AB Liznick survived Athabaskan sinking and solitary confinement at POW camp

Harry Liznick on sentry duty in Halifax in 1942.

A massive explosion ripped through His Majesty’s Canadian Ship (HMCS) Athabaskan.

Able Seaman Harry Liznick was forced to leap into the cold waters of the English Channel from his position on the starboard forward anti-aircraft gun.

It was April 29, 1944 and Athabaskan has just been hit by a torpedo from German torpedo boat T-27 as the Battle of the Atlantic raged.

“I could see fire for what seemed 100 feet above me. I lay there looking up and saw pipes, irons, huge chunks of steel, away up in the air. I thought to myself that all this steel would kill me when it came down,” Liznick remembered.

His face burned, and fearing for his life, Liznick jumped over the side.

Athabaskan was listing to port. Swimming as fast as he could, Liznick looked back after 200 feet and “watched as the stern went under and the bow came up and the good old Athabaskan slid under and sank.”

Those trapped below deck went down with the ship.

After chasing T-27 onto the rocks and setting it ablaze with gunfire, sister ship HMCS Haida returned to recover Athabaskan survivors. Launching its boats, floats and scramble nets, Haida’s crew managed to save dozens of dazed and exhausted oil-soaked men.

Too far away to reach safety, Liznick joined the chorus of men in the water hollering for help.

It was to no avail and after lying stopped for 18 minutes, Haida had to abandon the rescue. Dawn was approaching and Haida, close to the enemy coast, was in great peril from aerial attack and from nearby shore batteries.

Of the entire crew, Athabaskan’s captain John Stubbs and 128 men were lost, 42 were rescued by Haida, six managed to reach England in a small craft, and 85 were taken prisoner.

Covered in thick black bunker oil, the survivors fumbled in the water trying to attach themselves to anything that floated.

“The oil seemed at least two inches thick. It covered everything and we had a hard time to hang on to anything. We swallowed a lot of water along with bunker oil and our mouths were thick with grease,” Liznick recalled.

“For those of us that were left behind our ordeal was just beginning...”

At dawn, German ships and several minesweepers set out to rescue survivors. Liznick recalled being well-treated by the German sailors. While still at sea, the survivors were given a shower and “slightly warm gruel” to eat. “It was tasteless and looked like the paste we used in primer school.”

Stripped of their oily clothing, the Athabaskans were issued French navy uniforms that had been confiscated when the Germans took France in 1939. The prisoners were herded below decks and confined in the hold.

Landing in Brest, France, to a crowd of locals and German officials, the Athabaskans were taken to a makeshift hospital that had once been a convent. Within days the survivors were crammed onto trains for the four-day journey to Marlag und Milag Nord, a prisoner of war (POW) camp for naval and merchant seamen outside of Bremen, Germany.

The first six weeks were spent in solitary confinement. Food was sparse and consisted of two slices of black bread, a pat of margarine and a cup of ersatz tea. Later the bread was scaled back to one slice per day, with the prisoners expected to save half the slice for supper.

Liznick was especially challenged by the new ration and said, “What a laugh it is today. How could a starving man keep anything that was edible for any length of time?”

Once a month the sailors got a dehydrated block of sauerkraut about 2.5 inches square. Liznick described it as “hard as a rock! If you put this in a pail of water, it swelled up and we’d have a whole pail of sauerkraut.”

After 11 months of captivity, the mood in the camp changed as radio broadcasts indicated that the Allies were approaching.

On April 25, 1945, the POWs awoke to find the British Second Army had liberated the camp.

The Canadian POWs were flown by Lancaster to Horsham, England, to recuperate and then returned home.

Liznick arrived in Iroquois Falls, Ont., on May 31, 1945, 13 months after being torpedoed and just in time to help his father plant the summer crops.

In 2002, the wreckage of HMCS Athabaskan was located in 90 metres of water near the island of Batz in the English Channel. Many of those who perished are interred at the Plouescat Communal Cemetery southwest of Batz in Brittany, France.

Harry Liznick passed away in 2005.

As the Royal Canadian Navy marks the 75th anniversary of the sinking of HMCS Athabaskan on April 29, 2019, it is wartime seamen like Liznick and his shipmates who personify the courage, determination and fortitude that inspire today’s sailors.

Source

Canadian Naval Review, 2009: A POW’s account of the loss of Athabaskan in 1944, by Pat Jessup.

- Ink drawing of HMCS Haida rescuing Athabaskan survivors, Vice-Admiral Harry DeWolf Room, Bytown Mess, Ottawa.

- Harry Liznick on sentry duty in Halifax in 1942.

- HMCS Athabaskan G07

- Many members of the Royal Canadian Navy have visited the Plouescat Communal Cemetery in France to pay tribute to those sailors from HMCS Athabaskan’s crew buried there.

- Many of those Athabaskans who perished are interred at the Plouescat Communal Cemetery in France.

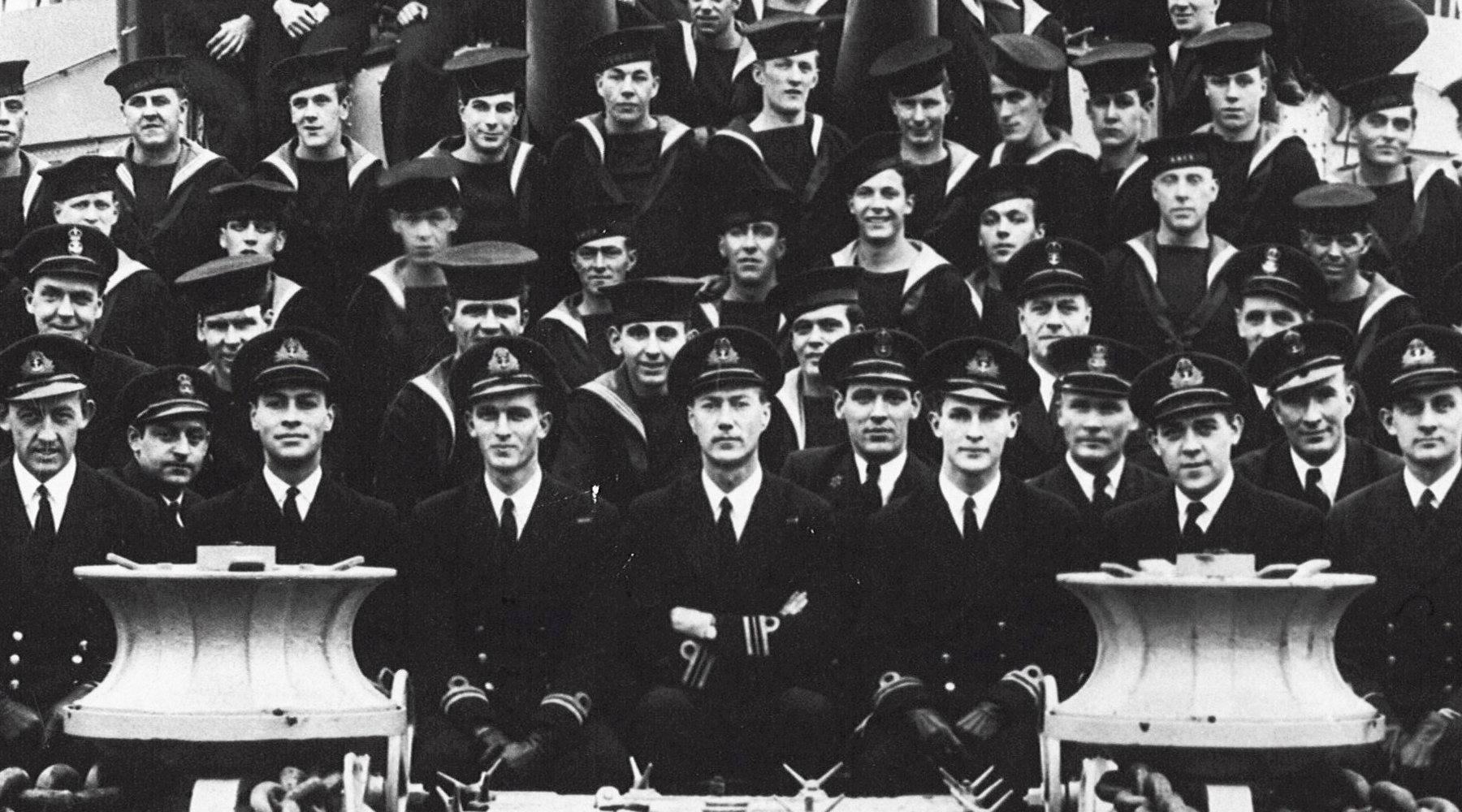

- The Ship's Company of the destroyer HMCS Athabaskan (G07), Plymouth, England, April 1944. LCdr Stubbs is shown in the middle of the first row.

Ink drawing of HMCS Haida rescuing Athabaskan survivors, Vice-Admiral Harry DeWolf Room, Bytown Mess, Ottawa.

Harry Liznick on sentry duty in Halifax in 1942.

HMCS Athabaskan G07

Many members of the Royal Canadian Navy have visited the Plouescat Communal Cemetery in France to pay tribute to those sailors from HMCS Athabaskan’s crew buried there.

Many of those Athabaskans who perished are interred at the Plouescat Communal Cemetery in France.

The Ship's Company of the destroyer HMCS Athabaskan (G07), Plymouth, England, April 1944. LCdr Stubbs is shown in the middle of the first row.