Gattinger's agalinis (Agalinis gattingeri) proposed recovery strategy 2017: part 2

Part 2 – Recovery Strategy for the Gattinger's Agalinis (Agalinis gattingeri) in Ontario, prepared by Judith Jones for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Gattinger's Agalinis (Agalinis gattingeri) in Ontario

Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

Recovery strategy prepared under the Endangered Species Act, 2007

Recovery strategy for the Gattinger's Agalinis (Agalinis gattingeri) in Ontario-2015

Photo: © Theodore Flamand

Photo: © Theodore Flamand

Natural. Valued. Protected.

Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry - Ontario

Document information

About the Ontario Recovery Strategy Series

This series presents the collection of recovery strategies that are prepared or adopted as advice to the Province of Ontario on the recommended approach to recover species at risk. The Province ensures the preparation of recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada.

What is recovery?

Recovery of species at risk is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

What is a recovery strategy?

Under the ESA a recovery strategy provides the best available scientific knowledge on what is required to achieve recovery of a species. A recovery strategy outlines the habitat needs and the threats to the survival and recovery of the species. It also makes recommendations on the objectives for protection and recovery, the approaches to achieve those objectives, and the area that should be considered in the development of a habitat regulation. Sections 11 to 15 of the ESA outline the required content and timelines for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for endangered and threatened species within one or two years respectively of the species being added to the Species at Risk in Ontario list. There was a transition period of five years (until June 30, 2013) to develop recovery strategies for those species listed as endangered or threatened in the schedules of the ESA. Recovery strategies are required to be prepared for extirpated species only if reintroduction is considered feasible.

What's next?

Nine months after the completion of a recovery strategy a government response statement will be published which summarizes the actions that the Government of Ontario intends to take in response to the strategy. The implementation of recovery strategies depends on the continued cooperation and actions of government agencies, individuals, communities, land users, and conservationists.

For more information

To learn more about species at risk recovery in Ontario, please visit the Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry Species at Risk.

Recommended citation

Jones, J. 2015. Recovery strategy for the Gattinger's Agalinis (Agalinis gattingeri) in Ontario. Ontario Recovery Strategy Series. Prepared for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Peterborough, Ontario. vi + 33 pp.

Cover illustration: Gattinger's Agalinis by Theodore Flamand. This photo may not be reproduced separately from this document without permission of the photographer.

Content (excluding the cover illustration) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Authors

Judith Jones, Winter Spider Eco-Consulting, Sheguiandah, Ontario

Acknowledgments

Previous versions of some material in this document were prepared by Judith Jones, Jarmo Jalava, and Holly Bickerton under the direction of the Bruce-Manitoulin Alvar Recovery Team and Parks Canada Agency.

The author gratefully acknowledges the following people and agencies for sharing information: Anthony Chegahno (Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation), Theodore Flamand (Wikwemikong Department of Lands and Natural Resources), Clint Jacobs (Walpole Island Heritage Centre), G'mewin Migwans (United Chiefs and Councils of M'nidoo M'nising), Will Kershaw (Ontario Parks), and Nikki Boucher (Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry, Sudbury District) for sharing information. Thanks to Theodore Flamand for the use of his photos.

Declaration

The recovery strategy for Gattinger's Agalinis was developed in accordance with the requirements of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA). This recovery strategy has been prepared as advice to the Government of Ontario, other responsible jurisdictions and the many different constituencies that may be involved in recovering the species.

The recovery strategy does not necessarily represent the views of all of the individuals who provided advice or contributed to its preparation, or the official positions of the organizations with which the individuals are associated.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best available knowledge and are subject to revision as new information becomes available. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy.

Responsible jurisdictions

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry

Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Ontario

Executive summary

Gattinger's Agalinis (Agalinis gattingeri) is listed as endangered in Ontario under Ontario's Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA)and as endangered in Canada on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA).

Gattinger's Agalinis is a small, wiry, annual plant, less than 15 cm tall, with very slender opposite leaves and pale pink, funnel-shaped flowers that occur singly at the end of long slender stalks. It flowers from late July through September. The species has a long-lived seed bank and seeds have been known to germinate after more than 10 years of storage. Population sizes may fluctuate, and if live plants of Gattinger's Agalinis are not observed in any given year, a site cannot be presumed to be unoccupied.

There are 26 extant occurrences of Gattinger's Agalinis in Ontario and 5 in Manitoba. In Ontario, Gattinger's Agalinis occurs in both tallgrass prairie and alvar habitats. The species is found on and around Manitoulin Island, on the Bruce Peninsula, and on Walpole Island. At least 18 occurrences are on First Nation reserves, or on other lands that are traditional territory or claimed by First Nations. Three occurrences are in protected areas and two are in a proposed addition to a provincial park. Total abundance in Ontario is around 70,000 individuals, but this fluctuates. On Walpole Island, the species is in serious decline. In the Manitoulin Region, damage has occurred at four corporately-owned sites, but the extent is unknown. Most other sites likely have stable populations.

Threats to Gattinger's Agalinis include development, changes to ecological processes, conversion of prairie to agriculture, aggregate extraction, invasion by exotic species, logging and industrial activities, off-road vehicle use, livestock grazing, trampling, with a lack of awareness about alvar sensitivity underlying many threats.

The recovery goal is to maintain self-sustaining populations of Gattinger's Agalinis in their current distribution in Ontario by maintaining and protecting habitat and reducing other threats. The recovery objectives are to:

- assess threats and undertake actions for mitigation and reduction;

- use policy tools, where appropriate, to protect Gattinger's Agalinis;

- raise awareness about Gattinger's Agalinis and its sensitive habitats; and

- fill knowledge gaps.

A number of steps and actions are suggested to fulfill these goals and objectives and to address threats.

It is recommended that the habitat to be considered for regulation be prescribed as follows.

- All areas where Gattinger's Agalinis grows or has grown unless surveys show that the species has been absent for more than 10 years.

- Any new areas where the species becomes discovered in the future.

- The area where live Gattinger's Agalinis plants grow or have previously grown and the entire ELC vegetation polygon in which the occurrence is found.

- An additional distance of 50 m around the outside of the polygon, so that in cases where individuals occur at the edge of a polygon, there will be sufficient distance from activities in adjacent areas to prevent negative effects, such as changes in drainage that affect soil moisture.

1 Background information

1.1 Species assessment and classification

- Common name (population)

- Gattinger's Agalinis

- Scientific name

- Agalinis gattingeri

- SARO list classification

- Endangered

- SARO list history

- Endangered (2008), Endangered – not regulated (2004)

- COSEWIC assessment history

- Endangered (2001, 1999, and 1988).

- SARA schedule 1

- Endangered (June 5, 2003)

- Conservation status rankings

-

Grank: G4

Nrank: N2

Srank: S2

The glossary provides definitions for the abbreviations above and for other technical terms in this document.

1.2 Species description and biology

Species description

Gattinger's Agalinis (Agalinis gattingeri), also called Round-stem False Foxglove (NatureServe 2014) or Gattinger's False Foxglove (Brouillet et al. 2014), is a small, wiry, annual plant (Figure 1). In Ontario and in its northern range, plants are generally less than 15 cm tall with very slender opposite leaves 10 to 34 mm long and 0.4 to 1.0 mm wide. Stems of well-developed plants may branch. The pale pink, funnel-shaped flowers are about 1 to 1.5 cm long and occur individually at the end of slender stalks more than 7 mm long. Flowering occurs from late July through September, and flowers last for only one day before falling off the plant. The round, brown-yellow capsules contain numerous small (0.5 - 1.2 mm) seeds. This species is hemiparasitic, attaching to other plants by specialized roots (Canne-Hilliker 1988, 1998).

Gattinger's Agalinis is easily distinguished from Large Purple Agalinis (A. purpurea var. purpurea) and Small-flowered Agalinis (A. purpurea var. paupercula) by having flowers that stick out from the main stem on slender stalks, whereas Large Purple and Small-flowered Agalinis have flowers very close to the main stem on short stalks less than 7 mm long. However, it can be extremely difficult to distinguish Gattinger's Agalinis from Skinner's Agalinis (A. skinneriana) and Slender-leaved Agalinis (A. tenuifolia), which are sometimes found in the same locations as Gattinger's Agalinis. Many common keys (c.f. Newcomb 1977; Gleason and Cronquist 1991; Voss 1996) give insufficient or incorrect information to separate these species. A useful key can be found in Michigan Flora Online (Reznicek et al. 2011) and Voss and Reznicek (2012).

Gattinger's Agalinis can be distinguished from other members of the genus by: pale pink flowers with reddish spots and yellow lines in the funnel; flowers borne on long spreading (not stiffly upright) stalks; the lobes on the top rim of the flower upright or reflexed, but not pointing forward; leaves which spread out from the stem and are generally only one mm wide or less; a softly hairy outside surface on the lower petals; and the yellowy-green colour of the plant even when dried (Canne-Hillike 1998; J. Canne-Hilliker pers. comm. 2008; Reznicek et al. 2011). Many of these characteristics can be difficult to assess on dried specimens.

Gattinger's Agalinis has traditionally been classified in the Figwort Family (Scrophulariaceae) (Gleason and Cronquist 1991; Newmaster and Ragupathy 2012). However, genetic work on parasitic members of the Figwort and Broomrape (Orobanchaceae) families (Olmstead et al. 2001; Bennett and Mathews 2006) suggests that the parasitic species are most closely related to other Broomrape genera and evolved from a single lineage. Thus, as a hemiparasitic species, it is more appropriate to place Gattinger's Agalinis in the Broomrape Family.

Species biology

The biology of Gattinger's Agalinis is not well known. The species occurs across a wide range of latitudes and in both alvar and tallgrass prairie communities in North America (Gleason and Cronquist 1991; NatureServe 2014) which suggests a broad tolerance to varying environmental conditions such as mean temperature, day length, length of growing season, and possibly moisture regime.

Plants in the genus Agalinis are hemiparasites which gain nutrients from other plants through specialized roots (haustoria) that form attachments to the roots of a host plant (Canne-Hilliker 1988). The preferred hosts of Gattinger's Agalinis are not known but probably vary over the range of latitude. Other species of Agalinis use a broad range of hosts, and may attach to almost any neighbouring root (Musselman and Mann 1977). Some genera in the Broomrape Family have the ability to utilize as many as 79 different kinds of host species, and some are able to attach to more than one host species at the same time (Piehl 1963; Phoenix and Press 2005). Thus, Gattinger's Agalinis may or may not be restricted to only one or a few host species. On the other hand, Gattinger's Agalinis occurs only in alvars and prairies and is not found in weedy areas, which suggests that it may actually have a somewhat narrow range of hosts. According to Voss and Reznicek (2012) the genus (at least in Michigan) is thought to have diverse hosts, especially graminoids. In prairies in the Midwestern United States, most Agalinis species are likely using Indian Grass (Sorghastrum nutans) (G. Dieringer pers. comm. 2014).

As an annual plant, Gattinger's Agalinis must go through its entire life cycle from germination to fruiting and seed dispersal all in one season (within roughly an 8-10 week period). Flowering occurs from late July through September, and fruits mature during September to October. Thus, live plants of this species are present only in the second half of the summer and early fall. At other times, Gattinger's Agalinis persists in the seed bank.

Gattinger's Agalinis may have a long-lived seed bank. It is not known how long the seeds remain viable in the soil, but seeds have been known to germinate in the laboratory after more than 10 years of general storage (J. Canne-Hilliker pers. comm. 2008). At one site in the Manitoulin Region, live plants of Gattinger's Agalinis recurred after four years of documented absence (J. Jones unpublished data), and absences of three to five years have been observed for other Agalinis species (G. Dieringer pers. comm. 2014). The seeds likely need a certain level of moisture for germination (J. Jones pers. obs. 2004-2014; G. Dieringer pers. comm. 2014). However, water availability is quite variable on alvars, which often undergo extreme drought in mid-summer. This may be one reason why annual population sizes are observed to fluctuate greatly and why the species may appear to be present in some years but not in others (Canne-Hilliker 1988; Jones unpub. data). Thus, if live plants of Gattinger's Agalinis are not observed in any given year, a site cannot be presumed to be unoccupied until there have been several years of regular searches.

It is not known how Gattinger's Agalinis is pollinated, but the open, funnel shape of the flower suggests that it may attract a number of insect species (Canne-Hilliker 1988). In addition, self-fertilization has been shown to occur in the related species Skinner's Agalinis (Dieringer 1999) and Nova Scotia Agalinis (A. neoscotica)(Stewart et al. 1996), especially in small populations and in the absence of bees. It is possible this also occurs in Gattinger's Agalinis.

No information is known about dispersal distances in Gattinger's Agalinis, but the seeds do not appear to have any special adaptations for long-distance dispersal. Dispersal probably occurs when wind or other disturbance causes movement of open capsules on the long, slender stalks (Canne-Hilliker 1988).

The ecological role of Gattinger's Agalinis in either prairie or alvar is not known, but as a hemiparasite, it may have some influence on its host plants (Phoenix and Press 2005).

1.3 Distribution, abundance and population trends

The global range of Gattinger's Agalinis stretches from Ontario and Manitoba to Nebraska, Texas, Louisiana and Alabama. The species is most common in the Ozark-Ouchita uplands of Missouri and Arkansas. In the United States, Gattinger's Agalinis is found in 18 states. It has a conservation rank of rare (S1-S3 or critically imperilled to vulnerable) in the ten states where it has been given a conservation ranking (NatureServe 2014) but is common in the other eight states where it is not ranked (BONAP 2013). The species has only one extant occurrence in Michigan in a remnant oak barren last observed in 1999 (Michigan Natural Features Inventory 2007). Gattinger's Agalinis is officially listed as threatened in Wisconsin (Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources 2014), endangered in Michigan and Minnesota (Minnesota Department of Natural Resources 2013; Michigan Natural Features Inventory 2014), and on the state watch list in Indiana (Indiana Department of Natural Resources 2007).

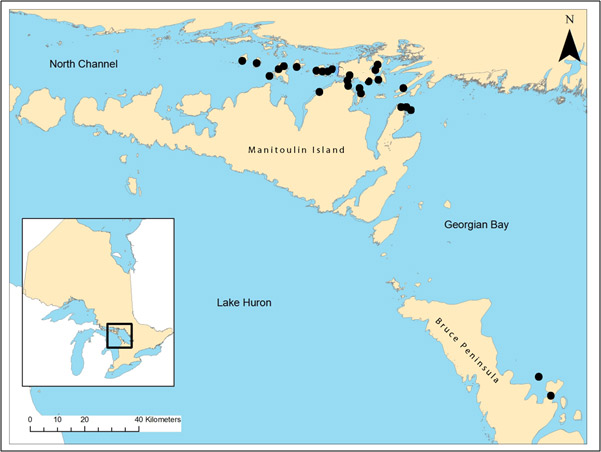

In Canada, there are 31 extant occurrences of Gattinger's Agalinis, of which 5 are in the interlake region of south-central Manitoba, and 26 are in Ontario (Figures 2 and 3; Table 1) (COSEWIC 2009a). In Ontario, Gattinger's Agalinis occurs in both tallgrass prairie and alvar. The species is found on Manitoulin Island and on smaller islands in the North Channel of Lake Huron, on the Bruce Peninsula, and on Walpole Island. Three occurrences are in protected areas, and two others are in a proposed addition to a provincial park.

At least 18 occurrences, including the most abundant, are on First Nation reserves or other lands within traditional territory, or on lands under claim by First Nations. Almost half of the populations of Gattinger's Agalinis in Ontario are on lands within the traditional territory of the First Nations of the United Chiefs and Councils of M'nidoo M'nising (UCCMM) on Manitoulin Island. Several other populations are on lands belonging to or claimed by Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve (WUIR). There are also two extant populations on lands belonging to or within the traditional territory of the Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation (formerly Chippewas of Nawash), and one extant and two historical populations on the Walpole Island First Nation (WIFN).

Total abundance of Gattinger's Agalinis in Ontario is around 70,000 individuals, based on estimates between 2000 and 2010. However, population sizes can fluctuate from year to year, and the size of the population in the seed bank is not known. Populations of other Agalinis species have been observed to vary from 2 or 3 plants to as many as 500 plants (G. Dieringer pers. comm. 2014). COSEWIC (2009a) estimated the population at approximately 11,000 individuals, but at least one new large population has been discovered since then, and new abundance information has been gathered for a few others. Other than on Walpole Island, there is little information on population trends because most sites have had only one observation. No historical populations other than on Walpole Island are known.

Long description for Figure 2

Figure 2 shows the distribution of the species in the Manitoulin Islands and Bruce Peninsula regions. Approximately two dozen locations are found from Darch Island to Big Burnt Island. Two additional sites are found on the eastern side of Bruce Peninsula near Cape Cocker.

Long description for Figure 3

Figure 3 shows the location of the extant occurrence of the species on the northern tip of Walpole Island, Ontario.

| List of Gattinger's Agalinis occurrences in Ontario | Site # | Site name | Region | Owner-ship | Abund-ance | Most recent observer and date. | Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Walpole Island FN | 1 | Walpole I. FN #1 |

Walpole | FN | At least 35 | J. Bowles & C. Jacobs 2008 | "several dozen" in 1998; "several thousand" in 1987" |

| Walpole Island FN | blank | Walpole I. FN #2 |

Walpole | FN | Not seen since 1990 | J. Bowles & C. Jacobs 2008 | Probably extirpated |

| Walpole Island FN | blank | Walpole I. FN #3 |

Walpole | FN | Not seen since 1987; "common" in 1982 | J. Bowles & C. Jacobs 2008 | Habitat very disturbed but restoration starting to be successful for other prairie species (J.M. Bowles pers. comm. 2008; C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2014). |

| Bruce Peninsula | 2 | Neyaashiinigmingr FN #1 | Bruce P. | FN | 50,000 | J. Jalava & A. Chegahno 2009 |

blank |

| Bruce Peninsula | 3 | Neyaashiinigming FN island | Bruce P. | FN | 3 | A. Chegahno 2012 | blank |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 4 | Amedroz Island | Algoma | FN/ Crown |

>200 | J. Jones 2008 | Within the traditional territory of UCCMM First Nations |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 5 | Badgely Peninsula South | Manitoulin | Crown/ Ontario Parks |

10,000 | J. Jones & WUIR staff 2009 | Killarney Coast Proposed Provincial Park/WUIR traditional territory |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 6 | Bedford Island E | Manitoulin | FN/ Crown |

>200 | J. Jones 2005 | Within the traditional territory of UCCMM First Nations |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 7 | Bedford Island W | Manitoulin | FN/ Crown |

~75 | J. Jones 2005 | Within the traditional territory of UCCMM First Nations |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 8 | Clapperton Island (Beatty Bay & NW of Baker's Bay) |

Manitoulin | FN/ Crown |

~400 | J. Jones 2005 | Within the traditional territory of UCCMM First Nations |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 9 | Clapperton Island (northern alvars and Logan Bay) | Manitoulin | FN/ Crown |

>1,300 | J. Jones 2006 | Within the traditional territory of UCCMM First Nations |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 10 | Courtney Island | Manitoulin | FN/ Crown |

> 30 | J. Jones 2004 | Within the traditional territory of UCCMM First Nations |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 11 | Darch Island | Algoma | FN/ Crown |

100's | J. Jones, 2008 | Within the traditional territory of UCCMM First Nations |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 12 | Freer Point | Manitoulin | NGO | 1,000's | J. Jones 2008 | Private nature reserve |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 13 | Goat Island (="Little Current Swing Bridge") | Manitoulin | Corp. | 59 | J. Jones 2005 | blank |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 14 | Great Cloche Island SE (Little River; W of Hwy 6) |

Manitoulin | Corp. | 100's | P. Catling & V. Brownell 1990's | See Brownell and Riley 2000 |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 15 | Great Cloche Island (Stony Pt., English Pt.) | Manitoulin | Corp. | 1000's | P. Catling & V. Brownell 1990's | See Brownell and Riley 2000 |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 16 | La Cloche Peninsula #1 (Whitefish River First Nation) | Manitoulin | FN | 1,000's | J. Jones and UCCMM staff 2010 | blank |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 17 | La Cloche Peninsula #2 (Whitefish River First Nation) | Manitoulin | FN | <100 | J. Jones and UCCMM staff 2010 | blank |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 18 | Innes Island | Algoma | FN/ Crown |

100's | J. Jones 2004 | Within the traditional territory of UCCMM First Nations |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 19 | Little Current, Harbour View Road | Manitoulin | Private/ Corp. |

Unknown | From OMNR 2013 | blank |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 20 | East Rous Island | Manitoulin | FN/ Crown |

~50 | J. Jones and UCCMM staff 2010 | Within the traditional territory of UCCMM First Nations |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 21 | West Rous Island | Manitoulin | FN/ Crown |

>1,000 | J. Jones 2005 | Within the traditional territory of UCCMM First Nations |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 22 | Strawberry Is. (northern end) | Manitoulin | Ontario Parks | >500 | J. Jones 2005 | blank |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 23 | Strawberry Island (W of Bowell Cove) | Manitoulin | Ontario Parks | >250 | J. Jones 2005 | blank |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 24 | Wikwemikong #1 | Manitoulin | FN | 36 | J. Jones & WUIR staff 2008 | blank |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 25 | Wikwemikong island #3 | Manitoulin | FN | >1,000 | J. Jones & WUIR staff 2008 | blank |

| Manitoulin Island / North Channel | 26 | Wikwemikong island #4 | Manitoulin | FN | ~500 | J. Jones & WUIR staff 2008 | blank |

| Unsurveyed sites with suitable habitat where presence is not confirmed | blank | Wikwemikong island #2 | Manitoulin | FN | Presence likely | J. Jones & WUIR staff 2008 | blank |

| Unsurveyed sites with suitable habitat where presence is not confirmed | blank | Badgely Peninsula North | Manitoulin | Crown/ Ontario Parks |

Presence likely | W. Bakowsky & W. Kershaw 2000 | Killarney Coast Proposed Provincial Park |

| Unsurveyed sites with suitable habitat where presence is not confirmed | blank | Beauty Island | Manitoulin | Private | Presence likely | blank | blank |

| Unsurveyed sites with suitable habitat where presence is not confirmed | blank | Little Cloche Island (Mary Pt.) | Manitoulin | Corp. | Presence likely | J. Jones 1996 | blank |

| Unsurveyed sites with suitable habitat where presence is not confirmed | blank | Islands off Gr. Cloche I. (Matlas, Patten, Flat, etc.) | Manitoulin | Unknown | Presence likely | J. Jones 1996 | blank |

Totals: 26 occurrences; 5 potential, unconfirmed sites

~70,000 individuals between 2000-2012, but total in seed bank is unknown.

r Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation has also been known as Chippewas of Nawash or Cape Croker.

~70,000 individuals between 2000-2012, but total in seed bank is unknown.

On Walpole Island, Gattinger's Agalinis is in serious decline. Two populations have likely become extirpated since 1988, with only one confirmed as extant in 2014. Numbers of individuals have declined from thousands in the 1980s to several dozen in 1998 to only around 35 in 2008 (COSEWIC 2009a). However, there are some challenges to surveying for Gattinger's Agalinis on Walpole Island because both Skinner's Agalinis and Slender-leaved Agalinis are also present in the same area, making it difficult to determine how many individuals of each species there are (J.M. Bowles pers. comm. 2008; C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2014). At one site where Gattinger's Agalinis may be extirpated, restoration work is underway, and native prairie plants are starting to reappear (C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2014). It remains to be seen whether restoration will improve the situation for Gattinger's Agalinis at this site.

In the Manitoulin Island region, quarrying, development, and bulldozing at three of the four corporately-owned sites (Table 1) appear to have impacted or wiped out Gattinger's Agalinis in some areas, but the extent of the impacts and potential declines is not known. Most other populations are on islands that have no human residents and that are visited infrequently. These likely have stable populations.

1.4 Habitat needs

In the Manitoulin Region and on the Bruce Peninsula, Gattinger's Agalinis occurs in alvar grasslands and jack pine savannas on Ordovician limestone. Within the Ecological Land Classification (ELC) (Lee et al. 1998), suitable microhabitat occurs in these vegetation types (Reschke et al. 1999; Brownell and Riley 2000, Jones 2004, 2005, unpub. data):

- Dry Annual Open Alvar Pavement (ALO1-2)

- Dry-Fresh Little Bluestem Open Alvar Meadow (ALO1-3)

- Dry-Fresh Poverty Grass Open Alvar Meadow (ALO1-4)

- Creeping Juniper-Shrubby Cinquefoil Dwarf Shrub Alvar (ALS1-2)

- Jack Pine – White Cedar – White Spruce Treed Alvar (Savanna) (ALT1-4).

Polygon sizes may range from 0.5 ha to more than 100 ha, with most being under 20 ha (Reschke et al. 1999; Brownell and Riley 2000; J. Jones unpublished data).

Within these vegetation types, the microhabitat is usually in areas dominated by Northern Dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis) or Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium). Gattinger's Agalinis is usually found in small patches of bare ground (bedrock or a few centimetres of organic soil) between tussocks of grass (Figure 4), often with other small annual plants such as Grooved Yellow Flax (Linum sulcatum) and Neglected Dropseed (Sporobolus neglectus). Drainage is very poor due to the underlying bedrock, so these alvars are known to spend extended periods of time in extreme conditions of drought or inundation (Reschke et al. 1999).

On Walpole Island First Nation (and in Manitoba) Gattinger's Agalinis grows in sandy loam soils in open, tallgrass prairie remnants (Walpole Island Heritage Centre 2006; J.M. Bowles pers. comm. 2008; COSEWIC 2009a). Based on the moisture regime and associate species (J.M. Bowles pers. comm. 2008), suitable microhabitat is found within the ELC community type Fresh-Moist Tallgrass Prairie (TPO2-1). Common associates include Little Bluestem as well as other prairie grasses such as Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), Switch Grass (Panicum virgatum), and Indian Grass (Sorghastrum nutans). Gattinger's Agalinis is also sometimes found in shallow swales (low, damp areas). In prairie habitats as well as on alvars, the species is usually found in shorter, sparser vegetation, on bare ground between and around tussocks of grass (Jones 2004, 2005; A. Kraus-Danielsen pers. comm. 2008; COSEWIC 2009a).

Native grasses in the habitat of Gattinger's Agalinis generally have a cespitose, tufted, or tussocked shape. In sparse vegetation, there are bare spots between tussocks, and these bare spots are the preferred microhabitat for Gattinger's Agalinis (J. Jones pers. obs. 1996-2014). By contrast, non-native and adventive grass species generally grow from longer rhizomes and create dense patches of grass cover that do not have the small gaps required by Gattinger's Agalinis (J. Jones pers. obs. 1996-2014).

Fire is used to maintain the open state of tallgrass prairies on Walpole Island (C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2014), and burning has long been a traditional part of prairie management (COSEWIC 2009a; Riley 2013). Fire has also probably occurred at the Neyaashiinigmiing site (Jalava pers. com. 2008) and may be beneficial or required by some types of alvars (Catling and Brownell 1998; Catling et al. 2001; Catling 2009). However, most Manitoulin Region alvars where Gattinger's Agalinis is found show little or no evidence of burning (Reschke et al. 1999; Jones and Reschke 2005). It is possible that these alvars did not originate from fire but are relics of post-glacial times and are becoming vegetated at an extremely slow rate (over centuries) (Jones and Reschke 2005). Alternatively, it may be that the drought-flood cycle and shallow soils perpetually inhibit growth of woody vegetation, keeping these alvars in a sparse, open state without fire (Rosén 1995; Reschke et al. 1999).

1.5 Limiting factors

The hemiparasitic nature of Gattinger's Agalinis may be a limitation if the species is restricted to a specific host plant, rather than being able to use a number of different hosts. An absence of host plants could prevent individuals of Gattinger's Agalinis from establishing or growing. Natural ecological and climatic factors may also be a limitation, especially in years with little precipitation, because some level of moisture is required for germination and alvars and prairies are frequently droughty in mid-summer (Reschke et al. 1999; COSEWIC 2009a).

Gattinger's Agalinis is an annual species that is only present as a live plant in the second half of the summer and early fall and may not be present above ground every year. Thus, time of year may affect the severity of a threat or the effectiveness of a recovery technique.

1.6 Threats to survival and recovery

Gattinger's Agalinis is a delicate plant in a sensitive habitat. As such, there are many factors that may negatively affect the plants, the habitat, or both. The main threats, whether to prairie or alvar, cause habitat degradation and loss. Threats include development, changes to ecological processes, conversion of prairie to agriculture, aggregate extraction, invasion by exotic species, fire suppression, logging and industrial activities, off-road vehicle use, livestock grazing, and trampling by pedestrians. Habitat degradation arising from a lack of awareness of the sensitivity of alvar is also a general threat.

Development and construction

Many alvar habitats containing Gattinger's Agalinis are in close proximity to the Lake Huron shoreline and thus are in demand for residential or cottage development. On Walpole Island, land for housing and other development is extremely limited but is an urgent need. Industrial and commercial development are also current threats to habitat in one area of Manitoulin Island. Constructing buildings, yards, driveways, and roads on alvar or prairie may completely eliminate suitable habitat. Negative effects of development may result from clearing vegetation, blasting bedrock to level foundations or anchor other structures, trucking in fill which introduces invasive plants and covers suitable ground, displacing shallow soil, and trampling vegetation with heavy machinery.

Changes in ecological processes

In the absence of fire or other ecological processes, open alvar and prairie habitats gradually become too densely vegetated to be suitable for Gattinger's Agalinis, which requires sparse spots in short, grassy vegetation. Short plants that produce small seeds, such as Gattinger's Agalinis, are known to be particularly susceptible to loss in fire-suppressed prairies (Leach and Givnish 1996). Crow et al. (2003) calculated a 36 percent loss of prairie vegetation on Walpole Island between 1972 and 1998, which was mostly due to natural succession from the absence of fire (Bowles 2005). Controlled burning is done at Walpole Island in some prairie habitats but may not be done often enough at all sites (C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2014). In addition, there is some evidence that burning at the wrong time of year may be reducing the population of the related species Skinner's Agalinis (Bowles unpub. data; Environment Canada 2012), and thus may affect Gattinger's Agalinis as well. Thus, changes in timing of natural processes may also be a threat.

On many of the alvars where Gattinger's Agalinis occurs, there is little or no evidence that the habitat originated from fire or is maintained by it (Jones and Reschke 2005; Jones unpub. data), but a few alvar populations do have evidence of historical burning (J. Jones unpub. data; J. Jalava pers. comm. 2008). Some researchers maintain that fire is harmful to alvars (Gilman 1995, 1997). However, it is unknown whether controlled burning on alvar would be beneficial or harmful to Gattinger's Agalinis, and correct timing of fire may be important.

Changes to the natural moisture regime may also threaten Gattinger's Agalinis. On Walpole Island, installation of drainage tiles and ditching for agriculture in the 1980s altered the hydrologic regime in some prairie sites. This probably caused the extirpation of two populations (Canne-Hiliker 1998; COSEWIC 2009a). In addition, changes in lake levels have also increased wetness in some prairie habitat on Walpole Island (COSEWIC 2009a). Some parts of the currently extant population may continue to be threatened by habitat degradation from increased wetness.

Conversion of prairie to agriculture

At Walpole Island, conversion of prairie to agriculture continues to be an on-going, current threat because the prairie land has never been sprayed and can thus be used for certified organic farming. Rental fees that are double the usual rate are being offered for prairie land (C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2014). Historically, most of North America's prairies were converted to agricultural fields, and today only about 0.5 percent of the prairie and savannah present in Ontario in the 19th century still remains (Bakowsky and Riley 1994).

Quarrying and aggregates extraction

Alvars are often in demand for quarry development because the limestone bedrock is close to the surface, and little clearing of forest and soil is necessary. Quarrying may completely destroy alvar habitat. Several alvars containing populations of Gattinger's Agalinis are within an area licensed for aggregate extraction. As per the conditions of an agreement issued under the Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA), the licence holders must do surveys for Gattinger's Agalinis before any new expansion, and should the species be found on site, appropriate mitigation measures must be undertaken (R. Steedman, pers. comm. 2014).

Invasion by exotic species

The presence of non-native species in alvar or prairie is usually the result of past disturbance which has brought in seeds or other propagules. On alvar, exotic species compete with native species for space and nutrients, and may become dominant and reduce the presence of native species (Reschke et al. 1999). Exotic species degrade habitat for Gattinger's Agalinis by taking up the small spaces between grass tussocks, as well as by shading, increasing litter accumulation, and changing other dynamics such as moisture retention (J. Jones unpublished data). Some examples of problem species in Gattinger's Agalinis alvar habitat include White Sweet Clover (Melilotus albus), Smooth Brome (Bromus inermis), and Common St. John's Wort (Hypericum perforatum) (J. Jones unpublished data). On Walpole Island, European Common Reed (Phragmites australis spp. australis) is present surrounding the habitat of Gattinger's Agalinis (C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2014), and this aggressive species is known to be a threat in other prairie habitats (WEMG 2012).

Fungal pathogens in the soil may also negatively affect the growth and abundance of Gattinger's Agalinis. Klironomos (2002) found that Gattinger's Agalinis grew more poorly in soil where fungal pathogens were present, while invasive species tended to be able to resist fungal pathogens. The presence of pathogens may be one mechanism by which invasive or weedy species affect Gattinger's Agalinis.

Logging and industrial activities

The alvar habitats of Gattinger's Agalinis are frequently used as staging areas for logging operations in adjacent forests and for storage of materials and machinery for industrial uses. Moving logs, materials, and heavy machinery across alvars tramples plants, dislodges shallow soils, and brings in exotic species that degrade habitat.

Off-road vehicle use

Off-road use of all-terrain vehicles (ATVs) and other vehicles is a threat to both the habitat and the plants of Gattinger's Agalinis. Use of ATVs especially is a serious concern because ATVs are nearly unrestricted in where they can go and do not need roads or trails. Vehicle use disturbs or destroys vegetation, displaces shallow layers of soil, and brings in weed species. Off-road vehicle use is a current threat both at Walpole Island and on Manitoulin Island.

Livestock grazing

Livestock grazing degrades habitat, reduces populations of plants, and spreads non-native weeds (Reschke et al. 1999). Historically, many alvars in the Manitoulin region had livestock on them, and the resulting weeds and degraded habitat quality are still evident. In 2014, only one Ontario Gattinger's Agalinis site (in the Manitoulin region) was being grazed (J. Jones pers. obs.), but grazing remains a potential threat in a few places.

Trampling

Foot traffic can damage vegetation and delicate plants such as Gattinger's Agalinis. In addition, on islands in the North Channel of Lake Huron (Figure 2) unmonitored camping (putting tents, fire pits, and latrines on alvars) is a threat.

Lack of public awareness

Habitat may become degraded simply as the result of a lack of awareness. Perhaps due to the sparse vegetation and lack of trees, alvars are frequently perceived as waste land where indiscriminate use doesn't matter because "there is nothing there". As a result, alvars frequently become locations for unsanctioned activities such as illegal dumping and unmonitored camping. As well, the perception of alvars as waste land often leads people to select alvars preferentially as the locations for many of the activities that cause the threats listed above. Despite an increase in awareness about alvars in Ontario in the last ten years, many people still do not know the word "alvar", even in the Manitoulin Island region where alvars are quite common.

1.7 Knowledge gaps

Gattinger's Agalinis population sizes fluctuate greatly from year to year. In some years, live plants of this species may be completely absent although seeds may remain viable in the soil. It is not clear whether population fluctuations are natural and due to inherent limitations in the life history of the species, whether they may be linked to climatic events (drought, heavy rainfall, etc.), or whether in some cases they may be due to threats. The population fluctuations create a challenge for recovery, monitoring, and protection because it can sometimes be difficult to know if the species is still present or where it may occur. Therefore, filling knowledge gaps pertaining to the magnitude, periodicity, and cause of population fluctuations will be important. Research is needed on the life history and ecological needs of Gattinger's Agalinis, particularly factors that affect reproduction and germination success, such as mechanisms that induce or break seed dormancy, seed bank viability, host plants, pollinators, and seed dispersal mechanisms. Understanding population viability in terms of both mature plants and seed banks is important to guide recovery actions and to measure recovery success.

The taxon has an extensive geographic distribution in the Midwestern United States, yet it occurs in very small populations at widely dispersed locations in Ontario. The reasons for this distribution pattern are unclear, but knowing them could potentially assist recovery. Genetic factors, including genetic isolation and the existence of evolutionarily significant units are also knowledge gaps. The results of this research may shed light on whether Ontario populations are small due to genetic inbreeding.

The effects of various management techniques on this species are unknown. For example, it is not known if hand removal of weeds and the use of controlled burning to maintain open ground would be beneficial.

A number of Bruce and Manitoulin sites with potential habitat still need to be surveyed for Gattinger's Agalinis. On the Bruce Peninsula in particular, Gattinger's Agalinis has had little attention in the past, and as a result there are a number of sites that still have not been surveyed (J. Jalava pers. comm. 2008). However, even if the species were found at some of these sites, it is still estimated that less than 10 percent of the global distribution of Gattinger's Agalinis would be within Canada.

1.8 Recovery actions completed or underway

Major Alvar studies

The International Alvar Conservation Initiative (IACI) (Reschke et al. 1999) was a large collaborative project that included surveys and research on alvars across the entire Great Lakes basin. The results contributed a great deal to knowing where alvars occur, what types of vegetation communities exist in them, and what ecological dynamics operate there. A number of alvars with Gattinger's Agalinis were surveyed as part of the IACI. As well, outreach to alvar landowners and the aggregates industry was conducted, and the ecological significance of alvars also became more widely known through magazine articles and exposure in other media.

The Ontario Alvar Theme Study (Brownell and Riley 2000) collected information on all Ontario alvars and ranked the alvars according to significance. As a result of this study, many alvars were recommended for designation as Areas of Natural and Scientific Interest (ANSI) including several that support Gattinger's Agalinis. However, no alvar ANSIs in the Manitoulin District have been confirmed (Manitoulin Planning Board 2013).

Field work

Field surveys of Gattinger's Agalinis and its habitat in both prairie and alvar were done at many locations as part of several different projects (Jones 2004, 2005; Bowles 2005; Jalava 2008; COSEWIC 2009a). All First Nations jurisdictions that have Gattinger's Agalinis on their lands have completed surveys for this species and have baseline data on where it occurs. The First Nations are working on protection and management of habitat for Gattinger's Agalinis (T. Flamand pers. comm. 2014; A. Chegahno pers. comm. 2014; C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2014; G. Migwans pers. comm. 2014).

Outreach

Educational booklets about species at risk including Gattinger's Agalinis have been prepared by WIFN (Walpole Island Heritage Centre 2006) and WUIR (Wikwemikong Department of Lands and Natural Resources 2012). The booklets are very popular and have quickly become out of print. Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation hosts a website about species at risk (Neyaashiinigmiing Nature 2014) and takes school field trips twice a year to teach youth about the alvar and its rare species (A. Chegahno pers. comm. 2014). Fact sheets have also been prepared and distributed in that community.

Stewardship and acquisitions

Two sites for Gattinger's Agalinis have been protected by acquisition. Freer Point has become a private nature reserve owned by the Escarpment Biosphere Conservancy, and Strawberry Island has become an Ontario provincial nature reserve park. WIFN has established a registered, non-profit land trust which is leasing or acquiring land for conservation purposes. Efforts by the land trust have resulted in a reduced rate of conversion of prairie and savanna habitat (COSEWIC 2009b). Some parts of the habitat where Gattinger's Agalinis is found at WIFN have been acquired (C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2014). WIFN also conducts controlled burning to maintain prairie habitats and has done hand-pulling and other management techniques to reduce exotic species (C. Jacobs pers. comm. 2014). Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation is planning construction of a boardwalk to prevent trampling of the alvar. The community is also actively working to keep vehicles on an existing road and off the vegetation (A. Chegahno pers. comm. 2014).

Policy and planning

WUIR and Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation are in the process of preparing land use plans that will guide future development of their lands. In the WUIR plan, alvars and lands with species at risk (SAR), including Gattinger's Agalinis, are already designated areas of concern and will have some protection during planning (J. Manitowabi pers. comm. 2014). In addition, the community is working on a process where an assessment of SAR will be done before new projects get approved (T. Flamand pers. comm. 2014).

In the Manitoulin Region, a new official plan that will guide land use and development is in the process of being approved (Manitoulin Planning Board 2013). The new official plan restricts site alteration in alvar habitats unless an environmental study shows there will be no impacts from the proposed project. Local municipalities still have to develop by-laws to implement the new plan, but this is expected in the next two years.

2 Recovery

2.1 Recovery goal

Maintain self-sustaining populations of Gattinger's Agalinis in their current distribution in Ontario by maintaining and protecting habitat and reducing other threats.

2.2 Protection and recovery objectives

The protection and recovery objectives (Table 2) and the approaches to recovery (Table 3) are intended to assist all jurisdictions, whether they be governments, First Nations, private or corporate landowners, or non-governmental organizations, with guidance on recovery.

| No. | Protection or recovery objective |

|---|---|

| 1 | Assess threats and undertake actions for mitigation and reduction. |

| 2 | Use policy tools, where appropriate, to protect Gattinger's Agalinis. |

| 3 | Raise awareness about Gattinger's Agalinis and its sensitive habitats. |

| 4 | Fill knowledge gaps. |

2.3 Approaches to recovery

| Recovery objectives | Relative priority | Relative timeframe | Recovery theme | Approach to recovery | Threats or knowledge gaps addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Assess threats and undertake actions for mitigation and reduction. | Critical | Short-term | Protection, Management, Monitoring and Assessment, Outreach, Stewardship | 1.1 Liaise with and support UCCMM and Neyaashiinigmiing in recovery actions developed by the community. Some actions may include the following.

|

Development/Construction Invasion by Exotic Species Logging and Industrial Activities Indiscriminate ATV use Trampling Lack of Public Awareness |

| 1. Assess threats and undertake actions for mitigation and reduction. | Critical | On-going | Protection, Management, Stewardship | 1.2 Liaise with and support WIFN and WUIR in recovery actions developed by the community.

|

Development/Construction Conversion of Prairie to Agriculture Changes in Ecological Processes Invasion by Exotic Species Logging and Industrial Activities Indiscriminate ATV use Trampling Lack of Public Awareness |

| 1. Assess threats and undertake actions for mitigation and reduction. | Necessary | On-going | Outreach | 1.3 Assist with leasing and/or acquisitions of land for conservation on WIFN if requested. | Conversion to Agriculture Changes in Moisture Regime |

| 1. Assess threats and undertake actions for mitigation and reduction. | Necessary | On-going | Protection, Management, Education and Outreach, Stewardship |

1.4 Ensure appropriate zoning and protection within parks and protected areas, which would include the following.

|

Changes in Ecological Processes Invasion by Exotic Species Indiscriminate ATV use Trampling Lack of Public Awareness |

| 1. Assess threats and undertake actions for mitigation and reduction. | Necessary | Long-term | Protection | 1.5 Provide enhanced enforcement of ESA 2007 and SARA if stewardship and other actions are not effective. | Development/Construction Logging and Industrial Activities Indiscriminate ATV use Trampling Lack of Public Awareness |

| 2. Use policy tools, where appropriate, to protect Gattinger's Agalinis. | Critical | Short-term | Protection | 2.1 Ensure alvar ANSIs become recognized in the Manitoulin Official Plan.

|

Development/Construction Quarrying and Aggregates Extraction Lack of Public Awareness |

| 2. Use policy tools, where appropriate, to protect Gattinger's Agalinis. | Critical | Short-term | Protection | 2.2 Design community-based policies to protect alvars, prairies, and Gattinger's Agalinis on First Nations lands.

|

Development/Construction Quarrying and Aggregates Extraction Invasion by Exotic Species Logging and Industrial Activities Lack of Public Awareness |

| 2. Use policy tools, where appropriate, to protect Gattinger's Agalinis. | Critical | Short-term | Protection | 2.3 Ensure that alvars and SAR are considered in municipal by-laws by:

|

Development/Construction Quarrying and Aggregates Extraction Invasion by Exotic Species Logging and Industrial Activities Lack of Public Awareness |

| 3. Raise awareness about Gattinger's Agalinis and its sensitive habitats. | Critical | Short-term | Education and Outreach, Communications | 3.1 Discuss Gattinger's Agalinis and alvar with corporate landowners and aggregate operators.

|

Quarrying & Aggregates Extraction Logging and Industrial Activities Livestock Grazing Invasion by Exotic Species Development/Construction Lack of Public Awareness |

| 3. Raise awareness about Gattinger's Agalinis and its sensitive habitats. | Critical | On-going | Protection, Communications, Stewardship |

3.2 Discuss Gattinger's Agalinis with municipal planners.

|

Development/Construction Quarrying and Aggregates Extraction Logging and Industrial Activities Indiscriminate ATV use Livestock Grazing Trampling Lack of Public Awareness |

| 3. Raise awareness about Gattinger's Agalinis and its sensitive habitats. | Necessary | On-going | Protection, Monitoring, Communications, Stewardship |

3.3Discuss Gattinger's Agalinis with enforcement officials.Discuss Gattinger's Agalinis with enforcement officials.

|

Invasion by Exotic Species Logging and Industrial Activities Indiscriminate ATV use Trampling Lack of Public Awareness |

| 3. Raise awareness about Gattinger's Agalinis and its sensitive habitats. | Beneficial | On-going | Education and Outreach, Communications | 3.4 Assist with reprinting WUIR and WIFN educational materials and assist with preparations of materials for UCCMM and Neyaashiinigmiing communities if requested.

|

Any or all threats |

| 4. Fill knowledge gaps. | Necessary | Long-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment, Research |

4.1 Develop and undertake annual monitoring to assess population levels and fluctuations, and to monitor threats.

|

Knowledge gaps on size, frequency, and cause of fluctuations in abundance; current status of the populations and active threats; status of conditions of habitats; response of plants/populations to recovery actions. |

| 4. Fill knowledge gaps. | Necessary | Long-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment, Research |

4.2 Study life history and biological needs of Gattinger's Agalinis as research becomes feasible.

|

Knowledge gaps on how natural limitations and threats affect the populations; whether fire to maintain habitat may harm the plants; whether and when to use fire as a management tool. |

| 4. Fill knowledge gaps. | Necessary | Long-term | Inventory, Monitoring and Assessment, Research |

4.3 Study Gattinger's Agalinis seed banks.

|

Knowledge gaps on population viability; better measures of abundance; better tracking of effects of threats and of recovery success. |

Narrative to support approaches to recovery

Abundance of Gattinger's Agalinis is subject to natural fluctuations, and the magnitude and periodicity of the fluctuations are unknown. In addition, if fluctuations turn out to be linked to climatic events, such as drought or exceptional rainfall, changes in abundance levels may be unrelated to threats. Therefore, abundance is currently not a useful measure for recovery success. Until knowledge gaps on abundance and biological factors are filled, the recovery goal is to maintain self-sustaining populations of Gattinger's Agalinis, where self-sustaining will mean that Gattinger's Agalinis is present in most of the years it is surveyed.

It is recognized that First Nations will have a key role to play in recovery for Gattinger's Agalinis. First Nations community members are in contact with many of the sites where this species is found, so it is likely that community members will need to be involved on many levels in order for recovery to be successful.

Many Gattinger's Agalinis populations are on lands where there is little presence of ownership or jurisdictional authority, be it First Nations, Crown, or a corporation or municipality. Some of these lands are under land claim by First Nations, or are included in lands proposed for provincial park status. During the time that may elapse until legal ownership is clarified and resolved, recovery actions may still be undertaken through many different means. It is recommended that the various jurisdictions contact each other and work together for the protection and recovery of this species.

Gattinger's Agalinis has narrow habitat requirements that occur in a very restricted geographic range in Ontario. The distribution of the species is unlikely to expand much, even with recovery efforts, because suitable alvar and prairie habitat is limited. Furthermore, the main threats to Gattinger's Agalinis are threats to its habitat. The two historical locations that are known (from Walpole Island) were both lost due to loss of habitat. Therefore, the recovery goal for this species focuses on maintaining the existing distribution of the species by maintaining existing habitat and populations. Reintroduction and augmentation of populations with extra individuals or seeds is not contemplated for the foreseeable future.

2.4 Area for consideration in developing a habitat regulation

Under the ESA, a recovery strategy must include a recommendation to the Minister of Natural Resources and Forestry on the area that should be considered in developing a habitat regulation. A habitat regulation is a legal instrument that prescribes an area that will be protected as the habitat of the species. The recommendation provided below by the author will be one of many sources considered by the Minister when developing the habitat regulation for this species.

Considerations

Determining occupancy may be a challenge. Gattinger's Agalinis is an annual that arises from a seedbank. Population sizes in this species may fluctuate from year to year, and there may be some years when live plants do not appear above the ground at all. Locating this small wiry plant among grass can be extremely difficult if the plants are not in flower. Gattinger's Agalinis is a late-blooming species, so presence/absence of live plants for any given year is best determined from late August to approximately the end of September when some plants will be in flower.

Furthermore, the maximum time that seeds of Gattinger's Agalinis remain viable in the soil is not known, but seeds have germinated in the laboratory after 10 years of storage. In anecdotal reports, live plants of several Agalinis species have been known to recur after absences of three to five years (J. Jones pers. obs. 2004-2014; G. Dieringer pers. comm. 2014), but in the field, no species of Agalinis has been documented to recur after an absence of more than 10 years. It is recognized that this has not been studied specifically for Gattinger's Agalinis and that seed viability is a knowledge gap. However, until further studies are done, it is reasonable to presume a ten year viability period for Gattinger's Agalinis seeds in the field.

Thus, even if live plants of Gattinger's Agalinis are not seen for several years, it cannot be presumed that the habitat is unoccupied. It is recommended that for any site where Gattinger's Agalinis has previously been reported, occupancy be presumed to a maximum of ten years' absence of live plants. If suitable habitat for Gattinger's Agalinis is no longer present, it is recommended that occupancy still be presumed for the 10 year period in case management actions or natural disturbance may permit habitat to be restored, potentially allowing live plants to recur.

The following methodology is recommended to determine that Gattinger's Agalinis has been absent for more than 10 years. Surveys should be done by a qualified person every year for 10 consecutive years, and in each year, brief surveys to determine presence/absence are conducted once a week from August 20 to September 30. If Gattinger's Agalinis is not found in any of these surveys, it may be concluded that Gattinger's Agalinis is no longer present.

It is recommended that the habitat to be considered for regulation be prescribed as follows.

- All areas where Gattinger's Agalinis grows or has grown unless surveys show that the species has been absent for more than 10 years.

- Any new areas where the species becomes discovered in the future.

- The area where live Gattinger's Agalinis plants grow or have previously grown, and the entire alvar or prairie ELC vegetation type polygon (listed above) in which Gattinger's Agalinis is or has been found. Although only a small portion of the polygon may be occupied, the entire polygon is required for a number of reasons. First, alvars and prairies are not static communities. Rather, there are dynamics (e.g., fire, flooding) that act to create, fill up, destroy, and recreate the sparse patches that are suitable for Gattinger's Agalinis. These ecological processes act over the entire alvar or prairie community, not just in the open spots where the species is found, so space is required to allow such processes to take place. Second, the extent of occupancy in the seed bank is not known, and it is possible that if burning or other processes occur, Gattinger's Agalinis may recur in spots that previously did not appear occupied or that did not appear suitably sparse. As well, suitable natural habitat is extremely limited, so where the species occurs it is important to protect all of the existing habitat. In addition, space is needed to allow dispersal and establishment of the species. Finally, the pollinators for this species are likely generalists that require other species and more area for survival.

- An additional distance of 50 m around the outside of the polygon, so that in cases where individuals occur at the edge of a polygon, there will be sufficient distance from activities in adjacent areas to prevent impacts, such as changes in drainage that could affect soil moisture. Although the area around the outside of a polygon may contain unsuitable non-alvar or non-prairie habitat, it is recommended that this area be included as a protective measure.

A distance of 50 m has been shown to provide a minimum critical function zone to ensure microhabitat properties for rare plants. A study on micro-environmental gradients at habitat edges (Matlack 1993) and a study of forest edge effects (Fraver 1994) found that effects could be detected as far as 50 m into habitat fragments. Forman and Alexander (1998) and Forman et al. (2003) found that most roadside edge effects on plants resulting from construction and repeated traffic have their greatest impact within the first 30 m to 50 m.

Reschke et al. (1999) studied the hydrology of alvars and found that most water on alvars derived from surface rainwater rather than from ground water. They also found that surface waters outside the alvars were not the source of flooded grasslands at their study sites. Therefore, for alvars, 50 m may be a sufficient distance to protect the hydrological regime. On prairies, where there are deeper soils with potential influence from ground water, it is recognized that additional distances may be warranted to protect the soil moisture regime. However, no research was available to inform the recommendation of a particular protective distance. Therefore, for prairies, it is recommended that the 50 m distance be used as a guideline until additional information becomes available,

It is recommended that existing infrastructure, such as roads, buildings, and planted vegetation be excluded from the habitat regulation.

Glossary

- Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC):

-

The committee established under section 14 of the Species at Risk Act that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Canada.

- Committee on the Status of Species at Risk in Ontario (COSSARO):

-

The committee established under section 3 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that is responsible for assessing and classifying species at risk in Ontario.

- Conservation status rank: A rank assigned to a species or ecological community that conveys the degree of rarity of the species or community at the global (G), national (N) or subnational (S) level. These ranks, termed G-rank, N-rank and S-rank, are not legal designations. The conservation status of a species or ecosystem is ranked on a scale from 1 to 5, preceded by the letter G, N or S reflecting the appropriate geographic scale of the assessment. The numbers mean the following:

-

1 = critically imperilled: At very high risk of extinction due to extreme rarity (often 5 or fewer populations), very steep declines, or other factors.

2 = imperilled: At high risk of extinction or elimination due to very restricted range, very few populations, steep declines, or other factors.

3 = vulnerable: At moderate risk of extinction or elimination due to a restricted range, relatively few populations, recent and widespread declines, or other factors.

4 = apparently secure: Uncommon but not rare; some cause for long-term concern due to declines or other factors.

5 = secure: Common; widespread and abundant. - Endangered Species Act, 2007 (ESA):

-

The provincial legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Ontario.

- Germinate:

-

The process in which a seed begins to grow by breaking dormancy and sprouting roots and shoots.

- Hemiparasite:

-

A plant that gets nutrition from both photosynthesis and by taking it from other species.

- Occurrence:

-

All the patches of a species that are within one kilometre of each other. Patches separated by more than one kilometre are considered different occurrences or separate populations.

- Propagule:

-

Parts of a plant that disperse and allow growth to occur in a new place. Propagules may be fruits, seeds, or any other part of the plant that is capable of rooting and becoming established.

- Rhizome:

-

A horizontal underground stem from which additional stems and roots may grow, resulting in a colonial or rhizomatous growth form.

- Species at Risk Act (SARA):

-

The federal legislation that provides protection to species at risk in Canada. This act establishes Schedule 1 as the legal list of wildlife species at risk. Schedules 2 and 3 contain lists of species that at the time the Act came into force needed to be reassessed. After species on Schedule 2 and 3 are reassessed and found to be at risk, they undergo the SARA listing process to be included in Schedule 1.

- Sessile:

-

Leaves, flowers, or other plant structures that are attached directly at their base with no stalk.

- Species at Risk in Ontario (SARO) List:

-

The regulation made under section 7 of the Endangered Species Act, 2007 that provides the official status classification of species at risk in Ontario. This list was first published in 2004 as a policy and became a regulation in 2008.

References

Bakowsky, W.D. and J.L. Riley. 1994. A survey of the prairies and savannas of southern Ontario. Proceedings of the Thirteenth North America Prairie Conference: 7-16. Edited by R.G. Wickett, P.D. Lewis, A. Woodliffe, and P. Pratt.

Bennett, J.R. and S. Mathews. 2006. Phylogeny of the parasitic plant family Orobanchaceae inferred from phytochrome A. American Journal of Botany 93(7):1039-1051.

BONAP. 2013. Agalinis gattingeri, in North American Plant Atlas, Biota of North America Program. [accessed September 6, 2014].

Bowles, J.M. 2005. Draft Walpole Island ecosystem recovery strategy. Walpole Island Heritage Centre, Environment Canada and The Walpole Island Recovery Team.

Bowles, Jane M. pers. comm. 2008. Email correspondence to J. Jones. August 27, 2008. Consulting biologist and curator, herbarium University of Western Ontario, London. (Deceased 2013).

Brouillet, L., F. Coursol, S.J. Meades, M. Favreau, M. Anions, P. Bélisle and P. Desmet. 2014. Agalinis gattingeri (Small) Small in VASCAN, the Database of Vascular Plants of Canada. [accessed January 19 and August 31, 2014].

Brownell, V.R. and J.L. Riley. 2000. The Alvars of Ontario: Significant Natural Areas in the Ontario Great Lakes Region. Federation of Ontario Naturalists, Don Mills, Ontario. 269 pp.

Canne-Hiliker, J.M. 1988. COSEWIC status report for Gattinger's Agalinis (Agalinis gattingeri). Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa. 19 pp.

Canne-Hiliker, J.M. 1998. Update COSEWIC status report for Gattinger's Agalinis (Agalinis gattingeri). Draft copy for review [update], Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada, Ottawa. 4 pp.

Canne-Hiliker, Judith M. pers. comm. 2008. Email correspondence to J. Jones. September 9, 2008. Professor emeritus, University of Guelph, Ontario. (Deceased 2013).

Catling, P. 2009. Vascular plant diversity in burned and unburned alvar woodland: more evidence of the importance of disturbance to biodiversity and conservation. Canadian Field-Naturalist 123(3):240-245.

Catling, P.M. and V.R. Brownell. 1998. Importance of fire in alvar ecosystems-evidence from the Burnt Lands, eastern Ontario. Canadian Field-Naturalist 112(4):661-667.

Catling, P.M., A. Sinclair, and D. Cuddy. 2001. Vascular plants of a successional alvar burn 100 days after a severe fire and their mechanisms of re-establishment. Canadian Field-Naturalist115(2):214-222.

Chegahno, Anthony. pers. comm. 2014. Telephone correspondence to J. Jones. January 31, 2014. Elder, band councillor, and species at risk specialist, Neyaashiinigmiing First Nation.

COSEWIC. 2009a. Update COSEWIC status report on Gattinger's Agalinis (Agalinis gattingeri). Provisional draft. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 28 pp.

COSEWIC. 2009b. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Pink Milkwort (Polygala incarnata) in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 24 pp.

Crow, C., J. Demelo, J. Hayes, J. Wells and T. Hundey. 2003. Walpole Island land use change 1972-1998. Unpublished class report, Department of Geography, University of Western Ontario.

Dieringer, G. 1999. Reproductive biology of Agalinis skinneriana (Scrophulariaceae), a threatened species. Journal of the Torrey Botanical Society 126:289-295.

Dieringer, Gregg. pers. comm. 2014. Email correspondence to J. Jones. September 16, 2014. Professor of Biology, Northwest Missouri State University, Maryville, MO.

Environment Canada. 2012. Recovery Strategy for the Skinner's Agalinis (Agalinis skinneriana) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. iv + 16 pp.

Flamand, Theodore. pers. comm. 2014. In person communication to J. Jones. January 15, 2014. Species at Risk program coordinator, Wikwemikong Department of Lands and Natural Resources.

Forman, R.T.T. and L.E. Alexander. 1998. Roads and their major ecological effects. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 29:207-231.

Forman, R.T.T., D. Sperling, J.A. Bissonette, A.P. Clevenger, C.D. Cutshall, V.H. Dale, L. Fahrig, R. France, C.R. Goldman, K. Heanue, J.A. Jones, F.J. Swanson, T. Turrentine, and T.C. Winter 2003. Road ecology: Science and solutions. Island Press. Covelo, CA.

Fraver, S. 1994. Vegetation responses along edge-to-interior gradients in the mixed hardwood forests of the Roanoke River Basin, North Carolina. Conservation Biology 8(3):822-832.

Gilman, B. 1995. Vegetation of Limerick cedars: pattern and process in alvar communities. Doctoral dissertation, State University of New York. College of Environmental Science and Forestry, Syracuse.

Gilman, B. 1997. Recent Fire History Data for the Perch River Barrens Alvar Site. Unpublished report for The Nature Conservancy's Alvar Conservation Initiative.

Gleason, H.A. and A. Cronquist. 1991. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, 2nd ed. New York Botanical Garden, 910 pp.

Indiana Department of Natural Resources. 2007. Endangered, Threatened, Rare and Extirpated Plants of Indiana (PDF; 82.3 Kb) [accessed January 21, 2014].

Jacobs, Clint. pers. comm. 2014. Telephone correspondence to J. Jones. January 21, 2014. Walpole Island Heritage Centre and Walpole Island Land Trust.

Jalava, J.V. 2008. Alvars of the Bruce Peninsula: A Consolidated Summary of Ecological Surveys. Prepared for Parks Canada, Tobermory, Ontario. iv + 350 pp + appendices.

Jalava, Jarmo V. pers. comm. 2008. In person correspondence to J. Jones. November 28, 2008. Consulting Ecologist, Stratford, Ontario.

Jones, J.A. 2004. Alvars of the North Channel Islands. Report to NatureServe Canada, Ottawa, Ontario.

Jones, J.A. 2005. More alvars of the North Channel Islands and the Manitoulin Region: Report prepared for Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Espanola Office.

Jones, J.A. and C. Reschke. 2005. The role of fire in Great Lakes alvar landscapes. The Michigan Botanist 44(1):13-27.

Klironomos, J.N. 2002. Feedback with soil biota contributes to plant rarity and invasiveness in communities. Nature 417:67-70.

Krause-Danielsen, Allison. pers. comm. 2008. In person correspondence to J. Jones. November 21, 2008. Formerly with Manitoba Conservation Data Centre, Winnipeg MB.

Leach, M.K. and T.J. Givnish. 1996. Ecological determinants of species loss in remnant prairies. Science 273:1555-1558.

Lee, H.T., W.D. Bakowsky, J. Riley, J. Bowles, M. Puddister, P. Uhlig, and S. McMurray 1998. Ecological land classification for southern Ontario: first approximation and its application. SCSS Field Guide FG-02. Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Southcentral Science Section, North Bay, Ontario.

Manitoulin Planning Board. 2013. District of Manitoulin Official Plan, final draft December 2013 (PDF; 2.84 Mb). [accessed January 21, 2014].

Manitowabi, John., pers. comm. 2014. In person correspondence to J. Jones. January 17, 2014. Planner, Wikwemikong Department of Lands and Natural Resources.

Matlack, G.R. 1993. Microenvironment variation within and among forest edge sites in the eastern United States. Biological Conservation 66(3):185-194.

Michigan Natural Features Inventory. 2007. Agalinis gattingeri, in Rare Species Explorer [accessed Sep 6, 2014]

Michigan Natural Features Inventory. 2014. Michigan's Special Plants. [accessed January 21, 2014].

Migwans, G'mewin. pers. comm. 2014. In person correspondence to J. Jones. January 17, 2104. Community Engagement Coordinator, United Chiefs and Councils of M'nidoo M'nising, M'chigeeng, Ontario.

Minnesota Department of Natural Resources. 2013. Minnesota's list of endangered, threatened, and special concern species[accessed January 21, 2014].

Musselman, L.J. and W.F. Mann. 1977. Host plants of some Rhinanthoideae (Scrophulariaceae) of Eastern North America. Plant Systematics and Evolution 127:45-53.

NatureServe. 2014. Agalinis gattingeri in NatureServe Explorer: an online encyclopedia of life. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. [accessed January 20, 2014]

Newcomb, L. 1977. Newcomb's Wildflower Guide. Little, Brown, and Company, Toronto. 490 pp.

Newmaster, S.G. and S. Ragupathy. 2012. Flora Ontario – Integrated Botanical Information System (FOIBIS), Phase I. University of Guelph, Canada. [accessed January 19, 2014]

Neyaashiinigmiing Nature. 2014. Caring for the land, water, and rare species. [accessed January 31, 2014]

Olmstead, R.C., C.W. Depamphilis, A.D. Wolfe, N.D. Young, W.J. Elisens, and P.J. Reeves. 2001. Disintegration of the Scrophulariaceae. American Journal of Botany 88:348-361.

Phoenix, G.K. and M.C. Press. 2005. Linking physiological traits to impacts on community structure and function: the role of root hemiparasitic Orobanchaceae (ex-Scrophulariaceae). Journal of Ecology 93:67-78.

Piehl, M.A. 1963. Mode of attachment, haustorium structure, and hosts of Pedicularis canadensis.American Journal of Botany 50(10):978-985.

Reschke, C., R. Reid, J. Jones, T. Feeney and H. Potter 1999. Conserving Great Lakes Alvars: Final Technical Report of the International Alvar Conservation Initiative. The Nature Conservancy, Chicago, Illinois. 230 pp.

Reznicek, A.A., E.G. Voss, and B.S. Walters. 2011. Agalinis gattingeri in Michigan Flora Online. University of Michigan. [accessed January 18, 2014]

Riley, J.L. 2013. The Once and Future Great Lakes Country. McGill Queens University Press, Montreal. 488 pp.

Rosén, E. 1995. Periodic droughts and long-term dynamics of alvar grassland vegetation on Öland, Sweden. Folia Geobotanica et Phytotoxonomica 30(2):131-140.

Steedman, Ruth. pers. comm. 2014. Email correspondence to J. Jones. January 24, 2014. Aggregate Officer, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Espanola Area Office.

Stewart, H.M., S.C. Stewart, and J.M. Canne-Hilliker. 1996. Mixed mating system in Agalinis neoscotica (Scrophulariaceae) with bud pollination and delayed pollen germination. International Journal of Plant Science 157(4):501-508.

Voss, E.G. 1996. Michigan Flora: Vol. 3. Cranbrook Institute of Science and Regents of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan. 622 pp.

Voss, E.G. and A.A. Reznicek. 2012. Field Manual of Michigan Flora. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor, MI. 990 pp.

Walpole Island Heritage Centre. 2006. E-niizaanag Wii-Ngoshkaag Maampii Bkejwanong: Species at Risk on the Walpole Island First Nation. Bkejwanong Natural Heritage Program. 130 pp.

WEMG. 2012. Willowleaf Aster (Symphyotrichum praealtum) 2011 annual monitoring report. The Windsor-Essex Parkway. Windsor-Essex Mobility Group and Parkway Infrastructure Constructors document no. PIC-83-225-0224.

Wikwemikong Department of Lands and Natural Resources. 2012. Interesting plants and shrubs of Wikwemikong. Wikwemikong Unceded Indian Reserve, Wikwemikong, Ontario. 48 pp.

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 2014. Endangered and Threatened Species of Wisconsin (PDF; 173 Kb). [accessed January 21, 2014]