Pugnose shiner (Notropis anogenus): recovery strategy 2012

Table of contents

- Preface

- Responsible jurisdictions

- Authors

- Acknowledgements

- Strategic environmental assessment statement

- Executive summary

- 1. Background

- 2. Recovery

- 2.1 Recovery feasibility

- 2.2 Recovery goals

- 2.3 Population and distribution objective(s)

- 2.4 Recovery objectives

- 2.5 Approaches recommended to meet recovery objectives

- 2.6 Performance measures

- 2.7 Critical habitat

- 2.7.1 Identification of the Pugnose Shiner critical habitat

- 2.7.2 Information and methods used to identify critical habitat

- 2.7.3 Identification of critical habitat: biophysical function, features and their attributes

- 2.7.4 Identification of critical habitat: geospatial

- 2.7.5. Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat

- 2.7.6. Examples of activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat

- 2.8 Existing and recommended approaches to habitat protection

- 2.9 Effects on other species

- 2.10 Recommended approach for recovery implementation

- 2.11 Statement on action plans

- 3. References

- 4. Recovery team members

- Appendix 1

List of figures

- Figure 1. Pugnose Shiner (Notropis anogenus)

- Figure 2. North American distribution of the Pugnose Shiner

- Figure 3a. Distribution of Pugnose Shiner in southwestern Ontario

- Figure 3b. Distribution of Pugnose Shiner in southeastern Ontario

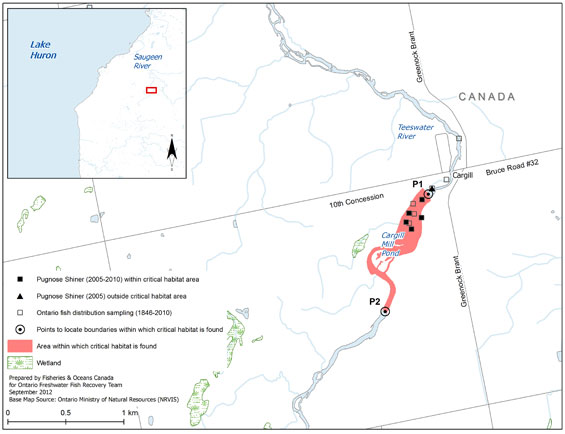

- Figure 4. Area within which critical habitat is found in the Teeswater River

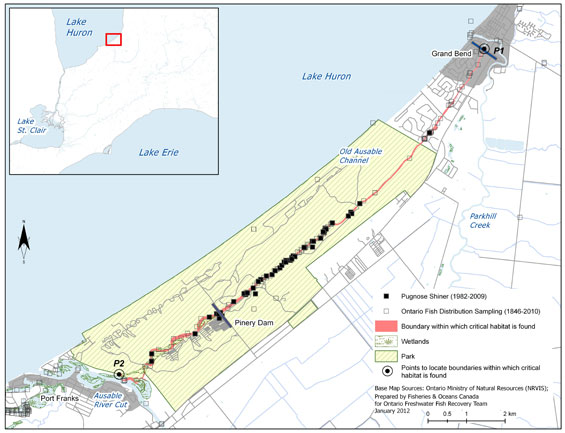

- Figure 5. Area within which critical habitat is found in the Old Ausable Channel

- Figure 6. Area within which critical habitat is found in Mouth Lake

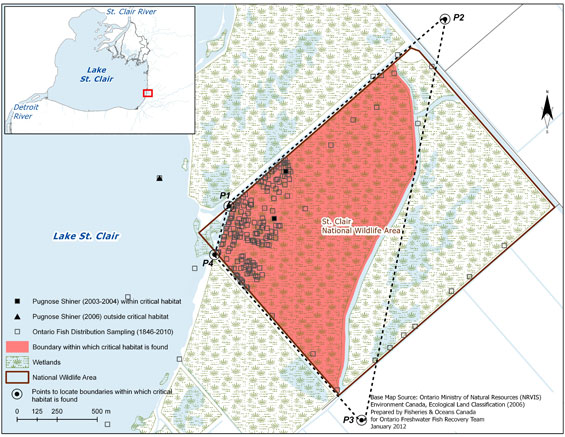

- Figure 7. Area within which critical habitat is found in the St. Clair National Wildlife Area

- Figure 8. Area within which critical habitat is found in Little Bear Creek

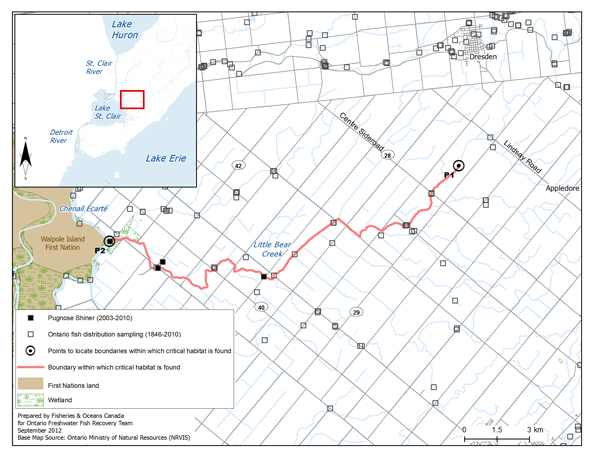

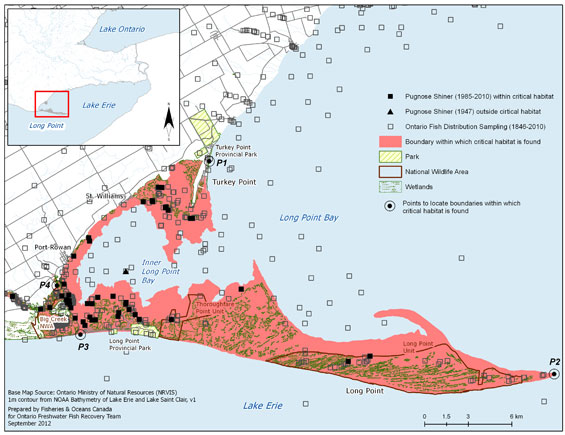

- Figure 9a. Area within which critical habitat is found in Long Point Bay

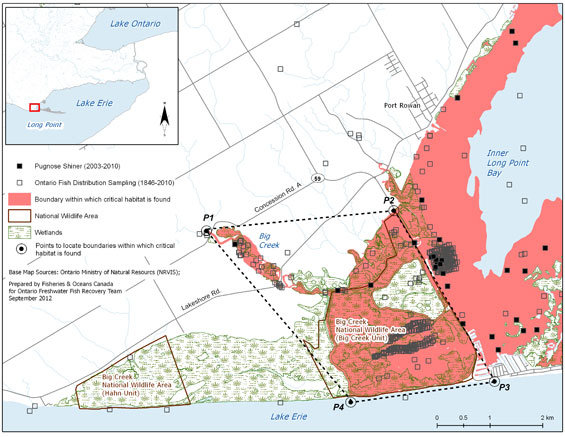

- Figure 9b. Area within which critical habitat is found in Big Creek

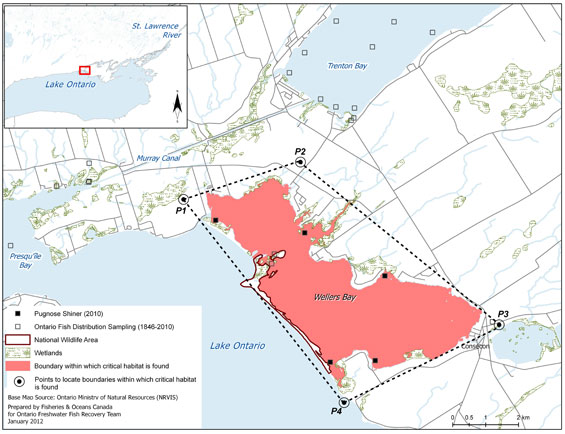

- Figure 10. Area within which critical habitat is found in Wellers Bay

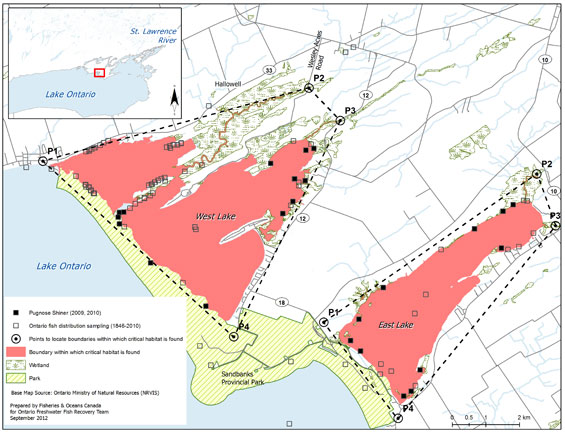

- Figure 11. Area within which critical habitat is found in West Lake and East Lake

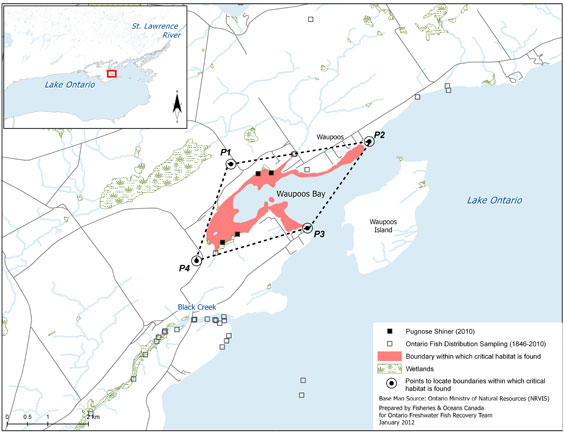

- Figure 12. Area within which critical habitat is found in Waupoos Bay

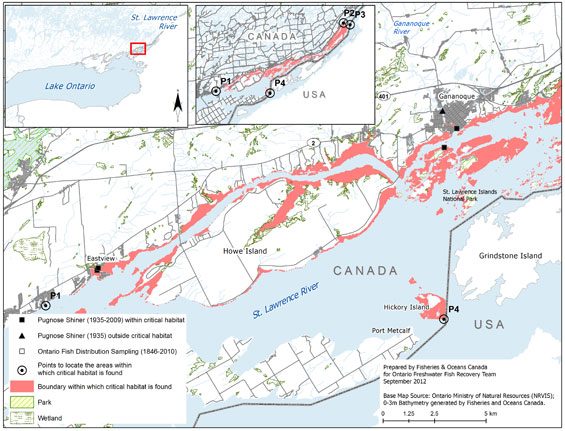

- Figure 13a. Area within which critical habitat is found in the St. Lawrence River

- Figure 13b. Area within which critical habitat is found in the St. Lawrence River

List of tables

- Table 1. Canadian and U.S. national and sub-national status ranks for Pugnose Shiner from NatureServe 2012

- Table 2. Population status and associated certainty of individual Pugnose Shiner populations in Canada

- Table 3. Summary of threats to Pugnose Shiner populations in Canada

- Table 4. Summary of recent (since 2000) fish assemblage surveys in areas of known Pugnose Shiner occurrence

- Table 5. Recovery planning table – research and monitoring

- Table 6. Recovery planning table – management and coordination

- Table 7. Recovery planning table – stewardship, outreach and awareness

- Table 8. Performance measures for evaluating the achievement of recovery objectives

- Table 9. Essential functions, features and attributes of critical habitat for each life stage of the Pugnose Shiner

- Table 10. Coordinates locating the boundaries within which critical habitat is found for the Pugnose Shiner at twelve locations

- Table 11. Comparison of area within which critical habitat is found for each Pugnose Shiner population, relative to the estimated minimum area for population viability (MAPV)

- Table 12. Schedule of studies to identify critical habitat

- Table 13. Human activities likely to result in the destruction of critical habitat for Pugnose Shiner

About the Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series

What is the Species at Risk Act (SARA)?

SARA is the Act developed by the federal government as a key contribution to the common national effort to protect and conserve species at risk in Canada. SARA came into force in 2003 and one of its purposes is “to provide for the recovery of wildlife species that are extirpated, endangered or threatened as a result of human activity.”

What is recovery?

In the context of species at risk conservation, recovery is the process by which the decline of an endangered, threatened, or extirpated species is arrested or reversed and threats are removed or reduced to improve the likelihood of the species’ persistence in the wild. A species will be considered recovered when its long-term persistence in the wild has been secured.

What is a recovery strategy?

A recovery strategy is a planning document that identifies what needs to be done to arrest or reverse the decline of a species. It sets goals and objectives and identifies the main areas of activities to be undertaken. Detailed planning is done at the action plan stage.

Recovery strategy development is a commitment of all provinces and territories and of three federal agencies -- Environment Canada, Parks Canada Agency, and Fisheries and Oceans Canada -- under the Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk. Sections 37–46 of SARAoutline both the required content and the process for developing recovery strategies published in this series.

Depending on the status of the species and when it was assessed, a recovery strategy has to be developed within one to two years after the species is added to the List of Wildlife Species at Risk. Three to four years is allowed for those species that were automatically listed when SARA came into force.

What’s next?

In most cases, one or more action plans will be developed to define and guide implementation of the recovery strategy. Nevertheless, directions set in the recovery strategy are sufficient to begin involving communities, land users, and conservationists in recovery implementation. Cost-effective measures to prevent the reduction or loss of the species should not be postponed for lack of full scientific certainty.

The series

This series presents the recovery strategies prepared or adopted by the federal government under SARA. New documents will be added regularly as species get listed and as strategies are updated.

To learn more about the Species at Risk Act and recovery initiatives, please consult the SARA Public Registry.

Recommended citation

Fisheries and Oceans Canada. 2012. Recovery strategy for the Pugnose Shiner (Notropis anogenus) in Canada (Proposed). Species at Risk Act Recovery Strategy Series. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Ottawa ON. xi +75 p.

Additional copies

Additional copies can be downloaded from the SARA Public Registry.

Cover, title page illustration

© Konrad Schmidt

Également disponible en français sous le titre

« Programme de rétablissement du méné camus(Notropis anogenus) au Canada »

Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans, 2012. All rights reserved.

ISBN En3-4/129-2012E-PDF

Catalogue Number (no.) 978-1-100-19999-3

Content (excluding the illustrations) may be used without permission, with appropriate credit to the source.

Preface

The Pugnose Shiner is a freshwater fish and is under the responsibility of the federal government. The Species at Risk Act (SARA, Section 37) requires the competent minister to prepare recovery strategies for listed Extirpated, Endangered and Threatened species. The Pugnose Shiner was listed as Endangered under SARA in June 2003. The development of this recovery strategy was led by Fisheries and Oceans Canada – Central and Arctic region, in cooperation and consultation with many individuals, organizations and government agencies, as indicated below. The strategy meets SARA requirements in terms of content and process (Sections 39-41).

Success in the recovery of this species depends on the commitment and cooperation of many different constituencies that will be involved in implementing the directions set out in this strategy and will not be achieved by Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Environment Canada (Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario) and Parks Canada Agency or any other party alone. This strategy provides advice to jurisdictions and organizations that may be involved or wish to become involved in the recovery of the species. In the spirit of the National Accord for the Protection of Species at Risk, the Minister of Fisheries and Oceans and the Minister of the Environment invite all responsible jurisdictions and Canadians to join Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Environment Canada (Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario), and Parks Canada Agency in supporting and implementing this strategy for the benefit of the Pugnose Shiner and Canadian society as a whole. Fisheries and Oceans Canada, Environment Canada (Canadian Wildlife Service – Ontario) and Parks Canada Agency will support implementation of this strategy to the extent possible, given available resources and their overall responsibility for species at risk conservation.

The goals, objectives and recovery approaches identified in the strategy are based on the best existing knowledge and are subject to modifications resulting from new information. The competent ministers will report on progress within five years.

This strategy will be complemented by one or more action plans that will provide details on specific recovery measures to be taken to support conservation of the species. The Minister of Fisheries and Oceans will take steps to ensure that, to the extent possible, Canadians interested in or affected by these measures will be consulted.

Responsible jurisdictions

Fisheries and Oceans Canada

Environment Canada, Canadian Wildlife Service - Ontario

Parks Canada Agency

Authors

This document was prepared by Andrea Doherty (Fisheries and Oceans Canada), Amy L. Boyko (Fisheries and Oceans Canada), Sarah P. Matchett (contractor) and Shawn K. Staton (Fisheries and Oceans Canada) on behalf of Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

Acknowledgements

Fisheries and Oceans Canada would like to thank the following organizations for their support in the development of the Pugnose Shiner recovery strategy: Ontario Freshwater Fish Recovery Team, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources, Ontario Parks, Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority, Essex Region Conservation Authority, Trent University, Environment Canada (Canadian Wildlife Service), University of Western Ontario, Parks Canada Agency, St. Clair Region Conservation Authority, Cataraqui Region Conservation Authority, Quinte Region Conservation Authority and the Saugeen Valley Conservation Authority.

Strategic environmental assessment

In accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals, the purpose of a Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is to incorporate environmental considerations into the development of public policies, plans, and program proposals to support environmentally-sound decision making.

Recovery planning is intended to benefit species at risk and biodiversity in general. However, it is recognized that strategies may also inadvertently lead to environmental effects beyond the intended benefits. The planning process based on national guidelines directly incorporates consideration of all environmental effects, with a particular focus on possible impacts on non-target species or habitats.

This recovery strategy will clearly benefit the environment by promoting the recovery of the Pugnose Shiner. The potential for the strategy to inadvertently lead to adverse effects on other species was considered. The SEA concluded that this strategy will clearly benefit the environment and will not entail any significant adverse effects. Refer to the following sections of the document in particular: Description of the Species’ Habitat and Biological Needs, Ecological Role, and Limiting Factors; Effects on Other Species; and, the Recommended Approaches to Meet Recovery Objectives.

Residence

SARA defines residence as: “a dwelling-place, such as a den, nest or other similar area or place, that is occupied or habitually occupied by one or more individuals during all or part of their life cycles, including breeding, rearing, staging, wintering, feeding or hibernating” (SARA S2(1)).

The residence concept is interpreted by Fisheries and Oceans Canada as being constructed by the organism. In this context, Pugnose Shiner do not construct residences during their life cycle and therefore the concept does not apply (Bouvier et al. 2010).

Executive summary

The Pugnose Shiner is a small minnow that is distinguished from similar species by its tiny, upturned, mouth and black stomach cavity lining. Colouration is mostly silver with yellow and olive tints above the lateral black band where scales are heavily outlined. Male Pugnose Shiner can reach total lengths (TL) of 50 mm, while females can reach up to 60 mm TL. This species is found in highly vegetated, clear, slow-moving water, and its distribution and recovery potential is believed to be limited by the distribution and abundance of these habitat types. The Pugnose Shiner is considered globally rare to uncommon (G3), and was designated as Endangered in Canada in November 2002 by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Status at state levels varies from extirpated (SX – Ohio) to vulnerable (S3 in Michigan and Minnesota).

In Canada, Pugnose Shiner distribution is limited to four main regions of Ontario: the southern drainage of Lake Huron, Lake St. Clair, Lake Erie, Lake Ontario and the St. Lawrence River. The species was known historically from Lake Erie (Point Pelee National Park, Rondeau Bay and Long Point Bay) and the St. Lawrence River (Gananoque). Recent captures have confirmed that the species is extant in the following areas:

- Teeswater River,

- Old Ausable Channel,

- Mouth Lake,

- Canard River,

- Lake St. Clair (including Walpole Island) and two of its tributaries (Whitebread Drain/Grape Run Drain and Little Bear Creek),

- St. Clair National Wildlife Area,

- Long Point Bay/Big Creek (including Long Point National Wildlife Area [both Thoroughfare Point Unit and Long Point Unit] and Big Creek National Wildlife Area [Big Creek Unit only]),

- Wellers Bay (including all occasionally exposed lands of Wellers Bay National Wildlife Area lying between the high-water mark and the water’s edge of Wellers Bay, which forms the boundary of Wellers Bay National Wildlife Area and which varies with water level fluctuations of Lake Ontario),

- West Lake,

- East Lake,

- Waupoos Bay, and,

- St. Lawrence River (from Eastview to Mallorytown Landing, including the St. Lawrence Islands National Park).

Extant populations in Ontario occur in areas that are vulnerable to declining habitat quality. Habitat loss and degradation is the principal threat to Pugnose Shiner and may be the result of various factors, such as poor agricultural practices leading to siltation and turbidity, increases in lakeshore development and the removal of aquatic vegetation, as well as human-induced changes in water quality/quantity. The fragmented nature of preferred habitat prevents connectivity of existing populations and may prevent gene flow and/or inhibit colonization of other suitable habitats. Changes in fish communities where Pugnose Shiner are found may have negative effects on the species due to increased predation and/or interspecific competition for resources. Increases in some exotic species, such as Common Carp and Eurasian watermilfoil, may also affect Pugnose Shiner, due to the negative impacts these species can have on native aquatic vegetation.

The long-term recovery goal (over the next 20 years) for Pugnose Shiner is to maintain self-sustaining populations at existing locations and restore self-sustaining populations to historic locations, where feasible.

The following short-term objectives have been established to assist with meeting the long-term recovery goal over the next five to ten years:

- Refine population and distribution objectives;

- Refine and protect critical habitat;

- Determine long-term population and habitat trends;

- Evaluate and minimize threats to the species and its habitat;

- Investigate the feasibility of population supplementation or repatriation for populations that may be extirpated or reduced;

- Enhance efficiency of recovery efforts through coordination with aquatic and terrestrial ecosystem recovery teams and other relevant or complementary groups/initiatives; and,

- Improve overall awareness of Pugnose Shiner and the role of healthy aquatic ecosystems, and their importance to humans.

The recovery team has identified several approaches necessary to ensure that recovery objectives for Pugnose Shiner are met. These approaches have been organized into three categories: Research and Monitoring; Management and Coordination; and, Stewardship, Outreach, and Awareness. Research and Monitoring strategies are crucial to the recovery of Pugnose Shiner because many aspects of its life history and biology are not well known, including its capacity to rebound demographically. Initial surveys will verify extant and uncorroborated accounts of Pugnose Shiner across its range, while a detailed, permanent monitoring program will observe the health of the species and its habitat, as well as potential predators, competitors and exotic species. Research projects will help resolve some uncertainty related to specific habitat requirements, feasibility of population repatriations, and threat mitigation. Management and Coordination strategies include working with other relevant groups, recovery teams and aquatic ecosystem-level recovery strategies that are currently being implemented within a number of the watersheds where Pugnose Shiner is known to occur, namely the Old Ausable Channel, Lake St. Clair (Walpole Island) and the Essex-Erie region. This will allow relevant groups and teams to share information and implement recovery actions. Lastly, through the broad approaches of Stewardship, Outreach and Awareness, the importance of the recovery of Pugnose Shiner will be conveyed to the community at large and stakeholder groups in particular, to obtain support for recovery implementation.

Critical habitat has been identified to the extent possible based upon the best available information for extant Pugnose Shiner locations in the following areas:

- Teeswater River,

- Old Ausable Channel,

- Mouth Lake,

- St. Clair National Wildlife Area,

- Little Bear Creek (Lake St. Clair tributary),

- Long Point Bay/Big Creek (including Long Point National Wildlife Area [both Thoroughfare Point Unit and Long Point Unit] and Big Creek National Wildlife Area [Big Creek Unit only]),

- Wellers Bay (including all occasionally exposed lands of Wellers Bay National Wildlife Area lying between the high-water mark and the water’s edge of Wellers Bay, which forms the boundary of Wellers Bay National Wildlife Area which varies with water level fluctuations of Lake Ontario),

- West Lake,

- East Lake,

- Waupoos Bay, and,

- St. Lawrence River (from Eastview to Mallorytown Landing, including the St. Lawrence Islands National Park).

A schedule of studies has been developed that outlines necessary steps to obtain the information to further refine these critical habitat descriptions.

A dual approach to recovery implementation will be taken combining an ecosystem-based approach with a single-species focus. This will be accomplished through coordinated efforts with relevant ecosystem-based recovery teams (Ausable River, Essex-Erie region, Walpole Island) and their associated Recovery Implementation Groups. The recovery strategy will be supported by one or more action plans that will be developed within five years of the final strategy being posted on the public registry. The success of recovery actions in meeting recovery objectives will be evaluated through the performance measures provided. The entire recovery strategy will be reported on every five years to evaluate progress and to incorporate new information.

1. Background

1.1 Species Assessment Information from COSEWIC

Common name (population): Pugnose Shiner

Scientific name: Notropis anogenus

Current COSEWICstatus & year of designation:Endangered 2002

Canadian occurrence: Ontario

Reason for designation: The Pugnose Shiner has a limited, fragmented Canadian distribution, being found only in Ontario where it is subject to declining habitat quality. The isolated nature of its preferred habitat may prevent connectivity of fragmented populations and may prevent gene flow between existing populations and inhibit re-colonization of other suitable habitats.

COSEWICstatus history: Designated Special Concern in April 1985. Status re-examined and designated Endangered in November 2002.

1.2 Description

The Pugnose Shiner (Notropis anogenus Forbes, 1885) (Figure 1) is a slender, moderately compressed, silvery minnow with a lateral black stripe, and a blunt snout ending in an extremely small, upturned, mouth (Becker 1983; Holm and Mandrak 2002). Total length (TL) is approximately 50 mm for males and 60 mm for females (Holm and Mandrak 2002), but individuals have been caught as large as 72 mm. Overall colouration is silvery with pale yellow tints on the back and silvery below This species is sexually dimorphic during the breeding season when the males take on a bright golden colouration (Smith 1985). The dark lateral band extends from the snout through the eye to the end of the caudal peduncle, terminating in a small dark wedge-shaped caudal spot. All fins are transparent and, unlike other Notropis spp., the peritoneum (lining of abdominal cavity) is black (Holm and Mandrak 2002). The mouth is positioned almost vertical to the body axis (Becker 1983) and is the distinguishing feature that separates the Pugnose Shiner from other species in the black-lined shiner group, especially when they are age-0 juveniles (Leslie and Timmins 2002). This species is most similar in appearance to the Blackchin Shiner (N. heterodon), which is distinguished from the Pugnose Shiner by its larger mouth (Holm and Mandrak 2002). The Pugnose Shiner is also similar in appearance to the Pugnose Minnow (Opsopoeodus emiliae) and Bridle Shiner (N. bifrenatus). The Pugnose Minnow can be distinguished from the Pugnose Shiner by dark areas on the dorsal fin, crosshatched areas on the upper surface and nine dorsal rays (Pugnose Shiner typically has eight dorsal rays) (Page and Burr 1991; Scott and Crossman 1998). The Bridle Shiner is distinguished from the Pugnose Shiner by its larger, upturned mouth, seven anal rays and incomplete lateral line (Page and Burr 1991; Scott and Crossman 1998).

Figure 1. Pugnose Shiner (Notropis anogenus)

(Illustration by Ellen Edmonson, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation)

Long description of Figure 1

Figure 1 is a coloured illustration by Ellen Edmonson, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, from the side, of a Pugnose Shiner.

1.3 Populations and distribution

Global range

The Pugnose Shiner has a limited and disjunct distribution in North America (Figure 2). It is found in the upper Mississippi River, Red River of the North and the Great Lakes basins (Holm and Mandrak 2002). It is found in several tributaries of the Mississippi River in Illinois, Minnesota and Wisconsin, and in the upper Red River of the North drainage of Minnesota and North Dakota (Holm and Mandrak 2002). Within the Great Lakes basin, the Pugnose Shiner is known from tributaries of lakes Huron, Michigan, St. Clair, Erie, eastern Lake Ontario and the upper St. Lawrence River (Holm and Mandrak 2002). Recent declines have been observed across its distribution, although this species has not been monitored sufficiently to determine population trends throughout its range (NatureServe 2012).

Figure 2. North American distribution of the Pugnose Shiner modified from Page and Burr (1991).

Long description of Figure 2

Figure 2 is a line drawing of a map of the Great Lakes area and surrounding regions of the United States and Canada. A scale is provided. The map shows two major areas identified with Pugnose Shiner populations as well as several disjunct smaller areas. These areas are shaded in grey and include tributaries of the Mississippi River in Illinois, Minnesota and Wisconsin, and the upper Red River of the North drainage of Minnesota and North Dakota and, within the Great Lakes basin, tributaries of lakes Huron, Michigan, St. Clair, Erie, eastern Lake Ontario and the upper St. Lawrence River. The map has been modified from A Field Guide to Freshwater Fishes of North America North of Mexico (Page and Burr 1991).

Canadian range

In Canada, this species has only been recorded south of 46 degrees latitude (Leslie and Timmins 2002) in four main areas of Ontario (Figure 3a, 3b): southern Lake Huron, Lake St. Clair, Lake Erie, and eastern Lake Ontario/upper St. Lawrence River.

The species is considered to be extant in the following areas:

- Teeswater River (Saugeen watershed) (Fisheries and Oceans Canada [DFO], unpublished data),

- Old Ausable Channel (Ausable River Recovery Team [ARRT] 2006),

- Mouth Lake (DFO, unpublished data),

- Canard River (Royal Ontario Museum [ROM], unpublished data),

- Lake St. Clair (including Walpole Island) (Holm and Mandrak 2002) and two of its tributaries (Whitebread Drain/Grape Run Drain and Little Bear Creek) (Mandrak et al. 2006b; ROM unpublished data),

- St. Clair National Wildlife Area (Bouvier et al. 2010),

- Long Point Bay/Big Creek (including Long Point National Wildlife Area [both Thoroughfare Point Unit and Long Point Unit] and Big Creek National Wildlife Area [Big Creek Unit only] (Marson et al. 2010) - from this point forward, the phrase Long Point Bay/Big Creek includes reference to the National Wildlife Areas) (Marson et al. 2009),

- Wellers Bay (including all occasionally exposed lands of Wellers Bay National Wildlife Area lying between the high water mark and the water’s edge of Wellers Bay, which forms the boundary of Wellers Bay National Wildlife Area which varies with water level fluctuations of Lake Ontario [DFO, unpublished data] – from this point forward, the phrase Wellers Bay includes reference to the National Wildlife Areas),

- West Lake (DFO, unpublished data),

- East Lake (DFO, unpublished data),

- Waupoos Bay (DFO, unpublished data), and,

- St. Lawrence River (from Eastview to Mallorytown Landing, including the St. Lawrence Islands National Park) (Carlson 1997; Mandrak etal.2006a; J. Van Wieren, Parks Canada [PCA] unpublished data).

Pugnose Shiner was last captured from the Gananoque River in 1935, Point Pelee National Park in 1941, and Rondeau Bay in 1963 (Holm and Mandrak 2002).

Scott and Crossman (1998) described the Canadian range of Pugnose Shiner as diminishing and surmised that it probably occurred historically between the two widely separated areas where it is now found, along the northern shores of lakes Erie and Ontario.

Percentage of global distribution in Canad

Less than 10% of the species’ global range occurs in Canada (ARRT2006).

Distribution trend

The change in the distribution of Pugnose Shiner is difficult to assess due to a lack of data, which has been attributed to the species’ small size, difficulties with field identification and a lack of time-series data (Holm and Mandrak 2002). Three Canadian occurrences are believed to have been lost over the last 50 years (Gananoque River, Point Pelee National Park and Rondeau Bay); however, Pugnose Shiner has been found at a number of new locations across its range, including Mouth Lake, Teeswater River, Little Bear Creek and Whitebread Drain, Wellers Bay, West Lake, East Lake, and Waupoos Bay, as well as numerous locations within the stretch of the St. Lawrence River (approximately 45 km long) between Eastview and Mallorytown Landing, including the St. Lawrence Islands National Park.

Global population size and status

Global population estimates for Pugnose Shiner are not available; however, it is considered generally rare but sometimes locally abundant (NatureServe 2012). It is listed as globally vulnerable, extirpated in Ohio, critically imperilled in Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, New York, and North Dakota, and, vulnerable in Michigan and Minnesota (NatureServe 2012). National and sub-national status ranks are summarized in Table 1.

| Rank level | Rank1 | Jurisdictions |

|---|---|---|

| National (N) | N2 | Canada |

| National (N) | N3 | United States |

| Sub-national (S): Canada | S2 | Ontario |

| Sub-national (S): United States | S1 | Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, New York, North Dakota |

| Sub-national (S): United States | S2 | Wisconsin |

| Sub-national (S): United States | S3 | Michigan, Minnesota |

| Sub-national (S): United States | SX | Ohio |

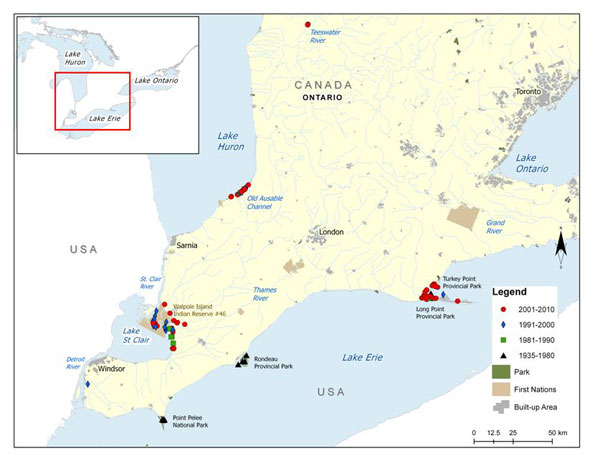

Figure 3a. Distribution of Pugnose Shiner in southwestern Ontario

Long description of Figure 3a

Figure 3a is a map of southwestern Ontario with an inset at the top left of the map showing the geographical location of this map on a larger scale map. A legend and scale are provided. The legend provides symbols denoting years of capture (2001–2010, 1991–2000, 1981–1990, and 1935–1980) as well as for Parks, First Nations, and Built-up Areas. Individual data points are identified by year of capture. The map shows that, for the time period 2001–2010, Pugnose Shiner was found at, or near, the Old Ausable Channel along the Lake Huron shoreline, the Teeswater River, in areas in, or near, the Walpole Island Indian Reserve along the Lake St. Clair shoreline and the mouth of the St. Clair River, and at, or near, Long Point Provincial Park and Turkey Point Provincial Park. Distribution for the time period 1991–2000 was in, or near, the Walpole Island Indian Reserve along the Lake St. Clair shoreline and the mouth of the St. Clair River, with several data points in Long Point Provincial Park and along the Lake Huron shoreline near the Old Ausable Channel. Data points for the 1981–1990 time period are scattered along the shoreline of Lake St. Clair, south of Walpole Island Indian Reserve. Older data points from 1935–1980 are shown at Point Pelee National Park, and Rondeau Provincial Park.

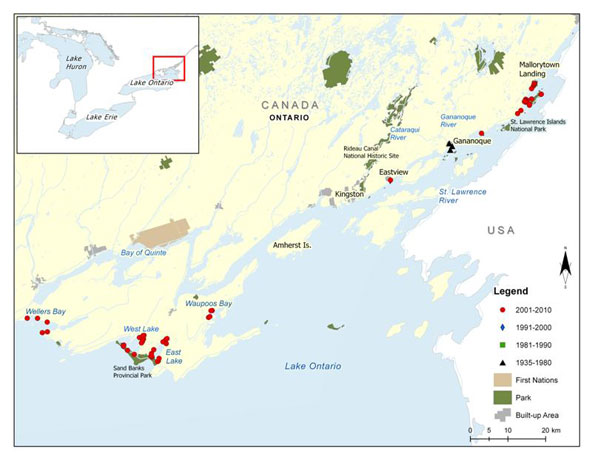

Figure 3b. Distribution of Pugnose Shiner in southeastern Ontario

Long description of Figure 3b

Figure 3b is a map of the eastern end of Lake Ontario with an inset at the top left of the map showing the geographical location of this map on a larger scale map. A legend and scale are provided. The legend provides symbols denoting years of capture (2001–2010, 1991–2000, 1981–1990, and 1935–1980) as well as for Parks, First Nations, and Built-up Areas. Individual data points are identified by year of capture. The map shows that, for the time period 2001–2010, Pugnose Shiner was found in the in the upper St. Lawrence River, upstream of Mallorytown Landing and at, or near Gananoque, Eastview, Waupoos Bay, West Lake, East Lake, and Sand Banks Provincial Park. Older data points from 1935–1980 are shown at the mouth of the Gananoque River.

Canadian population size and status

The status of Pugnose Shiner populations in Canada was assessed by Bouvier et al. (2010) (Table 2). Populations were ranked with respect to abundance and trajectory. Population abundance and trajectory were then combined to determine the population status. A certainty level was also assigned to the population status, which reflected the lowest level of certainty associated with either population abundance or trajectory. Refer to Bouvier et al. (2010) for further details on the methodology.

| Drainage Area | Population2 | Population status | Certainty3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lake Huron drainage | TeeswaterRiver | Unknown | 3 |

| Lake Huron drainage | Old Ausable Channel | Fair | 2 |

| Lake Huron drainage | MouthLake4 | Unknown | 3 |

| Lake St. Clair drainage | St. Clair National Wildlife Area | Unknown | 3 |

| Lake St. Clair drainage | Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | Fair | 2 |

| Lake Erie drainage | Long Point Bay/Big Creek | Poor | 2 |

| Lake Erie drainage | Canard River | Unknown | 3 |

| Lake Erie drainage | Point Pelee National Park | Extirpated | 3 |

| Lake Erie drainage | Rondeau Bay | Extirpated | 3 |

| Lake Ontario drainage | GananoqueRiver | Extirpated | 3 |

| Lake Ontario drainage | Wellers Bay4 | Unknown | 3 |

| Lake Ontario drainage | West Lake | Unknown | 2 |

| Lake Ontario drainage | East Lake4 | Unknown | 3 |

| Lake Ontario drainage | Waupoos Bay4 | Unknown | 3 |

| Lake Ontario drainage | St. Lawrence River | Good | 2 |

(modified from Bouvier et al. 2010)

Lake Huron drainage

The first record of Pugnose Shiner from the Teeswater River, located in the Saugeen River watershed, was in 2005 when three specimens were captured (S. D’Amelio, Trout Unlimited Canada, pers. comm. 2005). Pugnose Shiner was subsequently detected in 2009 and 2010 when two specimens were captured in a reservoir (Cargill Mill Pond) on the river and two were captured downstream of the reservoir (Marson et al.2009). In 2010, 24 individuals were caught within the reservoir from three sampling sites (DFO, unpublished data).

Pugnose Shiner was first collected from the Old Ausable Channel in the early 1980s (ARRT 2006). Between 1982 and 2010, the Old Ausable Channel was sampled extensively, with a variety of gear types, relative to some other Canadian Pugnose Shiner populations. The population in the Old Ausable Channel is believed to have declined in recent years, as only 21 specimens were captured during a survey in 1997 compared to 110 in 1982, despite an increase in effort (Holm and Boehm 1998; ARRT 2006). In 2002, DFO sampled a 5 km reach of the Old Ausable Channel using various gear types and caught 43 Pugnose Shiner, only seven of which were caught in the 1 km reach sampled in 1982 and 1997, suggesting a further decline. However, DFO did not use a beach seine as was done by Holm and Boehm (1998), making inter-annual comparisons difficult. In 2004 and 2005, a total of 291 Pugnose Shiner were captured throughout the Old Ausable Channel (DFO, unpublished data).

L Lake, located near the Old Ausable Channel and containing similar habitat, was sampled in 2007 and 2010 by DFO but Pugnose Shiner was not captured, despite the fact that Lake Chubsucker (Erimyzon sucetta) (a species often found in association with Pugnose Shiner) and other black-lined shiners were detected (DFO, unpublished data). Further sampling at this location and other oxbow lakes near the Old Ausable Channel may detect the presence of the species.

Mouth Lake, located near the Old Ausable Channel and containing similar habitat, was sampled in 2010 by DFO at four sites and a total of 17 Pugnose Shiner were captured (DFO, unpublished data).

Lake St. Clair drainage

In Lake St. Clair, 222 Pugnose Shiner have been captured in Mitchell’s Bay as a result of sampling conducted in 1983, 1996, 2006, and 2007 (Holm and Mandrak 2002; DFO, unpublished data; ROM, unpublished data; K. Soper, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources [OMNR], pers. comm., 2010). Sampling conducted in 1983 and 2006 yielded seven specimens from St. Luke’s Bay (Holm and Mandrak 2002; DFO, unpublished data; ROM, unpublished data). Additional sites in Lake St. Clair (31 sites) were sampled in 2007 by the Essex Region Conservation Authority; however, no Pugnose Shiner were captured (Nelson and Staton 2007).

The delta channels and freshwater coastal marshes of Walpole Island, located at the north end of Lake St. Clair, yielded 281 individuals during a survey in 1999 (Holm and Mandrak 2002) and three specimens were captured in 2002 (ROM, unpublished data).

The species was detected for the first time from the western diked marsh in the St. Clair unit of the St. Clair National Wildlife Area during a graduate study in 2003 and was caught again in 2004 (Bouvier et al.2010).

In 2003, DFOcompleted targeted, wadeable, surveys for fish species at risk in tributaries of Lake St. Clair and captured five Pugnose Shiner (two from Little Bear Creek and three from Whitebread Drain/Grape Run) (Mandrak et al. 2006b). In 2006, nine specimens were captured from Little Bear Creek (ROM, unpublished data), and in 2010 another two specimens were captured (DFO, unpublished data).

Lake Erie drainage:

In the westernmost part of its Canadian range, Pugnose Shiner is known from the Lake Erie drainage. The species was captured in Lake Erie from Point Pelee National Park in 1940 and 1941; from Rondeau Bay in 1940 and 1963; and, from Long Point Bay in 1947 and 1996 (Holm and Mandrak 2002). Despite surveys conducted between 1979 and 1996 at all three locations (with surveys dating back to 1946 in Point Pelee National Park), Pugnose Shiner were only collected in Long Point Bay.

The species was first recorded within Inner Long Point Bay in 1947, Turkey Point in 2007, and the tip of Long Point in 2007 (OMNR, unpublished data). Recent sampling within Inner Long Point Bay has added to our understanding of the species’ distribution within the bay. In 2004, DFO caught 29 specimens in Inner Long Point Bay and one specimen in the Thoroughfare Point unit of Long Point National Wildlife Area during a fish community survey (Marson et al. 2010). In 2007, 38 Pugnose Shiner were caught at eight sites in Turkey Point (Nelson and Staton 2007). Sampling conducted by DFO in 2008 and 2009 yielded 24 specimens from Inner Long Point Bay.

Sampling in 2008 and 2009 vielded six specimens from Big Creek (Haldimand-Norfolk County), which is connected to Inner Long Point Bay (DFO, unpublished data). The Big Creek specimens represent the first records of the species at this location. Sampling conducted by DFO in 2007 and 2008 yielded 15 specimens from Big Creek and Big Creek National Wildlife Area (Big Creek Unit only) (Haldimand-Norfolk County) (DFO, unpublished data). Sampling by Long Point Conservation Authority and OMNR in 2008 - 2010 has captured additional specimens.

Pugnose Shiner was first recorded from the Canard River, close to the confluence of the Detroit River, in 1994 when four specimens were captured (ROM, unpublished data).

Lake Ontario drainage

In Canada, Pugnose Shiner was first collected in the Gananoque River and the upper St. Lawrence River near the town of Gananoque in 1935 (Toner 1937, as cited in Holm and Mandrak 2002). It has not been collected in the Gananoque River since 1935 and it was last recorded from the St. Lawrence site in 1937 (Holm and Mandrak 2002); however, individuals were caught in 1989 at points east (Mallorytown Landing) and west (Eastview) of the original location (Holm and Mandrak 2002). In 2005, DFO captured 256 Pugnose Shiner from three sites adjacent to St. Lawrence Islands National Park, near the Grenadier Island Wetland Complex (Mandrak et al. 2006a; J. Van Wieren, PCA, pers. comm., 2007). From 2006 to 2011, PCAcaptured a total of 495 Pugnose Shiner at over 20 sites (both inside and outside of Park boundaries) from east of Mallorytown Landing to Wolfe Island near Kingston (OMNR 2006; J. Van Wieren, PCA, pers. comm., 2011).

Pugnose Shiner was detected for the first time in West Lake (Prince Edward County, eastern Lake Ontario) in 2009. Two specimens were collected during an electrofishing study conducted by DFO in June 2009 (DFO, unpublished data) and another 32 specimens were captured in September 2009 as a result of targeted sampling for the species (DFO, unpublished data). Subsequent targeted sampling around the lake in 2010 yielded an additional 70 Pugnose Shiner (DFO, unpublished data).

Pugnose Shiner was detected for the first time in Wellers Bay, East Lake, and Waupoos Bay in 2010 as a result of targeted sampling by DFO (DFO, unpublished data). Sixtyfive Pugnose Shiner were caught from four locations in Wellers Bay; 112 Pugnose Shiner were caught from 11 locations in East Lake; and, 172 Pugnose Shiner were caught from four locations in Waupoos Bay.

Percent of global abundance in Canada

Roughly 5 to 10% of the species’ global abundance probably occurs in Canada (ARRT2006).

Population trend

The abundance of Pugnose Shiner has declined in Canada over the last 25 years, with an apparent decline in the Old Ausable Channel and likely losses at Point Pelee National Park, Rondeau Bay (ARRT 2006), and the Gananoque River. Although there are no data available for remaining extant sites, there is a reasonable expectation that similar declines may be occurring at these locations. There are no trend data available for new locations.

1.4 Needs of the Pugnose Shiner

1.4.1 Habitat and biological needs

Spawn to embryonic (yolk-sac stage)

The northern extent of this species may be limited by its temperature requirements for spawning (21-29°C), which occurs in early to mid - June in Ontario (Holm and Mandrak 2002), but can be anywhere from mid - May into July over the distribution of this species. Spawning occurs in densely vegetated waters, no deeper than 2 m, with sand/silt and sometimes gravel substrates (Lane et al. 1996a). The Pugnose Shiner is a lithophil (a non-guarding, open substrate spawner) and eggs are broadcast over vegetation and substrate (Leslie and Timmins 2002). Submersed plants are required for successful reproduction, as they provide essential cover for the highly photophobic (sensitive to light) embryos (Leslie and Timmins 2002). Furthermore, Pugnose Shiner was observed to only move into shallow depths once beds of submergent vegetation appeared at or near the time of spawning (Becker 1983). Becker (1983) also described evidence of ‘prespawning schools’ large schools of individuals (500+), much larger than the normal school size of 15-35 that aggregate prior to spawning events.

Young-of-the-Year (YOY)

YOY Pugnose Shiner require shallow (< 2 m), heavily vegetated habitats, with substrates of sand and silt (Lane et al. 1996b). Juvenile Pugnose Shiner in Ontario have been associated with stonewort (Charavulgaris), Eurasian watermilfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum), wild celery (Vallisneriaamericana), pondweeds (Potamogeton spp), and naiad (Najas flexilis) (Leslie and Timmins 2002).

Adult

Adult Pugnose Shiner are typically found in slow-moving, clear, waters of streams, large lakes and embayments with low gradients and abundant rooted vegetation (Carlson 1997; ARRT 2006). Records of Pugnose Shiner have also been obtained from sheltered inshore ponds, diked wetlands, stagnant channels, and protected bays adjacent to large waterbodies (Parker et al.1987; DFO, unpublished data). Substrates that are associated with adults of this species include sand, mud, organic detritus, clay, and marl (Parker et al. 1985; NatureServe 2012). Both emergent and submergent aquatic plants characterize the areas where Pugnose Shiner is typically found, especially stonewort (Becker 1983). Other types of aquatic vegetation that adults are often associated with include filamentous algae (especially Spirogyra spp.), wild celery, naiad, pondweed and waterweed (Elodea spp.), as well as emergent plants such as cattail (Typha spp.), bulrush (Scirpus spp.) and sedge (Carex spp.) (Becker 1983; Holm and Mandrak 2002; Leslie and Timmins 2002). Additionally, adult Pugnose Shiner are often associated with Eurasian watermilfoil, an exotic plant species. However, Eurasian watermilfoil in high densities may have negative impacts on the species. For example, a proliferation of Eurasian watermilfoil was linked to the extirpation of the Pugnose Shiner and seven other minnow species in a Wisconsin lake (Lyons 1989). Recent habitat analysis of data from the St. Lawrence Islands National Park found a correlation between the presence of greater than 83% submergent vegetation and Pugnose Shiner presence. Additionally, the presence of Potamageton species (particularly Sago Pondweed) appears to be important (J. Van Wieren, PCA, unpublished data).

Pugnose Shiner is typically collected at shallow depths in less than 3 m of water (Holm and Mandrak 2002), but such sampling often occurs in warmer months and this species is believed to move to deeper waters in cool months (Becker 1983). Although it has been suggested that Pugnose Shiner prefers areas with low turbidity (Trautman 1981; Scott and Crossman 1998; Holm and Mandrak 2002), specimens have been captured in areas with higher turbidity levels (e.g., Secchi depths of 0.3 m in Rondeau Bay) (Parker et al. 1987). The species has occasionally been collected from shallow, turbid, waters devoid of aquatic vegetation (Leslie and Timmins 2002).

Pugnose Shiner has been described as a detritivore (feeds on decomposing organic matter) that scrapes accumulated detritus from plant leaves (Goldstein and Simon 1999). However, other accounts suggest the species could be an omnivore. For example, Smith (1985) states that the diet is predominantly made up of various plants and animals up to 2 mm in size, especially stonewort and filamentous green algae, cladocerans, small leeches, and caddisfly larvae (Holm and Mandrak 2002). However, Becker (1983) did not find food items to be limited by this species’ small gape. The stomach contents of eight specimens caught in Mitchell’s Bay (Lake St. Clair) consisted primarily of cladocerans (Chydorus sphaericusand Bosmina longirostris); one individual contained an estimated 1210 C. sphaericus and 370 B. longirostris (Holm and Mandrak 2002). In aquaria, Pugnose Shiner preferentially grazed on plant material, a fact reinforced by its elongated intestine, and only switched to animal sources after the plant source was exhausted (Becker 1983).

1.4.2 Ecological role

Although there are scant data on the physiology, behaviour, and ecology of this species (Leslie and Timmins 2002), it is frequently noted that the Pugnose Shiner is generally sensitive to habitat change, and its continued presence is indicative of good environmental conditions (Smith 1985; Carlson 1997; Essex-Erie recovery team (EERT 2008). Additionally, the Pugnose Shiner is considered by some to be the most sensitive of the black-lined shiner group (Fago 1992, as cited in Carlson 1997). The presence of Blackchin Shiner has been shown to be a good indicator of the presence of the more secretive and timid Pugnose Shiner (Carlson 1997). The Pugnose Shiner is known to be a prey item for a number of piscivorous fishes (Nelson 2006).

1.4.3 Limiting factors

Limiting factors for Pugnose Shiner are not known with certainty; however, available information suggests that they are limited to quiet, clear, densely vegetated waters (ARRT 2006). Even as early as the late 1950s, researchers were indicating that localized populations of this species had been reduced or extirpated due to turbidity and the removal of aquatic vegetation (Bailey 1959; Trautman 1981; Scott and Crossman 1998). Its close association with wetlands may limit the recovery of this species due to the loss of suitable habitat across its range (ARRT 2006).

1.5 Threats

1.5.1 Threat classification

Bouvier et al. (2010) assessed threats to Pugnose Shiner populations in Canada (Table 3). Known and suspected threats were ranked with respect to threat likelihood and threat impact for each population. The threat likelihood and threat impact were then combined to produce an overall threat status. A certainty level was also assigned to the overall threat status, which reflected the lowest level of certainty associated with either threat likelihood or threat impact. See Bouvier et al.(2010) for further details. Additional information is provided in the subsequent threat summaries.

| Threats | Lake Erie drainage: Long Point Bay/Big Creek | Lake Erie drainage: Canard River | Lake Erie drainage: Point Pelee National Park | Lake Erie drainage: Rondeau Bay | Lake Huron drainage: Old Ausable Channel | Lake Huron drainage: Teeswater River |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat modifications | High (3) |

High (3) |

Medium (3) |

High (3) |

High (3) |

Unknown (3) |

| Aquatic vegetation removal | Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

High (3) |

Medium (3) |

Unknown (3) |

| Sediment loading/turbidity | High (3) |

High (3) |

Medium (3) |

High (3) |

High (3) |

Unknown (3) |

| Nutrient loading | High (3) |

High (3) |

Medium (3) |

High (3) |

High (3) |

Unknown (3) |

| Exotic species | Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Unknown (3) |

| Baitfish industry | Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

| Changes in trophic dynamics |

Unknown (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Unknown (3) |

| Threats | Lake St. Clair drainage: Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | Lake St. Clair drainage: St. Clair6 National Wildlife Area |

Lake Ontario drainage: St. Lawrence River | Lake Ontario drainage: Gananoque River | Lake Ontario drainage: West Lake | Lake Huron drainage7: Mouth Lake | Lake Ontario drainage7: Wellers Bay | Lake Ontario drainage7: Waupoos Bay | Lake Ontario drainage7: EastLake |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Habitat modifications | High (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

High (3) |

High (3) |

Medium (3) |

| Aquatic vegetation removal |

Medium (3) |

Low (3) |

Medium (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

| Sediment loading/turbidity | High (3) |

Low (3) |

High (3) |

Unknown (3) |

High (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

High (3) |

| Nutrient loading | High (3) |

Medium (3) |

High (3) |

Unknown (3) |

High (3) |

High (3) |

High (3) |

High (3) |

High (3) |

| Exotic species | Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Medium (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

Medium (3) |

| Baitfish industry | Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

Low (3) |

|

| Changes in trophic dynamics | Unknown (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Unknown (3) |

Unknown (3) |

(Table revised from Bouvier et al. 2010)

1.5.2 Description of threats

Habitat modifications

The preferred habitat of Pugnose Shiner has become isolated as a result of habitat loss and/or degradation across its range. This has been suggested by Leslie and Timmins (2002) to prevent connectivity of fragmented populations and may prevent gene flow between existing populations and/or inhibit colonization of other suitable habitats. Habitat loss can occur in the form of lake and river shoreline modifications (e.g., shoreline hardening projects, piers, docks, marinas) (Holm and Mandrak 2002). Parker et al. (1987) suggested that the amount of available habitat for Pugnose Shiner may have been diminished in quality and quantity due to a general decline in water quality and an increase in lakeshore development. The loss of wetland and riparian forest habitats across southern Ontario has been dramatic since the late 1800s. Continued development of wetlands is a concern. Currently, the general regions where Pugnose Shiner is known to exist have experienced changes in habitat due to development. For example, the Grenadier Island Wetland Complex (Thousand Islands region in the St. Lawrence River), which currently supports a large population of Pugnose Shiner, is threatened by proposed development projects, including three large subdivisions as well as cottage development proposals (J. Van Wieren, PCA, pers. comm., 2007). Some fishermen and resource users from Walpole Island First Nation have noted a decrease in aquatic vegetation, which they attribute to scouring as a result of wakes from ships and lower water levels (C. Jacobs, Walpole Island First Nation, pers. comm., 2011).

Aquatic vegetation removal/control

The removal of aquatic plants from the shallow littoral areas of lakes and rivers is believed to be a serious threat to Pugnose Shiner, given that it is a timid species that requires aquatic plants for cover as well as a source of food, spawning, and larval habitat (Eddy and Underhill 1974; Holm and Mandrak 2002). Pugnose Shiner larvae are highly photophobic when first hatched and require vegetation for cover (Leslie and Timmins 2002). The physical act of removing aquatic vegetation would be harmful to the species; the mechanical removal of vegetation disturbs sediments and creates turbid conditions, and vegetation removal using herbicides introduces potentially harmful chemicals into the water.

Sediment loading/turbidity

Pugnose Shiner is believed to be sensitive to turbidity (Bailey 1959; Carlson 1997; Scott and Crossman 1998; ARRT 2006). As such, excessive sediment inputs constitute a serious threat to the species. Bailey (1959) stated that areas once inhabited by Pugnose Shiner had suffered radical changes in habitat quality, particularly an increase in turbidity and loss of aquatic vegetation, as a result of human land and water use. Sediment loadings could affect Pugnose Shiner by impacting the species’ respiration rates and vision, as well as altering preferred habitat through decreased water clarity, increased siltation of substrates, and the possible selective transport of pollutants, including phosphorus. The excessive siltation of substrates could negatively affect Pugnose Shiner by smothering eggs deposited in the substrate or by degrading potential spawning habitat.

Nutrient loading

Excess nutrient (nitrates and phosphorus) inputs into waterbodies can negatively influence Pugnose Shiner habitat through the development of algal blooms and associated reduced dissolved oxygen concentrations when these blooms die off. Nutrient loading is listed as a primary threat in some areas currently and historically occupied by Pugnose Shiner (i.e., Long Point Bay, Point Pelee National Park, Rondeau Bay) (Essex-Erie recovery strategy (EERT) 2008). This is particularly evident in Rondeau Bay where nutrient loading from adjacent agriculture and residential areas is negatively impacting wetland habitats. Vegetation diversity tends to decline with increased nutrients as species such as cattail and common reed (Phragmites australis) are superior competitors for the excess nutrients (Gilbert et al. 2007). Although wetlands are highly valued for their water filtering capacity, these systems are negatively impacted when nutrient (and chemical) concentrations far exceed background levels (Gilbert et al. 2007).

The persistent elevated concentrations of total phosphorus and apparent trend of increasing nitrate ion concentrations in some watercourses suggest that this is an ongoing concern (EERT 2008).

Exotic species

Common Carp (Cyprinus carpio) may potentially harm Pugnose Shiner by uprooting essential aquatic vegetation required for spawning and cover. Common Carp could also cause an increase in turbidity levels as a result of bioturbation (disturbance of sediments through feeding and other activities) (Lougheed et al. 2004); this would be unlikely in areas with sandy substrates (ARRT2006), but it may pose a risk in Pugnose Shiner locations with finer substrates where Common Carp occur.

Exotic plant species are also a potential concern for Pugnose Shiner in that they can significantly alter wetland vegetation communities (EERT 2008). Two species of particular concern include common reed and Eurasian watermilfoil. Eurasian watermilfoil is an aggressive submerged aquatic plant native to Europe that grows quickly in spring and produces dense mats of vegetation (Environment Canada 2006). This robust plant is able to out-compete established native plant species and create a monoculture, removing the preferred plants of the Pugnose Shiner. In the 1960s, an explosion of Eurasian watermilfoil replaced abundant beds of submerged plants at Rondeau Bay. The watermilfoil mysteriously died out in 1977 and left the habitat unsuitable for re-colonization by any native submerged aquatic plants. It was thought that this was due to increased wave effect that caused erosion and prevented settling of the sediment load entering the bay (Hanna 1984). Also, the extirpation of Pugnose Shiner as well as seven other species in one lake in Wisconsin was linked to the proliferation of Eurasian watermilfoil (Lyons 1989). The thick canopies of vegetation can contribute extra phosphorus and nitrogen to the water column; these extra nutrients can increase algal production, which in turn can result in a decrease in dissolved oxygen when the algae die off. Unfortunately, the removal of Eurasian watermilfoil may also be detrimental to Pugnose Shiner, as the preferred methods of removal include use of the herbicide 2,4-D or mechanical harvesting, which may compromise remaining native plants, particularly in Rondeau Bay (EERT 2008).

Incidental harvest (baitfishing)

Fishery activities that indirectly harvest Pugnose Shiner have the potential to negatively impact population abundance. Of concern is the incidental by-catch of the species in commercial baitfish operations. Pugnose Shiner is not a legal baitfish in Ontario (Cudmore and Mandrak 2011; Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources (OMNR) OMNR2011) and the extent to which the species is a by-catch of baitfish harvesting in Ontario is unknown. Due to the species' relative rarity and sparse distribution, the probability of it being captured incidentally are likely to be low; however, by-catch is still of concern and should be considered a potential threat.

Changes in trophic dynamics

Apparent shifts in fish communities from a cyprinid-dominated (minnows) assemblage to one dominated by centrarchids (sunfishes), have been suggested to have negative impacts on Pugnose Shiner (Holm and Boehm 1998), particularly in the Old Ausable Channel (ARRT 2006). Results of these shifts could include an increase in the number and diversity of predators present and/or an increase in interspecific competition for resources (Holm and Mandrak 2002). Evidence suggests that minnow diversity and abundance decreases with an increase in the number and diversity of littoral predators such as basses (Micropterus spp.) and pikes (Esoxspp.) (Whittier et al. 1997). Species such as Grass Pickerel (Esox americanus vermiculatus) and Northern Pike (E. lucius), co-existed with Pugnose Shiner at Point Pelee National Park in the 1940s; however, other potential predators, such as Black Crappie (Pomoxis nigromaculatus), Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides), and Warmouth (Lepomis gulosus), were not recorded in the Park until 1958 (Holm and Mandrak 2002). It is possible that this increase in predators may have negatively impacted Pugnose Shiner. However, the species was found in association with a wide range of potential predators at sites near Walpole Island in 1999, where it is relatively common (Holm and Mandrak 2002). Potential predators were frequently abundant and included Black Crappie, Bowfin (Amia calva), bullheads (Ameiurus spp.), Grass Pickerel, Largemouth Bass, Longnose Gar (Lepisosteus osseus), Northern Pike, Rock Bass (Ambloplites rupestris), and Yellow Perch (Perca flavescens) (Holm and Mandrak 2002).

It has been theorized that increased competition for resources with juveniles of species such as Black Crappie, Bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus) and adult Brook Silverside (Labidesthes sicculus), (none of which were collected until 1958) may have also played a role in the decline of Pugnose Shiner at Point Pelee National Park. These species have a diet similar to Pugnose Shiner, feeding heavily on cladocerans and occasionally on plant material (Holm and Mandrak 2002). However, Brook Silverside as well as juvenile Bluegill and Black Crappie, occurred together with Pugnose Shiner in 1999 collections at Walpole Island (Holm and Mandrak 2002), so it is uncertain to what extent competition for food is a threat.

Climate change

Climate change has the potential to have significant effects on aquatic communities of the Great Lakes basin through several mechanisms. These include increases in water and air temperatures; changes (decreases) in water levels; shortening of the duration of ice cover; increases in the frequency of extreme weather events; emergence of diseases; and, shifts in predator-prey dynamics (Lemmen and Warren 2004). This may be particularly relevant for the Pugnose Shiner due to its use of coastal wetlands and nearshore habitats. However, it is not possible to predict the likelihood and impact of climate change on each population. Therefore, climate change was not included in the population-specific threat analysis.

1.6 Actions already completed or underway

Ecosystem-based recovery strategies

The following aquatic ecosystem-based recovery strategies include Pugnose Shiner and are currently being implemented by their respective recovery teams. Each recovery team is co-chaired by DFO and a Conservation Authority and receives support from a diverse partnership of agencies and individuals. Recovery activities implemented by these teams include active stewardship and outreach/awareness programs to reduce identified threats; for further details on specific actions currently underway, see Section 2.5.1 (Recovery planning). Funding for these actions is supported by Ontario’s Species at Risk Stewardship Fund and the Government of Canada’s Habitat Stewardship Program (HSP) for species at risk. Additionally, research requirements for species at risk identified in recovery strategies are funded, in part, by the federal Interdepartmental Recovery Fund (IRF). Note: Although these Recovery Strategies are supported by DFO, they are not formally endorsed as recovery strategies under the Species at Risk Act (SARA).

Ausable River ecosystem recovery strategy

The ARRT has developed an ecosystem-based recovery strategy for the 16 aquatic species assessed as at risk by the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada (COSEWIC) in the Ausable River basin. This plan covers six aquatic species at risk listed under SARA, including Pugnose Shiner. The goal of the strategy is to “prepare a recovery plan (recovery strategy and action plan) that sustains and enhances the native aquatic communities of the Ausable River through an ecosystem approach that focuses on species at risk” (ARRT2006).

Essex-Erie recovery strategy

The ecosystem approach has also been taken in the Essex-Erie recovery strategy, which covers 14 aquatic species assessed by COSEWICas being at risk, including Pugnose Shiner (EERT 2008). The Essex-Erie region is located on the north shore of Lake Erie, bordered to the east by the Grand River watershed, to the west by the Detroit River and to the north by Lake St. Clair and the Thames River watershed. The long-term goal of this strategy is “to maintain and restore ecosystem quality and function in the Essex-Erie region to support viable populations of fish species at risk, across their current and former range” (EERT 2008).

Walpole Island ecosystem recovery strategy

The Walpole Island Ecosystem recovery team was established in 2001 to develop an ecosystem-based recovery strategy for the area containing the St. Clair River delta, the largest freshwater delta in the Great Lakes, with the goal of outlining steps to be taken to maintain or rehabilitate the ecosystem and species at risk (Bowles 2005). This recovery strategy covers several aquatic species listed under SARA, including Pugnose Shiner. The recovery goal of the Walpole Island Ecosystem recovery strategy is “to conserve and recover the ecosystems of the Walpole Island Territory in a way that is compliant with the Walpole Island First Nation Environmental Philosophy Statement, provides opportunities for cultural and economic development and provides protection and recovery for Canada’s species at risk” (Bowles 2005).

Recent surveys

Table 4 summarizes recent fish surveys conducted by various agencies within areas of known Pugnose Shiner occurrence.

| Waterbody/general area | Survey description (years of survey effort) | Gear Type | Pugnose Shiner detected (Yes/No) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old Ausable Channel/Mouth Lake | Targeted sampling for species at risk, DFO, Ausable Bayfield Conservation Authority (ABCA )(2002, 2004, 2005, 2009, 2010) | seine, boat electrofishing unit, fyke nets |

Yes

|

| Teeswater River | Targeted sampling, DFO (2005, 2009, 2010) | seine, backpack electrofishing unit |

Yes

|

| Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | Nearshore fish community survey, OMNR (2007, 2008) | seine, boat electrofishing unit |

Yes

|

| Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | Index Surveys of Lake St. Clair, OMNR (annually) |

No

|

|

| Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | Fish community survey, Michigan Department of Natural Resources (1996-2001) | trawl |

Yes

|

| Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | Fish community survey at Walpole Island, ROM (1999 - 2002) | seine, boat electrofishing unit |

No

|

| Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | Essex-Erie targeted sampling for fishes at risk, DFO (2007) | seine, trap nets |

No

|

| Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | YOY index seine survey, OMNR (intermittently since 1979) | seine |

No

|

| Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | Fall trap net survey, OMNR (1974-2007, excluding 1999 and 2002, annual) | trap nets |

Yes

|

| Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | Targeted sampling for species at risk in Lake St. Clair watershed, DFO (2003, 2005-2010) | seine, backpack electrofishing unit |

No

|

| Lake St. Clair and Tributaries | Nearshore fish community survey, DFO (2010) | trawl |

No

|

| Detroit River | Fish-habitat associations of the Detroit River, DFO and the University of Windsor (2003-2004) | seine, boat electrofishing unit |

No

|

| Detroit River | Coastal wetlands of Detroit River, DFO and the University of Guelph (2004-2005) | boat electrofishing unit, fyke nets |

No

|

| Detroit River | Fish community surveys, DFO and OMNR(2003-2004) | boat electrofishing unit |

No

|

| Essex region | Inland watercourses (2000-2001), targeted sampling (2004), surveys of drains and inland watercourses (2004, 2007), DFO and Essex Region Conservation Authority (ERCA) | backpack electrofishing unit |

Yes

|

| Point Pelee National Park and Nearshore Habitats | Fish species composition study (Surette 2006), University of Guelph, DFO and Point Pelee National Park (2002-2003) | seine, trap nets, fyke nets, minnow trap, Windermere trap |

No

|

| Point Pelee National Park and Nearshore Habitats | Spotted Gar (L. oculatus) research, University of Windsor, DFO (2007-2009) | boat electrofishing unit, fyke nets |

No

|

| Rondeau Bay | Fish community surveys, OMNR and DFO (2004-2005) | seine, boat electrofishing unit, fyke nets |

No

|

| Rondeau Bay | Spotted Gar research, University of Windsor, DFO (2007-2009) | boat electrofishing unit, fyke nets |

No

|

| Long Point Bay | Index Surveys of Long Point Bay, OMNR (annually) | trawl |

Yes

|

| Long Point Bay | Fish community assessment, OMNR (2007-2009) | seine, boat electrofishing unit, fyke nets |

Yes

|

| Long Point Bay | Essex-Erie targeted sampling for species at risk (Turkey Point), ERCA/DFO (2007) | seine, boat electrofishing unit, trap nets |

Yes

|

| Long Point Bay | Long Point Bay Conservation Authority targeted sampling for species at risk in Long Point Bay, Long Point Region Conservation Authority (2009, 2010) | seine, fyke nets |

Yes

|

| Wellers Bay, West Lake, East Lake, Waupoos Bay | Fish community assessment, DFO (2009) | seine, backpack electrofishing unit |

Yes

|

| Wellers Bay, West Lake, East Lake, Waupoos Bay | Targeted sampling DFO (2009, 2010) | seine, backpack electrofishing unit |

Yes

|

| Wellers Bay, West Lake, East Lake, Waupoos Bay | Spotted gar targeted sampling (2009) |

No

|

|

| St. Lawrence River | Fish assemblage surveys, DFO/St. Lawrence Islands National Park (2005) | seine, boat electrofishing unit, fyke nets, minnow trap |

Yes

|

| St. Lawrence River | Nearshore fish community long-term monitoring program, PCA (2006 – 2011) | seine,boat electrofishing unit, fyke nets, minnow trap |

Yes

|

| St. Lawrence River | Fish assemblage survey, DFO (2004) | boat electrofishing unit |

No

|

| St. Lawrence River | Targeted sampling, DFO (2009, 2010) | seine |

Yes

|

| St. Lawrence River | Fish community survey, OMNR (annually) | gill nets |

No

|

1.7 Knowledge gaps

There are numerous aspects regarding the biology and ecology of the Pugnose Shiner that remain unknown. This information is required to refine recovery approaches and to aid in refining critical habitat identification. Threat clarification is required to determine the exact nature and extent of threats facing Pugnose Shiner. For example, the species has been recorded in regions affected by a suite of chemicals exceeding provincial and/or federal guidelines and the specific indirect/direct effects of these chemicals and their interactions with other stressors on Pugnose Shiner are not known (EERT 2008). Another source of uncertainty is the effect that the loss and deterioration of coastal and inland wetlands will have on the distribution of Pugnose Shiner and its abilities to move between and colonize new areas (Leslie and Timmins 2002; EERT 2008). The impacts of exotic fishes (e.g., Common Carp, Round Goby [Neogobius melanostomus]) on Pugnose Shiner and its habitat are unknown and require assessment.

2. Recovery

The following goals, objectives, and recovery approaches were adapted from the Essex-Erie Recovery Strategy (EERT 2008), which covers a substantial portion of the Canadian range of the Pugnose Shiner. Additional considerations were included from the Ausable River Recovery Strategy (ARRT 2006).

2.1 Recovery feasibility

The recovery of Pugnose Shiner is believed to be biologically and technically feasible. The following feasibility criteria8 have been met for the species:

- Are individuals capable of reproduction currently available to improve the population growth rate or population abundance?

Yes. Reproducing populations currently exist in the Old Ausable Channel, Long Point Bay (Lake Erie), Lake St. Clair, and the St. Lawrence River and could provide a basis for natural expansions and potential translocations or artificial propagation if necessary.

- Is sufficient suitable habitat available to support the species or could it be made available through habitat management or restoration?

Yes. Suitable habitat is present at several locations where extant populations exist, particularly the Old Ausable Channel, the area around Walpole Island (Lake St. Clair), Prince Edward County inland bays, and the St. Lawrence River (area near the Grenadier Island Wetland Complex). Improved water quality and habitat management (through stewardship and Best Management Practices [BMPs]) could restore suitable habitat in locations where populations have been extirpated or are in decline.

- Can significant threats to the species or its habitat be avoided or mitigated through recovery actions?

Yes. Threats believed to pose a serious risk to Pugnose Shiner, such as siltation/turbidity and the removal of aquatic vegetation, can be addressed through recovery actions. Identifying and remediating the sources of nutrients and suspended sediments affecting the health of occupied coastal wetlands will be critical to ensuring these habitats can continue to support Pugnose Shiner (EERT2008).

- Do the necessary recovery techniques exist and are they demonstrated to be effective?

Yes. Techniques to reduce identified threats (e.g., BMPs) and restore habitats are well known and have proven to be effective. Repatriations may be feasible through captive rearing or adult transfers. Although there are no published studies on captive rearing for Pugnose Shiner, these techniques have been successful for other freshwater cyprinids (e.g., DeMarais and Minckley 1993). Bryan et al. (2002) found that, although native predators influenced the behaviour of the Little Colorado Spinedace (Lepidomeda vittata) (a federally Threatened cyprinid in the U.S.), the presence of non-native predators had a greater impact on the species, and they recommended the control or elimination of non-native predators from the minnow’s established critical habitat or potential repatriation sites.

Removal of vegetation and site disturbance have been cited as the best documented causes for invasion of plant species, but general strategies and goals for wetland restoration can be derived at the ecoregion scale using information on current and historic wetland extent and type distributions (Detenbeck et al. 1999).

2.2 Recovery goal

The long-term (> 20 years) recovery goal for the Pugnose Shiner is to maintain self-sustaining population(s) at existing locations and restore self-sustaining population(s) to historic locations, where feasible.

2.3 Population and distribution objective(s)

COSEWIC assessed the Pugnose Shiner as Endangered in 2002, in part, because of its limited distribution. At the time of the report’s publication, Pugnose Shiner was considered extant at four locations in Canada and extirpated from two (Holm and Mandrak 2002). Since the publication of the COSEWIC report, eight new Pugnose Shiner locations have been confirmed extant and another location has been confirmed extirpated. Currently, the total number of confirmed Pugnose Shiner locations, both extant and extirpated, is 15.

An important factor to consider when determining population and distribution objectives is the number of populations that may be at a given location, as it is possible that a location may contain more than one discrete population. In this context, location does not refer to the locality of the discrete population, but rather a geographically or ecologically distinct area in which a single threatening event can rapidly affect all individuals of this species present (COSEWIC 2011).

To recover the species to a level lower than Threatened under COSEWIC criteria, a minimum of 11 extant locations with at least one self-sustaining population are required. Where present, multiple populations at a single location should be maintained. Currently, the number of populations present at each Pugnose Shiner location in Canada is unknown and further research is required to investigate this.

The population and distribution objective for the Pugnose Shiner is to ensure the persistence of self-sustaining population(s) at the 12 extant locations (Teeswater River, Old Ausable Channel, Mouth Lake, Lake St. Clair and tributaries, St. Clair National Wildlife Area, Canard River, Long Point Bay/Big Creek, Wellers Bay, West Lake, East Lake, Waupoos Bay, and the St. Lawrence River [between Eastview and Mallorytown Landing, including the St. Lawrence Islands National Park]) and restore self-sustaining population(s) in Rondeau Bay, Point Pelee National Park, and the Gananoque River, where feasible.

Recent modelling conducted by Venturelli et al. (2010) estimated that the minimum viable population size (MVP) for Pugnose Shiner is 14 325 adults, given a 10% chance of a catastrophic event occurring per generation. However, the implementation of such a target is difficult without also having information on population(s) size, trends, and spatial distribution, as well as habitat quality. This information is mostly lacking for the majority of Pugnose Shiner locations in Canada. Further research is required to validate the model results. More quantifiable objectives relating to MVP can be developed and the recovery goal refined if abundance information is obtained.

2.4 Recovery objectives

In support of the long-term goal, the following short-term recovery objectives will be addressed over the next 5 -10 years:

- Refine population and distribution objectives;

- Refine and protect critical habitat;

- Determine long-term population and habitat trends;

- Evaluate and minimize threats to the species and its habitat;

- Investigate the feasibility of population supplementation or repatriation for populations that may be extirpated or reduced;

- Enhance efficiency of recovery efforts through coordination with aquatic and terrestrial ecosystem recovery teams and other relevant or complementary groups/initiatives; and,

- Improve overall awareness of the Pugnose Shiner and the role of healthy aquatic ecosystems, and their importance to humans.

2.5 Approaches recommended to meet recovery objectives

2.5.1 Recovery planning

There are three broad approaches, outlined in Tables 5 - 7, that are recommended to meet recovery objectives: Research and Monitoring (Table 5); Management and Coordination (Table 6); and, Stewardship, Outreach, and Awareness (Table 7). The tables include a priority rank (urgent, necessary, beneficial), a reference to the recovery objectives to be addressed (listed above), a list of the broad approaches to address threats, a description of the threat addressed, specific steps to be taken, and suggested outcomes or deliverables to measure progress. A narrative is included after each table when further explanation is required with respect to a specific approach.