Recovery Strategy for the Eastern Sand Darter (Ammocrypta pellucida) in Canada: Ontario Populations [Proposed]: Background

Scientific name: Ammocrypta pellucida (Girard 1856)

Common name: Eastern Sand Darter, dard de sable

Current COSEWIC status & year of designation: Threatened 2009

Canadian occurrence: Ontario, Quebec

Reason for designation: This species prefers sand bottom areas of lakes and streams in which it burrows. There is continuing decline in the already small and fragmented populations; four (of 11) have probably been extirpated. The extent of occurrence of this species in Ontario is approximately half of what it was in the 1970s as a result of habitat loss and degradation from increasing urban and agricultural development, stream channelization and competition with invasive alien species.

Status history: The species was considered a single unit and designated Threatened in April 1994 and November 2000. When the species was split into separate units in November 2009, the "Ontario populations" unit was designated Threatened.

Classification: The current classification of the Eastern Sand Darter is from the Integrated Taxonomic Information System on-line database (accessed March 07, 2005):

Phylum: Chordata

Subphylum: Vertebrata

Superclass: Osteichthyes

Class: Actinopterygii

Subclass: Neopterygii

Infraclass: Teleostei

Superorder: Acanthopterygii

Order: Perciformes

Suborder: Percoidei

Family: Percidae

Species: Ammocrypta pellucida

Recent molecular analyses support a monophyletic genus Ammocrypta (Song et al. 1998, Near et al. 2000, Sloss et al. 2004). Ammocrypta clara (Western Sand Darter) and A. vivax (Scaly Sand Darter) have previously been considered subspecies and/or synonyms of A. pellucida (Grandmaison et al. 2004); both are now considered valid species. Records of A. pellucida in the Mississippi River drainage north of the Ohio River confluence represent A. clara while records from the southern reaches represent A. clara or A. vivax (Williams 1975). A. pellucida and A. clara have overlapping distributions in Indiana and Illinois within the Wabash River drainage, and in Kentucky within the Cumberland and Green river drainages.

The Eastern Sand Darter is a small fish with translucent flesh and an elongate body, almost round in cross-section (Scott 1955) (Figure 1). Adults range in total length (TL) from 46-71mm (Trautman 1981), averaging 68mm TL (Scott and Crossman 1973). In Ontario, the maximum TL is 84mm, caught in the Grand River in 1987 (Holm et al. 2010). Adults exhibit a faint yellowish or greenish colouration on the dorsal surface of the head and body, a narrow metallic gold to olive-gold band passing subcutaneously along a line of lateral green rounded blotches, and a white or silvery hue on the ventral surface (Trautman 1981). Young fish are more silvery with little or no yellow (Scott and Crossman 1973, Trautman 1981). Males in breeding condition are flushed with a yellowish colouration and develop tubercles on their pelvic fins. A row of 12 -16 dark greenish blotches are located along the dorsum, which differentiate into rows of paired spots along the base of the dorsal fins, one spot on either side of the fin (Trautman 1981). Nine to 14 (10-14 Scott and Crossman 1973; 10-14 Holm and Mandrak 1996) spots also occur along the lateral line (Trautman 1981). Webbing of fins is transparent; although some individuals sport a yellowish tinge (Trautman 1981). Dorsal fins are separate; the first dorsal fin is spiny (8-11 weak spines), and the second dorsal has soft rays (9-12 rays) (Scott and Crossman 1973). Males have black pigment on the pelvic fin (Page and Burr 1991). Scales are absent from its ventral side with 1-3 scale rows immediately beneath the lateral line (Trautman 1981).

Figure 1. The Eastern Sand Darter (Ammocrypta pellucida). (Drawing by E. Edmonson & H. Crisp (NYSDC))

Description of Figure 1

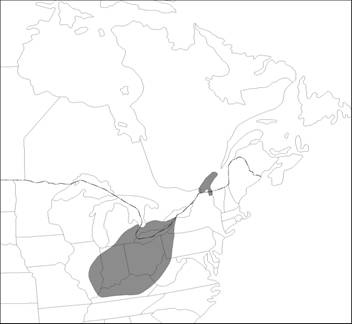

Global range (Figure 2): The Eastern Sand Darter inhabits the Ohio River and Great Lakes drainage and is also found in the Lake Champlain and St. Lawrence River drainages (Figure 2) (Scott and Crossman 1973), which forms part of a disjunct element of the distribution. It occurs in the Canadian provinces of Ontario and Quebec and nine American states: Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, Michigan, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Vermont and West Virginia.

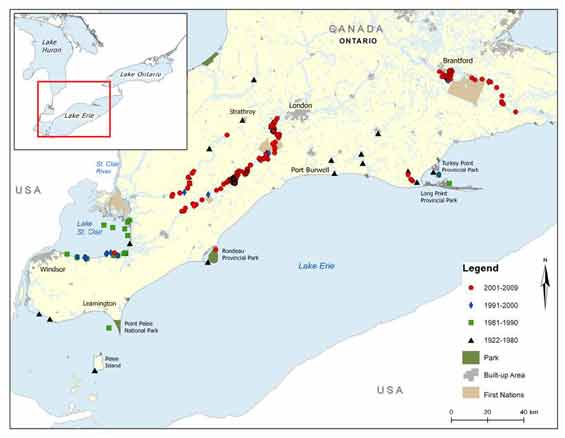

Ontario range (Figure 3): Eastern Sand Darter has been recently collected in lakes Erie and St. Clair, and from the Sydenham, Grand and Thames rivers as well as Big Creek (Norfolk County) (Holm and Mandrak 1996, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) unpublished data, A. Dextrase, unpublished data). Populations are presumed to be extirpated from Big Otter Creek, Catfish Creek and the Ausable River (ARRT 2005).

Lake Erie: Pelee Island (last collected in 1953), north shore of Lake Erie (Colchester Beach and Holiday Beach Provincial Park; last collected 1975), Rondeau Bay, and Inner Long Point Bay.

Lake St. Clair: Eastern Sand Darter has been collected from several areas of Lake St. Clair over the past 25 years - the south shore between the outlet of Pike Creek and the Thames River, and Mitchell's Bay.

Figure 2. Global Eastern Sand Darter distribution in North America.

Description of Figure 2

Sydenham River: Along the East Branch between the Shetland Conservation Area and Dawn Mills, with a disjunct population further upstream between Strathroy and Alvinston (Dextrase et al. 2003).

Thames River: This species has been found in the lower Thames River watershed, between Komoka and Kent Bridge.

Grand River: All sandy areas in the lower main stem from Brantford to just downstream of Cayuga.

Big Creek, Norfolk County: The Eastern Sand Darter was collected from Big Creek in 1923 and 1955. It had not been collected in more recent surveys until three adult Eastern Sand Darter were captured from three different sites in 2008, confirming the continued presence of the species in the watershed.

Big Otter Creek: The Eastern Sand Darter was collected from Big Otter Creek in 1923 and 1955. It has not been collected in more recent surveys.

Catfish Creek: The Eastern Sand Darter was collected from Catfish Creek in 1922 and 1941. It has not been collected in more recent surveys.

Ausable River: There is a single record of Eastern Sand Darter occurring in the river near Ailsa Craig from a 1928 survey. Subsequent searches at this site, and elsewhere in the watershed in potentially suitable habitat, failed to recapture the species.

Percent of global range in Canada: NatureServe (2009) estimates just over 100 extant occurrences of Eastern Sand Darter in North America. Grandmaison et al. (2004) identified approximately 75 streams where Eastern Sand Darter is extant. As there are approximately 16 extant occurrences in Canada, around 10 to 20% of the Eastern Sand Darter's global range is found in Canada, and approximately 50% of this is in Ontario.

Distribution trend: Habitat loss and poor water quality have resulted in a reduced distribution. In Canada, Eastern Sand Darter has declined or become extirpated from 11 of 21 locations. Over the past 50 years, 45% of population occurrences in Ontario have been lost (COSEWIC 2010). Several new sites have been found since the 1970s; however, the net result is a reduction in distribution (Holm and Mandrak 1996).

Global population size and status: There is little information available concerning the abundance of Eastern Sand Darter over its entire global range. The short-term rate of decline would be between 10% and 30%, whereas long-term decline ranges between 50% and 75% (Holm and Mandrak 2000). NatureServe (2009) estimates Eastern Sand Darter global abundance to be greater than 10,000 individuals.

The Eastern Sand Darter has experienced population declines throughout its global range (Page and Burr 1991, Holm and Mandrak 1996). It is considered globally secure (G4) (NatureServe 2009) and was designated as Vulnerable by The World Conservation Union (IUCN) in 1996 (Gimenez Dixon 1996).

The Eastern Sand Darter is not listed federally in the United States. The American Fisheries Society has designated this species as Vulnerable (Jelks et al. 2008). It is listed as Endangered in Pennsylvania (State of Pennsylvania 2010) and Threatened in Illinois (Illinois Department of Natural Resources 2010), New York (New York State Department of Environmental Conservation 2010), Michigan (Michigan Department of Natural Resources 2010) and Vermont (Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, 2010). It is considered a Species of Concern in Ohio (Ohio Department of Natural Resources 2010). It was previously listed as Special Concern in Indiana; however, it was down-listed after a state-wide survey in 2004 determined it to be well distributed (B. Fisher, pers. comm., 2005).

Figure 3. Ontario distribution of the Eastern Sand Darter.

Description of Figure 3

Canadian population size and status: In Canada, Eastern Sand Darter population sizes are unknown, but numbers are nevertheless in decline since 1950 according to estimates. Holm and Mandrak (2000) estimated that the rate of decline would have reached 50% between 1955 and 1970. They also estimated that the species' extent of occurrence (based on the length in km of the rivers occupied by the species) was less than 20,000 km2. The Extent of Occurrence is 10,840km2 (COSEWIC 2010).

The Eastern Sand Darter is listed as Threatened on Schedule 1 of the Canadian Species at Risk Act (SARA). It is ranked N3 in Canada and the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) designated it as Threatened. It is listed as Endangered in Ontario under the Endangered Species Act 2007 (ESA 2007) (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) 2010). It is listed as Threatened in Quebec by the Ministère des Ressources Naturelles et de la Faune (MRNF) (in French only).See Table 1 for national and sub-national ranks.

| Rank level | Rank* | Jurisdictions |

|---|---|---|

| Global | G3 | |

| National | N4 | United States |

| N3 | Canada | |

| Sub-national | S4 | Indiana, Kentucky |

| S3 | Ohio | |

| S2S3 | West Virginia | |

| S2 | New York, Ontario, Quebec | |

| S1S2 | Michigan | |

| S1 | Illinois, Pennsylvania, Vermont |

*see appendix 1 for description of ranks

Percent of global abundance in Canada: No global or Canadian abundance estimates have been undertaken.

Population trend: The Eastern Sand Darter was presumed common and widespread in the early 1900s (Holm and Mandrak 1996). However, it is estimated to have disappeared from half of its historical locations and its abundance reduced in remaining populations.

The recovery potential assessment of Eastern Sand Darter populations in Canada was assessed by Bouvier and Mandrak (2010). A summary is provided in Table 2. Populations were ranked with respect to abundance and trajectory. Population abundance and trajectory were then combined to determine the population status. A certainty level was also assigned to the population status, which reflected the lowest level of certainty associated with either population abundance or trajectory. Refer to Bouvier and Mandrak (2010) for further details on the methodology.

| Area | PopulationFootnote 1 | Relative abundance index | Certainty* | Population trajectory | Certainty | Population status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lake Huron | Ausable River | Extirpated | 2 | Not applicable | 2 | Extirpated |

| Lake St. Clair | Lake St. Clair | Low | 2 | Declining | 3 | Poor |

| Lake St. Clair | Thames River | High | 1 | Stable | 1 | Good |

| Lake St. Clair | Sydenham River | Low | 2 | Unknown | 3 | Poor |

| Lake Erie | Pelee Island | Unknown | 3 | Unknown | 3 | Unknown |

| Lake Erie | Rondeau Bay | Unknown | 3 | Unknown | 3 | Unknown |

| Lake Erie | Long Point Bay | Low | 2 | Declining | 2 | Poor |

| Lake Erie | Catfish Creek | Extirpated | 3 | Not applicable | 3 | Extirpated |

| Lake Erie | Big Otter Creek | Extirpated | 3 | Not applicable | 3 | Extirpated |

| Lake Erie | Big Creek | Low | 3 | Unknown | 3 | Poor |

| Lake Erie | Grand River | High | 2 | Stable | 2 | Good |

(modified from Bouvier and Mandrak 2010)

*Certainty is listed as: 1=quantitative analysis; 2=CPUE or standardized sampling; 3=best guess

Spawning habitat description: Spawning generally occurs at temperatures between 20.5 and 25.5° C (Johnston 1989, Facey 1995, 1998). Based on gonadal examination, Holm and Mandrak (1996) estimated spawning in Ontario to occur between late June and late July but may be as early as late April (Finch 2009), or as late as mid-August as seen in the United States (Spreitzer 1979, Johnston 1989, Facey 1995, 1998). Spawning has not been observed in the wild. In the laboratory, Eastern Sand Darter has spawned on substrates that were a mixture of sand and gravel (Johnston 1989). Spawning does not seem to depend on time of day.

Young of the Year (YOY) and juvenile habitat description: There is little known about YOY and juvenile habitat requirements, but recently transformed juveniles have been caught in the same habitat as the adults (A. Dextrase, unpublished data). Simon and Wallus (2006) found that early juveniles were more tolerant of the silt margins than adults. Drake et al. (2008) found that juvenile growth was faster in habitats with less silt. There is some evidence that Eastern Sand Darter have a larval drift phase which means it's important to have suitable nursery habitat downstream of spawning areas (Simon and Wallus, 2006).

Adult habitat description: The Eastern Sand Darter inhabits streams, rivers and sandy shoals in lakes, and is typically strongly associated with fine sandy substrates and fine gravel (greater than 90% sand) (Daniels 1993, Facey 1995, Facey and O'Brien 2004, Drake et al. 2008). Abundance is greatest on the depositional side of bends along small- to medium-sized rivers with a gentle current and minimal fine sediment deposition (Trautman 1981, Facey 1995). Few fishes of temperate streams are as strongly associated with a specific habitat type as this species. Daniels (1993) found the nearest neighbouring fish was overwhelmingly (93%) another Eastern Sand Darter, showing also that individuals aggregate in areas of suitable habitat. Eastern Sand Darter are also found near sandbars, in shallow pools (Welsh and Perry 1997), in the sandy raceways of streams and rivers (Kuehne and Barbour 1983, Page 1983).

Lentic populations of Eastern Sand Darter in lakes Erie and St. Clair are typically associated with nearshore habitats such as wave-protected sandy beaches, sandy shores and shallow bays (van Meter and Trautman 1970, Thomas and Haas 2004, Gaudreau 2005). Additionally, young-of-the-year surveys indicate that Eastern Sand Darters were found at river/stream mouths (unpub. data, MNR)

The Eastern Sand Darter was thought to be typically found in shallow habitats. Facey (1995) did not find Eastern Sand Darter in deep habitats characterized by high velocities and coarser sand. Lack of capture from deep habitats may be, in part, an artefact of sampling method and accessibility rather than habitat preference (i.e., choice of sampling stations is typically dictated by accessibility) (Daniels 1993, Facey 1995, Welsh and Perry 1997, O'Brien and Facey 2008, Drake et al. 2008). In Lake Erie, Scott and Crossman (1973) reported a trawl-caught individual at a depth of 14.6m and more than 100 individuals were caught in the Grand River in depths > 1.5m (N. Mandrak, pers. com., 2010). However, Eastern Sand Darter were not captured during the systematic trawl sampling of western Lake St. Clair in water deeper than 2m (Thomas and Haas 2004)

The Eastern Sand Darter is one of the rare species that exploits sandy habitats and related resources. It is also the only member of the genus Ammocrypta in Canada and, consequently, an integral part of Canada's wildlife heritage. In addition to contributing to the biodiversity of aquatic ecosystems, this species is an indicator of unpolluted streams (Gaudreau 2005).

The Eastern Sand Darter is not very flexible in terms of habitat needs (i.e., it is dependent on silt-free sand), thus it is vulnerable to any factor likely to affect its habitat (Holm and Mandrak 2000, Grandmaison et al. 2004, Gaudreau 2005, NatureServe 2006). The Eastern Sand Darter is a small fish with limited dispersal ability that exists as a collection of disjunct populations in Canada. Therefore, extirpated populations have little opportunity to be re-established through natural movements.

The fecundity of the Eastern Sand Darter is low (clutch sizes of 35-123 mature ova) (Finch 2009), which could contribute to yearly population fluctuations (Facey 1998) and population declines. Females reach sexual maturity at about one year (42mm TL) (Spreitzer 1979) and generally live for over two years. Females older than three have been found on the Thames River (Finch 2009).

Bouvier and Mandrak (2010) assessed threats to Eastern Sand Darter populations in Canada. Table 3 provides a summary of threats to Eastern Sand Darter populations in Ontario. Known and suspected threats were ranked with respect to threat likelihood and threat impact for each population. The threat likelihood and threat impact were then combined to produce an overall threat status. A certainty level was also assigned to the overall threat status, which reflected the lowest level of certainty associated with either threat likelihood or threat impact. See Bouvier and Mandrak (2010) for further details. Additional information is provided in the subsequent threat descriptions.

Threat Status for all Eastern Sand Darter populations in Ontario, resulting from an analysis of both the Threat Likelihood and Threat Impact. The number in brackets refers to the level of certainty assigned to each Threat Status, which reflects the lowest level of certainty associated with either initial parameter (Threat Likelihood, or Threat Impact). Certainty has been classified as: 1= causative studies; 2=correlative studies; and 3=expert opinion. Gray cells indicate that the threat is not applicable to the population due to the nature of the aquatic system where the population is located.

(Table taken from Bouvier and Mandrak 2010)

The following has been adapted and revised from Bouvier and Mandrak (2010).

Turbidity and sediment loading: Siltation may be the leading cause of habitat degradation in Canada (Holm and Mandrak 1996). Increased turbidity and sediment loading can result from deforestation and the loss of riparian strips, which is often a result of intensive agricultural practices, tile drainage, channel alterations, poorly constructed water crossing, dams, and increasing urban development. The increased sediment loading can decrease bank stability downstream which also increases erosion downstream and the process can continue for extended distances (Dextrase et al. 2003).

The impacts of silt are pervasive and extensive. Excessive siltation can affect all life stages of the Eastern Sand Darter (COSEWIC 2010). Increased turbidity and sediment loading can:

- Completely smother the eggs (Finch 2009);

- Reduce the number and quality of suitable spawning areas leading to decreases in egg survival (Finch 2009);

- Decrease or restrict growth rates of juveniles (Drake et al. 2008);

- Reduce available substrate oxygen (Holm and Mandrak 1996, Essex-Erie Recovery Team (EERT) 2008); and,

- Adversely affect prey abundance (Holm and Mandrak 1996, EERT 2008).

It is thought that standard tobacco farming practices between the 1930s – 1960s near Big Otter Creek, which resulted in heavy siltation, may have been the main reason for the extirpation of Eastern Sand Darter from this watershed (Holm and Mandrak 1996). The relatively few areas of silt-free suitable habitat in the Sydenham River may be the main limiting factor for Eastern Sand Darter in this system (Dextrase et al. 2003). However, the impacts from increased turbidity and sediment loading may be reversible, if caught early, as populations of Eastern Sand Darter in Vermont and New York have benefited from decreased silt loads as a result of reforestation of stream slopes (Daniels 1993).

Contaminants and toxic substances: Contaminants and toxic substances are a pervasive threat for Eastern Sand Darter (COSEWIC 2010). These substances can come from urban, industrial or agricultural activities. Their presence in aquatic environments leads to decreased water quality and can have a negative impact on each stage of a fish's life cycle. The severity of impacts is likely linked to duration and intensity of exposure. Contaminants can directly kill the individual, its food or can slowly degrade the watercourse affecting all life history parameters. Contaminants can be chronic or episodic and may also be cumulative (EERT 2008).

The Eastern Sand Darter is considered to be intolerant to pollution (Barbour et al. 1999) but species-specific tolerances have not been investigated. Since the Eastern Sand Darter buries itself and its eggs in the substrate, the consequence of toxic substances may be greater on Eastern Sand Darter than other fishes (Grandmaison et al. 2004).

Nutrient loading: Nutrient loading can have impacts on water quality, especially in riverine systems. One pathway is through the eutrophication of streams. The excessive growth of aquatic plants, algae, or periphyton can reduce the amount of oxygen found in the water, which threatens benthic species such as the Eastern Sand Darter (FAPAQ 2002). Nutrient loading primarily comes from manure and fertilizer applications or sewage treatment facilities (Page and Retzer 2002). Between 1955 and 1980, Lake Erie experienced excessive nutrient input and one of the results was the observation of extensive oxygen depletion (Koonce et al. 1996)

In the Ausable, Sydenham, and Thames rivers (Staton et al. 2003, Taylor et al. 2004, Nelson 2006) and in Lake St. Clair and Lake Erie (EERT 2008), nutrient loading has been identified as a primary threat to species at risk. In the Sydenham River, high levels of nitrates have been associated with low numbers of Eastern Sand Darter (Poos et al. 2008).

Barriers to movement: Dams are the most obvious, but not the only, barrier to movement for Eastern Sand Darter. Improperly designed and installed culverts could create a physical barrier or may preclude the Eastern Sand Darter from being able to move upstream due to high velocities or shallow water depth in the culvert. This may be relevant if Eastern Sand Darter are found in smaller tributaries where culverts are common. There are two large dams on the Grand River, and one dam on the Sydenham River within the range of Eastern Sand Darter. Data from the Grand River show that on the upstream side of a dam, locations close to the dam are less likely to be occupied by Eastern Sand Darter (A. Dextrase, unpublished data).

Barriers to movement could lead to the fragmentation of Eastern Sand Darter populations. Small, increasingly isolated populations may suffer inbreeding effects and a loss of genetic diversity that could impair their ability to respond to changing environmental conditions (Grandmaison et al. 2004).

Altered flow regimes: There are many activities that can alter the flow within a riverine system, such as the presence of a dam and impoundment, water-taking for agricultural or urban purposes, construction of tile drains, or channel modifications.

The construction of a dam changes the stream flow by transforming a lotic (moving water) environment into a lentic (standing water) environment, flooding upstream riffles and sandbars and allowing the growth of aquatic macrophytes. When the current's speed is slowed or eliminated, sedimentation increases. In addition, dams increase sedimentation by mitigating spring freshets (Grandmaison et al. 2004). Dams can also produce scouring flows downstream contributing to unnaturally high bank erosion. They can interfere with the natural variation in the magnitude, frequency, timing, and variability in flows.

Eastern Sand Darter requires habitat with predominantly sand substrate. These are usually depositional areas (Daniels 1989, Holm and Mandrak 1996). A specific or narrow flow regime may be required to maintain sand but not silt in these depositional areas. The loss of natural channels and flow regimes may have a large impact on Eastern Sand Darter (Dextrase et al. 2003).

Shoreline modifications: In lakes Erie and St. Clair, Eastern Sand Darter has been collected from nearshore habitats such as wave-protected sandy beaches, sandy shores and shallow bays (van Meter and Trautman 1970, Thomas and Haas 2004). Shoreline hardening has affected natural erosion processes and, thereby, altered nearshore sediment transport (Edsall and Charlton 1997). Disruption of sediment transport and deposition processes may reduce the availability of nearshore habitats with suitable sand habitat. Dredging of river mouths that drain into Lake St. Clair has the potential to directly alter habitat, increase turbidity and trap individuals in the dredgate.

The shoreline of Lake St. Clair has been substantially altered mainly through the installation shorewalls, offshore breakwalls, groynes, jetties, docks and marinas (Reid and Mandrak 2008). Those areas that have not been hardened or filled have been dredged for human use (EERT 2008).

In riverine systems, shoreline modifications are typically bank hardening, channel realignments, agricultural drain creation and maintenance and the installation of docks and marinas. Shore erosion combined with agricultural fields (e.g., ploughed land) or from tile drainage brings fine particles to the streams that build up in the bottoms of streams and rivers. Furthermore, the channelization of streams changes the physical processes which can alter the formation of sandbars, which are often associated with the occurrence of Eastern Sand Darter (Société de la faune et des parcs du Québec (FAPAQ) 2002, Gaudreau 2005). Tile drainage is a serious threat to Eastern Sand Darter in southwestern Ontario, as it can speed up the surface and subsurface water flow into drains, causing even greater erosion of drains or channels.

As discussed in altered flow regimes above, all of these types of activities (such as the presence of a dam and impoundment, water-taking for agricultural or urban purposes, construction of tile drains, or channel modifications) have the potential to alter flow regimes and the natural channel processes, which may have a substantial impact on Eastern Sand Darter (Dextrase et al. 2003).

Exotic species and disease: Round Goby (Neogobius melanostomus), an exotic species, can cause considerable harm in North American aquatic ecosystems. Since its discovery in the St. Clair River in 1990, this species has quickly colonized the Great Lakes basin (Bernatchez and Giroux 2000, Poos et al. 2010). The Round Goby spawns several times throughout the summer and is tolerant of polluted waters; these characteristics may give it a competitive edge over native species. This is a benthic species that, once established, could have a direct impact on darter species (Bernatchez and Giroux 2000).

The ranges of the Eastern Sand Darter and Round Goby overlap in Lake St. Clair (since 1993), the lower Thames River, Sydenham River, Big Creek and Lake Erie (since 1996) and Round Goby have recently colonized the Grand River system. Since its introduction into the lower Great Lakes, the Round Goby has been implicated in the declines of native benthic fish species such as: Logperch (Percina caprodes) and Mottled Sculpin (Cottus bairdii) populations in the St. Clair River (French and Jude 2001); Johnny Darter (Etheostoma nigrum), Logperch and Trout-Perch (Percopsis omiscomaycus) in Lake St. Clair (Thomas and Haas 2004); and, Channel Darter (Percina copelandi), Fantail Darter (E. flabellare), Greenside Darter (E. blennioides), Johnny Darter and Logperch in the Bass Islands of western Lake Erie (Baker 2005). Preliminary evidence from the lower Grand River notes a negative realtionship between the abundances of Round Goby and Eastern Sand Dearter based on 1 year of data. (A. Dextrase, unpublished data). Potential causes of declines of native species include goby predation on eggs and juveniles, competition for food and habitat, and interference competition for nests (French and Jude 2001, Janssen and Jude 2001, Poos et al. 2010).

Round Goby has been caught in all Eastern Sand Darter river systems in Ontario (A. Dextrase, pers. comm., 2010). The full impacts of the introduction of Round Goby in Eastern Sand Darter locations may not be determined for years since Round Goby populations are still actively colonizing the river systems.

Incidental harvest: The use of Eastern Sand Darter as a baitfish is illegal in Ontario (OMNR 2010). Although Eastern Sand Darter is not a target baitfish, incidental harvest may occur due to co-occurrences (i.e., distributional overlap) between Eastern Sand Darter and some target bait species (e.g., Common Shiner Luxilus cornutus, Creek Chub Semotilus atromaculatus, White Sucker Catostomus commersonii). Although baitfish harvest may theoretically occur from a variety of riverine and Great Lakes nearshore localities that may support Eastern Sand Darter, these specific localities of Eastern Sand Darter occurrences are not preferentially harvested. An intensive sampling program of 68 retail tanks and baitfish purchases, examining 16,886 fishes, did not find any Eastern Sand Darter (A. Drake, University of Toronto, pers comm. 2010). This does not mean that they are not caught but that they are not being sold in the commercial harvest.

Expert opinion (Bouvier and Mandrak, 2010) is that baitfish harvesting is an activity with a minimal impact on Eastern Sand Darter populations and is an activity that may be permitted (see Section 2.8).

Surveys: A summary of surveys conducted for Eastern Sand Darter in recent years is provided in Table 4.

| Waterbody | Recent surveys* |

|---|---|

| Ausable River | Targeted and non-targeted sampling by DFO, OMNR, ABCA using seine, backpack electrofisher and boat electrofisher (2002). |

| Catfish Creek | Targeted and non-targeted sampling by DFO, OMNR, ROM, University of Guelph using seine and boat electrofisher (1997, 2002, 2008). |

| Big Otter Creek | Targeted and non-targeted sampling by DFO, OMNR and University of Guelph using seine (2002 – 04, 2008). |

| Big Creek | Targeted sampling by DFO and OMNR using seine (2004). |

| Sydenham River | Targeted and non-targeted sampling by DFO, OMNR, ROM and University of Guelph using seine, backpack and boat electrofisher (1997 - 99, 2002 – 04, 2009). |

| Grand River | Targeted and non-targeted sampling by DFO, OMNR, ROM and Trent University using seine, backpack electrofisher, boat electrofisher and trawl (1997, 1999 – 2000, 2002, 2004, 2006 – 10). |

| Thames River | Targeted and non-targeted sampling by DFO, University of Waterloo and Trent University using seine and trawl (1997 – 98, 2003 – 09). |

| Lake Erie | Non-targeted sampling by DFO, OMNR and Parks Canada (Long Point Bay, Rondeau Bay and Point Pelee) using seine and trawl (1997 – 2008). |

| Lake St. Clair | Non-targeted sampling by DFO, OMNR and Michigan DNR using seine and trawl (1997 – 2001, 2005, 2007, 2008). |

*Non-targeted sampling includes, but is not limited to, general species at risk sampling and monitoring, fish community surveys, and index netting programs.

Aquatic ecosystem-based recovery strategies: The following aquatic ecosystem-based recovery strategies include the Eastern Sand Darter and are currently being implemented by their respective recovery teams. Each recovery team is co-chaired by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and a Conservation Authority and receives support from a diverse partnership of agencies and individuals. Recovery activities implemented by these teams include active stewardship and outreach/awareness programs to reduce identified threats; for further details on specific actions currently underway, please refer to the approaches identified in Table 5. Funding for these actions is supported by Ontario's Species at Risk Stewardship Fund and the Government of Canada's Habitat Stewardship Program (HSP) for species at risk. Additionally, research requirements for species at risk identified in recovery strategies are funded, in part, by the federal Interdepartmental Recovery Fund (IRF).

Sydenham River Ecosystem Recovery Strategy:

The primary objective of the Sydenham River Ecosystem Recovery Strategy is to “sustain and enhance the native aquatic communities of the Sydenham River through an ecosystem approach that focuses on species at risk” (Dextrase et al. 2003). The recovery strategy focuses on the 16 aquatic species at risk within the basin, including the Eastern Sand Darter.

Thames River Ecosystem Recovery Strategy:

The goal of the Thames River Recovery Team is to develop “a recovery plan that improves the status of all aquatic species at risk in the Thames River through an ecosystem approach that sustains and enhances all native aquatic communities” (TRRT 2004). The Eastern Sand Darter is one of 25 aquatic species at risk included in this strategy.

Grand River Fish Species at Risk Recovery Strategy:

The goal of Grand River Fish Species at Risk Recovery Team is to “conserve and enhance the native fish community using sound science, community involvement and habitat improvement measures” (Portt et al. 2007). Included in this strategy are recovery initiatives for the Eastern Sand Darter and five other fish species at risk.

Ausable River Ecosystem Recovery Strategy:

The long-term goal of the Ausable River Ecosystem Recovery Strategy is “to sustain a healthy native aquatic community in the Ausable River through an ecosystem approach that focuses on the recovery of species at risk” (ARRT 2005). The Ausable River Recovery Team has developed a recovery strategy for the 14 aquatic species at risk in the Ausable River basin, including the Eastern Sand Darter.

Essex-Erie Recovery Strategy:

The goal of the Essex-Erie Recovery Strategy is “to maintain and restore ecosystem quality and function in the Essex-Erie region to support viable populations of fish species at risk, across their current and former range” (EERT 2008). Included in this strategy are recovery initiatives for the Eastern Sand Darter and 17 other fish species at risk.

Research: University graduate students (University of Waterloo and Trent University) are researching life-history characteristics and conducting population and habitat modeling of southwestern Ontario Eastern Sand Darter populations (2005-present).

Great Lakes outreach program: The Toronto Zoo has included the Eastern Sand Darter as part of its awareness and curriculum-based education Great Lakes Outreach Program.

In Canada, the Eastern Sand Darter has never been thoroughly studied. The few recent studies on Eastern Sand Darter in Ontario (Drake et al. 2008, Finch 2009, A. Dextrase, unpublished data) have provided some answers, but also raised additional questions. Knowledge gaps concerning this species can be attributed to its scarcity, small size, benthic and burrowing lifestyle as well as its translucency, which make the Eastern Sand Darter rarely seen or caught.

Knowledge acquisition on the biology (clutch size and fecundity), behaviour, adaptability as well as the species' population dynamics and abundance in Canada is therefore critical to implement recovery measures. Additional baseline data regarding habitat needs (tolerance to temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen and pollution), distribution and threats (including severity of threats) to the species' survival will be necessary in order to examine and monitor Eastern Sand Darter population trends.