Sixth Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying in Canada

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 8.05 MB, 95 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Published: November 2025

Table of contents

- Highlights

- Minister's message

- 1. Introduction and overview

- 2. MAID requests and outcomes

- 3. MAID assessments: grievous and irremediable medical conditions

- 4. Socio-demographic considerations, access and inequality

- 5. Social supports and use of health services

- 6. MAID providers and delivery

- 7. Conclusion

- Appendix A: MAID eligibility criteria, safeguards and reporting requirements

- Appendix B: Methodology and limitations

- Appendix C: Profile of MAID by province and territory

- Appendix D: MAID requests, eligibility and procedural requirements

Highlights

Medical assistance in dying (MAID) is a health service delivered by provincial and territorial health systems as part of end-of-life care, within a federal legal framework that sets out strict criteria around who can receive MAID and under what conditions. It has been allowed in Canada since 2016, when the Parliament of Canada passed federal legislation that allows eligible adults in Canada to request MAID. The federal legal framework for MAID is set out in the Criminal Code which establishes strict eligibility criteria and safeguards.

This Sixth Annual Report provides a summary of MAID requests, assessments and provisions across Canada for the 2024 calendar year. This information is provided to Health Canada by provincial and territorial health officials as well as by physicians, nurse practitioners, pharmacists and pharmacy technicians. The Sixth Annual Report marks the second full year of data collection under the amended Regulations for the Monitoring of Medical Assistance in Dying, which came into force on January 1, 2023. The report provides important insight into who requests and receives MAID, and how it is delivered. While data quality and comprehensiveness is improving, there are still important data limitations to consider: the ability to present trends over time is limited, as is the quality and reliability of self-identification measures on race, Indigenous identity, and disability.

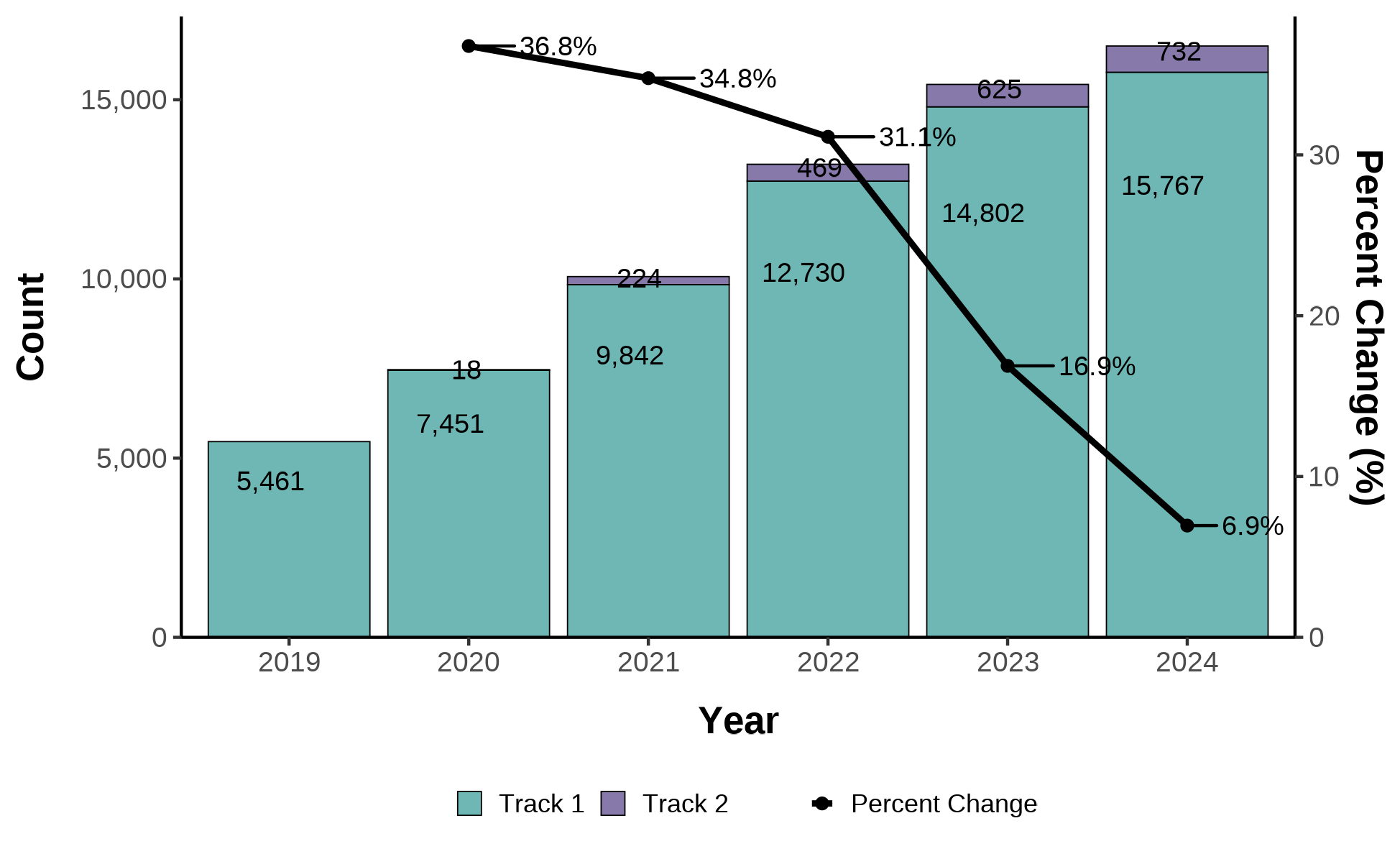

While the total number of MAID provisions increased in 2024, the rate of growth decreased substantially, consistent with the trend from 2023. (See section 2)

- This report details 22,535 reports of MAID requests that Health Canada received in 2024. A total of 16,499 people received MAID; the remaining cases were requests that did not result in a MAID provision (4,017 died of another cause, 1,327 individuals were deemed ineligible and 692 individuals withdrew their request).

- The annual rate of growth in the number of MAID provisions has decreased significantly over the past several years, from 36.8% between 2019 and 2020 to 6.9% between 2023 and 2024.

- These findings seem to suggest that the number of annual MAID provisions is beginning to stabilize. However, it will take several more years before long-term trends can be conclusively identified.

The vast majority of people receiving MAID in 2024 had a reasonably foreseeable death. (See section 2)

- A person whose death is "reasonably foreseeable" (i.e., they are close to death) is referred to as "Track 1" These made up 95.6% of MAID provisions.

- "Track 2" refers to MAID recipients who were assessed as having a natural death that was not "reasonably foreseeable". These made up a small minority of MAID provisions (4.4%).

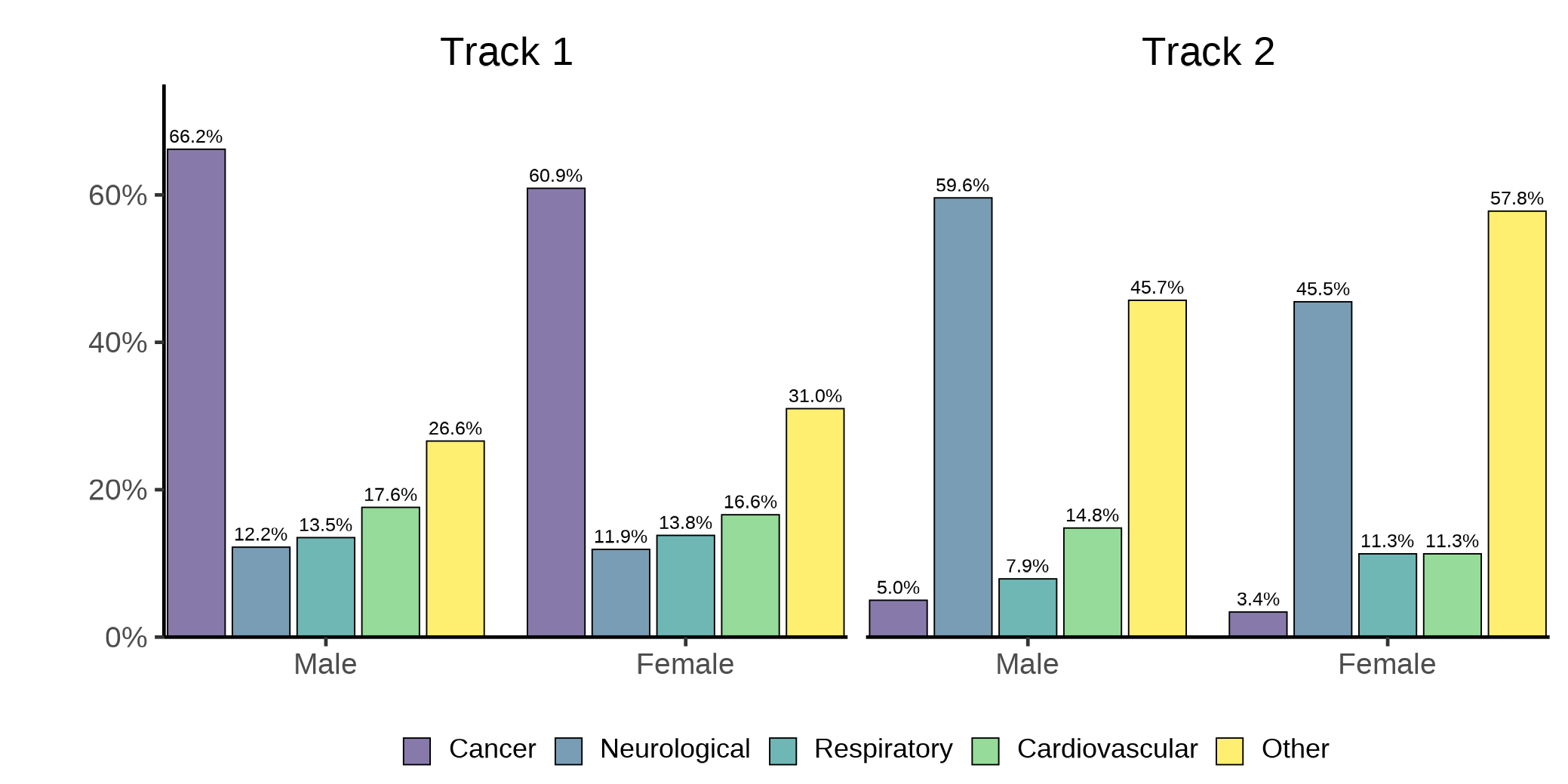

Consistent with 2023 findings, those who received MAID under Track 1 were older, and more likely to have cancer as an underlying medical condition. (See section 3)

- The median age of individuals receiving MAID under Track 1 was 78.0 years, and 60.9% were over 75 years of age.

- A slightly greater percentage were men (52.2%) than were women (47.8%).

- Cancer was the most frequently reported underlying medical condition, cited in 63.6% of cases.

Consistent with 2023 findings, those receiving MAID under Track 2 were predominantly women, slightly younger, and lived with their illness for a much longer period of time. (See section 3)

- The median age was 75.9 years, and 53.5% were over 75 years of age.

- A greater percentage were women (56.7%) while 43.3% were men. This represents a small narrowing of the gap between women and men when compared to 2023 (when 58.5% were women and 41.5% were men). This is also consistent with overall population health trends where women are more likely to experience long-term chronic illness, which can cause enduring suffering but would not typically make a person's death reasonably foreseeable.

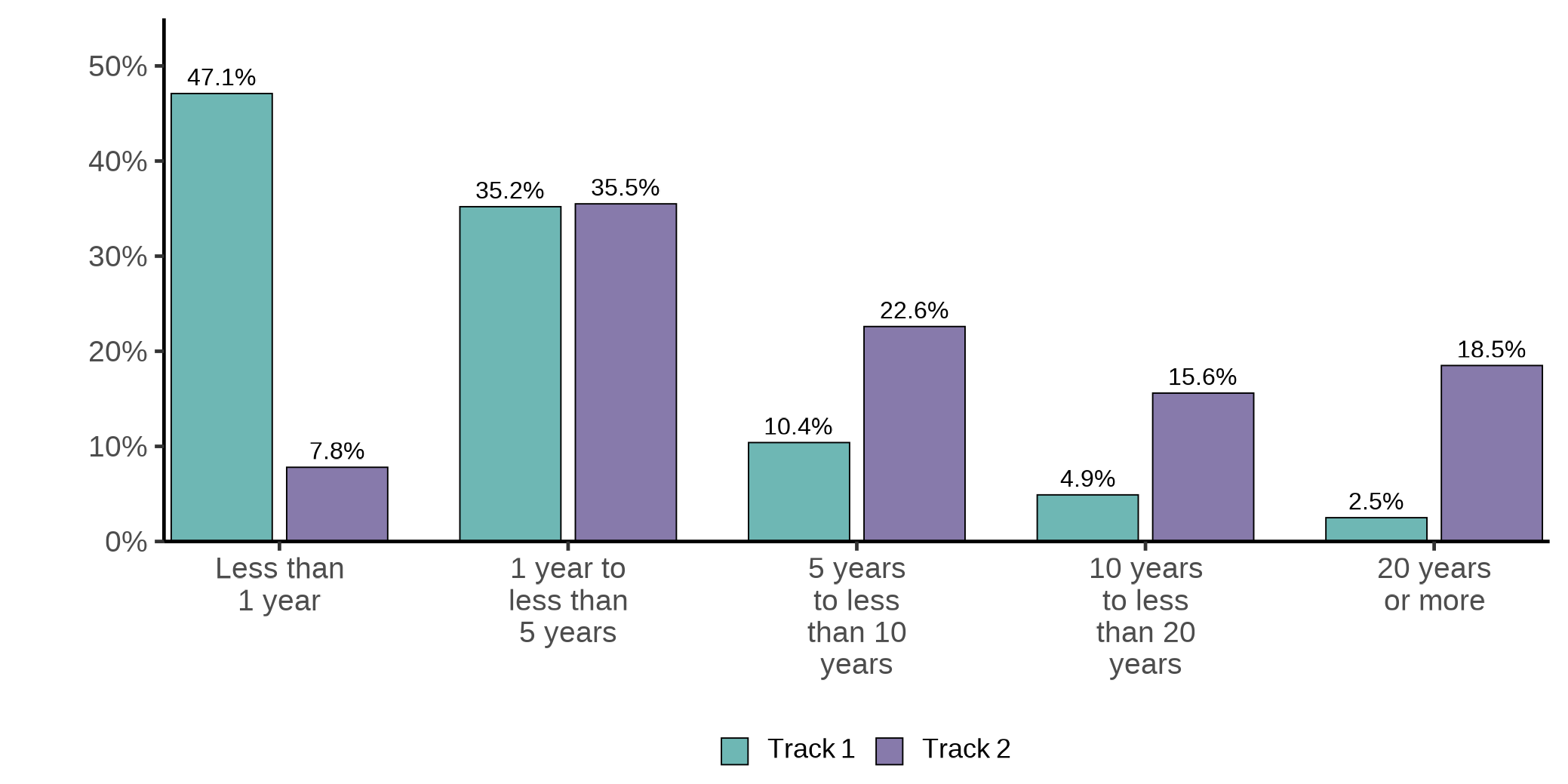

- People assessed under Track 2 lived longer with a serious and incurable condition than those assessed under Track 1: 34.1% of those under Track 2 lived with a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability for more than 10 years, compared to 7.4% of those under Track 1.

- Neurological conditions and "other" conditions (such as diabetes, frailty, autoimmune conditions, chronic pain) were the most commonly cited underlying medical conditions.

The number of people assessed as being ineligible in 2024 was proportionally much higher for Track 2 than for Track 1. (See section 2)

- Although Track 2 provisions represented 4.4% of MAID cases in 2024, they represented close to a quarter (24.2%) of all MAID requests that were assessed as ineligible.

More people in 2024 who received MAID responded to self-identification questions on race and Indigenous identity, but findings are still subject to limitations. (See section 4)

- A total of 15,927 people who received MAID responded to the question on racial, ethnic or cultural identity. The vast majority (95.6%) identified as Caucasian (White). The second most commonly reported racial, ethnic or cultural identity was East Asian (1.6%). These percentages are close to those reported for 2023 (95.8% Caucasian; 1.8% East Asian).

- A total of 16,115 people who received MAID in 2024 responded to the question on Indigenous identity: 102 people self-identified as First Nations, 57 people self-identified as Métis and 7 people self-identified as Inuit.

- As provinces and territories have varied approaches to collecting information on these questions and individuals may be reluctant to self-identify, conclusions on the basis of these data alone are limited.

Similar to 2023, a much smaller proportion of people receiving MAID under Track 1 reported having a disability compared to people receiving MAID under Track 2. (See section 4)

- Compared to 2023, far more people who received MAID responded to the self-identification question on disability, with over 97% of MAID recipients responding to this question in 2024. A total of 16,104 people who received MAID responded this question, with 5,295 (32.9%) self-identifying as having a disability.

- A smaller proportion (31.6%) of Track 1 respondents self-identified as having a disability compared to 61.5% of Track 2 respondents.

- Under Track 1, the share of people self-reporting having a disability increased with age.

- Under Track 2, the largest proportion of people who self-reported having a disability was in the 75 to 84 age group; the share declines again among those aged 85 and older.

- Under Track 1, slightly more men (50.8%) than women (49.2%) self-reported having a disability.

- Under Track 2, proportionally more women (55.6%) than men (44.4%) self-reported having a disability, which aligns closely with 2023 data, as well as with disability trends among the general population of Canada.

- While these findings provide some insight into MAID provisions among persons identifying as having a disability, the completeness of the data varies across the country, and differing definitions of disability may have been used in some instances. As such, findings should be interpreted with caution.

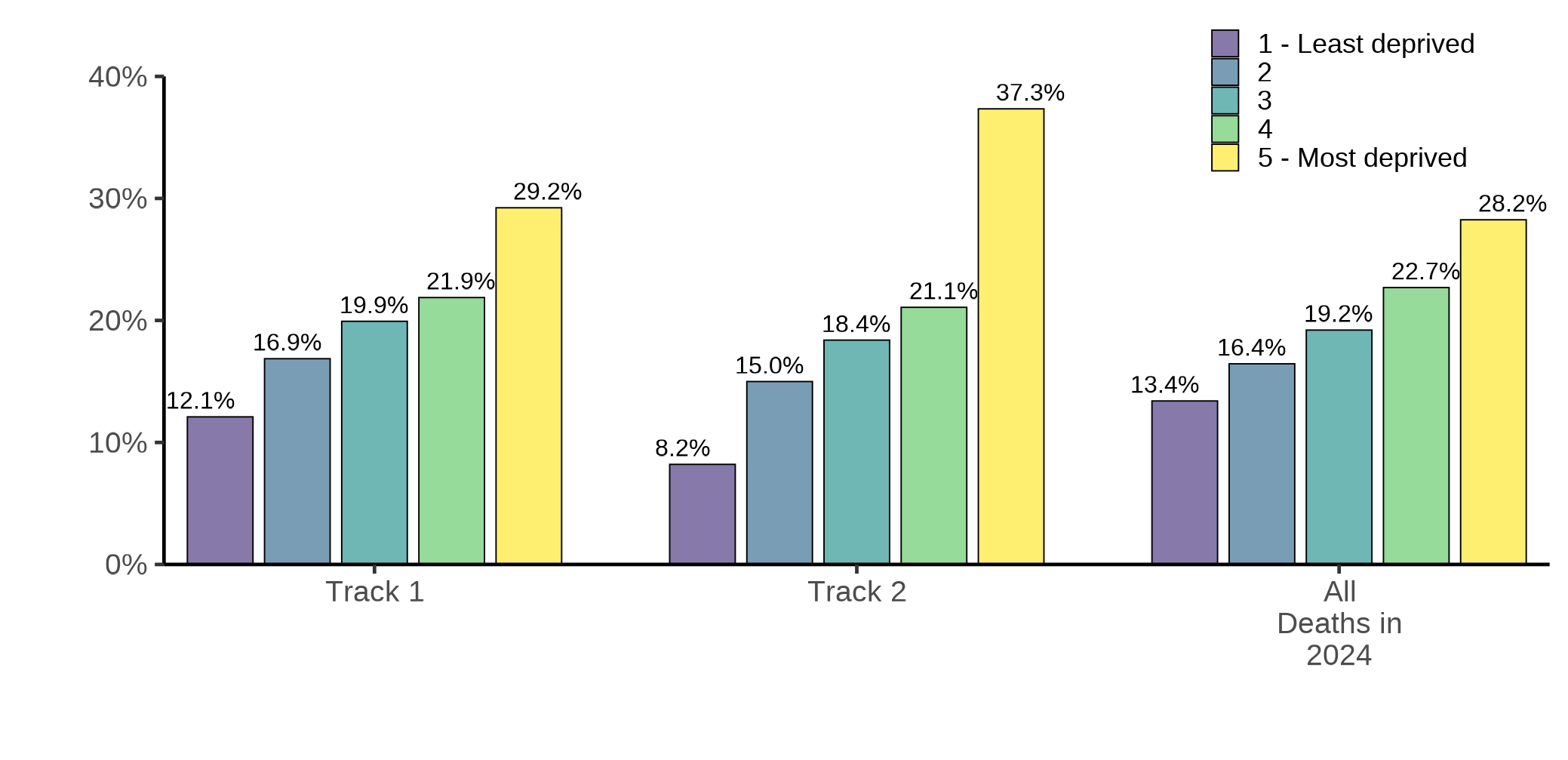

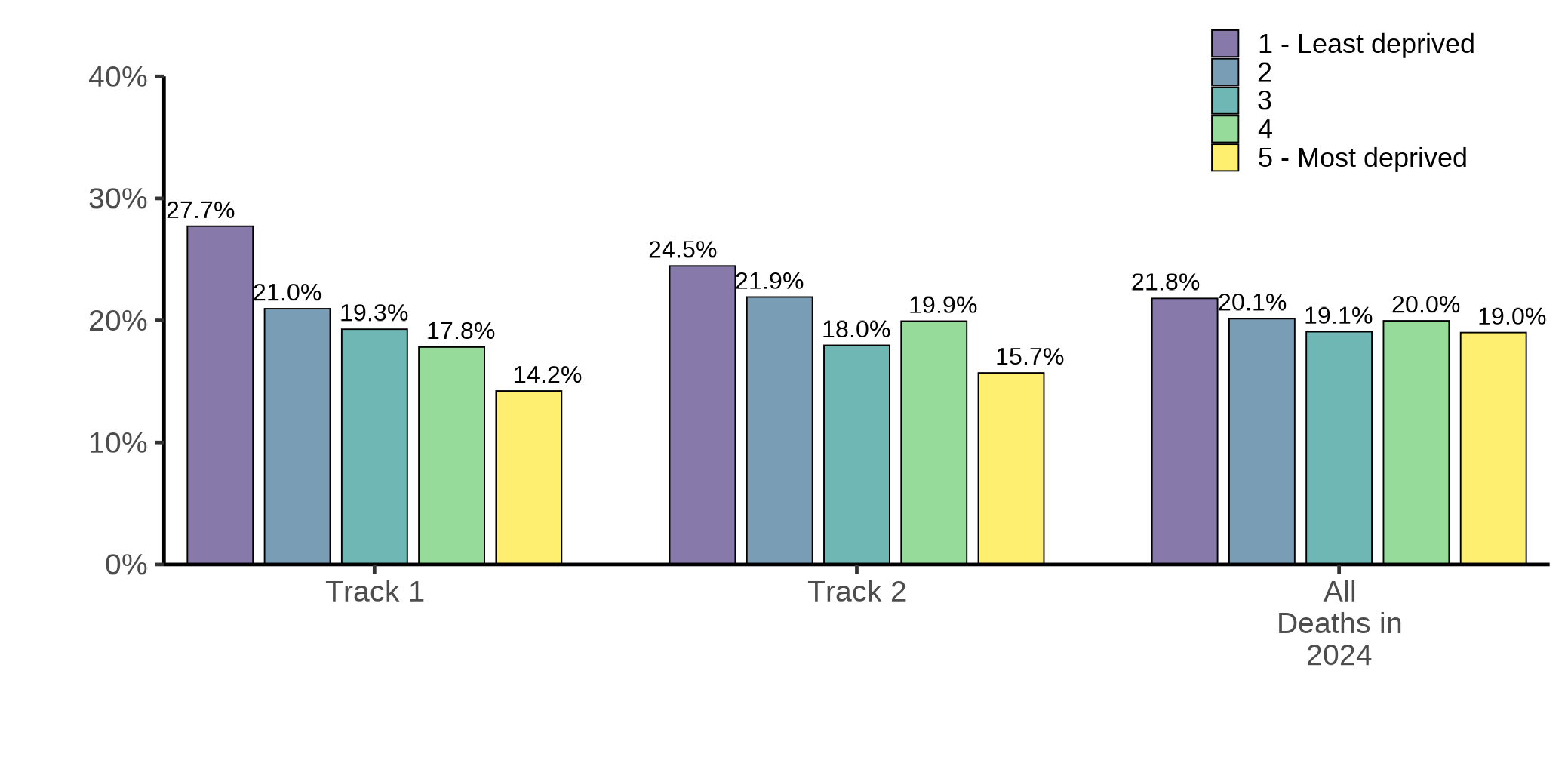

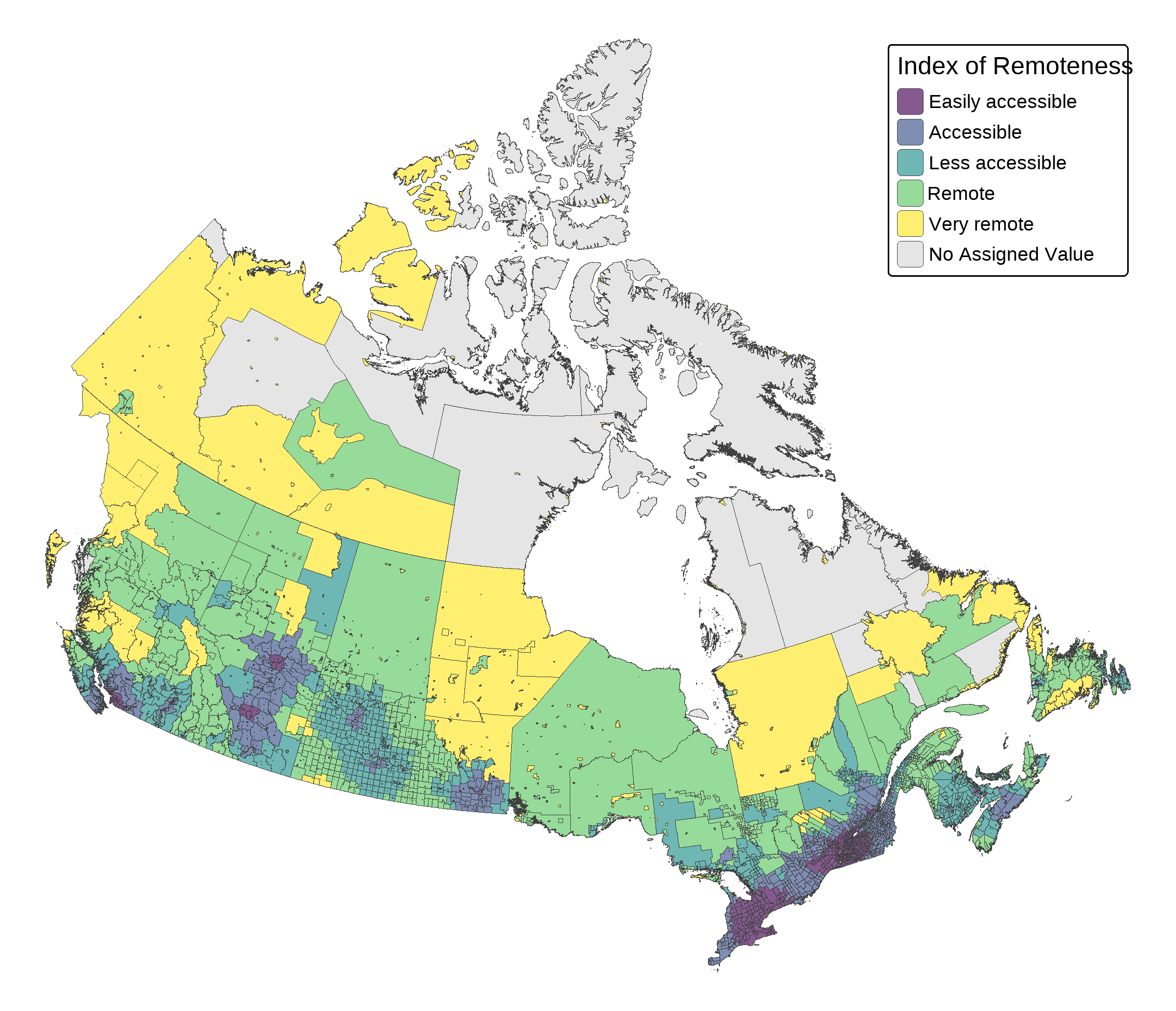

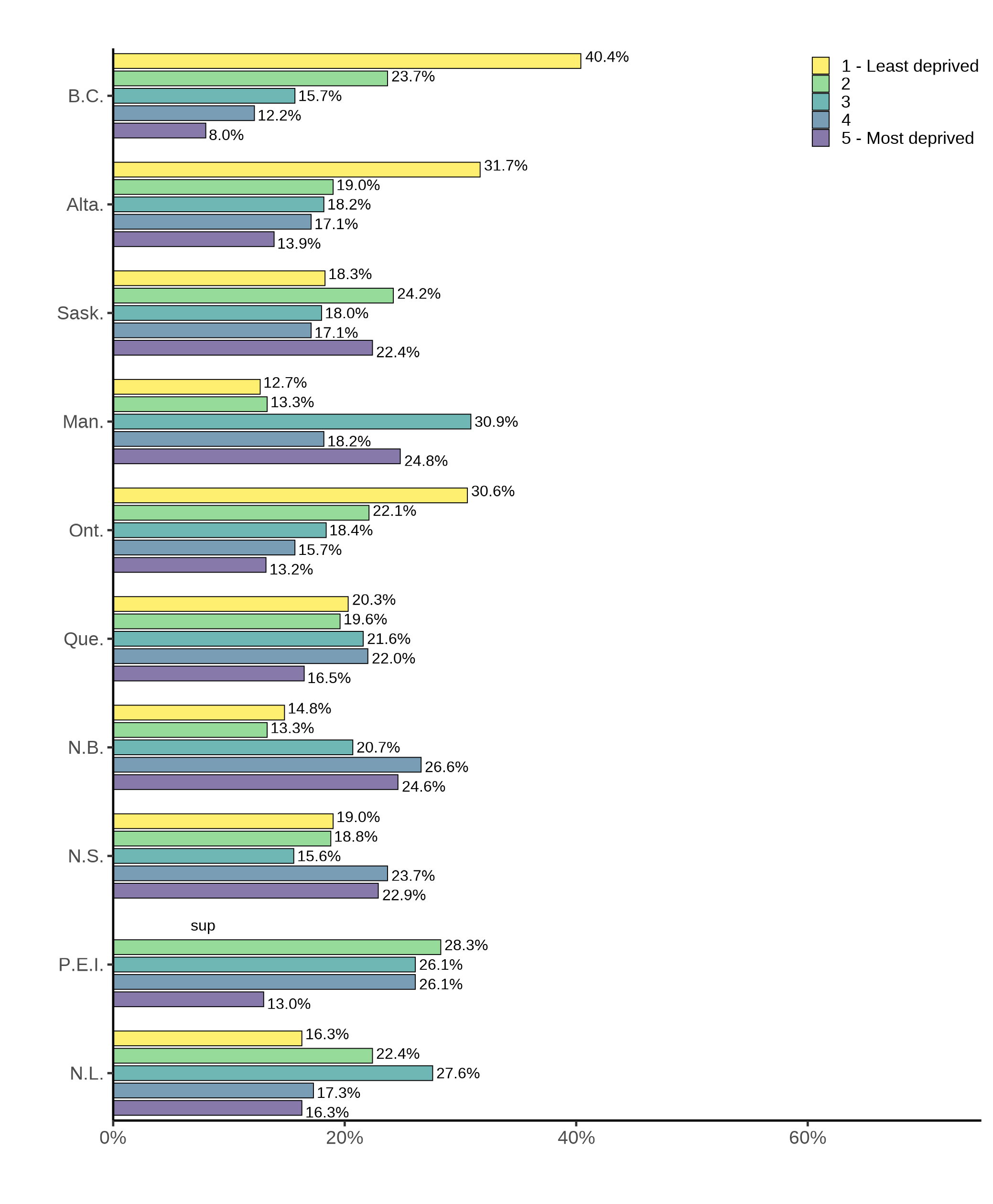

Health Canada replicated the socio-economic and community analyses done in the Fifth Annual Report and did an analysis on remoteness to continue to better understand the circumstances of people receiving MAID, which resulted in similar findings. (See section 4).

- Findings from socio-economic and community analyses suggest, at a high level, that people who receive MAID do not disproportionately come from lower-income or disadvantaged communities.

- Findings on remoteness show that MAID recipients were typically less likely to live in a remote location. This may suggest that they did not seek MAID due to lack of accessibility to health care services or services that promote health. It may also reflect challenges accessing MAID in remote locations.

- These analyses are based on neighbourhood-level measures and do not speak to the situation of the MAID recipients themselves. As such, they should be interpreted with caution.

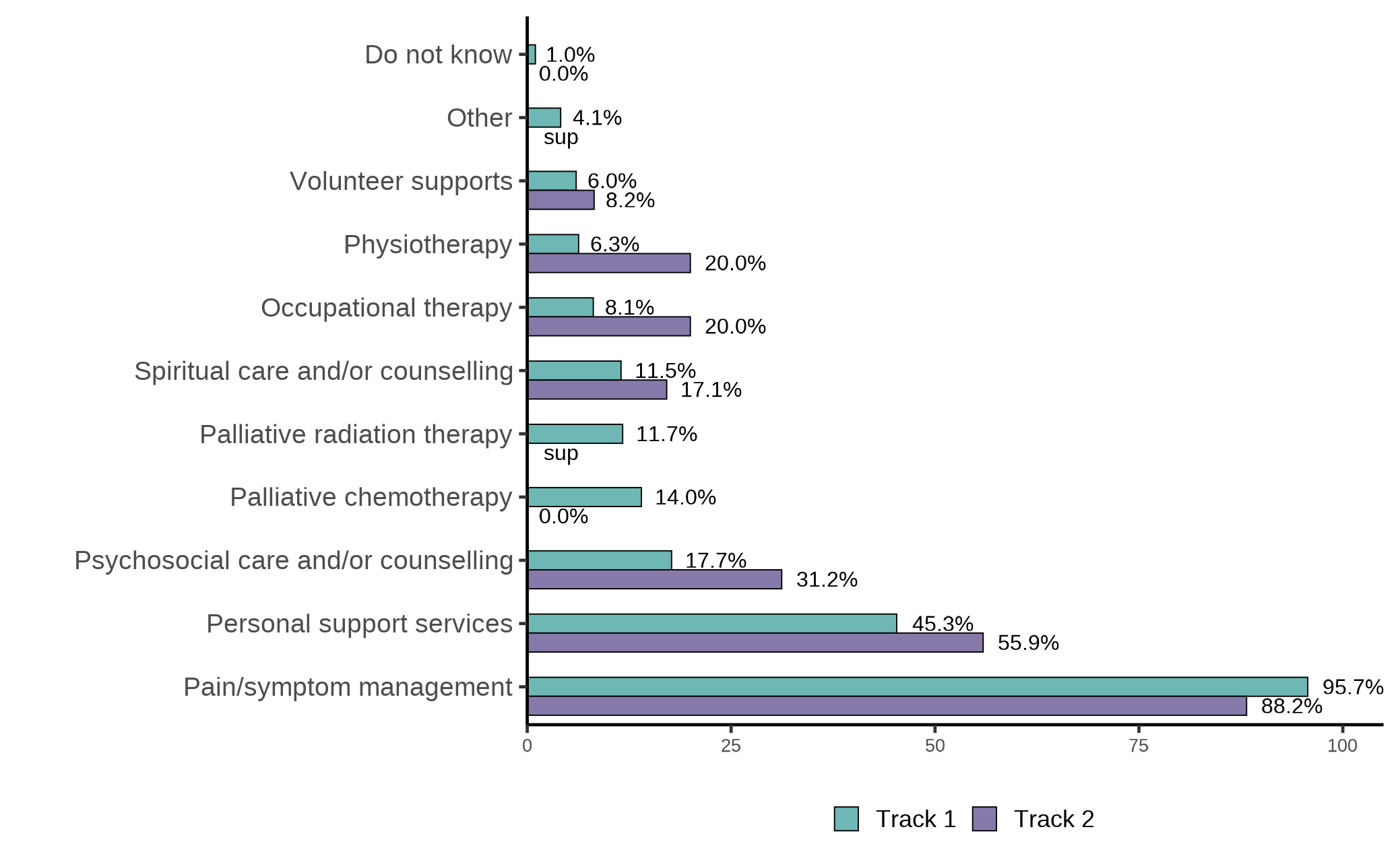

Consistent with previous years, most MAID recipients who required either palliative care or disability support services received these services. (See section 5)

- Nearly three-quarters (74.1%) received palliative care; 76.4% of people who received MAID under Track 1 received palliative care, compared to 23.2% of people who received MAID under Track 2.

- A small proportion (2.5%) required, but did not receive, palliative care services; of these individuals, 91.2% confirmed that services were accessible to them.

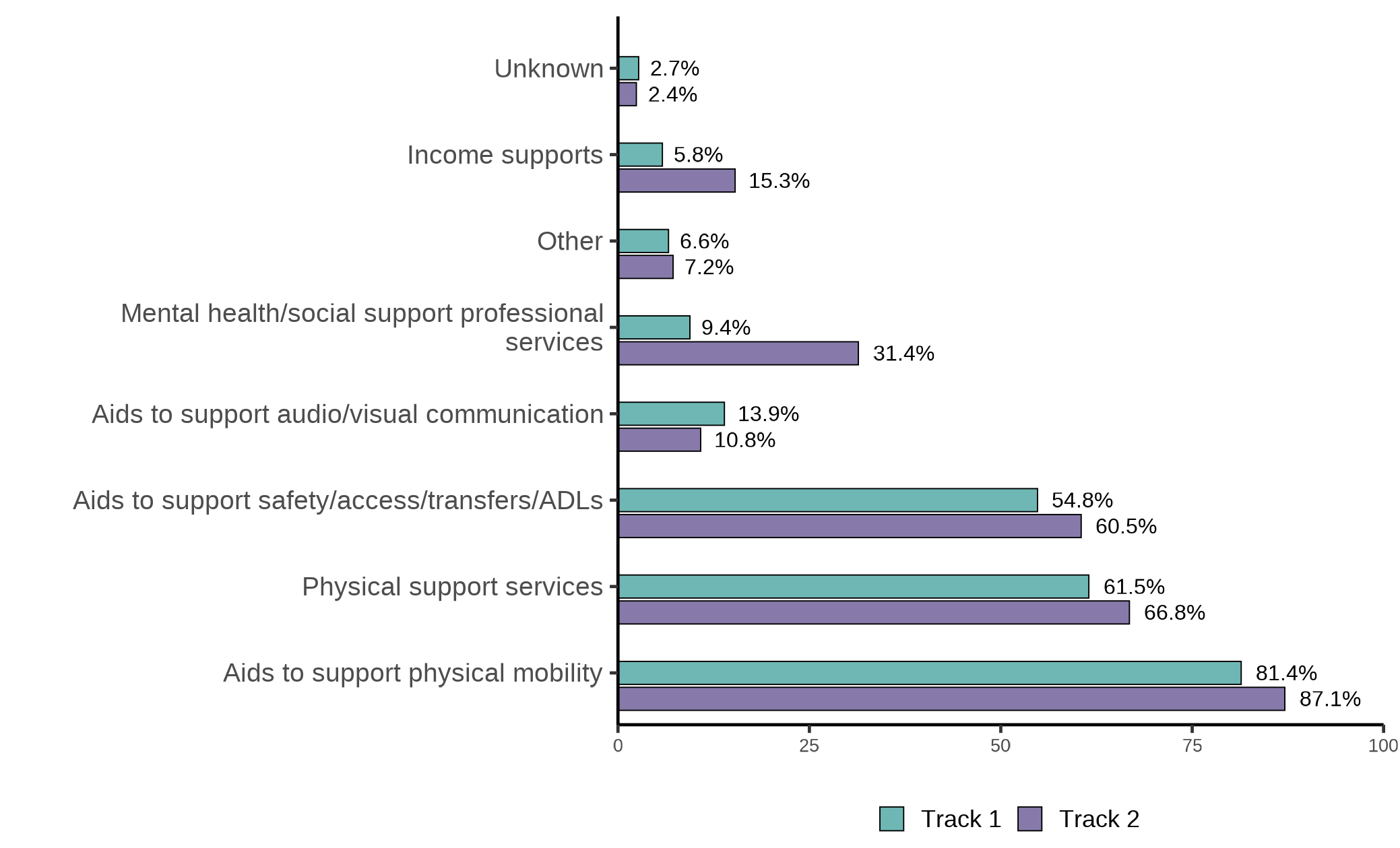

- Close to one-third (32.5%) received disability support services; 32.0% of people who received MAID under Track 1 received disability support services, compared to 45.5% of people under Track 2.

- A very small proportion (0.1%) required, but did not receive, disability support services; of these individuals, 91.4% confirmed that services were accessible to them.

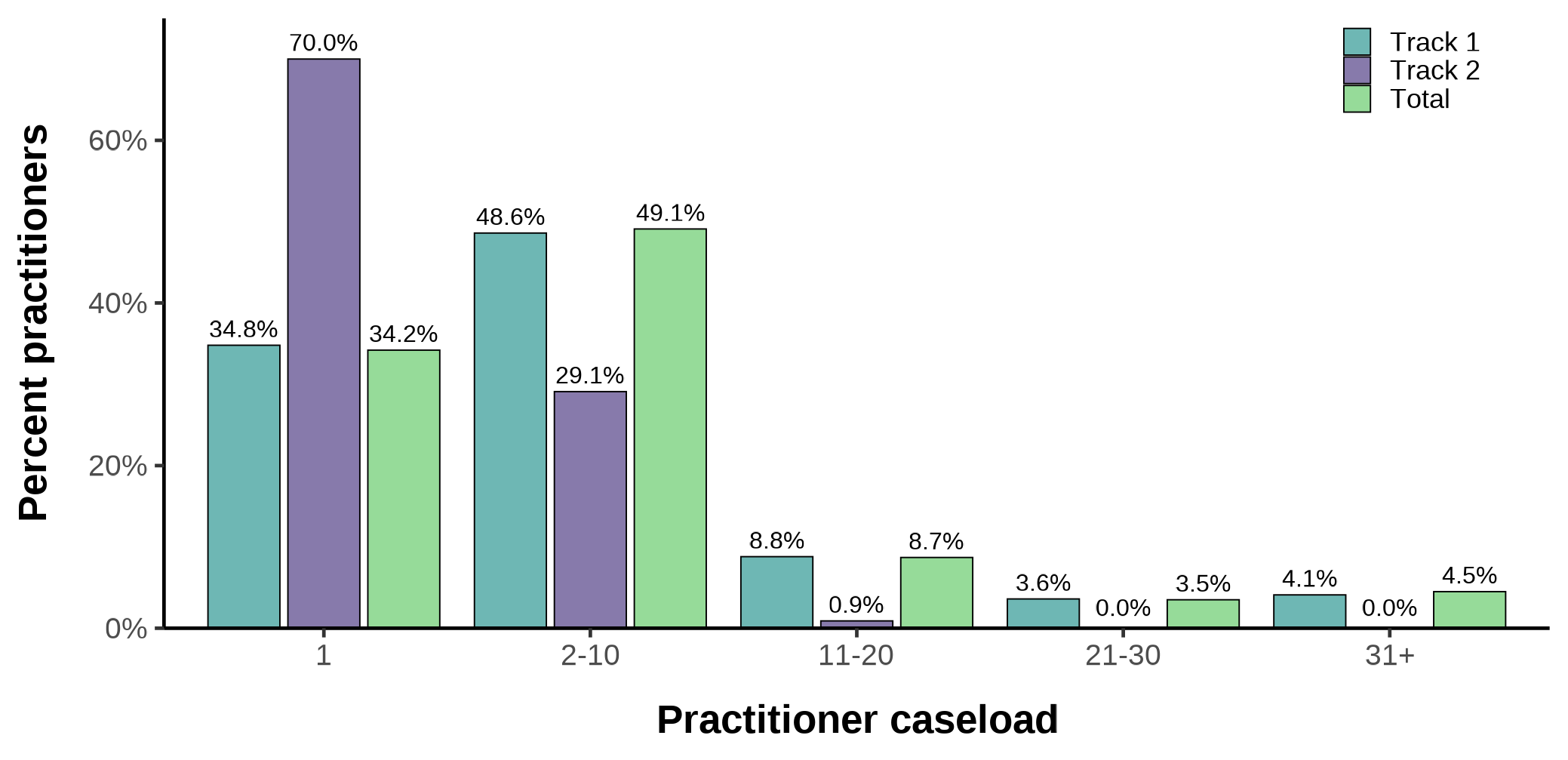

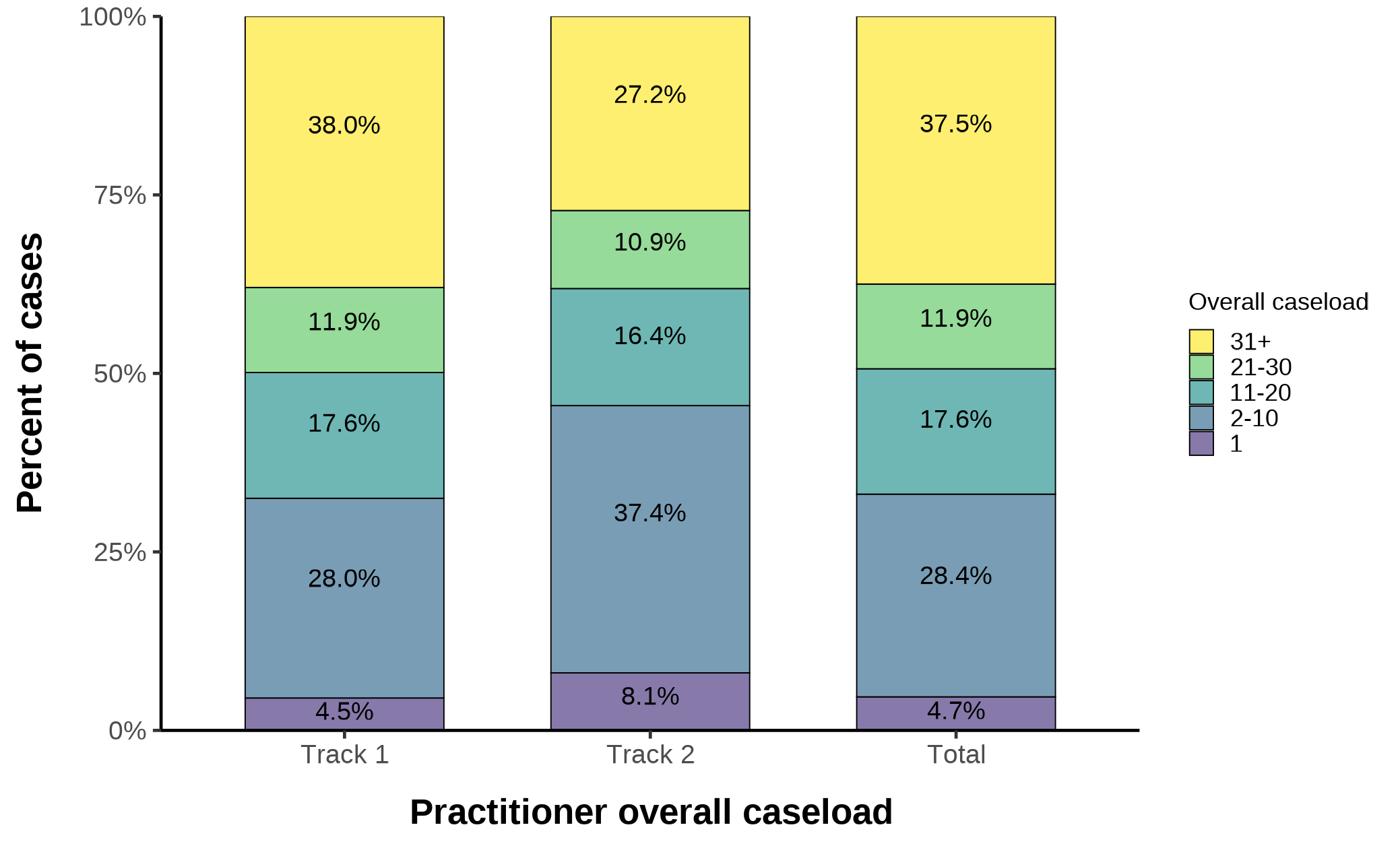

While there is a small number of practitioners doing a large share of MAID provisions, these practitioners are not typically taking on a great number of Track 2 cases. (See section 6)

- There were 2,266 unique MAID practitioners in 2024. The majority (93.2%) were physicians, while 6.8% were nurse practitioners.

- A small number of MAID practitioners (n=102) was responsible for 38.0% of all Track 1 cases and 27.2% of all Track 2 cases. The vast majority of these practitioners did fewer than 11 Track 2 provisions; less than five of these practitioners did between 11 and 20 Track 2 MAID provisions and none did more than 20 Track 2 MAID provisions.

Minister's message

As Minister of Health, I am pleased to share Health Canada's Sixth Annual Report on Medical Assistance in Dying (MAID). This report shows our commitment to providing accurate information about MAID and being open and transparent about how it is delivered across Canada.

After the Supreme Court's decision in 2015, which found that the absolute prohibition of MAID was against the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Parliament created Canada's legal rules for MAID in 2016. These rules are in the Criminal Code and include strict eligibility criteria and robust safeguards for accessing MAID.

Since the introduction of MAID, federal, provincial, and territorial governments have worked together to ensure it is provided safely. Provinces and territories manage health care, and they continue to improve how MAID is delivered. Health officials meet regularly to share best practices and discuss issues like data collection, quality improvement, and handling complex MAID cases. Supporting this effort, organizations such as the Canadian Association of MAID Assessors and Providers have shared best practices and developed tools and resources, including Canada's first nationally accredited bilingual education program for MAID. Additionally, a group of clinicians and experts, with support from Health Canada, created the Model Practice Standard for MAID and a companion document to guide health professional regulators. Together, these initiatives help ensure MAID services are safe and protect the public, especially in complex cases.

At the same time, Canadians continue to have thoughtful and personal conversations about autonomy and compassionate care for people with serious illnesses. These discussions help us to understand how to best support individuals, families, and health care providers navigating complex and incurable illnesses.

This year's report builds on these efforts by providing valuable insights into the experiences of people requesting MAID. It includes information about disability, race, Indigenous identity, and access to health and social services, helping us to better understand the role of MAID in our health care system. The report also highlights the dedication of health care professionals who provide MAID with compassion and respect for individual choice.

Looking ahead, we remain focused on making sure MAID meets the needs of those seeking this service. We are committed to ensuring that the federal legal framework protects those who are vulnerable, while supporting freedom of choice and personal autonomy. Health Canada will continue working with provincial and territorial health systems, experts, stakeholders, Indigenous partners, and members of the public to ensure MAID is delivered in a manner that is safe, appropriate, respectful, inclusive, and grounded in human dignity.

I invite people in Canada to read this report and to reflect on its findings. Together, we can continue to be guided by the evidence when considering complex issues such as suffering and death and the compassionate approaches that support individuals to make informed choices about their care.

The Honourable Marjorie Michel, P.C., M.P.

Minister of Health

1. Introduction and overview

1.1 Introduction

MAID is a topic that generates considerable interest, public discussion and debate, both internationally and within Canada. As we near ten years of MAID in Canada, this Sixth Annual Report is intended to contribute to greater insight and understanding of MAID services in Canada to inform ongoing conversations globally and nationally about end-of-life care.

This report presents the most current summary of MAID assessment and provision in Canada. It presents data reported for the 2024 calendar year, collected under the amended Regulations for the Monitoring of Medical Assistance in Dying, Footnote 1which came into force on January 1, 2023. These regulations align with the federal legislation on MAID, as outlined in the Criminal Code.

1.2 How the data are presented

To protect confidentiality, Health Canada does not present findings when there are fewer than five cases due to the risk that an individual or small groups of individuals could be identified (for instance, if reviewed in conjunction with other publicly available data, such as those presented within this report or at the provincial/territorial level). Data points representing more than five cases may also be suppressed if they would have otherwise provided enough information to calculate the number of cases in another group where the number of cases is too small to report without putting confidentiality at risk. Data that are suppressed for confidentiality purposes are notated with an "X" throughout the report.

Health Canada uses the median as a measure of central tendency Footnote 2 throughout this report to summarize variables such as age and number of days or years. This was a deliberate decision, as the median provides a more robust measure compared to the mean, which is more sensitive to outlying values.

This year's report marks the second full year of data collection under the current regulations, which introduced several new reporting requirements for health care practitioners to align with the legislative changes enacted in 2021. Footnote 3 To the extent possible, data are presented by the "track" under which MAID was provided as follows:

- Track 1: Refers to a request for MAID made by a person who meets the eligibility requirements set out in the Criminal Code and whose natural death is "reasonably foreseeable"

- Track 2: Refers to a request for MAID made by a person who meets the eligibility requirements set out in the Criminal Code and whose natural death is not "reasonably foreseeable" (these requests are subject to several additional safeguards in order to dedicate sufficient time and expertise to assessment).

Appendix A provides further information on the eligibility criteria for MAID, the safeguards for Tracks 1 and 2, and the reporting requirements that practitioners are obligated to follow.

In reviewing this report, it is important to keep in mind the following:

- The ability to present trends over time is limited for some variables: given that several reporting requirements and questions have recently been updated, there are instances where data collected in 2023 and 2024 are not fully comparable with the data collected in previous years.

- The quality and reliability of the self-identification data (race, Indigenous identity, and disability) is limited due to variation in data collection approaches, inconsistency in interpretation of variables and potential reluctance on part of the person to self-identify.

Appendix B provides further details with respect to the methodology and limitations.

With the above limitations in mind, the comprehensiveness of the data is improving. It was noted in last year's annual report that, in some cases, provinces, territories and practitioners experienced delays in transitioning to the new data collection requirements, resulting in some missing data for new variables. Since then, the amount of missing data has decreased substantially, as demonstrated later in the report throughout section 4.

A dedicated working group of provincial and territorial officials is working with Health Canada to make continuous improvements to data collection, consistency and quality.

Health Canada is grateful for the partnership and collaboration among federal, provincial, and territorial levels of government, MAID practitioners and pharmacists, Indigenous partners and key stakeholders. This partnership and collaboration has enabled the collection and validation of the data and supported the analyses in this report.

2. MAID requests and outcomes

2.1 MAID requests and outcomes

In 2024, Health Canada received 22,535 reports of MAID requests. As outlined in Table 2.1a, of these requests, a total of 16,499 people received MAID. The remaining requests did not result in a MAID provision (4,017 died of another cause, 1,327 individuals were assessed as being ineligible and 692 individuals withdrew their request).

Note that it is possible that a person is included in these groups more than once (for example, a person could request MAID, withdraw their request and then apply again and receive it, or make several requests for MAID which are all each deemed ineligible). All MAID requests that were resolved in 2024 were included in this report ("resolved" is defined as a request that results in a MAID provision, is withdrawn, where the individual is found to be ineligible, or where the person has died).

| Requests or provisions | All cases | Track 1 | Track 2 | Did not assess track | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Count | Percent (%) | Count | Percent (%) | Count | Percent (%) | |

| MAID provisions in 2024 | 16,499 | 15,767 | 95.6 | 732 | 4.4 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Requests where individual was deemed ineligible in 2024 | 1,327 | 587 | 44.2 | 321 | 24.2 | 419 | 31.6 |

| Requests where individual died of another cause in 2024 | 4,017 | 3,643 | 90.7 | 64 | 1.6 | 310 | 7.7 |

| Requests that were withdrawn in 2024 | 692 | 402 | 58.1 | 116 | 16.8 | 174 | 25.1 |

| Total | 22,535 | 20,399 | NA | 1,233 | NA | 903 | NA |

Note: In previous years, requests not resulting in MAID (i.e., withdrawn requests, requests where the individual was found to be ineligible and requests followed by a natural death, rather than MAID) were classified based on the date the request was made by the person. This approach was suitable for Track 1 MAID cases, as assessments were typically completed within a short time frame and outcomes were reported within the same calendar year. However, Track 2 cases often involve much longer and more complex assessments that may span several months or even years. As such, Health Canada has revised its methodology. Beginning this year, all non-MAID outcomes (both Track 1 and 2) reported within a given calendar year will be counted in that year's statistics, regardless of when the initial request was made.

For MAID provisions, reporting continues to be based on the year the procedure took place, consistent with previous annual reports. In the event that MAID provisions are reported late, the totals for the relevant prior year are updated accordingly.

2.2 MAID provisions

Based on data from previous reports, there have been 76,475 MAID provisions in Canada since the legalization of MAID in 2016. Footnote 4 Figure 2.2a presents the number of MAID provisions from 2019 to 2024, as well as the year over year growth rate. In 2024, while the total number of MAID provisions increased, the year-over-year growth rate decreased. MAID was provided to 16,499 individuals in 2024, representing an increase of 6.9% over 2023. The rate of growth in overall MAID cases has been shrinking since 2019.

While Track 2 has only be allowed since 2021, when looking at Track 2 MAID provisions specifically, the rate of growth has decreased from 33.3% between 2022 and 2023 to 17.1% between 2023 and 2024.

While the data suggests that the number of annual MAID provisions is beginning to stabilize, it will take several more years before long-term trends can be conclusively identified.

Figure 2.2a - Text description

| Year | Track 1 | Track 2 | Total | Percent change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 5,461 | NA | 5,461 | NA |

| 2020 | 7,451 | 18 | 7,469 | 36.8 |

| 2021 | 9,842 | 224 | 10,066 | 34.8 |

| 2022 | 12,730 | 469 | 13,199 | 31.1 |

| 2023 | 14,802 | 625 | 15,427 | 16.9 |

| 2024 | 15,767 | 732 | 16,499 | 6.9 |

Explanatory notes:

- MAID provisions are counted in the calendar year in which the death occurred (i.e., January 1 to December 31) and are not related to the date of receipt of the written request.

- Prior to the passage of former Bill C-7 in 2021, MAID for individuals whose natural death was not reasonably foreseeable was permitted in Quebec via court exemption beginning March 12, 2020. Quebec reported 18 such MAID provisions in 2020.

- Previous years' reporting has been revised to include corrections and additional reports.

In 2024, 5.1% of people in Canada who died received MAID, a small (0.4%) increase from 2023. This percentage may change with final counts of deaths in Canada from Statistics Canada.

MAID is not classified as a cause of death by the World Health Organization, which sets international standards on data collection related to the classification of disease. As stated by the World Health Organization, a "cause of death" is the disease or injury that initiated the train of events leading directly to death, or the circumstances of the accident or violence which produced the fatal injury.Footnote 5

MAID, by contrast, is a health service provided as part of end-of-life or complex care, which a person can access in very limited circumstances (i.e., if they meet the strict eligibility criteria outlined in the legislation, including having a "grievous and irremediable medical condition," described in greater detail in section 3.1). For example, if a person suffering from advanced cancer chooses to receive MAID to alleviate their suffering, the cause of death extracted from their death certificate for the purposes of vital statistics will be cancer.

Accordingly, the number of MAID provisions should not be compared to cause of death statistics in Canada in order to determine the prevalence (the proportion of all decedents) nor to rank MAID as a cause of death. See Appendix B for more detail.

In 2024, 95.6% of MAID cases (n=15,767) were individuals whose death was reasonably foreseeable (Track 1) and 4.4% (n=732) were individuals whose death was not reasonably foreseeable (Track 2). This is consistent with findings from 2023, when Track 1 provisions made up 95.9% of MAID cases and Track 2 provisions made up 4.1% of MAID cases.

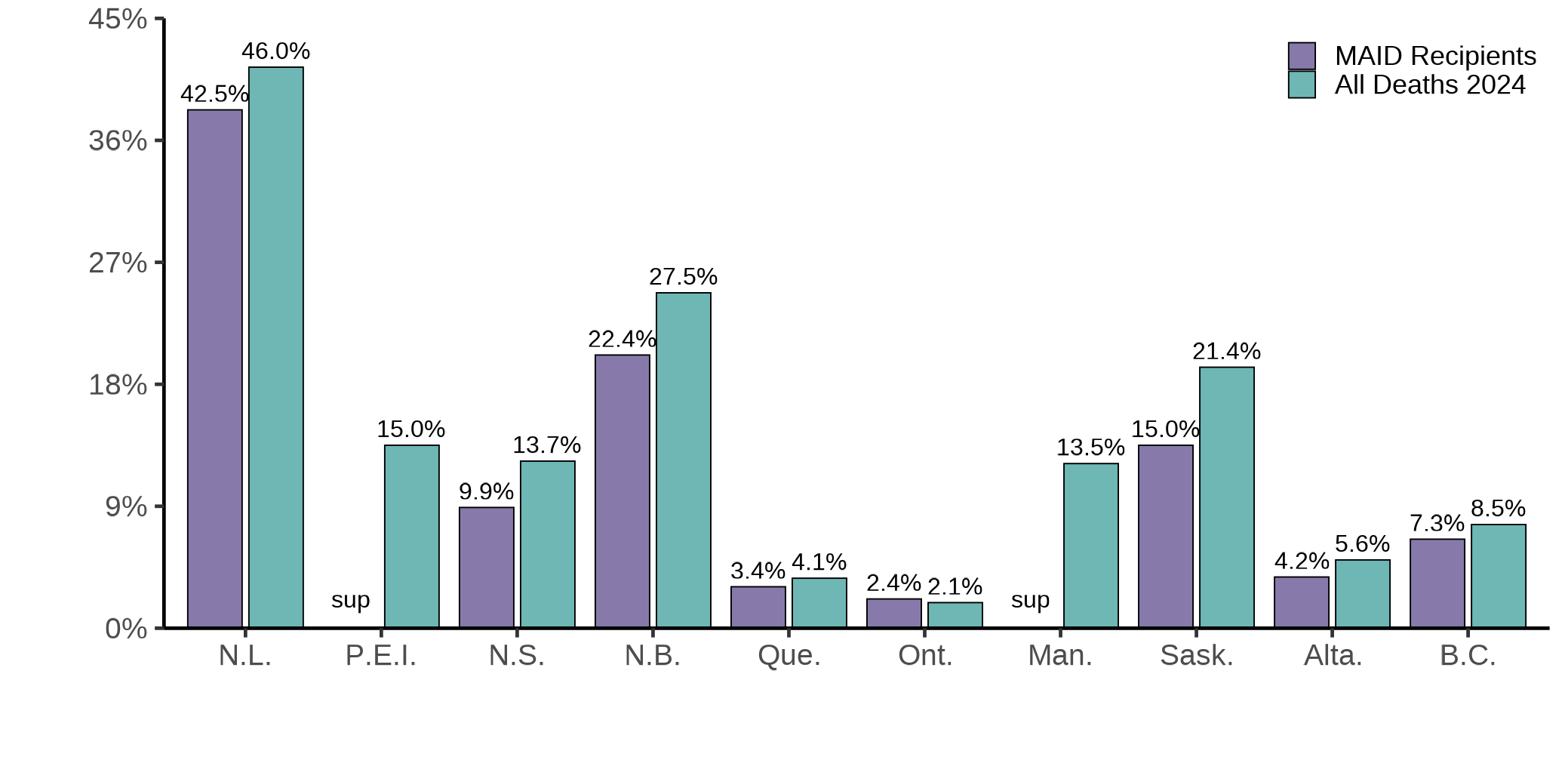

Consistent with previous years, most MAID provisions occurred in Quebec (36.4%), Ontario (30.0%) and British Columbia (18.2%), with these three provinces accounting for nearly 85% of all MAID provisions. The number of MAID provisions increased in most jurisdictions, with the exception of New Brunswick, Manitoba and Saskatchewan, where the number decreased relative to 2023. See Table C.1 (Appendix C) for a detailed breakdown of MAID provisions by province and territory.

MAID was administered by a practitioner in all cases that occurred in 2024. While self-administration of MAID is permitted in all provinces and territories in Canada (except for Quebec), very few people have chosen this option since 2016.

In 2024, the median age of MAID recipients was 77.9 years. The median age of Track 1 and Track 2 recipients was 78.0 years and 75.9 years, respectively. The median age of MAID recipients has increased slightly since 2023, when it was 77.6 years (77.7 years for Track 1 and 75.0 years for Track 2). The median and mean age of MAID recipients across provinces and territories is provided in Table C.2 (Appendix C).

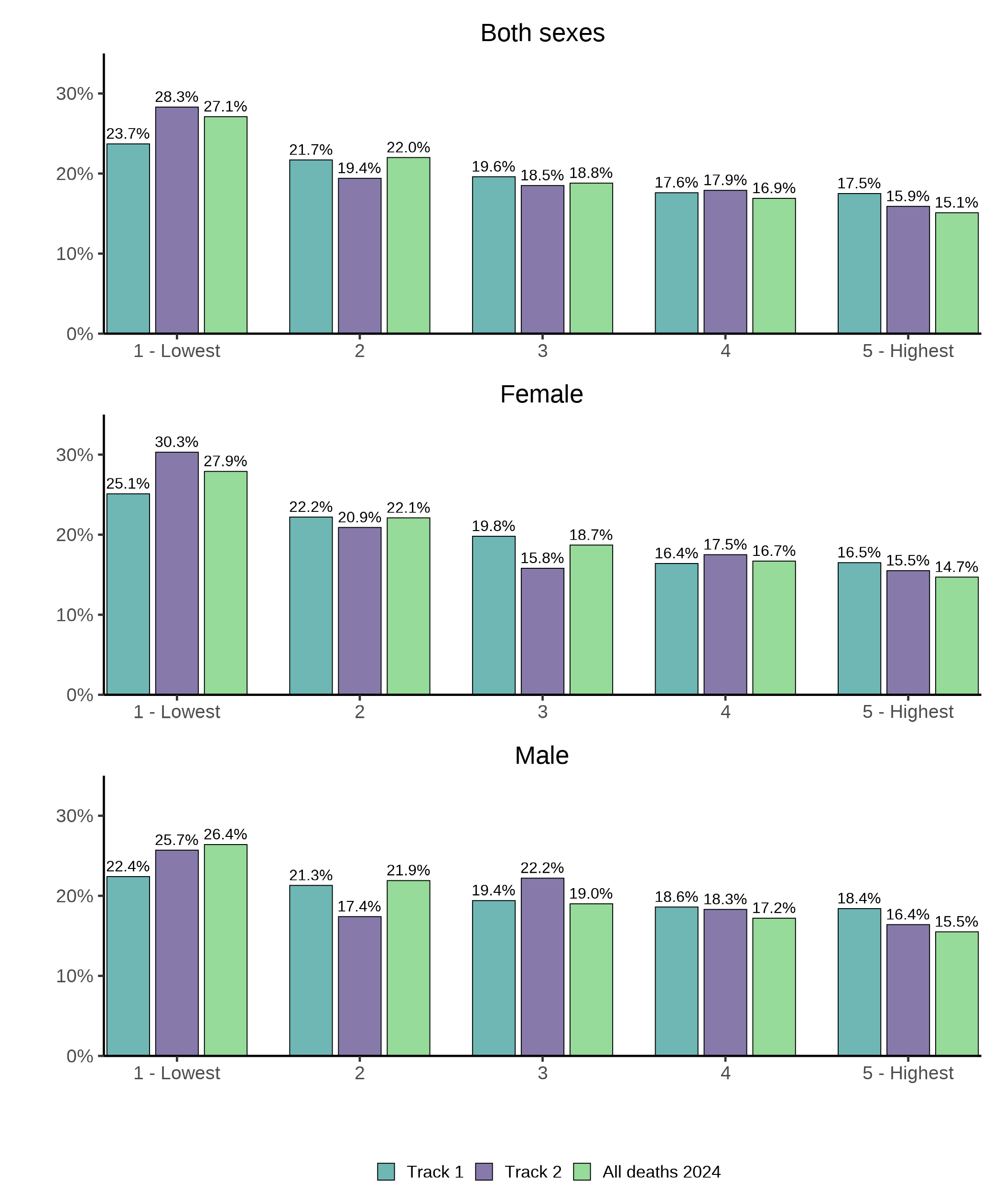

Figure 2.2b shows the proportion of individuals receiving MAID across each age group under Tracks 1 and 2. In both tracks, people who received MAID most frequently fell into the 75 to 84 age group. This finding is consistent with 2023 findings. As was the case for 2023, a greater percentage of Track 1 recipients were aged 75 years or older (60.9%) compared to those in Track 2 (53.5%). However, this gap has narrowed slightly compared to 2023, when 59.7% of Track 1 and 50.2% of Track 2 MAID recipients were aged 75 years or older. Similarly, in 2024, a greater proportion of Track 2 MAID recipients were under 64 years of age (21.6%) compared to Track 1 (13.5%). This gap has also narrowed slightly compared to 2023, when 23.5% of Track 2 and 13.8% of Track 1 MAID recipients were under 64 years of age.

Figure 2.2b - Text description

| Age group | Track 1 (%) | Track 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 18-44 | 1.1 | 3.7 |

| 45-54 | 2.5 | 5.2 |

| 55-64 | 9.9 | 12.7 |

| 65-74 | 25.6 | 24.9 |

| 75-84 | 33.7 | 30.7 |

| 85+ | 27.2 | 22.8 |

Figure 2.2c provides a breakdown of MAID provisions by sex and track. Similar to previous years, slightly more men (51.8%) than women (48.2%) received MAID in 2024. This aligns closely with provisional data from Statistics Canada on total deaths in Canada, which shows that, in 2024, 50.5% of people who died were men and 49.5% were women. Breaking down the data on MAID provisions by track demonstrates that while more men received MAID under Track 1 (men 52.2% vs. women 47.8%), more women received MAID under Track 2 (women 56.7% vs. men 43.3%). These percentages are close to those reported in 2023; however, the gap between men and women has widened slightly for Track 1 (from a difference of 3.2% in 2023 to a difference of 4.2% in 2024) and narrowed slightly for Track 2 (from a difference of 17.0% in 2023 to a difference of 13.4% in 2024).

Figure 2.2c - Text description

| Sex | Track 1 (%) | Track 2 (%) | All deaths, 2024 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 52.2 | 43.3 | 50.5 |

| Female | 47.8 | 56.7 | 49.5 |

Explanatory note:

- "All deaths" does not include accidental deaths, deaths by suicide or assault, or any death where the cause is unknown. For full details on this variable, see Appendix B.

As indicated in last year's annual report, the higher proportion of Track 2 MAID provisions among women is not unexpected. The findings are consistent with overall population health trends, where women are more likely to experience long-term health conditions Footnote 6 Footnote 7 and men experience higher rates of diseases with a higher mortality burden, Footnote 8 that would be more likely to make their deaths "reasonably foreseeable".

A breakdown of MAID provisions by track and by province/territory is provided in Table C.3 in Appendix C.

2.3 Requests not resulting in MAID

Request was determined to be ineligible

A MAID request is reported as "ineligible" if a practitioner has determined that the person who made the request did not meet one or more of the eligibility criteria outlined in the legislation. A practitioner can assess a person as ineligible without necessarily having assessed all of the criteria (i.e., once a person is found ineligible on the basis of one criteria, the practitioner can stop assessing). In 2024, 1,327 individuals who requested MAID were assessed as being ineligible for the procedure. This is an increase compared to 2023, when 1,031 MAID requests were assessed as being ineligible. Footnote 9 It is important to note that this finding is likely to be an underrepresentation of interest in MAID, given that many practitioners may not report on requests where a formal assessment has not been initiated, or if the person is deemed ineligible upon initial presentation (for instance, if the person does not have capacity to provide informed consent or is not 18 years of age or older).

Among the 1,327 individuals determined to be ineligible for MAID, 44.2% (n=587) were assessed under Track 1 and 24.2% (n=321) were assessed under Track 2. The remaining 31.6% (n=419) had not been assessed as either Track 1 or Track 2. It is worth noting that, although Track 2 provisions represent 4.4% of reports resulting in MAID, they represent 24.2% of all reports where there was a finding of ineligibility.

Table 2.3a outlines the reasons why people were found ineligible for MAID by track, based on the legislative criteria. As shown in the table, for people assessed under Track 1, the most common reason for a finding of ineligibility was that the person was deemed as not being capable of making decisions with respect to their health. For people assessed under Track 2, the most common reason for a finding of ineligibility was that the person was deemed as not being in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability.

| Practitioner indicated "no" to the following eligibility requirements | All cases | Track 1 | Track 2 | Did not assess track | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percent (%) | Count | Percent (%) | Count | Percent (%) | Count | Percent (%) | |

| Was the person capable of making decisions with respect to their health? | 425 | 32.0 | 281 | 47.9 | 48 | 15.0 | 96 | 22.9 |

| Did the person's illness, disease or disability, or their state of decline cause them enduring physical or psychological suffering that was intolerable to them and could not be relieved under conditions that they considered acceptable? | 402 | 30.3 | 155 | 26.4 | 137 | 42.7 | 110 | 26.3 |

| Was the person in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability? | 399 | 30.1 | 85 | 14.5 | 186 | 57.9 | 128 | 30.5 |

| Did the person give informed consent to receive MAID after having been informed of the means that are available to relieve their suffering, including palliative care? | 306 | 23.1 | 198 | 33.7 | 58 | 18.1 | 50 | 11.9 |

| Did the person have a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability? | 291 | 21.9 | 21 | 3.6 | 153 | 47.7 | 117 | 27.9 |

| Did the person make a voluntary request for MAID that, in particular, was not made as a result of external pressure? | 45 | 3.4 | 21 | 3.6 | 9 | 2.8 | 15 | 3.6 |

| Was the person eligible for health service funded by a government in Canada? | 17 | 1.3 | 6 | 1.0 | 6 | 1.9 | 5 | 1.2 |

| Was the person at least 18 years of age? | 5 | 0.4 | X Footnote a | X | X | X | 0 | 0.0 |

| Total | 1309 | - Footnote b | 584 | - | 321 | - | 404 | - |

|

||||||||

Request was withdrawn

A person can withdraw their request for MAID at any point during the eligibility assessment process or after completion of the assessment. In 2024, 692 individuals withdrew their request for MAID. This is an increase compared to 2023, when 574 individuals withdrew their MAID request. Footnote 10 Of those who withdrew their MAID request in 2024, 58.1% (n=402) were assessed under Track 1 and 16.8% (n=116) were assessed under Track 2. The remaining 25.1% (n=174) of individuals were not yet assessed as either Track 1 or Track 2. Under the regulations, practitioners must declare if an individual withdrew their request immediately before receiving MAID. There were 68 people who withdrew their request at this time. If considered as a percentage of all withdrawals within the track, 11.9% of Track 1 and 8.1% of Track 2 withdrawals happened immediately before a scheduled MAID provision.

Under the regulations, practitioners must provide the reason(s) why a person is withdrawing their request for MAID. These reasons are outlined in Table 2.3b. The most common reasons for withdrawing a MAID request were that the person accepted other means to relieve their suffering, Footnote 11 "other", and that the person changed their mind upon learning additional information about MAID. This was the case for people receiving MAID under both Track 1 and Track 2. Among those accepting other available means to relieve their suffering, the means that were most often pursued were pharmacological (n=235), health care services (n=162) and non-pharmacological services, such as neurostimulation, physiotherapy or nutritional counselling services (n=76).

| Reason a person withdrew their request for MAID | Responses | |

|---|---|---|

| Count | Percent (%) | |

| The person accepted means to relieve their suffering | 315 | 45.7 |

| OtherFootnote a | 227 | 32.9 |

| Upon learning additional information about MAID, the person decided it was not a path they wish to pursue | 196 | 28.4 |

| Individuals who the person considers important in their lives (religious leaders, family, caregivers, or professionals) do not support MAID | 55 | 8.0 |

| Unknown | 44 | 6.4 |

| Meeting the needs of a transfer and/or consultation were too cumbersome for the person | 14 | 2.0 |

| Total | 689 | - Footnote b |

|

||

Died of another cause

In 2024, 4,017 individuals who requested MAID died prior to receiving it. This is an increase from 2023 when 3,573 Footnote 12 people who requested MAID died of another cause. The vast majority of people who died before receiving MAID in 2024 were assessed under Track 1 (90.7%, n=3,643) while 1.6% (n=64) were assessed under Track 2. The remaining 7.7% (n=310) were not yet assessed as either Track 1 or Track 2.

When practitioners report that a person died before receiving MAID, they must provide, if known, at least one explanation for this outcome. Table 2.3c outlines the reasons provided by the practitioner, along with the frequency and median number of days between a MAID request and the individual's death. In 44 cases, the reason was not known. The data show that in the vast majority of cases, the person either never chose a date to proceed with MAID (n=1,661) or was found eligible, but died before their scheduled MAID provision (n=1,502). This was the case for people assessed under both Track 1 and Track 2. These findings could suggest a challenge related to the responsiveness of health systems with respect to MAID requests. However, studies have spoken to how, among patients with serious illness, being approved for MAID can help relieve distress over loss of autonomy and provide a sense of personal control over the circumstances of dying, even when they are uncertain about whether and when they will actually pursue it. Footnote 13 This is another possible explanation.

Individuals who died before they had selected a date to receive MAID had the longest median time between when they made their formal request and their death (45.0 days), whereas people who were referred for a MAID assessment or who had requested MAID in the later stages of their illness had the shortest median time between the formal request and death (4.0 days).

| Reason for natural death before MAID could be provided | Days between request and death, median | Response | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percent (%) | ||

| Person never chose a date to proceed with MAID provision | 45.0 | 1,661 | 41.8 |

| Person was found eligible but died before scheduled MAID provision | 19.0 | 1,502 | 37.8 |

| Person died before both assessments were completed | 7.0 | 752 | 18.9 |

| Person was referred or requested MAID too late (i.e., referral time was too short) | 4.0 | 353 | 8.9 |

| Other | 27.0 | 253 | 6.4 |

| Loss of capacity to consent without a waiver of final consent being completed | 14.5 | 107 | 2.7 |

| Operational issues (i.e., could not be moved to a facility that allowed MAID, medication shortages, bed shortages, health care personnel unavailable) | 19.0 | 34 | 0.9 |

| No assessor/provider available/willing | 23.0 | 12 | 0.3 |

| Lack of pharmacy willing to provide MAID medications | 10.5 | 6 | 0.2 |

| Total | NA | 3,973 | - Footnote a |

|

|||

3. MAID assessments: grievous and irremediable medical conditions

3.1 Most common medical conditions

In order to be eligible for MAID (both Tracks 1 and 2), a person must have a "grievous and irremediable medical condition". This criterion is met only when assessors are of the opinion that:

- the person has a serious and incurable illness, disease, or disability;

- the person is in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability; and

- the illness, disease, or disability or state of decline causes the person enduring physical or psychological suffering that is intolerable to the person and cannot be relieved under conditions that the person considers acceptable.

The nature and severity of the medical condition(s) a person experiences will have a significant bearing on a practitioner's judgement regarding whether or not each of the three elements of the "grievous and irremediable medical condition" eligibility criterion apply.

For each MAID request, a practitioner must report on the specific serious and incurable illness, disease, or disability or state of decline that is the cause of the individual's suffering. However, individuals requesting MAID very often suffer from more than one serious and incurable medical condition that contributes to the person's suffering. This can create a challenge for reporting as practitioners must consider all of the requester's circumstances, and singling out only one medical condition may not reflect the seriousness of the person's condition and the suffering they are experiencing.

For this reason, when filing their reports practitioners may – and often do – select more than one medical condition, and do not rank them in order of most significant impact on the individual's health. The broad categories provided to practitioners for MAID reporting purposes are cancer, neurological conditions, respiratory diseases, cardiovascular conditions, organ failure and "other" conditions (practitioners can select more than one). The conditions provided for the "other" conditions category include: diabetes, frailty, autoimmune conditions, chronic pain and mental disorders, but practitioners sometimes listed other conditions such as joint, bone and muscle issues, hearing and visual issues and various internal diseases in the write-in fields. Note that within the broad categories, practitioners can select multiple specific conditions.

For those who received MAID under Track 1, cancer was the most frequently cited medical condition (n=10,035), followed by "other" conditions (n=3,928), then cardiovascular conditions, such as congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation or vasculopathy (n=2,703). For Track 2, the most frequently indicated medical conditions were neurological conditions (n=378), "other" conditions (n=375) and cardiovascular conditions (n=94). As noted previously, practitioners can report more than one medical condition (e.g., both cancer and a neurological condition). Within each medical condition, they can also report more than one type per individual (e.g., both lung cancer and breast cancer). A full breakdown of medical conditions reported by MAID recipients in each province and territory is presented in Table C.4 (Appendix C).

The full list of reported conditions, and the percentage reported among men and women, is provided in Figure 3.1a. Under Track 1, the percentage of men and women represented under each medical condition closely mirror one another. Slightly more men than women were reported as having cancers, neurological conditions and cardiovascular conditions, while slightly more women than men were reported with respiratory and "other" conditions. Under Track 2, the gaps between women and men reporting each medical condition tended to be more pronounced. This was particularly true for neurological conditions (59.6% of men vs. 45.5% of women) and "other" conditions (57.8% of women vs. 45.7% of men).

Figure 3.1a - Text description

| Medical condition | Track 1 | Track 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male (%) | Female (%) | Male (%) | Female (%) | |

| Cancer | 66.2 | 60.9 | 5.0 | 3.4 |

| Neurological | 12.2 | 11.9 | 59.6 | 45.5 |

| Respiratory | 13.5 | 13.8 | 7.9 | 11.3 |

| Cardiovascular | 17.6 | 16.6 | 14.8 | 11.3 |

| Other | 26.6 | 31.0 | 45.7 | 57.8 |

Explanatory note:

- Organ failure has been added to the "other" conditions category. See Appendix B for more information.

Cancer was the most frequently cited medical condition among people in nearly all age groups who received MAID in 2024. The exception is those aged 85 years or older, for whom "other" conditions were the most frequently cited. Among MAID recipients with cancer, the most frequently specified types were lung, colorectal, pancreatic and hematologic cancer.

Figure 3.1b compares the age distribution of MAID recipients reporting each underlying medical condition to that of all deaths in Canada attributed to the most common medical conditions for MAID, with the "other" category encompassing all other natural causes of death. The data demonstrate that the age distribution of MAID recipients tends to closely follow that of all decedents. For most medical conditions, the percentage of "all deaths" as reported through vital statistics data tend to be slightly greater than the MAID percentages in the younger age groups (i.e., 18 to 44, 45 to 54, 55 to 64) and in the very oldest age group (i.e., 85 years and older), whereas the MAID percentages tend to be slightly greater than the all deaths percentages in the 65 to 74 and 75 to 84 age groups. There are exceptions to this. For example, in the cardiovascular conditions table, the MAID percentage exceeds the "all deaths" percentage in the 85 years or older age group by 6.8%. There are also instances where the gap between the percentage of MAID provisions and the percentage of all deaths is more pronounced.

Among MAID recipients with neurological conditions, the most frequently specified conditions were Parkinson's disease (n= 472), Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS or, Lou Gehrig's disease) (n=450), Dementia (n=368) and Multiple Sclerosis (n=159). The category of neurological illness is where there are the greatest variations with respect to MAID provisions as compared to data on "all deaths".

Among those aged 65 to 74, the percentage of MAID recipients diagnosed with neurological conditions exceeded the "all deaths" percentage in the same category by 9.6%. Among those aged 85 years and older, however, the percentage of persons in the "all deaths" category with a neurological condition exceeded the comparable percentage of MAID provisions by 15.6%. This is likely a result of the type of medical conditions captured under this category, and the wide variations in age of onset and associated progression of illness.

For example, provisional vital statistics data for 2024 show that Alzheimer's and dementia Footnote 14 combined accounted for nearly 20% of deaths of people in Canada aged 85 years and older and that nearly 70% of all deaths due to Alzheimer's disease and dementia were among people in this age group. Footnote 15 Meanwhile, comparatively few MAID recipients had a diagnosis of dementia Footnote 16 (16.2% of those with a neurological illness or 2.2% (n=368) of all MAID provisions), with a median age of 81.

Similarly, 19.8% (n=450) of persons with a neurological condition who received MAID were reported as having a diagnosis of ALS, with a median of 70 years of age. While exact numbers of overall deaths attributed to ALS are not available through vital statistics data, Footnote 17 there was an estimated total of 1,200 deaths included under the broad category of motor neuron disease in 2024, in which ALS is included. Footnote 18

ALS is a disease that progressively paralyzes people. Over time, people with ALS will lose the ability to walk, talk, swallow and eventually breathe. There are limited treatment options available to address symptoms, and there is no cure. Most people with ALS die within two to five years of diagnosis. Footnote 19 While persons with a diagnosis of ALS represented 2.7% of all MAID provisions, it is estimated that people with motor neuron disease accounted for only 0.4% of all deaths in 2024.Footnote 20

While additional research is required to better understand the significance of these findings, they do suggest that persons experiencing an illness for which there are limited options for treatment and relief of suffering may be more likely to seek MAID.

Figure 3.1b - Text description

| Medical condition | Age 18-44 | Age 45-54 | Age 55-64 | Age 65-74 | Age 75-84 | Age 85+ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAID (%) | All Deaths 2024 (%) | MAID (%) | All Deaths 2024 (%) | MAID (%) | All Deaths 2024 (%) | MAID (%) | All Deaths 2024 (%) | MAID (%) | All Deaths 2024 (%) | MAID (%) | All Deaths 2024 (%) | |

| Cancer | 1.4 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 11.8 | 13.0 | 29.7 | 27.3 | 34.8 | 31.7 | 19.2 | 21.9 |

| Neurological | 1.2 | 2.0 | 3.0 | 2.2 | 11.3 | 6.9 | 26.7 | 17.1 | 34.6 | 33.0 | 23.2 | 38.8 |

| Respiratory | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 5.7 | 6.9 | 24.0 | 19.3 | 39.9 | 32.1 | 29.6 | 39.2 |

| Cardiovascular | 0.3 | 1.1 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 3.6 | 7.8 | 13.8 | 17.1 | 30.6 | 27.4 | 51.1 | 44.3 |

| Other | 1.1 | 2.2 | 1.9 | 2.5 | 6.5 | 6.4 | 17.9 | 13.5 | 30.0 | 26.1 | 42.7 | 49.3 |

Explanatory notes:

- These data are presented for illustrative purposes only and should be interpreted with caution as MAID data and vital statistics data are not directly comparable.

- While multiple medical conditions can be reported for each MAID provision, only one cause of death is reported in vital statistics (as indicated on the certificate of death).

- "All deaths" does not include accidental deaths, deaths by suicide or assault, or any death where the cause is unknown. For full details on this variable, see Appendix B.

- Organ failure has been added to the "other" conditions category. See Appendix B for more information.

3.2 Length of time living with a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability

Under the regulations, practitioners are required to indicate how long the person requesting MAID has had a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability.

Figure 3.2a outlines the length of time MAID recipients reported living with a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability, broken down by track. Consistent with findings from 2023, people receiving MAID under Track 2 tended to live with a serious and incurable condition for a longer period of time than those receiving MAID under Track 1: 18.5% of people receiving MAID under Track 2 lived with a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability for more than 20 years, compared to 2.5% of those under Track 1. In contrast, 7.8% of people receiving MAID under Track 2 lived with a serious and incurable illness, disease or disability for less than one year, compared to 47.1% of those under Track 1.

Figure 3.2a - Text description

| Length of time | Track 1 (%) | Track 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 year | 47.1 | 7.8 |

| 1 year to less than 5 years | 35.2 | 35.5 |

| 5 years to less than 10 years | 10.4 | 22.6 |

| 10 years to less than 20 years | 4.9 | 15.6 |

| 20 years or more | 2.5 | 18.5 |

In addition, many MAID recipients lived with more than one serious and incurable medical condition for a significant amount of time. Just over one-third (36.3%) of Track 1 MAID recipients had one medical condition for one year or more, compared to 67.9% of Track 2 MAID recipients. Meanwhile, just 16.7% of Track 1 MAID recipients had two or more medical condition for one year or more, compared to 24.3% of Track 2 MAID recipients. These findings demonstrate that Track 2 MAID recipients tended to have a greater number of medical conditions for a longer period of time.

3.3 Advanced state of irreversible decline in capability

The second element of the "grievous and irremediable medical condition" eligibility criterion is that the person must be in "an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability". This is understood to mean that the reduction in the person's ability to undertake activities that are meaningful to them is severe and cannot be improved through reasonable interventions. Footnote 21 This loss of capability may be sudden, gradual, ongoing, or stable. Footnote 22

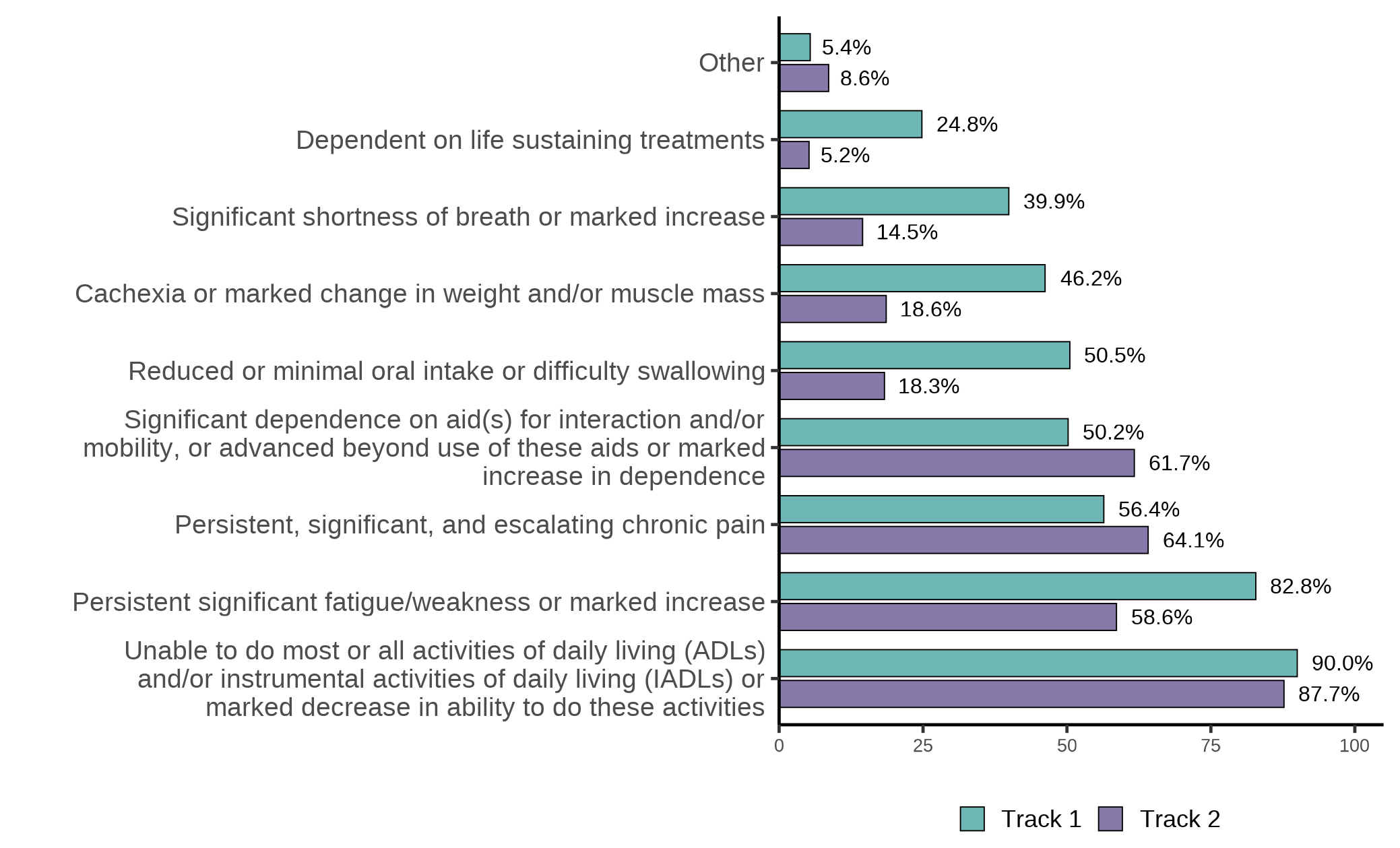

Figure 3.3a outlines, by track, the different indicators cited by practitioners for determining that a person was in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability. For both Tracks 1 and 2, the most frequently cited indicator was an inability of the person to do most or all activities of daily living (e.g., feeding, bathing and toileting oneself), or instrumental activities of daily living (e.g., managing finances, meal preparation, managing medications). This was cited in 90.0% of Track 1 cases and in 87.7% of Track 2 cases. Other commonly cited indicators for both Track 1 and Track 2 were:

- Persistent significant fatigue/weakness (or a marked increase thereof)

- Persistent, significant and escalating chronic pain; and

- Significant dependence on aid(s) for interaction.

Several indicators associated with decline at end of life were cited much more frequently in Track 1 MAID cases than they were in Track 2 MAID cases. These include:

- Reduced or minimal oral intake or difficulty swallowing;

- Cachexia or marked change in weight and/or muscle mass;

- Significant shortness of breath (or a marked increase thereof); and

- Dependence on life-sustaining treatments.

Figure 3.3a - Text description

| Indicator | Track 1 (%) | Track 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Unable to do most or all activities of daily living (ADLs) and/or instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs) or marked decrease in ability to do these activities | 90.0 | 87.7 |

| Persistent significant fatigue/weakness or marked increase | 82.8 | 58.6 |

| Persistent, significant, and escalating chronic pain | 56.4 | 64.1 |

| Significant dependence on aid(s) for interaction and/or mobility, or advanced beyond use of these aids or marked increase in dependence | 50.2 | 61.7 |

| Reduced or minimal oral intake or difficulty swallowing | 50.5 | 18.3 |

| Cachexia or marked change in weight and/or muscle mass | 46.2 | 18.6 |

| Significant shortness of breath or marked increase | 39.9 | 14.5 |

| Dependent on life sustaining treatments | 24.8 | 5.2 |

| Other | 5.4 | 8.6 |

Explanatory note:

- More than one option could be selected. Totals will exceed 100%.

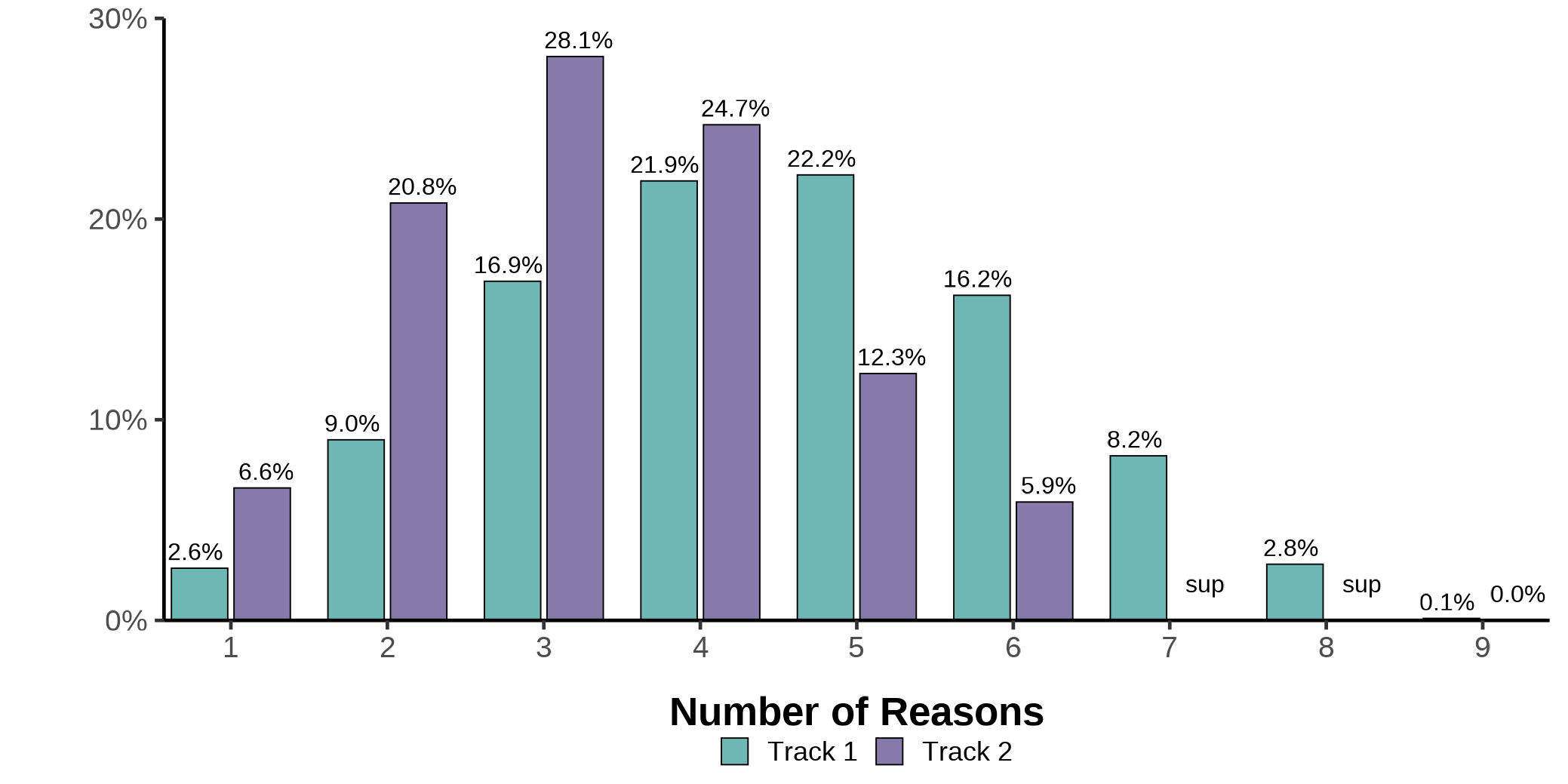

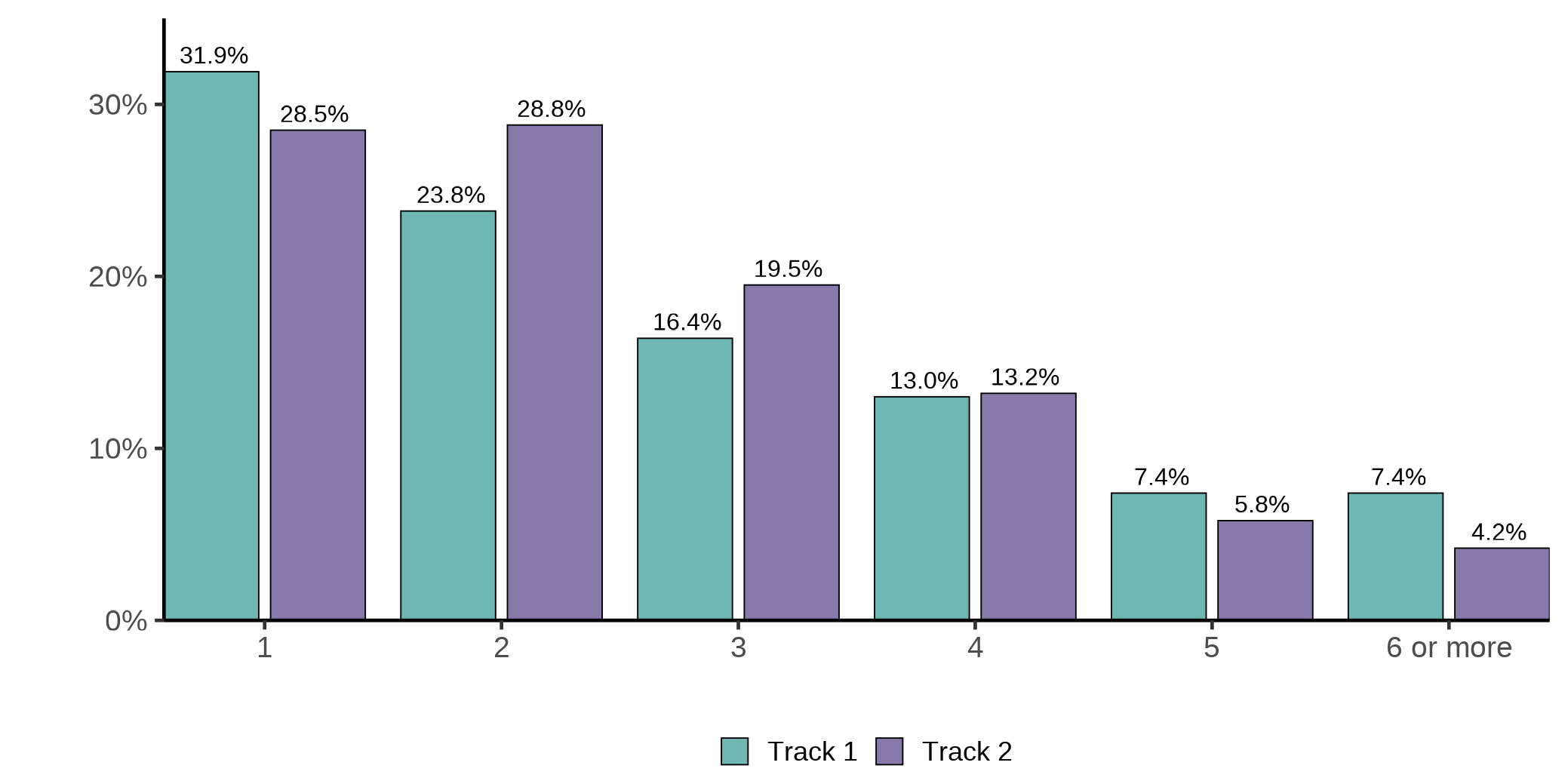

Practitioners often cite more than one indicator of a person being in an advanced state of irreversible decline in capability. Figure 3.3b presents the distribution of the number of indicators reported, by track. As shown in the figure, practitioners most often cited five indicators of advanced state of irreversible decline among Track 1 MAID recipients (i.e., in 22.2% of Track 1 cases), whereas they most often cited three indicators among Track 2 MAID recipients (i.e., in 28.1% of Track 2 cases).

Figure 3.3b - Text description

| Number of indicators | Track 1 (%) | Track 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.6 | 6.6 |

| 2 | 9.0 | 20.8 |

| 3 | 16.9 | 28.1 |

| 4 | 21.9 | 24.7 |

| 5 | 22.2 | 12.3 |

| 6 | 16.2 | 5.9 |

| 7 | 8.2 | X |

| 8 | 2.8 | X |

| 9 | 0.1 | 0.0 |

3.4 Nature of suffering

The third element of the "grievous and irremediable medical condition" eligibility criterion is that the person is experiencing "enduring physical or psychological suffering that is intolerable to them and that cannot be relieved under conditions that they consider acceptable."

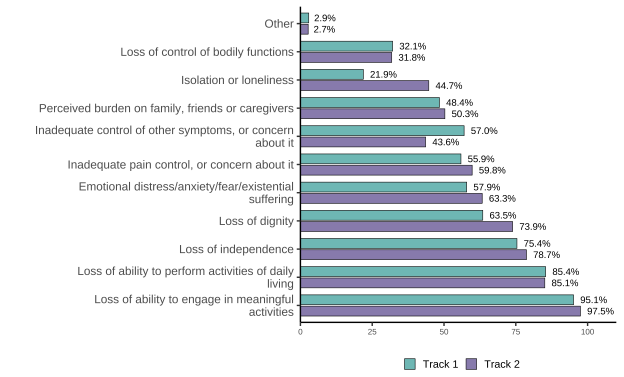

Figure 3.4a outlines the sources of suffering related to the person's medical condition that were reported by practitioners. Given that people approved to receive MAID typically report multiple sources of suffering associated with their illness, the percentages total over 100%. As shown in the figure, loss of ability to engage in meaningful activities was the most commonly reported source of suffering among MAID recipients in both Tracks 1 and 2, followed by loss of ability to perform activities of daily living (i.e., basic self-care tasks, such as eating, drinking, dressing, moving around and maintaining personal hygiene). The proportion of Track 1 and Track 2 MAID recipients reporting each source of suffering was at or near equal with some exceptions: Track 1 MAID recipients were more likely to report inadequate control of other symptoms, or concern about it, while Track 2 MAID recipients were more likely to report isolation or loneliness and loss of dignity.

Figure 3.4a - Text description

| Nature of suffering | Track 1 (%) | Track 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Loss of ability to engage in meaningful activities | 95.1 | 97.5 |

| Loss of ability to perform activities of daily living | 85.4 | 85.1 |

| Loss of independence | 75.4 | 78.7 |

| Loss of dignity | 63.5 | 73.9 |

| Emotional distress/anxiety/fear/existential suffering | 57.9 | 63.3 |

| Inadequate pain control, or concern about it | 55.9 | 59.8 |

| Inadequate control of other symptoms, or concern about it | 57.0 | 43.6 |

| Perceived burden on family, friends or caregivers | 48.4 | 50.3 |

| Isolation or loneliness | 21.9 | 44.7 |

| Loss of control of bodily functions | 32.1 | 31.8 |

| Other | 2.9 | 2.7 |

Explanatory note:

- More than one option could be selected. Totals will exceed 100%.

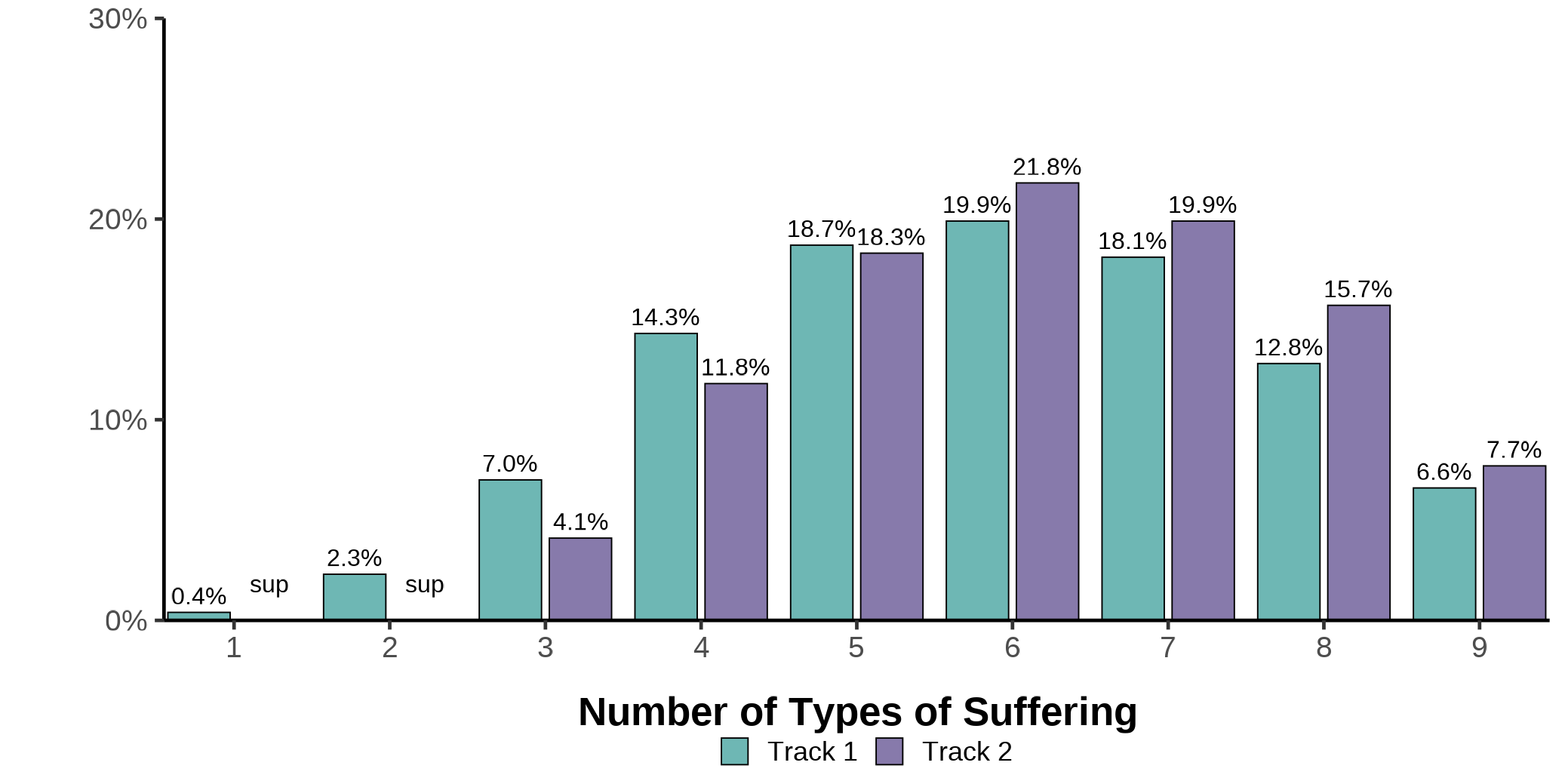

Suffering in the context of a serious and incurable illness is complex and multidimensional. Academic literature speaks to multiple aspects of suffering, such as physical, psychological, social, systemic, existential and spiritual. Footnote 23 Footnote 24 Footnote 25 With this in mind, it is not surprising that, for almost every MAID case, practitioners reported more than one source of suffering related to the person's medical condition. Figure 3.4b presents the number of types of suffering reported, by track. As shown in the figure, practitioners most commonly cited six sources of suffering. This was the case for both Track 1 (19.9%) and Track 2 (21.8%) MAID cases. Overall, the data demonstrate that practitioners tend to report more sources of suffering for Track 2 MAID recipients than they do for Track 1 MAID recipients.

Figure 3.4b - Text description

| Number of types of suffering | Track 1 (%) | Track 2 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.4 | X |

| 2 | 2.3 | X |

| 3 | 7.0 | 4.1 |

| 4 | 14.3 | 11.8 |

| 5 | 18.7 | 18.3 |

| 6 | 19.9 | 21.8 |

| 7 | 18.1 | 19.9 |

| 8 | 12.8 | 15.7 |

| 9 | 6.6 | 7.7 |

Isolation and loneliness

In its 2024 "Ageing in Canada Survey" the National Institute on Ageing found that 2 in 10 (19%) of people in Canada aged 50 years and older were very lonely, 40% were somewhat lonely and 43% were at risk of social isolation. Footnote 26 Isolation and loneliness are known to have serious impacts on physical and mental health, quality of life and longevity.Footnote 27

Some media reports have expressed concerns about the extent to which isolation or loneliness may drive a person's MAID request. Footnote 28 It is important, however, to contextualize the findings on isolation and loneliness within the relevant academic literature and overall MAID data to gain a fuller understanding about the reasons people seek MAID.

As previously noted in section 3.2, people receiving MAID under Track 2 have often lived with their medical condition for many years. Meanwhile, it has been found that people with long-term health conditions are more likely to experience episodic and chronic loneliness and social isolation than those without. Footnote 29 It is relevant to note here that people receiving MAID under Track 2 are more likely to live alone than those receiving MAID under Track 1, as indicated later in this report in section 5.3.

A recent article on MAID recipients in British Columbia (using 2023 data) found that people requesting MAID in that province who reported isolation or loneliness as a source of suffering cited more sources of suffering on average than those who did not. Footnote 30 Recognizing that the article was not peer-reviewed, Health Canada replicated this analysis at a national level by looking at all MAID recipients in Canada who cited isolation or loneliness as a source of suffering in 2024. Health Canada similarly found that the average number of sources of suffering cited was higher among those who cited isolation and loneliness (Track 1: 7.5; Track 2: 7.1) than it was among those who did not (Track 1: 5.5; Track 2: 5.8).

Isolation or loneliness was not reported as a sole source of suffering for any MAID cases in 2024. It was cited alongside only one other type of suffering in fewer than five MAID cases, all of which were Track 1.

Perceived burden on family, friends and caregivers, or "self-perceived burden"

The perception of being a burden to others is a common feeling among people with serious illness. This is often referred to as "self-perceived burden" in palliative care literature, and is defined as "a multidimensional construct arising from the care recipient's feelings of dependence and the resulting frustration and worry, which then may lead to negative feelings of guilt at being responsible for the caregiver's hardship." Footnote 31 Researchers have highlighted the clinical importance of self-perceived burden, given the distress and suffering it causes, as well as its negative impact on quality of life and sense of dignity. Footnote 32 Some have also questioned the potential role that self-perceived burden may play in motivating a person's MAID request and the ways in which it may expose broader deficits when it comes to providing adequate home care and supports for caregivers.Footnote 33

As was done for the recent article presenting an analysis of British Columbia MAID data, Footnote 34 Health Canada looked at all MAID recipients in Canada who cited "perceived burden on family, friends and caregivers" as a source of suffering. Health Canada similarly found that the average number of sources of suffering cited was higher among those who cited self-perceived burden (Track 1: 6.8; Track 2: 7.1) than those who did not (Track 1: 5.1; Track 2: 5.6). Self-perceived burden was cited as a sole source of suffering in fewer than five MAID cases and alongside only one other type of suffering in 18 cases. All of these cases were classified as Track 1.

3.5 Determination of the MAID request as voluntary

The federal legislation stipulates that an individual's request for MAID must be voluntary and not made as a result of external pressure. As part of their reporting obligations when providing MAID, practitioners are required to specify how they formed the opinion that the individual's MAID request was voluntary. Results for 2024 are consistent with findings from previous years.

In virtually all cases where MAID was provided, practitioners reported that they had consulted directly with the person to determine the voluntariness of the request for MAID. Most practitioners determined voluntariness through multiple sources, such as prior consultation with the person, consultation with family members or friends, review of the person's medical records, and consultation with other health or social service professionals involved in the person's care. Practitioners most often selected three different sources of information for determining voluntariness. In 21.2% of Track 1 cases, the practitioner selected only one source of information for determining voluntariness compared to 12.6% of Track 2 cases. In 34.9% of Track 2 cases, the practitioner selected between 4-5 sources of information compared to 25.0% of Track 1 cases.

4. Socio-demographic considerations, access and inequality

4.1 Importance and challenges of collecting data on identity

Under the regulations, practitioners are required to collect information respecting race, Indigenous identity and disability in the context of a MAID request, if the person consents to the collection of this information. The purpose of this data collection is to help determine the presence of individual or systemic inequity or disadvantage in the delivery of MAID.

There are different approaches across provincial and territorial health systems to collecting this data:

- In British Columbia, the Northwest Territories, and Alberta the information is collected through patient request forms.

- In Saskatchewan and Manitoba, it is collected through care coordination services.

- In the remaining provinces and territories, it is up to individual practitioners to ask the requester if they wish to self-identify.

There are many factors that could hinder a person's willingness to self-identify during any clinical encounter, including during a MAID assessment. These include, for example, concerns about how this information might be used as well as racism and discrimination that the individual may have previously experienced in their health care.

Health Canada's technical guidance document for practitioners on the MAID reporting requirements clarifies that the data elements on race, Indigenous identity and disability are "self-identification" questions, reflecting how the person identifies themselves. Footnote 35 The responses do not reflect an individual's legal status or registration (in the case of Indigenous identity). Health Canada's guidance encourages practitioners to reinforce that any self-identification information provided has no bearing on the person's care or MAID assessment.

Data collection on identity in 2024

As mentioned in section 1.2, 2024 was the second year of data collection under the updated regulations. While the self-identification data for 2024 was more complete than that for 2023, the varied approaches within provincial and territorial health systems to collecting this information continue to impact data quality and reliability. For instance, in provinces and territories where the information must be collected by the practitioner, practitioners have reported being reluctant to ask this series of questions. This reluctance may stem from concerns about how asking these questions may impact the clinical relationship and create distrust. It may also stem from a lack of understanding regarding the relevance of asking these questions in the context of a MAID request. This underscores the continued need for practitioner support and cultural safety training to ensure this information can be collected in a culturally safe and clinically appropriate way. Health Canada is working with provincial and territorial health officials to improve data collection, consistency and quality, and to help sensitize practitioners to these reporting obligations.

Given the above-noted limitations, the information in this section should be interpreted with caution.

4.2 MAID by racial, ethnic or cultural group

Data is collected on racial, ethnic or cultural group categories based on guidance from the Canadian Institute of Health Information Footnote 36 and consistent with the Statistics Canada "visible minority" identity question in the 2021 Census. Individuals who identify with multiple groups or mixed groups can select more than one of the listed categories, or may choose to provide specific details under the "specify other race category".Footnote 37

A total of 15,927 Footnote 38 of the 16,499 people who received MAID in 2024 responded to this question, the vast majority of whom (95.6%) identified as Caucasian (White). Footnote 39 For context on how this compares to the overall population of Canada, approximately 70% of people in Canada identified as Caucasian in the most recent Census. Footnote 40 The second most commonly reported racial, ethnic or cultural identity among MAID recipients was East Asian (1.6%).

Given both the data limitations outlined in section 4.1, and the relative homogeneity of the responses provided, it is not possible to undertake more meaningful analysis with respect to potential differences with respect to the provision of MAID according to racial or ethnic identity. The proportion of MAID recipients identifying as Caucasian (White) by province and territory is provided in Table C.5 (Appendix C).

4.3 Indigenous people who received MAID

Given the data limitations outlined in section 4.1, the data presented in this section should not be taken as accurately representing the population of Indigenous people in Canada who received MAID in 2024. Accordingly, analyses of these data are limited to prevent readers from drawing erroneous conclusions about the profile of First Nations, Inuit and Métis people receiving MAID in Canada.

Individuals requesting MAID are asked whether they belong to one or more of the three constitutionally recognized groups of Indigenous Peoples in Canada: First Nations, Inuit and Métis.

A total of 16,115 Footnote 41 of the 16,499 people who received MAID in 2024 responded to this question, with 164 people self-identifying as Indigenous. There were 102 people who self-identified as First Nations, 57 people who self-identified as Métis and 7 people who self-identified as Inuit.

The majority of self-identified Indigenous people who received MAID were assessed under Track 1 (93.9%, n=154), while 6.1% (n=10) were assessed under Track 2. Health Canada cannot report differences by distinction between Track 1 and Track 2 without compromising confidentiality. The proportion of people who received MAID under Track 2 and self-identified as Indigenous is slightly higher than that of the overall population of people in Canada who received MAID under Track 2. However, given the relatively small number of people who received MAID and self-identified as Indigenous, it is not possible to draw meaningful conclusions about this finding.

The most commonly reported underlying medical conditions among Indigenous people who received MAID mirror those of the overall population of people in Canada who received MAID (see section 3.1).

It is important to note that there was significant variation across the country in regard to data completeness on the question of Indigenous identity, which compromises the reliability of the data presented. Some provinces had inconsistently high levels of "unknown" responses. For example, while the proportion of responses that were "unknown" was less than 8% in most provinces and territories, in one province the proportion was 30.1%. Some provinces also had inconsistently high levels of individuals not consenting to respond: while for most provinces and territories, the proportion of "do not consent" responses was less than 10%, "do not consent" responses accounted for 25.0% of responses in one province and 23.1% of responses in another.

Since Health Canada began reporting on Indigenous identity in the context of MAID last year, departmental officials have been having conversations with Indigenous partners regarding the collection and appropriate use of this data. During conversations in the lead up to the publication of this year's annual report, some partners suggested comparing the proportion of MAID recipients who self-identified as Indigenous to the proportion of people who identified as Indigenous and died of natural causes. As noted during these conversations, this analysis would improve transparency by highlighting discrepancies across the country regarding the completeness of the data on Indigenous identity.

In response to this suggestion, and to better contextualize the data on Indigenous identity, Health Canada worked with Statistics Canada to do the comparison, presented in Table 4.3a. As shown in the table, the percentage of people who identified as Indigenous and died of natural causes exceeds the proportion of people who self-identified as Indigenous and received MAID in every region/province, often to a very large degree. This is particularly true in Manitoba, Saskatchewan and the Territories. In addition to issues around the quality and completeness of the data, this could be the result of a combination of factors such as:

- Challenges in accessing MAID, particularly in rural and remote communities where a greater proportion of Indigenous people live (compared to non-Indigenous people)Footnote 42

- Distrust of the health care system, based on experiences of anti-Indigenous racism, Footnote 43 that limits the ability to have comprehensive end of life care discussions;

- Potential discomfort and/or lack of understanding regarding the topic of MAID Footnote 44 and;

- Potential disconnection between MAID and Indigenous Worldviews.Footnote 45

| Region/provinceFootnote a | Proportion of MAID recipients who self-identified as Indigenous in 2024Footnote b % |

Estimated proportion of people who died of natural causes and identified as Indigenous, 2021 – 2023Footnote cFootnote d % |

|---|---|---|

| Atlantic | 1.0 | 3.9 |

| Que. | 0.3 | 2.5 |

| Ont. | 0.9 | 2.7 |

| Man. | 2.7 | 13.2 |

| Sask. | 3.8 | 12.4 |

| Alta. | 2.0 | 6.1 |

| B.C. | 1.8 | 5.1 |

| Territories | 21.7 | 62.8 |

|

||

Health Canada will continue to have conversations with Indigenous partners regarding the collection and appropriate use of the data on Indigenous identity and is working with provinces and territories to identify opportunities to improve data quality and consistency over the longer term.

Recognizing the limitations of the data on Indigenous identity, and the importance of Indigenous data sovereignty, this data will not be shared with outside researchers without further discussions with Indigenous partners.

4.4 Persons with disabilities who received MAID

According to the most recent available data, 8 million people in Canada have at least one disability that limits them in their daily activities, representing 27% of people aged 15 and older. The rate of disability is higher among women (30%) than it is among men (24%) and increases with age, with 40% of adults aged 65 and older reporting at least one disability. Footnote 47 Nearly half of persons with disabilities report having at least one unmet need for health services.Footnote 48

Recognizing the longstanding systemic inequities faced by persons with disabilities, Canada is taking several actions to reduce barriers to inclusion among this population. These include, for example, adopting the Accessible Canada Act, which aims to identify, remove and prevent barriers facing people with disabilities, as well as implementing Canada's Disability Inclusion Action Plan to improve the social and economic participation of persons with disabilities in Canada.Footnote 49

Collecting information on disability in the context of MAID provides important insight into the extent to which persons with disabilities are seeking and receiving MAID, as well as the medical circumstances motivating their requests. Footnote 50 Under the regulations, practitioners are instructed to ask people requesting MAID to indicate if, in their opinion, they have a disability. If the person requests a further explanation as to what is meant by the term "disability", practitioners are encouraged to describe this as "a functional limitation in any one of the following ten areas, which cannot be corrected with the use of aids: seeing, hearing, mobility, flexibility, dexterity, pain-related, learning, developmental, mental health related or memory."Footnote 51

In 2024, 16,104 Footnote 52 of the 16,499 people who received MAID responded to the series of questions on disability. This is a significant improvement over last year when 10,581 of the 15,343 people who received MAID responded to this series of questions. Similar to the question on Indigenous identity, there was some variation across the country in regards to data completeness and quality. For example, data were missing on this series of questions for nearly half of MAID recipients in one jurisdiction and the proportion of MAID recipients who did not consent to disclosing this information ranges from as low as two percent to over 10 percent. As such, overall findings should still be interpreted with caution.

Table 4.4a outlines the profile of people receiving MAID who self-reported having a disability. Of the 16,104 people who responded to this series of questions, 5,295 (32.9%) self-identified as having a disability: 31.6% (n=4,858) of Track 1 respondents self-identified as having a disability compared to 61.5% (n=437) of Track 2 respondents.

| Characteristic | Track 1 | Track 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percent (%) | Count | Percent (%) | |

| Total respondents to the self-identified disability questionFootnote a | 15,394 | 97.6 | 710 | 97.0 |

| Self-reported having a disability | 4,858 | 31.6 | 437 | 61.5 |

|

||||

The rates at which persons receiving MAID self-reported having a disability varied widely across provinces and territories, particularly under Track 1, where the rate ranged from as low as 12.0% in Quebec and as high as 100% in the Northwest Territories. Under Track 2, the lowest rate was reported in Quebec (49.6%) and the highest rate was reported in Saskatchewan (88.9%). The proportion of MAID recipients self-reporting having a disability by province and territory is presented in Table C.5 (Appendix C).

Table 4.4b outlines the distribution of people receiving MAID who self-reported having a disability by track, age, sex and requirement for disability support services.

When looking at age, we see that under Track 1, the share of people who self-report having a disability increases in the older age groups. Under Track 2, the largest proportion of people who self-reported having a disability was in the 75 to 84 age group; the share declines again among those aged 85 and older.

When looking at sex, we see that under Track 1, slightly more men (50.8%) than women (49.2%) self-reported having a disability. This represents a shift from 2023 when slightly more women (51.2%) than men (48.8%) who received MAID under Track 1 self-reported having a disability. Under Track 2, proportionally more women (55.6%) than men (44.4%) self-reported having a disability, which aligns closely with 2023 data, as well as with disability trends among the general population of Canada.Footnote 53

Health Canada also looked at the proportion of MAID recipients with a self-reported disability that practitioners reported as requiring disability support services. The findings show that most people who received MAID under Track 1 (64.1%) and Track 2 (67.7%) who self-reported having a disability were also reported by practitioners as having required disability support services. This gap has narrowed since 2023, when 68.4% of Track 1 MAID recipients self-reporting disability were reported by practitioners as having required disability support services, compared to 75.7% of Track 2 MAID recipients.

| Characteristic | Track 1 | Track 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count | Percent (%) | Count | Percent (%) | |

| Age | ||||

| 18-44 | 64 | 1.3 | 21 | 4.8 |

| 45-54 | 127 | 2.6 | 26 | 5.9 |

| 55-64 | 477 | 9.8 | 71 | 16.2 |

| 65-74 | 1,107 | 22.8 | 101 | 23.1 |

| 75-84 | 1,510 | 31.1 | 125 | 28.6 |

| 85 and older | 1,572 | 32.4 | 93 | 21.3 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 2,466 | 50.8 | 194 | 44.4 |

| Female | 2,390 | 49.2 | 243 | 55.6 |

| Required disability support services | ||||

| Yes | 3,114 | 64.1 | 296 | 67.7 |

| No | 1,083 | 22.3 | 103 | 23.6 |

| Do not know | 661 | 13.6 | 38 | 8.7 |

|

||||

In the event that a person requesting MAID indicates that they have a disability, practitioners are instructed to ask the person to indicate:

- The type of disability (or types of disabilities) they have

- How long they have had their disability

- How often their disability limits their daily activities

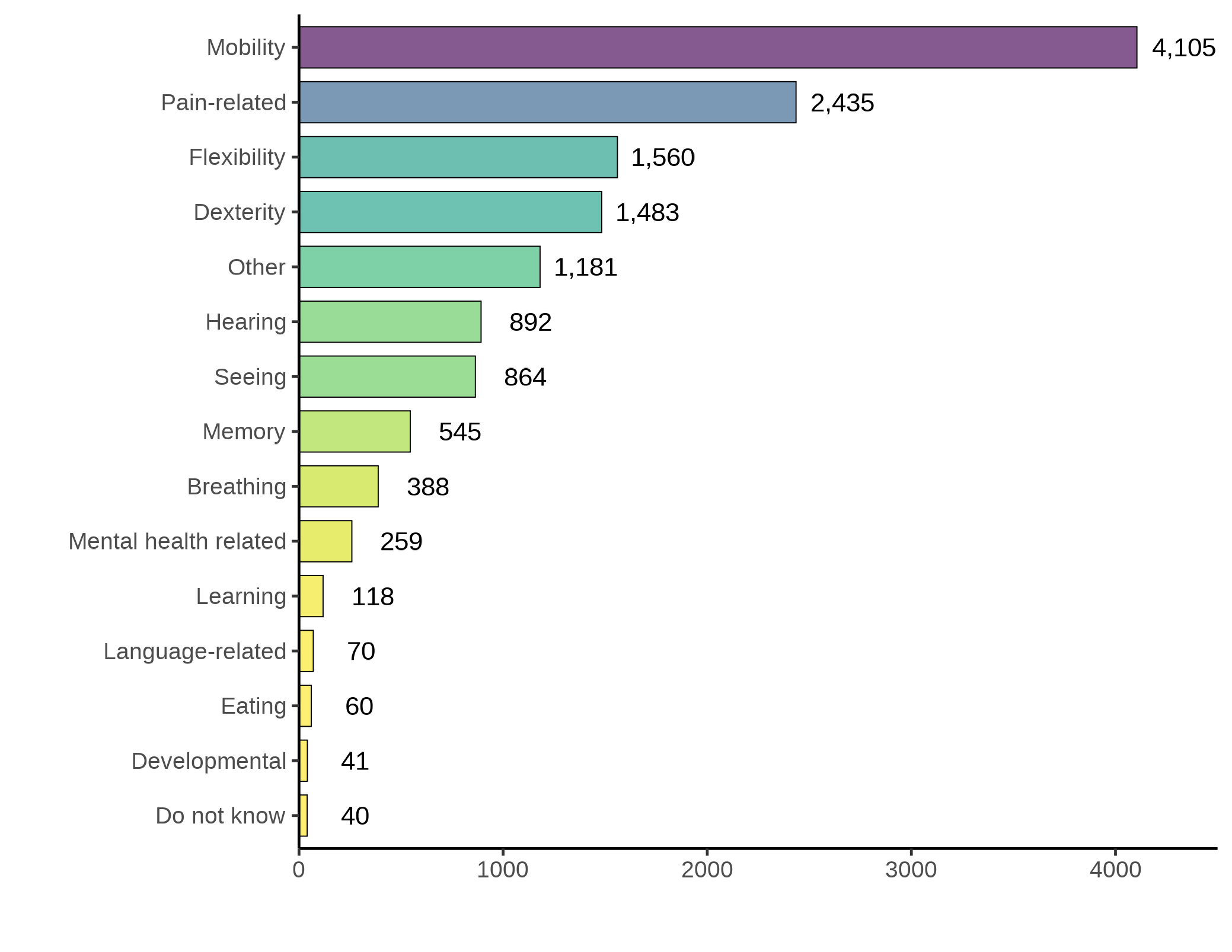

Figure 4.4a outlines the types and frequency of reported disabilities among MAID recipients who self-identified as having a disability. The most frequently reported disabilities were mobility (reported by 4,105 people) and pain-related (reported by 2,435 people). These findings are similar to those reported for 2023.

Figure 4.4a - Text description

| Type of disability | Count |

|---|---|

| Mobility | 4,105 |

| Pain-related | 2,435 |

| Flexibility | 1,560 |

| Dexterity | 1,483 |

| Other | 1,181 |

| Hearing | 892 |

| Seeing | 864 |

| Memory | 545 |

| Breathing | 388 |

| Mental health related | 259 |

| Learning | 118 |

| Language-related | 70 |

| Eating | 60 |

| Developmental | 41 |

| Do not know | 40 |

Explanatory note:

- More than one option could be selected. Totals will exceed 100%.