Recovery Strategy for the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferus) in Canada - 2015 - Proposed

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Executive Summary

- Recovery Feasibility Summary

- 1. COSEWIC, Species Assessment Information

- 2. Species Status Information

- 3. Species Information

- 4. Threats

- 5. Population and Distribution Objectives

- 6. Broad Strategies and General Approaches to Meet Objectives

- 7. Critical Habitat

- 8. Measuring Progress

- 9. Statement on Action Plans

- 10. References

Environment Canada. 2015. Recovery Strategy for Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferus) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. vii + 57 pp.

For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including COSEWIC Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk Public Registry.

Cover illustration: © H. Loney Dickson

Également disponible en français sous le titre :

« Programme de rétablissement de l’Engoulevent bois-pourri (Antrostomus vociferus) au Canada [Proposition] »

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of the Environment, 2015. All rights reserved.

ISBN

Catalogue no.

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress five years after the publication of the final document on the SAR Public Registry.

The Minister of the Environment and Minister responsible for the Parks Canada agency is the competent minister under SARA for the Eastern Whip-poor-will and has prepared this strategy, as per section 37 of SARA. To the extent possible, it has been prepared in cooperation with the provinces of Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario (Ministry of Natural Resources), Quebec (Ministère des Forêts, de la Faune et des Parcs), New Brunswick and Nova Scotia as per section 39(1) of SARA.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment Canada and the Parks Canada Agency, or any other jurisdiction alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Eastern Whip-poor-will and the Canadian society as a whole.

This recovery strategy will be followed by one or more action plans that will provide information on recovery measures to be taken by Environment Canada, the Parks Canada Agency, and other jurisdictions and/or organizations involved in the conservation of the species. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

This recovery strategy was prepared by Vincent Carignan (Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service [EC-CWS]– Quebec region) and Mireille PoulinFootnote1 based on an initial draft by Kimberley Hair and Madison Wikston (EC-CWS- National Capital region) and in collaboration with:

Additional thanks go to: Maureen Toner (New Brunswick Departement of Natural Resources), Audrey Heagy (Bird Studies Canada – Ontario); Narayan Dhital (Forest Service, Saskatchewan); all other parties including Aboriginal organizations, landowners, citizens, and stakeholders who provided comments on the present document as well as Regroupement QuébecOiseaux, EC-CWS and Bird Studies Canada for providing the data from the Breeding Bird Atlases in Canada, and the thousands of volunteers that collected data for those projects.

The Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferus) is a nocturnal insectivorous bird that breeds in sparse forests or at the edge of forests adjacent to open habitats required for foraging. The species was designated as Threatened by the Committee for the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in 2009 and has been listed under the same status in Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA) since 2011.

An estimated 120 000 Eastern Whip-poor-will individuals (6% of the global population) are found in Canada, where they breed in southern Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island. National and provincial population trends indicate a decline between 2.77% and 5.53% per year over the 2002-2012 period.

Although our understanding of the causes of the decline of the Eastern Whip-poor-will may be limited, the main threats include reduced availability of insect prey, agricultural expansion and intensification (wintering and breeding grounds), urban expansion, as well as energy development and mineral extraction. Other threats that contribute to a lesser extent are also presented.

There are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of the Eastern Whip-poor-will. Nevertheless, in keeping with the precautionary principle, a recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA as would be done when recovery is determined to be feasible.

The population and distribution objectives for the Eastern Whip-poor-will in Canada are:

- In the short term: Slow the decline such that the population does not decrease by more than 10% (i.e. 12 000 individuals) over the 2015-2025 period, and maintain the area of occupancy at 3,000 km2 or above;

- In the long term: Ensure a positive 10-year population trend starting in 2025, while favouring an increase in the area of occupancy, including the gradual recolonization of areas in the southern portion of the breeding distribution.

Broad strategies and approaches to achieve these objectives are presented in the Strategic Direction for Recovery section.

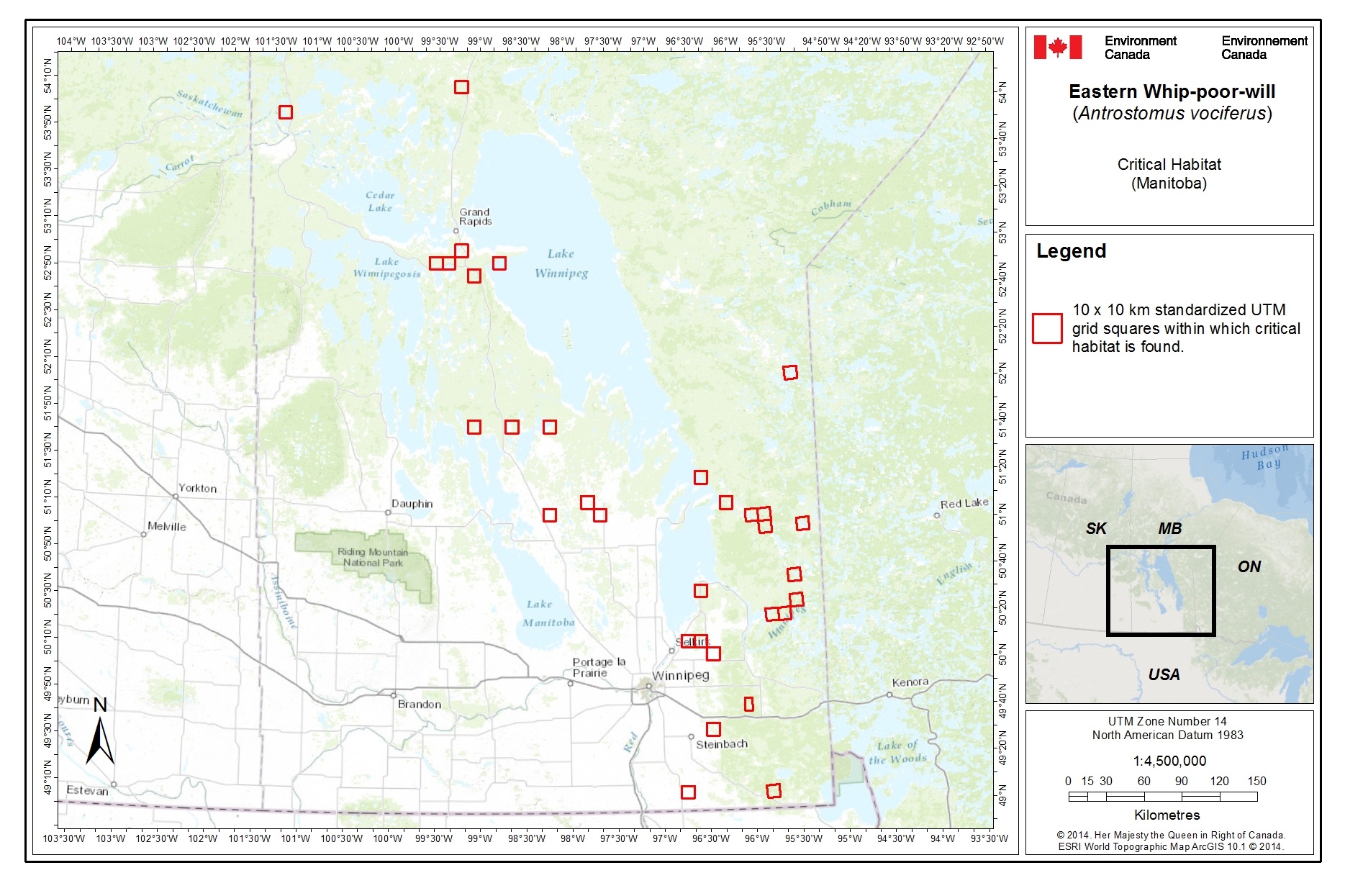

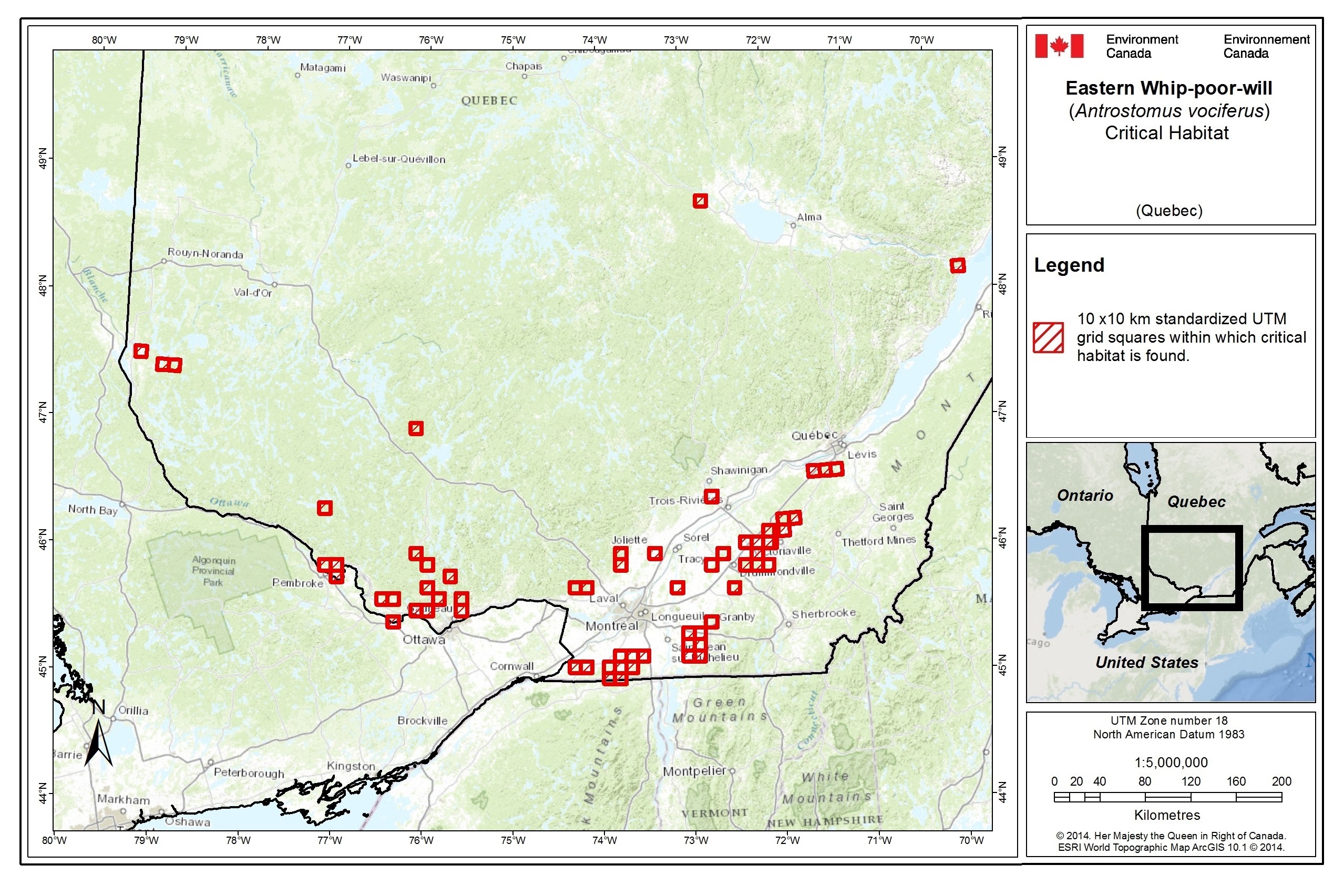

Critical habitat for the Eastern Whip-poor-will is partially identified in this recovery strategy. It corresponds to the areas of suitable nesting and/or foraging habitats within all 10 x 10 km standardized Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) squares with confirmed breeding or multiple occupancy since 2001. Overall, 212 critical habitat units are identified for the Eastern Whip-poor-will, including 32 in Manitoba, 110 in Ontario, 65 in Quebec, and five in the Maritimes (all in New Brunswick). A schedule of studies outlines the activities required to complete the identification of critical habitat.

One or more action plans will be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry before the end of 2020.

Based on the following four criteria that Environment Canada uses to establish recovery feasibility, there are unknowns regarding the feasibility of recovery of the Eastern Whip-poor-will. Therefore, in keeping with the precautionary principle, this recovery strategy has been prepared as per section 41(1) of SARA as would be done when recovery is determined to be feasible. This recovery strategy addresses the unknowns surrounding the feasibility of recovery.

- Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance.

Yes. Breeding individuals are currently distributed in multiple areas of the Canadian breeding distribution as well as in the United States. - Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

Unknown. Sufficient suitable breeding habitat is available to support the species at its current level. Unoccupied and apparently suitable habitat appears to be available and additional habitats could become suitable after restoration efforts or through natural processes (e.g., succession, fires) or human activities (e.g., forest harvesting). The availability of sufficient amounts of migrating and wintering habitats is unknown. - The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

Unknown. Clarifying the impacts of some of the threats, namely the existence of possible thresholds in habitat loss as well as in the availability of insect prey populations would help establish more precise beneficial management practices. It is unknown whether threats such as reduced insect prey populations and threats to the wintering areas can be mitigated. - Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe.

Unknown. Habitat conservation and stewardship, along with habitat management techniques, could be effective for this species although specific management practices need to be developed and implemented. Mitigating threats, such as reduced insect prey populations and habitat availability on the wintering areas represent considerable challenges.

Assessment Summary

Approximately 6% of the global population and 20% of the breeding distribution of the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferous) is found in Canada (COSEWIC 2009; Partners in Flight Science Committee 2013). The species was listed as Threatened on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA; S.C. 2002, c. 29) in April 2011. It is listed as Threatened under three provincial Endangered Species Acts: Ontario (S.O. 2007, c. 6), Nova Scotia (S.N.S. 1998, ch. 11), and Manitoba (C.C.C.S.M. c. E111, 1990), as well as under New Brunswick’s Species at Risk Act (SNB 2012, c. 6). In Quebec, the species is listed as Likely to be designated as Threatened or vulnerable on the List of Wildlife Species Likely to be Designated Threatened or VulnerableFootnote3 produced according to the Act Respecting Threatened or Vulnerable Species (CQLR, c. E-12.01). As of November 2014, the species was not listed in Saskatchewan nor Prince Edward Island.

NatureServe (2014) considers the global populations of the Eastern Whip-poor-will to be Secure (G5). The species’ breeding populations are Apparently Secure (N4B) in Canada and Secure (N5B) in the United States. Table 1 provides further details on other conservation ranks in Canada.

| Region | Nature Serve Table notea |

|---|---|

| Saskatchewan | Vulnerable (S3B) |

| Manitoba | Vulnerable (S3B) |

| Ontario | Apparently Secure (S4B) |

| Quebec | Vulnerable (S3) |

| New Brunswick | Imperiled (S2B) |

| Prince Edward Island | Non-breeder (SNA) |

| Nova Scotia | Critically Imperiled (S1?B) |

The scientific name of the Eastern Whip-poor-will has been modified twice following the publication of the COSEWIC status report (2009). Initially, the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Caprimulgus vociferus vociferus) was considered a subspecies of the Whip-poor-will and encompased all the eastern populations of the species’ breeding distribution. In 2010, it was separated from its close relative, the Mexican Whip-poor-will (Caprimulgus arizonea), to form a new species by itself, the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Caprimulgus vociferus) (Chesser et al. 2010). In 2012, the Antrostomus genus name, that was used for this species until 1931, was restored for the Eastern Whip-poor-will (refer to Chesser et al. 2012 for further details).

Cink (2002) describes the Eastern Whip-poor-will as a nocturnal aerial insectivorous bird of the Caprimulgidae family (typical nightjars). It measures around 24 cm long and weighs 50 to 55 g. Its plumage is grey and brown, which serves to blend individuals with elements of the forest ground where they nest. Individuals have rounded wings and tail feathers and a large and flattened head with a small bill and big gape, bordered by long sensory bristles. Males differ from females in that they have a white collar and two big white patches on their outer tail feathers (smaller and buff-colored in females). Eastern Whip-poor-wills bear a striking resemblance to Common Nighthawks but lack the white patches on the wings and vocalizations are very distinct. As nocturnal birds, individuals are more often heard than seen and their distinct three-noted song “WHIP-poor-WEEL” is at the origin of the species’ name.

The global breeding distribution of the Eastern Whip-poor-will is approximately 2 772 000 km2 (COSEWIC 2009). It extends from Saskatchewan to the Maritimes and south in the United States, west to east from Oklahoma to Georgia (Cink 2002; Figure 1). The Eastern Whip-poor-will breeds locally throughout its range and no northward range expansion has been noted (Cink 2002). The global population is estimated at 2 million individuals (Partners in Flight Science Committee 2013). The Eastern Whip-poor-will’s overwintering range stretches from coastal South Carolina through Florida and along the Gulf Coast of the United States into Mexico and Central America as far south as Honduras and Panama (Cink 2002; Figure 1).

The Canadian breeding distribution occupies around 535 000 km2 (20% of the global breeding distribution) (COSEWIC 2009) from east-central Saskatchewan, southern Manitoba, southern Ontario, southern Quebec, and sparse locations in New Brunswick, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island (Godfrey 1986; Cink 2002; Maritimes Breeding Bird Atlas 2013). The Canadian population is estimated at 120 000 individuals, with the highest concentrations found in eastern Ontario (Partners in Flight Science Committee 2013). Although this estimate incorporates atlas data, it is mainly based on data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS), and is considered to have relatively low accuracy for the Eastern Whip-poor-will as this survey program is not designed to detect nocturnal birds (Partners in Flight Science Committee 2013). Also, the Breeding Bird Survey data does not sample the species’ entire range at random, having lower coverage in more remote areas.

Figure 1: Global range of the Eastern Whip-poor-will, which includes the breeding, overwintering and migration distributions (Cornell Lab of Ornithology, 2007)

Long description for Figure 1

Figure 1 illustrates the area covered by each type of distribution. In summer, the species is found in parts of southern Quebec and Ontario, in a small patch in the Canadian prairies, as well as the eastern half of the United-States down to Tennessee approximately. The winter distribution follows the coast of the south-eastern United-States from North-Carolina into Mexico and down to Costa-Rica.

The Eastern Whip-poor-will’s range within Canada has been retracting since the mid-1960s, most notably at its southern limit (Smith 1996; COSEWIC 2009). A comparison of the data from the first and second breeding bird atlases in Ontario and the Maritimes show a similar trend (Table 2). Although the atlas records have yet to be compiled for the last survey year of the second breeding bird atlas in Quebec, results indicate a slight increase in occupancy (Table 2). Differences in atlas square occupancy between successive atlases should be considered with caution as they can be the result of different levels of effort to detect the species.

Using BBS data, a Canada-wide population decline of 3.19% per year has been noted over the 1970-2012 period, or an approximate loss of 75% of the population (Environment Canada 2014a). Over the 2002-2012 period, this national trend has slightly slowed to a decline of 2.77% per year. Regional BBS trends for Ontario and Quebec, the core of the species’ distribution in Canada, are consistent with the national trend (Table 2). Data from the Quebec check-list program (Étude des populations d’oiseaux du Quebec - EPOQ) also corroborate these trends with a 2002-2011 population estimated to be about half that observed in the 1970’s (Larivée 2013). It should be noted that declines are observed not only at the species level but also among the guild of aerial insectivores and long-distance migrants to which the Eastern Whip-poor-will belongs (Blancher et al. 2009).

| Provinces | Atlas Periods |

Number of Occupied Atlas Squares (trend 1st vs 2nd atlas) |

BBS Annual Trends (1970-2012 / 2002-2012) |

Atlas References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saskatchewan | 1966-2014Footnotea.1Footnoteb | ~36 | Not available | Smith 1996; SBA |

| Manitoba | 2010-2013Footnoteb | 190 | Not available | www.birdatlas.mb.ca |

| Ontario | 1981-1985 | 885 | -3.45% / -3.36% | Cadman et al. 1987 |

| Ontario | 2001-2005 | 554 (-37%) |

-3.45% / -3.36% | Cadman et al. 2007 |

| Quebec | 1984-1989 | 168 | -5.26% / -5.53% | Gauthier and Aubry 1996 |

| Quebec | 2010-2013Table noteb | 179 (+7%) |

-5.26% / -5.53% | Atlas des oiseaux nicheurs du Québec 2014 |

| Maritimes | 1986-1990 | 62 (49 NB, 12 NS, 1 PE) |

+0.53% / -0.09% (NB)Table notec | Erskine 1992 |

| Maritimes | 2006-2010 | 38(-39%) (29 NB, 8 NS, 1 PE) |

+0.53% / -0.09% (NB)Table notec | Maritimes Breeding Bird Atlas 2013 |

Eastern Whip-poor-wills, like most forest birds, appear to rely on multi-scale considerations for habitat selection. Knowledge of the species’ requirements at the landscape scale as well as during migrations and on the wintering grounds are currently limited.

The amount of forest cover, by providing more areas suitable for breeding, as well as the spatial configuration of forest habitats next to more open habitats are often reported as central to the species’ presence (Roy and Bombardier 1996; Palmer-Ball 1996; Cink 2002, Wilson 2003; Garlapow 2007). Distance to larger forest tracts may also be important (Cink 2002), namely in more agricultural settings where the amount of nesting habitat is more limited.

The nesting and foraging habitats of the Eastern Whip-poor-will are usually defined by structural rather that compositional characteristics (Robbins 1994; Wilson and Watts 2008). Although the species is not considered particularly territorial, territory size ranges from 3 to 30 ha (Wilson 2003; Garlapow 2007; Hunt 2010) with a maximum value of 132.4 ha observed in central Ontario (mean 31 ha; Rand 2014). Home range size, the area within which birds are expected to be found most of the time as they conduct breeding activities, forage and move between these zones, can vary from 20 to 500 ha (mean 136 ha; Rand 2014). This is in line with Sandilands’ (2010) estimation that 500 to 1000 ha may be necessary to support “more than a few pairs”.

Nesting habitats include most types of forest at early stages of succession (or edges of forests with a dense tree cover but showing a similar structure at the ground level), rock or sand barrens with scattered trees, savannahs, old burns, as well as sparse conifer plantations (Wilson 1985; Bushman and Therres 1988; Cink, 2002; Mills 2007; Wilson and Watts 2008; Tozer et al. 2014). All these habitats exhibit characteristics such as well-drained soils, moderate tree cover (Godfrey 1986; Roy and Bombardier 1996; 26 to 83 % in Garlapow 2007) and moderate to sparse shrub and herbaceous cover (Eastman 1991; Garlapow 2007).

When woodlots are used for nesting (e.g., in agricultural landscapes), smaller isolated woodlots are not occupied by the species (Reese 1996), suggesting that there may be a threshold in forest patch size. However, Turpak et al. (2009) state that no threshold for size has been identified for the moment. Elevation also seems to play a role with the species usually being found at altitudes lower than 350 to 430 m (Cooper 1981; Robbins 1994; Roy and Bombardier 1996).

Although nests and eggs are very well camouflaged and rarely found, eggs are known to be layed directly on a thick bed of dead leaves (or bare ground), shaded by a short herbaceous plant, shrub or sapling (Roy and Bombardier 1996; Cink 2002), often near fallen tree limbs or rocks which can be used as perches to roost during the day (Cink 2002). Individuals appear to show a high degree of fidelity to nest sites (Cink 2002).

Foraging habitats include prairies, wetlands with shrubs, regenerating clearcuts as well as agricultural fields and other habitats with low tree cover and availability of foraging perches as these conditions favor the localisation of prey (lunar light) as well as foraging efficiency (Mills 1986; Garlapow 2007).

Foraging activities usually take place within 500 m of the nest, often near forest edges (Cink 2002; Garlapow 2007). However, at the northern edge of the species’ distribution, Rand (2014) showed significantly greater foraging distances that may result from reduced habitat quality and reduced flying insect abundance in regions where low temperatures hinder foraging activities.

Prey items consist mainly of large moths, scarab beetles and other nocturnal flying insects captured by sallying short distances from perches or picked directly on the ground (Tyler 1940; Cink 2002; Garlapow 2007).

Limiting factors influence a species’ survival and reproduction, and play a major role in the capacity to attain certain population levels (recover following a decline). For the Eastern Whip-poor-will, these include:

- Low annual productivity: although the species may double-brood in some areas in southern Canada, it generally has a single small clutch consisting of two eggs (Peck and James 1983; Sandilands 2010).

- High predation: as a ground nester, the species may be particularly vulnerable to nest predation (Cink 2002).

| Threat Category | Threat | Level of Concern Notea.23 | Extent | Occurrence | Frequency | Severity Noteb.13 | Causal Certainty Notec.13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat Loss or Degradation | Agricultural expansion and Intensification – wintering grounds | High | Widespread | Current | Continuous | Moderate | High |

| Habitat Loss or Degradation | Agricultural expansion and intensification – breeding grounds | Medium | Localised | Current | Continuous | Moderate | High |

| Habitat Loss or Degradation | Urban expansion | Medium | Localised | Current | Continuous | Moderate | Medium |

| Habitat Loss or Degradation | Energy development and mineral extraction | Medium | Localised | Current | Continuous | Moderate | Medium |

| Habitat Loss or Degradation | Overgrazing of forest understory | Low | Localised | Current | Continuous | Moderate | Medium |

| Habitat Loss or Degradation | Forest management | Low | Widespread | Current | Continuous | Low | Low |

| Changes in Ecological Dynamics or Natural Processes | Reduced availability of insect prey | High | Widespread | Current | Continuous | Unknown | Medium |

| Changes in Ecological Dynamics or Natural Processes | Fire suppression | Low | Localised | Current | Recurrent | Low | Low |

| Natural Processes or Activities | Habitat succession | Medium | Localised | Current | Continuous | Moderate | Medium |

| Climate and Natural Disasters | Climate change | Medium | Widespread | Current | Continuous | Unknown | Medium |

Threats are listed in decreasing order of level of concern. It should be noted that there are knowledge gaps relating to the quantitative impacts of some of the threats, particularly during migrations and on the wintering grounds. Secondary threats are not discussed in the present recovery strategy, namely collisions (e.g., with vehicles along roads), predation, interspecific competition (Chuck-will’s willow [Antrostomus carolinensis]) and invasive species (exotic earthworms).

The decline of aerial insectivores has been more obvious since the 1980s (Goldstein et al. 1999; Boettner et al. 2000; Wickramasinghe et al. 2004; Sauer et al. 1996; Blancher et al. 2007) and strongly suggests a cause related to changes in aerial insect populations on the breeding grounds, migration routes or wintering grounds (Nebel et al. 2010; Paquette et al. 2014). Indeed, insect populations are exhibiting significant declines worldwide, including in the United States (Laughlin and Kibbe 1985; Peterson and Meservey 2003). A recent review of global faunal population trends, noted that 33% of all insects with available IUCN-documented population trends were declining and many also exhibited range retractions (Dirzo et al. 2014). Declines are more severe in heavily disturbed regions, such as the tropics (Dirzo et al. 2014). In the northeastern United States, Wagner (2012) noted declines for many nocturnal moths, the preferred prey items for Eastern Whip-poor-will (Cink 2002).

The main possible causes for reduced availability of insect prey are identified and described below. Additional causes include changes in the predator communities, light proliferation, and acid precipitation (Graveland 1998; Benton et al. 2002; Wagner 2012; Goulson 2013). However, a direct causal effect between aerial insectivore abundance and insect populations has yet to be established, partly because long-term monitoring data on avian diets are limited (Nocera et al. 2012).

4.2.1.1. Loss of insect producing habitats

Many insects are limited to specific habitats for all or part of their life cycle and any activities that affect these habitats through habitat loss or intensification of uses (e.g., monocultures, pesticide and fertilizer-dependent crops; traditional versus conservation tillage; removal of hedgerows, wetland drainage, peat extraction, urban and coastal development; resource extraction; herbicides to control vegetation in utility rights-of-ways) would have impacts on their populations (U.S. Bureau of Land Management 1978, Foster 1991; Benton et al. 2002, Cunningham et al. 2004; Price et al. 2011, Brooks et al. 2012; Chiron et al. 2014).

Loss of insect producing habitats would affect Eastern Whip-poor-wills on the breeding grounds, along migration routes and on their wintering grounds.

4.2.1.2. Pesticides and other toxins

The use of pesticide in agriculture, forestry, and for mosquito control programs in urban areas has undoubtedly been a factor in the reduction of the abundance of flying insects throughout the Eastern Whip-poor-will’s distribution.

Although most organochlorine pesticides (chemicals in the same family as dichlorodiphenyltricholoroethane – DDT) have been banned in North America for decades, there is indication that Neotropical migrant insectivores are still being exposed to their effects elsewhere in the Americas (Sager 1997, Klemens et al. 2000). These chemicals can have long-lasting effects on insect communities and thus the birds that rely on them. Dietary records of Chimney Swifts (Chaetura pelagica), an aerial insectivore, confirm a marked decrease in beetles (Coleoptera) and an increase in true bugs (Hemiptera) that was temporally correlated with a steep rise in DDT and its metabolites. Nocera et al. (2012) argued that DDT caused declines in Coleoptera and dramatic (possibly permanent) shifts in the insect communities, resulting in a nutrient-poor diet and ultimately a declining Chimney Swift population.

Non-selective pesticides, such as the widely used neonicotinoids, have also been shown to affect aerial insectivores by reducing their prey populations and impairing reproduction (Colburn et al. 1993, Wickramasinghe et al. 2004; Mineau and Palmer 2013; Hallmann et al. 2014). Neonicotinoids are generally used in agricultural habitats, but have been detected in wetlands (Main et al. 2014) and waterways in Canada (Environment Canada 2011a, Xing et al. 2013). In 2013, the European Food Safety Authority declared that they posed an ‘unacceptable” risk to insects (Goulson 2014). Mineau and Palmer (2013) suggested that the effects of neonicotinoids on birds may not be limited to the farm scale, but likely expand to the watershed or regional scale.

Although not necessarily related to a decline in flying insect populations, the consumption of mercury-contaminated insects has been shown to decrease reproductive success, alter immune responsiveness, and cause behavioural and physiological effects in many insectivorous bird species (Scheuhammer et al. 2007, Hawley et al. 2009). Increased mercury levels may result from multiple causes (e.g., acid depositions, creation of reservoirs) and many terrestrial songbirds of northeastern North America that eat invertebrates have been found to biomagnify the substance to level that may be of conservation concern (Osborne et al. 2011; Keller et al. (2014). Although the Eastern Whip-poor-will was not part of these studies, the conclusions likely apply to the species.

4.2.1.3. Insect/breeding temporal mismatch

Birds often exhibit a strong synchronization between their reproductive timing (i.e. hatching) and peak food abundance, but climate change has caused the timing of peaks in some insects to occur sooner in the season (Both et al. 2009). Because warming may be less severe on the Eastern Whip-poor-will’s wintering grounds than on their breeding grounds, they may experience migration cues at dates that are too late for them to arrive at breeding grounds at the optimal time (Jones and Cresswell 2010). As a result, climate change is creating a temporal mismatch between reproduction and maximal prey abundance (i.e. insects) for species that are not adapting to the changing climate at the same rate as their prey (Strode 2003; Both et al. 2006; Gornish and Tylianakis, 2013). This has been shown to affect the weight of Great Tit (Parus major) chicks and the number of chicks that fledge (Visser et al. 2006). An insect/breeding temporal mismatch has also been linked to the population declines of migrant birds across Europe (Møller et al. 2008, Saino et al. 2011).

Long-distance migratory birds that breed in habitats where the peaks of food abundance are shorter (such as forests) are more vulnerable to climate change because the temporal mismatch is more likely and more severe (Both et al. 2006, Both et al. 2009). Although no species-specific data are currently available, the Eastern Whip-poor-will is a long-distance migratory aerial insectivore that breeds / forages in habitats where peaks of food abundance are shorter (usally late Spring/early Summer), so a climate-induced mismatch between breeding and prey availability is probable.

On the wintering grounds in Mexico and Central America, since the early 1900s, forest conversion into pastures for cattle ranching through slash-and-burn agriculture has driven the majority of deforestation (Leonard 1987; Masek et al. 2011; Aide et al. 2013). In that region, the countries that experienced the most forest area loss between 2001 and 2010 are Guatemala and Nicaragua, representing 3 019 km2 and 7 961 km2 respectively (Aide et al. 2013) but most countries exhibit substantial declines in forest cover (Hansen et al. 2013). Although Eastern Whip-poor-wills may benefit from habitat created by some types of conversion for cattle pastures, intensive conversion that eliminates corridors and leaves little to no forested habitat adjacent to open habitats used for foraging decreases habitat suitability.

The impact of this threat on the decline of the Eastern Whip-poor-will has not been quantified, but it is viewed as a concern because of the species’ concentration in a limited amount of winter habitat.

In Canada, the increased demand for agricultural land was responsible for approximately 43% of the deforestation in 2010 (~20 000 ha), mainly in Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba where the boreal forest borders the prairies . In the eastern United States, rates of conversion of forest to agricultural land have slowed considerably in recent years (Ramankutty et al. 2010; Masek et al. 2011) and many areas are returning to a forested state.

Efforts to increase the productivity of agricultural lands have led to the loss of large natural habitats, loss of habitat diversity in agricultural landscapes (e.g. conversion to row crops, elimination of hedges and other natural features), and an increase in pollution from nutrients and pesticides used on crops, all of which affect biodiversity (Robinson and Sutherland 2002). Insectivorous bird abundance and richness are higher in agricultural landscapes that provide a heterogenous array of habitats (Parish et al. 1995; Jones et al. 2005), which are also home to more insect prey (Lewis and Stephenson 1966; Lewis and Dibley 1970; Verboom and Spoelstra 1999). Furthermore, landscapes that are highly simplified (e.g., dominated by hard edges between intensive crops and adjacent forests) may not provide enough suitable habitat for the Eastern Whip-poor-will. In Quebec, it has been noticed that the species avoids large areas of intensive agriculture (Cyr and Larivée 1995; Bélanger et al. 1999). In southern Ontario, the conversion of open grasslands and thickets to intensive agriculture has also been identifed as a threat to the species (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources 2009).

Urban development is an increasing threat that leads to permanent habitat losses both in suburban and rural areas. It is considered the leading cause of deforestation in the United States, as well as a major contributing factor in Canada (17%)(Robinson et al. 2005; Radeloff et al. 2005; Sun et al. 2007; Masek et al. 2011; Jobin et al. 2014). In Pennsylvania (USA), urbanization, through the increase of predation and the decrease in availability of nesting and foraging habitat, is presumed responsible for the decline of the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Santner 1992).

Habitat loss and fragmentation by urbanization may also increase water, air, noise and light pollution. Ecological light pollution has been proven to disrupt predator-prey dynamics, competition dynamics, nest site choice, orientation and communication for a variety of animals (Longcore and Rich 2004). It could also have positive components (e.g., better foraging efficiency).

Exploration to find new energy sources (e.g., oil, gas, coal and hydroelectricity) and minerals (including aggregates), exploitation of these sources (e.g., mine residues, flooding of areas to create reservoirs) and their transportation (e.g., pipelines, transmission lines, roads) have generated habitat loss, degradation and fragmentation in some areas of the Eastern Whip-poor-will’s distribution (Masek et al. 2011). Activities associated with these industries can also lead to the unintentional destruction of nest, eggs, nestling, and/or adults (Van Wilgenburg et al. 2013).

Rand (2014) found that Eastern Whip-poor-wills did not show elevated stress levels (measured by corticosterone) from exposure to mining exploration activities. Otherwise, quantitative effects of the more active exploitation phase of mining on Eastern Whip-poor-will populations have not been measured, but are presumed to be important given that habitat alterations by these activities are often permanent.

The maintenance of some infrastructures used to transport energy can generate habitat that will eventually be suitable for foraging.

Forests overgrazed by cattle are usually avoided for nesting purposes by the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Tyler 1940; Godfrey 1986), although they may be used for foraging if suitable nesting habitat is nearby (Cink 2002). Deer grazing can also be problematic in some areas as their populations have been increasing for decades (Russell et al. 2001). In Canada, cattle overgrazing has been identified as a factor contributing to the disappearance of the species, particularly in south-eastern Saskatchewan’s aspen forests (Smith 1996; Jorgenson and Foster 2007).

Whatever the source, overgrazing of forest understory decreases vegetation cover and modifies plant community composition and dynamics (Patric and Helvey 1986; Côté et al. 2004; Rooney 2009; Goetsch et al. 2011), which in turn negatively affects wildlife by altering nest cover and food sources (Gallizioli 1979; DeGraaf et al. 1991; Pollard and Cooke 1994; Gill 2000; Allombert et al. 2005). At present, it is unknown how this threat is affecting the Eastern Whip-poor-will’s population, but it would be prominent in northeastern United States and south-eastern Canada where White-tailed Deer (Odocoileus virginianus) are particularly abundant (Russell et al. 2001).

In forested landscapes, the Eastern Whip-poor-will often takes advantage of the open areas created by low-intensity agriculture or forest management for foraging, while relying on adjacent forests for nesting (COSEWIC 2009). Agricultural land abandonment creates early- and mid-successional forests that can, at first, provide suitable habitat for the species, but succession eventually leads to older forest stages, which are not preferred habitats (Bushman and Therres 1988).

Although cropland areas have increased over the past 50 years in most of the Eastern Whip-poor-will’s range in southern Canada, succession of abandoned farmland has been the trend in marginal areas (Cadman et al. 2007; Latendresse et al. 2008), such as eastern Ontario (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources 2009) and the eastern United States where this succession has been implicated in the Eastern Whip-poor-wills’ decline (Medler 2008). In those areas, forest succession may have caused some degree of nesting/foraging habitat loss for the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Mills 2007; Smith 1996).

The potential effects of climate change on the Eastern Whip-poor-will can be difficult to predict because different bird species respond differently to spatial and temporal variations in their environment (Taper et al. 1995). One effect, the increase in the number of severe weather events (cold snaps, hurricanes, wind storms), can have an impacts on the breeding grounds, along the migration routes and on the wintering grounds. Cold, wet weather during the breeding season is well known for affecting aerial insectivores (e.g., Brown and Brown 2000). Such fluctuations and weather extremes are expected to occur more frequently due to climate change (Huber and Gulledge 2011).

Fire activity is also strongly influenced by weather (Flannigan et al. 2009) and the extent, intensity, and frequency of forest fires are projected to increase due to warmer springs and summers and decreases in water availability in some areas (Flannigan et al. 2009, North American Bird Conservation Initiative US Committee 2010, de Groot et al. 2013, Girardin et al. 2013). This would have a positive effect on Eastern Whip-poor-will habitat availability.

During the Fall migration, tropical storms and hurricanes can kill individuals in large numbers; a single hurricane (Hurricane Wilma in 2005) led to a decline of 50% in the population of the Chimney Swift in Québec (Dionne et al. 2008). On the tropical and subtropical wintering areas, Anodon et al. (2014) suggest that climate change will result in the expansion of savannahs at the expense of forests, which could eventually affect Eastern Whip-poor-wills.

The Eastern Whip-poor-will may be associated with habitat created by fires (Cink 2002). Fire in a natural system may provide a shifting mosaic of nesting and foraging habitat. Modern fire suppression may keep forest stands into a more mature stage, less suitable for the species. Fire suppression has been identified as one of the causes of the bird’s decline in Ontario (Mills 2007; Tozer et al. 2014). The extent of this threat is not quantified for Eastern Whip-poor-will populations but would mostly affect the northern (non-agricultural) portion of the range.

Between 2000 and 2012, approximately 11 million ha of forest were harvested throughout Canada (NFD 2014). Forest harvesting rates in most of Canada have been relatively stable throughout the past 20 years but are expected to decline in the coming years (Masek et al. 2011).

Forest harvesting can have short term negative effects on nesting birds by disrupting breeding activities (Hobson et al. 2013). The nests and/or eggs can be inadvertently harmed or disturbed as a result of clearing trees and other vegetation (e.g. pre-commercial thinning) (Environment Canada 2014b). Nesting failure could also result from disruptive activities experienced by a nesting bird (Environment Canada 2014b). Hobson et al. (2013) estimated that between 616,000 and 2.09 million nests (of many species) are lost annually as a result of industrial forest harvesting.

However, forest management can also improve habitat through practices such as clearcut interspersion with mature forests (Wilson and Watts 2008, Tozer et al. 2014), variable density thinning, early thinning and other aspects of partial cutting (Bushman and Therres 1988).

Much of the northern distribution of the Eastern Whip-poor-will in Canada is under forest management. Forest harvesting is also a prevalent activity along the migratory routes and on the wintering grounds.

The population and distribution objectives for the Eastern Whip-poor-will in Canada are:

- In the short term: Slow the decline such that the population does not decrease by more than 10% (i.e. 12 000 individuals) over the 2015-2025 period, and maintain the area of occupancy at 3,000 km2 or above.

- In the long term: Ensure a positive 10-year population trend starting in 2025, while favouring an increase in the area of occupancy, including the gradual recolonization of areas in the southern portion of the breeding range.

These objectives address the species’ long-term decline, which was the reason for its designation as Threatened (COSEWIC 2009). The 10-year time frame for the short term objectives corresponds to the period between successive COSEWIC assessments of a species status and is considered reasonable given the challenge halting the Eastern Whip-poor-will’s decline represents. The area of occupancy provided corresponds to the COSEWIC (2009) estimate (33 000 Eastern Whip-poor-will pairs occupying 1,650 km2) but with the updated Canadian population (120 000 individuals or 60 000 pairs) provided by the Partners in Flight Science Committee (2013), for a total of 3,000 km2. As for the long term objectives, due to the substantial loss of suitable habitat in the southern portion of the species’ range (agricultural and urban landscapes), it may be unrealistic to bring Eastern Whip-poor-will populations back to their historical levels. Nevertheless, ensuring that suitable habitat is available throughout the species’ range in Canada, including through restoration of habitats in highly transformed landscapes, is necessary for the management and recovery of the Eastern Whip-poor-will.

These objectives may be reviewed during the development of the report required five years after this strategy is posted to assess the implementation of the strategy and the progress towards meeting its objectives (s. 46 SARA).

Numerous activities have been initiated since the latest COSEWIC assessment (2009). The following list is not exhaustive, but is meant to illustrate the main areas where work is already underway, to give context to the broad strategies outlined in section 6.2.

- Multiple projects targeting the Eastern Whip-poor-will on federal, provincial and private lands with funding from the Habitat Stewardship Program, the Interdepartmental Recovery Fund and the Aboriginal Fund for Species at Risk.

- Surveys on Department of National Defence establishments.

- Research underway on the broad-scale predictors of aerial insectivorous bird declines across North America (Dr. Christy Morrissey’s Ecotoxicology Lab at the University of Saskatchewan http://homepage.usask.ca/~cam202/page11.html).

- General Habitat Description completed under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 http://www.ontario.ca/environment-and-energy/eastern-whip-poor-will

- Roadside surveys conducted by Bird Studies Canada (2010-ongoing) and provincial partners such as Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry in many districts and Ontario Parks (e.g., Algonquin Park).

- Study on habitat use, types of forest management and landscape characteristics is underway (Philina English – Simon Fraser University; John Vandenbroeck - OMNRF Fort Frances District; English and Conboy 2013).

- Surveys on Department of National Defence establishments.

- Roadside surveys coordinated by Regroupement QuebecOiseaux on 25 permanent BBS-style routes in agricultural landscapes (2012-ongoing).

- Surveys along potential routes in the Outaouais region by Dendroica Environnement et Faune (2013 – ongoing).

- Project funded by the Interdepartmental Recovery Fund and the Department of National Defence to conduct surveys of the populations, describe the location of suitable habitat and propose potential mitigation measures for military activities at five Department of National Defence establishments (2012-ongoing).

- Habitat Stewardship Program projects on forest birds at risk to assist in the development of Maritimes-specific beneficial management practices conducted by Bird Studies Canada (ongoing)

| Threat or Limitation | Broad Strategy for Recovery | Prioritya | General Description of Research and Management Approaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| a "Priority" reflects the degree to which the approach contributes directly to the recovery of the species or is an essential precursor to an approach that contributes to the recovery of the species. b Environment Canada’s website on Bird Conservation Regions and Conservation Strategies c Environment Canada’s website on the incidental take of migratory birds. |

|||

| All threats | Stewardship and management of the species and its suitable habitat | High |

|

| Knowledge gaps | Monitoring and Research | High |

|

| Knowledge gaps | Monitoring and Research | Low |

|

| All threats | Education and Partnerships | Medium |

|

| All threats | Law and Policy | High |

|

| All threats | Law and Policy | Medium |

|

Preserving and enhancing Eastern Whip-poor-will nesting and foraging habitats will require promotion of approaches on a broad scale. These habitats must be managed and protected to ensure species survival, particularly in areas where large portions of habitat have been lost or degraded or are facing increased development pressures.

The key actions that can be promoted include beneficial management practices in forest management and agricultural activities as well as habitat restoration to increase habitat supply, where needed. Beneficial management practices for the Eastern Whip-poor-will must be integrated with those for other bird species to maintain heterogeneous landscapes that are a dynamic mosaic of habitat conditions which will benefit several species. Whenever possible, a multi-species or ecosystem approach to recovery should be considered. Beneficial management practices for governments, industry, and even individuals can play an important role for the ongoing efforts to promote recovery of the Eastern Whip-poor-will. However, it must be kept in mind that such approches will fail to recover the species unless migration and wintering habitats are also maintained and threats are addressed.

A comprehensive approach to research and monitoring (that includes all stages of the annual life cycle and the entire range of occupancy) will be required to more completely understand the status of the species, as well as its threats and limiting factors on the breeding, migration and wintering grounds. Currently, adequate monitoring of the species is limited and concentrated close to urban centres. Targeted research and monitoring efforts are required throughout the Eastern Whip-poor-will’s range in order to determine key demographic parameters (e.g., survival, dispersal, reproductive success in different habitat types) and identify migratory routes, stopover sites, and migratory connectivity that provide insight into the species needs at multiple scales. Trends in habitats and prey populations must be better understood (and monitored) to know whether maintaining, enhancing, and/or restoring insect producing habitats would significantly benefit Eastern Whip-poor-will populations.

Because the broad-scale monitoring of the Eastern Whip-poor-will is complicated by the large range of the species and its nocturnal habits, using alternative survey approaches (e.g., electronic acoustic monitoring) should be explored and citizen-based databases such as eBird should be considered. There are fewer monitoring programs established on the wintering grounds, but these are essential. They need to be developed and implemented to provide better information on habitat use, local habitat and population trends. Associated with these efforts, there is a need to build and validate corresponding habitat models at national and regional scales to better understand where on the landscape the species would be expected to breed, and assist with efforts to protect important and critical habitat.

Collaboration with national and international jurisdictions (all levels of government), aboriginal peoples, industries, non-governmental organizations and landowners to preserve, restore, and enhance breeding, migration and wintering habitats is an important component of this recovery strategy. This could take the form of a working group such as those that have been put together for the Golden-winged Warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera) and the Canada Warbler (Wilsonia canadensis) or could target a larger group of species such as nocturnal aerial insectivores. Indeed, to be effective, research, conservation, and stewardship approaches must be applied throughout the species’ range.

Promoting volunteer participation and collaborations in monitoring programs will also be a key element. Volunteers whose efforts should be promoted include local bird clubs who have knowledge of areas with high breeding densities and citizen scientists participating in bird atlases, breeding bird survey programs and citizen-based data collection (e.g., eBird).

Throughout the species range, promoting the compliance with existing regulations and policies should be a priority. Currently, there are multiple legal means available to protect Eastern Whip-poor-wills and their habitats in Canada (e.g., Endangered Species Acts). It is important that these tools are fully realized and utilized for the protection of the species.

General prohibitions under the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 and its regulations also protect Eastern Whip-poor-will adults, young, nests and eggs anywhere they are found in Canada, regardless of land ownership. During the breeding period, potential destructive or disruptive activities should be avoided at locations where the species is likely to be encountered (Environment Canada 2014a).

SARA defines critical habitat as “…the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species…”. Section 41(1)(c) of SARA requires that recovery strategies include an identification of the species’ critical habitat, to the extent possible, as well as examples of activities that are likely to result in its destruction. This recovery strategy partially identifies critical habitat, based on the best available information for the Eastern Whip-poor-will as of September 2014. The Schedule of Studies (section 7.2) outlines the activities required for completing the identification of the critical habitat necessary to meet the population and distribution objectives. As additional information becomes available, more precise boundaries may be mapped and further critical habitat may be identified.

The identification of critical habitat for the Eastern Whip-poor-will is based on two criteria: habitat occupancy and habitat suitability.

This criterion is intended to identify, with a reasonable degree of certainty, the areas of nesting and foraging habitats used by the species. In an analysis of a large number of studies of North American and European birds, Bock and Jones (2004) found that habitat occupancy was frequently an appropriate indicator of habitat suitability.

Habitat occupancy is based on documented nest locations, standardized survey data, as well as incidental observations. Confirmed breeding recordsFootnote4 Footnote5, constitute the highest indication of habitat occupancy. However, as the Eastern Whip-poor-will is a nocturnal species, breeding confirmation is rare. Accordingly, a more precautionary approach to establishing occupancy is warranted and considers combinations of records with lower nesting probabilities (probable or possible breeding birds).

Because Breeding Bird Atlases are the main sources of Eastern Whip-poor-will data across Canada, the earliest fieldwork year among the second editions of atlas projects (2001 in Ontario) was determined as the starting year to establish occupancy using all available data sources (species-specific surveys, BBS, Conservation Data Centres and check-lists such as eBird that compile records that do not originate from standardized programs). All confirmed breeding records were selected. For other types of records, a multiple occupancy criterion, useful to increase confidence that individuals use the habitats in which they were detected, was established at a scale relevant to Eastern Whip-poor-will populations. This was determined to be the 10 x 10 km atlas square because this is consistent with available data (e.g., breeding bird atlas projects, land cover datasets and standardized national grid systems) but also because it is a representative scale to capture the species’ needs. It is at this scale that disturbance regimes (both natural and anthropogenic) operate to provide the supply of nesting and foraging habitats necessary to support self-sustaining populations. Consequently, the habitat occupancy criteria for the Eastern Whip-poor-will are met within an atlas square when records from the 2001 breeding season (21st May - 15th August) or thereafter consist of at least :

- One record of confirmed breeding;

OR - Two records during a single year or from distinct years, where at minimum one record consists of probable breeding;

OR - Two possible breeding records during a single year in combination with at least one possible breeding record from any other year;

OR - Five possible breeding records during a single year or from different years.

The data used to identify the critical habitat in the present recovery strategy are from 2001 to 2014, inclusively depending on the data available within each region. Since many habitat types occupied by the Eastern Whip-poor-will are dynamic (e.g., a clear cut forest can become too dense for nesting or foraging within 10-15 years under optimal conditions), records older than 2001 will need to be validated to determine if suitable nesting and foraging habitats are still available and if the species still occupies the area.

This criterion refers to the biophysical attributes of habitats in which individuals may carry out breeding (e.g., courtship, territory defense, nesting) and foraging activities in Canada (Table 5). Breeding and foraging habitats form a mosaic. Depending on the habitat attributes available locally, nesting and foraging habitats overlap to various degrees (e.g., individuals forage in wetlands with sufficient perches but do not nest in them, whereas individuals may nest and forage in young regenerating forests). The criteria to determine the extent of suitable habitat vary accordingly. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (2002) developed a habitat model for the Eastern Whip-poor-will in the northeastern United States. It suggests that when forests with a dense tree cover are used for nesting purposes, only the first 30 m from the edge needs to be included as the species is not associated to the forest interior. On the other side of the spectrum, when habitats can only be used for foraging purposes because the vegetation structure or other characteristics (e.g., drainage) are unsuitable for nesting, data from Rand’s (2014) study suggest that it is sufficient to incorporate the habitat up to 1,250 m of the edge with nesting habitats, i.e. the maximum movement observed.

| Components of habitat suitability | Biophysical Attributes |

|---|---|

| a Sparse : <25% ; Moderate : 25-75% ; Dense : >75% b Minimum territory size for the Eastern Whip-poor-will (Cink 2002). |

|

| Regional context | Forests (e.g., deciduous, mixedwood, coniferous, treed wetlands) and open habitats (e.g., shrublands, fallow fields, regeneration following fires or clear-cuts, rock and sand outcrops; shrubby wetlands) form a mosaic |

| Habitats suitable for both nesting and foraging | – Forests with sparse to moderate a a tree cover or open habitats

|

| Habitats suitable for nesting [must be adjacent to foraging habitats] |

– Forests with a dense tree cover

|

| Habitats suitable for foraging only [must be adjacent to nesting habitats] |

– Forests with sparse tree cover or open habitats

OR – Agricultural land with scattered shrubs or trees (e.g., hedgerows) that can be used as perches

|

Critical habitat for the Eastern Whip-poor-will is partially identified in this recovery strategy. It corresponds to the areas of suitable nesting and/or foraging habitats within all 10 x 10 km atlas squares meeting the occupancy criteria. Each of these 10 x 10 km atlas squares is a critical habitat unit. Due to the dynamic nature of some of the habitat components required by the species, no detailed critical habitat mapping is provided. It is also unknown, at this time, to what degree the objective of maintaining the area of occupancy above 3000 km2 is met. The identification of critical habitat is considered partial due to limited survey data availability in certain areas of the Eastern Whip-poor-will’s distribution and knowledge gaps related to the importance of landscape-level habitat attributes.

Appendix A (Tables A-1 to A-4 and Figures A-1 to A-4) presents the units within which critical habitat is found for the Eastern Whip-poor-will in Canada. Because they both originate from breeding bird atlas squares, critical habitat units for this species are the same as the 10 x 10 km standardized UTM squares used by Environment Canada to indicate the general geographic location of critical habitat (red hatched outlines in figures in Appendix A). Overall, 212 critical habitat units are identified for the Eastern Whip-poor-will, including 32 in Manitoba, 110 in Ontario, 65 in Quebec, and five in the Maritimes (all in New Brunswick). More detailed information on the location of critical habitat to support protection of the species and its habitat may be requested, on a need-to-know basis, by contacting Environment Canada’s Recovery Planning section at : RecoveryPlanning_Pl@ec.gc.ca.

Any anthropogenic structure (e.g., houses, paved surfaces) and any other areas that do not have the biophysical attributes of suitable habitat are not identified as critical habitat.

| Description of Activity | Rationale | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Determine habitat characteristics (e.g., spatial scale, configuration) that influence the selection and quality of nesting and foraging habitat for the Eastern Whip-poor-will in Canada | Clarify critical habitat identification criteria and add a landscape component if needed | 2015-2020 |

Conduct standardized nocturnal breeding surveys where:

|

Additional critical habitat identified to meet the short term population and distribution objectives | 2015-2025 |

| Identify areas in the southern portion of the breeding distribution in Canada where the species could recolonize habitats following their restoration or management | Additional critical habitat identified to meet the long term population and distribution objectives | 2015-2035 |

Understanding what constitutes destruction of critical habitat is necessary for the protection and management of critical habitat. Destruction is determined on a case by case basis. Destruction would result if part of the critical habitat were degraded, either permanently or temporarily, such that it would not serve its function when needed by the species. Destruction may result from a single or multiple activities at one point in time or from the cumulative effects of one or more activities over time (Government of Canada 2009). Activities described in Table 7 are examples of those likely to cause destruction of critical habitat for the species; however, destructive activities are not necessarily limited to those listed. It should be noted that some activities that would result in the destruction of critical habitat if conducted during the breeding season could also generate the open habitats necessary for foraging as well as nesting habitats in the following years (dynamic habitat mosaic).

| Description of Activity | Description of Effect | Details of Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Eastern Whip-poor-will general nesting period in Canada extends from mid-May to mid-August (Rousseu and Drolet, unpublished data). | ||

| Intensification of agricultural practices (e.g., conversion of extensive cultures to more intensive crops) | Loss or degradation of suitable foraging habitats; Removal of conditions that allow for sufficient prey populations; Fragmentation of habitat; Reduced insect prey populations through the use of pesticides or herbicides on the crops and adjacent habitats | Applicable at all times in critical habitat units (10 x 10 km squares) where the forest cover is already low (e.g., <25%) and if the effect is permanent; Applicable at all times in critical habitat units if activity would result in forest cover falling below 25% and if the effect is permanent; Applicable at all times if biophysical attributes would become unavailable or available in insufficient amounts at the time they are needed by the species. |

| Conversion of forests to agricultural lands | Loss or degradation of suitable habitats for nesting and/or foraging; Removal of conditions that allow for sufficient prey populations; Fragmentation of habitat | Applicable at all times in critical habitat units (10 x 10 km squares) where the forest cover is already low (e.g., <25%) and if the effect is permanent; Applicable at all times in critical habitat units if activity would result in forest cover falling below 25% and if the effect is permanent; Applicable at all times if biophysical attributes would become unavailable or available in insufficient amounts at the time they are needed by the species. |

| Energy development and mineral extraction (e.g., pipelines, energy corridors, resource extraction, dams) | Loss or degradation of suitable habitats for nesting and/or foraging; Removal of conditions that allow for sufficient prey populations; Fragmentation of habitat | Applicable at all times in critical habitat units (10 x 10 km squares) where the forest cover is already low (e.g., <25%) and if the effect is permanent; Applicable at all times in critical habitat units if activity would result in forest cover falling below 25% and if the effect is permanent; Applicable at all times if biophysical attributes would become unavailable or available in insufficient amounts at the time they are needed by the species. |

| Construction of housing units and other urban infrastructures (e.g., commercial and industrial buildings, playgrounds, roads) | Loss or degradation of suitable habitats for nesting and/or foraging; Removal of conditions that allow for sufficient prey populations; Fragmentation of habitat | Applicable at all times in critical habitat units (10 x 10 km squares) where the forest cover is already low (e.g., <25%) and if the effect is permanent; Applicable at all times in critical habitat units if activity would result in forest cover falling below 25% and if the effect is permanent; Applicable at all times if biophysical attributes would become unavailable or available in insufficient amounts at the time they are needed by the species. |

| Forest management (e.g., clearing of shrubs to install tubes in a sugarbush; maintenance in plantations) | Degradation of suitable nesting habitats in dense forests through impacts on the shrub and herbaceous layers required for the nest site and for roosting | Applicable at all times in critical habitat units (10 x 10 km squares) where the forest cover is already low (e.g., <25%) and if the effect is permanent; Applicable at all times in critical habitat units if activity would result in forest cover falling below 25% and if the effect is permanent; Applicable at all times if biophysical attributes would become unavailable or available in insufficient amounts at the time they are needed by the species. |

| Maintenance of linear infrastructures (e.g., utility rights-of-way, energy corridors) or other types of non-linear infrastructures (e.g., military ranges and fields used for military training) | Degradation of suitable nesting habitats through the reduction/elimination of the shrub and herbaceous layers required for nest site placement and loss of perches needed for roosting and foraging; Reduced insect prey populations through the use of herbicides (less insect producing habitats) | These activities, if conducted outside of the breeding seasona, may not be considered as habitat destruction. When possible, these activities could be conducted in successive steps to maintain partial shrub cover. |

The 25% forest cover (i.e. 2,500 ha) figure within each 10 x 10 km atlas square within which Eastern Whip-poor-will records occur was selected as a value under which activities, if they were to occur, are more likely to result in the abandonment of the remaining suitable habitats. The following considerations were taken into account :

- The Eastern Whip-poor-will is generally considered a bird of forested landscapes;

- Each individual may require nesting and foraging resources within home ranges as large as 500 ha (Rand 2014). Many of the atlas squares meeting the occupancy criteria had 3 or more individuals;

- Individuals often occupy transitional habitats (e.g., a partial cut forest can become too dense for nesting or foraging within 10-15 years under optimal conditions) making it necessary to maintain alternate nesting and foraging sites over areas larger than those occupied in any given year. This consideration is particularly important in atlas squares where forest cover is already under 25% and alternate breeding habitats may no longer be available;

- Regions with higher forest cover are more likely to sustain Eastern Whip-poor-will populations over the long term (more suitable habitats, reduced impact of some threats);

- An analysis shows that 10 x 10 km atlas squares meeting the occupancy criteria described in section 7.1.1 have a mean forest cover of 56% in Ontario (range = 41-98%); 42% in Quebec (range = 8-78%) and 74% in the Maritimes (range = 62-91%). This implies that there is a lot of flexibility to maintain habitat supply above 25% within most 10 x 10 km squares within which critical habitat is found.

The 25% forest cover figure should be viewed as a general indication of the level of additional activities that could take place within each 10 x 10 km square rather than a true threshold. Other considerations, including the configuration of remaining forest habitats and the level of fragmentation are also key elements. Some site-level biophysical attributes (e.g., well-drained soils such as sand deposits) may also be available in limited amounts.

The performance indicators presented below provide a way to define and measure progress toward achieving the population and distribution objectives.

- In the short term (2015-2025), declining population trends have been halted or reversed to a point where the Canadian population of the Eastern Whip-poor-will have declined no more than 10% and the areas of occupied habitats are maintained at 3000 km2 or more.

- In the long term (after 2025), a positive 10-year trend, measured by BBS and other available data (e.g., targeted surveys), is achieved (i.e., the population is increasing) and the species has started gradually recolonizing former areas in the southern portion of the Canadian range.

One or more action plans for Eastern Whip-poor-will will be developed and posted on the Species at risk public registry before the end of 2020.

- Aide, T. M., Clark, M. L., Grau, H. R., López-Carr, D., Levy, M. A., Redo, D., Bonilla-Moheno, M., Riner, G., Andrade-Núñez, M. J. and Muñiz, M. 2013. Deforestation and reforestation of latin America and the Caribbean (2001–2010). Biotropica 45: 262–271.

- Allombert, S., S. Stockton, and J.-L. Martin. 2005. A natural experiment on the impact of overabundant deer on forest invertebrates. Conservation Biology 19(6):1917-1929.

- Anodon, J.D., O. E. Sala and F.T. Maestre. 2014. Climate change will increase savannas at the expense of forests and treeless vegetation in tropical and subtropical Americas. Journal of Ecology (102) : 1363-1373.

- Atlas des oiseaux nicheurs du Québec. 2014. Données obtenues de la part des bureaux de l'Atlas des oiseaux nicheurs du Québec. Regroupement QuébecOiseaux, Service canadien de la faune d'Environnement Canada et Études d'Oiseaux Canada. Québec, Québec, Canada.

- Bélanger, L., M. Grenier and S. Deslandes, 1999. Bilan des habitats et de l'occupation du sol dans la vallée du Saint-Laurent. Environnement Canada, Service canadien de la faune, Région du Québec.

- Benton, T. G., D. M. Bryant, L. Cole and H. Q. P. Crick. 2002. Linking agricultural practice to insect and bird populations: a historical study over three decades. Journal of Applied Ecology 39: 673-687.

- Blancher, P., M. D. Cadman, B. A. Pond, A. R. Couturier, E. H. Dunn, C. M. Francis and R. S. Rempel. 2007. Changes in bird distributions between atlases. In M. D. Cadman, D. A. Sutherland, G. G. Beck, D. Lepage and A. R. Couturier (eds.). Atlas of the breeding birds of Ontario, 2001-2005. Pp. 32-48. Bird Studies Canada, Environment Canada, Ontario Field Ornithologists, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, and Ontario Nature, Toronto (Ontario).

- Blancher, P.J., R.D. Phoenix, D.S. Badzinski, M.D. Cadman, T.L. Crewe, C.M. Downes, D. Fillman, C.M. Francis, J. Hughes, D.J.T. Hussell, D. Lepage, J.D. McCracken, D.K. McNicol, B.A. Pond, R.K. Ross, R. Russell, L.A. Venier and R.C. Weeber. 2009. Population trend status of Ontario’s forest birds. The Forestry Chronicle 85(2):184-201.

- Bock, C.E. and Z.F. Jones. 2004. Avian habitat evaluation: should counting birds count? Frontiers in Ecology and Environment 2: 403–410.

- Boettner, G. H., J.S. Elkinton and C. J. Boettner. 2000. Effects of a biological control introduction on three nontarget native species of nonnative Saturniid moths. Conservation Biology 14(6): 1798-1806.

- Both, C., C. A. Van Turnhout, R. G. Bijlsma, H. Siepel, A. J. Van Strien and R. P. Foppen. 2009. Avian population consequences of climate change are most severe for long-distance migrants in seasonal habitats. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277: 1259-1266.

- Both, C., S. Bouwhuis, C. Lessells and M.E. Visser. 2006. Climate change and population declines in a long-distance migratory bird. Nature 441(7089): 81-83.

- Broeckart, M. and S. Bédard. 2012. Rapport sur la validation du modèle de l’habitat des engoulevents au Québec, la précision de l’habitat convenable pour l’Engoulevent bois-pourri et la détermination de routes d’inventaires permanentes. Regroupement QuébecOiseaux. 9 p.

- Broeckaert, M. 2012. Réalisation cartographique de la potentialité de l’habitat de l’Engoulevent bois-pourri au Québec. Regroupement QuébecOiseaux. 115 pp.

- Brooks, D. R., J. E. Bater, S. J. Clark, D. T. Monteith, C. Andrews, S. J. Corbett, D. A. Beaumont and J. W. Chapman. 2012. Large carabid beetle declines in a United Kingdom monitoring network increases evidence for a widespread loss in insect biodiversity. Journal of Applied Ecology 49(5): 1009-1019.

- Brown, C. R. and M. B. Brown. 2000. Weather-mediated natural selection on arrival time in Cliff Swallows (Petrochelidon pyrrhonota). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 47(5): 339-345.

- Bushman, E.S. and G.D. Therres. 1988. Habitat management guidelines for forest interior breeding birds of coastal Maryland. Maryland Deptartment of Natural Resources. Wildlife Technical Publication 88-1. 50 p.

- Cadman, M. D., D.A. Sutherland, G. G. Beck, D. LePage and A.R. Couturier, eds. 2007. Atlas of the breeding birds of Ontario, 2001-2005. Bird Studies Canada, Environment Canada, Ontario Field Ornithologists, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, and Ontario Nature, Toronto, xxii + 706 p.

- Cadman, M. D., Sutherland, D. A. and F. M. Helleiner (eds). 1987. Atlas of the Breeding Birds of Ontario. University of Waterloo Press. Waterloo, Ontario. 617 p.

- Chesser, R. T., Banks, R.C., Barker, F. K., Cicero, C., Dunn, J. L., Kratter, A. W., Lovette, I. J., Rasmussen, P. C., Remsen, J. V., Jr, Rising, J. D., Stotz, D. F. and K. Winker. 2010. Fifty-first supplement to the American ornithologists’ Union Check-list of North American Birds. The Auk. 127(3):726-744.

- Chesser, R. T., R.C. Banks, F. K. Barker, C. Cicero, J. L. Dunn, A. W. Kratter, I. J. Lovette, P. C. Rasmussen, J. V. Remsen, J. D. Jr Rising, D. F. Stotz, and K. Winker. 2012. Fifty-third supplement to the American ornithologists’ Union Check-list of North American Birds. The Auk. 129(3):573-588.

- Chiron, F., R. Chargé, R. Julliard, F. Jiguet and A. Muratet. 2014. Pesticide doses, landscape structure and their relative effects on farmland birds. Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 185:153–160.

- Cink, C. L. 2002. Eastern Whip-poor-will (Antrostomus vociferus), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America. (Accessed September, 2014).

- Colburn, T., F.S. Vom Saal and A.M. Soto. 1993. Developmental effects of endocrine-disrupting chemicals in wildlife and humans. Environmental Health Perspectives 101: 378-384.

- Cooper, R.J. 1981. Relative abundance of Georgia Caprimulgids based on call-counts. Wilson Bulletin 93: 363-371.

- Cornell Lab of Ornithology. 2007. Eastern Whip-poor-will. (Accessed April, 2013).

- COSEWIC. 2009. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Whip-poor-will Caprimulgus vociferus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 28 pp.

- Côté, S. D., T. P. Rooney, J.-P. Tremblay, C. Dussault and D. Waller. 2004. Ecological impacts of deer overabundance. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics 3: 113-147.

- Cunningham, H.M, K. Chaney, R.B. Bradbury and A. Wilcox. 2004. Non-inversion tillage and farmland birds: a review with special reference to the UK and Europe. Ibis 146(2): 192–202.

- Cyr, A. and J. Larivée. 1995. Atlas saisonnier des oiseaux du Québec. Société du Loisir Ornithologique. 714 p.

- DeGraaf, R. M., W. M. Healy and R. T. Brooks. 1991. Effects of thinning and deer browsing on breeding birds in New England oak woodlands. Forest Ecology and Management 41:179-191.

- de Groot, W. J., M. D. Flannigan and A. S. Cantin. 2013. Climate change impacts on future boreal fire regimes. Forest Ecology and Management 294: 35-44.

- Dendroica Environnement et Faune. 2013. Inventaire de huit espèces d’oiseaux en péril en Outaouais en vue de désigner leur habitat essentiel : 1ere année du suivi. Présenté au Service canadien de la faune Environnement Canada. 23 p.

- Dionne, M., C. Maurice, J. Gauthier and F. Shaffer. 2008. Impact of hurricane Wilma on migrating birds: The case of the Chimney Swift. The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 120(4): 784-792.

- Dirzo, R., H. S. Young, M. Galetti, G. Ceballos, N. J. Isaac and B. Collen. 2014. Defaunation in the Anthropocene. Science 345(6195): 401-406.

- Eastman, J. 1991. Whip-poor-will, pp. 252-253 in Brewer, R., G.A. McPeek and R.J. Adams Jr., eds. The Atlas of Breeding Birds of Michigan. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, East Lansing, Michigan. 594pp.

- eBird Canada. 2014. Bird Observations on eBird website Version 1.0. Audubon and Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (Accessed April, 2014).

- English, P. and M.A. Conboy. 2013. Developping stewardship prescriptions for Whip-poor-wills (Antrostomus vociferous) in eastern Ontario: SARSF Final Report. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources. Peterborough, Ontario. 14 p.

- Environment Canada. 2011. Presence and levels of priority pesticides in selected Canadian aquatic ecosystems. Environment Canada, Water Science and Technology Directorate. Gatineau, Québec.

- Environment Canada. 2014a. North American Breeding Bird Survey – Canadian Results and Analysis Website version 3.00. Environment Canada, Gatineau, Quebec. (Accessed June, 2014).

- Environment Canada. 2014b. Avoidance Guidelines related to Incidental Take of Migratory Birds in Canada.

- Erskine, A.J. 1992. Atlas of Breeding Birds of the Maritime Provinces. Nimbus Publishing Ltd. The Nova Scotia Museum. 270 p.

- Flannigan, M., B. Stocks, M. Turetsky and M. Wotton. 2009. Impacts of climate change on fire activity and fire management in the circumboreal forest. Global Change Biology 15(3): 549-560.

- Foster, G. N. 1991. Conserving insects of aquatic and wetland habitats, with special reference to beetles. Pages 237-262 In The conservation of insects and their habitats. 15th Symposium of the Royal Entomological Society of London. Academic Press. London, UK.

- Gallizioli, S. 1979. Effects of livestock grazing on wildlife. Presented at the 10th Annual joint Meeting of the western Section, the Wildlife Society and the California-Nevada Chapter, American Fisheries Society. (Accessed November, 2014).

- Garlapow, R. M. 2007. Whip-poor-will prey availability and foraging habitat: implications for management in pitch pine / scrub oak barrens habitats. University of Massachussetts - Amherst. Masters Theses. Paper 27. 58 p.

- Gauthier, J. and Y. Aubry (eds). 1996. The breeding birds of Quebec: Atlas of the breeding birds of southern Quebec. Province of Quebec Society for the Protection of Birds and Canadian Wildlife Service, Montreal. xviii + 1,302 pp.

- Gill, R. 2000. The Impact of deer on woodland biodiversity. Forestry Commission Information Note 36. Forestry Commission, Edinburgh.

- Girardin, M. P., A. A. Ali, C. Carcaillet, O. Blarquez, C. Hély, A. Terrier, A. Genries and Y. Bergeron. 2013. Vegetation limits the impact of a warm climate on boreal wildfires. New Phytologist 199(4): 1001-1011.

- Godfrey, W.E. 1986. Birds of Canada. National Museum of Natural Sciences, Ottawa, 595 pp.