Safe Long Term Care Act engagement: What we heard report

On this page

- Introduction

- Context and overview of the consultation process

- What we heard during meetings and through the online consultation

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: List of Questions, Online Questionnaire

- Appendix B: Data on Respondent Demographics, Online Questionnaire

- Appendix C: List of Participating Organizations

Introduction

Every person in Canada deserves to live in dignity, safety, and comfort. While the majority of people in Canada want to age closer to home and their family, if they need long-term care (LTC), they expect and deserve it to be high quality and safe.

Recognizing the need to improve the quality, safety, equity and availability of LTC services across Canada, we are developing a Safe LTC Act. It will complement recent federal investments, including:

- $1 billion for a safe LTC fund for provinces and territories to protect people living and working in LTC, through the 2020 Fall Economic Statement

- $10.7 million, since 2020, to Healthcare Excellence Canada to enable 1,500 LTC and retirement homes to implement promising practices for preventing and addressing COVID-19 infection and address gaps in the safety and quality of care

- $3 billion over 5 years, starting in 2023-24, to provinces and territories to improve LTC, with a focus on workforce stability and strengthened enforcement, through Budget 2021

- $1.7 billion over 5 years to support hourly wage increases for personal support workers (PSWs), including those working in LTC, through Budget 2023

Context and overview of the consultation process

The development of a Safe LTC Act and national LTC standards are Ministerial mandate priorities.

In January 2023, we welcomed the release of complementary, independent national LTC standards from the CSA Group and the Health Standards Organization (HSO). Together, the standards focus on the delivery of safe, reliable and high-quality LTC services; safe operating practices; and infection prevention and control measures in LTC homes.

Following the release of the LTC standards, we have moved our attention to the development the Safe LTC Act. This legislation will respect provincial and territorial jurisdiction: it won't mandate standards or regulate LTC delivery. Instead, it will outline guiding principles to support quality and safety in LTC.

To inform the development of the Safe LTC Act, we heard from provinces and territories, other federal departments, Indigenous Peoples, stakeholder organizations, academics, as well as LTC residents, staff and caregivers in 5 different forums:

- Three officials-level roundtables in June and July 2023 (these were preceded by pre-consultation discussions with LTC experts to help inform the discussions)

- Multiple meetings with interested organizations from across Canada

- Meetings with provinces and territories

- Discussions with federal government departments and presentations at federal inter-departmental committees

- Two roundtables in November 2023 hosted by the Minister of Health and the Minister of Labour and Seniors

We also reviewed findings from previous complementary Indigenous engagement activities in relation to the co-development of distinctions-based Indigenous health legislation, a Long-Term and Continuing Care Framework, as well as the national LTC standards developed by the CSA Group and the HSO.

Learn more about the co-development of distinctions-based Indigenous health legislation

To reach the broader public in Canada, we hosted a bilingual online consultation from July 21 to September 21, 2023. Participants could share their thoughts through an online questionnaire, via mail and via email (LTC-SLD@hc-sc.gc.ca). The questionnaire included 6 thematic questions, plus a specific question for individuals who self-identified as Indigenous on culturally safe LTC services. Efforts were made to obtain responses from a diverse range of participants (such as minority groups, rural residents) through use of a targeted email campaign and amplification by other relevant departments, including Employment and Social Development Canada and Indigenous Services Canada.

We received a total of 5,140 responses to the questionnaire. Most responses (4,631) were from individuals; the remaining 410 responses were from representatives of organizations; and 99 selected "prefer not to answer." Fifty organizations sent in formal written briefs.

The feedback gathered helped to identify potential themes and principles to inform a Safe LTC Act, as outlined below.

What we heard during meetings and through the online consultation

Principle 1

Continuum of care: acknowledges that LTC is 1 part of a continuum of supportive care, supported by intersectoral collaboration, and that most people would prefer to live in the community, with access to home and community care

Long-term care must be seen in this light, as a necessary support to aging... We need to support the aging process everywhere, all the time, in order to act preventively and lend collective assistance to our seniors (think of initiatives such as "Age-Friendly Municipalities"). Long-term care must be part of this continuum, which includes care at home for as long as patients wish, and assistance and support for family caregivers by default.

‒ Caregiver, Québec

We heard first and foremost that most people would prefer to age at home with necessary supports rather than in LTC. Despite this reality, accessing adequate home care services can be challenging: limited publicly-funded services are available and accessing additional services out-of-pocket can be costly. We heard that this results in many low-to-medium-income individuals going into LTC before it is needed. There is also pressure on family members and loved ones to fill in gaps in care.

To help address these concerns, suggested solutions included:

- remunerating caregivers

- providing tax credits to support people staying in their homes

- providing direct funding for individuals and families to purchase the care and services they want and need

- fostering the development of small, home-like residences that facilitate independent living through provision of individualized services, including for people with dementia

Participants noted that, considering the aging population and long LTC waitlists, there is a need for new LTC infrastructure to accommodate those who cannot be cared for safely in their home (particularly those with dementia). Many noted the need to treat LTC as a component of the continuum of care that is connected to community support services and primary care, with supports for transitional care. To achieve this objective, it was suggested that it is first important to better outline the roles and responsibilities of the federal government, provincial and territorial governments and local Indigenous governments. Some cited the need for enhanced intersectoral collaboration and communication to this end, for example though multi-jurisdictional/interdisciplinary committees or working groups. Such groups could support planning over the longer-term, with the involvement of residents, caregivers, family members and workers.

Many also cited the need to look to countries such as Denmark, that prioritize in-home and community supports over institution-based care.

Read about the delivery of LTC services in Denmark

Participants cited several models present in Canada and abroad that support aging in the community, which could potentially be implemented more widely. Examples include:

- Life Plan Communities

- Age-friendly communities

- House of Generations in Denmark

- Program of All-Inclusive Care for the Elderly

Comments were also raised regarding the need to focus on end-of-life, with a more embracive and palliative philosophy of care, highlighting a connection in the continuum of care between LTC and end-of-life care. Participants also noted the importance of offering palliative care earlier in the process, so that pain and symptoms are treated in early stages.

Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous people who participated in complementary Indigenous engagement activities noted that LTC should be seen as part of a holistic continuum of care that encompasses Indigenous ways of knowing and being. One of their biggest challenges is supporting their seniors so that they remain close to family and supports within their home communities.

Younger persons with disabilities

Younger persons with disabilities noted the particular issues surrounding institutionalized LTC for this commonly overlooked minority population. It was emphasized in discussions that, first and foremost, LTC homes are not and will never be a suitable place for younger persons with disabilities to live, and that they are not an appropriate alternative to care in the community or in the home. The lack of agency and autonomy for residents render LTC homes unsafe for the mental health of younger people. It was emphasized that allowing persons with disabilities to live at home and in their communities should be the focus, and independent living as the goal.

Principle 2

Meaningful quality of life: supports holistic care and accommodations that value the respect, autonomy, dignity, personal goals, and individuality of residents and is focused on overall wellness

When thinking about LTC in particular, clinical and business indicators are important but if you ask a person who lives in LTC what is important to them, they won't talk about wounds, falls, finances, medications, etc. They will say...it's having a friend, having my family/friends around me, living in a place that's clean and there are meaningful things to do during the day, evening and weekend. being cared for by people who care about me and are like my family (and the number of staff is sufficient to support my health and well-being)...having opportunities to give back to others, being part of decision-making. We have to stop the paternalistic attitude in providing care where they exist. People need information to make their decisions, but the doctor, nurse or others may not know what is important for a resident. They may not want them to take a risk, but we all take risks everyday.

‒ LTC provider and spouse/family member of a LTC resident, Ontario

Participants emphasized the need for person-centred care that supports quality of life and respects the independence, dignity and choice of LTC residents. They cited several models present in Canada and abroad which could potentially be implemented to this end. Examples include:

- Butterfly Approach

- Green House Project

- Eden Alternative model

- Hogeweyk dementia village in the Netherlands

- Humanitas Retirement Village in the Netherlands

Some participants suggested using less clinical terminology to emphasize identity and inclusivity for those living in LTC. Some examples discussed include the following:

- "LTC Home", rather than "facility" or "institution"

- "Person-centred" or "resident-centred", rather than "patient-centred"

- "Proches" ("loved ones") and "ami(e)s" ("friends") rather than just "family"

- Generally switching language towards "quality of life" rather than "safety" and "[medical] care"

Participants mentioned 3 other areas that contribute to meaningful quality of life.

Balancing risk and safety

Some participants emphasized the importance of joy in LTC and the right of residents to live with risk while balancing fellow residents' right to safety. This means that residents can choose to participate in fulfilling activities, even if there is some risk of harm. Several commented on the isolation LTC residents experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic and the negative impacts this had on their mental health and quality of life.

Infrastructure and built environments

Several participants spoke to the need for things like single rooms (or shared rooms for couples), private washrooms, improved air quality, smaller and more home-like models, natural light, outdoor spaces, accessible gyms and modern design to support resident comfort and quality of life.

Family and other informal caregivers

Many participants emphasized the need to recognize family and other informal caregivers as true partners in care. Caregivers who provide care to family and friends, both in the community and in LTC, are essential to supporting the wellbeing of seniors and persons living with a disability. It is also important to ensure that LTC staff can spend one-on-one time with residents. In this vein, many advocated for safe staffing levels, noting that "the conditions of work are the conditions of care."

What experts say about staffing in LTC

Responses related to staffing are explored in greater depth later in the report under Principle 4.

Principle 3

Inclusion: supports care and workplaces that are culturally-safe, non-discriminatory, and trauma-informed and LTC homes that are inclusive, respectful and value the diversity of those who live and work there

We heard that the Safe LTC Act must prioritize inclusion and respond to diversity in terms of age, gender and sexual orientation, ethnicity, language, experiences with trauma, religious beliefs and other factors. Participants noted gaps in the current system, where the needs of different populations are not always met.

It was noted that 2SLGBTQI+ persons (including non-binary persons) may feel unsafe and unable to express themselves freely in LTC settings. Younger people with disabilities noted feeling out of place in LTC, as the activities and food tend to cater to older people. They also cited accessibility barriers. Indigenous people living in LTC also called for access to cultural programming that incorporates traditional foods, practices, ceremonies and language.

Language barriers were also noted. While it is important for residents to have access to care in the language of their choice, we heard that staff are often not available to meet this need. For example, we heard that Francophones outside of Québec are often receiving care from unilingual Anglophone providers. Indigenous Elders face similar language barriers when receiving care from non-Indigenous staff.

Participants reminded us that LTC is primarily care for women, by women. Based on Canadian Institute for Health Information data, 64% of LTC residents are female; this increases up to 72% among residents who are aged 85 and older. PSWs provide the bulk of care. Based on data from Statistics Canada, 87% of PSWs are women and 35% are newcomers. Given the complexity of care needs of the residents they serve, it is important to ensure this workforce is well-supported.

Information references:

Participants offered ideas to help provide a safe and inclusive environment, both for residents and for staff. The examples included developing:

- culturally- or identity-specific homes, floors, or "pods"

- principles of equity, diversity, and inclusion applied to the workforce

- policies to address violence, homophobia, transphobia, racism and misogyny in LTC settings

- LTC homes that are more accessible and affordable (especially for persons with specialized needs)

- inclusive language policies to address the needs of official language minorities, such as having more staff who can speak French

- practices to include LTC residents and family members in decision-making (for example, through the use of resident and family councils)

- buildings and environments that meet the needs of persons with disabilities and persons living with dementia, with a particular focus on the experiences and needs of younger persons with disabilities requiring support

Cultural safety

Health Care (and Long-Term Care in particular) is drastically understaffed and definitely not practicing any cultural sensitivity training amongst the staff. There needs to be a facility in at least 1 of the Inuit communities in Labrador. Elders are being sent to HVGB [Happy Valley-Goose Bay] to die....to die of old age....to die of health conditions....to die of loneliness....to die of disconnection to the only culture and life that they've ever known. The Innu of Sheshatshiu have taken it upon themselves to build a long-term care facility in their community to ensure that Innu elders are able to stay home in their community surrounded by their family and their culture. This brand new facility should be a model for all indigenous communities to follow in the interest of everyone's well being.

‒ Inuit caregiver and spouse/family member of LTC resident, Newfoundland and Labrador

The public consultation's online questionnaire included a specific question directed to those self-identifying as Indigenous (and for organizations serving Indigenous Peoples), which asked about what it means to support cultural safety for First Nations, Inuit and Métis people in LTC. Several themes emerged in the responses:

- The importance of feeling safe and receiving care that is free from racism and discrimination.

- The need for more access to LTC services in Indigenous communities, so Elders do not need to leave their families and loved ones to receive the care they need.

- The need to incorporate Indigenous cultures and languages into LTC settings. This includes things like access to traditional foods and medicines, space for ceremony, access to people who speak Indigenous languages, and recognition of relevant holidays such as National Indigenous Peoples Day and the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation.

- The need for more Indigenous-led LTC services, greater involvement of Indigenous people in LTC policy and planning and recruitment of Indigenous staff. Some participants suggested having Indigenous patient navigators or ambassadors that could advocate for First Nations, Inuit or Métis residents and work with LTC staff to promote understanding of Indigenous cultures and history.

- The need for person-centred care that is trauma-informed. This means that LTC staff ought to have an understanding of the ongoing impacts of colonialism, and the trauma left by Residential School and Indian Day School systems, the Sixties Scoop and other forms of abuse and discrimination, and that staff must be sensitive to these realities in the provision of care. It also means understanding that, given previous experiences of abuse by the state and health care professionals, that many Indigenous people will be wary of entering an institutional setting. As such, it is important to ensure that going into LTC does not reinvoke this trauma.

Principle 4

Quality care and safety: supports integrated, evidence-based care provided by a diverse, qualified, and well-supported workforce in safe and clean environments

I love working in LTC. I respect and love our residents. I often leave work in tears as I know I did the best I could, but that did not equal what was best for the residents. As much as they need medication, treatments, food and drink, they need to feel cared for. Staff do not have the time to sit and talk to them when they need us - unless it is urgent. Sometimes they are lonely, a tv or sitting with non-verbal co-residents doesn't cut it. They want to talk about their lives, their family, their past and we, as staff have to rush out to get to the next resident. LTC sites are so underfunded it is disgusting. Our staff often go without breaks, we are so tired. We are working double shifts, short staffed and going without breaks. Please, please, please - get us the staffing levels we need to ensure the care of our residents....and preserve our healthcare workers...not sure how long we can keep going.

‒ LTC Provider, Alberta

Many participants shared personal stories about family members and loved ones living in LTC. While some were satisfied with the care received, others felt it was inadequate, often due to a lack of staff. Participants encouraged adequate staffing levels (many specifically cited the need to provide 4.1 direct care hours per resident per day, which is commonly cited as the average minimum number of direct care hours required to support safe resident care).

Many expressed needing to consistently provide additional care themselves and/or needing to advocate on the resident's behalf. In a similar vein, some participants expressed fear about reporting inadequate or inappropriate care out of fear that this could have repercussions (i.e., staff could take out frustrations on the resident). Many suggested having some form of whistleblower protection.

Participants supported streamlining recruitment of international workers to address staffing shortages, while acknowledging some expressed concerns about how language barriers and differences in training could affect quality of care. They called for limited reliance on temporary foreign workers in LTC (based on concerns that these workers may be asked by employers to do work outside their scope of practice and would be unlikely to refuse due to fear of losing employment and/or being deported). Participants also suggested reducing reliance on agency staff (based on concerns with respect to the accountability of agency staff as well as quality and continuity of care).

We heard from many participants that the LTC workforce faces significant challenges related to job stability, wages, training as well as staff shortages. Participants called for a variety of measures to improve staffing in LTC, and in turn, quality and safety of care for LTC residents. Examples include:

- Promoting LTC as a desirable profession to support increased recruitment

- Providing advancement and professional development opportunities for LTC staff

- Ensuring equity of wages across home care, LTC and acute care to avoid shortages in a particular sector

- Ensuring that staff workloads are reasonable and manageable; limiting or eliminating mandatory overtime work

- Developing a pan-Canadian health human resource strategy, to plan for future increased demand for supportive care services

- Regulating PSWs and standardizing education and an occupation name for this profession, to support consistency and quality of care

- Providing more specialized training to LTC staff in topics such as palliative care, dementia care and infection prevention and control

- Addressing the often precarious working conditions of LTC staff by providing higher pay, full-time hours and workplace benefits. Some suggested more unionization of the workforce to this end

There were calls to not only to look at resident to staff ratios, but also to consider the other types of care that need to be provided, such as recreational care and mental health support. It is important to have access to a range of specialized providers to support multidisciplinary, team-based care that includes professionals such as:

- physiotherapists

- occupational therapists

- nutritionists and dieticians

- social workers and counsellors

- dentist, dental hygienists and therapists

At a more micro-level, other common quality and safety concerns for LTC residents that were raised include nutrition and diet (such as access to safe foods for people with celiac disease or food allergies) and the overall quality of food, as well as things like frequency of brief changes and baths, which ties back to adequate funding and staffing.

For participants, quality of care also included improvements to LTC home infrastructure, such as the need for:

- single rooms

- person-centred design

- reliable internet access

- good indoor air quality

- more facilities and beds

Many participants wanted to see more leadership from the federal government and a uniform approach across Canada with respect to the quality and safety of LTC. Some suggested that this could be achieved by including LTC in the Canada Health Act or by mandating the new national LTC standards (developed by the CSA Group and the HSO). Many suggested that federal funding to provinces and territories should be tied to implementation of the new standards or meeting other performance metrics aimed at improving quality and safety in the sector. Others felt the opposite way and did not see the need for further federal involvement in LTC. Instead, they wanted to see the federal government increase funding to provinces and territories so they can make improvements according to their own priorities.

LTC operators, while supportive of standards for the most part, emphasized the need for adequate and sustainable funding to support:

- staffing

- implementation of standards

- infrastructure improvements

- facility accreditation

Some participants encouraged reflection on whether LTC should be delivered uniquely by not-for-profit organizations noting that the pursuit of profits can come at the expense of quality care. No matter what the sentiment, however, it was acknowledged that the current provision of LTC by provinces and territories includes the public non-profit and for-profit sectors, and such a change would be a complex undertaking.

Principle 5

Transparency: facilitates data collection to support continuous measurement, innovation, and improvement and to evaluate progress toward care and accommodations that balance safety and quality of life, and reporting back to people in Canada on a regular basis

Transparency and accountability were topics of paramount importance among participants as a means to ensure value for public dollars spent on LTC. Stakeholders called for better information and reporting on the state of LTC in Canada. There are existing efforts to collect data across the supportive care sector and report back to people in Canada, but there are significant gaps.

In terms of how public reporting could be enhanced, nine common suggestions arose:

- Support the uptake and upgrading of interRAI and other data tools.

- Collect data on employees working in LTC though the Census (Statistics Canada).

- Ensure data is consistent and comparable via shared indicators and benchmarks.

- Report on how federal funding for LTC is being spent by provinces and territories.

- Collect self-reported resident and family data, notably measures of quality of life and satisfaction.

- Produce reports that are plain language, easily located and accessible to all and mandate regular public reporting.

- Inspect LTC homes on a frequent basis and making these inspections unannounced; follow through on the recommendations of LTC inspections.

- Ensure reporting is independent, for example done by a third party. The Office of the Seniors Advocate in British Columbia was cited as an example that could be implemented more broadly. In this vein, several participants suggested creating an LTC ombudsperson or seniors advocate at the federal level.

- Collect palliative care metrics, including treatment of pain and symptoms, end-of-life symptom medication prescribing, advance care planning discussions (quality and frequency), accuracy of prognosis, whether residents receive care in line with their wishes, hospital transfers, location of death, and access to palliative care specialists.

Current quality and evaluation metrics in long-term care homes are entirely clinical in nature. Moving forward, it is imperative that each province and territory develop (and place greater emphasis on) quality of living indicators, as defined by residents themselves. What factors make a good home or living experience for residents? Ask them!

‒ Ontario Association of Residents' Councils

While most participants support increased reporting and oversight mechanisms, some expressed caution that too much of this can take staff time away from providing care.

A number of participants referenced the need for a pan-Canadian public report on the state of LTC. There was also a call for a framework and action plan that will articulate a strong vision for quality of life in LTC and tools for measurement.

Overall, participants highlighted the importance of ongoing collaboration, consultation, and communication with provinces and territories, LTC operators, Indigenous Peoples, LTC residents, families, and staff, and other stakeholders throughout implementation and decision-making processes.

Conclusion

We thank all who participated in the engagement on the development of the Safe LTC Act. The feedback received from stakeholders, experts, provincial and territorial governments, residents and family caregivers, health care workers, and Indigenous Peoples, was wide-ranging and very informative. The perspectives are being taken into consideration as we work to table the legislation by the end of 2024. We remain committed to ongoing collaboration and discussions with all partners as we work to improve LTC in Canada, so all people in Canada may have access to high quality and safe care no matter where they live.

Appendix A: List of questions, online questionnaire

Preliminary question for respondents identifying as Indigenous and organizations serving Indigenous communities only:

Based on your knowledge and experiences, what does it mean to support culturally safe and appropriate LTC services for First Nations, Inuit and/or Métis Peoples?

Question 1:

How should governments and stakeholders cooperate to improve the quality and safety of LTC?

Question 2:

How can governments and stakeholders cooperate to help foster the implementation of the new national LTC standards?

Question 3:

How can governments and stakeholders cooperate to address health human resources challenges in LTC, including staff retention and recruitment?

Question 4:

How should we enhance public reporting on LTC to strengthen transparency and accountability in the sector?

Question 5:

What type of information would you like to see in a Pan-Canadian public report on LTC?

Question 6:

Please share any additional thoughts you have on LTC.

Appendix B: Data on respondent demographics, online questionnaire

Individuals

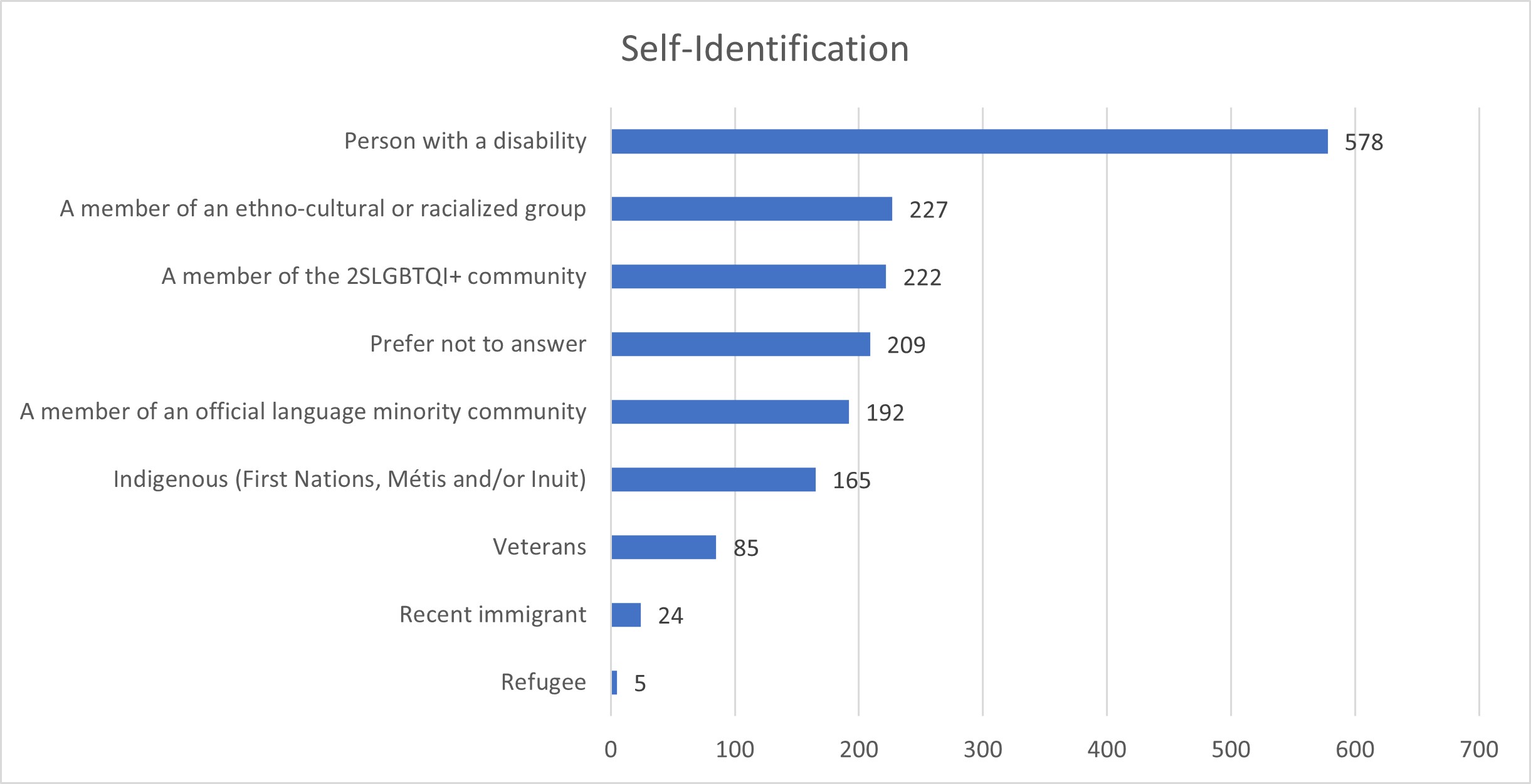

Self Identification

| Self-Identification | Count |

|---|---|

| Refugee | 5 |

| Recent immigrant | 24 |

| Veterans | 85 |

| Indigenous (First Nations, Métis and/or Inuit) | 165 |

| A member of an official language minority community | 192 |

| Prefer not to answer | 209 |

| A member of the 2SLGBTQI+ community | 222 |

| A member of an ethno-cultural or racialized group | 227 |

| Person with a disability | 578 |

Notes: respondents could select more than 1 option; chart does not include "none of the above" entries (54.9% of respondents selected this option)

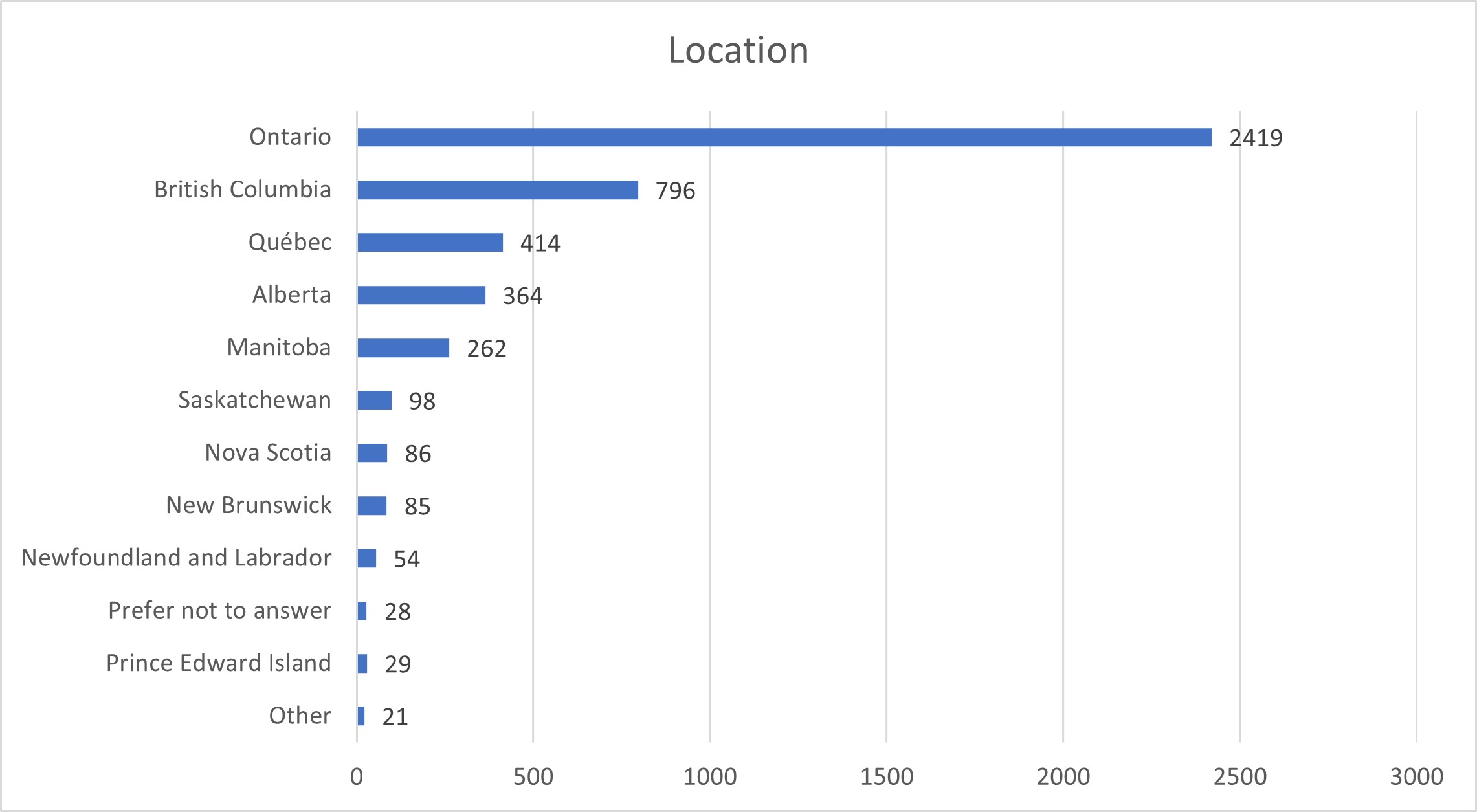

Location

| Location | Count |

|---|---|

| Other | 21 |

| Prince Edward Island | 29 |

| Prefer not to answer | 28 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 54 |

| New Brunswick | 85 |

| Nova Scotia | 86 |

| Saskatchewan | 98 |

| Manitoba | 262 |

| Alberta | 364 |

| Québec | 414 |

| British Columbia | 796 |

| Ontario | 2419 |

Note: This chart excludes the Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut as there were fewer than 10 respondents from each of the territories.

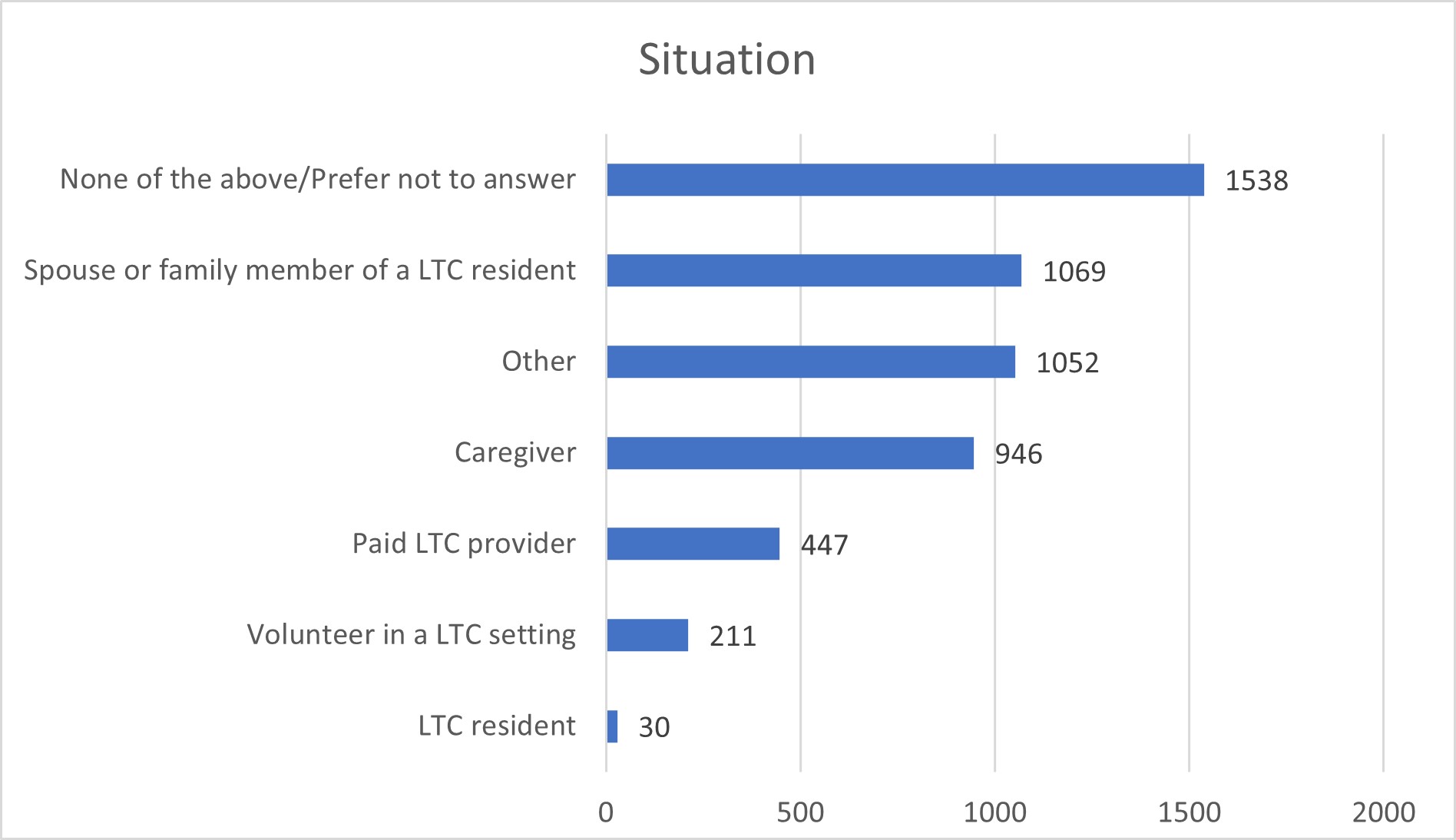

Situation

| Situation | Count |

|---|---|

| LTC resident | 30 |

| Volunteer in a LTC setting | 211 |

| Paid LTC provider | 447 |

| Caregiver | 946 |

| Other | 1052 |

| Spouse or family member of a LTC resident | 1069 |

| None of the above/Prefer not to answer | 1538 |

Note: respondents could select more than 1 option

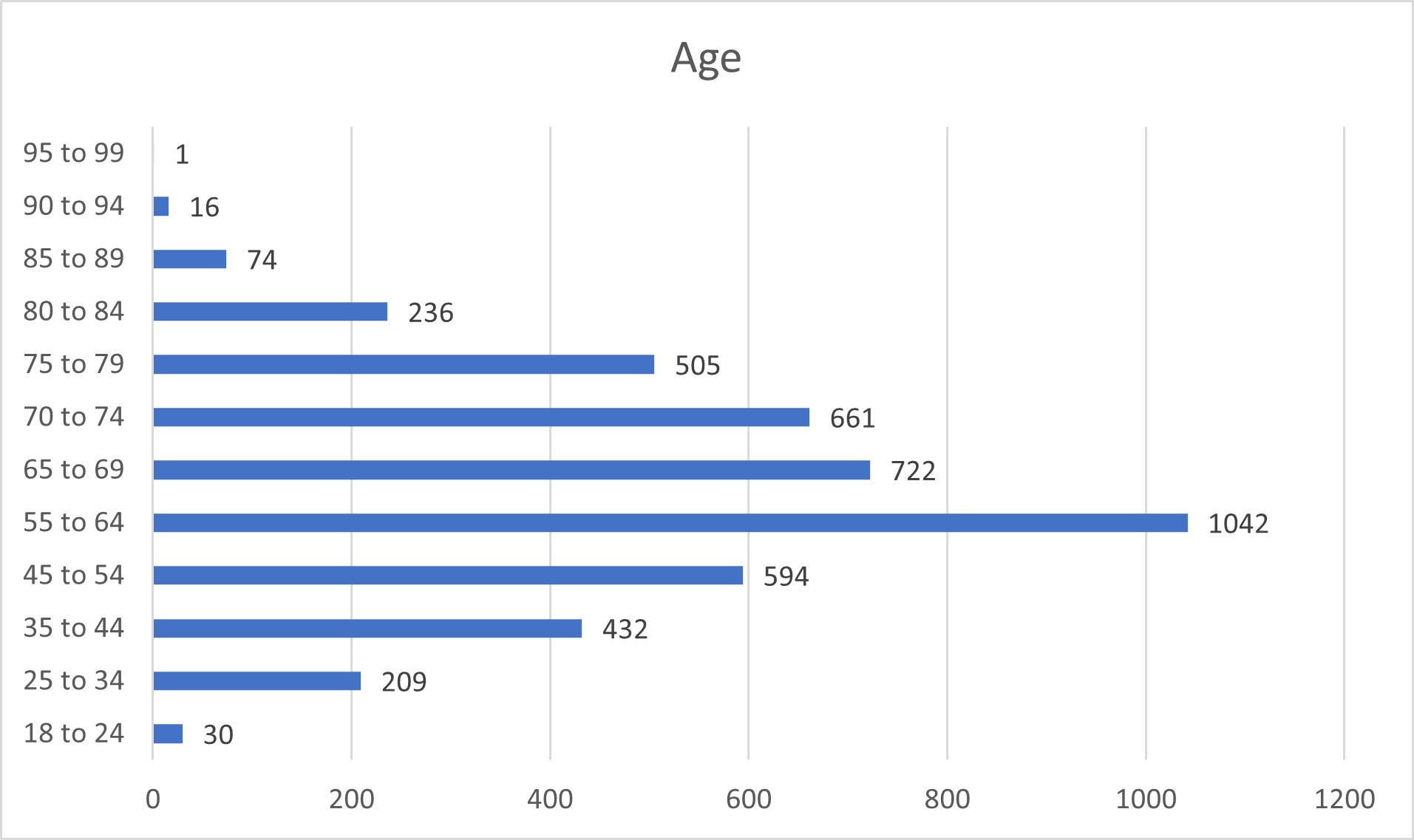

Age

| Age | Count |

|---|---|

| 18 to 24 | 30 |

| 25 to 34 | 209 |

| 35 to 44 | 432 |

| 45 to 54 | 594 |

| 55 to 64 | 1042 |

| 65 to 69 | 722 |

| 70 to 74 | 661 |

| 75 to 79 | 505 |

| 80 to 84 | 236 |

| 85 to 89 | 74 |

| 90 to 94 | 16 |

| 95 to 99 | 1 |

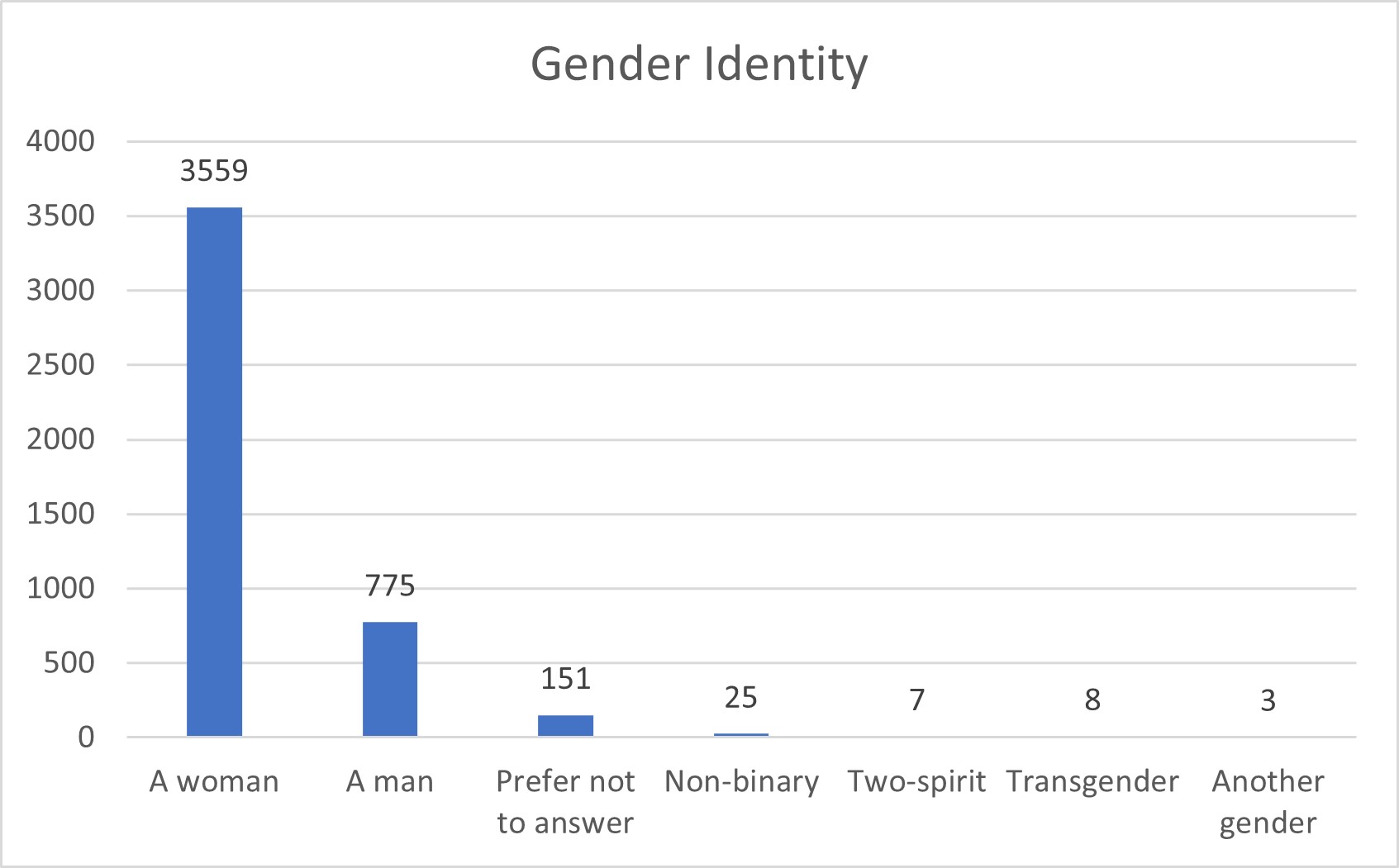

Gender Identity

| Gender | Count |

|---|---|

| A woman | 3559 |

| A man | 775 |

| Prefer not to answer | 151 |

| Non-binary | 25 |

| Two-spirit | 7 |

| Transgender | 8 |

| Another gender | 3 |

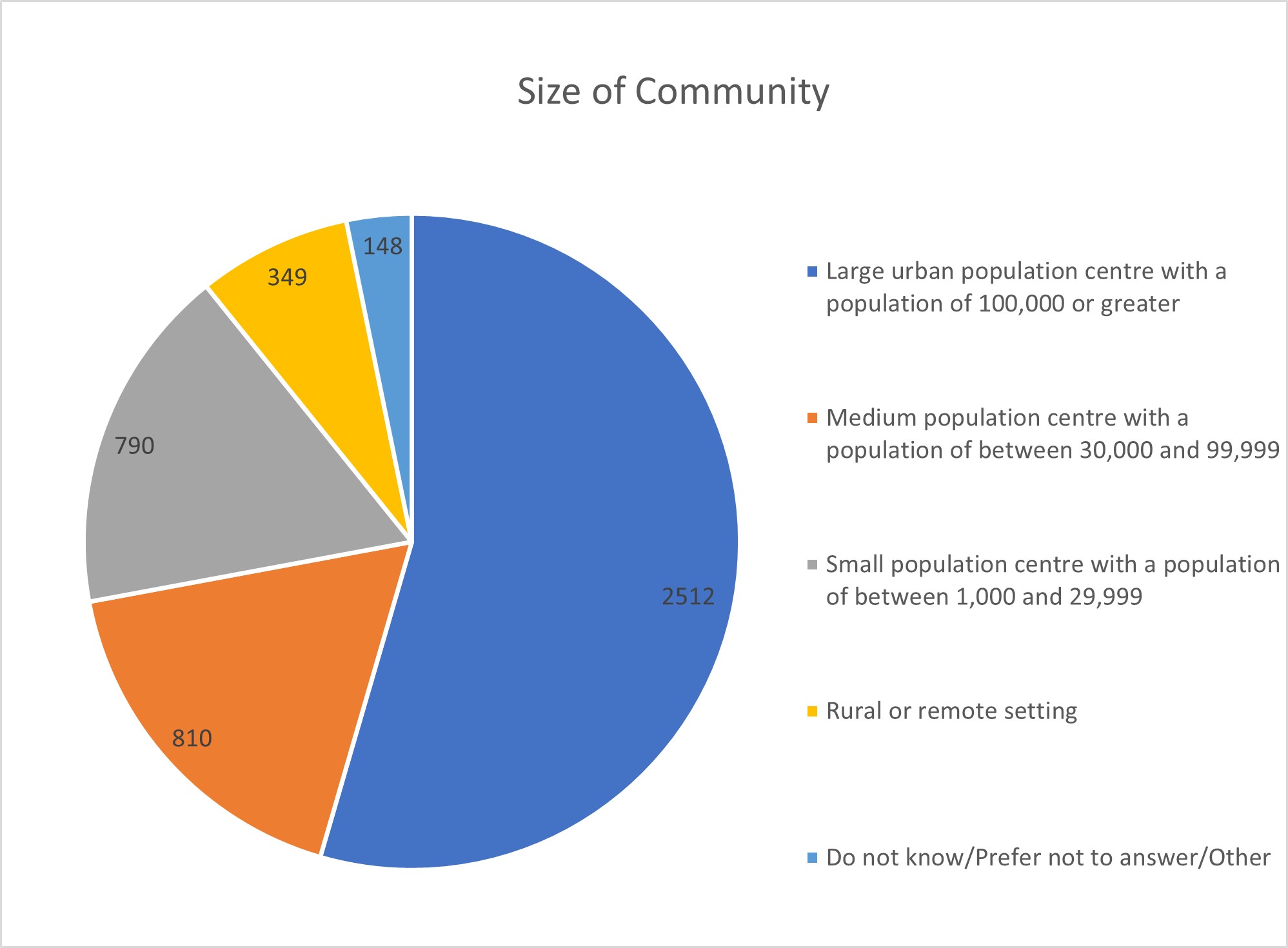

Size of Community

| Size of Community | Count |

|---|---|

| Large urban population centre with a population of 100,000 or greater | 2512 |

| Medium population centre with a population of between 30,000 and 99,999 | 810 |

| Small population centre with a population of between 1,000 and 29,999 | 790 |

| Rural or remote setting | 349 |

| Do not know/Prefer not to answer/Other | 148 |

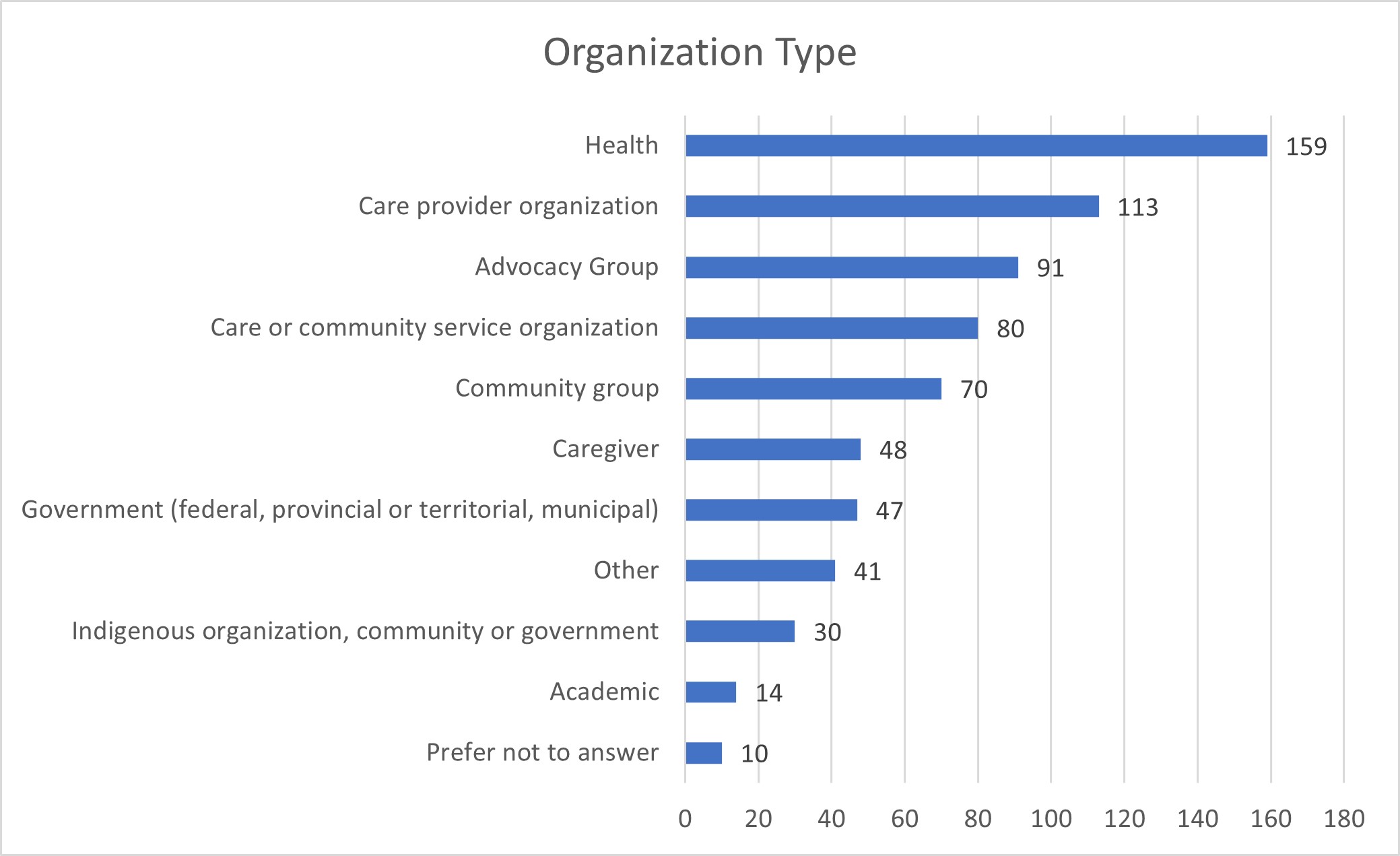

Organizations

Organization Type

| Type | Count |

|---|---|

| Prefer not to answer | 10 |

| Academic | 14 |

| Indigenous organization, community or government | 30 |

| Other | 41 |

| Government (federal, provincial or territorial, municipal) | 47 |

| Caregiver | 48 |

| Community group | 70 |

| Care or community service organization | 80 |

| Advocacy Group | 91 |

| Care provider organization | 113 |

| Health | 159 |

Note: Respondents could select more than 1 type

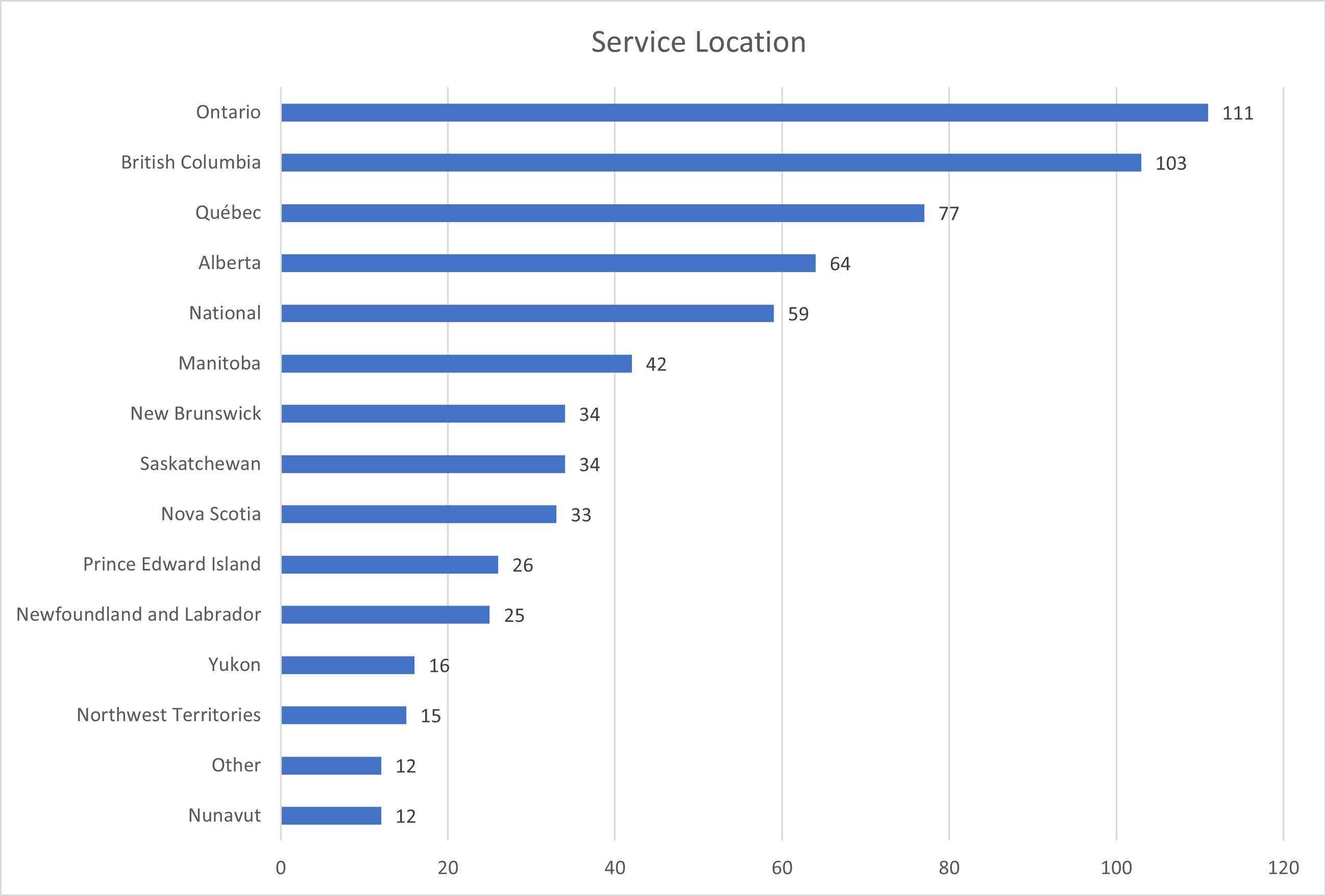

Service Location

| Location | Count |

|---|---|

| Nunavut | 12 |

| Other | 12 |

| Northwest Territories | 15 |

| Yukon | 16 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 25 |

| Prince Edward Island | 26 |

| Nova Scotia | 33 |

| Saskatchewan | 34 |

| New Brunswick | 34 |

| Manitoba | 42 |

| National | 59 |

| Alberta | 64 |

| Québec | 77 |

| British Columbia | 103 |

| Ontario | 111 |

Note: Respondents could select more than 1 service location

Appendix C: List of participating organizations

Pre-engagement and roundtable participants

- AGE-WELL, Canada's Technology and Aging Network

- Alzheimer Society of Canada

- Canadian Association of Continuing Care Educators

- Canadian Association on Gerontology

- Canadian Association for Long Term Care

- Canadian Association of Social Workers

- Canadian Health Coalition

- Canadian Indigenous Nurses Association

- Canadian Institute for Health Information

- Canadian Labour Congress

- Canadian Network for the Prevention of Elder Abuse

- Canadian Nurses Association

- Canadian Union of Public Employees

- CanAge

- CARF (Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities) Canada

- Coalition for Seniors and Nursing Home Residents' Rights

- Congress of Aboriginal Peoples

- Congress of Union Retirees of Canada

- Council of Seniors Citizens' Organizations of British Columbia

- CSA Group

- Eastern Health Resident and Family Advisory Council

- Family Councils Ontario

- HEAL, Organizations for Health Action

- Health Standards Organization

- Healthcare Excellence Canada

- Inclusion Canada

- Kensington Health

- Migrant Workers Alliance for Change

- Mon Sheong Foundation

- National Seniors Council

- National Union of Public and General Employees

- National Institute on Ageing (Toronto Metropolitan University)

- Nova Scotia Centre on Aging

- Public Service Alliance of Canada

- Registered Nurses' Union, Newfoundland & Labrador

- Royal Society of Canada, Working Group on Long-Term Care

- Réseau FADOQ

- Schlegel-UW Research Institute for Aging

- Service Employees International Union (SEIU Healthcare)

- Société Santé en français

- United Food and Commercial Workers Union

- United Steelworkers Union

- York University Centre for Aging Research and Education

Bilateral and ad hoc meetings

- Alzheimer Society of British Columbia

- Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions

- Canadian Society of Nutrition Management

- Celiac Canada

- Dental associations (Canadian Dental Hygienist Association, Denturists Association of Canada and Canadian Dental Therapists Association)

- Disability Without Poverty & MS Canada

- First Nations and Inuit Health Branch, Indigenous Services Canada

- Fondation Émergence

- Inclusion Canada

- Ontario Association of Residents' Councils

- Ontario Society of Professional Engineers

Online questionnaire respondents

- 411 Seniors Centre Society

- AbbVie Canada

- Access to Seniors and Disabled

- ACE Team (Advocates for the Care of the Elderly), Nova Scotia

- Action Bénévole de la Rouge

- Action Not Words

- Advancement of Women Halton

- AdvantAge

- AgeCare

- AGE-WELL, Canada's Technology and Aging Network

- Aging in Place Exchange Network

- Albatros Drummondville

- Alberta Council on Aging

- Alberta Health Services

- Algonquins of Pikwakanagan Home & Community Care Program

- Alzheimer Society of Canada

- Alzheimer Society of Alberta and Northwest Territories

- Alzheimer Society of British Columbia

- Assemblée de la francophonie de l'Ontario

- Association des proches aidants de la Capitale-Nationale

- Association des retraitées et retraités de l'éducation et des autres services publics du Québec

- Association québécoise de défense des droits des personnes retraitées et préretraités

- Association québécoise des pharmaciens propriétaires

- Association of Municipalities of Ontario

- ATK Group Ltd - River Glen Haven Nursing Home

- Baptist Housing Seniors Living

- Barren Lands First Nation

- BC Care Providers Association

- Bethany Group

- Bharat Bhavan Foundation

- Birdtail Sioux Health Centre

- British Columbia Nurses' Union

- Broadmead Care

- Canadian Association for Long-Term Care

- Canadian Association of Occupational Therapists

- Canadian Association of Social Workers

- Canadian Association on Gerontology

- Canadian Cancer Society

- Canadian Coalition for Seniors' Mental Health

- Canadian Dental Hygienists Association

- Canadian Federation of Nurses Unions

- Canadian Labour Congress

- Canadian Medical Association

- Canadian Nurses Association

- Canadian Physiotherapy Association - Seniors Health Division

- Canadian Society of Nutrition Management

- Canadian Society of Palliative Care Physicians

- Canadian Federation of Mental Health Nurses

- Canadian Federation of University Women - Healthcare Committee, Oakville

- Capilano Community Services Society

- CapitalCare

- Care Watch Ontario

- CareRx

- Commission on Accreditation of Rehabilitation Facilities (CARF) Canada

- Catholic Women's League of Canada

- Celiac Canada

- Central West Specialized Developmental Services, Oakville Health Care

- Centre Communautaire Saint Antoine 50+

- Centre d'action bénévole du Lac Saint-Pierre

- Centres d'Accueil Héritage

- Centres d'hébergement et de soins de longue durée (several service points)

- Centre hospitalier universitaire de Sherbrooke

- Centre hospitalier universitaire Dr Georges L Dumont

- Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux Centre Ouest de l'ile de Montréal

- Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux de la Mauricie-et-du-Centre-du-Québec

- Centre intégré universitaire de santé et de services sociaux de l'Ile de Montréal

- Centre intégré de santé et de services sociaux de la Côte-Nord

- Champlain Region Family Council Network

- Citizens for Change in Long Term Care, Newfoundland and Labrador

- Club 50 plus St-Yves

- Club Age d'or du Québec (FADOQ)

- Coalition du Nouveau-Brunswick pour la santé

- Cœliaque Québec

- Comité de résidents du CHSLD d'Youville à Sherbrooke

- Commission de la santé et des services sociaux des Premières Nations du Québec et du Labrador

- Community Legal Aid - University of Windsor

- Community Living Toronto

- Concerned Friends - A Voice for Quality Long-Term Care

- Constituency Seniors' Advisory Council - Ron McKinnon, Member of Parliament, Coquitlam-Port Coquitlam

- Coop Sante et Solidarité de la Famille

- Corporation des Séniors Secteur New Carlisle (Résidence Gilker)

- Dakota Ojibway Tribal Council

- Dene Tha' First Nation

- Department of Health and Wellness, Infection Prevention and Control Team, Seniors Health Division Prince Edward Island

- Deux cultures, un monde

- Devonshire Care Centre

- Eastern Ontario Wardens' Caucus

- Eel Ground Health Centre

- Elder Abuse London-Middlesex

- Emerald Gardens Retirement Residence

- Extendicare

- Extendicare Mississauga

- Family Council of Carleton Lodge

- Family Councils Ontario

- Family Services of the North Shore

- Fédération des ainées et ainés francophones du Canada

- Fédération des aînés et retraités francophones de l'Ontario

- Fédération des Citoyen(ne)s Aîné(e)s du Nouveau-Brunswick

- Filipino Heritage Society of Montreal

- Food Allergy Canada

- Fort Langley Seniors

- Fort Severn

- German Canadian Care Home

- German-Canadian Benevolent Society of BC

- Golden Manor Home for the Aged

- Good Samaritan Society

- Grove Home

- GS1 Canada

- Guardian Angels Program

- H. G. Smith and Associates

- Health PEI

- Health Quality BC

- Health Standards Organization

- Healthcare Excellence Canada

- Hilton Villa Seniors Community

- Hollow Water First Nation Adam Hardisty Health Centre

- Hospital Employee's Union

- Interior Health

- Island Health

- Killarney Service for Seniors

- Kiwanis Lodge

- Labrador-Grenfell Health

- Long Term & Continuing Care Association of Manitoba

- Long Term Care Nova Scotia

- Long Term Care Program at Veterans Affairs Canada

- Luther Court Society

- Manitoba Nurses Union

- Membertou First Nation

- Mielcare

- Migrant Workers Alliance for Change

- Mnaamodzawin Health Services

- Mont St Joseph Home

- Morgan Place

- Mountain Lake Seniors Community

- Munipalité régionale de comté de La Vallée-du-Richelieu

- Municipalité d'Aumond

- Municipalité de Marston

- National Alliance for Safety and Health in Healthcare

- National Association of Federal Retirees

- Native Women's Association of Canada

- Neptunis

- New Brunswick Continuing Care Safety Association

- New Vista Care Centre

- Newfoundland and Labrador Health Services

- Northwest Territories Health and Social Services Authority

- Nurses Specialized in Wound, Ostomy and Continence Canada

- Office municipal d'habitation de Montréal

- Office of the Federal Housing Advocate

- Ontario Association of Residents' Councils

- Ontario Long Term Care Association

- Ontario Long Term Care Clinicians

- Ontario Medical Association

- Ontario Nonprofit Network

- Ontario Patient Ombudsman

- Ontario Society of Occupational Therapists

- Oromocto First Nation

- Ouje-bougoumou Cree Nation

- Oxford Coalition for Social Justice

- Oxford County

- Palliative Support Centre, Paul Sugar Palliative Support Foundation

- Pallium Canada

- Park Place Seniors Living

- Parkinson Canada

- Parkview Nursing Centre

- Patients for Patient Safety Canada

- Perley Health

- Peterborough Public Health

- Popote Roulante de Salaberry-de-Valleyfield

- Prairie Lake Seniors Community

- Prairie Mountain Health

- Prince George Council of Seniors & The Elder Citizens Recreation Association

- Progress Place

- Qualicum Manor

- Radical Resthomes

- Récolte des générations

- Region of Durham

- Region of Peel

- Registered Nurses Association of Ontario

- Regional Municipality of York

- Regroupement des associations de personnes handicapées de l'Outaouais

- Regroupement des associations des personnes handicapées, Gaspésie–Les - Îles

- Regroupement soutien aux aidants Brome-Missisquoi

- Rekai Centre at Wellesley Central Place

- Réseau des services de santé en français de l'Est de l'Ontario

- Resident Council, Riverview Health Centre

- Rivercrest Care Centre

- River Ridge Seniors Village

- Riverview Health Centre

- Sandy Lake First Nation

- Sask Thyroid (Facebook Group)

- Saskatchewan Health Authority

- Saskatchewan Long Term Care Network

- Save Our Northern Seniors

- Seneca Polytechnic, Social Service Worker Gerontology Diploma Program

- Senior Women Living Together

- Seniors Action Yukon

- Seniors for Social Action Ontario

- Service Employees International Union (SEIU Healthcare)

- Sherwood Care

- Sienna Senior Living

- Silverado Creek Seniors Community

- Simkin Centre

- Société luçoise des personnes handicapées actives

- Société Santé en français

- Speech Language and Audiology Canada

- St Angela Merici Residence

- Statistics Canada

- Sunshine Coast Labour Council

- Tibbetts Home for Special Care

- Trail FAIR Society

- University of Ottawa, Division of Geriatric Psychiatry

- Vancouver Coastal Health, Sunshine Coast

- Villa Elegance

- Voix du Pontiac-Pontiac Voice

- Waldheim and District New Horizons Group Inc.

- Wellesley Institute

- Windigo First Nations Council, Home and Community Care Program

- Windsor Elms Village