ARCHIVED – Evaluation of the International Experience Canada Program

Research and Evaluation Branch

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

January 2019

Ci4-190/2019E-PDF

978-0-660-30154-9

Reference Number: E2-2017

Download:

Table of Contents

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Evaluation of the IEC Program: Management Response Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Relevance

- 4. Performance – Program Effectiveness

- 5. Performance – Resource Utilization

- 6. Conclusions and Recommendations

- Annex A: Youth Mobility Agreement Country List

- Annex B: Profile of IEC Foreign Youth Participants

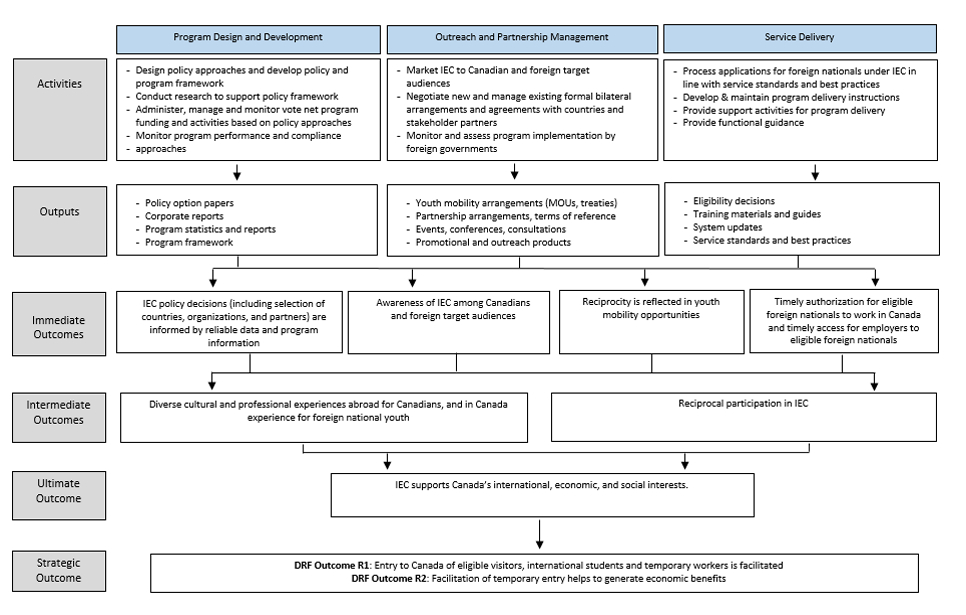

- Annex C: Logic Model for the International Experience Canada Program (August 2017)

- Annex D: Evaluation Questions

- Annex E: IEC Reciprocity – Quotas, Participants and Ratios (2007, 2013 and 2017)

- Annex F: CEEDD

- Annex G: Resource Management Tables and Figures

List of Figures

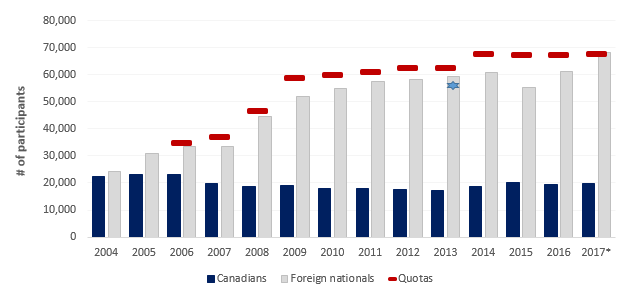

- Figure 1: Trends in IEC Program Quotas and Number of Canadian and Foreign Youth Participants, 2004 to 2017

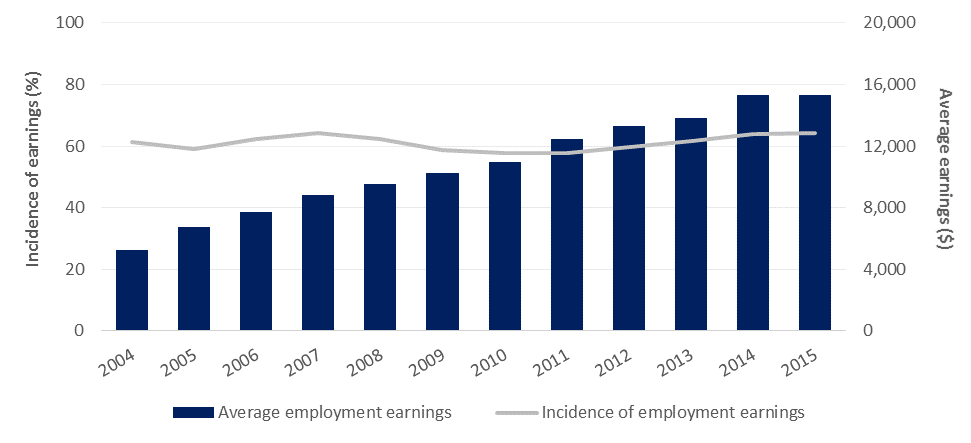

- Figure 2: Incidence and Average Employment Earnings of IEC Foreign Youth Participants, 2004 to 2015

- Figure 3: IRCC and OGDs Share of Total IEC Program Costs, FY 2013-14 to 2016-17

List of Tables

- Table 1: IEC Youth Participation - Canadian and Foreign Youth

- Table 2: Lines of Evidence

- Table 3: IEC Reciprocity Ratios (2007, 2013, and 2017)

- Table 4: Sector Distribution of IEC Participants with Employment Earnings, CEEDD

- Table 5: Service Standard Adherence (56 days) for IEC Work Permit Applications Processed, by Year and IEC Stream

- Table 6: Total IEC Program Costs* (IRCC and OGDs), FY 2013-14 to 2016-17

- Table 7: Total IEC Program FTEs (by Sector), FY 2013-14 to 2016-17

- Table 8: IEC Program Costs and Revenues, FY 2013-14 to 2016-17

- Table 9: Costs per Processed Application (Total IRCC and OGD Costs), FY 2013-14 to 2016-17

Acronyms

- CBSA

- Canada Border Services Agency

- CEEDD

- Canadian Employee-Employer Dynamics Database

- CFP

- Call for Proposals

- CMM

- Cost Management Model

- Co-op

- International Co-op Internship Program

- ESDC

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- FTE

- Full-time Equivalent

- FY

- Fiscal Year

- GAC

- Global Affairs Canada

- GCMS

- Global Case Management System

- IEC

- International Experience Canada

- IMP

- International Mobility Program

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- IRPA

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- IRPR

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations

- ITA

- Invitation to Apply

- LMIA

- Labour Market Impact Assessment

- LOI

- Letter of Introduction

- MOU

- Memorandum of Understanding

- OGD

- Other Government Department

- PCH

- Department of Canadian Heritage

- RO

- Recognized Organization

- TR

- Temporary Resident/Temporary Residence

- WHP

- Working Holiday Program

- YMA

- Youth Mobility Agreement and Arrangements

- YPP

- Young Professional Program

Executive Summary

The evaluation of the International Experience Canada (IEC) Program was conducted in fulfilment of requirements of the Treasury Board 2016 Policy on Results. The evaluation covered the period since the program’s transfer from Global Affairs Canada (GAC) to Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) (FY 2013-14 to FY 2017-18).

Evaluation Findings

Relevance

Overall, there is a continued need for a youth mobility program and the IEC Program has effectively facilitated cultural and employment experiences of participants while also providing important international bilateral benefits at the federal government level.

Further, the evaluation found that the program is aligned with Government of Canada priorities, particularly given the current focus on youth, and also with IRCC’s mandate and priorities, mainly with regard to facilitating the entry of foreign nationals. As the program intersects a number of themes related to immigration, employment, culture, international relations and youth, the IEC also aligns with the mandates of other government departments, including GAC, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), Canadian Heritage (PCH), and the Prime Minister’s Youth Secretariat.

Performance – Effectiveness

Reciprocity

Youth Mobility Agreements (YMA) signed between Canada and partner countries are designed to be reciprocal both in terms of quotas (i.e., the number of program participants) and opportunities offered, as required under Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (paragraph 205(b)) which forms the basis of the Labour Market Impact Assessment (LMIA) exemption for open work permits issued through IEC.

Despite reciprocity’s central role in the design of YMAs, reciprocity in program participation has been a major challenge over the last several years, as demonstrated by the significantly greater number of foreign youth participating in the program annually than Canadian youth. Evidence points to some quota management decisions that have contributed to this reciprocal disparity, including attempts made to limit the increase of country-specific quotas and the expansion of YMAs to new countries despite low Canadian participation over the last 10 years. Further, other factors were found to be potentially limiting Canadian participation, such as the onerous program application requirements of other countries and economic conditions abroad (e.g., minimum wages and youth unemployment rates in YMA countries).

Awareness of IEC Program

To increase Canadian awareness of and participation in the program, IEC has conducted various promotional activities mainly focusing on Canadian youth and, more recently, on “youth influencers”. While promotional activities are relatively new, and it will take a few more years before noticing changes in awareness behaviour, Canadian youth awareness of and participation in the program have remained relatively low thus far.

Cultural and Professional Experiences

Findings showed that foreign and Canadian youth have gained various cultural and professional experiences as a result of their participation in the IEC program. The most common cultural experiences identified by foreign and Canadian youth included: visiting cultural sites, participating in cultural activities, and developing friendships. In terms of key cultural benefits gained from IEC program participation, foreign and Canadian youth reported learning about a new country or culture, gaining international experience that contributed to their personal growth, and taking part in explorations and adventures.

Further, both foreign and Canadian youth participants have gained professional experiences during their time abroad as part of the IEC Program. Recent data showed a high incidence of employment among foreign youth participants in Canada and that their average employment earnings have been steadily increasing. Obtaining international career experience and professional development was also identified by many foreign and Canadian youth as a key benefit of their participation.

Supporting Canada’s International, Economic and Social Interests

Overall, the IEC Program is supporting Canada’s social, international and economic interests. From a social perspective, international experiences increase youth awareness and understanding of other cultures and evidence also points to the program being key to supporting Canada’s international interests, acting as a tool in bilateral relations with other countries. Moreover, a small portion of IEC foreign youth who came to Canada under the IEC Program between 2013 and 2017 transitioned to permanent residence, further enriching Canada’s diversity.

From an economic standpoint, the program provides a potential pool of temporary workers and also contributes to the tourism industry in Canada.

Given that the number of foreign youth participants in the program considerably outnumber their Canadian counterparts (on average 3:1 annually over the last five years), there may be potential for displacement within the Canadian labour market. However, the evaluation did not find conclusive evidence that displacement has occurred, pointing to the need for additional advanced research to assess IEC’s full impact on the Canadian labour market.

Program Delivery and Integrity

There were no major challenges associated with program delivery and overall, roles and responsibilities of program groups within IRCC, as well as between IRCC and other government departments (OGD) are clear and understood. Moreover, communication and coordination between program groups within IRCC and between IRCC and OGDs has been effective. However, the evaluation did find that there is a need to clarify the roles and responsibilities of the Recognized Organizations (ROs) as well as to improve communication between IRCC and ROs, mainly with respect to governance and oversight. As of October 2018, the Department negotiated new MOUs with ROs and assigned new resources to address these issues.

IRCC generally processed IEC applications within prescribed service standards during the period covered by the evaluation. Further, the program has implemented quality assurance mechanisms; no major program integrity issues were identified.

Resource Utilization

IEC Program resources have increased over the recent years, though IRCC’s share of overall program costs has decreased (relative to other government departments) and have been offset by increasing revenues.

Conclusions and Recommendations

The IEC Program is aligned with departmental priorities and has contributed to the achievement of several expected program outcomes, namely the timely entry of foreign youth, providing cultural and professional experiences for participants, and supporting Canada’s international, social and economic interests. However, the evaluation found several areas for improvement in the program:

- the management of reciprocity;

- the limited awareness of the program and its benefits among Canadian youth, affecting program uptake;

- the need to conduct further research into program impacts on the Canadian labour market; and

- the lack of program monitoring and data collection on Canadian youth travelling abroad as part of IEC.

As a result, the following recommendations were developed to address these issues:

Recommendation 1: IRCC should reconfirm and clearly articulate the focus of the IEC Program, specifically in relation to:

- the program mandate and expected outcomes; and

- the policy translation and implementation of the reciprocity principle.

Recommendation 2: IRCC should enhance the promotion of the IEC Program to Canadian youth, with the aim of increasing their awareness of the benefits the program offers, and their participation in the program.

Recommendation 3: To support the monitoring of program outcomes related to Canadian youth going abroad, IRCC should establish effective data collection and management strategies.

Recommendation 4: IRCC should undertake in-depth research to further assess the full impact of the IEC Program on the Canadian labour market.

Evaluation of the International Experience Canada Program - Management Response Action Plan

Recommendations

Recommendation 1

IRCC should reconfirm and clearly articulate the focus of the IEC Program, specifically in relation to:

- The program mandate and expected outcomes; and

- The policy translation and implementation of the reciprocity principle

Response

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

International Experience Canada has a number of competing bilateral, economic, and cultural objectives that are often, but not always, complementary. Depending on the broader bilateral context and constraints imposed by partner countries, different arrangements prioritize different objectives.

In many instances, an imperfect arrangement is preferable to no arrangement.

Action

- Develop a strategic framework that includes: defining reciprocity; confirming expected results, determining how to balance core program objectives against broader Government of Canada objectives; articulating the overall net benefit for Canada, Canadian youth and other Departmental objectives.

- Accountability

- Lead: IEC – Immigration Branch

- Completion Date: Q2 2019/2020

- Accountability

- Secure approval of strategic framework from senior management.

- Accountability

- Lead: IEC – Immigration Branch

- Completion Date: Q3 2019/2020

- Accountability

Recommendation 2

IRCC should enhance the promotion of the IEC Program to Canadian youth, with the aim of increasing their awareness of the benefits the program offers, and their participation in the program.

Response

IRCC agrees with the recommendation.

While the evaluation confirms that Canadian participation is low in comparison to the number of foreign youth who come to Canada, there has been an increase of Canadian participants in IEC of 16% since the program was transferred to IRCC in 2013.

The Department agrees that the IEC program can enhance its awareness; noting however, that a large part of this promotional and advertising work is restricted to activities allowable within the current program constraints and Government of Canada advertising limitations.

Engagement with Central Agencies, various stakeholder groups, and existing networks will be key to enhancing and expanding promotional reach for the program. Part of the efforts will focus on Canadian youth to ensure they have the information needed to participate in the IEC program.

Much of this work will be based on social marketing and developing actions that will result in a long-term behavioural change and may take several years to unfold and see results.

Action

- Complete an annual review and updating of marketing, promotional and partnership strategies to ensure continued alignment with IEC, IRCC and GoC priorities.

- Accountability

- Lead: IEC – Immigration Branch

- Completion Date: Q1 2019/2020

- Accountability

- Consult with Central Agencies to seek approvals to implement other advertising mechanisms that would target not only youth directly, but their influencers.

- Accountability

- Lead: IEC – Immigration Branch

- Support: Communications Branch

- Completion Date: Q4 2019/2020

- Accountability

- Develop and implement promotional projects with stakeholder groups (including Recognized Organizations) to leverage existing communication networks.

- Accountability

- Lead: IEC – Immigration Branch

- Support: Communications Branch

- Completion Date: Q4 2019/2020 and onward

- Accountability

- Develop and implement inclusive promotional strategies, in consultation with key stakeholders, that target Canadian youth in communities of interest (e.g. Indigenous youth, LGBTQ2 youth, youth with disabilities) to ensure that all youth are aware of the opportunities available through IEC.

- Accountability

- Lead: IEC – Immigration Branch

- Support: Communications Branch

- Completion Date: Q4 2019/2020 and onward

- Accountability

Recommendation 3

To support the monitoring of program outcomes related to Canadian youth going abroad, IRCC should establish effective data collection and management strategies.

Response

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

The IEC program is positioned well with respect to administrative data on foreign nationals coming to Canada. All aspects of application, decision-making, and day-to-day reporting and tools needed for the effective and efficient running of the program are in place and are used effectively.

However, there is limited and inconsistent data currently available on Canadians who go abroad under reciprocal Youth Mobility Arrangements. Having better information/data on Canadian youth is vital to track the performance and the benefits of the program. Reliable data on Canadian youth is also essential for evidence-based research to inform policy development, country negotiations, promotional activities and future IEC program evaluations.

While some data on Canadian youth who travel abroad under youth mobility arrangements is currently obtained annually through IEC partner countries via data exchange clauses/annexes within country arrangements, challenges persist in obtaining more fulsome data on this group.

Action

- Explore options (including participant registration and surveys) to capture more robust socio-demographic data and contact information on Canadian youth and IEC participants, to generate program relevant results data. All options will take into consideration privacy and legal legislations as well as administrative processes.

- Accountability

- Lead: IEC – Immigration Branch

- Completion Date: Q2 2019/2020

- Accountability

- Develop and launch a survey to Canadian youth participants (through public opinion research, alumni networks and collaboration with top receiving partner countries).

- Accountability

- Lead: IEC – Immigration Branch

- Completion Date: Q4 2019/2020

- Accountability

Recommendation 4

IRCC should undertake in-depth research to further assess the full impact of the IEC Program on the Canadian labour market.

Response

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

The Department recognizes the need to more fully understand the impact of the IEC program on the Canadian labour market. In order for in-depth research to be undertaken, the Department must ensure the availability of the necessary Labour Market Information (LMI) - data gaps persist, particularly at the local level, which is not unique to the IEC program. The work to improve the LMI is currently underway at IRCC, and will include (i) FTE measures (ii) employment rates and wage information by industry/occupation (iii) regional and international unemployment rates.

The LMI work will be supplemented by additional research into the temporary resident stream to determine the overall impact of IEC participants on the Canadian labour market.

Action

- Complete three research projects focusing on labour market outcomes of youth and IEC participants as outlined in the 2018/19 IEC Research Plan.

- Accountability

- Lead: IEC – Immigration Branch

- Completion Date: Q3 2019/2020

- Accountability

- Develop key indicators for determining labour market impact and develop data collection methods.

- Accountability

- Lead: IEC – Immigration Branch

- Support: SPP and R&E

- Completion Date: Q4 2019/2020

- Accountability

- Complete a research project to investigate the labour market impact of temporary workers, with a focus on the IEC program.

- Accountability

- Lead: R&E

- Completion Date: Q4 2019/2020 and onward

- Accountability

1. Introduction

1.1. Purpose of the Evaluation

The evaluation of the International Experience Canada (IEC) Program was conducted in fulfilment of requirements of the Treasury Board 2016 Policy on Results. The evaluation was conducted by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) to assess the program relevance, performance and outcomes of the program. The evaluation examined both the foreign and Canadian youth components of the program and covered the fiscal years (FY) 2013-14 – 2017-18.

This evaluation focused on the outcomes for IEC youth participants, particularly for foreign nationals. The evaluation also examined program success in raising awareness about the IEC. In addition, recognizing that the IEC Program has not been evaluated since its transfer to IRCC in 2013, one of the areas of focus for the evaluation was to assess the management of the program.

1.2. Program Profile

Since the introduction of the IEC Program in 1951, the Canadian government encouraged travel and exchange programs designed to help Canadian youth understand better their place and role at the international level. As such, the IEC Program promotes and facilitates travel and work exchange opportunities for Canadians and foreign youth by negotiating bilateral, reciprocal agreements and arrangements with other countries. IEC’s current mandate includes activities in the following areasFootnote 1:

- Fostering people-to-people ties and strengthening relationships between Canada and its partner countries;

- Helping build a competitive global workforce that contributes to Canada’s economic success; and,

- Providing youth with the opportunity to broaden their perspective on the world and Canada’s place in it through international travel and work experience.

The IEC Program is part of IRCC’s International Mobility Program (IMP), which issues work permits that are exempt from Labour Market Impact Assessments (LMIA). In 2016, 22% of Temporary Workers Program work permits were issued to IEC foreign youthFootnote 2, making the IEC Program the largest component of the IMP.

1.2.1. Program Design

The design of the program is structured around bilateral reciprocal youth mobility agreements and arrangements (YMA), which are negotiated between Canada and foreign countries. The IEC Program facilitates the participation of youth. Currently, Canada has 34 such agreements with foreign countries (see Annex A for the Youth Mobility Agreement Country List). YMAs typically include one or more of the following three categories for participation in the program:

- Working Holiday (WHP): participating youth obtain an open work permit which allows them to work anywhere in the host country.

- Young Professionals (YPP): participating youth obtain an employer-specific work permit if they have a job offer that contributes to their professional development related to their field of study and work for the same employer for the duration of their stay.

- International Co-op Internship (Co-op): participating youth obtain an employer-specific work permit if they are enrolled in a post-secondary institution, have a job offer that is related to their field of study, and work for the same employer for the duration of their stay.

While eligibility requirements may vary somewhat for each agreement, participation in the program is typically open to Canadian and foreign youth aged 18 to 35. Given that IEC YMAs are reciprocal in nature, foreign youth participants in the program are exempt from LMIA requirements, in accordance with Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and Regulations.Footnote 3

IRCC negotiates individual quotas with each YMA country every year and identifies an IEC global quota. The global quota set each year represents the maximum planned number of participants coming to Canada and going abroad. In 2014, IRCC set an objective of welcoming two foreign youth IEC participants to Canada for every Canadian youth IEC participant going abroad (i.e., a 2:1 ratio). For most countries, the quota has remained the same since the program’s transfer to IRCC.

1.2.2. Program Delivery

For Canadian youth participating in IEC, an application must be submitted to the country of interest and follow the appropriate immigration steps. All countries have different processes (online application vs. in-person), and requirements (e.g., police record checks) that are not within the control of the IEC Program.

IRCC controls the delivery of the IEC Program to foreign youth, which is done through an online application. To start the IEC application process, foreign youth are required to create and submit an online profile through an IRCC personal account. Once their profile has been submitted, pools of eligible candidates for each country and each IEC category are created. Candidate selection is done randomly, through a lottery-based system. Selected candidates receive an Invitation to Apply (ITA). If they accept the ITA, candidates are then required to submit a work permit application. If their application is approved, they are issued a Letter of Introduction (LOI), which is presented to a border services officer at the port of entry upon their arrival to Canada.

The IEC Program is run on a cost-recovery basis under a net voting authority, which allows the program to charge a user fee to participants and to spend generated revenues on program-related expenditures. As part of the 2018 IEC season, IEC participants were required to pay a fee of $150 as part of their application. Further, employers are required to pay a $230 compliance fee if they hire a foreign youth under the Young Professional Program or International Co-op Internship categories, and Working Holiday Program participants are required to pay a $100 open work permit fee.

Recognized Organizations

The IEC Program also manages memorandums of understanding (MOU) with third-party Canadian organizations, known as Recognized Organizations (RO), that provide services to facilitate international travel and work opportunities for Canadian and foreign youth under the IEC Program. ROs provide a variety of services, which can include support and advice to youth throughout the application process, assistance with travel arrangements and/or arranging work placements. Typically, ROs will provide their services for a fee, which is set by each organization.

Foreign youth applying via a RO use overall the same application process as other candidates applying via country quotas. The notable difference is that after candidates create and submit an online profile through an IRCC personal account, ROs submit a list of names to IRCC. IRCC will validate the candidates profile and send the candidate an ITA.

As outlined in the signed MOU between ROs and IRCC, ROs are expected to contribute to the following:

- Reciprocal participation between foreign and Canadian youth;

- Increase program awareness and promote international travel, work and career-related opportunities through IEC to diverse groups of Canadians; and

- Equip Canadian youth with the resources for traveling and working abroad under IEC so that these opportunities are accessible to all Canadians.

In 2015, IRCC selected a total of 12 organizations as part of a call for proposal (CFP) process for RO designation. MOUs with selected ROs were signed in early 2016 and expired in the Summer of 2018. As a result, the program launched and recently completed a CFP process, with new MOUs in place for the 2019 IEC season.

1.2.3. Financial and Human Resources

This section provides a brief overview of the resources related to the delivery and support of the IEC Program. A total of 113 full-time equivalents (FTE) were devoted to the IEC Program within IRCC in 2016-17, 76 FTEs were in the Operations Sector while 37 FTEs were in the Strategic and Program Policy Sector or Other Sectors. For the same fiscal year, the total cost (IRCC and other government departments) to deliver the IEC Program was $21.39M and IRCC’s total cost to deliver IEC was $12.79M, while other government departments (OGD) costs were at $8.6M. This cost was partially offset by revenues generated by the program, which reached a total of about $10.02M.

1.3. Characteristics of IEC Youth

Table 1 provides the annual global quota or planned target for both the outgoing and incoming portion of the program and provides the actual number of approved participants. Between 2013 and 2017, there was a total of 94,634 Canadian youth work permit holders and 252,712 foreign youth participantsFootnote 4 in the IEC Program. The subsequent sections provide a profile of each of those two groups.

Table 1: IEC Youth Participation - Canadian and Foreign Youth

| Year | Official Global Quota | Outgoing Canadian Youth Work Permit Holders | Incoming Foreign Youth Participants |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 62,305 | 17,122 | 48,629 |

| 2014 | 67,655 | 18,699 | 44,767 |

| 2015 | 67,305 | 20,119 | 44,985 |

| 2016 | 69,385 | 19,371 | 51,453 |

| 2017 | 67,330 | 19,323 | 62,878 |

| Total | N/A | 94,634 | 252,712 |

Source: Immigration Branch, August 2018.

1.3.1. Profile of IEC Foreign Youth Participants (2013-2017)

The following characteristics were observed among foreign youth participants:

- Stream: 81% of the foreign youth participants were admitted under the Working Holiday stream, while about 9% were admitted under the Co-op stream, and 6% under the Young Professional stream.

- Frequency of participation: 92% of individuals who came to Canada under the IEC received only one work permit; 8% had more than one IEC experience in Canada. Participants under the Young Professionals stream represented the largest proportion of those who used the program more than once, with over one third (35%) having received more than one work permit under IEC.

- Age: Most (77%) foreign youth admitted to Canada under the IEC were between 21 and 29 years old when they started their IEC experience. Participants under the Young Professionals stream were slightly older, with a greater share (21%) falling under the 30 to 35 age group. Foreign youth participants from the Co-op stream were slightly younger than the other streams, with a greater share in the 18 to 20 age group (19%).

- Gender: Half of IEC foreign youth participants were women. While women accounted for half of all participants under the Working Holiday stream and 53% for the Co-op stream, they only accounted for 40% of those from the Young Professionals stream.

- Citizenship: The top five countries of citizenship for foreign youth admitted under IEC were: France (21%), Australia (15%), Japan (11%), Ireland (9%) and Germany (8%). While countries of citizenship of foreign youth were more diverse for the Working Holiday stream, the majority of participants under the Co-op stream (86%) and the Young Professionals (58%) came from France.

- Knowledge of official languages: The majority of IEC foreign youth participants were able to communicate in one of Canada’s official languages: 71% indicated knowing English only, 22% French only, and 1% both French and English. Reflecting the country composition of the IEC streams, most participants from the Working Holiday stream indicated being able to communicate in English only, while 85% of those under the Co-op stream and 54% of those under the Young Professional stream indicated being able to communicate in French only.

For more information on the profile of IEC foreign youth participants, see Annex B.

1.3.2. Profile of IEC Canadian Youth Participants

While IRCC has comprehensive information on foreign youth coming to Canada under the IEC Program (as the department is responsible for the processing of foreign youth IEC applications), IRCC has limited information on Canadian youth participants travelling abroad through the program as the programs are administered by foreign governments and Canadians do not apply through the Government of Canada. The only information available on Canadian youth participating in the IEC is the annual number who traveled to each YMA country, which is provided to IRCC on an annual basis.Footnote 5

Between 2013 and 2017, 94,634 Canadians travelled abroad through IEC, representing between 17,000 and 20,000 individuals each year. Most (87%) Canadians either travelled to Australia (40%), the United Kingdom (20%), France (12%), New Zealand (12%) or Germany (3%) through the IEC Program.

2. Methodology

2.1. Questions and Scope

The evaluation scope and approach were determined during the planning phase, in consultation with IRCC branches involved in the design, management and delivery of the IEC Program as well as Global Affairs Canada (GAC). The evaluation assessed issues of relevance and performance and covered the period of FY 2013-14 to 2017-18. The evaluation was also guided by the program logic model, which outlines the expected immediate and intermediate outcomes for the program (see Annex C).

The evaluation was conducted internally by IRCC’s Evaluation Division. The evaluation questions are presented in Annex D.

2.2. Data Collection Methods

Data collection and analysis for this evaluation took place from October 2017 to September 2018 and included multiple lines of evidence that gathered qualitative and quantitative data from a wide range of perspectives, including IRCC, GAC, ROs and IEC participants. The different lines of evidence supporting the evaluation are described in Table 2.

Table 2: Lines of Evidence

Lines of evidence and description

| Document Review | Relevant program documents were reviewed to gather background and context on the IEC Program, as well as to assess its relevance and performance. Documents reviewed include: IRCC documentation, international reports, stakeholder documents, promotional materials, academic literature, etc. |

|---|---|

| Interviews | 33 interviews were conducted with a total of 46 representatives from various stakeholder groups. Internal IRCC groups consulted include: Senior management (3); Immigration Branch (8); Immigration Program Guidance Branch (3); International Network (1); Centralized Network (3); International and Intergovernmental Relations (2); and, Communications Branch (2). External groups consulted include: GAC (8); Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) (1); Recognized Organizations (4); foreign governments (7); and, education organizations and academic institutions (4). |

| Site visit to Centralized Network (OSC) | A site visit to IRCC Operations Support Centre within Centralized Network was conducted to examine how IEC applications are processed. This included interviews with key informants, a review of the IEC application process and file review. |

| RO survey | An online survey of ROs was conducted in March 2018. An email invitation to complete the survey was sent to all organizations designated under the IEC Program; all 12 ROs responded to the survey. |

| Foreign youth survey | An online survey was administered to a sample of 24,000 foreign youth who participated in the IEC Program between 2013 and 2017. A total of 3,408 foreign youth completed the survey, for an overall response rate of 14.2%. Results were weighted to reflect the stream composition of the IEC. The overall margin of error for this survey is ± 1.66%, using a confidence interval of 95%. |

| Canadian survey | An online survey was administered to a sample of 3,328 among the 9,345 Canadian youth who travelled to New Zealand through the IEC program between 2013 and 2017. A total of 708 Canadian participants completed the survey, for an overall response rate of 20.2%. Although survey results may serve as an indication of experiences of Canadian youth who travelled to New Zealand, this survey was exploratory in nature and only conducted in one of the countries with which Canada has a YMA. As such, survey results are not meant to be representative of the Canadian youth population travelling abroad as part of the IEC. |

| Program Data Analysis | Available performance data and financial data from IRCC’s Global Case Management System (GCMS), Canadian Employee-Employer Dynamics Database (CEEDD) and IRCC’s Cost Management Model (CMM) were collected and used to provide profile, performance and financial information on the program. |

2.3. Limitations and Considerations

Limitations were noted for the evaluation, in particular, surrounding a lack of information about Canadian participants. As the Canadian youth components are administered by foreign governments, IRCC does not have administrative data nor contact information with regards to Canadian participants. About half of the countries, with which Canada has a YMA, have an explicit clause on information sharing, and IRCC has developed model MOUs and treaty which highlights requirements on information sharing that should be applied to all new YMAs being signed. However, information sharing provisions in YMAs are limited to the annual number of Canadian youth who travelled to each YMA country.Footnote 6 As such, IRCC does not receive any information from YMA countries about the different experiences of Canadian youth abroad, nor does have a mean to obtain such information. The limited nature of the information IRCC has on Canadian participants hinders the department’s ability to fully assess outcomes of Canadians participating in the program, including type of activities undertaken while abroad, benefits gained and challenges experienced by participants.

As a result, the evaluation was not able to provide a profile of Canadian youth participants, and was not able to conduct a comprehensive survey to assess the diverse cultural and professional experiences of Canadian youth and barriers issues they could have faced.

While it was not possible to survey a representative group of Canadians youth who went abroad as part of the IEC Program, mitigation for this was made in the form of an exploratory survey with New Zealand. The survey was not intended to be representative of the population who went abroad, but to provide some insight into the outcomes and experiences of the Canadian youth who went to New Zealand.

Nevertheless, the overall evaluation design employed numerous qualitative and quantitative methodologies that were complementary and rigorous yielding of results that can be used with confidence.

3. Relevance

3.1. Continued Need for the IEC Program

In 1951, the IEC ProgramFootnote 7 began as a reciprocal short-term labour exchange for 18 to 30 year olds, to respond to the need of helping Canadians better understand their place and role in international society. To do so, a government intervention was required to facilitate the entry and work experience of IEC participants to Canada.

Finding: Overall, there is a continued need for a youth mobility program. While the facilitation of cultural and employment experiences is an essential benefit of the program, IEC also provides additional longer-term international bilateral benefits at the federal government level.

The need for the program was reiterated by key informants. A majority of interviewees across all respondent groups agreed that there is a continued need for Canada to have a youth mobility program to enable youth to travel abroad and gain cultural awareness, professional experience and improved skills. Some interviewees did not perceive a strong need for the program, with a few indicating did not see the need to have agreements with certain countries and a few others noting that in the absence of the IEC Program, youth would find other ways to work while travelling abroad.

While the fostering of close bilateral relations between Canada and other countries has been highlighted by documents and interviewees as an important element of the program, bilateral relations are not specified as an outcome in the IEC Program’s logic model. As such, the reciprocal cultural and employment experiences fill a shorter-term program need, while the fostering of bilateral relations fill a longer-term program need.

3.2. Alignment with Departmental and Government Priorities

Finding: The IEC Program is well aligned with Government of Canada priorities and with IRCC’s priorities and mandate regarding facilitation of entry of foreign nationals into Canada, while also contributing to the mandates of other government departments.

Most interviewees agreed that the IEC Program aligns with Government of Canada priorities, as the youth portfolio is an important focus for the current government and Prime Minister, and as such there has been an increased attempt to help young Canadians gain valuable work and life experience.Footnote 8

The IEC Program was transferred to IRCC in 2013 with the intention of aligning the program with government priorities and the labour market demands in Canada, as well as by linking the IEC Program to the other immigration programs. The intention of the transfer was to “strengthen Canada’s strategy to develop its human capital and attract talent.”Footnote 9

In addition, IEC’s current mandate states that the program is to “enhance key bilateral relationships between Canada and other countries and emphasize the importance of improved reciprocity”.Footnote 10 IRCC’s contribution to this mandate is through the processing of applications from high-quality participants who fit Canada’s immigration priorities.

Overall, interviewees agreed that the IEC Program is in alignment with IRCC priorities. According to the mandate letter for the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship, the department is intended to “lead efforts to facilitate the temporary entry of low risk travelers…”.Footnote 11

As the IEC Program crosses themes of immigration, employment, culture, foreign relations, and youth, the program aligns with other government departments, as evident through the mandate documents of GAC, Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC), and Canadian Heritage (PCH), as well as the Prime Minister’s Youth Secretariat. A few interviewees noted that while the IEC Program is unique in that it supports both foreign nationals and Canadians, as a program within the Government of Canada, it is appropriately located at IRCC.

4. Performance – Program Effectiveness

4.1. Reciprocity

Finding: Youth Mobility Agreements, including participation quotas, have been developed with the intent of being reciprocal. However, the disparity between actual foreign and Canadian youth participation in the IEC has grown over time.

4.1.1. Reciprocity in YMAs and Quotas

As specified in the Regulations, reciprocity is a central legal requirement of the program. Open work permits are issued under Immigration and Refugee Protection Regulations (paragraph 205(b)) to a “foreign national who intends to perform work that would create or maintain reciprocal employment of Canadian citizens in other countries”.Footnote 12 Work permits issued under IEC are exempt from the requirement for a LMIA.Footnote 13

The IEC Program operates through YMAs with 34 countries. The bilateral agreements and arrangements are established by the Government of Canada with foreign governments. To reflect Regulations requirements, all YMAs have been built to be reciprocal in terms of types of travel opportunities offered, duration of stays, and age groups targeted.

Reciprocity has been a foundational aspect of the IEC Program for many years, with the understanding that there is an exchange of youth between the two countries signatory to a YMA. The exact ratio objective of this exchange has changed over the years, and the current objective is a 2:1 ratio of foreign national youth to Canadian youth, which was set in 2014.

The IEC Program’s reciprocity management is fundamentally guided by IEC’s annual global target, which is monitored through annual country quotas for approved IEC work permit applications. These quotas are negotiated prior to the launching of an IEC season and are allocated both to foreign nationals coming to Canada, as well as for Canadians going abroad. The IEC Program must negotiate quota levels with foreign governments on an annual basis, after receiving ministerial approval for the number of eligible foreign nationals coming to Canada.Footnote 14 As seen in the 2017 season, quotas range from relatively low numbers (25 for San Marino) to significant numbers (14,000 for France).

4.1.2. Disparity in Reciprocity

Although the program approached numerical reciprocity in the early 2000s, in recent years, more foreign youth used the IEC Program to travel to Canada than Canadians to travel abroad. Foreign youth participation in IEC more than doubled since 2004 (from 24,202 in 2004 to 68,371 in 2017) while Canadian participation decreased by 11% (from 22,254 in 2004 to 19,857 in 2017), as seen in Figure 1. This disparity had increased from a ratio of 2:1 in 2007 to 3:1 in 2009 but has remained relatively stable since. Although Canadian participation in the program has decreased, country quotas have risen over the years.

However, since the program was transferred to IRCC in 2013, there has been an increase of Canadian participants in the IEC Program of 16%, and similarly, foreign youth participation in IEC has increased by 15%. The disparity in reciprocity has remained at 3:1 since IEC has been with IRCC.

Figure 1: Trends in IEC Program Quotas and Number of Canadian and Foreign Youth Participants, 2004 to 2017

Text version: Figure 1: Trends in IEC Program Quotas and Number of Canadian and Foreign Youth Participants, 2004 to 2017

| Year | Quotas | Canadians | Foreign nationals |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2004 | N/A | 22,254 | 24,202 |

| 2005 | N/A | 23,165 | 30,910 |

| 2006 | 34,505 | 22,973 | 33,566 |

| 2007 | 36,885 | 19,779 | 33,652 |

| 2008 | 46,445 | 18,869 | 44,442 |

| 2009 | 58,445 | 18,996 | 52,145 |

| 2010 | 59,600 | 17,857 | 54,785 |

| 2011 | 60,745 | 17,907 | 57,664 |

| 2012 | 62,145 | 17,715 | 58,094 |

| 2013 | 62,305 | 17,122 | 59,347Table note † |

| 2014 | 67,655 | 18,699 | 60,694 |

| 2015 | 67,305 | 20,119 | 55,461 |

| 2016 | 67,305 | 19,371 | 61,347 |

| 2017Table note * | 67,330 | 19,857 | 68,371 |

Source: Immigration Branch, July 2018

Note 1: Data on quotas were not available for 2004 and 2005.

Note 2: As data sources and date of data extraction vary, numbers may differ slightly.

4.1.3. Approach to Quota Management

Finding: Quota management decisions have resulted in quotas remaining the same despite lower Canadian youth uptake, thereby hindering the department’s ability to reach its 2:1 reciprocity objective.

While the quota management is an annual process, some quota management decisions contributed to greater disparity. Despite lower Canadian youth uptake, the global quotas were not adjusted downward and new YMAs were added, thereby hindering the department’s ability to reach its reciprocity objective of 2:1.Footnote 15 The following are examples of such quota management decisions:

- Non-reduction of country-specific quota: While internal documentation has shown that there has been one attempt at reducing the quotas to meet reciprocity levels, no recent quota reduction measure has been undertaken. In 2007, IRCC was not meeting the quotas in 14 out of 17 YMAs in place at the time, but country quotas had significantly increased for 9 of these YMAs by 2017 (see Table 3). For example, the quota with Japan was established at 5,000 in 2007 and increased to 6,500 by 2017. This increase took place even though only 539 Canadians went to Japan in 2007 and never increased beyond this number. Quotas were reduced for four countries (Austria, Denmark, Norway, and Switzerland). Despite those discrepancies, the status quo approach to quota management has been adopted in 2016, 2017 and 2018.

- Expansion of YMAs to new countries: Two additional YMAs were negotiated in 2017 and 2018 – San Marino and Portugal. While the addition of these two countries have not increased the global IEC quota, they have increased the pool of potential foreign youth applicants in the program, risking increased disparity between the Canadian and foreign national participation uptake. In addition, the Department is undertaking additional negotiations with additional countries, which can increase the disparity even more.

Interviewees raised concerns about numerical reciprocity not being met as a few indicated that it is difficult to argue that non-reciprocal agreements are in the national interest when the arrangements do not favour Canadians. Other interviewees indicated that without reciprocity, IEC is simply a facilitative labour market access program for foreign nationals. However, the documentation reviewed suggests that the program must find the appropriate balance between the management of numerical reciprocity (i.e., developing new YMAs and reducing quotas with certain countries) and the fostering of international bilateral relations. This was described as a complex task, especially given that outcomes related to bilateral relations are hard to assess.

Table 3: IEC Reciprocity Ratios (2007, 2013, and 2017)

2007

| Country | Quota | Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | 8,000 | 1:1 |

| Austria | 100 | 6:1 |

| Belgium | 490 | 3:1 |

| Chile | YMA signed in 2008 | YMA signed in 2008 |

| Costa Rica | YMA signed in 2011 | YMA signed in 2011 |

| Croatia | YMA signed in 2011 | YMA signed in 2011 |

| Czech Republic | 400 | 14:1 |

| Denmark | 400 | 4:1 |

| Estonia | YMA signed in 2010 | YMA signed in 2010 |

| France | 9,770 | 2:1 |

| Germany | 2,525 | 29:1 |

| Greece | YMA signed in 2013 | YMA signed in 2013 |

| Hong Kong | YMA signed in 2010 | YMA signed in 2010 |

| Ireland | 2,000 | 2:1 |

| Italy | 400 | 6:1 |

| Japan | 5,000 | 9:1 |

| South Korea | 800 | 39:1 |

| Latvia | YMA signed in 2008 | YMA signed in 2008 |

| Lithuania | YMA signed in 2010 | YMA signed in 2010 |

| Mexico | YMA signed in 2011 | YMA signed in 2011 |

| Netherlands | 300 | 2:1 |

| New Zealand | 2,000 | 1:1 |

| Norway | 400 | 30:1 |

| Poland | YMA signed in 2007 | YMA signed in 2007 |

| Portugal | YMA signed in 2018 | YMA signed in 2018 |

| San Marino | YMA signed in 2016 | YMA signed in 2016 |

| Slovakia | YMA signed in 2011 | YMA signed in 2011 |

| Slovenia | YMA signed in 2010 | YMA signed in 2010 |

| Spain | YMA signed in 2010 | YMA signed in 2010 |

| Sweden | 175 | 9:1 |

| Switzerland | 400 | 1:1 |

| Taiwan | YMA signed in 2010 | YMA signed in 2010 |

| United Kingdom | 3,725 | 1:1 |

| Ukraine | YMA signed in 2010 | YMA signed in 2010 |

| Total | 37,085 | 2:1 |

2013

| Country | Quota | Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | 9,000 | 1:1 |

| Austria | 80 | 0:1 |

| Belgium | 750 | 8:1 |

| Chile | 750 | 50:1 |

| Costa Rica | 100 | 4:1 |

| Croatia | 300 | 131:1 |

| Czech Republic | 1,150 | 19:1 |

| Denmark | 350 | 9:1 |

| Estonia | 125 | 18:1 |

| France | 14,000 | 5:1 |

| Germany | 5,000 | 8:1 |

| Greece | 200 | 58:1 |

| Hong Kong | 200 | 4:1 |

| Ireland | 6,350 | 16:1 |

| Italy | 1,000 | 5:1 |

| Japan | 5,500 | 22:1 |

| South Korea | 4,000 | N/A |

| Latvia | 50 | 12:1 |

| Lithuania | 200 | 21:1 |

| Mexico | 250 | 267:1 |

| Netherlands | 600 | 1:1 |

| New Zealand | 2,500 | 2:1 |

| Norway | 150 | 6:1 |

| Poland | 750 | 118:1 |

| Portugal | YMA signed in 2018 | YMA signed in 2018 |

| San Marino | YMA signed in 2016 | YMA signed in 2016 |

| Slovakia | 350 | 43:1 |

| Slovenia | 100 | 87:1 |

| Spain | 1,000 | 6:1 |

| Sweden | 700 | 9:1 |

| Switzerland | 250 | 7:1 |

| Taiwan | 1,000 | 39:1 |

| United Kingdom | 5,350 | 1:1 |

| Ukraine | 200 | N/A |

| Total | 62,305 | 3:1 |

2017

| Country | Quota | Ratio |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | 9,000 | 1:1 |

| Austria | 80 | 1:1 |

| Belgium | 750 | 13:1 |

| Chile | 750 | 36:1 |

| Costa Rica | 100 | N/A |

| Croatia | 300 | 74:1 |

| Czech Republic | 1,150 | 9:1 |

| Denmark | 350 | 4:1 |

| Estonia | 125 | 13:1 |

| France | 14,000 | 7:1 |

| Germany | 5,000 | 9:1 |

| Greece | 200 | 20:1 |

| Hong Kong | 200 | 3:1 |

| Ireland | 10,700 | 13:1 |

| Italy | 1,000 | 7:1 |

| Japan | 6,500 | 14:1 |

| South Korea | 4,000 | 117:1 |

| Latvia | 50 | N/A |

| Lithuania | 200 | 21:1 |

| Mexico | 250 | N/A |

| Netherlands | 600 | 1:1 |

| New Zealand | 2,500 | 1:1 |

| Norway | 150 | 3:1 |

| Poland | 750 | 62:1 |

| Portugal | YMA signed in 2018 | YMA signed in 2018 |

| San Marino | N/A | N/A |

| Slovakia | 350 | 50:1 |

| Slovenia | 100 | 6:1 |

| Spain | 1,000 | 3:1 |

| Sweden | 700 | 5:1 |

| Switzerland | 250 | 3:1 |

| Taiwan | 1,000 | 14:1 |

| United Kingdom | 5,000 | 2:1 |

| Ukraine | 200 | N/A |

| Total | 69,385 | 3:1 |

Source: Immigration Branch, July 2018.

Note 1: 2017 data for Costa Rica and Switzerland was not available.

Note 2: N/A - Reciprocity ratios could not be calculated as no Canadians went to those countries through the IEC Program.

Note 3: The YMAs with Mexico and Ukraine are currently on hold.

4.1.4. Opportunities

Finding: Some foreign countries’ burdensome application and processing requirements as well as economic conditions have contributed to greater youth participation disparity.

Although all YMAs have been built to be as reciprocal as possible in terms of types of travel opportunities offered, duration of stays, and age groups, there are still some challenges in ensuring reciprocal opportunities for Canadian youth to participate to the IEC Program. These challenges include immigration process of other countries not being as facilitative as the Canadian system (e.g., required in person applications, language of application other than English or French, higher participation fees), and economic factors (e.g., foreign country youth unemployment rate and wages). These challenges have also contributed to the disparity in program participation.

Application and processing requirements of foreign countries

- Requirement for in-person visits: 20 out of 34 require an in-person visit at an embassy or consular office in Canada prior to departure. These offices are most commonly located in Ottawa, Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver, and can be a barrier to those who live in the prairies or eastern Canada as the travel to an embassy/consular office would be an additional cost.

- Some countries, Czech Republic and Costa Rica for example, require that applications be made in languages that are not English or French. While reasonable requirements on the part of the foreign countries, this limits Canadian participants to only those who speak the language of the country.

- Some countries require higher fees to be paid in order to participate. While Canada offers a similar system, the fees for some countries can be financial barriers to Canadian participants as youth generally have limited funds. For example, participation and application fees for Ireland can be approximately $600CAD compared to $150CAD for Irish participants.

Economic conditions of foreign countries

- Youth unemployment rates in OECD countries, Canada included, have traditionally been higher than the average unemployment rate.Footnote 16 While Canada’s youth unemployment rate has hovered around 13% since 2013, other YMA countries have experienced higher youth unemployment rates including Belgium (20%) France (24%), Italy (37%), Spain (44%), Greece (47%).Footnote 17 High youth unemployment rates in foreign countries may result in increased interest among foreign youth to travel to Canada, while making working abroad less appealing for Canadians.

- Recognizing that the purchasing power may be different across countries, minimum wages in foreign countries are not always comparable and can have an impact on youth participation. For example, while Ireland has a comparable minimum wage to Canada (9.3 USD in 2017), countries like Estonia (4.3 USD), and Chile (3.0 USD) may deter Canadian youth from intending to work in these countries.Footnote 18

4.2. Motivations to Participate in IEC

4.2.1. Foreign Youth Motivations

Finding: Overall, the main reason cited by foreign and Canadian youth participants in the IEC Program was the travel experience; though, foreign youth motivations varied by stream.

The survey of foreign youth participants found that respondents’ main motivations for participating in the IEC were: pursuing travel experiences that contribute to personal growth (68%), exploration and adventure (66%) and to learn about a new country (65%). To a lesser extent, survey respondents also indicated obtaining international career experience or professional development (46%) and learning or improving a secondary language (37%) as motivations to their experience. Motivations to participate also varied to some extent by stream, with more Co-op and Young Professionals indicating obtaining international career experience or professional development as a motivation for their trip (81% and 64% respectively), compared to the Working Holiday stream (41%). On the other hand, a higher proportion of the Working Holiday stream participants indicated exploration and adventure (69%) as a motivation compared to the other streams (53%).

Similarly, Canadian youth who travelled to New Zealand under the IEC Program participated in a working holiday experience, and most frequently cited exploration and adventure (79%), pursuing travel experiences that contributes to personal growth (70%), and to learn about a new country or culture (55%) as a motivation to their travel.

These survey results align with documents reviewed, which point to various motivations for youth travelling abroad. According to tourism studies and academics, millennial travelers tend to seek out social and experiential travel activities that will lead to personal growth. Also, tourism studies indicated that millennial travelers’ most important motivations are to interact with local people and experience everyday life in another country.Footnote 19 Key motivations for participation in working holiday programs noted by academics can also include improving language abilities, cultural reasons and wanting to ‘escape’ pressure at home or at work.Footnote 20

4.3. Awareness of IEC

Finding: Foreign youth awareness of and participation in the IEC Program is higher than that of Canadian youth. While IRCC and ROs have been actively promoting this program for the past few years, these activities have not yet resulted in reducing the disparity in uptake.

4.3.1. Foreign Youth Awareness

Despite limited outreach activities abroad, the IEC Program has been successful in attracting foreign youth to Canada. As demonstrated in Section 4.1.2, foreign youth coming to Canada largely outnumber the Canadian youth travelling abroad via IEC. Each year about 50,000 to 60,000 foreign youth travel to Canada under the IEC, while Canadian youth participation has been around 20,000 annually.

Interviewees indicated that only a few promotional activities targeting foreign youth were conducted as there is a minimal need for outreach to this group. Outreach activities that are taking place to increase awareness and attract foreign youth include IRCC’s website, social media and ROs.

In addition to IRCC’s website where prospective applicants can find information, IRCC provides information through various social media channels such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram and YouTube. These promotional activities correspond with the sources used by foreign youth to get information about the program. Foreign youth survey respondents most often identified Government of Canada websites (96%), IEC social media (49%) and ROs (30%) as sources they used to obtain information on the IEC Program.

Between January 2015 and May 2018, there were 8.97 million views of the IEC webpages dedicated to foreign youth wanting to come to Canada. Over this period, IEC’s presence on social media increased.Footnote 21

In addition to IRCC’s efforts, ROs also conduct promotional activities. Nearly all RO survey respondents (92%) reported that their organization conducts promotional activities to raise awareness of IEC and all ROs reported that they provided information about the program on their website. When asked which groups they targeted through their promotional activities, just over half of ROs (55%) indicated that they targeted foreign youth.

4.3.2. Canadian Youth Awareness

Interviewees and documents reviewed point to extensive IRCC engagement and promotional efforts aimed at increasing Canadian youth awareness of the IEC Program. Examples includeFootnote 22:

- Participation in conferences, fairs, and information sessions for youth and youth influencers;

- Engagement/consultations with stakeholders, resulting in information sharing exercises, research and consultations, pilot projects, and other initiatives;

- Development and implementation of marketing, advertising and outreach initiatives (including promotional products), following the program rebranding in 2017;

- Membership in influential working groups and advisory committees; and

- Social media outreach activities.

While previous IEC promotional efforts have primarily focused on Canadian youth, recent promotional activities, as identified in the program’s 2016 stakeholder engagement strategy, have been expanded to include “influencers”Footnote 23. Given these promotional activities are relatively new, it will take a few more years before noticing changes in awareness behaviour as a result of the various promotional efforts.

Canadian youth who want to work and travel abroad with IEC can also find information about the program on IEC’s website. Between January 2015 and May 2018, there have been 460,813 views for IEC’s website for Canadians, representing 5% of IEC’s total page views during this period. However, although IEC has been actively promoting the program to foreign youth, through social media for many years, IEC only started recently to promote the program for Canadians going abroad through the social media. For example, a Facebook account for Canadians going abroad was created in August 2017.

In addition to IRCC’s promotion, all RO survey respondents indicated that their promotional efforts focus on Canadian youth.

Promotional Challenges

The most common challenge highlighted by key informants was promoting the program to Canadians and increasing Canadian participation. Some barriers to promotion were described by interviewees. For example, a few interviewees indicated that the program’s funding mechanism prevents them from proceeding with different communications and promotions activities to advertise the program.

It was also highlighted that the restrictions of using government products, which are not always what is available for partners (e.g., Dropbox for files with partners, Skype calls, etc.), government advertising restrictions, and an inability to do different types of promotions (e.g., webinars) are barriers to promoting the IEC Program effectively.

Despite IRCC’s and other program stakeholders’ promotional efforts, awareness of the program among Canadian youth remains low, as suggested by the lower number of Canadians using the program to travel abroad.

Further, a public opinion research survey conducted with Canadian youth (PCO Youth survey, n=632) highlighted that 12% of Canadian survey respondents who were between 18 and 35 years of age indicated being extremely or very aware, and 27% moderately or somewhat aware of the IEC Program, while 59% indicated they were not at all aware of the program. Awareness, however, gradually increased with age; 28% of those aged between 18 and 20 reported being at least somewhat aware of the program, while 63% of those aged between 31 and 35 did so.

4.4. Cultural and Professional Experiences

This sub-section examines the extent to which IEC participants gained diverse cultural and professional experiences through their participation in the program.

4.4.1. Cultural Experiences

Finding: Both IEC foreign and Canadian youth participants report gaining a variety of cultural experiences and learning about the country to which they travelled as a result of their participation in the program.

Foreign youth survey respondents indicated obtaining various types of cultural experiences. Almost all (98%) reported visiting some cultural sites in Canada. More specifically, a majority of respondents cited that visiting national and provincial parks (86%), museums (73%) and monuments (71%). Nearly all respondents (91%) also indicated participating in cultural events, with three-quarters attending musical events (74%) and attending sporting events (73%).

In the same way, Canadians who obtained a working holiday experience in New Zealand indicated having visited national parks (97%), a museum (84%), and monuments (79%). The majority also participated in at least one type of cultural activity (86%), either a musical event (67%), a sporting event (58%), a theatrical event (40%) or another type of cultural event (10%).

In addition, the majority of IEC participants developed ties to the country to which they travelled as part of their IEC experience. The majority of foreign youth survey respondents (91%) indicated having developed friendships with Canadians while they were in Canada and 98% of Canadians said they made friends with non-Canadians while they were in New Zealand. To a lesser extent, foreign youth respondents also indicated having developed social networks (65%) with Canadians, while a greater proportion of Canadians (83%) mentioned having developed social networks with non-Canadians. Only 1% of foreign and Canadian youth respondents reported not having formed friendships or networks while they were in abroad as part of their IEC experience.

When asked about the key benefits they gained from their IEC experience in Canada, the three main benefits identified by foreign youth were: learning about a new country or culture (86%), having an international experience that contributed to their personal growth (81%) and explorations and adventures (79%). However, perceived benefits varied by IEC stream. A greater proportion of foreign youth respondents from the Working Holiday stream identified exploration and adventures as a key benefit of their IEC participation (81%), compared to respondents from the Co-op and Young Professionals streams (70% and 69% respectively). The same key benefits were also identified by Canadians who travelled to New Zealand, although in different proportion; 94% of Canadian youth identified exploration and adventure as a key benefit, 90% learning about a new country or culture, and 88% having an international experience that contributed to their personal growth.

Overall, most foreign youth survey respondents (83%) indicated having learned a lot about Canada during their IEC experience. Similarly, 93% of Canadians who obtained a working holiday experience in New Zealand indicated having learned a lot about this country.

4.4.2. Professional Experiences

Finding: The large majority of IEC foreign and Canadian youth participants have gained professional experiences while abroad as part of the IEC Program, which they reported is a key benefit that will help them in their careers.

Professional Experiences of Foreign Youth

A significant portion of IEC participants work during their stay in Canada. CEEDD data indicates that incidence of employment among IEC foreign youth participants remained stable at around 60% between 2004 and 2015, while their average employment earnings have steadily increased year over year from an average of $5,200 in 2004 to $15,300 in 2015 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Incidence and Average Employment Earnings of IEC Foreign Youth Participants, 2004 to 2015

Text version: Figure 2: Incidence and Average Employment Earnings of IEC Foreign Youth Participants, 2004 to 2015

| Year | Incidence of employment earnings | Average employment earnings |

|---|---|---|

| 2004 | 61.17 | 5,200 |

| 2005 | 59.14 | 6,700 |

| 2006 | 62.16 | 7,700 |

| 2007 | 64.34 | 8,800 |

| 2008 | 62.41 | 9,500 |

| 2009 | 58.83 | 10,200 |

| 2010 | 57.63 | 10,900 |

| 2011 | 57.79 | 12,400 |

| 2012 | 59.76 | 13,300 |

| 2013 | 61.66 | 13,800 |

| 2014 | 63.78 | 15,300 |

| 2015 | 64.13 | 15,300 |

Source: CEEDD, 2015

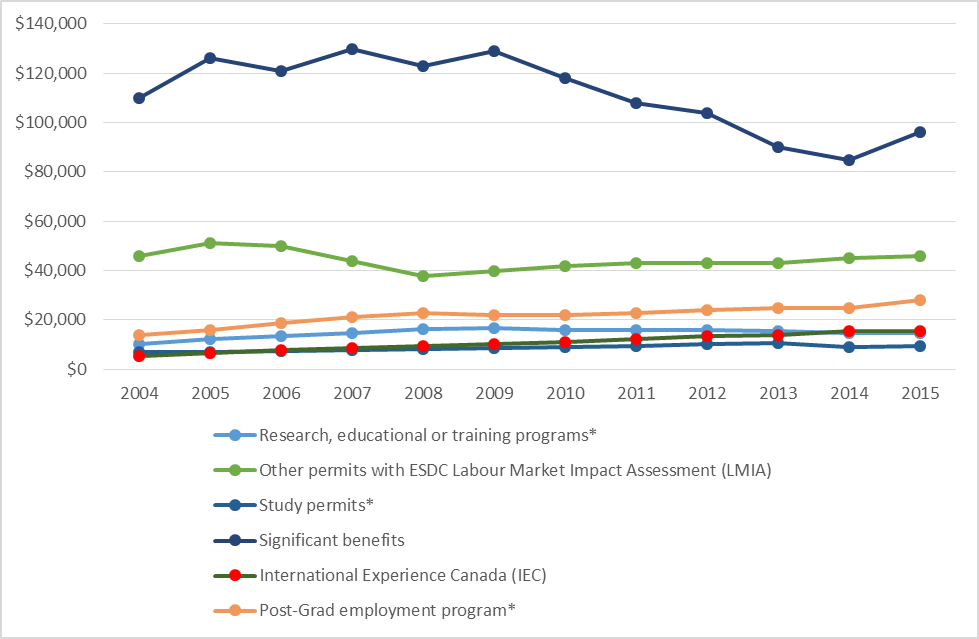

Compared to IRCC’s other temporary foreign worker programs, there are only three which have a higher incidence of employment than IEC foreign youth participants as reported by employers through T4s (Agricultural Workers, Caregiver and Post-Graduate employment programs). However, average employment earnings for the IEC are lower than that of all Temporary Resident (TR) programs, with the exception of Temporary Residency Permits, suggesting that IEC foreign youth working in Canada may be occupying lower skilled and/or entry-level positions, and that many of them are working mainly to support their travel or work for shorter periods of time during the year (see Annex F for more details on results from the CEEDD analysis).

When asked directly to youth, nearly all foreign youth survey respondents self-reported working during their IEC experience (90%), which is a significantly greater proportionFootnote 24 than the one declared by employersFootnote 25 in the CEEDD. When comparing IEC streams, less than two thirds of foreign youth respondents under the Co-op stream indicated working during their IEC experience (63%). This is a much smaller proportion compared to respondents under the Working Holiday (93%) and the Young Professionals (98%) streams.

Of those who were working, a little over a quarter (27%) of foreign youth survey respondents who worked during their IEC experience had made arrangements for employment prior to coming to Canada, though this varied by stream (Co-op: 94%; Young Professionals: 49%; and Working Holiday: 19%).

Of those who were employed, most foreign youth survey respondents (82%) reported receiving financial compensation.Footnote 26 While the majority of respondents under the Young Professionals (90%) and the Working Holiday (84%) streams received financial compensation for their work, those under the Co-op stream were split with 42% indicating that they did not receive financial or in-kind compensation and 40% indicating they received financial compensation. Of the foreign youth survey respondents who were not compensated for their work, most (79%) indicated that they participated in an unpaid internship.

Among the sectors in which foreign youth were working, the most commonly reported were: accommodation and food services (30%), professional, scientific and technical services (12%), and retail trade (8%).

About three quarters (76%) of respondents indicated working in Canada for at least 6 months, and a majority (80%) indicated working full-time (i.e., 30 hours a week or more). The largest proportion of respondents reporting full-time employment was found among those from the Young Professionals stream (94%), followed by respondents from the Co-op (86%) and Working Holiday (78%) streams.

Professional Experiences of Canadian Youth

Similar to what was reported by foreign youth, the majority (90%) of Canadians who had a working holiday experience in New Zealand reported working during their stay, with 20% of those who worked having made employment arrangements prior going abroad. Most also indicated working full-time (71%) and almost all (99%) Canadians who worked reported having been compensated for their work, either through financial compensation only (74%); both financial and in-kind compensation (18%); or in-kind compensation only (7%). Most often Canadians worked in: accommodation and food services (34%); agriculture, forestry and fishing (17%); and arts, entertainment and recreation (6%).

Professional Benefits Gained by IEC Youth Participants

Foreign youth survey respondents indicated that they benefited from the professional experience gained through the program. Over half (57%) of respondents identified obtaining international career experience or professional development as a key benefit of their participation in IEC. A higher proportion of respondents who came to Canada under the Co-op (83%) and Young Professionals (77%) streams reported this as a benefit, compared to the Working Holiday stream (52%). In addition, about 70% of survey respondents agreed that the IEC Program will help them in their future employment and about two thirds (67%) of respondents who had completed their IEC experience and who were working at the time of the survey agreed that the IEC Program helped them in their current employment situation.

Although to a lesser extent than foreign youth participants, almost half of Canadian youth indicated obtaining international career experience or professional development (47%) as a key benefit of their working holiday experience in New Zealand, and about 60% of those who were working at the time of the survey agreed that their working holiday experience abroad helped them in their current employment situation. About two thirds (64%) also felt that their working holiday experience would help them in their future employment.

4.5. Supporting Canada’s International, Economic, and Social Interests

This section examines the program’s ultimate outcome, including a discussion on IEC activities and outputs that support Canada’s international, economic, and social interests.

4.5.1. Supporting Canada’s International and Social Interests

Finding: The IEC Program is contributing to Canada’s social and international interests, as it has been used as a tool to foster bilateral relationships and increased youth awareness and understanding of other cultures.

Most interviewees noted that the IEC Program is supporting Canada’s social interests. They indicated that exposure to different cultures was the main avenue through which IEC supports Canada’s social interests. It was also noted that being immersed in a culture (living and working) has a significant benefit as it goes beyond just being a tourist. As such, interviewees indicated that by having youth develop an understanding of international issues and Canada’s place in the world, it allows them to think globally, which supports Canada’s social interests as a result. This was also supported by document review, where Horn et al.Footnote 27 indicated, in their study, that international experiences lead to higher intercultural competence than domestic experience.

Some interviewees suggested that Canada’s social interests are not only supported by Canadian youth travelling abroad, but also by having foreign youth travelling to Canada under the IEC and interacting with Canadians, further exposing Canadians to other cultures. A few interviewees also indicated that Canadians serve as ambassadors for Canada when they go abroad.

Research demonstrates that youth with global experience have higher adaptability skills, better planning abilities, and are more assertive, decisive and persistent relative to individuals with no global experience.Footnote 28 While these findings relate to international experiences more generally, IEC provides youth with the opportunity to obtain global experiences, likely leading to these benefits for program participants.

Furthermore, adding to the benefits of Canadian youth travelling abroad through IEC, document and administrative data analysis show that IEC applicants are well educated, young, speak either English, French, or both (as well as a third language in many cases), thus making them an ideal target to recruit for permanent residency. Overall, administrative data indicates that 7% of IEC foreign youth who came to Canada under the IEC Program between 2013 and 2017 have permanently immigrated to Canada, further enriching Canada’s diversity.

In addition to supporting Canada’s social interests, many interviewees indicated that the IEC Program also supports Canada’s international interests as the program is used as a diplomatic tool or a mechanism for international relations. As such, the program can be leveraged in bilateral relations with other countries. Documents reviewed have indicated that people-to-people ties and bilateral relations are outputs of the program, which can lead to economic spin-offs by building trade and economic bridges in the future.

4.5.2. Supporting Canada’s Economic Interests

Finding: The IEC program supports Canada’s economic interests by providing a pool of foreign workers for Canada, offering Canadian youth opportunities to gain valuable work and professional experience, and by generating tourism revenues. However, the program’s impact on the Canadian labour market needs further investigation.

In 2017, there was a potential pool of almost 70,000 foreign workers made available to Canadian labour market through the IEC. In addition, some IEC foreign youth are working in sectors and provinces that have traditionally experienced labour shortages according to CEEDD and survey data. A 2018 Business Development Bank of Canada (BDC) survey indicated that labour shortages are most serious in Atlantic Canada, British Columbia and Ontario and that sectors facing the strongest difficulties include manufacturing, retail trade and construction. Somewhat aligning with where shortages were identified, the provinces most visited by foreign youth survey respondents were Ontario (59%) and British Columbia (57%). In addition, a 2010 to 2015 CEEDD trend analysis indicated that about 20% of IEC foreign youth participants who worked in Canada during their IEC stay have done so in manufacturing, retail trade and construction (see Table 4).

Table 4: Sector Distribution of IEC Participants with Employment Earnings, CEEDD

| Sector | 2010 (%) |

2011 (%) |

2012 (%) |

2013 (%) |

2014 (%) |

2015 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, Forestry, Fishing and Hunting | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.7 |

| Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction | 0.3 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| Utilities | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| Construction | 7.8 | 4.3 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 6.2 | 5.9 |

| Manufacturing | 3.1 | 3.8 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 3.8 | 3.6 |

| Wholesale Trade | 1.8 | 2.1 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 2.3 | 2.2 |

| Retail Trade | 13.3 | 12.6 | 12.5 | 12.2 | 11.4 | 11.8 |

| Transportation and Warehousing | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.2 |

| Information | 1.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 1.9 | 1.8 | 2.0 |

| Finance and Insurance | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.4 |

| Real Estate and Rental and Leasing | 2.0 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 1.9 | 2.0 | 2.2 |

| Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services | 5.1 | 5.8 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 5.5 | 5.4 |