COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Pugnose Shiner (Notropis anogenus) in Canada 2002

- Document information

- COSEWIC Assessment Summary

- COSEWIC Executive Summary

- Abstract

- Species Information

- Distribution

- Habitat

- General Biology

- Population Sizes and Trends

- Limiting Factors

- Special Significance

- Protection

- Evaluation and Summary of Status

- Technical Summary

- Acknowledgements

- Literature Cited

- The Authors

Endangered 2002

COSEWIC

Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada

COSEPAC

Comité sur la situation des espèces en péril au Canada

COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows:

Please note: Persons wishing to cite data in the report should refer to the report (and cite the author(s)); persons wishing to cite the COSEWIC status will refer to the assessment (and cite COSEWIC). A production note will be provided if additional information on the status report history is required.

COSEWIC 2002. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Pugnose Shiner Notropis anogenus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 15 pp.

Holm, E. and N.E. Mandrak. 2002. Update COSEWIC status report on the Pugnose Shiner Notropis anogenus in Canada, in COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Pugnose Shiner Notropis anogenus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-15 pp.

Parker, B., P. McKee and R.R. Campbell. 1985. COSEWIC status report on thePugnose Shiner Notropis anogenus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 14 pp.

Également disponible en français sous le titre Rapport du COSEPAC sur la situation du méné camus (Notropis anogenus) au Canada

Pugnose Shiner -- Illustration from Scott and Crossman (1973). Used with permission by the authors.

©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2003

Catalogue No. CW69-14/309-2003E-IN

ISBN 0-662-34225-9

Assessment Summary – November 2002

Common name : Pugnose Shiner

Scientific name : Notropis anogenus

Status : Endangered

Reason for designation : The Pugnose Shiner has a limited, fragmented Canadian distribution, being found only in Ontario where it is subject to declining habitat quality. The isolated nature of its preferred habitat may prevent connectivity of fragmented populations and may prevent gene flow between existing populations and inhibit re-colonization of other suitable habitats.

Occurrence : Ontario

Status history : Designated Special Concern in April 1985. Status re-examined and uplisted to Endangered in November 2002. Last assessment based on an update status report.

The Pugnose Shiner (Notropis anogenus Forbes, 1885) is a small silvery minnow with a dark lateral band extending from the tail forward onto the snout. Its mouth is very small and upturned. Females reach 6 cm and males reach 5 cm. The Pugnose Shiner is most similar to the Blackchin Shiner (Notropis heterodon), which can be distinguished by its larger mouth. The Pugnose Minnow (Opsopoeodus emiliae) also has a small upturned mouth but, unlike the Pugnose Shiner, has typically 9 dorsal rays, dark areas on the dorsal fin and crosshatched areas on the upper side.

The Pugnose Shiner is found in the upper Mississippi River, Red River of the North, and Great Lakes basins. It is known from several tributaries of the Mississippi River in Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota. It has been documented from the Red River of the North drainage of Minnesota and North Dakota. In the Great Lakes drainage, it has been collected in marshes and tributaries of lakes Michigan and Huron, Lake St. Clair, western Lake Erie, eastern Lake Ontario and the upper St. Lawrence River. It has a spotty distribution in Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, New York and Ontario. It is now considered extirpated in Ohio.

In Canada, it is known from the Old Ausable Channel (southern Lake Huron drainage), Lake St. Clair, Lake Erie (Point Pelee, Rondeau Bay, Long Point Bay) and the St. Lawrence River between Eastview and Mallorytown Landing.

In Ontario, the Pugnose Shiner is found in quiet areas of large lakes, stagnant channels, and large rivers primarily on sand bottoms with organic detritus. Water is usually clear and it is usually found in association with aquatic vegetation, particularly Chara.

The Pugnose Shiner is a timid and secretive fish that seeks cover among aquatic plants, which also provide food and breeding sites. Lifespan is probably only three years. Spawning occurs from mid-May to July at temperatures of 21-29°C. Gravid females may have up to 1275 eggs but may not lay all of these. Pugnose Shiners consume a variety of small plant and animal foods up to 2 mm in size. Its diet includes plants such as Chara and filamentous green algae (e.g., Spirogyra), cladocerans such as Daphnia, Bosmina and Chydorus, small leeches and caddisfly larvae.

In Canada, the Pugnose Shiner has been recorded from six general locations and it is still established at four of these. It has not been collected In the St. Lawrence River near Gananoque since 1937, but was recently collected at sites east and west of this location. In Lake Erie it probably exists only in Long Point Bay where it was collected as recently as 1996. Despite more recent surveys, it has not been found at Point Pelee since 1941, or in Rondeau Bay since 1963. The Canadian Lake St. Clair populations, first discovered in the early 1980s, are most common in the open coastal marshes at the north end of the lake as exemplified by the capture of 281 individuals during an extensive survey of the Walpole Island marshes in 1999. It was first found in the Old Ausable Channel in 1983 and its continued presence was confirmed in 1997.

In the United States, population trends are uncertain. It continues to be collected at new sites but it has not been recorded from several early sites. Declines have apparently occurred in New York, Ohio, Michigan, Minnesota, Wisconsin and North Dakota.

Declines of the Pugnose Shiner have been attributed to increases in turbidity, loss of habitat from shore development and destruction of native near shore macrophytes. In Canada, parks on Point Pelee and Rondeau Bay that would presumably offer protection from habitat changes have failed to prevent its decline or extirpation. Potential limiting factors are unknown but could include habitat changes due to the introduced Eurasian Milfoil, Myriophyllum spicatum, and an increase in the number and diversity of predators and competitors.

Little is known of the ecological role of the rare Pugnose Shiner. Its strict habitat requirements makes it a good indicator of environmental quality.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) determines the national status of wild species, subspecies, varieties, and nationally significant populations that are considered to be at risk in Canada. Designations are made on all native species for the following taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fish, lepidopterans, molluscs, vascular plants, lichens, and mosses.

COSEWIC comprises representatives from each provincial and territorial government wildlife agency, four federal agencies (Canadian Wildlife Service, Parks Canada Agency, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the Federal Biosystematic Partnership), three nonjurisdictional members and the co-chairs of the species specialist groups. The committee meets to consider status reports on candidate species.

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) was created in 1977 as a result of a recommendation at the Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference held in 1976. It arose from the need for a single, official, scientifically sound, national listing of wildlife species at risk. In 1978, COSEWIC designated its first species and produced its first list of Canadian species at risk. Species designated at meetings of the full committee are added to the list.

Canadian Wildlife Service

The Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, provides full administrative and financial support to the COSEWIC Secretariat.

The Pugnose Shiner, Notropis anogenus, is a small member of the family Cyprinidae. It has a limited and disjunct distribution in the upper Mississippi River, Red River of the North and Great Lakes drainage basins. Recent collections indicate that reproducing populations are present in the Old Ausable Channel (southern Lake Huron drainage basin) and limited areas of the Canadian waters of Lakes Erie, Lake St. Clair and the St. Lawrence River. The species has apparently disappeared from two of the six known areas. The stability, size and range of the remaining four populations are poorly known. Therefore, it is recommended that the Pugnose Shiner be classified as classified as Threatened in Canada.

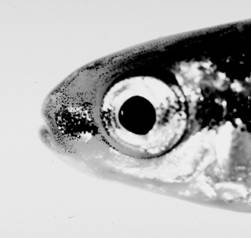

The Pugnose Shiner, Notropis anogenus Forbes 1885, (Fig. 1) is one of 83 species in the genus Notropis of the carp and minnow family Cyprinidae (Robins et al. 1991). Species in the genus Notropis can be distinguished from other genera in Cyprinidae by the presence of usually 8 dorsal rays, short intestine with 1 loop at front, scales on front half of side not much taller than wide (with a few exceptions), scales on nape about the same size as those on upper side (with a few exceptions), scales usually not appearing diamond-shaped, and pharyngeal tooth patterns of 0,4-4,0 to 2,4-4,2 (Page and Burr 1991).

The Pugnose Shiner is a small silvery fish with pale yellow to olive tints on back. A dark lateral band extends anteriorly onto the snout (chin, lower lip, side of upper lip) and ends posteriorly as a dark often wedge-shaped spot on the caudal peduncle. Scales on the back are darkly outlined. The scale row above the black lateral band frequently lacks pigment. All fins are transparent and, unlike most Notropis, the peritoneum is black. The body is fragile, slender and fairly compressed. Its mouth is very small and upturned. Maximum total length is 60 mm for females and 50 mm for males. This description is a compilation of diagnostic characters based on Bailey (1959), Scott and Crossman (1973), Becker (1983) and Page and Burr (1991).

Figure 1. Pugnose Shiner, Notropis anogenus, from Mitchell Bay, June 1996.

A: 46 mm TL.

B: 44 mm TL, close up of anterior part of body showing small upturned mouth.

A

B

B

Of the 15 species of Notropis collected in Canadian waters, the Pugnose Shiner is most similar to the Blackchin Shiner (N. heterodon) (Scott and Crossman 1973). The Pugnose Shiner was originally described by Forbes (1885) based on a collection of 24 specimens from the Fox River, Illinois (Bailey 1959). Of the eight remaining type specimens in the collection of the Illinois Natural History Museum, six are N. anogenus and two are N. heterodon exemplifying the similarity between the species (Scott and Crossman 1973). The two species can be distinguished by the very small, sharply inclined mouth that does not extend past the nostril in the Pugnose Shiner.

The Pugnose Shiner is also similar to the Pugnose Minnow (Opsopoeodus emiliae) and Bridle Shiner (Notropis bifrenatus) (Page and Burr 1991). The Pugnose Minnow has a small strongly upturned mouth; but, unlike the Pugnose Shiner, has typically 9 dorsal rays, dark areas on the dorsal fin, cross-hatched areas on the upper side, and a silvery-white peritoneum (Scott and Crossman 1973, Page and Burr 1991). Unlike the Pugnose Shiner, the Bridle Shiner has a larger, less upturned mouth, incomplete lateral line, 7 anal rays and silvery peritoneum (Scott and Crossman 1973, Page and Burr 1991).

Class:

Actinopterygii (ray-finned fishes)

Order:

Cypriniformes (carps)

Family:

Cyprinidae (carps and minnows)

Common Name:

Pugnose Shiner (English), méné camus (French)

Scientific name:

Notropis anogenus (Forbes, 1885)

Relationships of the Pugnose Shiner are not known but Bailey (1959) hypothesized that its closest relative is Notropis topeka because it “shares many structural characters and bears strong resemblance”. He also suggested that N. ortenburgeri and N. bifrenatus are perhaps related.

The Pugnose Shiner is found in the upper Mississippi River, Red River of the North, and Great Lakes basins (Figure 2). In the Mississippi drainage, it is found in several tributaries of the Mississippi River in Illinois, Wisconsin and Minnesota. It is found in the extreme (upper) Red River of the North drainage of Minnesota and North Dakota. In the Great Lakes drainage, it is found in tributaries of lakes Michigan and Huron, Lake St. Clair, western Lake Erie, eastern Lake Ontario and the upper St. Lawrence River. The centre of its Great Lakes distribution is Michigan with disjunct populations found in Illinois, Wisconsin, Ohio, New York and Ontario. It is now considered extirpated in Ohio (Trautman 1981).

In Canada, the Pugnose Shiner has been collected only in Ontario (see Appendix 1). It is known from Lake St. Clair, the Old Ausable Channel (southern Lake Huron drainage), three disjunct areas of Lake Erie (Point Pelee, Rondeau Bay, Long Point Bay) and the St. Lawrence River between Eastview and Mallorytown Landing (Figure 3).

Scott and Crossman (1973) suggested that the Canadian range is probably diminishing due to its extreme sensitivity to turbidity and its requirement for clear water and heavily vegetated habitats with clean sand or marl bottoms.

In Ontario, the Pugnose Shiner is found in quiet areas of large lakes, stagnant channels, and large rivers primarily on sand bottoms with organic detritus. Water is usually clear although individuals have been caught in water with a secchi reading as low as 0.3 m (Lake St. Clair, ROM 43420). It is almost always found in association with

aquatic vegetation, particularly Chara (Becker 1983, ROM unpublished data). It was captured on Walpole Island at 16 sites where it was found at a depth of up to 2.3 m over substrates containing muck and sand and occasionally silt and clay in areas that were usually heavily vegetated with submerged aquatic plants including Chara, Vallisneria, Heteranthera, Myriophyllum, Najas, Potamogeton, and Elodea (ROM unpublished data). The Walpole site and Lake St. Clair sites are not isolated from each other and likely constitute a single large population.

The pugnose shiner is a lithophil - a nonguarding, open substrate spawner -- which probably spawns in early to mid-June in Ontario (Leslie and Timmins 2002). Becker (1983) summarized life history data of Wisconsin populations. Spawning was not observed, but based on appearance of gravid females, it occurred from mid-May into July at temperatures of 21-29°C. Gravid females had 530-1275 eggs but some of these may not have been laid.

Average sizes (total length in mm) at age on 8 August in a Wisconsin population were: age I (38-44,0=42.0), age II (45-49, 0=46.3) and age III (52-53, 0=52.5) (Becker 1983). In Ontario, Leslie and Timmins (2002) found mean total length in age 0 fishes to be 24.1 mm.

Pugnose Shiners caught on 7 June 1996 in Mitchell Bay, Lake St. Clair were probably in the midst of spawning since some females appeared to be partially spent. Mature females were 41-56 mm TL (n=10) and mature males were 30-38 mm TL (n=10) (ROM, unpublished data).

Becker (1983) reported that, in Wisconsin, plants such as Chara and filamentous green algae (e.g., Spirogyra) were preferred over animal foods such as the cladocerans, Daphnia and Chydorus. Small leeches and trichopterans have also been observed in its diet (Carlson 1998).

Eight specimens from Mitchell Bay captured in June contained primarily small cladocerans (0.25-0.38 mm) of Chydorus sphaericus and Bosmina longirostris, two widespread and common species. One female individual of 43 mm TL contained an estimated 1210 C. sphaericus and 370 B. longirostris (ROM, unpublished data).

There have been no published studies on migration or size of home range in the Pugnose Shiner. It is likely that its small size and weak swimming ability limits its movement to small distances.

The Pugnose Shiner requires aquatic vegetation, which provides cover, food and breeding sites (Becker 1983). Based on studies in the aquarium, this species is timid and secretive and would therefore be less susceptible to entrapment gear (Becker 1983). Its habit of staying near cover and going into hiding at any motion or disturbance would presumably also reduce its susceptibility to predation in comparison to the Blackchin Shiner, Notropis heterodon, with which it is commonly associated. Although it has a very small mouth it can consume food items up to 2 mm long and twice the length of the mouth (Becker 1983).

No studies examining population size and trends have been conducted on the Canadian population of the Pugnose Shiner. However, recent collections of Pugnose Shiner in Canada at five localities indicate reproducing populations are established. It was first collected in Ontario in 1935 in the St. Lawrence River near Gananoque (Toner 1937). It was last recorded at this site in 1937, but was recently collected at a site east (1989; Royal Ontario Museum (ROM) 59737, 28 specimens) and a site west (1994; ROM 69271, two specimens) of the original site. In Lake Erie, it was collected at Point Pelee in 1940 and 1941, in Rondeau Bay in 1940 and 1963, and in Long Point Bay in 1947 and 1996. As all known capture localities were sampled in 1979 (Parker et al. 1987), and in the 1980's and 1990's (ROM unpublished data. data), it is probable that only the Long Point population still exists. The Canadian Lake St. Clair and Ausable Channel populations were first discovered in the early 1980's. In Lake St. Clair, small numbers of Pugnose Shiners were collected in St. Lukes Bay only in 1983, while it was collected in Mitchell Bay in 1983 and 1996. In 1999, 281 pugnose shiners were captured in the delta channels and freshwater coastal marshes of Walpole Island located at the north end of Lake St. Clair (ROM unpublished data). In 1983, 89 Pugnose Shiners were collected in the Old Ausable Channel, and 33 were collected in 1997. Therefore, it is probable that populations still exist in the St. Lawrence River, in Long Point Bay of Lake Erie, Lake St. Clair and the Old Ausable Channel.

The lack of Canadian records for 1947-1963 and 1963-1983 is likely the result of lack of large lake and river sampling, the small size of the species, and incorrect field identification.

Bailey (1959) documented the Pugnose Shiner from 89 sites in its entire range as follows: Minnesota (29), Michigan (27), Wisconsin (14), Ontario (5), Iowa (3), New York (3), Illinois (3), Ohio (2), Indiana (2) and North Dakota (1). More recent surveys have documented the Pugnose Shiner at new sites but most of these studies suggest that it was extirpated from some early sites (see Appendix 2). Declines have apparently occurred in Minnesota (Hatch et al. in press, Koel and Peterka 1998), New York (Carlson, 1998), Michigan (Latta 1998) and North Dakota (Koel and Peterka 1998). In Wisconsin, the number of occurrences of the Pugnose Shiner increased in later surveys (1974-1986) compared to early surveys (1900-1972). Although the sampling effort in the later surveys was higher, the frequency of occurrences at sampled sites remained unchanged at 0.6% (Fago 1992). However, it has not been recorded from several early sites and its trend in Wisconsin is uncertain (Becker 1983; J. Lyons, Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR), personal communication).

Pugnose Shiners were collected in Lake St. Clair in 2001 (ROM, unpublished data). In 2002, five of the six known locations of Pugnose Shiner were sampled. Pugnose Shiners were collected in Lake St. Clair (ROM, unpublished data) and the Old Ausable Channel [42 specimens, Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), unpublished data]. Despite intensive sampling at over 100 sites using a variety of gears, Pugnose Shiners were not collected at Point Pelee, nor were they collected using less intensive sampling in Long Point Bay and Rondeau Bay (DFO, unpublished data). Only the St. Lawrence location was not sampled in 2002.

Previous authors (e.g., Bailey 1959, Trautman 1981) attributed the decline of the Pugnose Shiner to turbidity and the removal of aquatic vegetation. Loss of habitat from shore development and destruction of native littoral-zone macrophyte communities probably caused the extirpation of the Pugnose Shiner from two lakes in southern Wisconsin (J. Lyons, WDNR, personal communication).

Turbidity and aquatic plant removal may also be contributing to its decline in Canada, but evidence from Point Pelee suggests that other factors may be involved. Parks on Point Pelee and Rondeau Bay that would presumably offer protection from habitat changes (Parker et al. 1987) have failed to prevent its decline or extirpation. Although Point Pelee experiences periodic turbidity in rough weather, we found water generally clear with an abundance of a variety of aquatic plants. In these areas, a factor that may have contributed to the decline of the Pugnose Shiner is an increase in the number and diversity of predators. There is evidence that minnow diversity and abundance decreases with an increase in numbers and diversity of littoral predators such as basses (Micropterus spp.) and pikes, (Esox spp.), (Whittier et al. 1997). Although the northern pike (Esox lucius) and grass pickerel (E. americanus vermiculatus) were known to occur at Point Pelee in the 1940s, potential predators such as largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), warmouth (Lepomis gulosus) and black crappie (Pomoxis nigromaculatus) were not recorded prior to 1958. However, the Pugnose Shiner was found in association with a wide variety of potential predators in 1999 at Walpole Island where it is relatively common (ROM unpublished data). These were frequently abundant and included bowfin (Amia calva), longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus), northern pike, grass pickerel, bullheads (Ameiurus spp), rock bass (Ambloplites rupestris), largemouth bass, black crappie and yellow perch (Perca flavescens).

Another factor that could have played a role in the decline or extirpation of the Pugnose Shiner at Point Pelee was an increase in competition for resources with species such as the Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus), juvenile Black Crappie, and Brook Silverside (Labidesthes sicculus). These species feed heavily on cladocerans and to some extent on plant material and did not appear in collections until 1958. However, Brook Silversides and juveniles of Bluegill and Black Crappie occurred together with Pugnose Shiners in 1999 collections at Walpole Island (ROM unpublished data)

Most of the Canadian habitat of this species has been affected by the introduced zebra mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) and quagga mussel (Dreissena bugensis). Their effect on the Pugnose Shiner is unknown, but it is possible that the increased water clarity and macrophyte proliferation associated with these invasive species may benefit this species.

Changes in the aquatic plant community on which the species depends could also have played a role. The extirpation of the Pugnose Shiner and seven other fish species in one lake in Wisconsin was associated with the introduction and explosive increase of Eurasian Water Milfoil, Myriophyllum spicatum (Lyons 1989). Eurasian Water Milfoil occurs at Point Pelee but it is not known with certainty when this species became established there. There is a record of Eurasian Water Milfoil from Point Pelee in 1961 but its identification has not been verified. In the St. Clair - Detroit River system it was first recorded in 1974 and by 1978 was the fourth most common submerged macrophyte (Schloesser and Manny 1984, M. Oldham, Ontario Natural Heritage Information Centre, personal communication).

Leslie and Timmins (2002) hypothesized that the isolated nature of preferred habitat in Lake Erie probably prevents connectivity of fragmented populations. This fragmentation likely prevents gene flow between between existing populations, and may inhibit (re)colonization of other suitable habitats.

Little is known of the ecological role of the rare Pugnose Shiner. Its strict habitat requirements make it a good indicator of environmental quality (Smith 1985).

Conservation ranks determined by the Association of Biodiversity Information are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Global, American and Canadian federal, and state and provincial ranks assigned by NatureServe (2002).

Global : G3

USA : N3

Canada : N2N3

State/Provincial : Illinois (S1), Indiana (S1), Iowa (S1), Michigan (S3), Minnesota (S3), New York (S1), North Dakota (S1), Ohio (SX), Wisconsin (S2S3), Ontario (S2)

The original COSEWIC report determined the status to be Rare (Parker et al. 1987). In 1997, it was officially listed as “Threatened” in Ontario, which is the only province where it is found (A. Dextrase, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, personal communication). Although, no specific current legal protection exists for the Pugnose Shiner in Canada, the Threatened designation recommended in this report will afford protection to the species and its habitat under the proposed Canada Species at Risk Act.

The species and/or its habitat may also be protected by the Canada Environmental Assessment Act, Canada Environmental Protection Act, Canada Fisheries Act, Canada Water Act, Canada Wildlife Act, Ontario Environmental Protection Act, Ontario Environmental Assessment Act, Ontario Planning Act and Ontario Water Resources Act. The Ontario Conservation Land Tax Incentive Program may indirectly conserve the habitat of this species where it occurs in provincially significant wetlands such as those on the east shore of Lake St. Clair (D. Hector, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, personal communication).

Johnson (1987) listed the Pugnose Shiner as protected in Iowa, Illinois, New York and of Special Concern in North Dakota, Wisconsin and Ontario. In Minnesota, it is designated as Special Concern (Hatch et al. in press). In Wisconsin, it was downlisted to Watch Status (Fago 1992).

The Pugnose Shiner is at its northeastern range limit in Canada. It was recently found in the Old Ausable Channel, Lake St. Clair, Lake Erie and the St. Lawrence River. Although additional sampling is required to determine the stability, size and range of the population, it appears that reproducing populations are still present in limited areas of these waters. As it is not known why this species is declining in Canada, it is difficult to determine how to protect this species, or if populations will persist if its habitat is not significantly altered.

The Pugnose Shiner was recorded from only six areas in Canada. It is now found at only four of these. It is rare and has experienced decline in many areas throughout its entire range. Therefore, it is recommended that its status be upgraded from Vulnerable to Threatened.

Notropis anogenus

Pugnose Shiner Méné Camus

Extent of occurrence < 30,000 km2

Area of occupancy: < 20 km2

Habitat trend : decline in extent and quality of habitat

Number of mature (capable of reproduction) individuals in Canadian Population: Unknown

Generation Time: 2 years

Population trend: declining

Rate of decline: Unknown

Number of populations within Canada: 4

Is population fragmented? Yes

Number of individuals in each sub-population : Unknown

Number of extant locations: 4

Number of historic locations from which the species has been extirpated : 2

Does the species undergo fluctuations? No

Increasing turbidity and removal of aquatic vegetation resulting from shore development and agriculture and urban development.

Changes in the aquatic plant community on which the species depends has been limiting in some areas.

Does the species exist elsewhere? Yes, but neighboring U.S. populations are also declining

Is immigration known or possible? Unlikely

Is suitable habitat available for immigrants : Yes, but in Decline

Would immigrants survive in Canada? Yes

Funding for fieldwork was provided by the World Wildlife Fund, and the Ministry of Natural Resources. Funding for the status report was also provided by the Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada. The Royal Ontario Museum provided logistic and technical support. Patricia MacCulloch identified stomach contents. Marty Rouse, Karen Ditz, Martin Ciuk, David Boehm, Leona Crowe, Jennifer Dodge, Kristina Banks, Robert Dalziel, Don Stacey, Gary Mouland, William Ramshaw, Randy Guppy, Mathis Natvik and Stan Powell assisted with field work. Douglas Carlson, Don Sutherland, Douglas Nelson, Jay Hatch, John Lyons, Lori Sargent and Mike Oldham provided useful information. The Geographical Information Systems (GIS) software (ArcView 2.0) used to create Figures 2 and 3 was donated by ESRI and the Ontario base map used in Figure 3 was courtesy of the Geomatics Unit of Environment Canada.

Bailey, R.M. 1959. Distribution of the American cyprinid fish Notropis anogenus. Copeia 1959 (2):119-123.

Becker, G.C. 1983. Fishes of Wisconsin. University of Wisconsin Press, Madison, Wisconsin.

Carlson, D.M. 1998. Species accounts for the rare fishes of New York. New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Division of Fish, Wildlife and Marine Resources, Watertown, New York.

Fago, D. 1992. Distribution and relative abundance of fishes in Wisconsin. VIII Summary Report. Technical Bulletin No. 175. Department of Natural Resources, Madison, Wisconsin.

Forbes, S.A. 1885. Description of new Illinois fishes. Bulletin of the Illinois State Laboratory of Natural History 2(2):135-139.

Hatch, J.T., D.P. Siems, K. Schmidt, J.C. Underhill, R.A. Bellig, and R.A. Baker. in press. A new distributional checklist of Minnesota fishes, with comments on classification, historical occurrence and conservation status. Journal of Minnesota Academy of Sciences.

Johnson, J.E. 1987. Protected fishes of United States and Canada. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland.

Koel, T.M., and J.J. Peterka. 1998. Stream fishes of the Red River of the North basin, United States: A comprehensive review. Canadian Field-Naturalist 112(4):631-646.

Latta, W.C. 1998. Status of some of the endangered, threatened, special-concern and rare fishes of Michigan in 1998. Report prepared for the Natural Heritage Program, Wildlife Division, Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

Leslie, J.K., and C.A. Timmins. 2002. Description of age 0 juvenile pugnose minnow Opsopoedus emiliae (Hay) and pugnose shiner Notropis anogenus Forbes in Ontario. Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 2397.

Lyons, J. 1989. Changes in the abundance of small littoral-zone fishes in Lake Mendota, Wisconsin. Canadian Journal of Zoology 67:2910-2916.

NatureServe 2002. The Association for Biodiversity Information (ABI). NatureServe Explorer, an online encyclopedia of life website: http://www.natureserveexplorer.org/ (Accessed 4 April 2002).

Page, L.M., and B.M. Burr. 1991. A field guide to freshwater fishes. Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, Massachusetts.

Parker, B., P. McKee, and R.R. Campbell. 1987. Status of the pugnose shiner, Notropis anogenus, in Canada. Canadian Field-Naturalist 101:203-207.

Robins, R.C., R. M. Bailey, C.E. Bond, J.R. Brooker, E.A. Lachner, R.N. Lea, and W.B. Scott. 1991. Common and scientific names of fishes from the United States and Canada. American Fisheries Society Special Publication 20. Bethesda, Maryland. 183 pp.

Schloesser, D.W., and B.A. Manny. 1984. Distribution of Eurasian Milfoil, Myriophyllum spicatum, in the St. Clair-Detroit River system in 1978. Journal of Great Lakes Research 10(3):322-326.

Scott, W.B., and E.J. Crossman. 1973. Freshwater Fishes of Canada. Fisheries Research Board of Canada Bulletin 184. 966 pages.

Smith, C. L. 1985. The inland fishes of New York State. N.Y. State Dept. of Environmental Conservation.

Toner, G.C. 1937. Preliminary studies of the fishes of eastern Ontario. Bulletin Eastern Ontario Fish and Game Protective Association, supplement 2:1-24.

Trautman, M.B. 1981. The fishes of Ohio. Ohio State University Press. Columbus, Ohio.

Whittier, T.R., D.B. Halliwell, and S.G. Paulsen. 1997. Cyprinid distributions in northeast USA lakes: evidence of regional-scale minnow biodiversity losses. Canadian Journal of fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 54(7):1593-1607

Erling Holm is Assistant Curator at the Centre for Biodiversity and Conservation Biology of the Royal Ontario Museum where he manages a collection of preserved fishes consisting of around 1,000,000 specimens, He has a BSc from the University of Toronto and worked for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources prior to coming to the Museum in 1977. He has been involved in fieldwork in Ontario, Quebec, Peru and Guyana. His interests include the taxonomy and ecology of Canadian and south American freshwater fishes and Indo-Pacific marine fishes.

Nicholas Mandrak holds a Ph. D. from the University of Toronto on the biogeographical patterns of freshwater fishes in relation to historical and environmental process in Ontario lakes and streams. He is quite familiar with COSEWIC and has co-authored seven status reports for fish species. Both his teaching and research efforts have centred on biogeography, biodiversity and conservation of freshwater fishes. Current research interests include development of a national database on freshwater fishes, development of a rare and endangered fish data base for the Great lakes, examination of the population ecology of species such as the shortjaw cisco, and silver chub and the impact of introduced species on native fish communities in south-western Ontario. He has taught at the University of Toronto, Fort Hays State University, Trent University and is currently an assistant professor at Youngstown State University. He is a member of the American Fisheries Society and has been the recipient of many honours and awards, most recently the Outstanding Scholarship Award of Fort Hays State University.