Internal Audit of the Management and Oversight of Visa Application Centres

Internal Audit & Accountability Branch

November 30, 2020

Table of contents

I. Background

Introduction

- The Audit of the Management and Oversight of Visa Application Centres (VAC) was included in the Department’s 2019-2021 Risk-Based Audit Plan, which was reviewed by the Departmental Audit Committee (DAC) at the February 2019 meeting and subsequently approved by the Deputy Minister.

- VACs are third party service providers managed by private companies authorized to provide specific administrative support services and biometric collection services to visa applicants under the VAC Contracts with the Government of Canada. VACs accept temporary resident applications, travel documents for permanent residents abroad and passports for transmission to and from IRCC offices. They do not process applications nor do they play a role in the decision making process. In addition to VACs, Contact Centres (managed under the same contracts) are used to provide channels of communication to applicants including email, webchat and telephone. Contact Centres operate directly inside VACs or other entities (by way of co-location) or in standalone facilities.

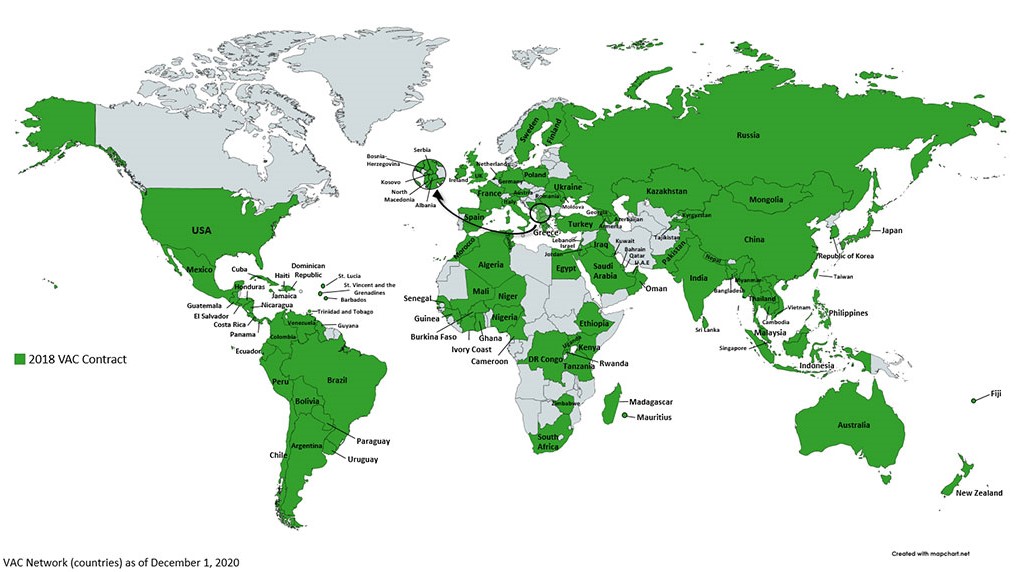

Canada’s VAC network is one of the largest in the world with 161 centres in 108 countries (divided into 6 regions). This network is supported by multiple partners: a team of over 40 employees within IRCC’s IN-VAC, National Headquarters and approximately 350 Migration Officers in the field; 17 of which are Biometric VAC Officers (BVOs) based in IRCC offices abroad; Public Service and Procurement Canada (PSPC), the contracting authority responsible for managing the Contract; the International Industrial Security Directorate (IISD) of PSPC, the contracting security authority responsible for identifying and validating security and privacy requirements; and technical partners, Biometrics Operational Support Unit (BOSU) and IT Operations responsible for overseeing equipment and software and oversight of the biometrics enrolment process by BOSU.

Figure 1: Map of the world showing the countries that IN-VAC operates in

Text version: 2018 VAC Contract. VAC Network (countries) as of December 1, 2020

2018 Regions (Countries):

- Region 1 (Europe);

- Region 2 (Africa and the Middle East);

- Region 3 (the Americas);

- Region 4 (North Asia [China]);

- Region 5 (South Asia); and,

- Region 6 (Asia-Pacific)

- The VAC network is instrumental to the Government of Canada’s commitment to improving service to applicants and processing efficiency. It reduces the administrative burden on Migration Offices in directing client service and ensures application correctness and completeness prior to sending the files to IRCC offices for processing. This allows for Migration Offices to focus on processing and value added work; such as anti-fraud. In 2018, VACs accepted 1,790,754 work permits, student permits and temporary resident visa applications.

- IRCC began opening VACs in 2000. Most of these VACs were locally managed through Service Agreements with corresponding IRCC offices. On November 2, 2012, the Government of Canada awarded contracts to VFS Global and Computer Sciences Canada Inc. to operate standardized VACs throughout the world. Following a bid solicitation in 2017, VFS Global and TT Visa Services (TTS) were each awarded contracts by PSPC. The new 2018 Contracts were put in place on November 2, 2018 (Wave 1) for the Americas, Asia and Asia-Pacific and on November 2, 2019 (Wave 2) for Europe, Africa and the Middle East.

II. Audit objective, scope and methodology

Audit objective and scope

- The audit objective was to determine whether effective controls are in place for the management and oversight of VAC operations.

- Criteria were selected to evaluate the extent to which International Network – Visa Application Centre has met the audit objective. Three criteria were used to evaluate the audit objective:

- An effective VAC Contract oversight and governance structure has been established to provide ongoing support at a departmental level and roles, responsibilities and accountabilities of key players have been defined and communicated.

- Risk management processes are in place to manage risks related to the VAC network.

- Processes within IN-VAC have been implemented to monitor and assess VAC network service delivery and its compliance with contract requirements.

- The audit scope covered the time period from November 2018 to March 2020. The audit focused on risks to the management and oversight of VAC network operations. It examined governance, risk management and a selection of monitoring activities that support VAC network service delivery and compliance with contract requirements.

- The audit did not assess, the management of the Biometrics Project; the contracting process related to the 2012 and 2018 VAC Contracts; and the planning of the 2023 VAC Contract. Nor did it assess the responsibilities of PSPC and IISD.

Methodology

- The following audit procedures were performed:

- Interviews with key personnel at NHQ and abroad;

- Review of key supporting documentation such as; contracts, policies, meeting minutes, operational guides, training presentations etc.;

- Testing of a sample of monitoring activities; and

- Walkthroughs of Migration Offices, Visa Application Centres and/or Contact Centres abroad to observe processes in place (Mexico City, Bogota, New Delhi, Paris, Kiev and Addis Ababa).

- The audit observations, conclusions and recommendations are based on the work performed.

Statement of Conformance

- This audit was planned and conducted in conformance with the Institute of Internal Auditors International Professional Practices Framework, as supported by the results of a quality assurance and improvement program.

III. Audit findings and recommendations

Governance and Oversight

- An effective governance and oversight structure supports decision-making at the appropriate levels and by the appropriate parties. It provides employees and third party service providers with an understanding of responsibilities, priorities and performance targets towards the pursuit of IRCC’s commitment to improving services to applicants and processing efficiency and to ensuring objectives of the VAC Contract are met. We expected an effective and formalized governance structure for all those involved in the VAC network.

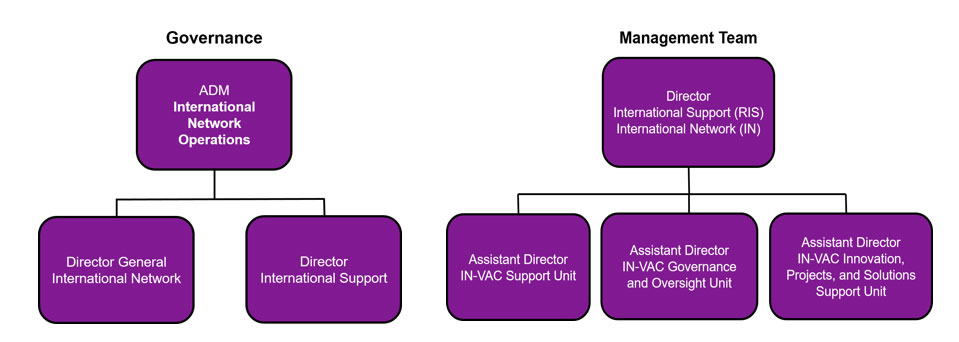

The current IN-VAC governance structure is comprised of: the ADM, International Network Operations; the Director General, International Network; and the Director, International Support. Reporting to the Director, International Support are three additional units making up NHQ’s IN-VAC team. They are: the Governance and Oversight Unit responsible for monitoring day-to-day operations of VACs including, performance management, site inspection coordination, issues management, contract and task authorization amendments and Business Continuity Planning; the Support Unit responsible for providing functional guidance to IRCC Offices, reviewing internal and external communications about VACs, reporting to senior management, conducting a review of the VAC network, and managing the MOU with US Citizenship and Immigration Services; and the Innovation Projects and Solutions Support Unit responsible for managing contract renewal, the initial VAC deployment at contract transition, major IT initiatives and projects, and liaising with partners on IT-related issues.

Figure 2: International Network Governance and IN-VAC Management Team Structure

Text version: International Network Governance and IN-VAC Management Team Structure

International Network Governance Structure:

- ADM, International Network Operations

- Director General, International Network

- Director, International Support

IN-VAC Management Team Structure:

- Director, International Support (RIS) and International Network (IN)

- Assistant Director, IN-VAC Support Unit

- Assistant Director, IN-VAC Governance and Oversight Unit

- Assistant Director, IN-VAC Innovation, Projects, and Solutions Support Unit

- ADM, International Network Operations

- The Director General Operations and Director of IN-VAC provide oversight of the management of the VAC Contract. The Director of IN-VAC receives a weekly status update regarding activities undertaken, major issues and priorities and the DG is briefed regularly on various issues affecting the network. The DG level committees include: the International Steering Committee, Client Experience Committee and the Corporate Finance Committee. Any high level risk issues are escalated up to the Deputy Minister level.

- An annual general meeting is held between all key stakeholders with responsibilities for management and oversight of the VAC Contract to discuss horizontal issues and risks. The participants include the Client Authority, IRCC IN-VAC; Contracting Authority, PSPC and PSPC-IISD; and the Contractor, VFS Global. Ongoing communication amongst internal and external partners allows IN-VAC to obtain timely information related to VAC management.

- A key position supporting IRCC offices abroad and VACs are the Biometric VAC Officers (BVO)Footnote 1. The BVOs are responsible for the oversight of VACs that report to IRCC offices in their territory and for providing biometrics support. As of May 2019, there were 17 BVOs in the network, each overseeing between 2 to 15 VACs. BVOs are responsible for reporting on performance activities designed to ensure consistent standards of service delivery and protection of personal information. They are expected to report regularly to IN-VAC on trends, concerns, issues, and reported incidents at all VACs in their region(s).

- As a result of the expansion of the biometrics requirement in 2018, a constant increase in application intake, and the implementation of new initiatives, such as digitization, the BVO’s role supporting the performance and reliability of the VAC network has continued to increase in scope and importance. For these reasons, the audit expected that the BVO role would be a full-time position. However, the majority of BVOs are also unit managers and supervisors. They manage a relationship with the Contractor, as well as, with the local VAC Manager(s). Additionally, a survey of BVOs revealed that two-thirds of them spend 20-50% of their time in the BVO role and focus much of their time on other VAC related responsibilities. The results of the survey, in addition to interviews conducted by the audit team, raise concerns regarding the capacity of the BVO role to execute all their responsibilities. An assessment of the BVO’s roles and responsibilities should be conducted to inform whether the role should be made full-time.

Conclusion:

- Overall, IN-VAC has a governance structure that is effective in providing monitoring and oversight for the VAC network. However, an assessment of the current complexities and competing priorities related to the BVO’s role and responsibilities should be conducted to inform whether the role should be made full-time.

Performance Monitoring and Reporting

- Effective monitoring and reporting processes support IN-VAC in ensuring that the Contractor remains compliant with the contract requirements. It allows for proactive reactions and adjustments to issues in order to support the continued delivery of quality service to clients while ensuring privacy and security. We expected processes within IN-VAC to have been implemented to monitor and assess VAC network service delivery and its compliance with contract requirements. Important components of the VAC Contract’s governance and oversight are monitoring and reporting on performance and adherence to the contract requirements and the 12 VAC Service Standards (VSS).

- Department contract management and oversight responsibilities were improved in 2018 by requiring the Contractor establish a governance structure for reporting at various levels of management and by incorporating the following three additional components: increased site visits; 12 targeted VSSs for which monthly reporting is done by the Contractor, Migration Offices (MOs) and BOSU; and increased corrective measures for non-compliance with service standards or contract requirements.

- In support of a stronger, more robust oversight program, IN-VAC has developed and implemented many activities and tools to support VAC performance monitoring and reporting. For instance there are: VAC Site Visits, Service Standards Monthly Reporting, Problem Identification Reports, and the Global Issues Tracker. These tools have been designed to ensure that VACs are meeting contract requirements and provide measurable data on various performance metrics across the VAC network.

- To assess whether processes and activities implemented monitor and assess the VAC network service delivery and its compliance with contract requirements, a judgmental sample of two activities were selected for further analysis. They are: VAC Service Standards Reporting and Site Visits.

- VAC Service Standards Reporting: To determine the Contractor’s compliance with the VSSs outlined within the contract, the Contractor or partners for each region (OPPB, MO, IN-Finance and BOSU) collect and submit Monthly Service Standard Reports (MSSRs) which provide measures against the 12 VSSs to IN-VAC. The VSSs cover biometric collection (quality threshold, procedural compliance and file association), biometric appointments (availability and timeliness), information services availability, GC Fees transmission timeliness, package transmission timeliness, package transmission and Contact Centre information services (average speed of answer for calls, webchats and emails). Based on compilation and analysis of the data provided, IN-VAC prepares a VAC Regional Performance Report (VRPR). The VRPR is provided to the Contractor and partners for follow-up within 5 business days, after which corrective measures may be issued.

- A review of 6 MSSRs from January 2019 to December 2019 demonstrated that overall, VSS Reporting is an effective mechanism for monitoring Contractor compliance with the 12 VSSs and applying corrective measures when applicable. However, there is concern from the Governance and Oversight team regarding IN-VAC’s ability to validate data being used to develop the MSSRs since data for 7 of the 12 VSSs are collected by and reside on systems owned by the Contractor. The current VAC Contract does not allow for IRCC to access these systems. As a result, IN-VAC cannot verify the accuracy and integrity of the data. With regards to future iterations of the VAC Contract, access rights to contract systems should be considered to support IRCC’s ability to validate the data submitted for reporting purposes. In the interim, additional controls should be considered to ensure consistent and valid data, such as requesting additional reports for cross-checking purposes.

- Site Visits: The Governance and Oversight Unit’s procedures describe site visits as being “one of the most effective methods of oversight ensuring that individual VACs perform well and have security and privacy measures in place.” IN-VAC’s Site Visits Portfolio is divided into four sections: Other Visits, Standard Visits, Comprehensive Visits and Contact Centre Visits; all of which are used for on-site VAC reviews.

- Other visits, varying in length, can be conducted by Senior Management, Government Officials or Migration Office Staff. They consist of Courtesy Visits which are typically for Senior Management/Government Officials who wish to visit a VAC and Follow up Visits which are used to follow up on a Comprehensive or Standard Site Visit that has recently taken place.

- Standard site visits, lasting two to three hours, are conducted as part of a BVO or VAC Liaison’s regular monitoring activities. They can also be conducted by: IN-VAC team members, IISD and PSPC. They involve the completion of a checklist used to evaluate more detailed aspects of VAC resources and services. These visits are conducted annually except in a year when a Comprehensive Visit has or will be taking place.

- Comprehensive site visits are the most extensive of VAC reviews and are to be conducted by the IN-VAC team, a BVO, a VAC Liaison, IISD and PSPC, or someone authorized by IN-VAC. They take between two to three days to complete and use a checklist that expands on other reviews to include verification of VAC documentation, plans/procedures, personnel files, a VAC manager interview and review of items that might have been previously identified. Comprehensive site visits are conducted at least twice during the lifetime of the Contract.

- Contact Centre site visits are similar to Comprehensive Visits. The reviews last for one day and can be conducted by the same parties as for the Comprehensive Visits. If a Comprehensive or Standard Visit is being done at a VAC location with an in-VAC Contact Centre, IN-VAC will require the reviewer to conduct a Contact Centre visit at the same time. These visits are typically conducted on an annual basis.

- The audit team participated in two Comprehensive Site Visits/Contact Centre Visits in February and March 2020, as well as, a Standard Site Visit in September 2019. Overall, observation of the site visits revealed that these are an effective monitoring activity and assess VAC network service delivery and its compliance with contract requirements. They allow for: follow-up on previously identified issues; input and suggestions from VAC staff on operations; and an opportunity to identify whether individuals at VACs are properly equipped to execute their responsibilities and if additional training is required. Comprehensive Checklists used during site visits allow for issues not previously identified by the Contractor to be brought to IN-VAC’s attention.

- A review of completed site visit checklists revealed that while they are being used to monitor compliance with contract requirements, the following opportunity for improvement should be considered:

- In an effort to keep them relevant and effective, checklists should be reviewed and updated regularly. For instance, leveraging information obtained from other monitoring activities or based on current events and adjusting the checklist accordingly i.e. decisions made as a result of COVID-19 are being tracked, newly developed procedures from IN-VAC NHQ have been implemented, fraud prevention protocols are in place, etc.

- Based on IN-VAC’s Internal Procedures for Planning and Reviewing Site Visits, “for VACs which will not be undergoing a Comprehensive Visit during a fiscal year, a Standard Visit will take place.” Based on the observation of the time it takes to conduct site visits and the reality that only qualified individuals can conduct these, consideration should be given to the following opportunity for improvement:

- As part of the scheduling exercise, site visits should be scheduled based on results from previous monitoring activities and needs. The resources and time allocated to a visit that has been scheduled for a site that has not had any issues or previous deficiency notifications would be better allocated to a VAC/Contact Centre known to have deficiencies or challenges.

Conclusion:

- IN-VAC has implemented processes to monitor and assess VAC network service delivery and its compliance with contract requirements. However, site visits should be scheduled based on results from previous monitoring activities and need. The resource and time allocated to a visit that has been scheduled for a site that has not had any issues or previous deficiency notifications would be better allocated to a VAC Contact Centre known to have deficiencies or challenges. In addition, with regards to future iterations of the VAC Contract, access rights to contractor systems should be considered to support IRCC’s ability to validate data submitted for reporting purposes.

Risk Management

- Risk management facilitates decision-making that is informed by an understanding of risks. It allows for a proactive response to threats and opportunities alike. Sound risk management is about supporting strategic decision-making that contributes to the achievement of an organization’s overall objectives. We expected risk management processes were in place to manage risks related to the VAC network.

- Overall, IN-VAC management and staff agree that risk awareness is an inherent part of the work being conducted in VACs. While IN-VAC does not have a formal risk management process in place, several monitoring and reporting activities being conducted by BVOs, Migration Officers and the VAC Contractor provide insight into potential risks, opportunities and trends and resulting discussions support the development and implementation of mitigation strategies. Activities such as: announced and unannounced site visits; BVO monthly teleconferences; Problem Identification Reports; the Global Issues Tracker; and quality assurance reports not only monitor compliance with service standards and contract requirements, but also result in the identification and mitigation of existing and potential risks.

- A review of the Problem Identification Report and the Global Issues Tracker demonstrated that risk management activities are taking place as a result of these monitoring and reporting tools. Specifically, as problems and incidents arise that may impact the Contractor’s ability to adhere to the terms of the Contract, IN-VAC and IISD must be made aware via the PIR. The PIR identifies the problem, provides an impact assessment, a remedial action plan and a mitigation plan, all risk management activities. The risks along with all other issues are then documented and tracked within the Global Issues Tracker.

- In addition, a review of BVO monthly teleconferences from December 2018 to March 2020 revealed that: during 3 of the 4 calls, risk management issues that were raised led to informal discussions regarding possible solutions or interim measures and impacts; and fraud related issues were discussed during 2 of the calls. Finally, while these teleconferences and resulting discussions and solutions are a valuable source of information supporting risk management, documenting these discussions and more importantly the decisions taken to address issues is important not only to support decisions taken but also to monitor the results of those decisions (including the ability to make changes if needed).

Conclusion:

- IN-VAC does not have a risk management process in place to manage risks related to the VAC network. However, several monitoring and reporting activities have been implemented that have been shown to inform and support risk management. Developing and implementing a formal risk management process to identify, assess and treat VAC related risks will better support the achievement of the IRCC’s VAC network objectives.

Recommendation 1: The Assistant Deputy Minister, Operations Sector should assess the BVO’s role to ensure they have the capacity to provide their relationship management responsibilities to the VACs.

Management response: Management agrees with this recommendation.

Management recognizes the importance of a solid, high-functioning and reliable VAC network in order to support the Department’s immigration programs and initiatives. As such, Management is committed to reviewing the BVO’s role in order to ensure they have the capacity to conduct all of their responsibilities, including the oversight of the relationship with the local VAC contractor.

Recommendation 2: The Assistant Deputy Minister, Operations Sector, should identify and implement mechanisms that will allow IN-VAC to validate data submitted for reporting.

Management response: IRCC management agrees with this recommendation.

The VAC Contract should give consideration to providing IRCC with access rights to contractor systems or raw data to facilitate IN’s ability to validate data submitted for reporting purposes.

A request for similar access to the Contractors’ systems to allow for the verification of data submitted in VAC Service Standard (VSS) reporting was proposed during preliminary work for the current VAC Contract (2017), but was not included following IRCC Legal Services’ advice about this stepping over the line and effectively create (or appearance of creating) an “agency relationship” between the Contractor and the Government of Canada. IRCC Legal Services’ opinion was accepted, and IN in collaboration with the Contract owner, Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) agreed that this was an acceptable limitation of working with a 3rd party who was considered as a “trusted resource”.

In lieu of access to the Contractors’ systems to validate VSS data, the Contractor was instructed to submit raw data for the set VAC Service Standards, and that IN would be responsible for using in-house created tools (excel spreadsheet) to verify the quality of the data and to confirm if the VAC met or failed the individual service standards. Both items have been put in place since the beginning of the current contact in 2018.

Until such time that an automated tool mechanism is created to validate that the data was not tampered with by the Contractor before being submitted to IRCC, we will determine what alternative methods are available that would allow us to have greater trust in the validity and quality of the Contractors’ VSS data.

Preliminary work is being conducted on the next iteration of the VAC Contract (2023). IN is currently conducting Contractor Engagement meetings where several potential service providers (industry leaders) have been asked to provide IRCC with information on what a VAC of the future should include in the way of services, as well as potential solutions for monitoring and reporting on service levels at VACs. This also includes methods for allowing IRCC to validate the quality of any data submitted by future Contractors.

IV. Conclusion

- Overall, the audit found that IN-VAC has effective controls in place for the management and oversight of VAC operations. However, the following actions are suggested in support of continuous improvement:

- An assessment of the current complexities and competing priorities related to the BVO’s role and responsibilities should be conducted to inform whether the role should be made full-time.

- Future iterations of the VAC Contract should give consideration to providing IRCC with access rights to contractor systems or raw data to facilitate IN-VAC’s ability to validate data submitted for reporting purposes.

Management has accepted the audit findings and developed an action plan to address the recommendations.