Blanding’s turtle (Emydoidea blandingii): proposed recovery strategy 2016

Species at Risk Act

Recovery Strategy Series

Adopted under Section 44 of SARA

Blanding's Turtle

Photo: ©Joe Crowley

2016

Table of Contents

- Document Information

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Executive Summary

- Recovery Feasibility Summary

- 1. COSEWIC Species Assessment Information

- 2. Species Status Information

- 3. Species Information

- 4. Threats

- 5. Population and Distribution Objectives

- 6. Broad Strategies and General Approaches to Meet Objectives

- 7. Critical Habitat

- 8. Measuring Progress

- 9. Statement on Action Plans

- 10. References

- Appendix A: Effects on the Environment and Other Species

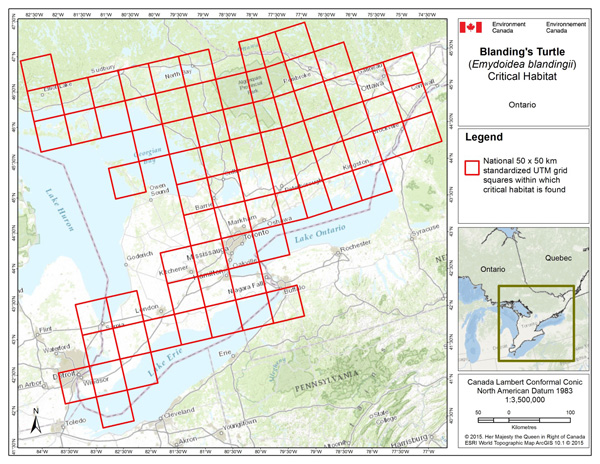

- Appendix B: Critical Habitat for the Blanding's Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence Population, in Canada

List of Tables

- Table 1. Threat Assessment Table

- Table 2. Recovery Planning Table

- Table 3: Detailed biophysical attributes of suitable habitat for specific life cycle activities of the Blanding's Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population -Suitable Aquatic Habitat

- Table 4: Schedule of Studies

- Table 5: Examples of Activities Likely to Destroy Critical Habitat for the Blanding's Turtle

- Table A-1. Some of the Species at Risk That May Benefit from Conservation of Blanding's Turtle Habitat

- Table B-1. Critical Habitat for the Blanding's Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence Population, in Canada Occurs Within these 50 x 50 km Standardized UTM Grid Squares Where Criteria Described in Section 7 Are Met.

List of Figures

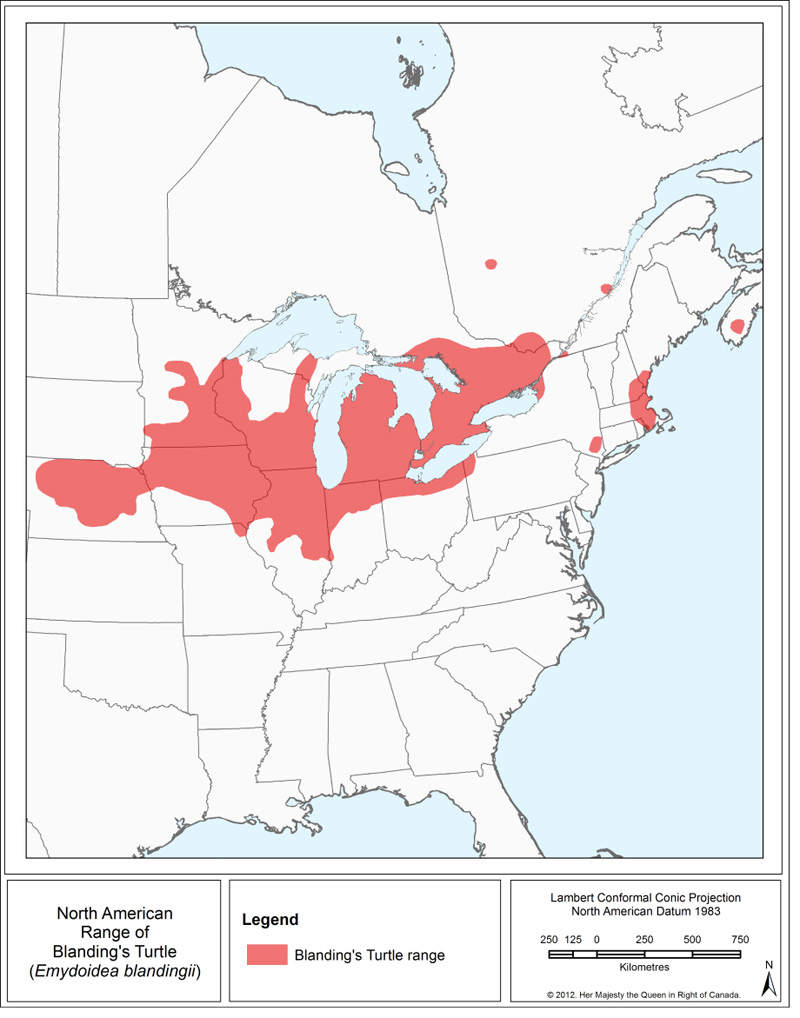

- Figure 1. North American Range of the Blanding's Turtle (adapted from Ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs 2010)

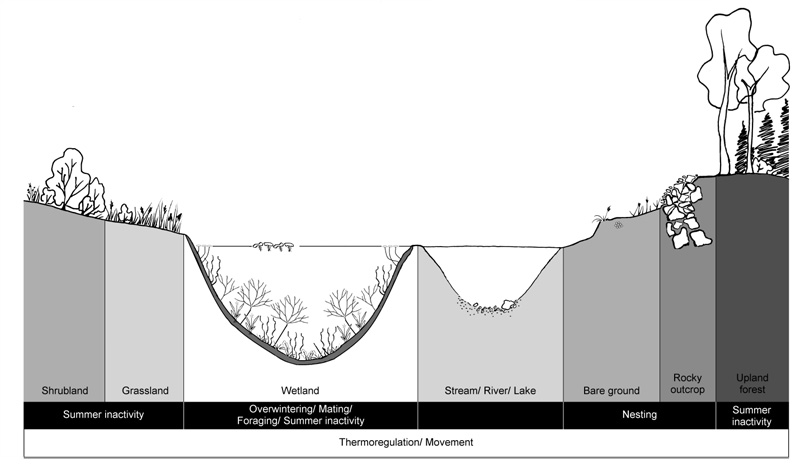

- Figure 2. Habitat Features of the Blanding's Turtle Suitable Habitat for each Life Cycle Activity

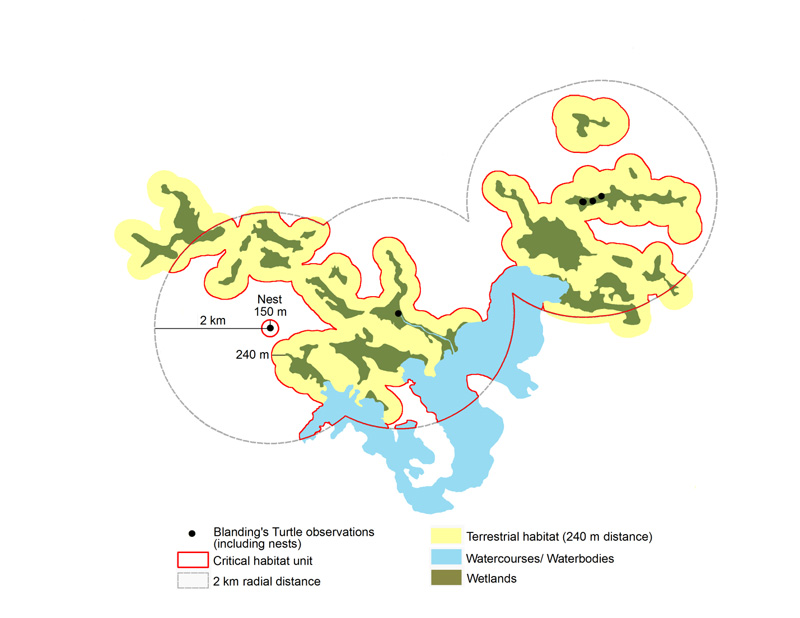

- Figure 3. Schematic of Critical Habitat Criteria for the Blanding's Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence Population

- Figure B1. Grid Squares Identified as Containing Critical Habitat for the Blanding's Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence Population

Document Information

Recovery Strategy for the Blanding's Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii), Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population in Canada - 2016 [Proposed]

Recommended citation:

Environment Canada. 2016. Recovery Strategy for the Blanding's Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii), Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population, in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vii + 49 pp.

For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk Public Registry.

Cover illustration: © Joe Crowley

Également disponible en français sous le titre

« Programme de rétablissement de la tortue mouchetée (Emydoidea blandingii), population des Grands Lacs et du Saint-Laurent, au Canada [Proposition] »

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Recovery Strategy for the Blanding's Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii), Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population, in Canada - 2016

Preface

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c. 29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years after the publication of the final document on the SAR Public Registry.

The Minister of the Environment and the Minister responsible for the Parks Canada Agency is the competent minister under SARA for the Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population, and has prepared this strategy, as per section 37 of SARA. To the extent possible, it has been prepared in co-operation with the Province of Ontario (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources) and the Province of Quebec (Ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs).

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment Canada, the Parks Canada Agency, or any other jurisdiction alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Blanding’s Turtle and Canadian society as a whole.

This recovery strategy will be followed by one or more action plans that will provide information on recovery measures to be taken by Environment Canada, the Parks Canada Agency, and other jurisdictions and/or organizations involved in the conservation of the species. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

The recovery strategy sets the strategic direction to arrest or reverse the decline of the species, including identification of critical habitat to the extent possible. It provides all Canadians with information to help take action on species conservation. When the recovery strategy identifies critical habitat, there may be future regulatory implications, depending on where the critical habitat is identified. SARA requires that critical habitat identified within a national park named and described in Schedule 1 to the Canada National Parks Act, the Rouge National Urban Park established by the Rouge National Urban Park Act, a marine protected area under the Oceans Act, a migratory bird sanctuary under the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 or a national wildlife area under the Canada Wildlife Act be described in the Canada Gazette, after which prohibitions against its destruction will apply. For critical habitat located on other federal lands, the competent minister must either make a statement on existing legal protection or make an order so that the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat applies. For any part of critical habitat located on non-federal lands, if the competent minister forms the opinion that any portion of critical habitat is not protected by provisions in or measures under SARA or other Acts of Parliament, or the laws of the province or territory, SARA requires that the Minister recommend that the Governor in Council make an order to prohibit destruction of critical habitat. The discretion to protect critical habitat on non-federal lands that is not otherwise protected rests with the Governor in Council.

Acknowledgements

This document was developed by Rachel deCatanzaro, Krista Holmes, Angela McConnell, Marie-Claude Archambault, Lee Voisin (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region), Kari Van Allen, Barbara Slezak, Carollynne Smith, Bruna Peloso, and Louis Gagnon (formerly Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario Region), and Gabrielle Fortin (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Quebec Region). Numerous other people also drafted content or had input into various versions of the present recovery strategy, including Patrick Galois (Amphibia-Nature), Sylvain Giguère (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Quebec Region), David Seburn (Seburn Ecological Services), and Scott Gillingwater (Upper Thames River Conservation Authority). Contributions from staff at the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Footnote1 Ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs, National Captial Commission, Canadian Wildlife Service, and various universities and other organizations are also gratefully acknowledged. Further, recovery documents developed by the Équipe de rétablissement des tortues du Québec and the Ontario Multi-Species Turtles at Risk Recovery Team formed the foundation for earlier drafts of this document and are gratefully acknowledged.

Acknowledgment and thanks are given to all other parties that provided advice and input used to help inform the development of this recovery strategy, including various Aboriginal organizations and individual citizens, and stakeholders who provided input and/or participated in consultation meetings.

Executive Summary

The Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii), Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population is listed as Threatened on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). The Blanding’s Turtle is semi-aquatic and uses both aquatic and terrestrial habitats. It is a medium sized turtle species with a smooth, high-domed carapace which is black to dark brown and may have yellow streaks or flecks. The most distinguishing feature of this species is its bright yellow chin and neck.

The Blanding’s Turtle is found in Canada and in the United States, with a range centred around the Great Lakes, and disjunct populations occurring in New York, Massachusetts, Maine and Nova Scotia. In Canada, the species is divided into two populations: the Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population which occurs from Ontario to southwestern Quebec, and the Nova Scotia population.

The size of the Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population, is roughly estimated to have less than 10,000 individuals, and fewer than 1,000 reproducing individuals. There is limited data on population trends, but habitat loss and fragmentation, as well as unsustainable rates of road mortality in many parts of Ontario, point to a population decline.

The main threats to this turtle are land conversion for agriculture and development, road and railway networks, human-subsidized predators and illegal collection. Other threats identified include exotic and invasive species, water management, heavy machinery, and climate change. The Blanding’s Turtle is highly vulnerable to any increases in mortality rates in adults or older juveniles since the species has delayed sexual maturity and a slow reproductive rate.

Recovery of the Blanding’s Turtle is considered feasible. The two long-term (~ 50 years) population and distribution objectives are to increase abundance and maintain, and if possible increase, the area of occupancy of the Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population in Canada, and to ensure the viability of Blanding’s Turtle local populations where they occur in Canada. The medium-term (~10-15 years) population and distribution objective is to maintain the presence of known Blanding’s Turtle local populations where they occur in Canada. The broad strategies to be taken to address the threats to the survival and recovery of the species are presented in Section 6.2 (Strategic Direction for Recovery).

Critical habitat for the Blanding’s Turtle is partially identified. Critical habitat is identified based on two criteria: habitat occupancy and habitat suitability. A schedule of studies to complete the identification of critical habitat has been included, along with examples of activities likely to destroy critical habitat.

One or more action plans will be completed for the Blanding’s Turtle and posted in the Species at Risk Public Registry by 2021.

Recovery Feasibility Summary

Based on the following four criteria that Environment Canada uses to establish recovery feasibility, recovery of the Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population, is determined to be feasible.

- 1. Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance.

- Yes. There are individuals capable of reproduction remaining across the species’ range. The Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population occurs around the Great Lakes in southern Ontario and extends northwest towards the Chippewa River and east into the southwesternmost portion of Quebec (COSEWIC 2005). A rough population estimate indicated that less than 10,000 individuals and 1,000 reproducing individuals exist within this range (COSEWIC 2005).

- 2. Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

- Yes. Although many of the habitats used by the Blanding’s Turtle have been lost and/or degraded as a result of industrial, urban and agricultural development, as well as water management, sufficient suitable habitat remains available within the Canadian range or could be made available through management and restoration to support the species. Management and restoration techniques could be used to increase the amount of suitable habitat available for the species and increase connectivity between suitable habitat patches.

- 3. The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

- Yes. The primary threats to the species include land conversion for agriculture and development, road and railway networks, human-subsidized predators and illegal collection. It is likely possible to mitigate or avoid loss of individuals as well as habitat loss and degradation through implementation of best management practices (e.g. for water control structure operation, forestry operations, and crop harvesting), habitat conservation and restoration, outreach, legislation, and enforcement.

- 4. Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable time frame.

- Yes. Recovery techniques such as habitat conservation through land acquisition, regulations, zoning, and landscape planning, along with stewardship techniques have been used successfully in some populations (Seburn and Seburn 2000). Some best management practices have been developed, and it is likely that others could be developed and tested in a reasonable time frame and implemented to help conserve vulnerable populations from habitat loss and degradation and loss of individuals. Public awareness and educational materials have been developed and will continue to be an integral part of the recovery of this species. Techniques such as utilizing nest cages to reduce nest predation, and ecopassages to mitigate road mortality have been successfully implemented to mitigate threats to the species in certain areas (Seburn and Seburn 2000).

1. COSEWICFootnote* Species Assessment Information

- Date of Assessment:

- May 2005

- Common Name (population):

- Blanding's Turtle (Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population)

- Scientific Name:

- Emydoidea blandingii

- COSEWIC Status:

- Threatened

- Reason for Designation:

- The Great Lakes/St. Lawrence population of this species although widespread and fairly numerous is declining. Subpopulations are increasingly fragmented by the extensive road network that crisscrosses all of this turtle’s habitat. Having delayed age at maturity, low reproductive output and extreme longevity makes this turtle highly vulnerable to increased rates of mortality of adults. Nesting females are especially susceptible to roadkill because they often attempt to nest on gravel roads or on shoulders of paved roads. Loss of mature females in such a long-lived species greatly reduces recruitment and long-term viability of subpopulations. Another threat is degradation of habitat from development and alteration of wetlands. The pet trade is another serious ongoing threat because nesting females are most vulnerable to collection.

- Canadian Occurrence:

- Ontario, Quebec

- COSEWIC Status History:

- Designated threatened in May 2005.

2. Species Status Information

Only the Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population, is considered in this recovery strategy; a separate recovery strategy has been prepared for the Nova Scotia population. Approximately 20% of the global range of this species is found in Ontario and Quebec (COSEWIC 2005).

The Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population, has been listed as Threatened Footnote2 in Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA) since 2005. In Ontario, the species has been listed since 2008 as Threatened Footnote3 under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (S.O. 2007, c. 6) (ESA 2007). The Blanding’s Turtle habitat is described and receives general protection under the Endangered Species Act, 2007. The Blanding’s Turtle is also designated as a Specially Protected Reptile under the Ontario Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act. In Quebec, it has been listed as Threatened Footnote4 under the Act Respecting Threatened or Vulnerable Species (ARTVS) (CQLR, c. E-12.01) since 2009. The Blanding’s Turtle is listed in Appendix II of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), which controls the trade of this species (and allows trade of a listed species only if an export permit is granted). In 2010, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) evaluated the status of the Blanding’s Turtle as Endangered Footnote5 (IUCN 2014). Another status evaluation was provided by NatureServe in 2005: the global status of the Blanding’s Turtle is Apparently Secure Footnote6 (G4) (NatureServe 2013). It is Nationally Vulnerable Footnote7 (N3) in Canada and Nationally Apparently Secure (N4) in the United States. The species is considered Critically Imperiled Footnote8 (S1) in Quebec and Vulnerable (S3) in Ontario.

3. Species Information

3.1 Species Description

The Blanding’s Turtle is a medium-sized freshwater turtle (15–27 cm carapace length) with a smooth high-domed carapace (upper shell), generally black to dark brown in colour, with yellow or tan streaks and/or flecking (Ernst and Lovich 2009; COSEWIC 2005). The plastron (lower shell) is yellowish with black markings at the back outer edge of each scute (plates on the shell/plastron) (Ernst and Lovich 2009), and have a functional hinge between the pectoral and abdominal scutes (COSEWIC 2005). There is sexual dimorphism Footnote9 in the plastron and tail, males having a slightly concave plastron and a larger tail with the vent extending beyond the edge of the carapace, while females have a fairly flat plastron and a narrower tail with the vent anterior to the edge of the carapace. They have a distinctive yellow chin, with a dark brown or black head that can be lighter in females (COSEWIC 2005; Ernst and Lovich 2009). Hatchlings differ in colouration from adults, with grey, brown or black carapaces. Hatchlings also tend towards brighter chins and throats, and a non-functioning hinge. Young Blanding’s Turtles have a plastron with a black centre and yellow outer edge, and they have a tail that extends farther past the carapace than in an adult (COSEWIC 2005).

The species has been known to live over 75 years (References removed). In the northern portions of its global range, the Blanding’s Turtle can take up to 25 years to reach sexual maturity, which makes it one of the latest maturing turtle species in Canada (References removed).

3.2 Population and Distribution

The range of the Blanding’s Turtle (Figure 1) extends from central Ontario and southwestern Quebec in the north, west to Minnesota and Nebraska and south to central Illinois to New York State in the east, with disjunct populations occurring in southeastern New York, eastern New England (Massachusetts to southern Maine), and Nova Scotia (Ernst and Lovich 2009; NatureServe 2013).

The Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population, occurs around the Great Lakes in southern Ontario and extends northwest towards the Chippewa River and east into the southwesternmost portion of Quebec (COSEWIC 2005). Some isolated records have been identified as far north as 48.48º in latitude (Crowley pers. comm. 2014). Isolated observations have been recorded in Bruce County (Ontario) in recent years, however, a local population has not yet been confirmed in this region (Crowley pers. comm. 2014). In Quebec, the bulk of the observations are concentrated in the Outaouais region, with a few other observations in the Montérégie, Abitibi, and Capitale-Nationale regions (Reference removed).

The size of the Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population, is not known, though an extremely crude estimate of less than 10,000 individuals and 1,000 reproducing individuals was suggested in the Assessment and Update Status Report (COSEWIC 2005). There is also limited data on population trends, but habitat loss and fragmentation within its range in southern Ontario and southwestern Quebec, as well as unsustainable rates of road mortality in many parts of Ontario, point to a population decline (References removed; Crowley pers. comm. 2014). Annual nest survivorship as low as 5% has been observed in parts of Ontario, which limits the population’s capacity to stabilize in the presence of other sources of mortality (COSEWIC 2005; Gillingwater pers. comm. in COSEWIC 2005).

This map represents the general range of the species, and does not depict detailed information on the presence and absence of observations within the range. Please refer to the text for further details on the distribution of the species in Ontario and Quebec.

Long Description for Figure 1

Figure 1 represents a map of the range of Blanding’s Turtle in North America. The range extends from central Ontario and southwestern Quebec in the north to central Illinois in the south. It includes Minnesota, Iowa, and central Nebraska in the west and extends east to New York State. Disjunct populations occur in southern Quebec, southeastern New York, eastern New England (Massachusetts to southern Maine), and Nova Scotia.

The extent of occurrence Footnote10 of the Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population, is approximately 73 800 km2 (COSEWIC 2005), and the area of occupancy Footnote11 is estimated at less than 835 km². Both the extent of occurrence and the area of occupancy are noted to be in decline. As of 2014, provincial Conservation Data Centres hold a total of 7157 Blanding’s Turtle records (2013 in Ontario, 5144 in Quebec), which are distributed among 248 element occurrences Footnote12 (CDPNQ 2014; NHIC 2014). In Ontario, there are a total of 213 element occurrences (139 extant, 74 historic), while there are 35 in Quebec (29 extant, 6 historic). In Ontario, increased survey efforts have resulted in the collection of over 6000 observation records available from NHIC, which have not yet been formally assessed using NatureServe methodologies. These new observations will likely result in the establishment of new element occurrences and/or modifications to existing element occurrences.

3.3 Needs of the Blanding's Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence Population

General Habitat Needs

The Blanding’s Turtle is a semi-aquatic species. Footnote13 Although it spends most of its time in aquatic habitats, it has seasonal movement patterns which allow it to meet different biological or behavioural needs, including use of terrestrial habitats during the active season (Reference removed). Habitat use varies as a function of the different activities undertaken by individuals to complete their life cycle. Blanding’s Turtles use aquatic habitats for overwintering, mating, foraging, thermoregulation, summer inactivity, and movement. They often favour relatively eutrophic Footnote14 environments, with shallow water (less than 2 m deep), soft organic substrate, and abundant submergent, floating, and emergent vegetation (References removed; Ernst and Lovich 2009). They can occur in a variety of wetland habitats (e.g., marshes, ponds, swamps, bogs, fens, coastal wetlands) (References removed), slow flowing rivers and creeks, pools, lakes, bays, sloughs, marshy meadows, and artificial channels (Reference removed). Blanding’s Turtles have been shown to select all wetland types over lotic environments and have also shown a preference for ponds and marshes when available (References removed). In Quebec, Blanding’s Turtles mainly occupy wetlands which are maintained by a complex of beaver dams (Reference removed). While large permanent wetlands can support a larger number of individuals, small and/or temporary wetlands (e.g. vernal pools) are also important habitat features (Reference removed; Grgurovic and Sievert 2005). Weather conditions can affect the availability of aquatic habitats through changes in water levels. For example, (Reference removed) showed shortened usage of vernal pools in springs in which they dried out early.

Terrestrial habitat is important for many activities of the Blanding’s Turtle during the active season, including nesting, thermoregulation, summer inactivity, and movement. Upland forest is an important habitat feature for the Blanding’s Turtle, and has been shown to be a strong predictor of its presence in a landscape (Reference removed). Other natural terrestrial habitat used by Blanding’s Turtles includes shoreline areas such as sand bars, beaches, rocky outcrops, open fields, forest clearings, and meadows (Joyal et al. 2001; Beaudry et al. 2010; Baker and King 2012). Blanding’s Turtles can also use or move through human-altered habitats, generally open areas, such as agricultural fields, road shoulders, and quarries.

Blanding’s Turtle adults and hatchlings have been shown to use similar habitat. An important difference is that hatchlings make more extensive use of open terrestrial habitat in the fall, from emergence until overwintering (Reference removed).

Overwintering

To protect themselves from freezing, Blanding’s Turtles overwinter in underwater sites from approximately October to April (References removed). Overwintering sites are generally located within permanent wetlands (e.g., bogs, fens, marshes) and other habitats with unfrozen shallow water (Joyal et al. 2001; References removed). This species may also overwinter within temporary wetlands adjacent to more permanent water bodies (Reference removed), graminoid Footnote15 shallow marsh areas of larger wetlands (Gillingwater unpublished data 2013), non-vegetated vernal pools (References removed), roadside ditches or small excavated areas with standing water (Joyal et al. 2001; Reference removed), and road-side borrow pits (Reference removed). Individuals choose sites that are cold, thermally stable, and provide 7 to 50 cm of free water, along with a soft organic substrate in which they partially bury (Reference removed). Based on its micro-environment while overwintering, the Blanding’s Turtle is believed to be anoxia-tolerant, i.e. it can survive at low concentrations of dissolved oxygen (Ultsch 2006; Reference removed). Preliminary data from Reference removed also indicate that hatchlings could overwinter on land; however this requires further investigation. This species may hibernate in groups or alone (References removed), and fidelity Footnote16 to overwintering areas was observed, which suggests that availability of overwintering sites might be limiting (References removed).

Mating

Blanding’s Turtles generally mate prior to and right after overwintering, more precisely from the end of April to early May, and from the end of August to the end of October (Reference removed; Newton and Herman 2009; Équipe de rétablissement des tortues du Québec unpublished data 2012). Mating activity mainly occurs when turtles are aggregated in the vicinity of their hibernation site (Reference removed). They have also been observed mating during overwintering (Newton and Herman 2009). Breeding behaviour takes place in shallow or deep water, and has been observed in permanent and ephemeral wetlands (Grgurovic and Sievert 2005). In Quebec, six individuals have been observed mating more than once before and/or after hibernation, with one or multiple partners (Équipe de rétablissement des tortues du Québec unpublished data 2012). The observed mating behaviour indicates that polyandry Footnote17 and sperm storage might be part of the reproductive strategy of the Blanding’s Turtle in Canada, as described by (References removed) for local populations in the United States.

Nesting

In Ontario and Quebec, nesting activity in the Blanding’s Turtle has been observed from the last week of May to the first week of July, with peak activity throughout June (Équipe de rétablissement des tortues du Québec unpublished data 2012; Trute pers. comm. in COSEWIC 2005). This species typically nests in relatively open areas such as beaches, shorelines, meadows, rocky outcrops, and forest clearings, as well as in a variety of human-altered sites such as gardens, power line rights-of-way, fields, gravel roads, and road shoulders, sand/gravel quarries, railway rights-of-way, cycling paths, hiking trails, and all-terrain vehicle (ATV) trails (References removed; Kiviat 1997; Reference removed; Joyal et al. 2001; Reference removed; Beaudry et al. 2010; Dowling et al. 2010; References removed). Nesting in open areas raises the mean incubation temperature in the nest cavity, which increases the likelihood of a successful nest (COSEWIC 2005). Females often show high fidelity to the same general nesting areas (75% in Quebec) (References removed). In Quebec, females rely heavily on human-altered sites as they provide adequate nesting substrate, and 90% of nests were found at those sites during a telemetry survey (Reference removed). However, this preference for disturbed sites could be an ecological trap, as they are associated with lower nesting success and higher mortality rates in females (Reference removed; COSEWIC 2005).

Blanding’s Turtles typically nest in the general vicinity of a wetland that is either used as summer habitat for all or part of the active season (e.g. permanent wetland), or as staging habitat used only during the nesting period. Females might use small wetlands and vernal pools as staging areas to rehydrate and feed (Grgurovic and Sievert 2005). Reported average distances between nests and the nearest wetland range from 99.5 to 242 m, with maximum distances of 256 m to 721 m (Joyal et al. 2001; Beaudry et al. 2010; Reference removed; Équipe de rétablissement des tortues du Québec unpublished data 2012; References removed). Blanding’s Turtles often travel long distances to seek out suitable nesting habitat, marking the importance of staging habitat that females use during nesting forays, and sometimes even after nesting (Fortin, pers comm. 2014). Individuals have been observed nesting up to 6 km from their wetland of origin, with a mean distance of 0.9 km observed in Ontario and Quebec (References removed). In Canada, hatchlings generally emerge throughout September and October (References removed).

Thermoregulation

Blanding’s Turtles use habitats that provide a number of basking sites (COSEWIC 2005), which they use to regulate their body temperature. End of April and May correspond to peak basking activity in Ontario and Quebec, after which turtles were found to bask less often (References removed; Équipe de rétablissement des tortues du Québec unpublished data 2012). Peak activity coincides with emergence from hibernation, a time when water temperature is low and when individuals can benefit from increased energy gain through basking (Dubois et al. 2009). During this peak, Blanding’s Turtles can often be found basking at the water surface, which also gives them an opportunity to forage (References removed). Other aquatic basking sites include muskrat and beaver lodges, stumps, piles of driftwood, submerged logs, rocks, bog mats, or shallow water surrounding emergent vegetation and root masses (Reference removed; Ernst and Lovich 2009; Reference removed; Gillingwater pers. comm. 2012). In addition to using basking sites within the aquatic habitat, this species may bask on open shoreline areas with full or partial sunlight (Joyal et al. 2001). Blanding’s Turtles may also bask in open areas while travelling over land through upland wooded areas (Joyal et al. 2001). Gravid Footnote18 females were found basking more often than males and non-gravid females, which promotes the development of eggs (References removed).

Foraging

Many important food items are found in aquatic habitat with an abundance of submerged vegetation and filamentous algae (COSEWIC 2005; Reference removed). Adult Blanding’s Turtles are primarily carnivorous and will consume anything from crayfish, worms, leeches, snails, slugs, frogs, and fish, to insects (References removed; Ernst and Lovich 2009). Small wetlands and vernal pools can be important foraging sites as they provide concentrated food sources, such as amphibian and insect egg masses and larvae (Grgurovic and Sievert 2005). Juveniles prefer to forage in areas that contain thick aquatic vegetation (e.g., sphagnum, water lilies, and algae); these areas provide refuge, decreasing the potential of predation, which is high due to their small size, as well as provide sufficient foraging opportunities (COSEWIC 2005).

Summer Inactivity Footnote19

In some parts of its range, including Quebec and Maine, upland terrestrial habitat, in addition to wetland habitat, can be used by this species for late summer inactivity from July through September (Joyal et al. 2001; Reference removed), although this has not been observed during studies in Ontario (Reference removed). In Quebec, individuals were found to be inactive for a maximum of 10 days, spending these inactive periods either upland buried under litter or in a wetland (Reference removed).

Movement (Commuting and Dispersal) Footnote20

Blanding’s Turtles regularly move between different aquatic and terrestrial habitat types to access recurrently or seasonally required resources (e.g. nesting and overwintering sites, food items). As a result, it is important that the different habitats that they use are linked, or in reasonable proximity to one another so that individuals can move between them with ease to carry out all specific life stages. Natural habitat linkages available to the Blanding’s Turtle allow access to resource patches (i.e., commuting). They also favour immigration and emigration (i.e., dispersal), which in turn allows for the rescue effect Footnote21 and increase gene flow, thereby helping to maintain genetic diversity and the species’ subsequent resilience in the face of environmental stressors.

Aquatic movement can occur in a variety of habitats, including wetlands, streams, rivers, lakes, and channels. In parts of the Ontario range, individuals travel between coastal wetlands through rivers and waterways (COSEWIC 2005). It has been hypothesized that Blanding’s Turtles prefer upland forest to open habitats for movement on land, thus access to resources could be facilitated in forested landscapes (Reference removed). Composition of the landscape (e.g. proportion of wetland and agriculture) seem to have little influence on movements (Fortin et al. 2012), but the presence of roads can modify movement patterns and act as a partial barrier to movement of some individuals (Reference removed). Natural barriers to movement include large lakes (e.g. the Great Lakes), fast-flowing rivers, and mountain ranges (COSEWIC 2005).

The home range size and length of the Blanding’s Turtle vary greatly among individuals of a region and among different regions as well. Observed home range size in Ontario and Quebec averaged between 12 and 60 ha, with a maximum of 173 ha (References removed). The same studies reported average home range lengths between 0.8 km and 3.2 km, and a maximum of 7.4 km (Reference removed). (Reference removed) observed that home range size was higher in individuals tracked for multiple years, indicating that the home range’s location can move from one year to another. However, the same study reported that Blanding’s Turtles showed fidelity to at least a portion of their home range.

Longer movements have been observed after emergence (May), with females moving more in June due to their nesting forays (References removed). Individuals have been noted to use up to 20 different wetlands per year, with average inter-wetland movement ranging between 230 and 500m (Beaudry et al. 2009; References removed).

3.4 Biological Limiting Factors

Turtles have certain common life history traits that can limit their ability to adapt to high levels of disturbance and that help explain their susceptibility to population declines (Reference removed; Gibbons et al. 2000; Turtle Conservation Fund 2002). They have a reproductive strategy that depends on high adult survival rates and extreme longevity to counterbalance the low recruitment rates because of

- late sexual maturity;

- the high rate of natural predation on eggs and juveniles under the age of two; and,

- external incubation of eggs without parental care and dependence on environmental conditions for the development of embryos.

As a consequence of these life history traits, turtle populations cannot adjust to an increase in adult mortality rates. Long-term studies indicate that high survival rates of adults (particularly adult females) are critical for maintaining turtle populations. Even a 2–3% increase in the annual adult mortality rate could result in population declines (References removed; Cunnington and Brooks 1996).

The climatic ranges within which this species can survive limit its range in northern areas (Hutchinson et al. 1966; McKenney et al.1998). Climate plays a vital role in recruitment, as this species relies on the external environment for incubation of eggs. Incubation time constitutes a major limitation for northern turtle populations (Reference removed), as the short northern summer typically makes it possible to produce only one clutch per year and can result in nest failure in cooler years. Recruitment can vary from one year to the next depending on weather conditions, particularly during the summer. Sex determination for the Blanding’s Turtle is temperature-dependent and occurs during incubation (Ernst and Lovich 2009); therefore climate could have an impact on the ratio of males and females recruited into the population.

In Canada, local populations of the Blanding’s Turtle are at the northern limit of their range (Seburn and Seburn 2000). Blanding’s Turtles in northern populations reach sexual maturity later than their southern counterparts (COSEWIC 2005). Because the species is at the northern limit of its range in Canada, the availability of suitable nesting sites with adequate temperature conditions may constitute a limiting factor for this species.

3.5 Species Cultural Significance

Turtles play an important role in Aboriginal spiritual beliefs and ceremonies. To the First Nations peoples, the turtle is a teacher, possessing a great wealth of knowledge. It plays an integral role in the Creation story, by allowing the Earth to be formed on its back. For this reason, most First Nations people traditionally call North America “Turtle Island.” Aboriginal peoples also use the turtle shell to represent a lunar calendar, with the 13 scutes representing the 13 full moons of the year. Turtle rattles, made from turtle shells have been used in traditional ceremonies and often represent the turtle in the Creation story. Turtles also appear in other traditional stories, including the Anishinaabe stories “How the turtle got its shell” and “How the Blanding’s Turtle got its yellow chin” (Reference removed; Bell et al. 2010). In Native legends, the Blanding’s Turtle is referred to as “ the turtle with the sun under its chin” (Reference removed).

4. Threats

4.1 Threat Assessment

| Threat Category | Threat | Level of Concern Noteaof Table 1 | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severity Notebof Table 1 | Causal CertaintyNotecof Table 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat Loss, Degradation, or Fragmentation | Land conversion for agriculture and development | High | Widespread | Historic & Current |

Recurrent | High | High |

| Habitat Loss, Degradation, or Fragmentation | Water management | Low/ Medium | Localized | Current | Recurrent | Moderate | Medium |

| Accidental Mortality | Road and railway networks | High/ Medium | Widespread | Current | Seasonal | High | High |

| Accidental Mortality | Heavy machinery | Low | Localized | Current | Seasonal | Unknown | Medium |

| Changes in Ecological Dynamics or Natural Processes | Human-subsidized predators | Medium | Widespread | Current | Seasonal | Moderate | Medium |

| Biological Resource Use | Illegal collection | Medium | Localized | Current | Recurrent | Moderate | Medium |

| Exotic, Invasive or Introduced Species | Exotic and invasive species | Medium/ Low | Localized | Current & Anticipated | Continuous | Moderate | Medium |

| Climate and Natural Disasters | Climate change | Low | Widespread | Current & Anticipated | Continuous | Unknown | Low |

4.2 Description of Threats

This section describes the threats outlined in Table 1, emphasizes key points, and provides additional information. Although threats are listed individually, an important concern is the long-term cumulative effect of such a variety of threats on Blanding’s Turtle local populations. It should be noted that some threats apply only during the active season (generally April to October) since they lead to direct mortality or mutilation of individuals. Moreover, exposure to threats increases in periods in which Blanding’s Turtles are more mobile (e.g., emergence from hibernation, nesting), when individuals move between habitat patches and females do long nesting forays. Among mechanisms through which threats can impact Blanding’s Turtles local populations, isolation through habitat loss and fragmentation is of special concern, as it leads to a breakdown of metapopulation dynamics and limits the possibility of the rescue effect. Threats are listed in overall decreasing order of level of concern.

Land conversion for agriculture and development (e.g. industrial, urban, rural, shoreline)

Conversion of suitable aquatic and terrestrial habitats to agriculture and development is a significant threat to the Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population. Land conversion (for agriculture, industrial activities, residential and commercial development, etc.) implies that natural habitats are permanently altered to fill a new function. Land conversion includes the draining or infilling of wetlands and the development of upland habitats, which results in loss or degradation of suitable habitat patches. Elimination of occupied wetlands forces Blanding’s Turtles to move to other aquatic habitats, exposing them to other threats (e.g. road and railway networks, heavy machinery), and can lead to the use of lower quality habitat. Wetlands in southern Ontario and Quebec have undergone major development since the early 1800s, restricting the access of Blanding’s Turtles to suitable habitats and compromising the sustainability of the Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population (COSEWIC 2005).

Conversion of upland areas surrounding aquatic habitats can eliminate important nesting sites and areas used for thermoregulation, summer inactivity, and movement. The alteration of features along the shoreline (e.g. nesting sites, basking sites) can impact Blanding’s Turtles, especially for local populations inhabiting coastal wetlands. Terrestrial habitats modified by human activity may remain occupied, and increased availability of open nesting habitats may attract individuals to disturbed areas. The creation of nesting habitat (e.g. quarries) through land conversion is, however, considered a potential ecological trap, as disturbed areas are often associated with increased predation or encounters with heavy machinery and vehicles (Reference removed). The Blanding’s Turtle is more present in forested landscapes, and thus deforestation can make the landscape less suitable for populations to thrive (Reference removed). Large-scale forestry operations (e.g. clear-cutting), although their effects are temporary, can alter the habitat of the Blanding’s Turtle in a way similar to deforestation, eliminating shelter (e.g. shrub cover) available to individuals, and reducing habitat suitability in early successional stages.

Land conversion fragments habitat patches (both aquatic and terrestrial), which isolates local populations, reduces genetic variation, and increases the risk of death during travel through inhospitable areas. Densely urbanized areas are considered a barrier to movement because they lack suitable habitat for turtles to use (NatureServe 2013), isolating local populations and limiting a potential rescue effect from other local populations (COSEWIC 2005). Some research has found that turtles are less abundant in more isolated wetlands (Marchand and Litvaitis 2004a). One study has shown that small populations of Blanding’s Turtles may be genetically diminished in comparison with larger populations (Reference removed). This may be because reduced ability for successful dispersal of individuals can result in a loss of genetic variation (Gray 1995). Loss of genetic variation in small, isolated populations can in turn cause a loss of population fitness and adaptability, and increase the risk of extinction in the wake of a catastrophic event or epidemic Footnote22 (Frankham 1995; Reed and Frankham 2003).

Road and railway networks

Given that Blanding’s Turtles move long distances on land (COSEWIC 2005; Beaudry et al. 2008; Reference removed), where they are relatively slow, mortality resulting from collision with vehicles is of concern for this species. This is especially true where roads run through or near wetlands, and are heavily travelled. In less urbanized areas, trail networks and forestry roads put Blanding’s Turtles at risk of being crushed by ATVs and trucks (Newton and Herman 2009). Females are more often encountered on roads than males (Steen et al. 2006) because they can move long distances on land during the nesting season (References removed), may use road shoulders of paved and unpaved roads to nest (e.g. References removed), or may nest directly on unpaved roads and ATV trails. The creation of roads and trails may attract Blanding’s Turtle females in search of a suitable nesting substrate (e.g. bare ground). Expansion of road networks near occupied habitat may create new nesting locations; however, these are likely to act as ecological traps because of the increased collision risk associated with such locations. Increased mortality rates in females may result in a male-biased sex ratio of turtle populations in wetlands surrounded by a dense road network (Marchand and Litvaitis 2004a; Reference removed; Gibbs and Steen 2005). Loss of adult females is especially harmful to Blanding’s Turtle local populations given the species’ reproductive strategy (extreme longevity, low recruitment rates). Nests and emerging hatchlings can be crushed by vehicles, especially for clutches laid on unpaved roads and trails. Nests and individuals also risk being crushed by off-road vehicles at sites that are used recreationally, e.g. sand/gravel pits and quarries. Maintenance of roads and trails can pose a threat to individuals and nests when grading and vegetation removal/control is required throughout the summer and autumn. Cleaning ditches can expose turtles during overwintering, weakening and potentially killing individuals.

In addition to causing direct mortality, roads also remove suitable habitat, alter adjacent areas and hydrological patterns, and subdivide local populations. Highways with heavy traffic or that are built in such a way that they impede the movement of individuals are considered barriers to movement (NatureServe 2013; Reference removed). Expansion of the road network is associated with increased mortality and reduced gene flow between local populations, contributing to their isolation and limiting a potential rescue effect from surrounding local populations (COSEWIC 2005).

In Ontario, the road network is developing rapidly, especially in the southern portion of the province, where the length of major roads has increased by 28 000 km within 60 years (Fenech et al. 2005). Road mortality is of major concern in this province and road sections with high mortality rates of freshwater turtles have been identified in many areas, including national and provincial parks (Reference removed; Crowley and Brooks 2005; Ontario Road Ecology Group 2010; Crowley pers. comm. 2014). In Quebec, the area occupied by the Blanding’s Turtle is fragmented by an extensive road and trails network, with many ATV trails at known occupied sites (Reference removed). Data from telemetry surveys and opportunistic observations seem to indicate that road mortality rates are not high, but a few road sections within the study area were identified as problematic (Reference removed). Even low mortality rates can be detrimental to Blanding’s Turtle local populations, given their sensitivity to increased adult mortality (see Section 3.4). Mitigation measures that have shown to reduce road mortality in turtles include the creation of ecopassages (e.g. culverts) along with exclusion fencing (Reference removed; Ontario Road Ecology Group 2010). Baxter-Gilbert et al. (2015) suggest that the effectiveness of ecopassages is compromised when turtles can use alternative routes (e.g. incomplete fencing), showing the importance of careful design in the development of mitigation measures.

Railways cause mortality in Blanding’s Turtles through encounters with trains and cars. Individuals can also remain trapped between two rails and die from dehydration (References removed). A study of Terrapene carolina showed that turtles often have difficulty escaping when trapped between railway tracks even if their size allows them to escape (Kornilev et al. 2006). Captivity in these conditions leads to an increase in internal body temperature to a point where it reaches critical values, even at normal summer air temperatures (below 25 Celsius). In Quebec, 3 of 13 dead Blanding’s Turtles found opportunistically between 2009 and 2011 were found dead on a railway crossing a wetland. Many turtle bones and dried out carapaces were found along the same railway, but the species could not be identified. Similar to the road network, railways contribute to the removal and fragmentation of suitable habitat, and to the isolation of Blanding’s Turtle local populations.

Illegal collection

Worldwide, many turtle species are impacted by both casual and large-scale systematic illegal collection for use as pets, food, and traditional medical remedies (Bodie 2001; References removed). The export rate of freshwater turtles, for both pet and food trades, is high in the U.S. (Mali et al. 2014), and can be expected to also be high in Canada given lucrative trade demand. Perversely, reptile species are more likely to be involved in the international pet trade if they are categorized as at risk than if they are not considered at risk (Bush et al. 2014), consistent with a general demand for rare wildlife (Courchamp et al. 2006). Although it is unclear whether harvesting of turtles for food is a widespread practice in Canada, humans are known to consume a number of turtle species (Thorbjarnarson et al. 2000; Reference removed). Each year, thousands of turtles are sold in Asian food markets in North America or are exported from the United States to Asia.

The illegal collection of Blanding’s Turtles removes individuals from all age classes from the population which, given the species’ reproductive strategy (extreme longevity, low recruitment rates), may greatly reduce recruitment (COSEWIC 2005). Adult females are easier to locate and catch because they sometimes aggregate at easily accessible sites to nest (e.g. road shoulders, beaches) and show strong fidelity to their nesting sites. They are also more sought after as they might provide eggs (COSEWIC 2005). The extent of the illegal organized turtle harvest is poorly documented in Canada for the Blanding’s Turtle, but captive-bred individuals have been found for sale online and a case of illegal harvesting of Blanding’s Turtles in Ontario, which resulted in fines being laid under SARA, was reported in the Chatham Daily News (2008). In 2014, two Canadian men were arrested for smuggling and illegally trading and exporting reptiles, including Blanding’s Turtles (The Detroit News 2014). It appears that an organized trading network involving thousands of turtles was in place.

Human-subsidized predators

In many areas, the low density or absence of top predators and increased food availability from human sources (e.g. food handouts, garbage, crops) have led to a greater abundance of turtle predators than natural conditions would have historically supported (Mitchell and Klemens 2000). Main predators of the Blanding’s Turtles include raccoons, skunks, opossums, foxes, domestic and feral dogs and cats, coyotes, and some birds (e.g. crows and ravens). The abnormally high level of many predator populations can lead to very high rates of predation, especially on eggs and hatchlings. Predation rates on nests can be higher at human-altered sites (e.g. roadsides) where opportunistic nest discovery is facilitated, and at sites where nests are clustered (Marchand and Litvaitis 2004b; Reference removed). Predators can also feed on juvenile turtles and injure adults, although adults are less preyed upon (COSEWIC 2005). Individuals are more susceptible to predation when they are travelling on land, for example dispersing juveniles or females during nesting forays.

Elevated predation by raccoons has been identified as a likely cause of low recruitment and a shifting size/age structure of Blanding’s Turtle populations at a site on Lake Erie, Ontario (Reference removed). Predation rates on turtle nests between 80 and 100% has been observed at this location (References removed). In Quebec, 12% of the 113 Blanding’s Turtles captured between 2009 and 2011 had a partially missing limb or tail (Reference removed); predation is believed to be a probable cause of those injuries (along with other possible causes). Methods to deal with elevated predation rates (e.g. use of fencing and nest boxes) have been developed and used with varying degrees of success (Reference removed).

Water management

Any alteration of the natural water regimes of wetland complexes can result in the temporary or permanent loss or degradation of aquatic habitat for the Blanding’s Turtle. Modifications in the water level of aquatic habitat can also lead to changes in the characteristics of surrounding terrestrial habitat (e.g. soil humidity, vegetation structure), potentially removing suitable nesting and basking sites. In Quebec, the habitat of the Blanding’s Turtle is largely composed of wetland complexes maintained by beaver dams (Reference removed). The dismantling of dams to avoid overflow (on roads, buildings, agricultural fields, etc.) and natural damage to dams have been observed at many locations in the Outaouais region, causing the water level to rapidly decrease in occupied wetlands (Reference removed). Partial draining of wetlands reduces the area available to Blanding’s Turtles for foraging and can remove suitable overwintering sites. Moreover, draining wetlands below a certain level makes the habitat unsuitable for Blanding’s Turtles, forcing individuals to move to other habitat patches (Reference removed). Searching for new suitable habitat forces individuals to use terrestrial habitat, thus exposing them to other threats such as accidental mortality on roads and predation. Dismantlement of dams close to or during hibernation could expose individuals to low fall or winter temperatures or force them into using less suitable hibernacula, which could weaken or kill individuals. Permanent structures to control the water level in wetlands maintained by beaver dams have been used in portions of the range, and have been shown to successfully avoid overflow on infrastructure without causing habitat destruction (Cook and Jacob 2001). In managed wetlands maintained by artificial dams (e.g. waterfowl projects), adequate control of the water level is necessary to avoid draining or filling them to the point where habitat features are no longer suitable for the Blanding’s Turtle (e.g. deep water with little vegetation). It has been hypothesized that the movement of individuals across the Ontario–Quebec border is limited due to damming for hydroelectricity (COSEWIC 2005), thereby isolating local populations.

Exotic and invasive species

The introduction of invasive exotic plants can affect the makeup of wetland communities and alter habitat availability and quality for Blanding’s Turtles. In some areas, particularly around Lake Erie, Lake Huron, and Lake St. Clair, and along some major rivers, European Common Reed (Phragmites australis ssp Paustralis) has invaded wetlands, forming a monoculture that has altered conditions and decreased habitat quality for Blanding’s Turtles and other turtle species (COSEWIC 2005; Gillingwater pers. comm. 2012). The expansion of the road network also facilitates the spread of invasive plant species, especially in southern Ontario (Gelbard and Belnap 2003). Blanding’s Turtles nest in open, unshaded areas receiving adequate solar heat. In a study conducted at a site on Lake Erie, Ontario, it was found that European Common Reed had reduced the amount of suitable nesting habitat, because the plant’s growth altered the microenvironment (particularly temperature) of turtle nests during the incubation period (Reference removed). Other invasive species might have an impact on the Blanding’s Turtle and its habitat, including the Rough Mannagrass (Glyceria maxima), the Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio), and exotic pets such as the Red-eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans). For example, a recent study suggests that the Red-eared Slider can outcompete native freshwater turtles for limited food resources (Pearson et al. 2015). More information on the direct impacts on the turtle population is necessary to understand the level of threat each invasive species poses to the Blanding’s Turtle.

Heavy machinery

Commercial and industrial activities that involve the use of heavy machinery pose a direct threat to Blanding’s Turtles. Encounters with machinery may cause death or mutilation of individuals, including hatchlings and juveniles. The mutilations of limbs may reduce mobility, while shell damage may directly inhibit or restrict growth (Saumure and Bider 1998). Activities involving the manipulation of debris (e.g. logging residue) and soil can lead to individuals being buried or crushed under substrate and debris. Individuals may also be extracted from hibernacula during clearing/excavation in or close to aquatic habitats. At nesting locations, machinery can destroy nests by running over them or by moving the substrate. Forest harvesting and construction of logging roads involve the manipulation of soil and logging residue with machinery, which can be detrimental to individuals during overland movement and summer inactivity. Blanding’s Turtles are known to use habitat in Ontario’s Areas of the Undertaking, Footnote23 putting them at risk from forestry operations. Blanding’s Turtles often use human-altered habitats with bare ground to nest (e.g. power line right-of-ways, agricultural land) and can also use such sites opportunistically while travelling overland. Blanding’s Turtles have been found in agricultural fields, sand and gravel pits, power line rights-of-way, as well as opencast mines (COSEWIC 2005; Reference removed; Fortin pers. comm. 2014), where heavy machinery operate (e.g. tractors, hay mowers, backhoes). At human-altered sites, encounters with heavy machinery are possible throughout the whole active season; however, Blanding’s Turtles are more at risk of being killed or harmed by machinery from the beginning of the nesting season until hatchlings have emerged and have moved to aquatic habitats. In Quebec, 14 out of 31 Blanding’s Turtle females tracked by telemetry nested in agricultural fields and quarries, most of which were in operation (Équipe de rétablissement des tortues du Québec unpublished data 2012). In total, 27% out of 113 Blanding’s Turtles captured during this study had plastron and carapace injuries (including deep cuts in the carapace) or a partially missing limb or tail, a portion of which could be attributed to an encounter with mechanical equipment (along with predation) (Reference removed).

Climate change

Climate change is expected to affect recruitment rates in Blanding’s Turtles as well as availability of suitable aquatic habitat. An increase in the annual average temperature in Ontario of 2.5 to 3.7ºC by 2050 (compared to 1961–1990) is expected, along with changes in seasonal precipitation patterns (Expert Panel on Climate Change Adaptation 2009). Hydrological effects could be marked by lower water levels during summer (Lemmen et al. 2008). Higher temperatures and increased evaporation could lead to low runoff (Expert Panel on Climate Change Adaptation 2009) and dry out wetlands that were once permanent. There is evidence that periods of drought can cause massive inter wetland migrations in freshwater turtles (Reference removed), which puts them more at risk of accidental mortality (especially on roads). Blanding’s Turtles are considered among the reptiles in the Great Lakes region most sensitive to climate change, analyses showing a probable decrease in climatic suitability at many occupied locations (King and Niiro 2013).

Blanding’s Turtles exhibit temperature-dependent sex determination, where higher temperatures lead to the production of proportionately more females and lower temperatures lead to the production of proportionately more males (Ernst and Lovich 2009). It has been hypothesized that climate change and the anticipated increase in average temperatures could have an impact on the sex ratio of turtle populations (Janzen 1994) and on the development of embryos and hatchlings (Reference removed).

Potential threats

There are a number of other threats that potentially affect the Blanding’s Turtle, but the extent and risk of the threats are not well known at this time. For example, Blanding’s Turtles are subject to deliberate harassment and persecution by humans, including throwing rocks, shooting with firearms, and intentionally driving over them (e.g. Reference removed). Disturbance from human presence can interrupt normal behaviours (e.g. basking, feeding, nesting), resulting in possible loss of energy and increased predation risk. Translocation of turtles from one water body to another by humans may lead to increased stress and expose individuals to other threats (e.g. road and railways, predation) when they attempt to return to the area of origin or find suitable habitat (Gillingwater pers. comm. 2012). Blanding’s Turtles could also be subject to injuries and mortality from motorboat propellers and commercial fisheries in part of their range, more specifically at locations where they use coastal wetlands connected to larger bodies of water where these activities occur (Bennett and Litzgus 2014). Because Blanding’s Turtles are long-lived, they could be vulnerable to contaminant accumulation, the long-term impact of which remains poorly understood. Water quality can be degraded by runoff of contaminated water from agricultural (nutrients and pesticides) and industrial zones, roads (e.g. de-icing salt), and urban areas (heavy metals), as well as toxins released during blue-green algae blooms (Carpenter et al. 1998; Mitchell and Klemens 2000; Reference removed). In agricultural landscapes, trampling by livestock and use of stock fencing in which turtles can get caught may also threaten individuals (References removed).

5. Population and Distribution Objectives

The long-term (~50 years) population and distribution objectives are

- To increase abundance and maintain, and if possible increase, the area of occupancy of the Blanding’s Turtle, Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population in Canada.

- To ensure the viability Footnote24 of Blanding’s Turtle local populations Footnote25 where they occur in Canada.

To work towards achieving the long-term population and distribution objectives, the following medium-term sub-objective (~10–15 years) has been identified:

- To maintain the presence of known Blanding’s Turtle local populations.

According to COSEWIC (2005), continued habitat loss and fragmentation within the species range and its sensitivity to increased adult mortality point to a population decline. The goal of this recovery strategy is to reverse the population decline by addressing threats to the species through threat reduction and mitigation as well as habitat management. Threats need to be addressed taking into account their temporality and their variable severity across different regions. While studies in Quebec and Ontario have provided significant insights into habitat use and movement of the Blanding’s Turtle, there is still limited information on trends and abundance of the Great Lakes / St. Lawrence population. At most studied locations, available information consists of presence/absence data or a number of captured individuals. Thus, it will be necessary to obtain more precise baseline abundance and trend information to monitor progress towards achieving viable local populations. This long-lived species has specific ecological requirements, complex life cycle needs, and a limited ability to compensate for the loss of individuals through reproduction or through recruitment from adjacent local populations. As a result, active broad strategies and general approaches undertaken on several fronts over a long period of time and sometimes over large regions will be required to achieve these objectives. A special focus is given to maintaining areas of suitable habitat large enough for local populations to thrive. To increase abundance and area of occupancy, habitat creation and restoration are also advised where necessary and feasible.

6. Broad Strategies and General Approaches to Meet Objectives

6.1 Actions Already Completed or Currently Underway

In 2013, the Canadian Amphibian and Reptile Conservation Network (CARCNET) and the Canadian Association of Herpetologists (CAH) passed a motion to merge together to form the Canadian Herpetology Society (CHS). At the national level, the Canadian Herpetology Society is the main non-profit organization devoted to the conservation of amphibians and reptiles, including turtles, through scientific investigations, public education programs and community projects, compilation and analysis of historical data and the undertaking of projects that support conservation or restoration.

Environment Canada has been funding projects related to turtle conservation across Quebec and Ontario through the Habitat Stewardship Program (HSP) and Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk (AFSAR) since 2001 and the Interdepartmental Recovery Fund (IRF) since 2004. Projects have included activities such as: undertaking targeted surveys for the species; identifying important habitat of local populations; studying the severity of and/or mitigating threats such as road mortality; soliciting observations and encouraging public reporting of sightings; and educating landowners and/or the public on species identification, threats, and stewardship options. Some of these projects, along with those funded by the provinces and others, are described below.

Ontario

An Ontario Multi-Species Turtles at Risk Recovery Team was established in the early 2000s by a group of people interested in turtle recovery, and focused on six turtle species at risk: the Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii), the Eastern Musk Turtle (Sternotherus odoratus), the Northern Map Turtle (Graptemys geographica), the Spiny Softshell (Apalone spinifera), the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys Guttata), and the Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta). This group has coordinated and initiated a number of recovery efforts, including conducting educational and outreach programs on reptiles and various management initiatives such as nest protection projects and nest site rehabilitation projects (Reference removed).

In 2013, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry (MNRF) produced a general habitat description for the Blanding’s Turtle, which provides greater clarity on the habitat protected under the Endangered Species Act, 2007. The MNRF has funded numerous turtle conservation and stewardship projects across Ontario through the Ontario Species at Risk Stewardship Fund and other provincial funding programs. In 2010, the MNRF released the Forest Management Guide for Conserving Biodiversity at the Stand and Site Scales (The Stand and Site Guide) (OMNR 2010). This tool, designed for forest managers, provides direction on planning and conducting forest operations at the stand and site level (i.e., 10s of m2 to 100s of km2) so that forest biodiversity will be conserved, and it includes standards, guidelines and best management practices for turtles found in the Area of the Undertaking, including Blanding’s Turtles.

Since 2009, Ontario Nature has been coordinating the development of a new Ontario Reptile and Amphibian Atlas and is working with the Natural Heritage Information Centre and other organizations (Ontario Nature 2013). By soliciting occurrence records from the public, researchers, government and non-governmental organizations, this project is improving our knowledge of the distribution and status of reptiles and amphibians in Ontario, including the Blanding’s Turtle (Crowley pers. comm. 2014).

There have been several large-scale inventory, survey, and monitoring programs targeting turtles, including the Blanding’s Turtle, in Ontario, such as the Ontario Turtle Tally (Toronto Zoo), the Kawartha Turtle Watch (Trent University), initiatives of the Nature Conservancy of Canada and Ontario Nature as well as many local survey and monitoring programs (e.g. by researchers and First Nations). In addition, research has been conducted on the Blanding’s Turtle in various parts of Ontario to fill knowledge gaps, including studies on home ranges, demographics, habitat use, ecology, and threats (e.g. References removed).

Various restoration, threat mitigation, and other conservation initiatives have been undertaken in Ontario (e.g. by Parks Canada Agency within National Parks and Rouge National Urban Park, Nature Conservancy of Canada, and numerous other organizations). Notably, several organizations have been involved in the protection of nests and hatchlings and/or headstarting programs (e.g. Toronto Zoo, Parks Canada Agency, Kawartha Turtle Trauma Centre). In the context of Rouge National Urban Park’s legislated responsibility to conserve nature, culture and agriculture, Parks Canada has initiated landscape enhancement projects in collaboration with the agricultural community and other stakeholders. This approach will serve as a model for integrated habitat and farmland enhancement benefitting the Blanding’s Turtle and other species. The Kawartha Turtle Trauma Centre (KTTC) in Peterborough also rehabilitates wild turtles that were injured in the hopes of recovering and releasing them. The number of turtles that the centre treats annually is rising (KTTC 2014).

There are many organizations and agencies that offer outreach and educational programs on turtle species at risk to school groups, First Nations, and the general public (e.g., Scales Nature Park, Reptiles at Risk on the Road Project, the Georgian Bay Biosphere Reserve [and previously the Georgian Bay Reptile Awareness Program], Ontario Nature, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Ontario Parks, the Parks Canada Agency, Toronto Zoo, and the Upper Thames River Conservation Authority). The Toronto Zoo Adopt-a-Pond Wetland Conservation Program is one of several projects that have developed turtle conservation curricula for schools, while the Toronto Zoo Turtle Island Conservation Program promotes turtle conservation and awareness among First Nations and non-Aboriginal groups. Turtle SHELL (Safety, Habitat, Education and Long Life) has prepared booklets and installed turtle crossing signs.

Many projects are being carried out as a requirement under the Ontario Endangered Species Act, 2007 and are directly benefitting turtle populations. For example, turtle fencing and ecopassages are now incorporated into the design of most new highways whenever they bisect the habitat of turtle species at risk (Ontario Road Ecology Group 2010; OMNR 2013b).

Quebec

The Quebec Turtle Recovery Team was created in 2005. One of its mandates is to develop and implement a recovery plan for five species of turtles: the Wood Turtle (Glyptemys insculpta), the Northern Map Turtle (Graptemys geographica), the Blanding’s Turtle (Emydoidea blandingii), the Eastern Musk Turtle (Sternotherus odoratus) and the Spotted Turtle (Clemmys guttata) (Reference removed). This team merged in 2012 with the Spiny Softshell (Apalone Spinifera) Recovery Team, thus including a sixth species of turtle. To ensure implementation of the recovery actions, four Implementation Groups were established, each working on a specific turtle species or group of species. One of these groups is the Blanding’s Turtle and Eastern Musk Turtle Implementation Group, and is made up of partners from many organizations and independent consultants, including (over the years) the Quebec Ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs (MFFP), Environment Canada, the National Capital Commission, Nature Conservancy of Canada, Hydro-Québec, and McGill University.

An amphibian and reptile database (Atlas des Amphibiens et des Reptiles du Québec) exists and is managed by the Société d’Histoire Naturelle de la Vallée du Saint-Laurent (SHNVSL). The Atlas des Amphibiens et des Reptiles du Québec was a source database of the Centre de données sur le patrimoine naturel du Québec (CDPNQ) until 2014. The CDPNQ is held by the MFFP for data on threatened or vulnerable species, including the Blanding’s Turtle. In 2012, the CDPNQ mapped element occurrences of the Blanding’s Turtle in Quebec.

In the last decade, numerous activities have been undertaken to better understand the Blanding’s Turtle in Quebec, including surveys (References removed); research on the ecology, population structure, habitat use and habitat composition, residences and movements (References removed; Fortin et al. 2012); and research on threats such as mortalities and injuries caused by road and railway networks, and water management, more precisely alterations of beaver dams (Reference removed). A population monitoring protocol has been produced (Reference removed). In addition, a habitat conservation plan promoting beaver management that is compatible with maintaining Blanding’s Turtle habitat has been produced and is beginning to be implemented (Reference removed). A protection plan for the Blanding’s Turtle is also currently under production by the Wildlife Protection Branch of the MFFP.

Considering what is known about the distribution of the species, seven priority conservation areas were established in the Outaouais region (Reference removed). With these conservation areas, several acquisition projects have been implemented by the MFFP and partners such as Nature Conservancy Canada to conserve habitats used by the Blanding’s Turtle in Quebec. Nature Conservancy Canada has secured over 3000 ha of terrestrial and aquatic habitats used by the Blanding’s Turtle in the Outaouais region. Also, several stewardship and communication initiatives have been put forward to conserve Blanding’s Turtles and their habitat (e.g. maintenance of habitats at managed sites; distribution of brochures and pamphlets to the public; presentations in schools, at general public information days and in television and newspaper reports; and development of a web page). All these actions have been conducted by government and paragovernmental organizations, First Nations, conservation organizations, research or zoological institutions, or volunteers.

6.2 Strategic Direction for Recovery

| Threat Notedof Table 2 or Limitation |

Broad Strategy for Recovery | Priority Noteeof Table 2 | General Description of Research and Management Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| All Threats | Law and Policy | High | Enforce and promote compliance with existing laws, regulations, and policies applicable to Blanding's Turtle individuals and habitat on all types of land tenure. |

| 2, 3, 4, 5 | Reduction of Adult Mortality, Injury, and Illegal Collection | High | Identify and prioritize sites where mortality, injury and illegal collection of adults are threatening local Blanding's Turtle populations. Develop or improve, implement, and evaluate mitigation techniques (e.g. best management practices) to address threats to individuals at priority sites. Develop, implement, and evaluate a federal/provincial strategy to address illegal collection. |

| 1, 2, 5, 6 | Conservation, Management, and Restoration of Habitat | High | Identify and prioritize sites where habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation are threatening local Blanding's Turtle populations, and assess habitat restoration needs. Develop or improve, implement, and evaluate mitigation and habitat restoration techniques to address threats to habitat at priority sites. Conserve areas large enough to maintain viable populations and increase connectivity through administrative and stewardship tools. |

| All Threats | Communication and Outreach | Medium | Develop and implement communication strategies appropriate to target audiences and to major initiatives to reduce adult mortality, reduce threats and conserve habitat. Improve and maintain co-operation between stakeholders (e.g. partner agencies, First Nations, interest groups, landowners). Encourage and support the transfer and archiving of information and tools, including Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). Promote and engage partners in research initiatives necessary to fill knowledge gaps. |

| All Threats | Improvement of Recruitment where Needed | Medium | Document recruitment needs at locations where the Blanding's Turtle is declining or where the viability is deemed to be compromised. Where needed, develop or improve, implement, and evaluate techniques to reduce nest destruction and/or increase recruitment. |