Tweedy’s lewisia (Lewisiopsis tweedyi) COSEWIC assessment and status report 2013

Endangered

2013

Table of Contents

- Document Information

- COSEWIC Assessment Summary

- COSEWIC Executive Summary

- Technical Summary

- Wildlife Species Description and Significance

- Distribution

- Habitat

- Biology

- Population Sizes and Trends

- Threats and Limiting Factors

- Protection, Status, and Ranks

- Acknowledgements and Authorities Contacted

- Information Sources

- Biographical Summary of Report Writer

- Collections Examined

List of Figures

- Figure 1. Tweedy’s Lewisia in flower. Photo by Matt Fairbarns, with permission.

- Figure 2. Line drawing of Tweedy’s Lewisia. J.R. Janish from Hitchcock et al. 1964 with permission.

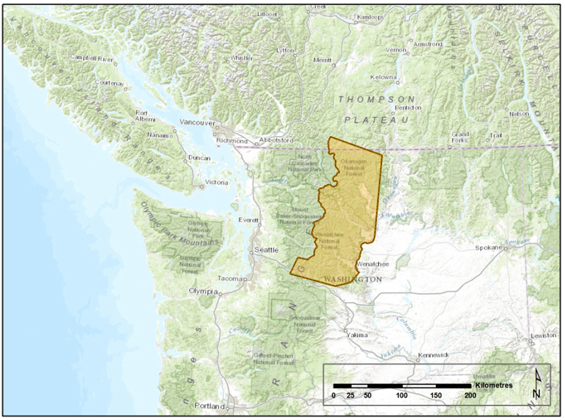

- Figure 3. Global distribution of Tweedy’s Lewisia.

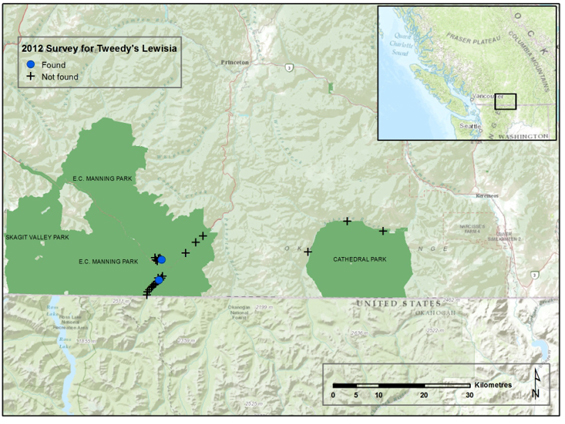

- Figure 4. Canadian distribution of Tweedy’s Lewisia. Dots indicate extant populations, crosses indicate where the species was searched for but not found in preparation of this report.

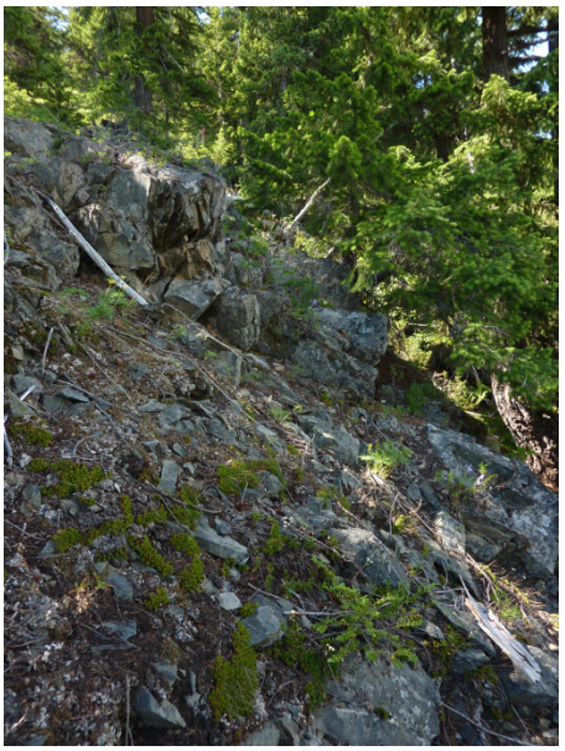

- Figure 5. Tweedy’s Lewisia habitat. Photo by Matt Fairbarns, with permission.

Document Information

COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows:

COSEWIC. 2013. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Tweedy's Lewisia Lewisiopsis tweedyi in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. ix + 22 pp. (www.registrelep-sararegistry.gc.ca/default_e.cfm).

Production note:

COSEWIC acknowledges Matt Fairbarns for writing the status report on the Tweedy’s Lewisia, Lewisiopsis tweedyi, prepared under contract with Environment Canada. This report was overseen and edited by Bruce Bennett, Co- chair of the COSEWIC Vascular Plant Specialist Subcommittee.

For additional copies contact:

COSEWIC Secretariat

c/o Canadian Wildlife Service

Environment Canada

Ottawa, ON

K1A 0H3

Tel.: 819-953-3215

Fax: 819-994-3684

COSEWIC E-mail

COSEWIC web site

Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur le Léwisie de Tweedy (Lewisiopsis tweedyi) au Canada.

Cover illustration/photo:

Tweedy’s Lewisia -- Photo courtesy of Amber Saundry – with permission.

©Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, 2014.

Catalogue No. CW69-14/689-2014E-PDF

ISBN 978-1-100-23571-4

COSEWIC Assessment Summary

Assessment Summary - November 2013

- Common name

- Tweedy’s Lewisia

- Scientific name

- Lewisiopsis tweedyi

- Status

- Endangered

- Reason for designation

- This showy perennial plant is known only from Washington and British Columbia. It exists in Canada as two small subpopulations and has undergone a decline of up to 30% in recent years, possibly due to plant collecting. The small population size and potential impact from changes in moisture regimes due to climate change place the species at on-going risk.

- Occurrence

- British Columbia

- Status history

- Designated Endangered in November 2013.

COSEWIC Executive Summary

Tweedy’s Lewisia

Lewisiopsis tweedyi

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Tweedy’s Lewisia is a clump-forming perennial herb arising from a thick, fleshy, reddish taproot. The evergreen, fleshy leaves form a basal cluster, from which arise multiple stems, each bearing 2-5 showy salmon-coloured, yellowish-pink or white flowers. Tweedy’s Lewisia is a distinctive showy species that has long been grown as an ornamental but has a reputation for being difficult to keep alive and therefore of commercial interest only to alpine garden specialists.

Distribution

Tweedy’s Lewisia occurs from south-central British Columbia south through the Wenatchee Mountains into central Washington State. In Canada, Tweedy’s Lewisia is known from two sites in the Cascade Mountain Ranges, in E.C. Manning Provincial Park.

Habitat

In Canada, Tweedy’s Lewisia occurs on dry south-facing slopes, in subalpine areas within the Moist Warm subzone of the Engelmann Spruce – Subalpine Fir biogeoclimatic zone. This subzone experiences long, cold winters featuring heavy snowfall, and short, cool summers. Substantial snowpacks may persist into June. The plants occur in stable, fractured rock outcrops where needle litter accumulates; in areas with a light canopy of mature Douglas-fir, or no trees. Most of the clumps occur on southeast-facing ledges and crevices while few were found on level surfaces. The shrub and herb layers are sparse and interspecific interactions between Tweedy’s Lewisia and other low-growing species are probably weak. The habitat in the vicinity of the Site 1 subpopulation is not obviously vulnerable to any major disturbances. The habitat surrounding the Site 2 subpopulation has been significantly altered by road building and subsequent road re-alignment but there is no ongoing road building.

Biology

The Canadian population flowers between mid-June and late July. Bees and syrphid flies made up the majority of observed daytime flower visitors but it is not certain that they are the main pollinators. Tweedy's Lewisia is self-fertile and there is little difference in seed set regardless of whether plants were self-fertilized, fertilized by other plants of the same subpopulation, or fertilized by plants from distant subpopulations. The flower scapes of Tweedy`s Lewisia tend to reflex if several seeds are produced, which increases the likelihood that seeds will fall close to the parent. The seeds, which have a sweet honey scent, are often dispersed by ants. Seeds germinate in the autumn or spring and existing plants break shoot dormancy as the snow is melting. Seed viability in Tweedy's Lewisia varies considerably. While germination and growth may begin soon after the seeds are sown, deposited seeds remain viable and may germinate episodically for up to 18 months.

Tweedy's Lewisia is adapted to summer drought but is not adapted to winter rains. Tweedy's Lewisia may be grazed by American Pika, Mule Deer, and Elk. The degree of herbivory tends to be highest among large subpopulations of Tweedy's Lewisia.

Population Sizes and Trends

Two extant subpopulations are currently known from Canada. The total Canadian population in 2012 was estimated at 106-107 mature individuals. The Site 2 subpopulation consists of a single mature individual and a number of juvenile plants. There is debate whether this population may have been deliberately introduced. The Site 1 subpopulation, which contains the balance of the Canadian plants (i.e., 105-106 mature individuals) is currently in decline. There is little prospect of a rescue effect from the USA because of long distance, substantial geographic barriers, and the lack of evident adaptations for long-distance transport of seeds.

Threats and Limiting Factors

The distribution of Tweedy's Lewisia in Canada is strictly limited by the relatively small area of suitable habitat within its narrow extent of occurrence. Existing subpopulations are threatened by plant collecting and more severe summer droughts as an apparent result of climate change.

Protection, Status, and Ranks

The Canadian population of Tweedy's Lewisia is not protected under the federal Species at Risk Act, provincial species at risk legislation, or CITES. Tweedy's Lewisia is ranked globally vulnerable (G3). In Canada, it is ranked as critically imperilled (N1) and has a general status rank of 2: May Be at Risk. In British Columbia, Tweedy's Lewisia is ranked critically imperilled (S1); it is a priority 1 species under the B.C. Conservation Framework and is included on the British Columbia Red List, which consists of species that have been assessed as endangered, threatened or extirpated. Inclusion on the Red List does not confer any legal protection.

The Canadian population of Tweedy's Lewisia occurs within E.C. Manning Provincial Park and is thereby offered some measure of protection under general provisions of the B.C. Park Act .

Technical Summary

Lewisiopsis tweedyi

Tweedy’s Lewisia

Léwisie de Tweedy

- Range of occurrence in Canada (province/territory/ocean):

- British Columbia

Demographic Information

Generation time

>10 years

Is there a continuing decline in number of mature individuals?

yes

Estimated percent of continuing decline in total number of mature individuals within 2 generations

unknown

Observed percent reduction in total number of mature individuals over the last 3 generations.

>30%

Percent reduction or increase in total number of mature individuals over the next 3 generations.

unknown

Observed percent reduction in total number of mature individuals over any 3 generations period, over a time period including both the past and the future.

>30%

Are the causes of the decline clearly reversible and understood and ceased?

Causes of past decline are suspected but may not have ceased. The declines may or may not be reversible.

no

Are there extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals?

no

Extent and Occupancy Information

Estimated extent of occurrence

8 km2

Index of area of occupancy (IAO)

8 km2

Is the total population severely fragmented?

no

Number of locations

2

Is there a continuing decline in extent of occurrence?

no

Is there a continuing decline in index of area of occupancy?

no

Is there a continuing decline in number of subpopulations?

no

Is there a continuing decline in number of locationsFootnote∗?

no

Is there a projected continuing decline in quality of habitat?

no

Are there extreme fluctuations in number of subpopulations?

no

Are there extreme fluctuations in number of locationsFootnote∗ ?

no

Are there extreme fluctuations in extent of occurrence?

no

Are there extreme fluctuations in index of area of occupancy?

no

| Subpopulation | N Mature Individuals |

|---|---|

| Site 1 | 106 |

| Site 2 | 1 |

| Total | 107 |

Quantitative Analysis

Probability of extinction in the wild is at least [20% within 20 years or 5 generations, or 10% within 100 years].

Not available

Threats (actual or imminent, to subpopulations or habitats)

Plant collecting and increased moisture stress due to climate change

Rescue Effect (immigration from outside Canada)

Status of outside population(s)?

Known primarily from eastern Washington State, but not uncommon in rocky habitats within this limited geographical area. Vulnerable (G3, N3 in USA, S3 in Washington).

Is immigration known or possible?

no

Would immigrants be adapted to survive in Canada?

Probable, but not proven.

yes

Is there sufficient habitat for immigrants in Canada?

Some habitat is present but insufficient to allow immigrants a significant chance of encountering it.

no

Is rescue from outside populations likely?

no

Data-Sensitive Species

- Is this a data-sensitive species?

- yes

Status History

- COSEWIC:

- no status (not previously assessed)

Status and Reasons for Designation

- Status:

- Endangered

- Alpha-numeric code:

- B1ab(v)+2ab(v); C2a(i,ii); D1

- Reason for Designation:

- This showy perennial plant is known only from Washington and British Columbia. It exists in Canada as two small subpopulations and has undergone a decline of up to 30% in recent years, possibly due to plant collecting. The small population size and potential impact from changes in moisture regimes due to climate change place the species at ongoing risk.

- Criterion A (Decline in Total Number of Mature Individuals): Not Applicable.

- With an observed and suspected decline of ~30% where the reduction may not have ceased and is not fully understood, criterion A2ad could be met under Threatened. However, the decline is only based on two data points of reference, so it is unclear whether this criterion is actually met.

- Criterion B (Small Distribution Range and Decline or Fluctuation):

- Meets Endangered B1ab(v)+2ab(v) as the EO and IAO are both below thresholds (8 km2), there are two locations, and the number of mature individuals has been observed to be in decline.

- Criterion C (Small and Declining Number of Mature Individuals):

- Meets Endangered C2a(i,ii) as no subpopulation has >250 mature individuals and >95% of the Canadian population occurs in one subpopulation.

- Criterion D (Very Small or Restricted Total Population):

- Meets Endangered D1 as < 250 mature individuals are known. Meets Threatened D2 as there are 2 locations and both subpopulations could be affected by a stochastic event.

- Criterion E: (Quantitative Analysis):

- Not done.

COSEWIC History

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) was created in 1977 as a result of a recommendation at the Federal-Provincial Wildlife Conference held in 1976. It arose from the need for a single, official, scientifically sound, national listing of wildlife species at risk. In 1978, COSEWIC designated its first species and produced its first list of Canadian species at risk. Species designated at meetings of the full committee are added to the list. On June 5, 2003, the Species at Risk Act (SARA) was proclaimed. SARA establishes COSEWIC as an advisory body ensuring that species will continue to be assessed under a rigorous and independent scientific process.

COSEWIC Mandate

The Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) assesses the national status of wild species, subspecies, varieties, or other designatable units that are considered to be at risk in Canada. Designations are made on native species for the following taxonomic groups: mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, fishes, arthropods, molluscs, vascular plants, mosses, and lichens.

COSEWIC Membership

COSEWIC comprises members from each provincial and territorial government wildlife agency, four federal entities (Canadian Wildlife Service, Parks Canada Agency, Department of Fisheries and Oceans, and the Federal Biodiversity Information Partnership, chaired by the Canadian Museum of Nature), three non-government science members and the co-chairs of the species specialist subcommittees and the Aboriginal Traditional Knowledge subcommittee. The Committee meets to consider status reports on candidate species.

Definitions (2013)

- Wildlife Species

- A species, subspecies, variety, or geographically or genetically distinct population of animal, plant or other organism, other than a bacterium or virus, that is wild by nature and is either native to Canada or has extended its range into Canada without human intervention and has been present in Canada for at least 50 years.

- Extinct (X)

- A wildlife species that no longer exists.

- Extirpated (XT)

- A wildlife species no longer existing in the wild in Canada, but occurring elsewhere.

- Endangered (E)

- A wildlife species facing imminent extirpation or extinction.

- Threatened (T)

- A wildlife species likely to become endangered if limiting factors are not reversed.

- Special Concern (SC)Footnote*

- A wildlife species that may become a threatened or an endangered species because of a combination of biological characteristics and identified threats.

- Not at Risk (NAR)Footnote**

- A wildlife species that has been evaluated and found to be not at risk of extinction given the current circumstances.

- Data Deficient (DD)Footnote***

- A category that applies when the available information is insufficient (a) to resolve a species’ eligibility for assessment or (b) to permit an assessment of the species’ risk of extinction.

The Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, provides full administrative and financial support to the COSEWIC Secretariat.

Wildlife Species Description and Significance

Name and Classification

- Scientific Name:

- Lewisiopsis tweedyi (A. Gray) Govaerts

- Synonyms:

- Cistanthe tweedyi (A. Gray) Hershkovitz; Lewisia tweedyi (A. Gray) Robinson; Calandrinia tweedyi A. Gray; Oreobroma tweedyi (A. Gray) Howell

- Common English Names:

- Tweedy’s Lewisia; Tweedy’s Bitterroot; Tweedy’s Pussypaws

- Common French Name:

- Racine-amère de Tweedy

- Family Name:

- Montiaceae (Montia Family)

Tweedy's Lewisia is a distinctive species with no described subspecies or varieties and no taxonomic complications, although there have been major recent changes in its nomenclature. It was originally placed in the genus Calandrinia , but transferred into the genus Lewisia in 1897. Hershkovitz (1992) transferred Tweedy's Lewisia into the genus Cistanthe based on a morphological analysis, which leaned heavily upon the analysis of leaf characters and the presence of a crest-like structure (strophiole) on the seed, also noting that its transfer into Lewisia had been based on an incorrect description of its pattern of fruit dehiscence (Hershkovitz 1992). More recently, Tweedy's Lewisia has been transferred into the single-species genus Lewisiopsis , a usage which has been adopted by many authors (e.g., Hershkovitz 2006). Guillams (pers. comm. 2012) has found that Tweedy's Lewisia does not fit into any subgroups in the genus Lewisia and is cytologically and morphologically very different from all other members of the Montiaceae. On this basis, he supports recognition of the species as Lewisiopsis tweedyi , the lone member of that genus.

Tweedy's Lewisia has long been placed in the Purslane Family (Portulacaceae) but recent studies have led to the subdivision of the Purslane Family into a number of smaller families including the Montia Family (Montiaceae) where Tweedy's Lewisia now resides (Nyffeler and Eggli 2010).

Tweedy's Lewisia is the English name adopted by NatureServe (2012a). Unfortunately the name Tweedy's Lewisia incorrectly implies that it belongs in the genus Lewisia .

Morphological Description

Tweedy's Lewisia is a clump-forming perennial herb arising from a thick, fleshy, reddish taproot up to almost 1 m long (Figures 1, 2). The taproot is topped by a branched crown that gives rise to a dense cluster of thick-stalked, evergreen, smooth, succulent basal leaves, which are lance-shaped to egg-shaped, 10-20 cm long and 1-5 cm wide. The crown also produces one or more (usually several) flowering stems, 10-20 cm tall, which either lack leaves or only bear 1 or two reduced leaves. The flowering stems each bear 2-5 flowers on short (2-5 cm) branches. Each flower has 2 sepals and 7-9 egg-shaped petals that are 2.5-4.0 cm long and salmon-coloured, yellowish-pink or white. The fruits are small (25-40 mm long) egg-shaped, one-celled capsules which open by 3-4 valves. Each fruit contains 12-20 deep brownish-red warty seeds about 2 mm long. Tweedy's Lewisia is a distinctive species which is not likely to be confused with any other species in its range in Canada (Douglas et al. 1999). The chromosome base number (n) for Tweedy's Lewisia is 46 (Hershkovitz 1992).

Figure 1. Tweedy’s Lewisia in flower. Photo by Matt Fairbarns, with permission.

Photo: © Matt Fairbarns, 2012

Figure 2. Line drawing of Tweedy’s Lewisia. J.R. Janish from Hitchcock et al. 1964 with permission.

Photo: J.R. Janish © Hitchcock, 1964

Population Spatial Structure and Variability

There is no evidence of geographic or ecological barriers that have created ecologically significant genetic differences within the Canadian part of the species' range or between the Canadian subpopulations and those outside Canada.

Designatable Units

The Canadian subpopulations comprise a single designatable unit.

Special Significance

Tweedy's Lewisia is endemic to a small area of central Washington State and south-central British Columbia and belongs to a monotypic genus. It is a showy species and Hitchcock et al. (1964) remarked that it is “surely one of the most beautiful wildflowers growing in the state of Washington, and one that surely should be protected from the avarice of practical botanists”. Tweedy's Lewisia has long been grown as an ornamental but has a reputation for being difficult to keep alive and therefore of commercial interest only to alpine garden specialists. Roberts (1995) noted that poor seed performance (particularly low germination rates) in propagation facilities limits its potential as a mass-produced commercial potted plant. Though plant collecting has been implicated as the threat to wild populations (see Threats and Limiting Factors) transplants are known not to be effective as the plants have deep root systems and transplanting will most often result in the death of the plant.

Distribution

Global Range

Tweedy's Lewisia occurs from south-central British Columbia south through the Wenatchee Mountains into Okanogan, Chelan, and Kittitas counties of Washington State, USA (Figure 3). Most subpopulations are in Chelan County, between the towns of Chelan and Leavenworth. Tweedy's Lewisia is not known from east of the Okanogan River or from the west slopes of the Cascades Range. The absence of records of Tweedy's Lewisia from Hart's Pass (WA, USA) is noteworthy. Hart's Pass is on the Cascade Mountains height of land, only about 35 km from the Canadian population (also lies near the height of land). Because at 1889 m (6198 feet) Hart's Pass is the highest point in Washington State that one can drive to, it has been frequently visited by botanists, naturalists and hikers.

There is no evidence of recent global range contraction or expansion. Recent evidence indicates that in the USA, the range and the number Tweedy's Lewisia subpopulations are significantly greater than were reported by Kennison and Taylor (1979). This is believed to represent an improved search effort rather than a true increase in the species' population and distribution (Arnett pers. comm. 2012).

Figure 3. Global distribution of Tweedy’s Lewisia.

Long description for Figure 3

Map showing the global range of the Tweedy’s Lewisia, which occurs from south-central British Columbia south through the Wenatchee Mountains into Okanogan, Chelan, and Kittitas counties of Washington State. Further details can be found in the preceding/next paragraph(s).

Canadian Range

In Canada, Tweedy's Lewisia is known from a small area on the Cascade Mountain Ranges, in E.C. Manning Provincial Park (Figure 4). Tweedy's Lewisia is known from two sites in the park (each less than 1 ha) approximately 5 km from one another. Because of its very limited range in Canada, its Canadian extent of occurrence (EO) (by convention) defaults to its index of area of occupancy (IAO) (8 km2). Cultivated plants were not considered to be part of Canadian population for this assessment.

Figure 4. Canadian distribution of Tweedy’s Lewisia. Dots indicate extant populations, crosses indicate where the species was searched for but not found in preparation of this report.

Long description for Figure 4

Map showing the Canadian range of the Tweedy’s Lewisia, where it is known from two sites in E.C. Manning Provincial Park in the Cascade Mountain Ranges. The sites are approximately 5 kilometres apart. Also shown are localities in E.C. Manning and Cathedral parks that were searched without finding the species. Further details can be found in the preceding/next paragraph(s).

Tweedy's Lewisia was first reported in Canada by Milton (1943) although early records were vague and Chuang (1974) provided the first well-documented report. A second subpopulation was discovered in about 2006. The larger of the two Canadian subpopulations occurs in the relatively remote Site 1 valley, where it is found in habitats typical for the species. There is no evidence that the new population is not a naturally occurring subpopulation, and numerous other rare plant species have been found in nearby areas.

US subpopulations have been found as close as 35 km from the Canadian border (Arnett pers. comm. 2012). These subpopulations are about 55 km southeast of the Canadian subpopulations; direct migration is unlikely because the Pasayten Mountains intervene. Surprisingly, Tweedy's Lewisia has not been found in the western slopes of the valley of the Okanagan River, or on slopes above the lower reaches of the Similkameen River in Canada, even though these areas are relatively close to the northernmost US subpopulations and no mountain barriers intervene.

Search Effort

Because of its striking appearance, its preference for open habitats where it stands out, and its perennial habit, Tweedy's Lewisia is more likely to be reported through incidental observations than are most other rare plants. A number of back-country hikers familiar with the species and its long-documented subpopulation at Site 1 have spent many years exploring remote areas in south-central BC (Krystof pers. comm. 2012; Martyn pers. comm. 2012). The only relatively recent discovery is a small subpopulation of Tweedy's Lewisia near Site 2 in E.C. Manning Provincial Park, found by Louise and Don Martyn in about 2006. This subpopulation was not reported to other botanists until July 2012 out of a concern that once known, it would attract illegal collection (Martyn pers. comm. 2012).

A number of botanists have conducted general rare plant searches in south-central BC during the flowering period of Tweedy's Lewisia. Areas such as E.C. Manning and Cathedral Provincial Parks, and the slopes along the southern reaches of the Okanagan and Similkameen rivers have received the most attention while areas that are not provincial park land and have few roads have received less visitation.

Frank Lomer has been searching for Tweedy's Lewisia in BC since the 1980s. In 2004, Lomer conducted a directed search of sites in E.C. Manning Provincial Park, completing 40 hours of ground-surveys searching suitable habitat in the vicinity of the documented site on Site 1, the high altitude area (including Site 2), and three rocky south-facing slopes near E.C. Manning Provincial Park, east of the documented site (Penny n.d.).

In 2012, Matt Fairbarns spent six days searching for Tweedy's Lewisia at several sites in E.C. Manning Park, the valley of the Ashnola River, and southern portions of the Okanagan River (Figure 4). There were several areas with habitat appearing similar to that occupied by Tweedy's Lewisia in the Site 1 valley but no new subpopulations were discovered.

The lack of success of directed searches by people familiar with the species suggests that it is highly unlikely that there are numerous undiscovered subpopulations in Canada. This is supported by the fact that no subpopulations have yet been reported from areas of the United States along the Canadian border. The late Frank Dorsey, an accomplished alpine garden enthusiast and backcountry hiker, reportedly observed as many as 5-6 subpopulations of Tweedy's Lewisia in Canada (Krystof, pers. comm. 2012) but he left no record of their localities. While it is possible that additional subpopulations remain to be discovered, evidence generally supports Penny's conclusion that the potential for its occurrence outside E.C. Manning Provincial Park appears to be low (Krystof, pers. comm. 2012).

Habitat

Habitat Requirements

The majority of the subpopulations of Tweedy's Lewisia are found in Chelan County, Washington – less than 200 km from the Canadian border. A study by Bubelis (1968) remains the most thorough review of habitat requirements of Tweedy's Lewisia. He found that it occurs across a broad range of elevations from 500-2,200 m although the majority of the subpopulations occur between 1,200-2,000 m.

Tweedy's Lewisia is mainly found in soils derived from basalt or granite. It occurs in a region where serpentine rocks are unusually abundant and where many rare plant species are closely associated with soils derived from serpentine rock (Kruckeberg 1969, 1985). Nevertheless, Tweedy's Lewisia itself does not appear to prefer serpentine environments (Bubelis 1968). Tweedy's Lewisia generally grows in crevices or rock ledges on steep slopes, perhaps because interspecific competition is weaker in such environments (Bubelis 1968) or because they provide rapid drainage, lessening the risk of crown rot.

Tweedy's Lewisia is found in open coniferous forests and unforested sites. The forest canopy, where present, may contain one or more of: Ponderosa Pine (Pinus ponderosa), Whitebark Pine (Pinus albicaulis), Subalpine Fir (Abies lasiocarpa) and Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii). The suite of associated species varies greatly among sites and may, in many cases, have little influence on the vitality of Tweedy's Lewisia (Bubelis 1968), perhaps because overall plant cover tends to be relatively low.

In general, Tweedy's Lewisia appears to favour sites where it is shaded during at least a small part of the day, or where a part of its root system is shaded by rocks (Paghat n.d.).

In Canada, both subpopulations occur on dry south-facing slopes, in upper slope positions within the Moist Warm subzone of the Engelmann Spruce – Subalpine Fir biogeoclimatic zone (ESSFmw). The ESSFmw experiences long, cold winters featuring heavy snowfall, and short, cool summers. Substantial snowpacks may persist into June. On modal sites, the ESSFmw is characterized by forests dominated by Subalpine Fir and Engelmann Spruce (Picea engelmannii) and, to a lesser extent, Amabilis Fir (Abies amabilis). Dry sites, however, tend to be dominated by Douglas-fir, often with Lodgepole Pine (Pinus contorta) and Subalpine Fir, over lower layers typically dominated by Falsebox (Paxistima myrsinites), Black Huckleberry (Vaccinium membranaceum) and Pinegrass (Calamagrostis rubescens). The very driest sites typically have a canopy dominated by Lodgepole Pine and Subalpine Fir, over lower layers dominated by Black Huckleberry, Common Juniper (Juniperus communis), Falsebox, lichens of the genus Cladonia and mosses of the genus Racomitrium (Green and Klinka 1994).

The main subpopulation, along Site 1, occurs between 1,400 and 1,500 m. The plants occur in stable, fractured rock outcrops where needle litter accumulates; in areas with a light canopy of mature Douglas-fir, or no trees (Figure 5). Most of the clumps occur on southeast-facing ledges and crevices, while few were found on level surfaces where drainage might not be so rapid. The shrub and herb layers are sparse, and interspecific interactions between Tweedy's Lewisia and other low-growing species are probably weak. This habitat type (i.e., sparsely vegetated, rocky, south-facing slopes) is of limited availability at E.C. Manning Provincial Park (Lomer ex. Penny n.d., pers. obs.).

Figure 5. Tweedy’s Lewisia habitat. Photo by Matt Fairbarns, with permission.

Photo: © Matt Fairbarns, 2012

Habitat Trends

The habitat surrounding the Site 2 subpopulation has been significantly altered by road building and subsequent road re-alignment but there is no ongoing road building. The habitat in the vicinity of the Site 1 subpopulation is secure from major disturbances. Much of the habitat in areas with potential for unreported subpopulations of Tweedy's Lewisia, between the existing subpopulation and the Similkameen River, is contained within Provincial Parks and other protected areas where further habitat loss by road construction is unlikely. Extensive logging has, however, greatly altered the ecology of south-facing slopes in the uplands immediately east and west of the Pasayten River which do not lie within a protected area. Areas that were formerly open forests of large Douglas-fir, and open glades within other forest types, may have once provided suitable habitat for Tweedy's Lewisia but have now been heavily altered. Their understory vegetation and upper soil horizons have changed greatly as the result of timber felling and silviculture operations.

The habitat for the two known subpopulations has not yet been substantially altered by exotic invasive species, although similar habitat in the region has been heavily impacted by exotic grasses and forbs, particularly where there is livestock grazing as in the Snowy Protected Area, which lies east of Cathedral Provincial Park. It is therefore likely that the habitat supporting Tweedy's Lewisia will gradually suffer invasion by exotic plants.

Biology

Much of the available information on the field biology of Tweedy's Lewisia comes from Washington State (Bubelis 1968; Kennison and Taylor 1979) and is supplemented by information from sources concerned with its horticultural value (e.g., Milton 1943; Colley and Mineo 1985; Roberts 1995). These sources of information have been supplemented by the report writer's unpublished observations as well as those of other naturalists and botanists.

Life Cycle and Reproduction

Flowering at even a single site may occur over several weeks, particularly if a subpopulation contains a mix of plants growing in full sun and plants growing in partial shade. In the main range of the species, the flowering season may begin as early as mid-April in low-elevation subpopulations and end as late as early August at higher elevations (Bubelis 1968). Canadian population flowers from mid-June to late July (Fairbarns, pers. obs.). Bees and syrphid flies made up the majority of daytime flower visitors, but it is not certain that they are the main pollinators. Tweedy's Lewisia is self-fertile and there is little difference in seed set regardless of whether plants were self-fertilized, fertilized by other plants of the same subpopulation, or fertilized by plants from distant subpopulations. Bubelis (1968) found that plants did not set seed when pollinators were excluded .

Seeds germinate in the autumn or spring and, in Washington, existing plants break shoot dormancy in late March or April as the snow is melting (Bubelis 1968). Canadian plants may not break dormancy until May, when snow melt is complete.

Seed viability in Tweedy's Lewisia varies considerably, and while germination may begin when favourable conditions prevail in the first autumn/spring, some or even most seed may not germinate until the second autumn/spring. Most seeds of Tweedy's Lewisia do not remain viable after 24 months (Baulk pers. comm. 2013). It appears that dormancy is related to seed coat characteristics because removal of the seed coat results in rapid, high rates of germination (Roberts 1995). The presence of a strophiole (an outgrowth of the hilum region which restricts water movement into and out of seeds) may contribute to dormancy in some seeds.

There is no information on the average age of plants in Canada or elsewhere. The perennial nature of the plant, and the presence of large taproots which would develop slowly, suggest that individuals are very long-lived. It appears probable that the average age of mature plants exceeds 10 years.

Physiology and Adaptability

Tweedy's Lewisia is adapted to summer drought. Most seeds probably germinate in the autumn, and snow melt seems to be a more important source of moisture than precipitation. Young plants that germinate in the spring must reach a critical size in order to survive the summer drought (Bubelis 1968). Some closely related and ecologically similar species of Lewisia use Crassulacean acid metabolism (CAM), a carbon fixation pathway that evolved in some plants as an adaptation to arid conditions (Guralnick and Jackson 2001). While CAM has not been investigated in Tweedy's Lewisia, it could play a role in the species' adaptation to drought. Tweedy's Lewisia is not adapted to winter rains, which may define the western limit of its range; plants grown in gardens in the Pacific Northwest tend to succumb to crown rot unless they receive excellent drainage and are protected from rain. Nevertheless, when grown in gardens Tweedy's Lewisia can withstand abundant winter rainfall as long as the soil drains quickly (Paghat n.d.).The root can grow to be 60-90 cm long although some are much shorter.

Dispersal and Migration

The flower scapes of Tweedy`s Lewisia tend to reflex if several seeds are produced, which increases the likelihood that seeds will fall close to the parent plant. The seeds are often dispersed by ants, which may carry up to five seeds at a time (Bubelis 1968). The seeds of Tweedy's Lewisia have a sweet honey scent which may serve to attract ants (Paghat n.d.). The fatty acids and starch content within strophioles seems to be an occasional but sufficient reward for ants (Casazza et al . 2008).

Interspecific Interactions

Tweedy's Lewisia may be grazed by American Pika (Ochotona princeps), Mule Deer (Odocoileus hemionus) and Elk (Cervus canadensis). The degree of herbivory tends to be highest among large subpopulations of Tweedy's Lewisia, and in extreme cases over 50% of the plants may be cropped, losing 10-80% of their foliage (Bubelis 1968).

Population Sizes and Trends

Sampling Effort and Methods

Aerial photographs were examined prior to the field survey. Ten promising sites were identified within 5 km of the known subpopulations in Manning Park and several promising south-facing slopes were identified, along the Ashnola River Valley. Past collections indicated that the best survey period for the Canadian population is between June 1st and July 15th. Surveys were conducted in mid-June and mid-July 2012. Sites were examined by walking throughout areas identified as having relatively high potential for Tweedy's Lewisia, scanning large areas using binoculars. Any promising habitat found was examined in detail by using the “meander search” survey method which is typically followed for reconnaissance surveys in complex terrain. This involved walking through each target site and searching for Tweedy's Lewisia in all promising microhabitats. The major drawback of the meander search approach is a tendency for surveyors to oversample areas that are easier to walk in. This was addressed by overlaying a gridded transect survey in areas where habitat conditions were most suited to Tweedy's Lewisia.

The results of the directed survey were supplemented with information on the Site 2 subpopulation gathered in late July 2012, provided by Hans Roemer (pers. comm. 2012).

Abundance

Two extant subpopulations are currently known from Canada. Subpopulations are defined by a distance of >1 km of unsuitable habitat (NatureServe 2012b). The current Canadian population is 106-107 mature individuals (Fairbarns, pers. comm.2012).

Site 1

On July 9, 2012, a total of 106 mature plants of Tweedy's Lewisia were counted in the Site 1 subpopulation, over an area of approximately 5,000 m 2 at an elevation of approximately 1,470 m. There were 79 mature individuals above the trail and 27 mature individuals below the trail.

Site 2

In July 27, 2012, a single mature individual and several small juvenile plants were observed on Site 2 (Roemer, pers. comm. 2012). There are contradicting opinions about whether this subpopulation occurs naturally or was introduced. Roemer believes that it is likely a naturally occurring subpopulation because there is little evidence of disturbance and it occurs in habitat typical of the species where he has seen it in the Wenatchee Mountains. Roemer (pers. comm. 2012) suspects that if the subpopulation is naturally occurring, it may have been larger in the past and declined due to collecting (the site is only a few metres from a well-travelled road).

Martyn, who discovered this subpopulation in about 2006, feels that it may be native, or possibly introduced (pers. comm. 2012). Mosquin (pers. comm. 2012) is also uncertain about its origin; it is found very close to the road. A genetic study that could link the plant at this site to nearby Manning Park populations or to Wenatchee Mountain, US populations that are the source of garden stock would be useful in answering the question. The fact that this population was not discovered by Lomer (pers. comm. 2012) during a directed survey for Tweedy's Lewisia on Site 2 in 2004 lends support to an alternative argument that this population was recently introduced. However, it may have simply been undetectable in 2004; the clustered basal leaves, though generally evergreen, may die back in cultivation and the plant may remain dormant in unfavourable years (Björk pers. comm. 2012).

It is possible that the Site 2 subpopulation represents a recent natural colonization event but the absence of any recently reported colonization events in Canada and the lack of “satellite” occurrences around the Site 1 subpopulation suggest that natural colonization events, at least in Canada, are extremely rare.

Fluctuations and Trends

The lack of consistent survey effort complicates the detection of fluctuations and trends in the population size of Tweedy's Lewisia.

Site 1

Although there is a long history of observations for the subpopulation at Site 1, observations by Lomer (Penny n.d.) probably provide the earliest comprehensive subpopulation report. Lomer found a total of 152 mature individuals of Tweedy's Lewisia in 2004, which suggests a decline of approximately 30% over the subsequent 8 years. Both Martyn (pers. comm. 2012) and Krystof (pers. comm. 2012) have observed an evident, though unquantified, decline in the size of the subpopulation in recent years. Krystof has visited the subpopulation almost every year and recalled that the decline was sudden, occurring in about 2007.

Site 2

Only a single mature individual has ever been observed.

Rescue Effect

Tweedy's Lewisia is largely restricted to elevations of less than 2,000 m. Most of the Pasayten Mountains, which intervene between Canada and the nearest US subpopulations, lie above 2,000 m (and even the lowest passes are above 1,800 m). This elevation barrier, the 35 km gap between the northernmost US subpopulation and the Canadian border, and the absence of a mechanism for primary seed dispersal across distances of more than a few metres means that it is highly unlikely that seed dispersed from US subpopulations would mitigate a Canadian extirpation or population decline. In the unlikely case that seeds from US subpopulations did disperse into Canada they are unlikely to produce new subpopulations because they are very unlikely to encounter suitable habitat.

Threats and Limiting Factors

The major limiting factor across the Canadian range of Tweedy's Lewisia is its restriction to a rather rare habitat type within a small area in Canada. Threats associated with habitat changes are addressed above (see Habitat Trends). The Canadian population of Tweedy`s Lewisia is not severely fragmented though most or all of the plants occur in a single subpopulation, the habitat occurs as small, widely separated patches within the landscape and the seeds have no evident adaptations to assist in long-distance dispersal.

Plant Collecting

Martyn (pers. comm. 2012) suspects that the decline in the Site 1 subpopulation in recent years is the result of collecting by alpine plant enthusiasts. Krystof (pers. comm. 2012), in describing the apparently abrupt decline in this subpopulation in about 2007, notes that the losses were greatest among juvenile plants growing along the hiking trail that bisects the subpopulation, particularly in the less rocky microhabitats where digging would be easiest. Krystof also noted evidence of digging at the site.

Climate Change

Krystof (pers. comm. 2012) has noted poor seed production in recent years in many US subpopulations of Tweedy's Lewisia and in the main Canadian subpopulation at Site 1. He feels this may be related to a growing trend towards greater moisture stress during the fruiting season (late July) in recent years. Climate models (BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection 2002) suggest that anthropogenic climate change in south-central British Columbia will result in decreased snowpacks at mid-elevations. Decreased snowpacks would result in reduced snow melt, a variable which appears to be critical to the Tweedy's Lewisia growth. Climate models also predict less summer soil moisture which likely determines seed production.

Protection, Status, and Ranks

Legal Protection and Status

Tweedy's Lewisia is not protected under federal Species at Risk Act or provincial species at risk legislation (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012). Tweedy's Lewisia was removed from CITES Appendix 2 (CITES n.d.a.) following a delisting proposal that reported the existence of many more populations in the USA than had been previously known. There was also an opinion that international trade was probably slight or non-existent, because the species is relatively easy to propagateFootnote 1, and there are significant procedural barriers which discourage trans-border shipping (CITES n.d.b.).

Non-Legal Status and Ranks

Tweedy's Lewisia is ranked by NatureServe (2012a) as G3 (globally vulnerable). In Canada it is ranked as N1 (critically imperilled) according to NatureServe (2012a) and has a general status rank (Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council 2011) of 2: may be at risk.

In British Columbia Tweedy's Lewisia is ranked S1 (critically imperilled). It is a priority 1 species under the B.C. Conservation Framework (Goal 3: maintain the diversity of native species and ecosystems) and is included on the British Columbia Red List, which consists of species that have been assessed as endangered, threatened or extirpated based on available information. Inclusion on the Red List does not confer any legal protection (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

Tweedy's Lewisia was added to the Washington State list of Sensitive Species following the preparation of a status report (Kennison and Taylor 1979) but was down-listed to the Washington State Monitor List in 1982.

Habitat Protection and Ownership

The Canadian population of Tweedy's Lewisia occurs within E.C. Manning Provincial Park and is thereby offered some measure of protection under general provisions of the B.C. Parks Act .

Acknowledgements and Authorities Contacted

Shane Ford assisted with the fieldwork. Jenifer Penny and Marta Donovan (B.C. Conservation Data Centre) provided useful background information. Paul Krystof and Don Martyn provided very useful information on the history of the subpopulations in E.C. Manning Provincial Park and Joe Arnett provided invaluable background material as well information on the distribution and status of subpopulations in Washington State.

Authorities Consulted

Dr. Rhonda L. Millikin. A/Head Population Assessment, Pacific Wildlife Research Centre. Canadian Wildlife Service. Delta, British Columbia.

Jennifer Doubt. Chief Collection Manager – Botany. Canadian Museum of Nature. Ottawa, Ontario.

Dean Nernberg. Species at Risk Officer. Director General of Environment, National Defence Headquarters.

Dr. Patrick Nantel. Conservation Biologist, Species at Risk Program. Ecological Integrity Branch, Parks Canada. Gatineau, Quebec.

David F. Fraser. Endangered Species Specialist, Ecosystem Branch, Conservation Planning Section. Ministry of Environment, Government of British Columbia. Victoria, British Columbia.

Jenifer Penny. Botanist. British Columbia Conservation Data Centre. Victoria, British Columbia.

Information Sources

Arnett, J., pers. comm. 2012. E-mail to M. Fairbarns. October 25, 2012 . Rare Plant Botanist. Washington Natural Heritage Program.

Baulk, P. pers. comm. 2013. E-mail to M. Fairbarns . March 21, 2013. Lewisia specialist, Ashwood Nurseries, U.K.

Björk, C., pers. comm. 2012. Telephone conversation with M. Fairbarns . November 8, 2012. Botanist.

B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2012. BC Species and Ecosystems Explorer. B.C. Ministry of Environ. Victoria, B.C. [accessed April 25, 2012].

B.C. Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection. 2002. Indicators of climate change for British Columbia; BC Ministry of Water, Land and Air Protection, 50 p [accessed October 15, 2012].

Bubelis, W.F. 1968. Contributions to an ecological life history of Lewisia tweedyi (Gray) Robins. (Portulacaceae). Research report submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science. University of Washington. 41 pp.

Canadian Endangered Species Conservation Council. 2011. Wild Species 2010: The General Status of Species in Canada. [accessed: October 10, 2012].

Casazza, G., B. Borghesi, E. Roccotiello, and L. Minuto. 2008. Dispersal mechanisms in some representatives of the genus Moehringia L. (Caryophyllaceae). Acta Oecologica. 33(2):246-252.

Chuang, C.C. 1974. Lewisia tweedyi : A plant record for Canada. Syesis 7: 259-260.

CITES. n.d.a. Amendments to Appendices I and II (PDF (28 KB) of the Convention adopted by the Conference of the Parties at its 10th meeting in Harare, Zimbabwe, from 9 to 20 June 1997. [accessed: October 25, 2012].

CITES. n.d.b. Consideration of proposals for amendment of Appendices I and II (PDF (28 KB).

Colley, J.C., and B. Mineo. 1985. Lewisias for the garden. Pac. Hort. 46:40-49.

Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria 2007-2011. Managed by the University of Washington Herbarium, Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture, Box 355325, University of Washington, Seattle, WA. [accessed: October 30, 2012].

Douglas, G.W., D. Meidinger, and J. Pojar, eds. 1999. Illustrated Flora of British Columbia. Volume 4: Dicotyledons (Orobanchaceae through Rubiaceae). B.C. Ministry of Environment, Lands & Parks and B.C. Ministry of Forests, Victoria. 427 pp.

Green, R.N., and K. Klinka. 1994. A field guide to site identification and interpretation for the Vancouver Forest Region, Land Management Handbook No. 28. British Columbia Ministry of Forests.

Guilliams, M., pers. comm. 2012. E-mail to M. Fairbarns . November 9, 2012. Botanist. Baldwin Lab and UC/JEPS Herbaria, University of California Berkeley.

Guralnick, L.J., and M.D. Jackson. 2001. The Occurrence and Phylogenetics of Crassulacean Acid Metabolism in the Portulacaceae. International Journal of Plant Sciences 162: 257-262.

Hershkovitz, H.A. 1992. Leaf Morphology and Taxonomic Analysis of Cistanthe tweedyi (nee Lewisia tweedyi ; Portulacaceae). Systematic Botany 17:220-238.

Hershkovitz, H.A. 2006. Ribosomal and chloroplast DNA evidence for diversification of western American Portulacaceae in the Andean region. Gayana Bot. 63(1): 13-74, 2006.

Hitchcock, C.L., A. Cronquist, M. Ownbey, and J.W. Thompson. 1964. Vascular Plants of the Pacific Northwest. Part 2: Salicaceae to Saxifragaceae. University of Washington Press, Seattle. 597 pp.

Kennison, J.A. and R.J.Taylor 1979. Status report for Lewisia tweedyi . Prepared for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 14 pp.

Kruckeberg, A.R. 1969. Plant life on serpentine and other ferromagnesian rocks in northwestern North America. Syesis 2:15-114.

Kruckeberg, A.R. 1985. California Serpentines: Flora, Vegetation, Geology, Soils, and Management Problems. University of California. 196 pages

Krystof, P. pers. comm. 2012. Telephone conversation with M. Fairbarns . October 11, 2012. Backcountry hiker and Lewisia enthusiast.

Martyn, D., pers. comm. 2012. Telephone conversation with M. Fairbarns . October 10, 2012. Backcountry hiker and Lewisia enthusiast.

Milton, J. 1943. The haunts of Lewisia tweedyi . National Horticultural Magazine 22:30-33.

Mosquin, D., pers. comm. 2012. E-mail to M. Fairbarns . August 9, 2012. Education and Technology Manager. University of British Columbia Botanical Garden.

NatureServe. 2012a. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. [accessed: October 25, 2012].

NatureServe Explorer. 2012b. Habitat-based Plant Element Occurrence Delimitation Guidance, 1 October 2004. [accessed: October 25, 2012].

Nyffeler, R., and U. Eggli. 2010. Disintegrating Portulacaceae: A new familial classification of the suborder Portulacineae (Caryophyllales) based on molecular and morphological data. Taxon 59: 227-240.

Paghat the Ratgirl. n.d. Garden of Paghat: Tweedy's Bitterroot”. [accessed: October 5, 2012].

Penny, J. n.d. Search effort for Lewisia : population sizes and trends. Unpublished notes. Botanist, B.C. Conservation Data Centre.

Roberts, C.N. 1995. Research and development of herbaceous perennials as new potted plants for commercial floriculture: case studies with Lewisia seed biology and Dicentra postproduction performance. M.Sc. thesis. University of British Columbia (Department of Plant Science). 66 pp.

Roemer, H., pers. comm. 2012. Telephone conversation with M. Fairbarns . October 10, 2012. Rare Plant Botanist.

Biographical Summary of Report Writer

Matt Fairbarns has a B.Sc. in Botany from the University of Guelph (1980). He has worked on rare species and ecosystem mapping, inventory and conservation in western Canada for approximately 30 years.

Collections Examined

Collections at the University of British Columbia, Royal British Columbia Museum, Simon Fraser University, University of Victoria, Pacific Forestry Centre, University of Washington, Washington State University and University of Idaho were consulted through the online database of the Consortium of Pacific Northwest Herbaria (2007-2011).