Climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessments: Workbook for the Canadian health sector

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 3 MB, 89 pages)

Organization: Health Canada

Date published: 2022-09-12

Table of contents

- Introduction

- Health equity

- Why complete a climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment?

- How to use this workbook

- Step 1: Frame and scope the assessment

- Step 2: Describe current risks, vulnerabilities and capacities

- Step 3: Project future health risks

- Step 4: Identify and prioritize policies and programs to increase climate-resilience of health systems

- Step 5: Establish an iterative process for managing and monitoring health risks

- Step 6: Examine the potential health co-benefits and co-harms of adaptation and greenhouse gas mitigation options implemented in other sectors

- Glossary of key terms

Acknowledgements

This guidance document was authored by:

Health Canada

- Paddy Enright

- Peter Berry

- Jaclyn Paterson

- Katie Hayes

- Rebekka Schnitter

- Marielle Verret

This workbook provides step-by-step information on how to conduct a climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment. This workbook is intended for use by health officials to develop health vulnerability assessments and adaptation plans through participatory processes that engage partners from multiple sectors and organizations. Overall, it is intended to develop capacity among Canadian health authorities to assess and adapt to the health impacts of climate change.

Introduction

Climate variability and change are increasing risks to the health of Canadians. Impacts can be direct or indirect and include increased morbidity and mortality related to a greater frequency and severity of extreme weather events (e.g. extreme heat, floods, hurricanes, ice storms, droughts); increased ambient and indoor air pollution; reduced recreational and drinking water quality; increased food contamination; the spread of vectors that cause disease and greater exposure to UV radiation. Recent evidence suggests that climate change can pose long lasting threats to mental health from climate-related disasters and can result in greater food insecurity for some populations, particularly those living in northern communities.

Addressing the challenges posed by climate change requires a robust understanding of the risks posed by current climate variability, the possible impacts associated with future climate change, the unique vulnerabilities facing specific populations, communities or regions, and of effective measures to protect health. Health authorities in communities across Canada need to prepare for threats both familiar - which may present themselves at an increased frequency and/or severity (e.g. flooding, drought, extreme heat, vector-borne disease, air pollution, wildfires) and unfamiliar (e.g. exotic infectious diseases, catastrophic impacts from multiple events) which may impact both individuals and health systems.

Health equity

Population level vulnerabilities, as well as adaptive capacities, to climate change impacts are influenced not only by biological but also social and environmental factors like employment, education, housing, culture, gender, physical environment, and income. Effective measures to protect populations of concern acknowledge and address social and environmental factors that influence health outcomes so that all people have the opportunity to experience their highest level of health.

Population features that influence both vulnerability and adaptive capacity, as well as populations of concern from climate change impacts on health include:

- Gender and sex

- Race and ethnicity

- Age (including: elderly people and children)

- People with pre-existing conditions (e.g. physical and mental conditions)

- People who are unemployed or underemployed

- People who are lower-levels of formal education

- People who are socially isolated

- People with low socio-economic status

- Occupational groups (e.g. outdoor labourers and first-responders)

- Minority linguistic communities

- Rural, urban, and suburban communities

- People who are underinsured or uninsured

- People who live in high-risk geographic environments (e.g. flood plains, coastal communities)

- Newcomers to Canada

- Indigenous Peoples

The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care Health Equity Impact Assessment guideFootnote 1 provides useful information on approaches for considering unique population level vulnerabilities that may be relevant for understanding the differential risks posed by climate change on Canadians.

Indigenous Peoples are diverse and confront equally diverse issues with a range of adaptive capacities. However, due to both long-seeded systemic inequalities and changing environmental conditions, many Indigenous Peoples, particularly those in more northern and remote locations, are experiencing disproportionate impacts from climate change on wide-ranging issues. Indigenous knowledge can be a critical source of information for understanding and communicating these risks to health. This workbook was designed primarily for use by provincial/territorial ministries of health and regional health authorities; however information within the workbook may be beneficial to Indigenous communities. Additionally, non-Indigenous communities may benefit greatly from partnering with Indigenous communities in their climate change and health work and by working to equitably incorporate the knowledge held by Indigenous residents and partners into their V&A assessment.

Why complete a climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment?

Completing a climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment (V&A) can assist health authorities in identifying and interpreting information needed to prepare their health systems for the impacts of climate change. These assessments may be completed at local, regional, provincial/territorial and international scales. V&As may serve to:

- Identify resources and assess knowledge leading to a better understanding of the relationship between weather/climate and health outcomes – with emphasis on populations of concern

- Provide information on the expected distribution and severity of future climate change and health impacts to health and emergency management officials, stakeholders and the public

- Provide insight into effective means of incorporating information on the health impacts of climate change into existing policies and programs or, where needed, into the formation of new policies and programs to either reduce or prevent the health impacts of climate change

- Provide a baseline of information against which future changes in health risks related to climate change and the effectiveness of associated policies and programs may be measured

- Facilitate the development of inter-sectoral relationships and collaborations with the goal of protecting and improving health (e.g. collaborate with land-use planners to reduce the urban heat island effect)

The six steps of the assessment process are described in the following sections.

The six steps of a climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment

The six steps of a climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment are:

- Frame and scope the assessment

- Describe current risks, vulnerabilities and capacities

- Project future health risks

- Identify and prioritize policies and programs to increase climate-resilience of health systems

- Establish an iterative process for managing and monitoring health risks

- Examine the potential health co-benefits and co-harms of adaptation and greenhouse gas mitigation options implemented in other sectors

This workbook is intended for use by health officials to develop health vulnerability assessments and adaptation plans through participatory processes that engage partners from multiple sectors and organizations. Users of the document are referred to more detailed guidance for conducting assessments available in the World Health Organization (WHO) report Protecting Health from Climate Change: Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment.Footnote 2

This Workbook draws upon learnings from the first local assessments undertaken by public health authorities in CanadaFootnote 3 as pilots of the WHO guidelines and from recent research identifying key factors that increase the resilience of health systems to the impacts of climate change.Footnote 4, Footnote 5

How to use this workbook

This Workbook represents a first edition of a living document developed as part of a pilot program intended to develop capacity among Canadian health authorities to assess and adapt to the health impacts of climate change. The steps in the Workbook constitute an approach to climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment that is based on the latest knowledge of climate change and health and has been tailored to the Canadian health sector. The steps are presented in a manner that facilitates the inclusion of key partners from outside the health sector while maintaining a rigorous assessment process. The assessment may be completed in full, as presented, or in a modified fashion to meet the unique needs of your jurisdiction. However, it is recommended that all steps be considered to allow for the most thorough assessment possible. As new research becomes available current understanding on the severity and distribution of the health impacts of climate change may shift. Therefore, climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessments are iterative in nature; they should be revisited on a regular basis and updated with the most current information available.

Climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessments are commonly completed by a lead organization (e.g. a local public health authority) and a lead research team made up of health professionals that reflect a diverse range of backgrounds (e.g. epidemiologists, health promotion experts, health policy experts, etc.). This is typically done in collaboration with an advisory group made up of key stakeholders.

This workbook provides step-by-step information on how to conduct a climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment in a manner that can be shared and followed by all those involved in the assessment process. In an attempt to increase the ease of use and streamline the organization and analysis of information, the material in each step has been supplemented with a fillable template which can either be used directly as part of the assessment process or presented at meetings and workshops to help facilitate data gathering. Though these templates include example indicators and data sources, they should not be viewed as comprehensive, exhaustive, or prescriptive but rather as examples to help stimulate the assessment process. The possible health impacts of climate change differ considerably from region to region and therefore, through consultation with experts, effort should be made to use locally relevant indicators and processes.

At the onset of the assessment process it is important to devote the necessary time and effort to identify the priority climate change and health impacts in your jurisdiction. Though the impacts of climate change will be diverse, and understanding them as thoroughly as possible is desirable, it is likely that resource constraints will limit the scope of any assessment. Therefore, the possible health impacts may need to be prioritized. This can be done through a review of the relevant literature as well as through consultation with climate change and health experts. The priority health impacts identified will likely influence the diversity of stakeholders and professional backgrounds included in the assessment team.

The ultimate purpose of any climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment is to provide up-to-date information to support health policymakers in taking action to reduce the threat posed by climate change and to build climate-resilience within health systems. However, beyond this it is important to communicate the threats posed by climate change, as well as any possible protective actions, to those at risk, including the general public, but most importantly, populations of concern. For this reason the assessment should include communications materials designed to inform those at risk. This can be done most effectively if communications activities are considered throughout the assessment process.

Step 1: Frame and scope the assessment

Step 1: Overview

Before an assessment is initiated, the assessment needs to be framed and scoped. The project leads should identify:

- The assessment timeframe

- Available resources

- Climate related health risks of most interest

- Populations of concern

- Future time periods to assess risks

- Adaptation needs to be considered

- How the assessment will be managed

- A communication plan for informing partners and stakeholders.

Prior to beginning an assessment it may be beneficial to hold informal brainstorming sessions where participants (who will ideally be representative of the community and include experts in climate change and health) will scope possible priority areas for the assessment and identify possible data sources (e.g. recently completed surveys or health equity assessments).

Step 1a: Identify priority health hazards and concerns

The first decision to be made is which climate change-related health hazards to include as priority concerns for your assessment area. These are the hazards and concerns that should be focused on in the assessment. Use the Priority Health Hazards template to compile preliminary information on health outcomes and climate-related hazards of concern to identify which should be the focus for the assessment. In the template, record information on morbidity and mortality in your jurisdiction from extreme weather and climate events (e.g. heat events, floods), changes in air quality arising from changing concentrations of ground-level ozone, particulate matter or aeroallergens, and water-, food-, and vector-borne risks that can be made worse by climate change (e.g. Lyme disease and West Nile Virus).

When considering priority health hazards be sure to consider ramifications not just for individual and population health, but also for the health system itself. Table 6 presented in Step 2b may be helpful when considering who to consult on various components of the health system and their potential climatic vulnerabilities and capabilities.

When compiling this information, pose the following questions to help prioritize health concerns:

- What are the priority climate-sensitive health outcomes of concern in the study area, including both mental and physical health outcomes?

- What socio-cultural or biological factors (e.g. sex, gender, diet, age, occupation, livelihoods, reliance on the land? etc.) could contribute to making some groups more vulnerable than others?

- What are some of the differential impacts of climate change on populations of concern?

- Which climate-sensitive health outcomes are of greatest concern for stakeholders and the public?

- What are some of the possible climate change impacts on health systems related to each health hazard (e.g. health facilities, health workforce, etc.)?

- Did recent extreme weather and climate events raise concerns about specific health risks facing individuals in your community or region?

- Were recent assessments conducted in the region in other sectors that highlighted issues affecting health?

- Are neighbouring health jurisdictions also conducting a health vulnerability and adaptation assessment that you might learn from?

Step 1b: Identify project team

Once the health outcomes to be considered are identified, a project team with relevant expertise can be created and an assessment work plan developed. Use the Project Team template to list project team members and other relevant information such as their respective areas of responsibility. This would likely include health officials currently managing the impacts of the identified priority health hazards from Step 1a, along with officials from other sectors whose activities can affect the health hazard. It is also useful to include information on areas of expertise for the identified officials and/or whom they represent (individuals or organizations) and their roles in the assessment.

When identifying potential project team members include the following stakeholders and considerations:

- Officials from local authorities whose activities can affect the burden and pattern of climate-sensitive health outcomes

- Representative healthcare providers who would diagnose and treat any identified cases

- Core members of the project team who stay for the entire project

- Project team members that are representative of the local community in terms of both cultural background and gender

- Project team members that are familiar with the health concerns of segments of the population who are unlikely to be represented on the project team (e.g. the elderly or very young)

- Indigenous persons and holders of traditional and local knowledge should be involved in the project (if possible as project team members) from an early stage

- Individuals that are working on issues relevant to the mandate of the assessment in other departments or organizations (e.g. experts in disease transmission, experts on sources of ground-level ozone)

- Communication experts to discuss how to present the results of the assessment to the public in ways that empower appropriate behavioural adaptation actions

- Ensuring a high degree of stakeholder inclusivity while having a small enough team to direct the study most effectively

Consider adding to the team additional resource persons with targeted expertise on specific topics, for example, those with knowledge on the operations of health systems. Th is table provides suggestions on which groups to consider consulting for each component of the health system as outlined in the WHO Operational Framework for Climate Resilient Health Systems.Footnote 6 See Step 4 for more information on health systems and climate-resilience.

| Health system building block | Stakeholder groups |

|---|---|

| Service Delivery |

|

| Financing |

|

| Leadership and governance |

|

| Health workforce |

|

| Health information systems |

|

| Essential medical products and technologies ( including infrastructure) |

|

Step 1c: Develop a vulnerability and adaptation assessment work plan

The work plan needs to consider the extent to which steps in the vulnerability and adaptation assessment are necessary to achieve the desired results. Time and financial resources may call for a delay in the implementation or removal of a particular step; this should be noted in the work plan. For example, the examination of potential health benefits and co-harms of adaptation and mitigation options implemented in other sectors might be omitted or could be undertaken when the next assessment is carried out. Reasons for not undertaking a certain step should be included in the final report to inform the framing and scoping of subsequent assessments.

The work plan should specify the management plan, key responsibilities, activities, timeline, major stakeholders and resources needed for the assessment. In this stage it is also beneficial to take stock of any activities that have been or could be conducted prior to the assessment that may benefit the assessment process. For instance, the assessment process could benefit greatly from the prior completion of a health equity assessment, if time and resources allow. A health equity assessment will foster a better understanding of the possible inequities of the impacts of climate change, existing policies and programs, and potential adaptation options on different populations groups. For more information on health equity assessments, as well as a toolkit for completing them, refer to the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-term Care’s Health Equity Impact Assessment tool.Footnote 7

Use the work plan template to develop your assessment work plan.

Step 1d: Develop a communication plan

Developing a communication plan early in the process is important to ensure that the assessment is structured from the beginning to communicate identified risks effectively to those who will manage the risks and those who could be affected. The plan should specify the primary assessment outputs (e.g. technical report), to whom it will be communicated, mechanisms for sharing the results (e.g. webinars, workshops), and if outreach materials will be developed to communicate results (e.g. factsheets, slide show presentations, posters). Some things to consider in your communications plan are how you will reach populations of concern, including marginalized populations and hard-to-reach audiences (e.g. remote communities, homeless populations, minority linguistic communities, Indigenous Populations etc.). Post-assessment engagement efforts should be constructed in a manner that they reach a wide audience but also key stakeholders (e.g. healthcare providers and community partners). This may mean adopting a variety of outreach strategies (e.g. written reports, short videos that can be shared on social media and community consultations) and partnering with community groups that have developed relationships with populations of concern. Refer to the ‘Communication Plan’ template to document relevant information.

Assessment templates

The following templates are available to help complete Step 1 of the Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment:

1a) Priority health hazards

1b) Project team

1c) Work plan

1d) Communication plan

Step 1a: Priority health hazards template

Use this template to compile preliminary information on climate change-related health hazards in order to identify which ones should be the focus for the assessment. The template lists examples of health hazards and associated health outcomes, populations of concern and health system impacts. You may have more or different indicators to include. Health hazards with more serious health outcomes, health system impacts, and impacts that are felt by populations of concern are higher priority for inclusion on the assessment. When working to identify priority hazards, keep in mind that the impacts of climate change may vary in severity between population groups. Many factors may increase vulnerability to health impacts. For example, socio-cultural and biological factors (e.g. sex, gender, diet, age, occupation, livelihoods, reliance on the land, etc.) contribute to how vulnerable a person or group is to a specific hazard; be cognisant of this and any knowledge gaps that may exist in your area on populations of concern when completing this and other assessment steps. Information such as sex-desegregated health data and previously completed health equity assessments are valuable in helping to fill-in these knowledge gaps.

Use this template to document information related to each health hazard and knowledge gaps of interest to help in prioritization. When compiling this information, pose the following questions to help in the analysis:

- What are the priority climate-sensitive health outcomes of concern for each climate change-related health hazard, including both mental and physical health outcomes?

- What socio-cultural or biological factors (e.g. sex, gender, diet, age, occupation, livelihoods, reliance on the land? etc.) could contribute to making some groups more vulnerable than others?

- What are some of the differential impacts of climate change on populations of concern?

- Which climate-sensitive health outcomes are of greatest concern for stakeholders and the public?

- What are some of the possible climate change impacts on health systems related to each health hazard (e.g. health facilities)?

- Did recent extreme weather and climate events raise concerns about specific health risks facing individuals in your community or region?

- Were recent assessments conducted in the region in other sectors that highlighted issues affecting health?

- Are neighbouring health jurisdictions also conducting a health vulnerability and adaptation assessment that you might learn from?

| Health hazard examples | Health outcome indicator examples | Populations of concern | Health system impacts | Data and informationFootnote * | Knowledge gaps |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme temperature (heat, cold) events |

|

Example for consideration: elderly populations may be at higher risk to extreme temperatures due to poor thermoregulation. | E.g. potential for rolling blackouts at healthcare facilities during heat waves | - | - |

| Other extreme weather events (e.g. storms, floods, drought) |

|

Example for consideration: people who are under-housed and/or underinsured may be at greater risk to extreme weather impacts and subsequent morbidity and mortality. | E.g. surge capacity at healthcare and mental health care facilities during and after extreme weather events and/or damage to health care facilities | - | - |

| Air quality (aeroallergens, air pollution – ground-level ozone, particulate matter) |

|

Example for consideration: people with pre-existing physical health issues, like asthma, may be at greater risk for respiratory outcomes. | E.g. are health facilities adequately safeguarded from wildfire smoke | - | - |

| Food and water security (including access to traditional foods) |

|

Example for consideration: Indigenous community members who may not have adequate access to safe traditional foods | E.g. are psychosocial supports in place for those reliant on predictable weather and climate conditions, such as farmers, foresters, fishers, etc. | - | - |

| Food- and water-borne illnesses |

|

Example for consideration: Minority linguistic communities may not have access to warnings about food and water-borne outbreaks. Pregnant women and children are at greater risk of food-and water-borne disease outcomes. | E.g. surge capacity at healthcare facilities | - | - |

| Vector-borne diseases (Lyme disease, West Nile Virus) |

|

Example for consideration: People who work outdoors or people who are homeless may be at greater risk for exposure. | E.g. access to appropriate diagnostic and treatment options in your region | - | - |

| Stratospheric ozone depletion |

|

Example for consideration: People who work outdoors | E.g. access to appropriate diagnostic and treatment options in your region | - | - |

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

|||||

Step 1b: Project team template

Use this template to list project team members and other relevant information such as their area of responsibility (e.g. health departments managing the health outcome of interest, other sectors whose activities can affect the health outcome), expertise and/or whom they represent (individuals or organizations) and roles in the assessment.

When identifying potential project team members, include the following stakeholders, member types, and considerations:

- Representatives of healthcare providers who would diagnose and treat any identified cases

- Core members of the project team who stay for the entire project

- Ensure a high degree of stakeholder inclusivity while having a small enough team to direct the study most effectively

- Individuals that are working on issues relevant to the mandate of the assessment in other departments or organizations (e.g. experts in disease transmission, experts on sources of ground-level ozone)

- Communication experts to discuss how to present the results to the public in ways that empower appropriate behavioral changes

- Additional resource persons with targeted expertise on specific topics, such as health systems operations

- Indigenous and local knowledge holders

- Project team members that are representative of the local community in terms of both cultural background and gender

- Project team members that are familiar with the health concerns of segments of the population who are unlikely to be represented on the project team (e.g. the elderly or very young)

This work plan should specify the management plan, key responsibilities, activities, timeline and resources needed for the assessment. Use this template to document key milestones or deliverables, deadlines, resources, major stakeholders and key contacts for undertaking the assessment steps. Adapt the work plan template to suite the specific information needs of the assessment.

| Project team member | Contact information | Area of expertise | Roles and responsibilities (e.g. write report, conduct literature review, conduct statistical analysis, provide perspectives on health outcomes of populations of concern, organize meetings and stakeholder workshops etc.) |

|---|---|---|---|

| - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - |

| - | - | - | - |

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

|||

Use this template to specify the primary assessment output (e.g. technical report), to whom it will be communicated, mechanisms for sharing the results (e.g. webinars, workshops), and if outreach materials (e.g. factsheets, slide show presentations, posters) will be developed to communicate results.

| Assessment step | Milestone or deliverable | Deadline | Resources | Major stakeholders | Lead or key contact |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

|||||

Step 1d: Communication plan template

| Assessment milestone or event | Output / outcome | Target audience (e.g. decision-makers, public, populations of concern) |

Communication mechanism (e.g. webinar, outreach materials) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

- | - | - |

|

- | - | - |

|

- | - | - |

|

- | - | - |

|

- | - | - |

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

|||

Step 2: Describe current risks including vulnerabilities and capacities

Step 2: Overview

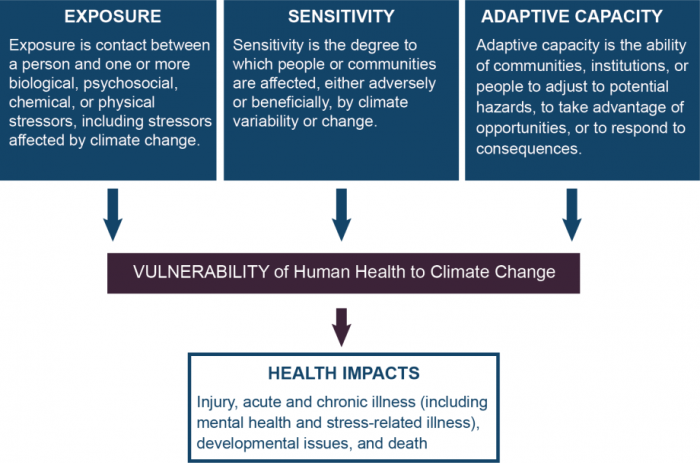

This step is undertaken to describe current climate-related health risks. Describing current climate related health risks involves understanding the past and current climate, and measuring individual and community level vulnerabilities. Vulnerability is determined by measuring the exposure of individuals to the climate-related hazard, their sensitivities, as well as capacity of individuals, communities, and health systems to cope with exposure risks.

Figure 2 - Text Equivalent

This image defines the determinants of vulnerability to health impacts associated with climate change, including exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity.

The image is three rows of text boxes. The first row contains three boxes each with a definition. The first box on the left includes the definition for exposure and the text reads “Exposure is contact between a person and one or more biological, psychosocial, chemical, or physical stressors, including stressors affected by climate change. The second box in the middle includes the definition for sensitivity and the text reads “Sensitivity is the degree to which people or communities are affected, either adversely or beneficially, by climate variability or change. The third box on the right includes the definition for adaptive capacity and the text reads “Adaptive capacity is the ability of communities, institutions, or people to adjust to potential hazards, to take advantage of opportunities, or to respond to consequences”. There are arrows pointing downwards from each box to a textbox in the middle row, with text that reads “Vulnerability of Human Health to Climate Change”, signifying how exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity of an individual/ population can lead to vulnerability of human health to climate change. There is another arrow pointing down from this box to a textbox in the bottom row, with text that reads “Health impacts: Injury, acute, and chronic illness (including mental health and stress-related illness), developmental issues, and death”.

This information provides the context for understanding where modifications to current programs could help protect health as the climate continues to change. The knowledge gained by completing this step will help inform an assessment of health system resilience to be completed in Step 4.

Step 2a: Review qualitative and quantitative information

The datasets, departmental documents, peer-reviewed publications, and internet sources identified during step 1 should be reviewed for relevant information on the priority health hazards, risks and vulnerabilities. Where necessary, further research should be conducted. Gaps in knowledge can be filled, to some extent, by interviewing subject matter experts to describe vulnerabilities and by consulting populations of concern (e.g. through focus groups). Keep track of the information collected in order to quickly reference and analyze the data and to inform the assessment report.

Step 2b: Estimate current relationships between weather patterns and climate- sensitive health outcomes

Determine the associations (if any) between the exposures and the incidence, seasonality, and geographic range of the climate-sensitive health outcomes under consideration.

Graphing the data may prove useful for identifying patterns, particularly with limited time series. It is important to consider factors that could influence any observed trends in health outcomes such as changes in disease control programs and changes in land use. There will be more confidence in analyses conducted using longer and larger health data sets.

When sufficient data are not available, estimates of the strength of associations can be gathered from the published literature or from interviews with subject matter experts. This information can be used to describe exposure-response relationships. Survey questionnaires may be useful for obtaining useful information. Refer to the ‘Estimating Current Relationships’ template to help document relevant information.

Step 2c: Describe historical trends in the climate-related hazards of interest

Collect data and maps on recent weather and climatic trends for priority hazards of interest. Data can be obtained from provincial/territorial agencies, Natural Resources Canada (the atlas of Canada) , Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Canadian Centre for Climate Services , and Climate Data Canada , among other places.

Document how the geographic range, intensity, and duration of particular weather events important to health outcomes have changed over recent decades. Consulting a meteorologist or climatologist can be helpful to ensure data are interpreted appropriately.

Step 2d: Characterize the current vulnerability of individuals and communities

The extent to which a particular group is impacted by a specific health hazard reflects the balance between factors that increase sensitivity and the adaptive capacity to reduce exposures.

Sensitivity is an expression of the increased responsiveness of an individual or community to an exposure, generally for biological reasons (e.g. age or the presence of pre-existing medical conditions), social factors (e.g. marginalized due to race, gender, socioeconomics) and geographic factors (e.g. living on flood plains or in coastal communities).

Health Systems may be susceptible to exposure due to: poor infrastructure, geographic location (e.g. located in floodplains); and/or being under-resourced (e.g. understaffed or underfinanced).

Adaptive capacity refers to the ability of an individual or community to reduce the health effects of climate change including efforts to plan for, respond to, and recover from exposures to climate change-related hazards.

Use vulnerability indicators for each climate hazard and pose questions to obtain indicator data. When collecting data, consider those individuals and communities that are of most concern. Refer to the ‘Vulnerability Indicators’templatefor examples and to record relevant information.

Step 2e: Describe and assess the effectiveness of policies and programs to manage current vulnerabilities and health burdens

Generate a list of all existing policies and programs (at all governance levels (i.e. community/neighbourhood, municipal, county/regional, provincial/territorial and federal) that affect the climate-sensitive health outcomes considered in the assessment. Using evaluations or expert judgement determine how well policies and programs are protecting individuals and communities against climate-related hazards. Consider the effectiveness of current programs/systems in reducing morbidity and mortality (particularly for populations of concern), the quality of program management and delivery, (e.g. infectious disease monitoring and surveillance) and whether existing measures are sufficient for reducing risks. If there are planned changes to any of these policies or programs it may be worthwhile to evaluate them in both their current and future form. Refer to the ‘Effectiveness of Policies and Programs’template to help document relevant information.

Assessment templates

The following templates are available to help complete Step 2 of the Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment:

2b) Estimating current relationships

2d) Vulnerability indicators

2e) Effectiveness of policies and programs

Step 2b: Estimating current relationships between weather patterns and climate-sensitive health outcomes template

Determine the associations (if any) between the exposures and the incidence, seasonality, and geographic range of the climate-sensitive health outcomes under consideration. The estimating current relationships template includes guiding questions and examples of key relationships that could be examined. In the last column of the template, indicate if the information is available and accessible. If it is not readily available or accessible, indicate how the data could be obtained (e.g. conduct a literature search, conduct interviews with subject matter experts, conduct focus groups with populations of concern and access Indigenous and local knowledge by partnering with Indigenous Peoples and community members). Experts can provide estimates of the impacts of extreme weather, such as the impact of extreme heat events on excess mortality or of heavy precipitation events on episodes of gastrointestinal diseases, which can be used to describe exposure-response relationships. If interviews with experts will be conducted, identify key respondents who have carried out other assessments or studies. Create survey questionnaires and keep track of the information collected in order to quickly reference and analyze the data. Where relevant indicate if sex-disaggregated data is available. If it is not, consider how it may be obtained.

| Examples of health hazards | Examples of guiding questions | Indicators of duration, intensity, frequency, seasonality and geographic range for hazard of interest |

Indicators of mortality or morbidity | Is this information available / accessible? If so record this information. If not, how can it be obtained? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Extreme temperature (heat and cold events) |

|

|

|

- |

Air quality (aeroallergens, air pollution from ground-level ozone, particulate matter and/or wildfire smoke) |

|

|

|

- |

Other extreme weather events (e.g. storms, floods, drought) |

- | - | - | - |

Food and water security (including access to traditional foods) |

- | - | - | - |

Food- and water-borne illnesses |

- | - | - | - |

Vector-borne diseases (Lyme disease, West Nile Virus) |

- | - | - | - |

Stratospheric ozone depletion |

- | - | - | - |

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

||||

Step 2d: Vulnerability indicators template

Use this template to document information on the sensitivity and adaptive capacity of individuals and communities to climate-related health hazards. Many indicators are relevant for all climate-related health hazards (i.e. they provide useful information about vulnerability for many or all hazards), while others are specific to one or a few. Examples of vulnerability indicators are provided in the template to help guide data collection. Data from these indicators will also be useful for monitoring adaptation success. See Step 5b:‘Monitoring Indicators’template.

| Health hazard examples | Vulnerability category | Examples of vulnerability indicators | Data source | Vulnerability ranking (Low-Medium-High) | Explanation for vulnerability ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extreme temperature (heat, cold) events | Exposure |

|

- | - | - |

| Sensitivity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Adaptive capacity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Other extreme weather events (e.g. storms, floods, drought) | Exposure |

|

- | - | - |

| Sensitivity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Adaptive capacity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Air quality (aero-allergens, air pollution from ozone, particulate matter and/or wildfire smoke) | Exposure |

|

- | - | - |

| Sensitivity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Adaptive capacity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Food and water security (including access to traditional foods) | Exposure |

|

- | - | - |

| Sensitivity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Adaptive c apacity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Food- and water-borne illnesses | Exposure |

|

- | - | - |

| Sensitivity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Adaptive capacity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Vector-borne diseases (Lyme disease, West Nile Virus) | Exposure |

|

- | - | - |

| Sensitivity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Adaptive capacity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Stratospheric ozone depletion (health impacts may include: cases of sunburns, skin cancers, cataracts and eye damage, etc.) | Exposure |

|

- | - | - |

| Sensitivity |

|

- | - | - | |

| Adaptive capacity |

|

- | - | - | |

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

|||||

Step 2e: Effectiveness of policies and programs template

Use Table 8 in this template to generate a list of all existing policies and programs that affect the climate-sensitive health outcomes considered in the assessment. Use Table 9 and existing evaluations and/or expert judgement to evaluate the effectiveness of key policies and programs for reducing the relevant climate-related health risks. Two main categories of investigation process and outcome - should be considered when conducting an evaluation. If there are planned changes to any of these policies or programs it may be worthwhile to evaluate them in both their current and future form.

Process and Outcome EvaluationsFootnote 10

Process evaluation determines if the policy or program has been carried out as planned and whether each component of the policy or program has been operating effectively. It involves gathering data during implementation to assess program-specific issues of relevance and performance as well as design and delivery. The evaluation should address pre-identified questions using a set of indicators. Data sources could include: financial reporting information, interviews, meeting summaries, website usage statistics and other inquiries received and table-top exercises.

Outcome evaluation focusses on the impact of the policy or program based upon the policy or program goals and objectives. An evaluation should be focussed on issues of greatest concern to partners and stakeholders, while being as simple and cost-effective as possible. It is most appropriate for well-developed policies or programs that have made progress towards achieving intermediate objectives and ultimate goals. This type of evaluation should focus on policy or program effectiveness by measuring changes in morbidity and mortality and the impact of the public health interventions on awareness, knowledge, understanding and behavioural change. Outcome evaluations may need more resources because they require several years of observation, the establishment of baseline data, access to hospitalization and annual mortality data, and the expertise of an epidemiologist to conduct the analysis. A detailed analysis of health outcomes based on only a few years of implementation of the program or policy will likely convey a limited understanding of program impact and effectiveness.

| Examples of health hazards | Policies or programs | Evaluation data sources |

|---|---|---|

General |

1. |

- |

2. |

- | |

3. |

- | |

4. |

- | |

5. |

- | |

Extreme temperature (heat, cold) events |

1. |

- |

2. |

- | |

3. |

- | |

4. |

- | |

5. |

- | |

Other extreme weather events (e.g. storms, floods, drought) |

1. |

- |

2. |

- | |

3. |

- | |

4. |

- | |

5. |

- | |

Air quality (aero-allergens, air pollution from ground-level ozone, particulate matter and/or wildfire smoke) |

1. |

- |

2. |

- | |

3. |

- | |

4. |

- | |

5. |

- | |

Food and water security (including access to traditional foods) |

1. |

- |

2. |

- | |

3. |

- | |

4. |

- | |

5. |

- | |

Food- and water-borne illnesses |

1. |

- |

2. |

- | |

3. |

- | |

4. |

- | |

5. |

- | |

Vector-borne diseases (e.g. Lyme disease, West Nile Virus) |

1. |

- |

2. |

- | |

3. |

- | |

4. |

- | |

5. |

- | |

Stratospheric ozone depletion (health impacts may include: cases of sunburns, skin cancers, cataracts and eye damage, etc.) |

1. |

- |

2. |

- | |

3. |

- | |

4. |

- | |

5. |

- | |

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

||

| Evaluation type | Example evaluation questions | Indicator examples | Evaluation data | Unintended consequencesFootnote † | Evaluation resultFootnote * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Process |

Operational Costs | ||||

|

|

- | - | - | |

| Protocols / processes | |||||

|

|

- | - | - | |

| Stakeholder engagement | |||||

|

|

- | - | - | |

| Communication | |||||

|

|

- | - | - | |

Outcome |

|

|

- | - | - |

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

|||||

|

|||||

Policy or program name:

Date template completed:

Completed by:

Step 3: Project future health risks

Step 3: Overview

This step requires consideration of how the current magnitude and pattern of climate-sensitive health burdens could change in a changing climate. For this step, build on information that was collected in Step 2b (refer to the ‘Estimating Current Relationships’ template).

This step requires input from experts as well as access to both significant quantities of data and sources of relevant literature. This should be noted when planning how to best approach this step.

Step 3a: Review qualitative and quantitative information

Explore datasets, department documents, peer-reviewed publications, and internet sources to identify relevant information. Collect information to answer questions about projected health burdens from climate change such as: how could climate change affect air pollution or the frequency, intensity, and duration of future extreme heat events? When information is unavailable, seek insight from experts.

Step 3b: Describe how current risks could change under different weather and development patterns

Determine the time frame for projecting future health risks. Confidence in climate projections over the next few decades (up to 2040’s) is greatest. To project future health risks, a common approach is to multiply current exposure-response relationships by the projected change in the relevant weather variable(s) over the time periods of interest. This approach assumes that current vulnerability will remain the same over the coming decade; which is unlikely. Vulnerability is expected to change as socio-economic, demographic, health system and environmental factors change over time (e.g. impacts of extreme heat on an aging population). Consider also how weather affects the evolution of climate-sensitive health risks. Aim to estimate how morbidity and mortality associated with climate hazards identified in the assessment could be altered both by climate change and non-climate factors that affect vulnerability of individuals and communities.

Use the following approaches to obtain relevant information:

- Work with modeling experts to obtain quantitative projections of health risks.

- Host an expert meeting (including experts from or familiar with issues relevant to populations of concern) with the goal of describing several possible different pathways affecting vulnerability based on socio-economic, demographic, health system and environmental changes over the next few decades. Efforts should be made to select experts whose experience is reflective of the community being assessed and of populations of concern.

- Use local and regional climate projections from available sources. Scenarios can be created that combine socio-economic and demographic development pathways with climate change projections to facilitate projections that cover a wider range of possible futures.

- Use a qualitative approach, through expert interviews and facilitated discussions, to estimate health risks in the next few decades.

- Engage with Indigenous and local knowledge holders to explore traditional and local knowledge of climate change risks and impacts.

The projected risks will have several sources of uncertainty. Describe climate uncertainties in the assessment report and the extent to which they could influence projected health risks. Refer to the ‘Project Future Health Risks’ template to document relevant information for this step.

Assessment templates

The following template is available to help complete Step 3 of the Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment:

3b) Project future health risks

Step 3b: Project future health risks template

Use this template to document projections of future climate change risks to health. To project future health risks, a common approach is to multiply current exposure-response relationships by the projected change in the relevant weather variable(s) over the time periods of interest. Keep in mind that vulnerability including key aspects of adaptive capacity will also evolve over time. For each climate health hazard of interest, use the guiding questions in this template to collect and document information. Add to the list of questions to focus inquiries and to obtain relevant information for the assessment. It is important to keep in mind that projected changes in climate may or may not take place in the timeframe or to the scale anticipated. Projected changes should influence adaptive responses in relation to the likelihood in which they will occur and the severity of possible health outcomes. To obtain data, employ literature searches, expert interviews (including experts with knowledge on the vulnerability of populations of concern), workshops, consultations with modelling experts, and other approaches. Document uncertainties and underlying assumptions (e.g. expected demographic changes) and how they could affect projected health risks in the template.

| Health hazard examples | Guiding questions | Time period | Projected changes in hazards | Baseline health risks | Projected changes to health risks | Uncertainties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Extreme temperatures (heat and cold events) |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - | |

Other extreme weather events (e.g. storms, floods, drought) |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - | |

Air quality (aeroallergens, air pollution from ground-level ozone, particulate matter and/or wildfire smoke) |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - | |

Food and water security (including access to traditional foods) |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - | |

Food- and water-borne illness |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - | |

Disease vectors (e.g. vectors for Lyme disease and West Nile Virus) |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - | |

Stratospheric ozone depletion (health impacts may include: cases of sunburns, skin cancers, cataracts and eye damage, etc.) |

|

- | - | - | - | - |

|

- | - | - | - | - | |

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

||||||

Step 4: Identify and prioritize policies and programs to increase climate-resilience of health systems

Step 4: Overview

The purpose of this step is to identify and recommend options to modify current policies and programs and to assess and foster climate-resilience within health systems. When completing this step, as well all others, it is important to adopt a holistic understanding of health and health equity. Both physical and mental health and the many components of the health system responsible for their promotion, attainment and protection should be considered.

This step involves assessing the current resilience of the health system in question (i.e. a local or provincial/territorial health system) and prioritizing options for modifications and adaptations to address both system-wide issues as well as issues specific to priority health concerns. These options for modifications and adaptations should include considerations for short, medium and long-term needs. The resilience of health systems and the issues they face may change over time. This should be considered when completing this step. Some modifications or adaptations will not lead to immediate results, while others may not be feasible in the short or medium term. These modifications or adaptations should still be considered and may be evaluated further as part of follow-up V&A assessments in the future.

Examples of possible modifications include:

- Strengthening physical health, mental health and environmental health services

- Strengthening early warning systems, disaster risk management and integrated disease surveillance programs

- Improving information sharing (including that attained from early warning systems) amongst the various components of the health system

- Mainstreaming climate change into health policy

- Improving infrastructure and built environment initiatives to include climate change and health considerations

- Strengthening connections between climate sensitive components of the health system (e.g. healthcare facilities, local disease surveillance units, and provincial/territorial public health agencies)

This step does not present an exhaustive approach to assessing climate-resilience and should be viewed primarily as a means through which to ensure broad health system considerations are incorporated into your assessment. The completion of a V&A is one component of building a climate-resilient health system and can help inform resilience building actions throughout your organization.

Step 4a: Assess health system climate-resilience

Where previous steps have focused primarily on evaluating vulnerability and enhancing capacity to deal with priority health hazards facing individuals and communities, this step focuses on health system-wide risks.

Climate-resilience refers to the health system’s capacity toFootnote 4:

- Anticipate the impacts of climate change

- Respond to the impacts of climate change

- Cope with the impacts of climate change

- Recover from the impacts of climate change

- Adapt to the complex challenges brought on by climate change

Health systems are made up of a variety of people (patients, healthcare workers, public health representatives, supply-chain workers, etc.), organizations (health ministries, health services organizations, public health organizations, pharmaceutical organizations, health management groups, health research organizations, etc.), and facilities (hospitals, long-term care facilities, clinics, public health units, pharmacies, etc.) that interact to support individual and population-level health. For examples of the components of and actors that operate within or in support of health systems review Table 6 presented in Step 2b.

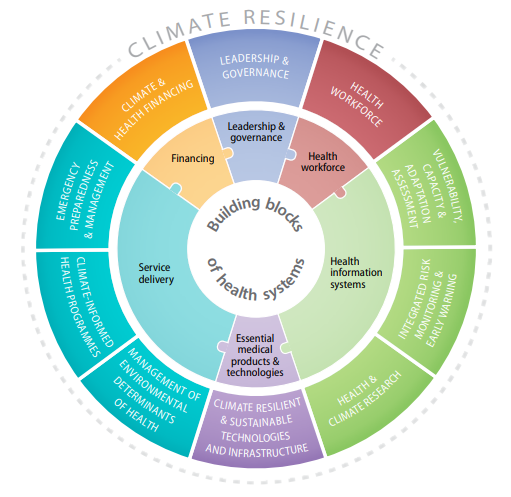

Climate change threatens the safety and integrity of these people, organizations and facilities and has the potential to disrupt the established arrangements that govern the functioning of health systems. This may result in direct and indirect impacts to the health of Canadians. The WHO has developed an operational frameworkFootnote 4, illustrated in Figure 3, to assist health systems with fostering resilience to climate change within their programing and planning. This step incorporates information presented as part of this framework, as well as information tailored to the Canadian context, such as information that may help public health authorities better serve Indigenous PeoplesFootnote 11. Completing this step will help assess how climate change may impact your health system as whole and assist in identifying possible adaptation options to reduce or prevent these impacts.

Figure 3 - Text Equivalent

The framework describes how the building blocks of health systems can be sensitive to, and are relevant for, adapting to the impacts of climate change. It provides examples of actions and indicators that health authorities can use to operationalize the framework in efforts to prepare for climate change. A key component of the framework presented in the report is undertaking vulnerability, capacity and adaptation assessments.

Use Table 11 of Template 4a for local/regional V&As to gauge the preparedness of local and regional health systems and facilities to the impacts of climate change. Use Table 12 of Template 4a for provincial/territorial analysis. The indicators in the templates are examples for consideration and should be tailored to the needs of specific jurisdictions. Additional indicators may be identified by referring to the academic literature or through discussions with experts and community members. Indicators should be reflective of your vision for a climate-resilient health system in your community or region.

Linkages and interconnections among health systems and health partners at local to national levels are an important aspect of resilience and should be included in the analysis.

Step 4b: Review qualitative and quantitative information

Build on step 2e (and the ‘Effectiveness of Policies and Programs’ template) and 4a by collecting information that can be used to identify needed modifications to current policies and programs and new actions to manage climate related health risks to individuals and increase resilience of the health system.

Collect information by:

- Holding focus groups with health authorities, scientists, researchers, practitioners, and stakeholders within and outside the health sector about the adaptations they have implemented and possible new actions that can address health vulnerabilities

- Conducting a literature review (e.g. peer-reviewed publications, gray literature and other internet sources)

Use the ‘Sources for Identifying Adaptation Options’ template (4b) to document relevant information.

Step 4c: Inventory options to improve or implement policies and programs to manage the health risks of climate change

Use the information collected from Step 4b to develop an adaptation inventory listing all options irrespective of resource requirements (economic cost, required staff and time). Include potential adaptations to address risks from specific climate hazards (e.g. air pollution, heat waves, vector-borne diseases, etc.) and also to increase the general resilience of the health system (e.g. climate and health financing, leadership, technology development, health professional training, health facility preparedness, etc.). Consider actions to be taken by the health sector and those to be taken by officials in other sectors (e.g. agriculture, transportation, water, urban planning, energy, etc.). Include diverse perspectives, particularly those of Indigenous Peoples and other populations of concern.

When developing the list, include key stakeholders that need to be engaged. For example, when considering strategies to reduce risks from frequent heavy precipitation events or heat waves, representatives from the provincial/territorial environment agency could be involved. Use the ‘Options Inventory’ template (4c) to document relevant information.

Step 4d: Prioritize options and develop resource needs

Identify which policies and programs are possible to implement now and in the future based on existing resource constraints (technological, human, and financial). Generate a priority list of options from which policymakers can choose. These options should consider the diversity of the population and adaptation needs that address challenges they may face. They should also include opportunities to increase climate-resilience within the health system and equity of the expected outcomes.

Equity should be defined broadly to include considerations for sex, gender, age, socioeconomic status, and culture.

Use one or more prioritization approaches to identify when adaptation options should be implemented. Ensure that criteria used to identify the priorities are explicitly described. The best options reduce negative health outcomes, support health equity, and increase health system climate-resilience. Examples of criteria for prioritising options include:

- What constraints would need to be addressed so the option(s) are more feasible?

- What options are most effective in reducing health risks?

- What options promote health equity?

- Do any options have unintended negative outcomes and could these impact populations of concern? Consider how best to monitor consequences and potential corrective actions to help minimize any unintended negative outcomes.

- Are adequate financial resources available for implementing and sustaining the option?

- Are some options more socially acceptable and culturally appropriate?

Key considerations when prioritizing options are the current morbidity and mortality from the health outcome of concern, projections of future impacts and how well it is managed with current policies and programs. Use the ‘Prioritize Options and Develop Resource Needs’ template (4d) to document relevant information.

Step 4e: Assess possible constraints to implementing options and how to overcome them

For each priority policy and program, list possible constraints or barriers to implementing the options by considering the following:

- Technological, human, and financial resources required for implementation

- Expected time frame for implementation

- Other possible implementation requirements

Differentiate constraints (i.e. which can be overcome) from limits (i.e. no adaptation option is possible or available options are too difficult or expensive to implement). Working with other sectors can help overcome adaptation barriers. Include officials from other sectors in discussions of adaptation constraints to identify non-health sector opportunities to advance adaptations, promote population health and enhance the resilience of the health system. List possible constraints, barriers and limits as well as explore how they might be overcome using the ‘Possible Constraints’ template (4e).

Step 4f: Develop a climate change and health adaptation plan of action

The information generated in previous steps can be synthesized to develop a climate change and health adaptation plan of action that considers shorter and longer time scales and that facilitates coordination and collaboration with other sectors to promote climate-resilience. The adaptation plan of action does not have to be extensive, but should provide sufficient information so that those not involved in its development can understand it and use it to implement the recommended actions. Therefore, differences in the language and jargon used between sectors should be kept in mind and the clearest terms should be used (e.g. disaster mitigation can also be considered climate change adaptation). When developing the plan it is important to include adaptation options that support health equity (including both gender and cultural) and increased health system resilience.

The plan should link with initiatives to address the risks of climate change in other sectors, and include specific goals and the time frame over which key actions will be accomplished. The plan should include the perspectives and needs of populations of concern, such as Indigenous Peoples and others in the broader community. Depending on the context, the plan may include:

- Expected results

- Specific goals to address populations of concern

- Specific goals for increasing health system resilience

- Milestones

- Sequencing of activities

- Clear responsibilities for implementation

- Required human and financial resources

- Costs and benefits of interventions

- Financing options

The plan should promote coordination and synergies with city and provincial/territorial goals that may be captured in other climate change strategies. Including someone with knowledge of such goals on the project team would be an effective approach to making these linkages.

Assessment templates

The following templates are available to help complete Step 4 of the Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment:

- 4a) Assess health system climate- resilience

- Table 11 – Local/ regional health systems

- Table 12 – Provincial/ territorial health systems

- 4b) Sources for identifying adaptation options

- 4c) Options inventory

- 4d) Prioritize options and develop resource needs

- 4e) Possible constraints

Step 4a: Assess health system climate-resilience template

Use this template to help assess the resilience of a local or regional health system. The indicators included here are not exhaustive and may not be suitable to your health system. Additional indicators may be identified by referring to the academic literature or through discussions with experts and community members. The indicators used should be reflective of what a climate-resilient health system would look like for your community. Elements of climate-resilience may be similar across health systems (e.g. access to diagnosis and treatment of climate-sensitive health conditions in your region) while others may be specific to the realities of the communities your health system serves.

It is important to be cognisant of the fact that health systems have linkages beyond their local areas to larger provincial/territorial or neighbouring health systems and therefore considering issues beyond your mandate and geographic area may be a valuable exercise.

| Relevant level of governance | Example indicatorsFootnote a | Example metrics | Example relevant stakeholders/ data and knowledge owners | Potential data sources | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Local |

|

|

|

- | - |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

| - |

|

|

|

- | - |

| - |

|

|

|

- | - |

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

|||||

|

|||||

| Relevant level of governance | Example indicatorsFootnote a | Example metrics | Example relevant stakeholders/ data and knowledge owners | Potential data sources | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Provincial/Territorial |

|

|

|

- | - |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

Or

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

|

|

|

- | - | |

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

|||||

|

|||||

Step 4b: Sources for identifying adaptation options template

Use this template to identify sources of information to help identify potential modifications to policies and programs to reduce current and future health risks from climate change. A range of information sources can be used to identify and collect relevant information (e.g. interviews, literature reviews, workshops, consultations with other health authorities, etc).

| Health hazard examplesFootnote a | Guiding questions | Key experts, literature, data collection opportunities |

|---|---|---|

Extreme temperature (heat, cold) events |

|

- |

Other extreme weather events (e.g. storms, floods, drought) |

||

Air quality (aeroallergens, air pollution from ground-level ozone, particulate matter and/or wildfire smoke) |

||

Food and water security (including access to traditional foods) |

||

Food- and water-borne illnesses |

||

Vector-borne diseases (Lyme disease, West Nile Virus) |

||

Stratospheric ozone depletion and heat intensity (health impacts may include: cases of sunburns, skin cancers, cataracts and eye damage, etc.) |

||

Climate risks to the health system |

||

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

||

|

||

Step 4c: Options inventory template

Use this template to develop a list of adaptation options. Refer to the information collected in Step 4b (and documented in the ‘Sources for Identifying Adaptation Options’template) to develop the inventory of potential adaptation options. Include potential adaptations to address risks from specific climate health hazards and also to reduce climate related risks to the health system (e.g. climate and health financing, leadership, technology development, health professional training, health facility preparedness etc.). Also, include in the template a proposed timeframe for the implementation of the adaptation option and any key stakeholders that may need to be engaged when prioritizing potential options. It is important to consider how these adaptation options may impact health equity and health system resilience.

| Health hazard examples | Potential adaptation options | Timeframe for implementation | Stakeholders to engage |

|---|---|---|---|

Extreme temperature (heat, cold) events |

- | - | - |

Other extreme weather events (e.g. storms, floods, drought) |

- | - | - |

Air quality (aeroallergens, air pollution from ground-level ozone, particulate matter and/or wildfire smoke) |

- | - | - |

Food and water security (including access to traditional foods) |

- | - | - |

Food- and water-borne illnesses |

- | - | - |

Vector-borne diseases (Lyme disease, West Nile Virus) |

- | - | - |

Climate risks to the health system |

- | - | - |

Stratospheric ozone depletion and heat intensity (health impacts may include: cases of sunburns, skin cancers, cataracts and eye damage, etc.) |

- | - | - |

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

|||

Step 4d: Prioritize options and develop resource needs template

Use this template to prioritize the adaptation options. This prioritization should reflect the perspectives of community members (particularly populations of concern) and should be based on feedback from community stakeholders, partners (e.g. Indigenous Peoples) and experts (e.g. health researchers).

| Health hazard examples | Adaptation option | Prioritisation criteria examples | Outcome of prioritisation process (e.g. score / ranking) |

|---|---|---|---|

Extreme temperature (heat, cold) events |

A. |

|

- |

B. |

- | ||

Other extreme weather events (e.g. storms, floods, drought) |

A. |

- | |

B. |

- | ||

Stratospheric ozone depletion (health impacts may include: cases of sunburns, skin cancers, cataracts and eye damage, etc.) |

A. |

- | |

B. |

- | ||

Air quality (aeroallergens, air pollution from ground-level ozone, particulate matter and/or wildfire smoke) |

A. |

- | |

B. |

- | ||

Food and water security (including access to traditional foods) |

A. |

- | |

B. |

- | ||

Food- and water-borne illnesses |

A. |

- | |

B. |

- | ||

Vector-borne diseases (Lyme disease, West Nile Virus) |

A. |

- | |

B. |

- | ||

Climate risks to the health system |

A. |

- | |

B. |

- | ||

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

|||

Step 4e: Possible constraints template

Use this template to list possible constraints or barriers that need to be overcome when implementing the prioritized adaptation options identified in step 4d. Include possible ways to overcome barriers in the last column.

| Health hazard examples | Prioritized adaptation options | Guiding questions | Possible constraints or barriers | Possible ways to overcome barriers |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Extreme temperature (heat, cold) events |

A. |

|

- | - |

B. |

- | - | ||

Other extreme weather events (e.g. storms, floods, drought) |

A. |

- | - | |

B. |

- | - | ||

Stratospheric ozone depletion (health impacts may include: cases of sunburns, skin cancers, cataracts and eye damage, etc.) |

A. |

- | - | |

B. |

- | - | ||

Air quality (aeroallergens, air pollution from ground-level ozone, particulate matter and/or wildfire smoke) |

A. |

- | - | |

B. |

- | - | ||

Food and water security (including access to traditional foods) |

A. |

- | - | |

B. |

- | - | ||

Food- and water-borne illnesses |

A. |

- | - | |

B. |

- | - | ||

Vector-borne diseases (Lyme disease, West Nile Virus) |

A. |

- | - | |

B. |

- | - | ||

Stratospheric ozone depletion (health impacts may include: cases of sunburns, skin cancers, cataracts and eye damage, etc.) |

A. |

- | - | |

B. |

- | - | ||

Climate risks to the health system |

A. |

- | - | |

B. |

- | - | ||

|

Each dash (-) within the table cells represent a fillable field for users to populate |

||||

Step 5: Establish an iterative process for managing and monitoring health risks

Step 5: Overview

Develop an iterative process for managing and monitoring health risks from climate change. This involves:

- Identifying a lead agency to coordinate monitoring and reporting

- Recommending when the climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment should be repeated to identify new risks

- Being aware of changes in the geographic range of health outcomes

- Consulting with partners and stakeholders to help identify and/or inform any possible adjustments to health risk monitoring practices or adaptation projects/programs