) - A wildlife species that may become a threatened or an endangered species because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

-

Not at Risk (NAR)

(Note: Formerly described as "Not In Any Category", or "No Designation Required.") - A wildlife species that has been evaluated and found to be not at risk of extinction given the current circumstances.

-

Data Deficient (DD)

(Note: Formerly described as "Indeterminate" from 1994 to 1999 or "ISIBD" [insufficient scientific information on which to base a designation] prior to 1994. Definition of the [DD] category revised in 2006.) - A category that applies when the available information is insufficient (a) to resolve a species' eligibility for assessment or (b) to permit an assessment of the species' risk of extinction.

The Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, provides full administrative and financial support to the COSEWIC Secretariat.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Name and Classification

- Scientific Name:

- Parkesia motacilla (formerly Seiurus motacilla)

- English Name:

- Louisiana Waterthrush

- French Name;

- Paruline hochequeue

No subspecies have been recognized or described (American Ornithologist’s Union [AOU] 2013). This member of the New World wood-warbler (Parulidae) family was formerly classified in the genus Seiurus, along with Northern Waterthrush (now Parkesia noveboracensis) and Ovenbird (S. aurocapilla). Both waterthrush species were recently transferred to the new genus Parkesia based on genetic data indicating that the two waterthrushes are sister species (Sangster 2008; Chesser et al. 2010).

Morphological Description

The Louisiana Waterthrush is a relatively large, drab warbler that resembles a small thrush (Figure 1). Males and females are identical in appearance. The upper parts are dull brown. The lower parts are cream-coloured, with dark streaking on the breast and flanks, which fades out in the undertail coverts. A bold, broad, white supercilium (eye brow) extends to the nape. The legs are bubble-gum pink, and the bill is rather long and heavy for a warbler (Curson et al. 1994; Dunn and Garrett 1997).

The species is easily confused with the Northern Waterthrush (Parkesia noveboracensis), which is much more common and widespread in Canada. The most notable plumage difference between the two species is that the Northern Waterthrush’s supercilium (eye-brow) is cream-coloured or yellowish, relatively thin, and tapers behind the eye, whereas it is white and more extensive in the Lousiana Waterthrush. The Northern Waterthrush also has brown blotches on its undertail coverts, which are less distinct in the Louisiana Waterthrush. The two species are best separated in the field by song, and also by behaviour and habitat differences. The Louisiana Waterthrush’s distinctive song is preceded by a short series of very loud, down-slurred, piercing whistles, followed by a cascading series of jumbled whistles. Tail-bobbing is characteristic of both waterthrushes but, this behaviour is particularly exaggerated in this species (Dunn and Garrett 1997). Where their breeding ranges overlap, both species can sometimes be found occupying swamp forest, but the Louisiana Waterthrush is more apt to be found along coldwater streams (Craig 1985).

Figure 1. Adult Louisiana Waterthrush at nest with young.

Photo by Michael Patrikeev with permission.

Long description for Figure 1

Photo of an adult Louisiana Waterthrush (Parkesia motacilla) with young in the nest. The Louisiana Waterthrush is a relatively large, drab wood-warbler that resembles a small thrush. The upper parts are dull brown. The lower parts are cream-coloured, with dark streaking on the breast and flanks. A bold, broad, white streak over the eye extends to the nape. The legs are pink, and the bill is rather long and heavy for a warbler.

Population Spatial Structure and Variability

There is no evidence of population structuring within the small Canadian population of this species. Within the United States, eastern birds tend to be slightly larger than those in the west (Eaton 1958).

Designatable Units

There are no biological, genetic or geographic distinctions that warrant assessment below the species level. This report deals with a single designatable unit.

Special Significance

This species is considered a habitat specialist and is the only stream-dependent songbird in eastern North America (Mulvihillet al. 2008). Within its breeding and wintering ranges, the Louisiana Waterthrush is likely an excellent bio-indicator of the health of headwater, medium-gradient, coldwater streams and large, intact, mature deciduous forested swamps (Buffington et al. 1997; Prosser and Brooks 1998; Mulvihill et al. 2002; O’Connell et al. 2003; Mattsson and Cooper 2006; Mattsson and Cooper 2009). Due to its preference for clear, coldwater streams, the breeding habitat of this species often overlaps with trout streams (e.g., Stucker 2000).

It is also classified an area-sensitive forest bird that requires large tracts of contiguous, closed canopy forest for breeding (Robbins 1979; Freemark and Collins 1992). The breeding habitat requirements overlap with those of two other forest songbirds that are designated as Endangered in Canada: the Acadian Flycatcher (Empidonax virescens) and Prothonotary Warbler (Protonotaria citrea); these species co-occur at some sites in Ontario (COSEWIC 2007, 2010; Environment Canada 2012).

No Aboriginal traditional knowledge is currently available for this species.

Distribution

Global Range

Breeding

The Louisiana Waterthrush breeds from eastern Nebraska, north central Iowa, east central and southeastern Minnesota, central Wisconsin, southern Michigan, southern Ontario, central New York, central Vermont, central New Hampshire, and southern Maine south to eastern Kansas, eastern Oklahoma, eastern Texas, central Louisiana, southern Mississippi, southern Alabama, northern Florida, central and southwestern Georgia, central South Carolina, and central and northeastern North Carolina (Figure 2). The bulk of its 2,400,000 km2 breeding range (>99%) is within the eastern United States (Partners in Flight Science Committee [PIFSC] 2013).

Over the last century, its breeding range expanded slowly northward in the northeastern U.S. (Mattsson et al. 2009). This range expansion is probably attributed to re-colonization of formerly held territory that was heavily lumbered in the 1800s and is now largely reforested (Brewer et al. 1991). The northward expansion of the U.S. range seems to have halted (Mattsson et al. 2009). Since the 1980s, a reduction in distribution has been observed in northern New York (Rosenberg 2008) and southwestern Michigan (Hull 2011), but not in Vermont (Kibbe 2013) or Pennsylvania (Mulvihill 2012).

Figure 2. Global range of the Louisiana Waterthrush.

(Map from Environment Canada 2012, based on Ridgely et al. 2007).

Long description for Figure 2

Map of the global range of the Louisiana Waterthrush, indicating breeding, migration, and wintering areas. The species breeds from eastern Nebraska, north central Iowa, east central and southeastern Minnesota, central Wisconsin, southern Michigan, southern Ontario, central New York, central Vermont, central New Hampshire, and southern Maine south to eastern Kansas, eastern Oklahoma, eastern Texas, central Louisiana, southern Mississippi, southern Alabama, northern Florida, central and southwestern Georgia, central South Carolina, and central and northeastern North Carolina. It winters from northern Mexico, south through Central America to central Panama, northeastern Colombia and northwestern Venezuela, and throughout the West Indies.

Wintering

The Louisiana Waterthrush winters from northern Mexico, south through Central America (mainly at higher elevations; both slopes, although more commonly on the Gulf/Caribbean side) to central Panama, rarely to northeastern Colombia and northwestern Venezuela; also throughout the West Indies but progressively less numerous moving southward (Mattsson et al. 2009; Figure 2). Over 25% of the 1,729,000 km2 wintering range is in Mexico (Berlanga et al. 2010).

Canadian Range

Breeding

In Canada, the Louisiana Waterthrush breeds regularly in southern Ontario (Figure 3), where it is considered a rare, local summer resident (Eagles 1987; James 1991; McCracken 2007; Environment Canada 2011, 2012; Sandilands 2014). It is a rare and sporadic breeding bird in southwestern Quebec (Figure 4), where in 2006 it was confirmed nesting at one site (Savignac 2006) and has also been reported during the breeding season at several other sites (David 1996; St-Hilaire and Dauphin 1996; Savignac 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008; Les Oiseaux du Québec 2014; M. Robert, pers. comm. 2014; Québec BBA 2015).

Figure 3. Breeding distribution of the Louisiana Waterthrush in Ontario in three time periods: 1981-1985 (Cadman et al. 1987), 2001-2005 (Cadman et al. 2007) and 2006-2014 (compiled records).

Long description for Figure 3

Map showing breeding distribution of the Louisiana Waterthrush in southern Ontario during three time periods: 1981 to 1985, 2001 to 2005, and 2006 to 2014.

Figure 4. Breeding distribution of the Louisiana Waterthrush in Quebec in three time periods: 1984-1989 (Gauthier and Aubry 1996), 2005-2009 (compiled records; see Table 1 for details) and 2010-2014 (Québec Breeding Bird Atlas 2014).

Long description for Figure 4

Map of the breeding distribution of the Louisiana Waterthrush in Quebec during three time periods: 1984 to 1989, 2005 to 2009, and 2010 to 2014.

In Canada, this species is highly localized, because it is associated with various physiographic features that provide the necessary combination of habitat and climatic conditions. The main concentration of Louisiana Waterthrush in Ontario is associated with the forested ravines and wetlands in the Norfolk Sand Plain (Norfolk, eastern Elgin, and southern Oxford counties). Other isolated breeding sites in southern Ontario are associated with various river systems (Ausable, Bayfield, Grand, Thames, and Maitland rivers), forested sites along the Great Lakes shoreline, and some inland forested wetlands. In south-central Ontario, this species breeds along relatively pristine headwater streams (and also some higher order streams with seepages and/or side streams) associated with the Niagara Escarpment, particularly in the central section of the escarpment from Hamilton to Collingwood. In southeastern Ontario, there is a small cluster of occurrences associated with small streams and wetlands near Frontenac Park in Ontario’s Frontenac Arch physiographic region. This species has also been found sporadically at other scattered sites in southeastern Ontario, including the eastern Oak Ridges Moraine, the Rice Lake Plains and the fringe of the Southern Shield

The only confirmed nesting records in Quebec are from a site on the Eardley Escarpment in Gatineau Park in the Outaouais region, an area where the species has been observed intermittently since at least 1974 (Savignac 2005, 2006, 2007, 2008). There are also several historical and recent breeding season reports from a cluster of sites in the Estrie region in southern Quebec, at the northern end of the Appalachian Mountain region (St-Hilaire and Dauphin 1996; Savignac 2005, 2008; Les Oiseaux du Québec 2014). During the 2010-2014 Québec Breeding Bird Atlas fieldwork (Figure 4), this species was reported from four 10 x 10 km squares, including two squares with probable breeding evidence in the Estrie region and two squares with possible breeding evidence in the Outaouais region (Québec BBA 2015).

A single singing male sighted in Welsford, New Brunswick was the only record in the first Maritimes Breeding Bird Atlas (1986-1990; Erskine 1992), and it likely represents a transient unpaired bird. This species was not recorded in the second Maritimes atlas (2006-2010; Maritimes BBA 2014).

The distribution of the Louisiana Waterthrush in Canada is governed by the availability of suitable habitat within climatic confines. In Ontario, it nests primarily in the extensively settled Carolinian ecoregion (Deciduous Forest region) and adjacent areas of the Great Lakes - St. Lawrence Forest region south of the Canadian Shield (McCracken 2007). The species’ distribution in Ontario is consistent with regions above the 6oC mean yearly isotherm and elevations less than 300 m (McCracken 1991). In Quebec, this species may be restricted to areas with relatively mild microclimates, such as stream valleys on south-facing hillsides and escarpments in the extreme southwestern part of the province.

The extent of the known breeding range of this species in Canada has increased gradually over the past century (Page 1996). However, this apparent northward range expansion may be largely attributable to improved knowledge of a previously under-reported species and/or resettlement of its pre-European settlement historical range.

The cluster of occurrences on the north shore of Lake Erie has long been recognized (MacClement 1915). The species became established as a regular breeder at a handful of sites in Frontenac County near Kingston in southeastern Ontario during the 1980s (Weir 2008). Targeted surveys in 2012 and 2013 found that this species is more widespread along the Niagara Escarpment (Hamilton, Halton, Peel, Dufferin, Simcoe and Grey counties) than previously known (Friesen and Lebrun-Southcott 2012; Lebrun-Southcott and Friesen 2013). There are a few other isolated sites that are occupied somewhat regularly (e.g., some sites in Middlesex and Lambton counties), but most other scattered occurrences in Ontario and the few occurrences in southwestern Quebec appear to be sites with sporadic occupancy. Moreover, this species has not been reported recently in some parts of its former Ontario range (e.g., Essex, Chatham-Kent, Niagara; see also Population Trends section).

As indicated by changes in distribution for the three time periods shown in Figures 3 and 4, there has been a relatively high turnover in occupied sites in Ontario and Quebec. For example, of 40 squares (10 km x 10 km) with breeding evidence during the 1981-1985 Ontario BBA, only 15 (37.5%) were still occupied during the 2001-05 BBA (McCracken 2007). Since 2005, breeding evidence has been reported for 15 additional squares, where no breeding evidence was found during either Ontario BBA. In Quebec, this species has not been reported since 2007 at the only confirmed breeding site in the province, but probable nesting evidence was reported at other sites (Savignac 2008; Québec BBA 2015).

Non-breeding

Being at the northern limits of its range in Canada, the Louisiana Waterthrush is rare on migration. At migration hotspots such as Point Pelee and Long Point, it is considered a regular but uncommon spring migrant, and is rarely reported in fall (McCracken 1991; Parks Canada Agency 2012; Long Point Bird Observatory 2014).

It is considered a “rare vagrant” in Nova Scotia (Tufts 1986), where 12 of 16 records since 1966 are from the fall period (McLaren 2012). This reflects a well-established pattern of southwest to northeast fall vagrancy for migrant passerine species in the province (McLaren 1981).

Extent of Occurrence and Area of Occupancy

The extent of occurrence (EOO) in Canada, as measured by a minimum convex polygon encompassing all occurrences with breeding evidence over the 2001-2014 period (as depicted in Figures 3 and 4) is about 110,000 km2. The EOO is about 20% smaller if outlying occurrences with only possible breeding evidence are excluded, or if only records for the past 10 years (2005-2014) are considered.

The index of area of occupancy (IAO) in Canada based on a 2 x 2 km grid and using all breeding occurrences for the 2005-2014 period is 356 km2. Given that new sites continue to be found, the actual IAO could approach 500 km2. However, not all sites are occupied every year, so this would clearly represent an upper limit.

Search Effort

Understanding of the breeding distribution of this species in Canada has improved greatly as a result of breeding bird atlas projects in Ontario during 1981-1985 and 2001-2005 (Eagles 1987; McCracken 2007) and in Quebec during 1984-89 and 2010-2014 (St-Hilaire and Dauphin 1996; Québec BBA 2015), as well as the accumulation of breeding season observations detected during regional and local ecological surveys and bird checklist programs. Systematic targeted searches of known and potential Louisiana Waterthrush habitat have also been conducted in most parts of the Canadian range over the past decade. See Table 1 and Sampling Effort and Methods section for additional details.

| Project | Protocol | Project Area | Years | Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas | General surveys of breeding birds in 10 km x 10 km squares | Ontario | 2005 | 21 records from 11 atlas squares (2005 only). | Cadman et al. 2007 |

| Environment Canada Quebec Region: Louisiana Waterthrush surveys | Targeted surveys of known sites and suitable Louisiana Waterthrush habitat | Southwestern Quebec: Outaouais Region and Gatineau Park | 2005 | 1 single male at 1 of 18 sites | Savignac 2005 |

| Environment Canada Quebec Region: Louisiana Waterthrush surveys | Targeted surveys of known sites and suitable Louisiana Waterthrush habitat | Southwestern Quebec: Outaouais Region and Gatineau Park | 2006 | 1 pair and 1 single male at 2 of 21 sites (including first confirmed breeding for Quebec) | Savignac 2006 |

| Environment Canada Quebec Region: Louisiana Waterthrush surveys | Targeted surveys of known sites and suitable Louisiana Waterthrush habitat | Southwestern Quebec: Outaouais Region and Gatineau Park | 2007 | 1 pair at 1 of 6 sites | Savignac 2007 |

| Environment Canada Quebec Region: Louisiana Waterthrush surveys | Targeted surveys of known sites and suitable Louisiana Waterthrush habitat | Southwestern Quebec: Outaouais, Montérégie, Estrie Regions | 2008 | No birds at 20 sites | Savignac 2008 |

| Frontenac Bird Studies: Louisiana Waterthrush surveys | Targeted surveys | Southeastern Ontario: Frontenac Park study area (Frontenac County, Ontario) | 2010 | 1 pair, 4 single males at 5 of 17 sites | D. Derbyshire, pers. comm. 2014 |

| Frontenac Bird Studies: Louisiana Waterthrush surveys | Targeted surveys | Southeastern Ontario: Frontenac Park study area (Frontenac County, Ontario) | 2011 | 2 pairs, 2 single males at 4 of 28 sites | D. Derbyshire, pers. comm. 2014 |

| Frontenac Bird Studies: Louisiana Waterthrush surveys | Targeted surveys | Southeastern Ontario: Frontenac Park study area (Frontenac County, Ontario) | 2012 | 1 pairs , 2 single males at 3 of 14 sites | D. Derbyshire, pers. comm. 2014 |

| Bird Studies Canada: Forest Birds at Risk surveys | Targeted surveys | Southwestern Ontario: Norfolk Sand Plain (Norfolk Co. and Elgin Co.) | 2011 | 7 pairs, 6 single males, 7 nests at 11 of 31 sites | Allair et al. 2013 |

| Bird Studies Canada: Forest Birds at Risk surveys | Targeted surveys | Southwestern Ontario: Norfolk Sand Plain (Norfolk Co. and Elgin Co.) | 2012 | 17 pairs, 7 single males, 8 nests at 17 of 67 sites | Allair et al. 2013 |

| Bird Studies Canada: Forest Birds at Risk surveys | Targeted surveys | Southwestern Ontario: Carolinian ecoregion | 2013 | 11 pairs, 6 single males, 8 nests at 13 of 54 sites | Allair et al. 2014 |

| Bird Studies Canada: Forest Birds at Risk surveys | Targeted surveys | Southwestern Ontario: Carolinian ecoregion | 2014 | 13 pairs, 4 single males, 12 nests at 12 of 59 sites. | Allair et al. 2014 |

| Environment Canada: Louisiana Waterthrush surveys | Targeted surveys. | South-central Ontario: Niagara Escarpment | 2012 | 31 males, 8 females at 13 of 134 sites | Friesen and Lebrun-Southcott 2012 |

| Environment Canada: Louisiana Waterthrush surveys | Targeted surveys. | South-central Ontario: Niagara Escarpment, | 2013 | 34 males, 5 or 6 females at 13 of 94 sites | Lebrun-Southcott and Friesen 2013 |

| Environment Canada: Louisiana Waterthrush surveys | Targeted surveys. | South-central Ontario: Oak Ridges Moraine | 2014 | 4 males at 4 of 29 sites | Campomizzi et al. 2014 |

| Québec Breeding Bird Atlas, 2nd | General surveys of breeding birds in 10 km x 10 km squares | Quebec | 2010-2014 | 5 records from 4 atlas squares | QBBA 2015 |

| Ebird Canada | Casual birding observations | Ontario and Quebec | 2005-2013 | 414 records (mostly migrants, includes duplicate records) | Bird Studies Canada and Cornell Lab of Ornithology 2014 |

| Les Oiseaux du Québec | Summary of rare bird reports | Quebec | 2005-2014 | 7 records published in QuébecOiseaux | Les Oiseaux du Québec 2014 |

Habitat

Habitat Requirements

Breeding Habitat

The Louisiana Waterthrush nests amongst the roots of fallen trees, in niches of steep stream banks, and in and under mossy logs and stumps (Prosser and Brooks 1998; Mattsson et al. 2009; Ontario Nest Record Scheme [ONRS] 2014). Nests are generally well concealed by roots and hanging vegetation and are usually situated within a few metres of water (Mattsson et al. 2009; ONRS 2014). Mean canopy cover above 60 nests in Pennsylvania was 75% (Mattsson et al. 2009).

Of 40 nests found across several sites in Ontario in 2010-2014, 28 (79%) were found in ravines (Bird Studies Canada [BSC] 2014b). All of the ravine nests were situated in the stream bank, except for 2 in root tip-ups. Of 12 nests found in swamps, 9 were in root tip-ups and 3 in stumps. Almost all were located over water in mixed forests.

The Louisiana Waterthrush occupies specialized habitat, showing a strong preference for nesting along relatively pristine, headwater streams and associated wetlands situated in large tracts of mature forest (Mattsson et al. 2009). Breeding sites in the U.S. are typically along medium- to high-gradient, first- to third-order, perennial streams with gravel-bottoms in hilly areas (Mattsson et al. 2009). While the Louisiana Waterthrush favours running water, less frequently it inhabits heavily wooded swamps with vernal or semi-permanent pools, where its territories can overlap with Northern Waterthrush (Craig 1984, 1985). Habitat suitability models for parts of the U.S. range found that headwater streams with well-developed pools and riffles situated in large (>350 ha), late successional, deciduous or mixed forests with closed canopies and open understories in areas with high forest cover (>70%) are highly suitable habitat for this species (Prosser and Brooks 1998; Tirpak et al. 2009). Shrubby habitats near the nesting site may be important for young and adults during the post-breeding period (Vitz and Rodewald 2006, 2007).

Forests at occupied sites in Ontario and at Gatineau Park, Quebec are generally late-successional mixed or deciduous forest, typically with maple (Acer sp.) and Eastern Hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) components (unpubl. data from targeted surveys, see references in Table 1). Riparian territories in Ontario are typically associated with steep-walled forested ravines in sand plain areas, or rocky streams in incised valleys (Friesen and Lebrun-Southcott 2012; Lebrun-Southcott and Campomizzi 2014; J. Allair, pers. comm. 2014; J. Holdsworth, pers. comm. 2014).

Robbins (1979) regarded the Louisiana Waterthrush as an “area-sensitive” species -- one that requires large tracts of unbroken forest. Based upon studies in Maryland, he estimated that the minimum contiguous forest cover required to sustain a viable breeding population of Louisiana Waterthrushes was about 100 ha, although this species also regularly occurs in smaller forest patches (~25 ha) in some parts of its U.S. range (Sandilands 2014). Freemark and Collins (1992) also listed the Louisiana Waterthrush as an area-sensitive species, but did not suggest a minimum forest size, noting that area requirements are very much influenced by the regional pattern of forest cover. Although the area-sensitive classification of this species has not been rigorously tested (Parker et al. 2005), there is evidence that the species is sensitive to forest fragmentation (Prosser and Brooks 1998; Tirpak et al. 2009).

In its U.S. range, this species is generally encountered infrequently in streams having very narrow (<100 m) forest corridors (Keller et al. 1993; Mason et al. 2007). However, occupancy of riparian strips is also influenced by land cover and land use in the surrounding landscape matrix (Triquet et al. 1990; Peak and Thompson 2006; Rodewald and Bakerman 2006).

An analysis of land cover within 200 m at 110 sites along the Niagara Escarpment where Louisiana Waterthrush had been detected from 1981 to 2013 was recently completed (Lebrun-Southcott and Campomizzi 2014). This study found nearly total mixed and/or deciduous forest cover within 200 m of the majority of detection locations. Most (85%) detection points also had >50 ha of total forest cover within the 100 ha buffer. However, many detection points (45%) had between 20 and 60 ha of agricultural land cover within the 100 ha buffer, suggesting that in some parts of its Ontario range this species may not be as area-sensitive as previously reported (Lebrun-Southcott and Campomizzi 2014).

Migration Habitat

During migration, the Louisiana Waterthrush occurs in habitats similar to those in the breeding range and in a variety of non-typical habitats where flowing or standing water and sufficient canopy cover is available (Curson et al. 1994; Dunn and Garrett 1997; Mattsson et al. 2009).

Wintering Habitat

In winter, it is found in tropical evergreen forests and favours riparian woodland in hilly and montane areas (Mattsson et al. 2009; Berlanga et al. 2010). It is less common along streams in lowland areas and mangrove forests, which are favoured by Northern Waterthrushes (Mattsson et al. 2009). In Costa Rica, radio-tagged birds foraged mostly along streams, but also exploited food-rich ground substrates in off-stream habitats, including residential areas and wet pastures (Master et al. 2005; Hallworth et al. 2011).

Habitat Trends

Breeding Habitat

Many of southwestern Ontario’s historical wetland forests have disappeared, have been heavily fragmented, and/or have been drained for agricultural or development purposes (Snell 1987; Page 1996; Larson et al. 1999; Crins et al. 2007; Environment Canada 2014b). There are few, large intact blocks of deciduous swamp forest remaining in this region. Loss of Louisiana Waterthrush nesting habitat within forested ravines has occurred as well, but not to the same extent. Nonetheless, the quality of primary nesting habitat in forested ravines has undoubtedly declined appreciably in some regions owing to forest fragmentation, logging, stream pollution, and siltation. In contrast, the amount and quality of forested stream habitat in parts of southeastern Ontario, and along some sections of the Niagara Escarpment in south-central Ontario, have likely improved over the past century due to the replanting and regeneration of forests in protected areas and on marginal farmlands (Crins et al. 2007).

Forests and wetlands in much of southwestern Quebec have also been negatively impacted by agriculture, urbanization and forestry (Jobin et al. 2010). However, the Louisiana Waterthrush occurrences in this province are in areas with a relatively high proportion of forest cover (Environment Canada 2013a, b). Other than in areas affected by urban sprawl, there was little change in the extent of forest and wetland cover in southwestern Quebec between 1993 and 2001 (Jobin et al. 2010).

Despite significant historical and ongoing losses in the extent of Louisiana Waterthrush habitat in southern Ontario, there are areas of suitable habitat that are either not occupied or are occupied intermittently (COSEWIC 2006; J. Allair, pers. comm. 2014; Friesen and Lebrun-Southcott 2012; D. Derbyshire, pers. comm. 2014). There are also areas of apparently suitable habitat in southwestern Quebec that are not occupied (Savignac 2008). Failure to occupy all available habitat in Canada is likely because this is the northern periphery of the species’ range, and the population here is small and patchy.

Non-breeding Habitat

No specific recent information on habitat trends on migration stopover or wintering grounds is available. A recent threat assessment determined that this species faces elevated threats during the non-breeding period, due to deforestation and development pressures adversely affecting riparian forest habitat (PIFSC 2012). Since 2000, rates of deforestation in Central America and the Caribbean have slowed, and in some countries and regions reversed (Redo et al. 2012; Aide et al. 2013). However, degraded water quality is still a significant issue in some parts of the wintering range, including the Dominican Republic (Latta 2011) and Puerto Rico (Hallworth et al. 2011).

Biology

Life Cycle and Reproduction

Male Louisiana Waterthrushes sing profusely when they arrive on their breeding territories in April and early May. (Eaton 1958; Bent 1963; Mattsson et al. 2009; Bickerton and Walters 2011). Males aggressively defend their territories against conspecifics (Craig 1984; Mattsson et al. 2009). Along stream courses, territories are essentially linear (Mattsson et al. 2009). There is considerable local and regional variation in the length of riparian territories reported (range 90 to 1440 m), but most territories are in the 300 to 600 m range (Mattsson et al. 2009, 2011). Variation in territory size may reflect variable mating systems (polygnous males have large territories) and/or food availability (Mulvihill et al. 2002; Mulvihill et al. 2008; Mattsson and Cooper 2009). The average size of territories in Canada is not known, but the previous estimate of 2 ha (COSEWIC 2006) is likely reasonable (e.g., average territory length of 400 m and width of 50 m along streams, and 140 m diameter circle in forest swamps).

Mating is generally monogamous, but up to 2% of males may have two females (Mulvihill et al. 2002; Mattsson and Cooper 2009). Pairing success is generally high (e.g., in Pennsylvania 84% of males (n=55) on acidified streams and 92% (n=152) of males on circum-neutral streams (pH near 7) were paired; Mulvilhill et al. 2008). Many territorial males in Canada, however, appear to be unpaired (Savignac 2006; J. Allair, pers. comm. 2014; D. Derbyshire, pers. comm. 2014). Pairing rates reported during intensive targeted surveys in Canada range from 36% in Frontenac Park, Ontario (Frontenac Bird Studies 2014) to 70% in the Norfolk Sand Plain (BSC 2014b) (see Table 1). As females can be secretive, reported pairing rates may underestimate the actual proportion of territorial males that represent breeding pairs. Given the available information, pairing success in Canada is likely between 66% and 75%.

Egg dates in Ontario range from 1 May - 8 July, including re-nesting attempts after failed nests (Peck and James 1998; ONRS 2014). Depending on latitude, the nesting period may start anywhere between late April in southwestern Ontario to early May in the northern part of the breeding range and may end anywhere between mid-June to early July (Rousseu and Drolet 2015). Incubation extends from 12-14 days. Both parents assist with feeding the young, which remain in the nest for about 10 days (Bent 1963; Mattsson et al. 2009). Parents attend to fledglings for up to 4 weeks (Mattsson et al. 2009).

Clutch size ranges from 4-6 eggs (Bent 1963; ONRS 2014). The Louisiana Waterthrush is generally single-brooded, but second broods have been documented in the U.S. (Mattsson and Cooper 2007; Mulvilhill et al. 2009). Second (and even third) re-nestings are common if the first nest is destroyed early in the season (Mattsson et al. 2009).

Nests of the Louisiana Waterthrush are sometimes parasitized by Brown-headed Cowbirds (Molothrus ater). Parasitism rates are highly variable across the breeding range, but are generally higher in the U.S. midwest (e.g., 33% to 81% at two sites in Illinois, n=15 and n=11, respectively; Mattson et al. 2009) and low in the U.S. northeast (e.g., 4% in Pennsylvania, n=222, O’Connell et al. 2003), and southeast (0% in Georgia, n=190; Mattssonand Cooper 2009). In southern Ontario, a relatively high proportion of nests contain one or more cowbird eggs (e.g., 22.8% of nests with eggs reported to ONRS 2014). While Louisiana Waterthrushes can successfully fledge a brood containing cowbird and waterthrush young, the reduction in the number of host young fledged may approach 50% (Mattsson et al. 2009).

Mean daily nest survival is relatively high (0.97 in Georgia and Pennsylvania; Mattsson et al. 2011). Depredation was the main source of nest failure in U.S. studies (Mattsson and Cooper 2009; Mulvihill et al. 2009). Comparable productivity statistics are not available for the Canadian population, but nest monitoring in Norfolk and Elgin counties found that 63% of nests with known outcomes (n=38) fledged at least one Louisiana Waterthrush young (BSC 2014b). This is similar to nest success rates reported in U.S. studies (e.g., 59% of 190 nests in Georgia, Mattsson and Cooper 2009; 52% of 231 nests in Pennsylvania; Mulvihill et al. 2009).

Mean fecundity (number of young that reach fledgling age per female) in Georgia was 2.89 +/-1.86, n=130 (Mattsson and Cooper 2007), and 3.4 +/- 0.2, n=175 in Pennsylvania (Mulvihill et al. 2008). In the latter study, there was no change in nest success or annual fecundity of nests on acidified streams compared to circum-neutral streams despite smaller clutch sizes. However, the number of young produced was much lower on acidified streams due to larger territories resulting in lower nesting densities (Mulvihill et al. 2008). An analysis using a stochastic individual-based model and data from 418 nests in Georgia and Pennsylvania predicted that about half of all females should fledge at least 1 young (Mattsson et al. 2011).

Louisiana Waterthrushes mature in one year and, like most small birds, generally have a short life span. The longevity record is 11 years, 11 months (Mattsson et al. 2009; Lutmerding and Love 2014). The average age of breeding adults in the population is likely 2-3 years.

Mean apparent annual survival rates range from 0.53 (SE=0.05, n=379) in the southeast U.S., to 0.46 (SE=0.11, n=86) in south-central U.S., and 0.47 (SE=0.06, n=222) in the northeast U.S. (Michel et al. 2011). The proportion of females banded as adults re-sighted the following year later ranged from 26% in Georgia (n=58), to 47% and 55% in two Pennsylvania studies; whereas the proportion of males ranged from 34% in Georgia, to 50% and 39% in the Pennsylvania studies (see Mattsson et al. 2009). In Pennsylvania, birds nesting on acidified streams were less likely to return and the proportion of inexperienced first-time breeding birds was higher there than on circum-neutral streams (Mulvihill et al. 2008). Relatively few birds (5% to 10%) continue to return for 2 or more years after banding. In a 4-year study in southwestern Ontario, 43% of colour-banded adult females (n=14) and 29% of males (n=14) were re-sighted the following year (Allair et al. 2014). Based on this small sample, return rates (apparent survival rates) in southwestern Ontario appear to be similar to those reported in the U.S.

For young birds, fidelity to natal areas is low. In two U.S. studies, very few (0 of 49 in Tennessee and 1 of 240 in Pennsylvania, Mattson et al. 2009) colour-marked nestlings were re-sighted in subsequent years. Five of 73 birds banded as nestlings at sites in the Norfolk County area of southwestern Ontario between 2011 and 2014 were re-sighted the following year, up to 12 km (average 8 km) from their natal site (S. Dobney pers. comm. 2015).

Physiology and Adaptability

The Louisiana Waterthrush spends most of its time on or near the ground, along the margins of streams and pools, and even wading in shallow water (Bent 1963; Mattsson et al. 2009). Although able to tolerate moderate levels of direct human disturbance, the Louisiana Waterthrush is particularly susceptible to habitat perturbations, including deforestation, loss of canopy cover, fluctuating water levels, water pollution, and siltation (Mattsson et al. 2009).

Dispersal and Migration

The Louisiana Waterthrush is a long-distance migrant that arrives in southern Ontario much earlier than most other wood-warblers. Usual dates in the province range from late April to early September (James 1991). By mid-August, most birds from Canada have migrated south (Curson et al. 1994).

No important areas of concentration of migrant Louisiana Waterthrushes are known, and the species is believed to migrate solitarily or in small numbers across a broad front (Dunn and Garrett 1997; Curson et al. 2004; Mattsson et al. 2009). During spring migration, the species occurs fairly regularly in small numbers along the north shore of Lake Erie (e.g., Long Point, Point Pelee, Rondeau).

Fledged young remain along natal streams for about a month, then wander progressively farther (up to 5 km) away, unattended by parents (Eaton 1958). There is some evidence that young and adults move into dense shrubby areas in the post-fledging period, which is when adult birds undergo a complete moult (Vitz and Rodewald 2006, 2007; Mulvihill et al. 2009).

Annual fidelity to breeding areas has been recognized (see Life Cycle and Reproduction above, and Mattsson et al. 2009). In Pennsylvania, Mulvihill et al. (2002) reported that up to 50% of females reoccupied territories from the previous year, “not infrequently with the same mate.” Site fidelity and fidelity to previous mates have also been observed in Ontario (Allair et al. 2014). Site-tenacity has also been documented in the wintering grounds (Mattsson et al. 2009). Wintering birds appear to actively defend feeding territories ranging from 0.3 ha to 11 ha (Mattsson et al. 2009).

Diet and Foraging Behaviour

The Louisiana Waterthrush feeds mostly on aquatic macro-invertebrates, including mature and immature insects. It also sometimes eats small molluscs, fish, crustaceans, and amphibians (Eaton 1958; Bent 1963; Mattsson et al. 2009). The diet is quite atypical of other songbirds.

Aquatic foraging is commonplace, particularly early in the breeding season. Submerged and floating organisms are eaten (Eaton 1958; Craig 1984). The following types of aquatic organisms have been reported in the summer diet: Trichoptera, Ephemeroptera nymphs, and Diptera larvae (especially chironomids), Culicidae, Dytiscidae, isopods, and gastropods (Eaton 1958; Craig 1984; Mattsson et al. 2009). Terrestrial organisms included centipedes, caterpillars, adult mosquitoes, earthworms, spiders, and various emerging aquatic insects.

Important aquatic prey includes taxa that are sensitive to changes in water quality, particularly Ephemeroptera (mayflies), Plecoptera (stoneflies) and Trichoptera (caddisflies). The Louisiana Waterthrush’s occupancy of headwater streams is positively associated with the proportion of these taxa in the macrobenthic biomass (Stucker 2000; Mattsson and Cooper 2006; Mulvihill et al. 2008).

Although the two species of waterthrush have similar diets and foraging ecologies (Craig 1984, 1985), the Louisiana Waterthrush typically selects larger prey items than the Northern Waterthrush and has a greater preference for Trichoperta larvae (Craig 1987). Its selection of larger prey may be related to its larger bill size (Craig 1987).

Interspecific Interactions

Where sympatric, Louisiana Waterthrushes do not appear to interact much with Northern Waterthrushes, even when occupying the same breeding habitats and sharing overlapping territories (Craig 1984, 1985; Mattsson et al. 2009). This lack of interspecific aggression may stem from differences in diet (Craig 1987).

Adults are preyed upon by small raptors, while nest contents are preyed upon by a variety of snakes, small mammals, and jays (Mattsson et al. 2009).

Population Sizes and Trends

Sampling Effort and Methods

Specialized search effort is required for this species because of its early breeding season and its specialized breeding habitat, which is often hard to access (Mattsson et al. 2009; Bickerton and Walters 2011; Mordecai et al. 2011; Environment Canada 2012). In addition, Louisiana Waterthrushes have relatively large and/or linear breeding territories that contribute to low detectability during point count surveys (Buskirk and MacDonald 1995; Bickerton and Walters 2011; Reidy et al. 2011). Detectability is improved if surveys are conducted between late April and the first three weeks of May (Bickerton and Walters 2011; Friesen and Lebrun-Southcott 2012; L. Friesen, pers. comm. 2015a), if survey points arelocated along stream corridors (Mattson and Marshall 2009), and especially if conspecific playback of songs is used (Stucker 2000; Bickerton and Walters 2011). Linear territories in riparian areas can exceed 1 km, so individuals can be detected at multiple survey stations, which can lead to overestimates of population size (Mordecai et al. 2011).

Due to its rarity and localized distribution, standard, broad-scale bird monitoring programs like the Breeding Bird Survey do not detect sufficient numbers of birds to provide robust abundance estimates or trends for the Canadian Louisiana Waterthrush population (Environment Canada 2012). It is only in the past decade that systematic searches targeting this species have been conducted across most of its Canadian range.

Breeding Bird Survey (BBS)

The Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) is a volunteer survey designed to monitor trends in North American breeding bird populations (Environment Canada 2014c; Sauer et al. 2014). BBS routes consist of 50 roadside points along randomly selected, stratified routes throughout North America. Each point is surveyed (3-minute point count) once annually during the breeding season. BBS data are analyzed using a hierarchical Bayesian model (Sauer and Link 2011). While this species is not well-sampled by this roadside-based survey and the timing of BBS surveys is later than its main calling period, the BBS is still the best source of information on continental population trends (Mattsson et al. 2009; PIFSC 2013; Sauer et al. 2014). However, it is not an effective method for monitoring Canadian trends because of small sample sizes here.

Breeding Bird Atlases

The two Ontario Breeding Bird Atlases provide comparable information on changes in bird distribution in the province between 1981-1985 and 2001-2005 (Cadman et al. 1987, 2007). Atlas data were gathered based on searches for all bird species within 10 km x 10 km squares for at least 20 hours over each of the two atlas periods. Although effort was comparable between the two atlases, better information on known and suitable habitat for this species was available to surveyors during the second atlas. Similarly, the two Quebec Breeding Bird Atlases reflect changes in bird distribution in that province between 1984-1989 and 2010-2014 (Gauthier and Aubry 1996; Québec BBA 2015).

Targeted Surveys

From 2005-2014, there have been several targeted surveys for Louisiana Waterthrushes in Ontario and Quebec (see Table 1). These systematic surveys largely focused on sites where the species had been previously reported, but additional sites with suitable habitat were also searched. Surveys were conducted following a species-specific survey protocol (similar to Bickerton and Walters 2011). To maximize detectability, surveys were generally conducted early in the breeding season and made use of conspecific audio-playbacks to elicit responses. The intensity of these targeted surveys varied considerably, with many sites being visited only once, while others received multiple visits in multiple years. Bird Studies Canada also carried out nest monitoring and colour banding of adults and young in Norfolk County, Ontario between 2011 and 2014.

Migration Counts

Standardized migration count data are collected annually at more than 20 Canadian Migration Monitoring Network (CMMN) stations across Canada (Bird Studies Canada 2014), but only Long Point Bird Observatory has recorded this species in sufficient numbers for population trend analysis. Analysis of spring migration data for Louisiana Waterthrushes at Long Point for 1961-2012 was provided by T. Crewe (pers. comm., 2014), using a generalized additive model with Poisson distribution.

Other Information Sources

Breeding occurrences of this species are tracked by provincial conservation data centres in Ontario and Quebec. The Ontario database includes information on 62 sites (element occurrences), whereas the Quebec database includes 4. Additional occurrence information is available in the eBird Canada program, and the Étude des population d’oiseaux du Québec (ÉPOQ database).

Abundance

The global Louisiana Waterthrush population is currently estimated to be 360,000 mature individuals (180,000 pairs) based on BBS data from 1998-2007 (PIFSC 2013). Its population is small relative to most other wood-warbler species (e.g., the Northern Waterthrush population is estimated at 19 million individuals).The bulk of its population is within the eastern United States, particularly in the Appalachian Mountain region (46%, Mattsson et al. 2009; PIFSC 2013). The PIF database provides an estimate of 140 individuals for Canada, but this estimate is flagged as being of very poor quality (Blancher et al. 2007b, 2013; PIFSC 2013). Nevertheless, the Canadian population clearly represents <1% of the total population.

As in past status reports, a Canadian population estimate was developed for each municipality (Table 2). This approach provides flexibility in accounting for considerable regional variation in search effort and habitat availability. The estimates are based on the number of known occurrences with breeding evidence between 2005 and 2014. This 10-year period includes targeted surveys, the final year of fieldwork during the second Ontario BBA, and fieldwork for the second Québec BBA (see Table 1). Occurrences were defined by assigning records to 1 km x 1 km grid squares. Available information was used to determine the maximum number of territories reported for each 1 km x 1 km site in any single year.

| Region | County/ Regional Municipality | Estimated No. Pairs 2005a Min. |

Estimated No. Pairs 2005a Max. |

Known Territories (Max/year) 2005–2014b | Estimated No.Territories 2014c Min. |

Estimated No.Territories 2014c Max. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southwestern Ontario | Essex, Chatham-Kent | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Southwestern Ontario | Lambton | 5 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Southwestern Ontario | Middlesex | 5 | 11 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Southwestern Ontario | Huron, Perth, Bruce | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Southwestern Ontario | Elgin | 30 | 45 | 14 (10) | 30 | 60 |

| Southwestern Ontario | Norfolk | 45 | 75 | 35 (14) | 30 | 60 |

| Southwestern Ontario | Oxford | 6 | 13 | 1 | 2 | 5 |

| Southwestern Ontario | Haldimand | 0 | 1 | - | 0 | 2 |

| Southwestern Ontario | Brant | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Southwestern Ontario | Waterloo | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Southwestern Ontario | Wellington | - | - | - | - | - |

| Southwestern Ontario | Sub-total | 93 | 165 | 53 | 66 | 145 |

| South-central Ontario | Niagara | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| South-central Ontario | Hamilton | 2 | 3 | 4 (2) | 2 | 5 |

| South-central Ontario | Halton | 1 | 4 | 20 (13) | 20 | 50 |

| South-central Ontario | Peel | - | - | 5 (3) | 5 | 12 |

| South-central Ontario | Dufferin | - | - | 7 (4) | 6 | 15 |

| South-central Ontario | Simcoe | 1 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 25 |

| South-central Ontario | Grey | 2 | 4 | 10 (6) | 10 | 25 |

| South-central Ontario | Sub-total | 6 | 18 | 54 | 53 | 134 |

| Southeastern Ontario | Durham | - | - | 3 (2) | 2 | 5 |

| Southeastern Ontario | Northumberland | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Southeastern Ontario | Peterborough | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Southeastern Ontario | Hastings | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Southeastern Ontario | Lennox & Addington | - | - | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Southeastern Ontario | Frontenac | 5 | 8 | 12 (5) | 8 | 15 |

| Southeastern Ontario | Leeds & Grenville | - | - | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Southeastern Ontario | Sub-total | 6 | 12 | 19 | 10 | 30 |

| Central Ontario | Southern Shield | - | - | 0 | 5 | 10 |

| Southwestern Quebec | Estrie | - | - | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Southwestern Quebec | Montérégie | - | - | 3 (2) | 0 | 3 |

| Southwestern Quebec | Outaouais | - | - | 4 (2) | 0 | 3 |

| Southwestern Quebec | Sub-total | - | - | 7 | 0 | 7 |

| Canada | Total | 105 | 195 | 133 | 134 | 326 |

a. COSEWIC 2006 estimates for Ontario based largely on information provided by regional coordinators of the second Ontario Breeding Bird Atlas and assuming an average annual site occupancy rate of about 75%.

b. Known territories 2005-2014: sum of the maximum number of males reported in any year at each site (1 km2) where breeding evidence was reported at least once during past 10 years; (Max/year): is the maximum count of males in that region in any one year in the past 10 years.

c. Estimated No. Territories 2014: estimated number of territorial males per region based on occurrence information for past decade, amount of habitat, and input from individuals with local knowledge.

In total, 126 Louisiana Waterthrushes at 99 sites in 49 10 x 10 km squares were reported in Ontario over the 2005-2014 period (Table 2). In Quebec, 7 Louisiana Waterthrushes at 7 sites in 7 atlas squares were reported.

As noted in the previous status report (COSEWIC 2006), most Louisiana Waterthrush sites in Canada are occupied intermittently. Sites may be occupied for several successive years before being abandoned, presumably due to the death of one or both members of the pair, or changes in habitat suitability (COSEWIC 2006). In developing the regional population estimates, the distribution and intensity of the recent survey effort relative to the amount of potential habitat in each region was also taken into consideration. A high proportion of the historical sites have been surveyed at least once in the past 10 years, but targeted surveys did not include all historical sites on private lands, or regions with few occurrences. The targeted surveys also included many areas with apparently suitable habitat, which resulted in the discovery of many “new” sites for this species.

Two other factors considered were the proportion of the “known” sites with possible breeding evidence that constituted bona fide breeding territories (versus non-breeding, transient males), and the detectability of the species. About 21% (22 of 106) of the “known” sites are based on very limited breeding evidence, which was typically a singing male observed in suitable habitat on one occasion over the past 10 years. Several of these possible breeding records could represent transient males. As it is also likely that some birds were also missed during single-visit surveys at other sites, the net effect of these two factors on the population estimate was considered negligible.

As in previous status reports, regional population estimates were reviewed by individuals with local knowledge (see Acknowledgements). Unlike the previous population estimates, the estimates in Table 2 refer to the number of territories (males), rather than the number of breeding pairs. Recent intensive fieldwork indicates that many males do not appear to be paired (see Biology section). The overall Louisiana Waterthrush pairing rate in Canada is likely less than 75% (see Biology section). Therefore, the estimate of 134 to 326 territorial males in Canada (Table 2) likely represents a reproductive population of no more than 100 to 245 pairs. If the actual pairing rate is closer to 66%, then the reproductive population would be somewhat less (88 to 215 pairs, or 176 to 430 mature individuals). Taking all factors into consideration, it is estimated that there are 235 to 575 adults in the Canadian population. This would consist of 134-329 males and 101-246 females.

The number of squares with breeding evidence reported during the Ontario and Québec Breeding Bird Atlas projects provides a reasonably consistent, albeit indirect, measure of abundance. A previous population estimate based on the first Ontario Atlas in 1981-85 was 50-100 pairs based on 40 occupied squares (Eagles 1987), and 105 to 195 pairs based on the occupancy of 39 atlas squares (McCracken 2007). These previous estimates suggest the average number of pairs per reported square is somewhere between 1.25 and 5. Over the past 10 years, breeding evidence has been reported in a total of 56 squares in Canada (49 in Ontario, 7 in Quebec), which provides an alternative population estimate of 70 to 280 pairs (140 to 560 birds), which is fairly consistent with the estimate provided above.

Fluctuations and Trends

Documenting population change for the Louisiana Waterthrush in Canada is difficult because it is not monitored well by any survey program. As noted previously, ascertaining the presence/absence of this species requires specialized search effort. Moreover, intermittent site occupancy is common. While patterns of local extirpations and persistence are apparent in some regions, population increases are more difficult to assess, particularly in regions with little baseline information.

U.S. Population Trends

The continental population is sampled by many BBS routes (n=941) across the U.S., but abundance is low and the roadside survey design does not sample all breeding habitat (Saueret al. 2014). The range-wide BBS data suggest that the continental population has been increasing modestly over both the long term (1966-2013: 0.55% per year; 95% credible intervals (CIs): 0.07, 1.01), and the past 10 years (2003-2013: 1.80% per year; 95% CIs: 0.75, 2.87; Saueret al. 2014).

BBS population trends for U.S. states bordering Canada are not statistically significant. While Breeding Bird Atlas data show declines in distribution in New York (Rosenberg 2008) and Michigan (Hull 2011), modest increases were reported in Ohio (Ohio BBA II 2014), Pennsylvania (Pennsylvania BBA 2014), and Vermont (Vermont BBA 2014a, b). These atlas results have not been adjusted for increased effort and coverage.

Historical Changes in Canada

This species has long been recognized as a rare breeder in Ontario (Baillie and Harrington 1937). It is generally assumed that historically this species was more widespread and numerous prior to European settlement, and then declined as forests and wetlands were cleared (McCracken 1991).

The first Ontario BBA (1981-1985) fieldwork provided the first comprehensive assessment of this species in Canada, resulting in a population estimate of 50-100 pairs (Eagles 1987). Higher estimates of 150 to over 300 pairs made in the 1990s were influenced by new information that suggested that as many as 100 pairs could be breeding in Norfolk and Elgin counties (McCracken 1991; Page 1996). However, these higher estimates did not consider intermittent site occupancy and incomplete saturation of available habitat (COSEWIC 2006).