Recovery Strategy for the Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in Canada 2017 [Proposed]

Phantom Orchid

- Part 1 – Federal addition to the Recovery Plan for the Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in British Columbia, prepared by Environment and Climate Change Canada.

- Figure 1. Critical habitat for Phantom Orchid on southeastern Vancouver Island (south) for Population 1 (Gowlland Tod Provincial Park), and Population 2 (Colwood).

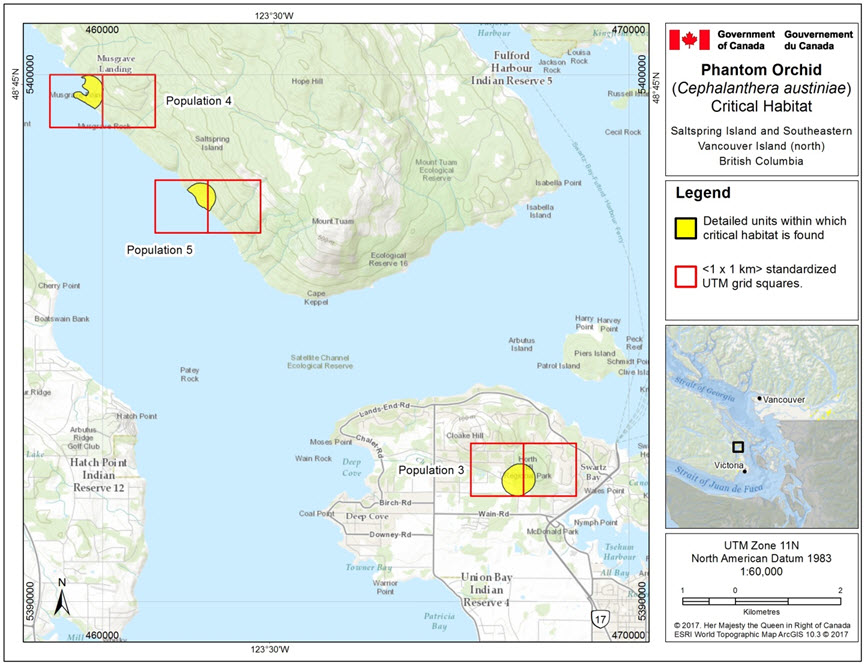

- Figure 2. Critical habitat for Phantom Orchid on Saltspring Island and southeastern Vancouver Island (north) for Population 3 (Horth Hill, North Saanich), Population 4 (Saltspring Island, Musgrave Landing), and Population 5 (Saltspring Island Mount Tuam, 2.4 km West of, ).

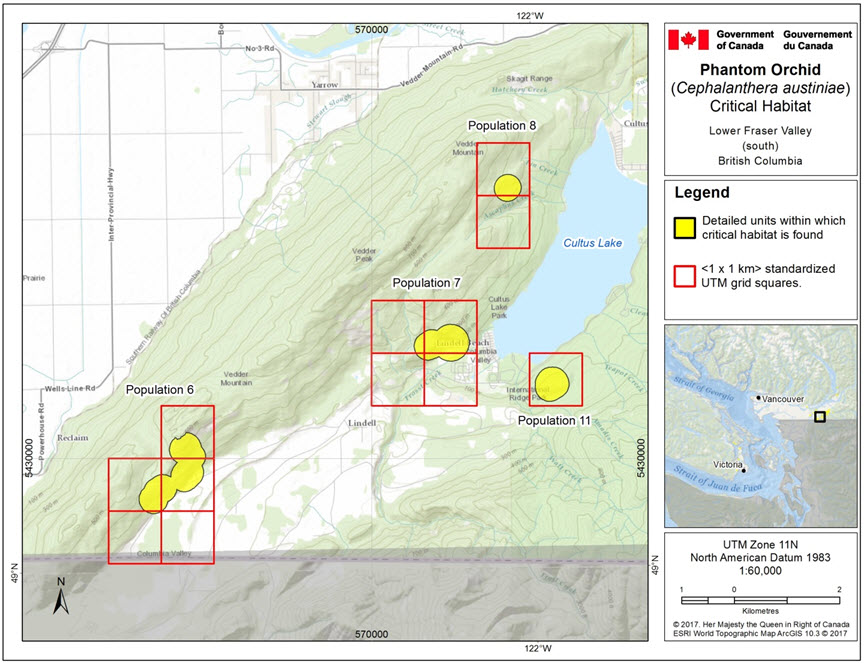

- Figure 3. Critical habitat for Phantom Orchid in the Lower Fraser Valley (south) for Population 6 (Vedder Mountain, S foot of), Population 7 (Lindell Beach, W of Cultus Lake), Population 8 (Vedder Mountain North), and Population 11 (Cultus Lake Provincial Park, Teapot Hill).

- Figure 4. Critical habitat for Phantom Orchid in the Lower Fraser Valley (west) for Population 9 (Sumas Mountain, Ryder Trail), Population 10 (McKee Peak, SW slope of), Population 19 (Sumas River / Vedder Canal, 1.4 km SW of (East Pumptown Quarry)), and Population 21 (Westminster Abbey, Mission).

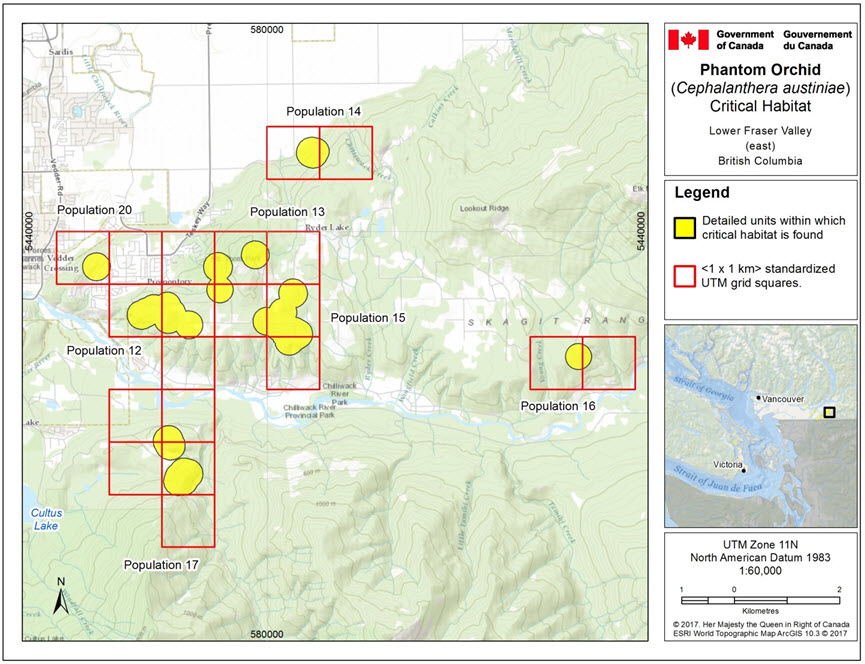

- Figure 5. Critical habitat for Phantom Orchid in the Lower Fraser Valley (east) for Population 12 (Mt. Thom Pop Thornton Rd / Katherine Tye Ecological Reserve), Population 13 (Mt. Thom, Chilliwack (Mt. Thom 2)), Population 14 (Ryder Lake, 1.5 km NW of (Mt. Thom 4)), Population 15 (Mt. Thom, Southside Road (Mt. Thom 3, 5 and 6)), Population 16 (Bench Road), Population 17 (Chilliwack DND training site), and Population 20 (Promontory, Chilliwack (Mt. Thom 7)).

- Figure 6. Critical habitat for Phantom Orchid in the Lower Fraser Valley (north) for Population 18 (Kent) and Population 22 (Harrison Lake, east side of).

- Part 2 – Recovery Plan for the Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in British Columbia, prepared by the Phantom Orchid Recovery Team for the British Columbia Ministry of Environment.

- Table of contents

- 1 COSEWICispecies assessment information

- 2 Species status information

- 3 Species information

- 4 Threats

- 5 Recovery goal and objectives

- 6 Approaches to meet objectives

- 7 Species survival and recovery habitat

- 8 Measuring progress

- 9 Effects on other species

- 10 References

- Table 1. Status and description of phantom orchid populations and sites in British Columbia.

- Table 2. Summary of essential functions, features, and attributes of phantom orchid population habitat in British Columbia.

- Table 3. Threat classification table for phantom orchid in British Columbia.

- Table 4: Recovery actions for phantom orchid.

Recovery strategy for the Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in Canada 2017 [Proposed]

Environment and Climate Change Canada. 2018. Recovery Strategy for the Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in Canada [Proposed]. Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Environment and Climate Change Canada, Ottawa. 2 parts, 17 pp. + 31 pp.

For copies of the recovery strategy, or for additional information on species at risk, including the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) Status Reports, residence descriptions, action plans, and other related recovery documents, please visit the Species at Risk (SAR) Public Registry.

Cover illustration: © Denis Knopp

Également disponible en français sous le titre

« Programme de rétablissement de la Céphalanthère d'Austin(Cephalanthera austiniae) au Canada [Proposition] »

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996), the federal, provincial, and territorial governments agreed to work together on legislation, programs, and policies to protect wildlife species at risk throughout Canada.

In the spirit of cooperation of the Accord, the Government of British Columbia has given permission to the Government of Canada to adopt the Recovery Plan for the Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in British Columbia (Part 2) under Section 44 of the Species at Risk Act (SARA). Environment and Climate Change Canada has included a federal addition (Part 1) which completes the SARA requirements for this recovery strategy.

The federal recovery strategy for the Phantom Orchid in Canada consists of two parts:

Part 1 - Federal Addition to the Recovery Plan for the Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in British Columbia, prepared by Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Part 2 - Recovery Plan for the Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in British Columbia, prepared by the Phantom Orchid Recovery Team for the British Columbia Ministry of Environment.

The federal, provincial, and territorial government signatories under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk (1996) agreed to establish complementary legislation and programs that provide for effective protection of species at risk throughout Canada. Under the Species at Risk Act (S.C. 2002, c.29) (SARA), the federal competent ministers are responsible for the preparation of recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered, and Threatened species and are required to report on progress within five years after the publication of the final document on the SAR Public Registry.

The Minister of Environment and Climate Change is the competent minister under SARA for the Phantom Orchid and has prepared the federal component of this recovery strategy (Part 1), as per section 37 of SARA. To the extent possible, it has been prepared in cooperation with the Province of British Columbia as per section 39(1) of SARA. SARA section 44 allows the Minister to adopt all or part of an existing plan for the species if it meets the requirements under SARA for content (sub-sections 41(1) or (2)). The Province of British Columbia provided the attached recovery plan for Phantom Orchid (Part 2) as science advice to the jurisdictions responsible for managing the species in British Columbia. It was prepared in cooperation with Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Environment and Climate Change Canada, or any other jurisdiction alone. All Canadians are invited to join in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Phantom Orchid and Canadian society as a whole.

This recovery strategy will be followed by one or more action plans that will provide information on recovery measures to be taken by Environment and Climate Change Canada and other jurisdictions and/or organizations involved in the conservation of the species. Implementation of this strategy is subject to appropriations, priorities, and budgetary constraints of the participating jurisdictions and organizations.

The recovery strategy sets the strategic direction to arrest or reverse the decline of the species, including identification of critical habitat to the extent possible. It provides all Canadians with information to help take action on species conservation. When critical habitat is identified, either in a recovery strategy or an action plan, SARA requires that critical habitat then be protected.

In the case of critical habitat identified for terrestrial species including migratory birds SARA requires that critical habitat identified in a federally protected area Footnote1 be described in the Canada Gazette within 90 days after the recovery strategy or action plan that identified the critical habitat is included in the public registry. A prohibition against destruction of critical habitat under ss. 58(1) will apply 90 days after the description of the critical habitat is published in the Canada Gazette.

For critical habitat located on other federal lands, the competent minister must either make a statement on existing legal protection or make an order so that the prohibition against destruction of critical habitat applies.

If the critical habitat for a migratory bird is not within a federal protected area and is not on federal land, within the exclusive economic zone or on the continental shelf of Canada, the prohibition against destruction can only apply to those portions of the critical habitat that are habitat to which the Migratory Birds Convention Act, 1994 applies as per SARA ss. 58(5.1) and ss. 58(5.2).

For any part of critical habitat located on non-federal lands, if the competent minister forms the opinion that any portion of critical habitat is not protected by provisions in or measures under SARA or other Acts of Parliament, or the laws of the province or territory, SARA requires that the Minister recommend that the Governor in Council make an order to prohibit destruction of critical habitat. The discretion to protect critical habitat on non-federal lands that is not otherwise protected rests with the Governor in Council.

Development of this recovery strategy was coordinated by Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service (ECCC CWS) – Pacific Region staff: Kella Sadler and Matt Huntley. Excedera St.Louis, Joanna Hirner (B.C. Ministry of Environment), Brian Retzer, Kym Welstead, Paul Grant, Connie Miller Retzer (B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations), and Marie-Andrée Carrière (ECCC CWS-National Capital Region) provided helpful editorial advice and comment. Clayton Crawford (ECCC CWS-Pacific Region) provided additional assistance with mapping and figure preparation.

The following sections have been included to address specific requirements of the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA) that are not addressed in the Recovery Plan for Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in British Columbia (Part 2 of this document, referred to henceforth as “the provincial recovery plan”), and/or to provide updated or additional information.

Under SARA, there are specific requirements and processes set out regarding the protection of critical habitat. Therefore, statements in the provincial recovery plan referring to protection of survival/recovery habitat may not directly correspond to federal requirements. Recovery measures dealing with the protection of habitat are adopted; however, whether these measures will result in protection of critical habitat under SARA will be assessed following publication of the final federal recovery strategy.

Section 41 (1)(c) of SARA requires that recovery strategies include an identification of the species’ critical habitat, to the extent possible, as well as examples of activities that are likely to result in its destruction. The provincial recovery plan includes information on the habitat and biological needs of Phantom Orchid, and a summary of biophysical attributes (i.e., section 3.3 and 3.4 of that document). This science advice was used as the basis for critical habitat identification in this federal recovery strategy.

Critical habitat for the Phantom Orchid is identified in this document to the extent possible; as responsible jurisdictions and/or other interested parties conduct research to address knowledge gaps, the existing critical habitat methodology and identification may be modified and/or refined to reflect new knowledge.

Critical habitat is partially identified in this recovery strategy. Critical habitat has not been identified for one population that is presumed extirpated (Population 23 – Mount Shannon, Chilliwack). A schedule of studies (Section 1.2) has been included that describes the activities required to complete the identification of critical habitat in support of the population and distribution objectives Footnote2 for the species.

Geospatial location of areas containing critical habitat

Critical habitat is identified for the 22 known extant populations of the Phantom Orchid; population numbers provided below correspond with those provided in the adopted provincial recovery plan. All of the populations occur within the lower Fraser Valley, southeast Vancouver Island and Gulf Islands of British Columbia (Figures 1-6):

Southeast Vancouver Island

- Population 1: Gowlland Tod Provincial Park (Figure 1.)

- Population 2: Colwood (Figure 1)

- Population 3: Horth Hill, North Saanich (Figure 2)

Gulf Islands

- Population 4: Saltspring Island, Musgrave Landing (Figure 2)

- Population 5: Saltspring Island Mount Tuam, 2.4 km West of, (Figure 2)

Lower Fraser Valley

- Population 6: Vedder Mountain, S foot of (Figure 3)

- Population 7: Lindell Beach, W of Cultus Lake (Figure 3)

- Population 8: Vedder Mountain North (Figure 3)

- Population 9: Sumas Mountain, Ryder Trail (Figure 4)

- Population 10: McKee Peak, SW slope of (Figure 4)

- Population 11: Cultus Lake Provincial Park, Teapot Hill (Figure 3)

- Population 12: Mt. Thom Pop Thornton Rd / Katherine Tye Ecological Reserve; Figure 5)

- Population 13: Mt. Thom, Chilliwack (Mt. Thom 2) (Figure 5)

- Population 14: Ryder Lake, 1.5 km NW of (Mt. Thom 4) (Figure 5)

- Population 15: Mt. Thom, Southside Road (Mt. Thom 3, 5 and 6) (Figure 5)

- Population 16: Bench Road (Figure 5)

- Population 17: Chilliwack DND training site (Figure 5)

- Population 18: Kent (Figure 6)

- Population 19: Sumas River / Vedder Canal, 1.4 km SW of (East Pumptown Quarry) (Figure 4)

- Population 20: Promontory, Chilliwack (Mt. Thom 7) (Figure 5)

- Population 21: Westminster Abbey, Mission (Figure 4)

- Population 22: Harrison Lake, east side of (Figure 6)

The Phantom Orchid is found in moist, relatively undisturbed old-growth, mature, and occasionally older second growth (≥50 years) coniferous or mixed-wood forests dominated by Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), Bigleaf Maple (Acer macrophyllum), Western Hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla) or Western Redcedar (Thuja plicata), and often containing Paper Birch (Betula papyrifera). The Phantom Orchid is unusual in that it is a mycoheterotrophic Footnote3 species involved in a three-way relationship with a fungus and a tree whereby it is parasitic upon the ectomycorrhizal Footnote4 fungus associated with the tree species (Taylor and Bruns 1997). The Phantom Orchid requires both the tree and its associated ectomycorrhizal fungus to survive and persist for its own survival.

Most of the Phantom Orchid plant lies below ground in the form of thick rhizomes, with only the flowering stems visible above ground and the number of flowering stems fluctuates from year to year. The actual areal extent of plants below ground is important to the species’ survival, as is the belowground spread and persistence of the fungi; for all populations, both are unknown, and challenging to assess. As such, it is important to recognize that for each population, local microhabitat suitability, and correspondingly the species’ local flowering distribution, may shift in space and time within the broader-scale forest ecosystem.

Therefore, maintaining the potential extent of the local population (including below-ground ectomycorrhizal associations), as well as the integrity of the tree-ectomycorrhizal association and the broader contextual old-growth/mature forest ecosystem is important to the survival and recovery of the species.

The area containing critical habitat for Phantom Orchid is delineated based on:

- application of ≥ 250 m distance around all available verified occurrence records to delineate habitat required by observed occupied areas using three additive components:

- the areas occupied Footnote5 by individual plants or patches of plants, including the associated potential location error from Global Positioning System (GPS) units (ranging from 5 - 25 m uncertainty distance as relevant to each record);

- a 50 m critical function zone distance to encompass immediately adjacent areas, and in acknowledgment that some genets of ectomycorrhizal fungi can extend over 40 metres in association with the root tips of the host plant (Taylor pers. comm. 2014 in COSEWIC 2014);

- an additional 200 m distance to support the broader-scale ecosystem processes occurring in mature, mixed coniferous forests that are integral to the production and maintenance of suitable microhabitat conditions (Chen et al. 1995) for Phantom Orchid and associated ectomycorrhizal fungi; and,

- geospatial exclusion of any areas above 600 m in elevation Footnote6

Biophysical features and attributes of critical habitat

Within the geospatial areas containing critical habitat, critical habitat is identified wherever suitable coniferous and mixed (coniferous-deciduous) forest habitats occur, and includes both the above-ground vegetation components, the ground layer, and the below-ground associated ectomycorrhizal fungi network.

Key attributes of forest habitats that are suitable for Phantom Orchid include:

- Suitable stand age : Mature forest (60-140 years), old forest (>140 years), and older second growth forest (50-60 years); and,

- Suitable stand composition: Dominated by Douglas-fir, Bigleaf Maple, Western Hemlock, Western Redcedar and/or Paper Birch; and

- Suitable ground conditions : Availability of areas having: sparse ground cover, with a well-developed leaf litter layer; soils with high pH (pH >5) and high availability of nutrients (calcium and potassium).

The areas containing critical habitat for Phantom Orchid (totalling 932.3 ha) are presented in Figures 1-6. Critical habitat for the Phantom Orchid in Canada occurs within the shaded yellow polygons (units) shown on each map where the critical habitat criteria described in this section are met. The biophysical attributes required by Phantom Orchid overlap geospatially within suitable habitat types, in that they combine to provide an ecological context for the species at sites where it occurs. Therefore the shaded yellow polygons (units) shown on each map represent identified critical habitat, excepting only those features that clearly do not meet the needs of the species. These include: (i) non-forested habitats (e.g., cleared or young forests, agricultural lands, lawns), (ii) elevations above 600 m, and (iii) existing anthropogenic infrastructure and artificial surfaces (e.g., buildings, running surface of paved roads). The 1 km x 1 km UTM grid overlay shown on this figure is a standardized national grid system that highlights the general geographic area containing critical habitat, for land use planning and/or environmental assessment purposes.

Long description for Figure 1

This map highlights two locations in Southeastern Vancouver Island near Victoria that contain critical habitat polygons for the Phantom Orchid. Each polygon has an overlay of the 1x1 km UTM grid squares in which the critical habitat occurs. The two populations on this map are population 1 and population 2. Population 1 is a circular polygon that spans two UTM grid squares in Gowlland Tod Provincial Park, British Columbia. Population 2 is also a circular polygon that spans two UTM grid squares and is East of Colwood, British Columbia.

Long description for Figure 2

This map highlights three locations in Southeastern Vancouver Island that contain critical habitat for the Phantom Orchid. Each polygon has an overlay of the 1x1 km UTM grid squares in which the critical habitat occurs. The three populations on this map are: population 3, population 4, and population 5. Population 3 is a circular polygon that spans two UTM grid squares in Horth Hill, North Saanich. Population 4 is a polygon along the coast that spans two UTM grid squares in Musgrave Landing on Saltspring Island. Population 5 is also a polygon within two UTM grid squares along the coast west of Mount Tuam on Saltspring Island.

Long description for Figure 3

This map highlights four locations in the southern part of the Lower Fraser Valley that contain critical habitat for the Phantom Orchid. Each polygon has an overlay of the 1x1 km UTM grid squares in which the critical habitat occurs. The four populations on this map are: population 6, population 7, population 8, and population 11. Population 6 is a polygon that spans five UTM grid squares at the south foot of Vedder Mountain. Population 7 is a polygon that spans four UTM grid squares West of Cultus Lake in Lindell Beach. Population 8 is a circular polygon within two UTM grid squares in the Northern part of Vedder Mountain. Population 11 is a circular polygon within one UTM grid square in Cultus Lake Provincial Park on Teapot Hill.

Long description for Figure 4

This map highlights four locations in the western part of the Lower Fraser Valley that contain critical habitat for the Phantom Orchid. Each polygon has an overlay of the 1x1 km UTM grid squares in which the critical habitat occurs. The four populations on this map are: population 9, population 10, population 19, and population 21. Population 9 is a circular polygon that spans two UTM grid squares on the Ryder Trail of Sumas Mountain. Population 10 is a polygon that spans four UTM grid squares on the southwestern point of McKee Peak. Population 19 is a circular polygon within two UTM grid squares along the Sumas River near Pumptown Quarry. Population 21 is a circular polygon within four UTM grid squares at Westminster Abbey in Mission.

Long description for Figure 5

This map highlights seven locations in the eastern part of the Lower Fraser Valley that contain critical habitat for the Phantom Orchid. Each polygon has an overlay of the 1x1 km UTM grid squares in which the critical habitat occurs. The seven populations on this map are: population 12, population 13, population 14, population 15, population 16, population 17, and population 20. Population 12 is a polygon within three UTM grid squares in the Katherine Tye Ecological Reserve. Population 13 is two polygons within four UTM grid squares on Mt. Thom outside of Chilliwack. Population 14 is a circular polygon within two UTM grid squares at Ryder Lake, north of Mt. Thom. Population 15 is a polygon within four UTM grid squares along Southside Rd., Chilliwack at Mt. Thom. Population 16 is a circular polygon within two UTM gridsquares on Bench Road. Population 17 is two populations within five UTM grid squares at the Chilliwack DND training site. Population 20 is a circular polygon within 2 UTM grid squares in Promontory, Chilliwack at Mt. Thom.

Long description for Figure 6

This map highlights two locations in the eastern part of the Lower Fraser Valley that contain critical habitat polygons for the Phantom Orchid. Each polygon has an overlay of the 1x1 km UTM grid squares in which the critical habitat occurs. The two populations on this map are population 18 and population 22. Population 18 is a circular polygon that spans four UTM grid squares in Kent, British Columbia. Population 22 is polygon that spans two UTM grid squares and is on the East side of Harrison Lake, British Columbia.

The following schedule of studies (Table 1) outlines the activities required to complete the identification of critical habitat for Phantom Orchid. This section addresses parts of critical habitat that are known to be missing from the identification based on information that is available at this time. Actions required to address future refinement of critical habitat (such as fine-tuning boundaries, and/or providing greater detail about use of biophysical attributes through studies of the species’ biology and ecological relationships) are not included here. Priority recovery actions to address these kinds of knowledge gaps are outlined in the recovery planning table within the provincial recovery plan.

| Description of activity | Rationale | Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Undertake repeated, comprehensive surveys at one population that is presumed to be extirpated (Population 23 – Mount Shannon, Chilliwack) to verify if Phantom Orchids still occur in remaining patches of suitable habitat, and/or whether suitable habitat can be restored at the site. | Information on the species’ status and habitat suitability at this site is required to ensure sufficient critical habitat is identified to meet the population and distribution objectives for Phantom Orchid. | 2017-2022 |

Understanding what constitutes destruction of critical habitat is necessary for the protection and management of critical habitat. Destruction is determined on a case by case basis. Destruction would result if part of the critical habitat were degraded, either permanently or temporarily, such that it would not serve its function when needed by the species. Destruction may result from a single or multiple activities at one point in time or from the cumulative effects of one or more activities over time. The provincial recovery strategy provides a description of limiting factors and potential threats to Phantom Orchid.

Activities described in Table 2 include those likely to cause destruction of critical habitat for the species; however, destructive activities are not limited to those listed.

| Description of activity | Rationale | Additional Information |

|---|---|---|

| Conversion of landscape for human use and development: creation of new buildings/structures. | Conversion of landscape for human use and development can result in direct loss of habitat by removal or burial of biophysical attributes required by Phantom Orchid including host tree and ectomycorrhizal associations. Indirect loss of critical habitat can also occur by alteration of local microsite conditions (such as light and moisture, hydrological conditions) to the extent that it is no longer suitable for Phantom Orchid or its partner species. Developments further promote establishment of alien invasive species, and unmanaged recreational activities. | Related IUCN-CMP Threat: #1.1, 6.1, 8.1 The Fraser Valley is subject to ongoing and concentrated land development for housing and urbanization, particularly in the Abbotsford and Chilliwack areas. |

| Forest harvest activities | Forest harvest can result in direct loss of habitat by removal or burial of biophysical attributes required by Phantom Orchid including host tree and ectomycorrhizal associations. Indirect loss of critical habitat can also occur by alteration of local microsite conditions (such light and moisture) such that the habitat is no longer suitable for Phantom Orchid or its partner species. Forest harvest can have further indirect effects in degrading habitat, e.g., by increasing the potential establishment of alien invasive plants, and increasing herbivory. | Related IUCN-CMP Threat: #5.3, 8.1 Forest harvest is a threat at the Lower Fraser Valley populations and one population on Saltspring Island (Population 5) |

| Recreational activities: creation and/or expansion of recreational areas or trails (hiking, mountain bikes, off-road vehicles etc.). | Conversion of landscape for recreational activities can result in direct loss of habitat by removal or burial of biophysical attributes required by Phantom Orchid including host tree and ectomycorrhizal associations. Indirect loss of critical habitat can also occur by alteration of local microsite conditions (such as light and moisture) to the extent that it is no longer suitable for Phantom Orchid or its partner species. Recreational activities can have further indirect effects in degrading habitat, by compaction or disturbance of soils and increasing the potential establishment of alien invasive plants. | Related IUCN-CMP Threat: #6.1, 8.1 Mountain and/or dirt bike trails currently occur next to at least three populations. Recreational use can increase the risk of invasive plant introductions via uncleaned footwear, vehicles and other equipment. |

| Introduction of alien invasive plants, or efforts to control existing invasive species that do not follow best management practicesb | Alien invasive species cause direct reduction of habitat available for Phantom Orchid plants, and indirect effects, e.g., alteration of shade, water, and nutrients available to exclude niche range of Phantom Orchid. Efforts to control invasive plants through chemical means (e.g., herbicides applied in post-logging treatments) can likewise result in the destruction of critical habitat by degrading biophysical attributes required for survival and/or local microhabitat toxicity. | Related IUCN-CMP Threat: 8.1 Non-native herbaceous and woody invasive plants are present at several Phantom Orchid sites. |

a Threat classification is based on the IUCN-CMP (World Conservation Union–Conservation Measures Partnership) unified threats classification system (www.conservationmeasures.org).

b E.g., see “Best Management Practices for Invasive Plants in Parks and Protected Areas of British Columbia (PDF Version; 15.4 MB)”

One or more action plans for Phantom Orchid will be posted on the Species at Risk Public Registry by 2022.

A strategic environmental assessment (SEA) is conducted on all SARA recovery planning documents, in accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals. The purpose of a SEA is to incorporate environmental considerations into the development of public policies, plans, and program proposals to support environmentally sound decision-making and to evaluate whether the outcomes of a recovery planning document could affect any component of the environment or any of the Federal Sustainable Development Strategy’s (FSDS) goals and targets.

Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that strategies may also inadvertently lead to environmental effects beyond the intended benefits. The planning process based on national guidelines directly incorporates consideration of all environmental effects, with a particular focus on possible impacts upon non-target species or habitats. The results of the SEA are incorporated directly into the strategy itself, but are also summarized below in this statement.

The provincial recovery plan for Phantom Orchid contains a section describing the effects of recovery activities on other species (i.e., Section 9). Environment and Climate Change Canada adopts this section of the provincial recovery plan as the statement on effects of recovery activities on the environment and other species. Recovery planning activities for Phantom Orchid will be implemented with consideration for all co-occurring species, with focus on species at risk, to avoid or minimize negative impacts to these species or their habitats.

COSEWIC (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada). 2014. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the Phantom Orchid Cephalanthera austiniae in Canada. Ottawa. xii + 45 pp.

Chen, J., J.F. Franklin, and T.A. Spies. 1995. Growing-season microclimate gradients from clearcut edges into old-growth Douglas-fir forests. Ecological Applications, 3(1): 74-86.

CMP (Conservation Measures Partnership). 2010. Threats Taxonomy.

Taylor, D.L., and T.D. Bruns. 1997. Independent, specialized invasions of ectomycorrhizal mutualism by two nonphotosynthetic orchids. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science 94:4510-4515.

Recovery Plan for the Phantom Orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in British Columbia

Prepared by

Phantom Orchid Recovery Team

British Columbia Ministry of Environment

March 2017

This series presents the recovery documents that are prepared as advice to the Province of British Columbia on the general approach required to recover species at risk. The Province prepares recovery documents to ensure coordinated conservation actions and to meet its commitments to recover species at risk under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada and the Canada–British Columbia Agreement on Species at Risk.

Species at risk recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed, and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of a species’ persistence in the wild.

Recovery documents summarize the best available scientific and traditional information of a species or ecosystem to identify goals, objectives, and strategic approaches that provide a coordinated direction for recovery. These documents outline what is and what is not known about a species or ecosystem, identify threats to the species or ecosystem, and explain what should be done to mitigate those threats, as well as provide information on habitat needed for survival and recovery of the species. The provincial approach is to summarize this information along with information to guide implementation within a recovery plan. For federally led recovery planning processes, information is most often summarized in two or more documents that together make up a recovery plan: a strategic recovery strategy followed by one or more action plans used to guide implementation.

Information in provincial recovery documents may be adopted by Environment and Climate Change Canada for inclusion in federal recovery documents that federal agencies prepare to meet their commitments to recover species at risk under the Species at Risk Act.

The Province of British Columbia accepts the information in these documents as advice to inform implementation of recovery measures, including decisions regarding measures to protect habitat for the species.

Success in the recovery of a species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that may be involved in implementing the directions set out in this document. All British Columbians are encouraged to participate in these efforts.

To learn more about species at risk recovery in British Columbia, please visit the B.C. Recovery Planning webpage at: Ministry of Environment Recovery Planning webpage.

Phantom Orchid Recovery Team. 2017. Recovery plan for phantom orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) in British Columbia. B.C. Ministry of Environment, Victoria, BC. 31 pp.

Jamie Fenneman

Additional copies can be downloaded from the B.C. Recovery Planning webpage.

This recovery plan has been prepared by the Phantom Orchid Recovery Team, as advice to the responsible jurisdictions and organizations that may be involved in recovering the species. The B.C. Ministry of Environment has received this advice as part of fulfilling its commitments under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk in Canada and the Canada–British Columbia Agreement on Species at Risk.

This document identifies the recovery strategies and actions that are deemed necessary, based on the best available scientific and traditional information, to recover phantom orchid populations in British Columbia. Recovery actions to achieve the goals and objectives identified herein are subject to the priorities and budgetary constraints of participatory agencies and organizations. These goals, objectives, and recovery approaches may be modified in the future to accommodate new findings.

The responsible jurisdictions and all members of the recovery team have had an opportunity to review this document. However, this document does not necessarily represent the official positions of the agencies or the personal views of all individuals on the recovery team.

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that may be involved in implementing the directions set out in this plan. The B.C. Ministry of Environment encourages all British Columbians to participate in the recovery of phantom orchid.

This recovery plan was written by Brian Klinkenberg (Consultant) and Kym Welstead (B.C. Ministry of Forests, Land and Natural Resource Operations [FLNRO]). Additional assistance for the threats assessment was provided by Dave Fraser (B.C. Ministry of Environment [ENV]), Bruce Bennett (Environment Yukon), Carrina Maslovat (Consultant), Greg Ferguson (Consultant), Brenda Costanzo (ENV), Jenifer Penny (ENV), and Karen Timm (Environment and Climate Change Canada [ECCC]) participated in the threats assessment. Additional comments provided by: Carrina Maslovat (Consultant); Rose Klinkenberg (Consultant); Shannon Berch, Peter Fielder, Brenda Costanzo, Joanna Hirner, Erica McClaren, Leah Westereng, and Excedera St. Louis (ENV); Matt Huntley and Kella Sadler (ECCC–Pacific Region); Marie-Andrée Carrière and Veronique Lalande (ECCC–National Capital Region); and Trudy Chatwin and Paul Grant (FLNRO). Funding for this document was provided by ECCC. Former Recovery Team members have contributed to previous versions of this document including Ross Vennesland (Parks Canada), Mary Berbee, (University of British Columbia), Brenda Costanzo (ENV), Katherine Dunster (Consultant), Meeri Durand (Fraser Valley Regional District), Wayne Erickson (FLNRO), Marie Goulden, (Department of National Defense), Kurtis Herperger (Victoria Orchid Society), Rose Klinkenberg (Consultant), Ted Lea (ENV), and Kathleen Wilkinson (Federation of BC Naturalists) and related documents.

Phantom orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) is a non-photosynthetic, mycoheterotrophic species with almost totally white flowering stems. The flowering stems have inconspicuous bractlike leaves and yellow-lipped flowers. Most of the plant occurs below ground as branched, thick, creeping rhizomes. This orchid parasitizes a symbiotic relationship between ectomycorrhizal fungi and a tree. The orchid flowers for only a short period and is dormant through much of the year. Thus, understanding the below-ground components of the plant, its relationships, and their ecological requirements is essential to recovery of phantom orchid. This species may be pollinator-limited in British Columbia. Many components of the biology and ecology of phantom orchid are presently unknown.

Phantom orchid was designated as of Special Concern in April 1992; its status was re-examined and it was designated as Threatened in May 2000. In 2014, after a further re-examination, it was designated as Endangered in Canada by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC). This designation reflected its occurrence in very low numbers in scattered locations and its susceptibility to extirpation because of the species’ dependency on specific habitat conditions and its interdependency on a symbiotic relationship between a fungus and a tree species. It is listed as Threatened in Canada on Schedule 1 of the Species at Risk Act. In British Columbia, phantom orchid is ranked S2 (imperiled) by the Conservation Data Centre and is on the provincial Red list. The B.C. Conservation Framework ranks phantom orchid as a priority 5 under goal 1 (contribute to global efforts for species and ecosystem conservation).

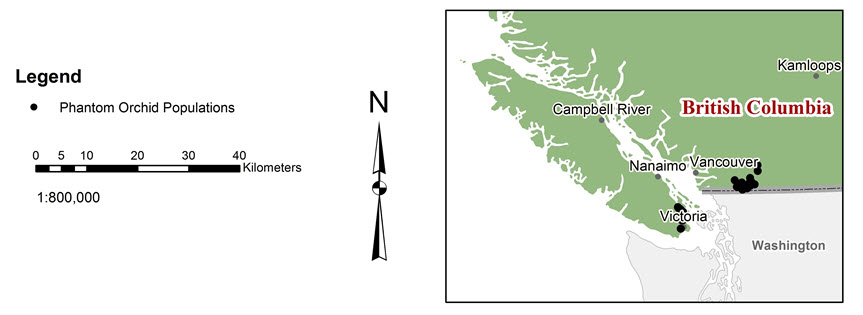

Phantom orchid is restricted in distribution in Canada to the extreme southwest corner of British Columbia, where it is found on southern Vancouver Island, Saltspring Island, and the lower Fraser Valley in the Coastal Western Hemlock and Coastal Douglas-fir biogeoclimatic zones. Distribution extends south in the United States to California and east to Idaho. It is a species that is naturally rare in the landscape and it occurs in relatively undisturbed old growth, mature and occasionally older (50–60 years) second-growth coniferous and mixed forests. In Canada, it is only known at 22 populations.

Main threats to phantom orchid include residential and commercial development (housing and urban areas), recreational activities (human intrusion and disturbance), and invasive non-native plants. Other lower-impact threats include problematic native species (native species grazing), logging and wood harvesting, and livestock farming and ranching (livestock grazing).

The recovery (population and distribution) goal is to maintain the size and distribution of all extant populations of phantom orchid, including any new populations that may be identified.

The following are the recovery objectives:

- Protect Footnote1.1 and restore habitat and features at phantom orchid populations, including locations where the plant is thought to be dormant.

- Conduct targeted inventory at suitable areas to clarify distribution of the species and prevent the inadvertent loss of not-yet discovered populations.

- Manage sites to maintain ecological requirements of the species and to minimize impacts on phantom orchid by addressing and mitigating key threats (e.g., habitat alteration, edge effects, invasive species, and recreation).

- Monitor population trends and habitat status to collect additional ecological data, including information on population numbers and recruitment.

- Address key knowledge gaps and gather additional ecological information to aid in species management.

The recovery of phantom orchid in British Columbia is considered technically and biologically feasible based on the following four criteria that Environment and Climate Change Canada uses to establish recovery feasibility:

i COSEWIC (Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada)

- FRPA:iii No

- OGAA:iii No

- B.C. Wildlife Act:iv No

- SARA:vSchedule 1 - Threatened (2003)

- B.C. List: Red

- B.C. Rank: S2 (2015)

- National Rank: N2 (June 4, 2014)

- Global Rank: G4 (1990)

- Other Subnational Ranks:vii Idaho S3

ii Data source: B.C. Conservation Data Centre (2016), unless otherwise noted.

iii No = not listed in one of the categories of wildlife that requires special management attention to address the impacts of forestry and range activities on Crown land under the Forest and Range Practices Act (FRPA, Province of British Columbia 2002) and/or the impacts of oil and gas activities on Crown land under the Oil and Gas Activities Act (OGAA; Province of British Columbia 2008).

iv No = not designated as wildlife under the B.C. Wildlife Act (Province of British Columbia 1982).

v Schedule 1 = found on the List of Wildlife Species at Risk under the Species at Risk Act (SARA; Government of Canada 2002).

vi Red: Includes any indigenous species or subspecies that have, or are candidates for, Extirpated, Endangered, or Threatened status in British Columbia. S = subnational; N = national; G = global; 1 = critically imperiled; 2 = imperiled; 3 = special concern, vulnerable to extirpation or extinction; 4 = apparently secure; 5 = demonstrably widespread, abundant, and secure; NA = not applicable; NR = unranked.

vii Data source: NatureServe (2016).

viii Data source: B.C. Ministry of Environment (2009).

ix Six-level scale: Priority 1 (highest priority) through to Priority 6 (lowest priority).

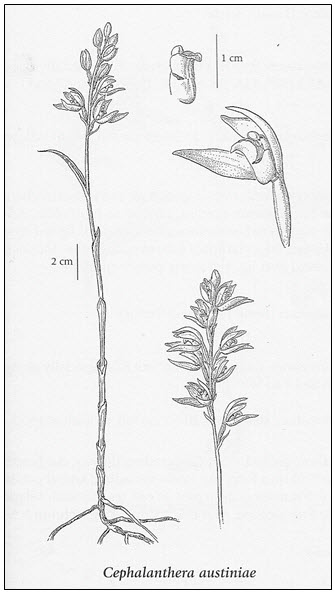

Phantom orchid (Cephalanthera austiniae) is a mycoheterotrophic, perennial orchid that grows in association with a fungus network living in symbiosis with particular tree species. The phantom orchid lives up to its name. Being non-photosynthetic, it is a totally white orchid that stands out on the dark forest floor. Only the aromatic flowering stems are visible above ground. Flowering stems range from 20 to 55 cm in height; stems, bracts, and flowers are white. The lip of the flower is saclike, with a noticeably yellow gland at the base. The two to five leaves are bractlike, 2-6 cm long, and sheath the stems. The flowers occur in terminal racemes of 5-20 flowers (Figure 1; Douglas et al. 2001; Klinkenberg and Klinkenberg 1999). Most of the plant’s biomass occurs underground as branched, thick, creeping rhizomes that can live up to 6 years with periods of dormancy. A commonly mistaken species is Indian pipe (Monotropa uniflora), which is also white but grows in tight clusters with a single nodding flower head per stem.

Long description for Figure 1

Figure 1 shows an image of the structure of Phantom Orchid. On the left there is an illustration of the entire plant, and to the right there are illustrations of the flowering parts.

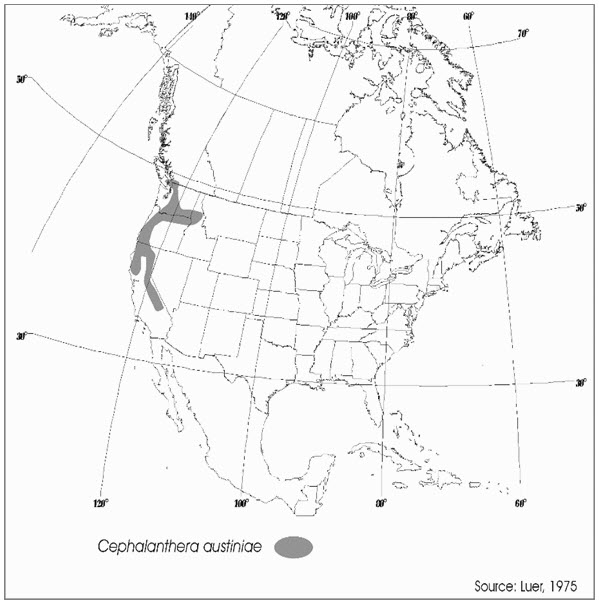

Globally, phantom orchid is found only in North America, where its range extends from central California, north through Oregon, Washington, and Idaho to British Columbia (Figure 2). The Canadian population represents less than 1% of the global distribution of the species. The closest documented occurrence of phantom orchid in Washington State is about 2 km south of the border near Abbotsford, B.C. The species is also found in the San Juan Islands of Washington State, the closest record of which is approximately 3 km from the nearest Canadian records. Rescue (immigration from an outside source) is not considered possible.

In British Columbia, phantom orchid is found in three regions:

- southeastern Vancouver Island (Colwood and the Saanich Peninsula),

- Saltspring Island, and

- the Lower Fraser Valley (principally the Chilliwack region) (Figure 3)

The total extent of occurrence of phantom orchid habitat (a convex polygon drawn around the extant and historical sites for the orchid) is 974 km2. Phantom orchid index of area of occupancy is 100 km2 (based on a 2 X 2 km grid overlaid on all presumed extant sites).

Long description for Figure 2

Figure 2 shows a map of the distribution of Phantom Orchid. The range extends south from southern British Columbia to mid-California along the coast. Two inland portions are found along the southern border of Washington and the eastern border of California.

Twenty-seven recorded phantom orchid populations Footnote2.1 occur in British Columbia; of these, 22 are considered extant, 1 is considered extirpated (habitat is no longer available), and 4 are considered historical, Footnote3.1 not having been observed since 1968 or earlier (Table 1). The 22 populations considered extant include two new populations (i.e., Vedder Mountain North and east of Harrison Lake) discovered since 2014 and, therefore, not referenced in the most recent status report (COSEWIC 2014).

Long description for Figure 3

Figure 3 shows two maps that have the location of Phantom Orchid populations 1-21 in Canada as detailed in Table 1. One map is a large-scale map where each population location is clear, and the other is a small-scale map with less detailed locations.

| Population #a | Population name | B.C. CDC EO # b |

Statusc | Description at last observation | Land tenure (# sites per population) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Gowlland Tod Provincial Park | 1 | Extant confirmed 2013 | 21 stems observed over 2 sites Historical sites: 2 private sites extirpated at Quarry Lake and Hill property |

Provincial park (4) Private (2) |

| 2 | Colwood | 15 | Extant confirmed 2013 | Four stems observed | Private (1) |

| 3 | Horth Hill, North Saanich | 16 | Extant confirmed 2006 | Not observed 2013; last observed 2006 | Regional park (1) |

| 4 | Saltspring Island, Musgrave Landing | 7 | Extant confirmed 2016 | One stem observedd | Provincial Crown (3) |

| 5 | Saltspring Island Mount Tuam, 2.4 km West of | 23 | Extant confirmed 2013 |

43 stems observed over 2 sites; in 2016, 25 stems were observed over 2 sitese | Private (2: 1 landowner) |

| 6 | Vedder Mountain, S foot of | 14 | Extant confirmed 2013 | 76 stems observed over 10 sites | Provincial Crown (6) Unknown ownership (2) Private (2: 2 landowners) |

| 7 | Lindell Beach, W of Cultus Lake | 10 | Extant confirmed 2013 | 4 stems observed over 2 sites | Private (2: 1 landowner) |

| 8 | Sumas Mountain, Ryder Trail | Extant confirmed 2013 | 2 stems observed over 2 sites | Provincial Crown (2) | |

| 9 | McKee Peak, SW slope of | 12 | Extant confirmed 2013 | 5 stems observed over 5 sites | Municipal Crown (1) Private (4: 2 different landowners) |

| 10 | Cultus Lake Provincial Park, Teapot Hill |

2 | Extant confirmed 2013 | 16 stems observed over 6 sites; one new site with one flowering stem was discovered in 2015 near Lindell Beach (Millar, pers. comm., 2015) | Provincial park (7) |

| 11 | Mt. Thom Pop Thornton Rd / Kathrine Tye Ecological Reserve, Chilliwack (Mt. Thom 1) | 3 | Extant confirmed 2013 | 14 stems observed over 7 sites; 2 sites not surveyed | Ecological reserve (5) Private (4: 4 different landowners) |

| 12 | Mt. Thom, Chilliwack (Mt. Thom 2) |

4 | Extant confirmed 2013 1 private site extirpated |

4 stems observed over 3 sites | Regional park (2) Private (1) |

| 13 | Ryder Lake, 1.5 km NW of (Mt. Thom 4) |

19 | Extant confirmed 2013 | 18 stems observed over 2 sites | Private (2: 1 landowner) |

| 14 | Mt. Thom, Southside Road (Mt. Thom 3, 5 and 6) |

5 | Extant confirmed 2013 | 26 stems observed over 12 sites; 2 sites not surveyed | Private (14: 6 different landowners) |

| 15 | Bench Road | NAf | Extant confirmed 2013 | 24 stems observed | Private (1) |

| 16 | Chilliwack DND training site | 17 | Extant confirmed 2013 | 53 stems observed over 5 sites | Federal (5) |

| 17 | Kent | 20 | Extant confirmed 2012 | 30 stems observed; no site information available | Unknown |

| 18 | Sumas River / Vedder Canal, 1.4 km SW of (East Pumptown Quarry) | 21 | Extant confirmed 2008 | 1 stem observed in 1 site. Site is in a protected reserve area, on private land. | Private (1) |

| 19 | Promontory, Chilliwack (Mt. Thom 7) |

22 | Extant confirmed 2008 | 2 stems observed | Private (1) |

| 20 | Westminster Abbey, Mission | 9 | Extant confirmed 2006 | Number of stems not recorded | Private (1) |

| 21 | Harrison Lake, east side of | NAg | Extant confirmed 2014 | 5 stems | Provincial Crown (1) |

| 22 | Vedder Mountain North | New 2016 |

Extant confirmed 2015 | 5 stems observed | Provincial Crown (1) |

| 23 | Mount Shannon, Chilliwack |

13 | Historical/Extirpated last confirmed 1993 | First observed in 1993 (COSEWIC 2000); a search in 2006 failed to find any stems (Barsanti and Iredale 2006); surveys in 1999 and 2000 also failed to find any plants | Private (1) |

| 24 | Brentwood Bay | NA not mapped |

Historical | Unknown | |

| 25 | North Saanich | NA not mapped |

Historical | 1968 specimen by Roemer | Unknown |

| 26 | Agassiz | NA not mapped |

Historical | 1926 herbarium specimen by Ross | Unknown |

| 27 | Chilliwack | NA not mapped |

Historical | 1943 herbarium specimen by Morkill | Unknown |

a Population numbers match numbers of the subpopulations in COSEWIC 2015.

b BC CDC # refers to the B.C. Conservation Data Centre’s Element Occurrence (EO) number.

c Extant: occurrence has been verified as still existing, as of the year listed. Historical: used when there is a lack of recent field information verifying the continued existence of the occurrence. Generally, if no known observation is made for 20-40 years, plant occurrence is considered historical (NatureServe 2015).

d A single stem was observed on May 16, 2016 (Maslovat, pers. comm., 2016).

e Observations made on May 25, 2016 (Maslovat, pers. comm., 2016).

f New sites that had not yet been mapped by the B.C. Conservation Data Centre.

g New site that had not yet been mapped for the COSEWIC report.

The habitat features and biological needs of phantom orchid are described below, and summarized in table 2.

Phantom orchid prefers relatively undisturbed, low-elevation (0-560 m) coniferous or mixed forests composed of structural stage 6 (mature forest, 60-140 years), 7 (old forest, > 140 years), and occasionally older (50-60 years) second-growth forest (COSEWIC 2014; Phantom Orchid Recovery Team 2016). It is a shade-tolerant species, found in the Coastal Western Hemlock and Coastal Douglas-fir biogeoclimatic zones of British Columbia (Meidinger and Pojar 1991). These sites are most often well-drained, open areas with little understory in coniferous forests, mainly dominated by Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii), western redcedar (Thuja plicata), and western hemlock (Tsuga heterophylla), as well as bigleaf maple (Acer macrophyllum) (COSEWIC 2014). Relic populations may also be found in habitats with a higher density of ground cover and a well-developed Ah Footnote4.1 horizon (e.g., Katherine Tye Ecological Reserve) (COSEWIC 2014).

Although phantom orchid is generally assumed to require deep shade, it is found on sites with 30-100 % canopy cover (COSEWIC 2014). Of the 26 surveyed sites in 2006-2007, only thirteen (50%) could be considered deep-shade sites, with maximum total canopy covers of 90-100% (Barsanti et al. 2007).

Topographic features associated with phantom orchid sites include a slight preference for south- to southwest-facing slopes, and benches Footnote5.1 with deeper soils, sometimes adjacent to steep drop-offs. Phantom orchid is found at sites with an undisturbed, intact substrate that allows persistence of below-ground parts and survival of the associated fungal (ectomycorrhizal) network critical for this species (Dunster, pers. comm., 2008; Taylor, pers. comm., 2003, 2005).

Phantom orchid acquires its carbon from fungi, not from photosynthesis, making it mycoheterotrophic (Taylor and Bruns 1997). These ectomycorrhizal fungi link phantom orchid individuals to photosynthetic trees that mutually benefit from the relationship with the fungus (Berch, pers. comm., 2017). Ultimately, the orchid is a parasite on this symbiotic relationship and both the fungal and the tree species must be sustained for the orchid’s survival.

Throughout its range, phantom orchid is associated with as many as 14 species of ectomycorrhizal fungi in the genera Thelephora and Tomentella of the family Thelephoraceae (Taylor and Bruns 1997; Taylor, pers. comm., 2003; Berch, pers. comm., 2017). These “black thelephorids” are usually late-stage fungi that occur nearly exclusively in intact, moist, mature forests and are sensitive to microhabitat features and habitat alteration (e.g., including soil compaction) (Taylor and Bruns 1997; Taylor, pers. comm., 2003, 2005; COSEWIC 2014).

The associated fungus can extend tens of metres beyond the root system of the trees it depends upon and well beyond the areal extent of the flowering orchid stems (Taylor, pers. comm., 2003). Although a single fungal colony (a genet) was observed to extend over 40 m (COSEWIC 2014), the areal extent of terrestrial habitat required for the orchid’s survival must be much larger than this to ensure the effectiveness of the fungi (Hagerman 1997; Kranabetter et al. 2013). Smaller buffers are not supported in the literature as diversity and survivorship of ectomycorrhizal fungi declines at buffer distances of 20-25 m (Hagerman 1997; Kranabetter et al. 2013); however, 40 m is insufficient to protect from windthrow, and to retain soil and air moisture and an intact ecosystem for pollinators. Chen et al. 1995 found that edge effects were present more than 240 m from a clear-cut edge in old-growth Douglas-fir forests. Impacts to microclimatic condition, such as humidity, soil temperature/moisture, and wind, were observed more than 240 m into the forest. Some populations may require a wider area upslope to maintain hydrological conditions.

Phantom orchid requires a soil pH of more than 5 and high availability of nutrients (calcium and potassium). Calcareous soils, including limestone (Clapham et al. 1968), can provide a suitable environment for this orchid. Although these types of soils are limited in southern British Columbia (Klinkenberg 2009), populations of phantom orchid have been found on limestone outcrops, soils with limestone deposits or tailings, and adjacent to limestone quarries or in residential heavily limed compost piles and shell middens (Klinkenberg and Klinkenberg 1999; COSEWIC 2000). Phantom orchid has also been found in soils that are moist, and/or loamy and with parent materials such as volcanics, granitics, sandstone-conglomerate, and quartz-diorite (Klinkenberg 2009). The presence of certain trees (bigleaf maple, paper birch) and animals (grazers) may also help in providing suitable soil pH and adequate nutrient availability in phantom orchid habitat (Turk et al. 2007).

It is not uncommon for phantom orchid to be found in areas where animals graze. Phantom orchid has been found in horse paddocks and in livestock pastures beneath a bigleaf maple and observed along deer trails and in deer beds. It is also known to persist among actively grazing cows (sites with grazing include Gowlland Tod, Sumas Mountain; Osterhold, pers. comm., [2013]; Millar, pers. comm., [2015]; Klinkenberg, pers. comm., 2017). Phantom orchid persistence in grazed areas may be a result of decreased competition from understory plants and/or of increased soil nutrients, particularly nitrogen. This is a complex issue as some nutrients may be beneficial and others harmful. Suz et al. (2014) identified nitrogen as a significant factor in mycorrhizal communities, showing that it may be a primary determinant of mycorrhizal distribution, richness, and evenness. Higher levels of nitrogen in the soil create an environment better suited for nitrophilic fungi, decreasing or eliminating nitrogen-sensitive fungi. The impact of nitrogen on mycorrhizal partners of phantom orchid in British Columbia may be significant and could inform management.

Most phantom orchid biomass lies below ground in the form of thick rhizomes, with only the flowering stems visible above ground. The actual areal extent of plants below ground is unknown and challenging to assess. In addition, dormancy is confirmed in the genus Cephalanthera (Winnal 1999; Shefferson et al. 2005; Shefferson and Tali 2007). For example, C. rubra and C. longifolia have known maximum dormancy periods of 2 and 3 years, respectively (Kull and Arditti 2002). Although the number of flowering stems is influenced by annual weather variation, recorded annual population variability may also be partially due to dormancy (Klinkenberg and Klinkenberg 1991; Coleman 1995; Welstead, pers. comm., 2017). Recognizing dormancy as a component of this species’ biology is important in understanding its population stability. Life expectancy of these orchids is thought to be 5-6 years or more, and this should be considered when determining site viability and habitat needs where dormant populations may be present.

Pollinators play a key biological role in seed development and genetic exchange and thus potential recruitment and eventual expansion of a population. No pollinators have been recorded for phantom orchid in British Columbia. Other Cephalanthera species are reported to be pollinated by halictid bees (family Halictidae) in California (Kipping 1971), and by bees in the genera Andrena (Summerhayes 1968, cited in Dafni and Ivri 1981), Chelostoma, Dufourea, Heriades, and Osmia (Claessens and Kleynen 2013) in Europe. Syrphid flies are also reported as lesser pollinators by Van der Cingel (2001).

The phantom orchid can self-pollinate (Van der Cingel 2001; Kipping 1971, cited in Argue 2012). Although hand-pollinated phantom orchids are reported to produce capsules and seeds (Herperger, pers. comm., 2004, 2005; COSEWIC 2014), the vigour and viability of these seeds may be reduced. Self-pollination does not appear to be the main method of pollination for most of the populations (Klinkenberg, pers. comm., 2017).

Phantom orchid capsule formation, and thus seed production, is low. In 2006, only four of 163 flowering phantom orchid stems in British Columbia were found to produce capsules (1, 1, 2, and 4 capsules; Barsanti et al. 2007), suggesting that this species may be pollinator-limited (does not receive enough visits from pollinators). Although no genetic work has been done on the species, it is also possible that the lack of seed production is associated with inbreeding depression.

Capsule development and seed dispersal in phantom orchid occurs from August through November (Barsanti and Iredale 2005; Barsanti et al. 2006). Orchid seeds are very small and likely wind-dispersed, falling very short distances from the parent plant (COSEWIC 2014). The seeds rely on the presence of ectomycorrhizal fungi for initiating germination, and ultimately recruitment (Bidartondo 2005; MycrobeWiki 2016). This means that the presence and health of the fungi associated with phantom orchid are important biological needs.

| Life stage | Functionh | Feature(s)i | Attributesj |

|---|---|---|---|

| All stagesk | All functions | Intact moist forest (coniferous or mixed) |

|

| All stages | Acquiring nutrition |

Availability of hosts (symbiosis between fungus and tree) |

|

| Mature plant (below ground) |

Dormancy and root growth (nutrient acquisition) |

Soil quality |

|

| Mature plant (above ground) |

Reproduction | Pollinators |

|

| Mature plant (above ground) |

Seed dispersal and germination | Intact moist forest connecting sites |

|

h Function is a life-cycle process of the species.

i Features are the essential structural components of the habitat required by the species.

j Attributes are the building blocks or measurable characteristics of a feature.

k All stages include: germination, above-ground vegetative growth, reproduction (flowering, pollination, capsule development-early May to early August) and seed dispersal (August to November) and dormancy.

l Dominant forest trees in these zones: bigleaf maple (highest frequency 85% of sites), Douglas-fir (found at 81% of sites), western redcedar, western hemlock, and paper birch.

Phantom orchid is a unique species and the ecological role is currently unknown. As peripheral populations occurring at the northern limits of the species’ range, the provincial populations may be of evolutionary importance. Peripheral populations are important for survival of the species in the face of climate change and may be reservoirs of genetic diversity (Channell and Lomolino 2000a, b).

Limiting factors are generally not human-induced and include characteristics that make the species less likely to respond to recovery/conservation efforts (e.g., inbreeding, small population size, limited dispersal ability). Several biologically limiting factors identified for this species, include:

- Since phantom orchid depends on the symbiotic relationship between a tree and a fungus, it is then also limited by their biological needs. If conditions are unsuitable for either the fungus or the tree, the orchid will not thrive (Taylor, pers. comm., 2005).

- The small population size of this species in Canada means that it is vulnerable to catastrophic loss, low genetic diversity, and possible inbreeding depression.

- Phantom orchid may be sensitive to competition from other species as it occurs most frequently, though not always, in sites with little to no undergrowth.

- Phantom orchids and the ectomycorrhizal network may be influenced and/or limited by soil nutrients. This species is primarily found in areas of limestone outcrops or calcareous soil.

- Although this species is known to self-pollinate, a lack of pollinators and limited seed dispersal may also be limiting factors.

Threats are defined as the proximate activities or processes that have caused, are causing, or may cause in the future the destruction, degradation, and/or impairment of the entity being assessed (population, species, community, or ecosystem) in the area of interest (global, national, or subnational) (adapted from Salafsky et al. 2008). For purposes of threat assessment, only present and future threats are considered. Threats presented here do not include limiting factors, which are presented above in Section 3.5.

The threat classification below is based on the IUCN-CMP (World Conservation Union-Conservation Measures Partnership) unified threats classification system and is consistent with methods used by the B.C. Conservation Data Centre. For a detailed description of the threat classification system, see the Open Standards website (Open Standards 2014). Threats may be observed, inferred, or projected to occur in the near term. Threats are characterized here in terms of scope, severity, and timing. Threat impact is calculated from scope and severity. For information on how the values are assigned, see Master et al. (2012) and table footnotes for details. Threats for phantom orchid were assessed for the entire province (Table 3).

| Threat #m | Threat description | Impactn | Scopeo | Severityp | Timingq | Population(s)r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Residential & commercial development | High | Large | Extreme | High | |

| 1.1 | Housing & urban areas | High | Large | Extreme | High | 1, 2,3, 4, 5, 7, 9, 11, 12, 14, 19, 20 |

| 2 | Agriculture & aquaculture | Low | Small | Serious | High | |

| 2.3 | Livestock farming & ranching | Low | Small | Serious | High | 10, 11 |

| 3 | Energy production & mining | Negligible | Negligible | Extreme | High | |

| 3.2 | Mining & quarrying | Negligible | Negligible | Extreme | High | 18 |

| 4 | Transportation & service corridors | Negligible | Negligible | Unknown | High | |

| 4.1 | Roads & railroads | Negligible | Negligible | Unknown | High | 11, 13 |

| 5 | Biological resource use | Low | Small | Extreme | High | |

| 5.2 | Gathering terrestrial plants | Negligible | Negligible | Extreme | High | 8, 10, 20 |

| 5.3 | Logging & wood harvesting | Low | Small | Extreme | High | 5, 6, 11, 18 |

| 6 | Human intrusions & disturbance | Medium | Restricted | Serious | High | |

| 6.1 | Recreational activities | Medium | Restricted | Serious | High | 1, 3, 6, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14, 16, 17, 22 |

| 8 | Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases | Medium-Low | Restricted | Serious-Moderate | High | |

| 8.1 | Invasive non-native/alien species | Medium-Low | Restricted | Moderate-Slight | High | 3, 9, 11, 14 |

| 8.2 | Problematic native species/diseases | Low | Small | Serious-Moderate | High | 7, 13 |

m Threats are numbered as follows: Level 1 threats (whole numbers) and Level 2 threats (numbers with decimals).

n Impact - The degree to which a species is observed, inferred, or suspected to be directly or indirectly threatened in the area of interest. The impact of each threat is based on severity and scope rating and considers only present and future threats. Threat impact reflects a reduction of a species population. The median rate of population reduction for each combination of scope and severity corresponds to the following classes of threat impact: Very High (75%), High (40%), Medium (15%), and Low (3%). Unknown: used when impact cannot be determined (e.g., if values for either scope or severity are unknown); Not Calculated: impact not calculated as threat is outside the assessment time (e.g., timing is insignificant/negligible [past threat] or low [possible threat in long term]); Negligible: when scope or severity is negligible; Not a Threat: when severity is scored as neutral or potential benefit.

o Scope - Proportion of the species that can reasonably be expected to be affected by the threat within 10 years. Usually measured as a proportion of the species’ population in the area of interest. (Pervasive = 71-100%; Large = 31-70%; Restricted = 11-30%; Small = 1-10%; Negligible < 1%).

p Severity - Within the scope, the level of damage to the species from the threat that can reasonably be expected to be affected by the threat within a 10-year or three-generation time frame. For this species, a generation time of 6 years was used resulting in severity being scored over a 18-year time frame. Severity is usually measured as the degree of reduction of the species’ population. (Extreme = 71-100%; Serious = 31-70%; Moderate = 11-30%; Slight = 1-10%; Negligible < 1%; Neutral or Potential Benefit ≥ 0%).

q Timing - High = continuing; Moderate = only in the future (could happen in the short term [< 10 years or three generations]) or now suspended (could come back in the short term); Low = only in the future (could happen in the long term) or now suspended (could come back in the long term); Insignificant/Negligible = only in the past and unlikely to return, or no direct effect but limiting.

r Numbers correspond to map IDs presented in Figure 3.

The overall province-wide threat impact for this species is High. Footnote6.1 This overall threat considers the cumulative impacts of multiple threats. The greatest threat is from residential and commercial development (Table 3). Low to Medium threats include forestry, invasive species, and agricultural impacts. Details are discussed below under the Threat Level 1 headings and subheadings. The descriptions are divided into “High to Low” and “Negligible” threats. Threats headings are numbered according to their IUCN threat number in Table 3.

The following description of the threats for phantom orchid is based on information presented the COSEWIC 2014 assessment and status report.

4.2.1 High to low threats

Threat 1. Residential & commercial development

1.1 Housing & urban areas

Residential development continues to be the highest threat to phantom orchid. This threat has a High impact. More details on the development pressures is available in the Habitat Trends section included in the 2014 COSEWIC assessment and status report. In the Chilliwack area, large-scale subdivisions, which drastically alter the topography and substrate of a site, are being constructed at a rapid rate in potential phantom orchid habitat (Welstead, pers. comm., 2017). No comprehensive inventory has occurred to detect new populations in many of these residential development areas (Phantom Orchid Recovery Team 2008; Welstead, pers. comm., 2017). Private lands with extant phantom orchid populations (e.g., McKee Peak, Mt. Thom, Promontory, Horth Hill, etc.) continue to be subdivided and developed (Ferguson 2013; Kenny, pers. comm., 2013). On Saltspring Island, one population has been reduced as surrounding development constricted it to a small reserve established for its protection (Annschild, pers. comm., 2013). Development on Vancouver Island may be responsible for the extirpation of plants on at least one private land site (i.e., the Gowlland Tod population).

Several remaining phantom orchid sites occur in suburban areas, in some cases quite close to residences and gardens. As it is unlikely that phantom orchid established here after construction, their presence suggests that the plants survived construction because minimal disturbance occurred to the substrate, below-ground fungal network, host trees, or phantom orchid rhizomes. At sites where phantom orchid is found close to homes, the plant may be threatened by maintenance and construction activities, including tree removal, piling of debris (e.g., brush, leaves, lawn clippings), garden maintenance (e.g., mowing, applications of herbicide or fertilizer), and construction activities associated with gardens, outbuildings, residences, or septic fields. Trampling is also a concern in privately owned suburban sites; although some landowners place cages around plants to protect them, trampling may still damage roots and below-ground fungi.

Threat 2. Agriculture & aquaculture

2.3 Livestock farming & ranching

Livestock farming and ranching are considered a Low threat. The interaction between the abundance of phantom orchids and grazing by livestock (horses, cattle, and goats) is unclear. Grazing likely affects seed set (COSEWIC 2014). A group of flowering stems next to a deer trail at one Saltspring Island population site were grazed (COSEWIC 2000), and herbivore teeth marks were observed on a broken stem at the Cultus Lake population site. At two sites within the Mt. Thom population (Thornton Rd), phantom orchids are no longer found in an area that was logged and then grazed by goats (Ferguson 2013). Grazing in the presence and persistence of the orchid may be beneficial as the removal of livestock grazing appears to result in a decline of flowering stems (Klinkenberg and Klinkenberg 1991; COSEWIC 2000; Barsanti et al. 2007). Removing livestock grazing at the Katherine Tye Ecological Reserve and at private sites within the Mt. Thom population appears to have resulted in a dramatically reduced number of plants and has led to a large increase in the amount of competing understory vegetation (Barsanti and Iredale 2005; Barsanti et al. 2007; Hayens, pers. comm., in Ferguson 2013). The role of grazing on both soil nutrient levels and the ecology of competition still requires research, as well as consideration in land management planning.

Threat 5. Biological resource use

5.3 Logging & wood harvesting

Logging and wood harvesting is considered a Low threat. Clearcut and selective logging operations threaten phantom orchid both directly and indirectly. This threat is greatest in the Fraser Valley, but it is also a potential threat on the privately owned population on Saltspring Island.

The direct impacts of logging operations include the alteration of site conditions (e.g., hydrology or light conditions) from tree removal upslope or next to populations. Even selective tree cutting can irreparably harm the host tree or disturb the associated fungal network (Dunster 2008).

The indirect impacts related to adjacent logging activities can include creating edge effects (Chen et al. 1992), which may alter growing conditions for the associated tree and fungus or the competing understory vegetation (Phantom Orchid Recovery Team 2008). Logging operations also contribute to increased habitat fragmentation, loss of connectivity among sites within and between populations, loss of pollinators, influx of invasive species as competitors, increased herbivory, and post-logging treatments that involve herbicide spray or the seeding of non-native species (Phantom Orchid Recovery Team 2008).

Windthrow above natural background levels has been observed at Ruby Spring related to the clearing that left the area exposed (B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2016). Although the full impact of windthrow on phantom orchid is unknown, it can harm host trees or the fungal host.

Threat 6: Human intrusions & disturbance

6.1 Recreational activities

Recreational activities are considered a Medium threat. Phantom orchid habitat can be damaged by building trails for hiking, mountain bike, and dirt bike activities, which disturbs and/or compacts the soil, changing the growing conditions for the orchid and its fungal host. Dirt bikes and/or mountain bikes frequently use trails next to at least three populations (Sumas Mountain Ryder Trail, Vedder Mountain North, and the south foot of Vedder Mountain; Barsanti and Iredale 2005; B.C. Conservation Data Centre 2016; Maslovat, pers. comm., 2013). Trampling of stems by people or dogs has been observed in provincial parks next to recreational trails (Teapot Hill; Hirner, pers. comm., 2013; Maslovat, pers. comm., 2013). Breakage of the floral stems compromises the reproductive capacity of the plants.

Trail maintenance activities that involve drainage ditching (with the potential to alter hydrology) or the removal of trees (with the potential to inadvertently remove host trees and sources of leaf litter) can also harm phantom orchids (Phantom Orchid Recovery Strategy 2008; Ceska, pers. comm., 2005, 2007, 2008).

Threat 8. Invasive & other problematic species, genes & diseases

8.1 Invasive non-native/alien plants

Invasive terrestrial plants are considered a Medium to Low threat. Non-native invasive plants may compete for resources with phantom orchid or with the host plants, and/or alter plant community composition. Non-native species reported next to phantom orchids include minor amounts of Robert’s geranium (Geranium robertianum), cleavers (Galium aparine), wild chervil (Anthriscus sylvestris), and creeping buttercup (Ranunculus repens). Invasive ornamental plants, including dead-nettle (Lamium sp.) and large periwinkle (Vinca major), are also found close to phantom orchids at some sites (Ferguson 2013; Maslovat, pers. comm., 2013). The full impact of these invasive species on phantom orchid is not known, although flowering stems seem less robust at sites with a denser cover of non-native invasive species (Maslovat, pers. comm., 2013).

Woody invasive species, including filbert (Corylus avellana), English holly (Ilex aquifolium), Himalayan blackberry (Rubus armeniacus), and English ivy (Hedera helix), are also found at several phantom orchid sites (Barsanti and Iredale 2005; Ferguson 2013; Knopp, pers. comm., 2013; Maslovat, pers. comm., 2013). Although the full impact of the presence of these woody invasive species is not known, it is likely that they compete with phantom orchid or the host trees, as well as altering the habitat composition and structure.

8.2 Problematic native species

The proliferation of deer is considered a Low threat. Flowering stems are grazed by Columbian Black-tailed Deer (Odocoileus hemionus columbianus) (COSEWIC 2000; Knopp, pers. comm., 2013; Maslovat, pers. comm., 2013), which limits the reproductive capacity of the plants. Deer populations are increasing in some areas because of forest clearing and the associated creation of edge habitats, as well as a reduction in the number of predators next to populated areas. Deer may play a role in the ecology of this species as phantom orchids apparently grow in deer bedding sites and along deer trails (Phantom Orchid Recovery Team 2016). Grazing also damages flower heads before seeds develop, and trampling can damage the flowering stems (COSEWIC 2000; Barsanti et al. 2007; Maslovat pers. comm., 2013).

4.2.2 Negligible threats

The remaining threats are considered to have Negligible effects on the British Columbian population but are noted because of their possible effects on individuals within populations.

Threat 3. Energy production & mining

3.2 Mining & quarrying

One site (Sumas River/Vedder Canal) is an active rock quarry site. To extract the rock, the site is first clearcut before blasting. Although a setback was created to protect phantom orchid, this protection relies on voluntary cooperation from the mining company. Recent logging and road construction (in 2013) occurred close (within 10 m) to the phantom orchid site, although surveys have not been conducted to determine whether the population was affected (Welstead, pers. comm., 2014).

Mine tenures exist throughout the Chilliwack area, with the potential to affect phantom orchid sites in the future. Planned construction of independent power production facilities may also alter habitat in the future (Welstead, pers. comm., 2017).

Threat 4. Transportation & service corridors