Guidelines for Canadian drinking water quality: Radiological parameters

On this page

- Guideline

- Executive summary

- 1.0 Exposure Considerations

- 2.0 Health Considerations

- 3.0 Assessment and Implementation

- 4.0 Analytical and treatment considerations

- 5.0 Treatment considerations

- 6.0 Management Strategies

- 7.0 International Considerations

- 8.0 Rationale for the maximum acceptable concentration

- 9.0 References

- Appendix A: List of abbreviations

- Appendix B: Detailed analysis of international/national recommendations

- Appendix C: Additional scenario specific reference concentrations

- Appendix D: Additional information for screening criteria and radionuclide specific analysis

Guideline

Maximum acceptable concentrations (MACs) have been established for the most significant radionuclides in the uranium- and thorium-decay chains (Table 1) in drinking water. The MACs are derived from a reference level corresponding to a radiation dose of 1 millisievert per year (mSv/year).

Drinking water should initially be screened against a gross alpha radiation level of 0.5 Bq/L (becquerel/litre) and a gross beta level of 1 Bq/L. Individual radionuclide analysis is only necessary when one (or both) of these screening levels is exceeded. If more than one radionuclide in Table 1 is detected, the sum of the ratios of the observed concentration to their corresponding MAC should not exceed 1.

| Natural radionuclides | MAC (Bq/L) |

|---|---|

| Lead-210 | 2 |

| Radium-226 | 5 |

| Radium-228 | 2 |

|

MAC – Maximum acceptable concentration; Bq/L – becquerels per litre |

|

Executive summary

This guideline technical document was prepared in collaboration with the Federal Provincial-Territorial Committee on Drinking Water.

Radionuclides are naturally present in the environment. Everyone is exposed to background radiation from cosmic and terrestrial sources, including food and drinking water. While natural sources are responsible for most of a person's radiation exposure (accounting for over 98%, excluding medical sources), drinking water tends to be a minor component. These guidelines are applicable to radionuclides present in existing or new water systems under routine operational conditions. These guidelines do not apply in the event of a nuclear accident, which is covered under provincial emergency plans.

This guideline technical document draws upon international assessments of the human health risks of radionuclides in drinking water and considers new studies and approaches, including dosimetric information released by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) in 2007. MACs are established for the three natural radionuclides (Pb-210 [lead-210], Ra-226 [radium-226] and Ra-228 [radium-228]) that are considered to be the most significant contributors to radiation dose received from ingesting Canadian drinking water. The MACs were derived using internationally accepted equations and principles. They are calculated using a reference dose level of 1 millisievert (mSv) for one year's consumption of drinking water, assuming a consumption rate of 1.53 L/day.

Screening criteria are established at a dose level of 0.3 mSv for adults. This dose will be relatively higher for infants (< 1 year old) and it is recommended that an alternative source of water (such as bottled water) be used for the preparation of infant formula if the screening criteria is exceeded. The water is acceptable for children (over 1 year old) and adults to consume and use.

There is little or no evidence of elevated concentrations of radionuclides other than Ra-226, Ra-228, and Pb-210 in Canadian drinking water sources. However, for reference purposes, Appendix C lists concentrations derived from the reference level of 1 mSv/y, for two additional natural radionuclides (polonium-210 and radon (radon-222)) and four artificial radionuclides (tritium, strontium-90, iodine-131, and cesium-137). These are rarely seen in Canadian drinking water sources but are present at low levels in the Canadian environment.

Exposure

Natural radionuclides are present at low concentrations in all rocks and soils. When groundwater has been in contact with rock over hundreds or thousands of years, radionuclide concentrations may build up in the water. Concentrations can be elevated in groundwater; these are highly variable and are determined by the composition of the underlying bedrock as well as the physical and chemical conditions in the aquifer. Natural radionuclides have also been known to occur in shallow wells, although this is rare.

Increased levels of natural radionuclides in surface waters may be linked to industrial processes such as uranium mining and milling, or to environmental processes such as cosmogenic fallout and radon progeny washed out of the atmosphere. Sources of artificial radionuclides include fallout from above-ground nuclear weapons testing (before 1963) and emissions from nuclear reactors and other activities (such as research, and diagnostic and therapeutic medicine). In Canada, levels of artificial radionuclides in the environment are very low.

Radionuclide levels in excess of the MACs are likely to occur only in a limited number of drinking water systems in Canada.

Health effects and risk

The main health risk associated with any exposure to low levels of radiation is an increase in the incidence of cancer among individuals in an exposed population. When energy from ionizing radiation is deposited in a cell, it can damage the DNA. If the DNA is not repaired correctly, cells can develop abnormally, potentially leading to cancer.

Reviews of epidemiological studies have not found conclusive evidence of any health effects from drinking water containing natural levels of radioactivity (Guseva Canu et al, 2011; Alimam and Auvinen, 2025). For the purposes of radiation protection, we assume that the risk of cancer increases linearly with exposure above the dose from background levels. However, as naturally occurring radionuclides are part of background levels, setting management criteria strictly by extrapolating from the linear model is inconsistent with international best practice. Therefore, the screening criteria and MACs identified in this guideline document are not directly associated with a quantified health risk; rather, they are set to align with international recommendations (ICRP, 2007) and the requirements outlined in the Radiation Protection and Safety of Radiation Sources: International Basic Safety Standards (IAEA, 2014).

Analytical and treatment considerations

The guideline development process considers the ability to measure (quantify) and remove (treat) a contaminant from drinking water supplies. Methods are available for screening water supplies for radioactivity, and individual radionuclides can be reliably measured to levels below the MACs.

At the municipal level, most radionuclides can be effectively removed from water supplies using treatment technologies such as reverse osmosis, ion exchange and lime softening. It should be noted that residuals from treatment may be radioactive at a low-level, creating special considerations for waste disposal that water systems should take this into account when choosing a treatment option.

At the residential scale, multiple point-of-entry and point-of-use treatment technologies are available, which have a similar removal efficacy to municipal-scale technologies. At the residential scale, devices are generally not expected to contain enough radioactivity to warrant special precautions by homeowners.

Distribution systems

Radiological elements can accumulate within distribution system sinks, or in the bulk water itself, by a variety of physical, chemical, and biological mechanisms. These mechanisms are dependent on the specific contaminant, water quality conditions, mineralogy, composition, and properties of the sinks, and hydraulic conditions. Contaminants can accumulate within or on top of scale deposits, corrosion products and in distribution systems. Many of the mechanisms that influence contaminant accumulation are reversible under certain conditions, which can lead to contaminant release. Scales formed in distribution system pipes from precipitates (deposits) involving iron, manganese and aluminum can subsequently release contaminants such radionuclides, arsenic and other trace metals into the distributed water.

Radionuclides (such as Pb-210, Ra-226 and Ra-228) have been shown to accumulate in distribution system piping, depending on the source water characteristics, distribution system materials, and the presence of co-occurring metals. When radionuclides are present in the source water, drinking water treatment systems should determine if they need to be included in their monitoring and distribution system management plans, to prevent their accumulation on corrosion scales and their subsequent release into the distributed water. It is recommended that water utilities develop a distribution system management plan to minimize the accumulation and release of radionuclides and co-occurring contaminants in the system. This typically involves reducing concentrations entering the distribution system; and implementing best practices to maintain stable chemical and biological water quality throughout the system and reduce physical and hydraulic disturbances which can release corrosion products and co-occurring contaminants (such as radionuclides).

Application of the guideline

Note: Specific guidance related to the implementation of drinking water guidelines should be obtained from the appropriate drinking water authority in the affected jurisdiction.

MACs have been established for three natural radionuclides (Pb-210, Ra-226 and Ra-228), which represent the most significant radionuclides in Canadian drinking water supplies.

The MACs apply to water that is being consumed, so sampling and monitoring should be reflective of the water that comes out of the tap. For existing systems, if water is treated before consumption, it should be monitored after treatment because treatment can reduce the activity concentrations of many radionuclides. In general, the concentration of the radionuclides in Table 1 is not expected to change in the distribution system, so it is appropriate to measure the water at the treatment facility after treatment or at storage reservoirs prior to distribution. For supplies of drinking water that are not treated, such as some small water supplies, the radionuclides can be measured at the source or the point of collection. Ideally, some measurements should be made at the point of consumption, that is, at the tap or communal point of collection. However, this may not be practicable for large distribution systems.

For a new drinking water supply, measurements of radionuclides should be made using the source water, as part of characterizing it and determining its suitability for drinking. The existing treatment technologies and strategies in place to address other contaminants should also be taken into account. This characterization should be carried out along with assessing microbiological and chemical risks as part of developing water safety plans.

Screening criteria of 0.5 Bq/L for gross alpha activity and 1 Bq/L for gross beta activity are recommended for characterizing the water source. These values are conservative, as they represent one-third of the reference dose levels used in determining the MACs. If either of the screening criteria are exceeded, measurements of the radionuclides in Table 1 should be made and compared to the MACs. Exceedances of the MACs should be investigated with additional monitoring, and a risk assessment should be conducted to determine the most appropriate way to handle the exceedance.

Drinking water supplies that exceed the screening criteria or MAC values will rarely pose a health risk, especially in the short term. However, when preparing infant formula, if there is an exceedance of either screening criterion for gross alpha or gross beta, it is recommended that an alternative source of water (such as bottled water) be used. This is a precautionary measure, because of the time it may take to characterize a water supply. The water is acceptable for children (older than 1 year) and adults to consume and use.

Generally, discontinuing use of the water—while characterizing the radionuclide content and, if necessary, implementing remedial actions—is only necessary if radionuclide levels are very high. Decisions to discontinue the use of the water for drinking purposes should not be made without first ensuring that a better option is available, and should consider factors such as the extent to which the reference level is exceeded and the costs of remediation.

1.0 Exposure Considerations

1.1 Radionuclides of interest, sources and environmental behaviour

1.1.1 Radionuclides of interest

Radioactivity is present everywhere in the environment and has been since the earth was formed. Naturally occurring radionuclides are predominantly primordial (having half-lives comparable to the age of the earth) isotopes of potassium, uranium and thorium, and their decay products, or they can be produced from the interaction of cosmic rays with the earth's atmosphere. Artificial radionuclides are produced for medical and industrial purposes or as by-products of nuclear energy production and historical nuclear weapons testing.

Radionuclides that occur in drinking water due to a nuclear emergency are not covered in these guidelines. Please see "Generic Criteria and Operational Intervention Levels for Nuclear Emergency Planning and Response" (Health Canada, 2018), as well as provincial nuclear emergency plans, for more information and guidance. These guidelines also do not supersede regulations for industry and CNSC licensed activities that may have stricter requirements (Justice Laws, 1997).

In Canada, most radionuclides in drinking water are naturally occurring. They enter the source water via natural processes such as the erosion of radionuclide-bearing minerals in rock and soil. Inputs from human activities—such as mining, nuclear power production or nuclear medicine—tend to be much smaller, because industrial and medical uses of radionuclides are regulated at the source and environmental emissions are optimized to be well below regulatory limits (IAEA, 2016; WHO, 2022). Contributions from past nuclear weapons testing and accidents are nearly negligible (UNEP, 2016).

| Radionuclide | Half-life | Decay mode | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radium-226 | 1600 y | alpha | Uranium decay chain |

| Radium-228 | 5.75 y | beta | Thorium decay chain |

| Radon-222 | 3.82 d | alpha | Uranium decay chain |

| Lead-210 | 22.2 y | beta, gamma | Uranium decay chain |

| Polonium-210 | 138.3 d | alpha | Uranium decay chain |

| Tritium | 12.3 y | beta | Naturally produced due to interactions of cosmic rays with molecules in the air Artificially produced by nuclear reactors |

| Cesium-137 | 30.08 y | beta, gamma | Nuclear reactors, historical nuclear weapons testing |

| Iodine-131 | 8.02 d | beta, gamma | Nuclear reactors, nuclear medicine |

| Strontium-90 | 28.9 y | beta | Nuclear reactors, historical nuclear weapons testing |

|

y – year; d – day |

|||

There is little or no evidence of elevated concentrations of radionuclides other than Ra-226, Ra-228, and Pb-210 in Canadian drinking water sources. However, for reference purposes, Appendix C lists reference concentrations, derived from the reference level of 1 mSv/y, for two additional natural radionuclides (polonium-210 and radon (radon-222)), and four artificial radionuclides (tritium, strontium-90, iodine-131, and cesium-137). These are provided for health guidance when interpreting monitoring data where, in unique scenarios, there is reason to believe that levels may be significant.

Uranium is only weakly radioactive. From a health perspective, its chemical properties are more significant and so it is treated as a chemical hazard rather than a radioactive one. Information on uranium in drinking water can be found in the Guidelines for Canadian Drinking Water Quality Guideline Technical Document – Uranium(Health Canada, 2019).

1.1.2 Sources and environmental behaviour

The occurrence of natural radionuclides in drinking water is most commonly associated with groundwater. Natural radionuclides are present in all rocks and soils, but their concentrations vary depending on the mineral content. Examples of rocks that tend to contain higher levels of uranium and thorium include crystalline rocks such as granite and quartz-conglomerate metamorphic rocks, and sedimentary rocks such as organic shales, sandstones, carbonates and phosphorites (Cowart and Burnett, 1994). When groundwater has been in contact with rock over hundreds or thousands of years, significant concentrations of radionuclides may leach into the water.

The environmental transport of radionuclides is influenced by radionuclides' physical and chemical properties, as well as the properties of the medium or environment in which they are travelling. A radionuclide's mobility is governed mainly by its non-nuclear properties, and thus isotopes of the same element behave in the same way chemically. Hydro-chemical behaviour like mobility and solubility are dependent on water quality, including alkalinity, pH, redox potential and chemical composition (WHO, 2018). Volatile radionuclides (like radon) will escape from water into the atmosphere, meaning that they are less likely to accumulate in water sources exposed to the air (Otton, 1992; WHO, 2011).

It is difficult to predict whether radionuclides are present (and in what quantities) in a specific geographical location, even when the geology is known. Therefore, it is recommended that each situation be evaluated on a case-by-case basis through characterization of the source water or on the basis of previous data from the area. Only a very small fraction of water sources are expected to have radionuclide concentrations that exceed the guideline values.

1.2 Exposure

1.2.1 Radionuclide dose data from various studies in Canada

The data available on radionuclide concentrations in drinking water in Canada indicate a general trend as depicted in Figure 1. The concentrations of natural radionuclides in most water systems are low and contribute to an annual dose of less than 1 millisievert (mSv). On occasion, groundwater sources or wells may contain natural radionuclides that could result in an annual dose approaching or exceeding 1 mSv. Artificial radionuclides are found in very low concentrations, resulting in a negligible annual dose.

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

Annual doses of radionuclides in drinking water:

- <10 millisievert: Natural radionuclides (limited number of groundwater sources or wells)

- <1 millisievert: Natural radionuclides (most groundwater sources or wells)

- <0.1 millisievert: Natural radionuclides (large community water sources)

- <detection limit or <0.01 millisievert: Artificial radionuclides (primarily surface waters near nuclear facilities).

DL – detection limit; mSv – millisievert

Radioactivity levels from artificial radionuclides measured in waters near nuclear facilities in recent years (before 2022) have consistently been below detection limits, or below 0.01 mSv/y, according to the results of the Independent Environmental Monitoring Program (IEMP) of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC). Specifically, cesium-137 (Cs-137) in waters near 9 nuclear facilities, cobalt-60 in waters near 7 nuclear facilities, americium-241 in waters near 1 nuclear facility, iron-59 in waters near 1 nuclear facility, and iodine-131 (I-131) in waters near 1 nuclear facility, were all below detection limits. Measurements of tritium (H-3) in waters near 10 nuclear facilities all corresponded to doses below 0.01 mSv/y (CNSC, 2023).

Three published studies summarizing the available Canadian data for large community water sources all indicate that doses from Ra-226, Rn-222, lead-210 (Pb-210) and Ra-228 are under 0.1 mSv/y. One reviewed natural radioactivity levels in the public water supply for 24 metropolitan areas and cities (Chen, 2018a). Another summarized the results of a series of analyses characterizing natural radioactivity levels in municipal drinking water supplies, conducted over a 30-year period by Health Canada. Measurements for many of the municipalities were discontinued after a few years as they showed consistently low levels of radioactivity. Three municipalities where circumstances indicated a potential for higher radioactivity levels, had continued measurements: in Regina, due to high concentrations of uranium in the sedimentary bedrock; in Elliot Lake, due to past and present uranium mining operations; and in Port Hope, due to activities associated with waste management and refining operations (Chen, 2018b). A third study presented Ra-228 concentrations in municipal drinking water in Regina, Elliot Lake, and Port Hope in 2012–2016 (Chen et al., 2018c).

Health Canada's Radiation Protection Bureau generates and reviews data characterizing groundwater and wells for special projects and consultations (unpublished). Most of these results indicate that concentrations of natural radionuclides, including Ra-226, Ra-228 and Pb-210, are below levels that would correspond to doses of 1 mSv/y. However, instances have occurred of doses that would approach or exceed 1 mSv/y.

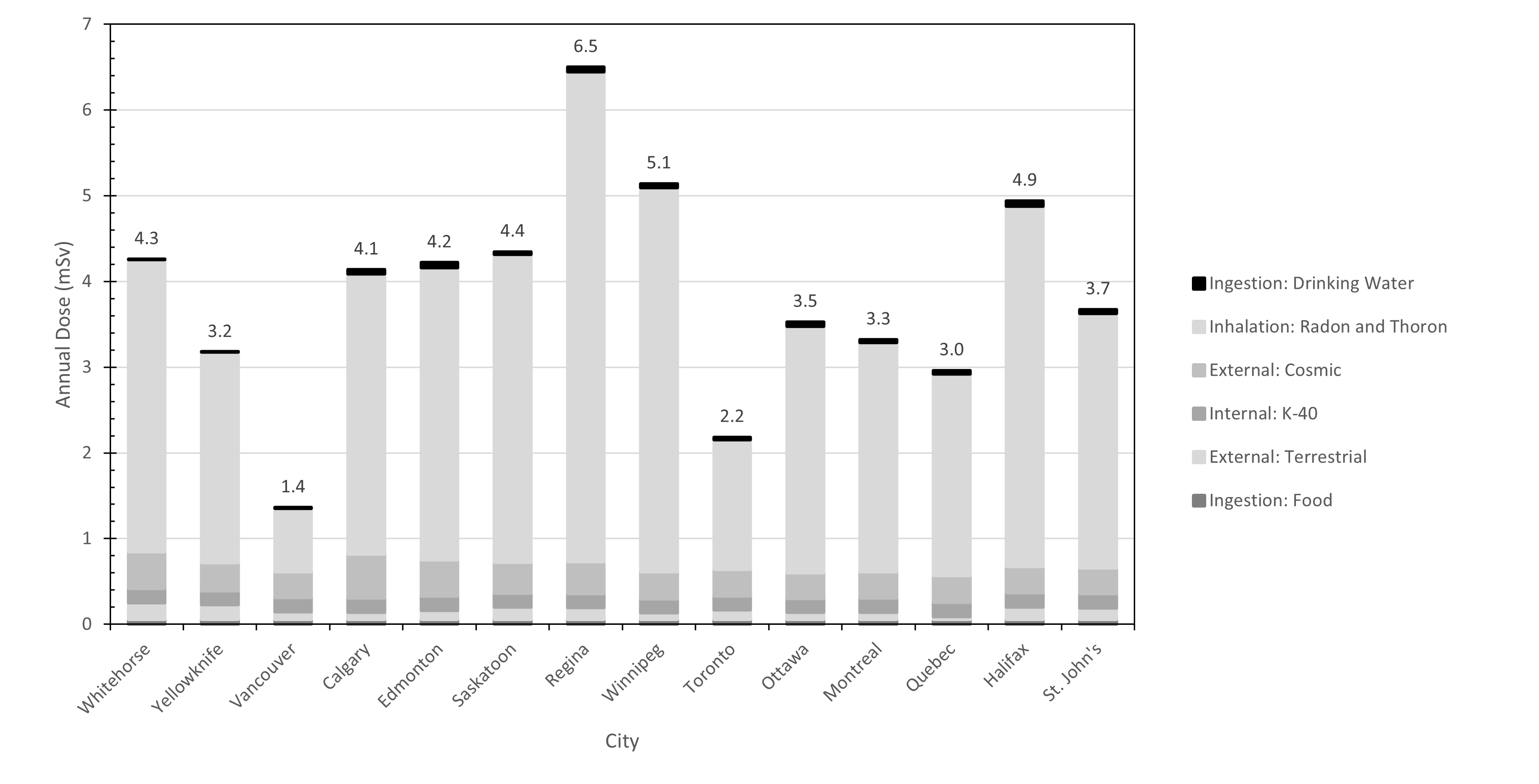

1.2.2 Putting exposures from drinking water into perspective

It is important to put exposure to radiation from drinking water into perspective. As shown in Figure 2, annual doses from natural sources of ionizing radiation vary in different Canadian cities, due to factors such as local geology, latitude and altitude. As mentioned in section 1.2.1, the data consistently show that for most Canadians, typical doses from ingesting drinking water represent a very small percentage of the total exposure from all natural sources. Reviews of epidemiological studies have not found conclusive evidence of any health effects from drinking water containing natural levels of radioactivity (Guseva Canu et al, 2011; Alimam and Auvinen, 2025).

The most important pathway for exposure to most radionuclides in drinking water is ingestion of the water. Radiological effects from dermal and inhalation exposure are considered to negligible since the radionuclides for which MACs have been established are not absorbed by the skin and are non-volatile.

Figure 2 - Text Equivalent

| City | External: Terrestrial (mSv) | External: Cosmic (mSv) | Inhalation: Radon and Thoron (mSv) | Ingestion: Drinking Water (mSv) | Internal: K-40 (mSv) | Ingestion: Food (mSv) | Total (mSv) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whitehorse | 0.196 | 0.428 | 3.413 | 0 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 4.3 |

| Yellowknife | 0.172 | 0.329 | 2.453 | 0 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 3.2 |

| Vancouver | 0.091 | 0.300 | 0.739 | 0.012 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 1.4 |

| Calgary | 0.087 | 0.514 | 3.269 | 0.048 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 4.1 |

| Edmonton | 0.109 | 0.426 | 3.407 | 0.058 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 4.2 |

| Saskatoon | 0.145 | 0.361 | 3.592 | 0.028 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 4.4 |

| Regina | 0.139 | 0.372 | 5.714 | 0.054 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 6.5 |

| Winnipeg | 0.077 | 0.316 | 4.482 | 0.046 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 5.1 |

| Toronto | 0.112 | 0.311 | 1.513 | 0.028 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 2.2 |

| Ottawa | 0.083 | 0.299 | 2.873 | 0.051 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 3.5 |

| Montreal | 0.085 | 0.305 | 2.679 | 0.031 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 3.3 |

| Quebec | 0.037 | 0.309 | 2.357 | 0.038 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 3.0 |

| Halifax | 0.148 | 0.305 | 4.203 | 0.064 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 4.9 |

| St. John's | 0.137 | 0.303 | 2.970 | 0.044 | 0.165 | 0.055 | 3.7 |

|

mSv – millisievert |

|||||||

1.2.3 Radon

The largest contributor to the background radiation dose received by most Canadians from all sources is inhaled radon (Rn-222) and its short-lived decay products (see Figure 2). Radon is a gas that comes from the decay of uranium in rocks and soils. It typically enters a building through cracks and other openings in contact with the ground and can accumulate, sometimes reaching levels where intervention is required. Breathing air that contains high levels of radon can significantly increase lung cancer risk over time, and this is the most important consideration by far when managing radon exposure.

Groundwater can contribute to radon concentrations in indoor air. When groundwater is brought inside for drinking or other purposes, dissolved radon can transfer (outgas) to the air. For surface water sources and municipally treated water sources, natural agitation and exposure to the open air allows radon to escape before the water reaches the distribution system.

There is no MAC for radon in drinking water because Health Canada recommends testing for radon using approved devices for measuring concentrations in air, and mitigating when levels exceed the Canadian radon guideline (Radon guideline - Canada.ca). Measuring the air will capture the contributions from all sources of radon and enable better decisions for management strategies.

Municipal systems that draw from groundwater supplies and do not have sufficient aeration in the distribution system, should check that their radon concentration is below that of the reference values for radon ingestion and mitigate according to treatment options in Section 5.2.3. In most other cases, it is not necessary to measure radon when assessing the quality of water for drinking. More information is provided in Appendix C.

Radon concentrations in air should not be extrapolated from concentrations in water. While there are rules of thumb for estimating the amount of radon that outgases from water in a home, the only way to properly assess the inhalation risk is to test the air. Health Canada recommends that all homes and workplaces test for radon. More information is available on the radon page.

2.0 Health Considerations

2.1 Health effects

Radionuclides emit ionizing radiation, which has enough energy to remove electrons from atoms and molecules. In very simple terms, when an electron shared by atoms forming a molecular bond is dislodged, the bond is broken and the molecule falls apart. This process may occur by a direct "hit" to these atoms or may result indirectly from free radical formation due to the irradiation of adjacent molecules. When ionizing radiation is absorbed in a human cell, it can cause damage to the DNA molecule. The body's natural response mechanisms will often deal with the damage before it becomes a problem. However, in some cases, the damage can lead to abnormal cell growth, or cancer. The primary health objective when managing public exposure to ionizing radiation is to reduce the risk of attributable cancer.

Factors relevant to radiation-induced cancer include, among other things, the pathway of exposure, the physical characteristics and chemical behaviour of the radionuclide and the sensitivity of the exposed organs.

The main evidence linking radiation exposure and cancer comes from epidemiological studies of individuals or groups who have had relatively high exposures, such as:

- atomic bomb survivors at Hiroshima and Nagasaki

- patients who received high radiation doses for diagnostic or therapeutic purposes

- occupationally exposed workers (historical records), including uranium miners and radium dial painters

At lower doses and dose rates, the epidemiological evidence is less clear, in part because everyone is exposed to low levels of radioactivity as part of natural background, and in part because radiation-induced cancer cannot be distinguished from cancers due to other causes (ICRP, 2007). However, mechanistic studies indicate that relatively low doses of radiation can trigger biological responses associated with cancer (UNSCEAR, 2021). For the purposes of radiation protection, it is assumed that low doses of radiation have the potential to lead to cancer or heritable effects, and this assumption forms the basis for risk assessment and management as described in the next section. It is recognized that there is a great deal of uncertainty about the relationship between exposure and health effects at low doses and dose rates.

2.2 Risk

Radiation-induced cancer and heritable mutations are stochastic effects whose probability of occurrence is assumed to increase or decrease as exposure increases or decreases. Radiation protection uses calculations that characterize the prospective risk of these effects as the basis for making decisions about managing exposure. The internationally-accepted risk model for these calculations is linear and has no threshold, meaning that it is possible to calculate a risk for any exposure, no matter how small. In daily life, we face health risks from many different sources.

Sometimes interventions to reduce one risk can lead to unwanted consequences that are more severe than the original concern. It is, therefore, important to find a balance. With this in mind, the ICRP has established the principles of justification and optimization as the basis for its system of protection (ICRP 103). Specifically:

- any decision to alter a radiation exposure situation (increase or decrease) should do more good than harm, considering all radiological and all non-radiological risks and consequences

- the level of exposure should be kept low, with economic, societal, environmental and other factors being taken into account

These principles are used to inform the Canadian and international systems of radiation protection.

The MACs for drinking water in Canada have been established at levels well below any level of importance to human health, so the radiological risk is very small. In most situations, the non-radiological costs and/or consequences of achieving these targets are relatively minor; however, there are exceptions, particularly for small or private water systems. The negative consequences of water restrictions or expensive treatment systems may significantly outweigh the benefits of avoiding a small radiation dose. In these cases, it is important to seek the advice of radiation protection professionals, in consultation with the relevant regulatory authorities as appropriate, when deciding how to proceed (see also "Application of the Guideline").

2.3 Reference level and effective dose

The ICRP recommends that exposures from natural and legacy sources be managed using a reference level between 1 mSv/y and 20 mSv/y (ICRP, 2007).

The basis for the MACs in this document is a reference level of 1 mSv/y, which is at the lowest end of the recommended range. This value is consistent with the reference level recommended in the international safety standards (IAEA, 2014) and is acknowledged by the World Health Organization (WHO, 2018). More discussion of how Health Canada's recommendations compare with those of international organizations and peers is provided in Section 6 and Appendix B.

The reference level is neither a limit nor a boundary between what is considered safe and unsafe. Instead, it is a level that involves minimal risk and is reasonably achievable for most water systems in Canada.

The reference level is expressed in terms of the effective dose, which is a concept developed by the ICRP to relate ionizing radiation exposure to the risk of stochastic health effects, primarily cancer. It combines information about the physical and chemical properties of radionuclides with data that characterizes biological response. This allows exposures to different radionuclides via different pathways to be easily summed and/or compared to limits and reference levels. Estimates of average exposures to different sources of background radiation, as shown in Section 1, are expressed using effective dose. The unit for the effective dose is the sievert (Sv). Because the sievert is a very large unit, doses in the range relevant to drinking water are typically expressed as millisieverts (mSv), or 1/1000 of a sievert.

The ICRP has developed dose coefficients (dose per unit intake of a radioactive substance) to facilitate these calculations (ICRP, 2012, 2017). By using dose coefficients for the ingestion of radionuclides, along with information on radionuclide concentrations and consumption rates, it is possible to estimate the dose that an individual would receive from a given source of drinking water. Health Canada used effective dose coefficients and standard assumptions to derive the MACs (see Section 3).

3.0 Assessment and Implementation

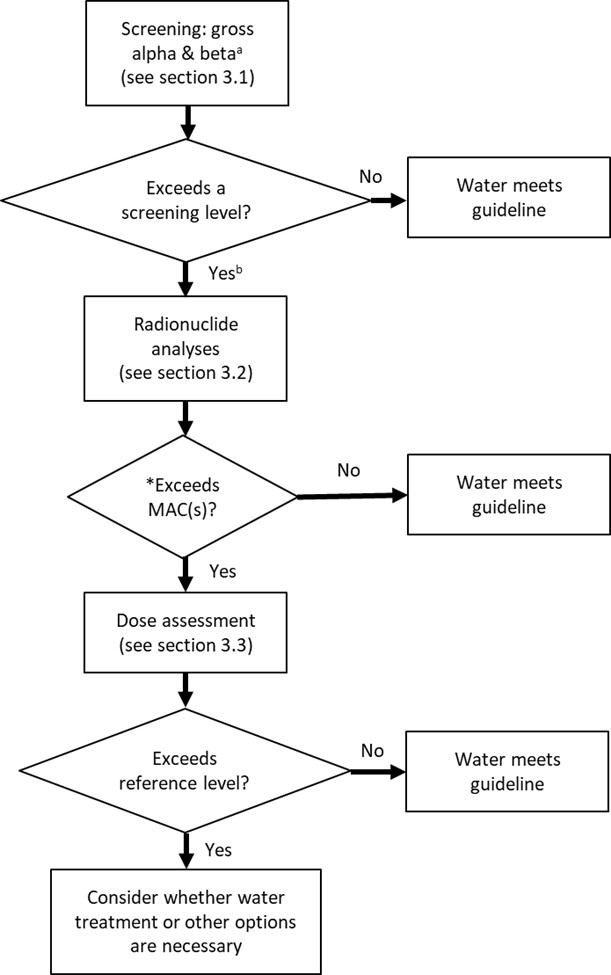

Figure 3 describes the process for assessing radiological parameters in drinking water. The process begins with approximate and relatively inexpensive laboratory measurements. It then advances through more precise assessments when the results indicate that this is necessary. Each of these steps is described in more detail in Sections 3.1 and 3.2.

The MACs apply to water that is being consumed, so sampling and monitoring should be reflective of the water that comes out of the tap (WHO, 2018). For existing systems, if water is treated before consumption, it should be sampled after treatment because treatment can reduce the activity concentrations of many radionuclides. In general, the concentration of the radionuclides in Table 1 is not expected to change in the distribution system, so it is appropriate to measure the water at the drinking water treatment facility after treatment or at storage reservoirs prior to distribution. For supplies of drinking-water that are not treated, such as some small water supplies, the radionuclides can be measured at the source or the point of collection. Ideally, some measurements should be made at the point of consumption, that is at the tap or communal point of collection; however, this may not be practicable for large distribution systems.

For a new drinking water supply, measurements of radionuclides should be made using the source water, as part of characterizing it and determining its suitability for drinking. The existing treatment technologies and strategies in place to address other contaminants should also be taken into account. This characterization should be carried out along with assessing microbiological and chemical risks as part of developing water safety plans.

Alpha and beta radiation activity criteria, MAC values, reference values in Appendix C, the summation formula, and the reference level were developed based on annual exposure. This is important to bear in mind when initially characterizing a water source. It may be necessary to repeat the gross alpha and beta measurements and/or radionuclide analyses to capture fluctuations and properly establish a baseline. Sampling and measuring once per season for the first year is recommended for water sources that approach or exceed the MAC.

The dose for infants (less than 1 year old) is relatively higher than that for older children and adults at the MAC. If the screening criterion for gross alpha or gross beta is exceeded, it is recommended that an alternative source of water (such as bottled water) be used for the preparation of infant formula. The water is acceptable for children (over 1 year old) and adults to consume and use.

Ongoing monitoring or periodic review may be necessary if there is a reason to expect that radionuclide levels might change (for example, to confirm that a treatment system is functioning properly) or to meet regulatory requirements. This is discussed in Section 6.

Figure 3 - Text Equivalent

- Step 1: Screening using gross alpha & beta (See Section 3.1)Footnote a

- Step 2: Exceeds a screening level?

- If no, then the water meets guideline criteria, otherwise proceed to Step 3Footnote b

- Step 3: Radionuclide analyses (See Section 3.2)

- Step 4: Exceeds MAC(s) or HBV(s)?

- If no, then water meets guideline criteria, otherwise proceed to Step 5.

- Step 5: Dose Assessment (see Section 3.3).

- Step 6: Exceeds reference level?

- If no, then water meets guideline criteria, otherwise proceed to Step 7

- Step 7: Consider whether water treatment or other options are necessary

- Figure 3 Footnote a

-

Gross beta measurements should be corrected for the presence of potassium-40 (WHO, 2022). Refer to specific gross alpha/beta measurement techniques for details, such as those listed in Table 3.

- Figure 3 Footnote b

-

If the water is being used for the preparation of infant formula, consider using an alternative source (such as bottled water).

3.1 Gross alpha and beta screening

Since all the key radionuclides targeted in routine drinking water assessment emit alpha and/or beta particles, a water sample can usually be quickly screened using analysis methods that measure gross alpha or gross beta activity (see Section 4.1).

Gross alpha and beta screening is a relatively inexpensive way of identifying water samples that do not require further investigation using more expensive tests. If the results for both the gross alpha and gross beta measurements are below the screening criteria, the water meets the guideline.

The screening criterion established for each test corresponds to an annual dose of no more than 0.3 mSv, or about 1/3 of the reference level dose. Health Canada bases the gross alpha screening criterion on Po-210 (0.5 becquerel per litre [Bq/L]) and the gross beta screening criterion on Ra-228 (1 Bq/L), as these radionuclides have the highest dose coefficients among those with either a MAC or a reference value in Appendix C (ICRP, 2012, 2017). This approach is conservative.

Results that exceed the screening criteria do not necessarily mean that MACs are exceeded. There are a number of reasons why gross alpha and/or beta measurements are higher than the criteria, some of which are described in Appendix D. Exceedances should be investigated by doing at least one of the following: repeating the analysis (if there is sufficient quantity of the sample); repeating the screening procedure at different times of the year (to better characterize average annual levels); or undertaking radionuclide-specific analysis. Decisions on the best way to proceed should be made in consideration of available resources and in consultation with authorities, as appropriate.

3.2 Radionuclide-specific analysis

If water does not meet the screening criteria, the next step is to measure specific radionuclides and compare their activity levels with the MACs (see Section 4.2).

The MACs for the individual radionuclides were derived using adult dose coefficients (ICRP, 2012, 2017), assuming a drinking water intake of 1.53 L/day (or 558 L/year), and a reference level of 1 mSv per year.

The MAC for a given radionuclide in drinking water is derived using the following formula:

MAC (Bq/L) =[1mSv/year/(558 L/year × DC (Sv/Bq) × 1000 mSv/Sv)]

where:

- 1 mSv/year is the reference level

- 558 L/year is the drinking water consumption rate for an adult, which corresponds to a daily consumption rate of 1.53 L/day. This value is consistent with that used by Health Canada in other drinking water guidelines (Health Canada, 2021a)

- DC is the ingestion dose coefficient for a member of the public based on the ICRP 119 standard. This provides an estimate of the 50-year committed effective dose for adults resulting from a single intake of 1 Bq of a given radionuclide

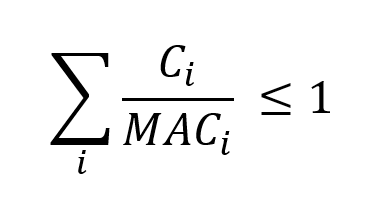

3.2.1 Summation formula

The radiological effects of two or more radionuclides in the same drinking water source are assumed to be additive. Therefore, the following summation formula should be satisfied in order to demonstrate compliance with the guidelines:

Summation formula - Text Equivalent

The formula adds, for each radionuclide, its concentration divided by its maximum acceptable concentration. The total must be less than or equal to 1.

where Ci and MACi are the observed and maximum acceptable concentrations (MAC), respectively, of each contributing radionuclide. Only those radionuclides that are detected with at least 95% confidence should be included in the summation. Detection limits of undetected radionuclides should not be used in the concentration term (Ci). Otherwise, a situation could arise where a sample fails the summation criterion, even though no radionuclides are present.

Chemical MACs should not be included in the radiological summation formula. For example, total natural uranium does not have a radiological MAC, but instead has a chemical MAC, which is more limiting. Because uranium at the chemical MAC generates a very small radiological dose (~0.01 mSv/y), uranium should not be included in the summation formula.

3.3 Dose assessment and mitigation decisions

The MACs were derived using default values for some parameters, such as consumption rates. If radionuclide concentrations exceed the MAC (or 1, if using the summation formula), it might be worthwhile to characterize doses more accurately. The results, when compared against the reference level, can inform decisions on next steps. The dose assessment will depend on many factors, including the radionuclides present in the drinking water and the seasonal variations in measured concentrations. It is recommended to contact a radiation protection expert to perform this assessment and provide recommendations, in consultation with authorities as appropriate. For private wells, the risk tolerance of the individuals served and the impacts of mitigation, including cost, are important and relevant considerations when deciding how best to proceed. For public or larger community-based systems, exceedances should generally be mitigated. Treatment options are discussed in Section 5.

4.0 Analytical considerations

A brief summary of analytical methods used to perform the gross alpha and gross beta measurements of radionuclides with MACs or reference values in Appendix C is provided in Table 3. Validated methods referenced here include those from the United States Environmental Protection Agency (U.S. EPA), International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the American Society for Testing and Materials (ASTM). Laboratories in Canada and the U.S. will often refer to these methods directly, or may use them as a basis for developing, validating or testing their own methods. Water samples should be collected in accordance with the guidance provided in Section 3.0. Water samples should be tested by a laboratory with an accreditation relevant to the analysis of radionuclides in drinking water. The laboratory can provide more information about the collection procedure, including sample container and volume.

The detection limits cited in Sections 4.1 and 4.2 are based on those in the reference methods. In practice, detection limits may vary, depending on sample-specific parameters, counting time and modifications to the reference method by the laboratory.

4.1 Gross alpha and gross beta measurements

Analyzing drinking water for gross alpha and gross beta radiation (excluding radon) can be done by evaporating a known volume of the sample until dry and then measuring the radiation activity in the residue. Since alpha radiation is easily absorbed in a thin layer of solid material, the method's reliability and sensitivity in determining alpha activity may be reduced in samples with a high total dissolved solids (TDS) content. Some methods require the subtraction of potassium-40 (K-40) to accurately determine the gross beta activity. The total potassium in the sample by mass can be measured by using atomic absorption spectrophotometry, and the K-40 activity (Bq) can then be calculated by applying the factor of 27.6 Bq/g. Recommended methods for determining gross alpha and beta activity are listed in Table 3, and the detection limit varies with laboratories, depending on equipment and procedures used. On average, an interlaboratory comparison puts the detection limit in the range of 1.4–340 mBq/l for gross alpha and 0–424 mBq/l for gross beta (Jobbagy, 2016).

| Parameter | Reference Method | Preparation | Detection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gross alpha | ISO 9696 (2017) | Evaporation | Gas proportional counting |

| Gross alpha | APHA 7110 C (1998) |

Co-precipitation | Gas proportional counting |

| Gross beta | ISO 9697 (2018) |

Evaporation | Gas proportional counting |

| Gross alpha and gross beta | EPA 900.0 (1980a) |

Evaporation | Gas proportional counting |

| Gross alpha and gross beta | ASTM D7283 (2017) |

Evaporation | Liquid scintillation counting |

Although gross alpha and gross beta activity screening can reduce the need for specific radionuclide analyses, which are more costly, it has a number of drawbacks as a measurement tool. These drawbacks include false-positive results, particularly for gross alpha and beta measurements when dissolved radon is present. False positives in the range of tens of becquerels per litre (Bq/L) are fairly common, but, in many of these cases, detailed analyses will show that all radionuclides of interest comply with the MAC.

4.2 Radionuclide-specific analysis methods

Radionuclide-specific analysis should be limited to radionuclides with a MAC value (Table 4), unless there is prior knowledge of the source of contamination (see Appendix C for more information). Analytical methods for detecting radionuclides with a MAC are listed in Table 5.

| Exceedance | Radionuclide |

|---|---|

| Gross alpha | Radium-226 |

| Gross beta | Lead-210 |

| Gross beta | Radium-228 |

| Radio nuclide | Reference Method | Preparation | Detection Method | DL | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lead-210 | ASTM D7535 (2015) |

Solid-phase extraction | Gas proportional counting | 37 mBq/L | If high radon is also suspected, sample should be agitated to remove dissolved radon before storage. (Drage et al. 2005) |

| Lead-210 | ISO 13163 (2021c) |

Solid-phase extraction | Liquid scintillation counting |

20–50 mBq/L | If high radon is also suspected, sample should be agitated to remove dissolved radon before storage. (Drage et al. 2005) |

Radium- 226 and -228 |

ISO 22908 (2020b) |

Co-precipitation and resuspension | Liquid scintillation counting | 0.01 Bq/kg (Ra-226), 0.06 Bq/kg (Ra-228) | N/A |

Radium- 226 |

ASTM D2460-07 (2013a)/ EPA 903.0 (1999) ASTM D3454 (2022)/ EPA 903.1 (1980c) |

Co-precipitation Radon emanation |

Alpha spectrometry or gas proportional Counting Scintillation chamber |

ASTM method: 3.7–37 mBq/L | N/A |

| Radium-228 | EPA 904.0 (2022) |

Co-precipitation | Gas proportional counting | Not reported | N/A |

|

DL – detection limit; Bq/L – becquerels per litre; mBq/L – millibecquerels per litre; Bq/mL– becquerels per millilitre; Bq/kg – becquerels per kg; N/A – not applicable |

|||||

5.0 Treatment considerations

Several technologies are available to reduce concentrations of radiological contaminants in drinking water at both the municipal and residential scale. At the municipal scale, technologies include adsorption, ion exchange (IX), reverse osmosis (RO), precipitation and lime softening. The selection of an appropriate treatment process will depend on many factors, including the raw water source and its characteristics, the nature of the radionuclides present in the water, and the operational conditions of the selected treatment method. Pilot- and bench-scale testing is critical to ensure the source water can be successfully treated and to optimize operating conditions. In addition, the handling and disposal of the treatment residuals (waste produced by treatment) need to be carefully addressed when removing radionuclides from drinking water, as a low level of radioactivity may be present (see Section 5.4 for more detail).

At the residential scale, certified treatment devices relying on RO and distillation are expected to be effective for removal of radium and lead. Devices are generally not expected to contain enough radioactivity to warrant special precautions by homeowners. The liquid and solid waste from treatment devices may be eliminated in sewer or septic systems, and municipal landfills, as appropriate.

5.1 Radioisotope chemistry

For the purposes of treatment, the radioactive isotope of an element has the same chemical and physical/chemical behavior as the stable element. Additionally, although radioisotopes possess differing decay rates and modes of decay, achieving 95% removal of Ra-226, for example, also results in 95% removal of Ra-228 when they are present together, regardless of the ratio of their initial activities (Clifford, 2004).

5.2 Municipal-scale

Most radionuclides can be effectively treated in municipal-scale treatment facilities.

The best technologies available for the removal of radionuclides at this level are ion exchange (IX), reverse osmosis (RO) and lime/precipitation softening (U.S. EPA, 2000b; WHO, 2022). Removal efficacy is affected by the characteristics of the source water, including pH, influent concentration, competing ion concentration (especially sulphate), and alkalinity. Generally, IX resins exhibit a degree of selectivity for various ions, depending on the concentration of the ions in solution and the type of resin selected. IX capacity and resin selectivity are important considerations when selecting a resin for removal of a specific radionuclide.

For RO, the reported removal efficacy typically ranges from 70% to 99% (Annanmäki, 2000). IX removal efficacy has been reported to be as high as 95%, but is dependent on the specific IX media used (U.S. EPA, 2000a).

Both the RO and IX technologies can lower water pH and increase corrosion. In the anion exchange process, freshly regenerated IX resin removes the bicarbonate ions when removing contaminants. This causes reductions in pH and total alkalinity during the initial 100-bed volumes (BVs) of a run, and may require raising the pH of the treated water at the beginning of a run to avoid corrosion (Clifford, 1999; Wang et al., 2010; Clifford et al., 2011). Similarly, the frequent regeneration of an IX resin results in the significant and continual decrease of the water pH, also impacting corrosion (Lowry, 2009, 2010). Since RO continually and completely removes alkalinity in water, it will continually lower the pH of treated water and increase its corrosivity. Therefore, the product water pH must be adjusted to avoid corrosion issues in the distribution system, such as the leaching of lead and copper (Schock and Lytle, 2011)

5.2.1 Lead

The Pb-210 isotope behaves chemically like elemental lead. For this reason, treatment technologies that remove elemental lead will also remove the radioactive isotope. Conventional water treatment, including settling, aluminum (alum) or ferric sulphate coagulation and filtration, is reasonably effective at removing lead from drinking water. Adsorption, IX and lime softening at elevated pH are also effective for the removal of lead. More information on treatment can be found in the Guideline Technical Document for Lead (Health Canada, 2019)

5.2.2 Radium

The lime softening process precipitates radium with calcium and magnesium hardness and is also effective for removal or inorganic contaminants (for example, arsenic, barium, chromium) from drinking water sources. Brink et al. (1978) reported lime softening achieved radium removal ranging from 75% to 96% with increased removal at higher pH, (pH 9.4 and 10.6, respectively). The lime softening process may be impractical to use unless hardness reduction is a concurrent treatment goal. Lime softening may require re-carbonation (to reduce pH) and the addition of corrosion inhibitors to protect the distribution system from corrosion related to the removal of hardness and alkalinity (U.S. EPA, 2012).

The IX process to remove radium uses a strong acid cation exchange media (that is, the resin is regenerated by an acid solution or NaCl) (Annanmäki, 2000; Clifford, 2004; Civardi, 2022). Along with IX, RO and lime softening, Table 6 shows the treatment technologies capable of removing both Ra-226 and Ra-228 which include green sand filtration, precipitation with barium sulphate, electrodialysis/electrodialysis reversal and hydrous manganese oxide filtration (U.S. EPA, 2000b).

| Treatment method | Removal efficacy | Comment |

|---|---|---|

| IX softening (Na+, SAC) | > 95% | Operate to hardness breakthrough; NaCl regeneration |

Ba(Ra)SO4 precipitation |

50–95% | BaCl2 added to feed water before filtration |

| MnO2 adsorption | 50–95% | Use preformed MnO2 or MnO2-coated filter media |

| RO | > 99% | Effective, some operational challenges |

|

Adapted from Clifford (2004); IX – ion exchange; RO – reverse osmosis; SAC – strong acid cation |

||

5.2.3 Radon

High-performance aeration is considered the best available technology to remove radon from groundwater supplies. High-performance aeration methods include packed-tower aeration and multi-stage bubble aeration and can achieve up to 99.9% removal. However, these methods may also generate significant airborne radon. Adsorption using granular activated carbon (GAC), with or without IX, can also remove a large percentage of radon, but is less efficient and requires large amounts of GAC, making it less suitable for large systems.

GAC and point-of-entry GAC may be appropriate for very small systems under some circumstances (U.S. EPA, 1999).

5.3 Distribution system considerations

Radionuclides in treated water can be deposited in the distribution system, where they accumulate (Friedman et al., 2010). Higher concentrations of radionuclides in the water entering the distribution system increases the potential for accumulation. If chemical changes or physical disturbances occur, radionuclides can be remobilized in the water, potentially resulting in increased concentrations at the tap. Discoloration (red or grey water) episodes are likely to be accompanied by the release of accumulated contaminants, including radionuclides, because they are readily adsorbed onto aluminum, iron and manganese deposits (Health Canada, 2019, 2021b, 2025). The presence of aluminum solids are generally associated with (surface) water systems that apply an aluminum coagulant during treatment, and/or have high measurable levels of aluminum in their treated water, as well as distribution systems with cement-based or cement-mortar lined pipes (Friedman et al., 2010). However, naturally-occurring aluminum can also be found in groundwater and result in the generation of aluminum sediments (Health Canada, 2021b).

Radionuclides that, when present, can adsorb and accumulate in distribution systems include Pb-210, Ra-226 and Ra-228 (Valentine and Stearns, 1994; Field et al., 1995; Reiber and Dostal, 2000). Friedman et al. (2010) found that Ra-226 was the sixth most concentrated trace element in deposit samples, with a median concentration of 9.1 pCi/g (0.33 Bq/g). The median levels in water associated with hydrant flush solids and pipe specimens were 3.7 pCi/L (0.14 Bq/L) and 0.39 pCi/L (0.01 Bq/L), respectively, (more than a ten-fold difference).

The accumulation of radiological and trace inorganic contaminants in the drinking water distribution system is influenced by a variety of factors. These include contaminant concentrations in the treated water, water quality conditions in the distribution system, pipe material, co-occurrence of iron, manganese and aluminum in the pipe scale deposits, and pH and redox conditions in the water. The primary mechanisms by which trace contaminants (for example, radionuclides, arsenic, lead) accumulate in the distribution system are adsorption and co-precipitation to substrate solids, particularly iron particles and corrosion scales (for example, hydrous iron oxides), aluminum solids and manganese solids (for example, hydrous manganese oxides) (Hill et al., 2010; Kim and Herrera, 2010; Friedman et al., 2010, 2016; Han et al., 2018; Gao et al., 2019).

Studies have shown that changes in water chemistry (pH and redox) or water treatment processes, or physical disturbances can release these radionuclides from pipe scale deposits and cause remobilization and elevated concentrations at the tap. Consequently, discoloured water should not be considered safe to consume or treated as only an aesthetic issue. Such an event should also trigger sampling for metals and radionuclides as well as potentially requiring additional distribution system maintenance. When radionuclides are present in the source water, utilities should determine if they also need to be included in their monitoring and distribution system management plans.

5.4 Management of residuals

To assess disposal options and regulatory requirements, the waste stream (residuals) generated must first be characterized. Characterization must take into account the treatment technology used, the characteristics of the source water (including the raw water concentrations of radiological contaminants and the presence of co-occurring radionuclides), and concentrations of other contaminants in the residuals. Treatment technologies produce a variety of solid waste residuals (spent resin filter media, spent membranes and sludge), liquid waste residuals (brine, backwash water, rinse water, acid neutralization streams and concentrate), and can produce elevated gamma fields in the treatment media. The characteristics and concentration of the radionuclide in the residuals will vary with the treatment technology used and its efficacy, which is associated with factors such as frequency of media replacement, regeneration and filter backwash.

Utilities should conduct pilot tests of the treatment technologies to determine, for example, the regeneration schedule when using IX and the associated waste residuals. Special precautions may be required when the waste stream is treated, stored, disposed of or transported. Operators may need special training to deal with these residuals. Residuals generated by drinking water treatment facilities should be assessed to determine if they should be treated as Naturally Occurring Radioactive Materials (NORM) for disposal (e.g., Health Canada, 2014). If so, the appropriate authorities should be consulted for the requirements associated with their disposal. A list of provincial and territorial radiation protection regulatory authorities can be found on the Federal Provincial Territorial Radiation Protection Committee (FPTRPC) website. A web-based tool can also be used to estimate the removal efficacy for radionuclides and co-contaminants from drinking water, as well as radioactive concentrations in the waste residual (U.S. EPA, 2005).

5.5 Residential-scale

When the removal of radionuclides is desired at the household level—for example, when a household gets its drinking water from a private well—a residential drinking water treatment unit may be an option. Units classified as residential scale may have a rated capacity to treat volumes greater than that needed for a single residence and, therefore, can also be used in small systems.

Before a treatment unit is installed, the water should be tested to determine the general water chemistry and radionuclide concentrations. Periodic testing by an accredited laboratory should be conducted on both the water entering the unit and the treated water, to verify that the treatment unit is effective. Units can lose their removal capacity with use over time and will need to be maintained and/or replaced. Consumers should check the expected service life of the components in the treatment unit and service it when required according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

Health Canada does not recommend specific brands of drinking water treatment units. However, it strongly urges consumers to use treatment units that have been certified by an accredited certification body. This ensures that the treatment unit meets the appropriate NSF International/American National Standards Institute (NSF/ANSI) standards. The purpose of these standards is to establish minimum requirements for the materials, design and construction of drinking water treatment units. The certification of treatment units is conducted by a third party and ensures that the materials in the unit do not leach contaminants into the drinking water (that is, material safety). The standards also specify performance requirements, that is, the removal efficacy that must be achieved for specific contaminants that may be present in water supplies.

Certification organizations (third parties) provide assurance that a product conforms to applicable standards and must themselves be accredited by the Standards Council of Canada. Accredited organizations in Canada include:

- CSA Group

- NSF International

- Water Quality Association

- UL LLC

- Bureau de normalisation du Québec (available in French only)

- International Association of Plumbing and Mechanical Officials

- ALS Laboratories Inc.

An up-to-date list of accredited certification organizations can be obtained from the Standards Council of Canada.

The most common types of devices available for residential-scale treatment include IX and RO systems. In general, the removal efficacy of point-of-use and point-of-entry treatment technologies is expected to be similar to those for municipal-scale treatment technologies.

At the residential scale, devices are generally not expected to contain enough radioactivity to warrant special precautions by homeowners. The liquid and solid waste from point-of-use or point-of-entry treatment units may be eliminated in sewer or septic systems, and municipal landfills, respectively.

5.5.1 Lead-210

No treatment devices are currently certified specifically for the removal of Pb-210. However, since this isotope behaves chemically like elemental lead, devices certified for the removal of lead will also remove the radioactive isotope.

Drinking water treatment devices can be certified to NSF/ANSI Standard 53 (Drinking Water Treatment Units – Health Effects) (adsorption) or NSF/ANSI Standard 58 (Reverse Osmosis Drinking Water Treatment Systems) for lead removal (NSF, 2023a, 2024a). A number of certified residential treatment devices are available to remove lead from drinking water using adsorption (that is, carbon block/resin) and RO. An infographic is available to aid in the selection of a certified adsorption filter for lead removal (https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/publications/healthy-living/infographic-finding-drinking-water-filter.html). Drinking water treatment devices certified to NSF/ANSI Standard 62 (Drinking Water Distillation Systems) can also be used, as this distillation technology is also effective in removing lead at the residential scale (NSF, 2023b). However, no certified distillation systems are currently available.

5.5.2 Radium

Drinking water treatment devices certified to remove Ra-226 and Ra-228 from drinking water using IX and RO technologies are available. Devices certified to meet NSF/ANSI Standard 58 (Reverse Osmosis Drinking Water Treatment Systems) and Standard 44 (Residential Cation Exchange Water Softeners) are capable of reducing radium levels from an influent concentration of 25 picocuries per litre (pCi/L) (925 mBq/L) to a maximum concentration of 5 pCi/L (185 mBq/L) or less (NSF, 2024a,b).

5.5.3 Radon

The best approach to address radon (Rn-222) outgassing is to test the air and remediate the source of radon in the home (see Section 1.2.3). However, if a homeowner chooses to remove Rn-222 from drinking water, there are certified drinking water treatment devices. Generally, treatment technology using activated carbon adsorption technology is effective. Treatment devices certified as meeting NSF/ANSI Standard 53 (Drinking Water Treatment Units – Health Effects) (adsorption) can reduce radon levels from an influent concentration of 4000 pCi/L (148 Bq/L) to a maximum concentration of less than 300 pCi/L (11 Bq/L) (NSF, 2023a).

These filtration systems may be installed at the tap (point of use) or at the location where water enters the home (point of entry). Point-of-entry systems are preferred for volatile compounds such as Rn-222. They remove Rn-222 from water for household uses such as bathing and laundry as well as for cooking and drinking, preventing its release inside the home. When certified point-of-entry treatment devices are not available for purchase, systems can be designed and constructed from certified materials. Periodic testing by an accredited laboratory should be conducted on both the water entering the system and the treated water, to verify that the treatment system is effective.

6.0 Management Strategies

All water treatment systems should implement a comprehensive, up-to-date, risk management water safety plan. A source-to-tap approach should be taken to ensure water safety is maintained (CCME, 2004; WHO, 2012, 2022, 2023). These approaches require a system assessment to characterize the source water, describe the treatment barriers that prevent or reduce contamination, identify the conditions that can result in contamination, document areas at risk and implement control measures. Operational monitoring is then established, and operational/management protocols, such as standard operating procedures, corrective actions and incident responses, are instituted. Compliance monitoring is put in place and other protocols to validate the water safety plan are implemented (for example, record keeping, consumer satisfaction). Operator training is also required to always ensure the effectiveness of the water safety plan (Smeets et al., 2009).

6.1 Control strategies

In water sources with higher than acceptable radionuclide concentrations, one or more treatment options (see Section 5.0) may be implemented. Non-treatment strategies such as controlled blending prior to system entry-points or use of alternative water supplies can also be considered (see "Application of the Guideline." When the option of a treatment technology is chosen, pilot-scale testing should be done to ensure the source water can be successfully treated and process design is established. Attention must be given to the water quality and compatibility of a new source prior to making any changes (in other words, switching, blending, and interconnecting) to an existing water supply. For example, if the new water source has a different chemistry profile than existing sources, it may cause destabilization or desorption of Ra-226 or Ra-228 (and metal contaminants) from iron scales from the distribution system.

As noted in Section 5.3, radionuclides are readily adsorbed onto aluminum, iron and manganese deposits. Managing the levels of these metals in the distribution system will minimize the potential for the accumulation and release of radionuclides in the distributed water (Health Canada 2019, 2021b, 2025). The proper development of a groundwater well during its construction can also minimize aluminum sediments produced (and accumulated) following rest periods, during start-up and routine pumping of wells (Health Canada, 2021b).

Generally, the distribution system should be managed such that drinking water is transported from the treatment plant to the consumer with minimum loss of quality. Distribution system maintenance activities such as a routine main cleaning and flushing program can help to sustainably minimize accumulation and release of contaminants such as radium (Hill et al., 2018). Maintaining of consistent distribution system chemistry is also important to reduce risk of destabilization and desorption from sinks such as aluminum, iron and manganese.

6.2 Monitoring

6.2.1 Source water characterization

Water sources should be characterized to determine if radioisotopes are present in the source water and periodic reviews are recommended in situations where human activities or environmental changes could increase the level of radionuclides in drinking water. If the drinking water source is groundwater, yearly monitoring is recommended. In cases where radioisotopes are not present and/or appropriate treatment is in place, authorities may consider reduced monitoring to about every five years as part of a sanitary survey, and in consultation with the appropriate drinking water authority.

Conversely, when there are significant changes to the treatment system, land use, or other conditions which may adversely affect water quality, and measurements approach the MAC (or if the sum of the ratios of the observed concentration to the MAC for each contributing radionuclide approaches 1), then the sampling frequency should be maintained or increased.

Municipal scale systems may choose to adapt gross alpha and beta screening levels for use in periodic reviews. For example, if the gross levels initially measured are above the screening criteria, but radionuclide-specific testing shows that the water meets the guideline, the measured gross levels can be utilized as the screening criteria for periodic reviews. This is possible because each screening criterion represents a fraction of the reference level. Likewise, in instances where one or two radionuclides predominately contribute to the total dose, the periodic reviews can focus on them. The decision on which method to use is based on efficacy and cost.

In areas where facilities generate environmental releases of radionuclides that are likely to enter drinking water sources, drinking water authorities may wish to establish information sharing agreements. Such agreements can allow monitoring data to be shared and early notification of releases, so that drinking water treatment plant operators can take appropriate action. If ongoing exposure to levels exceeding the MACs is likely, a jurisdiction may choose to apply additional measures based on the expected level of radionuclides in the source water and the frequency of exceedances in order to mitigate risk.

6.2.2 Operational/treatment

Water treatment systems that treat their water to remove radiological contaminants will need to conduct frequent monitoring of raw and treated water to make necessary process adjustments. Operational monitoring should be implemented to confirm whether the treatment process is functioning as required (such as paired samples of source and treated water to confirm the efficacy of treatment). This will ensure that treatment processes are effectively removing them to concentrations below the MAC.

The frequency of operational monitoring will depend on the treatment process. For example, if adsorption is used, at least quarterly monitoring should be conducted, or a method to estimate BVs to breakthrough should be used, to predict the need for media replacement.

6.2.3 Compliance monitoring

Measurements can be evaluated against the screening criteria in order to assess whether individual radionuclide measurements are required. If the screening criteria are exceeded, then analysis of the treated water can be done for the individual radioisotope(s) to determine compliance with its MAC. Exceedances of the MACs should be investigated with additional monitoring, and a risk assessment should be conducted to determine the most appropriate way to handle the exceedance.

It is recommended that compliance monitoring for radioisotopes be conducted annually, at a minimum, to confirm the MAC is not exceeded. The frequency may be reduced if no failures have occurred in a defined period, as determined by the responsible authority.

6.2.4 Distribution system

Since Ra-226 and Ra-228 can accumulate and be released in distribution systems, monitoring should be conducted at a variety of locations in systems where aluminum, manganese or iron may be present in the distribution or plumbing systems (that is, concrete, cast iron or galvanized iron pipes). The concentration of radioisotopes in drinking water should also be monitored at the tap when discolouration (coloured water) events occur to determine if concentrations exceed the MAC.

Releases tend to be sporadic events, making it difficult to establish a routine monitoring program to effectively detect radioisotopes in tap water resulting from iron release within the distribution system.

Additionally, risk factors associated with distribution system accumulation and release (such as long detention time, dead-ends, areas with unlined cast iron pipes) should be documented and could be used as indicators of where to monitor for radiological contaminant releases. Event-based monitoring may be needed in circumstances where the risk of release is increased, such as following any hydraulic disturbances to the system, main breaks or during hydrant flushing, or changes in water chemistry, such as changes in pH, temperature, source water type or uncontrolled source water blending, chlorine residual, or uncontrolled disinfectant blending.

Distribution system sampling locations should ideally be located where there are increased risk factors for radiological contaminant release (for example, areas known to have corroded/tuberculated pipes, pipe materials, biofilm, high water age) and event-based release risk factors. Monitoring should also be conducted during any discoloured water event and continue until the event is resolved; and in response to customer complaints. It is important to note that the absence of discoloured water should not be interpreted as the absence of a release of radiological contaminants.

Monitoring for radioisotopes should be done in conjunction with metals that can co-occur in the distribution system and have also been shown to be released with iron (for example, As, Pb, Mn). Water treatment systems that undertake preventive measures with stable hydraulic, physical and water quality conditions and have baseline data indicating that radioisotopes are minimal or do not occur in the system may conduct less frequent monitoring.

6.2.5 Residential

Homeowners with private wells using residential treatment devices should conduct testing on both the water entering the treatment device and the treated water to verify that the treatment device is working properly.

7.0 International Considerations

7.1 Reference level

These guidelines are founded on a reference level of 1 mSv/y, which is in line with international recommendations, including those by the ICRP and IAEA (ICRP, 2007; IAEA, 2014). The WHO acknowledges the IAEA-recommended reference level of 1 mSv/y, but also goes beyond this to recommend a modified reference level, or "individual dose criterion," of 0.1 mSv/y (WHO, 2018, 2022). This lower value is based on the ICRP-recommended dose constraint for a planned exposure situation of the prolonged component from long-lived artificial nuclides. Because planned exposure situations and artificial radionuclides are managed through other means and are out of scope for this guidance document, these guidelines are based on the lowest end of the band that ICRP recommends for reference levels for existing exposure situations (i.e., 1–20 mSv/y), and the requirements outlined in the Radiation Protection and Safety of Radiation Sources: International Basic Safety Standards (2014).

For many communities, especially those that depend on groundwater sources in Canada, a level of 0.1 mSv/y is unjustified given the emotional and financial stress it may place on communities or homeowners. From a health perspective, neither 0.1 mSv/y nor 1 mSv/y poses a significant risk. In addition, the 1 mSv/y reference level is already met in most drinking water supplies in Canada, and in many cases, should be easily achievable by treatment for those that test above this level.

The reference level of 1 mSv/y is applied in this guideline as it is in line with international recommendations, is reasonably achievable in most cases, and is not expected to place an unfair burden on communities and individuals.

7.2 Methodology

These guidelines were developed following the methodology recommended by the WHO (WHO 2018, 2022). This includes:

- establishing a reference level

- screening water samples using gross alpha and beta activity levels that are derived from the reference level

- if alpha/beta levels are exceeded, measuring individual radionuclide concentrations and comparing them to rounded guidance concentration levels that correspond to the reference level

Note that caution must be exercised if trying to compare different guidance values across organizations. Different organizations may consider different technical, economic, environmental and societal factors when choosing a reference level (or similar value). Screening levels may be based on different reference levels, or fractions of those levels, as well as different radionuclides, drinking water consumption rates and rounding conventions. MACs (or similar values) may also be based on different reference levels, drinking water consumption rates or rounding conventions, or may be defined completely differently. In addition, the various guidance values may be associated with different actions or different optimization expectations.

8.0 Rationale for the maximum acceptable concentration

MACs have been established for three natural radionuclides (Pb-210, Ra-226 and Ra-228) potentially found in Canadian drinking water.

The MACs were determined using internationally accepted equations and principles. Exceedance does not pose immediate risk but triggers investigation. The MACs were derived from an annual reference dose of 1 mSv from ingestion only and assuming a consumption rate of 1.53 L/day. Health risks from inhalation or skin absorption at the levels of the MACs are negligible. Treatment and analytical limitations are not an issue at the level of the MACs..

The treatment of water supplies to remove radionuclides should be governed by the principle of keeping exposures low, with social, economic, and environmental considerations being taken into account. Both the screening criteria, and the MACs for radionuclides apply to routine operational monitoring of existing or new water supplies, but do not apply in the event of contamination during an emergency involving a large release of radionuclides into the environment.

9.0 References