Recovery Strategy for the Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in Canada - 2016

Oregon Forestsnail

2016

Recovery Strategy for the Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in Canada - 2016

Recommended citation:

Environment Canada. 2016. Recovery Strategy for the Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in Canada. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment Canada, Ottawa. 23 pp. + Annex.

For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee of the Status of Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry.

Cover illustration: © Jennifer Heron

Également disponible en français sous le titre

« Programme de rétablissement de l'escargot-forestier de Townsend (Allogona townsendiana) au Canada »

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Recovery Strategy for the Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in Canada - 2016

Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments agreed to work together on legislation, programs, and policies to protect wildlife species at risk throughout Canada.

In the spirit of cooperation of the Accord, the Government of British Columbia has given permission to the Government of Canada to adopt the "Recovery Strategy for Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in British Columbia" (Part 2) under Section 44 of the Species at Risk Act. Environment Canada has included an addition which completes the SARA requirements for this recovery strategy.

The federal Recovery Strategy for the Oregon Forestsnail in Canada consists of two parts:

- Part 1 – Federal Addition to the "Recovery Strategy for Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in British Columbia", prepared by Environment Canada.

- Part 2 – "Recovery Strategy for Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in British Columbia", prepared by the Oregon Forestsnail Recovery Team for the British Columbia Ministry of Environment.

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years.

The Minister of the Environment is the competent minister under SARA for the Oregon Forestsnail and has prepared the federal component of this recovery strategy (Part 1), as per section 37 of SARA. To the extent possible, it has been prepared in cooperation with British Columbia Ministry of Environment, the Department of National Defence, and the British Columbia Conservation Data Centre. SARA section 44 allows the Minister to adopt all or part of an existing plan for the species if it meets the requirements under SARA for content (sub-sections 41(1) or (2)). The attached provincial recovery plan (Part 2 of this document) for the species was provided as science advice to the jurisdictions responsible for managing the species in British Columbia. Environment Canada has prepared this federal addition to meet the requirements of SARA.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment Canada, or any other jurisdiction, alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Oregon Forestsnail and Canadian society as a whole.

This recovery strategy will be followed by one or more action plans that will provide information on recovery measures to be taken by Environment Canada and other jurisdictions and/or organizations involved in the conservation of the species. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

The recovery strategy sets the strategic direction to arrest or reverse the decline of the species, including identification of critical habitat to the extent possible. It provides all Canadians with information to help take action on species conservation. When the recovery strategy identifies critical habitat, there may be future regulatory implications, depending on where the critical habitat is identified. SARA requires that critical habitat identified within federal protected areas be described in the Canada Gazette, after which prohibitions against its destruction will apply. For critical habitat located on federal lands outside of federal protected areas, the Minister of the Environment must either make a statement on existing legal protection or make an order so that the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat applies. For critical habitat located on non-federal lands, if the Minister of the Environment forms the opinion that any portion of critical habitat is not protected by provisions in or measures under SARA or other Acts of Parliament, and not effectively protected by the laws of the province or territory, SARA requires that the Minister recommend that the Governor in Council make an order to extend the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat to that portion. The discretion to protect critical habitat on non-federal lands that is not otherwise protected rests with the Governor in Council.

The following sections have been included to address specific requirements of SARA that are either not addressed in the "Recovery Plan for Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in British Columbia" (see Part 2 of this document, referred to hereafter as the "provincial recovery plan"), or that need more detailed comment. In some cases, these sections may also include updated information or modifications to the provincial recovery plan for adoption by Environment Canada.

This section augments section "Species Status Information" (section 2) in the provincial recovery plan.

Legal Status: SARA Schedule 1 (Endangered) (2005).

Based on recent and historic records combined, the global range extent is estimated at 135,000 km2. The extent of occurrence for B.C. is estimated to be 3313 km2 (including the unsuitable Strait of Georgia between Vancouver Island and the lower Fraser Valley). Although the Canadian population in the Fraser Valley only covers a small proportion of the global range, species experts predict that 10-20% of the global population of Oregon Forestsnail could be in Canada (J. Heron, B.C. Ministry of Environment, pers. comm. (2012).

This section replaces "Population and Distribution Goal" (section 5.1) in the provincial recovery plan. Environment Canada has identified the following Population and Distribution Objective for Oregon Forestsnail:

The following statement augments "Rationale for the Population and Distribution Goal" (section 5.2) from the provincial recovery plan. The population and distribution objective includes currently occupied known and unknown natural occurrences of Oregon Forestsnail; it does not extend to sites established through snail salvage and translocation.

The following text replaces the final paragraph in “Actions Already Completed or Underway” (section 6.1) in the provincial recovery plan:

There are ongoing surveys and management for species at risk, including Oregon Forestsnail, atArea Support Unit (ASU) Chilliwack (Department of National Defence; A. Manweiler, pers. comm., 2011).

This section replaces “Information on Habitat Needed to Meet Recovery Goal” (section 7) in the provincial recovery plan.

Section 41(1)(c) of SARA requires that recovery strategies include an identification of the species’ critical habitat, to the extent possible, as well as examples of activities that are likely to result in its destruction.

This section replaces "Description of Survival/Recovery Habitat" (section 7.1) in the provincial recovery plan.

Critical habitat can only be partially identified at this time. A schedule of studies (section 3.2) has been developed to provide the information necessary to complete the identification of critical habitat that will be sufficient to meet the population and distribution objective. The identification of critical habitat will be updated when the information becomes available, either in a revised recovery strategy or action plan(s).

Critical habitat for Oregon Forestsnail is identified based on known extant and historical occurrences surrounded by an area with a radius equivalent to the maximum known home range/displacement distance for the species, 32.2 m (Edworthy et al. 2012). Though Oregon Forestsnail can be found in edge habitats, the species requires habitat features provided by interior forests (or their functional equivalents) to complete their life cycle. As such, a 50 m Critical Function Zone is also added to maintain minimum constituent microhabitat properties where the snails are found (based on average edge effects distances in coastal forests (Kremsater and Bunnell 1999)). For areas where Terrestrial Ecosystem Mapping (TEM) is available (Blackwell and Associates 2003; Durand 2010; Madrone Environmental Services Ltd. 2008, 2006; Metro Vancouver, unpublished data;), the critical habitat also includes the TEM polygons intersecting the occurrence. The TEM polygon must meet or exceed the minimum area requirement described above, and contain at least one ecosystem type capable of providing the biophysical attributes of critical habitat.

The areas containing critical habitat for Oregon Forestsnail, totaling 1402 ha, are presented in Appendix 1 Figures 1-12. Within the mapped areas, locations that do not possess the biophysical attributes listed below are not critical habitat.

4.1.1 Biophysical attributes of critical habitat

In general, Oregon Forestsnail habitat is low elevation (<360 m above sea level) and has a site context that promotes persistent high moisture. This can include ravines, gullies and depressions with both permanent and ephemeral watercourses; the edges of streams, wetlands, seasonally flooded areas or wet lowlands; moist forest interfaces (including adjacent edge habitats); and moist, densely-vegetated meadows (Oregon Forestsnail Recovery Team 2012). Within these habitats, specific features must be present to support a number of critical functions, including overall maintenance of the moist microclimate, as well as provision of cover; aestivation, nesting, mating, and oviposition substrate; and forage. These critical features include:

- intact deciduous and/or mixed wood and/or dense shrub or herbaceous canopy, to maintain the moist microclimate;

- patches of Stinging Nettle (Urtica dioica), to support feeding, mating, oviposition, and healthy shell growth (Oregon Forestsnail Recovery Team 2012; B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2014; Edworthy et al. 2012; Steensma et al. 2009);

- dense understory vegetation, to provide cover and maintain moisture; and

- coarse woody debris and leaf litter, to provide cover and substrate for aestivation and nesting.

This section replaces the "Studies Needed to Describe Survival/Recovery Habitat" (section 7.2) in the provincial recovery plan.

The purpose of the schedule of studies is to outline the studies required to identify the critical habitat necessary to meet the population and distribution objectives for the species.

| Description of activity | Outcome/rationale | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Conduct habitat assessments at known Oregon Forestsnail sites (e.g., coarse woody debris, moisture, soil attributes, plant species composition, etc.). | Data collected in known Oregon Forestsnail habitats will facilitate more accurate identification of key habitat features that predict Oregon Forestsnail presence, and support the development of a habitat suitability model to identify where additional populations/supporting habitat are located. | 2016 - 2018 |

| Conduct mark-recapture studies on Oregon Forestsnail. | A better understanding of snail home range, dispersal, source/sink habitat dynamics, etc. will facilitate more accurate estimates of the amount of habitat (in a patch) required for snail survival. | 2016 - 2018 |

| Develop habitat suitability model from data collected in habitat assessments (above). | An accurate habitat suitability model will support identification of critical habitat for the remainder of the Canadian population. | 2016 - 2018 |

| Survey candidate sites identified as Oregon Forestsnail habitat by the habitat suitability model. | Additional critical habitat identified. | 2017 - 2018 |

| Spatially define habitat polygons at all newly identified Oregon Forestsnail sites (identified through surveys and habitat suitability modelling) using established mapping techniques, plant community classification, coarse woody debris classification guidelines, information from mark–recapture studies, and other existing resources for describing habitat attributes. | This will complete the critical habitat identification. | 2016 - 2018 |

This section replaces the "Specific Human Activities Likely to Damage Survival/Recovery Habitat" (section 7.3) in the provincial recovery plan.

Understanding what constitutes destruction of critical habitat is necessary for the protection and management of critical habitat. Destruction is determined on a case by case basis. Destruction would result if part of the critical habitat were degraded, either permanently or temporarily, such that it would not serve its function when needed by the species. Destruction may result from a single or multiple activities at one point in time or from the cumulative effects of one or more activities over time.

Activities described in Table 2 include those likely to cause destruction of critical habitat for Oregon Forestsnail; destructive activities are not limited to those listed. Where a situation does not clearly fit in with the activities identified in Table 2, but has a potential impact on riparian habitat within identified critical habitat and/or water quality associated with waterways or wetlands that have a direct influence on identified critical habitat, the proponent should contact Environment Canada – Canadian Wildlife Service, Pacific and Yukon Region, for guidance on the activity.

| Description of Activity | Description of how activity would destroy critical habitat |

|---|---|

| Activities that change the hydrology of a site. Examples: Urban and commercial land development; land clearing; trail building. |

Changes to hydrology can alter the plant composition and moisture levels at a site, resulting in loss of all of the critical functions (cover, nesting/ aestivation/ mating/ oviposition substrate, and forage). |

| Excavating, contaminating, or compacting soil. Examples: Recreational activities such as mountain biking and all-terrain vehicle use within occupied habitats, excavating, herbicide application; trail building. |

Significant alterations to the soil can result in loss of suitable substrate for nesting and aestivation. It can also compromise growing conditions for preferred host plants, resulting in loss of mating and oviposition substrate and forage. Compaction/excavation can also increase the potential for flooding or drying of the nest site. |

| Removal of the tree/shrub/high forb canopy. Examples: Forest clearing, trail or road maintenance/construction. |

Removal of the canopy results in drying of the microclimate, altering the moisture regime required for maintenance of an Oregon Forestsnail population. It can also result in long term loss of coarse woody debris (aestivation and nesting substrate). |

| Removal of the understory. Examples: vegetation management activities including herbicide and other chemical applications, mowing, pruning, and brush burning. |

Removal of the understory leads to desiccation and/or reduced humidity at the site, altering the moisture regime required for maintenance of an Oregon Forestsnail population. It also eliminates the critical cover function. Removal of preferred host plants (e.g., Stinging Nettle) results in loss of mating and oviposition substrate and forage. |

| Removal of coarse woody debris. Examples: Hauling away or removing coarse woody debris; cutting downed wood into pieces; removing bark, or otherwise destroying coarse woody debris. |

Removal of coarse woody debris results in loss of suitable substrate for nesting and aestivation and has the potential to reduce microsite moisture. |

| Introduction of non-native plants into Oregon Forestsnail habitat. Examples: planting invasive ornamental species; dumping unwanted compost or vegetation. |

Some invasive plants can alter the understory moisture regime, potentially eliminating the moist conditions required for maintenance of an Oregon Forestsnail population. If they replace preferred host plants (e.g., Stinging Nettle), they may also cause loss of mating and oviposition substrate and forage. |

One or more action plans will be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry by 2021.

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is conducted on all SARA recovery planning documents, in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals. The purpose of a SEA is to incorporate environmental considerations into the development of public policies, plans, and program proposals to support environmentally sound decision-making.

Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that strategies may also inadvertently lead to environmental effects beyond the intended benefits. The planning process based on national guidelines directly incorporates consideration of all environmental effects, with a particular focus on possible impacts upon non-target species or habitats. The results of the SEA are incorporated directly into the strategy itself, but are also summarized below in this statement.

The following augments “Effects on Other Species” (section 9) in the provincial recovery plan:

Habitat requirements of Oregon Forestsnail overlap those of other SARA-listed species that occur in small streams adjacent to riparian/forest/edge Oregon Forestsnail habitat, or in the same moist forest habitat type as Oregon Forestsnail. These species include Pacific Water Shrew (Sorex bendirii), Salish Sucker (Catostomus catostomus ssp ), Nooksack Dace (Rhinichthys cataractae ssp.), Oregon Spotted Frog (Rana pretiosa), Coastal Giant Salamander (Dicamptodon tenebrosus), Coastal Tailed Frog (Ascaphus truei), Tall Bugbane (Cimicifuga elata), Streambank Lupine (Lupinus rivularis [PDF; 575 KB]), and Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae). As threats to these species are similar to the threats for Oregon Forestsnail (e.g., habitat loss, fragmentation, and degradation), recovery actions for all of these species are likely to be mutually beneficial.

- B.C. Conservation Data Centre. 2014. B.C. Species and Ecosystems Explorer. B.C. Ministry of Environment. Victoria, BC. [Accessed March 2012].

- Blackwell and Associates. 2003. Hope Innovative Forestry Practices Agreement (IFPA) Terrestrial Ecosystem Mapping with Wildlife Interpretations. [Accessed April 4, 2013]

- Durand, R. 2010. City of Abbotsford Sumas Mountain Sensitive Ecosystems Inventory. Prepared for the City of Abbotsford, Abbotsford, BC. 86 pp.

- Edworthy, A., K. Steensma, H. Zandberg, and P. Lilley. 2012. Dispersal, home range size and habitat use of an endangered land snail, the Oregon Forestsnail (Allogonal townsendiana). Can. J. Zool. 90(7):875–884.

- Kremsater, L. L. and F.L. Bunnell. 1999. Edges: Theory, evidence, and implications to management of western forests. Pp. 117-153 in J. A. Rochelle, L. A. Lehmann and J. Wisniewski (editors.) Forest Fragmentation: Wildlife and Management Implications. Brill, Leiden, Netherlands.

- Madrone Environmental Services Ltd. 2008. Terrestrial Ecosystem Mapping of the Coastal Douglas-Fir Biogeoclimatic Zone. Prepared for Government of British Columbia, Victoria, BC. 308 pp. [Accessed April 4, 2013]

- Madrone Environmental Services Ltd. 2006. Terrestrial Ecosystem Mapping: McKee Peak, Abbotsford, BC. Prepared for City of Abbotsford, Abbotsford, BC. 34 pp.

- Oregon Forestsnail Recovery Team. 2012. Recovery plan for Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in British Columbia. Prepared for the B.C. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC. 50 pp.

- Steensma, K.M.M., L.P. Lilley, and H.M. Zandberg. 2009. Life history and habitat requirements of the Oregon Forestsnail, Allogona townsendiana (Mollusca, Gastropoda, Pulmonata, Polygyridae), in a British Columbia population. Invert. Biol. 128:232–242.

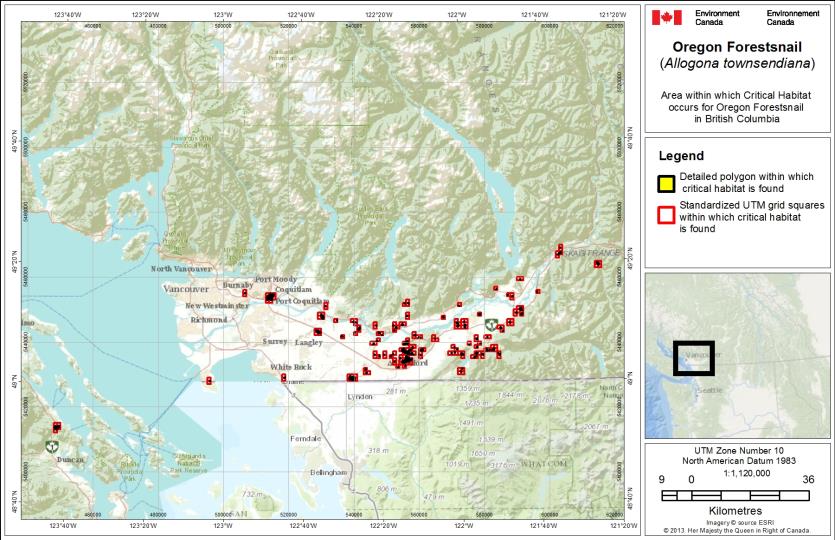

Long description for Figure 1

Figure 1 shows a map of southwestern British Columbia with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail. A few grid squares are located close to Duncan on Vancouver Island, as well as close to White Rock and Port Roberts on the mainland. The rest of the critical habitat locations are along the Fraser River, extending from Burnaby to Hope.

Long description for Figure 2

Figure 2 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in southern Vancouver Island, British Columbia. 6 grid squares are found in Westholme, on Vancouver Island.

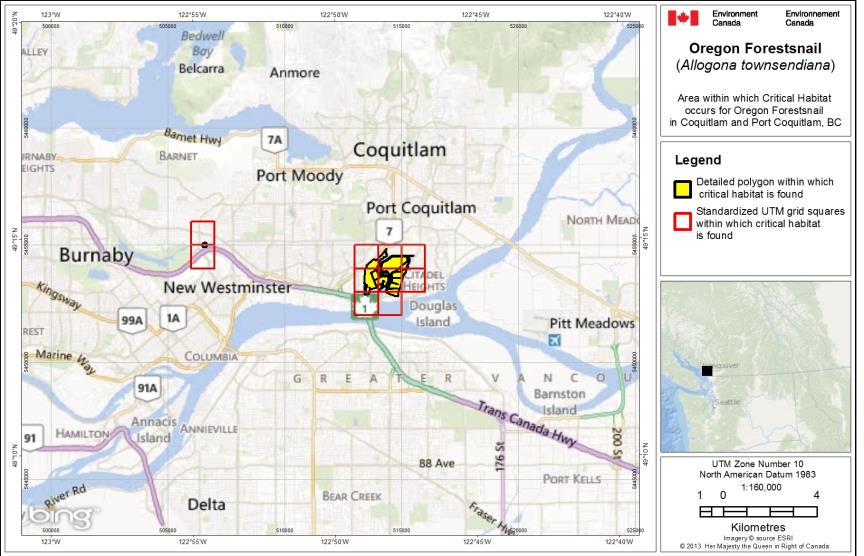

Long description for Figure 3

Figure 3 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in Coquitlam and Port Coquitlam, British Columbia. 2 grid squares are located close to the intersection of the Central Valley Greenway and the Trans Canada highway in Burnaby north to New Westminster. 8 grid squares are found close to the Fraser River and Citadel Heights in Port Coquitlam.

Long description for Figure 4

Figure 4 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in South delta, British Columbia. 2 grid squares exist north of Johnson Road in Point Roberts.

Long description for Figure 5

Figure 5 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in White Rock, British Columbia. 2 grid squares are located between 176 Street and the Vancouver-Blaine Highway just north of the United States border.

Long description for Figure 6

Figure 6 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in Aldergrove, British Columbia. 5 grid squares are located east of 264 Street just north of the United Stated border.

Long description for Figure 7

Figure 7 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in Maple Ridge and Langley, British Columbia. 2 grid squares are located east of Lougheed Highway and about north of Kanaka Creek in Maple Ridge. 4 grid squares are located north west of McMillan Island and covers some mainland. 1 grid square is by the Lougheed highway and in the Fraser River in south eastern Maple Ridge. 6 grid squares arranged longitudinally extend south from Glen Valley. 1 grid square is located west of 264 Street and north of the Trans Canada Highway in Langley. 4 grid squares are located close to Trans Canada Highway and Highway 10 in Langley.

Long description for Figure 8

Figure 8 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in Mission, British Columbia. 2 grid squares are located about north of the Mission Golf and Country Club. 2 grid squares are located west of the intersection of Highways 7 and 11. 1 grid square is located in southern of Matsqui Island, and 2 grid squares are located inland about southwest of the island north of Harris Road. 3 grid squares are located close to Durieu. 2 grid squares are located north west of Hatzic Lake. 6 grid squares extend west from south Hatzic Lake and along the Fraser River. 4 grid squares are located south of the Fraser River and about east of Ridgedale.

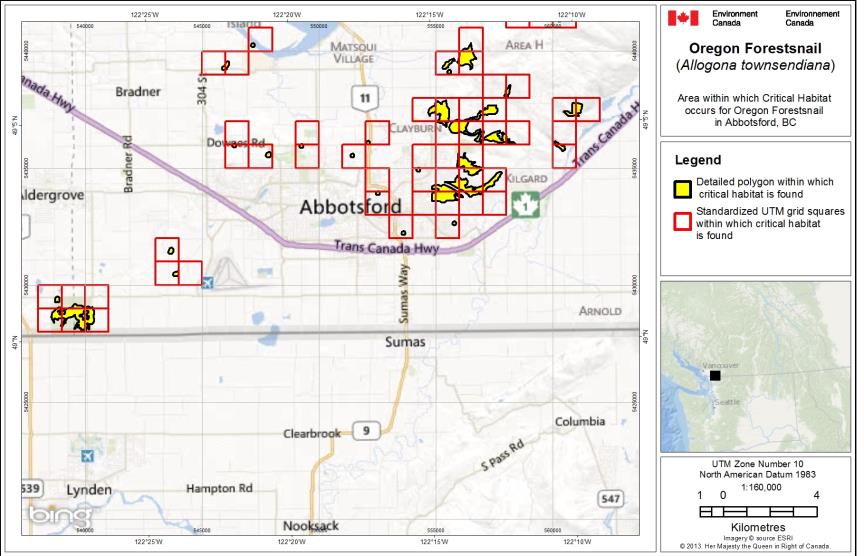

Long description for Figure 9

Figure 9 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in Abbotsford, British Columbia. 3 grid squares are located close to Downes Road east of 304 Street. Another 2 grid squares are located east of the latter described set of grid squares. 3 grid squares are located west of Abbotsford International Airport. 30 grid squares extend from close to Ridgedale south to the Trans Canada Highway and from close to highway 11 east to close to Kilgard. 4 grid squares are located east of the latter described set of grids close to the Trans Canada Highway.

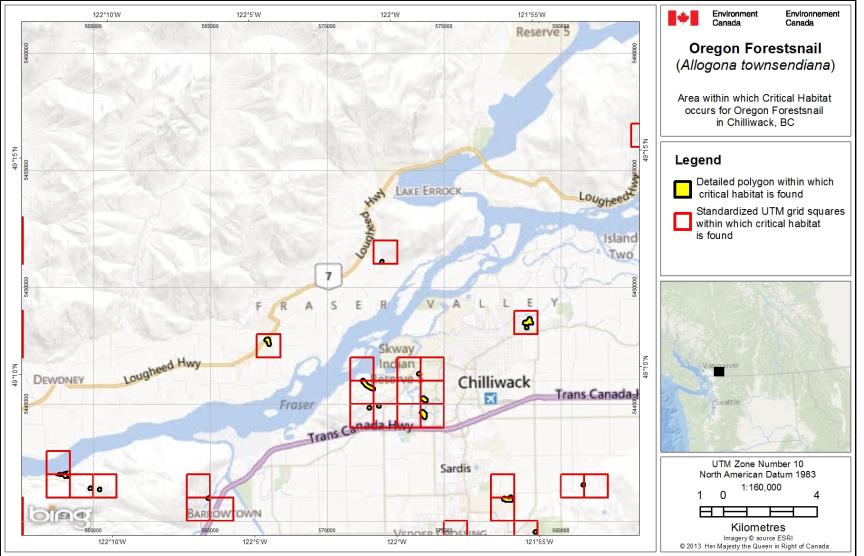

Long description for Figure 10

Figure 10 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in Chilliwack, British Columbia. 1 grid square is located far south of Lake Errock close to Lougheed Highway. Another grid square is located by Lougheed Highway south of Deroche. 11 grid squares are located within and south of the Skway Indian Reserve until the Trans Canada Highway. 1 grid square is located far west of the Meadowlands Golf and Country Club.

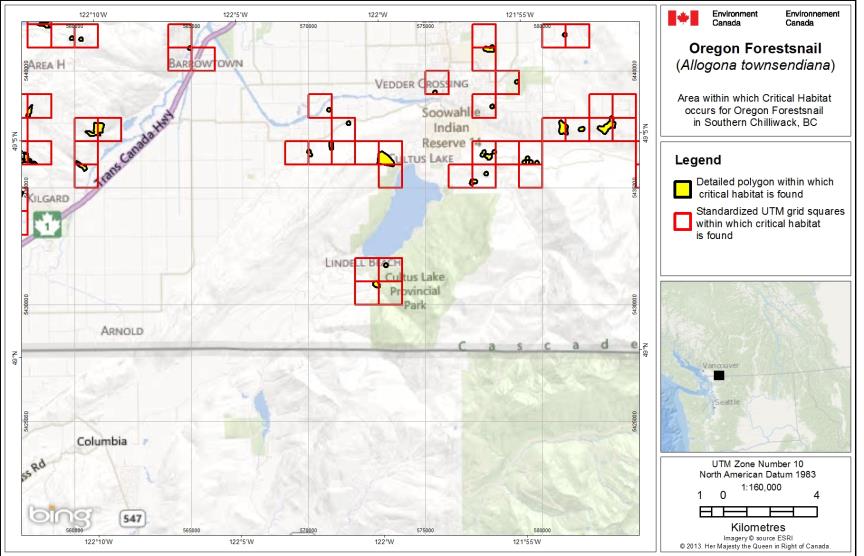

Long description for Figure 11

Figure 11 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in southern Chilliwack, British Columbia. 3 grid squares are located in Barrowtown. 8 grid squares are located north west of Cultus Lake. 4 grid squares are located south of Cultus Lake. 1 grid square and 4 grid squares are located north and north east of the Soowahlie Indian Reserve respectively. 12 grid squares arranged laterally extend east of the Soowahlie Indian Reserve. 2 grid squares are located in about north east of Sardis.

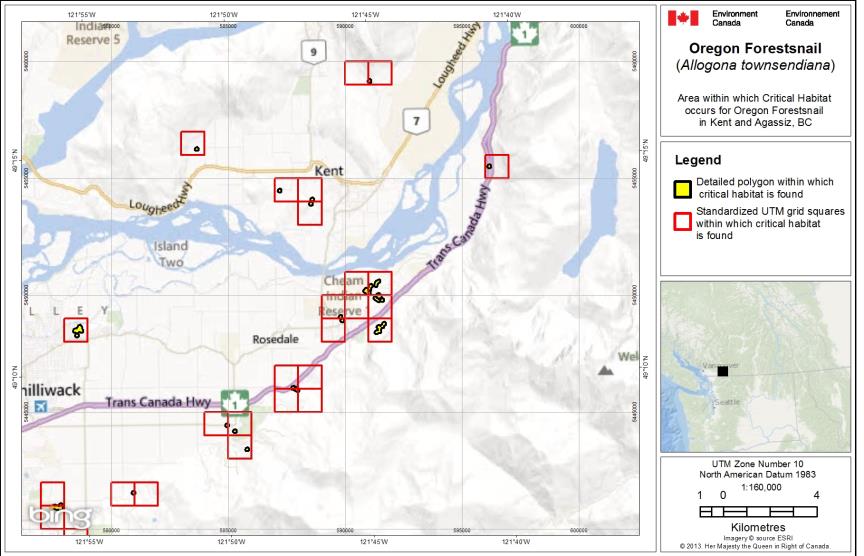

Long description for Figure 12

Figure 12 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in Kent and Agassiz, British Columbia. 1 grid square and 2 grid squares are located north and far north of the Lougheed Highway, and 3 grid squares just south of the highway in Kent. 7 grid squares are located within the Cheam Indian Reserve. 4 grid squares are located in southern Rosedale at the Trans Canada Highway and 3 grid squares are located south of highway south of Rosedale. 1 grid square is located on the Trans Canada Highway east of Herrling Island.

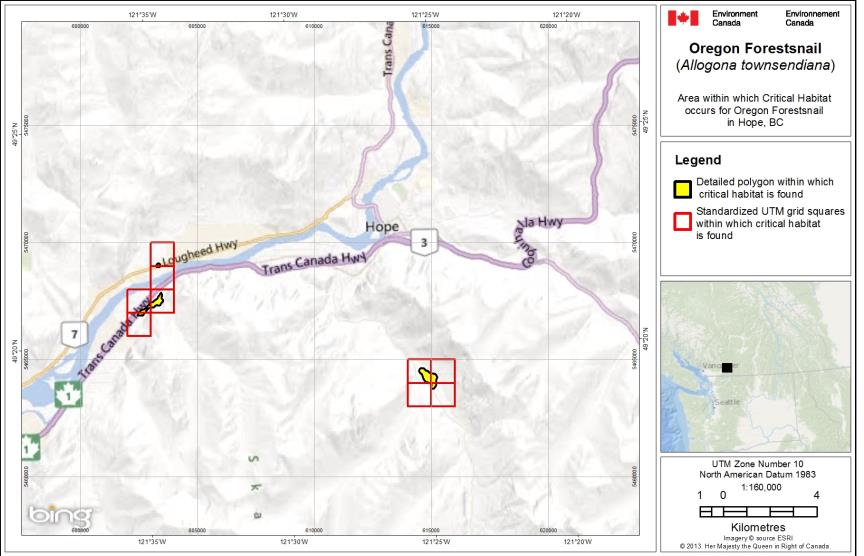

Long description for Figure 13

Figure 13 represents a map with standardized 1 × 1 km grid squares of the area that contain critical habitat for the Oregon Forestsnail in Hope, British Columbia. 5 grid squares extend vertically between Lougheed Highway and the Trans Canada Highway about midway between Floods and Laidlaw. 4 grid squares are located far south of the Trans Canada Highway 3.

Prepared by the Oregon Forestsnail Recovery Team

October 2012

- Recovery Team Members

- Acknowledgements

- Executive Summary

- Recovery Feasibility Summary

- 1. COSEWIC* Species Assessment Information

- 2. Species Status Information

- 3. Species Information

- 4. Threats

- 5. Recovery Goal and Objectives

- 6. Approaches to Meet Objectives

- 7. Information on Habitat to Meet Recovery Goal

- 8. Measuring Progress

- 9. Effects on Other Species

- 10. References

- Appendix 1. Oregon Forestsnail Sites and Land Tenure

- Appendix 2. Threats Applicable to Each Site

- Appendix 3. Gastropod Surveys

- Table 1. Threat classification table for Oregon Forestsnail.

- Table 2. Recovery planning table for Oregon Forestsnail.

- Table 3. Studies needed to describe survival/recovery habitat to meet the recovery goal for Oregon Forestsnail.

- Table 4. Specific human activities likely to damage survival/recovery habitat for Oregon Forestsnail.

- Figure 1. Oregon Forestsnail adult showing topside (left), underside (centre), and underside of the shell showing the white apertural lip (right), June 11, 2010, Colony Farms – Metro Vancouver Regional Park. Photographs by J. Heron.

- Figure 2. Global range of Oregon Forestsnail, based on Pilsbry (1940, Figure 508) and B.C. records (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

- Figure 3. B.C. Oregon Forestsnail sites from 1901 to 2011 (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

Recovery Plan for Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in British Columbia

Prepared by the Oregon Forestsnail Recovery Team

October 2012

This series presents the recovery strategies that are prepared as advice to the Province of British Columbia on the general strategic approach required to recover species at risk. The Province prepares recovery strategies to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada, and the Canada – British Columbia Agreement on Species at Risk.

Species at risk recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species' persistence in the wild.

A recovery plan summarizes the best available science-based knowledge of a species or ecosystem to identify goals, objectives, and strategic approaches that provide a coordinated direction for recovery. These documents outline what is and what is not known about a species or ecosystem, identify threats to the species or ecosystem, and explain what should be done to mitigate those threats. When sufficient information to guide implementation for the species can be included, the document is referred to as a recovery plan, and a separate action plan is not required.

To learn more about species at risk recovery in British Columbia, please visit the Ministry of Environment Recovery Planning webpage.

Oregon Forestsnail Recovery Team. 2012. Recovery plan for Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in British Columbia. Prepared for the B. C. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC 50 pp.

Heron, Jennifer

Additional copies can be downloaded from the B.C. Ministry of Environment Recovery Planning webpage.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Oregon Forestsnail Recovery Team (Canada)

Recovery plan for Oregon forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) in

British Columbia [electronic resource] / prepared by the Oregon Forestsnail

Recovery Team.

(British Columbia recovery strategy series)

Includes bibliographical references.

Electronic monograph in PDF format.

ISBN: 978-0-7726-6607-9

1. Polygyridae-Conservation-British Columbia. 2. Rare invertebrates-

British Columbia. I. British Columbia. Ministry of Environment II. Title. III. Series: British Columbia recovery strategy series

QL430.5 P6 O73 2012

333.95'5716

C2012-980180-1

This recovery plan has been prepared by the Oregon Forestsnail Recovery Team, as advice to the responsible jurisdictions and organizations that may be involved in recovering the species. The British Columbia Ministry of Environment has received this advice as part of fulfilling their commitments under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada, and the Canada - British Columbia Agreement on Species at Risk.

This document identifies the recovery strategies that are deemed necessary, based on the best available scientific and traditional information, to recover Oregon Forestsnail populations in British Columbia. Recovery actions to achieve the goals and objectives identified herein are subject to the priorities and budgetary constraints of participatory agencies and organizations. These goals, objectives, and recovery approaches may be modified in the future to accommodate new objectives and findings.

The responsible jurisdictions and all members of the recovery team have had an opportunity to review this document. However, this document does not necessarily represent the official positions of the agencies or the personal views of all individuals on the recovery team.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that may be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy. The Ministry of Environment encourages all British Columbians to participate in the recovery of Oregon Forestsnail.

- Jennifer Heron (Chair), Ministry of Environment, Vancouver

- Claudio Bianchini, Bianchini Biological Services, Delta

- Trudy Chatwin, Ministry of Forests, Lands and Resource Operations, Nanaimo

- Gord Gadsden, Fraser Valley Regional District, Chilliwack

- Megan Harrison, Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Delta

- Joanna Hirner, BC Parks, Ministry of Environment, North Vancouver

- Suzie Lavallee, University of British Columbia, Vancouver

- Patrick Lilley, Raincoast Applied Ecology, Vancouver

- Joshua Malt, Ministry of Forests, Lands and Resource Operations, Surrey

- Angela Manweiler, National Defence ASU, Chilliwack

- Kristiina Ovaska, Biolinx Environmental Research Ltd., Sidney

- Kristina Robbins, Ministry of Forests, Lands and Resource Operations, Surrey

- Lennart Sopuck, Biolinx Environmental Research, North Saanich

- Karen Steensma, Trinity Western University, Langley

- Andrea Tanaka, Canadian Wildlife Service, Environment Canada, Delta

- Kym Welstead, Ministry of Forests, Lands and Resource Operations, Surrey

- Mike Younie, District Municipality of Mission, Mission

Jennifer Heron completed this final version of the recovery plan. Leah Westereng (Ministry of Environment [MoE]) provided extensive review and input into the plan. Scientific advice, review, and revisions have been the collaborative efforts of the Oregon Forestsnail Recovery Team. This recovery plan started a number of years ago and has been updated many times over the past years. Thank you to Kristiina Ovaska and Lennart Sopuck of Biolinx Environmental Research Ltd., Robert Forsyth (private malacologist), Tom Burke (private malacologist), and Terry Frest (private malacologist). The past and ongoing research by Trinity Western University, Karen Steensma, and involving Sooze Waldock, Heather Zandberg, Patrick Lilley, Martyna Kus, Martin Rekers, Deanna Leigh, Amanda Edworthy, Marie DenHaan, Jordan Thiessen, Stephanie Koole, and Melissa Oakes has contributed much to answering some of the knowledge gaps of Oregon Forestsnail. Thank you to Dwayne Lepitzki and Gerry Mackie (co-chairs, Mollusc Specialist Subcommittee, Committee on the Endangered Wildlife in Canada) and Dave Fraser (MoE) for input on the threats and Byron Woods (MoE) for mapping support. Thank you to all the biologists and private citizens who submit data on Oregon Forestsnail.

Additional reviews of the recovery plan were completed by Patrick Daigle (MoE [retired]), Jenny Feick (with MoE at the time), Brenda Costanzo (MoE), Ted Lea (MoE [retired]), Jeff Brown, (with MoE at the time), Laura Darling (MoE), Lucy Reiss (Environment Canada-Canadian Wildlife Service [EC-CWS]), Wendy Dunford (EC-CWS), Lucie Metras (EC-CWS), and Trish Hayes (EC-CWS).

Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) was designated as Endangered by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) because the species is restricted to a very small area of the southwestern British Columbia (B.C.) mainland and southern Vancouver Island. Populations are severely fragmented with continuing declines observed in extent of occurrence and quality of habitat due mainly to urban development. It is listed as Endangered in Canada on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). In B.C., Oregon Forestsnail is ranked S2 (Endangered) by the Conservation Data Centre and is on the provincial Red list. The B.C. Conservation Framework ranks Oregon Forestsnail as a priority 1 under goal 3 (maintain the diversity of native species and ecosystems). Recovery is considered to be biologically and technically feasible.

Oregon Forestsnail is a large, hermaphroditic land snail endemic to western North America. The shell of mature individuals is pale brown or straw yellow, round and flattened in form, and ranges from 28 to 35 mm in diameter. The Oregon Forestsnail in Canada is at the northern limits of its geographical range, and consequently may possess unique adaptations.

Oregon Forestsnail occupies mixedwood and deciduous forest habitat, typically dominated by bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa), and scattered western redcedar (Thuja plicata). Many records are from riparian habitats and forest edges, where dense cover of low herbaceous native vegetation is typically present. The presence of Oregon Forestsnail is correlated with the presence of stinging nettle (Urtica dioica). All known Canadian Oregon Forestsnail populations are from habitats lower than 360 m above sea level.

Major threats include residential and commercial development; recreational activities; and invasive non-native/alien species. The population and distribution goal is to maintain current (and new) populations and supporting habitat for Oregon Forestsnail throughout the species' natural range and distribution in British Columbia.

The recovery objectives for Oregon Forestsnail are:

- To identify and prioritize important Oregon Forestsnail habitat throughout the species' range in B.C.

- To secure protectionFootnote1 for Oregon Forestsnail habitats within the species' range.

- To assess and reduce threats at all known sites in B.C.

- To address knowledge gaps (e.g., population ecology, habitat associations, dispersal) that currently prevent quantitative population and distribution objectives from being established.

The recovery of Oregon Forestsnail in B.C. is considered biologically and technically feasible based on the criteria outlined by the Government of Canada (2009):

- Individuals of the wildlife species that are capable of reproduction are available now or in the foreseeable future to sustain the population or improve its abundance.

Yes. The persistence of Oregon Forestsnail populations for at least 10 years at 12 or more sites, combined with the known presence of juveniles/eggs at some sites, indicates that individuals capable of reproduction are available. - Sufficient suitable habitat is available to support the species or could be made available through habitat management or restoration.

Yes. Oregon Forestsnail persists in small habitat patches, at least for the short term, and additional localities likely exist within both small (< 1 ha) and larger habitats. The larger-scale patches of suitable habitat for Oregon Forestsnail are located on Sumas Mountain, Chilliwack Mountain, and the areas on the south side of the Fraser River from Langley east to Bridal Veil Falls Provincial Park near Hope. Restoration may be necessary at sites where there has been extensive disturbance and development, and some landowners may want to restore habitats that have already been modified by urban or agricultural practices. For example, potential measures include providing cover for the snails around seepages and other moist habitats, increasing the density of stinging nettle, and restoring habitat connectivity along creeks and waterways. - The primary threats to the species or its habitat (including threats outside Canada) can be avoided or mitigated.

Yes. It is possible to mitigate some of the threat to its habitat from new urban and agricultural developments by protecting core habitats of moist mixedwood forests and leaving forested buffers around such areas. Threats from introduced species may be more difficult to address, although site-specific removal of introduced species is possible. Threats such as fire and flooding may also be minimized at some sites. Managing recreational activities to minimize soil compaction at some sites is also possible and may aid in protecting snail habitat. - Recovery techniques exist to achieve the population and distribution objectives or can be expected to be developed within a reasonable timeframe.

Yes. Techniques used to recover this species are similar to recovery planning techniques applied to species with similar threats and requirements. Examples of recovery techniques include habitat protection, removal of site-specific threats (such as introduced species), and working with land managers and landowners to develop site-specific best management practices guidelines.

Date of Assessment: November 2002

Common Name (population): Oregon Forestsnail

Scientific Name: Allogona townsendiana

COSEWIC Status: Endangered

Reason for Designation: The species is restricted to a very small area of the extreme southwestern British Columbia mainland and southern Vancouver Island. Populations are severely fragmented with continuing declines observed in extent of occurrence, area of occupancy and area, extent and quality of habitat due mainly to urban development. Even though there may be other locations, the species is still very uncommon.

Canadian Occurrence: British Columbia

COSEWIC Status History: Designated Endangered in November 2002. Assessment based on a new status report. Currently undergoing ten year assessment and will be re-assessed by COSEWIC November 2012.

Oregon ForestsnailFootnotea

Oregon Forestsnail (Allogona townsendiana) is a large hermaphroditic land snail (adult shell diameter 28–35 mm) endemic to western North America (Figure 1). Snail shell colour varies, ranging from amber to light reddish brown to straw yellow, with white lines running across each segment of the spiral. The shell shape is round and slightly flattened. Adult shells typically have from 5.25 to 6 whorls with fine, wavy spiral striae and irregular, light-coloured, wrinkle-like axial riblets and an overall irregular dimpled sculpture (Pilsbry 1940). As the snail ages the outer periostracal layer (outer surface of shell) flakes, becomes bleached and the fine spiral striae are no longer evident. Fine hair-like structures are not present on Oregon Forestsnail. The main distinguishing feature of Oregon Forestsnail adults is a distinct whitish apertural "lip" or rim at the shell opening, which is thickened, and strongly flared, outward. There is no denticle within the aperture.

Long description for Figure 1

Figure 1 represents 3 photographic images of an adult Oregon Forestsnail. The first photograph shows the topside of the snail with the reddish brown to straw yellow round and slightly flattened shell. The shell has white lines running across each segment of the spiral. The shell typically has from 5.25 to 6 whorls. The second image shows the underside of the snail. The third image shows the underside of the shell of the snail, with a whitish apertural “lip” or rim at the shell opening, which is thickened and strongly flared outward and has no denticle within it.

Oregon Forestsnail eggs are round, globose, opaque and grayish-white, slightly flattened, and with a grainy texture (COSEWIC 2002; Forsyth 2004; Steensma et al. 2009). Eggs are laid singly or in clusters with an average clutch size of 34 eggs in captivity (Steensma et al. 2009). Average egg diameter of captivity laid eggs was 3.1 mm.

Adult and juvenile Oregon Forestsnails are similar in appearance, although juvenile snails have thinner, transparent shells, particularly towards the outermost whorl, and no bleaching of shell colour. Juveniles generally do not have a thickened apertural lip.

Oregon Forestsnail is not likely to be confused with other landsnails within its B.C. range with the exception of Pacific Sideband (Monadenia fidelis). However, the Pacific Side-band does not have a white, thickened apertural lip and when multiple specimens are compared, the overall size of Pacific Sideband is greater than Oregon Forestsnail. Morphological comparisons with other similar land snails found within the global geographic range of Oregon Forestsnail are detailed in the COSEWIC (2002) status report.

The life cycle of Oregon Forestsnail appears closely tied to seasonal temperature, day length, humidity, and climate conditions within the habitat patch it occupies. In general, snail activity levels depend on a combination of day length, moisture, and temperature (Solem and Christensen 1984; Prior 1985). A recent Oregon Forestsnail study assessed population size, reproductive timing and habitats, seasonal behaviors, and juvenile activity over a four-year period at Trinity Western University Ecological Study Area (TWU-ESA) in Langley, B.C. (Steensma et al. 2009). This study provides most of the information summarized below.

3.2.1 Seasonal Activity

Fifteen Oregon Forestsnail individuals were tracked by harmonic detection finder to follow their seasonal pattern over two years (see Steensma et al. 2009). In general, mating begins as early as February, lasting through early June. As the warmer and drier summer months approach, snails seek shelter deep within litter, under logs or the bark of coarse woody debris, or in similar shelter places within the deciduous forests where they predominantly live (see Section 3.3). This aestivation period lasts several weeks and in mid to late September the species becomes active again for the wet fall months. Once the first frost occurs, the individuals enter hibernation until the following spring. Winter hibernation begins sometime in late October to late November and lasts until late February, when temperatures are below 10.6°C, and often drop to freezing overnight (Steensma et al.2009).

During hibernation Oregon Forestsnails seek shelter by burying themselves 2–7 cm within leaf litter, moss, soil, or other forms of cover; they form an ephiphragm and orient themselves with the aperture of the shell upwards (Steensma et al. 2009). Adult snails are not likely to move during the hibernation period, although five tracked adults moved (average distance 14 cm) during the hibernation period, and may have fed during this time (Steensma et al. 2009). Juveniles have been observed at one site during hibernation months (Hawkes and Gatten 2011; Edworthy et al. 2012).

3.2.2 Mating

Oregon Forestsnail is hermaphroditic but it is unlikely that self-fertilization occurs (this could decrease fitness as has been seen in other gastropods) (Forsyth 2004). Like most native gastropods in southwestern B.C., this species is most active during the wet spring months when mating takes place. Oregon Forestsnail mating pairs have been observed at three sites in B.C., showing snails are active beginning in early February with the peak mating period from early March through early May (Steensma et al. 2009), and as late as June (Kus 2005).

Prior to mating, Oregon Forestsnail aggregates in clusters of 8–14 snails and shows social behaviour of antennal and shell touching. Numerous gastropod species exhibit group aggregations, or huddles: groups of slugs aggregate together to prevent water loss (Cook 1981a, 1981b; Prior 1981, 1985; Prior et al. 1983). Huddles create a high humidity microenvironment and reduce dehydration. Oregon Forestsnail mating has been observed to occur directly on or within proximity (< 3 m) of coarse woody debris (e.g., logs). Stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) also grew < 1 m from mating pairs, as observed at three out of four pairs at TWU-ESA (Steensma et al. 2009). Mating first occurred when day length was greater than 11 hours, was with one individual, and was observed to last 225–229 minutes (Steensma et al. 2009).

3.2.3 Nesting

Oregon Forestsnail nesting in B.C. has been observed from April 20 to June 20, peaking in mid-May, and has been found near the edge or interior of forest habitats (Steensma et al. 2009). Oregon Forestsnail nesting and egg-laying are documented from three different sites in B.C.: Cemetary Hill, Nicomekel Slough, and TWU-ESA (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012). At the TWU-ESA, 53 nests were surveyed over a two-year period with adult snails digging a 6–10 cm flask-shaped hole, the equivalent of their body size, with their foot. Oviposition occurs after adult Oregon Forestsnails dig or burrow into new or existing nesting holes (Steensma et al. 2009). Most snails dig new nests although some nested within pre-existing depressions in soil, in moss, and under coarse woody debris (Steensma et al. 2009). Snails have also been observed ovipositing at the base of vegetation, such as Creeping Buttercup (Ranunculus repens), and occasionally within the same burrow as another snail and within gravel substrate (Edworthy et al.2012).

3.2.4 Hatching and Juveniles

Juvenile snails hatched approximately 8–9 weeks after oviposition (Steensma et al. 2009). Asynchronous hatching has been observed. Juveniles began dispersing from the nest site within hours of hatching. Following hatching, snail activity included climbing < 1 m on tall vegetation close to the nest. Vegetation favoured by juvenile Oregon Forestsnail individuals included stinging nettle, reed canarygrass (Phalaris arundinacea), Indian-plum (Oemleria cerasiformis), and Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera). Older juveniles (not hatchlings) were observed feeding on stinging nettle (Steensma et al. 2009).

3.2.5 Adult Maturation

Adults likely reach reproductive maturity by two years and have a life span of at least five (Steensma et al. 2009) to eight years (COSEWIC 2002). This results in an estimated generation time of two to five years.

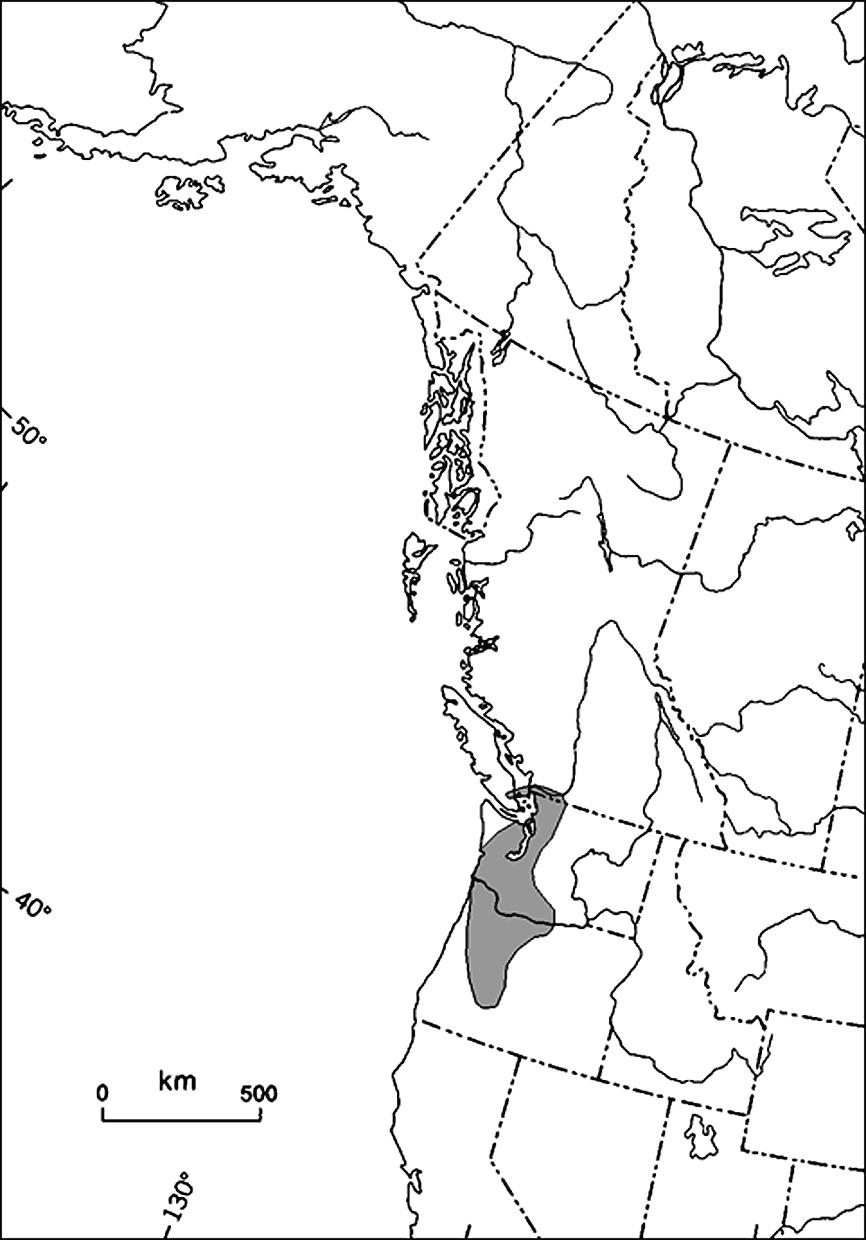

The global range of Oregon Forestsnail is entirely within western North America (Figure 2). The northernmost extent of its range is in southwestern B.C. The range extends south through the Puget Trough in Washington State and to the Willamette Valley in west-central Oregon. The easternmost records are from west of Hope, B.C., south-central Washington, and north-central Oregon in the Columbia River Valley. Based on recent records (within the past 10 years) and the historic records (combined), the global range extent is estimated at 135,000 km².

Long description for Figure 2

Figure 2 represents a map of the global range of the Oregon Forestsnail in North America. The range extends along the western edge of North America and stretches south from south western British Columbia through the Puget Trough in Washington State and to the Willamette Valley in west-central Oregon. The easternmost records are from west of Hope, British Columbia, south-central Washington, and north-central Oregon in the Columbia River Valley.

The Canadian range of Oregon Forestsnail is restricted to B.C. within the coastal lowlands of the Lower Fraser Valley and one record on southeastern Vancouver Island (Figure 3; Appendix 1). Within the Lower Fraser Valley the most northeastern record is from near Hope, and the most western record is in Tsawwassen, with records throughout the Lower Fraser Valley within the municipal areas of Chilliwack, Mission, Abbotsford, Langley, Burnaby, Surrey, and Delta. On Vancouver Island, Oregon Forestsnail is known from the community of Westholme near Duncan (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012). There are no known records on the Gulf Islands. All records are from elevations lower than 360 m above sea level.

Long description for Figure 3

Figure 3 represents a map of the Oregon Forestsnail occurrence sites from 1901 to 2011 in British Columbia. On Vancouver Island, occurrences have been recorded in North Cowichan near Duncan. The rest of the occurrences are within the coastal lowlands of the Lower Fraser Valley from Tsawwassen to Hope, with recordings in municipal areas of Chilliwack, Mission, Abbotsford, Langley, Burnaby, Surrey, and Delta.

Oregon Forestsnail records in B.C. date from 1901 to 2011 (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012). Based on recent records (within the past 10 years) and the historic records (combined), the range extent for B.C. is 3313 km² (including the unsuitable salt-water Strait of Georgia, between Vancouver Island and the Lower Fraser Valley). The occurrence on Vancouver Island is < 1 km². Oregon Forestsnail extent of occurrence based on recent records only (since year 2000) is similar to the known historic extent of occurrence.

As of August 2011 there are 67 known sitesFootnote3 (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012). The biological area of occupancy calculated by summing the area of all sites is approximately 670 ha (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

Based on habitat assessments on Vancouver Island, it is possible that Oregon Forestsnail may occur within the lower elevation wet valley bottoms on the eastern side of the island (approximately 100 km north and south of the community of Westholme) although extensive search effort within these areas has yet to reveal any new sites (see Appendix 2).

The presence of Oregon Forestsnail shells is often used as an indicator of site occupancy by live individuals because: (1) shells are concentrated sources of calcium and as such likely are consumed or disintegrate in short amounts of time (i.e., if the shell is present, the snail has not been dead long); (2) Oregon Forestsnail is reported incidentally during other wildlife surveys and not during the ideal survey window (i.e., snails may be hibernating or aestivating), and a shell would likely be visible on the litter surface (in the open) as opposed to a live individual that would likely take cover; and (3) specific Oregon Forestsnail surveys are often not completed during optimal activity periods.

Surveys for Oregon Forestsnail have primarily been by wandering transects through suitable habitat with the main objective to record snail presence, abundance, and habitat information (Appendix 2). Wandering transects follow no pre-determined grid or fixed route and allow the surveyor to change course depending on habitat suitability. Transect routes are usually tracked using a handheld Global Positioning System (GPS) unit to quantify search effort. This methodology has not allowed for population sizes or trends, mostly because sites are not revisited. No baseline information exists on historical abundance of Oregon Forestsnail, making estimates of population trends not possible.

At the most studied population of Oregon Forestsnail in B.C. (TWU-ESA), population estimates among four study areas within this population ranged from 7 to 47 snails with an overall mean density of 1.0 snail/m² (Steensma et al. 2009). At another Oregon Forestsnail population (Chilliwack), the estimated density of Oregon Forestsnail was highest in riparian habitats (0.14 snail/m²) and second-growth mixed deciduous forests (0.13 snail/m²) (Hawkes and Gatten 2011). These data were not gathered in the breeding season, which is considered ideal timing; however, they were collected in the wet fall when snails are known to be active and visible. Until a survey is completed in the spring, the Chilliwack results should be treated with uncertainty.

There are insufficient data to provide an accurate abundance of Oregon Forestsnail across the entire species' range in B.C. However, Oregon Forestsnail sites mapped by the B.C. Conservation Data Centre (2012) and information gathered during the preparation of this document provide some information on Oregon Forestsnail abundance. Oregon Forestsnail site abundance information ranges from one individual (at least 17 sites) to abundance counts > 20 snails (9 sites). The greatest number of snails recorded in a single survey was > 670 individuals at Colony Farms – Metro Vancouver Regional Park (Parkinson and Heron 2010).

There is minimal information on population fluctuation and trends for Oregon Forestsnail. Natural population fluctuations for snails are likely the result of numerous abiotic factors including moisture levels, weather patterns, and seasonal temperature fluctuations (such as early season frost) or erratic flooding. Biotic factors contributing to population fluctuations include parasites, predators, available minerals, and nutrients for healthy shell growth (e.g., through the consumption of plants such as stinging nettle), and availability of substrate within which to take refuge and/or lay eggs.

Although population trend data have not been collected for Oregon Forestsnail, associated Oregon Forestsnail habitat has shown a decline, particularly in the past 10 years. Urban and agricultural land development throughout the Lower Fraser Valley and southeastern Vancouver Island has removed forested habitat, reduced wetland cover, and resulted in a loss of streams. As such, it is likely that historically Oregon Forestsnail exhibited a more extensive metapopulation structure within suitable habitats throughout its known range in southwestern B.C.

3.4.1 Habitat and Biological Needs

Oregon Forestsnail habitat requirements appear to be closely linked to the abiotic and biotic factors that limit an individual's physiological stress: minimizing dehydration; optimizing osmotic uptake of minerals through the integument (whether beneficial [e.g., water, calcium] or harmful [e.g., pesticides, chemicals]); and the amount of available consumptive mineral content (e.g., food) necessary for healthy shell growth. Abiotic factors that limit moisture, such as temperature, water availability, and day length, contribute to the overall activity patterns of gastropods and their presence within a habitat patch. Biotic factors such as coarse woody debris and understory vegetation allow for the moisture retention and high relative humidity (numerous studies summarized in Prior 1985; Steensma et al. 2009). Moisture and microhabitat features, including soil organic matter content and friability, coarse woody debris, understory vegetation, and bryophyte layers, define snail activity and reproductive success, foraging, and persistence within a habitat patch (Prior 1985). Information used to describe Oregon Forestsnail habitat in B.C. includes the collective efforts of occurrence records with the B.C. Conservation Data Centre (2012).

General description

- Low elevation (30–360 m above sea level)

- Deciduous and mixedwood broad-leaf forests with sustained high moisture, relative humidity, and multi-structured microhabitat that maintains high moisture levels.

- Riparian areas and landscape attributes with high site index (forest growth productivity) including ravines, gullies, and depressions containing both permanent and ephemeral watercourses; the wooded edges of streams, marshes, seasonally flooded and wet lowland areas; and similar habitats (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

- Forest interfaces and edge habitats where moisture is retained (Waldock 2002).

Forest overstory composition

- Typical habitat includes deciduous and mixedwood species with dominant overstory composition > 40% (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

- Forest stand ages range from 20 to >80 years (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

- Overstory composition includes large bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum), black cottonwood (Populus trichocarpa), and scattered western redcedar (Thuja plicata).

- Additional trees present include paper birch (Betula papyrifera), trembling aspen (Populus tremuloides), red alder (Alnus rubra), and grand fir (Abies grandis) (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

Dominant shrub species composition

- Oregon Forestsnail tends to inhabit areas with dense shrub vegetation that functions to minimize moisture and evaporative loss from this vegetative layer. In riparian areas, the dense vegetation may be less than other less moist areas.

- Oregon Forestsnail habitats have variable native shrub species composition including a suite of the following species: devil's club (Oplopanax horridus), elderberry (Sambucus racemosa), false azalea (Menziesia ferruginea), beaked hazelnut (Corylus cornuta), Indian-plum (Oemleria cerasiformis), oceanspray (Holodiscus discolor), red-osier dogwood (Cornus stolonifera), rose (Rosa sp.), salmonberry (Rubus spectabilis), salal (Gaultheria shallon), saskatoon (Amelanchier alnifolia), common snowberry (Symphoricarpos albus), thimbleberry (Rubus parviflorus), and vine maple (Acer circinatum) (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

Herbaceous plant composition

- Oregon Forestsnail inhabits areas with dense herbaceous plant cover consisting of live and senescent vegetation, which provide food and cover during all life stages. Snails are often found at the base of large vegetation clumps or plants (e.g., leaf litter at the base of trees, shrubs, and ferns).

- Herbaceous composition includes bedstraw (Galium sp.), bleeding heart (Dicentra formosa), buttercup (Ranunculus sp.), cow parsnip (Heracleum maxiumum), enchanter's nightshade (Circaea alpina), false lily-of-the-valley (Maianthemum dilatatum), foamflower (Tiarella trifoliata), fringecup (Tellima grandiflora), Cooley's hedge nettle (Stachys chamissonis var. cooleyae), horsetail (Equisetum sp.), miner's lettuce (Claytonia sp.), pathfinder (Adenocaulon bicolor), skunk cabbage (Lysichiton americanum), starflower (Trientalis sp.), stinging nettle, thistle (Cirsium sp.), tiger lily (Lilium columbianum), trillium (Trillium ovatum var. ovatum), twistedstalk (Streptopus sp.), vanilla leaf (Achlys triphylla), waterleaf (Hydrophyllum sp.), and creeping buttercup (Ranunculus repens) (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

- Ferns commonly recorded within Oregon Forestsnail habitat include bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum), ladyfern (Athyrium filix-femina), northern maidenhair fern (Adiantum aleuticum), and swordfern (Polystichum munitum) (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

Presence of stinging nettle within the habitat patch

- Most habitats of Oregon Forestsnail contain patches of stinging nettle (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012; Edworthy et al. 2012). Stinging nettle appears to have high importance to Oregon Forestsnail populations especially for mating and egg-laying (COSEWIC 2002; Waldock 2002; Steensma et al. 2009). The daily consumption of stinging nettle is likely needed for healthy shell growth, as the plant contains high levels of calcium and other essential minerals needed to maintain shell durability. Stinging nettle is of significant importance to other land snails (Iglesias and Castillejo 1998). Waldock (2002) examined the association of Oregon Forestsnail with the stinging nettle in detail at TWU-ESA in Langley, and found a positive correlation between the abundance of the snails and stinging nettle. The presence of stinging nettle indicates moist, rich soils with high amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus (Pojar and MacKinnon 1994).

- There are two species of stinging nettle within B.C.: Urtica dioica is native to B.C. and Urtica gracilis is non-native. It is unknown if Oregon Forestsnail exhibits a preference or obligate association with one or both of these stinging nettle species.

Soil characteristics

- Rich, mesic and soft, productive, moist, well-developed mull-typeFootnote4 litter layer soils are important habitat requirements at all life stages (Cameron 1986; COSEWIC 2002; Steensma et al. 2009; B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

- Litter depth (leaf needle) is typically 5–10 cm (Durand, pers. comm., 2012) and often greater than 15 cm in depth. This deep litter layer provides shelter, hibernation, and aestivation sites (Steensma et al. 2009; B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

- Soil pH was recorded at 6.4–6.9 from one site in Langley (Steensma et al. 2009).

- Soil temperature was recorded at 9.9–13°C from one site in Langley (Steensma et al. 2009).

Coarse woody debris

- Oregon Forestsnail is recorded from habitats with abundant coarse woody debris.

- Coarse woody debris is of various stages of decay.

- Size ranges from large-diameter pieces to a forest floor composed of thin, compact needle litter.

- Coarse woody debris is an important habitat attribute for Oregon Forestsnail activity: mating, nesting, aestivation, hibernation, and egg laying (Steensma et al. 2009) and offers protection against daily or seasonal variations in temperature and water availability (as summarized in Prior 1985; Steensma et al. 2009).

- Decaying logs retain moisture and allow for the growth of a thick and healthy moss layer, which provide essential shelter during warm and dry weather conditions. It is important for Oregon Forestsnail to have a suitable resting site from which moisture can be absorbed through the foot; contact re-hydration is crucial for survival of gastropods (Prior 1985).

- Large diameter, damp rotten logs may act as dispersal corridors and shelter during seasonal drought (Burke et al. 1999) and provide sites for aggregating and mating (Steensma et al. 2009; B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

- Oregon Forestsnail has been observed ovipositing within well-decayed wood (Steensma et al. 2009; B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2012).

Moisture requirements

- Moisture is a large influence on habitat suitability for Oregon Forestsnail and its presence within a habitat patch. Snails are continually susceptible to dehydration and experience constant evaporative water loss through the lung surface and integument as well as through the constant deposition of a dilute mucous trail left during locomotion. Gastropods seek shelter and microhabitat that retain water, humidity, and cool temperatures, and activity patterns predominantly coincide with preventing dehydration (Prior 1985).

- Oregon Forestsnail mating pairs require humidity greater than 76% with optimum humidity 81–100%. These results suggest this environmental factor may have more of an influence over mating activity than air temperature (ranged from 7.1 to 17.0°C) (Steensma et al. 2009).

- Soil parameters measured at three out of seven Oregon Forestsnail mating sites at TWU-ESA recorded 30–37% soil moisture (Steensma et al. 2009).

3.4.2 Limiting Factors to Oregon Forestsnail

Dispersal ability

The dispersal ability of Oregon Forestsnail is likely poor, and it is unclear how much spatial area (habitat) is required to sustain a population within a site or habitat patch. One study showed daily maximum distance at 4.5 m and the maximum displacement over three years at 32.2 m (Edworthy et al. 2012). By their very nature, snails are sedentary and cryptic animals, and their natural ability to colonize new areas is likely poor.

Northernmost extent of global range

Oregon Forestsnail is at the northernmost extent of its global range, which likely increases the species' susceptibility to climatic and stochastic population fluctuations.

Require humid environments

When the forest floor becomes increasingly exposed to wind and sunlight, and there is less vegetation growing throughout the understory, terrestrial molluscs are more vulnerable to dehydration (Prior 1985; Burke et al. 1999) and experience high rates of evaporative water loss through their skin (Dainton 1954a, 1954b; Machin 1964a, 1964b, 1964c; Burton 1964, 1966; Prior et al. 1983; as cited in Prior 1985). Snails are known to initiate "water seeking" responses to dehydration after a short-term reduction in locomotor activity (Prior 1985). The physiology and activity patterns of Oregon Forestsnail inherently make them susceptible to continuous water loss through dehydration. All snails deposit a dilute mucous trail, and experience constant evaporative water loss through the lung surface and integument. Numerous ecological and physiological studies show a relationship between body temperature, hydration and locomotor activity (Machin 1975; Peake 1978; Burton 1983; Riddle 1983; Martin 1983 as cited in Prior 1985). Within two hours, active slugs can lose 30–40% of their initial body weight and habitat selection by slugs is correlated with water availability (Prior 1985). Although this information pertains to slug species, it is likely similar for Oregon Forestsnail.

Soil mineral composition

Soil mineral content (including magnesium and calcium) and pH may play an important factor in snail microhabitat preference. Although unstudied in Oregon Forestsnail, these factors have been known to affect habitat preferences in other gastropods (Wareborn 1969; Hylander et al. 2004).

Native predators

Potential native invertebrate predators include the carnivorous Robust Lancetooth snail (Haplotrema vancouverense) and ground beetles (e.g., Snail-killer Carabid, Scaphinotus angusticollis) (K. Ovaska, pers. comm., 2008; L. Sopuck, pers. comm., 2008). Both species are believed to be gastropod specialists (Thiele 1977) and will follow the slime trails of slugs. Robust Lancetooth has been observed to attack and kill slugs (Ovaska and Sopuck, unpubl. data, 2000). These (and other) invertebrate predators are common throughout the same habitats as Oregon Forestsnail, although there is no known obligate association with the species. Concentration of predators in small habitat patches where little escape cover is available will potentially increase predation rates on Oregon Forestsnail. Competition and predation as a limiting factor may become more of a threat when combined with competition and predation from introduced species and further development pressures. Additional invasive vertebrate predators include Canada Goose (Branta canadensis) at some sites.

Threats are defined as the proximate activities or processes that have caused, are causing, or may cause in the future the destruction, degradation, and/or impairment of the entity being assessed (population, species, community, or ecosystem) in the area of interest (globe, nation, or subnation). For purposes of threat assessment, only present and future threats are consideredFootnote5. Threats presented here do not include biological features of the species or population such as inbreeding depression, small population size, and genetic isolation; or likelihood of regeneration or recolonization for ecosystems, which are considered limiting factors.Footnote6

For the most part, threats are related to human activities, but they can be natural. The impact of human activity may be direct (e.g., destruction of habitat) or indirect (e.g., invasive species introduction). Effects of natural phenomena (e.g., fire, hurricane, flooding) may be especially important when the species or ecosystem is concentrated in one location or has few occurrences, which may be a result of human activity (Master et al. 2009). As such, natural phenomena are included in the definition of a threat, though should be applied cautiously. These stochastic events should only be considered a threat if a species or habitat is damaged from other threats and has lost its resilience, and is thus vulnerable to the disturbance (Salafsky et al. 2008) so that this type of event would have a disproportionately large effect on the population/ecosystem compared to the effect they would have had historically.

The threat classification below is based on the IUCN-CMP (World Conservation Union–Conservation Measures Partnership) unified threats classification system and is consistent with methods used by the B.C. Conservation Data Centre and the B.C. Conservation Framework. For a detailed description of the threat classification system, see the CMP website (CMP 2010). Threats may be observed, inferred or projected to occur in the near term. Threats are characterized here in terms of scope, severity, and timing. Threat "impact" is calculated from scope and severity. For information on how the values are assigned, see Master et al., [PDF; 425 Kb] (2009) and table footnotes for details. Threats for the Oregon Forestsnail were assessed for the entire province (Table 1).

| Threat # | Threat description | ImpactFootnoteh | ScopeFootnotei | SeverityFootnotej | TimingFootnotek |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Residential & commercial development | High | Large (31–70%) | Serious (31–70%) | High |

| 1.1 | Housing & urban areas | High | Large (31–70%) | Extreme (71–100%) | High |

| 1.2 | Commercial & industrial areas | High | Large (31–70%) | Extreme (71–100%) | High |

| 1.3 | Tourism & recreation areas | Low | Small (1–10%) | Slight (1–10%) | High |

| 2 | Agriculture & aquaculture | Low | Restricted (11–30%) | Moderate (11–30%) | High |

| 2.1 | Annual & perennial non-timber crops | Low | Restricted (11–30%) | Moderate (11–30%) | High |

| 2.2 | Wood & pulp plantations | Negligible | Negligible (< 1%) | Slight (1–10%) | Moderate |

| 2.3 | Livestock farming & ranching | Low | Small (1–10%) | Slight (1–10%) | High |

| 3 | Energy production & mining | Low | Small (1–10%) | Extreme (71–100%) | Moderate |

| 3.2 | Mining & quarrying | Low | Small (1–10%) | Extreme (71–100%) | Moderate |

| 3.3 | Renewable energy | Negligible | Negligible (< 1%) | Moderate (11–30%) | High |

| 4 | Transportation & service corridors | Medium | Large (31–70%) | Moderate (11–30%) | High |

| 4.1 | Roads & railroads | Medium | Restricted (11–30%) | Serious (31–70%) | High |

| 4.2 | Utility & service lines | Low | Restricted (11–30%) | Moderate (11–30%) | Moderate |

| 5 | Biological resource use | Low | Small (1–10%) | Serious - Moderate (11–70%) | High |

| 5.1 | Hunting & collecting terrestrial animals | Negligible | Negligible (< 1%) | Serious (31–70%) | High |

| 5.2 | Gathering terrestrial plants | Negligible | Negligible (< 1%) | Unknown | High |

| 5.3 | Logging & wood harvesting | Low | Small (1–10%) | Serious (31–70%) | High |

| 6 | Human intrusions & disturbance | Low | Large (31–70%) | Slight (1–10%) | High |

| 6.1 | Recreational activities | Low | Large (31–70%) | Slight (1–10%) | High |

| 6.2 | War, civil unrest, & military exercises | Negligible | Negligible (< 1%) | Negligible (< 1%) | High |

| 7 | Natural system modifications | Low | Small (1–10%) | Serious (31–70%) | High |

| 7.1 | Fire & fire suppression | Unknown | Large (31–70%) | Unknown | High |

| 7.3 | Other ecosystem modifications | Low | Small (1–10%) | Serious (31–70%) | High |

| 8 | Invasive & other problematic species & genes | Medium - Low | Pervasive (71–100%) | Moderate - Slight (1–30%) | High |

| 8.1 | Invasive non-native/alien species | Medium - Low | Pervasive (71–100%) | Moderate - Slight (1–30%) | High |

| 9 | Pollution | Unknown | Small (1–10%) | Unknown | High |

| 9.3 | Agricultural & forestry effluents | Unknown | Small (1–10%) | Unknown | High |

| 10 | Geological events | Not Calculated | Small (1–10%) | Serious (31–70%) | Unknown |

| 10.1 | Volcanoes | Not Calculated | Unknown | Unknown | Low |

| 10.2 | Earthquakes/tsunamis | Not Calculated | Small (1–10%) | Serious (31–70%) | Unknown |

| 10.3 | Avalanches/landslides | Negligible | Negligible (< 1%) | Moderate (11–30%) | Unknown |

| 11 | Climate change & severe weather | Not Calculated | Restricted – Small (1–30%) | Slight (1–10%) | Low |

| 11.2 | Droughts | Unknown | Pervasive (71–100%) | Unknown | Low |

| 11.4 | Storms & flooding | Not Calculated | Restricted - Small (1–30%) | Slight (1–10%) | Low |

The overall province-wide Threat Impact for this species is Very High to HighFootnote7. The greatest threat is IUCN-CMP Threat 1 Residential and commercial development. Additional threats are discussed below under the Threat Level 1 headings and a summary of the threats by site is provided in Appendix 1.

Oregon Forestsnail's geographic range in southwestern B.C. coincides with the most densely populated and developed part of the province. There has been extensive habitat loss from historic activities (e.g., logging, agriculture, urbanization). In particular, low elevation (< 300 m) habitats within the Coastal Western Hemlock (CWH) biogeoclimatic zone have been extensively modified over the past century as a result of urbanization, forestry, and agriculture. Little of the original forest remains and most habitat patches are < 100 ha. Urban and agricultural development, combined with natural succession, fire suppression, and infilling/draining of lowland wetland riparian habitats, has likely led to the isolation of populations and subsequent inability of Oregon Forestsnails to disperse and recolonize habitat patches. Eventually, isolation combined with threats and limiting factors likely led to its extirpation within some areas of suitable habitat in B.C.

Restricting Oregon Forestsnail sites into smaller habitat patches likely increases the snails' vulnerability to dehydration (e.g., of the forest floor [Prior 1985; Burke et al. 1999]), flooding of the forest floor, reduced genetic diversity, and harmful fluctuations in microclimate (Prior 1985).

1.1 Housing and urban areas and 1.2 Commercial and industrial areas

Natural habitats, large ravines, and riparian areas that represent core habitats for Oregon Forestsnail coincide with the local government jurisdictions of Abbotsford, Mission, Chilliwack, Langley, Fort Langley, and Hope. Expanding human population in these lowland urban areas threatens habitats. Human activities associated with urban developments, specifically those that include clearing or removing Oregon Forestsnail habitat and/or altering natural hydrological patterns that result in habitat conditions that are too dry or wet for prolonged periods, can impact the microhabitat and overall forest stand structure necessary to sustain populations of Oregon Forestsnail.