Blue racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) proposed recover strategy 2017: chapter 2

Part 1 – Federal addition to the Recovery Strategy for the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) in Ontario, prepared by Environment and Climate Change Canada

Preface

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years after the publication of the final document on the SAR Public Registry.

The Minister of Environment and Climate Change is the competent minister under SARA for the Blue Racer and has prepared the federal component of this recovery strategy (Part 1), as per section 37 of SARA. SARA section 44 allows the Minister to adopt all or part of an existing plan for the species if it meets the requirements under SARA for content (sub-sections 41(1) or (2)). The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (now the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry)led the development of the attached recovery strategy for the Blue Racer (Part 2) in cooperation with Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment and Climate Change Canada, or any other jurisdiction alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Blue Racer and Canadian society as a whole.

This recovery strategy will be followed by one or more action plans that will provide information on recovery measures to be taken by Environment and Climate Change Canada and other jurisdictions and/or organizations involved in the conservation of the species. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

The recovery strategy sets the strategic direction to arrest or reverse the decline of the species, including identification of critical habitat to the extent possible. It provides all Canadians with information to help take action on species conservation. When critical habitat is identified, either in a recovery strategy or an action plan, SARA requires that critical habitat then be protected.

In the case of critical habitat identified for terrestrial species including migratory birds SARA requires that critical habitat identified in a federally protected areaFootnote1 be described in the Canada Gazette within 90 days after the recovery strategy or action plan that identified the critical habitat is included in the public registry. A prohibition against destruction of critical habitat under ss. 58(1) will apply 90 days after the description of the critical habitat is published in the Canada Gazette.

For critical habitat located on other federal lands, the competent minister must either make a statement on existing legal protection or make an order so that the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat applies.

If the critical habitat for a migratory bird is not within a federal protected area and is not on federal land, within the exclusive economic zone or on the continental shelf of Canada, the prohibition against destruction can only apply to those portions of the critical habitat that are habitat to which the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 applies as per SARA ss. 58(5.1) and ss. 58(5.2).

For any part of critical habitat located on non-federal lands, if the competent minister forms the opinion that any portion of critical habitat is not protected by provisions in or measures under SARA or other Acts of Parliament, or the laws of the province or territory, SARA requires that the Minister recommend that the Governor in Council make an order to prohibit destruction of critical habitat. The discretion to protect critical habitat on non-federal lands that is not otherwise protected rests with the Governor in Council.

Acknowledgements

The initial draft of the federal addition was prepared by Jennie Pearce (Pearce and Associates Ecological Research), and was further developed by Kathy St. Laurent, Lauren Strybos, Justine Mannion, Krista Holmes (Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario) and Bruna Peloso (formerly Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario). Rachel deCatanzaro, Liz Sauer, Lesley Dunn (Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario), Veronique Lalande, Paul Johanson (Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service - National Capital Region), Vivian Brownell, Joe Crowley, Anita Imrie and Jay Fitzsimmons (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry) reviewed and provided comments and advice during the development of this document.

Acknowledgement and thanks is given to all other parties that provided advice and input used to help inform the development of this recovery strategy including various Indigenous organizations and individual citizens, and stakeholders who provided input and/or participated in consultation meetings. Additionally, thanks are given to Rob Willson for providing the 2002 survey report and for advice in the development of this addition.

Additions and modifications to the adopted document

The following sections have been included to address specific requirements of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) that are not addressed in the Recovery Strategy for the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) in Ontario (Part 2 of this document, referred to henceforth as "the provincial recovery strategy") and/or to provide updated or additional information.

Environment and Climate Change Canada is adopting the provincial recovery strategy (Part 2), including section 2.0, Recovery; which outlines the approaches necessary to meet the population and distribution objective. Environment and Climate Change Canada has established its own population and distribution objective that is consistent with the recovery goal recommended in the provincial recovery strategy.

Under SARA, there are specific requirements and processes set out regarding the protection of critical habitat. Therefore, statements in the provincial recovery strategy referring to protection of the species' habitat may not directly correspond to federal requirements. Recovery measures dealing with the protection of habitat are adopted; however, whether these measures will result in protection of critical habitat under SARA will be assessed following publication of the final federal recovery strategy.

1 COSEWICi species assessment information

- Date of assessment:

- May 2012

- Common name (population):

- Blue Racer

- Scientific name:

- Coluber constrictor foxii

- COSEWIC status:

- Endangered

- Reason for designation:

- This large snake has an extremely restricted distribution and in Canada occurs only on Pelee Island in southern Ontario. Despite efforts to protect dwindling habitat, it remains at low numbers. Threats include loss and fragmentation of habitat, increased road mortality and persecution.

- Canadian occurrence:

- Ontario

- COSEWIC status history:

- Designated Endangered in April 1991. Status re-examined and confirmed in May 2002 and May 2012.

i COSEWIC (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada)

2 Species status information

The Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) is a subspecies of the North American Racer (Coluber constrictor). There are 11 subspecies found in North America (Crother et al. 2001) with three occurring in Canada. The Blue Racer is the only subspecies of the North American Racer found in Ontario, where it is now only found on Pelee Island in Lake Erie although historically they were also recorded on the mainland in extreme southwestern Ontario.

The historical distribution of the Blue Racer in North America was in the Great Lakes region and ranges from extreme southwestern Ontario to central and southern Michigan, northeastern Ohio, eastern Iowa, southeastern Minnesota and to southern Illinois (Conant and Collins 1998; Willson and Cunnington 2012). The Blue Racer has a global conservation rank of G5T5 with a rounded status of T5, indicating the subspecies is globally SecureFootnote2 (NatureServe 2014). The conservation rank of the Blue Racer in the United States and most states in which it is found has not been assessed; in Indiana the Blue Racer is ranked S4, Apparently SecureFootnote3 (NatureServe 2014).

In Canada, the Blue Racer has a national and subnational (Ontario) rank of Critically ImperiledFootnote4 (N1 and S1, respectively) (NatureServe 2014). It is listed as EndangeredFootnote5 on Schedule 1 of the federal SARA and is also listed as EndangeredFootnote6 under Ontario's Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA).

The Blue Racer population that occurs in Canada is estimated to constitute less than 1% of the subspecies' global distribution, with an Index of Area of OccupancyFootnote7 (IAO) of 16 km2 (COSEWIC 2012).

3 Recovery feasibility summary

Based on the following four criteria that Environment and Climate Change Canada uses to establish recovery feasibility, there are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of the Blue Racer. In keeping with the precautionary principle, this recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA, as would be done when recovery is determined to be technically and biologically feasible. This recovery strategy addresses the unknowns surrounding the feasibility of recovery.

- 1. Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance.

- Yes. In Canada, a single breeding population of the Blue Racer is present on Pelee Island, Ontario. COSEWIC (2012) estimated the population to be less than 250 adults and possibly declining, although no formal surveys have been undertaken since 2002. However, hatchlings and juveniles have been observed as recently as 2015 (Crowley pers. comm. 2015) indicating that the population has been reproducing. The size of the population makes it vulnerable to extinction from demographic and environmental stochasticity Footnote8, catastrophic events and loss of genetic variability. The Pelee Island population is isolated from other Blue Racer populations and there is currently no effective immigration or emigration of individuals to adjacent mainland populations in the United States. Populations in Michigan, Iowa and Illinois are apparently secure and individuals from these populations would be adapted to local conditions in Ontario, and may provide opportunities for rescue effort Footnote9.

- 2. Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

- Unknown. Within the species' existing range in Canada (i.e., Pelee Island), suitable habitat exists, but is fragmented and may be further degraded by urban and agricultural development activities and increased road traffic (COSEWIC 2012). Availability of hibernation habitat is currently limited, and nesting sites, which are naturally rare, have become more limited on Pelee Island, thus forcing the species to use less optimal sites (Willson and Cunnington 2015). Although little information on population trends is available, informal surveys conducted between 2000 and 2009 indicate that the population may have declined, and suggest that habitat may be degraded (COSEWIC 2012). It may be possible to increase the amount of suitable habitat, and maintain sufficient habitat to support the species in Canada, through active management. The acquisition and active management of land by the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) in 2009 and 2010 on Pelee Island has allowed for some natural habitat regeneration, as well as the establishment of new habitat features. Over time, the quality of these NCC-managed properties should continue to improve. In areas not currently utilized by the species, it is hoped that future emigration into these areas will occur (MacKinnon and Porchuk 2006), and monitoring of the habitats created by NCC for use by Blue Racers should be encouraged.

- 3. The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

- Unknown. Habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation from activities associated with land use changes and increased development and vehicular mortality are the most significant threats to the Blue Racer. Threats to the Blue Racer are not well quantified or monitored on Pelee Island, but future threats could likely be mitigated although there may also be irreversible habitat loss and fragmentation. The development and implementation of Best Management Practices (e.g., maintenance of suitable vegetation types including lawns, construction of artificial hibernacula, creation of nesting and cover habitat) to restore and maintain Blue Racer habitat, and the securement of habitat through conservation easements or land purchases may mitigate the future loss and fragmentation of habitat (Nature Conservancy of Canada 2008; Mifsud 2014). The implementation of education and awareness programs that promote better understanding of species at risk-related legislation such as SARA and the ESA, as well as existing stewardship options for landowners may address the intentional persecution of snakes; while mitigation measures such as the creation of ecopassages and roadside fencing in combination with road signage may help to reduce road mortality. Additionally, Snake Fungal Disease (SFD) has been identified as a potential threat to the Blue Racer in this recovery strategy. It is not known what impact SFD may have on the species within Canada, and methods for controlling SFD have not yet been developed.

- 4. Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe.

- Unknown. The priority for recovery of the Blue Racer is to maintain and, if feasible, increase the current abundance and distribution of the species within its existing range. Addressing threats to the species and its habitat is vital to achieving this objective. The severity of threats, methods to avoid or mitigate threats, and effectiveness of recovery techniques are poorly known at this time. However, it is anticipated that recovery activities such as protecting and connecting habitat through land purchases and conservation easements, managing vegetation succession through prescribed burns, and the creation of hibernation, nesting and shelter habitat will support recovery.

As the Blue Racer is at the northern extent of its North American distribution and has always had a naturally limited distribution in Canada, this species may continue to be vulnerable to human-caused and natural stressors despite efforts to recover the species.

4 Threats

As described in the provincial recovery strategy (Part 2, section 1.6), the loss, degradation and fragmentation of habitat on Pelee Island is both a historic and an ongoing threat to the Blue Racer (COSEWIC 2012); as is the increased traffic associated with new development projects, which increases road-related mortality of snakes. Intentional killing of snakes is not uncommon (Ashley et al. 2007), and there is evidence that Blue Racers have been intentionally killed on Pelee Island.

In addition to those threats identified in Part 2, evidence suggests that Wild Turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo), which were introduced to Pelee Island in 2002, may prey on juvenile Blue Racers (MacKinnon and Porchuk 2006; COSEWIC 2012).

Additionally, another potential threat that may affect the Blue Racer is Snake Fungal Disease (SFD) (Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola) (Sleeman 2013). This is an emerging fungal disease in wild snakes that causes severe skin lesions, leading to widespread morbidity and mortality (Sleeman 2013; Allender et al. 2015). SFD is currently known to affect seven species including the Northern Watersnake, as well as the Eastern Foxsnake (Pantherophis gloydi), Eastern Milksnake (Lampropeltis triangulum), and Massasauga (Sistrurus catenatus) (Sleeman 2013). SFD has been confirmed in Ontario, in an Eastern Foxsnake found in southwestern Ontario in 2015 (Crowley pers. comm. 2015). It has also been confirmed in nine states in the U.S., although it is considered likely to be even more widespread (Sleeman 2013).

The disease spreads directly through contact with infected snakes and indirectly via environmental exposure (i.e., contact with contaminated soil) (Sleeman 2013; Allender et al. 2015). In 2009, a Northern Watersnake with a fungal skin infection consistent with SFD was collected from an island in western Lake Erie, Ohio (Sleeman 2013). While the population-level effects of SFD remain unclear, it appears to spread easily and is often fatal, and there is concern it could have negative impacts on small snake populations of conservation concern (Sleeman 2013; Allender et al. 2015). For example, SFD is thought to have contributed to a 50% decline in a small Timber Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) population in New Hampshire in 2006 to 2007 (Clark et al. 2011). Climate change has the potential to further increase the risk of SFD to snake populations, as warming temperatures may lead to increased infection rates in hibernating snakes (Allender et al. 2015). Due to the small population and isolated range of the Blue Racer, both globally and in Canada, SFD may threaten population viability if it becomes established in the population.

5 Population and distribution objectives

The provincial Recovery Strategy for the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) in Ontario recommends the following recovery goal:

- The recovery goal for the Blue Racer in Ontario is to (1) maintain, or if necessary increase population abundance to ensure long-term population persistence; (2) increase habitat quantity, quality and connectivity on Pelee Island; and (3) continue to assess the feasibility of repatriating the species to portions of its former range on the southern Ontario mainland.

Under SARA, a population and distribution objective for the species must be established. Consistent with the goal recommended in the Government of Ontario's Recovery Strategy, Environment and Climate Change Canada's population and distribution objective for the Blue Racer is to:

- Maintain and, if biologically and technically feasible, increase the species' current abundance and distribution in Canada.

Pelee Island is considered to contain a single population of less than 250 individuals (COSEWIC 2012). The best available estimates of population size are from mark-recapture data available for the years 1993-1995 and 2000-2002, estimating 307 adults (95% confidence intervalFootnote10 = 129-659) and 140.7 adults (95% confidence interval = 59.0-284.7), respectively (Willson and Cunnington 2015). Though differences in sampling design and study area between the two time periods preclude direct comparison of the estimates, informal surveys provide reasonable certainty that the number of adult snakes on Pelee Island has declined, and it is likely that their numbers remain below 250 (COSEWIC 2012). There remain two locations on Pelee Island where suitable habitat is known to still exist, but the presence of Blue Racer is yet to be confirmed, as the species has not been observed in over a decade despite repeated survey efforts. It is not known whether the current number of Blue Racers in the Ontario population will be sufficient to ensure long-term population persistence. Until further information is available on minimum viable population size, the priority for recovery of the Blue Racer is to maintain and, if feasible, increase the abundance and distribution of the species within its existing range in Canada.

Blue Racers have been restricted in Canada to Pelee Island for almost 30 years, and it is highly unlikely Blue Racers could naturally recolonize their historical range on the Ontario mainland without the intentional release of individuals from Pelee Island or the United States. Therefore, efforts to investigate the feasibility of repatriating the species to portions of its former range are important to the species survival in Canada and to increasing the species' distribution. Thus far, many repatriation efforts for snakes have been unsuccessful (Dodd and Seigel 1991; Fischer and Lindemayer 2000); though several studies suggest that the success of repatriation efforts is enhanced when the probable causes of decline or extirpation are understood or removed (Burke 1991; Reinert 1991; Fischer and Lindemayer 2000). Given the reasons for Blue Racer decline on the mainland are not fully understood, the focus of this recovery strategy is to increase suitable habitat and improve habitat connectivity on Pelee Island in order to maintain, and if feasible increase, the abundance and distribution of the existing population of the Blue Racer. However, while not part of the current federal objective, in adopting the Recovery Strategy for the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) in Ontario (Part 2), Environment and Climate Change Canada supports continuing to assess the feasibility of repatriating the species to portions of its former range on the southern Ontario mainland. New information on the feasibility of repatriation will be evaluated as it becomes available.

Maintaining the existing population of the Blue Racer on Pelee Island will require controlling and mitigating threats to this species, especially those related to a loss of suitable habitat. Increasing suitable habitat and promoting connectivity between important habitats is essential to maintaining a viable Blue Racer population on Pelee Island. Provided other threats to Blue Racer individuals (e.g., housing and agricultural land development, road mortality, intentional persecution) are managed and mitigated, viable populations would be expected to persist over long time frames where sufficient suitable habitat exists, and the natural expansion of the existing population to different areas of Pelee Island may be encouraged through maintaining currently unoccupied adjacent suitable habitat.

6 Broad strategies and general approaches to meet objectives

Environment and Climate Change Canada is adopting the approaches identified in section 2.3 of the Recovery Strategy for the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) in Ontario (Part 2) as the broad strategies and general approaches to meet the population and distribution objective; with the exception of Approaches 2.1 and 5.1. These two approaches have been modified, for the purposes of this recovery strategy, to read as follows:

2.1 Support the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry's efforts to develop a habitat regulation and/or habitat description for Blue Racer under Ontario's Endangered Species Act, 2007.

5.1 Support any potential efforts of the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry to determine feasibility of repatriation.

Environment and Climate Change Canada is also adding the following approach to respond to the emerging threat of SFD:

4.6 Investigate the threat of SFD to Blue Racer within Canada, including presence of the disease within the Canadian population; possible vectors of the disease; methods of disease control.

7 Critical habitat

7.1 Identification of the species' critical habitat

Section 41 (1) (c) of SARA requires that recovery strategies include an identification of the species' critical habitat, to the extent possible, as well as examples of activities that are likely to result in its destruction. Under SARA, critical habitat is "the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species and that is identified as the species' critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in an action plan for the species".

Identification of critical habitat is not a component of provincial recovery strategies under the Province of Ontario's ESA. Under the ESA, when a species becomes listed as endangered or threatened on the Species at Risk in Ontario List, it automatically receives general habitat protection. The Blue Racer currently receives general habitat protection under the ESA; however, a description of the general habitat has not yet been developed. In some cases, a habitat regulation may be developed that replaces the general habitat protection. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protectedFootnote11 as the habitat of the species by the Province of Ontario. A habitat regulation has not been developed for Blue Racer under the ESA; however, the provincial recovery strategy (Part 2) contains a recommendation on the area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation. This federal recovery strategy identifies critical habitat for the Blue Racer in Canada to the extent possible, based on this recommendation and on the best available information as of June 2015. Additional critical habitat may be added in the future if new information supports the inclusion of areas beyond those currently identified.

The identification of critical habitat for Blue Racer is based on two criteria: habitat occupancy and habitat suitability.

7.1.1 Habitat occupancy

The habitat occupancy criterion refers to areas of suitable habitat (defined in Section 7.1.2) where there is a reasonable degree of certainty of current use by the species.

Habitat is considered occupied when:

- At least one Blue Racer individual has been observed in any single year since 1990.

In Ontario, the remaining population of Blue Racers includes only a small number of individuals (COSEWIC 2012). The species is not well surveyed across its range, therefore a single observation may be indicative of a local population or important habitat features. This is appropriate for the Blue Racer which has a small geographic range and is facing considerable threats.

The twenty-five year timeframe (1990-2015) for the habitat occupancy criterion is reasonable due to the cryptic nature of the species and the limited number of systematic surveys. Most available records are from mark-recapture and radio telemetryFootnote12 surveys conducted between 1993 and 1995 by Porchuk (1996), and provide some of the best information on known locations of nesting and hibernacula features. The Blue Racer exhibits fidelity to nesting and hibernacula features and these features are limited on Pelee Island (Willson and Cunnington 2015). In addition, application of a twenty-five year timeframe allows for the inclusion of two locations where habitat appears to be suitable, but for which the Blue Racer has not been observed for over a decade despite repeated survey efforts. Future survey efforts should confirm the status of the species and habitat use at these two locations.

Habitat occupancy is based on documented nesting or hibernacula locations, survey and telemetry data, and incidental observations of the Blue Racer (live or dead) in locations where key suitable habitat biophysical attributes defined below in Section 7.1.2 are present nearby. These observational data must have a spatial precision of <1km or provide enough detail to be associated with a specific suitable habitat feature(s) to be considered adequate to identify critical habitat.

7.1.2 Habitat suitability

Habitat suitability refers to areas possessing a specific set of biophysical attributes that support individuals of the species to carry out essential life cycle activities (e.g., hibernation, mating, nesting, foraging, shelter) as well as their movements. Although there are no absolute barriers to movement on Pelee Island, it is important that all required habitat areas are linked or in reasonable proximity to one another so that snakes can move between them with ease. Suitable habitat for the Blue Racer can therefore be described as a mosaic of dry, open to semi-open habitat, in which specific biophysical attributes can be associated with essential life cycle activities. Within the area of suitable habitat, the biophysical attributes required by the Blue Racer will vary over space and time with the dynamic nature of ecosystems. In addition, particular biophysical attributes will be of greater importance to snakes at different points in time (e.g., during different life processes, seasons or at various times of the year).

The biophysical attributes of critical habitat are detailed in Table 1.

| Life stage and/or need | Biophysical attributes | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| All life processes (Hibernation, Nesting, Shelter, Thermoregulation, Foraging, Mating, Movement) |

|

|

| Shelter |

|

|

| Nesting |

|

|

| Hibernation |

|

|

| Movement |

|

|

a The definition of edge habitat corresponds with the definition used in the habitat analyses of Porchuk (1996). Edge habitat is defined as occurring within five metres of the interface between the two adjoining communities (e.g., forest-field). For example, where a forest transitions to an open habitat, the edge community would extend five metres into the forest and five metres into the open habitat.

b Non-naturally occurring features are human-constructed or maintained structures with a primary purpose other than providing habitat for wildlife.

c Although use has been exhibited, non-naturally occurring nesting habitat such as sheet metal and wooden boards have not been included as biophysical attributes because the majority of eggs laid under these objects do not hatch due to extreme temperature and moisture fluctuations (Porchuk 1996; Porchuk 1998).

d The definition of edge habitat corresponds with the definition used in the habitat analyses of Porchuk (1996). Edge habitat is defined as occurring within five metres of the interface between the two adjoining communities (e.g., forest-field). For example, where a forest transitions to an open habitat, the edge community would extend five metres into the forest and five metres into the open habitat.

e A type of habitat that allows for the passage of animals.

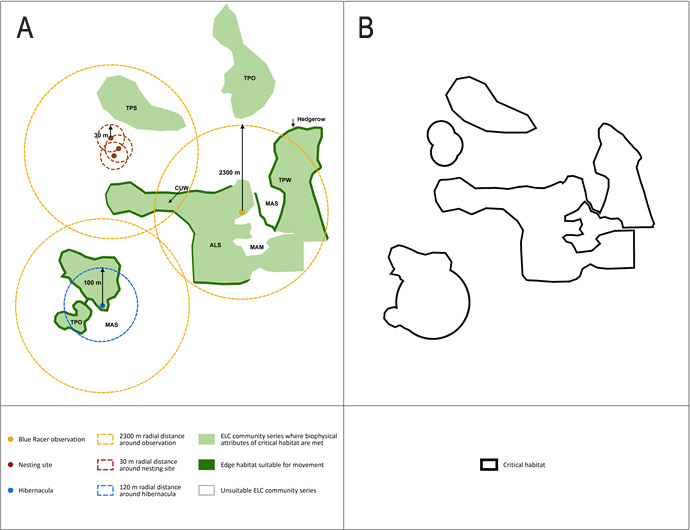

Given that there is no available information on the amount of habitat that is required for the Blue Racer to complete its life cycle activities within a home range, a precautionary approach is used to identify an extent of suitable habitat for the Blue Racer. This description of suitable habitat reflects the fact that certain biophysical attributes do not need to be immediately adjacent to each other, as long as they remain connected so that the individuals can easily move between them to meet all their biological needs and respond to or avoid disturbances as required. The distances determining the extent of suitable habitat are specific to the Blue Racer and based on the species' biological and behavioural requirements (see Part 2, section 1.4).

Suitable habitat for the Blue Racer is described as:

- The extent of the biophysical attributes that are located within a radial distance of 2,300 m from a known record of Blue Racer.

This criterion will capture the vast majority of potential hibernation and nesting habitats, which are important considering few precise locations are known. In addition, where they are known, hibernacula and nest sites are also identified separately because of their close relationship with survival and recruitment of individuals. Hibernacula and nest site availability and selection are known factors limiting the Blue Racer and are likely to be especially important for population persistence given the rarity of these habitats, and the fidelity to and communal use of these sites (which may indicate a low availability of optimal sites). Therefore, suitable habitat for the Blue Racer also includes:

- The area within a 120 m radial distance from the entrance and/or exit of a naturally-occurring Blue Racer hibernacula feature (single site or complex); and

- The area within a 30 m radial distance from a known naturally-occurring nest record of the Blue Racer.

Suitable habitat for the Blue Racer can be described using the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) framework for Ontario (from Lee et al. 1998)Footnote13, which provides a standardized approach to the interpretation and delineation of dynamic ecosystem boundaries. The ELC approach classifies habitats not only by vegetation community but also considers hydrologyFootnote14 and topographyFootnote15, and as such encompasses the biophysical attributes of the habitat for Blue Racer. In addition, ELC terminology and methods are familiar to many land managers and conservation practitioners who have adopted this tool as the standard approach for habitat classification in Ontario, and has been used specifically on Pelee Island.

The biophysical attributes of Blue Racer suitable habitat are typically found in the following ELC Community Series designations: Open Alvar (ALO); Shrub Alvar (ALS); Treed Alvar (ALT); Open Tallgrass Prairie (TPO); Tallgrass Savanna (TPS); Tallgrass Woodland (TPW); Cultural Meadow (CUM); Cultural Thicket (CUT); Cultural Savanna (CUS); and Cultural Woodland (CUW). Due to their rarity, confirmed hibernacula and nesting will also be identified as critical habitat wherever they are located (they do not need to occur in ELC polygons of suitable habitat).

Movement habitat is also not described using the ELC framework. Instead movement refers to any contiguousFootnote16 edge habitat that connects adjacent suitable ELC habitat patches for hibernation, mating, nesting, shelter, and foraging, as well as known hibernacula and nesting sites. The search for these suitable habitat patches constitutes the majority of movements for snakes. Blue Racers on Pelee Island move substantial distances over the active season (Porchuk 1996). The distance used to set the suitable habitat boundary (i.e., 2,300 m radial distance from an observation) is the area that will capture over 90% of an individual's range, based on a data analysis of the Blue Racer's radio-tracked movements from known hibernacula on Pelee Island (Porchuk 1996; Willson and Porchuk unpub. data from Willson and Cunnington 2015). Connectivity between habitats that remain occupied and available to the Blue Racer is important as much of the habitat for the species has already been lost or fragmented within the landscape. Hedgerows, riparian vegetation strips adjacent to canals and roadways, shorelines, and forest connect many of the habitat patches, and Blue Racers readily use the edges of these habitat types for movement in addition to the edges of the ecological community series described above (Willson 2002; Porchuk 1996; Brooks and Porchuk 1997).

Many of the cracks and fissures visible on the surface through which Blue Racers gain access to underground cavities or caverns for hibernation, are connected underground and Blue Racers can move several metres horizontally through them (Porchuk 1996). Hibernation complexes up to 120 m in diameter have been documented in the limestone plain regions of Pelee Island (Porchuk and Willson unpub.data from Willson and Cunnington 2015), and including the area within 120 m of the entrance and/or exit of a hibernacula feature ensures that most of the complex will be protected.

The area within a 30 m radial distance around a nesting observation is important to maintain the microclimatic conditions (e.g., thermal, vegetative and light features) and serves as a staging area. Non-naturally occurring nesting habitat such as sheet metal and wooden boards have not been included as suitable nesting habitat because the majority of eggs laid under these objects do not hatch due to extreme temperature and moisture fluctuations (Porchuk 1996; Porchuk 1998).

Shelter habitat used by Blue Racers is typically composed of living or dead vegetation on the ground or in trees, large flat rocks, and piles or accumulations of rock and soil. However, the Blue Racer may also use non-naturally occurring features such as discarded sheet metal and car parts for shelter. Since Blue Racers exhibit fidelity to shelter habitat, these features are important components of the species' habitat. Where feasible, the non-naturally occurring features should be left in place to provide areas for cover, protection from predators, and thermoregulation when they occur in or immediately adjacent to critical habitat.

Active agricultural fields in row crops or in crop rotation, including vineyards, do not possess the biophysical attributes required by Blue Racer and are not identified as critical habitat (including hibernacula) as they are poor quality habitats offering limited cover and use of these habitats can result in increased rates of mortality, and may become ecological trapsFootnote17. In addition, roads pose a high mortality threat to Blue Racers, and while they may be crossed during the active season or during movement to and from hibernacula or nesting sites (Porchuk 1996; Brooks and Porchuk 1997; MacKinnon and Porchuk 2006), they do not provide habitat for the species and as such are not identified as critical habitat.

7.1.3 Application of the Blue Racer critical habitat criteria

Critical habitat for the Blue Racer is identified as the extent of suitable habitat (section 7.1.2), where the habitat occupancy criterion is met (section 7.1.1). At occupied locations, critical habitat is defined as the ensemble of suitable habitat located within 2,300 m of a Blue Racer record (see Figure 1). Critical habitat will also include hibernacula and nesting features wherever they occur along with surrounding habitat within 120 m and 30 m of the feature, respectively. Application of the critical habitat criteria to the best available data identified critical habitat for the known extant population of the Blue Racer in Canada (Pelee Island), totaling up to 526 haFootnote18. As more information becomes available, additional critical habitat may be added or may be further refined.

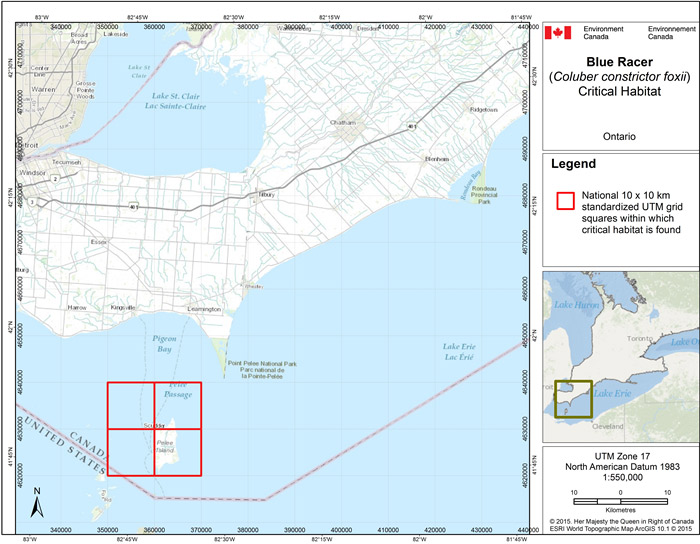

Due to the sensitivities of the species (i.e., to persecution), critical habitat for the Blue Racer is presented using 10 x 10 km Standardized Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) grid squares (Figure 2, See also Table 2). The UTM grid squares presented in Figure 2 are part of a standardized grid system that indicates the general geographic areas containing critical habitat, which can be used for land use planning and/or environmental assessment purposes. In addition to providing these benefits, the 10 x 10 km Standardized UTM grid respects provincial data-sharing agreements in Ontario. Critical habitat within each grid square occurs where the description of habitat occupancy (section 7.1.1) and habitat suitability (section 7.1.2) are met. More detailed information on critical habitat to support protection of the species and its habitat may be requested on a need-to-know basis by contacting Environment and Climate Change Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service at ec.planificationduretablissement-recoveryplanning.ec@canada.ca.

Long description for Figure 1

This schematic illustrates the procedure for defining critical habitat using Blue Racer observations, nesting sites and hibernacula. Further details are given in surrounding paragraphs.

Long description for Figure 2

Figure 2 shows the four grid squares which contain critical habitat for the species. These four grid squares cover Pelee Island.

| Population | 10 x 10 km Standardized UTM grid square IDf | Province/territory | UTM grid square coordinatesg Easting |

UTM grid square coordinatesg Northing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelee Island | 17TLG63 | Ontario | 360000 | 4630000 |

| Pelee Island | 17TLG53 | Ontario | 350000 | 4630000 |

| Pelee Island | 17TLG62 | Ontario | 360000 | 4620000 |

| Pelee Island | 17TLG52 | Ontario | 350000 | 4620000 |

Total = 4 grid squares

f Based on the standard UTM Military Grid Reference System, where the first 2 digits and letter represent the UTM Zone, the following 2 letters indicate the 100 x 100 km Standardized UTM grid, followed by 2 digits to represent the 10 x 10 km Standardized UTM grid containing all or a portion of the critical habitat unit. This unique alphanumeric code is based on the methodology produced from the Breeding Bird Atlases of Canada (See Bird Studies Canada for more information on breeding bird atlases). To protect species sensitivities, UTM Standardized grid squares at the intersection of UTM zones are merged with their adjacent grid squares to ensure a 10 x 10 km grid square minimum.

g The listed coordinates are a cartographic representation of where critical habitat can be found, presented as the southwest corner of the 10 x 10 km Standardized UTM grid square that is the critical habitat unit. The coordinates are provided as a general location only.

7.2 Activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat

Understanding what constitutes destruction of critical habitat is necessary for the protection and management of critical habitat. Destruction is determined on a case by case basis. Destruction would result if part of the critical habitat was degraded, either permanently or temporarily, such that it would not serve its function when needed by the species. Destruction may result from a single activity or multiple activities at one point in time or from the cumulative effects of one or more activities over time. Activities described in Table 3 include those likely to cause destruction of critical habitat for the species; however, destructive activities are not limited to those listed.

Blue Racer habitat requires management to remain suitable, thus some of the activities necessary to maintain habitat may result in the temporary removal of critical habitat (e.g., mowing and/or burning of shrubs and other successional vegetation). However, these activities have the potential to contribute to the future availability of critical habitat (e.g., burning vegetation at locations can create/maintain more open areas needed by Blue Racers during certain life processes). Timing of such activities is important to ensure that critical habitat is not permanently damaged or destroyed, and is described below in Table 3. Timing restrictions will need to be discussed with the appropriate agencies (generally, the province of Ontario (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry) on non-federal lands, and Environment and Climate Change Canada on federal lands), on a case-by-case basis.

| Description of activity | Description of effect (biophysical attribute or other) | Location of the activity likely to destroy critical habitat Within critical habitat Foraging, nesting, and shelter habitat |

Location of the activity likely to destroy critical habitat Within critical habitat Movement habitat |

Location of the activity likely to destroy critical habitat Within critical habitat Hibernacula |

Outside critical habitat |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Development and conversion of suitable habitat to land uses that do not provide suitable habitat for this species (e.g., residential or commercial development, road building) | Site clearing, blasting and grading that alter cover result in the direct loss of suitable habitat characteristics (e.g., piles or accumulations of rock and soil, living or dead vegetation) which the species relies on for foraging, for nesting, for shelter and for overwintering. Blasting may also damage overwintering habitat outside the active quarry area by destroying or preventing access to underground hibernacula. |

X | X | X | X |

| Destruction or alteration of natural structures providing nesting sites and/or hibernacula (e.g., use of off-road vehicles, farm machinery or lawn mowers) | The use of off-road vehicles, farm machinery or lawn mowers in critical nesting and/or hibernacula habitat may damage or destroy preferred nesting features and substrates (e.g., decayed downed woody debris); and/or may permanently damage or destroy, or may prevent access to, important hibernation sites. | X | blank | X | blank |

| Activities that result in the net removal, disturbance or destruction of natural and non-naturally occurring cover habitat | Blue Racers may use natural and/or non-naturally occurring cover habitat for predator protection and shelter during various life stages (e.g., shedding and gestation). The removal, disturbance or destruction of such cover habitat may increase the snakes' susceptibility to predation and exposure and interfere with digestion, gestation and/or the recovery from an injury. Naturally occurring cover habitat should not be removed at any time of the year to ensure the availability of cover habitat within and outside of the active season, and during subsequent active seasons. If the removal of non-natural cover habitat were to occur during the active season (April to approx. November) within the bounds of critical habitat, it is likely that snakes would be disturbed and critical cover habitat lost. Blue Racers show high site fidelity to cover objects within an active season and so its removal when in use may be detrimental. However, if the removal of non-natural cover habitat occurs outside the active season (approx. December to March), snakes may use alternate cover habitat (e.g., naturally occurring cover) in subsequent active seasons. It may be possible to replace the function served by human-influenced structures or features should they need to be removed or disturbed. This determination will need to be done on a case-by-case basis taking into consideration a number of factors including the species' biology, potential risk to the species, the availability of natural and anthropogenic habitat features in the surrounding area, and options for mitigation or replacement. Note: Removal of human refuse used as nesting habitat would not destroy critical habitat, because non-naturally-occurring objects do not provide an appropriate microclimate for successful egg development (e.g., low hatch rates). However, it must be ascertained that the object does not also provide cover habitat. |

X | X | X | blank |

| Activities that result in significant reduction or clearing of natural and semi-natural features, including the removal of hedgerows, and/or living or dead ground vegetation | Removing hedgerows, and/or living or dead ground vegetation at any time of the year would result in the direct loss of habitat that the species relies on for foraging, mating, movement, nesting, and cover habitat. Removal of linear habitats provided by hedgerows would remove connectivity between larger habitat patches used by the species. | X | X | blank | blank |

| Prescribed fire | Prescribed burns to control succession create habitat for the Blue Racer, but may also be harmful depending on timing. At the wrong time, prescribed burns may remove cover and prey species leaving snakes vulnerable to predation and without adequate energy reserves prior to and following hibernation. If this activity were to occur in September or October, within the bounds of critical habitat, it is likely that the effects on critical habitat would be direct. |

X | X | blank | blank |

8 Measuring progress

The performance indicators presented below provide a way to define and measure progress toward achieving the population and distribution objective. Every five years, success of recovery strategy implementation will be measured against the following performance indicators:

- The abundance and distribution of the Blue Racer in Canada has been maintained, and if biologically and technically feasible, increased.

9 Statement on action plans

One or more action plans will be completed for Blue Racer by December 31, 2023.

10 Effects on the environment and other species

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is conducted on all SARA recovery planning documents, in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals. The purpose of a SEA is to incorporate environmental considerations into the development of public policies, plans, and program proposals to support environmentally sound decision-making and to evaluate whether the outcomes of a recovery planning document could affect any component of the environment or any of the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy's (FSDS) goals and targets.

Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that strategies may also inadvertently lead to environmental effects beyond the intended benefits. The planning process based on national guidelines directly incorporates consideration of all environmental effects, with a particular focus on possible impacts upon non-target species or habitats. The results of the SEA are incorporated directly into the strategy itself, but are also summarized below in this statement.

This recovery strategy will clearly benefit the environment by promoting the recovery of the Blue Racer and by protecting and enhancing habitat for two other co-occurring Threatened snake species, the Eastern Fox Snake (Elaphe gloydi) and the Lake Erie Water Snake (Nerodia sipedon insularum).

The potential for the strategy to inadvertently lead to adverse effects on other species was considered. Other species at risk on Pelee Island include the Prothonotary Warbler (Protonaria citrea), Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis), Blanchard's Cricket Frog (Acris blanchardi), Small-mouthed Salamander (Ambystoma texanum), Wild Hyacinth (Camassia scilloides), Chimney Swift (Chaetura pelagica), Eastern Prickly Pear (Opuntia humifusa), Grey Fox (Urocyon cineroargenteus), Kentucky Coffee-tree (Gymnocladus dioicus), Red Mulberry (Morus rubra), Acadian Flycatcher (Empidonax virescens), and the Eastern Spiny Softshell Turtle (Apalone spinifera spinifera). Recovery approaches for the Blue Racer are not anticipated to have adverse effects on these species that are predominantly associated with habitats not preferred by the Blue Racer. Actions to maintain open habitats for the Blue Racer may have an adverse effect on the Endangered Yellow-breasted Chat (Icteria virens virens) that is dependent on early successional habitat. To mitigate adverse effects on the Yellow-breasted Chat, the ecological risk of each activity must be individually assessed before undertaking them. For example, the location of prescribed burns can be controlled so that they do not eliminate active Yellow-breasted Chat habitat while creating future habitat for the species. Following this approach, mitigation strategies are available to meet the needs of both species at risk on Pelee Island.

The SEA concluded that this strategy will clearly benefit the environment and will not entail any significant adverse effects that cannot be avoided or mitigated. The reader should refer to the following sections of the document, in particular: habitat needs (Part 2, section 1.4), knowledge gaps (Part 2, section 1.7).

References

Allender, M.C., D.B. Raudabaugh, R.H. Gleason and A.N. Miller. 2015. The natural history, ecology, and epidemiology of Ophidiomyces ophiodiicola and its potential impact on free-ranging snake populations. Fungal Ecology 17: 187-196.

Brooks, R. J. and B. D. Porchuk. 1997. Conservation of the endangered blue racer snake (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island, Canada. Report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 26 pp.

Burke, R. L. 1991. Relocations, repatriations, and translocations of amphibians and reptiles: taking a broader view. Herpetologica 47:350-357.

Carfagno, G. L. F. and P. J. Weatherhead. 2006. Intraspecific and interspecific variation in use of forest-edge habitat by snakes. Canadian Journal of Zoology 84:1440-1452.

Clark, R.W., M.N. Marchand, B.J. Clifford, R. Stechert, S. Stephens. 2011. Decline of an isolated timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) population: interactions between climate change, disease, and loss of genetic diversity. Biological Conservation 144, 886-891.

Conant, R. and J. T. Collins. 1998. A field guide to reptiles and amphibians of eastern and central North America. 3rd, expanded edition. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, Massachusetts.

COSEWIC. 2012. COSEWIC status appraisal summary on the Blue Racer Coluber constrictor foxii in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. xvii pp. (Species at Risk Public Registry)

COSEWIC. 2008. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the Eastern Foxsnake, Elaphe gloydi, Carolinian Population and Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Population, in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. Vii + 45 pp.

Crother, B.I., J. Boundy, J.A. Campbell, K. de Quiroz, D.R. Frost, R. Highton, J.B. Iverson, P.A. Meylan, T.W. Reeder, M.E. Seidel, J.W. Site Jr, T.W. Taggart, S.G. Tilley, and D.B. Wake. 2001. Scientific and standard English names of amphibians and reptiles of North America north of Mexico, with comments regarding confidence in our understanding. Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles, American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists, and the Herpetologists' League. Available at: http://www.ssarherps.org/pdf/Crother.pdf. (Accessed 15 March 2014).

Crowley, J. pers. comm. 2015. Information received by CWS-ON through technical review. Species at Risk Herpetology Specialist. Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. October 20, 2015.

Dodd, C. K. J. and R. A. Seigel. 1991. Relocation, repatriation, and translocation of amphibians and reptiles: are they conservation strategies that work? Herpetologica 47:336-350.

Fischer, J. and D. B. Lindenmayer. 2000. An assessment of the published results of animal relocations. Biological Conservation 96:1-11.

Langwig, K. E., J. Voyles, M. Q. Wilber, W. F. Frick1, K. A. Murray, B. M. Bolker, J. P. Collins, T. L. Cheng, M. C. Fisher, J. R. Hoyt, D. L. Lindner, H. I. McCallum, R. Puschendorf, E. B. Rosenblum, M. Toothman, C. K. R. Willis, C. J. Briggs and A. M. Kilpatrick. 2015. Context-dependent conservation responses to emerging wildlife diseases. Front. Ecol. Environ. 13(4): 195–202, doi:10.1890/140241

Lee, H. T., W. D. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig, and S. McMurray. 1998. Ecological land classification for Southern Ontario: first approximation and its application. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southcentral Science Section, Science Development and Transfer Branch.

MacKinnon, C.A., and B.D. Porchuk. 2006. Recovery Strategy for the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) in Canada (Draft). Blue Racer Recovery Team.

Mifsud, D. 2014. Michigan Amphibian and Reptile Best Management Practices (PDF; 8.7 Mb). Herpetological Resource and Management Technical Publication 2014.

NatureServe. 2014. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. . (Accessed: January 17, 2014 ).

Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC). 2008. Management Guidelines: Pelee Island Alvars. NCC – Southwestern Ontario Region, London, Ontario. 43 pp.

Porchuk, B. and P. Prevett. 1999. Canadian Blue Racer Snake Recovery Plan. Draft report. Ottawa: Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife Committee.

Porchuk, B.D. 1998. Canadian Blue Racer snake recovery plan. Report prepared for the Recovery of Nationally Endangered Wildlife (RENEW) committee. 55 pp.

Porchuk, B. D. 1996. Ecology and conservation of the endangered blue racer snake (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island, Canada. M.Sc. Thesis. University of Guelph, Guelph, Ontario.

Porchuk, B. D. and R. J. Brooks. 1995. Natural history: Coluber constrictor, Elaphe vulpina and Chelydra serpentina. Reproduction. Herpetological Review 26:148.

Reinert, H. K. 1991. Translocation as a conservation strategy for amphibians and reptiles: some comments, concerns, and observations. Herpetologica 47:357-363.

Willson, R. J. 2002. A systematic search for the blue racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) on Pelee Island (2000–2002). Final report prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. 38 pp. + digital appendices.

Willson, R.J. and G.M. Cunnington. 2015. Recovery Strategy for the Blue Racer (Coluber constrictor foxii) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 35 pp.