River darter (Percina shumardi), various populations, COSEWIC assessment and status report 2016: chapter 1

Document information

COSEWIC

Committee on the Status

of Endangered Wildlife

in Canada

COSEPAC

Comité sur la situation

des espèces en péril

au Canada

COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows:

COSEWIC. 2016. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the River Darter Percina shumardi, Saskatchewan - Nelson River populations, Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay populations and Great Lakes-Upper St. Lawrence populations,in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xix + 53 pp.

Previous report(s):

Dalton, Ken W. 1989. COSEWIC status report on the River Darter Percina shumardi in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Widlife in Canada. Ottawa. 12 pp.

Production note:

COSEWIC would like to acknowledge Doug Watkinson, Nick Mandrak and Thomas Pratt for writing the status report on the River Darter (Percina shumardi) in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by John Post, Co-chair of the COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Subcommittee.

For additional copies contact:

COSEWIC Secretariat

c/o Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment and Climate Change Canada

Ottawa, ON

K1A 0H3

Tel.: 819-938-4125

Fax: 819-938-3984

E-mail: COSEWIC E-mail

Website: COSEWIC

Également disponible en français sous le titre Ếvaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Dard de rivière (Percina shumardi), populations de la rivière Saskatchewan et du fleuve Nelson, populations du sud de la baie d'Hudson et de la baie James et populations des Grands Lacs et du haut Saint-Laurent, au Canada.

Cover illustration/photo:

River Darter, Percina shumardi, collected from the Bird River, Manitoba. Photo: D.A. Watkinson.

COSEWIC assessment summary

Assessment summary - May 2016

- Common name

- River Darter - Saskatchewan - Nelson River populations

- Scientific name

- Percina shumardi

- Status

- Not at Risk

- Reason for designation

- This is a broadly distributed species that is inferred to be stable in abundance and distribution. Potential threats include water management practices and urban and agricultural effluents but these are assessed as having a low overall impact.

- Occurrence

- Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario

- Status history

- The species was considered a single unit and designated Not at Risk in April 1989. When the species was split into three separate units in April 2016, the "Saskatchewan - Nelson River populations" unit was designated Not at Risk.

Assessment summary - May 2016

- Common name

- River Darter - Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay populations

- Scientific name

- Percina shumardi

- Status

- Not at Risk

- Reason for designation

- This is a broadly distributed, but relatively uncommon, species that is inferred to be stable in abundance and distribution. Potential threats related to water management practices are assessed as low overall.

- Occurrence

- Manitoba, Ontario

- Status history

- The species was considered a single unit and designated Not at Risk in April 1989. When the species was split into three separate units in April 2016, the "Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay populations" unit was designated Not at Risk.

Assessment summary - May 2016

- Common name

- River Darter - Great Lakes-Upper St. Lawrence populations

- Scientific name

- Percina shumardi

- Status

- Endangered

- Reason for designation

- This is a small-bodied species that inhabits medium to large rivers and shorelines of larger lakes. It has a very restricted distribution, occurs at few locations, and is exposed to high risk of threats from shoreline hardening, exotic species such as Round Goby, dams and water management, dredging, nutrients and effluents from urban waste, spills, and agriculture.

- Occurrence

- Ontario

- Status history

- The species was considered a single unit and designated Not at Risk in April 1989. When the species was split into three separate units in April 2016, the "Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence populations" unit was designated Endangered.

COSEWIC executive summary

River darter

Percina shumardi

Saskatchewan – Nelson River populations

Southern Hudson Bay – James Bay populations

Great Lakes-Upper St. Lawrence populations

Wildlife species description and significance

River Darter (Percina shumardi) is a small, elongated fish that can be distinguished from other darters by scaled cheeks and operculum and a well-marked dark spot on the upper anterior and lower posterior corners of the spiny dorsal fin. The breast is scaleless, and there are 46-62 lateral line scales. The anal fin of males is enlarged reaching almost to the caudal fin.

River Darter is a little known species and has no direct economic importance; however, it can be numerous in larger rivers and near the shore of larger lakes in Manitoba and northwestern Ontario and likely plays an important ecological role where abundant. It is ranked as Critically Imperilled in portions of its distribution in the United States.

Distribution

River Darter has one of the largest latitudinal distributions for darters, extending north from the Texas coast on the Gulf of Mexico to Nelson River near Hudson Bay in northern Manitoba. It has a continuous distribution through most of Manitoba into northwestern Ontario in the Saskatchewan-Nelson drainage as well as the Hudson Bay drainage west of James Bay. A single specimen has been collected from the Saskatchewan River in Saskatchewan. The species is also found in Lake St. Clair and its tributaries in Ontario. Therefore the River Darter is assessed as three separate designatable units, aligning with the National Freshwater Biogeographic Zones.

Habitat

River Darter is mainly found in medium to large rivers or shorelines of larger lakes that typically have moderate currents and deeper water. River Darter is most abundant on gravel and cobble substrates and is tolerant of turbid waters.

Biology

Individuals can mature as early as age 1 and can live to age 4. In Canada, spawning occurs in May to early July, predominantly in rivers; however, ripe individuals are collected in lakes suggesting spawning may occur in both lentic and lotic environments. During spawning, eggs are buried in sand or gravel and are unattended. Post-hatch larvae swim almost continuously near the water surface suggesting downstream dispersal may occur in rivers as the surface-water velocities would typically be greater than the larval swimming speed.

River Darter feeds primarily during daylight hours and consumes dipterans, trichopterans, ephemeropterans, crustaceans, and gastropods, with dominant prey items varying between sites and seasons.

Population size and trends

River Darter has been collected at a number of sites in Manitoba and northwestern Ontario, but in low abundance. Surveys made in the last decade using more appropriate gear to sample large rivers and lakes have collected considerably more specimens but changes and fluctuations in population size and density of River Darter cannot be estimated based on available information in these areas. In southern Ontario intensive sampling has identified substantial declines in ranges leading to inferences of population declines.

Threats and limiting factors

Knowledge of threats and their impacts on River Darter populations is limited, as there is little information available for threat-specific, cause-and-effect relationships. Limiting factors have not been identified for this species. Physical alteration/modification of habitat from exotic species, shoreline hardening, industrial and agricultural effluents, nutrients, sedimentation, dams, and dredging may possibly impact River Darter in Canada.

Protection, status, and ranks

In Canada, River Darter has no specific protection, but incidental protection is provided by the federal Fisheries Act as its entire range in Canada overlaps with commercial, recreational or Aboriginal species.

The River Darter is not protected under the United States Endangered Species Act.

Technical summary - DU1

- Scientific name:

- Percina shumardi

- English name:

- River Darter - Saskatchewan - Nelson River populations

- French name:

- Dard de rivière - Populations de la rivière Saskatchewan et du fleuve Nelson

- Range of occurrence in Canada:

- Nelson River and its tributaries in Manitoba, Ontario and single site on the Saskatchewan River, Saskatchewan.

Demographic Information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] continuing decline in number of mature individuals? | No |

| Estimated percent of continuing decline in total number of mature individuals within [5 years or 2 generations] | Unknown |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the last [10 years, or 3 generations]. | Unknown |

| [Projected or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the next [10 years, or 3 generations]. | Unknown |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over any [10 years, or 3 generations] period, over a time period including both the past and the future. | Unknown |

Are the causes of the decline

|

|

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals? | Unknown |

Extent and Occupancy Information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Estimated extent of occurrence All years | >512,123 km2 |

| Index of area of occupancy (IAO) (Always report 2x2 grid value). All years Discrete-748 km2 Continuous- >2000 km2 |

>2,000 km2 |

Is the population "severely fragmented" ie. is >50% of its total area of occupancy in habitat patches that are

|

|

| Number of "locations ? (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.) (use plausible range to reflect uncertainty if appropriate) |

67 to 100. The number of known locations based on collection records is 67. Many other unsampled locations likely exist in the remote portions of the species' range suggesting that the best estimate is likely >100. |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in index of area of occupancy? | No |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of subpopulations? | No |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of "locations" (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.)? |

No |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in [area, extent and/or quality] of habitat? | Yes |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of subpopulations? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of "locations"? (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.)? |

No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in index of area of occupancy? | No |

Number of Mature Individuals (in each subpopulation)

| Subpopulations (give plausible ranges) | N Mature Individuals |

|---|---|

| All subpopulation in this DU | Unknown for all |

| Total | - |

Quantitative Analysis

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Probability of extinction in the wild is at least [20% within 20 years or 5 generations, or 10% within 100 years]. | No quantitative data are available |

Threats (actual or imminent, to populations or habitats, from highest impact to least)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Physical alteration/modification of habitat from dams and changes to the hydrograph as well as nutrient and effluents may possibility impact River Darter in DU1 (Appendix 1). | A threat calculator was completed by Nicholas Mandrak, Thomas Pratt, Dwayne Lepitzki, Scott Reid, Margaret Docker, Angele Cyr, John Post and Douglas Watkinson. |

Rescue Effect (immigration from outside Canada)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status of outside population(s) most likely to provide immigrants to Canada. | Minnesota, North Dakota |

| Is immigration known or possible? | Not known, but there are no barriers to fish movement from the Red River drainage in North Dakota or Minnesota or the Rainy River drainages in Minnesota. |

| Would immigrants be adapted to survive in Canada? | Yes |

| Is there sufficient habitat for immigrants in Canada? | Yes |

| Are conditions deteriorating in Canada ? See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Yes. Southern portion of the DU has higher nutrient inputs. |

| Are conditions for the source population deteriorating ? See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

No |

| Is the Canadian population considered to be a sink ? See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

No |

| Is rescue from outside populations likely? | Yes |

Data Sensitive Species

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Is this a data-sensitive species? | No |

Status History

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| COSEWIC: The species was considered a single unit and designated Not at Risk in April 1989. | When the species was split into three separate units in April 2016, the "Saskatchewan - Nelson River populations" unit was designated Not at Risk. |

Status and Reasons for Designation

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status | Not at Risk |

| Alpha-numeric codes | Not Applicable |

| Reasons for designation | This is a broadly distributed species that is inferred to be stable in abundance and distribution. Potential threats include water management practices and urban and agricultural effluents but these are assessed as having a low overall impact. |

Applicability of Criteria

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Criterion A (Decline in Total Number of Mature Individuals) | Not applicable. Information on population sizes is not available. |

| Criterion B (Small Distribution Range and Decline or Fluctuation) | Not applicable. |

| Criterion C (Small and Declining Number of Mature Individuals) | Not applicable. Information on population sizes is not available. |

| Criterion D (Very Small or Restricted Population) | Not applicable. Information on population sizes is not available. |

| Criterion E (Quantitative Analysis) | Quantitative analyses have not been completed. |

Technical summary - DU2

- Scientific name:

- Percina shumardi

- English name:

- River Darter - Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay populations

- French name:

- Dard de rivière - Populations du sud de la baie d'Hudson et de la baie James

- Range of occurrence in Canada:

- Attawapiskat, Albany, Severn and Winisk river watersheds in Manitoba, and Ontario.

Demographic Information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Generation time (usually average age of parents in the population; indicate if another method of estimating generation time indicated in the IUCN guidelines(2011) is being used) | 2 years |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] continuing decline in number of mature individuals? | No |

| Estimated percent of continuing decline in total number of mature individuals within [5 years or 2 generations] | Unknown |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the last [10 years, or 3 generations]. | Unknown |

| [Projected or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the next [10 years, or 3 generations]. | Unknown |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over any [10 years, or 3 generations] period, over a time period including both the past and the future. | Unknown |

Are the causes of the decline

|

|

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals? | Unknown |

Extent and Occupancy Information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Estimated extent of occurrence All years | >64,660 km2 |

Index of area of occupancy (IAO) All years |

>2,000 km2 |

Is the population "severely fragmented" ie. is >50% of its total area of occupancy in habitat patches that are

|

|

| Number of "locations" (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.) (use plausible range to reflect uncertainty if appropriate) |

11 to >50. The number of known locations based on collection records is 11. Many other unsampled locations likely exist in the remote portions of the species' range suggesting that the best estimate is likely >50. |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in index of area of occupancy? | No |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of subpopulations? | No |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of "locations" (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.)? |

No |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in [area, extent and/or quality] of habitat? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of subpopulations? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of "locations? (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.)? |

No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in index of area of occupancy? | No |

Number of Mature Individuals (in each subpopulation)

| Subpopulations (give plausible ranges) | N Mature Individuals |

|---|---|

| All subpopulation in this DU | Unknown |

| Total | - |

Quantitative Analysis

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Probability of extinction in the wild is at least [20% within 20 years or 5 generations, or 10% within 100 years]. | No quantitative data are available |

Threats (actual or imminent, to populations or habitats, from highest impact to least)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Physical alteration/modification of habitat from dams and changes to the hydrograph may possibility impact River Darter in DU2 (Appendix 2). | A threat calculator was completed by Nicholas Mandrak, Thomas Pratt, Dwayne Lepitzki, Scott Reid, Margaret Docker, Angele Cyr, John Post and Douglas Watkinson. |

Rescue Effect (immigration from outside Canada)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status of outside population(s) most likely to provide immigrants to Canada. | Not Applicable |

| Is immigration known or possible? | Not Possible |

| Would immigrants be adapted to survive in Canada? | Not Applicable |

| Is there sufficient habitat for immigrants in Canada? | Not Applicable |

| Are conditions deteriorating in Canada? See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Not Applicable |

| Are conditions for the source population deteriorating? See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Not Applicable |

| Is the Canadian population considered to be a sink? See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Not Applicable |

| Is rescue from outside populations likely? | Not Possible |

Data Sensitive Species

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Is this a data-sensitive species? | No |

Status History

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| COSEWIC: The species was considered a single unit and designated Not at Risk in April 1989. | When the species was split into three separate units in April 2016, the "Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay populations" unit was designated Not at Risk. |

Status and Reasons for Designation

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status | Not at Risk |

| Alpha-numeric codes: | Not Applicable |

| Reasons for designation: | This is a broadly distributed, but relatively uncommon, species that is inferred to be stable in abundance and distribution. Potential threats related to water management practices are assessed as low overall. |

Applicability of Criteria

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Criterion A (Decline in Total Number of Mature Individuals): | Not applicable. Information on population sizes is not available. |

| Criterion B (Small Distribution Range and Decline or Fluctuation): | Not applicable. |

| Criterion C (Small and Declining Number of Mature Individuals): | Not applicable. Information on population sizes is not available. |

| Criterion D (Very Small or Restricted Population): | Not applicable. Information on population sizes is not available. |

| Criterion E (Quantitative Analysis): | Quantitative analyses have not been completed. |

Technical summary - DU3

- Scientific name:

- Percina shumardi

- English name:

- River Darter - Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence populations

- French name:

- Dard de rivière - Populations des Grands Lacs et du haut Saint-Laurent

- Range of occurrence in Canada:

- Lake St. Clair and tributaries, Ontario

Demographic Information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Generation time (usually average age of parents in the population; indicate if another method of estimating generation time indicated in the IUCN guidelines(2011) is being used) | 2 years |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] continuing decline in number of mature individuals? | Yes, inferred |

| Estimated percent of continuing decline in total number of mature individuals within [5 years or 2 generations] | Unknown |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the last [10 years, or 3 generations]. | Unknown |

| [Projected or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over the next [10 years, or 3 generations]. | Unknown |

| [Observed, estimated, inferred, or suspected] percent [reduction or increase] in total number of mature individuals over any [10 years, or 3 generations] period, over a time period including both the past and the future. | Unknown |

Are the causes of the decline

|

|

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals? | Unknown |

Extent and Occupancy Information

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Estimated extent of occurrence Pre-2005 2,244 km2 2005-2014 907 km2 |

907 km2 |

Index of area of occupancy (IAO) Pre-2005 |

336 km2 |

| Is the population "severely fragmented" i.e. is >50% of its total area of occupancy in habitat patches that are (a) smaller than would be required to support a viable population, and (b) separated from other habitat patches by a distance larger than the species can be expected to disperse? | No |

| Number of "locations" (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.) (use plausible range to reflect uncertainty if appropriate) North Sydenham River [likely extirpated] East Sydenham River Thames River Lake St. Clair |

3 |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in extent of occurrence? | Yes |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in index of area of occupancy? | Yes |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of subpopulations? | Yes. No recent records in the North Sydenham River or Jeanette's Creek, a tributary to the Thames River |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in number of "locations" (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.)? |

Yes. No recent records in the North Sydenham River |

| Is there an [observed, inferred, or projected] decline in [area, extent and/or quality] of habitat? | Yes, inferred |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of subpopulations? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in number of "locations"? (Note: See Definitions and Abbreviations on COSEWIC website and IUCN (Feb 2014) for more information on this term.)? |

No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in extent of occurrence? | No |

| Are there extreme fluctuations in index of area of occupancy? | No |

Number of Mature Individuals (in each subpopulation)

| Subpopulations (give plausible ranges) | N Mature Individuals |

|---|---|

| - | unknown |

| Total | - |

Quantitative Analysis

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Probability of extinction in the wild is at least [20% within 20 years or 5 generations, or 10% within 100 years]. | No quantitative data are available |

Threats (actual or imminent, to populations or habitats, from highest impact to least)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| The threats to River Darter may include exotic species such as Round Goby, physical alteration/modification of habitat from shoreline hardening and dredging, nutrients and effluents from urban waste, agricultural runoff and spills, sedimentation, dams and changes to the hydrograph in DU3 (Appendix 3). | A threat calculator was completed by Nicholas Mandrak, Thomas Pratt, Dwayne Lepitzki, Scott Reid, Margaret Docker, Angele Cyr, John Post and Douglas Watkinson. |

Rescue effect (immigration from outside Canada)

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status of outside population(s) most likely to provide immigrants to Canada. | Michigan, Ohio |

| Is immigration known or possible? | Possible. From the USA side of Lake St. Clair and Lake Erie, but not known. |

| Would immigrants be adapted to survive in Canada? | Yes |

| Is there sufficient habitat for immigrants in Canada? | Yes |

| Are conditions deteriorating in Canada? See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Yes |

| Are conditions for the source population deteriorating See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

Yes |

| Is the Canadian population considered to be a sink See Table 3 ( Guidelines for modifying status assessment based on rescue effect) |

No |

| Is rescue from outside populations likely? | Unknown if it is within the natural dispersal ability of the species |

Data sensitive species

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Is this a data-sensitive species? | No |

Status history

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| COSEWIC: The species was considered a single unit and designated Not at Risk in April 1989. | When the species was split into three separate units in April 2016, the "Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence populations" unit was designated Endangered. |

Status and reasons for designation

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Status | Endangered |

| Alpha-numeric codes | B1ab(i,ii,iii,iv)+2ab(i,ii,iii,iv) |

| Reasons for designation | This is a small-bodied species that inhabits medium to large rivers and shorelines of larger lakes. It has a very restricted distribution, occurs at few locations, and is exposed to high risk of threats from shoreline hardening, exotic species such as Round Goby, dams and water management, dredging, nutrients and effluents from urban waste, spills, and agriculture. |

Applicability of criteria

| Summary items | Information |

|---|---|

| Criterion A (Decline in Total Number of Mature Individuals): | Not applicable. Information on population sizes is not available. |

| Criterion B (Small Distribution Range and Decline or Fluctuation): | Meets Endangered B1ab(i,ii,iii,iv)+2ab(i,ii,iii,iv) with a small EOO (907 km2), small and continuing decline in IAO (336 km2), few locations (3) which have declined, and a continuing decline in habitat quality. |

| Criterion C (Small and Declining Number of Mature Individuals): | Not applicable. Information on population sizes is not available. |

| Criterion D (Very Small or Restricted Population): | Not applicable. Information on population sizes is not available. |

| Criterion E (Quantitative Analysis): | Quantitative analyses have not been completed. |

Preface

No directed research has been published on the biology of River Darter since the last COSEWIC report in 1989 in which the species was assessed as a single designatable unit as Not at Risk. However, one important Canadian reference, a master's thesis that deals with reproduction and feeding (Balesic 1971) was omitted from the original report. In Manitoba, a broader distribution of the species has been documented in the Assiniboine River and Lake Winnipegosis watersheds since 1990, likely as a result of increased sampling effort with more appropriate gear. A single specimen was collected in Saskatchewan in 1990 (ROM 60976) in the Saskatchewan River. This represents the only known occurrence in this province. Little sampling has been conducted since the last COSEWIC assessment in more remote waterbodies, River Darter was known to occur in northern Manitoba and northwestern Ontario. River Darter continues to be rare in southern Ontario, despite significant sampling. There has been insufficient sampling to determine trends in abundance in Canada.

COSEWIC history

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) was created in 1977 as a result of a recommendation at the Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference held in 1976. It arose from the need for a single, official, scientifically sound, national listing of wildlife species at risk. In 1978, COSEWIC designated its first species and produced its first list of Canadian species at risk. Species designated at meetings of the full committee are added to the list. On June 5, 2003, the Species at Risk Act (SARA) was proclaimed. SARA establishes COSEWIC as an advisory body ensuring that species will continue to be assessed under a rigorous and independent scientific process.

COSEWIC mandate

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assesses the national status of wild species, subspecies, varieties, or other designatable units that are considered to be at risk in Canada. Designations are made on native species for the following taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, arthropods, molluscs, vascular plants, mosses, and lichens.

COSEWIC membership

COSEWIC comprises members from each provincial and territorial government wildlife agency, four federal entities (Canadian Wildlife Service, Parks Canada Agency, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the Federal Biodiversity Information Partnership, chaired by the Canadian museum of Nature), three non-government science members and the co-chairs of the species specialist subcommittees and the Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge subcommittee. The Committee meets to consider status reports on candidate species.

Definitions (2016)

- Wildlife Species

- A species, subspecies, variety, or geographically or genetically distinct population of animal, plant or other organism, other than a bacterium or virus, that is wild by nature and is either native to Canada or has extended its range into Canada without human intervention and has been present in Canada for at least 50 years.

- Extinct (X)

- A wildlife species that no longer exists.

- Extirpated (XT)

- A wildlife species no longer existing in the wild in Canada, but occurring elsewhere.

- Endangered (E)

- A wildlife species facing imminent extirpation or extinction.

- Threatened (T)

- A wildlife species likely to become endangered if limiting factors are not reversed.

-

Special Concern (SC)

(Note: Formerly described as "Vulnerable" from 1990 to 1999, or "Rare" prior to 1990.) - A wildlife species that may become a threatened or an endangered species because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

-

Not at Risk (NAR)

(Note: Formerly described as "Not In Any Category", or "No Designation Required.") - A wildlife species that has been evaluated and found to be not at risk of extinction given the current circumstances.

-

Data Deficient (DD)

(Note: Formerly described as "Indeterminate" from 1994 to 1999 or "ISIBD" [insufficient scientific information on which to base a designation] prior to 1994. Definition of the [DD] category revised in 2006.) - A category that applies when the available information is insufficient (a) to resolve a species' eligibility for assessment or (b) to permit an assessment of the species' risk of extinction.

The Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment and Climate Change Canada, provides full administrative and financial support to the COSEWIC Secretariat.

Wildlife species description and significance

Name and classification

Class Actinopterygii

Order Perciformes

Family Percidae

Subfamily Etheostomatinae

Species Percina shumardi (Girard, 1859)

English Common Name River Darter (Page et al. 2013)

French Common Name Dard de rivière (Page et al. 2013)

The River Darter, Percina shumardi (Girard, 1859) is one of 45 species of the genus Percina in the family Percidae (Page et al. 2013).

Morphological description

River Darter is a small, elongated fish (Figure 1) that grows to a maximum of 94 mm total length in Canada (Watkinson unpubl.). The species has a short, rounded snout and a moderately sized, terminal mouth (Scott and Crossman 1973; Stewart and Watkinson 2004) as well as large eyes that are close together and high on the head (Kuehne and Barbour 1983). The spiny and soft dorsal fins are separated. The River Darter can be distinguished from the Channel Darter (Percina copelandi) and Blackside Darter (Percina maculata) with a well-marked dark spot on the upper anterior and lower posterior corners of the spiny dorsal fin (Stewart and Watkinson 2004; Holm et al. 2009). Scales are ctenoid; there are 46-62 lateral line scales (Holm et al. 2009). Scales are also usually found on the cheeks and operculum, while the breast is usually scaleless (Scott and Crossman 1973; Becker 1983). The colouration of the River Darter varies from light brown to dark olive with seven to eight faint saddles on the back and 8 to 15 indistinct lateral blotches or short vertical bars on the sides (Kuehne and Barbour 1983; Holm et al. 2009). Distinct suborbital bars drop from the eyes, and small, well-defined, caudal spots may be present (Scott and Crossman 1973). Colouration on breeding males is generally darker (Scott and Crossman 1973; Smith 1979) and they may develop nuptial tubercles on the caudal, anal and pelvic fins, as well as on the vent and on the head along the infraorbital and preopercular mandibular canals (Kuehne and Barbour 1983). The anal fin of spawning males is enlarged reaching almost to the caudal fin (Figure 1; Scott and Crossman 1973).

Long description for Figure 1

Photo of the River Darter, a small, elongated fish that can be distinguished from other darters by scaled cheeks and operculum and a well-marked dark spot on the upper anterior and lower posterior corners of the spiny dorsal fin. The breast is scaleless, and there are 46 to 62 lateral line scales.

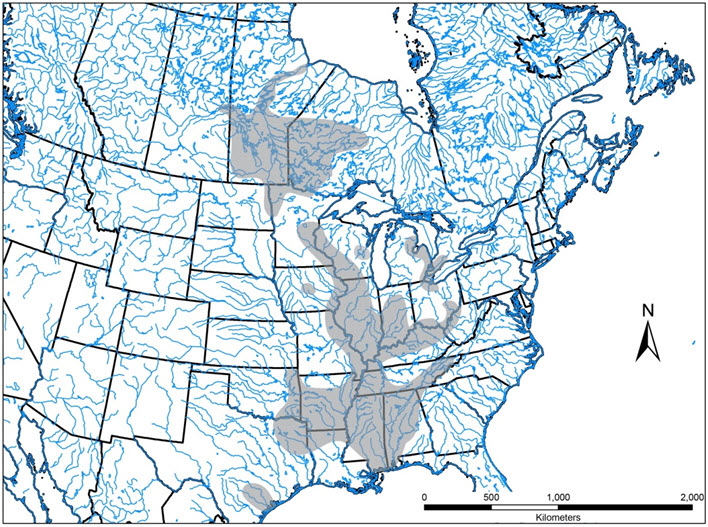

Long description for Figure 2

Map of the global distribution of the River Darter. The range extends north from the Texas coast on the Gulf of Mexico to the Nelson River near Hudson Bay in northern Manitoba. It has a continuous distribution through most of Manitoba into northwestern Ontario in the Saskatchewan-Nelson drainage as well as the Hudson Bay drainage west of James Bay. A single specimen has been collected from the Saskatchewan River in Saskatchewan. The species is also found in Lake St. Clair and its tributaries in Ontario.

Population spatial structure and variability

The River Darter is widely distributed across two National Freshwater Biogeographical Zones (NFBZ), the Saskatchewan - Nelson River and the Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay, and has a restricted distribution in the Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence. Movement of fish between these NFBZ is impossible with the exception of the Albany River in the Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay NFBZ, where a portion of the outflow of Lake St. Joseph has been diverted into the Winnipeg River drainage via Lac Seul, part of the English River system since 1957, providing downstream passage into the Saskatchewan - Nelson River drainage.

A preliminary population and genetic study was recently conducted on River Darter (DFO 2015). Tissue samples from >200 River Darter, originating from 16 populations distributed across the three NFBZ, were obtained from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) and the Royal Ontario museum. Individuals were sequenced at two mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) regions; cytochrome c oxidase I (CO1) (525 base pairs) and cytochrome-b (Cyt b ) (926 base pairs). The CO1 results were useful for species identification. CO1 identified 24 haplotypes and confirmed the species identification for all specimens (n = 230) with 93% of the individuals sharing a single haplotype. Cyt b was more informative for looking at broad-scale population structure. Twenty-six cytochrome-b haplotypes were identified from 143 individuals sequenced and 45% of all individuals shared a single haplotype present across all three zones. Six haplotypes were unique to the Saskatchewan - Nelson River NFBZ and two unique haplotypes were found in one of the two Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay populations (Badesdawa Lake). The other population, Lake St. Joseph, shared a common haplotype with the Saskatchewan - Nelson River populations, suggesting gene flow has occurred between the biogeographic zones. By definition, wildlife species (DUs) are discrete and significant and, therefore, can't rescue one another; however, water is diverted from the Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay Biogeographic Zone from Lake St. Joseph into the Saskatchewan - Nelson River NFBZ. A control dam on the Root River that allows water to move into is impassible to upstream movement, but has the potential to allow River Darter from Lake St. Joseph to move into Lac Seul, and the Saskatchewan - Nelson River NFBZ. There is no understanding of the magnitude of the gene flow. Two of three individuals from the Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence Biogeographic Zone shared a unique haplotype, supporting the genetic distinctiveness of this biogeographic zone. There is evidence of partitioning of haplotype diversity across the Saskatchewan - Nelson River and Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence NFBZ. Sequencing more individuals from additional waterbodies in Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay and additional fish in the Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence is required to confirm these apparent differences in haplotypes across biogeographic zones (DFO 2015).!

Designatable units

Based on the COSEWIC National Freshwater Biogeographic Zone classification, populations of River Darter are found in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and northwestern Ontario in the Saskatchewan - Nelson River Biogeographic Zone, DU1, and in northern Ontario in the Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay Biogeographic Zone, DU2. In Ontario, there is also a population in the Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence NFBZ, DU3. The genetic evidence supports a level of differentiation between DU3 and the other two DUs. Until additional genetic samples are analyzed to clarify the relationships between DU1 and DU2, three designatable units based on separate NFBZ are recommended for the species.

Special significance

River Darter distribution spans a large climatic and latitudinal range. The three DUs in Canada are geographically isolated from one another and other River Darter populations within the Mississippi drainage in the United States. Each major drainage system could be genetically distinct. A loss of one of these populations would result in an extensive gap in the range of this species in Canada. River Darter is a little known species and has no direct economic importance; however, it can be numerous in the large rivers and shorelines of lakes in Manitoba and northwestern Ontario and likely plays an important ecological role where abundant. Some states in the United States of America have ranked River Darter as Critically Imperilled (NatureServe 2014).

Distribution

Global range

River Darter has one of the largest latitudinal distributions of any darter species (Figure 2), matched only by Logperch (Percina caprodes) and Johnny Darter (Etheostoma nigrum) (Page and Burr 2011). Its distribution extends north from the Texas coast on the Gulf of Mexico to the Nelson River near Hudson Bay (CMNFI 1989-0677.1) in northern Manitoba (Scott and Crossman 1973; Stewart and Watkinson 2004; Page and Burr 2011) and east from the Saskatchewan River in Saskatchewan (ROM 60976) to the Lake St. Clair watershed in Ontario.

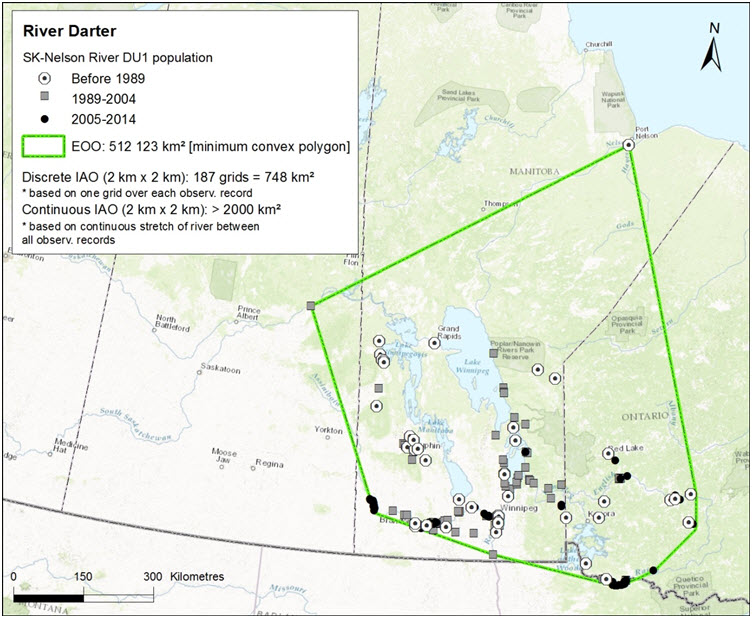

Long description for Figure 3

Map of the distribution of the Saskatchewan-Nelson River populations (designatable unit [DU] 1) of the River Darter. These populations are recorded from the Nelson River watershed in Manitoba and northwestern Ontario, including the watersheds of the Assiniboine, English, Rainy, Red, and Winnipeg rivers and lakes Dauphin, Manitoba, Winnipegosis, and Winnipeg. Occurrences are shown for three time periods (pre-1989, 1989 to 2004, and 2005 to 2014), with extent of occurrence plotted for all periods combined.

Canadian range

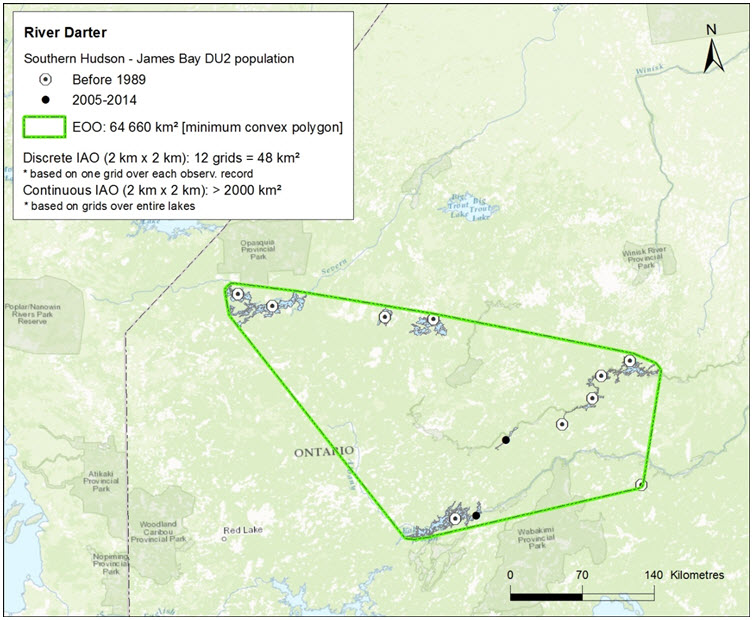

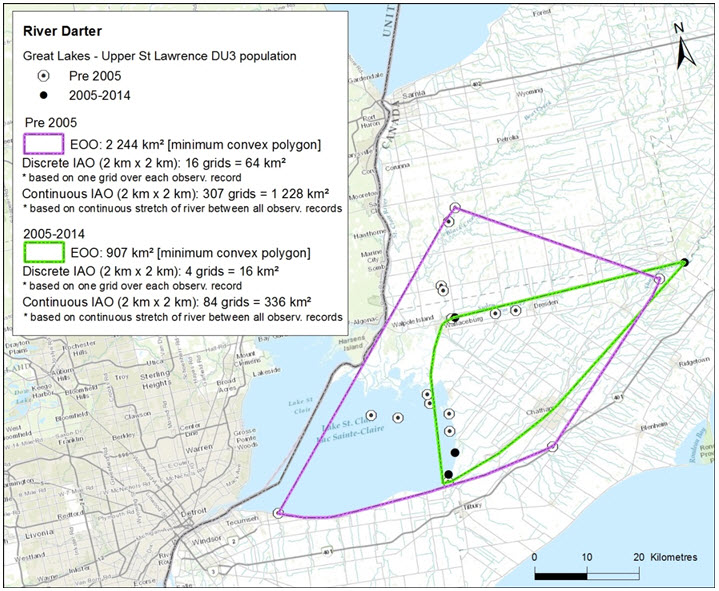

In Canada, River Darter occurs in the Nelson River watershed in Manitoba and northwestern Ontario. This includes the watersheds of the Assiniboine, English, Rainy, Red, and Winnipeg rivers and lakes Dauphin, Manitoba, Winnipegosis and Winnipeg (Figure 3). River Darter is also found in the Attawapiskat, Albany, Severn and Winisk river watersheds that flow into the Hudson or James bays (Figure 4). In southern Ontario, River Darter has been found in the Lake St. Clair watershed (Figure 5).

A single specimen was collected in 1990 from the Saskatchewan River in the tailrace of E.B. Campbell Hydroelectric Station (ROM 60976). This specimen is the only known collection in Saskatchewan or the Saskatchewan River (Appendix 4, Figure 4).

Long description for Figure 4

Map of the distribution of the Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay populations (DU2) of the River Darter. These populations are recorded from the Attawapiskat, Albany, Severn, and Winisk river watersheds, which drain into Hudson or James bays. Occurrences are shown for two time periods (pre-1989 and 2005 to 2014), with extent of occurrence plotted for both periods combined.

Long description for Figure 5

Map of the distribution of the Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence populations (DU3) of the River Darter. These populations are recorded from southern Ontario in the Lake St. Clair watershed. Occurrences are shown for two time periods (pre-2005 and 2005 to 2014), with extent of occurrence plotted for each period.

Extent of Occurrence and Area of Occupancy

DU1 - Saskatchewan - Nelson river populations

Sampling in this DU has been sparse over the previous decades. There is therefore insufficient data on occurrences to examine temporal trends in EOO and IAO so all occurrences have been combined to make these estimates. EOO is estimated to be 512,123 km2 but it is likely an underestimate due to sparse sampling in the more northerly and mostly wilderness part of its distribution (Figure 3). IAO is estimated as 748 km2 (discrete) and >2,000 km2 (continuous). Actual IAO is likely underestimated substantially due to sparse sampling effort.

DU2 - Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay populations

Sampling in this DU has been sparse over the previous decades. There is therefore insufficient data on occurrences to examine temporal trends in EOO and IAO so all occurrences have been combined to make these estimates. EOO is estimated to be 64,660 km2 but it is likely an underestimate due to sparse sampling in the more northerly and mostly wilderness part of its distribution (Figure 3). IAO is estimated as 48 km2 (discrete) and >2,000 km2 (continuous). Actual IAO is likely underestimated substantially due to sparse sampling effort.

DU3 - Great Lakes - upper St. Lawrence populations

Sampling for small-bodied fishes in the DU has been extensive, particularly since 2005, allowing examination of temporal trends in EOO and IAO. Pre-2005 EOO is estimated as 2,244 km2 and has declined to 907 km2 in the most recent decade (Figure 5). We report here both discrete and continuous IAO estimates, but due to the intensity of sampling in this region the actual IAO is likely closer to the discrete than continuous estimate. The discrete IAO has declined from 64 km2 pre-2005 to 16 km2 post-2005 (Figure 5). The continuous IAO estimate has declined from 1228 km2 to 336 km2 over the same time period.

Search effort

Most often, surveys that have detected the species were not specifically sampling for River Darter. A variety of gear has been used to collect River Darter (Table 1). Since 2009, limited sampling with fine-mesh bottom trawls, like the mini-Missouri trawl, has occurred in Canada. Trawling is a very effective gear for sampling small-bodied benthic species like darters (Herzog et al. 2009) and has the potential to expand the known distribution of River Darter and provide a more accurate picture of the status of the species in Canada. Table 1 outlines surveys within the range of River Darter in Canada since 1989.

| DU | Waterbody/Watershed | Survey Description (years of survey effort) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dauphin Lake watershed |

|

| 1 | Assiniboine River |

|

| 1 | Red River watershed |

|

| 1 | Saskatchewan River |

|

| 1 | Lake Winnipeg |

|

| 1 | Winnipeg River watershed |

|

| 2 | Lake St. Joseph |

|

| 2 | Badesdawa Lake |

|

| 3 | Lake St. Clair watershed |

|

| 3 | Detroit River |

|

| 3 | Lake Erie |

|

† Acronyms: OMNR – Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources; DNR – Department of Natural Resources; DFO – Fisheries and Oceans Canada;

Gear type: a – seine net; b – trawl; c – trap net; d – boat electrofishing; e – backpack electrofishing; f – fyke net; g – minnow trap; h – Windemere trap; i – mini-Missouri or Missouri trawl; j - gill net.

DU1 – Saskatchewan - Nelson river biogeographic zone

Non-targeted surveys have been conducted throughout the southern portion of this DU in Manitoba by Fisheries and Oceans Canada (Table 2), confirming and expanding the known distribution of the species since 1989. It is likely that River Darter is more widely distributed in the remote portions of this DU than is currently known and that many more locations exist. The majority of sampling has involved the use of boat or backpack electrofishing; neither is very effective at sampling small-bodied benthic fishes in turbid water. Limited surveys have been conducted with appropriate gear such as the mini-Missouri trawl. Targeted sampling conducted in 2013 and 2014 in northwestern Ontario using a mini-Missouri trawl collected River Darter at most historical sites sampled and had relatively high catch per unit effort (CPUE) (Table 3).

| DU | Waterbody/Watershed | Number of collections | Gear | Effort (sec or hauls) |

Number of fish | Catch Per Unit Effort (fish/sec or fish/haul) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dauphin Lake watershed | 47 | Backpack efishing | 40615 | 0 | - |

| 1 | Assiniboine River | 6 |

Backpack efishing |

6 |

0 |

- |

| 1 | Assiniboine River | 2257 |

Boat efishing |

295810 |

14 | 0.000047 |

| 1 | Assiniboine River | 390 | mini and/or Missouri trawl | 390 | 332 | 0.85 |

| 1 | Red River watershed | 81 | Backpack efishing | 65089 | 0 | - |

| 1 | Red River watershed | 771 | Boat efishing | 268546 | 0 | - |

| 1 | Red River watershed | 81 | mini and/or Missouri trawl | 81 | 0 | - |

| 1 | Red River watershed | 21 | 10 m Seine | 21 | 0 | - |

| 1 | Saskatchewan River | 411 | Boat efishing | 28641 | 0 | - |

| 1 | Lake Winnipeg | 716 | Beam Trawl | 716 | 1 | 0.0014 |

| 1 | Lake Winnipeg | 24 | Boat efishing | 9926 |

9 | 0.0009 |

| 1 | Lake Winnipeg | 11 | 10 m Seine | 11 | 0 | - |

| 1 | Winnipeg River watershed | 5 | Backpack efishing | 5 | 0 | - |

| 1 | Winnipeg River watershed | 188 | Boat efishing | 71293 | 23 | 0.0003 |

| 1 | Winnipeg River watershed | 33 | mini and/or Missouri trawl | 33 | 0 | - |

| 1 | Winnipeg River watershed | 18 | 10 m Seine | 18 | 4 | 0.22 |

| 1 | Rainy River | 21 | Boat efishing | 58447 | 167 | 0.0029 |

| 3 | Thames River | 26 | mini Missouri trawl | 26 | 1 | 0.04 |

| 3 | Sydenham River | 24 | mini Missouri trawl | 24 | 2 | 0.08 |

| DU | Waterbody | Historic location | Date(s) | Gear type | Effort | Mean length (m) | River Darter captured | Density (fish/ha) | CPUE (fish/haul) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rainy River | Yes | 19/06/2013 to 22/06/2013 | trawl | 60 | 306.0 | 152 | 52.0 (11.3) | 2.53 |

| 1 | Rainy River | Yes | 11/09/2013 to 12/09/2013 | trawl | 12 | 282.0 | 17 | 20.7 (8.6) | 1.42 |

| 1 | Rainy River | Yes | 13/06/2014 | trawl | 2 | 365.0 | 3 | 10.3 (10.3) | 1.5 |

| 1 | Lake of the Woods | Yes | 13/06/2014 | trawl | 5 | 174.8 | 21 | 97.5 (65.6) | 4.2 |

| 1 | Balne River | Yes | 14/06/2014 | trawl | 4 | 151.8 | 0 | - | 0 |

| 1 | Red Lake | Yes | 15/06/2014 | trawl | 7 | 121.0 | 1 | 8.1 (8.1) | 0.14 |

| 1 | Chukini River | New | 16/06/2014 | trawl | 3 | 173.3 | 5 | 43.9 (32.2) | 1.66 |

| 1 | English River (lower and upper) | Yes | 16/06/2014 | trawl | 5 | 134.2 | 27 | 140.4 (53.5) | 5.4 |

| 1 | English River (lower and upper) | Yes | 13/09/2014 | trawl | 6 | 273.3 | 17 | 37.6 (20.4) | 2.83 |

| 1 | Barnston Lake | Yes | 16/06/2014 | trawl | 1 | 220.0 | 1 | 18.8 (-) | 1 |

| 1 | Barrel Lake | Yes | 19/06/2014 | trawl | 2 | 215.0 | 1 | 11.8 (11.8) | 0.5 |

| 1 | Sturgeon River | New | 14/09/2014 | trawl | 5 | 411.2 | 26 | 49.5 (20.2) | 5.2 |

| 1 | Lac Seul | Yes | 14/09/2014 | trawl | 4 | 330.0 | 2 | 8.8 (5.4) | 0.5 |

| 1 | Little Turtle Lake | New | 16/09/2014 | trawl | 1 | 570.0 | 1 | 7.0 (-) | 1 |

| 1 | Assiniboine River | Yes | 09/10/2014 | trawl | 8 | 169.9 | 36 | 96.8 (40.4) | 4.5 |

| 1 | Lake Winnipeg | Yes | 08/10/2014 | trawl | 10 | 66.0 | 33 | 182.1 (12.5) | 3.3 |

| 2 | Lake St. Joseph | Yes | 12/09/2014 | trawl | 4 | 305.0 | 30 | 117.8 (68.5) | 7.5 |

| 2 | Badesdawa Lake | New | 12/09/2014 | trawl | 3 | 306.7 | 38 | 109.7 (55.5) | 12.67 |

DU2 – Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay biogeographic zone

There has been limited sampling in the remote as well as accessible portions of this DU. Additional sampling would likely find the species has maintained its EOO since 1989. Given the limited sampling conducted in this DU to date, it is likely that River Darter is more widely distributed than is currently known and many more locations exist. In 2014, targeted sampling with a mini-Missouri trawl was conducted in two lakes in this DU that are road accessible (Tables 1; 3).

DU3 – Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence biogeographic zone

Search effort has been extensive, particularly post-2005, in this DU. More than 1000 sites within the range of River Darter, using a variety of gears, including more recently mini-Missouri trawls, have been sampled (Tables 1; Figure 5; DFO unpubl.).

Habitat

Habitat requirements

River Darter is mainly collected in medium to large rivers or nearshore areas of lakes (Balesic 1971; Stewart and Watkinson 2004). It is associated with a variety of substrates, moderate currents and deeper water (Thomas 1970; Pfleiger 1971; Scott and Crossman 1973; Becker 1983; Kuehne and Barbour 1983). Sampling in the Assiniboine River, Manitoba, with Missouri and mini-Missouri trawls, found River Darter to be the third most common species collected (Watkinson, unpublished data). It was collected most frequently in moderate water velocities (0.4-0.85 m/s) and depths (0.8-1.8 m). River Darter catches were highest on the gravel and cobble substrates. Sampling conducted in 2014 with a mini-Missouri trawl, predominantly in lakes of northwestern Ontario, collected River Darter over gravel and cobble substrates at a mean depth of 3.7 m (Table 4). A single specimen collected with a beam trawl in Lake Winnipeg at 15 m depth (Watkinson, unpublished data) is the deepest documented specimen collected.

River Darter is tolerant of turbid waters (Balesic 1971; Pfleiger 1971; Cooper 1983; Sanders and Yoder 1989) and is a common, if not the most common, darter in turbid rivers (Cooper 1983; Kuehne and Barbour 1983; Watkinson, unpublished data). In Manitoba, its abundance is highest in middle reaches of the Assiniboine River where turbidity is typically more moderate, with Secchi readings of ~0.7 m (Watkinson, unpublished data). Clean gravel and cobble substrates may be important for spawning and feeding. Adults and juveniles are often collected together when sampling.

| DU | Waterbody | Date(s) | Depth (m) | Temperature(°C) | pH | Turbidity (NTUs) | Dissolved oxygen (mg/L) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lake of the Woods | 13/06/2014 | 3.7 | 15.63 | 7.55 | 6.3 | 9.12 |

| 1 | Red Lake | 15/06/2014 | 3.4 | 8.52 | 7.51 | 0.4 | 10.39 |

| 1 | Chukini River | 16/06/2014 | 3.6 | 10.78 | 7.56 | 2.5 | 9.59 |

| 1 | English River | 16/06/2014 | 3.5 | 12.65 | 7.71 | 5.6 | 10.16 |

| 1 | English River | 13/09/2014 | 4.6 | 14.07 | 8.10 | 1.2 | 9.63 |

| 1 | Barnston Lake | 16/06/2014 | 3.0 | 13.79 | 7.56 | 5.8 | 10.03 |

| 1 | Barrel Lake | 19/06/2014 | 3.8 | 15.41 | 7.62 | 1.3 | 9.02 |

| 2 | Lake St. Joseph | 12/09/2014 | 4.8 | 14.44 | 7.10 | 1.3 | 9.67 |

| 2 | Badesdawa Lake | 12/09/2014 | 2.5 | 10.45 | 7.91 | 3.1 | 10.54 |

| 1 | Sturgeon River | 14/09/2014 | 5.0 | 14.56 | 8.02 | 1.1 | 10.01 |

| 1 | Lac Seul | 14/09/2014 | 4.2 | 13.32 | 7.89 | 1.7 | 9.17 |

| 1 | Little Turtle Lake | 16/09/2014 | 2.0 | 12.96 | 7.80 | 5.8 | 9.90 |

Habitat trends

A study of changes in anthropogenic stress levels in watersheds that combined indices of freshwater fish biodiversity, environmental conditions and anthropogenic stress across Canada between 1996 and 2006/8 showed minor decreases in anthropogenic stress levels in DU1 and DU2 watersheds, and increases in anthropogenic stress levels in DU3 watersheds (Chu et al. 2015). It is uncertain what these changes mean for River Darter populations as no direct links to species' abundance or distribution have been identified.

Lake St. Clair and its watershed have experienced physical alteration/modification of habitat, eutrophication, shoreline hardening, and sedimentation associated with intensive agriculture. Excessive nutrient enrichment and turbidity have been identified as issues in the watershed (Staton et al. 2003; TRRT 2004). Habitat in Lake St. Clair changed dramatically after the invasion of Zebra Mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) in the late 1980s when water clarity and the abundance of aquatic macrophytes increased significantly (Griffiths 1993). It is uncertain if changes in water clarity have impacted the River Darter population.

Significant changes have occurred in the Sydenham and Thames river watershed as a result of agricultural practices and urbanization (Staton et al. 2003: TRRS 2004). Prior to European settlement the Sydenham River watershed consisted of 70% forested areas and 30% wetland areas (Staton et al. 2003). Nearly all the wetlands are now drained, and in 1983 only 12% of the forest remained (Staton et al. 2003). Currently, these watersheds are dominated by agriculture. Streamside cover appears to have recovered somewhat over the last several years; however, nutrient levels remain high. Turbidity is high in both watersheds and is probably a result of agricultural runoff that is facilitated by the widespread use of tile drainage throughout the watershed (Staton et al. 2003). The Sydenham and Thames rivers continue to be below standards set by the provincial government for acceptable levels of key parameters such as total phosphorus and E. coli, which could impact fishes via their influence on dissolved oxygen levels (TRRS 2004; SCRCA 2008).

Significant increases in total nitrogen and phosphorus in the Assiniboine and Red river drainages in the past 30 years have led to increased eutrophication of Lake Winnipeg (Jones and Armstrong 2001). Most dams were built well before the last species assessment. Zebra Mussel is now established in Lake Winnipeg and the Red River. The impacts to the lake and river, and specifically River Darter, are unknown at this time. Similar to the Great Lakes, increased water clarity may be expected as well as the potential for significant food web impacts.

Much of the species' range in DU1 and DU2 is located in watersheds that have limited road access with a low human population. Habitat in these portions of the distribution has likely been stable since the last species assessment. Point-source disturbances such as mines and hydro dams are possible in the future. A mainstem dam on the Nelson River is currently under construction.

Biology

Life cycle

Individuals can mature as early as age 1 and reach a maximum age 3 (Thomas 1970) or 4 (Smith 1979) in the USA, with a generation time of 2 years. River Darter collected in 2014 from Manitoba and northwestern Ontario reached a maximum age of 4 years and were sexually mature at age 1 (Table 5).

| DU | Waterbody | Date(s) | Sample size for lt and weight | Mean lt (mm) | Length range (mm) | Mean weight (g) | Sex ratio | Sample size for aging | Mean age (yrs) | Age range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rainy River | 19/06/2013 to 22/06/2013 | 145 (l); 144 (w) | 53.0 (0.4) | 43-67.5 | 1.2 (0.04) | 6♂:71♀ | 98 | 2.6 | 1-4 |

| 1 | Rainy River | 08/08/2013 to 13/08/2013 | 167 | 42.5 (0.7) | 30-72 | 0.6 (0.04) | 65 | 0.7 | 0-3 | |

| 1 | Rainy River | 11/09/2013 to 12/09/2013 | 16 | 46.7 (1.9) | 40-64.5 | 0.8 (0.12) | 3♂:13♀ | 9 | 2.1 | 1-3 |

| 1 | Lake of the Woods | 13/06/2014 | 17 | 43.6 (0.5) | 40-47 | 0.6 (0.02) | 4♂:11♀ | 13 | 1.4 | 1-2 |

| 1 | Red Lake | 15/06/2014 | 1 | 42 | 0.43 | 0♂:1♀ | 1 | 1 | ||

| 1 | Chukini River | 16/06/2014 | 5 | 42.4 (1.8) | 37-48 | 0.6 (0.07) | 1♂:1♀ | 4 | 1.8 | 1-2 |

| 1 | English River | 16/06/2014 | 27 | 41.4 (0.6) | 35-47 | 0.5 (0.03) | 7♂:17♀ | 25 | 1.2 | 1-2 |

| 1 | English River | 13/09/2014 | 17 | 40.3 (1.6) | 30-53 | 0.5 (0.06) | 2♂:14♀ | 15 | 0.6 | 0-3 |

| 1 | Barnston Lake | 16/06/2014 | 1 | 41 | 0.38 | |||||

| 1 | Barrel Lake | 19/06/2014 | 1 | 48.5 | 0.5 | |||||

| 1 | Sturgeon River | 14/09/2014 | 26 | 42.3 (1.4) | 35-60 | 0.7 (0.09) | 13♂:11♀ | 21 | 0.4 | 0-3 |

| 1 | Lac Seul | 14/09/2014 | 1 | 30 | 0.2 | |||||

| 1 | Little Turtle Lake | 16/09/2014 | 1 | 41 | 0.5 | |||||

| 1 | Assiniboine River | 09/10/2014 | 36 | 69.3 (1.4) | 48-93 | 2.9 (0.20) | 0♂:35♀ | 36 | 2.8 | 1-4 |

| 1 | Lake Winnipeg | 08/10/2014 | 31 | 43.5 (1.6) | 33-66 | 0.7 (0.10) | 8♂:18♀ | 31 | 0.8 | 0-3 |

| 2 | Lake St. Joseph | 12/09/2014 | 30 | 33.9 (0.6) | 30-40 | 0.3 (0.02) | 8♂:17♀ | 27 | 0.1 | 0-1 |

| 2 | Badesdawa Lake | 12/09/2014 | 32 | 36.1 (0.4) | 32-43 | 0.3 (0.01) | 11♂:14♀ | 22 | 0.3 | 0-1 |

Reproduction

The reproductive cycle of River Darter is determined by photoperiod and temperature (Hubbs 1985). In Canada, spawning occurs from May to early July (Balesic 1971). In contrast, in Louisiana, at the southern extent of its range, spawning occurs from January to April (Hubbs 1985). Fish predominantly spawn in rivers but ripe individuals are collected in lakes suggesting that spawning occurs there as well (Balesic 1971). Ripe River Darter have been collected in the Assiniboine River between June 22 and 24 when the water temperature was 24°C (Watkinson, unpublished data). Males typically move to spawning sites first (Holm et al. 2009). During spawning, females partially bury themselves in sand or gravel with the male resting on top, holding her in position with his pelvic fins (Dalton 1990). The pair vibrates while eggs are deposited one at a time and then fertilized. Spawning will occur several times over several weeks with different partners. Eggs and young are not guarded (Dalton 1990). A laboratory study of reproductive traits found that eggs were adhesive and hatched nine days after fertilization in 19-21°C water (Balesic 1971). Larvae were 5-6.5 mm long and swimming within several hours of hatching.

Hybridization has been noted with Logperch (Trautman 1981).

Feeding

River Darter feeds primarily during daylight hours (Thomas 1970) and consumes a wide variety of food items (Balesic 1971). In Illinois and Manitoba, stomach contents included dipterans, trichopterans, ephemeropterans, crustaceans, and fish eggs (Thomas 1970; Balesic 1971). Fish in Manitoba also consumed corixids and fishes (Balesic 1971). In Alabama, Tennessee, and Manitoba, gastropods can be an important component of River Darter diet (Balesic 1971; Starnes 1977; Haag and Warren 2006). A recent study of River Darter prey items collected from DU1 and DU2 in June, September, and October confirmed they consume dipterans, trichopterans, ephemeropterans, crustaceans, and gastropods (Table 6), with dominant prey items varying between sites and seasons, likely reflecting differences in prey availability.

| DU | Waterbody | Date(s) | Top Diet Items | Top Diet Items | Top Diet Items |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rainy River | 19/06/2013 to 22/06/2013 | Hydropsychidae | Ephemereliidae | Chironomidae |

| 1 | Lake of the Woods | 13/06/2014 | Chironomidae | Heptageniidae | Hydropsychidae |

| 1 | Red Lake | 15/06/2014 | Trichoptera | Copepoda | Chironomidae |

| 1 | Chukini River | 16/06/2014 | Chironomidae | Trichoptera | Cladocera |

| 1 | English River | 16/06/2014 | Chironomidae | Trichoptera | Ephemeroptera |

| 1 | English River | 13/09/2014 | Zooplankton | Chironomidae | Leptophlebiidea |

| 1 | Sturgeon River | 14/09/2014 | Chaoboridae | Chironomidae | Polycentropodidae |

| 1 | Assiniboine River | 09/10/2014 | Hydropsychidae | Heptageniidae | Lymnaeidae |

| 1 | Lake Winnipeg | 08/10/2014 | Chironomidae | Lymnaeidae | Ephemeroptera |

| 2 | Lake St. Joseph | 12/09/2014 | Cladocera | Zooplankton | Amphipods |

| 2 | Badesdawa Lake | 12/09/2014 | Gastropoda | Zooplankton | Cladocera |

Physiology and adaptability

There is little information available regarding River Darter physiology and adaptability. Cavadias (1986) studied swim-bladder lift in the field and laboratory and found that River Darter would adjust swim-bladder lift based on the amount of current to which they were exposed, reducing lift in higher current, and increasing it in lower current.

Dispersal and migration

River Darter abundance in rivers can vary seasonally, with upstream spawning migrations into rivers occurring in May to July (Balesic 1971). Based on laboratory observations of larval River Darter swimming position near the top of the water column, downstream dispersal may occur in rivers as the surface-water velocities would typically be greater than the larvae's swimming speed (Balesic 1971).

Population sizes and trends

DU1 – Saskatchewan - Nelson river biogeographic zone

Sampling effort and methods

A summary of sampling efforts and methods since 1989 are included in Tables 1, 2 and 3.

Abundance

The original species status report on River Darter concluded that the species was never abundant in Canadian waters (Scott and Crossman 1973; Dalton 1990) as limited collections have been made in Canada (NMC, OMNR, ROM records), with usually only one or two fish taken from a site. The most River Darter reported in a single collection prior to 1989 was 10 specimens (Dalton 1990). Collections made in the last decade using more appropriate gear to sample large rivers have collected considerably more specimens (Table 2 and 3). Non-targeted surveys using Missouri and mini-Missouri trawl surveys in the Assiniboine River found that it was the third most abundant species sampled. Density estimates for River Darter from targeted sampling completed in 2013 and 2014 in this DU ranged from 7-182 individuals/ha (Table 3).

Fluctuations and trends

Fluctuations and trends in population size and density of River Darter in this DU cannot be estimated. The known distribution of River Darter in this DU has expanded in the past 10 years as more intensive sampling of small-bodied fishes has been completed (Milani 2013; Watkinson, unpublished data) (Appendix 4). The low numbers of River Darter that have historically been collected at a limited number of sample locations is likely an artifact of ineffective sampling gears and low effort prior to the 2000s.

River Darter are known from 67 waterbodies in this DU (Appendix 4). This DU contains hundreds of rivers and lakes that have not been sampled specifically for small, benthic fishes like the River Darter. In all likelihood, the species is more widely distributed and abundant.

River Darter has not been collected in the Red River in the last 20 years despite considerable sampling effort (Table 2); however, historical records do exist (Appendix 4). Targeted sampling on gravel and cobble substrates should be conducted to determine the continued presence or absence of this species in the Red River.

Rescue effect

River Darter in the North Dakota and Minnesota portions of the Red River can move downstream into Canada as there are no barriers to movement. However, the St. Andrews Lock and Dam at Lockport is likely a barrier to upstream movement by River Darter. The Assiniboine River population is segmented by the Portage Diversion dam. It acts as an upstream barrier to all fish species. There are numerous hydroelectric dams in the Saskatchewan - Nelson River NFBZ on the Nelson, Winnipeg, English and Rainy rivers that only allow for downstream passage. Despite these barriers, the habitat patches in DU1 are very large and populations are not severely fragmented. The diversion of water from Lake St. Joseph over a control dam on the Root River that flows into Lac Seul, which is part of the English/Winnipeg River system, has the potential to allow River Darter from DU2 to move into DU1.

DU2 – Southern Hudson Bay - James Bay biogeographic zone

Sampling effort and methods

A summary of sampling effort and methods since 1989 are included in Table 1 and 3.

Abundance

Density estimates are only available for River Darter in this DU from lakes St. Joseph (118 individuals/ha) and Badesdawa (110 individuals/ha) (Table 3). Targeted collections found River Darter was most abundant in the two lakes sampled in DU2 (Table 3).

Fluctuations and trends

Changes in population size and density of River Darter in this DU cannot be estimated. No River Darter had been documented from DU2 since 1980 until the targeted sampling was completed in 2014 (Appendix 4; Table 3). While catches of River Darter were low historically (n=20 fish dispersed over 11 sites, Appendix 4), this was likely an artifact of ineffective sampling gear, the depth at which the species is found, and minimal sampling effort due to the remoteness of much of the DU. It is uncertain if River Darter populations are stable in this DU based on existing distribution and catch data. However, similar to DU1, there are hundreds of rivers and lakes that have not been sampled with appropriate gear but may contain River Darter.

Rescue effect

Within DU2, the Attawapiskat, Albany, Severn, and Winisk river watersheds all flow independently into Hudson or James bays. Movement of River Darter between these watersheds or the adjacent DUs to the south is not possible. These watersheds are hundreds of km long and not considered severely fragmented.

DU3 – Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence biogeographic zone

Sampling effort and methods

A summary of sampling efforts and methods since 1989 is included in Tables 1 and 2.

Abundance

Detailed data for River Darter are only available from the Thames and Sydenham rivers (Table 2). Fifty collections were made with a mini-Missouri trawl (the optimal method for collecting River Darter), and only three River Darter were caught.

Fluctuations and trends

Changes and fluctuations in population size and density of River Darter in this DU cannot be estimated. River Darter continues to be rare in this DU. Sampling since the last status report has not yielded more than a few specimens annually, with low catch per unit effort (Table 2). Collections made in Lake St. Clair and its tributaries have expanded our knowledge of the species' range in this DU (Appendix 4).

Rescue effect

The extent of River Darter movement within the Great Lakes - Upper St. Lawrence Biogeographic Zone in lakes St. Clair or Erie and the Detroit River across the international boundary is unknown. Movement of fish from Michigan and Ohio is possible; however, it is likely very limited as River Darter is very rare in Michigan, possibly extirpated in the Lake Erie watershed in Ohio and ranked as Critically Imperilled in both states (NatureServe 2014). Relatively recent trawling by Michigan DNR (Thomas and Haas 2004) only found River Darter in the Canadian waters of Lake St Clair, near the mouth of Thames River.

Threats and limiting factors

Physical alteration/modification of habitat from exotic species, shoreline hardening (rip-rap), industrial and agricultural effluents, nutrients, sedimentation, dams and resulting changes to the hydrograph, and dredging may possibly impact River Darter in Canada (Appendix 1-3). DU 1 and 2 were assessed as having an overall low threat impact whereas DU3 was assessed as a high-medium threat impact.

Our knowledge of threats and their impacts on River Darter populations is limited, as there is little threat-specific cause-and-effect information in the literature. No specific limiting factors have been identified for this species. River Darter abundance in DU3 has never been high and the cause of the declines in the adjacent states of Ohio and Michigan is unknown.

Exotic species

Exotic species may affect River Darter through direct competition for space and habitat, competition for food, and restructuring of aquatic food webs (Thomas and Haas 2004; Poos et al. 2010; Burkett and Jude 2015). At least 182 exotic species have invaded the Great Lakes basin (DU3) since 1840 (Ricciardi 2006) and some of these species may affect River Darter populations to some extent. The Round Goby (Neogobius melanostomus), whose distribution overlaps with River Darter in Lake St. Clair, the Thames River and portions of the Sydenham River, may negatively impact the River Darter through direct competition for food resources as a number of the two species' prey items are shared (Balesic 1971; French and Jude 2001; Burkett and Jude 2015) and occupy similar habitats. Round Goby can feed on fish eggs and larvae (Thomas and Haas 2004; Poos et al. 2010) including potentially those of River Darter. More recently, Burkett and Jude (2015) found that eggs may not constitute an important component of Round Goby diet. Zebra Mussel (Dreissena polymorpha) is present in DU1 and DU3, and possible impacts on the River Darter are not known. River Darter may benefit from the presence of the Zebra Mussel as molluscs are consumed by River Darter (Balesic 1971; Haag and Warren 2006). Zebra Mussel can reduce turbidity, this may be detrimental to River Darter, but has not been studied.

Shoreline hardening

The hardening of shorelines has been suggested as a threat for species at risk fishes (EERT 2008). Degradation and/or loss of gravel and cobble substrates in rivers and the exposed shorelines of lakes is a possible threat to the survival and persistence of River Darter, similar to other darter species (Grandmaison et al. 2004; Bouvier and Mandrak 2010; DFO 2011). Bank hardening has been completed along extensive portions of the south shore of Lake St. Clair in DU3. Bank hardening is common in DU1 along the Assiniboine and Red rivers as well as Lake Winnipeg. The extent to which this impacts River Darter is currently unknown.

Contaminants and toxic substances

Some of the watersheds in DU1 and DU3 where River Darter occur are impacted by household, urban, industrial, forestry, or agricultural activities that can lead to decreased water quality and can have negative, cumulative impacts (EERT 2008). The potential severity of impact is likely linked to duration and intensity of exposure, and ranges from the killing of individuals or their food, to more subtle effects on all life history stages (EERT 2008). This threat can be chronic or episodic (spills) and may also be cumulative.

Sediment loadings

Sediment loading occurs in portions of DU1 and all of DU3. Sediment loadings affect inland watercourses, coastal wetlands, and nearshore habitats by decreasing water clarity, increasing the proportion of fine substrates such as silt, and may have a role in the selective transport of pollutants and nutrients including phosphorus. Sediment loading increases turbidity, which affects a species' vision and may inhibit respiration. Siltation can potentially impact prey abundance for River Darter (Holm and Mandrak 1996) as well as smother their eggs laid in the substrate (Finch 2009). The impacts of high sediment loads on the River Darter in Canada are not known. The species is likely more tolerant of high levels of suspended solids (i.e., turbidity) (Pflieger 1975; Trautman 1981) given that it is abundant in turbid systems throughout its range.

Impoundments

Impoundments and dams modify habitat, alter flow regimes and act as barriers to movement. Thomas (1970) found that abundance in rivers was positively correlated with stream gradient, suggesting that impoundments may be detrimental to River Darter. Impoundments increase the amount of fine sediments in the substrate, and River Darter abundance has been observed to decrease following their installation (Trautman 1981). Impoundments are present on most of the major rivers in DU1 including the Red, Assiniboine, Winnipeg, Rainy, English Saskatchewan, and Nelson rivers. DU2 has a limited number of impoundments on the Albany drainage with more planned in this DU.

Physical alteration/modification of habitat

Considering that River Darter deposit eggs into the substrate during spawning (Simon 1998), dredging can be inferred as a potential threat to spawning sites (Freedman 2010). Freedman (2010) found that dredged sites had an overall reduction in the numbers and diversity of small fishes likely because of decreased food availability or forage efficiency and impacts resulting from sedimentation. In DU3, dredging occurs in Lake St. Clair and occasionally its tributaries.

Number of locations

The most plausible threats for River Darter that could impact large portions of the species' distribution include altered ecosystems due to exotic species, contaminants and/or toxic substances, and impoundments. These threats are specific to a river system or lake, so every distinct watershed should be considered a location in each DU. There are a minimum of 67 locations in DU1 and a minimum of 11 locations in DU2. It can be expected that additional sampling in remote or currently under-sampled waterbodies in both DU1 and DU2 would add numerous locations to each DU. DU3 has three locations; these include Lake St. Clair and the East Sydenham and Thames rivers. Note that the North Sydenham location is likely extirpated and therefore not included in the location count.

Protection, status and ranks

Legal protection and status

In Canada, River Darter has no specific protection, but incidental protection may be provided by the federal Fisheries Act as its entire range is shared by commercial, recreational, and/or Aboriginal fisheries in all DUs.

The River Darter is not protected under the United States Endangered Species Act.

Non-legal status and ranks

The following ranks apply to the conservation status of the River Darter (NatureServe 2014):

Global status: G5 (Secure)

National Status: N5 (Secure)

Ontario Status: S3 (Vulnerable)

Manitoba Status: S5 (Secure)

The species is considered critically imperilled in Georgia (S1), Kansas (S1S2), Michigan (S1), Ohio (S1), Pennsylvania (S1), and West Virginia (S1) (NatureServe 2014).

Habitat protection and ownership