ARCHIVED – Evaluation of the Resettlement Programs (GAR, PSR, BVOR and RAP)

July 7, 2016

Final Report

Evaluation of the Resettlement Programs (GAR, PSR, BVOR and RAP) (PDF, 908.03KB)

Table of contents

- Acronyms

- Executive Summary

- Evaluation of the Resettlement Programs—Management Response Action Plan

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Methodology

- 3. Key Findings: Relevance

- 4. Key Findings: Performance – Management Outcomes

- 5. Key Findings: Performance - Program Outcomes

- 5.1. Canada’s Contribution to International Protection Efforts

- 5.2. Program Delivery – Supports and Challenges

- 5.3. Coordination with Stakeholders

- 5.4. Canadians’ Engagement in Supporting Resettlement and Contribution to Uniting Refugee Families

- 5.5. Processing Effectiveness and Efficiency

- 5.6. Matching and Arrivals

- 5.7. Unintended Impacts of the Resettlement Programs

- 5.8. Immediate and Essential Needs of Resettled Refugees

- 5.9. Adequacy of Income Support to Meet Essential Needs

- 5.10. Economic Integration

- 6. Key Findings: Performance – Resource Utilization Outcomes

- 7. Conclusions and Recommendations

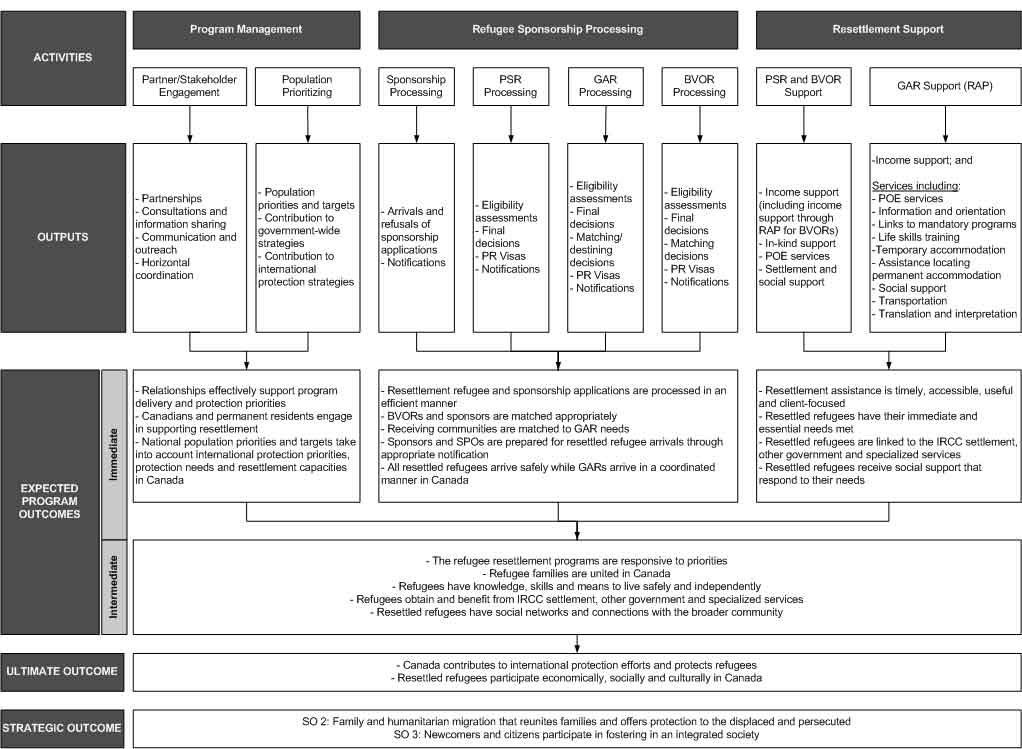

- Appendix A: Refugee Resettlement and Resettlement Assistance Programs Logic Model: GAR, PSR, BVOR and RAP Programs

- Appendix B: Lines of Evidence Used in the Evaluation

- Appendix C: Management Responses for Previous PSR (2007) and GAR-RAP (2011) Evaluations

List of tables and figures

- Table 1: Admissions by Year and Resettlement Program, excluding Quebec (2010-2014)

- Table 2: Evaluation Questions

- Table 3: Survey Completion and Response Rate

- Table 4: Qualitative Data Analysis Scale

- Table 5: Overall Targets and Admissions for GARs, PSRs and BVOR refugees (2010-2014)

- Table 6: UNHCR Resettlement Departures by Resettlement Country 2010-2014*

- Table 7: Number and Proportion of PSRs Sponsored, by Sponsoring Group

- Table 8: GAR and PSR Year-End Inventory (2010-2014)

- Table 9: Referrals to Settlement Services

- Table 10: Satisfaction with Cost and Actual Cost of Refugees’ First Permanent Accommodation

- Table 11: RAP Income Support Rates and Average Housing Cost

- Table 12: Social Assistance compared to RAP Income Support in Sample Cities for Single Adults (2014)

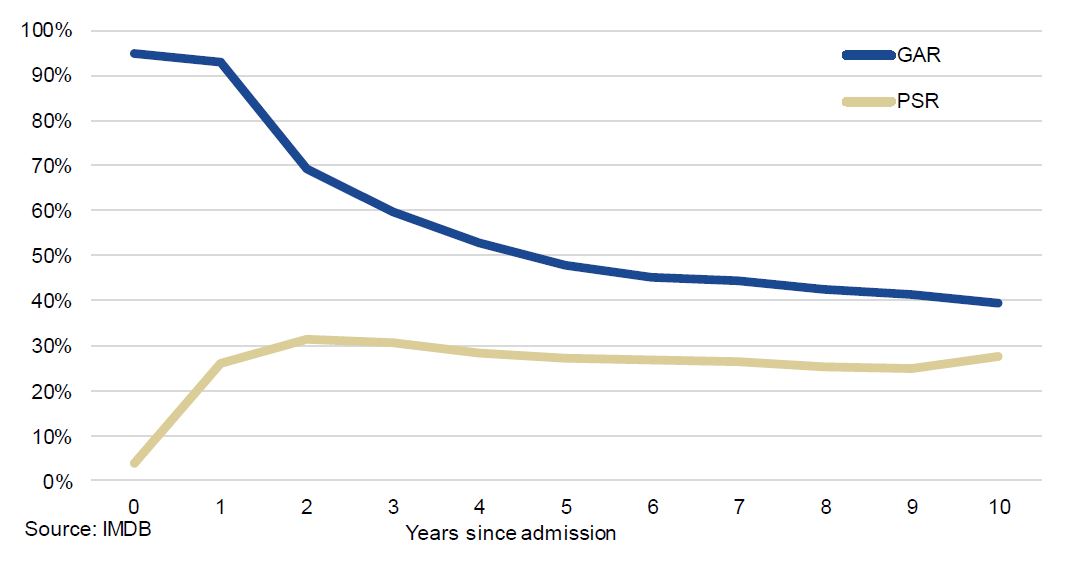

- Figure 1: Percentage of Refugee Families Who Declared Social Assistance Benefits by Year since Admission and Immigration Category (2002-2012)

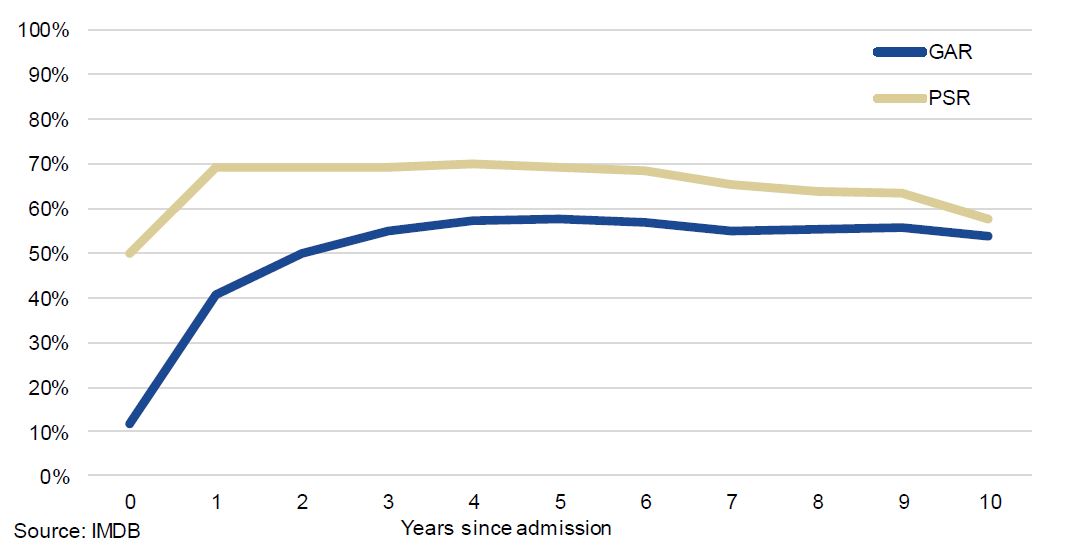

- Figure 2: Percentage of Individual Refugees Who Declared Employment Earnings by Year since Admission and Immigration Category (2002-2012)

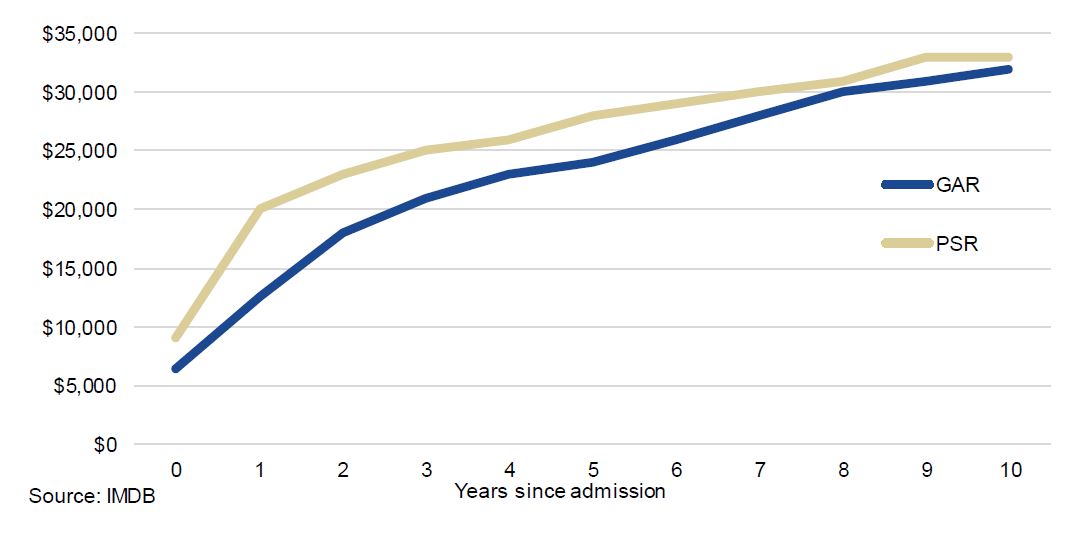

- Figure 3: Average Employment Earnings by Year since Admission and Immigration Category (2002-2012)

- Table 13: Total Program Costs

- Table 14: Processing Costs for Refugee Groups (Unit Cost by Program)

Acronyms

- BVOR

- Blended Visa Office-Referred

- CCR

- Canadian Council for Refugees

- CG

- Constituent Group

- CIC

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada

- CMHC

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

- CPO-W

- Centralized Processing Office - Winnipeg

- CS

- Community Sponsors

- CSS

- Client Support Services

- CVOA

- Canadian Visa Office Abroad

- DMR

- Destination Matching Request

- FOSS

- Field Operations Support System

- G5

- Group of Five

- GAR

- Government Assisted Refugee

- GCMS

- Global Case Management System

- HIAS

- Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society

- iCAMS

- Immigration Contribution Accountability Measurement System

- iCARE

- Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment

- IFH

- Interim Federal Health

- IOM

- International Organization for Migration

- IMDB

- Longitudinal Immigration Database

- IRCC

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- IRPA

- Immigration and Refugee Protection Act

- LES

- Locally Engaged Staff

- LGBTIQ

- Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Intersex, and Questioning

- NAT

- Notice of Arrival Transmission

- NGO

- Non-Governmental Organization

- NHQ

- National Headquarters

- PSR

- Privately Sponsored Refugee

- RAP

- Resettlement Assistance Program

- RAP SPO

- Resettlement Assistance Program Service Provider Organization

- RSD

- Refugee Status Determination

- RSTP

- Refugee Sponsorship Training Program

- SAH

- Sponsorship Agreement Holder

- SPO

- Service Provider Organization

- UNHCR

- United Nations Refugee Agency (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees)

- VOR

- Visa Office-Referred

Executive Summary

The evaluation of the Resettlement Programs was conducted in fulfilment of the 2009 Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation and section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act. The programs under review included Government Assisted Refugee (GAR) program, Privately Sponsored Refugee (PSR) program, Blended Visa-Office Referred (BVOR) program, and the Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP). While the evaluation covered the period of 2010 to 2015, the government’s commitment to admit 25,000 Syrian Refugees, launched in November 2015, is not covered in this evaluation.

Evaluation Findings

Relevance

The evaluation found that there is a continued need to provide protection to refugees and resettlement assistance upon arrival in Canada. In addition, the Resettlement Programs are in alignment with Government of Canada and departmental priorities to support humanitarian objectives, while being consistent with federal roles and responsibilities.

Performance – Management Outcome Findings

Multi-year commitments and yearly targets provide opportunities to the department for both planning and flexibility regarding the ability to meet emerging needs. However, there are challenges to implementing the yearly targets. And while numerous steps have been taken by Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada (IRCC) to address the recommendations from the previous evaluations in 2008 and 2011, certain recommendations remain outstanding.

Performance – Program Findings

Evidence indicated that Canada has effectively contributed to international protection efforts and was one of the top three resettlement countries in terms of volume between 2010 and 2014. Canadians continue to demonstrate active engagement in refugee sponsorship through Sponsorship Agreement Holders (SAH) and Group of 5 (G5); however, less engagement occurred through the BVOR program, at the time of the evaluation.

Between 2010 and 2014, PSRs had lower approval rates and longer processing time compared to GARs. However, during the same time period, the department has been successful in reducing the PSR inventory by 13%, while the GAR inventory increased by 35%.

The immediate and essential needs of resettled refugees were found to be met through RAP and private sponsors; however, not enough time is allocated to the provision of RAP services for GARs with greater needs, including finding permanent housing. Evidence also indicated that RAP income support levels continue to be inadequate to meet essential needs of refugees.

Since 2002, GARs tended to have lower economic performance compared to PSRs. Specifically, GARs had lower incidence of employment, lower employment earnings and higher reliance on social assistance.

Regarding program delivery, gaps were observed regarding the monitoring around the PSR program, and a lack of clarity of the guidance for the BVOR program. While mechanisms are in place to coordinate program delivery, internal stakeholders expressed the need for greater coordination and governance within IRCC.

Resource Utilization

Evidence indicated that the total annual processing cost for refugee programs decreased between fiscal year (FY) 2011/12 and FY 2014/15, and per unit processing costs increased for GARs and decreased for PSRs. For RAP, while the overall RAP cost per client has remained relatively stable, the average RAP income support provided to GARs and RAP SPOs to deliver the program has decreased over time.

Conclusions and Recommendations

While the evidence indicated that GAR, PSR, BVOR and RAP programs are aligned with departmental priorities, the evaluation found that there were some challenges regarding various aspects of the programs, most notably the adequacy of RAP income support, the lack of clarity regarding the BVOR program, lengthy processing times for PSRs, and a lack of clear roles and responsibilities concerning the internal governance of the resettlement programs. As a result, the subsequent recommendations were developed to address these issues. The department has agreed with these recommendations and has developed a management response action plan to address them.

Recommendation 1: IRCC should develop policy options to ensure that refugees supported by the Government of Canada are provided with a sufficient level of support (including RAP income support) to meet their resettlement needs in support of their successful integration.

Recommendation 2: To improve the BVOR program, IRCC should:

- clarify the distinction between BVOR and Visa Office-Referred (VOR) programs in operational guidance (e.g., manuals and bulletins);

- review candidacy criteria for the BVOR program and implement a consistent and transparent practice to enroll refugees into the BVOR program; and

- develop an engagement strategy for SAHs to increase uptake of the BVOR program.

Recommendation 3: IRCC should develop a strategy to improve privately-sponsored refugees’ awareness of the supports available to them during their first year in Canada.

Recommendation 4: IRCC should review its application intake management tools and approaches and implement measures to ensure timely decisions on PSR applications.

Recommendation 5: IRCC should review the roles and responsibilities of branches involved in the Resettlement Programs and implement a strengthened governance structure to improve coordination.

Recommendation 6: IRCC should provide additional support to IRCC staff, sponsors and Resettlement Assistance Program Service Provider Organizations in its refugee processing network. In particular, IRCC should consider:

- increasing opportunities for training across Canadian Visa Office Abroad (CVOA), local IRCC office staff and Groups of Five and Community Sponsors;

- expanding the sharing of best practices across CVOA and local IRCC offices; and

- developing a tool to support the automatic calculation of RAP income support.

Evaluation of the Resettlement Programs—Management Response Action Plan

Recommendation #1

IRCC should develop policy options to ensure that refugees supported by the Government of Canada are provided with an adequate level of support (including RAP income support) to meet their resettlement needs in support of their successful integration.

Response #1

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

The Department acknowledges the importance of extending resettlement and settlement services, along with financial support, to refugees to assist in their full participation in the economic, social, and cultural life in Canada. The services and financial support provided to resettled refugees are designed to recognize and accommodate their unique circumstances and needs.

However, IRCC also recognizes the fiscal, structural and policy constraints associated with changes to income support levels for refugees, particularly the significant constraint represented by the need to generally align with the average levels of income and services delivered by provinces and territories.

Action #1a

IRCC will develop comprehensive policy options on how RAP could be modified to provide eligible RAP clients with adequate resources and services to meet their immediate and essential needs in support of their transition towards successful integration.

In doing so, IRCC will consider:

- the impact of the current level of income support and types of services on the capacity of clients to effectively settle and integrate in Canada;

- the unique circumstances of resettled refugees given the humanitarian objectives of the resettlement programs;

- the impact of any potential changes on a client’s ability to successfully transition from RAP onto other sources of income;

- the current RAP service programming’s linkages with settlement programs and community-based services;

- the possible effects of any change on key resettlement stakeholders, such as provinces and territories;

- issues of fairness; and

- the financial priorities of the Government of Canada, and the value for money of the proposed options.

Accountability: ADM Strategic and Program Policy (RAB). Support: ADM Operations (IPMB), ADM Finance, ADM Strategic and Program Policy (IFCRO). Completion Date: March 2017.

Action #1b

The options will be presented to senior management and policy and program changes will be implemented, as required.

Accountability: ADM Strategic and Program Policy (RAB). Support: ADM Operations (IPMB), ADM Finance, ADM Strategic and Program Policy (IFCRO). Completion Date: March 2018.

Recommendation #2

To improve the BVOR program, IRCC should:

- clarify the distinction between BVOR and VOR programs in operational guidance (e.g., manuals and bulletins);

- review candidacy criteria for the BVOR program and implement a consistent and transparent practice to enroll refugees into the BVOR program; and

- develop an engagement strategy for SAHs to increase uptake of the BVOR program.

Response #2

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

While the Department acknowledges the gaps identified in the BVOR program during the period examined for the evaluation, since the implementation of the 2015-2016 Syrian refugee initiative, significant advances have been made. As a result of this progress, sponsor interest and uptake in the program has grown to such a degree that demand now significantly exceeds supply, which makes an engagement strategy to increase uptake unnecessary. Nonetheless, IRCC strongly agrees with the need for an engagement strategy on the BVOR program given the essential partnership with sponsors required for the program’s success.

IRCC also monitors and adjusts its sponsor engagement strategy as needed in order to ensure a fair and transparent process to identify appropriate BVOR cases, to enroll refugees in the program, and for sponsors to have access to those cases. As such, this recommendation was largely addressed through adjustments to the BVOR program immediately following the conclusion of the evaluation study.

However, in keeping with the spirit of this recommendation, IRCC is committed to strengthening the BVOR program as needed. In support of transparent and consistent enrollment practices, IRCC continually reviews criteria for the BVOR program in order to maintain flexibility and achieve a balance between sponsor interest and operational requirements. This enabled the Department to effectively adapt to the rapid and significant increases in demand for BVOR program since the start of the Syrian Refugee Initiative in November 2015.

IRCC has implemented an engagement strategy whereby the Department engages with sponsors and the Refugee Sponsorship Training Program to meet demand and modify candidacy criteria where required. At this time, activities to increase sponsorship uptake are not part of the strategy as they are not currently required.

Action #2a

IRCC will review the VOR program in order to assess its continued relevance in light of the BVOR program.

IRCC will update the operational guidance to ensure clarity between the BVOR and VOR programs, as required.

Accountability: ADM Strategic and Program Policy (RAB). Support: ADM Operations (IPMB, OMC and IR). Completion Date: December 2016.

Action #2b

IRCC will conduct annual reviews of the BVOR candidacy criteria and, as necessary, update candidacy criteria in order to maintain a flexible, responsive program with consistent enrolment practices. The annual review and any updated criteria will be shared with SAH Council at the Fall face to face NGO-Government Committee meeting.

Consultations undertaken through the BVOR Ad Hoc Committee will help inform these reviews.

IRCC will also share its annual BVOR plan and candidate criteria with sponsors via the Refugee Sponsorship Training Program; the annual plan will include numbers of expected referrals in an effort to enable forward planning.

Accountability: ADM Operations (IPMB). Support: ADM Operations (IR and OMC), ADM Strategic and Program Policy (RAB). Completion Date: December 2016.

Action #2c

As part of this strategy, IRCC will consult on and share its annual BVOR plan with sponsoring groups. Consultations with sponsors and the Refugee Sponsorship Training Program will continue to be conducted through the BVOR Ad Hoc Committee.

Accountability: ADM Strategic and Program Policy (RAB). Support: ADM Operations (IPMB, OMC and IR). Completion Date: December 2016.

Recommendation #3

IRCC should develop a strategy to improve privately-sponsored refugees’ awareness of the supports available to them during their first year in Canada.

Response #3

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

IRCC acknowledges the need to improve awareness of available supports and resources amongst privately sponsored refugees and their sponsors.

Ensuring that privately sponsored refugees are aware of available post-arrival supports to be provided by their sponsors and settlement services facilitates their transition to living in Canada. The Department is committed to increasing awareness both amongst sponsors and refugees as to where to go if there is a potential sponsorship breakdown situation.

Action #3

IRCC will develop a plan to improve awareness of the supports and settlement services available to privately sponsored refugees after arrival in Canada. In the development of this plan, IRCC will assess how best to raise awareness and will, accordingly, consider options to:

- Improve information sharing methods and resources (both pre- and post-arrival) to ensure refugees are aware of supports they are to receive from their sponsoring groups and from settlement services provider organizations, including the possibility of sharing of settlement planning information with refugees;

- develop a mechanism for improved client/sponsor monitoring of the PSR and BVOR program; and,

- clarify points of contact for PSRs and BVORs upon arrival and in the event of sponsorship breakdown.

Options for an awareness strategy will be presented to senior management and will be implemented, as required.

Accountability: ADM Operations (IPMB). Support: ADM Strategic and Program Policy (RAB and IFCRO), ADM Operations (OMC and CPO-W), Communications. Completion Date: March 2017.

Recommendation #4

IRCC should review its application intake management tools and approaches and implement measures to ensure timely decisions on PSR applications.

Response #4

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

IRCC recognizes the importance of timely processing, particularly with respect to refugee applications which involve uniquely vulnerable group. The Department further acknowledges the risks associated with extended wait times for PSR applicants as identified in this evaluation, including changes in family size and composition, and maintaining sponsor engagement.

Accordingly, IRCC is committed to reducing processing times for PSRs, as demonstrated by a number of measures implemented in recent years. Principally, this includes efforts to manage intake of applications and reduce backlogs by introducing caps on the number of applications submitted annually to overseas visa offices. Complementary efforts such as streamlining and centralizing processing and improving the quality of applications are also used. The Department also created a PSR Action Plan working group, which evaluates progress on the overall streamlining efforts for the PSR program.

Potential measures in this area will be considered recognizing that a reduction of refugee resettlement processing times are linked to the Department’s consideration of a multi-year immigration levels plan.

Action #4a

In support of this recommendation, IRCC will design an early and robust engagement strategy to ensure the sponsorship community is consulted on annual application intake management planning via SAH Council.

Accountability: ADM Strategic and Program Policy (RAB). Support: ADM Operations (IR, IPMB, and CPO-W). Completion Date: December 2016.

Action #4b

In addition, IRCC will review its existing application management tools and approaches, and develop options to support timely decision making, including a multi-year approach to levels and intake management to address persistent case inventories.

Program and/or policy changes will be implemented as needed.

Accountability: ADM Operations (OMC)/ADM Strategic and Program Policy (RAB). Support: ADM Operations (IR, IPMB, and CPO-W). Completion Date: June 2017.

Recommendation #5

IRCC should review the roles and responsibilities of branches involved in the Resettlement Programs and implement a strengthened governance structure to improve coordination.

Response #5

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

Successful delivery of Canada’s Resettlement programs requires coordinated efforts across a breadth of stakeholders within IRCC as well as other government departments, the sponsorship community and resettlement service providers across the country. Despite efforts to ensure the smooth management of the resettlement system, changes to the Canadian resettlement context, volumes, and evolving needs of stakeholders, have highlighted the need for clarified roles and responsibilities and a strengthened governance structure for these programs.

IRCC is committed to the continuing need for streamlined and effective horizontal governance, and concurs with the need for a governance framework which ensures appropriate accountabilities and facilitates coordination across participating organizations as well as timely decision making within all Resettlement programs.

Action #5

The Department will complete a review of the current governance structure to identify efficiencies and prepare options for adjustments, as needed.

IRCC will define roles and responsibilities of the branches within the Department as they relate to the design and delivery of Resettlement programs, and where possible, streamline points of contact.

Accountability: ADM Strategic and Program Policy/ADM Operations. Completion Date: December 2016.

Recommendation #6

IRCC should provide additional support to IRCC staff, sponsors and Resettlement Assistance Program Service Provider Organizations in its refugee processing network. In particular, IRCC should consider:

- increasing opportunities for training across CVOA, local IRCC office staff and Groups of Five and Community Sponsors;

- expanding the sharing of best practices across CVOA and local IRCC offices; and

- developing a tool to support the automatic calculation of RAP income support.

Response #6

IRCC agrees with this recommendation.

The Department is committed to ensuring adequate training and learning tools are available to all staff in its refugee processing network, and acknowledges the need to build on its current suite of available resources and training options, which include classroom and online training, as well as operational manuals, to ensure effective delivery of its Resettlement programs.

IRCC acknowledges that sharing of best practices across CVOA and local offices helps the Department to learn from successes and improve program delivery. The Department also acknowledges the importance of providing the necessary training to officers to ensure consistent program delivery.

In support of this recommendation, the Department has begun work on the development of an automatic income support calculation tool based on the findings of a review conducted by the Internal Financial Controls team in 2014.

Further, the Department has recently published an updated operational manual which serves as the main functional guidance used by local IRCC staff, and the office responsible for processing all privately-sponsored refugee applications as developed a set of standard operating procedures to guide their work.

Action #6a(i)

The Department will fund specific support, training and outreach to the Group of Five and Community Sponsors via the Refugee Sponsorship Training Program (RSTP).

Accountability: ADM Operations (IPMB). Support: ADM Strategic and Program Policy. Completion Date: December 2016.

Action #6a(ii)

IRCC will enhance training opportunities for CVOAs, including through improvements to the refugee training program for officers in missions abroad.

Accountability: ADM Operations (IR). Support: ADM Strategic and Program Policy (RAB). Completion Date: December 2016.

Action #6b

The Department will implement new ways of sharing best practices across its local offices, CVOA and between National Headquarters and regional offices.

Accountability: ADM Operations (IPMB, and for CVOA, IR). Support: ADM Operations (OMC – Local Offices). Completion Date: March 2017.

Action #6c

IRCC will develop an automatic income support calculation tool that will ultimately standardize forms, tools and processes for the RAP income support payment process.

Accountability: ADM Operations (IPMB)/ADM Finance. Support: ADM Strategic and Program Policy (RAB). Completion Date: Identification of the system requirements and initial building and testing – March 2017; Implementation of the new system – March 2018.

1. Introduction

1.1 Purpose of the Evaluation

This report presents the findings of the evaluation of Immigration, Refugee and Citizenship Canada’s (IRCC) Refugee Resettlement Programs and the Resettlement Assistance Program which covered the period of 2010 to 2015. The evaluation was conducted in fulfillment of requirements under the Treasury Board Policy on Evaluation and section 42.1 of the Financial Administration Act.Footnote 1 The evaluation examined program relevance and performance in accordance with the 2009 Treasury Board Secretariat Directive on the Evaluation FunctionFootnote 2.

This Executive Evaluation Report provides the high level summary of the evaluation. An Extended Evaluation Report of the evaluation of IRCC’s Refugee Resettlement Programs is available upon request.

1.2 Brief Program Profile

Canada’s Refugee Resettlement Programs are part of Canada’s humanitarian tradition to help find solutions to prolonged and emerging refugee situations. Resettlement is how Canada selects refugees abroad and supports their health, safety, and security as they travel to and integrate into Canadian society.Footnote 3 Resettled refugees can be admitted to Canada via one of the following three resettlement programs.

- Government-Assisted Refugees (GAR) are usually referred by the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR) or other designated referral agencies and supported by the Government of Canada who then provides initial resettlement services and income support for up to one year.Footnote 4 The introduction of the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) in 2002 placed a greater emphasis on selecting GARs based on their protection needs rather than on ability to establish in Canada. As a result, GARs often carry higher needsFootnote 5 than other refugee groups. GARs are also eligible to receive resettlement services (i.e., reception at port of entry, temporary accommodation, assistance in finding permanent accommodation, basic orientation, links to settlement programming and federal and provincial programs) provided through a service provider organization that signed a contribution agreement to deliver these services under IRCC’s Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP).

- Privately Sponsored Refugees (PSR) are sponsored by permanent residents or Canadian citizens via one of three streams: through a Sponsorship Agreement Holder (SAH) that is an incorporated organization that has signed a sponsorship agreement with IRCC for the purpose of submitting sponsorship cases on a regular basisFootnote 6; through a Group of Five (G5) that consists of a temporary group of five or more Canadian citizens or permanent residents that will sponsor one or a few cases and will act as guarantors; or through Community Sponsors (CS) that are organizations that do not have formal agreements with IRCC as these organizations will sponsor only once or twice. In each of these PSR streams, sponsors provide financial support or a combination of financial and in-kind support to the PSR for twelve months after arrival, or until refugees are able to support themselvesFootnote 7, whichever comes first. Refugees in the PSR program are intended to be resettled in addition to those arriving under the GAR program, as the PSR program allows Canadians to get involved in refugee resettlement and offer protection space over and above what is provided directly by the government (i.e., principle of additionality).

- Blended Visa Office-Referred (BVOR) refugees are referred by the UNHCR or other designated referral agencies and identified by Canadian visa officers for participation in the BVOR program based on specific criteria. The BVOR program evolved from the Visa Office-Referred (VOR) program in 2013.Footnote 8 The refugees’ profiles are posted to a designated BVOR website where potential sponsors (SAHs and CGs) can select a refugee to support. BVOR refugees receive up to six months of RAP income support from the Government of Canada and six months of financial support from their sponsor, plus start-up expenses. Private sponsors are responsible for BVOR refugees’ social and emotional support for the first year after arrival, as BVOR refugees are not eligible for RAP services.

This evaluation also examined the Resettlement Assistance Program (RAP). RAP funds the provision of immediate and essential services (i.e., reception at port of entry, temporary accommodation, assistance in finding permanent accommodation, basic orientation, and links to settlement programming and federal and provincial programs) to GARs and other eligible clients through service provider organizations. These resettlement services are provided for up to six weeks. Similarly to BVOR refugees, GARs also receive monthly income support (based on provincial social assistance rates) which is a financial aid that is intended to provide monthly income support entitlements for shelter, food and incidentals. In the case of GARs, this income support is provided for up to one year or until they become self-sufficient, whichever comes first.Footnote 9

Over the past five years, the number of resettled refugees admitted to Canada, excluding Quebec,Footnote 10 has increased by 7% from 9,809 in 2010 to 10,466 in 2014. Across all years, excluding 2013, more GARs were resettled as compared to PSRs. BVOR refugees accounted for a small proportion of refugees from 2013 onward, as the program was implemented in that year. From 2010 to 2014, overall admissions are shown in Table 1.

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2010-2014 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAR | 5,460 (56%) | 5,646 (52%) | 4,282 (54%) | 4,726 (45%) | 6,352 (61%) | 26,466 (53%) |

| PSR | 4,349 (44%) | 5,183 (48%) | 3,694 (46%) | 5,565 (53%) | 3,946 (38%) | 22,737 (46%) |

| BVOR Refugees | - | - | - | 145 (1%) | 168 (2%) | 313 (1%) |

| Total: Admissions | 9,809 | 10,829 | 7,976 | 10,436 | 10,466 | 49,516 |

Source: Global Case Management System (GCMS)/Field Operations Support System (FOSS).

A detailed profile of the Refugee Resettlement Programs is provided in the Extended Evaluation Report.

1.2.1 Characteristics of Resettled Refugees (2010-2014)

The following characteristics of resettled refugees admitted from 2010 to 2014 were observed:

- Overall admissions: 26,466 GARs (53%), 22,737 PSRs (46%) and 313 BVOR refugees (1%).

- Gender: Slightly more PSRs were male compared to GARs and BVOR refugees (GARs male 50%; PSRs male 54%, BVOR male 52%).

- Proportion of adults: A smaller proportion of adults was admitted under the GAR category (GAR 61%, PSR 70%, BVOR refugees 69%).

- Knowledge of official languageFootnote 11: More PSRs reported knowing at least one of the official languages than either GARs or BVOR refugees (GAR 26%, PSR 38%, BVOR refugees 14%).

- Education levelFootnote 12: GARs more commonly had nine or fewer years of education compared to PSRs and BVOR refugees (GAR 61%, PSR 48%, BVOR refugees 54%).

- Country of citizenship (top three): The top three countries of citizenship varied by program GAR: Iraq, Bhutan, Somalia; PSRs: Iraq, Eritrea, Ethiopia and BVOR refugees: Myanmar, Eritrea, Iran.

- Case composition (% single adult): Fewer GAR cases were composed of a single adult (GAR 47%, PSR 57%, BVOR refugees 56%).

- Intended province of destination: The three programs had very similar distribution in Canada, with the majority intending to settle in Ontario, Alberta, Manitoba, and British Columbia.

- Family Composition: Cases most commonly included a single adult (representing 52% of the cases), or two adults with children (representing 21% of cases). PSRs and BVOR refugees, more commonly arrived as a single adult as compared to GARs (57%, 56%, and 47%, respectively).

2 Methodology

2.1 Evaluation Approach

The evaluation scope and approach were determined during a planning phase, in consultation with IRCC branches involved in the design, management and delivery of the Refugee Resettlement Programs. The terms of reference for the evaluation was approved by IRCC’s Departmental Evaluation Committee in September 2014, and the evaluation was conducted by the IRCC evaluation division with the support of an external contractor from January 2015 to November 2015.

2.2 Evaluation Scope

The evaluation assessed the issues of relevance and performance of the Refugee Resettlement Programs for the period between 2010 and 2015, and was guided by the program logic model, which outlines the expected immediate and intermediate outcomes for the program (see Appendix A).Footnote 13 Evaluation questions were developed to address the Treasury Board Secretariat core issuesFootnote 14, and are presented in Table 2. Performance indicators were identified for each evaluation question to form the evaluation framework for the study.

In November 2015, the Government of Canada committed to admitting 25,000 Syrian refugees by February 2016. The evaluation did not examine the impacts, operations, or results of the Syrian Refugee Initiative. A Rapid Impact Evaluation will be conducted separately on the results of the Syrian Refugee Initiative.

Table 2: Evaluation Questions

Relevance

Is there an ongoing need for Canada to provide protection and resettlement assistance to refugees?

Are GAR/PSR/BVOR and the RAP aligned with departmental strategic outcomes and Government of Canada priorities?

Are the refugee resettlement programs and the RAP consistent with federal roles and responsibilities?

Performance – Management Outcomes

Has IRCC addressed the program issues identified in the previous PSR and GAR/RAP evaluations related to: PSRs (Monitoring activities, Application intake and guidelines)/GARs/RAP (Information sharing mechanisms, Changing needs of GARs, Adequacy of housing and income support)?

Have policy advice and directives supported effective program delivery?

Are stakeholder relations effectively supporting program delivery and protection priorities?

Do Canadians and permanent residents engage in supporting resettlement?

Are the selection, matching and processing efficient and effective for the resettlement programs?

- Do SPOs and sponsors have sufficient information to meet resettled refugees’ needs upon arrival?

- Are resettled refugees’ arrivals safe, and GAR arrivals coordinated?

Are the immediate and essential needs of resettled refugees met?

- To what extent is the resettlement assistance provided timely, accessible, useful and client- focused?

- Are resettled refugees receiving social support that responds to their needs?

Are resettled refugees linked to IRCC-funded settlement services, other government and specialized services?

Do refugees have the knowledge, skills and means to live safely and independently?

- Have resettled refugees developed social networks and connections with the broader community?

Have the refugee resettlement programs contributed to uniting refugee families in Canada?

Does Canada contribute to international protection efforts and protects refugees?

- To what extent national population priorities and targets take into account international protection priorities, protection needs and resettlement capacities in Canada?

Have there been any unintended impactsFootnote 15 associated with the refugee resettlement programs?

Performance - Resource Utilization

Are there approaches to resettled refugees selection and processing that could lead to a more efficient process?

Are there alternative RAP design and delivery options that would better facilitate the achievement of improved outcomes?

2.3 Data Collection Methods

Multiple lines of evidence were used to gather qualitative and quantitative data from a wide range of perspectives, including program managers, stakeholders and clients. These lines of evidence included the following:

- Document Review: IRCC, Non-Governmental Organization (NGO) and other documentation.

- Key Informant Interviews: IRCC representatives (17), Other Stakeholders (UNHCR, International Organization for Migration (IOM), Canadian Council for Refugees (CCR), Refugee Sponsorship Training Program (RSTP), and SAH Council) (6), Provinces/Territories (4).

- Program Data Analysis: Global Case Management System (GCMS), Longitudinal Immigration Database (IMDB), Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (iCARE), and Financial Data.

- Site visits to Matching Centre and Centralized Processing Centre in Winnipeg: 4 interviews.

- Inland Case Studies in Vancouver, Calgary/Lethbridge, Winnipeg, Toronto and Halifax, which included:

- Interviews with Resettlement Assistance Program Service Provider Organizations (RAP SPO) (14), SAHs (6), local IRCC (10), and SPO stakeholders (including health providers and community partners) (10)

- Focus groups with GARs (8) and PSRs (5)

- File Review

- International Case Studies in Amman, Ankara, Nairobi, and Singapore, which included:

- Interviews with IRCC Canadian-based staff (13), Locally Engaged Staff (7), UNHCR (6), IOM (5), Global Affairs CanadaFootnote 16 (1), and Other Referral Agencies (2)

- File Review

- Follow-up focus groups in Edmonton and Ottawa with GARs, PSRs as well as CG and G5 sponsors.

- SurveysFootnote 17

| Respondent Group | Survey Completions | Response Rate | Margin of Error (95% confidence level) |

|---|---|---|---|

| RAP SPO | 20 | 80%Table 3 footnote * | ±10% |

| SAH | 43 | 47%Table 3 footnote * | ±11% |

| GAR | 810 | 76%Table 3 footnote ** | ±3% |

| PSR | 541 | 78%Table 3 footnote ** | ±4% |

| BVOR Refugee | 20 | 74%Table 3 footnote ** | ±21% |

These lines of evidence are presented in Appendix B, and more detailed information on the data collection methods used in the evaluation is provided in the Extended Evaluation Report.

The following scale was used for reporting qualitative interview results:

| Scale | Description |

|---|---|

| All | Findings reflect the views and opinions of 100% of the interviewees. |

| Majority/Most | Findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 75% but less than 100% of interviewees. |

| Many | Findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 50%, but less than 75% of interviewees. |

| Some | Findings reflect the views and opinions of at least 25%, but less than 50% of interviewees. |

| Few | Findings reflect the views and opinions of at least two respondents, but less than 25% of interviewees. |

2.4 Limitations and Considerations

Some limitations were noted in relation to the early implementation of the BVOR Program (i.e., data only available from 2013), and limited access to information from both PSRs and BVOR sponsors. Various mitigation strategies were used to address the limitations and to ensure that the evaluation presented reliable information to support strong findings. These limitations and their corresponding mitigation strategies are described in more detail in the Extended Evaluation Report.

The 2015 Syrian Refugee Initiative was not taken into consideration for the evaluation. The Initiative began in November 2015, after the data collection phase of the evaluation had been completed. As those admitted after November 4th, 2015 had different experiences with the GAR, PSR, BVOR and RAP programs, (e.g., processing times were expedited, immigration loans were waived, etc.), the refugees admitted under the Syrian Refugee Initiative were not taken into account. For these reasons, administrative data for 2015 was not the most recent year used for comparative purposes, in order to avoid reporting on exceptional events.

Overall, the evaluation design employed numerous qualitative and quantitative methodologies. The different lines of evidence were complementary and reduced information gaps, and generally, the results converged towards common and integrated findings. The triangulation of the multiple lines of evidence, along with the mitigation strategies used in this evaluation are considered sufficient to ensure that the findings are reliable and can be used with confidence.

3 Key Findings: Relevance

3.1 Continued Need for the Resettlement Programs

Finding #1: There is a continued need to provide protection to refugees and resettlement assistance upon arrival.

Several lines of evidence confirmed a strong need for the resettlement of refugees. Canada’s humanitarian commitment to resettle refugees allows Canada to continue to provide protection to those in needFootnote 18 and allows Canada to help share the burden for countries of asylum.Footnote 19 Between 1980 and 2015, Canada helped other countries alleviate this burden by resettling 333,303 GARs, 267,587 PSRs and 565 BVOR refugees, totalling 601,436 resettled refugees. The UNHCR estimates that global resettlement needs will exceed 1,150,000 persons in 2016, a 22% increase over 2015 estimates, which is largely due to unrest in Syria and parts of Africa.Footnote 20

Most interviewees believed that resettlement was a necessary and durable solution for refugees for whom there is no reasonable prospect of voluntary repatriation or local integration. International case study interviewees confirmed that local integration options were limited: though respondents noted that some host countries had provided space for integration, resources were strained by the high refugee demand, as conflicts in many areas of the world continue.

In addition, resettlement assistance services are needed for refugees, as they have specific needs which differ from newcomers being admitted under other immigration categories. Refugee populations entering Canada have diverse needs. Some refugees are arriving from urban areas and are able to use public transportation and modern technologies (such as banking, computers) whereas other refugees are coming from rural areas or refugee camps and had less exposure to these type of activities. Research and documentation has shown that refugees are known to be coming from difficult situations, and significant barriers are often experienced when accessing traditional settlement services.Footnote 21 This was confirmed through many interviewees who identified various services (e.g., reception, orientation and needs assessments, financial assistance, settlement services, etc.) as being needed by refugees.

3.2 Alignment with Departmental and Government of Canada Objectives

Finding #2: Refugee resettlement programs align with Government of Canada and IRCC priorities to support humanitarian policy objectives.

Canada’s priorities to support humanitarian objectives originates from both the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees and the 1967 Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees,Footnote 22 to which Canada is a signatory. These international agreements form the basis of current international refugee protection and establish the minimum standards for the treatment of refugees. Canada’s ongoing international efforts in support of these agreements has positioned it as a leader in providing resettlement options for refugees with the purpose of saving lives and offering protection for the displaced and in supporting integration. For example, many key informant interviewees indicated that Canada has been a member of various UNHCR working groups including the Core Working Group on Syria. Given that participation in international resettlement efforts is not mandatory, these actions reaffirm the Government of Canada’s commitment to prioritizing international refugee resettlement to support humanitarian objectives. It is also in alignment with IRCC’s departmental strategic objectives (Strategic Outcome 2: Family and humanitarian migration that reunites families and offers protection to the displaced and persecuted; Strategic Outcome 3: Newcomers and citizens participate in fostering an integrated society).

The emphasis on refugee resettlement as a priority for Canada was strengthened in November 2015. The new Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship’s Mandate Letter from the Prime Minister specifically indicated that refugees were a “top priority”, and committed to efforts to resettle 25,000 refugees from Syria.Footnote 23

Despite documentation demonstrating alignment of the resettlement programs, there is some evidence that suggests that the department’s prioritization of support for GARs through RAP income support is debateable as recommendations to change RAP income support have been made numerous timesFootnote 24, and limited action has been taken to date.

3.3 Consistency with Federal Roles and Responsibilities

Finding #3: Resettlement programs are consistent with federal roles and responsibilities in offering humanitarian protection.

It was felt by many key informants that refugee resettlement should remain within the federal purview. They also felt that federal oversight of resettlement programs was appropriate as it ensured the delivery of consistent services across Canada.

As the federal government has committed to supporting and resettling GARs, key informants noted that the federal government has a responsibility to ensure services are adequately and consistently provided across Canada when refugees arrive.

A few key informants questioned two aspects of the federal role related to RAP. First, interviewees questioned whether RAP income support for refugees should be a federal responsibility as RAP income support is designed to mirror social assistance provided by the provinces and as in a few regions, RAP income support was lower than provincial social assistance. Second, these key informants and some SPO case study participants were concerned that the use of social assistance rates as a benchmark for income support was inadequate. This is discussed in greater detail in Section 5.9.

4 Key Findings: Performance – Management Outcomes

4.1 Recommendations Identified in Previous Evaluations

Finding #4: Numerous steps have been taken by IRCC to address recommendations identified in previous GAR-RAP and PSR evaluations, but certain recommendations remain outstanding.

4.1.1 Work Completed, Planned or Underway

The evaluation examined work completed, planned or underway to address recommendationsFootnote 25 for the improvement of the GAR-RAP and PSR programs made in previous departmental evaluations.Footnote 26

A primary concern raised in the 2007 PSR summative evaluation was the efficiency of application processing, as long processing times and high refusal rates were noted. In addition, inventories were created as the number of PSR applications exceeded the targeted number of PSRs under the Annual Immigration Level Plan. Examples of efforts to create efficiencies in PSR processing and address inventories included:

- the introduction of Centralized Processing Office-Winnipeg (CPO-W) in April 2012;

- regulatory changes in 2012 to the PSR Program requiring that prospective G5 and CS PSRs must be recognized as refugees by either the UNHCR or a foreign state, and must submit a complete application; and

- introduction of annual global caps and regional sub-caps since January 2012 to limit the number of applications SAHs can submit to Visa Offices in Islamabad, Nairobi, Cairo, and Pretoria.

The 2011 GAR-RAP evaluation suggested that additional information sharing platforms and tools were needed. Some actions taken to address the recommendations included increasing training for Canadian Visa Offices Abroad (CVOA) staff, and implementation of the eMedical system.Footnote 27

4.1.2 Recommendations Not Yet Addressed

The following recommendations from the previous evaluations (PSR and GAR-RAP) have not been addressed, due primarily to resourcing constraints and shifting priorities. These areas are explored further in the evaluation and also form part of this report’s recommendations.

Current monitoring activities are insufficient (PSR)

- A lack of monitoring activities for the PSR program, including whether settlement plans have been implemented, remained an issue despite being identified in the 2007 PSR Evaluation.

- Centralization of PSR application processing in CPO-W had not improved monitoring, as CPO-W staff and local IRCC office staff were not clear on the extent of their monitoring responsibilities.

Enhance or develop information sharing mechanisms (GAR and RAP)

- Despite piloting a program to transfer medical records to refugees in a sealed envelope upon their arrival in Canada, there are still barriers to sharing medical information with relevant partners and health practitioners in Canada.

- Although multiple actions were taken to address the information sharing regarding the GAR and RAP programs, there are still gaps in sharing best practices across different offices, both internationally and domestically.

Address insufficiency of RAP income support

- Finally, concrete actions to address the adequacy of housing and RAP income support levels have not been taken and the RAP income support is still insufficient to meet essential needs for GARs.Footnote 28

4.2 Planning and Target Setting

Finding #5: The combination of multi-year commitments and yearly targets provide opportunities for both planning and flexibility to meet emerging needs; however, there are challenges related to operational planning and the implementation of yearly targets.

4.2.1 Target Setting

Every year, the Minister of Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship tables the Annual Report to Parliament on Immigration on or before November 1st. The report includes the Immigration Levels Plan that projects how many people will be admitted to Canada as permanent residents for the following year. The Immigration Levels Plan is an important strategic tool because it lays out the distribution of admissions across all immigration categories, including the number of refugees to be admitted under the GAR, PSR, and BVOR programs. This plan is developed in consultation with other federal departments, as well as provinces and territories. Each program has a range (a low and high end) as well as a specific target for each calendar year.

| Low | High | Target | Admitted | % of Target | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAR | |||||

| 2010 | 7,300 | 8,000 | 7,500 | 7,264 | 96% |

| 2011 | 7,400 | 8,000 | 7,500 | 7,364 | 98% |

| 2012Table 5 footnote *† | 7,500 | 8,000 | 7,500 | 5,430 | 72% |

| 2013 | 6,800 | 7,100 | 7,100 | 5,756 | 81% |

| 2014 | 6,900 | 7,200 | 7,100 | 7,573 | 107% |

| PSR | |||||

| 2010 | 3,300 | 6,000 | 4,500 | 4,833 | 107% |

| 2011 | 3,800 | 6,000 | 4,500 | 5,582 | 124% |

| 2012Table 5 footnote *† | 4,000 | 6,000 | 5,500 | 4,220 | 77% |

| 2013 | 4,500 | 6,500 | 6,300 | 6,277 | 100% |

| 2014 | 4,500 | 6,500 | 6,300 | 4,559 | 72% |

| BVOR RefugeeTable 5 footnote **† | |||||

| 2010 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2011 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2012Table 5 footnote *† | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2013 | 200 | 300 | 200 | 153 | 77% |

| 2014 | 400 | 500 | 500 | 177 | 35% |

Sources: Annual Report on Immigration Levels Plan, GCMS/Field Operations Support System (FOSS).

The numbers of GARs admitted did not meet the low end of the range for all years except in 2014. However, in 2014 it exceeded the high end (107%). The number of PSRs admitted did not reach the target in 2012 (77%), reached target in 2013 (100%), and remained below target in 2014 (72%), but were all within the allocated ranges. BVOR refugees were below target in 2013 (77%) and 2014 (35%).

4.2.2 Issues with Target Setting

Key informants noted several issues associated with target setting. First, for GARs, late target announcementsFootnote 29 to CVOA and UNHCR caused issues affecting all phases of the resettlement process, from the referral stage to resettlement services in Canada (e.g., shortened time to process and refer refugees, concentration of departure and arrival of refugees in the summer and late December which increased the travel costs and delayed the provision of certain services).

Secondly, for PSRs, the SAH community stressed that they had not been sufficiently consulted on BVOR refugee targets, and did not have resources to promote the program among their constituents. Although the principle of additionality is not part of the PSR program theory, private sponsors felt that the PSR program was contradicting the principle of additionalityFootnote 30, as in 2013, as the number of admitted PSRs was higher than the number of GARs.

4.2.3 Use of Multi-year Commitments

Multi-year commitments, which were used by IRCC between 2010 and 2014, are a comprehensive approach to resettlement planning for a particular refugee group over a specified period of time.Footnote 31 Establishing multi-year commitments offered several potential advantages to Canada, including enhanced collaboration and coordination with other countries, coordinated referral requests with UNHCR, and efficiency savings in terms of better meeting the needs of large groups and potential improvements in processing time.Footnote 32 Multi-year commitments were expected to improve planning and resource utilization internally at IRCC and among external partners such as the UNHCR, IOM, and RAP SPOs.

A few key informants noted that the multi-year commitments did not eliminate or reduce the resettlement program’s overall flexibility to respond to international priorities, as the proportion of refugees to be resettled as part of multi-year commitments accounted for about half of GARs levels. For example, in 2011, only 54% of GARs were resettled based on multi-year commitments, with the remaining 46% coming from a non-multi-year target population.

5 Key Findings: Performance - Program Outcomes

5.1 Canada’s Contribution to International Protection Efforts

Finding #6: Canada has effectively contributed to international protection efforts and was one of the top three resettlement countries in terms of volume between 2010 and 2014.

Among UNHCR’s member states, Canada is a leader in resettling refugees. Along with the United States and Australia, Canada was in the top three resettlement countries in terms of volume resettled between 2010 and 2014, and also ranked highly in terms of per capita resettlement in 2014 (see Table 6).Footnote 33 In 2014, Canada received the second highest number of refugee referrals (7,233), following the United States (48,911), and third highest overall between 2010 and 2014. Canada has also played a substantial role in the UNHCR emergency resettlement program: between 2010 and 2012, Canada accepted 100 emergency casesFootnote 34 (264 refugees) for resettlement, which amounted to 10% of all emergency referrals worldwide.Footnote 35

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | Total | % | Per Capita (2014)/Rank | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | 54,077 | 43,215 | 53,053 | 47,875 | 48,911 | 247,131 | 70.90% | 6,384/6 |

| Australia | 5,636 | 5,597 | 5,079 | 11,117 | 6,162 | 33,591 | 9.64% | 3,636/1 |

| Canada | 6,706 | 6,827 | 4,755 | 5,140 | 7,234 | 30,662 | 8.80% | 4,718/3 |

| Sweden | 1,789 | 1,896 | 1,483 | 1,832 | 1,812 | 8,812 | 2.53% | 5,177/4 |

| Norway | 1,088 | 1,258 | 1,137 | 941 | 1,188 | 5,612 | 1.61% | 4,117/2 |

| Germany | 457 | 22 | 323 | 1,092 | 3,467 | 5,361 | 1.54% | 23,945/12 |

| Finland | 543 | 573 | 763 | 665 | 1,011 | 3,555 | 1.02% | 5,310/5 |

| United Kingdom | 695 | 424 | 989 | 750 | 628 | 3,486 | 1.00% | 98,831/18 |

| New Zealand | 535 | 477 | 719 | 682 | 639 | 3,052 | 0.88% | 6,911/7 |

| France | 217 | 42 | 84 | 100 | 378 | 821 | 0.24% | 167,278/19 |

| Other Resettlement Countries | 1,171 | 1,318 | 867 | 1,217 | 1,901 | 6,474 | 1.86% | N/A |

| Total World Resettlement | 72,914 | 61,649 | 69,252 | 71,411 | 73,331 | 348,557 | 100.00% | N/A |

Source: UNHCR (2015) UNHCR Projected Global Resettlement Needs; United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2013) World Population Prospects: The 2012 Revision, DVD Edition.

In addition, a few interviewees from case studies (including domestic and international) reported that Canada has set an international example insofar as it influenced other resettlement countries to increase the number of women at risk and LGBTIQFootnote 37 refugees they receive, as well as to increase their use of multi-year commitments. A few key informants also suggested that Canada’s international representatives took a leadership role through the chairing of various international committees (e.g., Syria Core Group, 2013 Annual Tripartite Consultation on Resettlement)Footnote 38 and by championing the needs of vulnerable populations within these international committees.

5.2 Program Delivery – Supports and Challenges

5.2.1 Policy, Guidance and Procedures

Finding #7: While numerous policies and tools exist to support program delivery, gaps were observed regarding the clarity of the guidance for the BVOR program, and the monitoring around the PSR program.

Several advances have been made since 2010 on policies and procedures to improve clarity and efficiency in program delivery. These include a new Sponsorship Agreement between SAHs and IRCC in 2014, global and regional sub-caps on PSR SAH applications, performance measurement frameworks, and the introduction of CPO-W. Despite these advancements, key informants, international case study participants, and domestic case study participants noted confusion with some of the resettlement policies and procedures.

Although the introduction of the BVOR program in 2013 was followed by operational bulletins and modifications to manuals, at the time of the evaluation, CVOA officers had not received sufficient guidelines and training regarding the implementation of the BVOR program. Interviewees from case studies (including domestic and international) felt that the BVOR procedures and selection criteria that should be used to identify potential refugees to be part of the program were unclear. This lack of clarity on procedures led to inconsistencies in how BVOR refugees are included in the program, and in how they are processed internationally. For example, international site visits findings highlighted that as there was no guidance available on BVOR enrolment, some potential BVOR refugees were asked (in person) by a CVOA officer if they wanted to participate in the program, some asked (in writing only) if they would consider being sponsored through a check box on a form with little explanation, while others were automatically entered in the program without being informed (not asked at all). As a result, this lack of clarity led to inconsistency in enrolling potential BVOR refugees in the program. Additionally, despite criteria that BVOR refugees should have low medical needsFootnote 39, in some CVOA, BVOR refugees were referred before medical exams were completed.

In addition, a review of the current guidance showed that it does not clearly distinguish between BVOR and VOR refugees.Footnote 40 Some SAHs perceive this program as a branch of the PSR program and as a result, they interpret the BVOR program as contravening the Principles of Naming and Additionality. Furthermore, there is a misalignment between one of the criteria that UNHCR uses to refer cases to Canada (i.e., having family in Canada) and the BVOR program selection criteria (i.e., to be considered one should not have family links in Canada) which reduces the eligible pool of potential BVOR refugees.

Although IRCC has guidance indicating that local IRCC office staff are responsible for the monitoring of sponsors and sponsored refugees,Footnote 41 domestic case study interviewees revealed that there are no formal mechanisms to implement the monitoring of sponsors’ activities and very little resources were available in the regions. Further, some CPO-W staff and local IRCC office staff indicated they were not clear on what procedures to follow in the event of sponsorship breakdown or when the SAHs, CS, or G5 failed to comply with the settlement plan. In addition, as there are no requirements for either IRCC or sponsors to share the settlement plan with PSRs, PSRs may not know what their sponsors have committed to provide them with in the first year.

Other areas of confusion related to the lack of supporting policy guidance and procedures included how CVOA should operationalize high medical needs cases, and how to apply the 5% cap on high medical needs among GARs. Due to varying decisions on coverage for special allowances, there was also uncertainty among local IRCC staff regarding coverage for special allowances under RAP income support, even though eligibility criteria for special allowances is outlined in an internal manual.Footnote 42

5.2.2 Tools

Finding #8: There are issues with the tools to support program delivery, most notably, GCMS and a lack of a RAP income support calculation tool.

Despite the availability of many tools to support program delivery, issues were identified with GCMS. Some of these issues noted by CVOA staff included functionality issues, frequent speed issues, a lack of program stability, disruptions or problems arising with new releases or updates, and the inability to print forms.Footnote 43 Some CVOA staff also noted that they had problems reading officer notes in GCMS and tracking statistics on inventories and specific groups of applicants, and then had to rely upon parallel, office-specific programs to manage inventories and support processing.

During domestic case studies, IRCC staff noted that calculation of income support for GARs/BVOR refugees was done manually, and varied by jurisdiction. It was felt that IRCC could develop an online form that could automatically calculate required income support based on family size, jurisdiction, and/or special circumstances.

5.2.3 Training

Finding #9: Training available for IRCC staff, sponsor and RAP SPOs was insufficient.

While refugee program-specific training was available for IRCC staff both internationally (e.g., visa officers) and domestically (e.g., local RAP officers) as well as for SAHs and private sponsors (through the RSTP), several issues with training, both internationally and domestically, were reported.

- Variances in on-the-job training by CVOA resulted in inconsistencies in applied practices.

- Refugee-specific training for CVOA staff was reported, by a few international case study interviewees, as oversubscribed; thus, not all officers had access to this training.

- CVOA officers noted that training on using advanced reporting and management functions of GCMS was not provided.

- A few CVOA officers expressed a desire for counselling services to help staff cope with the high level of stress of refugee processing.

- Additionally, CVOA officers and Locally Engaged Staff (LES) also noted that the training for LES was very limited and could be expanded.

Despite the availability of local RAP officer training, some key informants noted that training for local RAP officers was insufficient (i.e., training was too short and it did not prepare them properly). Moreover, some key informant interviewees, domestic case studies and sponsor focus group participants suggested that more training was needed for G5s and sponsors who were not affiliated with a SAH to ensure they correctly completed the PSR application forms. As noted in the 2010 GAR-RAP Evaluation, CVOA and local IRCC staff indicated they would welcome opportunities to share best practices across different offices, which could potentially serve as a new method of training.

5.3 Coordination with Stakeholders

Finding #10: While mechanisms are in place to coordinate program delivery, internal stakeholders expressed the need for greater coordination and governance within IRCC.

5.3.1 Internal Coordination and Governance

IRCC key informants noted the existence of mechanisms to coordinate and support program delivery within the department at both the international and domestic levels which included working groups and operational guidance and support. Most key informants believed that these mechanisms worked well and did not suggest the need for additional coordination mechanisms.

Despite the existence of these mechanisms, interviewees explained that governance issues impacted the coordination of Resettlement and RAP programming within IRCC. Even with the existence of an operational bulletin on the matter, several key informants explained that branches often did not know each other’s respective roles and responsibilities due to the large number of IRCC branches involved in the resettlement programming from operations and policy sectors.Footnote 44 This lack of clarity regarding roles and responsibilities resulted in a fragmented approach to resettlement, resulting in an uncoordinated approach to delivery.

In addition to the challenges affecting governance, CVOA and local IRCC office staff noted several coordination challenges affecting day to day operations, in particular, concerns with delays in responses to case-specific questions between National Headquarters (NHQ) and local IRCC office staff, CVOA and CPO-W and CVOA and NHQ. In particular, local IRCC offices noted that between 2010 and 2015, local IRCC office staff lost a central point of contact from which to request and receive information from NHQ.

In addition, domestic site visits raised the issue that during this period of change, the RAP officers no longer had the authority to make operational decisions on RAP expenditures. This issue was noted through an example, in which requests for small amounts of funds (e.g., $40) for special allowances for income support took an extended period of time to be approved, as multiple players in local IRCC offices and NHQ were involved.

5.3.2 External Coordination

Finding #11: Overall external stakeholders indicated coordination methods were sufficient; however, some expressed a need for increased consultations.

IRCC had numerous mechanisms in place to coordinate and communicate with external stakeholders such as UNHCR, IOM, SAHs, RAP SPOs, provinces/territories, and NGOs, including UNHCR Core Groups, monthly meetings with SAH Council, and regular meetings and consultations with provincial and territorial representatives.

Most external key informants agreed that the communication and coordination methods in place were sufficient. UNHCR and SAH Council key informants believed that Canadian officials were accessible and noted that IRCC communication activities were effective and helpful. SAH Council key informants noted that they are included in target and sub-cap discussions. RSTP key informants noted that IRCC coordinates well through information exchanges and that they were also able to contact IRCC with questions from sponsors that they otherwise could not answer. In turn, RSTP shared the information provided by IRCC with the sponsor community.

Key informants, however, did provide some suggestions on how coordination could be further improved. For example, certain external stakeholders expressed a desire to play a larger role in policy consultations regarding logistics of traveling. Other stakeholders indicated that the dissemination of the refugee target numbers for each CVOA could take place earlier.

Provincial government representatives suggested that increased external collaboration with IRCC on the number of PSRs and GARs arriving, their destinations, and their needs could improve management of community capacity. RAP SPOs noted that their responses to the RAP SPO Capacity SurveyFootnote 45, in terms of the number and profile of refugees they could support, did not seem to be taken into account when IRCC assigned cases to their organizations.

5.4 Canadians’ Engagement in Supporting Resettlement and Contribution to Uniting Refugee Families

5.4.1 Application Submission

Finding #12: Canadians continue to demonstrate active engagement in refugee sponsorship through SAHs and G5s; however, less engagement has occurred through the BVOR program.

The volume of PSRs being sponsored is an indicator of the continued engagement of Canadians and permanent residents towards supporting resettlement. Between 2010 and 2014, 39,694 PSR and 808 BVOR refugees had been referred for sponsorship. The PSR numbers are much higher than the admissions targets for the same time period.

Across the reporting period, SAHs (either SAHs or their Constituent Groups) sponsored the greatest number of PSRs, followed by G5s (66% and 31% respectively).

| 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | Total | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | # | % | |

| Community Sponsors | 192 | 4% | 220 | 4% | 96 | 2% | 124 | 2% | 173 | 4% | 805 | 3% |

| Group of Five | 2,006 | 42% | 2,070 | 37% | 1,226 | 29% | 1,752 | 28% | 763 | 17% | 7,817 | 31% |

| SAH | 2,624 | 54% | 3,284 | 59% | 2,898 | 69% | 4,390 | 70% | 3,620 | 79% | 16,816 | 66% |

| Other | 11 | <1% | 10 | <1% | 5 | <1% | 3 | <1% | 3 | <1% | 32 | <1% |

| Total Sponsored | 4,833 | 100% | 5,584 | 100% | 4,225 | 100% | 6,269 | 100% | 4,559 | 100% | 25,470 | 100% |

Sources: GCMS and FOSS.

When asked about their usage of the BVOR program, SAHs noted that the current high demand for the PSR program, as well as a lack of clarity regarding the BVOR program, prevented them from promoting or utilizing the BVOR program to its full extent.

5.4.2 Family Reunification

Finding #13: Resettlement programs are contributing to refugee family reunification, particularly through the PSR program.

As outlined in IRPA, family reunification is a key objective of Canada’s resettlement efforts, which is met, in part, through the PSR and GAR programs. Private sponsor groups commonly include a member of the refugee’s family in Canada, either as a member of the sponsor group or as a volunteer. In fact, 62% of PSRs surveyed were sponsored by a member of their family.

Similarly, UNHCR takes into consideration the location of family members in Canada in its decision to refer refugees to Canada’s GAR program. When a GAR’s application is sent for destining, the Matching Centre applies ‘family ties’ as the primary criteria for destining GARs. Among the GARs surveyed, 35% had family members living in Canada prior to their arrival; and, of those who had family members living in Canada, 80% were placed in a city or town close to that family member.

5.5 Processing Effectiveness and Efficiency

5.5.1 Processing Effectiveness

Finding #14: There were specific challenges associated with the processing of different refugee groups.

The evaluation found that refugee application processing was affected by a number of key issues that impacted the three programs. While these issues are not solely refugee-specific, they included:

- Slowness of GCMS in CVOA

- IRCC’s late announcement of GAR, PSR, and BVOR annual refugee targets to the CVOA and their key stakeholders (i.e., UNHCR, IOM and SPOs)

- Unclear guidance regarding the 5% cap on high medical needs refugees

- Need to travel to conduct interviews with refugees in many CVOA

There were also specific challenges associated with processing different refugee categories which impacted processing.

In terms of challenges identified with processing PSRs, it was noted that the PSR application process was perceived to be overly complex for the sponsors, and application forms changed often with no grace period offered, and could not be completed online. CVOA staff suggested that the lack of a detailed refugee story sectionFootnote 46 in the PSR application (as compared to GARs) compounded the process of verifying the individual’s identity and assessing eligibility. The majority of key informant interviewees, who could comment, noted that G5 applications continued to have errors, requiring a lot of back and forth between G5s and CPO-W. In addition, PSR application process was particularly impacted by difficulties accessing some refugees for an interview in some countries (in which case the files are dormant until IRCC can conduct interviews), and difficulties in obtaining exit permits (such as in Thailand and Turkey).

CVOA staff noted that a significant amount of work was associated with processing BVOR refugee applications overseas compared to the processing of GAR applications. While the Matching Centre coordinates the online process of connecting a BVOR refugee with a sponsor, CVOA staff are required to validate the identification of the candidates, to develop a case profile to be presented on a website for potential sponsors, and to provide responses to information requests that came from the Matching Centre on behalf of potential sponsors. These steps led to a reduced efficiency for the processing of BVOR refugees.

5.5.2 Approval Rates, Processing Times and Year-End Inventories

Finding #15: Between 2010 and 2014, PSRs had lower approval rates and longer processing time compared to GARs. However, during the same time period, IRCC has been successful in reducing the PSR inventory by 13%, while the GAR inventory increased by 35%.

It is important to note that GAR and PSR processing is affected by admission levels (described in section 4.2.1) which are set annually by Cabinet. If the number of applications received in one year is greater than the level set, the additional applications may be placed at the end of the queue in the inventory. In the case of GARs, UNHCR and other referral agencies are provided with a set number of referrals per year and if the number of GARs admitted is approaching the yearly target for a specific CVOA, IRCC may notify them to slow or halt referrals. For PSRs, until 2012, there were no capsFootnote 47 on applications that could be submitted by sponsors and as a result, the number of applications submitted greatly exceeded the amount that could be processed. This created a large inventory and has lengthened processing times. Therefore, the following statistics have to be considered within this context.

Operationally, processing for GAR is streamlined in comparison to PSR. Referrals from the UNHCR contain verified refugee stories, which CVOA officers then use to interview the applicant. Conversely, the PSR process is more complex and requires additional steps, such as the assessment of sponsors and verification of refugees’ identities and stories.Footnote 48 Reflecting the complexity of the PSR application process, between 2010 and 2014, the overall approval rate for PSRs was lower than GARs at 69%, as compared to 78%.

In terms of processing times, GARs are processed more quickly than PSRs. Between 2010 and 2015, the processing time for 80% of GAR cases ranged from a minimum of 14 months to a maximum of 24 months, while for PSR cases it ranged from 36 to 54 months.Footnote 49 The processing times for 80% of PSR cases increased by 50% from 36 months in 2010 to 54 months in 2015 whereas for GARs, the processing time decreased by 13% from 16 months in 2010 to 14 months in 2015.

PSR processing times were perceived as very long by the sponsor community and refugees. In addition, the sponsor community stressed that long processing times made it difficult for them to keep the sponsorship group, and the larger supporting community, engaged in the process. Some of these difficulties included the upfront work to build interest in sponsoring a refugee, and the level of effort needed to complete an application. On top of these difficulties, since applications took years to process, changing refugee family compositions would alter the resettlement needs of a particular case. In some cases, this may result in one-year window sponsorshipFootnote 50 issues in Canada if refugees do not alert the department of these family composition changes before they depart. Moreover, members of a sponsor group often needed to be replaced and resources needed to be sought elsewhere as the length of processing time increases. PSR also noted that in addition to the stress associated with the lengthy processing times, there was the lack of available updates on the application. Some key informants, SAH representatives, and sponsor focus group participants, therefore, cited the need for a better online method for them to monitor PSR application status.Footnote 51